Abstract

Vertical sleeve gastrectomy (VSG) is an effective therapeutic approach for obesity and type 2 diabetes but is associated with osteoporosis. In this issue of the JCI, Li et al. report that VSG rapidly reduces bone mass, as observed in humans, via rapid demineralization and decreased bone formation, independent of weight loss or Ca2+/vitamin D deficiency. VSG also reduces bone marrow adipose tissue, in part via increased granulocyte–colony stimulating factor (G-CSF). The interplay between VSG-mediated effects on systemic metabolism and bone biology remain to be investigated. These findings suggest novel mechanisms and therapeutic targets for bariatric surgery–induced osteoporosis.

Impact of bariatric surgery on bone health

Obesity and type 2 diabetes (T2D) are important public health threats worldwide. Bariatric surgeries, such as vertical sleeve gastrectomy (VSG) and Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB), are powerful interventions that can lead to marked and sustained weight loss, improved control of T2D, and reduced cardiovascular mortality. Understanding the mechanisms responsible for these impressive outcomes as well as the side effects that limit their success is a critical scientific and medical need.

Previous studies in humans and mice have highlighted that both VSG and RYGB are associated with rapid bone loss and increased risk of osteoporosis and fracture over time. Bone loss was initially attributed to vitamin D deficiency and reduced absorption of calcium, especially after RYGB (1). Subsequent studies demonstrated increased markers of bone turnover, increased marrow adiposity, and other potent effects on bone metabolism after both VSG and RYGB, even when vitamin D levels are sufficient (2, 3). However, the mechanisms responsible for these Ca2+/vitamin D–independent effects of VSG and RYGB on bone health and the differences between the two procedures are not well understood in humans. In this issue, Li and colleagues investigate the impact of VSG on bone health, bone marrow adipose tissue (BMAT), and potential contributors to surgery-induced osteoporosis in a rodent model (4) (Figure 1). In mice fed a high-fat diet (HFD) to induce obesity, VSG caused both trabecular and cortical bone loss as early as two weeks after surgery. While the effects of VSG on body weight were greater in mice fed a HFD, bone loss was independent of sex, body weight, and diet. VSG was associated with impaired mineralization of osteoid and reduced bone formation, despite normal serum levels of calcium, vitamin D, and parathyroid hormone.VSG also had a major impact on the marrow niche, with reductions in BMAT. Interestingly, effects were distinct in subpopulations of marrow adipocytes, with near-complete loss of regulated BMAT and lesser effects on the so-called constitutive BMAT at only one week after surgery, even before bone loss. This is particularly interesting because these subpopulations are regulated independently of peripheral adipose tissue and have distinct developmental and transcriptional lineages (5). Hematopoietic lineages were also modified early after VSG, with increased myeloid cells and reduced erythroid cells.

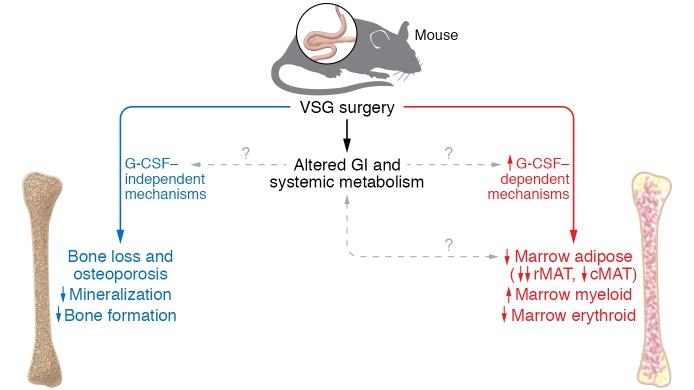

Figure 1. VSG induces bone loss by reducing mineralization and bone formation.

VSG-induced bone loss (left). In parallel, G-CSF decreases bone marrow adipose tissue and activates myeloid proliferation (right). The contribution of altered gastrointestinal physiology and systemic metabolism to both bone loss and increased G-CSF remain to be investigated.

Mechanisms underlying the effects of bariatric surgery on bone loss

Which mechanisms mediate these diverse effects of bariatric surgery on bone and the marrow niche? Li and colleagues hypothesized that granulocyte–colony stimulating factor (G-CSF) might contribute to the robust increase in myeloid-lineage cells in the marrow and bone loss after VSG. Indeed, G-CSF was markedly increased as early as one week after VSG surgery in mice, with more modest increases observed in a human cohort. The mechanisms responsible for increased G-CSF remain uncertain. Experimental increases in G-CSF stimulated myelopoiesis, as expected, while also reducing bone marrow adipocytes and bone mass. Finally, the effects of VSG on bone marrow phenotypes were reduced in G-CSF–null mice. However, bone mass was still reduced after VSG in G-CSF–null mice, indicating that other factors are required for VSG-induced bone loss.

What additional factors modulated in response to intestinal surgery might contribute to bone loss and changes in the marrow niche? After both VSG and RYGB, ingested food rapidly exits the revised stomach pouch. This accelerated delivery of undigested food to the intestine yields pleiotropic effects on intestinal cell populations, secretion of metabolically active peptides, increases in bile acids, changes in the microbiome, and altered absorption of glucose and other nutrients — all potential mediators of the so-called gut-brain-liver axis regulating appetite and systemic metabolism (6). Li et al. demonstrate that weight loss, changes in calcium metabolism (at least those discernible from plasma measurements), and the intestinally derived hormones GLP1/2 are not required for the profound bone loss occurring early after VSG. However, many additional candidates could contribute to bone metabolic effects. These could be primary (resulting directly from changes in intestinal anatomy) or secondary (resulting from changes in systemic metabolism). For example, intestinally derived hormone peptide YY, which is induced after bariatric surgery, has been linked with increased bone turnover in mice (7). By contrast, the glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide (8), also increased after surgery, can inhibit markers of bone resorption (9). The gut microbiome can also regulate bone mass; thus, bacterial species or their metabolic byproducts altered in response to VSG may be an important missing link in this paradigm (10). Changes in bile acid levels or metabolism, downstream pathways stimulated by bile acids, and other metabolites could contribute to functional changes in bone and or marrow adipocyte populations (11, 12).

Beyond the gastrointestinal tract, bariatric surgery induces secondary changes in other metabolically active organs such as muscle and pancreatic islets. Interestingly, a muscle-derived hormone, irisin, is increased after both bariatric surgery and exercise, and can modulate bone mineralization (13, 14). Thus, irisin could mediate a muscle-bone axis altered after bariatric surgery. Likewise, plasma levels of G-CSF are increased after exercise, potentially from muscle (15). Bariatric surgery and weight loss improve whole-body insulin sensitivity, with reduced fasting insulin levels. Because insulin is anabolic for bone, it would be interesting to investigate the contribution of insulin and other growth factors to bone remodeling after bariatric surgery (16, 17).

Bone marrow adipocytes and bariatric surgery–mediated bone loss

A distinct role for bone marrow adipocytes remains a possibility. VSG induces a major loss of bone marrow adipocyte populations, particularly from the so-called regulated BMAT and less so from the constitutive BMAT. BMAT is an important source of the insulin sensitizer adiponectin. Although bone marrow adipocyte loss was not observed in humans undergoing bariatric surgery (2), this could reflect less sensitive methodologies in human studies. Paradoxically, recent studies have demonstrated a crucial role for the expansion of marrow adipocytes during caloric restriction (18), potentially via BMAT-derived adiponectin. Thus, future studies examining the impact of bone marrow adipocytes in mediating the systemic metabolic and bone effects of bariatric surgery will be critical for our understanding of bariatric surgery.

Unanswered questions

While the data of Li et al. add much to our understanding, many questions remain. What mechanisms and tissues are responsible for increases in G-CSF after VSG? Are mechanisms underlying early post–bariatric surgery bone loss conserved from rodents to humans? Do these same mechanisms apply to osteoporosis occurring late after bariatric surgery in humans? What is the impact of vitamin D deficiency, which is common in obese individuals preoperatively and at late postoperative periods? Could tissue-level vitamin D deficiency or cellular resistance contribute to impaired osteoid formation in the early postoperative state? Since increased myeloid and reduced erythroid populations emerge in parallel after VSG, which of these play a primary pathogenic role?

In summary, the study by Li et al. adds to our understanding of the alterations in bone structure and function following VSG. Future studies are needed to define the molecular mediators of bone loss and marrow niche remodeling and to assess the contribution of BMAT to metabolic response to bariatric surgery. Further understanding of these factors will provide crucial information to guide optimal osteoporosis prevention and treatment strategies in this population. Moreover, identification of factors mediating metabolic improvement after bariatric surgery may aid in the design of bariatric mimetics for obesity and T2D.

Acknowledgments

MEP gratefully acknowledges research grant support from U01 DK114156 (ARMMS-T2D), R01 DK106193, R21 HD091974, and DRC P30 DK036836. SO gratefully acknowledges fellowship support from the Prince Mahidol Award Foundation under the Royal Patronage.

Version 1. 05/06/2019

Electronic publication

Version 2. 06/03/2019

Print issue publication

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: MEP reports investigator-initiated grant support from Janssen Pharmaceuticals and Xeris Pharmaceuticals, and pending patents related to hypoglycemia (PCT/US2017/045061 and patent application US20180353112A1).

Copyright: © 2019, American Society for Clinical Investigation.

Reference information: J Clin Invest. 2019;129(6):2184–2186. https://doi.org/10.1172/JCI128745.

See the related article at G-CSF partially mediates effects of sleeve gastrectomy on the bone marrow niche.

Contributor Information

Soravis Osataphan, Email: soravis.osataphan@joslin.harvard.edu.

Mary Elizabeth Patti, Email: mary.elizabeth.patti@joslin.harvard.edu.

References

- 1.Stein EM, Silverberg SJ. Bone loss after bariatric surgery: causes, consequences, and management. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2014;2(2):165–174. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(13)70183-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bredella MA, Greenblatt LB, Eajazi A, Torriani M, Yu EW. Effects of Roux-en-Y gastric bypass and sleeve gastrectomy on bone mineral density and marrow adipose tissue. Bone. 2017;95:85–90. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2016.11.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yu EW, et al. Effects of gastric bypass and gastric banding on bone remodeling in obese patients with type 2 diabetes. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2016;101(2):714–722. doi: 10.1210/jc.2015-3437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Li Z, et al. G-CSF partially mediates effects of sleeve gastrectomy on the bone marrow niche. J Clin Invest. 2019;129(6):2404–2416. doi: 10.1172/JCI126173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Scheller EL, Cawthorn WP, Burr AA, Horowitz MC, MacDougald OA. Marrow adipose tissue: trimming the fat. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2016;27(6):392–403. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2016.03.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Seeley RJ, Chambers AP, Sandoval DA. The role of gut adaptation in the potent effects of multiple bariatric surgeries on obesity and diabetes. Cell Metab. 2015;21(3):369–378. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2015.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wong IP, et al. Peptide YY regulates bone remodeling in mice: a link between gut and skeletal biology. PLoS ONE. 2012;7(7):e40038. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0040038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mahendran Y, et al. Association of ketone body levels with hyperglycemia and type 2 diabetes in 9,398 Finnish men. Diabetes. 2013;62(10):3618–3626. doi: 10.2337/db12-1363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Christensen MB, et al. Glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide (GIP) inhibits bone resorption independently of insulin and glycemia. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2018;103(1):288–294. doi: 10.1210/jc.2017-01949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ohlsson C, Sjögren K. Effects of the gut microbiota on bone mass. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2015;26(2):69–74. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2014.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Id Boufker H, et al. Role of farnesoid X receptor (FXR) in the process of differentiation of bone marrow stromal cells into osteoblasts. Bone. 2011;49(6):1219–1231. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2011.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cho SW, et al. Positive regulation of osteogenesis by bile acid through FXR. J Bone Miner Res. 2013;28(10):2109–2121. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.1961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lee YJ, et al. Association of circulating irisin concentrations with weight loss after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16(4):E660. doi: 10.3390/ijerph16040660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kim H, et al. Irisin mediates effects on bone and fat via αV integrin receptors. Cell. 2018;175(7):1756–1768.e17. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2018.10.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yamada M, Suzuki K, Kudo S, Totsuka M, Nakaji S, Sugawara K. Raised plasma G-CSF and IL-6 after exercise may play a role in neutrophil mobilization into the circulation. J Appl Physiol. 2002;92(5):1789–1794. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00629.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fulzele K, et al. Insulin receptor signaling in osteoblasts regulates postnatal bone acquisition and body composition. Cell. 2010;142(2):309–319. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ferron M, et al. Insulin signaling in osteoblasts integrates bone remodeling and energy metabolism. Cell. 2010;142(2):296–308. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cawthorn WP, et al. Bone marrow adipose tissue is an endocrine organ that contributes to increased circulating adiponectin during caloric restriction. Cell Metab. 2014;20(2):368–375. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2014.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]