Many persons in the United States support limiting firearm access for those whose mental illness would place them or others at heightened risk, but less attention has been paid to progressive cognitive impairment and firearm access. For persons with dementia, their family members, and their health care providers, discussions about firearm access strongly parallel discussions about driving. This commentary discusses when persons with dementia need to “give up the keys,” be they to a gun safe or a car, and how to do so.

The estimated number of older persons in the United States with Alzheimer disease is projected to increase from 4.7 million in 2010 to 13.8 million by 2050. An estimated 33% of all adults aged 65 years or older own a gun; another 12% live in a household with someone who does (1). A 1999 study estimated that 60% of persons with dementia (PWDs) live in a household with a firearm (2). If approximately 40% to 60% of households with PWDs also have a firearm, 7.8 to 11.8 million PWDs may live in a home with a firearm by 2050.

Almost all adults in the United States (89%) support limiting firearm access for those whose mental illness would place them or others at heightened risk (1). Less attention has been paid to progressive cognitive impairment and firearm access. For PWDs—and their family members and health care providers—discussions about firearm access strongly parallel discussions about driving (3). When do PWDs need to “give up the keys,” be they to a gun safe or to a car, and how do they do so? We review clinical and other considerations and provide recommendations.

Clinical Considerations

For PWDs, the primary risk for firearm injury is suicide (4): A total of 91% of all firearm deaths in older adults are suicides (4), and firearms are the most common method of suicide among PWDs. Dementia itself may also be a risk factor for suicide.

Persons with dementia who have firearm access may also pose a safety risk to their families and caregivers (3). Delusions about home intruders or confusion about the identity of persons in their lives may lead PWDs to confront family members, health aides, or other visitors. Access to a firearm may increase the potential for injury or death in such a situation. Estimates on the frequency of such confrontations with firearms are not available.

Although family members may underestimate the ability of PWDs to access and use firearms stored in the home, no validated screening tool exists to assess firearm access among cognitively impaired persons. As part of a checklist covering other safety topics, the Alzheimer’s Association suggests asking, “Do you have firearms in your home?”(5). A follow-up may be, “Does the patient have access to any of the firearms?”

The most appropriate time and location for screening is also not well-established. Within the Veterans Health Administration system, firearms are part of the safety assessment recommended when investigating or establishing a dementia diagnosis; other items include driving status, access to power tools, and kitchen safety (6). The Veterans Health Administration recommends that clinicians “counsel the Veteran with dementia and caregiver on firearm safety and encourage restricted access to firearms and ammunition” (6). Advising family members and others not to bring additional firearms into the home of a PWD may be important.

A diagnosis of cognitive impairment or dementia does not in itself mean that a person should not have access to firearms. What most likely matters is the level of cognitive impairment. In a recent review, Patel and colleagues (7) proposed using the clinical dementia rating scale to estimate the stage of dementia and the person’s ability to safely complete complex tasks, including firearm handling (Table).

Table.

Recommendations for Screening and Counseling Based on Dementia Stage*

| Stage of Dementia | Clinical Features | Screening Questions for the Patient and Family/Informant | Recommendations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mild cognitive impairment (CDR scale score, 0.05) | Mild memory loss Objective cognitive deficits on testing Intact ADLs, although these may require more effort |

Is there access to firearms at home? Has the patient’s judgment, insight, or personality changed? Does the patient have depressive symptoms? |

Consider neuropsychological or psychiatric referral for definition and treatment of the condition. Enact interval reassessment of cognition and ability. Consider assessment or training by a firearms specialist (if judgment or insight is not impaired)†. Engage the patient in planning for future changes (e.g., a firearm trust or designating a responsible family member or friend). |

| Mild dementia (CDR scale score, 1) | Moderate memory loss interfering with ≥1 ADL Patients are usually aware of some deficits but lack full insight Possible behavioral symptoms, such as hostility or delusions |

Is there access to firearms at home? Has the patient’s judgment, insight, or personality changed? Does the patient have depressive symptoms? |

Enact interval reassessment of cognition and ability. Educate the patient and family about supervised access to home firearms (check ownership laws in the jurisdiction). Counsel the patient/family to restrict access to firearms if appropriate. If the patient has intact judgment and insight and is willing to be supervised, consider a practical firearms update course. If psychosis or other behavior problems are present or the patient refuses to allow restricted access, consider informing authorities and at-risk persons. |

| Moderate and severe dementia (CDR scale score, 2–3) | Severe memory loss interfering with many ADLs and impairments in visuospatial and executive function and praxis Usually personality and behavior changes May not recognize friends or family |

Is there access to firearms at home? | The patient should not have access to any firearm. Consider immediate risk if the patient has access and behavior, depressive, or personality problems. Family/support system should remove firearms and ensure that restrictions are always present. If the patient does not permit restriction or there is an inadequate family/support system or imminent risk for harm, consider informing authorities and at-risk persons. |

ADL = activity of daily living; CDR = clinical dementia rating.

Adapted from reference 7. See also Morris JC. The clinical dementia rating (CDR): current version and scoring rules. Neurology. 1993;43:2412–4. [PMID: 8232972].

Although Patel and colleagues (7) suggest retraining, no evidence-based standardized assessment or retraining protocol is available.

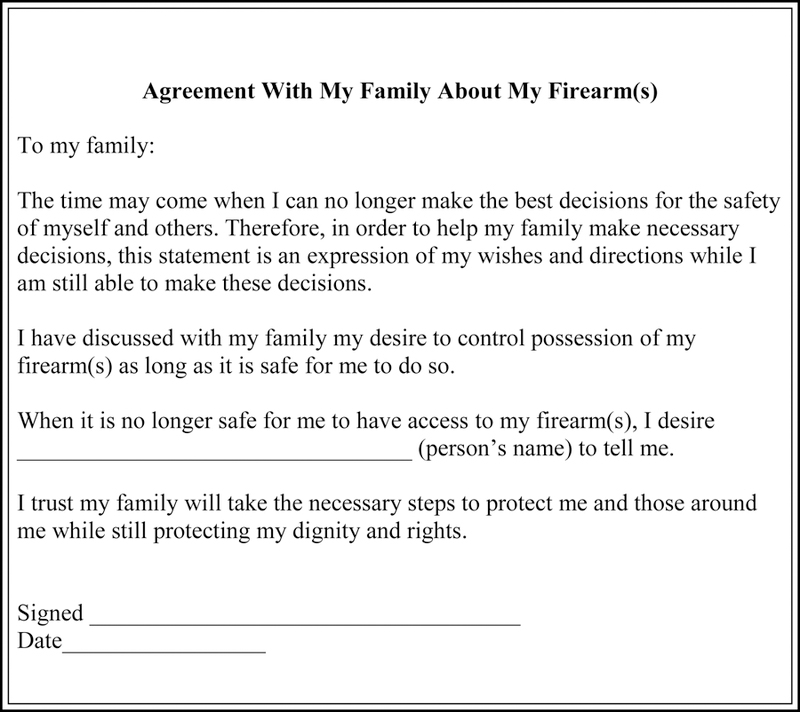

For patients with minimal cognitive impairment, approaches could be similar to those related to driving, including acknowledging the emotions involved and allowing the PWD to maintain agency in the decision for as long as it is safe (8). As with an “advance driving directive” (8), PWDs, their family members, and their health care providers may proactively discuss firearm access and consider setting a “firearm retirement date” (7). This patient-centered approach may allow an older adult to maintain decisional control and identify trusted family members or providers as future surrogate decision makers (Supplement Figure, available at Annals.org). To our knowledge, no one has tested the acceptability or efficacy of such an approach.

Other patients may be explicitly identified—either by themselves or caregivers—as unsafe around firearms. Caregivers for these PWDs have 3 main options: ensure that all guns are securely locked so that the PWD does not have unsupervised access, reduce risk by making guns less lethal (for example, storing them unloaded, replacing live ammunition with blanks, and disabling trigger mechanisms), and remove guns from the home of the PWD. In some states, family members can temporarily store guns at their own house without the background checks otherwise associated with firearm transfers. Other storage sites might include gun shops or ranges, pawn shops, and law enforcement agencies. Unwanted firearms can be disposed of permanently by selling them or giving them away (in both cases, the recipient must be legally allowed to possess a firearm) or giving them to law enforcement. These options vary by location and may require background checks or other paperwork. To our knowledge, data to support firearm training or retraining courses for PWDs (7) are lacking. The Alzheimer’s Association provides materials for family members with specific guidance about firearms, including keeping them locked with ammunition locked separately (5).

Other Considerations

Physicians have the right and duty to inquire of and counsel their patients about health risks and to act to protect their patients and others when circumstances warrant such action in the physician’s professional judgment. As with driving, physicians must balance the welfare and privacy interests of individual patients with the health and safety of patients’ families and the public.

Federal laws do not explicitly prohibit purchase or possession of firearms by PWDs. Among states, only Hawaii and Texas explicitly mention dementia or similar conditions in their firearm statutes. Hawaii prohibits possession by any person under treatment for “organic brain syndromes” (9), which could include dementia or similar neurodegenerative pathologies. In Texas, persons diagnosed with “chronic dementia” are ineligible for a license to carry a handgun in public (10) but may purchase or possess firearms.

Many questions surrounding firearm access in dementia remain unanswered, but the need to address the problem is here now. We believe that a concerted, cooperative effort making the best use of the data at hand can help prevent injuries and deaths while protecting the dignity and rights of older adults.

Appendix Figure.

Sample family firearm agreement. Adapted from www.thehartford.com/sites/thehartford/files/at-the-crossroads-2012.pdf.

Acknowledgments

Financial Support: By the Paul Beeson Career Development Award Program from the National Institute on Aging, American Federation for Aging Research, The John A. Hartford Foundation, and The Atlantic Philanthropies (grants K23AG043123 and K08AG048321); the Heising-Simons Foundation (grant 2016-219); and the National Institute of Mental Health (grant K23 MH095866). No sponsor had any direct involvement in the study design, methods, participant recruitment, data collection, analysis, or manuscript preparation.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: Disclaimer: The contents of this article are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the funding agencies.

Contributor Information

Marian E. Betz, University of Colorado School of Medicine; Denver, Colorado.

Alexander D. McCourt, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health; Baltimore, Maryland.

Jon S. Vernick, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health; Baltimore, Maryland.

Megan L. Ranney, Rhode Island Hospital/Alpert Medical School and Brown University; Providence, Rhode Island.

Donovan T. Maust, VA Ann Arbor Healthcare System; Ann Arbor, Michigan.

Garen J. Wintemute, University of California, Davis, School of Medicine; Sacramento, California.

References

- 1.Parker K, Horowitz J, Ingielnik R, Oliphant B, Brown A. America’s complex relationship with guns Pew Research Center. 22 June 2017. Accessed at www.pewsocialtrends.org/2017/06/22/americas-complex-relationship-with-guns on 10 October 2017.

- 2.Spangenberg KB, Wagner MT, Hendrix S, Bachman DL. Firearm presence in households of patients with Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias. J Am Geriatr Soc 1999;47:1183–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Greene E, Bornstein BH, Dietrich H. Granny, (don’t) get your gun: competency issues in gun ownership by older adults. Behav Sci Law 2007;25:405–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. WISQARS (Web-based Injury Statistics Query and Reporting System) 2017. Accessed at www.cdc.gov/injury/wisqars/index.html on 29 June 2017.

- 5.Alzheimer’s Association. Staying safe 2007. Accessed at https://www.alz.org/national/documents/brochure_stayingsafe.pdf on April 4, 2018

- 6.U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. VHA Dementia Steering Committee recommendations for dementia care in the VHA health care system 2016. Accessed at www.va.gov/GERIATRICS/docs/VHA_DSC_RECOMMENDATIONS_SEPT_2016_9-12-16.pdf on 10 October 2017.

- 7.Patel D, Syed Q, Messinger-Rapport BJ, Rader E. Firearms in frail hands: an ADL or a public health crisis! Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen 2015;30:337–40. doi: 10.1177/1533317514545867 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Betz ME, Scott K, Jones J, Diguiseppi C. “Are you still driving?” Metasynthesis of patient preferences for communication with health care providers. Traffic Inj Prev 2016;17:367–73. doi: 10.1080/15389588.2015.1101078 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. HAW. REV. STAT. § 134–7(c) 1988.

- 10. TEX. GOV’T. CODE § 411.172(e)(5)(C) 1999.