Abstract

Infectious diseases have been a preeminent part of literature since the earliest human writings. In particular, they have contributed greatly to the genre of horror—written or visual art intended to startle or scare. Horror fiction has emphasized infectious themes from the earliest Babylonian and Hebrew texts. In medieval times, stories of vampires and werewolves often had a contagious component, and pivotal works of Victorian horror centered around fear of infection and contamination. As film became prominent in the 20th Century, a strong emphasis on themes of plague and apocalypse developed. An analysis of the use of infection in horror fiction and film shows that it often represents a metaphor for societal concerns, and it is extremely useful in framing challenging issues for a wide audience.

Keywords: Bubonic Plague, History of medicine, Infectious diseases, Syphilis

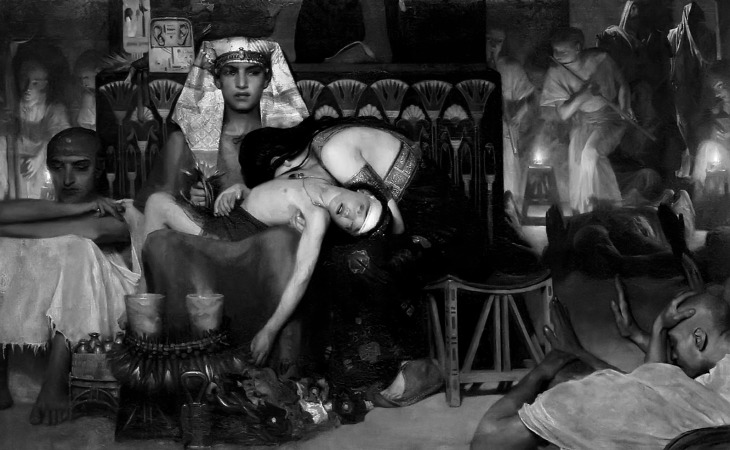

The origins of horror as an art form, which intends to startle or scare its audience, go as far back as recorded history. Approximately 4 millennia ago the Babylonian epics Gilgamesh and Enuma Elish told of frightening demons, among them “the Hydra, the Dragon, the Hairy Hero, the Great Demon, the Savage Dog, the Scorpion-man…the Fishman, and the Bull-man.”1,2 The Book of Exodus (likely composed about 2,700 years ago) related the 10 plagues of Egypt, four of which clearly involved an infectious epidemic or infestation (lice, flies, livestock disease, boils), and the last and most powerful plague was a horrible affliction that smote older offspring “from the firstborn of Pharaoh that sitteth upon his throne…[to] all the firstborn of beasts”3 (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Death of the Pharaoh’s Firstborn Son (1872), by Lourens Alma Tadema, depicts the Egyptian ruler mourning his son who died of the 10th plague of Egypt. [Public domain courtesy of the Rijksmuseum, The Netherlands; http://hdl.handle.net/10934/RM0001.COLLECT.5773]

Though the exact nature of the final biblical plague remains obscure, one can easily imagine an epidemic of influenza, Streptococcus A, or cholera raging through the community and striking the robust scions of the Egyptian overlords. One scientific explanation for the plague striking Egyptians but sparing the Israelites could be the elaborate Egyptian funerary practices, an echo of the recent Ebola outbreaks in West Africa in which the corpse handlers were at great risk for contracting the highly contagious and fatal infection.4

As human societies moved forward from the Bronze Age, the stories of frightening beasts and beings became a reflection of the periodic wars and plagues that afflicted the populations. The emerging cultures of medieval Europe continued the horror tradition with stories of witches, vampires and werewolves, often with an infectious element to the mythology. Horror fiction as a distinct literary genre might be said to begin in the early 1800s with Grimm’s Fairy Tales (1812), Mary W. Shelley’s Frankenstein (1818), and John Polidori’s The Vampyre (1819)—the latter two composed simultaneously during the famous retreat at Lord Byron’s cottage in the English countryside. These works emphasized the themes of death and decay prominent in The Industrial Age, and presaged an increasing focus on contagion as the 19th Century moved toward the late Victorian era. In 1897, concerns over health and political crises bubbled over in an iconic novel that set the stage for a new era of horror fiction and, soon thereafter, horror movies, which would prove fertile ground indeed for infectious themes.

Vampires and Werewolves: Infectious Bites and Rabid Transformations

When they become such, there comes with the change the curse of immortality; they cannot die, but must go on age after age adding new victims and multiplying the evils of the world. For all that die from the preying of the Un-dead become themselves Un-dead, and prey on their kind. And so the circle goes on ever widening, like as the ripples from a stone thrown in the water.5

It took quite a bit of cumbersome exposition, but eventually Bram Stoker’s 1987 novel Dracula got down to the nub of the issue: a bite from a malignant host transformed a poor victim into a horrible creature, catatonic during the day but ravenous at night for a blood meal. Thus, this highly influential story echoed older myths of contamination and transformation, while creating a template for the modern monster story.

Vampire myths are among the oldest monster stories extant, finding origins in ancient Persian and Babylonian stories of blood-sucking demons and biblical references to Lilith, the “night creature.” 6,7 The myth of the succubus—a demonic female figure notorious for killing children and seducing men and drinking their blood—was echoed in Greek and Roman literature and was later expanded during medieval times. Repeated sex with a succubus was reputed to lead to illness and death.

While Bram Stoker was not the first modern writer to be inspired by such—Goethe had penned a poem about an undead vampiric lover almost 100 years earlier (“The Bride of Corinth”), and Polidori published his successful novel, The Vampyre, in 1819—Stoker’s 1897 Dracula caught the zeitgeist and was certainly the most influential. Dracula described a young woman with a mysterious illness linked to contact with a vampire:

Another bad night….There was a sort of scratching or flapping at the window, but I did not mind it, and as I remember no more, I suppose I must have fallen asleep.… This morning I am horribly weak. My face is ghastly pale, and my throat pains me. It must be something wrong with my lungs, for I don’t seem to be getting air enough.8

The shape-shifting nature of the vampire allowed it to assume the form of a bat or a wolf, mammals well known to carry the lethal disease rabies. Many of the “symptoms” of vampirism suggested a severe encephalopathic infection like rabies: light sensitivity, heightened senses, unusual food and drink cravings, fatigue, headaches and altered sensorium. However, another infectious entity may be more relevant to Stoker’s vampire tale. The sexual aspects of Dracula are fairly obvious and have long been a subject of discussion.9 Was vampirism a sexually transmitted illness?

In the late 1800s, syphilis was seen as a European health crisis of the first order. Having made its appearance in the late 1400s, presumably as a result of contact between Columbus’ sailors and Caribbean indigenous people, the disease smoldered and spread throughout Europe.10 The high prevalence of syphilis in population centers, together with its known association with sexual activity and the existence of a congenital form, led to fervid speculation that the civilizations of Western Europe would wither in the face of disease. Concomitant with the syphilis anxiety was the invasion panic of the late 1800s. The Franco-Prussian War in 1870 highlighted the vulnerability of the western countries to attack from the East and, by the later 1800s, a groundswell of so-called invasion literature depicted the collapse of European societies due to alien forces. Bram Stoker, an enterprising theater manager with a literary bent, deftly used the folklore of Eastern Europe to reflect the concerns of cultural decay due to the twin scourges of rampaging syphilis and invading hordes from the East. Incidentally, Stoker suffered several strokes prior to his death in 1912, with the official cause of death being “locomotor ataxy,” leading some writers to speculate (without authority) that he succumbed to complications of syphilis.11

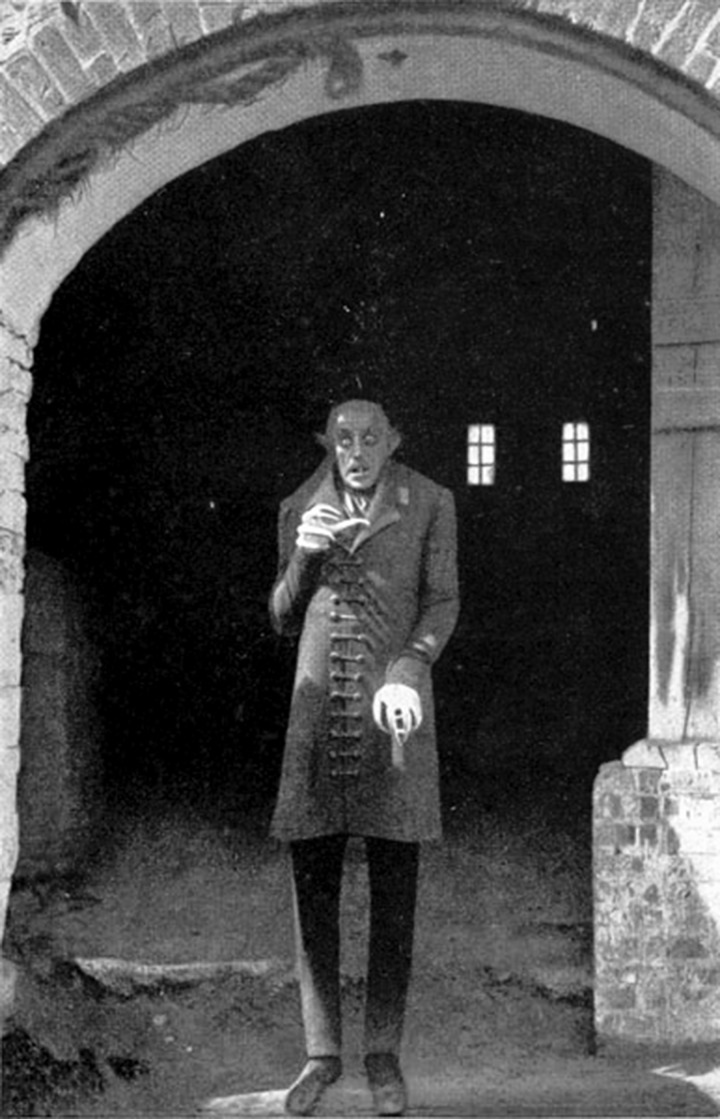

In the first faithful film adaptation of Dracula, F.W. Murnau’s Nosferatu (1922) presented Count Orlok (portrayed unforgettably by actor Max Schreck) as a striking figure, with a high bald forehead, pale complexion, misshapen and pointed ears, and deformed teeth. The resemblance to a victim of congenital syphilis cannot be ignored: “The face may include in varying degree frontal bossing, the photophobic habitus, wide-spacing of the orbits, corneal scarring, the impression of fatigue or unalertness in the eyes, ‘saddle-nose’ with flaring of the nostrils, and rhagades”12 (Figure 2). Later film adaptations, including the Bela Lugosi characterization in 1931, have tended to emphasize the seductive nature of the count rather than his grotesque appearance, but the infectious aspects of the vampire’s bite remained as cogent as ever.

Figure 2.

Max Schreck as the cadaverous Count Orlok in F.W. Murnau’s Nosferatu: A Symphony of Terror (1922) [Public domain-US-no notice; https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?curid=14388881].

Some of the more recent vampire offerings have suggested variations on the themes of contagion and control central to Dracula. The popular Guillermo del Toro TV series The Strain featured a race of vampires who infected susceptible victims and transformed them, while controlling their behavior through telepathy. The True Blood TV series and Twilight movies focused on the relationships between the subculture of infected vampires and their uninfected counterparts. The analogy to a blood- and fluid-borne pathogen like HIV could not be more apt, and many commentators have noted a correspondence between “the vampire craze” and the evolution of HIV/AIDS as a cultural phenomenon.13

The second of the big three monsters to come out of Universal Studios in the 1930s and 1940s, the Wolfman also represented old folkloric ideas that were particularly strong in the Balkans (Frankenstein reflected newer anxieties about the technological advances of the early Industrial Age). Like vampirism, lycanthropy, or the capability of transforming into a wolf and vice versa, has a world-wide and ancient history. In contrast, though, this condition was often depicted as the consequence of a spell, not a bite or sexual exposure, and in some cultures was considered a special gift, not a curse.

However, more recent versions do make the infectious component explicit. The 1933 book The Werewolf of Paris by Guy Endore and the 1935 movie Werewolf of London took such an approach and foretold the more famous Lon Chaney depiction in 1941’s The Wolfman. As with vampirism, the bite of a werewolf doomed the poor victim to an unwanted and painful physical transformation, as well as a lust for human flesh and blood. Rabies was also an obvious inspiration for the primitive and violent urges of this condition. A variation on the werewolf tradition was offered by the character Remus Lupin of the Harry Potter books and movies; lycanthropy in this series highlighted many contagious aspects that are also found with vampirism, including sexual and blood-borne transmission and vertical transmission through childbirth.

More Contagious Horrors: Parasites, Zombies and Pandemics

While vampires and werewolves represent external threats that frighten us with their long fangs and claws, some creatures are scary because they hide within our bodies. Parasitism is a theme that has been thoroughly explored in horror fiction and in movies. Robert Heinlein’s 1951 book The Puppet Masters (brought to film in 1994) examined the consequences of an extraterrestrial invasion by slug-like creatures that attach to humans and control their thoughts and actions. This setup was echoed in the 1955 Jack Finney book and 1956 movie Invasion of the Body Snatchers, as alien life forms arrive on earth as spores and parasitize humans, creating duplicate “pod people” lacking the emotive traits of their human models. It is not too far-fetched to find analogy with animal and human infestations with Toxoplasma gondii, given reasoned speculation that toxoplasmosis may affect brain function and behavior.14

Other creatures were more violent in their attacks. The 1959 William Castle movie The Tingler, starring Vincent Price, posited an interesting and unique monster, a kind of repressed parasitic centipede, which was mostly dormant, but fed on the host’s fear and became apparent only during intense moments of terror. The 1970s saw several movies focused on the theme of infestation, including David Cronenberg’s Shivers (1975) and Rabid (1977). The former centered on an unconventional researcher who bred a parasitic organism that invaded and caused uncontrollable sexual desire in the host before erupting from the host’s body with a fatal conclusion (a frightful scene later echoed by Alien). Rabid stretched the premise of rabies with an interesting amalgam of infectious illness and body dysmorphism (in particular a kind of vagina dentata in the axillary area). The rabid host seduced her victims and killed them with her terminal bite.

Of course, the Alien (1979) movie, its sequels, and its prequel Prometheus (2012) presented one of the most memorable modern examples of parasitic terror: an immature alien “xenomorph” which would infect the body of a human host, grow, and eventually burst out of the body (gruesomely) to transform into a ravenous adult. Similarities with actual human parasitoses, such as myiasis and dracunculosis, are readily apparent.

Then there are the pandemics of known or unknown cause. Richard Matheson’s 1954 book The Last Man on Earth and the subsequent 1964 movie starring Vincent Price described a worldwide pandemic that has turned most of humankind into vampiric beings, violent and phobic of sunlight. Price’s character developed immunity (ironically from the bite of a vampire bat) and, in an interesting turn of events, used his own blood as a kind of immunotherapy to cure a woman with an early form of the disease. This may have been the first popular depiction of zombies as victims of a plague rather than the spell of a witch or voodoo practitioner. More, though, would follow including several remakes based on Matheson’s book: 1971’s Omega Man and 2007’s I Am Legend.

The most famous zombie depiction of all time, George Romero’s 1968 classic Night of the Living Dead, posited zombification by exposure to government nuclear toxins. However, the contagious aspect was preeminent, as a deep bite from an afflicted zombie ensured a painful death and transformation to the zombie state (Figure 3). Later zombie movies, and especially the extremely popular cable series The Walking Dead, spelled out a “zombie apocalypse” arising from biological experiments gone awry. Any congruence between zombie outbreaks and a worldwide viral pandemic such as influenza or severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) is more than coincidental.15

Figure 3.

A still scene from George Romero’s Night of the Living Dead (1968) [Public domain-no notice; http://mentalfloss.com/article/91635/10-facts-about-night-living-dead].

The microbial aspect becomes explicit in the fertile branch of horror depicting highly fatal world-wide pandemics. Of course, great works of both non-fiction and fiction, as well as landmarks in the visual arts, have come out of the tragedies of pandemics like the Black Death of the 1300s, including Boccaccio’s Decameron and Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales, not to mention the works of Hieronymus Bosch and Pieter Bruegel the Elder. Mary Shelley, the author of Frankenstein, also penned a long-obscure novel in 1826 about the decimating effects of an imaginary plague that wiped out most human life.

One of the most influential modern works in this realm was Edgar Allen Poe’s 1842 tale The Masque of the Red Death:

The “Red Death” had long devastated the country. No pestilence had ever been so fatal, or so hideous. Blood was its Avatar and its seal the redness and the horror of blood….The scarlet stains upon the body and especially upon the face of the victim, were the pest ban which shut him out from the aid and from the sympathy of his fellow men…And Darkness and Decay and the Red Death held illimitable dominion over all.16

While the Red Death is often assumed to be a classic yersineal plague, Poe’s wife and several close relatives had died of tuberculosis, and he had witnessed close up the effects of a cholera epidemic on Baltimore, so the actual identity of the fatal affliction remains a subject for debate (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Illustration from The Masque of the Red Death by Harry Clarke, in E.A. Poe’s Tales of Mystery and Imagination (1919) [Public domain, Image courtesy of the British Library, London, UK].

Book and movie depictions of killer pathogens prior to the 1970s tended to feature the pestilence as a backdrop or a catalyst, not a focal point. For instance, Ingmar Bergman’s The Seventh Seal (1957) concerned issues of humanity and mortality during the time of the Black Death, highlighted notably by the famous scene of Max von Sydow’s knight playing chess with Death. John Sturges’ 1965 film The Satan Bug was one of the first depictions of a modern plague, and it modernized the theme with an errant virus stolen from “a top-secret government laboratory,” though the viral pathogen ends up being merely a plot device catalyzing a conventional thriller.

Much more preeminent was the 1969 Michael Crichton book and 1971 movie The Andromeda Strain (directed by Robert Wise). This classic outlined the aftereffects of an alien pathogen picked up by a satellite as it returns to earth. The plot also mixed in biowarfare experiments and the threat of a nuclear explosion, salient concerns of the time. Most compelling perhaps were the scenes of scientists and physicians donning bioprotective equipment that would not look out of place in hospitals treating the recent SARS and Ebola outbreaks. This set the mold for many of the compelling books and movies that followed, especially the recent profusion of movies focused on worldwide pandemics. A small selection of such movies includes Twelve Monkeys (1995), Outbreak (1995), Mimic (1997), and Contagion (2011). The latter echoed the SARS epidemic of 2003 and was widely praised for its scientific accuracy.17

Infectious Horror as Metaphor

Although the way in which disease mystifies is set against a backdrop of new expectations, the disease itself (once TB, cancer today) arouses thoroughly old-fashioned kinds of dread. Any disease that is treated as a mystery and acutely enough feared will be felt to be morally, if not literally, contagious.18

AIDS has a dual metaphoric genealogy. As a microprocess, it is described as cancer is: an invasion. When the focus is transmission of the disease, an older metaphor, reminiscent of syphilis, is invoked: pollution.19

Why we like horror in fiction and film has been much debated over the years. Sigmund Freud, for instance, saw horror as an expression of the primitive id, suppressed by the ego. Carl Jung, on the other hand, pointed to universally shared motifs such as the persona and shadow archetypes that informed the horror genre.20 Our desire to watch horror as it plays out in fictional settings, therefore, likely comes from primal psychological needs to control chaos and overcome fears.

Thus, it should not be surprising that virtually all depictions of horror have had great symbolic significance, from the Egyptian plague of the firstborn, to the great Gothic novels, and on to the Universal monster movies and modern films like War of the Worlds and Contagion. They show order breaking down due to forces (at least initially) beyond human control. The tension and even enjoyment of reading or watching arises from the vicarious experience of the human struggle to manage the disorder. The infectious motif thus becomes a critical element in understanding the significance of horror in human societies, as horrible acts, whether natural or manmade, produce a kind of cultural sickness that must be isolated, analyzed, and disarmed.

On a close up level, this is obvious when the threat is a monster, a deviant creature that threatens the local community and needs to be contained and (preferably) destroyed. The monster exists in a liminal state—human-like, yet unclean, reminiscent of the lepers in the Bible. By extension, monsters on a grand scale, either an invading alien army or invading microorganisms, also produce contamination and transformation, and require isolation and treatment.

Yet, there are even more layers of meaning. Given that horror reflects the age in which it was created, it serves as a metaphorical tool for writers and artists to come to terms with dark forces and cataclysmic events. The Bronze Age epics of demons and angels, the medieval witches and beasts, and the 19th Century stories of reanimated corpses and Balkan vampires made tangible the anxieties of those eras. By the latter time in particular, there was a realization that cultural change was accelerating, whether by industrialization, external pressure from potential Eastern invaders, or internal pressure from “hidden epidemics” like syphilis.

Finally, in the 20th Century while our knowledge of such threats has become more informed, our means to deal with them has barely kept pace. The horrors of two world wars followed by the first nuclear cataclysms have led to a realization that untoward events could triumph over technology and civilization. In fact, science and culture could contribute to mankind’s decay. This is the critical point that horror, and especially infectious horror in the post-World War II period, address. Men and women of science, in their hubris, have created the conditions for monstrous outbreaks (Night of the Living Dead, The Andromeda Strain), or at the least have underestimated an alien threat until it was widespread and almost unstoppable (Invasion of the Body Snatchers). The threat has progressed despite the frequent Cassandras who sound warnings about the crisis—for instance, Drs. Stone and Hall in The Andromeda Strain, Dr. Miles Bennell in Invasion of the Body Snatchers, and Col. Sam Daniels (played by Dustin Hoffman) in Outbreak. The systems for control have proven inadequate to the challenges of the modern era—a pivotal anxiety that shadows our time.

Horror seems likely to continue to make up a fertile portion of our literature and visual art, and infectious elements will almost certainly be prominent. One can hope that confronting our contagious fears in fiction will allow us to manage them better in real life.

References

- 1.Epic of Gilgamesh (translation by Georg Burckhardt). Available at https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Humbaba.

- 2.Enuma Elish: The Babylonian Epic of Creation. 2018. Available at: https://www.ancient.eu/article/225/enuma-elish---the-babylonian-epic-of-creation---fu/.

- 3.Exodus 11:4–6. The Bible. King James Version. Available at: https://www.biblegateway.com/passage/?search=Exodus+11&version=KJV.

- 4.Maxmen A. How the fight against Ebola tested a culture’s traditions. National Geographic; January2015. Available at: https://news.nationalgeographic.com/2015/01/150130-ebolavirus-outbreak-epidemic-sierra-leone-funerals/.

- 5.Stoker B. Dracula. New York: Doubleday; 1897. 200. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Marigny J. Vampires: Restless creatures of the night. New York: Abrams; 1993. 14–19. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Isaiah 34:14. The Tanakh. Jewish Publication Society. 1917 version; Available at https://www.mechon-mamre.org/p/pt/pt1034.htm. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stoker B. Dracula. New York: Doubleday; 1897. 103. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Miller E. Coitus Interruptus: Sex, Bram Stoker, and Dracula. Romanticism on the Net: The Gothic, from Ann Radcliffe to Anne Rice, Number 44, November2006. Available at: https://www.erudit.org/en/journals/ron/2006-n44-ron1433/014002ar/.

- 10.Quetel C. History of syphilis. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins; 1992. 33–130. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Belford B. Bram Stoker: A biography of the author of Dracula. New York: Alfred Knopf; 1996. 320–321. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Laird S. Late congenital syphilis: An analysis of 115 cases. Br J Vener Dis. 1950;26:143–145.. Available at: http://pubmedcentralcanada.ca/pmcc/articles/PMC1053700/pdf/brjvendis00169-0035.pdf. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bannigan J. Gift chasers: Reading HIV/AIDS in Twilight Saga: Breaking Dawn, Part 1. Pop Culture Uncovered. 2014. Available at: https://popcultureuncovered.com/2014/09/26/gift-chasers-reading-hivaids-in-twilight-saga-breaking-dawn-part-1/.

- 14.Mcauliffe K. How Your Cat Is Making You Crazy. The Atlantic, March2012. Available at: http://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2012/03/how-your-cat-is-making-you-crazy/308873/. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gupta S. The big one is coming, and it’s going to be a flu pandemic. CNN. 2018. Available at: https://www.cnn.com/2017/04/07/health/flu-pandemic-sanjay-gupta/index.html. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Poe E. The masque of the Red Death. 1842. Available at: http://xroads.virginia.edu/~hyper/poe/masque.html.

- 17.Offit P. Contagion, the movie: An expert medical review. Medscape. Available at: https://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/749482.

- 18.Sontag S. Illness as metaphor. New York: Farrar, Straus & Giroux; 1978. 6. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sontag S. AIDS as metaphor. New York: Farrar, Straus & Giroux; 1989. 19. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Iaccino J. Psychological reflections on cinematic terror: Jungian archetypes in horror films. Westport, CT: Praeger; 1994. 3–8. [Google Scholar]