Abstract

Context

There is a 4- to 5-year variation in age of breast maturation in girls.

Objective

To examine longitudinal changes in sex hormone values relative to chronologic age and time relative to breast maturation.

Setting and Design

Longitudinal observational study into which girls were recruited at 6 to 7 years of age and followed up every 6 months.

Main Outcome Measures

Maturation status, chronologic age, race, and fasting blood specimen data were obtained. Hormones were analyzed at 6-month intervals between 2 years before and 1 year after breast maturation, using HPLC tandem mass spectroscopy.

Results

Estradiol and estrone levels correlated with chronologic age (R = 0.350 and 0.444, respectively); time was correlated relative to breast maturation (R = 0.222 and 0.323, respectively; all correlations, P < 0.0001). In generalized estimating equation (GEE) models, chronologic age and time relative to pubertal onset were significantly associated with serum estradiol, with similar results for estrone. Local estimated scatterplot smoothing for estradiol and estrone, by chronologic age, demonstrated differences between black and white girls, especially between 8.5 and 11 years of age, but not by race in time relative to breast maturation. Testosterone level was correlated to chronologic age (R = 0.362) and time relative to breast maturation (R = 0.259); in the GEE model, only chronologic age was significant.

Conclusion

Chronologic age as well as time relative to onset of puberty provided unique information regarding estradiol and estrone concentrations in peripubertal girls. Serum estrogen concentrations should be evaluated with reference to chronologic age and race.

Sex steroid levels were followed longitudinally in a group of peripubertal girls. Age and puberty made unique contributions to estrogen levels.

Sex steroids change dramatically in puberty; there is an increase in sex steroid levels before the development of secondary sexual characteristics in girls (1). Hormonal changes reported in the peripubertal period have often been evaluated using cross-sectional, rather than longitudinal, data (2) and less-sensitive analytical methods, such as RIA (3). Most studies have provided data linked to chronologic age despite a wide range in relative timing of pubertal onset: There is a 5-year difference between the fifth and 95th percentiles in age at onset of breast stage 2 (4).

Our goal for this study was to examine longitudinal hormone values and compare the contributions of chronologic age and time relative to onset of breast maturation and sex hormone changes in a group of black peripubertal girls and white peripubertal girls.

Methods

The subjects for these analyses were participants at the Cincinnati site of the Breast Cancer and the Environment Research Centers. Study aims and design of the overall project have been reported in detail (5). Briefly, the majority of Cincinnati participants were recruited through public and parochial schools in the greater Cincinnati metropolitan area. Participants were recruited between ages 6 and 7 years and seen every 6 months between 2004 and 2010, with a visit window of ±4 weeks. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center. Informed consent was obtained from parents and/or guardians.

Trained and certified female staff members performed standardized anthropometric measurements, with two or more height and weight measurements, as detailed previously (5). In addition, several female advanced practice nurses and physicians were trained and certified in assessment of pubertal maturation, using the criteria established by Marshall and Tanner (6) for breast maturation (with palpation) and pubic hair stages. Double assessment with a master trainer resulted in 87% perfect agreement [κ = 0.68, indicating substantial agreement (5)].

Early-morning fasting blood specimens were collected at every visit. Serum was frozen at −80°C and later analyzed for selected hormones at the onset of breast development and at each of four preceding visits (up to 24 months before breast development), and up to 12 months after breast development. Serum samples obtained at those clinical visits were chosen to measure the following four sex steroids: dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate (DHEA-S), estrone, estradiol, and testosterone.

For most specimens, DHEA-S was measured by RIA using a rabbit antibody made against a DHEA-7-BSA antigen. Each assay batch contained a complete standard curve and three levels of quality-control samples. The last 104 specimens for DHEA-S were measured by HPLC with tandem mass spectrometry (HPLC-MS). The correlation between the two approaches (RIA and HPLC-MS) for DHEA-S was 0.948 throughout the range of values in this study.

All specimens were measured by HPLC-MS for levels of estradiol, estrone, and testosterone. Each steroid was first extracted with hexane–ethyl acetate; the extract was dried and reconstituted in solvent compatible with the HPLC-MS. Each assay batch for all hormones contained duplicate standard sets of eight or more serum-based standards and duplicate sets of three to five serum quality-control samples. Assay performance was demonstrated during validation analyses. The lower limits of quantitation were defined as the level at which a coefficient of variation was <20% (25% for RIA). The lower limits of quantitation levels were as follows: DHEA-S, 10 μg/dL; estrone, 2.5 pg/mL; estradiol, 1 pg/mL; and testosterone, 3 ng/dL. Because of the volume of serum necessary to run the estrone and estradiol assays and limited availability of specimen, the serum was diluted 1:1 with water, resulting in a limit of detection twice as great as noted in the previous sentence.

Interassay precision values, expressed as percent coefficient of variation for low, medium, and high control serum samples, were 6.5%, 8.4%, and 7.3% for DHEA-S; 4.9%, 4.6%, and 4.7% for estrone; 4.4%, 3.5%, and 3.3% for estradiol; and 9.9%, 7.9%, and 5.0% for testosterone. Midrange control coefficients of variation were 4.6% for estrone, 3.5% for estradiol; and 4.3% for testosterone.

Statistical analyses

The initial analyses examined the distributions of hormone concentrations using histogram plots and Kolmogorov-Smirnov (goodness-of-fit) tests. Log transformation was applied to each of the hormones because the Kolmogorov-Smirnov tests demonstrated better fit with log-normal transformation. There were varying numbers of missing values for different hormone assays, typically due to insufficient volume; missing hormone data were assumed to be randomly distributed.

Mixed modeling was applied to the log-transformed hormone values to better understand the profile of hormone changes around the time of breast development. The mixed-model analyses simultaneously considered hormone concentrations at onset of breast development, as well as the serum concentrations at 6-month intervals before and after time of breast development. The hormone concentrations at times relative to breast development were the main factor, and corresponding least square means were estimated and presented in the figures. The least square means were adjusted for laboratory batch effect and body mass index (BMI) Z-score at onset of breast development (by quartile). BMI Z-score was determined from the 2000 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention growth charts (7). The probability values noted in Results and in the figures are based on the least square means at different relative times, contrasted between adjacent 6-month intervals, to define the earliest significant increase in concentration for a given hormone. Multiple comparisons were adjusted using the Hochberg step-down procedure.

Locally estimated scatterplot smoothing (LOESS) analyses were performed to generate the figures for race-specific hormone concentrations by age. LOESS is a local, weighted smoothing technique designed to reveal a nonlinear relationship between the independent and dependent variables. The LOESS analyses used a smoothing parameter of 0.3; that is, it used 30% of all data closest to the local point, local linear regression. No other covariates were considered in the LOESS analyses. The results are presented by the calculated value and 95% interval estimate at the given age points.

Generalized estimating equation (GEE) analyses examined the associations between serum hormone concentrations relative to chronologic age and time relative to onset of puberty over repeated serum samples, including their interaction term. GEE is a semiparametric model related to generalized linear modeling. Missing data were treated as missing at random. All analyses, including LOESS and GEE, were conducted using SAS, version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Results

The average age of participants at the time of the first visit was 7.09 years. Race and ethnicity were defined by the parents or legal guardian; 32.5% of participants were black, 4.4% were Hispanic, 61.9% were white non-Hispanic, and were 0.4% Asian. The average age at onset of puberty (breast stage 2) was 8.78 years. These analyses include only black and white non-Hispanic participants, because the other groups provided limited numbers for analyses. There were 1071 serum samples generated by 248 participants for estradiol analysis before and after breast development: 57 samples were analyzed at 24 months before, 147 samples were analyzed 18 months before, 170 samples at 12 months before, 203 samples at 6 months before, 193 samples at breast development, 215 samples at 6 months after, and 86 samples at 12 months after. There were, overall, 10 fewer samples analyzed for testosterone (due to insufficient quantity of available serum).

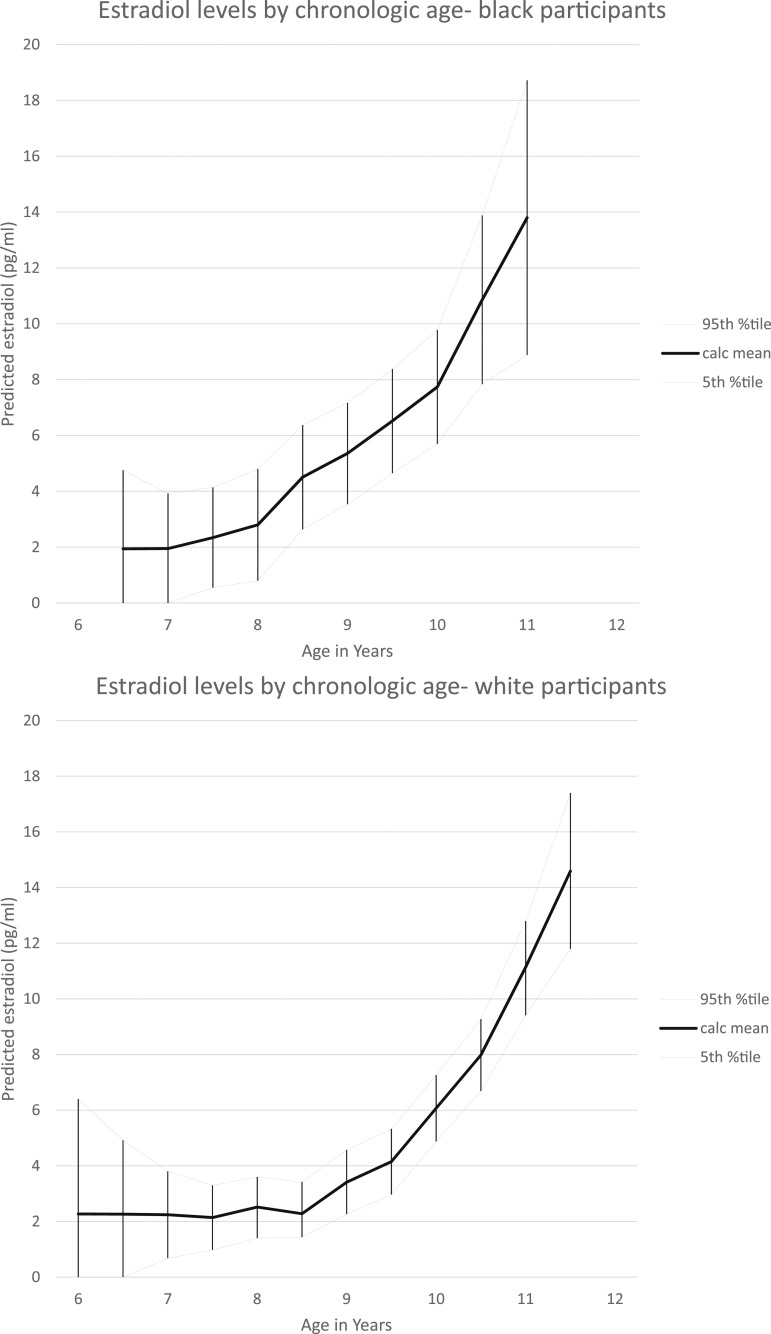

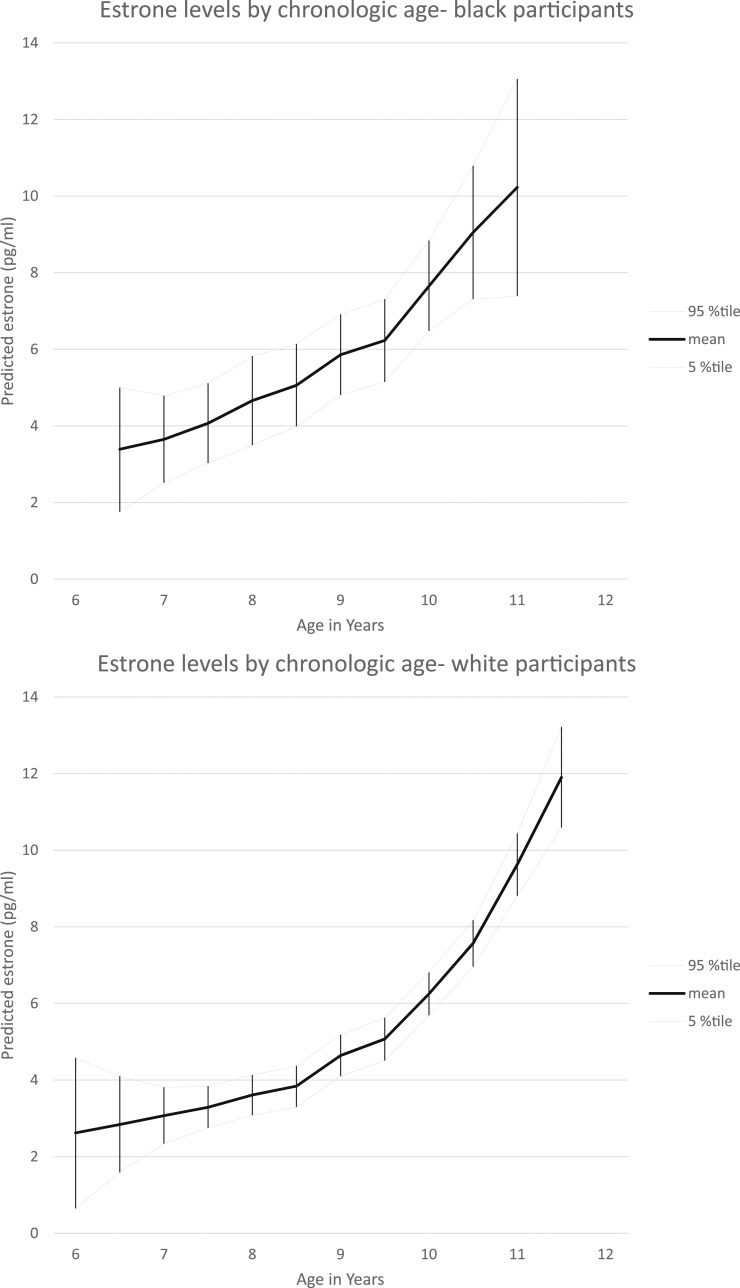

Mean and median values of estradiol and estrone by chronologic age and by time relative to onset of puberty are reported in Tables 1 and 2. The Spearman correlation of estradiol concentration and chronologic age was 0.350 (P < 0.0001) and for estradiol and time relative to breast maturation was 0.222 (P < 0.0001). The Spearman correlation of estrone concentration and chronologic age was 0.444 (P < 0.0001) and for estrone and time relative to breast maturation was 0.323 (P < 0.0001). Mean values for estradiol and estrone concentrations using a LOESS model, by age and race, are shown in Figs. 1 and 2. Of note, there were no significant differences by race when examining estradiol and estrone concentrations relative to onset of puberty (1).

Table 1.

Predicted Estradiol and Estrone Concentrations Relative to Chronologic Age; Modeled From LOESS Analysis

| Chronologic Age, y | Predicted Estradiol Concentration, pg/mL | 95% CI | Predicted Estrone Concentration, pg/mL | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6.0 | 2.00 | −1.70 to 5.70 | 2.89 | 1.09–4.68 |

| 6.5 | 2.08 | −0.17 to 4.33 | 3.12 | 2.02–4.21 |

| 7.0 | 2.16 | 0.77–3.55 | 3.34 | 2.67–4.02 |

| 7.5 | 2.18 | 1.07–3.29 | 3.57 | 3.03–4.11 |

| 8.0 | 2.73 | 1.59–3.87 | 3.99 | 3.44–4.55 |

| 8.5 | 2.99 | 1.89–4.09 | 4.23 | 3.69–4.76 |

| 9.0 | 3.94 | 2.81–5.07 | 5.07 | 4.52–5.61 |

| 9.5 | 5.21 | 4.11–6.33 | 5.66 | 5.12–6.20 |

| 10.0 | 6.96 | 5.83–8.08 | 6.80 | 6.26–7.35 |

| 10.5 | 8.32 | 7.01–9.63 | 7.91 | 7.27–8.54 |

| 11.0 | 11.20 | 9.32–13.1 | 9.65 | 8.74–10.5 |

| 11.5 | 14.16 | 11.1–17.2 | 11.52 | 10.1–13.0 |

Table 2.

Estradiol and Estrone Concentrations Relative to Onset of Breast Maturation

| Time Relative to Breast Maturation | Estradiol, pg/mL | Estrone, pg/mL | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | Median | Mean | Median | |

| −24 mo | 1.37 | 0.7 | 2.65 | 1.8 |

| −18 mo | 1.66 | 1.3 | 2.97 | 2.7 |

| −12 mo | 3.33 | 1.5 | 3.92 | 3.1 |

| −6 mo | 2.82 | 1.8 | 3.96 | 3.5 |

| 0 | 3.40 | 2.0 | 4.52 | 3.9 |

| +6 mo | 5.63 | 2.9 | 6.23 | 5.4 |

| +12 mo | 10.50 | 4.3 | 9.07 | 6.3 |

Figure 1.

Estradiol levels by chronologic age and race. LOESS analyses of race-specific estradiol concentrations by chronologic age are shown; a smoothing parameter of 0.3 was used in analyses. Mean values and 95th percentile confidence limits are provided. %tile, percentile; Calc, calculated.

Figure 2.

Estrone levels by chronologic age and race. LOESS analyses of race-specific estrone concentrations by chronologic age are shown; a smoothing parameter of 0.3 was used in analyses. Mean values and 95th percentile confidence limits are provided. %tile, percentile.

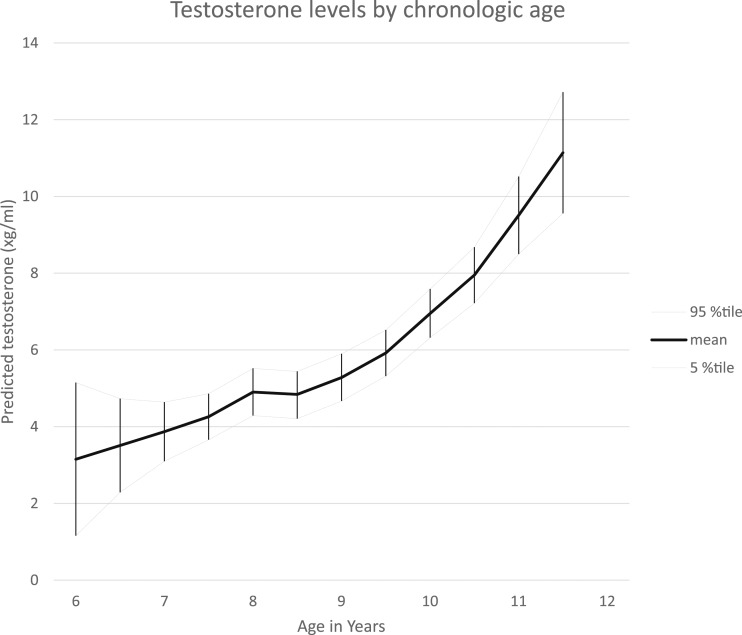

The Spearman correlation of testosterone concentration and chronologic age was 0.362 (P < 0.0001) and for testosterone and time relative to breast maturation was 0.259 (P < 0.0001). The concentrations by age were not significantly different by race. Mean values for testosterone concentrations using a LOESS model, by age, are shown in Fig. 3.

Figure 3.

Testosterone levels by chronologic age. LOESS analyses of testosterone concentrations by chronologic age are shown; a smoothing parameter of 0.3 was used in analyses. Mean values and 95th percentile confidence limits provided. %tile, percentile.

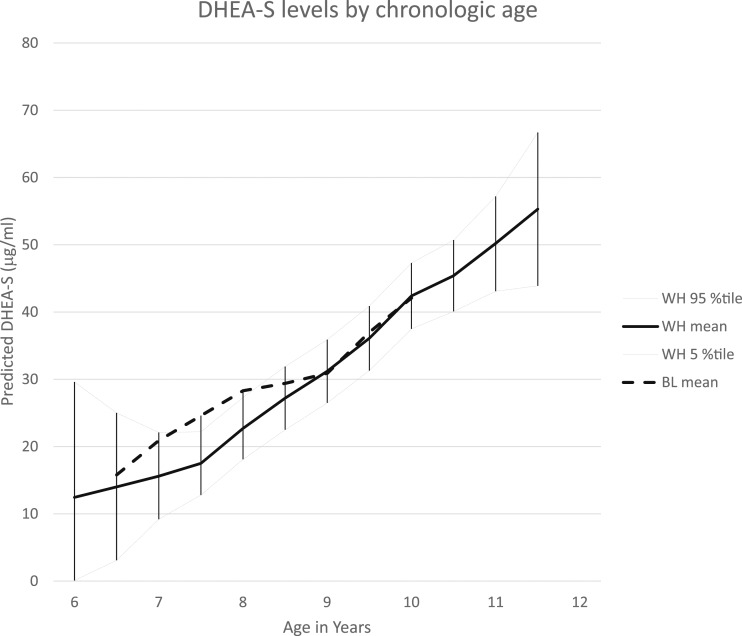

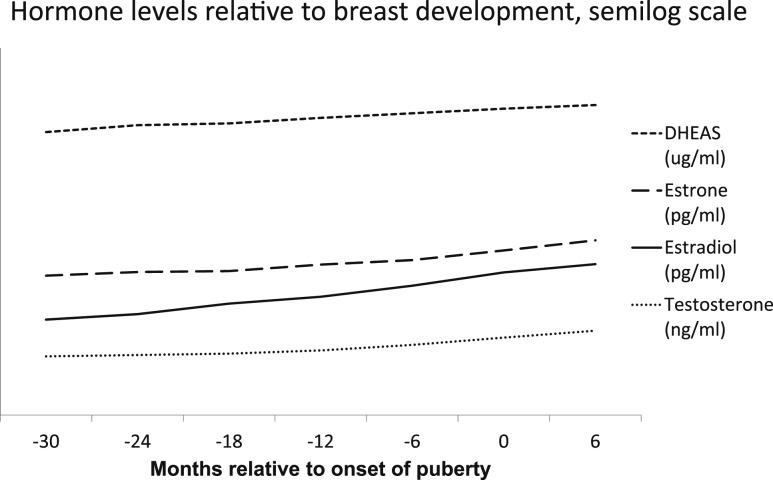

The Spearman correlation of DHEA-S concentration and chronologic age was 0.389 (P < 0.0001) and for DHEA-S and age relative to breast maturation was 0.209 (P < 0.0001). Mean values for DHEA-S concentrations using a LOESS model, by age, are shown in Fig. 4; because of a nonsignificant difference in values by race, the mean values of DHEA-S in black participants are included on the figure for white participants. Changes in levels of all four hormones relative to onset of breast development are shown in Fig. 5.

Figure 4.

DHEA-S levels by chronologic age and race. LOESS analyses of race-specific DHEA-S concentrations by chronologic age are shown; a smoothing parameter of 0.3 was used in analyses. Mean and 95th percentile confidence limits are provided for white participants; mean values are provided for black participants. %tile, percentile.

Figure 5.

Hormone levels relative to breast development. Hormone values are converted to a natural-log scale. DHEA-S concentrations are divided by 100, and testosterone concentrations are multiplied by 100.

GEE analyses were performed to examine relationships between concentrations of a selected hormone to both chronologic age and time relative to onset of puberty; a term was included examining the interaction of chronologic age and age relative to onset of puberty (Table 3). In the GEE model, chronologic age and time relative to pubertal onset, as well as the interaction, were significantly associated with serum estradiol over repeated serum samples (P < 0.0001, P = 0.002, and P = 0.0015, respectively). The model for estrone was nearly identical to that for estradiol, whereas only chronologic age met the criterion at P < 0.05 in the GEE model for serum testosterone (Table 3) (8).

Table 3.

GEE Model for Selected Hormone to Chronologic Age and Time Relative to Onset of Puberty

| Hormone | Chronologic Age, χ2 (df); P Value | Time Relative to Onset of Puberty, χ2 (df); P Value | Interaction Term for Chronologic Age and Time Relative to Onset of Puberty, χ2 (df); P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Estradiol | 15.19 (1); | 18.92 (5); | 19.51 (5); |

| < 0.0001 | 0.0020 | 0.0015 | |

| Estrone | 24.34 (1); | 18.03 (5); | 20.40 (5); |

| < 0.0001 | 0.0029 | 0.0010 | |

| Testosterone | 18.14 (1); | 9.91 (5); | 10.98 (5); |

| < 0.0001 | 0.078 | 0.052 |

Abbreviation: df, degrees of freedom.

Discussion

This longitudinal study of peripubertal girls examined the impact of chronologic age and maturation age on serum concentrations of selected sex hormones. Chronologic age and time relative to onset of puberty were significantly correlated with sex steroid concentrations in peripubertal girls. In addition, both time variables provided unique information that contributed to the hormone concentrations, particularly for the estrogens estradiol and estrone. These findings would suggest that the reference intervals for estrogens, especially in the peripubertal period, should be race specific, given the differences in timing of onset of puberty, with black girls maturing before white girls. This outcome is evident when examining specific ages; for example, mean values for estradiol in black participants between 8.5 and 11 years of age were greater than the 95% CIs for white participants at the same age (Fig. 1). In addition, evaluation of conditions that are potentially related to abnormalities in sex steroids, such as hyperandrogenism, mandate sensitive analytic approaches relevant to pubertal status (9).

Most studies that have investigated sex steroids in the peripubertal period have reported results by chronologic age despite differences in age of pubertal onset. Few studies of hormones have incorporated biologically relevant time variables. Several decades ago, Sizonenko and Paunier (10) and Ducharme et al. (11) noted that sex steroid values were related to bone age. Aksglaede et al. (12) noted that, when stratifying girls into prepubertal (breast stage 1) and pubertal (breast stage ≥2) status, pubertal girls had greater serum estradiol levels in all age intervals, although they were only significantly different between 10 and 12 years of age. As we reported previously (1), DHEA-S level increased before estrone and androstenedione level did (12 to 18 months before breast stage 2 maturation), followed by estradiol and testosterone levels (6 to 12 months before breast stage 2). In addition, estrogen concentrations in early puberty are influenced by BMI (1).

There are several potential limitations to the current study. The participants included in this analysis are from one metropolitan community and not nationally representative. However, the race and ethnicity of participants are representative of the greater Cincinnati area and include a broad socioeconomic diversity (5). The analytic technique for DHEA-S changed during the study period from RIA to HPLC-MS, but there was a high correlation between the two techniques at values determined for these analyses (R = 0.948). Pubertal maturation staging is not as precise as determination of chronologic age, which may explain, in part, the smaller correlation values when contrasting age and stage relative to sex steroid concentrations in the peripubertal period. As noted, the examiners received rigorous training and certification, with perfect agreement in 87% of examinations when contrasted with a master trainer 1 to 2 years later (5). Although the LOESS approach yields modeled data rather than raw data, it is a locally weighted polynomial regression technique that provides a weighted moving average. This approach does not require a predetermined function to fit all of the data in the sample and is less influenced by outliers. This approach yields clinically applicable information and provides the opportunity to examine the impact of multiple determinants on our outcome of interest, sex steroid concentration (13). In addition, we used HPLC-MS to analyze the serum specimens in a laboratory certified by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; the average bias estimations from proficiency studies in this laboratory is <2%.

This study provides longitudinal hormone data from peripubertal black and white girls, examined from chronologic age, as could be used in a clinical setting, as well as from time from onset of pubertal maturation. Both approaches provide unique contributions to serum concentrations of hormones. Several recent studies have documented the earlier onset of puberty in girls, and we reported that BMI, rather than race or ethnicity, had a greater impact on age at onset of breast development (4). However, the distribution of the age at thelarche has become extended and is associated with a longer duration of puberty (i.e., interval of thelarche to menarche) (14). These changes suggest the potential impact of environmental factors, most prominently the role of endocrine disruptors. Future studies examining the concentrations of hormones with exposure to endocrine disruptors may reveal the mechanism of the changes in age at onset of puberty.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the clerical assistance of Jan Clavey.

Financial Support: This work was supported by the Breast Cancer and the Environment Research Centers (Grants U01 ES/CA-12770 and ES-019453 to F.M.B.), which are funded by the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (NIEHS) and the National Cancer Institute (NCI); the National Institutes of Health [Grants ES-029133 to (F.M.B.) and 8 UL1 TR000077–05]; the US Public Health Service (Grant) UL1 RR026314; NIEHS Grant P30 ES006096 (to F.M.B.).

The contents of this report are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the NIEHS, NCI, or the National Institutes of Health.

Disclosure Summary: D.W.C. is employed by Endocrine Sciences. The other authors have nothing to disclose.

Glossary

Abbreviations:

- BMI

body mass index

- DHEA-S

dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate

- GEE

generalized estimating equation

- HPLC-MS

HPLC with tandem mass spectrometry

- LOESS

locally estimated scatterplot smoothing

References

- 1. Biro FM, Pinney SM, Huang B, Baker ER, Walt Chandler D, Dorn LD. Hormone changes in peripubertal girls. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2014;99(10):3829–3835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Singh GK, Balzer BW, Kelly PJ, Paxton K, Hawke CI, Handelsman DJ, Steinbeck KS. Urinary sex steroids and anthropometric markers of puberty—a novel approach to characterising within-person changes of puberty hormones. PLoS One. 2015;10(11):e0143555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Courant F, Aksglaede L, Antignac JP, Monteau F, Sorensen K, Andersson AM, Skakkebaek NE, Juul A, Bizec BL. Assessment of circulating sex steroid levels in prepubertal and pubertal boys and girls by a novel ultrasensitive gas chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry method. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010;95(1):82–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Biro FM, Greenspan LC, Galvez MP, Pinney SM, Teitelbaum S, Windham GC, Deardorff J, Herrick RL, Succop PA, Hiatt RA, Kushi LH, Wolff MS. Onset of breast development in a longitudinal cohort. Pediatrics. 2013;132(6):1019–1027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Biro FM, Galvez MP, Greenspan LC, Succop PA, Vangeepuram N, Pinney SM, Teitelbaum S, Windham GC, Kushi LH, Wolff MS. Pubertal assessment method and baseline characteristics in a mixed longitudinal study of girls. Pediatrics. 2010;126(3):e583–e590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Marshall WA, Tanner JM. Variations in pattern of pubertal changes in girls. Arch Dis Child. 1969;44(235):291–303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Division of Nutrition, Physical Activity, and Obesity. Growth Chart Training. A SAS Program for the 2000 CDC Growth Charts (ages 0 to <20 years). Available at: www.cdc.gov/nccdphp/dnpao/growthcharts/resources/sas.htm. Accessed 30 July 2018.

- 8. Zeger SL, Liang KY, Albert PS. Models for longitudinal data: a generalized estimating equation approach. Biometrics 1988;44:1049–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Biro FM, Emans SJ. Whither PCOS? The challenges of establishing hyperandrogenism in adolescent girls. J Adolesc Health. 2008;43(2):103–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Sizonenko PC, Paunier L. Hormonal changes in puberty III: correlation of plasma dehydroepiandrosterone, testosterone, FSH, and LH with stages of puberty and bone age in normal boys and girls and in patients with Addison’s disease or hypogonadism or with premature or late adrenarche. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1975;41(5):894–904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ducharme JR, Forest MG, De Peretti E, Sempé M, Collu R, Bertrand J. Plasma adrenal and gonadal sex steroids in human pubertal development. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1976;42(3):468–476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Aksglaede L, Sørensen K, Petersen JH, Skakkebaek NE, Juul A. Recent decline in age at breast development: the Copenhagen Puberty Study. Pediatrics. 2009;123(5):e932–e939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Cleveland WS, Devlin SJ. Locally weighted regression: an approach to regression analysis by local fitting. J Am Stat Assoc. 1988;83(403):596–610. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Biro FM, Pajak A, Wolff MS, Pinney SM, Windham GC, Galvez MP, Greenspan LC, Kushi LH, Teitelbaum SL. Age of menarche in a longitudinal US cohort. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2018;31(4):339–345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]