Abstract

This review summarizes paleontological data as well as studies on the morphology, function, and molecular evolution of the cochlea of living mammals (monotremes, marsupials, and placentals). The most parsimonious scenario is an early evolution of the characteristic organ of Corti, with inner and outer hair cells and nascent electromotility. Most remaining unique features, such as loss of the lagenar macula, coiling of the cochlea, and bony laminae supporting the basilar membrane, arose later, after the separation of the monotreme lineage, but before marsupial and placental mammals diverged. The question of when hearing sensitivity first extended into the ultrasonic range (defined here as >20 kHz) remains speculative, not least because of the late appearance of the definitive mammalian middle ear. The last significant change was optimizing the operating voltage range of prestin, and thus the efficiency of the outer hair cells’ amplifying action, in the placental lineage only.

It is well known that the term cochlea derives from the Greek word for snail. However, in the auditory literature, its usage has long ceased to be strictly tied to a coiled shape and is often used to mean any auditory organ of a land vertebrate. As we will discuss, even for mammals, coiling is not a universal feature of their hearing organs, so the term has truly lost its literal meaning and we will also use it here only for convenience and in a loose sense. Perhaps more importantly, coiling is merely one of several unique features that arose at different times during mammalian evolution. The cochlea that we typically have in mind for mammals such as the mouse did not suddenly appear as a complete package. This is of more than simply historical interest. Even within extant (currently living) mammal species, the structure of their cochleae can only be understood when the history of their lineages is taken into account. Historical contingency has had an enormous influence on these sensory systems (Manley et al. 2018), but much less of an impact on their function. This review aims to integrate what is known about the evolutionary history of the mammalian cochlea and what this may imply about its function (i.e., we seek to understand the selective pressures that shaped the mammalian cochlea into what we observe today). As we will see below, the basic arrangement of the cellular structures, including that of the organ of Corti, are shared traits that likely arose in the reptilian ancestors of mammals and are thus homologous across all living mammals. Others, such as the form of the bony enclosure and its intricate details (e.g., ganglionic canal, cribriform plate for the passage of the branches of the auditory nerve) or the optimal voltage range of electromotility were established many millions of years later and are not shared by all living mammals. Finally, convergent evolution characterizes the history of the middle ear (i.e., it arose several times independently, presumably in response to similar selective pressures [Manley 2010]).

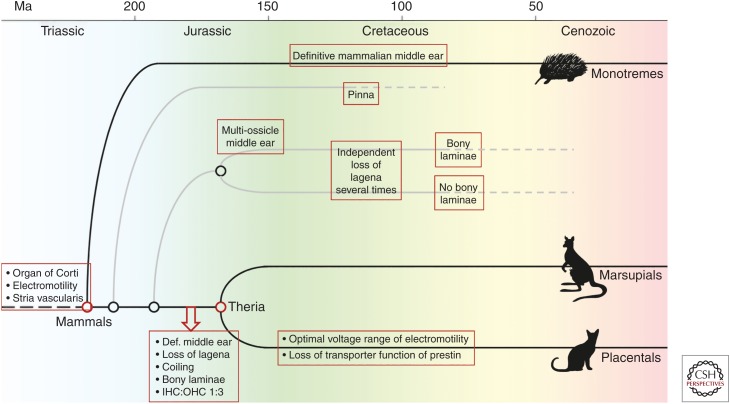

Most mammalian lineages became extinct, but the substantial variation seen in fossils of their auditory structures—middle and inner ear—is still instructive and we will discuss it where appropriate. A detailed familiarity with mammalian phylogeny is not required for this and we refer the interested reader to recent paleontological reviews (Ekdale 2016; Luo et al. 2016). Figure 1 shows a simplified phylogenetic tree highlighting the evolutionary developments discussed in this review. Two branching points on the mammalian family tree are of specific significance to our discussion of cochlear evolution and are marked as red nodes in Figure 1:

The very early separation, about 220 million years (Ma) ago, of the lineage leading to monotreme mammals. There are only four surviving species of that line, the duck-billed platypus Ornithorhynchus anatinus and three echidna or spiny anteater species (genera Tachyglossus and Zaglossus), all famously egg-laying.

The later split of the therian mammals, about 170 Ma ago, into the two lineages leading to present-day marsupial (pouched or metatherian) and placental (eutherian) mammals.

Figure 1.

A simplified phylogenetic tree of mammals, highlighting major branch nodes and selected mammalian groups referred to in the text. Time progresses from left to right (present). Extinct lines are shown in gray, lines with surviving modern representatives in black. Boxes highlight major events with respect to cochlear evolution that are discussed in the text. Def., Definitive; IHC, inner hair cell; OHC, outer hair cell.

THE FOSSIL HISTORY OF MIDDLE (AND OUTER) EARS

The middle ear is included in this review to emphasize the fact that middle and inner ear are a functional tandem and cannot be interpreted in isolation. Although it is widely understood that mammals have a three-ossicle middle ear and nonmammals have a single-ossicle middle ear, there is a popular misconception that the latter led to the former. This is not so. The mammalian middle ear arose independently de novo and is not an improved single-ossicle middle ear (e.g., Kitazawa et al. 2015). Indeed, the middle ear of mammals also arose several times independently as the result of similar selection pressures in different mammalian lineages that initially did not involve hearing, but rather eating (reviewed in Manley 2010). This is an in interesting example of convergent evolution (i.e., of independent derivation of functionally similar solutions in response to similar selective pressures) and is briefly summarized in the next section.

Many Ways from Biting to Hearing

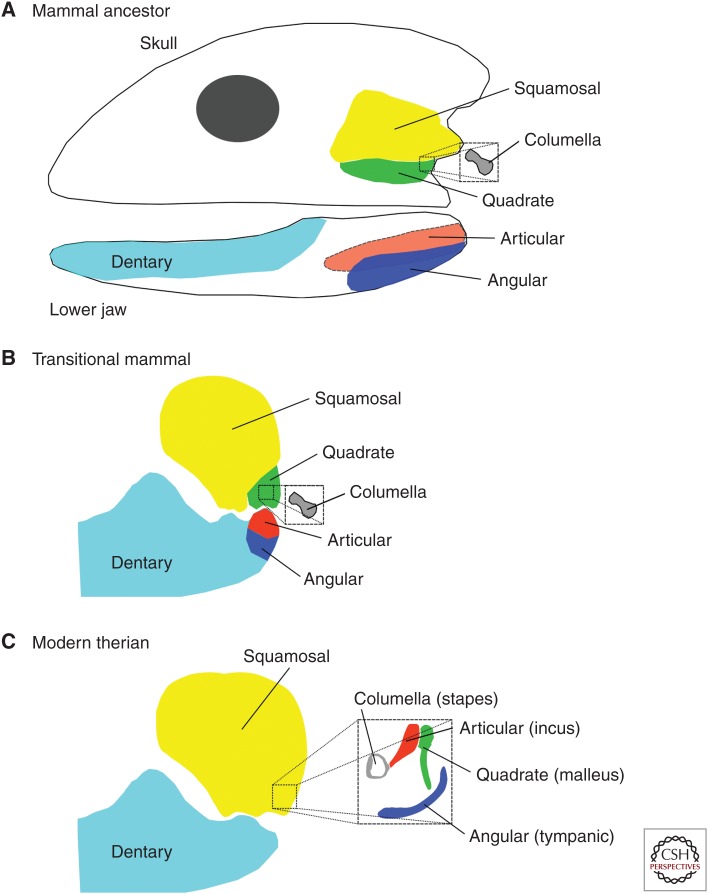

The lower jaws of species that belong to that highly diverse group popularly known as “reptiles,” but in fact consisting of very divergent and not closely related groups (and including the birds), are complex structures. They consist or consisted of a number of bones, usually seven. One of these bones, the articular, articulated with the rest of the skull on a bone known as the quadrate, form the primary jaw joint. This was also the condition in the ancestors of the various lineages of true mammals, which are here defined as those vertebrates that possess a secondary jaw joint. Although it is not understood which selection pressures led to its evolution, the secondary jaw joint resulted from the loss of all but one bone (the dentary) from the lower jaw and the displacement of the main articulation (via an intermediate with a double articulation) to the squamosal bone of the skull. This change no doubt had important effects on the biting force and chewing motions of the jaw (only mammals chew their food), but here we are concerned with the side effects of this transformation. Both bones of the primary jaw joint became redundant but fortuitously lay close to the stapes on the inner side and the skin on the outer side. The change in eating mechanics changed selection pressures on the stapes (previously a strong bone bracing the outer skull against the braincase) and it became much smaller. At its inner end, its inner bracing plate on the bony inner ear became the stapes footplate and its outer end evolved an articulation with the articular bone, henceforth known as the incus. The incus retained its articulation with the quadrate (the malleus). The skin outside of the malleus became supported by additional residual bones (e.g., the tympanic) and, as the eardrum or tympanum, fused to a long extension of the malleus (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Schematic drawings of major evolutionary steps in the origin of the therian middle ear. (A) Important components of the skull and lower jaw of a mammalian ancestor. The lower jaw consisted of seven bones, of which one, the dentary, later formed the entire lower jaw, as shown in B and C (in which the lower jaw is shown truncated at the front). Two other bones are important later in evolution, the articular (which actually lies mainly on the inside of the jaw) and the angular. In the skull, two caudal-lying bones, the squamosal and the quadrate, are highlighted, as is the columella, a support strut that is drawn enlarged but actually would be hidden on the inside of the squamosal/quadrate area (smaller box indicates its approximate position). The quadrate forms the upper part, and the articular the lower part, of the ancestral jaw joint. (B) An intermediate stage in early mammals, such as Diarthrognathus, which possessed a double jaw joint (Allin and Hopson 1992). The primary joint between quadrate and articular, drawn here at the rear of the joint, actually formed the inside section of the joint. The outside section of the joint (here shown as if it formed the front of the joint) was formed by a new connection between the squamosal of the skull and the dentary (the lower jaw). The columella lay hidden behind the quadrate and connected to the inner ear (smaller box indicates its approximate position). (C) Position and size of bones in a therian mammal. The jaw joint is now only formed between the squamosal and the dentary. Articular, quadrate, and angular bones have become very small and now lie inside/behind/above the jaw joint (smaller box indicates their approximate positions) and form the articular = incus (that forms a joint with the columella = stapes), quadrate = malleus that connects to the eardrum, and angular = tympanic that partly supports the eardrum.

The above process is one of the oldest-documented stories of evolutionary transformation (reviewed in Manley 2010) and has been confirmed by every subsequent paleontological and developmental study. More recent fossil findings have highlighted the various stages of this transformation and shown that the process took a very long time indeed (at least 100 Ma, more in some extinct lineages). Although remarkable in itself, even more remarkable is that this evolutionary sequence occurred a number of times independently in different lineages—including separately in monotremes, on the one hand, and therian mammals, on the other (Fig. 1). Recently, a group of gliding fossil mammals has been described in which there was a five-ossicle (!) middle ear (Fig. 1) (Han et al. 2017).

The Crucial Match between Middle- and Inner-Ear Impedances and the Consequences for High-Frequency Hearing

In summary, multi-ossicular middle ears arose at least several times in mammalian lineages. The final results differ, and some middle ears, such as those of monotremes, are stiff and less sensitive than others (Aitkin and Johnstone 1972). There are different types of middle ears, depending, for example, on just how the bones are suspended and arranged in relation to each other (reviewed in Mason 2013). In therians, the final state of the delicate, tympanic middle ear, known as the definitive mammalian middle ear (Luo 2007), arose at about the same time as the coiling process of the cochlea had completed one full circle (Fig. 1) (reviewed in Manley 2013). Therian middle ears consist of hard, tiny bones connected to a thin tympanic membrane. Because its lever system is based on an articulated chain of bony elements, it is, in principle, better suited to transmit high frequencies than the middle ear of nonmammals whose single columella–extracolumellar complex always retains flexible, not fully ossified parts (Manley 1972). However, the middle-ear chain is not the sole determinant of the system’s performance (reviewed in Ruggero and Temchin 2002). Mechanical or electrical systems connected in series influence each other, such that a change in the impedance of the “receiving” system (in this case the inner ear) can influence the response properties of the “delivering” system (here, the middle ear). The form of the transfer functions of therian middle ears suggests that beyond the upper response frequency of the inner ear (i.e., the highest frequency point along the organ of Corti), the impedance of the inner ear rises rapidly. This is reflected in a steep drop in the displacement amplitudes of middle-ear components. In guinea pigs, this occurs near 40 kHz (Manley and Johnstone 1974) and in the bat Eptesicus at around 70 kHz (Manley et al. 1972).

Thus, the popular conclusion that the evolution of a multi-ossicle middle ear in mammals per se increased the upper frequency limit of hearing is a misconception. Without a well-matched impedance of the inner ear, transmission of high frequencies will not happen. The multi-ossicle middle ear did, however, likely increase the potential upper frequency limit (i.e., it paved the way for high-frequency hearing). Because of the interactive nature of middle and inner ears in determining the sensitive hearing range, it remains difficult to infer the hearing ranges of extinct animals from their fossil remains and interpretations differ (e.g., Grothe and Pecka 2014; Manley 2016). Based on further evidence about the organ of Corti discussed below, we believe the most parsimonious assumption is that a significant extension of sensitivity into the ultrasonic range occurred fairly late and only in the therian lineage.

Bullae and Pinnae

In both nonmammals and mammals, the eardrum of a tympanic middle ear can only function well if the air pressure on both its outside and its inside are the same. This necessity is enabled by connecting the space behind the eardrum (the middle ear space in mammals) with the buccal—or mouth—cavity, or at least making this connection possible. The connecting spaces are known as Eustachian tubes and, as with their middle ears, evolved independently in mammals and nonmammals (Takechi and Kuratani 2010); this is another example of convergent evolution in response to similar selective pressures. The middle-ear spaces themselves, having relatively hard walls, were also independently expanded in many therian groups and at different times as evidenced by, for example, in the different tissues surrounding, and the bones bounding, the expanded spaces. These expanded middle-ear cavities are known as bullae and are highly variable among different mammalian groups (Novacek 1977). The increased middle-ear volume increases the compliance of the tympanum in certain frequency ranges and therefore permits the eardrum to respond with greater sensitivity at those frequencies. Thus, even some quite small mammals, such as many rodent groups, have substantially increased their sensitivity to low frequencies (Heffner et al. 2001), in response to selective pressures where better low-frequency sensitivity meant a higher reproductive success (fitness increase) in the animals’ habitats.

Pinnae act as sound collectors and, depending on their size and shape, improve not only sensitivity but also interaural level cues for sound localization. Furthermore, pinnae provide novel monaural cues for localizing sounds in elevation (reviewed in Brown and May 2005) at sound wavelengths that are roughly equivalent to or shorter than their physical dimensions. Their presence thus implies relatively high-frequency sensitivity, at least in small animals. It is widely assumed that pinnae only evolved in therian mammals, because monotremes lack a pinna. The fossil record cannot provide any real clues here as skin imprints fossilize only under very rare circumstances. The recent identification of pinnae on a fossil in which skin imprints were preserved is therefore all the more intriguing (Martin et al. 2015). The animal was a member of the eutriconodonts, an extinct, early branch off the therian line (Fig. 1, earliest branch shown in gray). It was the size of a small rat, with pinnae of 5–10 mm outside dimensions, which—if those pinnae served the same functions as in modern mammals—would function best above 20 kHz. Unfortunately, no details are known of the inner ears of eutriconodonts, but a parsimonious assumption is that the cochlea was short and uncoiled (Ekdale 2016). The middle ear still retained connections to the jaw (“partial mammalian middle ear” [Luo et al. 2016]) and is thus unlike any adult modern form. It is, however, very speculative to place that finding in a functional context and only adds to the current uncertainty about when hearing sensitivity extended into the ultrasonic range.

UNIQUE FEATURES OF MAMMALIAN COCHLEAE: WHEN DID EACH ARISE AND WHY?

Coiling and the Advantages of Longer Cochleae

A coiled cochlea is today observed in all therian mammals (marsupials and placentals), always turns in the same direction (on a given side of the head), and, by definition, comprises more than one full turn (Vater and Kössl 2011). In contrast, all pretherian mammals displayed short and only mildly curved bony cochlear canals (Luo et al. 2016). Interestingly, the direction of cochlear curvature, if present, is typically mammalian even in the earliest forms, “with the apex bending away from the midline of the skull” (Schultz et al. 2017). This is different to that of curved nonmammalian cochleae (e.g., those of birds) whose curvature follows the braincase ventrally, with the apex pointing toward the midline of the skull. In monotremes, the membranous cochlear duct curves more than the bone surrounding it, but still does not reach a full 360° turn (Schultz et al. 2017). As in nonmammals, the cochlear canal of the earliest mammals and living monotremes includes a lagenar macula at its apex. Whether its loss was in any way linked and thus directly accelerated full coiling or was merely coincidental, remains an open question (see also below).

Coiling is most likely a space-saving feature (Manley 2017b; Pietsch et al. 2017), so the salient evolutionary novelty that coiling reflects is a significant elongation of the cochlea. What was the selective pressure that favored elongation? Manley (2017a) has argued that the impetus was the final stages of the evolution of efficient tympanic middle ears, paving the way for a coevolution of middle and inner ear toward extended high-frequency sensitivity.

In early therians, the length at the transition from pretherians (2–5 mm) was rapidly exceeded in the various lineages of mammals that radiated following the demise of the dominant dinosaurs about 65 Ma ago. A change in cochlear length can bring either of two advantages, or both. First, because frequency responses in the cochlea are arranged in a tonotopic way (each octave occupies roughly the same space), space becomes the currency of potential frequency range. In other words, the auditory range can be extended at either the low- or high-frequency end to fill the newly evolved space while maintaining the same relationship between a frequency octave and the space it occupies (the space constant). Alternatively, the additional space can be used to change the space constant to greater values, which would mean more hair cells per octave and thus more auditory-nerve fibers that, together, provide more information to the brain. This may or may not also result in an improved frequency selectivity (Vater and Kössl 2011). It should be noted that extensions of the frequency range to lower frequencies are less likely than the extension to higher frequencies, for three principle reasons: (1) the ancestral cochlea already was a low-frequency receptive organ (Manley 2017a); (2) as each octave occupies roughly the same space, moving from a low-frequency limit of 20 Hz to 10 Hz would occupy the same space as adding from 10 kHz up to 20 kHz—low-frequency octaves are expensive on space; and (3) really low-frequency hearing is only efficient in rather large animals, as the sizes of suitable receptive surfaces such as the external ear, eardrum, etc., need to be large to “capture” long-wave-length sound signals. Nonetheless, although in most mammalian groups evolution during and after the Cretaceous greatly improved high-frequency hearing, many groups of large mammals such as elephants, with an upper limit lower than that of humans (Heffner and Heffner 1982), a number of rodents (Heffner et al. 2001), and subterranean-living small mammals, such as golden moles (Narins and Willi 2012), evolved an emphasis on lower frequencies.

Invasion of Bone/Formation of Spiral Laminae

Another unique feature of mammalian cochleae is the invasion of bone into the soft tissues (Manley 2012). In a typical modern therian cochlea, these bony components are known as Rosenthal’s canal around the cochlear ganglion, the ossified primary lamina surrounding the nerve fibers running to and exiting from the organ of Corti and supporting its inner (modiolar) edge and, if present, the partly ossified secondary spiral lamina supporting its outer edge. Microcomputed tomography (micro-CT) examinations of fossil specimens are now able to visualize such bony details with unprecedented resolution and have revealed primary and/or secondary laminae in some early pretherian and therian mammals with short, uncoiled cochleae (Hoffmann et al. 2014). Although originally described otherwise, living monotremes do not show any of these bony invasions (recent review in Schultz et al. 2017). The likely time of their origin is currently only vaguely known. It may have happened shortly after the separation of the monotreme line, or anytime later, but before the separation of the two therian lineages (Hoffmann et al. 2014). Both therian lineages inherited these bony invasions, which are thus a shared trait of modern marsupial and eutherian cochleae (Vater et al. 2004).

The functional significance of these bony invasions (i.e., the improvement that favored their selection) remains uncertain. This feature, too, has been interpreted as suggesting sensitivity to high frequencies (Luo et al. 2011). In modern therian mammals, the presence of an osseous secondary lamina is indeed consistently associated with sensitivity to frequencies above about 10 kHz. However, the reverse is not true, questioning a causal relationship (Manley 2016). In other words, although a mechanical stiffening effect of such bony supports on the basilar membrane may be assumed and appears beneficial at high frequencies, it is obviously not a necessary prerequisite for high-frequency sensitivity and its initial advantage could have been something else, such as a more efficient impedance match to a stiff middle ear (Manley 2012).

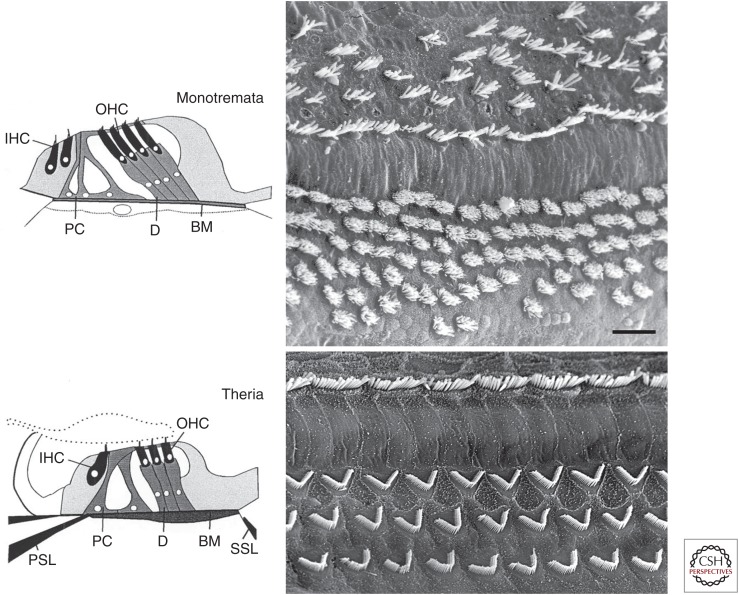

Organ of Corti/Inner and Outer Hair Cells

The organ of Corti was probably the earliest uniquely mammalian feature of the inner ear; it evolved before coiling, before loss of the lagenar macula, and before any invasion of bony supports to the organ (Fig. 1). This conclusion is based on the fact that living monotremes share the characteristic arrangement of inner hair cells (IHCs) and outer hair cells (OHCs), separated by a tunnel of Corti formed by pillar cells (Pritchard 1881; Alexander 1904). However, despite the clear distinction of IHCs and OHCs, respectively, by position and morphology, monotreme inner ears differ in detail (Fig. 3). There are four to five rows of IHCs, three to four pillar cells, and six to seven rows of OHCs across the organ (Ladhams and Pickles 1996). Thus, although the total number of hair cells (7750 in an echidna) may be similar to that of a medium-sized therian cochlea, numbers of IHCs and OHCs do not exist in a strict 1:3 relation, and the rows of hair cells are less orderly arranged. Furthermore, whereas the hair bundles of monotreme IHCs show the characteristic linear arrangement and reduction to two to three rows of stereovilli (Neugebauer and Thurm 1984) (more frequently referred to as stereocilia), those of OHCs do not so clearly display the V- or W-shaped characteristic of therian OHCs, and typically have many rows of stereovilli (Fig. 3) (Ladhams and Pickles 1996). Monotreme OHCs do show the characteristic cylindrical shape and submembrane cisternae (Smith and Takasaka 1971; Ladhams and Pickles 1996). It is also likely that a degree of electromotility is present (see below). However, and importantly, the innervation pattern of monotreme IHCs and OHCs by afferent and efferent terminals is not known. It thus remains open to what extent the full package of associated features that characterize therian IHCs and OHCs is present in monotremes. Of note, this is even unknown for marsupials, as there are also no data on the innervation of their cochlear hair cells (Vater and Kössl 2011). Therefore, we should perhaps be cautious about prematurely assuming full eutherian-type differentiation of IHCs and OHCs, including the nearly complete domination of afferent connections by IHCs and evolution of the uniquely mammalian efferent subpopulations associated with IHCs and OHCs (Köppl 2011).

Figure 3.

Comparison of monotreme (top two panels) and therian (bottom two panels) organ of Corti. In each case, a schematic drawing of a typical cross section is shown on the left and a scanning electron micrograph (SEM) of hair-cell bundles on the right (tectorial membrane removed). (From Vater et al. 2004; adapted, with permission, from Springer Science + Business Media © 2004.) BM, Basilar membrane; D, Deiter’s cells; IHC, inner hair cell; OHC, outer hair cell; PC, pillar cell; PSL, primary osseous spiral lamina; SSL, secondary osseous spiral lamina. (Top right) SEM image of the monotreme organ of Corti shows an example from platypus. (Image kindly supplied by J.O. Pickles, © Graceville Press, Brisbane, Australia.) (Bottom right) SEM image of the therian organ of Corti shows an example from rat. (Image kindly supplied by Marc Lenoir [see Pujol et al. 2016].) Note more rows of both IHCs (toward the top of each image) and OHCs in the platypus, as well as the more disorderly arrangement of the cells and the different morphology of OHC bundles, compared to the rat. Scale bar, 10 µm (applies to both SEM panels).

High Endocochlear Potential and OHC Electromotility

Therian mammals show a uniquely high endocochlear potential (EP) of between +80 and +120 mV (Schmidt and Fernandez 1962; Lukashkina et al. 2017) that is maintained by the stria vascularis (recent review in Wangemann and Marcus 2017). Nonmammals maintain lower EPs in their auditory endolymph (although typically higher than in the vestibular endolymph) and the tissue responsible for its production lacks the multilayered structure and salient cellular specializations of the eutherian stria vascularis (recent review in Wilms et al. 2016). A stria vascularis has been identified at the gross morphological level in both monotremes (Pritchard 1881; Smith and Takasaka 1971) and marsupials (Aitkin et al. 1979), suggesting an early origin in the mammalian line. Marsupials also show the uniquely high EP (Schmidt and Fernandez 1962), so it is safe to assume that they also share the cellular specializations. The EP in monotremes has not been measured, leaving it unknown just how far any strial specializations have evolved in this group.

The ultimate cause (i.e., the selective pressure toward the uniquely high EP in mammals) is again somewhat speculative. Auditory sensitivity is compromised when the EP is experimentally lowered. Therefore, a gain in sensitivity is commonly cited as the reason for a high EP (e.g., Hibino et al. 2010). However, mammals are not more sensitive than modern nonmammals (Wilms et al. 2016; Manley 2017a). Instead, it may be more specifically an improved sensitivity to higher frequencies that drove selection for an increased EP in both mammals and nonmammals (Wilms et al. 2016). In mammals, this may be additionally favored by providing an increased drive to OHC electromotility, their novel amplifying mechanism. So, when did electromotility arise?

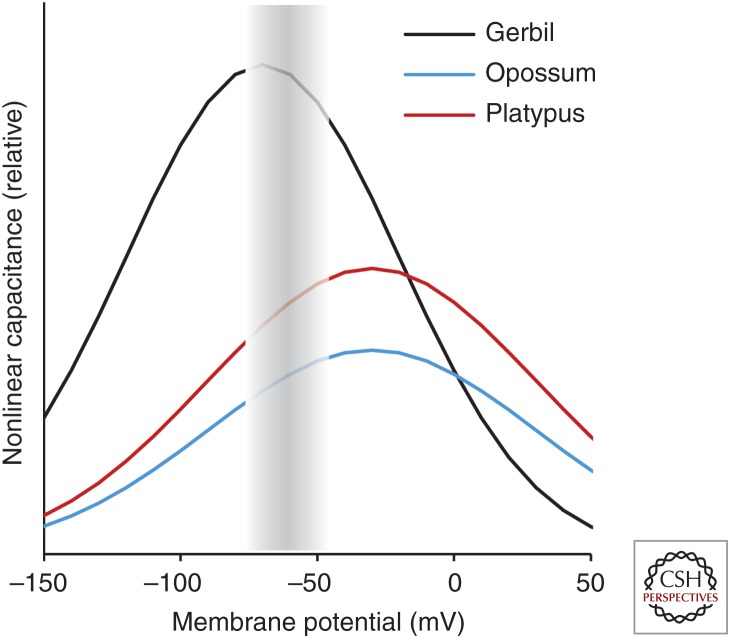

In auditory hair cells, two active, motile systems have been identified that work to overcome viscous damping in the fluid environment of the inner ear: (1) an ancestral mechanism integral to the gating of transduction channels of the hair bundle, and (2) an electromotile response unique to the OHCs of mammals, based on large numbers of the protein prestin in the lateral hair-cell membrane (Hudspeth 2008). The ancestry of the prestin gene has been traced back to an anion transporter, and crucial intermediate steps for acquiring voltage sensitivity and the ability to produce a motile response have been identified (reviews in He et al. 2014; Russell 2014). Importantly, this includes the prestin variant based on genomic sequence data from the platypus and expressed in cultured cells (Tan et al. 2011). It may thus be assumed that monotreme OHCs possess a degree of electromotility, although comparative measurements on the cultured expression system suggested that the motion effected by platypus prestin is only about 60% of that of eutherian prestin under comparable voltage stimulation (Tan et al. 2011). Furthermore, and important for in vivo function, prestins from both platypus and a marsupial (opossum) species show their peak sensitivity at significantly more positive membrane potentials than a typical eutherian prestin from gerbil (Fig. 4) (Tan et al. 2011; Liu et al. 2012). Indeed, only eutherian prestin has undergone a final, crucial modification that shifted its peak sensitivity closer to the natural resting potential of OHC and abolished most of the original anion transporter function (Liu et al. 2012). Taken together, a parsimonious interpretation is that prestin-based electromotility arose early in mammalian evolution, concurrently with the differentiation of IHCs and OHCs. However, its effectiveness would initially have been low and probably still is in modern monotremes and marsupials, because of its nonoptimal voltage activation range and lower motile force. This is also consistent with the low upper frequency limit of monotreme hearing, around 15 kHz (Gates et al. 1974; Mills and Shepherd 2001). We suggest that a gradual shift of importance from the plesiomorphic transduction-channel-based mechanism to the novel electromotility, simultaneous with a gradual expansion of sensitivity to higher frequencies, is most likely.

Figure 4.

Schematic illustration of nonlinear capacitance measured in cultured cells transfected with prestin derived from genomic sequence data of a monotreme (platypus), a marsupial (opossum), and a placental mammal (gerbil); after data shown in Tan et al. (2011) and Liu et al. (2012). Nonlinear capacitance reflects the voltage sensitivity of prestin and, for platypus and gerbil prestin, has been shown to correlate with the extent of the motile response. The shaded region indicates the approximate range of in vivo outer hair cell (OHC) membrane potential fluctuations. Note that both platypus and opossum prestin have the peak of their sensitivity outside this range.

Loss of the Lagenar Macula and Its Consequences for Endolymphatic Calcium

Like nonmammals, monotremes still have the vestibular lagenar macula situated at the apex of their cochlear duct (Pritchard 1881). In therian mammals, the lagena is lost. When exactly this happened during mammalian evolution is currently difficult to pinpoint from fossil evidence (recent review in Schultz et al. 2017) and it may well have happened multiple times in extinct, early branch-offs of the therian line (Fig. 1) (Hoffmann et al. 2014). What favored a loss of the lagena remains equally unclear (Manley 2017b). In the therian lineage, it is likely to have happened around the time of the first full coiling of the therian cochlea (Luo et al. 2011). It has been suggested that the two events may be linked and the lagenar macula was not lost but transformed and formed the low-frequency region at the apex of the organ of Corti (Fritzsch et al. 2013). This scenario seems unlikely, however, as mammalian ancestors with a lagena almost certainly already possessed low-frequency hearing organs. In any case, the disappearance of the vestibular lagenar macula and its associated otolith must have had a profound effect on the calcium metabolism of the auditory organ (Manley 2017b).

An otolithic membrane is typical for vestibular maculae that respond to linear accelerations. The otoliths consist of calcium salts whose surface is in ionic exchange with the surrounding fluid. If the calcium concentration in the surrounding fluids falls too low, the otoliths’ surfaces erode and continue to do so until the crystals have dissolved (Payan et al. 2002). Consistent with this, calcium levels in vestibular endolymph and also in the scalae mediae of nonmammals are at least 100 µm and often higher (Ferrary et al. 1988; Manley et al. 2004; Ghanem et al. 2008), whereas typical values for the scala media of therian mammals are 20–30 µm (i.e., about one order of magnitude lower [Wangemann and Marcus 2017]). Calcium in endolymph influences many aspects of the hearing process, from the integrity of the tectorial membrane (Kronester-Frei 1979) to the mechanoelectrical transduction of the hair cells (Fettiplace and Ricci 2006). The final loss of otoliths bordering on the auditory scala media presumably caused at least a minor crisis in therian cochlear function during the Cretaceous period (Manley 2017b). Such a crisis would have driven changes in the mechanisms of ion homeostasis, modifications to the structure of the tectorial membrane, and alterations to the mechanoelectrical transduction channels. Among the unique features of the eutherian cochlea that may have resulted from that is the collagen matrix of its tectorial membrane (Goodyear and Richardson 2002). Furthermore, in eutherian mammals, calcium is actively pumped into scala media and there is evidence that even partial impairment of this activity leads to a drop in endolymphatic [Ca2+] below a critical threshold, where transduction fails (Wood et al. 2004). Finally, a reduced Ca dependence of the transduction channels on eutherian cochlear hair cells has been proposed (Peng et al. 2013, 2016). None of these features have been characterized for any monotreme or marsupial, so it remains speculative which changes are truly related to the loss of the vestibular otolith and how long these processes may have taken.

Loss of Regenerative Capacity

The loss of regenerative capacity in the mammalian cochlea will be briefly mentioned here, as it is having a major impact on concepts to ameliorate human hearing loss by attempting to regenerate lost hair cells. One unexpected finding of comparative auditory research is the remarkable ability of bird cochleae to regenerate hair cells and restore auditory function after damage by loud sounds or other insults (Cotanche 1999; Smolders 1999; Rubel et al. 2013; Ryals et al. 2013). This is apparently an ongoing process that leads to the maintenance of pristine hearing thresholds into exceptionally old age (up to 13 years in European starlings [Langemann et al. 1999] and up to 23 years in barn owls [Krumm et al. 2017]). The ability to regenerate hair cells, inherited from ancestors and still shown in, for example, mammalian vestibular organs (Walshe et al. 2003; Warchol 2011), has been lost in the mammalian cochlea. This loss appears to be linked to the characteristic structure of the organ of Corti, where also the supporting cells specialize to an extreme degree and are integrated into the transmission of acoustic energy—from active hair cells, for example, into the movements of the organ of Corti. The crucial difference to birds thus lies in the more “primitive” state of avian cochlear support cells that are only one step away from dividing and forming a new hair cell and a supporting cell (Brigande and Heller 2009). In mammals, the much greater specialization of the supporting cells (e.g., pillar cells, Deiters’s cells) probably precludes dedifferentiation and reentry into the cell cycle. It seems that a gradual loss of hair cells and deterioration in auditory health throughout life is a price mammals pay for the evolution of the organ of Corti. Current research is exploring different ways of inducing dedifferentiation or introducing stem cells into the cochlea, with the hope of inserting new hair cells and thus initiating therapies for human hearing loss (Mittal et al. 2017).

HUMAN COCHLEAE

Among mammals, the human cochlea shows an average length of ∼34 mm; the length varies among therian mammals from 7 to 70 mm (Vater et al. 2004). Recently, it has become routine to examine cochlear length before implanting cochlear devices, which has revealed a surprisingly large variation in its dimensions in humans. There are small average differences between the sexes, but maximal reported differences between individuals are up to 18% (Erixon et al. 2008) or even more than one-third (36%) (Würfel et al. 2014). Differences in the numbers of auditory nerve fibers can be even larger (reviewed in Miller 1985). It is not known whether such length variations have an effect on the cochlear map of frequencies (are some frequencies missing in short cochleae or is the space constant smaller?).

Humans are, of course, primates that are closely related to chimpanzees. Information on the form and length of primate cochleae has been reviewed (Coleman and Colbert 2010; Wannaprasert and Jeffery 2015), describing interesting changes observed in human ancestors. In primates, cochlear length correlates negatively with the upper frequency limits (Kirk and Gosselin-Ildari 2009). The earliest primates had shorter cochleae and good high-frequency but probably poor low-frequency hearing. Perhaps because of a general increase in body size in the ancestors of modern monkeys and apes, cochlear size increased, leading to improved low-frequency hearing (Coleman and Boyer 2012). In the lineage leading to humans and chimpanzees, cochlear size again increased significantly, probably enabling even better low-frequency hearing (Braga et al. 2015). It is difficult to know to what extent these changes were simply a result of increasing animal size, and to what extent they may have been driven by selection for cochleae more appropriate for the processing of low-frequency communication signals. Although there is some evidence for improved low-frequency—relative to high-frequency—selectivity in human cochleae (Manley and van Dijk 2016), the basic question of the frequency selectivity of the human cochlea is still a highly controversial issue.

CONCLUDING REMARKS

The mammalian cochlea evolved many of its characteristic features early, and these shared traits were inherited by all living representatives. Later features, such as the spiral shape, loss of the lagena macula, and integration into a bony enclosure evolved only in therians, showed greater specialization toward higher frequencies and the use of prestin as an active hair-cell motor. Over eons of time, these specializations led to the loss of the ability to regenerate hair cells, leading to progressive hearing loss in long-lived species such as humans.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors gratefully acknowledge support by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG) over many years, currently through the Cluster of Excellence “Hearing4All” DFG-EXI 1077; and DFG KO 1143/14-1 and 1143/15-1 to C.K. Further support by the Bundesministerium für Bildung und Forschung (BMBF) “US-German Collaboration in Computational Neuroscience” program, FEPAS 01GQ1505B to C.K.

Footnotes

Editors: Guy P. Richardson and Christine Petit

Additional Perspectives on Function and Dysfunction of the Cochlea available at www.perspectivesinmedicine.org

REFERENCES

- Aitkin L, Johnstone BM. 1972. Middle-ear function in a monotreme: The echidna (Tachyglossus aculeatus). J Exp Zool 180: 245–250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aitkin LM, Gates GR, Kenyon E. 1979. Some peripheral auditory characteristics of the marsupial brush-tailed possum, Trichosurus vulpecula. J Exp Zool A Comp Exp Biol 209: 317–322. [Google Scholar]

- Alexander G. 1904. Entwicklung und Bau des inneren Gehörorgans von Echidna aculeata [Development and morphology of the auditory inner ear of Echidna aculeata]. Denkschr Med-naturwiss Ges Jena 6: 3–118. [Google Scholar]

- Allin EF, Hopson JA. 1992. Evolution of the auditory system in Synapsida (“mammal-like reptiles”) as seen in the fossil record. In The evolutionary biology of hearing (ed. Webster DB, et al. ), pp. 587–614. Springer, New York. [Google Scholar]

- Braga J, Loubess JM, Descouens D, Dumoncel J, Thackeray JH, Kahn JL, de Beer F, Riberon A, Hoffman K, Balaresque P, et al. 2015. Disproportionate cochlear length in genus Homo shows a high phylogenetic signal during apes' hearing evolution. PLoS ONE 10: e0127780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brigande JV, Heller S. 2009. Quo vadis, hair cell regeneration? Nat Neurosci 12: 679–685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown CH, May BJ. 2005. Comparative mammalian sound localization. In Sound source localization (ed. Popper AN, Fay RR), pp. 124–178. Springer, New York. [Google Scholar]

- Coleman MN, Boyer DM. 2012. Inner ear evolution in primates through the Cenozoic: Implications for the evolution of hearing. Anat Rec 295: 615–631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coleman MN, Colbert MW. 2010. Correlations between auditory structures and hearing sensitivity in non-human primates. J Morphol 271: 511–532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cotanche DA. 1999. Structural recovery from sound and aminoglycoside damage in the avian cochlea. Audiol Neurootol 4: 271–285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ekdale EG. 2016. The ear of mammals: From monotremes to humans. In Evolution of the vertebrate ear: Evidence from the fossil record (ed. Clack JA, et al. ), pp. 175–206. Springer, Basel, Switzerland. [Google Scholar]

- Erixon E, Högstorp H, Wadin K, Rask-Andersen H. 2008. Variational anatomy of the human cochlea: Implications for cochlear implantation. Otol Neurotol 30: 14–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrary E, Tran Ba Huy P, Roinel N, Bernard C, Amiel C. 1988. Calcium and the inner ear fluids. Acta Otolaryngol Suppl 460: 13–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fettiplace R, Ricci AJ. 2006. Mechanoelectrical transduction in auditory hair cells. In Vertebrate hair cells (ed. Eatock RA, et al. ), pp. 154–203. Springer, New York. [Google Scholar]

- Fritzsch B, Pan N, Jahan I, Duncan JS, Kopecky BJ, Elliott KL, Kersigo J, Yang T. 2013. Evolution and development of the tetrapod auditory system: An organ of Corti-centric perspective. Evol Dev 15: 63–79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gates GR, Saunders J, Bock GR, Aitkin L, Elliott MA. 1974. Peripheral auditory function in the platypus. Ornithorhynchus anatinus. J Acoust Soc Am 56: 152–156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghanem TA, Breneman KD, Rabbitt RD, Brown M. 2008. Ionic composition of endolymph and perilymph in the inner ear of the oyster toadfish, Opsanus tau. Biol Bull 214: 83–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodyear RJ, Richardson GP. 2002. Extracellular matrices associated with the apical surfaces of sensory epithelia in the inner ear: Molecular and structural diversity. J Neurobiol 53: 212–227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grothe B, Pecka M. 2014. The natural history of sound localization in mammals—A story of neuronal inhibition. Front Neural Circuits 8: 116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han G, Mao F, Bi S, Wang Y, Meng J. 2017. A Jurassic gliding euharamiyidan mammal with an ear of five auditory bones. Nature 551: 451–456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He DZ, Lovas S, Ai Y, Li Y, Beisel KW. 2014. Prestin at year 14: Progress and prospect. Hear Res 311: 25–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heffner RS, Heffner HE. 1982. Hearing in the elephant (Elephas maximus): Absolute sensitivity, frequency discrimination, and sound localization. J Comp Physiol Psychol 96: 926–944. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heffner RS, Koay G, Heffner HE. 2001. Audiograms of five species of rodents: Implications for the evolution of hearing and the perception of pitch. Hearing Res 157: 138–152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hibino H, Nin F, Tsuzuki C, Kurachi Y. 2010. How is the highly positive endocochlear potential formed? The specific architecture of the stria vascularis and the roles of the ion-transport apparatus. Pflugers Arch 459: 521–533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmann S, O'Connor PM, Kirk EC, Wible JR, Krause DW. 2014. Endocranial and inner ear morphology of Vintana sertichi (Mammalia, Gondwanatheria) from the Late Cretaceous of Madagascar. J Vert Paleontol 34: 110–137. [Google Scholar]

- Hudspeth AJ. 2008. Making an effort to listen: Mechanical amplification in the ear. Neuron 59: 530–545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirk EC, Gosselin-Ildari AD. 2009. Cochlear labyrinth volume and hearing abilities in primates. Anat Rec 292: 765–776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitazawa T, Takechi M, Hirasawa T, Adachi N, Narboux-Neme N, Kume H, Maeda K, Hirai T, Miyagawa-Tomita S, Kurihara Y, et al. 2015. Developmental genetic bases behind the independent origin of the tympanic membrane in mammals and diapsids. Nat Commun 6: 6853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Köppl C. 2011. Evolution of the octavolateral efferent system. In Auditory and vestibular efferents (ed. Ryugo D, et al. ), pp. 217–259. Springer, New York. [Google Scholar]

- Kronester-Frei A. 1979. The effect of changes in endolymphatic ion concentrations on the tectorial membrane. Hearing Res 1: 81–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krumm B, Klump G, Köppl C, Langemann U. 2017. Barn owls have ageless ears. Proc Biol Sci 284: 20171584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ladhams A, Pickles JO. 1996. Morphology of the monotreme organ of Corti and macula lagena. J Comp Neurol 366: 335–347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langemann U, Hamann I, Friebe A. 1999. A behavioral test of presbycusis in the bird auditory system. Hearing Res 137: 68–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Z, Li GH, Huang JF, Murphy RW, Shi P. 2012. Hearing aid for vertebrates via multiple episodic adaptive events on prestin genes. Mol Biol Evol 29: 2187–2198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lukashkina VA, Levic S, Lukashkin AN, Strenzke N, Russell IJ. 2017. A connexin30 mutation rescues hearing and reveals roles for gap junctions in cochlear amplification and micromechanics. Nat Commun 8: 14530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo ZX. 2007. Transformation and diversification in early mammal evolution. Nature 450: 1011–1019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo ZX, Ruf I, Schultz JA, Martin TA. 2011. Fossil evidence on evolution of inner ear cochlea in Jurassic mammals. Proc R Soc B 278: 28–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo ZX, Schultz JA, Ekdale EG. 2016. Evolution of the middle and inner ears of mammaliaforms: The approach to mammals. In Evolution of the vertebrate ear: Evidence from the fossil record (ed. Clack JA, et al. ), pp. 139–174. Springer, Basel, Switzerland. [Google Scholar]

- Manley GA. 1972. Frequency response of the middle ear of geckos. J Comp Physiol 81: 251–258. [Google Scholar]

- Manley GA. 2010. An evolutionary perspective on middle ears. Hearing Res 263: 3–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manley GA. 2012. Evolutionary paths to mammalian cochleae. J Assoc Res Otolaryngol 13: 733–743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manley GA. 2013. Mosaic evolution of the mammalian auditory periphery. In Basic aspects of hearing (ed. Moore B, et al. ), pp. 3–9. Springer, New York. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manley GA. 2016. The foundations of high-frequency hearing in early mammals. J Mamm Evol 10.1007/s10914-016-9379-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Manley GA. 2017a. Comparative auditory neuroscience: Understanding the evolution and function of ears. J Assoc Res Otolaryngol 18: 1–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manley GA. 2017b. The mammalian Cretaceous cochlear revolution. Hearing Res 352: 23–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manley GA, Johnstone BM. 1974. Middle-ear function in the guinea pig. J Acoust Soc Am 56: 571–576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manley GA, van Dijk P. 2016. Frequency selectivity of the human cochlea: Suppression tuning of spontaneous otoacoustic emissions. Hear Res 336: 53–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manley GA, Irvine DRF, Johnston BM. 1972. Frequency response of bat tympanic membrane. Nature 237: 112–113. [Google Scholar]

- Manley GA, Sienknecht UJ, Köppl C. 2004. Calcium modulates the frequency and amplitude of spontaneous otoacoustic emissions in the bobtail skink. J Neurophysiol 92: 2685–2693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manley GA, Lukashkin AN, Simoes P, Burwood GWS, Russell IJ. 2018. The mammalian ear: Physics and the principles of evolution. Acoust Today 14: 8–16. [Google Scholar]

- Martin T, Marugán-Lobón J, Vullo R, Martin-Abad H, Luo ZX, Buscalioni AD. 2015. A Cretaceous eutriconodont and integument evolution in early mammals. Nature 526: 380–384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mason MJ. 2013. Of mice, moles and guinea pigs: Functional morphology of the middle ear in living mammals. Hear Res 301: 4–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller MR. 1985. Quantitative studies of auditory hair cells and nerves in lizards. J Comp Neurol 232: 1–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mills DM, Shepherd K. 2001. Distortion product otoacoustic emission and auditory brainstem responses in the echidna (Tachyglossus aculeatus). J Assoc Res Otolaryngol 2: 130–146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mittal R, Nguyen D, Patel AP, Debs LH, Mittal J, Yan D, Eshraghi AA, Van De Water TR, Liu XZ. 2017. Recent advancements in the regeneration of auditory hair cells and hearing restoration. Front Mol Neurosci 10: 236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narins PM, Willi UB. 2012. The golden mole middle ear: A sensor for airborne and substrate-borne vibrations. In Frontiers in sensing (ed. Barth FG, et al. ), pp. 275–286. Springer, Vienna. [Google Scholar]

- Neugebauer DC, Thurm U. 1984. Chemical dissection of stereovilli from fish inner ear reveals differences from intestinal microvilli. J Neurocytol 13: 797–808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novacek MJ. 1977. Aspects of the problem of variation, origin and evolution of the eutherian auditory bulla. Mamm Rev 7: 131–149. [Google Scholar]

- Payan P, Borelli G, Priouzeau F, De Pontual H, Boeuf G, Mayer-Gostan N. 2002. Otolith growth in trout Oncorhynchus mykiss: Supply of Ca2+ and Sr2+ to the saccular endolymph. J Exp Biol 205: 2687–2695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng AW, Effertz T, Ricci AJ. 2013. Adaptation of mammalian auditory hair cell mechanotransduction is independent of calcium entry. Neuron 80: 960–972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng AW, Gnanasambandam R, Sachs F, Ricci AJ. 2016. Adaptation independent modulation of auditory hair cell mechanotransduction channel open probability implicates a role for the lipid bilayer. J Neurosci 36: 2945–2956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pietsch M, Aguirre Dávila L, Erfurt P, Avci E, Lenarz T, Kral A. 2017. Spiral form of the human cochlea results from spatial constraints. Sci Rep 7: 7500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pritchard U. 1881. The cochlea of the Ornithorhynchus platypus compared with that of ordinary mammals and of birds. Proc R Soc Lond 31: 206–211. [Google Scholar]

- Pujol R, et al. 2016. Cochlea: Overview. In Journey into the world of hearing. NeurOreille, Montpellier, France, www.cochlea.eu/en/cochlea. [Google Scholar]

- Rubel EW, Furrer SA, Stone JS. 2013. A brief history of hair cell regeneration research and speculations on the future. Hearing Res 297: 42–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruggero MA, Temchin AN. 2002. The roles of the external, middle, and inner ears in determining the bandwidth of hearing. Proc Natl Acad Sci 99: 13206–13210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell IJ. 2014. Roles for prestin in harnessing the basilar membrane to the organ of Corti. In Insights from comparative hearing research (ed. Köppl C, et al. ), pp. 37–67. Springer, New York. [Google Scholar]

- Ryals BM, Dent ML, Dooling RJ. 2013. Return of function after hair cell regeneration. Hearing Res 297: 113–120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt RS, Fernandez C. 1962. Labyrinthine DC potentials in representative vertebrates. J Cell Comp Physiol 59: 311–322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schultz JA, Zeller U, Luo ZX. 2017. Inner ear labyrinth anatomy of monotremes and implications for mammalian inner ear evolution. J Morphol 278: 236–263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith CA, Takasaka T. 1971. Auditory receptor organs of reptiles, birds, and mammals. Contr Sens Physiol 5: 129–178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smolders JWT. 1999. Functional recovery in the avian ear after hair cell regeneration. Audiol Neurootol 4: 286–302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takechi M, Kuratani S. 2010. History of studies on mammalian middle ear evolution: A comparative morphological and developmental biology perspective. J Exp Zool B Mol Dev Evol 314B: 417–433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan X, Pecka JL, Tang J, Okoruwa OE, Zhang Q, Beisel KW, He DZZ. 2011. From zebrafish to mammal: Functional evolution of prestin, the motor protein of cochlear outer hair cells. J Neurophysiol 105: 36–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vater M, Kössl M. 2011. Comparative aspects of cochlear functional organization in mammals. Hearing Res 273: 89–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vater M, Meng J, Fox RC. 2004. Hearing organ evolution and specialization: Early and later mammals. In Evolution of the vertebrate auditory system (ed. Manley GA, et al. ), pp. 256–288. Springer, New York. [Google Scholar]

- Walshe P, Walsh M, McConn Walsh R. 2003. Hair cell regeneration in the inner ear: A review. Clin Otolaryngol 28: 5–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wangemann P, Marcus DC. 2017. Ion and fluid homeostasis in the cochlea. In Understanding the cochlea (ed. Manley GA, et al. ), pp. 253–286. Springer, New York. [Google Scholar]

- Wannaprasert T, Jeffery N. 2015. Variations of mammalian cochlear shape in relation to hearing frequency and skull size. Trop Nat Hist 15: 41–54. [Google Scholar]

- Warchol ME. 2011. Sensory regeneration in the vertebrate inner ear: Differences at the levels of cells and species. Hearing Res 273: 72–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilms V, Köppl C, Söffgen C, Hartmann AM, Nothwang HG. 2016. Molecular bases of K+ secretory cells in the inner ear: Shared and distinct features between birds and mammals. Sci Rep 6: 34203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood JD, Muchinsky SJ, Filoteo AG, Penniston JT, Tempel BL. 2004. Low endolymph calcium concentrations in deafwaddler2J mice suggest that PMCA2 contributes to endolymph calcium maintenance. J Assoc Res Otolaryngol 5: 99–110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Würfel W, Lanfermann H, Lenarz T, Majdani O. 2014. Cochlear length determination using cone beam computed tomography in a clinical setting. Hear Res 316: 65–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]