Abstract

Background

Anxiety frequently coexists with depression and adding benzodiazepines to antidepressant treatment is common practice to treat people with major depression. However, more evidence is needed to determine whether this combined treatment is more effective and not any more harmful than antidepressants alone. It has been suggested that benzodiazepines may lose their efficacy with long‐term administration and their chronic use carries risks of dependence.

This is the 2019 updated version of a Cochrane Review first published in 2001, and previously updated in 2005. This update follows a new protocol to conform with the most recent Cochrane methodology guidelines, with the inclusion of 'Summary of findings' tables and GRADE evaluations for quality of evidence.

Objectives

To assess the effects of combining antidepressants with benzodiazepines compared with antidepressants alone for major depression in adults.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Common Mental Disorders Group's Controlled Trials Register (CCMDCTR), the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, MEDLINE, Embase and PsycINFO to May 2019. We searched the World Health Organization (WHO) trials portal and ClinicalTrials.gov to identify any additional unpublished or ongoing studies.

Selection criteria

All randomised controlled trials that compared combined antidepressant plus benzodiazepine treatment with antidepressants alone for adults with major depression. We excluded studies administering psychosocial therapies targeted at depression and anxiety disorders concurrently. Antidepressants had to be prescribed, on average, at or above the minimum effective dose as presented by Hansen 2009 or according to the North American or European regulations. The combination therapy had to last at least four weeks.

Data collection and analysis

Two review authors independently extracted data and assessed risk of bias in the included studies, according to the criteria of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. We entered data into Review Manager 5. We used intention‐to‐treat data. We combined continuous outcome variables of depressive and anxiety severity using standardised mean differences (SMD) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). For dichotomous efficacy outcomes, we calculated the risk ratio (RR) with 95% CI. Regarding the primary outcome of acceptability, only overall dropout rates were available for all studies.

Main results

We identified 10 studies published between 1978 to 2002 involving 731 participants. Six studies used tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs), two studies used selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), one study used another heterocyclic antidepressant and one study used TCA or heterocyclic antidepressant.

Combined therapy of benzodiazepines plus antidepressants was more effective than antidepressants alone for depressive severity in the early phase (four weeks) (SMD –0.25, 95% CI –0.46 to –0.03; 10 studies, 598 participants; moderate‐quality evidence), but there was no difference between treatments in the acute phase (five to 12 weeks) (SMD –0.18, 95% CI –0.40 to 0.03; 7 studies, 347 participants; low‐quality evidence) or in the continuous phase (more than 12 weeks) (SMD –0.21, 95% CI –0.76 to 0.35; 1 study, 50 participants; low‐quality evidence). For acceptability of treatment, there was no difference in the dropouts due to any reason between combined therapy and antidepressants alone (RR 0.76, 95% CI 0.54 to 1.07; 10 studies, 731 participants; moderate‐quality evidence).

For response in depression, combined therapy was more effective than antidepressants alone in the early phase (RR 1.34, 95% CI 1.13 to 1.58; 10 studies, 731 participants), but there was no evidence of a difference in the acute phase (RR 1.12, 95% CI 0.93 to 1.35; 7 studies, 383 participants) or in the continuous phase (RR 0.97, 95% CI 0.73 to 1.29; 1 study, 52 participants). For remission in depression, combined therapy was more effective than antidepressants alone in the early phase (RR 1.39, 95% CI 1.03 to 1.90, 10 studies, 731 participants), but there was no evidence of a difference in the acute phase (RR 1.27, 95% CI 0.99 to 1.63; 7 studies, 383 participants) or in the continuous phase (RR 1.31, 95% CI 0.80 to 2.16; 1 study, 52 participants). There was no evidence of a difference between combined therapy and antidepressants alone for anxiety severity in the early phase (SMD –0.76, 95% CI –1.67 to 0.14; 3 studies, 129 participants) or in the acute phase (SMD –0.48, 95% CI –1.06 to 0.10; 3 studies, 129 participants). No studies measured severity of insomnia. In terms of adverse effects, the dropout rates due to adverse events were lower for combined therapy than for antidepressants alone (RR 0.54, 95% CI 0.32 to 0.90; 10 studies, 731 participants; moderate‐quality evidence). However, participants in the combined therapy group reported at least one adverse effect more often than participants who received antidepressants alone (RR 1.12, 95% CI 1.01 to 1.23; 7 studies, 510 participants; moderate‐quality evidence).

Most domains of risk of bias in the majority of the included studies were unclear. Random sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding and selective outcome reporting were problematic due to insufficient details reported in most of the included studies and lack of availability of the study protocols. The greatest limitation in the quality of evidence was issues with attrition.

Authors' conclusions

Combined antidepressant plus benzodiazepine therapy was more effective than antidepressants alone in improving depression severity, response in depression and remission in depression in the early phase. However, these effects were not maintained in the acute or the continuous phase. Combined therapy resulted in fewer dropouts due to adverse events than antidepressants alone, but combined therapy was associated with a greater proportion of participants reporting at least one adverse effect.

The moderate quality evidence of benefits of adding a benzodiazepine to an antidepressant in the early phase must be balanced judiciously against possible harms and consideration given to other alternative treatment strategies when antidepressant monotherapy may be considered inadequate. We need long‐term, pragmatic randomised controlled trials to compare combination therapy against the monotherapy of antidepressant in major depression.

Plain language summary

Antidepressants plus benzodiazepines for major depression

Why is this review important?

Major depression is characterised by depressed mood, loss of interest or pleasure, diminished energy, fatigue, difficulties with concentration, changes in appetite, sleep disturbances and morbid thoughts of death. Depression often presents with anxiety. Depression and anxiety have negative impacts on the person and on society, often over the long term.

Who will be interested in this review?

Health professionals, including general practitioners and psychiatrists; people with major depression and the people around them.

What question does this review aim to answer?

Major depression is often treated by combining antidepressant drugs with benzodiazepines. Benzodiazepines are a family of anxiety‐reducing and hypnotic drugs. This review asked if combined antidepressant plus benzodiazepine treatment, compared with antidepressants treatment alone, had an effect on depressive symptoms, rates of recovery and the acceptability of these treatments based on the number of people who left the study early (called the dropout rate), in adults with major depression.

Which studies were included in the review?

We searched electronic databases to find all relevant studies in adults with major depression. To be included, the studies had to be randomised controlled trials (RCTs), which means adults were allocated at random (by chance alone) to receive either antidepressants plus benzodiazepines or antidepressants alone (last search date 23 May 2019).

We found 10 relevant studies involving 731 people comparing combined antidepressant plus benzodiazepine therapy with treatment with antidepressants alone. The quality of the evidence ranged from very low to moderate.

What does the evidence from the review tell us?

Combining antidepressants and benzodiazepines was more effective than antidepressants alone in improving depression and reducing symptoms in the early phase of treatment (one to four weeks), but there was no evidence of a difference at later time points. There was no evidence of a difference in acceptability (based on dropouts) between the combination treatment compared with antidepressants alone. Dropout rates due to unintended and untoward effects (side effects) were lower for antidepressants plus benzodiazepines compared with antidepressants alone, although at least one side effect was reported more frequently by those treated with a combination of antidepressants plus benzodiazepines.

What should happen next?

Due to the potential for people to become dependent on benzodiazepines, new longer‐term studies need to compare what happens when the combined treatment involves withdrawing the benzodiazepine after a short period (for example, one month).

Summary of findings

Summary of findings for the main comparison. Antidepressants plus benzodiazepines compared to antidepressants alone for major depression in adults.

| Antidepressants plus benzodiazepines compared to antidepressants alone for major depression in adults | ||||||

| Patient or population: people with major depression Setting: inpatients and outpatients Intervention: antidepressants + benzodiazepines Comparison: antidepressants alone | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with antidepressants alone | Risk with antidepressants plus benzodiazepines | |||||

| Depression severity: early phase (2 weeks, range 1–4 weeks) Follow‐up: range 1–4 weeks | — | The mean depression severity in the early phase in the combination group was 0.25 standard deviations lower (0.46 lower to 0.03 lower). | — | 598 (10 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderatea | — |

| Depression severity: acute phase (8 weeks, range 5–12 weeks) | — | The mean depression severity in the acute phase in the combination group was 0.18 standard deviations lower (0.40 lower to 0.03 higher). | — | 347 (7 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowa,b | — |

| Depression severity: continuous phase (> 12 weeks) | — | The mean depression severity in the continuous phase in the combination groups was 0.21 standard deviations lower (0.76 lower to 0.35 higher) | — | 50 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowa,b | — |

| Acceptability of treatment (dropout for any reason) | Study population | RR 0.76 (0.54 to 1.07) | 731 (10 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderatea | — | |

| 332 per 1000 | 253 per 1000 (180 to 356) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| 200 per 1000 | 152 per 1000 (108 to 214) | |||||

| Anxiety severity: early phase (2 weeks, range 1–4 weeks) | — | The mean depression severity in early phase in the combination groups was 0.76 standard deviations lower (1.67 lower to 0.14 higher) | — | 129 (3 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowa,b, c | — |

| Adverse effects (dropouts) | Study population | RR 0.54 (0.32 to 0.90) | 731 (10 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderatea | — | |

| 119 per 1000 | 64 per 1000 (38 to 107) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| 85 per 1000 | 46 per 1000 (27 to 77) | |||||

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; OR: odds ratio; RR: risk ratio. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate quality: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low quality: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low quality: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | ||||||

aWe downgraded the evidence by one level because of risk of bias. Studies were described as "double‐blind", but information on the procedure followed to guarantee the blindness, and if blinding was successful, was not reported in all randomised controlled trials. Also, information on randomisation procedures and allocation concealment was lacking in all studies. Moreover, half of the included studies had high attrition rate. bWe downgraded the evidence by one level because of low number of participants included in the analysis and 95% confidence interval included both no effect and appreciable benefit. cWe downgraded the evidence by one level because of high heterogeneity between studies.

Background

Description of the condition

Major depression is characterised by depressed mood, loss of interest or pleasure, diminished energy, fatigue, difficulties with concentration, changes in appetite, sleep disturbances and morbid thoughts of death (APA 2013). Depression is a common disorder with a lifetime prevalence of 16% (Kessler 2003), and 12‐month prevalence rate between 6% and 10% (Baumeister 2007). As the largest source of non‐fatal disease burden in the world, accounting for 12% of years lived with disability (Ustun 2004), depression is associated with marked personal, social and economic morbidity, loss of functioning and productivity; and creates significant demands on service providers in terms of workload (NICE 2009). Depression often presents with anxiety. The rate of anxiety comorbidity among people with depression varies between 33% and 85% (Murphy 1990; Wetzler 1989), is associated with a higher familial prevalence of major depression (Clayton 1991; Coryell 1992), and its presence may predict a poorer long‐term outcome.

Description of the intervention

Benzodiazepines refer to a class of psychotropic drugs whose core chemical structure is the fusion of a benzene and diazepine ring. They are mainly used for people with anxiety symptoms (anxiolytics, tranquillisers) and as hypnotic drugs for people with insomnia.

When treating people with major depression, the current guidelines recommend antidepressant monotherapy as first‐line pharmacological treatment (APA 2010; BAP 2015; Bauer 2002; NICE 2009). Some guidelines state a limited value of benzodiazepines as combination therapy and allow that benzodiazepines can be used for a short time with an antidepressant if people have symptoms of anxiety or insomnia (APA 2010; BAP 2015; NICE 2009). The WFSBP guidelines acknowledge the quick onset of action of benzodiazepines in treating agitation, anxiety and insomnia (Bauer 2002).

However, the APA guideline does not recommend benzodiazepines as primary pharmacological agents even in people with major depression with anxiety symptoms, because of the known adverse effects and toxicity profile associated with these drugs, as well as the potential for abuse and dependence (APA 2010). Some guidelines also explicitly state that benzodiazepines do not have an antidepressant effect (APA 2010; NICE 2009). In addition there are suggestions that benzodiazepines may lose their efficacy with long‐term administration (CRM 1980), and that their chronic use carries risks of dependence (Schweizer 1998).

In reality, combination prescriptions appear to be common in many parts of the world. For example, one multi‐centre study in Japan found that approximately 60% of psychiatric patients making their first presentation for treatment in a psychiatric service with major depression were prescribed benzodiazepines (excluding those used as hypnotics) in addition to antidepressants (Furukawa 2000). In Canada, the prevalence of antidepressants and benzodiazepines utilisation was 49.3% of people who had experienced an major depressive episode in the past 12 months and reported antidepressant use (Sanyal 2011). The older people tended to receive more benzodiazepines than the younger patients among Health Maintenance Organization patients with depression (49% with older and 33% with younger) (Bartels 1997). In another study, primary care physicians prescribed antidepressants to 56% of their patients diagnosed as depressed; of these, 16% were also prescribed benzodiazepines (Olfson 1992). In one survey of primary care practices in the Netherlands, 5% of the people presenting with depression and anxiety received an antidepressant only, 16% received an anxiolytic only and 5% received a combination of antidepressant and anxiolytic (van den Brink 1991). In France, a general population survey revealed that slightly less than two thirds of antidepressant users were also prescribed benzodiazepines (anxiolytic or hypnotic) concomitantly (Bouhassira 1998). At one university psychiatric clinic in Germany, monotherapy was applied in only 37% of all cases, and a combined psychopharmacotherapy in 63% of cases (Grohmann 1980). In Italy, among 281 cases treated in acute psychiatric inpatient services, only two people were prescribed an antidepressant alone while 44 received a combination of benzodiazepine plus antidepressant (de Girolamo 1987).

How the intervention might work

Benzodiazepines act through binding at, and enhancing the effect of, gamma‐aminobutyric acid (GABA)‐A receptors. Enhancement of the effect of GABA at this receptor results in sedative, anxiolytic, hypnotic and muscle relaxant properties. Combining benzodiazepines with antidepressants may lead to additive or synergistic antidepressant effect if benzodiazepines themselves have an antidepressant effect (Gomez 2000; Petty 1995), or if they act on anxiety or insomnia often comorbid with major depression.

Why it is important to do this review

Reviews of randomised controlled trials (RCTs) show that anxiolytic benzodiazepines, with the possible exception of some triazolo‐benzodiazepines for mild‐to‐moderate depression, are less effective than standard antidepressants in treating major depression (Birkenhager 1995; Schatzberg 1978). The advantages of adding benzodiazepines to antidepressants are unclear. There have been several RCTs examining the combined antidepressant plus benzodiazepine treatment in depression but the results vary (Birkenhager 1995). The first version of this systematic review was published in 2002 (with a literature searched up to 1999). The first major updated version was published in 2005 (with literature searched up to 2004). This is the second major update of this review (with literature searched up to May 2019). This update followed a revised protocol to conform with the latest edition of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011), and to provide 'Summary of findings' tables.

Objectives

Primary objective

To assess the effects of combining antidepressants with benzodiazepines compared with antidepressants alone for major depression in adults.

Secondary objectives

To determine if additional benzodiazepines benefit people with depression with high anxiety or low anxiety, and if short‐acting benzodiazepines given at bedtime influence daytime mood.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

All relevant RCTs meeting the inclusion criteria, including cluster randomised trials. We used only the first phase of cross‐over studies.

Types of participants

Participants

Adults (aged 18 years or older), with no restrictions in terms of gender or ethnicity.

Diagnosis

Major depression, diagnosed according to any one of the Feighner criteria, the Research Diagnostic Criteria (RDC), the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual 3rd Edition (DSM‐III), 3rd Revised Edition (DSM‐III‐R), 4th Edition (DSM‐IV), 5th Edition (DSM‐5) or the 10th Revision of the International Classification of Diseases (ICD‐10).

Comorbidities

We included studies where participants had comorbid anxiety disorders. Studies involving participants with comorbid physical or other psychological disorders were eligible for inclusion, as long as the comorbidity was not the focus of the study.

Setting

We assigned no restrictions to the type of study setting.

Types of interventions

Experimental intervention

Any combination of antidepressants and benzodiazepines. We excluded studies administering psychosocial therapies targeted at depression and anxiety disorders concurrently. Antidepressants had to be prescribed, on average, at or above the minimum effective dose as presented by Hansen and colleagues (Hansen 2009), or according to the North American (APA 2010) or European regulations. The benzodiazepines had to be prescribed in accordance with the North American (APA 2010) or European regulations. The combination therapy had to last at least four weeks.

We included the following types of antidepressants.

Tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs): amitriptyline, imipramine, trimipramine, doxepin, desipramine, protriptyline, nortriptyline, clomipramine, dothiepin, iofepramine.

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs): zimelidine (banned worlwide due to a 25‐fold increase in the risk of developing Guillain‐Barré syndrome (Fagius 1985)), fluvoxamine, fluoxetine, paroxetine, sertraline, citalopram, escitalopram.

Serotonin‐noradrenaline reuptake inhibitors: venlafaxine, milnacipran, duloxetine.

Noradrenergic and specific serotonergic antidepressants: mirtazapine.

-

Monoamine oxidase inhibitors:

irreversible: phenelzine, tranylcipromine, izocarboxazid;

reversible: brofaramine, moclobemide, tyrima.

Other antidepressants:

noradrenaline reuptake inhibitors: reboxetine, atomoxetine;

noradrenaline‐dopamine reuptake inhibitors: amineptine, bupropion;

serotonin antagonist and reuptake inhibitors: trazodone;

unclassified: agomelatine, vilazodone;

other heterocyclic antidepressants: mianserin, amoxapine, maprotiline.

For benzodiazepines, we included the following: adinazolam, alprazolam, bentazepam, bromazepam, brotizolam, camazepam, chlordiazepoxide, clobazam, clonazepam, clorazepate, clotiazepam, cloxazolam, diazepam, estazolam, etizolam, flunitrazepam, flurazepam, flutoprazepam, halazepam, ketazolam, loflazepate, lorazepam lormetazepam, medazepam, metaclazepam, mexazolam, midazolam, nitrazepam, nordazepam, oxazepam, prazepam, propazepam, quazepam, ripazepam, serazepine, temazepam, tofisopam, triazolam.

Control intervention

Antidepressants alone.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Depressive severity: studies had to include at least one measure of depressive severity. The symptom severity could have been measured by either observer‐rating (our preference) or self‐report. The primary outcome for depressive severity was based on the observer‐rated scale, preferably the Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HRSD) (Hamilton 1960). We combined data on observer‐rated and self‐report outcomes, while prioritising data from observer‐rating scales in case of available data from both observer‐rating scales and self‐report questionnaire.

Acceptability of treatment: as measured by leaving study early for any reason.

Secondary outcomes

Response in depression: defined as 50% or greater reduction in depression severity measures, and global response. We distinguished between response, a relative change in depression severity from baseline, and remission, an absolute endpoint achieved through treatment (Bandelow 2006; Keller 2004). If the original authors reported several outcomes corresponding with our definition of response, we gave preference to HRSD for observer‐rating scale and Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) (Beck 1961) for self‐rating scale. If the authors reported only Clinical Global Impression (CGI) (Guy 1976), we used CGI‐Improvement to define response. If the authors used other measures and definitions of remission to indicate the relative change from baseline, we used the original authors' definition. We presented these different definitions of response used across the included studies. We examined the robustness of this outcome definition hierarchy through a sensitivity analysis limiting the included studies to those reporting on 50% reduction on HRSD. Response is one of the more consistently defined endpoints and has been widely used for defining improvement in acute treatment studies.

Remission in depression: usually defined as 7 or lower on HRSD or 11 or lower on Montgomery and Åsberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS) (Montgomery 1979). If the original authors reported several outcomes corresponding with our definition of remission, we gave preference to the HRSD for observer‐rating scale and BDI for self‐rating scale. If the authors reported only CGI, we used CGI‐Severity to define remission. If the authors used other measures and definitions of remission to indicate the absolute endpoint achieved through treatment, we used the original authors' definition. We presented these different definitions of remission used. Remission is associated with better long‐term outcomes compared with response without remission (Lin 1998).

Anxiety severity: measured using standardised validated continuous scales, either assessor‐rated, such as the Hamilton Anxiety Scale (HAM‐A) (Hamilton 1959) or self‐report, including the Trait subscale of the Spielberger State‐Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI‐T) (Spielberger 1983), and the Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI) (Beck 1988).

Insomnia severity: measured using standardised validated continuous scales, either assessor‐rated or self‐report.

Adverse effects: evaluated by counting numbers of dropouts due to adverse effects and total number of participants experiencing at least one adverse effect.

Timing of outcome assessment

Outcomes were divided into early phase (in this review, defined as two weeks, ranged from one to four weeks), acute phase (defined as eight weeks, ranged five to 12 weeks) and continuous phase (defined as more than 12 weeks). Early phase was our primary time point.

Hierarchy of outcome measures

Due to the great likelihood of more than one reported eligible outcome, we included data as per the following rules:

in case of available data from both observer‐rating scales and self‐report questionnaires, we prioritised data from observer‐rating scales;

in case of several outcome measures of the same hierarchy level used in one study, we selected the outcome measure most frequently used across all studies. Therefore, availability determined the selection of the outcome measure;

in case of several outcome measures of the same hierarchy level and the same availability across studies, the outcome measures were randomly selected.

Search methods for identification of studies

Cochrane Common Mental Disorders Controlled Trials Register (CCMDCTR)

The Cochrane Common Mental Disorders Group (CCMD) maintains two archived clinical trials registers at its editorial base in York, UK: a References register and a Studies Register. The CCMDCTR‐References Register contains over 40,000 reports of RCTs in depression, anxiety and neurosis. Approximately 50% of these references have been tagged to individual, coded trials. The coded trials are held in the CCMDCTR‐Studies Register and records are linked between the two registers using unique Study ID tags. Coding of trials is based on the EU‐Psi coding manual, using a controlled vocabulary (contact the CCMD Information Specialists for further details). Reports of trials for inclusion in the Group's registers are collated from routine (weekly), generic searches of MEDLINE (1950 to 2016), Embase (1974 to 2016) and PsycINFO (1967 to 2016); quarterly searches of the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) and review‐specific searches of additional databases. Reports of trials were also sourced from international trial registers via the World Health Organization's (WHO) International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP), pharmaceutical companies, the handsearching of key journals, conference proceedings, and other (non‐Cochrane) systematic reviews and meta‐analyses.

Details of CCMD's generic search strategies (used to identify RCTs) can be found on the Group's website with an example of the core MEDLINE search used to inform the register displayed in Appendix 1.

The Group's Specialised Register became out of date with the Editorial Group’s move from Bristol to York (UK) in the summer of 2016.

Electronic searches

For the current version of this review the Cochrane Common Mental Disorders Information Specialist conducted initial searches to March 2014 on the CCMDCTR alone. Further update searches were conducted directly on Ovid MEDLINE, Embase, PsycINFO and the Cochrane Library (2014 to 23 May 2019) to account for the period when the CCMDCTR was out of date.

CCMDCTR (Studies and References Register) (all years to 28 June 2016);

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) (2019, Issue 5);

Ovid MEDLINE (2014 to 23 May 2019);

Ovid Embase (2014 to 23 May 2019);

Ovid PsycINFO (2014 to 23 May 2019).

Search strategies are listed in Appendix 2.

We also searched the WHO ICTRP and ClinicalTrials.gov to identify any additional unpublished or ongoing trials to 23 May 2019.

There were no restriction on date, language (Egger 1997), or publication status applied to the searches.

We requested translations of non‐English language trial reports from contacts of the review authors or the Cochrane editorial team.

Search strategies run for the previous, published version of this review are in Appendix 3.

Searching other resources

Reference searching

We checked the references lists of all included studies for citations to additional published or unpublished research. We also conducted a forward citation search of the included studies and checked relevant review articles.

Personal communication

We contacted principal investigators, where necessary, to obtain further details of ongoing/unpublished studies, or trials reported as conference abstracts only.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

In 1997 and 1999, one review author assessed every report identified by the search strategy described in Appendix 3 for relevance to this review. The criteria for selection at this stage were simple and broad so as not to miss any relevant study and were:

randomisation;

diagnosis of depression (not necessarily by operationalised criteria);

comparison between antidepressant plus benzodiazepine versus antidepressant alone.

Two review authors independently assessed the eligibility and methodological quality of the included trials.

In December 2004, we performed an updating search in the following manner. Two review authors assessed every report identified by a search of the Cochrane Group's specialised register (previously called the CCDANCTR). One review author (TAF) obtained and checked the full reports of all the studies that were rated positive by either review author according to the above mentioned approximate eligibility criteria.

For this version of the reiew, we performed study selection in the following manner. All reports of trials already included and excluded in the previous versions of this review were removed from reports identified by an update search of the Cochrane Groups' renamed specialised register (CCMDCTR) and other bibliographic database search results. Two review authors examined the titles and abstracts of all remaining reports. We obtained and inspected the full articles of all the studies identified by either of the review authors. We discussed conflicts of opinion regarding eligibility of a study with a third review author, having retrieved the full paper and consulted the authors if necessary, until we reached consensus.

Data extraction and management

Two review authors independently extracted the data from the original reports using data extraction forms. We re‐extracted data from the originally included studies as well as extracting data from the newly included studies. The data collected covered:

name and type of study setting;

diagnostic criteria used;

number of participants allocated (their diagnostic composition, age, sex, previous treatment, baseline depressive and anxiety severity, medical comorbidity);

details of intervention, duration of intervention, cointervention (if any);

their depressive and anxiety severity and response rate at one, two, four and eight weeks;

number of dropouts for any reason and later the number of dropouts due to adverse effects, and number of participants with at least one adverse effect.

We resolved any disagreements through discussion and in consultation with the principal investigators.

We note in the Characteristics of included studies table if outcome data were not reported in a usable way. One review author transferred data into the Review Manager 5 (Review Manager 2014). We double‐checked that entered data were correct by comparing the data presented in the systematic review with the study reports. A second review author spot‐checked study characteristics for accuracy against the trial report.

Main planned comparisons

The comparisons were any combination of antidepressants plus benzodiazepines versus antidepressants alone.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

In the original version of this review, we assessed methodological quality of included studies by criteria set out in the Cochrane Collaboration Handbook (Mulrow 1997); however, after publication of the revised and expanded Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011), we updated our methods accordingly. We considered the following seven domains.

Sequence generation: was the allocation sequence adequately generated?

Allocation concealment: was allocation adequately concealed?

Blinding of participants and personnel: was knowledge of the allocated treatment adequately prevented during the study?

Blinding of outcome assessment: was knowledge of the allocated treatment adequately prevented during the study?

Incomplete outcome data for the primary outcome: were incomplete outcome data adequately addressed? (We defined dropouts of 20% or more as high risk of bias.)

Selective outcome reporting: were study reports free of suggestion of selective outcome reporting?

Other sources of bias: was the study apparently free of other problems that could put it at a high risk of bias?

A judgement on the risk of bias was made for each domain, based on the following three categories: high risk of bias, low risk of bias and unclear risk of bias.

Two review authors independently assessed the risk of bias in the included studies. We resolved any disagreement through discussion and in consultation with the principal investigators. Where necessary, we contacted the authors of the studies for further information. We did not include studies where sequence generation was at high risk of bias and where allocation was clearly not concealed.

Measures of treatment effect

Continuous data

We combined continuous outcome variables of depressive and anxiety severity at approximately the same time point using standardised mean differences (SMD) as we expected that the studies would use different scales to measure the same concept. If all outcomes in a continuous meta‐analysis were sufficiently similar, we used mean differences (MDs). We reported 95% confidence intervals (CI).

Change versus endpoint data

We used endpoint data but used change data when endpoint data were not available, as empirical data support such synthesis (da Costa 2013).

Binary data

We included the dichotomous measures of response and remission in our data analysis because they were intuitively easier to understand, were more amenable to worst‐case scenario intention‐to‐treat (ITT) analysis and we expected that some studies may not have reported all the necessary data to enable meta‐analytic summary of a continuous measure but still have contained the data to enable the dichotomous analysis. We combined dichotomous outcome variables such as response, remission, dropout and presence or absence of adverse effects at approximately the same time point using risk ratios (RR) with 95% CIs using the random‐effects model, because these are more interpretable and more generalisable than risk differences, odds ratios or fixed‐effect model RRs (Furukawa 2002). Empirical data suggest that different definitions for response produce similar RRs and are therefore combinable in meta‐analyses (Furukawa 2011).

Unit of analysis issues

Cross‐over trials

For trials that had a cross‐over design, we only considered results from the first randomisation period to avoid carry‐over effects (Elbourne 2002).

Cluster randomised trials

We incorporated results from cluster RCTs into the review using generic inverse variance methods (Higgins 2011). With cluster RCTs, it is important to ensure that the data have been analysed taking into account the clustered nature of the data. We extracted the intracluster correlation coefficient (ICC) for each trial. Where no such data were reported, we requested this information from study authors. If this was not available, in line with the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011), we used estimates from similar studies to 'correct' data for clustering, where this had not been done.

Studies with multiple treatment groups

Multiple‐arm studies contain more than two (intervention, comparison) relevant treatment arms (in addition to the control group there might be different types of interventions or different doses of medication). If data were binary, we added these and combined them in a two‐by‐two table. If data were continuous, we combined data following the formula in Section 7.7.3.8 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011). We did not reproduce irrelevant additional treatment arms, but listed them in the Characteristics of included studies table.

Dealing with missing data

Missing participants

Where possible, we contacted original investigators to request missing data.

Dichotomous data

We analysed all data using the ITT principle: dropouts were always included in this analysis. Where participants were withdrawn from the trial before the endpoint, we assumed that their condition remained unchanged if they had stayed in the trial. This is conservative for outcomes related to response to treatment (because these participants were considered to have not responded to treatment). It is not conservative for adverse events but we considered that for the adverse events of interest in our review as a worst‐case scenario is clinically unlikely. When there were missing data and the method of last observation carried forward (LOCF) was used to do an ITT analysis, then the LOCF data were used with due consideration of the potential bias and uncertainty introduced.

Continuous data

The Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions recommends avoiding imputations of continuous data and suggests that the data must be used in the form presented by the original authors (Higgins 2011). Whenever ITT data were presented by the authors, we preferred them to 'per protocol or completer' data sets.

Missing data

Where studies did not report the number of responders and remitters, we imputed the values by assuming the normal distribution for the HRSD scores at each time point and calculate the number of participants according to a validated imputation method. This way of imputing response rates, especially in the case of the HRSD, has strong empirical support; when the same strategy was employed in four completed meta‐analyses of depression and anxiety, the agreement between the actually observed versus the imputed numbers of responders was almost perfect with an intraclass correlation coefficient of 0.97 (95% CI 0.95 to 0.98) (Furukawa 2005).

If the scores of continuous variables for a particular time point were missing but those for the time points before and after that particular one were reported, we interpolated the values, assuming a linear change between these time points.

Missing statistics

Where studies did not report the standard deviations of continuous measure scores and study authors were unable to provide standard deviations, we calculated the standard deviation from the standard error (SE) or P values (Altman 1996), or from CI, t‐values or P values as described in Section 7.7.3 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011). If this was not possible, we used values from all the studies examined in a previous systematic overview on the antidepressant treatment of depression (Cipriani 2009). Empirical evidence suggests that imputing missing standard deviations this way in meta‐analyses can provide quite accurate results (Furukawa 2006).

Assessment of heterogeneity

We assessed statistical heterogeneity using the Chi2 test, which provides evidence of variation in effect estimates beyond that of chance. Since the Chi2 test has low power to assess heterogeneity when there are few included trials or small numbers of participants, we set the P value conservatively at 0.1. We also quantified heterogeneity using the I2 statistic, which calculates the percentage of variability due to heterogeneity rather than chance.

We interpreted I2 values in accordance with the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011). An approximate guide to interpretation is as follows:

0% to 40%: might not be important;

30% to 60%: may represent moderate heterogeneity;

50% to 90%: may represent substantial heterogeneity;

75% to 100%: considerable heterogeneity.

However, the importance of the observed I2 statistic depends on the magnitude and direction of treatment effects and the strength of evidence for heterogeneity (Higgins 2011). Forest plots generated using Review Manager 5 also provide an estimate of tau2, the between‐study variance in a random‐effects meta‐analysis (Review Manager 2014). Therefore, for the primary outcome, we also used tau2 to give an indication of the spread of true intervention effects.

Assessment of reporting biases

Reporting biases arise when the dissemination of research findings is influenced by the nature and direction of results. We investigated reporting bias by constructing funnel plots and conducting an Egger's test (Egger 1997) when 10 or more studies were pooled for the primary outcomes. We are aware that funnel plots may be useful in investigating reporting biases but are of limited power to detect small‐study effects. We did not use funnel plots for outcomes where there were fewer than 10 studies or where all studies were of similar size.

Data synthesis

We analysed data using Review Manager 5 (Review Manager 2014). The included studies employed a variety of outcome measures at different time intervals. If more than 50% of the participants were lost to follow‐up in any group of the study, we considered this study of low methodological quality and examined the effects of including or excluding it in the sensitivity analysis.

We employed the random‐effects model because it incorporates an assumption that the different studies are estimating different, yet related, intervention effects. However, we examined whether use of a fixed‐effect model led to a substantial difference in the primary outcome.

We reported outcome measures for dichotomous data as RRs with 95% CIs and continuous data as SMDs as we expected that the studies would use different scales to measure the same concept. If all outcomes in a continuous meta‐analysis were sufficiently similar, we used MDs.

We calculated the number needed to treat for an additional beneficial outcome (NNTB) by taking the mean event rate among the controls and then applying RR to this rate. That is, NNTB = 1/(RR × mean – mean).

If a meta‐analysis was not possible (e.g. due to insufficient data or high levels of heterogeneity), we gave a narrative assessment of the evidence. This summarised the evidence according to intervention type.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

Subgroup analyses should be performed and interpreted with caution because multiple analyses lead to false‐positive conclusions (Oxman 1992). Nevertheless, we addressed the following a priori defined potential effect modifiers of the primary outcome.

Severity of comorbid anxiety (divided according to the median of the reported mean the HAM‐A total scores at baseline). This analysis examined effect moderation due to comorbid anxiety which may affect treatment recommendations and outcomes. We conducted analyses using the same methods as for the main analysis.

Differences between short‐acting benzodiazepines (less than 12 hour half‐life, such as triazolam, midazolam, brotizolam, oxazepam, temazepam) (Vermeeren 2004) given at bedtime and the others (such as long‐acting benzodiazepines taken at bedtime and anxiolytic benzodiazepines taken during the day). The latter may have some anxiolytic effects and affect the mood during the day, while the former may not have such effects.

Types of antidepressants, that is, SSRIs plus benzodiazepine versus SSRIs alone, TCAs plus benzodiazepine versus TCAs alone.

These analyses examined if types of drugs affected treatment recommendations and outcomes. We conducted analyses using the same methods as for the main analyses to determine if the method of data aggregation made any difference.

Sensitivity analysis

We conducted the following sensitivity analyses of the primary outcomes to test how robust our findings were to decisions made in the review process.

Fixed‐effect instead of random‐effects model. We used the random‐effects model for all main analyses. We conducted fixed‐effect analyses using the same data as the main analyses.

Exclusion of non‐double blind trials. We include open trials for main analyses. We conducted this analysis using the same data as for the main analyses.

Exclusion of trials using only self‐report. We planned to do this analysis because studies involving people with depression that use both clinician‐ and self‐report measures to assess depression severity have found that clinician and self‐reports of depression severity are not in agreement (Bailey 1976; Domken 1994; Rush 1987; Tondo 1988).

Limiting studies to those reporting on 50% reduction on HRSD. We conducted main analyses including trials in which response was not reported and imputed for all main analyses. We conducted this analysis using the same data as for the main analyses to determine if the study imputation made any differences.

Exclusion of trials with a high risk of bias because of incomplete outcome data. This analysis demonstrates the importance of the use of those trials, and the levels of confidence and caution that should be exercised in considering the analyses of all studies. We chose this domain as the one most likely to impact on our results.

Exclusion of trials where missing actual outcome data were imputed. We intended to conduct analyses including trials in which actual outcome data were not reported and imputed for all main analyses. We conducted this analysis using the same data as for the main analyses.

Giving half the weight to arms marketed by the sponsor of the trial in order to adjust for sponsorship bias. This sensitivity analysis is particularly important because repeated findings indicate that funding strongly affects outcomes of research studies (Als‐Nielsen 2003; Bhandari 2004; Lexchin 2003).

'Summary of findings' tables

We prepared 'Summary of findings' tables for all relevant comparisons. Each table included all outcomes. The quality of the body of evidence was assessed by the GRADE approach.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

See: Characteristics of included studies; Characteristics of excluded studies tables.

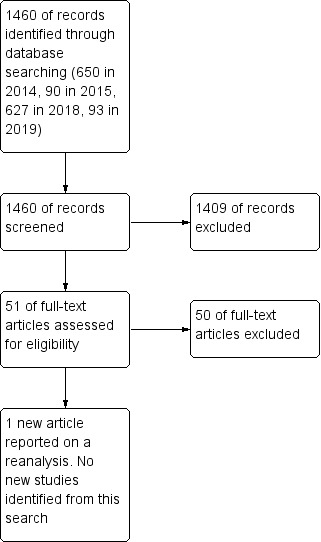

We conducted initial searches up to March 2014. After deduplication and removing reports of trials included and excluded in the previous review, we retrieved 650 references from the specialised register of the Cochrane Common Mental Disorders Group (CCMDCTR). Two review authors (YO and NT, YH or AT) independently screened 650 records and excluded 611 records based on their titles and abstracts as they evidently did not meet the inclusion criteria. We retrieved the full‐text papers for the remaining 39 reports and assessed them for eligibility. Forward and backward citation tracking of the included articles yielded no further relevant trials. One new article (Papakostas 2010) reported on a re‐analysis of data from Smith 1998. We identified no new studies from this search since the previous publication of this review in 2005. The update search in June 2015 retrieved an additional 90 references and found no additional studies. The update search in May 2018 retrieved an additional 627 references and found no additional studies. The update search in May 2019 retrieved an additional 93 references and found no additional studies (Figure 1).

1.

Study flow diagram for 2019 update.

Included studies

The review included 10 studies (Calcedo Ordonez 1992; Dominguez 1984; Fawcett 1987; Feet 1985; Feighner 1979; Nolen 1993; Scharf 1986; Smith 1998; Smith 2002; Yamaoka 1994). See Characteristics of included studies table.

Design

All included studies used a randomised, controlled, parallel‐group design. We identified no eligible cluster‐randomised or cross‐over trials.

Sample sizes

The study by Feighner 1979 had the largest study population with 190 participants randomised. A total of 126 participants participated in Dominguez 1984, 83 in Calcedo Ordonez 1992, 80 in Smith 1998, and 50 in Smith 2002. The total number of participants included in the review was 731.

Setting

Six studies took place in the US (Dominguez 1984; Fawcett 1987; Feighner 1979; Scharf 1986; Smith 1998; Smith 2002), with one each in the Netherlands (Nolen 1993), Spain (Calcedo Ordonez 1992), Norway (Feet 1985), and Japan (Yamaoka 1994).

Participants

All included trials enrolled people with a diagnosis of major depression based on Feighner (Feet 1985; Feighner 1979), DSM‐III (Dominguez 1984; Fawcett 1987; Scharf 1986; Yamaoka 1994), DSM‐III‐R (Calcedo Ordonez 1992; Nolen 1993) and DSM‐IV (Smith 1998; Smith 2002). Mean ages ranged from 34.8 years (Calcedo Ordonez 1992) to 48.8 years (Scharf 1986).

Interventions

Studies used a range of antidepressants including fluoxetine (Smith 1998; Smith 2002), imipramine (Dominguez 1984; Fawcett 1987), amitriptyline (Feighner 1979; Scharf 1986), clomipramine (Calcedo Ordonez 1992), desipramine (Fawcett 1987), and mianserin (Yamaoka 1994). Nolen 1993 allowed choice between maprotiline and nortriptyline. In regards to benzodiazepines, studies used clonazepam (Smith 1998; Smith 2002), triazolam (Dominguez 1984), lormetazepam (Nolen 1993), bentazepam (Calcedo Ordonez 1992), alprazolam (Fawcett 1987), diazepam (Feet 1985), flunitrazepam (Nolen 1993), mexazolam (Yamaoka 1994), and chlordiazepoxide (Feighner 1979; Scharf 1986).

Outcomes

Primary outcome assessment

The primary outcome in this review was a continuous measure of severity of depression, which all 10 studies assessed. Nine studies used the HRSD and one study used the Comprehensive Psychopathological Rating Scale (CPRS) (Feet 1985). Four RCTs reported response rates defined as at least 50% decrease in HRSD score from baseline. Three RCTs reported remission, defined as 8 or lower on HRSD (Smith 2002), much or very much improved on CGI (Smith 1998), and "global evaluation score on VAS [visual analogue scale] less than 10%" (Feet 1985). All studies reported overall dropout rates and dropout rates due to adverse effects.

Excluded studies

See Characteristics of excluded studies table.

We excluded studies for the following reasons: no operationalised diagnostic criteria (Ahmed 1988; Eckmann 1974; Johnstone 1980; Morakinyo 1970; Rickels 1970; Smith 1975), duration of the trial was shorter than four weeks (Ballinger 1974; Bowen 1978; Levin 1985; Magnus 1975; Runge 1985; Smith 1973), and dosage of the antidepressant was inadequate (Dimitriou 1982; Eckmann 1974; Otero 1994; Tsaras 1981; Yamada 2003). No studies were excluded for reasons of high risk of bias for sequence generation or allocation concealment.

Studies awaiting classification

There were no studies awaiting classification.

Ongoing studies

There were no ongoing studies.

New studies included in this update

We included one new article in this update (Papakostas 2010) reporting on a reanalysis of data from Smith 1998. The updated search identified no new studies.

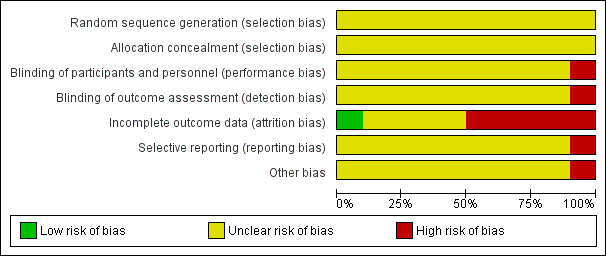

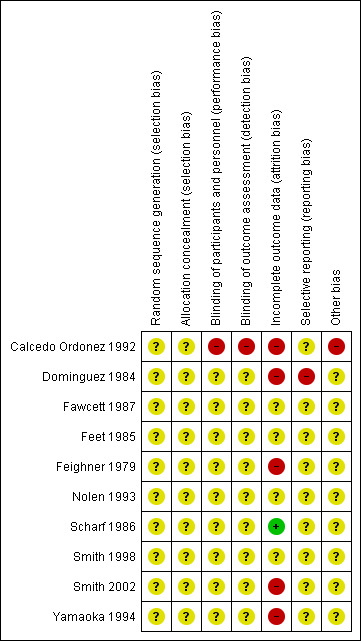

Risk of bias in included studies

For details of the risk of bias judgements for each study, see Characteristics of included studies table. A graphical representation of the overall risk of bias in included studies is presented in Figure 2 and Figure 3.

2.

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

3.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Allocation

Sequence generation

No included studies described methods of random sequence generation.

Allocation concealment

No included studies provided details on allocation concealment.

Blinding

Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias and detection bias)

All studies except one open study (Calcedo Ordonez 1992) explicitly stated the double‐blind condition of their studies, but blinding itself was not adequately described in the methods section in most studies.

Blinding of outcome assessment (assessment bias)

One study was an open trial so the risk of bias for blinding of outcome assessment was high (Calcedo Ordonez 1992). No details were provided on who performed the outcome assessments in the other studies so the risk of bias for blinding of outcome assessment were unclear.

Incomplete outcome data

The greatest risk of bias in the studies included in this review came from incomplete outcome data (attrition bias), with only one study having low risk of bias in this domain (Scharf 1986). Four studies had very high risk of attrition bias, with 13 participants withdrawing from the study out of 32 participants randomised (41%) (Yamaoka 1994), 48 out of 126 (38%) (Feighner 1979), 64 out of the 190 (34%) (Dominguez 1984), and 18 out of 50 (36%) (Smith 2002). This means that the study findings must be interpreted extremely cautiously. However, reasons for dropout and numbers of dropouts were similar between treatment groups and sensitivity analyses assuming that all dropouts had either positive or negative outcomes in the trial found that combination therapy remained significantly more effective than antidepressant monotherapy in the early phase. This suggests that the primary finding was robust to a range of outcomes for dropouts. Calcedo Ordonez 1992 had high risk of bias from incomplete outcome data, because significantly more participants withdrew from the monotherapy than the combination group in the first eight weeks of the study and there was high attrition from both groups (withdrawal rates: 17/47 (36%) with monotherapy and 4/36 (11%) with combination group). Reasons for withdrawal were assessed and although "side effects" did not differ in frequency between the two groups, significantly more participants in the monotherapy group withdrew by "need to administer hypnotics", which may reflect factors associated with clinical outcomes. There was some evidence of potential risk of bias of incomplete outcome data in five studies, but we rated this as unclear owing to insufficient details in the report (Fawcett 1987; Feet 1985; Feighner 1979; Nolen 1993; Smith 1998).

Selective reporting

The protocols were unavailable in all studies. Bias from selective outcome reporting was unclear in all studies.

Other potential sources of bias

In Calcedo Ordonez 1992, more participants in the combination therapy group (11 participants) than in the control group (one participant) needed to take hypnotics and the risk of bias for other potential sources (performance bias due to cointervention) was high. Other studies provided insufficient information to assess other bias so the risk of bias for other potential sources was unclear.

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1

All included studies reported effect on depressive symptoms as their primary outcome. Five studies included response rates and three studies included remission rates.

Primary outcomes

Depressive severity

Antidepressants plus benzodiazepines therapy was more effective than the antidepressant alone in the early phase (SMD –0.25, 95% CI –0.46 to –0.03, 10 studies, 598 participants; Analysis 1.1), but there was no difference in the acute phase (SMD –0.18, 95% CI –0.40 to 0.03; 7 studies, 347 participants; Analysis 1.2) or continuous phase (SMD –0.21, 95% CI –0.76 to 0.35; 1 study, 50 participants; Analysis 1.3). There was a moderate level of heterogeneity in the overall results (I2 = 35%) in the early phase, but there was no evidence of heterogeneity (I2 = 0%) in the acute phase.

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Combination versus antidepressant (AD) alone: depressive severity, Outcome 1 Early phase (2 weeks, range 1–4 weeks).

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Combination versus antidepressant (AD) alone: depressive severity, Outcome 2 Acute phase (8 weeks, range 5–12 weeks).

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Combination versus antidepressant (AD) alone: depressive severity, Outcome 3 Continuous phase (> 12 weeks).

Acceptability of treatment

We found no difference between combination therapy and antidepressant monotherapy in terms of dropout for any reason (RR 0.76, 95% CI 0.54 to 1.07; 10 studies, 731 participants; Analysis 2.1). There was moderate level heterogeneity in the overall results (I2 = 36%).

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Combination versus antidepressant (AD) alone: acceptability of treatment, Outcome 1 Dropout for any reason.

Secondary outcomes

Response in depression

Combination therapy was more effective than monotherapy in the early phase (RR 1.34, 95% CI 1.13 to 1.58; 10 studies, 731 participants; Analysis 3.1), but there was no evidence of a difference in the acute phase (RR 1.12, 95% CI 0.93 to 1.35; 7 studies, 383 participants; Analysis 3.2) or continuous phase (RR 0.97, 95% CI 0.73 to 1.29; 1 study, 52 participants; Analysis 3.3). Taking the mean control event rate of the included RCTs, the obtained RRs could be translated into the following NNTBs. The NNT for improvement in depression was 9 (95% CI 6 to 24) in the early phase, according to the ITT analysis. There was no evidence of heterogeneity in the overall results (I2 = 0%) in the early phase, but there were moderate levels of heterogeneity (I2 = 31%) in the acute phase.

3.1. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Combination versus antidepressant (AD) alone: response in depression, Outcome 1 Early phase (2 weeks, range 1–4 weeks).

3.2. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Combination versus antidepressant (AD) alone: response in depression, Outcome 2 Acute phase (8 weeks, range 5–12 week).

3.3. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Combination versus antidepressant (AD) alone: response in depression, Outcome 3 Continuous phase (> 12 weeks).

Remission in depression

Combination therapy was more effective than monotherapy in the early phase (RR 1.39, 95% CI 1.03 to 1.90; 10 studies, 731 participants; Analysis 4.1), but there was no evidence of a difference in the acute phase (RR 1.27, 95% CI 0.99 to 1.63; 7 studies, 383 participants; Analysis 4.2) or continuous phase (RR 1.31, 95% CI 0.80 to 2.16; 1 study, 52 participants; Analysis 4.3). There was no evidence of heterogeneity in the overall results (I2 = 2%) in the early phase, but there was low‐to‐moderate heterogeneity (I2 = 25%) in the acute phase.

4.1. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Combination versus antidepressant (AD) alone: remission in depression, Outcome 1 Early phase (2 weeks, range 1–4 weeks).

4.2. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Combination versus antidepressant (AD) alone: remission in depression, Outcome 2 Acute phase (8 weeks, range 5–12 weeks).

4.3. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Combination versus antidepressant (AD) alone: remission in depression, Outcome 3 Continuous phase (> 12 weeks).

Anxiety severity

Three studies reported anxiety severity in the early and acute phases. There were no differences between combination therapy and monotherapy in the early phase (SMD –0.76, 95% CI –1.67 to 0.14, 3 studies, 129 participants; Analysis 5.1) or acute phase (SMD –0.48, 95% CI –1.06 to 0.10; 3 studies, 129 participants; Analysis 5.2). There were substantial levels of heterogeneity in the overall results in the early phase (I2 = 81%) and in the acute phase (I2 = 57%) possibly because the studies used different antidepressants and benzodiazepines. No studies reported anxiety severity in the continuous phase.

5.1. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Combination versus antidepressant (AD) alone: anxiety severity, Outcome 1 Early phase (2 weeks, range 1–4 weeks).

5.2. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Combination versus antidepressant (AD) alone: anxiety severity, Outcome 2 Acute phase (8 weeks, range 5–12 weeks).

Insomnia severity

We found no data on insomnia severity.

Adverse effects

The participants allocated to combination therapy were less likely to drop out from the treatment due to adverse effects than those receiving antidepressants monotherapy (RR 0.54, 95% CI 0.32 to 0.90; 10 studies, 731 participants; Analysis 6.1). There was no evidence of heterogeneity (I2 = 0%). However, the combination group reported at least one adverse effect more often than the monotherapy group (RR 1.12, 95% CI 1.01 to 1.23; 7 studies, 510 participants; Analysis 6.2). There was no evidence of heterogeneity (I2 = 0%).

6.1. Analysis.

Comparison 6 Combination versus antidepressant (AD) alone: adverse effects, Outcome 1 Dropouts due to adverse effects.

6.2. Analysis.

Comparison 6 Combination versus antidepressant (AD) alone: adverse effects, Outcome 2 Number of participants with ≥ 1 adverse effect.

Subgroup analyses

Severity of comorbid anxiety

Only two studies (involving 109 participants) reported HAM‐A score at baseline or screening period. Participants of one study had moderate‐to‐severe anxiety (Calcedo Ordonez 1992) and those of the other study had mild‐to‐moderate anxiety (Fawcett 1987). There was no difference in effect between these two studies in either the early or acute phases (Analysis 7.1; Analysis 7.2).

7.1. Analysis.

Comparison 7 Subgroup analysis: severity of comorbid anxiety, Outcome 1 Depression severity, early phase (2 weeks, range ranged 1–4 weeks).

7.2. Analysis.

Comparison 7 Subgroup analysis: severity of comorbid anxiety, Outcome 2 Depression severity, acute phase (8 weeks, range 5–12 weeks).

Differences between short‐acting benzodiazepines given at bedtime and the others

The two studies that used a short‐acting benzodiazepine at bedtime produced SMD of –0.66 (95% CI –1.53 to 0.20) in the early phase, and –0.07 (95% CI –0.46 to 0.32) in the acute phase (Dominguez 1984; Nolen 1993), compared with the other eight studies that did not use a short‐acting benzodiazepines at bedtime, producing an SMD of –0.28 (95% CI –0.53 to –0.03) in the early phase and –0.15 (95% CI –0.37 to 0.07) in the acute phase. There was no evidence of a difference between types of benzodiazepines in the early phase (subgroup I2 = 21%, P = 0.38; Analysis 1.1) or acute phase (subgroup I2 = 0%, P = 0.47; Analysis 1.2). In addition, no evidence of a difference in acceptability of treatment was found between types of types of benzodiazepines (subgroup I2 = 0%, P = 0.99; Analysis 2.1).

Types of antidepressants

Exploratory analysis for each class of of antidepressants (TCAs, SSRIs and other antidepressants) for our primary outcomes suggested a difference between TCA plus benzodiazepine compared with TCA alone in the acute phase (SMD –0.29, 95% CI –0.50 to –0.09; 6 RCTs, 529 participants), but no difference for SSRIs (SMD –0.30, 95% CI –0.64 to 0.05; 2 RCTs, 130 participants) or mianserin, the only compound in the 'other antidepressants' class (SMD 0.22, 95% CI –0.72 to 1.15; 1 trial, 19 participants) (Analysis 8.1). However, there were no differences between these subgroups (subgroup I2 = 0%, P = 0.58) for either severity of depression of for acceptability of treatment (subgroup I2 = 52%, P = 0.13; Analysis 8.2).

8.1. Analysis.

Comparison 8 Subgroup analysis: types of antidepressants (AD), Outcome 1 Depression severity (2 weeks, range 1–4 weeks).

8.2. Analysis.

Comparison 8 Subgroup analysis: types of antidepressants (AD), Outcome 2 Acceptability of treatment as measured by dropout for any reason.

Sensitivity analyses

Results were consistent in sensitivity analyses according to a fixed‐effect instead of a random‐effects model (Analysis 9.1), exclusion of non‐double blind trials (Analysis 10.1), response limiting the studies to those reporting 50% reduction on HRSD (Analysis 11.1), exclusion of trials with a high risk of bias because of incomplete outcome data (Analysis 12.1), or exclusion of trials where missing actual outcome data were imputed (standard deviation were imputed in excluded trials) (Analysis 13.1). We did not perform the sensitivity analysis excluding trials using self‐report because all studies reported observer‐rated scales. We did not perform the sensitivity analysis giving half the weight to arms marketed by the sponsor of the trial because we found no study without the sponsor.

9.1. Analysis.

Comparison 9 Sensitivity analysis: fixed‐effect instead of random‐effects model, Outcome 1 Depression severity (2 weeks, range 1–4 weeks).

10.1. Analysis.

Comparison 10 Sensitivity analysis: exclusion of non‐double blind trials, Outcome 1 Depression severity.

11.1. Analysis.

Comparison 11 Sensitivity analysis: limiting studies to those reporting on 50% reduction on Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression, Outcome 1 Response (2 weeks, range 1–4 weeks).

12.1. Analysis.

Comparison 12 Sensitivity analysis: exclusion of trials with a high risk of bias because of incomplete outcome data, Outcome 1 Depression severity.

13.1. Analysis.

Comparison 13 Sensitivity analysis: exclusion of trials where missing actual outcome data were imputed, Outcome 1 Depression severity (2 weeks, range 1–4 weeks).

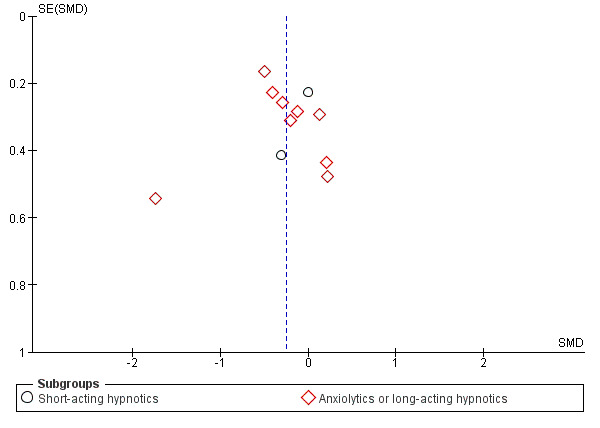

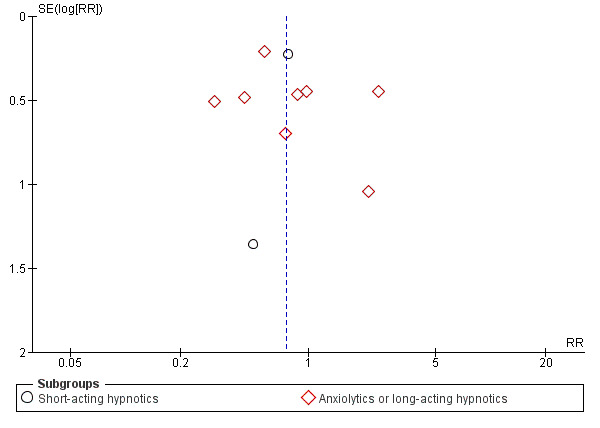

Reporting bias

There was no evidence of possible funnel plot asymmetry for either primary outcomes: depression severity and acceptability of treatment. The graphs appeared symmetrical (see Figure 4; Figure 5) and the Egger's test for bias was not significant (depression severity: P = 0.819; acceptability of treatment: P = 0.073).

4.

Funnel plot of comparison: 1 Depression severity, outcome: 1.1 Early phase (two weeks, range one to four weeks).

5.

Funnel plot of comparison: 2 Acceptability of treatment, outcome: 2.1 Dropout for any reason.

Discussion

Summary of main results

See Table 1 for the main comparison.

Aggregating 10 studies involving 731 participants, antidepressant plus benzodiazepine therapy was more effective in the early phase (one to four weeks) than antidepressant monotherapy, but there was no evidence of a difference in the acute phase (five to 12 weeks) and in the continuous phase (more than 12 weeks). Participants allocated to the combination treatment were as likely to drop out from the treatment as those allocated to antidepressant alone. NNTB analysis suggested that nine participants need to be treated with an antidepressant plus a benzodiazepine in the early phase for one additional participant to show 50% or greater reduction in his or her depressive severity from baseline. Although the available studies were limited, we could find no evidence to suggest that the baseline comorbid anxiety level would alter these general findings.Six of the included studies examined TCAs, two examined SSRIs and one examined mianserin but there was no subgroup heterogeneity due to antidepressant classes (TCAs: –0.29, 95% CI –0.50 to –0.09, 6 RCTs, 529 participants; SSRIs: –0.30, 95% CI –0.71 to 0.05, 2 RCTs, 130 participants; other antidepressants (mianserin): 0.22, 95% CI –0.72 to 1.15, 1 trial, 19 participants; test for subgroup difference P = 0.58, subgroup heterogeneity I2 = 0%). The observed difference in effect between different classes of antidepressants is uncertain; whilst there may be a difference in effect, further evidence is required. In the acute and continuous phase, the relative risk for response was not statistically significant and the possibility that the combination therapy might actually lessen or might not influence the response rate could not be ruled out, although it is also possible that the corresponding NNTB could be as small as four.

These are clinically meaningful figures. For example, chlorpromazine prevents one participant out of 14 from dropping out of treatment, and promotes global improvement in one out of nine to 12 people with schizophrenia who are treated with it instead of placebo (Leucht 2013). The number needed to treat of second‐generation antipsychotics in acute mania is about four (Correll 2010) and that of antidepressants for major depression is about nine (Arroll 2009). In other words, combining a benzodiazepine with an antidepressant is as effective as chlorpromazine over placebo for acute schizophrenia, and nearly as effective as lithium over placebo for acute mania or SSRI over placebo for major depression.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

Our conclusions were only based 10 studies that fulfilled our inclusion criteria. We performed a subgroup analysis to compare short‐acting benzodiazepines (less than 12 hour half‐life) given at bedtime and the others (such as long‐acting benzodiazepines taken at bedtime and anxiolytic benzodiazepines taken during the day) because the latter may have some anxiolytic effects and affect the mood during the day, while the former may not have such effects. Most of the included studies used TCA and long‐acting benzodiazepines taken at bedtime or anxiolytic benzodiazepines taken during the day. Meta‐analysis of SSRIs included only two studies and there were insufficient data to conduct meta‐analyses for the other antidepressants (e.g. serotonin‐noradrenaline reuptake inhibitors). However, there was no subgroup heterogeneity noted either visually or statistically between TCAs and SSRIs, or between short‐acting benzodiazepines given at bedtime or other benzodiazepines.

Quality of the evidence

Our judgements of quality according to GRADE are given in the Table 1 for the main comparison. All included trials were RCTs and were similar in design and conduct. However, the evidence upon which the findings of this review were based was relatively poor as evaluated with the Cochrane 'Risk of bias' tool, and this was also reflected in our grading within Table 1. Most domains of risk of bias in majority of included studies were unclear. Random sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding and selective outcome reporting were problematic due to insufficient details in most included studies and lack of availability of study protocols. Most studies included in our review were described as 'double‐blind', but none of the RCTs reported information on the procedure followed to guarantee the blindness and if blinding was successful. In addition, less than half of the studies reported most secondary outcomes (except dropout due to adverse effects), which is likely to have introduced bias for these data. The greatest limitation to the quality of evidence was issues with attrition. Some studies had high rates of dropout (the highest being 41% dropout in Yamaoka 1994). The amount of attrition was generally well described, but the timings of dropout were often insufficiently detailed to assess the likelihood of meaningful bias. We downgraded all our findings by one level for these study limitations. The quality of evidence evaluated with the GRADE methodology was moderate for depression in the early phase, acceptability of treatment and adverse effects, low for depression in the acute and continuous phases, and very low for anxiety severity in the early phase. The included participants in the outcome of anxiety severity amounted to 129 and the CIs were wide. Heterogeneity among the included studies was high, possibly because the studies used different antidepressants and benzodiazepines. We found no possible factors that would upgrade the quality of the evidence.

Potential biases in the review process

First, the most important weakness in this review was that only one trial followed the participants beyond eight weeks. Therefore, the present meta‐analysis could only provide information for early and acute phases and, with less statistical power, up to 14 weeks. Three studies examined withdrawal of acute‐phase benzodiazepines and two demonstrated some rebound (Feet 1985; Smith 1998), whereas another, which extended the use up to 12 weeks, did not (Smith 2002). Second, it is of note that all but three studies involved TCAs: two studies employed fluoxetine and one employed mianserin. However, the two studies employing fluoxetine (Smith 1998; Smith 2002) were in line with the other studies in terms of response rates according to tests of heterogeneity. Third, it could be argued that that the response in terms of HRSD may reflect changes in sleep and anxiety only and not in core depressive symptoms. By calculating anxiety subscale and insomnia subscale scores out of the total HRSD, Smith 1998 found significant superiority of the combined fluoxetine plus clonazepam treatment for all subscales. Smith 2002, employing basically identical procedures, confirmed superiority in terms of the insomnia subscale only. The one study focusing on anxious depression demonstrated superiority of the combined treatment (Feighner 1979), whereas the other study focusing on non‐anxious depression reported equivalence (Feet 1985). Therefore, three studies suggested that combination therapy outperformed antidepressant monotherapy when anxiety or insomnia were present, while such superiority for depression without these accompanying symptoms remained to be further examined (Feighner 1979; Smith 1998; Smith 2002). Fourth, we included one study with a dropout rate above 40% (Yamaoka 1994), and four studies with dropout rate above 20% (Calcedo Ordonez 1992; Dominguez 1984; Feighner 1979; Smith 2002). This may have introduced bias, but the findings of this review were robust to sensitivity analysis excluding trials with a high risk of bias because of incomplete outcome data. Fifth, some numbers had to be imputed from data reported in the RCT itself or from data of other RCTs.

At the review level, we consider the systematic review process identified all relevant trials. We attempted to identify relevant studies through database searches and citation tracking. Despite these efforts, it is possible that publication bias may have influenced the review findings. However, there was no evidence of possible funnel plot asymmetry for either primary outcome. The graphs appeared to be symmetrical and the Egger's test for bias was not significant.

For this updated review, we edited the methods section to bring it up to date with Cochrane's current methodological standards and made several updates to the protocol (e.g. the inclusion of remission as a secondary outcome, change the timing of outcome assessment and inclusion of limiting the studies to those reporting on 50% reduction on HRSD as sensitivity analysis, assessment of quality of evidence according to GRADE). All these changes in the protocol were made and appeared through peer reviews prior to the actual conduct of updating the review. Since we used the original authors' own definitions of response or remission if they used such definitions, we should consider the possibility of outcome measure reporting bias. However, there was only one study (Feet 1985) which used the authors' own definition for remission (<2.5 cm out of 10 cm Visual Analog System).

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

We edited the methods section to bring it up to date with Cochrane's current methodological standards from previous version of this review. While changes to the protocol may have introduced bias in the review process, most changes made here had no impact on the current review. We added remission to the secondary outcomes and two sensitivity analyses (exclusion of trials using only self‐report; limiting the studies to those reporting on 50% reduction on HRSD) and results were consistent in sensitivity analyses.

The benefits of adding a benzodiazepine to an antidepressant must be balanced judiciously against possible harms, including development of dependence, tolerance, accident proneness, teratogenicity and costs. While this review could not address specific downsides of benzodiazepine use, there is abundant literature suggesting them.

It is well recognised that benzodiazepines can induce dependence, defined as development of clinically meaningful symptoms upon its discontinuation. Although the reported incidence differs widely among studies, dependence is generally estimated to occur in almost one third of participants receiving regular prescription of a benzodiazepine for four weeks or longer (Noyes 1988; Schweizer 1998).

In the case of the antidepressant plus benzodiazepine combination therapy, discontinuation of benzodiazepine may cause, in addition to the above mentioned discontinuation symptoms, worsening of symptoms due to loss of synergistic treatment effects or to unmasking of adverse effects of antidepressants.