Abstract

Background:

Cutaneous lupus erythematosus (CLE) is a potentially disfiguring, chronic autoimmune disease with extremely variable skin manifestations, negatively affecting quality of life (QoL) of patients. Patient-reported outcome (PRO) measures used in assessing QoL in CLE patients have been either generic or developed without input from patients with CLE.

Objectives:

To demonstrate the reliability and validity of a disease-specific QoL measure for CLE – the cutaneous lupus erythematosus quality of life (CLEQoL).

Methods:

A total of 101 patients with a clinical diagnosis of CLE were recruited, and each patient was asked to complete the CLEQoL. Internal consistency was used as a measure of reliability. Validity was measured in two ways – structural validity via exploratory factor analysis and convergent validity via Spearman correlations between CLEQoL and the Short Form 36 (SF-36). Patient demographic and disease characteristics were collected. Data was analyzed using SPSS and significance was set to p<0.05.

Results:

The average age of our CLE patients was 48±13 with discoid lupus (n=72, 71.3%) being the most predominant CLE subtype. Patients were mostly female (n=88, 87.1%) and African-American/Black (n=59, 58.4%). Internal consistency ranged from 0.67 to 0.97. A total of five domains, functioning, emotions, symptoms, body image/cosmetic effects and photosensitivity, were extracted with a total explained variance of 71.06%. CLEQoL-related domains correlated with SF-36 domains (r ranging from −0.39 to −0.65).

Conclusion:

The CLEQoL was found to be a valid and reliable PRO measure for assessing QoL in patients with CLE. Demonstrating that the CLEQoL has strong psychometric properties is an important step towards the development of a disease-specific PRO measure that future clinical trials can use.

Keywords: Cutaneous Lupus Erythematosus, Patient-Reported Outcomes, Quality of Life, Skindex, Psychometrics

INTRODUCTION

Cutaneous Lupus Erythematosus (CLE) is a chronic autoimmune disease that often manifests as photo-distributed lesions of various subtypes on the skin.1,2 CLE patients may have skin lesions as an isolated cutaneous manifestation or have systemic involvement with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE). While the pathophysiology of CLE is not fully understood, it is hypothesized that genetic, hormonal, immunological abnormalities, and environmental factors influence disease development and progression.3,4 Common symptoms often range from fatigue, pain, alopecia, to photosensitivity, all of which affect functional and emotional aspects of quality of life (QoL).5–7 Due to the subjective nature of CLE symptoms, it is beneficial to use patient-reported outcomes (PROs) correctly to assess disease progress and development.

PRO measures can either be generic or disease-specific, and allow for patients to directly report their health conditions without interpretation of their condition by a clinician, or third party.8 Generic measures are less suitable in identifying issues that are important to patients, especially with subjective symptoms as observed in CLE. Disease-specific measures, on the other hand, are specific to areas of interest (i.e., population, problem, domain or function),9,10 and are also more likely to be of clinical relevance.8

Currently, there are a limited number of PRO measures used in patients with CLE. Findings from a systematic review11 reported that the QoL instruments commonly used in CLE patients are Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI),12 Skindex-29,13 and Short Form 36 (SF-36),14 and Visual Analog Scale (VAS).6 However, because CLE patients were not involved in the development of these instruments,12 these measures may not capture all issues relevant to CLE. For example, the Skindex-29,13 a commonly used QoL questionnaire for skin diseases,1–3,7,15–18 lacks questions addressing concerns unique to patients with CLE such as avoidance of sun exposure. As a result, the cutaneous lupus erythematosus quality of life (CLEQoL) was developed to include additional CLE-specific domains like body image and photosensitivity, thanks to inputs from CLE patients via focus groups,19 and the Skindex-29+3, which contains three additional CLE-specific questions on photosensitivity and alopecia.2,3,15

Regardless of whether a PRO measure is generic or disease-specific, it must demonstrate satisfactory psychometric properties including reliability, responsiveness to changes (sensitivity), and validity in the measured domain.8 In order for CLE PRO measures to be used in future drug development and clinical trials, as well as in clinical practice, it is important to ensure its validity and reliability. Therefore, this study aimed to determine the reliability and validity of the CLEQoL.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Using a survey design, questionnaires were administered to a cohort of patients with CLE who were recruited in the outpatient dermatology clinics of University of Texas (UT) Southwestern Medical Center and Parkland Health and Hospital System from May 2016 to November 2017. All patients had a clinical diagnosis of CLE, were aged ≥ 18 years, and were able to understand written and spoken English. Informed consent was obtained from all study participants, and the study protocol was approved by the institutional review boards at The University of Texas (UT) at Austin (2015–09-0041) and UT Southwestern (STU 102015–056).

Instruments

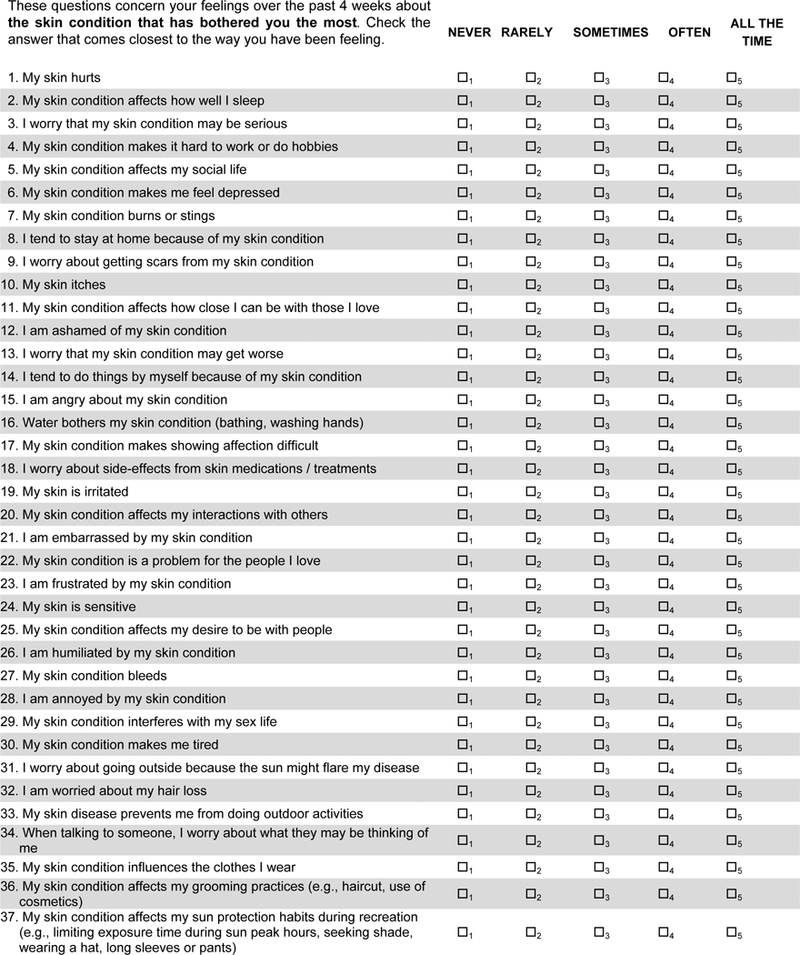

The cutaneous lupus erythematosus quality of life (CLEQoL) has 36 questions (Fig. 1); 29 questions from Skindex©, three additional lupus-specific questions (such as photosensitivity and alopecia) from the Skindex-29+32,3,15, and four questions from the vitiligo-specific quality of life (VitiQol)20 instrument that were validated via focus groups with CLE patients.15, 21 Permission to use and modify both Skindex and VitiQol was obtained from the original creators (MM Chren, RV Kundu) and distributors (Mapi Research Trust). Similar to the Skindex,13 the CLEQoL asks patients to assess how often (never, rarely, sometimes, often, all the time) they experienced a given effect. Then, scores of 0 (never), 25 (rarely), 50 (sometimes), 75 (often), and 100 (all the time) are assigned to each question. The scores are averaged per domain from the scale of 0–100, with higher numbers indicating worse quality of life.

Fig. 1.

The final CLE-specific quality of life measure – CLEQoL

The Short Form 36 (SF-36)14 is a generic QoL scale with 36 items and eight domains (physical functioning, role-physical, bodily pain, general health, vitality, social functioning, role-emotional, and mental health). Each subscale is transformed onto a 0–100 scale and converted into a norm-based score (using a mean of 50 and an SD of 10 for the U.S. general population). Two overall summary scores were obtained – Physical Component Summary (PCS) and Mental Component Summary score (MCS) scores. Summary scores were transformed to have a mean of 50 and standard deviation of 10, with higher scores indicating a higher QoL. The SF-36 has been used concurrently with the Skindex-29 and DLQI to examine QoL in CLE patients.2, 15, 22

Additional demographic and disease characteristics such as age, gender, educational level, race/ethnicity, marital status, disease duration, predominant CLE subtype, disease damage and activity (as measured by the Cutaneous Lupus Activity and Severity Index (CLASI)),21 and Visual Analog Scales (VAS)6 assessing pain,22 fatigue,23 and pruritus/itch,24 were collected from patients.

Data Analysis

Cronbach’s alpha (α),24 was used to assess the internal consistency of the CLEQoL,25 where an acceptable value of internal consistency was α ≥ 0.60.25 An exploratory factor analysis was conducted via a maximum likelihood test to examine the goodness-of-fit (structural validity) of the identified factor structure of the 36 items on the CLEQoL. The Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) test and Bartlett’s test of sphericity were used to check the adequacy of the study sample and the factor analysis model.26,27 KMO values <0.50 indicate that the data and sample are not adequate to conduct validity analyses. Therefore, a KMO >0.50 and p<0.05 was deemed significant for the Bartlett test of sphericity. The number of factors were determined based on eigenvalues >1, visual examination of the scree plot to determine the number of eigenvalues where the slope of the curve is leveling off (the “elbow”), and items with absolute loading values of 0.3.28 The final factors were extracted using principal axis factoring with Varimax rotations and were operationalized and descriptively labeled.

Convergent validity was determined by comparing similar domains on the CLEQoL with the SF-36 using the Spearman correlation coefficient (r). The Spearman correlation coefficient was interpreted as follows: r > 0.5, strong relationship; r = 0.35 to 0.5; moderate relationship, r = 0.1 to 0.3; weak relationship, and r < 0.1; none or very weak relationship.25,26 We also determined floor and ceiling effects. All statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS version 24.

RESULTS

A total of 101 patients were recruited into the study. Patient demographics and disease characteristics are detailed in Table 1. The average age of patients was 48±13 years, and the average disease duration was 10±11 years. The majority of the participants were female (n=88, 87.1%) and African-American (n=59, 58.4%). Most participants were single (n=42, 41.5%); had discoid lupus (n=72, 71.3%) and had college degrees (n=39; 38.6%). Floor and ceiling effects were determined by assessing the proportion of respondents with the highest or lowest possible value on the CLEQoL scale. These effects were considered present when more than 15% of the respondents show these values.27,28 There were no floor and ceiling effects.

Table 1:

Patient demographic and disease characteristics (N=101)

| Characteristics | Frequency (%) | Mean±SD |

|---|---|---|

| Age | 48±13 | |

| Gender | ||

| Female | 88 (87.1) | |

| Male | 13 (12.9) | |

| Educationa | ||

| Lower than High School | 15 (14.9) | |

| High School | 32 (31.7) | |

| College | 39 (38.6) | |

| Graduate Degree | 11 (10.9) | |

| Race | ||

| African-American/Black | 59 (58.4) | |

| Caucasian | 26 (25.7) | |

| Hispanic | 12 (11.9) | |

| Asian | 2 (2.0) | |

| Other | 2 (2.0) | |

| Marital Statusa | ||

| Single | 42 (41.6) | |

| Married/Domestic Partner | 39 (38.6) | |

| Divorced | 11 (10.9) | |

| Separated | 3 (3.0) | |

| Widow | 1 (1.0) | |

| Disease Duration (yrs.) | 10±11 | |

| PPredominant CLE Subtype | ||

| Chronic CLE | ||

| Discoid Lupus Erythematosus (DLE) | 72 (71.3) | |

| Tumid Lupus | 11 (10.9) | |

| Lupus Panniculitis | 1 (1.0) | |

| Subacute Lupus Erythematosus (SCLE) | 11 (10.9) | |

| Acute Lupus Erythematosus (ACLE) | 6 (5.9) | |

| CLASI Activity | 5.16±5.72 | |

| CLASI Damage | 7.95±6.72 | |

| Pain VASb | 3.23±3.51 | |

| Itch VASb | 3.61±3.47 | |

| Fatigue VASb | 5.11±3.45 |

Total does not equal 101 because of missing responses

VAS=Visual Analog Scale

Reliability

Cronbach’s alpha coefficient (α) was used as a measure of internal consistency of the items. The average item score corresponding to the domains on the scale and the Cronbach’s alpha values are presented in Table 2. The overall Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of the scale was 0.97, while the coefficient values of the subscales ranged from 0.67 to 0.95.

Table 2:

Reliability analyses of study scales (n=101)

| Scale | Number of Items | Mean±SD | Median | Cronbach’s Alpha |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CLEQoLa | 36 | |||

| Functioning | 12 | 29.32±27.37 | 22.92 | 0.95 |

| Emotions | 10 | 43.00±29.78 | 37.50 | 0.93 |

| Symptoms | 7 | 39.69±24.45 | 35.71 | 0.87 |

| Body image/cosmetic effects | 4 | 48.30±28.29 | 47.30 | 0.67 |

| Photosensitivity | 3 | 62.33±31.32 | 60.67 | 0.81 |

| Total | 36 | 39.06±25.11 | 0.97 |

Item 18 on side-effects of treatment is not scored nor included in the final CLEQoL scale

Validity

Structural Validity

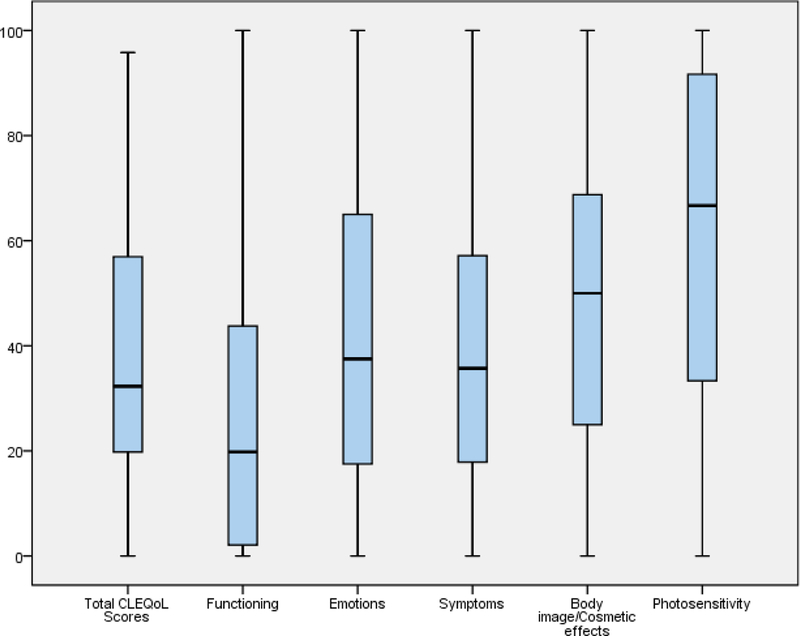

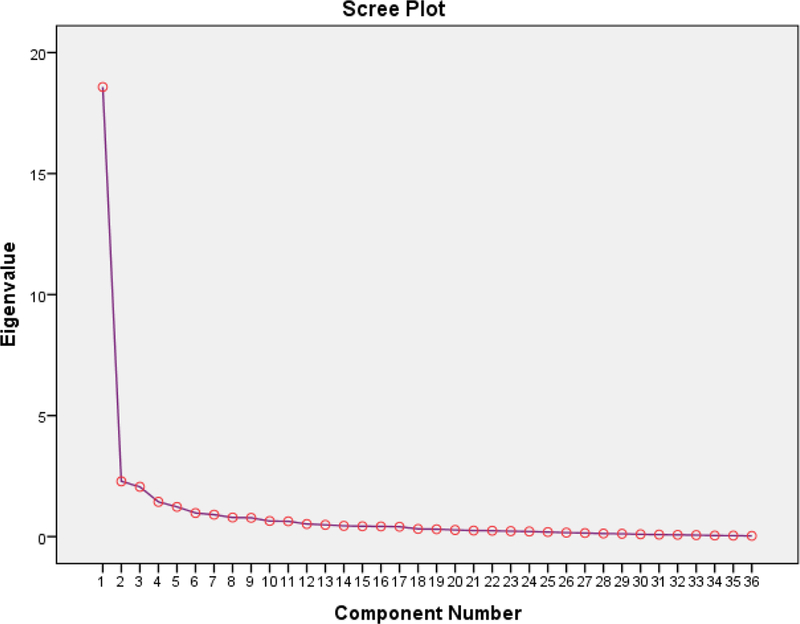

An exploratory factor analysis was conducted on the CLEQoL to determine its structural validity. The KMO value was 0.902 indicating that the data and sample were adequate for the factor analysis. In addition, the approximate Chi-square value of the Bartlett test of sphericity (χ2 = 3005.79, df = 630, p<0.001) confirmed that the factor model was appropriate. These two tests showed the suitability of the data for exploratory factor analysis. Principal component analysis and Varimax rotation were used for the exploratory factor analysis. Five factors/subscales were identified; three conformed to the initial subscales from the original Skindex, corresponding to symptoms, emotions, and functioning. Two additional contributions to these existing factors/subscales were body image/cosmetic effects and photosensitivity (Table 3). The distribution of the CLEQoL total scores and subdomains are shown in the box plot in Fig. 2. As shown in Table 3 and the scree plot (Fig. 3), the five factors that reported eigenvalues greater than 1, accounting for 71.06% of the variance, were extracted. Overall, the five subscales assessed overall QoL specific to CLE patients. The factor loadings, in bold font, of all items were significant and ranged from 0.42 to 0.85.

Table 3:

Exploratory factor loadings of items in the CLEQoL with five factors (n=101)

| Item No. |

Factors of CLEQoL subscales | Factor Loadings | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Factor 1 | Factor 2 | Factor 3 | Factor 4 | Factor 5 | ||

| Factor 1: Emotions (% of variance =51.60 Eigenvalue =18.58) | ||||||

| l. | I am ashamed of my skin condition | 0.53 | 0.19 | 0.20 | 0.07 | 0.21 |

| f. | My skin condition makes me feel depressed | 0.54 | 0.21 | 0.13 | 0.07 | 0.26 |

| u. | I am embarrassed by my skin condition. | 0.55 | 0.18 | 0.12 | 0.05 | 0.20 |

| bb. | I am annoyed by my skin condition | 0.69 | 0.19 | 0.16 | 0.28 | 0.19 |

| w. | I am frustrated by my skin condition | 0.52 | 0.17 | 0.21 | 0.13 | 0.19 |

| z. | I am humiliated by my skin condition | 0.74 | 0.11 | 0.35 | 0.12 | 0.13 |

| i. | I worry about getting scars from my skin condition | 0.49 | 0.26 | 0.11 | 0.19 | 0.17 |

| o. | I am angry about my skin condition. | 0.53 | 0.12 | 0.13 | −0.04 | 0.27 |

| c. | I worry tdat my skin condition may be serious | 0.71 | 0.13 | 0.26 | 0.20 | −0.06 |

| m. | I worry tdat my skin condition may get worse | 0.77 | 0.04 | 0.10 | 0.35 | 0.00 |

| Factor 2: Functioning (% of variance =6.34, Eigenvalue =2.28 ) | ||||||

| e. | My skin condition affects my social life | 0.15 | 0.59 | 0.10 | 0.05 | 0.20 |

| h. | I tend to stay at home because of my skin condition | 0.16 | 0.56 | 0.15 | 0.14 | 0.22 |

| q. | My skin condition makes showing affection difficult | 0.23 | 0.80 | 0.13 | 0.24 | 0.10 |

| y. | My skin condition affects my desire to be witd people | 0.23 | 0.85 | 0.20 | 0.22 | 0.13 |

| t. | My skin condition affects my interactions witd otders | 0.17 | 0.78 | 0.17 | 0.19 | 0.14 |

| cc. | My skin condition interferes witd my sex life | 0.13 | 0.66 | 0.13 | 0.06 | 0.15 |

| v. | My skin condition is a problem for tde people I love | 0.08 | 0.75 | 0.21 | 0.29 | −0.02 |

| k. | My skin condition affects how close I can be witd tdose I love | 0.23 | 0.71 | 0.19 | 0.21 | 0.11 |

| n. | I tend to do tdings by myself because of my skin condition | 0.18 | 0.58 | 0.29 | 0.12 | 0.15 |

| d. | My skin condition makes it hard to work or do hobbies | 0.23 | 0.42 | 0.24 | 0.38 | 0.21 |

| b. | My skin condition affects how well I sleep | 0.11 | 0.52 | 0.26 | 0.24 | 0.10 |

| dd. | My skin condition makes me tired | 0.12 | 0.55 | 0.19 | 0.12 | 0.24 |

| Factor 3: Symptoms (% of variance =5.71, Eigenvalue =2.06) | ||||||

| g. | My skin condition burns or stings | 0.19 | 0.20 | 0.61 | 0.12 | 0.28 |

| j. | My skin itches | 0.16 | 0.29 | 0.61 | 0.24 | 0.19 |

| x. | My skin is sensitive | 0.15 | 0.26 | 0.45 | 0.16 | 0.15 |

| a. | My skin hurts | 0.12 | 0.10 | 0.83 | 0.07 | 0.23 |

| p. | Water botders my skin condition (batding, washing hands) | 0.27 | 0.11 | 0.75 | 0.10 | −0.01 |

| aa. | My skin condition bleeds | 0.28 | 0.15 | 0.66 | −0.01 | 0.12 |

| s. | My skin is irritated | 0.18 | 0.27 | 0.50 | 0.22 | 0.09 |

| Factor 4: Body Image/Cosmetic Effects (% of variance =3.99, Eigenvalue =1.44) | ||||||

| hh. | When talking to someone, I sometimes worry about tdey may be tdinking of me | 0.11 | 0.09 | 0.07 | 0.74 | 0.16 |

| ff. | I am worried about my hair loss | 0.08 | 0.26 | 0.21 | 0.75 | −0.14 |

| ii. | My skin condition has influenced tde clotdes I wear. | 0.16 | 0.18 | 0.20 | 0.45 | 0.33 |

| jj. | My skin condition has affected my grooming practices (i.e., haircut, use of cosmetics) | 0.20 | 0.16 | 0.23 | 0.46 | 0.01 |

| Factor 5: Photosensitivity (% of variance =3.42, Eigenvalue = 1.23) | ||||||

| ee. | I worry about going outside because tde sun might flare my disease | 0.20 | 0.18 | 0.16 | 0.18 | 0.52 |

| gg. | My skin condition prevents me from doing outdoor activities. | 0.25 | 0.22 | 0.23 | 0.26 | 0.60 |

| kk. | My skin condition has affected my sun protection efforts during recreation | 0.14 | 0.11 | −0.02 | 0.21 | 0.74 |

Boldface factor loadings correspond to tde questions tdat are aligned witdin a particular factor

Fig. 2.

Boxplot for patients’ scores on the total CLEQoL scores and subdomains

Fig. 3.

Scree plot of the eigenvalues and number of factors in the CLEQoL scale

Convergent Validity

The domains of the CLEQoL were confirmed using the corresponding domains of the SF-36, VAS scales,22–24 and other clinical variables like the CLASI.21 The results demonstrated evidence of convergent validity when compared with corresponding domains on the SF-36 (Table 4). A medium-to-strong significant correlation was detected between the CLEQoL items and the equivalent SF-36 items as reported in Table 4. As expected, the functioning domain of the CLEQoL had good correlations with the physical functioning (r=−0.47, p <0.001), bodily pain (r=−0.45, p <0.001), role-physical (r=−0.39 p <0.001), and social functioning (r=−0.65, p <0.001) domains of the SF-36. The emotions domain of the CLEQoL correlated well with mental health (r=−0.57, p <0.001), role-emotional (r=−0.50, p <0.001), and vitality (r=−0.45, p <0.001) of the SF-36.

Table 4:

Convergent validity for similar domains in CLEQoL and SF-36 (n=101)

| CLEQoL | SF-36 | Pearson r |

|---|---|---|

| Functioning | Physical functioning | −0.47** |

| Bodily pain | −0.45** | |

| Role-physical | −0.39** | |

| Social functioning | −0.65** | |

| Emotions | Mental health | −0.57** |

| Role-emotional | −0.50** | |

| Vitality | −0.45** |

CLEQoL: Cutaneous lupus erythematosus quality of life scale; SF-36: Short Form 36;

p<0.001

CLASI activity correlated positively with the functioning (r=0.24 p <0.05), emotions (r=0.26, p <0.05), and symptoms (r=0.32 p <0.05) domains, while CLASI damage correlated positively with the body image/cosmetic effects (r=0.41 p <0.001) and photosensitivity (r=0.25 p <0.05). The three VAS measurements all correlated positively with the five CLEQoL domains (r=0.35–0.66, p<0.001) (Table 5).

Table 5:

Convergent validity for CLEQoL Domains and Clinical Variables (n=101)

| CLEQoL | CLASI Activity | CLASI Damage | Pain VAS | Itch VAS | Fatigue VAS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Functioning | 0.24* | 0.14 | 0.50** | 0.47** | 0.54** |

| Emotions | 0.26* | 0.13 | 0.37** | 0.42** | 0.47** |

| Symptoms | 0.32* | 0.24* | 0.65** | 0.66** | 0.55** |

| Body image/ cosmetic effects | 0.19 | 0.41** | 0.41** | 0.46** | 0.50** |

| Photosensitivity | 0.16 | 0.25* | 0.35** | 0.37** | 0.47** |

CLEQoL: Cutaneous lupus erythematosus quality of life scale; VAS: Visual Analog Scale;

p<0.05;

p<0.001

DISCUSSION

Having a disease-specific PRO measure to assess QoL in CLE, as demonstrated in the current study, is a relatively new effort and fills a critical gap in the literature. Before now, PRO measures currently used in assessing QoL in CLE were either generic2,15,22 or did not contain CLE-specific measures.12,13 The CLEQoL was therefore developed as a tool to capture the important and relevant domains important to CLE patients. In this study, we tested the reliability and validity of the CLEQoL in patients with CLE. We found that all domains of the CLEQoL had good internal consistency, indicating that the 36 items of the scale converge on the same construct. This acceptable reliability (as measured by internal consistency) of the CLE domains is similar to findings from the Skindex.13

The CLEQoL also demonstrated substantial structural and convergent validity. Regarding the structural validity of the CLEQoL (36 items), the cumulative variance explained by the five domains was 71.06% of the total variance of the scale. This is an acceptable threshold, as a scale should explain at least 50% of the total variance.29 An exploratory factor analysis, without fixing the number of factors to be extracted, was performed to determine the number of factors. According to the exploratory factor analysis, the CLEQoL was found to have five domains which are two more domains than the Skindex has. The first three factors, functioning (12 items), emotions (10 items), and symptoms (7 items) were in accordance with the Skindex.2,3,7,15,16,18 The additional two domains correspond to body image/cosmetic issues (4 items) and photosensitivity (3 items), which are CLE-specific attributes that have been reported to be important to patients in qualitative and cross-sectional studies.2,3,15,19 The CLEQoL was observed to exhibit acceptable convergent validity when compared with the generic QoL scale, the SF-36. The medium-to-strong significant correlations between the majority of the items in the CLEQoL and the corresponding SF-36 domains indicated acceptable convergent validity. Also, the negative correlations are expected given the difference between how the CLEQoL and SF-36 are scored.

Several limitations of this study must be considered. First, the collected data were based on self-reported questionnaires, which may be prone to recall bias that could affect the reliability of the responses. Then, the research design was cross-sectional which did not allow for estimating time-tested parameters and detection of responsiveness to change and minimal clinically important differences of the CLEQoL. As a result, we are planning future longitudinal studies to estimate these parameters. The inclusion and exclusion criteria used, while useful in delineating the study, might have limited the generalizability of our study findings to all CLE patients. For example, our study was conducted in one tertiary center, and thus future, larger studies that involve heterogeneous patients are required. Also, as a generic measure (SF-36) was compared with the disease-specific measure (CLEQoL), future studies could compare the CLEQoL with other dermatology measures. While the current study only employed exploratory factor analysis to determine the structural validity of the CLEQoL scale, future studies are needed to conduct confirmatory factor analysis via the use of structural equation model. These analyses can be used to test the relationship between observed variables and the underlying constructs or even test and compare the significance of the additional items on the CLEQoL with the original Skindex-29. The CLEQoL scale contains 36 items, which could present with response burden that might limit its routine use and feasibility in clinics and smaller research studies. As a result, future studies are needed for further refinement of the scale via item reduction techniques like the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve.29 Finally, discriminant validity, which could be used to discriminate CLE group with different disease activities and damage score (as measured by the CLASI) was not assessed in this study.

CONCLUSION

We have demonstrated strong reliability and validity of the disease-specific QoL PRO measure – CLEQoL. This study addresses a critical need in developing a CLE-specific PRO measure that adequately represents CLE patients’ perspectives on their skin disease. This is an important initial step in improving clinical trial designs in CLE where patients can provide sufficient input into which treatments work well.

What’s already known about this topic?

-

–

Cutaneous lupus erythematosus (CLE) negatively affects the quality of life (QoL) of patients.

-

–

Assessing QoL in patients with CLE have mostly entailed instruments that were not specific to CLE.

What does this study add?

-

–

The CLEQoL demonstrated sufficient reliability, structural and convergent validity in assessing QoL in CLE patients.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to thank Rebecca Vasquez, Elaine Kunzler, Stephanie Florez-Pollack, Danielle Lin, Jenny Raman, and Justin Raman for recruiting patients. The authors would like to thank Dr. M. Hung for her insights on psychometric analyses and participants of the UT Southwestern CLE Registry for their contributions to lupus research.

Funding: This study was supported in part by the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number K23AR061441. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center at Dallas and its affiliated academic and health care centers or the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: Dr. Chong is an investigator for Daavlin Corporation, Biogen Incorporated, and Pfizer Incorporated. He has received an honorarium from Celgene Corporation as a consultant.

REFERENCES

- 1.Gaines E, Bonilla-Martinez Z, Albrecht J, et al. Quality of life and disease severity in a cutaneous lupus erythematosus pilot study. Arch Dermatol. 2008;144(8):1061–1062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vasquez R, Wang D, Tran QP, et al. A multicentre, cross-sectional study on quality of life in patients with cutaneous lupus erythematosus. Br J Dermatol. 2013;168(1):145–153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Foering K, Goreshi R, Klein R, et al. Prevalence of self-report photosensitivity in cutaneous lupus erythematosus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;66(2):220–228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Panjwani S Early diagnosis and treatment of discoid lupus erythematosus. J Am Board Fam Med. 2009;22(2):206–213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Werth VP. Clinical manifestations of cutaneous lupus erythematosus. Autoimmun Rev. 2005;4(5):296–302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mendez-Flores S, Orozco-Topete R, Bermudez-Bermejo P, Hernandez-Molina G. Pain and pruritus in cutaneous lupus: their association with dermatologic quality of life and disease activity. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2013;31(6):940–942. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ishiguro M, Hashizume H, Ikeda T, Yamamoto Y, Furukawa F. Evaluation of the quality of life of lupus erythematosus patients with cutaneous lesions in Japan. Lupus. 2014;23(1):93–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Klassen AC, Smith KC, Shariff-Marco S, Juon HS. A healthy mistrust: how worldview relates to attitudes about breast cancer screening in a cross-sectional survey of low-income women. International Journal for Equity in Health. 2008;7:5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cramer JA, Spilker B. Quality of Life & Phamacoeconomics. An introduction. Lippincott-Raven; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Guyatt GH, Feeny DH, Patrick DL. Measuring health-related quality of life. Ann Intern Med. 1993;118(8):622–629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ogunsanya ME, Kalb SJ, Kabaria A, Chen S. A systematic review of patient-reported outcomes in patients with cutaneous lupus erythematosus. British Journal of Dermatology. 2017;176(1):52–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Finlay AY, Khan GK. Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI) - a simple practical measure for routine clinical use. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1994;19(3):210–216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chren MM, Lasek RJ, Quinn LM, Mostow EN, Zyzanski SJ. Skindex, a quality-of-life measure for patients with skin disease: reliability, validity, and responsiveness. J Invest Dermatol. 1996;107(5):707–713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ware JE Jr, Sherbourne CD. The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36): I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Medical Care. 1992:473–483. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Klein R, Moghadam-Kia S, Taylor L, et al. Quality of life in cutaneous lupus erythematosus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;64(5):849–858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Klein R, Moghadam-Kia S, LoMonico J, et al. Development of the CLASI as a tool to measure disease severity and responsiveness to therapy in cutaneous lupus erythematosus. Arch Dermatol. 2011;147(2):203–208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chang AY, Ghazi E, Okawa J, Werth VP. Quality of life differences between responders and nonresponders in the treatment of cutaneous lupus erythematosus. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149(1):104–106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Verma SM, Okawa J, Propert KJ, Werth VP. The impact of skin damage due to cutaneous lupus on quality of life. Br J Dermatol. 2014;170(2):315–321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ogunsanya ME, Brown CM, Lin D, Imarhia F, Maxey C, Chong BF. Understanding the Disease Burden and Unmet Needs among Patients with Cutaneous Lupus Erythematosus (CLE): A Qualitative Study. International Journal of Women’s Dermatology. 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lilly E, Lu PD, Borovicka JH, et al. Development and validation of a vitiligo-specific quality-of-life instrument (VitiQoL). J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69(1):e11–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Albrecht J, Taylor L, Berlin JA, et al. The CLASI (Cutaneous Lupus Erythematosus Disease Area and Severity Index): an outcome instrument for cutaneous lupus erythematosus. J Invest Dermatol. 2005;125(5):889–894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Farrar JT, Young JP, LaMoreaux L, Werth JL, Poole RM. Clinical importance of changes in chronic pain intensity measured on an 11-point numerical pain rating scale. Pain. 2001;94(2):149–158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Naegeli AN, Flood E, Tucker J, Devlen J, Edson‐Heredia E. The Worst Itch Numeric Rating Scale for patients with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis or psoriatic arthritis. International journal of dermatology. 2015;54(6):715–722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Naegeli AN, Flood E, Tucker J, Devlen J, Edson-Heredia E. The patient experience with fatigue and content validity of a measure to assess fatigue severity: qualitative research in patients with ankylosing spondylitis (AS). Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2013;11:192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Duruoz MT, Unal C, Toprak CS, et al. The validity and reliability of Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Quality of Life Questionnaire (L-QoL) in a Turkish population. Lupus. 2017;26(14):1528–1533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Conti F, Perricone C, Reboldi G, et al. Validation of a disease-specific health-related quality of life measure in adult Italian patients with systemic lupus erythematosus: LupusQoL-IT. Lupus. 2014;23(8):743–751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wamper KE, Sierevelt IN, Poolman RW, Bhandari M, Haverkamp D. The Harris hip score: Do ceiling effects limit its usefulness in orthopedics? Acta Orthop. 2010;81(6):703–707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Terwee CB, Bot SD, de Boer MR, et al. Quality criteria were proposed for measurement properties of health status questionnaires. 2007;60(1):34–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Koczkodaj WW, Kakiashvili T, Szymańska A, et al. How to reduce the number of rating scale items without predictability loss? Scientometrics. 2017;111(2):581–593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]