ABSTRACT

The Class 2 Type V-A CRISPR effector protein Cas12a/Cpf1 has gained widespread attention in part because of the ease in achieving multiplexed genome editing, gene regulation, and DNA detection. Multiplexing derives from the ability of Cas12a alone to generate multiple guide RNAs from a transcribed CRISPR array encoding alternating conserved repeats and targeting spacers. While array design has focused on how to optimize guide-RNA sequences, little attention has been paid to sequences outside of the CRISPR array. Here, we show that a structured hairpin located immediately downstream of the 3ʹ repeat interferes with utilization of the adjacent encoded guide RNA by Francisella novicida (Fn)Cas12a. We first observed that a synthetic Rho-independent terminator immediately downstream of an array impaired DNA cleavage based on plasmid clearance in E. coli and DNA cleavage in a cell-free transcription-translation (TXTL) system. TXTL-based cleavage assays further revealed that inhibition was associated with incomplete processing of the transcribed CRISPR array and could be attributed to the stable hairpin formed by the terminator. We also found that the inhibitory effect partially extended to upstream spacers in a multi-spacer array. Finally, we found that removing the terminal repeat from the array increased the inhibitory effect, while replacing this repeat with an unprocessable terminal repeat from a native FnCas12a array restored cleavage activity directed by the adjacent encoded guide RNA. Our study thus revealed that sequences surrounding a CRISPR array can interfere with the function of a CRISPR nuclease, with implications for the design and evolution of CRISPR arrays.

KEYWORDS: Cpf1, CRISPR, RNA structure, terminator, TXTL

Introduction

Type V-A CRISPR-Cas systems and their Cas12a (previously called Cpf1) nucleases have gained broad interest as powerful tools within the expanding CRISPR toolbox [1–3]. Unlike the traditional Cas9 nuclease from Type II CRISPR-Cas systems, Cas12a prefers a T-rich PAM located 5ʹ of the matching target sequence, and the nuclease cleaves in a staggered fashion distal to the PAM site [4]. Cas12a has also been shown to exhibit lower off-target cleavage compared to SpyCas9 in human cells [4–6].

Aside from its distinct DNA targeting properties, Cas12a can use one of its own endonucleolytic domains to generate individual guide RNAs. These guide RNAs are processed from a pre-crRNA, the transcription product of the CRISPR array, and can be used to target different DNA loci at the same time [4,7,8]. This capability lends to numerous multiplexing applications with Cas12a, as multiple guide RNAs can be processed from a single CRISPR array. More recent examples of multiplexing applications with Cas12a include multi-site genome editing and gene activation [9,10], and opportunities are emerging for multiplexed base editing and DNA sensing using Cas12a [11,12]. Furthermore, recent advances have made the generation of large CRISPR arrays more straightforward and efficient [13]. With these opportunities and advances, the ensuing question is how to efficiently design CRISPR arrays to maximize the DNA targeting of Cas12a directed by each encoded guide RNA.

To-date, the primary focus for array design has been on the individual spacers and repeats. For instance, recent advances in spacer selection account for factors that influence Cas12a activity, such as GC content, secondary structure, melting temperature, and position-specific nucleotide composition [14,15]. Separately, the length of the direct repeat has also been shown to impact Cas12a activity in yeast and in mammalian cells [9,16]. However, the potential impact of flanking sequences outside of a CRISPR-Cas12a array–sequence that appear within the transcript but are removed as part of guide RNA processing–remains to be explored.

In this study, we used the well-characterized Cas12a from Francisella novicida (FnCas12a) [4,17–19] to show that a hairpin structure downstream of the terminal repeat in single-spacer and multi-spacer CRISPR arrays impaired DNA targeting directed by the encoded guide RNAs. The inhibitory effect was observed for a synthetic Rho-independent transcriptional terminator and larger hairpins but was absent for smaller hairpins. We also demonstrated that removing the terminal repeat from the CRISPR array resulted in even stronger inhibition, while replacing this repeat with a functionally-deficient terminal repeat from a native FnCas12a array greatly restored DNA targeting activity. Our study thus identified an important factor for the design and evolution of Cas12a arrays, and it offered a simple solution when stable secondary structures cannot be avoided.

Results

A synthetic Rho-independent terminator immediately downstream of a CRISPR array impaired targeting activity

We previously assayed the activity of the FnCas12a nuclease for targeted plasmid clearance in E. coli, which revealed one construct harboring a plasmid-targeting CRISPR array with greatly diminished clearance activity. The clearance assays were conducted by transforming a plasmid encoding a CRISPR array into an E. coli strain harboring an FnCas12a-expressing plasmid and a separate plasmid encoding the target sequence and canonical PAM (Figure 1(a)). Clearance activity could then be assessed based on the relative number of transformants with the tested array versus a no-spacer control (pC) [13,19]. The expectation was that Cas12a-mediated clearance of the target plasmid would sensitize cells to one of the antibiotics, greatly reducing the number of colonies compared to the no-spacer control. While testing different plasmids encoding the same spacer (S1) in a single-spacer array (Figure 1(a)), we identified one construct (psRT-1) that yielded a smaller drop in the number of transformants compared to other plasmids with the same single-spacer array (Figure 1(b)). The smaller size of the resulting colonies suggested that Cas12a still exhibited some activity based on slow colony growth (Figure S1). One notable feature of the psRT-1 construct is a synthetic Rho-independent terminator immediately downstream of the 3ʹ repeat used in our prior work [20] (Figure S2). We therefore hypothesized that the immediately adjacent terminator was interfering with CRISPR activity.

Figure 1.

A synthetic Rho-independent terminator immediately downstream of the 3ʹ repeat impairs cleavage activity directed by a single-spacer array. (A) Schematic of the plasmid clearance assay. E. coli cells harboring a plasmid expressing FnCas12a and a plasmid containing the PAM-flanked target sequence were transformed with a targeting or no-spacer CRISPR array plasmid. Successful targeting results in fewer antibiotic-resistant colonies compared to that of the no-spacer array. (B) Plasmid clearance results with FnCas12a in E. coli. pC encodes a no-spacer array, psRT-1 encodes an array with a synthetic Rho-independent terminator immediately downstream of the 3ʹ repeat, and psR-1 encodes an array with the rrnB Rho-independent terminator ~ 88 nts downstream of the 3ʹ repeat. Black bars represent direct repeats, blue bars represent a spacer targeting site 1 (S1), and gray hairpins followed by U’s represent Rho-independent terminators. Sequences of the CRISPR array constructs are reported in Table S1. psR-1 and psRT-1 contain slightly shorter transcribed regions upstream of the 5ʹ repeat compared to pC and the other constructs used in Figure 2–5. Values represent the geometric mean and S.D. from three independent experiments starting with separate colonies. (C) DNA cleavage by FnCas12a using an all-E. coli cell-free transcription-translation (TXTL) system. The FnCas12a plasmid and the CRISPR array plasmid were incubated in the TXTL mix for 2 hours. The deGFP reporter plasmid was then added, and GFP fluorescence was measured over time. Target cleavage by FnCas12a leads to rapid degradation of the plasmid by RecBCD, resulting in cessation of deGFP production. (D) Time courses of GFP fluorescence in TXTL. Each curve matches to the corresponding CRISPR array from panel B. The %GFP is the fluorescence measurement with the tested array divided by that with the no-spacer array at 5 hours following the addition of the reporter plasmid. Each solid line and surrounding colored curve represent the mean and S.D., respectively, from triplicate experiments conducted on separate days. Inset: the same curves for the entire 16-hour experiment. The gray vertical line indicates the 5-hour timepoint used to quantify %GFP.

To assess whether the limited plasmid clearance by FnCas12a was due to the adjacent synthetic terminator, we generated another CRISPR construct (psR-1) in which the synthetic terminator in psRT-1 was deleted. Transcription of the resulting construct instead would be expected to terminate with a downstream Rho-independent rrnB terminator already present in the plasmid, where ~88 bps separate the 3ʹ repeat and the beginning of the region specified as the rrnB terminator (Figure 1(b)). We note that the rrnB terminator is unrelated to the synthetic Rho-independent terminator used in psRT-1. We found that the targeting construct with a distant downstream rrnB terminator (psR-1) resulted in greatly enhanced plasmid clearance in comparison to the targeting construct with the flanking synthetic terminator (psRT-1) (Figures 1(b) and S1). This result supports the inhibitory role of the immediately adjacent Rho-independent terminator.

We next investigated the ability of the two targeting constructs to direct DNA cleavage by FnCas12a in an all-E. coli cell-free TXTL system [21]. We previously used this system to interrogate the activity of CRISPR nucleases and guide RNAs, and it provides a quantitative and dynamic readout of nuclease activity [13,22]. As part of the assay, the FnCas12a plasmid and a CRISPR array plasmid were incubated in the TXTL mix for two hours. A deGFP reporter plasmid, which encodes a modified version of eGFP as well as the target sequence upstream of the promoter driving deGFP expression, was then added and GFP, fluorescence was measured over time on a fluorescence microplate reader [23]. Target cleavage by FnCas12a leads to rapid plasmid degradation by RecBCD, resulting in cessation of deGFP production (Figure 1(c)) [24]. As expected, cleavage mediated by the single-spacer construct with no immediate downstream terminator (psR-1) resulted in greatly reduced GFP production, with GFP levels at 7% of the no-spacer control five hours after the addition of the GFP reporter. In contrast, the single-spacer construct with an immediately downstream terminator (psRT-1) led to a more modest reduction in GFP production, with GFP levels at 32% compared to the no-spacer control (Figure 1(d)). TXTL-based cleavage therefore correlates with the extent of plasmid clearance in E. coli. The delayed cleavage with the immediately downstream terminator would be in line with slow colony growth in the plasmid clearance assays (Figure S1). Given the rapid nature of TXTL, we used this technique to further interrogate how the immediately adjacent terminator caused the reduction in DNA targeting by FnCas12a.

The stable secondary structure rather than transcriptional termination explains the loss of DNA cleavage activity

The presence of the immediate terminator suggested that either transcriptional termination or the large hairpin was responsible for the diminished clearance activity. To investigate either possibility, we generated two variants of the single-spacer array with the immediately downstream synthetic terminator (pRT-1). In one variant (pRH-1), we deleted the DNA sequence encoding the string of uridines in the terminator, resulting in a predicted 10-bp hairpin that would be transcriptionally extended to the downstream rrnB terminator. In the other variant (pRHS-1), nucleotides (nts) on the 3ʹ end of the hairpin in pRH-1 were deleted, resulting in a predicted 5-bp hairpin that also would be transcriptionally extended to the downstream rrnB terminator. The constructs along with the single-spacer array with the immediately adjacent terminator (pRT-1) or the far downstream terminator (pR-1) were tested for DNA cleavage activity in TXTL.

The TXTL-based cleavage assays revealed that the constructs with a long hairpin immediately following the terminal repeat (pRT-1, pRH-1) mediated less cleavage activity compared to the array plasmid with no hairpin structure (pR-1). In contrast, the construct with a shorter hairpin structure (pRHs-1) exhibited similar cleavage activity as pR-1 (Figure 2(a)). This result implied that the hairpin structure rather than transcription termination was responsible for the reduced DNA targeting activity directed by the adjacent spacer. In further support of this conclusion, the constructs with the downstream rrnB terminator (pR-1, pR-2) was not predicted to form any appreciable secondary structures adjacent to the 3ʹ repeat (Figure S3) [25].

Figure 2.

Impaired DNA cleavage activity can be attributed to a stable hairpin structure immediately downstream of the 3ʹ repeat. A series of constructs were generated encoding a single-spacer array with a spacer targeting (A, C) site 1 (S1, blue bar) or (B) site 2 (S2, purple bar). The terminal repeat of each array was followed by a distant rrnB terminator (pR-1, pR-2), an immediately adjacent synthetic Rho-independent terminator (pRT-1, pRT-2), a larger hairpin of similar predicted secondary structure as the Rho-independent terminator (pRH-1, pRH-2), or a shorter hairpin (pRHS-1, pRHS-2). (C) Hairpins with a different number of predicted base pairs (red lines) were also tested for their inhibitory effect on DNA cleavage activity. See Figure S2 for sequences of the region immediately downstream of the 3ʹ repeat. The TXTL-based cleavage assays were then conducted as described in Figure 1C using a reporter plasmid with the target sequence cloned into the plasmid backbone. Fluorescence values are reported as the GFP fluorescence of the tested array divided by that of the no-spacer array 5 hours after the addition of the reporter plasmid. Values and error bars represent the mean and S.D., respectively, from triplicate experiments conducted on different days.

To assess whether the inhibitory effect was not particular to the space sequence, we generated the same set of array plasmids for another spacer (S2), and we inserted the associated target sequence within the deGFP reporter plasmid (Figure 2(b)). TXTL-based cleavage assays showed that the constructs with no hairpin (pR-2) or a short hairpin (pRHS-2) exhibited similarly high cleavage activities, while the two constructs with longer hairpins (pRT-2, pRH-2) exhibited diminished cleavage activity. Therefore, the inhibitory effect of the adjacent hairpin was independent of the selected spacer.

We also tested how the exact size of the flanking hairpin affects DNA cleavage activity. To accomplish this, we generated four single-spacer arrays (pRH2-1, pRH4-1, pRH6-1, and pRH8-1) each with a differently-sized hairpin downstream of the CRISPR array (Figure S2). The hairpins all shared the same distance between the 3ʹ repeat and the base of the hairpin stem. We then measured DNA cleavage activities of these arrays along with the array with no predicted flanking hairpin (pR-1) and the array with a predicted 10-bp hairpin (pRH-1). The result showed that the arrays with up to 6 base pairs within the predicted hairpin exhibited substantial DNA targeting activity comparable to the one with no flanking hairpin, while arrays with at least 8 predicted base pairs in the hairpin dramatically diminished the DNA targeting activity directed by the spacer in the array (Figure 2(c)). We also tested a single-spacer array with an entirely different sequence in the hairpin but the same predicted secondary structure as pRH (pRHn-1, Figure S2). We found that this hairpin also reduced DNA cleavage by FnCas12a, albeit to a lesser degree than the original hairpin in pRH (Figure S4). Overall, these results suggest that the observed inhibitory activity is due to the stable secondary structure rather than the sequence of the flanking hairpin.

The stable hairpin flanking the 3ʹ repeat interferes with guide RNA processing

We next asked why the strong hairpin reduced DNA cleavage by FnCas12a. We hypothesized that the hairpins were impacting processing the transcribed arrays. To test this, we expressed FnCas12a and one of the single-spacer arrays with (pRH-1) or without (pR-1) the flanking large hairpin using TXTL. We then performed Northern blotting analysis on the extracted RNA using a probe complementary to the transcribed spacer S1 (Figure 3). The resulting gel images showed that the presence of the large flanking hairpin in the transcribed array led to the accumulation of intermediate RNA products that presumably represent incomplete pre-crRNA processing. The gels also showed a lower abundance of processed guide RNAs (Figure 3). The diminished cleavage activity directed by the spacer therefore may be attributed to a reduction in the abundance of processed guide RNAs, although other mechanisms may contribute.

Figure 3.

The presence of the stable hairpin flanking the 3ʹ repeat yields incomplete pre-crRNA processing and a lower abundance of guide RNAs. Single-spacer CRISPR arrays with (pRH-1) or without (pR-1) a stable hairpin flanking the 3ʹ repeat were expressed along with FnCas12a using the cell-free TXTL system, and the purified RNAs were subjected to Northern blotting analysis. An oligonucleotide probe was designed to base pair with the first 26 nts of the transcribed spacer. The area around the fully processed guide RNA is shown with greater exposure (box with dashed line). 5S RNA was probed to show equal loading of purified RNA. The gel images are representative of three independent experiments.

The stable hairpin flanking the 3' repeat also inhibits DNA cleavage activity by non-adjacent spacers

Given that CRISPR arrays can encode multiple guide RNAs, we asked how the adjacent hairpin would impact DNA cleavage activity directed by spacers upstream in a multi-spacer array. We first generated two-spacer arrays with both S1 and S2 in the context of the different downstream structures. To examine each spacer, we performed the TXTL-based cleavage assay using the deGFP reporter plasmid harboring either of the target sequences. As observed for the single-spacer arrays, the spacer immediately adjacent to the terminator or large hairpin yielded lower cleavage activity compared to the same spacer with no hairpin or a small hairpin (Figure 4). In contrast, the upstream spacers yielded a more modest but statistically significant inhibitory effect (see statistical analysis in Methods), where the effect was slightly stronger for spacer S2 versus S1 in this upstream position (Figure 4). We also measured the DNA targeting activity directed by the upstream-most spacer in a three-spacer array in the presence (pRT-213) or absence (pR-213) of the flanking strong hairpin (Figure S2). We found that DNA cleavage activity by the upstream spacer did decrease modestly but statistically significantly in the presence of the large hairpin (see statistical analysis in Methods) (Figure S5), suggesting that a hairpin can affect the DNA cleavage activity directed by spacers farther away from the terminal repeat–at least to a marginal degree. In summary, a structured hairpin flanking the CRISPR array can reduce the DNA targeting activity of upstream spacers in a multi-spacer array, albeit with diminished effect.

Figure 4.

The hairpin structure immediately following a two-spacer array can partially impair cleavage activity directed by the upstream spacer. Two-spacer arrays encoding spacers targeting site 1 (blue) or site 2 (purple) were generated with the set of downstream sequences reported in Figure 2. The resulting arrays were tested in TXTL with FnCas12a and either of the targeted deGFP reporter plasmids as described in Figure 1C. See Figure S2 for sequences of the region immediately downstream of each terminal repeat, and see Table S1 for the full sequence of the constructs. Fluorescence values are reported as the GFP fluorescence of the tested array divided by that of the no-spacer array 5 hours after the addition of the reporter plasmid. Values and error bars represent the mean and S.D., respectively, from triplicate experiments conducted on different days.

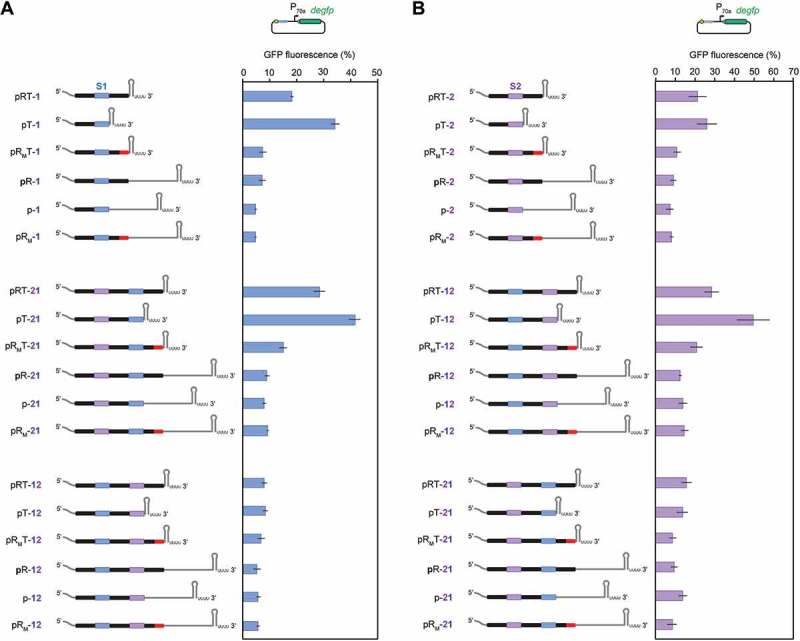

A native terminal repeat but not the absence of a repeat can restore DNA cleavage activity

We next explored whether the spacer could be protected from the inhibitory effect of a potential downstream hairpin or secondary structure. One possibility is eliminating the 3ʹ repeat in the CRISPR array, as multiple studies have shown that the terminal repeat is dispensable for generating a functional guide RNA [4,5,9]. However, eliminating the 3ʹ repeat enhanced the inhibitory effect for both tested spacers, whether in the single-spacer arrays (pT-1, pT-2) or as the downstream spacer in the two-spacer arrays (pT-12, pT-21) (Figure 5). Another possibility is introducing the terminal repeat in the native CRISPR-Cas12a array from Francisella novicida [4,17], as these repeats harbor mutations predicted to disrupt processing and could help shield native arrays from any flanking secondary structures [13]. We found that using this repeat in arrays with the adjacent terminator restored the activity of the spacer in the single-spacer arrays (pRMT-1, pRMT-2) and the downstream spacer in the two-spacer arrays (pRMT-12, pRMT-21). In some cases, DNA cleavage activity directed by an array with the native terminal repeat was indistinguishable from that for the arrays with the far downstream terminator and no obvious stable secondary structures adjacent to the 3ʹ repeat (e.g. pR-1) (Figure 5). As expected, eliminating the 3ʹ repeat or using the native terminal repeat had a negligible impact on DNA cleavage activity for arrays only with the far downstream rrnB terminator. The native terminal repeat therefore can shield Cas12a CRISPR arrays from potentially interfering secondary structures.

Figure 5.

Removing the 3ʹ repeat can further disrupt DNA cleavage activity by FnCas12a, while replacing the 3ʹ repeat with a native terminal repeat can restore cleavage activity. The TXTL-based cleavage activity of the spacer targeting (A) site 1 (S1, blue) or (B) site 2 (S2, purple) were tested as part of CRISPR array constructs in which the terminal repeat was deleted (pT-X, p-X) or replaced with the terminal repeat native to the Type V-A CRISPR-Cas system in F. novicida U112 (pRMT-X). The mutated part of the repeat corresponding to the native terminal repeat is shown in red, where the mutations are expected to disrupt binding and processing by FnCas12a. The TXTL-based cleavage assays were conducted as described in Figure 1C. See Figure S2 for sequences of the region immediately downstream of each terminal repeat or the spacer, and see Table S1 for the full sequence of the constructs. Fluorescence values are reported as the GFP fluorescence of the tested array divided by that of the no-spacer array 5 hours after the addition of the reporter plasmid. Values and error bars represent the mean and S.D., respectively, from triplicate experiments conducted on different days.

Discussion

In this study, we found that a synthetic Rho-independent terminator immediately downstream of the 3ʹ repeat of a FnCas12a CRISPR array reduced FnCas12a-mediated DNA cleavage directed by the adjacent spacer. We traced the inhibitory effect to the stable secondary structure formed by the terminator, which was linked with incomplete pre-crRNA processing and reduced generation of the processed guide RNA. There appeared to be some threshold for the size or stability of the hairpin, as hairpins with no more than a predicted 6-bp stem yielded negligible inhibition compared to an unstructured sequence. We also noticed that the inhibitory effect partially extended to non-adjacent spacers on a two-spacer array and a three-spacer array. The inhibitory effect was greatly reduced for these upstream spacers, suggesting that the effect can extend beyond the immediate vicinity of the hairpin in the array. While the inhibitory effect on these upstream spacers was modest, any array would have at least one poorly active spacer at the end of the array in the presence of an adjacent stable secondary structure. Regardless, our findings show that not only internal sequences (e.g. spacers, repeats) but also external sequences should be considered as part of array design and may have influenced the evolution of CRISPR arrays.

We also investigated ways of countering the inhibitory effect of the immediately adjacent hairpin beyond disrupting the stable secondary structure. One way that we investigated was removing the 3ʹ repeat given the common reliance on guide RNAs lacking this repeat. However, we found that removing this repeat enhanced the inhibitory effect of the hairpin on cleavage activity. This observation is important given that bacterial expression systems would normally include a Rho-independent terminator to generate a Cas12a guide RNA. In contrast, we found that DNA cleavage activity could be restored by replacing the 3ʹ repeat with the native terminal repeat from the endogenous CRISPR array, which contained mutations predicted to disrupt Cas12a binding and processing. Given the prevalence of disruptive mutations in native Cas12a terminal repeats [13], these repeats should be available for most Cas12a nucleases and may be interchangeable between different Cas12a nucleases.

While we found that the stable hairpin immediately downstream of the 3ʹ repeat was linked to reduced DNA cleavage activity, different mechanisms could underlie this effect. Our Northern blotting analysis suggested that the hairpin interfered with the processing of the pre-crRNA, resulting in the build-up of intermediate processing products and less guide RNA to direct FnCas12a. These products corresponded to the sizes of the transcribed array and hairpin with (~178 nts) or without (~118 nts) the 5ʹ transcribed region, although follow-up work will be needed to confirm the true identity of these products. If confirmed, the remaining hairpin in both products may prevent binding by FnCas12a or it may prevent the gRNA-Cas12a complex from binding or cleaving DNA. We note that both mechanisms are supported by our experiments with the deleted or replaced 3ʹ repeat (Figure 5). Specifically, deleting the 3ʹ repeat would bring the hairpin in closer proximity to the portion of the pre-crRNA used to generate the guide RNA, while the native repeat would not be processed by FnCas12a and therefore would increase the spacing. Still, other mechanisms may be at play, such as RNA polymerase remaining bound to the transcribed pre-crRNA, blocking access by FnCas12a. Overall, more detailed biochemical studies could help tease out these mechanisms, such as evaluating binding between FnCas12a and the processing intermediates or testing the ability of any resulting ribonucleoprotein complexes to bind and cleave target DNA.

We previously found that the 3ʹ repeat within an FnCas12a array gives rise to an unexpected CRISPR RNA [13]. Given that the adjacent hairpin fell within the spacer that would be derived from the transcribed 3ʹ repeat, it implies that–at least for FnCas12a–a highly structured spacer may inhibit the processing or DNA targeting activity of adjacent guide RNAs within the pre-crRNA. If so, this effect not only could be critical for array design; it could also introduce a potential drawback if an endogenous CRISPR-Cas system acquires a highly structured spacer, thereby inhibiting DNA targeting directed by the adjacent spacers that are otherwise functional.

One question from our work is how immediately adjacent secondary structures impact other Cas12a proteins as well as other CRISPR-Cas types and subtypes. We expect that Cas12a orthologs (e.g. AsCas12a, LbCas12a) are also sensitive to the structure downstream of the transcribed 3ʹ repeat on CRISPR arrays because they all share similar protein conformations and mechanisms of array processing. However, the impact on other CRISPR-Cas types and subtypes remains unknown. We predict that the sensitivity will depend not only on the mechanism of processing but also on whether a guide RNA is derived from a transcribed 5ʹ repeat (Type V, IV) or a 3ʹ repeat (Type I, II, III). The only available evidence is from the Type I-E CRISPR-Cas system, native to E. coli, where we previously used the same construct with the adjacent transcriptional terminator to express functional guide RNAs for gene repression and genome destruction [20,26]. Therefore, the I-E CRISPR-Cas system appears to be insensitive to downstream structure. It will be interesting to see whether secondary structure impacts other CRISPR-Cas systems and how this impact might have influenced the evolution of different CRISPR arrays.

Materials and methods

Strains and growth conditions

All strains used in this work are listed in Table S1. The in vivo plasmid clearance assays were conducted in CB414, a derivative of E. coli BW25113 with the lacI promoter through the lacZ gene and the endogenous I-E CRISPR-Cas system deleted [19]. All plasmid constructs were generated using DH5α chemically competent cells (NEB, Catalog # c29871) and verified by PCR and Sanger sequencing. E. coli cells were grown in Luria Bertani (LB) medium (10 g/L NaCl, 5 g/L yeast extract, 10 g/L tryptone) at 37°C with shaking at 250 rpm. The antibiotics ampicillin, chloramphenicol, and/or kanamycin were added to maintain any plasmids at final concentrations of 50 µg/mL, 34 µg/mL, and 50 µg/mL, respectively.

Plasmid construction

All plasmids and oligonucleotides used in this work are listed in Table S1. The backbone plasmid pC used for generating arrays was constructed as described previously [13]. Briefly, three PCR fragments – (1) a constitutive J23119 promoter with assembly sequence upstream, (2) a GFP-dropout cassette flanked by two Type IIS BsmBI restriction sites and the consensus direct repeat of FnCas12a, and (3) a plasmid backbone containing an rrnB terminator, ampicillin resistance cassette, and pMB1 origin-of-replication – were ligated together by Gibson Assembly. Backbone plasmids used to construct the CRISPR arrays with an immediately downstream terminator (pRT-X), a long (pRH) or short (pRHS) hairpin structure, deleted terminal repeat (pT-X), native terminal repeat (pRMT-X), mutated repeat and deleted terminator (pRM-X), or a deleted terminal repeat and terminator (p-X) were generated from plasmid pR-X backbone (see Table S1 for sequence) with the Q5 mutagenesis kit (New England Biolabs, Cat # E0554S) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Single-spacer, two-spacer, three-spacer, and no-spacer arrays were constructed as described previously using the corresponding backbone plasmids [13]. Briefly, repeat-spacer subunits were formed by annealing phosphorylated oligonucleotides and then ligated in place of the dropout cassette on the backbone plasmid, thereby generating the CRISPR array. For experiments in E. coli and TXTL, FnCas12a was expressed under the control of the J23108 promoter in a pBAD33 backbone as described previously [13]. Plasmid clearance assays were conducted with pUA66-lacZ (CB884) as the targeted plasmid [27]. Reporter plasmids used in TXTL-based DNA cleavage assays were constructed via Q5 mutagenesis by inserting each PAM-flanked protospacer 168 nts upstream of the −35 element of the P70a promoter in a p70a-deGFP plasmid.

Plasmid-clearance assays

Plasmid-clearance assays were conducted as described previously [13]. Briefly, 50 ng of the plasmid encoding the CRISPR array was electroporated into E. coli cells harboring a plasmid encoding FnCas12a and the pUA66-lacZ plasmid encoding a PAM-flanked protospacer. Recovered cells were then serially diluted, and 10-µl droplets were plated on LB agar plates with ampicillin, kanamycin, and chloramphenicol. The number of surviving colonies are reported.

TXTL-based DNA cleavage assays

The cleavage assays were performed paralleling prior work [13]. The FnCas12a plasmid and the CRISPR array plasmid were added into 9 µl of MyTXTL master mix (Arbor Biosciences, Cat # MYtxtl-70–96-M) to the same final concentration of 4.17 nM and a total volume of 11 µl. The mix was then incubated at 29°C for 2 hours. Then, 1 µl of the targeted deGFP reporter plasmid was added to a final concentration of 0.83 nM. Aliquots of 5 µl were placed in the wells of a 96-well V-bottom plate (Corning Costar, Cat # 3357) and incubated at 37 °C for 16 hours in a Synergy H1MF microplate reader (BioTek, USA) with kinetic reading every 3 minutes (excitation – 485 nm, emission – 528 nm, gain – 60, light source – Xenon Flash). The %GFP was calculated as the fluorescence measurement of the targeting construct divided by that of the no-spacer array at 5 hours following the addition of the deGFP reporter plasmid. The background fluorescence of the TXTL mix was negligible at this time point. We selected 5 hours to calculate %GFP because fluorescence ceased to increase in reactions with all targeting constructs by this timepoint. Furthermore, later timepoints (e.g. 16 hours) would artificially lower the reported GFP% because fluorescence would continue to increase for the no-spacer control. All fluorescence timecourse profiles showed a similar trend in which fluorescence initially increased on par with the no-spacer control followed by the fluorescence ceasing to increase any time thereafter.

Northern blotting analysis

Plasmid encoding FnCas12a was added into 9 μl of the MyTXTL master mix (Arbor Biosciences, Cat # MYtxtl-70–96-M) to a final concentration of 4.17 nM and a total volume of 11 μl in a PCR tube and incubated at 29°C for two hours. Then, 1 µl of the array plasmid was added to a final concentration of 0.83 nM and a total volume of 12 μl. The mixture was incubated at 29°C for five hours in a thermocycler, and total RNA was extracted using Direct-zol reagent and RNA Clean and Concentrator™-25 kit with on-column RNase treatment following the manufacturer’s instructions (Zymo Research). For Northern blotting analysis, 5 μg of each RNA was separated on an 8% polyacrylamide gel containing 7 M urea at 300 V for 140 minutes using a gel transfer system (Doppel-Gelsystem Twin L, PerfectBlue). RNA was transferred onto Hybond-XL membranes (Amersham Hybond-XL, GE Healthcare) using an Electroblotter with an applied voltage of 50 V for 1 hour at 4°C (Tank-Elektroblotter Web M, PerfectBlue), crosslinked with UV-light at 0.12 Joules (UV-lamp T8C; 254 nm, 8W), hybridized overnight in 17 ml Roti-Hybri-Quick buffer at 42°C with 5 µl γ 32P-ATP end-labeled oligodeoxyribonucleotides (Table S1) and visualized on a Phosphorimager (Typhoon FLA 7000, GE Healthcare).

RNA folding prediction

The RNA folding prediction software NUPACK (www.nupack.org)25 was used to predict the folding of an RNA spanning the beginning of the 3ʹ repeat to the end of the rrnB terminator in the pR-X constructs. The default parameter set within NUPACK was used for the predictions.

Statistical analyses

The two-tailed student’s t-test was used to evaluate statistical significance of the GFP fluorescence (%) for the upstream spacer in two-spacer and three-spacer arrays. All tests were performed with three independent replicates for each sample (n = 3). The comparisons resulted in statistically significant differences for pR-12 versus pRT-12 (p = 0.05), pR-12 versus pRH-12 (p = 0.02), pR-21 versus pRT-21 (p = 0.03), pR-21 versus pRH-21 (p = 0.01), and pR-213 versus pRT-213 (p = 0.01) based on a threshold of p = 0.05.

Funding Statement

The work was supported through funding from the National Institutes of Health (1R35GM119561 to C.L.B.), Agilent Technologies (Gift #3926 to C.L.B.), and the Camille & Henry Dreyfus Foundation (2017-137 to C.L.B.).

Acknowledgments

We thank Franziska Wimmer for helpful feedback on the manuscript.

Author Contributions

C.L. and C.L.B. conceived this study and designed the experiments. C.L. performed the array cloning and experiments with TXTL; C.L. and R.A.S. conducted the plasmid clearance arrays in E. coli. C.L.; T.A. performed the Northern blotting analysis; and C.L. and C.L.B. analyzed the data. C.L. and C.L.B. wrote the manuscript, which was read and approved by all authors.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Supplementary material

Supplemental data can be accessed here

References

- [1].Murugan K, Babu K, Sundaresan R, et al. The revolution continues: newly discovered systems expand the CRISPR-Cas toolkit. Mol Cell. 2017;68:15–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Fagerlund RD, Staals RHJ, Fineran PC.. The Cpf1 CRISPR-Cas protein expands genome-editing tools. Genome Biol. 2015;16:251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Zaidi SS-E-A, Mahfouz MM, Mansoor S. CRISPR-Cpf1: A new tool for plant genome editing. Trends Plant Sci. 2017;22:550–553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Zetsche B, Gootenberg JS, Abudayyeh OO, et al. Cpf1 is a single RNA-guided endonuclease of a class 2 CRISPR-Cas system. Cell. 2015;163:759–771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Kim D, Kim J, Hur JK, et al. Genome-wide analysis reveals specificities of Cpf1 endonucleases in human cells. Nat Biotechnol. 2016;34:863–868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Kleinstiver BP, Tsai SQ, Prew MS, et al. Genome-wide specificities of CRISPR-Cas Cpf1 nucleases in human cells. Nat Biotechnol. 2016;34:869–874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Fonfara I, Richter H, Bratovič M, et al. CRISPR-associated DNA-cleaving enzyme Cpf1 also processes precursor CRISPR RNA. Nature. 2016;532:517–521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Zhong G, Wang H, Li Y, et al. proteins excise CRISPR RNAs from mRNA transcripts in mammalian cells. Nat Chem Biol. 2017;13:839–841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Zetsche B, Heidenreich M, Mohanraju P, et al. Multiplex gene editing by CRISPR–cpf1 using a single crRNA array. Nat Biotechnol. 2016;35:31–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Tak YE, Esther Tak Y, Kleinstiver BP, et al. Inducible and multiplex gene regulation using CRISPR–cpf1-based transcription factors. Nat Methods. 2017;14:1163–1166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Li X, Wang Y, Liu Y, et al. Base editing with a Cpf1–cytidine deaminase fusion. Nat Biotechnol. 2018;36:324–327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Gootenberg JS, Abudayyeh OO, Kellner MJ, et al. Multiplexed and portable nucleic acid detection platform with Cas13, Cas12a, and Csm6. Science. 2018;360:439–444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Liao C, Ttofali F, Slotkowski RA, et al. One-step assembly of large CRISPR arrays enables multi-functional targeting and reveals constraints on array design. 2018. DOI: 10.1101/312421 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Kim HK, Song M, Lee J, et al. In vivo high-throughput profiling of CRISPR–cpf1 activity. Nat Methods. 2016;14:153–159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Zhu H, Liang C. CRISPR-DT: designing gRNAs for the CRISPR-Cpf1 system with improved target efficiency and specificity. 2018. DOI: 10.1101/269910 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Swiat MA, Dashko S, Den Ridder M, et al. FnCpf1: a novel and efficient genome editing tool for Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017;45:12585–12598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Schunder E, Rydzewski K, Grunow R, et al. First indication for a functional CRISPR/Cas system in Francisella tularensis. Int J Med Microbiol. 2013;303:51–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Tu M, Lin L, Cheng Y, et al. A “new lease of life”: fnCpf1 possesses DNA cleavage activity for genome editing in human cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017;45:11295–11304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Leenay RT, Maksimchuk KR, Slotkowski RA, et al. Identifying and visualizing functional PAM diversity across CRISPR-Cas systems. Mol Cell. 2016;62:137–147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Luo ML, Mullis AS, Leenay RT, et al. Repurposing endogenous type I CRISPR-Cas systems for programmable gene repression. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43:674–681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Shin J, Noireaux V. Efficient cell-free expression with the endogenous E. coli RNA polymerase and sigma factor 70. J Biol Eng. 2010;4:8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Marshall R, Maxwell CS, Collins SP, et al. Rapid and scalable characterization of CRISPR technologies using an E. coli cell-free transcription-translation system. Mol Cell. 2018;69:146–157.e3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Shin J, Noireaux V. An E. coli cell-free expression toolbox: application to synthetic gene circuits and artificial cells. ACS Synth Biol. 2012;1:29–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Sitaraman K, Esposito D, Klarmann G, et al. A novel cell-free protein synthesis system. J Biotechnol. 2004;110:257–263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Zadeh JN, Steenberg CD, Bois JS, et al. Analysis and design of nucleic acid systems. J Comput Chem. 2011;32:170–173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Luo ML, Jackson RN, Denny SR, et al. The CRISPR RNA-guided surveillance complex in Escherichia coli accommodates extended RNA spacers. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;44:7385–7394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Afroz T, Biliouris K, Kaznessis Y, et al. Bacterial sugar utilization gives rise to distinct single-cell behaviours. Mol Microbiol. 2014;93:1093–1103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.