Abstract

Objective

We investigated the benefit of Impella, a modern percutaneous mechanical support (pMCS) device, versus former standard intra-aortic balloon pump (IABP) in acute myocardial infarction complicated by cardiogenic shock (AMICS).

Methods

This single-centre, retrospective study included patients with AMICS receiving pMCS with either Impella or IABP. Disease severity at baseline was assessed with the IABP-SHOCK II score. The primary outcome was all-cause mortality at 30 days. Secondary outcomes were parameters of shock severity at the early postimplantation phase. Adjusted Cox proportional hazards models identified independent predictors of the primary outcome.

Results

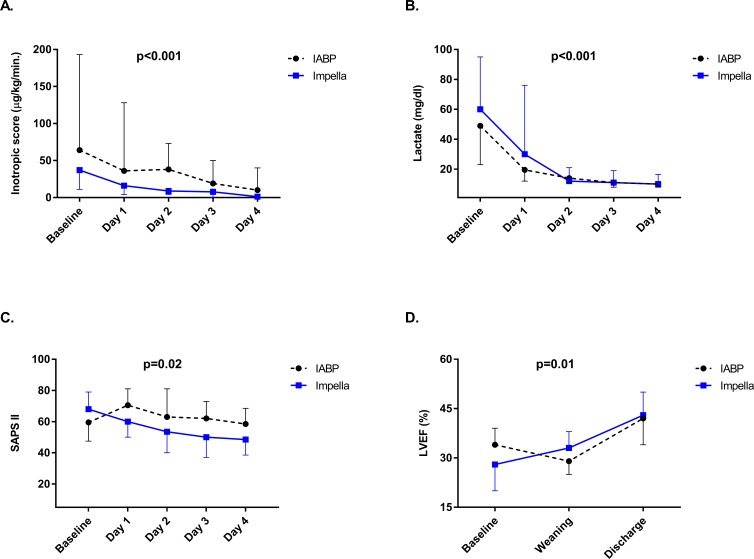

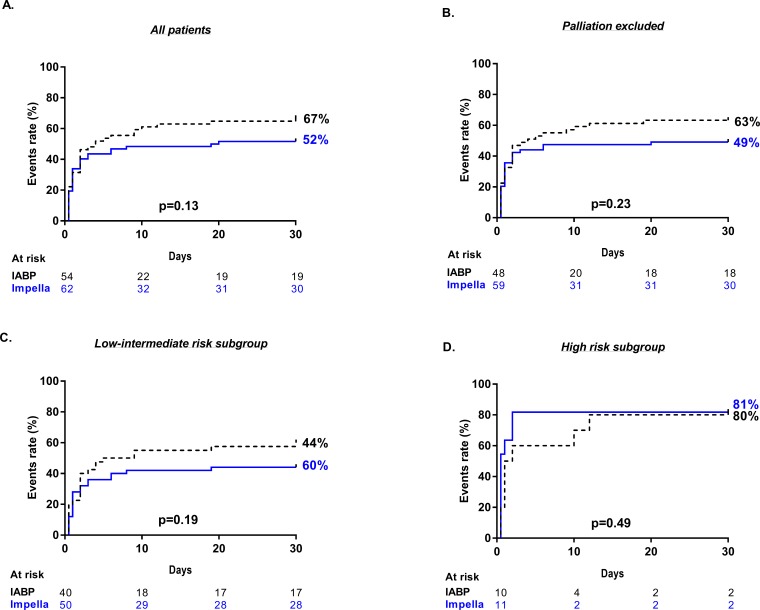

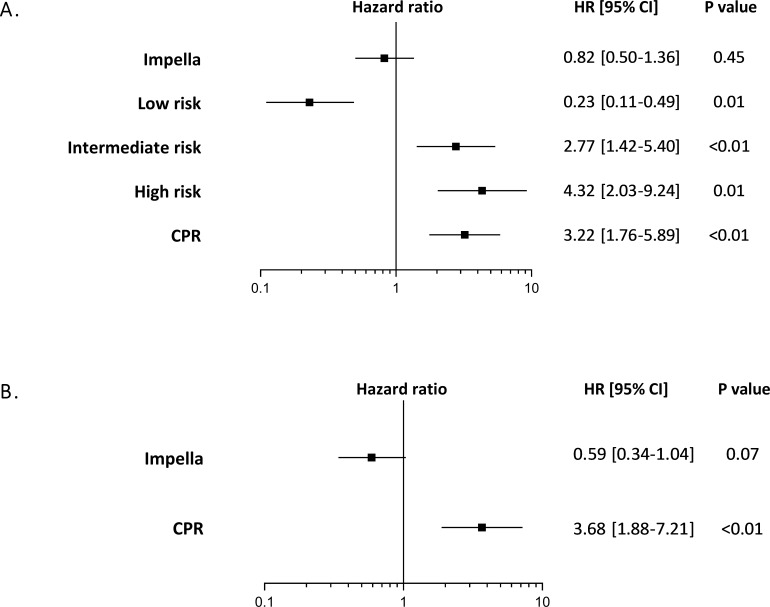

Of 116 included patients, 62 (53%) received Impella and 54 (47%) IABP. Despite similar baseline mortality risk (IABP-SHOCK II high-risk score of 18 % vs 20 %; p = 0.76), Impella significantly reduced the inotropic score (p < 0.001), lactate levels (p < 0.001) and SAPS II (p = 0.02) and improved left ventricular ejection fraction (p = 0.01). All-cause mortality at 30 days was similar with Impella and IABP (52 % and 67 %, respectively; p = 0.13), but bleeding complications were more frequent in the Impella group (3 vs 4 units of transfused erythrocytes concentrates due to bleeding complications, p = 0.03). Previous cardiopulmonary resuscitation (HR 3.22, 95% CI 1.76 to 5.89; p < 0.01) and an estimated intermediate (HR 2.77, 95% CI 1.42 to 5.40; p < 0.01) and high (HR 4.32 95% CI 2.03 to 9.24; p = 0.01) IABP-SHOCK II score were independent predictors of all-cause mortality.

Conclusions

In patients with AMICS, haemodynamic support with the Impella device had no significant effect on 30-day mortality as compared with IABP. In these patients, large randomised trials are warranted to ascertain the effect of Impella on the outcome.

Keywords: impella, IABP, cardiogenic shock, mechanical support, myocardial infarction

Key messages.

What is already known on this subject?

To date, none of the available mechanical circulatory support devices significantly improves 30-day mortality in patients with cardiogenic shock due to acute myocardial infarction.

What does this study add?

Impella improves parameters of shock severity but is associated with higher bleeding complications and has no significant effect on 30-day mortality compared with the use of IABP.

How might this impact on clinical practice?

The benefit of Impella on mortality should be evaluated in an adequately powered randomised controlled trial.

Introduction

Acute myocardial infarction complicated by cardiogenic shock (AMICS) remains an important cause of death, despite early percutaneous coronary revascularisation.1 Recent data show that in these patients, in-hospital mortality reaches 66% and long-term mortality 80%.2

In patients with AMICS, the intra-aortic balloon pump (IABP) was used for mechanical support for decades, but it was downgraded from the guideline recommendations after the IABP-SHOCK II trial failed to show any mortality benefit over medical therapy alone.3 4 Impella (Abiomed, Danvers, Massachusetts, USA) is a promising alternative for percutaneous mechanical circulatory support (pMCS) that has been utilised as a bridge to recovery. It consists of a miniaturised axial flow pump fitted onto a pigtail catheter, pumping blood from the left ventricle into the ascending aorta and providing a cardiac output of 2.5 L/min (Impella 2.5) and up to 4.0 L/min (Impella CP).5 6 It actively unloads the left ventricle reducing the stroke-work and myocardial oxygen consumption, thereby providing cardioprotection and robust haemodynamic support.7–9

Two randomised controlled trials (RCT) and a metanalysis of RCTs investigated the benefit of Impella versus IABP, but they were highly underpowered to detect a mortality difference.10–12 Moreover, as noted from the investigators of those trials, RCTs in the setting of AMICS are extremely difficult to conduct. Therefore, the profile of patients who may profit from support with Impella still remains unclear.

The aim of our study was to investigate the effect of Impella compared with IABP in patients with AMICS in terms of improvement of parameters of shock severity and all-cause mortality at 30 days.

Methods

Study design and data collection

This retrospective study included patients with AMICS, who were treated with either Impella or IABP, from a historical cohort of two tertiary cardiovascular centres of the Charité-University Medicine in Berlin. Patients treated between January 2011 and March 2017 were included in the study. Data at baseline and at 30-day follow-up were collected from a computerised patient information system (COPRA Systems, Germany). The local ethics committee approved data collection. The results of the study are reported in accordance with the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology guidelines.13

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Inclusion

Patients with AMICS due to ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) or non-STEMI (NSTEMI), with symptom onset within 24 hours of clinical presentation, were included. The shock was defined by the need for continuous administration of vasopressors for >30 min in order to maintain a systolic blood pressure of >90 mm Hg, despite adequate fluid loading, evidence of end-organ hypoperfusion, clinical or radiological signs of pulmonary congestion and lactate serum concentration at clinical presentation >20 mg/dL.4

Exclusion

Exclusion criteria were: contraindication for device implantation, resuscitation lasting >30 min, presence of left ventricular thrombus, presence of a mechanical aortic valve, severe aortic valve stenosis, severe peripheral arterial disease precluding placement of Impella, significant right heart failure, presence of an atrial or ventricular septal defect including postinfarction ventricular septal defect, left ventricular rupture and cardiac tamponade. Online supplementary file 1 depicts the patient selection process.

openhrt-2018-000987supp001.pdf (222.4KB, pdf)

Interventional and device therapy

The characteristics of IABP and Impella are described elsewhere.14 Operators were experienced in the use of both devices. Patients with AMICS underwent primary percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) of the culprit lesion in accordance with current local guidelines.15 16 In presence of multivessel disease, the modality of revascularisation, that is, immediate versus staged PCI of the non-culprit lesion(s), was left to the discretion of the operator. Duration of mechanical support was guided by the treating intensive care physician. Weaning was achieved by a stepwise reduction of the amount of support provided by the pMCS device. In 2013, following the publication of the IABP-SHOCK II trial, the use of IABP was terminated and replaced by Impella.

Outcomes

The primary outcome was all-cause mortality at 30 days. Other outcomes were adverse cardiac events during hospitalisation, such as myocardial infarction (MI), target vessel revascularisation (TVR), stroke, and changes in parameters of shock severity (ie, improvement of cardiac power index (CPI), left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF), serum lactate levels, and Simplified Acute Physiology Score II (SAPS II)), reduction in the ICU stay and duration of device therapy. The recently published IABP-SHOCK II score, a short-term mortality risk score, derived from patients included in the IABP-SHOCK II trial,17 was calculated in each patient, allowing the exploration of Impella effect on outcomes in each risk subcategory. The inotropic score and CPI were calculated over the first 5 days, as previously described.18 LVEF was measured at admission, at the time of device weaning and at discharge by transthoracic echocardiography. Pre-PCI time interval was defined as the time interval from symptom onset to the first PCI balloon inflation. The pre-device time interval was defined as the time interval from symptom onset to device implantation. The bleeding complications were classified according to the Bleeding Academic Research Consortium (BARC) classification.19

Statistical analysis

Data are expressed as medians with interquartile ranges (IQR) or frequencies and percentages, as appropriate. Normality of distribution was testes with the Shapiro-Wilk test. Wilcoxon rank sum for was used for comparisons of non-parametric variables and the Χ² test for categorical variables. Changes within the first 5 days for parameters of shock severity (CPI, inotropic score, lactate and SAPS II) and from baseline to discharge for LVEF were analysed using a generalised linear-mixed model considering the between and within-patient differences. Kaplan-Meier analysis estimated the cumulative incidence of mortality at 30 days. Cox-regression analysis was performed to identify independent predictors of 30-day mortality while adjusting for potential confounding variables (IABP-SHOCK II risk score and cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR)). To assess the validity of the Cox proportional hazard model, the proportional assumption hazard was tested based on Schoenfeld residuals. All probability values were two-tailed and considered significant for p<0.05. Data analysis was performed using STATA V.14.0 statistical software.

Results

Baseline and procedural characteristics

Out of 116 included patients, 62 (53%) received Impella and 54 (47%) IABP. Table 1 outlines the baseline characteristics of all patients and according to the device received. The median age in the entire cohort was 72 years (IQR, 64–77) and 73% were men. Demographic characteristics and cardiovascular risk factors were similarly distributed among groups, except for the history of smoking, significantly more frequent in the IABP group. STEMI was the most frequent index event in both groups (Impella vs IABP: 68% vs 74%; p=0.54). No significant differences regarding comorbidities, rate of out of or in-hospital CPR or the type of index event (ie, NSTEMI and STEMI) were observed. At the time of index event, 50% of patients presented in sinus rhythm, 22% in ventricular fibrillation and 11% in supraventricular arrhythmia (online supplementary file 1). Overall, no significant difference in the rate of different types of cardiac rhythm was observed. The baseline estimated short-term mortality risk, calculated using the IABP-SHOCK II score, was comparable among groups (table 2). The periprocedural characteristics are outlined in table 3. At baseline, patients treated with Impella had significantly worse LVEF (28 [20-35] vs 34 [30-39] %; p=0.01), and comparable SAPS II and serum lactate levels (60 [32-95] vs 49 [23-77] mg/dL; p=0.09). The size of MI was significantly higher in patients receiving Impella (CK-max 2822 [887–6355] vs 1330 [473–4626] U/L; p=0.04). There was no significant difference in the rate of device implantations before stenting (55% vs 54%; p=1.00), time to device implantation (144 vs 121 min; p=0.17) and postinterventional TIMI III flow rates (77% vs 60%, p=0.07) in patients treated with Impella versus IABP.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics

| Total (N=116) |

IABP (N=54) |

Impella (N=62) |

P value | |

| Age, years | 72(64–77) | 71(64–75) | 73(62–79) | 1.00 |

| Male | 85 (73) | 41 (76) | 44 (71) | 0.67 |

| BMI | 26(24–29) | 26(24–29) | 26(25–29) | 0.63 |

| Smoke | 29 (25) | 19 (35) | 10 (16) | 0.02 |

| Hypertension | 70 (60) | 34 (63) | 36 (58) | 0.70 |

| Hyperlipidaemia | 74 (64) | 38 (70) | 36 (58) | 0.18 |

| NIDDM | 52 (45) | 20 (37) | 32 (51) | 0.11 |

| Previous stroke | 7 (6.0) | 3 (3.7) | 5 (8.1) | 0.44 |

| Peripheral artery disease | 5 (4.3) | 3 (5.6) | 2 (3.2) | 0.66 |

| Previous MI | 18 (16) | 7 (13) | 11 (18) | 0.61 |

| Previous PCI | 22 (19) | 7 (13) | 15 (24) | 0.15 |

| One-vessel CAD | 18 (16) | 7 (13) | 11 (18) | 0.35 |

| Two-vessel CAD | 27 (23) | 12 (22) | 15 (24) | 0.35 |

| Three-vessel CAD | 68 (59) | 35 (65) | 33 (53) | 0.35 |

| CABG | 3 (2.6) | 0 (0) | 3 (4.9) | 0.24 |

| Pre-existing cardiomyopathy | 6 (5.2) | 3 (5.5) | 1 (1.6) | 0.45 |

| Pacemaker/CRT | 5 (4.3) | 1 (1.8) | 4 (6.5) | 0.37 |

| CKD | 20 (17) | 8 (15) | 12 (19) | 0.62 |

| CPR | 70 (60) | 32 (59) | 38 (61) | 0.45 |

| In hospital CPR | 38 (54) | 21 (66) | 17 (45) | 0.10 |

| Out of hospital CPR | 32 (46) | 11(34) | 21 (55) | 0.10 |

| Index event AMI | ||||

| STEMI | 82 (71) | 40 (74) | 42 (68) | 0.54 |

| NSTEMI | 34 (29) | 14 (26) | 20 (32) | 0.45 |

Data depicted as median (IQR) or counts (%). P values are from Wilcoxon rank sum test or Fischer test.

AMI, acute myocardial infarction; BMI, body mass index; CABG, coronaryartery bypass graft; CAD, coronary artery disease; CKD, chronic kidney disease; CPR, cardiopulmonary resuscitation; CRP, C reactive protein; CRT, cardiac resynchronization therapy; IABP-SHOCK II, Intra-aortic Balloon Pump in Cardiogenic Shock II; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase; MI, myocardial infarction; NIDDM, non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; Pre-PCI time, time from symptom onset to the first PCI balloon inflation; Pre-device time, time from symptom onset to device implantation.

Table 2.

IABP-SHOCK II risk score

| Score | Total (N=116) |

IABP (N=54) |

Impella (N=62) |

P value |

| Low (0–2) | 40 (36) | 17 (34) | 23 (38) | 0.68 |

| Intermediate (3–4) | 50 (45) | 23 (46) | 27 (44) | 0.85 |

| High (5–9) | 21 (19) | 10 (20) | 11 (18) | 0.79 |

Data depicted as counts (%). P values are from the Fischer test. Data on the IABP-SHOCK II risk score was notretrievable for five patients.

IABP-SHOCK II, Intra-aortic Balloon Pump in Cardiogenic Shock II.

Table 3.

Periprocedural characteristics

| IABP (N=54) |

Impella (N=62) |

P value | |

| LVEF | 34(30-39) | 28(20-35) | 0.01 |

| SAPS II | 60(48-74) | 68(47-79) | 0.16 |

| Lactate, mg/dL | 49(23-77) | 60(32-95) | 0.09 |

| Creatinine, mg/dL | 1.37 (1.08–1.89) | 1.39 (1.14–1.75) | 0.93 |

| pH | 7.22 (7.12–7.36) | 7.25 (7.12–7.35) | 0.59 |

| Haemoglobin, g/dL | 13.7 (11.8–14.6) | 13.5 (12.1–14.3) | 0.86 |

| Glucose, mg/dL | 302 (226–407) | 340 (261–429) | 0.18 |

| CK-max., U/L | 1330 ([473–4626) | 2822 (887–6355) | 0.04 |

| CK-MB max., U/L | 221 (68–544) | 336 (109–680) | 0.19 |

| Pre-PCI time, min | 121 (60–196) | 111 (71–262) | 0.42 |

| Pre-device time, min | 121 (82–228) | 144(107–364) | 0.17 |

| Device implantation before stenting | 29 (54) | 34 (55) | 1.00 |

| TIMI flow at baseline | |||

| TIMI 0 | 34 (63) | 41 (66) | 0.85 |

| TIMI I | 12 (22) | 17 (27) | 0.17 |

| TIMI II | 8 (15) | 4 (6.5) | 0.22 |

| TIMI III flow after primary PCI* | 31 (60) | 47 (77) | 0.07 |

Data depicted as median (IQR) or counts (%). P values are from Wilcoxon rank sum test or Fischer test.

*Data on TIMI III flow after PCI were not retrievable for two patients in the IABP and one patient in the Impella group.

CK-MB, Creatine kinase isoform MB; CK-max, maximal creatine kinase; CPR, cardiopulmonary resuscitation; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; SAPS II, Simplified Acute Physiology Score II; TIMI, thrombolysis in myocardial infarction.

Characteristics during hospitalisation

Clinical and procedural characteristics during the stay at the intensive care unit (ICU) are summarised in table 4. Overall, >90% of patients in both groups were mechanically ventilated for a median of 24 and 36 hours in the Impella and IABP group, respectively. In each group, 39% of patients received renal replacement therapy (RRT). The median duration of pMCS was 24 (12-36) hours in both groups, and more than half of were successfully weaned from each device (60% and 55%, Impella vs IABP, respectively). No significant difference regarding the duration of mechanical ventilation, RRT, ICU stay and rate of device-triggered arrhythmias was observed. Although the use of catecholamines at admission and during the ICU stay was initially high for both devices, significantly faster weaning within the first 4 days was achieved in patients treated with Impella (figure 1A) However, the overall increase of CPI was not significantly different between the two groups (online supplementary file 1). Compared with patients treated with IABP, those treated with Impella displayed a significant reduction of lactate levels and SAPS II within the first 4 days after device implantation (figure 1B, C). Moreover, following Impella treatment, LVEF improved significantly from baseline to discharge (figure 1D).

Table 4.

Clinical and procedural characteristics at the ICU

| IABP (N=54) |

Impella (N=62) |

P value | |

| Mechanical ventilation | 51 (94) | 60 (96) | 0.66 |

| Duration of mechanical ventilation, hours | 36(12–168) | 24(12–216) | 0.73 |

| Renal replacement therapy | 21 (39) | 24 (39) | 1.00 |

| Duration of dialysis, hours | 48(24–84) | 36(12–240) | 0.95 |

| Duration of device therapy, hours | 24(12–36) | 24(12–36) | 0.74 |

| Days of ICU stay | 3(1–11) | 3.5(1–18) | 0.57 |

| Successful weaning | 30 (55) | 36 (60) | 0.70 |

| Arrhythmias during device-therapy | 17 (32) | 17 (27) | 0.68 |

| Supraventricular tachycardia | 7 (13) | 7 (11) | 0.78 |

| Ventricular tachycardia | 4 (7.4) | 6 (9.7) | 0.75 |

| Ventricular fibrillation | 5 (9.2) | 2 (3.2) | 0.24 |

| Bradycardia | 2 (3.7) | 3 (4.8) | 1.00 |

Data depicted as median [IQR] or counts (%). P values are from Wilcoxon rank sum or Fischer’s test.

IABP, intra-aortic balloon pump; ICU, intensive care unit.

Figure 1.

Changes in clinical parameters and use of catecholamines during hospitalisation (A) inotropic score, B) serum lactate levels and (C) SAPS II from baseline to the fourth day after device implantation, and (D) LVEF from baseline to discharge are depicted. measurements are presented as median and 25th–75th percentile. P values are from a generalised linear model considering the between and within difference among groups. The catecholamine dose was evaluated by the inotropic score (µ/kg/min.)=dopamine+dobutamine +100*epinephrine +100*norepinephrine +100*isoproterenol. IABP, intra-aortic balloon pump; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; SAPS II, Simplified Acute Physiology Score II.

Feasibility and safety

Both devices were successfully implanted in all patients. The balloon size of the IABP was 40 cm3. An Impella 2.5 was implanted in 19 (31%) and an Impella CP in 43 (69%) patients. The complications occurring from the time of device implantation until discharge are summarised in table 5. Rates of stroke, MI and TVR were similar in both groups (Impella vs IABP: 1.6% vs 1.8, p=1.00; 1.6% vs 5.5%, p=0.48% and 3.2% vs 0%, p=0.43). No significant differences in the rate of pericardial effusion (1.6% vs 5.5%, p=0.33) or cardiac tamponade requiring intervention (3.2% vs 3.7%, p=1.00) were observed. Furthermore, rates of bleeding BARC 2 and 3, (14.5% vs 7.4%, p=0.25) and limb ischaemia (8% vs 0%, p=0.06) were similar among the device groups but showed a strong trend of higher frequency in Impella-treated patients. Moreover, the number of transfused erythrocytes concentrates due to bleeding complications was significantly higher following the Impella placement (4 vs 3 units, p=0.03).

Table 5.

Complications

| IABP (N=54) |

Impella (N=62) |

P value | |

| Stroke | 1 (1.8) | 1 (1.6) | 1.00 |

| MI | 3 (5.5) | 1 (1.6) | 0.48 |

| TVR | 0 (0) | 2 (3.2) | 0.43 |

| Pericardial effusion | 3 (5.5) | 1 (1.6) | 0.33 |

| Pericardial tamponade | 2 (3.7) | 2 (3.2) | 1.00 |

| Limb ischaemia | 0 (0) | 5 (8.0) | 0.06 |

| Bleeding BARC 2 and 3 | 4 (7.4) | 9 (14.5) | 0.25 |

| Number of RBCs | 3(2-4) | 4(4-7) | 0.03 |

| Number of FFPs | 4(2-6) | 2(2-7) | 0.60 |

Data depicted as median (IQR) or counts (%). P-values are from Wilcoxon rank sum or Fischer test.

BARC 2, Bleeding Academic Research Consortium type 2; BARC 3, Bleeding Academic Research Consortium type 3; FFP, fresh frozen plasma; MI, myocardial infarction; RBC, red blood concentrate; TVR, target vessel revascularisation.

Outcomes at 30 days

Mortality at 30 days and detailed causes of death are depicted in the online supplementary file 1. Overall, all-cause mortality was 59%, with no significant differences between the Impella and IABP group (52% and 67%, p=0.13). The most frequent cause of death in both groups was heart failure from AMICS (43%). Notably, numerically fewer patients died of heart failure from AMICS in the Impella-treated group (36% and 52%, p=0.09; online supplementary file 1). Other causes of death were multiorgan failure due to systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS, Impella 11% and IABP 5.5%-; p=0.33), and palliation from irreversible postanoxic brain damage (4.8% and 9.3%, p=0.47). Overall, 6.9% of patients underwent palliation for irreversible postanoxic brain damage with no significant differences among the treatment groups (4.8% and 9.3%, p=0.47). In a subgroup analysis, after excluding deaths from palliation due to postanoxic brain damage, 30-day mortality due to heart failure from AMICS, did not reach statistical significance in Impella-treated patients (37% and 57%, p=0.05, online supplementary file 1. In Kaplan-Meier analysis, all-cause mortality did not differ between the two treatment groups, regardless of whether patients undergoing palliation were (p=0.13, figure 2A) or were not (p=0.23, figure 2B) included in the analysis. After stratification according to the baseline estimated IABP-SHOCK II risk score, no survival benefit of Impella was observed in either subgroup (figure 2C, D).

Figure 2.

Kaplan-Meier estimates of all-cause mortality at 30 days. Depicted are the Kaplan-Meier estimates of all-cause mortality at 30 days. P-values from the log-rank test. events were analysed (A) in the whole study population, (B) after excluding deaths due to palliation by irreversible postanoxic brain damage, (C) in the low-intermediate and (D) high IABP-SHOCK II risk score subgroup. IABP-SHOCK II, Intra-aortic Balloon Pump in Cardiogenic Shock II.

Independent predictors of 30-day mortality

In multivariate analysis, treatment with Impella showed no significant effect on mortality (HR 0.82, 95% CI 0.50 to 1.36; p=0.45). Previous CPR (HR 3.22, 95% CI 1.76 to 5.89; p<0.01) and estimated, intermediate (HR 2.77, 95% CI 1.42 to 5.40; p<0.01) and high (HR 4.32 95% CI 2.03 to 9.24; p=0.01) IABP-SHOCK II risk score, considerably increased the risk of mortality (figure 3A). In the subgroup of patients with estimated low-intermediate risk, no significant effect on mortality after treatment with Impella was observed (HR 0.59, 95% CI 0.34 to 1.04; p=0.07; figure 3B).

Figure 3.

Independent predictors of all-cause mortality at 30 days. (HRs are from COX regressions with 95% CIs). Events were analysed (A) in the whole study population and (B) in the subgroup of patientswith low-intermediate IABP-SHOCK II score. adjustment covariates including IABP-SHOCK II risk score and CPR. CPR, cardiopulmonary resuscitation; IABP-SHOCK II, Intra-aortic Balloon Pump in Cardiogenic Shock II.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is one of the largest historical cohorts investigating the benefit of haemodynamic support with Impella versus IABP in patients with severe AMICS.

The following findings emerged from our study. First, compared with IABP, treatment with Impella significantly improves parameters of shock severity and LVEF. Second, at 30 days, there is no significant benefit in all-cause mortality compared with IABP. Third, there is no significant increase in rates of stroke, reinfarction and TVR but treatment with Impella was associated with a significantly higher number of transfused erythrocytes concentrates due to bleeding complications.

AMICS is a complex disease, still associated with a mortality of 40%–75% despite early revascularisation.20 Impella has been frequently used in this clinical setting due to its feasibility and safety in emergency conditions and the benefits of ventricular unloading, supported from preclinical and clinical data.7 9 21 Superior haemodynamic support provided by Impella explains the significant reduction of lactate levels and SAPS II and the lower inotropic scores observed in our study. However, the CPI, length of ICU stay, the rate of mechanical ventilation and that of RRT were not different from patients treated with IABP. The onset of multiorgan failure due to SIRS, occurring in 11% of patients receiving Impella versus 5.5% of those receiving IABP, might have obscured the beneficial effects provided by the latter. The results of our study are in line with those of the Impella versus Intra-Aortic Balloon Pump in Cardiogenic Shock trial, a metanalysis of existing RCTs, and a recent multicentre retrospective registry, all demonstrating the lack of benefit of Impella in reducing 30 day mortality.11 22 23 These studies included patients presenting in different stages of shock severity, while to date, the profile of patients with AMICS who may profit from pMCS remains still unclear. In fact, a benefit in terms of reduction in 30-day mortality with Impella, as compared with standard medical therapy or IABP, has not been shown in any clinical setting and for any pMCS for that matter. AMICS is indeed a condition with broad severity of presentation. Approximately 50% of patients survive AMICS without pMCS,4 on the contrary, pMCS might be futile in others because of the advanced state of disease. Therefore, an accurate risk stratification early in this emergency setting can help guide further clinical decision and refine patient selection towards achieving a real benefit from pMCS devices. Previous studies suggested a protective effect exerted by Impella in ‘lower risk’ patients.24 According to the results of the recently published ‘Detroit Cardiogenic Shock Initiative’, the rapid delivery of Impella was beneficial in patients presenting in a still responsive shock stage. The authors implemented a regional protocol based on rapid early delivery of pMCS within 90 min of shock onset and early discontinuation of inotropic and vasopressors, being able to show an improvement of mortality compared with institutional historical cohorts.24 In our study, we did not find a significant difference in 30-day mortality after stratifying the patients according to the IABP-SHOCK II risk score. In fact, the estimated mortality rate in the low-intermediate risk group was approximately 60%–70%, reflecting the bailout character of Impella use in these patients with poor a haemodynamic profile. Although in the Detroit study the cohort was highly preselected, the results of the study indicate that in ‘lower-risk‘ patients, the benefits of early pMCS implantation merit further investigation in appropriately powered trials.

In patients with high IABP-SHOCK II risk score, support with Impella is clearly futile. In this clinical setting, it was recently shown that the combination of Impella and venoarterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (VA-ECMO) provides a more robust haemodynamic support and is superior to VA-ECMO alone.18

The present study has several limitations. First, due to the nature of the retrospective design, comprehending patients from a historical cohort, residual confounding cannot be excluded even after multivariable adjustments. Second, despite being considerable compared with other studies, the size of our cohort was insufficient to detect significant differences in mortality. Finally, despite applying strict criteria for patient selection, there was some degree of heterogeneity, probably due to the lack of evidence in the use of pMCS devices.

In conclusion, the debate on Impella is still ongoing, in a scenario where, the mortality benefit of any available percutaneous device has still to be proven in an RCT. Due to the difficulty of conducting trials in this emergency setting, data from observational studies are important and should serve at least as hypothesis generating. In this large retrospective study, we observed that haemodynamic support with Impella is feasible and improves the parameters of shock severity compared with former standard IABP. Impella does not improve 30-day mortality, however, a possible benefit in selected patients with lower estimated mortality risk should be investigated in adequately powered RCTs.

Data depicted as median (IQR) or counts (%). P values are from Wilcoxon rank sum or Fischer’s test. AMI-acute myocardial infarction, BMI-Body Mass Index, CABG-coronary artery bypass graft, CAD-coronary artery disease, CKD-chronic kidney disease, CPR-cardiopulmonary resuscitation, CRP-C-reactive Protein, CRT-cardiac resynchronization therapy, IABP-SHOCK II- short-term mortality risk score, LDH-Lactate Dehydrogenase, MI-myocardial infarction NIDDM-non-insulin dependent diabetes mellitus, PCI-percutaneous coronary angioplasty, Pre-PCI time-time from symptom onset to the first PCI balloon inflation, Pre-device time-time from symptom onset to device implantation.

Data depicted as counts (%). P values are from Fischer’s test. IABP-SHOCK II-Intra-aortic Balloon Pump in Cardiogenic Shock II. Data on the IABP Shock II risk score was not retrievable for five patients.

Data depicted as median (IQR) or counts (%). P values are from Wilcoxon rank sum or Fischer’s test. CK-max.-maximal Creatine-Kinase, CK-MB-Creatine-Kinase Isoform MB, CPR-cardiopulmonary resuscitation, LVEF-left ventricular ejection fraction (%), TIMI-Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction. SAPS II-Simplified Acute Physiology Score II. * Data on TIMI III flow after PCI was not retrievable for two patients in the IABP and one patient in the Impella group.

Data depicted as median (IQR) or counts (%). P values are from Wilcoxon rank sum or Fischer’s test. ICU- Intensive care unit.

Data depicted as median (IQR) or counts (%). P values are from Wilcoxon rank sum or Fischer’s test. BARC 2 and 3-Bleeding Academic Research Consortium type 2 and 3, FFP-Fresh Frozen Plasma, MI-myocardial infarction, RBC-Red Blood Concentrate, TVR-target vessel revascularisation.

Footnotes

FK and CS contributed equally.

Contributors: BA, CS and FK designed and implemented the study, supervised the statistical analysis and drafted the final manuscript; AD, GF, WK, TW, CM collected the data; LD, ES, BP and UL critically revised the manuscript.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT: Dr Carsten Skurk has perceived lecturer fees from Abiomed, outside the submitted work. Dr Landmesser reports grants from Edwards Lifesciences, grants and personal fees from Abbott, outside the submitted work. All other authors report no relationships relevant to the contents of this paper to disclose.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as supplementary information.

References

- 1. Kolte D, Khera S, Aronow WS, et al. Trends in incidence, management, and outcomes of cardiogenic shock complicating ST-elevation myocardial infarction in the United States. J Am Heart Assoc 2014;3:e000590 10.1161/JAHA.113.000590 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Blumenstein J, de Waha S, Thiele H. Percutaneous ventricular assist devices and extracorporeal life support: current applications. EuroIntervention 2016;12:X61–X67. 10.4244/EIJV12SXA12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Kolh P, Windecker S, Alfonso F, et al. 2014 ESC/EACTS guidelines on myocardial revascularization: the task Force on myocardial revascularization of the European Society of cardiology (ESC) and the European association for Cardio-Thoracic surgery (EACTS). developed with the special contribution of the European association of percutaneous cardiovascular interventions (EAPCI). Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2014;46:517–92. 10.1093/ejcts/ezu366 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Thiele H, Zeymer U, Neumann F-J, et al. Intra-aortic balloon counterpulsation in acute myocardial infarction complicated by cardiogenic shock (IABP-SHOCK II): final 12 month results of a randomised, open-label trial. Lancet 2013;382:1638–45. 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61783-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Meyns B, Stolinski J, Leunens V, et al. Left ventricular support by catheter-mounted axial flow pump reduces infarct size. J Am Coll Cardiol 2003;41:1087–95. 10.1016/S0735-1097(03)00084-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Thiele H, Ohman EM, Desch S, et al. Management of cardiogenic shock. Eur Heart J 2015;36:1223–30. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehv051 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kapur NK, Paruchuri V, Urbano-Morales JA, et al. Mechanically unloading the left ventricle before coronary reperfusion reduces left ventricular wall stress and myocardial infarct size. Circulation 2013;128:328–36. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.112.000029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Sjauw KD, Remmelink M, Baan J, et al. Left ventricular unloading in acute ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction patients is safe and feasible and provides acute and sustained left ventricular recovery. J Am Coll Cardiol 2008;51:1044–6. 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.10.050 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Esposito ML, Zhang Y, Qiao X, et al. Left ventricular unloading before Reperfusion promotes functional Recovery after acute Myocardial Infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol 2018;72:501–14. 10.1016/j.jacc.2018.05.034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Ouweneel DM, Engstrom AE, Sjauw KD, et al. Experience from a randomized controlled trial with Impella 2.5 versus IABP in STEMI patients with cardiogenic pre-shock. Lessons learned from the IMPRESS in STEMI trial. Int J Cardiol 2016;202:894–6. 10.1016/j.ijcard.2015.10.063 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ouweneel DM, Eriksen E, Seyfarth M, et al. Percutaneous mechanical circulatory support versus intra-aortic balloon pump for treating cardiogenic shock: meta-analysis. J Am Coll Cardiol 2017;69:358–60. 10.1016/j.jacc.2016.10.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Seyfarth M, Sibbing D, Bauer I, et al. A randomized clinical trial to evaluate the safety and efficacy of a percutaneous left ventricular assist device versus intra-aortic balloon pumping for treatment of cardiogenic shock caused by myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol 2008;52:1584–8. 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.05.065 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Elm Evon, Altman DG, Egger M, et al. Strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. BMJ 2007;335:806–8. 10.1136/bmj.39335.541782.AD [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Henriques JPS, Remmelink M, Baan J, et al. Safety and feasibility of elective high-risk percutaneous coronary intervention procedures with left ventricular support of the Impella recover Lp 2.5. Am J Cardiol 2006;97:990–2. 10.1016/j.amjcard.2005.10.037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Steg PG, James SK, Atar D, et al. ESC guidelines for the management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with ST-segment elevation. Eur Heart J 2012;33:2569–619. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehs215 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Roffi M, Patrono C, Collet J-P, et al. 2015 ESC guidelines for the management of acute coronary syndromes in patients presenting without persistent ST-segment elevation: Task Force for the management of acute coronary syndromes in patients presenting without persistent ST-segment elevation of the European Society of cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J 2016;37:267–315. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehv320 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Pöss J, Köster J, Fuernau G, et al. Risk stratification for patients in Cardiogenic shock after acute Myocardial Infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol 2017;69:1913–20. 10.1016/j.jacc.2017.02.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Pappalardo F, Schulte C, Pieri M, et al. Concomitant implantation of Impella® on top of veno-arterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation may improve survival of patients with cardiogenic shock. Eur J Heart Fail 2017;19:404–12. 10.1002/ejhf.668 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Mehran R, Rao SV, Bhatt DL, et al. Standardized bleeding definitions for cardiovascular clinical trials: a consensus report from the bleeding academic research Consortium. Circulation 2011;123:2736–47. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.009449 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Zeymer U, Thiele H. Mechanical support for cardiogenic shock: lost in translation? J Am Coll Cardiol 2017;69:288–90. 10.1016/j.jacc.2016.10.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. O'Neill WW, Kleiman NS, Moses J, et al. A prospective, randomized clinical trial of hemodynamic support with Impella 2.5 versus intra-aortic balloon pump in patients undergoing high-risk percutaneous coronary intervention: the ProtecT II study. Circulation 2012;126:1717–27. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.112.098194 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Thiele H, Jobs A, Ouweneel DM, et al. Percutaneous short-term active mechanical support devices in cardiogenic shock: a systematic review and collaborative meta-analysis of randomized trials. Eur Heart J 2017;38:3523–31. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehx363 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Schrage B, Ibrahim K, Loehn T, et al. Impella support for acute myocardial infarction complicated by cardiogenic shock. Circulation 2019;139:1249–58. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.118.036614 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Basir MB, Schreiber T, Dixon S, et al. Feasibility of early mechanical circulatory support in acute myocardial infarction complicated by cardiogenic shock: the Detroit cardiogenic shock initiative. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv 2018;91:454–61. 10.1002/ccd.27427 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

openhrt-2018-000987supp001.pdf (222.4KB, pdf)