ABSTRACT

Circular RNAs (circRNAs) belong to an endogenous class of RNA molecules with both ends covalently linked in a circle. Although their expression pattern in the mammalian brain has been well studied, the characteristics and functions of circRNAs in retinas remain unknown. To reveal the whole expression profiles of circRNAs in the neural retina, we investigated retinal RNAs of human, monkey, mouse, pig, zebrafish and tree shrew and detected thousands of circRNAs showing conservation and variation in the retinas across different vertebrate species. We further investigated one of the abundant circRNAs, circPDE4B, identified in human retina. Silencing of circPDE4B significantly inhibited the proliferation of human A549 cells. Functional assays demonstrated that circPDE4B could sponge miR-181C, thereby altering the cell phenotype. We have explored the retinal circRNA repertoires across human and different vertebrates, which provide new insights into the important role of circRNAs in the vertebrate retinas, as well as in related human diseases.

KEYWORDS: circular RNA, different vertebrate species, retina, circPDE4B, sponge

Introduction

Circular RNAs (circRNAs), represent a novel class of non-coding RNAs, characterized by covalently closed loop structures with no 5ʹ cap or 3ʹ polyadenylated tail. CircRNAs are expressed in a tissue-specific and developmental stage-specific manner and are involved in various physiological or pathological processes [1,2]. CircRNAs are remarkably enriched in the nervous system [3,4]. For example, in Drosophila, circRNAs were found to be highly and specifically expressed in the brain compared to non-neural tissues [5]; in mouse and human, hundreds of circRNAs accumulate in the brain and display high conservation of expression associated with neuronal differentiation [3]. Overall, many studies indicate an enrichment and thereby an important role of circRNAs in the central nervous system.

Retina is a neuronal tissue, which is a key part of the central nervous system. The retina is composed of different types of photoreceptors (rods and cones), which initiate phototransduction, and neurons forming complex neural circuitry. The retina is a vital light-sensitive tissue to produce clear vision. Although one group recently found that circRNAs might be involved in diabetic retinopathy (DR) which serve as biomarkers in DR diagnosis [6], and few other studies have investigated circRNAs in retina, it is still unknown whether circRNAs are also widely expressed in the retina of other species and how they contribute to the retinal function. To approach this unexplored issue, we systematically investigated the expression profiles of circRNAs in retinas across multiple species, especially in the human retina.

The structure of neural retina is similar in different species, from lower vertebrates (zebrafish) to human, typically referring to three layers of neural cells, including photoreceptor cells, bipolar cells, and ganglion cells, and a plus layer of retinal pigment epithelia. However, the composition of photoreceptor cells in these species is different. In zebrafish, four classes of cones lay out in a regular mosaic pattern, while the swine retina contains 10–20% cones of two types, with higher densities in the central streak [7]. The retina of the tree shrew (Tupaia belangeri) is also heavily cone-dominated at approximately 95% level [8], while only 3% cones exist in the murine retina [9]. The females of adult squirrel monkey strain Saimiri sciureus, have a trichromatic vision, with cones expressing M, L, and S-opsins [10] in the photoreceptor layer, which is very similar to the fovea located in human central retina containing exclusively cones. The similarities and differences between human and other vertebrate retinas prompted us to study circRNAs in retinas across different species.

In this study, we profiled circRNAs in retinas across six vertebrate species, including Homo sapiens, Macaca mulatta, Sus scrofa, Mus musculus, Tupaia belangeri, and Danio rerio by using transcriptome sequencing, and discovered thousands of circRNAs. We further characterized one new, abundant and conserved circPDE4B (has_circ_0008433) produced from the PDE4B gene. Previous studies have found that the PDE4B gene regulated synaptic transmission and was expressed in the inner and outer segments of rod photoreceptors [11,12]. However, the function of circPDE4B remained unknown. To investigate the regulatory role of circPDE4B, we performed a luciferase assay and found that circPDE4B can functionally sponge miR-181C and miR-423 and modulate cell proliferation in vitro. Taken together, this is the first systematic profiling of retinal circRNAs in human and five other vertebrate species, which provides new insights into the potential role of circRNAs in the physiological retina, as well as in related human retinal diseases.

Results

Complex expression patterns of retinal circRNAs in different species

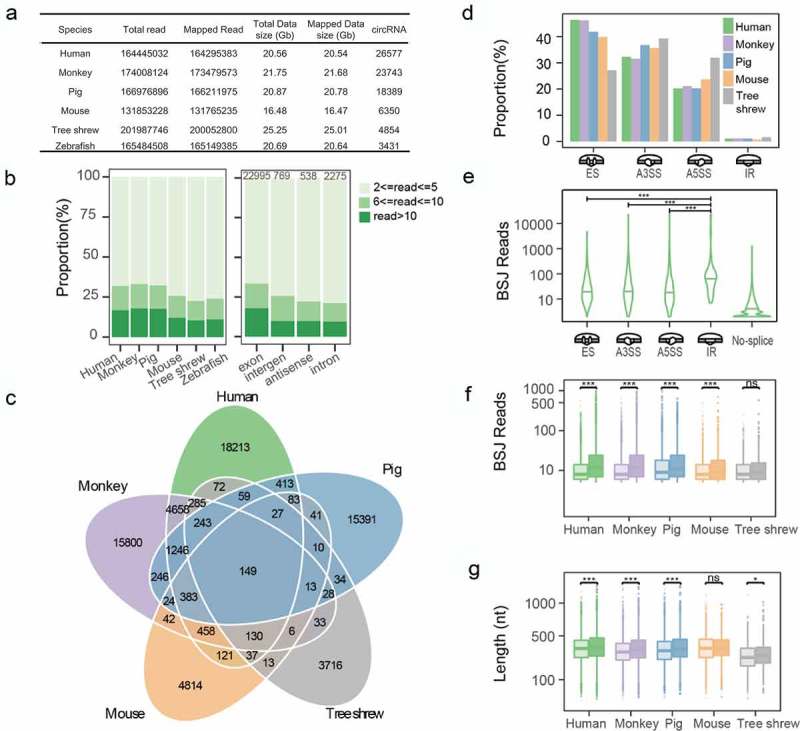

To systematically determine circRNA expression in retina, we constructed RNA libraries based on total RNA from retina samples of six species (Homo sapiens, Macaca mulatta, Sus scrofa, Mus musculus, Tupaia belangeri and Danio rerio), and generated 125.6 Gigabases (Gb) data for 1004.8 million reads in total (Figure 1(a)). Next, we characterized the expression abundance, type, length and conservation of circRNAs in these species. Approximately 99.74% of total-RNA-seq reads can be mapped to their reference genome by using Burrows-Wheeler Aligner (BWA-MEM) [13]. Then, we employed CIRI2 [14,15] to identify circRNAs from these datasets, and detected a total of 83,344 circRNAs with at least two back-spliced junctions (BSJ) reads support in six species, in which 16.40% of circRNAs have more than 10 BSJ reads (Figure 1(b)). After data normalization, we compared the abundance of circRNAs expressed in different species and found that retinas of human, monkey and pig (1293.91, 1095.16 and 884.94 circRNAs per Gb) tend to express more circRNAs than the other three species, ranging from 194.082 to 385.55 circRNAs per Gb (Supplementary Fig. S1). In human, a majority of circRNAs (86.52%) were exonic, and the remaining circRNAs could be classified into antisense (2.02%), intergenic (2.89%) and intronic (8.66%) types (Figure 1(b)). Similar findings were also observed in five other species (Supplementary Fig. S2). We further investigated the alternative splicing (AS) events that occurred in these circRNAs using the CIRI-AS pipeline. In order to get more reliable results, the circRNAs supported by least five BSJ reads were analyzed in this section. There are 1728 (16.87%, 1728/10,242), 1612 (17.11%, 1612/9420), 1056 (14.69%, 1056/7190), 240 (11.68%, 240/2055) and 133 (9.55%, 133/1393) in human, monkey, pig, mouse and tree shrew, respectively, that undergone at least one AS events (Supplementary Table1). In human, we detected 3592 AS events and the majority of them involve exon skipping (ES) (46.78%, 1,690/3,592). In addition, a small proportion of circRNAs have intron retention events, and notably, their expression levels are significantly higher than those of ES, A3SS and A5SS (Mann–Whitney test, p < 0.001) (Figure 1(d,e)).

Figure 1.

Classification and characterization of circRNAs. (a) Summary of RNA-seq data and identified circRNAs. (b) CircRNA abundance in six species (left) and their classifications in humans (right). (c) Venn diagram showing conserved circRNAs across the five species. (d) Percentage of different alternative splicing events in these species. (e) The abundance of circRNAs containing AS events in humans, in which IR-circRNAs have significantly higher expression levels than others (Mann–Whitney test). (f,g) The different significances were tested by Mann–Whitney test and labelled with * (p > 0.05 with ns, p < 0.05 with *, p < 0.01 with **, p < 0.001 with ***).

AS is regulated by splicing factors and RNA-binding proteins [16,17]. Studies have shown that the regulation mechanism of a regulatory factor between circRNA AS and linear transcript is different [18]. For instance, the AS factor Quaking (QKI), which regulates over one-third of abundant circRNAs by binding to the motif in the flanking region of BSJ sites [19], was significantly more enriched in skipped circRNA exons (cirexons) compared with skipped mRNA exons [18]. QKI was expressed in differentiating neurons, such as the horizontal and amacrine cells during the development of mouse retina, and subsequently in later differentiating bipolar cells, but not in photoreceptors [20]. And QKI was highly expressed in Müller glial cells in both developing and adult retinas. It suggested that the biogenesis and splicing of circRNA are unequal in the development stages of retina in different cell types.

To gain a comprehensive picture of the circRNA evolution, we determined the conservation of these circRNAs among the species. We found that 30.49% of circRNAs have orthologous companions in at least two species (Figure 1(c)). Then, we calculated the length and abundance for the circRNAs with BSJ reads ≥5. We found that the conserved circRNAs were extremely significantly more abundant compared with the species-specific circRNAs in human, monkey and pig and weakly significantly in tree shrew but in mouse (Figure 1(f), Supplementary Table.S2). Regarding the sequence length, conserved circRNAs are also extremely significantly longer than species-specific circRNAs in human, monkey, pig and mouse but in tree shrew (Figure1(g), Supplementary Table.S3). To test the distribution difference between conserved circRNAs and species-specific circRNAs, we plotted the overall distribution and found the distribution of conserved circRNAs was global higher than species-specific in human, monkey, pig and tree shrew (Supplementary Fig. S3). Low levels of circRNAs in mouse and tree shrew may reduce statistical power.

Then, circRNAs were classified into different categories according to photoreceptor cell associated host genes and further analysis was performed. The results showed that the expression levels of circRNAs from the same categories have no changes across different species (Supplementary Figs. S4 and S5), which means circRNAs are not the direct executor for retina function, on the other hand, as one of the epigenetic regulatory factors, it may be involved in functional regulation through the other mysterious ways, which needs to be further explored.

Characteristics of conserved circRNAs in human retina

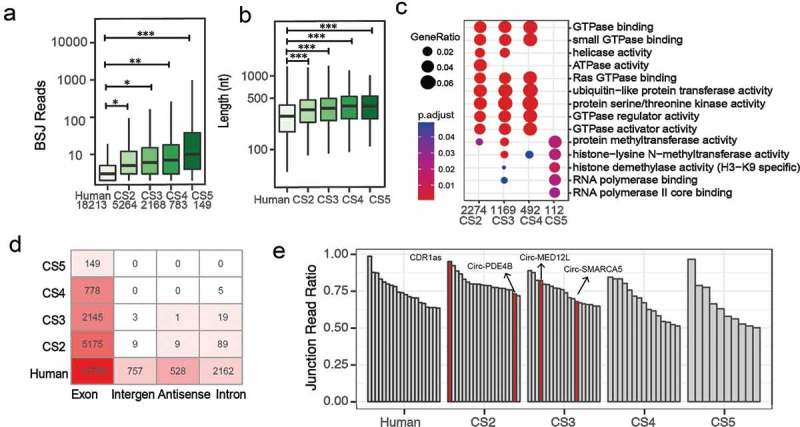

We placed circRNAs into different categories according to their conservation across different species, particularly human-specific and those conserved in two, three, four, or five species (CS2, CS3, CS4, and CS5, respectively). We found that with the stronger conservation, the average expression abundance tends to increase as well (Figure 2(a)). There is a similar trend in the circRNA length distribution (Figure 2(b)). Then, we performed the Gene Ontology enrichment analyses for the circRNA parental genes using the R-package clusterProfiler. Among four conserved circRNA categories, CS2, CS3 and CS4 are mostly associated with a wide range of metabolic pathways, including GTPase binding, GTPase regulator and activator activity, whereas CS5 is enriched in transcription and regulatory pathways (Figure 2(c)). By exploring circRNA types in different conserved categories, we found that the majority of conserved circRNAs have a linear transcript exon. Ten circRNAs originated from antisense strands are conserved in two or three species (Figure 2(d)). One of these 10 circRNAs, known as Cdr1as, has been demonstrated to function as a miR-7 sponge and play an important role in synaptic transmission [4,21,22]. We further prioritized all circRNAs based on their junction read ratio and expression abundance. To prioritize circRNAs with potential biological functions in the retina, we applied a strict threshold of the junction read ratio >0.5 and BSJ reads >100. In total, we obtained 160 circRNAs, with the top 20 in each category plotted in Figure 2(e). We identified some of those circRNAs in different classes of exon, antisense, intergenic and intronic types in human and mouse retina by qRT-PCR and Northern blotting (Supplementary Fig. S6 and S7). They are resistant to RNase R digestion (Supplementary Fig. S8). Some of these reported circRNAs are involved in a wide range of biological pathways, including CDR1as and circHIPK3 [21,23].

Figure 2.

Characteristics of conserved circRNAs in humans. (a) The expression abundance of circRNAs in different conservation categories. (b) Length distribution of conserved circRNAs. (c) Gene Ontology enrichment analysis of conserved circRNAs. (d) Classification of conserved circRNAs. (e) Top 20 circRNAs in each conservation category using a strict threshold of junction ratio >0.5 and BSJ reads >100. The different significances were tested by Mann–Whitney test and labelled with * (p > 0.05 with ns, p < 0.05 with *, p < 0.01 with **, p < 0.001 with ***).

Validation and characterization of human retinal circRNAs

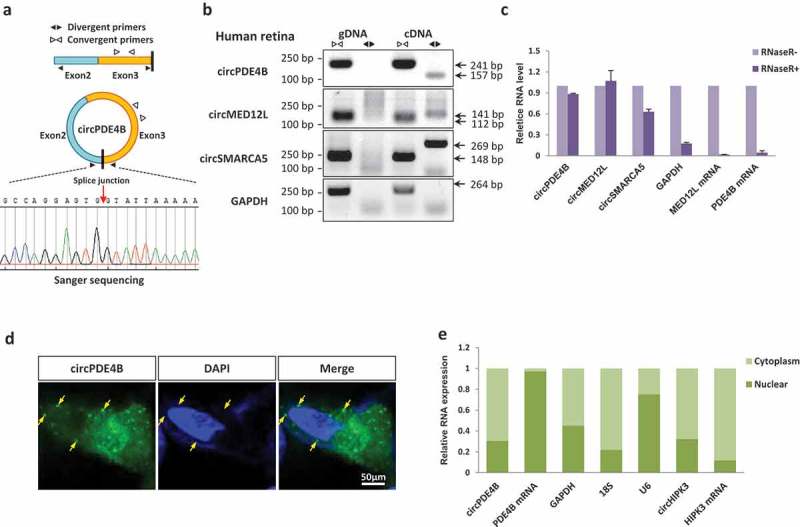

To validate the predicted circRNAs in human retina, circPDE4B, circMED12L and circSMARC5 were selected for further study. Each BSJ site was assayed by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) after reverse transcription with divergent primers and confirmed by Sanger sequencing. We further used one of the abundant human circRNA, circPDE4B, to exemplify the validation strategy. The PDE4B circular form was validated, and we noted that this circRNA is derived from Exon2 and Exon3 in the PDE4B gene (termed circPDE4B) (Figure 3(a)). We also confirmed other circRNAs in human retina by PCR (Figure 3(b) and Supplementary Fig. S9) and Sanger sequencing (Supplementary Fig. S10). These circRNAs, including circPDE4B, are resistant to RNase R exonuclease digestion, demonstrating that these RNAs are in a circular form (Figure 3(c)). In addition, circPDE4B is also abundant in human embryonic stem cell-derived retinal organoids during different differentiation stages, strongly indicating its abundance and important role during retinal development and function (Supplementary Fig. S11).

Figure 3.

Identification and characterization of circRNAs. (a) The expression of circPDE4B was validated by PCR followed by Sanger sequencing. (b) Verification that circPDE4B, circMED12L and circSMARCA5 are circRNAs, using divergent and convergent primers. GAPDH mRNA, negative control; gDNA, genomic DNA. (c) Real-time PCR showing the resistance of circPDE4B, circMED12L and circSMARCA5 to RNase R digestion. GAPDH, PDE4B and MED12L mRNAs are negative controls. (d) CircPDE4B is preferentially localized in the cytoplasm of A549 cell (yellow arrows; single-molecule RNA FISH; maximum intensity merges of Z-stacks). Green, circPDE4B; Blue, nuclei (DAPI); scale bar, 50 μm. (e) qRT-PCR data indicating the abundance of circPDE4B and PDE4B mRNA in either the cytoplasm or the nucleus of A549 cells. Data in (c,e) are the means ± SEM of three experiments.

We next tested the circPDE4B in vitro. Fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) for circPDE4B and qRT-PCR analysis of nuclear and cytoplasmic circPDE4B collectively demonstrated that the circular form of PDE4B was preferentially localized in the cytoplasm (Figure 3(d,e)). Taken together, these results confirmed the abundance of retinal circRNAs and suggest their potential biological roles in the human retina.

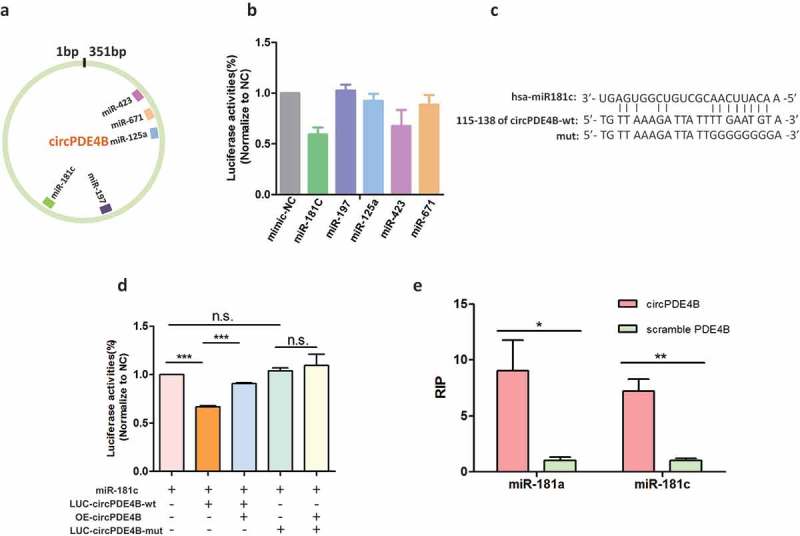

CircPDE4B serves as sponge for miR-181 clusters (miR-181C) and miR-423

CircRNAs have been known to act as microRNA (miRNA) sponges to regulate gene expression [4,24,25]. We, therefore, attempted to answer whether circPDE4B could bind to some miRNAs, which have been reported in human retina [26]. Using the computational prediction tool Regrna2.0, potential miRNAs associated with circPDE4B were identified (Figure 4(a)). Together with the previous report that miRNAs abundantly expressed in human retina [26], including miR-181 cluster (miR-181a/b/c/d, also referred to miR-181C), miR-197, miR-125, miR-423, miR-671, were further studied. We identified the target miRNAs binding to circPDE4B by using luciferase screening. We constructed a circPDE4B fragment and inserted it into downstream of psiCHECK-2 luciferase reporter gene to create LUC-circPDE4B vector, which was subsequently co-transfected with miRNA mimics or negative control (NC) into HEK-293D cells. Compared with the control, miR-181C and miR-423 significantly reduced the luciferase signals (Figure 4(b)). In contrast, no influence of luciferase signals by mutant the seed region of miR-181 in circPDE4B (Figure 4(c,d)). In addition, bioinformatics analysis found circPDE4B sponge to miR-181a/c, which was validated by pull-down analyses (Figure 4(e)). These results suggested that circPDE4B function as a sponge for miR-181C and miR-423.

Figure 4.

CircPDE4B function as sponges with miR-181C and miR-423. (a) Schematic illustration showing the putative binding sites of the miRNAs associated with circPDE4B. (b) Luciferase assay for the luciferase activity of LUC-circPDE4B in HEK293D cells co-transfected with miRNA mimics. (c) Sequence of circPDE4B was found to harbour a binding site for miR-181c. (d) Luciferase activity of circPDE4B containing wild-type putative miR-181c binding sites (circPDE4B-wt) or mutated sites (circPDE4B-mut). (e) The biotinylated miR-181a and miR-181c were transfected into A549 cells. The RNA levels of circPDE4B and scramble PDE4B were quantified by qRT-PCR analysis (n = 3; p > 0.05 with ns, p < 0.001 with ***).

CircPDE4B regulates cell proliferation by binding miR-181C

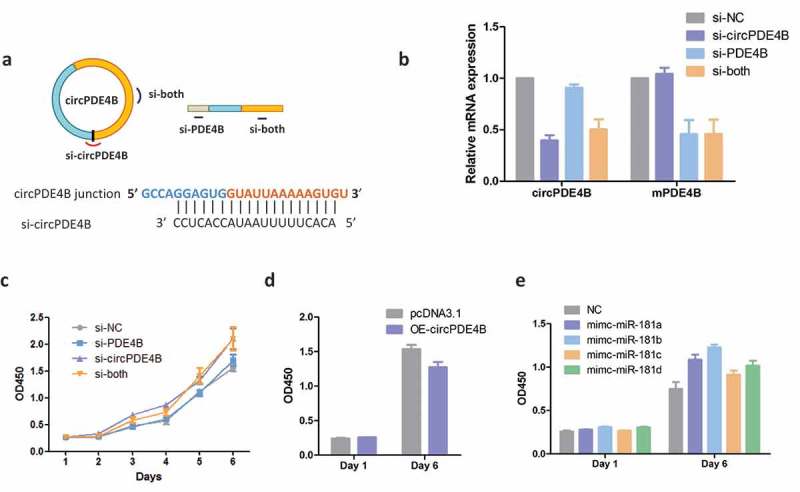

To unravel the biological roles of circPDE4B in vitro, three small interfering RNAs (siRNAs) were designed, including one siRNA targeting the back-spliced sequence circPDE4B (si-circPDE4B), one siRNA targeting the sequence that only exists in PDE4B linear transcript (si-PDE4B) and one siRNA targeting the sequence shared by circular and linear PDE4B (si-both) (Figure 5(a)). After the three siRNAs and NC control were transfected into HeLa cells, qRT-PCR results demonstrated that si-circPDE4B significantly reduced circPDE4B expression and that siRNA targeted to exonic sequences shared by both the linear and circular species effectively knocked down both transcripts (Figure 5(b)). Cell proliferation CCK8 assay revealed that si-circPDE4B, but not si-PDE4B, could increase the proliferation of A549 cells (Figure 5(c)). In contrast to the results above, the overexpression of circPDE4B in A549 cells reduced cell proliferation (Figure 5(d)).

Figure 5.

Silencing of circPDE4B promotes cell proliferation. (a) Schematic illustration showing three targeted siRNAs. Si-PDE4B targets the PDE4B linear transcript, si-circPDE4B targets the back-spliced junction (BSJ) of circPDE4B, and si-both targets both the linear and circular species. (b) qRT-PCR assay for circPDE4B and PDE4B mRNA expression after treatment with siRNAs. CCK8 assay for the proliferation of A549 after transfection with siRNAs (c), circPDE4B (d) and miR-181C mimics (e).

It has been reported that miRNAs, including miR-181c, sponged by circRNA could serve as a modulator of cell growth in human cells [27,28]. We, therefore, transfected individual miR-181C mimics into A549 cells to test if miR-181C could increase cell proliferation in vitro. The CCK8 assay revealed that miR-181C could promote cell growth, which is consistent with circPDE4B silencing in cells (Figure 5(c,e)). Taken together, these results indicate that circPDE4B can regulate cell proliferation by binding miR-181C.

Discussion

In this study, a comprehensive sequencing and analysis of circRNAs from six different species have revealed the high and conserved expression of circRNAs in the retina. Most well-expressed circRNAs in other species were also present in humans. Interestingly, our study suggests that human and monkey tends to express more circRNAs than the other four species, suggesting a species-specific manner of circRNA expression and the presence of useful features for evolutionary stability and variability. All diurnal monkeys and apes, as well as Homo sapiens, have an eye specialized for high-acuity daytime vision, and they have a high number of cones packing into the central retina in the fovea, which differs from other species [29,30]. It has been reported that the neuron-enriched circRNA expression possibly resulted from multiple layers of regulation, including transcription rate, RNA turnover and rate of cell division [31]. Therefore, whether these species-specific circRNAs are related to regulation of the formation of fovea needs further studies.

Many published studies have shown that animal genomes express thousands of circRNAs, with approximately 90% derived from exons [3]. Some of these circRNAs play critical roles in diverse biological processes, for example, circHIPK3, which derived from the HIPK3 gene exon2, can regulate cell growth by sponging multiple miRNAs [23]. CircANRIL, the predominant isoform consisting of exons 5, 6 and 7, modulates ribosomal RNA maturation and atherosclerosis in humans [32]. Our findings also showed that the majority of circRNAs (86.52%) in humans were exonic. We hypothesize that circPDE4B, which derived from exon2 and exon3 of the PDE4B gene, plays an essential role in human retina function.

CircRNAs have been shown to act as sponges that can regulate gene expression by binding miRNAs [23,33]. Cdr1as (also called ciRS-7) was found to contain 74 miR-7 binding sites, suggesting its dense binding capacity. Further studies showed that this circRNA effectively sponged miR-7 in zebrafish brains when ectopically expressed, causing a defect in midbrain development [4,21]. Removing the Cdr1as locus by CRISPR/Cas9 causes miRNA deregulation and affects brain function in mice [22]. In contrast to Cdr1as, circHIPK3 could serve as a modulator of cell growth by sponging multiple miRNAs in human cells and was significantly up-regulated in diabetic retinas [23,34]. CircANRIL modulates apoptosis and proliferation in human vascular cells and tissues, acting as a protective factor against human atherosclerosis [32]. In our study, we provided evidence that circPDE4B can act as a sponge by binding miR-181C and miR-423 in human cells. We also found that circPDE4B regulates cell growth by binding miR-181C. These results indicated that similar to other circRNAs discussed above, circPDE4B might also play an important role in regulating functions in the human retina. The miR-181 family is one of the most highly expressed miRNA families in many tissues, including the immune system.

Our study also showed that overexpression of miR-181C increased cell number. miR-181C is one of the most highly expressed miRNA families in many tissues, including the retina and immune system. MiR-181c (one of the miRNA in miR-181C) is known for its tissue specificity, with preferential expression in the retina and brain [35,36]. It has been reported that miR-181 is involved in metabolic regulation in the immune system [37]. It has also been revealed that miR-181c promotes proliferation via suppressing PTEN expression in inflammatory breast cancer. In addition, PDE4B gene is related to immune reaction, and inhibition of PDE4B suppresses inflammation [38]. Therefore, whether circPDE4B is also related to immune regulation in the retina is of interest and should be elucidated in further studies.

In conclusion, from the evolutionary point of view, our study provided a picture of conservation and variation of retinal circRNAs in various vertebrate species. The identification of RNA circularization in these species expands our understanding of their universal expression. We further characterized and functionally evaluated an abundant circRNA derived from the PDE4B gene and found that it can regulate cell proliferation by sponging miRNAs in human cells. Taken together, these lines of evidence reveal a new level of diversity in the circRNAs and their regulation in the human retina.

Methods

RNA extraction and sequencing

A study was conducted in accordance with the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki. Total RNA from a retina of each species was isolated using TRIZOL. A RiboMinus kit (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) was used to deplete ribosomal RNA. RNA samples were used as templates for cDNA libraries according to the TruSeq protocol (Illumina). These libraries were sequenced on the Illumina HiSeq 2500 platform with paired-end 125-bp reads in the Research Facility Center at Beijing Institutes of Life Science, CAS. For human retina and cell lines, cDNAs were reverse-transcribed into using random primers (Promega). The nuclear and cytoplasmic fractions were extracted using the PARIS Kit (Ambion) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Detection of circRNAs and their alternative splicing events from transcriptome data

Analyses in this study were performed on the genome data downloaded from Ensembl (http://asia.ensembl.org/info/data/ftp/index.html) of the GRCh37 primary assembly for human, MMUL 1.0 for a monkey, GRCm38 for mouse, Sscrofa10.2 for pig, tupBel1 for tree shrew and GRCz10 for zebrafish. The sequence of RNA-seq data was qualified and trimmed the low-quality bases with trim_galore (Version 0.4.4) (https://www.bioinformatics.babraham.ac.uk/projects/trim_galore/). Next, we detected BSJs in the RNA-seq reads using the CIRI2 circRNA identification pipeline with default parameters [14,15,39]. CIRI-AS [18] was used to determine AS events within circRNAs which were designed for circRNAs and more suitable than other tools [40–42]. The lengths of circRNAs were calculated based on cirexon predictions by CIRI-AS. The circRNAs supported by only one BSJ read were filtered out. Subsequently, a functional enrichment analysis for circRNA parental genes was performed using the R-package clusterProfiler [43]. The junction read ratio (JRR) is calculated for each identified circRNA in CIRI2 output results. In CIRI2, the JRR is calculated by the number of BSJ reads which across two BSJ sites (5ʹand 3’sites) and the number of non-BSJ reads which only across one back splicing site and the formula is:

Identifying orthologous circRNAs among multiple species

First, the species reference GTF files were used to determine the circRNA parental genes. Next, the circRNAs originated from the same orthologous gene downloaded from OMA orthology database (https://omabrowser.org) [44] were grouped. To determine their conservation, we extracted 50-bp fragments on both sides of the circRNA BSJ site from the reference genome and then concatenated both fragments to represent the circRNA sequence. All circRNA sequences in one species were aligned to those of other species using BLAT with the default parameters [13]. A pair of conserved circRNAs were defined based on their sequence alignment length≥80. Then, to select the overall best-conserved circRNAs among multiple species, all pairs of shared circRNAs were grouped for an iterative calculation of their sum identity alignment length among different species.

Northern blotting

Digoxin-labelled RNA probes were prepared with DIG Probe Synthesis Kit (Roche Applied Science, Indianapolis, IN, USA). The PCR primers were listed in Supplementary Table S4. 15 ug total RNA run on a 1% agarose gel and transferred to a Hybond-Nt membrane (GE Healthcare, Uppsala, Sweden) by capillary transfer. Membranes were dried and UV-cross-linked using standard manufacturer’s protocol. Membranes were then hybridized with specific Dig-labelled RNA probes. Pre-hybridization was done at 50°C for 2 hours and hybridization was performed at 50°C overnight. The membranes were washed briefly in 2× SSC, 0.1% SDS at room temperature and two additional times at 68°C for 30 min. After washing, the blot was visualized by X-ray film.

RNase R treatment

Human retina DNase-treated total RNA (5 μg) was incubated for 30 min at 37°C with or without 3 U μg−1 of RNase R (Epicentre Biotechnologies). RNA was subsequently purified by RNeasy MinElute cleaning Kit (Qiagen), reverse-transcribed through Superscript SSIII (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer’s protocol, and used in qRT-PCR.

PCR and qRT-PCR

PCR reactions for amplification of circRNAs were performed on cDNA from human retina, HEK293D, A549, and HeLa cells, with divergent primers (Supplementary Table S4). PCR products were cloned into a pGEM-T vector (Promega) and sequenced with the Illumina HiSeq 2000 platform [36]. Full length of circPDE4B was cloned into pHB-circBasicTM (Hanbio Biotechnology Co., Ltd.). The samples of cDNA were used for quantitative PCR in a real-time PCR system (7500 Fast Real-Time PCR System; Roche) using a FastStart Universal SYBR Green Master (Rox) (Roche Applied Science). In particular, the divergent primers annealing at the distal ends of circRNA were used to determine the abundance of circRNA. Primer sequences specific to the genes of interest are listed in Supplementary Table S4.

RNA FISH

The expression of circPDE4B in A549 cells was detected by fluorescence in situ hybridization. The cDNA probe was 5ʹ- CACTTTTTAATACCACTCCTGGCTTA-3ʹ labelled by 6-FAM (BersinBio). The fluorescence in situ hybridization was then carried out according to the instruction of the FISH Detection Kit (BersinBio). Imaging was performed using a confocal microscope equipped with the vision software.

Statistical analysis

Data were presented as the mean±SEM. The graphic pictures and statistical significance of the findings were determined via ANOVA (unpaired t-test) using the statistical software GraphPad Prism 5 (GraphPad Software, Inc., La Jolla, CA, USA).

Cell culture and transfection

HEK293D, A549 and HeLa cells were employed in this study and cultured in DMEM (Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium) supplemented with 10% FBS (Fetal Bovine Serum) and 1% PS (penicillin-streptomycin) solution. SiRNAs and miRNA mimics were synthesized by Ribobio company (Guangzhou, China) and transfected into cells using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. After 6-hour incubation, transfection media (Opti-MEM) was replaced with normal media (DMEM with 2% FBS) and incubated for 24 to 48 hours, and cells were then collected for further studies.

CCK8 assay

The cell proliferation was tested by CCK8 kit. A549 and HeLa cells (2 × 103) were seeded in 96-well plates for transfection with si-circPDE4B, si-PDE4B, si-both or NC control. After 24, 48, 72, 96 and 120-hour incubation, the CCK8 reagent was added at 37°C and after incubation for another 1 hour, the absorbance was determined at 490 nm wavelength using a microplate reader.

Luciferase assay

Dual-luciferase reporter plasmid psi-CHECK2 was used to identify the miRNA which acts as a sponge of circPDE4B. The entire circPDE4B sequence was cloned downstream of the luciferase to create LUC-circPDE4B. LUC-circPDE4B-wt, LUC-circPDE4B-mut and the mimic-miRNA NC control were co-transfected into HEK293D cell. Firefly and Renilla substrate was added after 24-hour incubation, and corresponding luminescence was measured, respectively, using a microplate spectrophotometer.

Biotin-oligo pull-down of RNA

CircPDE4B was cloning into a pHB-circBasic vector and overexpressed in A549 cell. Cells were collected and lysed in cell lysis buffer A after 48 hours’ transfection. Two times volume of hybridization buffer (750 mM NaCl, 1% SDS, 50 mM Tris-Cl, pH 7.0, 1 mM EDTA, 15% formamide) and Biotin-circPDE4B/Biotin-linear PDE4B oligos (100 pmol) were added. The mixture was mixed well and incubated at 37°C for 4 hours hybridization. Prepare beads in the last 1 hour of hybridization: 100 µl Streptavidin Dynabeads (Life Technologies) were washed in cell lysis buffer, then blocked with 500 ng/µl yeast total RNA and 1 mg/ml BSA for 1 hour at room temperature, and washed three times in cell lysis buffer. Washed beads were mixed with the above mixture and rotated for 30 min at 37°C. Then beads were washed five times with wash buffer (2× SSC, 0.5% SDS). Beads were then subjected to RNA isolation, Biotin scrambled oligo was used as negative control. MiR-181a/c was then quantified using qRT-PCR.

Funding Statement

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81870690), National Key R & D Program of China (2017YFB0403700, 2017YFA0105300), National Natural Science Foundation of China (81790644, 81522014, 81500741), National Key R & D Program of China, Zhejiang Provincial Natural Science Foundation of China (LD18H120001), Zhejiang Provincial Key Research and Development Program (2015C03029), 111 project (D16011), Wenzhou Science and Technology Innovation Team Project (C20150004); National Natural Science Foundation of China [81790644]; National Natural Science Foundation of China [81500741]; National Natural Science Foundation of China [81870690]; National Natural Science Foundation of China [81522014]; 111 project [D16011]; Zhejiang Provincial Key Research and Development Program [2015C03029]; Wenzhou Science and Technology Innovation Team Project [C20150004]; National Key R & D Program of China [2017YFB0403700]; Agro-Industry R and D Special Fund of China (CN) [2017YFA0105300]; Zhejiang Provincial Natural Science Foundation of China [LD18H120001].

Acknowledgments

The authors thank all individuals examined and tested in the investigation.

Disclosure of potential conflicts of interest

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed on the publisher’s website.

References

- [1].Cortes-Lopez M, Miura P.. Emerging functions of circular RNAs. Yale J Biol Med. 2016;89:527–537. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Liu J, Liu T, Wang X, et al. Circles reshaping the RNA world: from waste to treasure. Mol Cancer. 2017;16:58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Rybak-Wolf A, Stottmeister C, Glazar P, et al. Circular RNAs in the Mammalian brain are highly abundant, conserved, and dynamically expressed. Mol Cell. 2015;58:870–885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Hansen TB, Jensen TI, Clausen BH, et al. Natural RNA circles function as efficient microRNA sponges. Nature. 2013;495:384–388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Westholm JO, Miura P, Olson S, et al. Genome-wide analysis of drosophila circular RNAs reveals their structural and sequence properties and age-dependent neural accumulation. Cell Rep. 2014;9:1966–1980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Zhang SJ, Chen X, Li CP, et al. Identification and characterization of circular RNAs as a new class of putative biomarkers in diabetes retinopathy. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2017;58:6500–6509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Hendrickson A, Hicks D. Distribution and density of medium- and short-wavelength selective cones in the domestic pig retina. Exp Eye Res. 2002;74:435–444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Muller B, Peichl L. Topography of cones and rods in the tree shrew retina. J Comp Neurol. 1989;282:581–594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Wang YV, Weick M, Demb JB. Spectral and temporal sensitivity of cone-mediated responses in mouse retinal ganglion cells. J Neurosci. 2011;31:7670–7681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Mancuso K, Hauswirth WW, Li Q, et al. Gene therapy for red-green colour blindness in adult primates. Nature. 2009;461:784–787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Whitaker CM, Cooper NG. The novel distribution of phosphodiesterase-4 subtypes within the rat retina. Neuroscience. 2009;163:1277–1291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Dong CJ, Guo Y, Ye Y, et al. Presynaptic inhibition by alpha2 receptor/adenylate cyclase/PDE4 complex at retinal rod bipolar synapse. J Neurosci. 2014;34:9432–9440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Kent WJ. BLAT–the BLAST-like alignment tool. Genome Res. 2002;12:656–664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Gao Y, Zhang J, Zhao F. Circular RNA identification based on multiple seed matching. Brief Bioinform. 2018;19:803–810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Gao Y, Wang J, Zhao F. CIRI: an efficient and unbiased algorithm for de novo circular RNA identification. Genome Biol. 2015;16:4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Fu XD, Ares M Jr.. Context-dependent control of alternative splicing by RNA-binding proteins. Nat Rev Genet. 2014;15:689–701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Mcmanus CJ, Graveley BR. RNA structure and the mechanisms of alternative splicing. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2011;21:373–379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Gao Y, Wang J, Zheng Y, et al. Comprehensive identification of internal structure and alternative splicing events in circular RNAs. Nat Commun. 2016;7:12060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Conn SJ, Pillman KA, Toubia J, et al. The RNA binding protein quaking regulates formation of circRNAs. Cell. 2015;160:1125–1134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Suiko T, Kobayashi K, Aono K, et al. Expression of quaking RNA-binding protein in the adult and developing mouse retina. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0156033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Memczak S, Jens M, Elefsinioti A, et al. Circular RNAs are a large class of animal RNAs with regulatory potency. Nature. 2013;495:333–338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Piwecka M, Glazar P, Hernandez-Miranda LR, et al. Loss of a mammalian circular RNA locus causes miRNA deregulation and affects brain function. Science. 2017;357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Zheng Q, Bao C, Guo W, et al. Circular RNA profiling reveals an abundant circHIPK3 that regulates cell growth by sponging multiple miRNAs. Nat Commun. 2016;7:11215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Jeck WR, Sharpless NE. Detecting and characterizing circular RNAs. Nat Biotechnol. 2014;32:453–461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Lasda E, Parker R. Circular RNAs: diversity of form and function. Rna. 2014;20:1829–1842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Karali M, Persico M, Mutarelli M, et al. High-resolution analysis of the human retina miRNome reveals isomiR variations and novel microRNAs. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;44:1525–1540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Zhang HT, Huang Y, Masood A, et al. Anxiogenic-like behavioral phenotype of mice deficient in phosphodiesterase 4B (PDE4B). Neuropsychopharmacology. 2008;33:1611–1623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Li Y, Wang H, Li J, et al. MiR-181c modulates the proliferation, migration, and invasion of neuroblastoma cells by targeting Smad7. Acta Biochim Biophys Sin (Shanghai). 2014;46:48–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Lc S. Comparative study of the primate retina Primate Visual Syst. 2004;1:29–51. [Google Scholar]

- [30].Heesy CP, Ross CF. Evolution of activity patterns and chromatic vision in primates: morphometrics, genetics and cladistics. J Hum Evol. 2001;40:111–149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Zhang Y, Xue W, Li X, et al. The biogenesis of nascent circular RNAs. Cell Rep. 2016;15:611–624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Holdt LM, Stahringer A, Sass K, et al. Circular non-coding RNA ANRIL modulates ribosomal RNA maturation and atherosclerosis in humans. Nat Commun. 2016;7:12429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Du WW, Yang W, Liu E, et al. Foxo3 circular RNA retards cell cycle progression via forming ternary complexes with p21 and CDK2. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;44:2846–2858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Shan K, Liu C, Liu BH, et al. Circular noncoding RNA HIPK3 mediates retinal vascular dysfunction in diabetes mellitus. Circulation. 2017;136:1629–1642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Wang HC, Greene WA, Kaini RR, et al. Profiling the microRNA expression in human iPS and iPS-derived retinal pigment epithelium. Cancer Inform. 2014;13:25–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Zhang WL, Zhang JH. miR-181c promotes proliferation via suppressing PTEN expression in inflammatory breast cancer. Int J Oncol. 2015;46:2011–2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Williams A, Henao-Mejia J, Harman CC, et al. miR-181 and metabolic regulation in the immune system. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol. 2013;78:223–230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Komatsu K, Lee JY, Miyata M, et al. Inhibition of PDE4B suppresses inflammation by increasing expression of the deubiquitinase CYLD. Nat Commun. 2013;4:1684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Gao Y, Zhao F. Computational strategies for exploring circular RNAs. Trends Genet. 2018;34:389–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Liu Q, Chen C, Shen E, et al. Detection, annotation and visualization of alternative splicing from RNA-Seq data with splicingviewer. Genomics. 2012;99:178–182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Huang S, Zhang J, Li R, et al. SOAPsplice: genome-wide ab initio detection of splice junctions from RNA-seq data. Front Genet. 2011;2:46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Wang K, Singh D, Zeng Z, et al. MapSplice: accurate mapping of RNA-seq reads for splice junction discovery. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:e178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Yu G, Wang LG, Han Y, et al. clusterProfiler: an R package for comparing biological themes among gene clusters. OMICS. 2012;16:284–287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Altenhoff AM, Skunca N, Glover N, et al. The OMA orthology database in 2015: function predictions, better plant support, synteny view and other improvements. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43:D240–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.