Abstract

We analyze the role of newly integrated data from the child support and child welfare systems in seeding a major policy change in Wisconsin. Parents are often ordered to pay child support to offset the costs of their children’s stay in foster care. Policy allows for consideration of the “best interests of the child.” Concerns that charging parents could delay or disrupt reunification motivated our analyses of integrated data to identify the impacts of current policy. We summarize the results of the analyses and then focus on the role of administrative data in supporting policy development. We discuss the potential and limitations of integrated data in supporting cross-system innovation and detail a series of complementary research efforts designed to support implementation.

Keywords: integrated administrative data, administrative data analysis, cost-benefit analysis, cross-program evaluation, innovative policy solutions

Our counties have asked, “Where did this data come from?” And when we say, “It’s Wisconsin data, it’s eWiSACWIS data, it’s like our families’ data,” they’re like, “Oh,” and it suddenly means something. And, when we say we’re going to keep studying it, people are very interested in that. People clearly feel like the research is going to show them something.

Wisconsin Child Support Policy Workgroup Leader

The current demand for data-driven decision making in public programs is widespread. For example, the Commission on Evidence-Based Policymaking, which was established by the bipartisan Evidence-Based Policymaking Commission Act of 2016, issued its recommendations in September 2017 calling for the use of rigorous evidence created as part of routine government operations in constructing public policy (CEP 2017). The commission’s call was quickly followed by the introduction of the related Foundations for Evidence-Based Policymaking Act of 2017, introduced by Democratic Senator Patty Murray (S. 2046) and Republican Speaker of the House Paul Ryan (H.R. 4174). In addition, academic conferences on the use of “big data” and related analytic techniques are proliferating, and universities and foundations are making major investments in related programs. Despite the enthusiasm reflected in these initiatives, a number of technical, institutional, and cultural challenges are inherent in using administrative data for social policy development that must be addressed. In this article, we analyze the role of integrated data from the child support and child welfare systems in seeding a major policy proposal in Wisconsin, briefly reviewing the empirical research supported by the data and how it motivated the initial consideration of a policy change, before focusing on implementation challenges and how integrated administrative data, and related qualitative research and analysis, can support cross-system policy innovation.

POLICY ISSUE

Why child support and child welfare programs? These programs were selected because studies of related administrative data reveal that, for low-income, single-parent families, child support is often a crucial source of economic support and stability, and in many cases a significant share of income (Office of Child Support Enforcement 2011). Given that numerous studies have shown that children from low-income families are more likely than their affluent peers to experience child abuse or neglect, we expect that child support can serve as a critical tool for preventing child maltreatment by bringing financial resources into the households of struggling families (Berger 2004; Drake and Pandey 1996; Pelton 1994; Sedlak et al. 2010). Evidence suggests that even modest increases in family income can reduce maltreatment risk (Cancian, Yang, and Slack 2013; Pelton 1994).

However, whereas child support has the potential to serve as a key resource for single-parent households living in poverty, it is possible that the child support system also has the potential to harm rather than help children in these families. In particular, when children are removed from the custodial parent’s home and placed in out-of-home care, federal policies allow child support agencies to divert resources from the home to recover a portion of the costs associated with out-of-home care (Chellew, Noyes, and Selekman 2012; Children’s Bureau 2012). In Wisconsin, the focus of our analysis, counties operationalize this directive using one of three mechanisms. First, existing orders of support from a noncustodial parent (the parent who lived apart from the child) to the parent with whom the child lived prior to removal can be redirected from the noncustodial parent to the county. Second, the child support system can initiate a new order for support from the custodial parent to the county. Third, an existing order to the custodial parent from the noncustodial parent can be redirected to the county and a new order can be established for the custodial parent. In other words, for example, if a child living with her mother, and receiving child support from her father, is placed in foster care, the father’s child support may be redirected, and a new child support order could be put in place for the mother, so that both parents make payments to the county to offset the costs of foster care.

Given that we know that poverty often contributes to foster care placements, the loss of income due to changes to existing child support orders and the creation of new orders to offset foster care costs may be a cause for concern (Office of Child Support Enforcement 2017; Wulczyn, Hislop, and Harden 2002). However, the effects of this practice are apparent only when data and outcomes are examined across rather than within systems. This article highlights the findings of analyses of longitudinal, integrated data from both the child welfare and child support systems that in tandem identified the implications of child support referrals for child welfare outcomes. Our analysis informed the development of policy solutions to preclude the charging of families for foster care costs, which our analysis revealed was counterproductive for both families and the state. But, as we discuss, this was only an initial step in the policy change process and just one context in which integrated data can support innovation.

THE ROLE OF ADMINISTRATIVE DATA MANAGEMENT AND ANALYSIS IN SUPPORTING A RESEARCHER-PRACTITIONER PARTNERSHIP

Researchers at the Institute for Research on Poverty (IRP) have a long-standing relationship with State of Wisconsin agencies to support policy-related research. Of particular interest to this article is the close collaboration between IRP researchers and the Wisconsin Department of Children and Families (DCF).1 As part of the long-standing Child Support Research Agreement, researchers at IRP and practitioners and policymakers in the DCF Bureau of Child Support work together to identify a set of research projects aimed at improving policy and practice as they relate to the child support system, the families the system serves, and the agencies and programs with which the system interacts. These projects include research reviews, applied research to address specific policy and practice concerns, exploratory research to fuel innovations within the system, and program evaluation. A key advantage of this collaboration is the ability of researchers and practitioners to work together to share questions and ideas for answering them, and to develop and evaluate potential policy and practice innovations.

Research conducted under the Child Support Research Agreement is facilitated by the integrated data system maintained at IRP known as the Wisconsin Data Core. The Wisconsin Data Core was initially created through a joint effort between IRP and DCF that has now expanded to include other state agencies. The Wisconsin Data Core, generated annually by IRP analysts, draws data from the state’s public assistance, child welfare (eWiSACWIS), child support, unemployment insurance, and incarceration (Wisconsin Department of Corrections and Milwaukee County Jail) administrative data systems. At the heart of the Wisconsin Data Core is the Multi-Sample Person File (MSPF), which identifies each individual that appears in the administrative data and then matches those individuals across all of the program data systems in order to create a unique record for each individual. The MSPF also includes demographic information and county-level location information on each individual. The MSPF can be linked to program case and participation files, resulting in the creation of analysis files that include administrative data from multiple sources and across time. Separate files indicate family relationships (mothers and fathers) for those individuals for whom these relationships can be determined from the available data.

By linking individual-level administrative data from multiple human service agencies, across time, the Wisconsin Data Core provides researchers with the opportunity to create a more complete picture of service needs and outcomes, identify clients who are served by multiple systems, examine participation trends over time, and support cross-program evaluation and analysis. Additionally, by leveraging records from multiple systems that serve parents and children (such as Medicaid birth records and paternity establishment from the child support system) and using this information to link parents to their children, it is possible to construct longitudinal household and family participation records. This is a particularly important advantage because many families are served by multiple systems; however, administrative records from many systems have historically not been shared or linked, thereby severely limiting examination of cross-system effects.

The availability of data through the Wisconsin Data Core has played a crucial role in facilitating the researcher-practitioner partnership between IRP and DCF. The data were, and continue to be, an essential component of the researcher-practitioner collaboration in Wisconsin. The availability of the data was critical to the collaborative effort discussed in this article.

USE OF INTEGRATED ADMINISTRATIVE DATA TO ASSESS POLICY ISSUES

The collaboration reflected here was born out of concern about the potential effects of a current U.S. federal law that requires states to take steps to secure child support from biological parents who have a child in foster care. Although federal policy allows for consideration of the best interests of the child when determining whether to pursue child support to offset the costs of foster care, decisions about child support often focus on the responsibility of both parents to provide financial support and on the ostensible cost savings of charging parents for their children’s care (Chellew, Noyes, and Selekman 2012). Given that poverty often contributes to foster care placements (Office of Child Support Enforcement 2017; Wulczyn, Hislop, and Harden 2002), and consistent with experimental evidence suggesting that child support payments to custodial parents reduces child welfare involvement (Cancian, Yang, and Slack 2013), DCF staff raised concerns that diverting child support or requiring formerly resident parents to pay child support could delay or disrupt reunification efforts (that is, children’s return to their parents). The most salient policy question is whether it is cost effective to order resident parents (typically mothers) to pay child support, and to divert child support payments from noncustodial parents (typically fathers), when children are placed in foster care. In particular, are the foster care costs that are thereby “recovered” by the child support system on behalf of the county greater than the related administrative and program costs? Of particular concern, given that poverty is a significant factor in many child welfare cases, was whether the obligation to pay child support would create a financial barrier to children returning to their parents. Given the high costs of providing foster care, if child support obligations delayed reunification, the net impact was expected to be an increase in public costs.

Using statewide, longitudinal, integrated data from both the child welfare and the child support systems available through the Wisconsin Data Core, we were able to analyze the interactions between the child support and child welfare systems to address these questions.2 Three types of analyses were completed: descriptive, causal, and cost-benefit.

Initial descriptive analysis demonstrated that children in foster care whose mothers were required to pay child support had, on average, longer spells out of home (Cancian and Seki 2010). However, identifying whether child support orders have a causal effect on the length of time children spend in foster care is challenging because the positive relationship between child support orders and the length of out-of-home placements could potentially stem from a number of factors. Based on conversations with state and local child welfare agency staff, we expected that the relationship could simply reflect an appropriate assessment of the likely length of an out-of-home placement. For example, if a child welfare worker knows that a child is likely to be in an out-of-home placement for a significant period, the welfare worker may be more likely to pursue an order for the preplacement resident parent (the parent with whom the child lived before being placed in foster care), or to redirect an established child support order from the preplacement resident parent to the child welfare system. In that case, the positive relationship between child support orders and length of placement could simply reflect the higher rate of referrals to child support for families with children expected to be out of home for a longer period. On the other hand, for disadvantaged families who are required to address an income-related deficiency as part of the requirements to be reunified with their child, such as finding adequate housing, charging the preplacement resident parent child support may create barriers to meeting the permanency plan requirements, which can impede reunification. The implications for policy depend on identifying the causal relationship.

Using the statewide longitudinal data available in the Wisconsin Data Core, we were able to identify and exploit the natural variation in county child support referral practices to estimate the causal effect of referring parents to child support on the duration of out-of-home placements. Although Wisconsin operates a state-supervised child welfare system, child welfare agencies are county run, and variation in policy interpretation and implementation across counties is substantial. Analysis of administrative records allowed us to identify significant differences in the proportion of mothers referred to child support throughout the state, some counties referring virtually all foster care cases to child support, and other counties rarely, if ever, making a referral. Using variation in referral rates as an instrument, we estimated the effect of child support orders on foster care spells—essentially comparing differences in time to reunification for children of mothers who live in low-probability counties, where they are less likely to be referred to child support, versus those in high-probability counties, where they are more likely to be referred to child support (Cancian et al. 2017). We found that charging preplacement custodial mothers (the parent the child lived with before being placed in foster care) or redirecting the child support income the preplacement custodial mothers receive to the county results in a substantial loss in resources for families. Further, our estimates suggested that a $100 child support order to offset foster care costs is associated with a 6.6-month delay in reunification or other permanency options. This finding is important, not only because the extra time in care is financially costly for counties operating child welfare systems, but also because it delays reunification for the families, which is a priority for the child welfare system (Child Welfare Information Gateway 2012).

For these findings to better inform policy, it was important to estimate the extent to which the additional financial costs associated with a delay in reunification would be offset by the child support collections made to the county following an out-of-home placement. Again, integrated administrative data available through the IRP Data Core were important, and were used for a cost-benefit analysis (Chellew, Noyes, and Selekman 2012). The cost-benefit analysis found that 55 percent of children in the child welfare system were associated with a child support order. These orders totaled $11.8 million, which, if fully collected, would have recovered 8 percent of child welfare expenditures in 2011. However, of all of the out-of-home placements made in 2011, only 18.2 percent of cases were associated with at least one child support payment, totaling $3.0 million. Additionally, $1.1 million was collected in arrears. Therefore, on average, counties recovered less than 3 percent of child welfare expenditures in 2011.3 Given the small percentage of child welfare expenditures recovered by associated child support payments and the estimated delay in reunification associated with child support orders, we concluded that ordering parents whose children have been removed from their custody to pay child support was not cost effective.

In this example, administrative data, integrated across programs and data systems, were essential in identifying the consequences of the interaction between two relatively siloed programs. These data also allowed researchers to observe systematic differences in practice across counties, and to leverage those differences to estimate the impact of alternative approaches. The results of that analysis, with the related cost-benefit analysis, provided a basis for leadership in the Wisconsin Department of Children and Families to consider a new approach to serving families dually engaged in the child welfare and child support systems.

UNDERSTANDING THE PROCESSES REVEALED BY THE ANALYSIS OF ADMINISTRATIVE DATA

In Wisconsin, discretion in the referral of child welfare–involved families to child support enforcement rests entirely with the child welfare agency. Child welfare staff are expected to have the information needed to support an assessment of the steps most consistent with the best interests of the child. Once they make their assessment, the child support referral is automatically generated. Although the analysis of administrative data highlighted key differences in outcomes of the referral process—some agencies referring almost all cases, and others rarely referring any—it provided far less insight into the differences in policy and practice that accounted for the variation across counties. We turned to a qualitative study of agency practice to better understand county processes for referring cases to child support following an out-of-home placement. We wanted to understand workers’ perspectives regarding the relevant policies and also to determine whether agency practice is influenced by the information technology. This understanding was essential to the development of potential policy modifications regarding the referral process.

State Policy

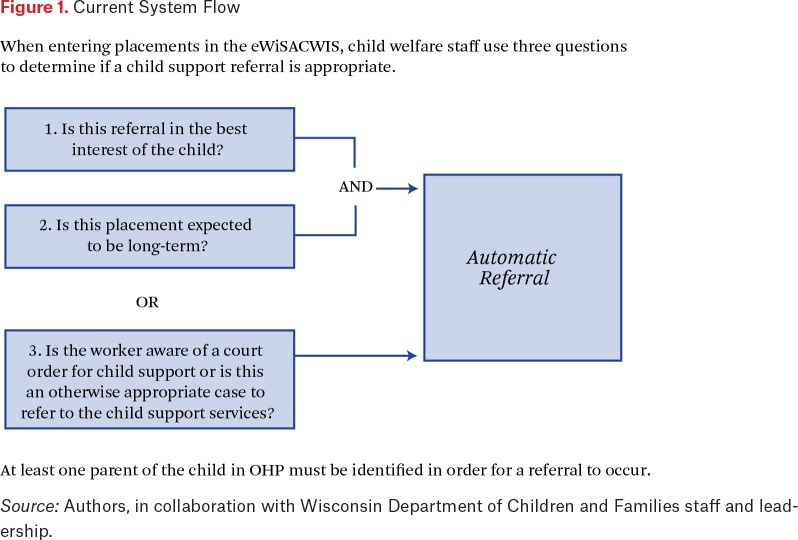

In Wisconsin, at the time of removal, and before a foster home can be determined, county child welfare workers respond to three questions in the Wisconsin Statewide Automated Child Welfare Information System, which then automatically determines whether a referral to child support will be made. The questions are as follows:

Is this referral in the best interests of the child?

Is the placement expected to be long term?

Is the worker aware of a court order for child support or is this otherwise an appropriate case to refer for child support services?

As noted in figure 1, a positive response to questions 1 and 2 in combination will result in a referral to child support. Alternatively, a positive response to question 3 will also initiate a referral to child support regardless of how the other questions were answered. If question 1 or question 3 is marked yes, then the referral applies to field is displayed and becomes required. Child protective service workers can then choose among three choices. The choices are both parents, father only, and mother only. Once a referral is made to child support, the child support agency must take the requisite action and work the case.

Figure 1.

Current System Flow

Source: Authors, in collaboration with Wisconsin Department of Children and Families staff and leadership.

In most cases, the mother is the preplacement resident parent and the father is the noncustodial parent (the parent who lived apart from the child). Therefore, when a child welfare worker selects mother only, it typically means they are referring the preplacement resident parent to child support. Referring the preplacement resident parent to child support generates a new child support order that requires the preplacement resident parent to pay a monthly fee to the county to offset the costs of care for their child. On the other hand, when a child welfare worker selects father only, it usually refers to the noncustodial parent and the system prompts the child support worker who receives the case to determine if there is already a child support order in place.4 If the custodial parent already has a child support order established, the child support worker will redirect the order from the custodial parent to the county. If an order is not in place, the child support worker will attempt to locate the noncustodial parent and establish an order. Finally, if the child welfare worker indicates that both parents should be referred to child support, the child support worker will open cases for both parents, or open a case for the preplacement resident parent and redirect the preplacement resident parent’s child support payments to the county, if an order is already in place for the noncustodial parent.

County Practices

Even though Wisconsin has a policy regarding the referral of out-of-home placement cases to child support that emphasizes the best interests of the child and the expected duration of the placement, most child welfare workers reported, through in-depth, semi-structured interviews, that they refer all cases to child support and do not exercise their discretion when making the decision (Chellew, Noyes, and Selekman 2012). This practice is based on the belief that child support payments are an important source of revenue for the county and that referrals to child support help hold parents responsible for their children while their children are in foster care. Among those workers who reported exercising some discretion, variation in practice was substantial. For example, some county workers did not refer cases that they thought would last for less than six months; others, who reported having good working relationships with their child support agency, worked with child support workers to determine the appropriateness of a referral based on factors related to both the child welfare and child support records (Howard, Noyes, and Cancian 2013). Staff noted that their county referral practices reflected a compromise between doing what is in the best interests of the child and the county’s need to recover costs.

IDENTIFYING PRACTICE OPTIONS

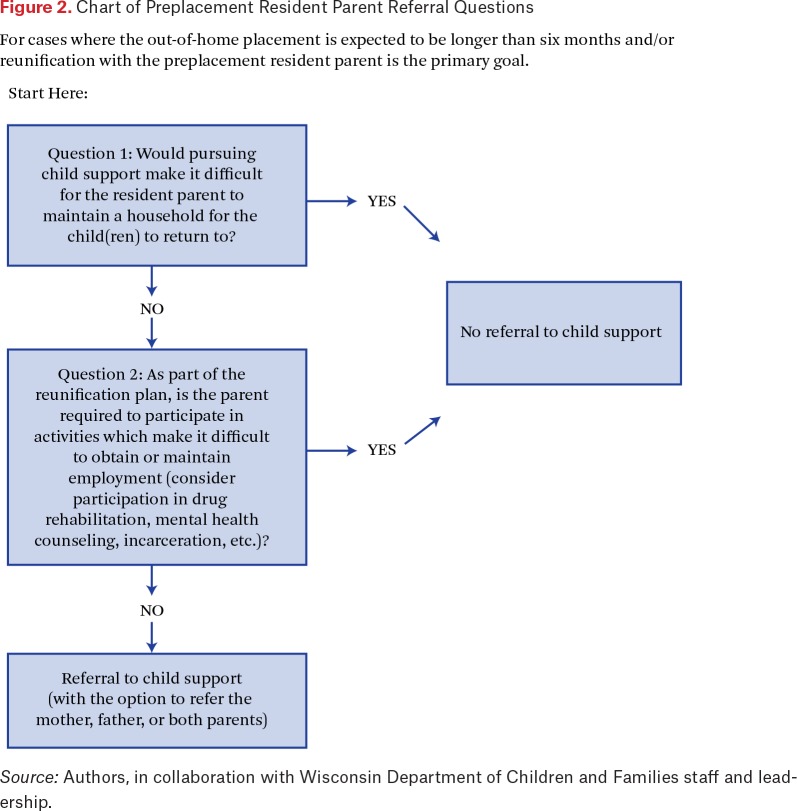

The quantitative analysis of integrated administrative data confirmed concerns about redirecting child support payments from noncustodial parents to the county, or requiring custodial parents to pay child support to the county, when a child is placed in foster care. The initial qualitative interviews helped explain county variation in the application of the policy. Although these analyses supported identification of the policy problem, developing an appropriate solution and an implementation strategy again required information well beyond that available from administrative data analysis. To support that effort, sixty child welfare staff from eleven counties were interviewed. Counties were invited to participate based on their geographical location, population size, poverty levels, relationship with child support staff, and—here, leveraging the analysis of administrative data—the frequency of out-of-home placement cases referred to child support. A flowchart developed by IRP researchers in consultation with DCF staff was used as a tool to assist county staff in thinking about what the best interests of the child may mean as well as the potential timing of a referral.

The flowchart, reflected in figure 2, asked child welfare workers to think about two questions as they worked through a figurative case in which the out-of-home placement is expected to be longer than six months or reunification with the preplacement resident parent is the primary goal:

Figure 2.

Chart of Preplacement Resident Parent Referral Questions

Source: Authors, in collaboration with Wisconsin Department of Children and Families staff and leadership.

Would pursuing child support make it difficult for the resident parent to maintain a household for the child(ren) to return to?

As part of the reunification plan, is the parent required to participate in activities that make it difficult to obtain or maintain employment (consider participation in drug rehabilitation, mental health counseling, incarceration)?

In many instances, child welfare workers were able to identify cases for which such a decision-making structure would have been useful, given that paying child support did severely affect the families and may have interfered with reunification. In considering the first question, for example, child welfare workers noted that charging parents child support after their child is removed from their home only adds to the distress of the family, because doing so decreases the resources available to being able to maintain housing and access services necessary prior to allowing the child to return to the home. Further, charging child support may undermine the ability for a parent to continue a relationship with a child who is placed out of home. One worker noted, for instance, that although the agency encourages parents to visit their children and still purchase items for them, such as their winter coat or favorite food, it becomes increasingly difficult for parents to continue to do so if they are paying child support. Another worker noted a particular case in which, after receiving a child support order, a mother stopped visiting her child, who was placed in a residential treatment facility far from her home, because she could not afford the costs of such visits while also paying child support.

However, despite recognizing the challenges that charging child support may create for families, many workers expressed concern about being able to distinguish between parents who have a hard time paying child support because of poor money management, or some other personal action, versus those parents who truly cannot afford child support, despite their best efforts. Underlying these concerns was the issue of the timing of the referral to child support, given the need to determine the best interests of the child. Over the course of the interviews, child welfare workers identified three key sets of concerns.

Developing adequate information. In counties where intake is separated from ongoing case management within child welfare, intake workers were uncomfortable with thinking about what might be in the best interests of the child in determining whether parents should be referred to child support based on their ability to pay.5 These workers felt that they did not know the families well enough and did not want to get into questions related to income at the time of removal. Ongoing child welfare workers seemed much more willing to think about the best interests question because they felt better able to assess the financial situation of the family. They felt that after working with the family for a time, they would know whether a family could afford to pay child support.

Assessing potential length of removal. Most workers did not feel able to determine the length of a placement during the initial removal of a child. Workers reported not knowing whether a case was going to last more than six months when a child was initially removed. Others remarked that they felt answering yes went against their programmatic goal to reunify children as quickly as possible.

Establishing reunification activities. Some workers stated that they try to think about the parent’s ability to maintain employment when assigning reunification activities. Those who said that they did not consider reunification requirements when making referrals were still able to give examples of cases where it was impossible for parents to maintain employment and follow the permanency plan activities. Many child welfare workers ultimately agreed that it is important to know what the reunification activities will require before referring parents to child support.

The interviews highlighted the importance of the timing of referrals for determining what is in the best interests of the child. The process of discussing the flowchart in figure 2 yielded important information to be considered in potentially modifying state policy and providing guidance regarding its implementation to county child welfare workers. However, although workers indicated that delaying referrals has a number of potential advantages, many child welfare workers contested changes in the timing of referrals due to concerns related to cost recovery and parental responsibility.

INFORMING POLICY DEVELOPMENT AND IMPLEMENTATION

Proponents of the researcher-practitioner model argue that research-practice partnerships facilitate greater use of research in agency decision making (Tseng 2012). Developing research with implications for policy and program improvement is a central goal of the IRP-DCF collaboration. In many cases, the Wisconsin Data Core and access to its integrated administrative data make it possible for the partnership to thrive and be successful. This is the case for the policy problem discussed here. Without the integrated administrative data, we would not have been able to identify and examine patterns of cross-system program participation. Even though DCF staff noted an area of concern, without statewide data for a large sample, our ability to find a potential instrument and identify the causal relationship between child support orders and time in care would have been quite limited. In the absence of the analysis of state administrative data and county fiscal data, the child support recovered from parents was easily quantified, but the delay in reunification, and associated costs, were invisible. The administrative data analysis provided DCF with an opportunity to better understand their child support referral policy and its implications. Moreover, these findings, in combination with the qualitative studies of county child support referral practices, allowed researchers at IRP to not only analyze current practice, but also help inform the discussion of options for change.

Seeding Collaboration

IRP researchers discussed the findings with DCF officials in a variety of settings. After consideration, the DCF Division of Economic Security, which has responsibility for the child support enforcement system, and the DCF Division of Safety and Permanence, which has responsibility for the child welfare system, made the joint decision to work with IRP researchers to begin to develop alternatives to current policy and practice. This collaboration not only represents a promising and novel approach to addressing an unintended policy consequence, but also constitutes a major milestone in efforts for the two systems to work jointly to coordinate policy and practice.

This collaborative endeavor was made possible by a number of factors (Howard 2018). The following are the four most prominent:

A new administrative structure established in 2008 brought the administrations of child welfare and child support, along with other human service programs, into a single department, the Wisconsin Department of Children and Families. In theory, having the two systems under the same administrative structure increased opportunities for coordination.

Guidance at the federal level encouraged collaboration between child welfare and child support systems. For instance, even though federal policy states it is the state child welfare agency’s responsibility to determine which cases to refer based on a determination of the best interests of the child, the federal government issued guidance in 2012 encouraging child welfare and child support agencies “to work together to develop criteria for appropriate referrals in the best interests of the child involved” (Office of Child Support Enforcement 2012).

The cross-program analysis conducted by IRP, through its partnership with DCF, showed how policies and practices in the child welfare system affect clients served by the child support system and vice versa.

Strong leadership, with endorsement of the value of research to inform policy and practice by DCF’s leadership, specifically the department’s secretary, greatly facilitated the collaborative project.

Developing Policy Alternatives

Building on the administrative data analysis, cost-benefit analysis, and qualitative studies, the two DCF divisions and IRP staff developed a framework for modifying the Wisconsin child support policy and delaying referrals to child support from the initial foster care placement to six months after the initial placement. This time frame was selected because, at the six-month mark, child welfare workers are required to establish a permanency plan for children in out-of-home care. The plan outlines the activities parents are required to complete to be reunified with their children. During interviews conducted as part of the qualitative research components, child welfare workers noted that at this point they have a better sense of the family’s lifestyle, their likely cooperation with the permanency plan and reunification activities, and their connection with their children. That allows them to assess whether a family is moving toward reunification, what the parents’ priorities are, and whether charging child support would be in the best interests of the child. This understanding of child welfare practice was central to the development of the policy recommendations. Other factors in support of the delay emerged more clearly from the analysis of caseload dynamics. In particular, many entries into foster care are short term; cases that remain open at six months are less likely to close in the time it will take to establish an order. By contrast, if cases are immediately referred to child support, the order may go into effect after a child and the parents already reunited. Once a child support order is initiated, it can be costly and time consuming to stop the order, and if the order remains in place after reunification, it may increase the risk of the child reentering the child welfare system.

The plan received immediate support from DCF’s senior leadership. The modified policy framework was approved, and DCF assembled a workgroup to flesh out the details of the policy modifications and determine how best to implement it. The workgroup, which comprised county and state child welfare and child support representatives, drew on research from IRP and on additional agency analysis of administrative data. The final recommendations from the workgroup, which are currently under review, call for referrals to child support to be delayed for at least six months, and indefinitely if the parents are actively working toward reunification.

Importance of Research

During the summer and fall of 2017, we conducted semi-structured interviews with members of the policy implementation workgroup. The interview sample included all twenty-eight workgroup members. Four members of the workgroup had left their position either before the start of the research study or during the data collection phase. Eighty-five percent of the potential sample of all workgroup members participated in an interview. One of the primary themes explored during the interviews was the role of research during the policy development, modification, and implementation phases. The workgroup facilitators underscored the significance of the research for both identifying possible innovations and engaging workgroup members. One staff member explained that it is “rare [for DCF] to look at the data before jump[ing] in and work[ing] on [a] policy change.” Instead, the department usually makes policy decisions based on practice experience. However, the staff member noted that having Wisconsin-based research that shows that pursuing child support delays reunification efforts allowed the agency to use “actual research as the basis for making a policy decision.” Moreover, when describing how they used the research to obtain buy-in and motivate workgroup members, one of the facilitators noted, “I always start the conversation with the research. Every conversation I have had about this policy, I [have] start[ed] with the research.” For this facilitator, the research represented an objective middle ground. Understanding the strong convictions some child welfare workers and counties have about the role of child support in both holding parents responsible for their children and offsetting the costs of out-of-home placements, the facilitator used the research to focus policy discussions on the empirical evidence of the impact of current practice. Further, another workgroup leader explained that DCF used the research as a tool to facilitate engagement with stakeholders and obtain buy-in from child welfare and child support staff. She explained, “Our counties have asked, ‘Where did this data come from?’ And when we say, ‘It’s Wisconsin data, it’s eWiSACWIS data, it’s like our families’ data,’ they’re like, ‘Oh,’ and it suddenly means something. And, when we say we’re going to keep studying it, people are very interested in that. People clearly feel like the research is going to show them something.” The responses from the workgroup leaders suggest that having research on the very population served by practitioners helped to establish credibility among caseworker staff and other stakeholders.

In addition to workgroup leaders, workgroup members have indicated that grounding the policy change in research has been helpful for building momentum around the new policy. For instance, one explained, “I think it’s a really smart policy and then if you can get buy-in from different stakeholders by showing them the research and appealing to people’s sense of not wanting kids to stay in out-of-home care longer than they need to, then you can build consensus and build good will about the policy. And, then you can move forward. Any time we have an opportunity to create policy that’s grounded in research, we should because it’s smart. It’s a really, really smart thing to do.” Further, despite the range of beliefs around the use and need for child support orders, another workgroup member noted, “I think that everyone who was in the workgroup was genuinely interested in hearing the research and working together to create a policy that would work and to share the expertise that they had.” The research therefore provided leaders with a vehicle not only for launching discussions on the research findings, but also for engaging practitioners in a dialogue about the implications of implementing a policy based on their experiences working with clients.

Preparing for Implementation

Regardless of the evidence base for a policy change, understanding stakeholders’ perspectives is critical to assessing potential barriers and facilitators to implementation. In the case of the modified child support referral policy, county child welfare agencies will be responsible for implementing the policy redesign. Therefore, their view of the policy is important because their buy-in is likely to shape how well, and to what extent, they implement the modified policy (Bartlett and Vavrus 2017; Lipsky 1980; Zacka 2017). Moreover, our early interviews suggested that some child welfare workers strongly believe that they need to refer parents to child support in order to recover costs associated with out-of-home care (Howard, Noyes, and Cancian 2013). This tension may lead some counties to find a work-around, which would interfere with the fidelity of policy implementation and be expected to compromise effectiveness (Durlak and DuPre 2008).

To assess stakeholders’ perceptions of the appropriateness and usefulness of the modified policy, and their beliefs on the causes of poverty and child maltreatment, we administered a survey to child welfare workers statewide.6 The survey was sent to all child welfare intake and ongoing staff, as well as to supervisors, throughout Wisconsin. Individuals in these roles were selected as the sample population because they are usually responsible for determining if a child should be removed from their home, if a child support order should be made, and reunification goals. Ultimately 1,159 individuals participated in the survey, for a response rate of 58 percent. Most of the questions in the survey were based on the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research, and were devoted to either understanding the respondents’ perceptions on the validity of the evidence for the policy redesign or their perceptions on the appropriateness and usefulness of the modified policy (Damschroder et al. 2009).7

Only one in four survey respondents (24.7 percent) indicated that they were aware of the child support policy redesign prior to taking part in the survey. Of those who were aware, 36.4 percent specified that they understood the purpose of the redesign somewhat well, and about 20.0 percent indicated that they understood very or extremely well.

Perceptions on the Evidence That Led to the Redesign

Relatively few of all survey respondents (15.3 percent) indicated that they were aware of the research from IRP on the relationship between child support referrals and the amount of time children spend in foster care prior to taking the survey.8 The respondents who were aware of the research conducted by IRP were asked how well they remember the research; if they were surprised by the research findings, based on their previous experiences making child support referrals for families involved in the child welfare system; and the extent to which the research findings changed their perspective. As shown in table 1, about one in four (27.1 percent) of these respondents indicated that they remembered the research somewhat well and about 10 percent noted that they remembered it very or extremely well. Additionally, 11 percent of respondents reported that they were either very or extremely surprised by the research findings. Many respondents (38.4 percent) were at least somewhat surprised by the research results, and about half (47.2 percent) reported that their perspective was at least somewhat changed by the research.

Table 1.

Staff Perceptions of Child Welfare Practice, Economic Resources, and Child Outcomes

| Relationship Between Child Support Referrals and the Length of Time in Foster Carea | |||||

| Question | Response Categories and Responses | ||||

| How well do you remember the research shared by the Institute for Research on Poverty or DCF about the relationship between child support referrals and the amount of time children spend in foster care? (N = 177) | Not at all well | A little bit well | Somewhat well | Very well | Extremely well |

| 16.9% | 45.8% | 27.1% | 9.6% | ||

| Based on your previous experience, how surprised were you by the research findings? (N = 171) | Not at all surprised | A little bit surprised | Somewhat surprised | Very surprised | Extremely surprised |

| 30.4% | 30.9% | 27.4% | 7.0% | 4.0% | |

| To what extent did the research findings change your perspective? (N = 169) | None | A little | Somewhat | Quite a bit | A very great deal |

| 28.9% | 23.6% | 29.5% | 17.7% | 0% | |

| Relationship Between Economic Resources and Child Maltreatmentb | |||||

| Question | Response Categories and Responses | ||||

| How much does a family’s income and other economic resources affect a child’s risk for maltreatment? (N = 995) | None | A little | Somewhat | Quite a bit | A very great deal |

| 1.6% | 9.5% | 29.3% | 42.1% | 17.3% | |

| How much does a family’s income and other economic resources affect a family’s involvement in the child welfare system? (N = 994) | None | A little | Somewhat | Quite a bit | A very great deal |

| 3.1% | 8.7% | 27.8% | 44.8% | 15.3% | |

Source: Authors’ calculations.

All survey respondents were asked if they were aware of any research shared by the Institute for Research on Poverty or DCF about the relationship between child support referrals and the amount of time children spend in foster care. Survey respondents who selected “yes” (n = 177) were then asked questions about the relationship between child support referrals and the length of time in foster care.

All respondents, regardless of if they were aware of the policy redesign or the research from IRP, were asked these questions.

All respondents, regardless of their familiarity with the IRP research, were asked two general questions about the role of economic resources on the risk of child maltreatment. As shown in table 1, more than 85 percent of respondents believe that economic resources affect a child’s risk of maltreatment at least somewhat, and more than half indicate that economic resources affect it quite a bit or a very great deal. The same percentage believe economic resources affect a family’s involvement in the child welfare system.

In sum, relatively few respondents were aware of the original research that contributed to the policy redesign, and six months prior to the proposed implementation only about one in four were aware of the modified policy. Yet, more than 85 percent believe that economic resources affect a child’s risk of maltreatment and a family’s involvement in the child welfare system at least somewhat, and more than half believe that economic resources affect both situations quite a bit or a very great deal. These results indicate that the majority of child welfare workers agree that there is a connection between economic resources and child maltreatment and child welfare involvement, even though relatively few were aware of the child support policy redesign, its purpose, and the evidence base.

CONCLUSION

High-quality data are in great demand as policymakers seek to make decisions about programs and funding using evidence-based strategies. As a result, universities and other research organizations have invested substantial effort, time, and financial resources in creating systems and analyzing data in such a way that meets these needs. In Wisconsin, comprehensive administrative data is the cornerstone of the researcher-practitioner model. IRP and Wisconsin state agencies, particularly DCF, have supported this model through investment in and sustained maintenance of the Wisconsin Data Core in the context of a long-standing collaborative partnership.

The child support referral policy analysis described in this article illustrates the advantages of a joint effort that brings together linked administrative data and related qualitative research to support the efforts of those establishing as well as implementing the policy. An important lesson to be drawn is that, although the Wisconsin Data Core played a crucial role in facilitating policy-relevant research, its creation was just a first step toward evidence-based policymaking. Using the research to inform policy and practice changes required an additional investment in understanding the policy context—an effort that required a substantial investment in qualitative research drawing on field work. Efforts to assist with policy development also involved assessing and taking into account the perspectives of local agency staff who are most directly responsible for implementing policy revisions. These types of investments may be essential to the success of initiatives designed to promote data-driven decision making.

Footnotes

The Wisconsin Department of Children and Families is responsible for providing (and overseeing county provision of) services to assist children and families, including child abuse and neglect investigations, adoption and foster care services, the Wisconsin Works program, the childcare subsidy program, and child support enforcement and paternity establishment, among other programs and services.

Although not all of the researchers who contributed to this and other analyses summarized are listed as authors, the article uses we throughout to refer to the body of work generated during the IRP-DCF partnership.

Because child welfare agencies provide a multitude of services that are interrelated, it is challenging to disaggregate case management and program services into discrete activities. This, along with the fact that child welfare services are financed through various funding mechanisms, led us to use a very conservative estimate of out-of-home costs. We did not account for administrative or facility costs or the long-term societal costs of having children in the child welfare system for an extended period. Instead, we calculated only the costs of payments to care providers using state administrative data and county fiscal data. In addition to these estimates, we calculated the amount of child support collected for all foster care cases during 2011, including arrears, using administrative data from the child support enforcement system.

In some cases, though less prevalent, the father is the resident parent and the mother is the noncustodial parent.

In some counties, child welfare services are provided by two different staff members: intake and ongoing child welfare workers. In these cases, intake staff assess allegations of child abuse and neglect and determine whether the allegations are substantiated. An intake worker who determines that maltreatment has occurred is responsible for removing the child from the home and locating an out-of-home placement. Once this occurs, the case is transferred to an ongoing child welfare worker who has oversight of out-of-home placement cases. The ongoing worker is responsible for conducting a family assessment, creating a permanency plan, assisting with reunification efforts, and evaluating the parent’s progress toward the goals outlined in the permanency plan.

This survey, known as the Wisconsin Child Support Policy Redesign Implementation Survey was a web based, Qualtrics survey, administered by the University of Wisconsin Survey Center during the summer of 2017 approximately six months before the scheduled statewide implementation of the modified child support policy. The instrument underwent two rounds of pilot testing to ensure face-validity and ease of use before it entered the field. The survey was in the field for four weeks.

The Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR) provides a framework of constructs that are associated with effective implementation. Each of the child support policy redesign-specific questions were mapped to a CFIR construct.

The respondents who were aware of the redesign were more likely to be aware of the research from IRP.

REFERENCES

- Bartlett Lesley, and Vavrus Frances. 2017. Rethinking Case Study Research: A Comparative Approach. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Berger Lawrence M. 2004. “Income, Family Structure, and Child Maltreatment Risk.” Children and Youth Services Review 26(8): 725–48. [Google Scholar]

- Cancian Maria, and Seki Mai. 2010. “Child Support and the Risk of Child Welfare Involvement: An Initial Assessment of Relationships.” Report submitted to the Wisconsin Department of Children and Families. Madison: Institute for Research on Poverty, University of Wisconsin–Madison. [Google Scholar]

- Cancian Maria, Yang Mi-Youn, and Slack Kristen Shook. 2013. “The Effect of Additional Child Support Income on the Risk of Child Maltreatment.” Social Service Review 87(3): 417–37. [Google Scholar]

- Cancian Maria, Cook Steven T., Seki Mai, and Wimer Lynn. 2017. “Making Parents Pay: The Unintended Consequences of Charging Parents for Foster Care.” Children and Youth Services Review 72:100–10. [Google Scholar]

- Chellew Carol, Noyes Jennifer L., and Selekman Rebekah. 2012. “Child Support Referrals for Out-of-Home Placements: A Review of Policy and Practice.” Report to the Wisconsin Department of Children and Families. Madison: Institute for Research on Poverty, University of Wisconsin–Madison. [Google Scholar]

- Children’s Bureau . 2012. Child Welfare Policy Manual. Washington: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Administration for Children and Families. Accessed November 1, 2018. https://www.acf.hhs.gov/cwpm/public_html/programs/cb/laws_policies/laws/cwpm/policy.jsp. [Google Scholar]

- Child Welfare Information Gateway . 2012. “Reunifying Families.” Accessed November 1, 2018. https://www.childwelfare.gov/topics/permanency/reunification.

- Commission on Evidence-Based Policymaking (CEP) . 2017. The Promise of Evidence-Based Policymaking: Report of the Commission on Evidence-Based Policymaking. Washington, D.C.: CEP. Accessed November 1, 2018. https://www.cep.gov/content/dam/cep/report/cep-final-report.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Damschroder Laura J., Aron David C., Keith Rosalind E., Kirsh Susan R., Alexander Jeffery A., and Lowery Julie C.. 2009. “Fostering Implementation of Health Services Research Findings into Practice: A Consolidated Framework for Advancing Implementation Science.” Implementation Science 4:50. DOI: 10.1186/1748-5908-4-50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drake Brett, and Pandey Shanta. 1996. “Understanding the Relationship Between Neighborhood Poverty and Specific Types of Child Maltreatment.” Child Abuse & Neglect 20(11): 1003–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durlak Joseph A., and DuPre Emily P.. 2008 “Implementation Matters: A Review of Research on the Influence of Implementation on Program Outcomes and the Factors Affecting Implementation.” American Journal of Community Psychology 41(3–4): 327–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howard Lanikque. 2018. “Righting Our Wrongs: A Mixed Methods Case Study of a Collaboration Between Human Service Agencies to Address an Unintended Policy Consequence and Increase the Well-Being of Children.” Ph.D. diss., University of Wisconsin–Madison. [Google Scholar]

- Howard Lanikque, Noyes Jennifer L., and Cancian Maria. 2013. “The Child Support Referral Process for Out-of-Home Placements: Potential Modifications to Current Policy.” Report submitted to the Wisconsin Department of Children and Families. Madison: University of Wisconsin–Madison, Institute for Research on Poverty. [Google Scholar]

- Lipsky Michael. 1980. Street-Level Bureaucracy: Dilemmas of the Individual in Public Services. New York: Russell Sage Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- Office of Child Support Enforcement . 2011. “Custodial Parents and Child Support Receipt: Story Behind the Numbers.” Fact Sheet No. 2. Washington: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Administration for Children and Families. [Google Scholar]

- Office of Child Support Enforcement . 2012. “Requests for Locate Services, Referrals, and Electronic Interface.” Informational Memorandum IM-12–2. Washington: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Administration for Children and Families. Accessed November 1, 2018. https://www.acf.hhs.gov/css/resource/requests-for-locate-services-referrals-and-electronic-interface. [Google Scholar]

- Office of Child Support Enforcement . 2017. FY 2015 Annual Report to Congress: Office of Child Support Enforcement. Washington: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Administration for Children and Families. Accessed November 1, 2018. https://www.acf.hhs.gov/css/resource/fy-2015-annual-report-to-congress. [Google Scholar]

- Pelton Leroy H. 1994. “The Role of Material Factors in Child Abuse and Neglect.” In Protecting Children from Abuse and Neglect: Foundations for a New National Strategy, edited by Melton Gary B. and Barry Frank D.. New York: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sedlak Andrea J., Mettenburg Jane, Basena Monica, Petta Ian, McPherson Karla, Greene Angela, and Li Spencer. 2010. Fourth National Incidence Study of Child Abuse and Neglect (NIS–4): Report to Congress. Washington: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Administration for Children and Families. [Google Scholar]

- Tseng Vivian. 2012. “The Uses of Research in Policy and Practice.” Social Policy Reports 26(2): 3–16. [Google Scholar]

- Wulczyn Fred, Hislop Kristen B., and Harden Brenda J.. 2002. “The Placement of Infants in Foster Care.” Infant Mental Health Journal 23(5): 454–75. [Google Scholar]

- Zacka Bernardo. 2017. When the State Meets the Street: Public Service and Moral Agency. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]