Abstract

Summary

In a population-based study of older Swedish women, we investigated the proportion of women treated with osteoporosis medication in relation to the proportion of women eligible for treatment according to national guidelines. We found that only a minority (22%) of those eligible for treatment were prescribed osteoporosis medication.

Introduction

Fracture rates increase markedly in old age and the incidence of hip fracture in Swedish women is among the highest in the world. Although effective pharmacological treatment is available, treatment rates remain low. Limited data are available regarding treatment rates in relation to fracture risk in a population-based setting in older women. Therefore, we aimed to investigate the proportion of older women eligible for treatment according to Swedish Osteoporosis Society (SvOS) guidelines.

Methods

A population-based study was performed in Gothenburg in 3028 older women (77.8 ± 1.6 years [mean ± SD]). Bone mineral density of the spine and hip was measured with dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry. Clinical risk factors for fracture and data regarding osteoporosis medication was collected with self-administered questionnaires. Logistic regression was used to evaluate whether the 10-year probability of sustaining a major osteoporotic fracture (FRAX-score) or its components predicted treatment with osteoporosis medication.

Results

For the 2983 women with complete data, 1107 (37%) women were eligible for treatment using SvOS criteria. The proportion of these women receiving treatment was 21.8%. For women eligible for treatment according to SvOS guidelines, strong predictors for receiving osteoporosis medication were glucocorticoid treatment (odds ratio (95% CI) 2.88 (1.80–4.59)) and prior fracture (2.58 (1.84–3.61)).

Conclusion

This study demonstrates that a substantial proportion of older Swedish women should be considered for osteoporosis medication given their high fracture risk, but that only a minority receives treatment.

Keywords: Bone fracture, Osteoporosis, Risk assessment, Therapeutics

Introduction

Osteoporosis is a disease characterized by low bone mineral density and structural decay, which increases the risk of fracture [1]. Fractures result in great patient suffering, negative effects on quality of life and increased mortality, especially after hip fracture, and high financial costs [2, 3]. In 2010, three and a half million osteoporosis-related fractures occurred in the EU at an annual cost of 37 billion euros [4]. The number of fractures is expected to rise and by 2025, the estimated number is four and a half million fractures to a cost of 46.8 billion euros annually [4]. Fracture rates increase markedly with age and the incidence of hip fracture in Swedish women is among the highest in the world [5]. Although effective pharmacological treatment is available [6], treatment rates in Sweden remain low even for older patients with prevalent fracture [7, 8]. Only limited data are available regarding treatment rates in relation to a thoroughly evaluated fracture risk in a population-based setting in older women [9].

Eligibility for treatment varies in different countries. Relevant criteria include the presence of osteoporosis at one or more densitometric site, prior fracture (particularly spine, hip, or multiple fractures), and high fracture probabilities. Irrespective of the criteria used, the uptake of bone-specific treatment is low [10, 11]. A large Danish register study found that only a small fraction of the expected number of women with osteoporosis were diagnosed and that very few women with fractures received osteoporosis medication after age 50 years [10, 11]. Studies from Germany and the US have shown that only 21.7% and 28.6% of patients with diagnosed osteoporosis received an osteoporosis medication, respectively [10, 11].

Common barriers for not being treated are fear of potential side effects, such as gastro-intestinal events [12], and rare side effects, such as atypical femur fractures and osteonecrosis of the jaw [13], as well as costs of osteoporosis evaluations and medications [14].

Factors associated with receiving osteoporosis medication are partly driven by characteristics such as a diagnosis of osteoporosis and osteopenia as well as hip, spine, and multiple fractures [15, 16].

The fracture risk calculation tool FRAX® is recommended in many clinical guidelines to calculate the absolute 10-year probability of major osteoporosis and hip fracture [17], based on clinical risk factors and bone mineral density (BMD) [18]. FRAX has been incorporated in the guidelines issued by the American National Osteoporosis Foundation (NOF), the National Osteoporosis Guideline Group (NOGG), and the Swedish Osteoporosis society (SvOS). The incorporation of FRAX into treatment guidelines emphasizes a substantial need for osteoporosis medication in the elderly, in whom a very small minority currently receives treatment in the United States (US) [19, 20].

The aim of this study was to investigate the proportion of older Swedish women eligible for treatment according to the SvOS guidelines, and to determine whether factors could be identified that predicted prescription of osteoporosis medication. As a sensitivity analysis, we also aimed to determine the treatment gap if the NOF and NOGG guidelines were to be applied to this Swedish population of older women.

Methods

Subjects

A population-based, prospective study (Sahlgrenska University hospital Prospective Evaluation of Risk of Bone fractures—The SUPERB study) was based in Gothenburg, Sweden. A national population register was used to identify women aged 75 to 80 years, living within the greater Gothenburg area. An initial manual screening was performed based on home address, to ensure that the participants were within the right age range and to exclude those residing in special housing. The inclusion and exclusion criteria have been described earlier [21, 22]. The study included 3028 elderly women. All women were first contacted by letter followed by telephone. The women eligible for the study were able to walk, with or without aid, sign an informed consent, and complete a questionnaire. To be able to include 3028 women, 6832 were contacted, of which 436 (6.4%) were excluded for reasons such as bilateral hip replacement, unable to communicate in Swedish, or not able to walk with or without a walking aid. Of all women contacted who met the inclusion criteria, 3368 (52.6%) declined to participate, giving an inclusion rate of 47.4%.

Anthropometrics

Body height, measured with a standardized wall-mounted stadiometer, was measured two consecutive times. If the two height measurements differed by ≥ 5 mm, a third measurement was performed. An average of the two height measurements, alternatively the two most similar measurements if three were obtained, was used. Body weight was measured to the nearest 0.1 kg using the same scale in all women.

Risk factors and FRAX-score calculation

Other clinical risk factors, such as medical history, fracture, living alone, level of education, falls the last 12 months, current smoking, parental history of hip fracture, oral glucocorticoids for 3 months or more with prednisolone 5 mg or equivalent, diabetes, rheumatoid arthritis, and high alcohol consumption were assessed by questionnaires. Self-reported fractures sustained after the age of 50 years and at any location, except the skull and face, were included in the FRAX-score calculations. Current smoking was defined by validated questionnaire [23]. A minority of participants (≈ 49; 1.6%) could not recall if any parent had sustained a hip fracture. In these cases, a null response was assumed. To define high alcohol consumption, a limit of 21 standard drinks per week was used [24]. Medical history including prior treatment for osteoporosis (current and previous use of oral bisphosphonates (ongoing or within 2 years), zoledronic acid (ongoing or within 3 years), denosumab (ongoing or within 1 year), and teriparatide) was assessed by questionnaires. Blood pressure was measured twice in the right arm and an average of the two measurements were used for both diastolic and systolic pressure. The 10-year probability for major osteoporotic fracture and hip fracture (FRAX) was calculated using the Swedish FRAX model with areal bone mineral density (aBMD) of the femoral neck together with all clinical risk factors except for secondary osteoporosis, which does not contribute to the calculation of fracture risk when aBMD is included.

Dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry

Areal BMD of the hip and spine was measured by dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA). One primary DXA-device, Hologic Discovery A (S/N 86491) (Waltham, MA, USA), was used to measure most participants (n = 2995). The National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) III reference database for femoral neck and total hip in 20–29 year old Caucasian women as well as the Hologic material for lumbar spine consisting of 30-year-old Caucasian American women were used to calculate the corresponding T-scores [25, 26]. Due to machine failure, a small proportion of women (n = 33) was measured with another Hologic Discovery A DXA device (Waltham, MA, USA). The potential discrepancy between the two machines was taken into account by performing a cross-calibration. This cross-calibration study consisted of 31 women aged 76.3 ± 0.9 years (only 30 women were available for the hip scan) measured with both machines within a period of median 7 days (interquartile range of 2.0–10.0 days for 31 individuals). Using a linear regression, with the alternative machine as independent variable and the study machine as dependent variable, a regression equation was generated. The regression coefficient and constant was 1.00 and 0.01 for femoral neck, 0.98 and 0.015 for total hip, and 1.021 and − 0.008 for lumbar spine. Variable-specific equation was further used to adjust all aBMD measurements obtained from the alternative machine.

Eligibility for treatment

NOF, NOGG, and SvOS guidelines were used to identify subjects who were eligible for treatment. SvOS criteria [27] included (1) previous hip or spine fracture, (2) osteoporosis, (3) low BMD (T-score ≤ − 2.0 SD), other (than spine or hip) prevalent fracture and a FRAX-score ≥ 20% for a MOF, or (4) 5 mg of daily oral glucocorticoid treatment > 3 months. NOF criteria [28] included (1) diagnosis of osteoporosis at the spine, femoral neck, or total hip, (2) osteopenia, in combination with a FRAX-score ≥ 20% for a MOF or ≥ 3% for a hip fracture, and (3) self-reported hip or spine fracture. NOGG criteria [29] included (1) prior fracture, (2) FRAX-score ≥ 20% for a MOF, or (3) ongoing glucocorticoid treatment with 7.5 mg or more.

Statistical analyses

NOF, NOGG, and SvOS guidelines were used to identify subjects who were eligible for treatment. Descriptive statistics were used to report the proportion of women who fulfilled the recommendations for treatment with regard to either NOF, NOGG, or SvOS guidelines. All analyses were cross-sectional. The means of continuous variables between groups were compared with an independent samples t test. A chi-square test was used to compare proportions. Backward stepwise logistic regression analysis was performed to investigate factors that were associated with receiving osteoporosis treatment. To evaluate these factors independently of each other, a multivariate analysis was made. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS (version 24, SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) and a p value below 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

Characteristics

This study included 2983 women with sufficient data to determine their eligibility for treatment with regard to either SvOS, NOF, or NOGG guidelines. Women eligible for treatment under either SvOS, NOF, or NOGG guidance were older, shorter, had lower body weight, higher prevalence of fracture, and lower BMD at the total hip and femoral neck than women ineligible for. Women eligible for treatment, using SvOS, NOF, and NOGG also had higher FRAX-scores for both major osteoporotic fracture and hip fracture. The proportion of current smokers were similar between the two groups defined by SvOS-criteria. In contrast, women eligible for treatment according to NOF and NOGG-criteria had a higher prevalence of smokers, while women without eligibility for treatment, in all three groups, had a higher proportion of diabetes (Table 1).

Table 1.

Cohort characteristics for women eligible for treatment according to SvOS, NOF and NOGG guidelines

| SvOS | NOF | NOGG | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Not eligible for treatment (n = 1876) | Eligible for treatment (n = 1107) | Not eligible for treatment (n = 572) | Eligible for treatment (n = 2411) | Not eligible for treatment (n = 1285) | Eligible for treatment (n = 1698) | |

| Age, years | 77.7 ± 1.6 | 78.0 ± 1.6c | 77.5 ± 1.6 | 77.8 ± 1.6c | 77.6 ± 1.6 | 77.9 ± 1.6c |

| Height, cm | 162.5 ± 5.7# | 160.8 ± 6.2£c | 163.4 ± 5.8€ | 161.5 ± 5.9$c | 162.4 ± 5.7‰ | 161.4 ± 6.0¢c |

| Weight, kg | 71.2 ± 12.1 | 64.6 ± 10.9c | 75.5 ± 13.0 | 67.1 ± 11.3c | 70.3 ± 12.4 | 67.6 ± 11.7c |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 27.0 ± 4.5 | 25.0 ± 4.0c | 28.3 ± 4.9 | 25.8 ± 4.1 | 26.7 ± 4.6 | 25.9 ± 4.2c |

| FRAX-score, MOF (%) | 18.0 ± 7.6 | 31.5 ± 12.8c | 12.4 ± 4.2 | 25.5 ± 11.6c | 14.0 ± 3.3 | 29.8 ± 11.4c |

| FRAX-score, HIP (%) | 7.2 ± 6.9 | 17.4 ± 13.6c | 3.0 ± 2.8 | 12.9 ± 11.4c | 4.4 ± 2.2 | 16.0 ± 12.4c |

| Prior fracture, n (%) | 420 (22.4) | 680 (61.4)c | 111 (19.4) | 989 (41.0)c | 0 (0) | 1100 (64.8)c |

| Rheumatoid arthritis, n (%) | 72 (3.8)† | 44 (4.0)¶ | 24 (4.2)€ | 92 (3.8)ø | 36 (2.8)¥ | 80 (4.7)∆b |

| Heredity of hip fracture, n (%) | 305 (16.3) | 211 (19.1) | 66 (11.5) | 450 (18.7)c | 51 (4.0) | 465 (27.4)c |

| Excessive alcohol consumption, n (%) | 8 (0.4) | 7 (0.6) | 4 (0.7) | 11 (0.5) | 4 (0.3) | 11 (0.6) |

| Current smoker, n (%) | 89 (4.7)Ω | 65 (5.9) | 20 (3.5) | 134 (5.6)∞a | 53 (4.1)‰ | 101 (5.9)a |

| Glucocorticoid treatment, n (%) | 0 (0.0) | 99 (8.9)c | 18 (3.1) | 81 (3.4) | 16 (1.2) | 83 (4.9)c |

| Diabetes, n (%) | 210 (11.2) | 81 (7.3)c | 76 (13.3) | 215 (8.9)b | 148 (11.5) | 143 (8.4)b |

| Femoral neck aBMD | 0.70 ± 0.09 | 0.59 ± 0.09c | 0.82 ± 0.07 | 0.62 ± 0.08c | 0.72 ± 0.10 | 0.62 ± 0.09c |

| T-score femoral neck | ||||||

| > −1.0 | 579 (30.9) | 64 (5.8) | 549 (96.0) | 94 (3.9) | 450 (35.0) | 193 (11.4) |

| − 1.0 to − 2.49 | 1297 (69.1) | 602 (54.4) | 23 (4.0) | 1876 (77.8) | 833 (64.8) | 1066 (62.8) |

| ≤ − 2.5 | 0 (0) | 441 (39.8) | 0 (0) | 441 (18.3) | 2 (0.2) | 439 (25.9) |

| Use of osteoporotic drug | ||||||

| Bisphosphonates, n (%) | 71 (3.8) | 215 (19.4) | 11 (1.9) | 275 (11.4) | 49 (17.1) | 237 (14.0) |

| Zoledronic acid, n (%) | 4 (0.2) | 19 (1.7) | 1 (0.2) | 22 (0.9) | 2 (0.2) | 21 (1.2) |

| Denosumab, n (%) | 1 (0.1) | 22 (2.0) | 0 (0) | 23 (1.0) | 2 (0.2) | 21 (1.2) |

Continuous variables are presented by mean ± SD and were compared by independent samples t test. Dichotomous variables are presented as number of subjects and percentage and differences were analyzed by the chi square test. Excessive alcohol consumption = 21 drinks or more per week. Glucocorticoid treatment = treatment with 5 mg per oral prednisolone or equal for more than 3 months, diabetes, defined by physician diagnosis

SvOS Swedish osteoporosis society guidelines, NOF National Osteoporosis Foundation, NOGG National Osteoporosis Guideline Group, SD standard deviation, aBMD areal bone mineral density, FRAX fracture risk assessment tool, MOF major osteoporotic fracture, HIP hip fracture. Each column presents the maximum number of participants and deviations are denoted for each variable by the following: ∞ = 2410, ø = 2408, $ = 2405, ¢ = 1692, Ω = 1875, # = 1874, † = 1873, ‰ = 1284, ¥ = 1283, ∆ = 1696, ¶ = 1106, £ = 1102, € = 571. A p value below 0.05 was considered significant

ap value < 0.05

bp value < 0.01

cp value < 0.001

Treatment gap

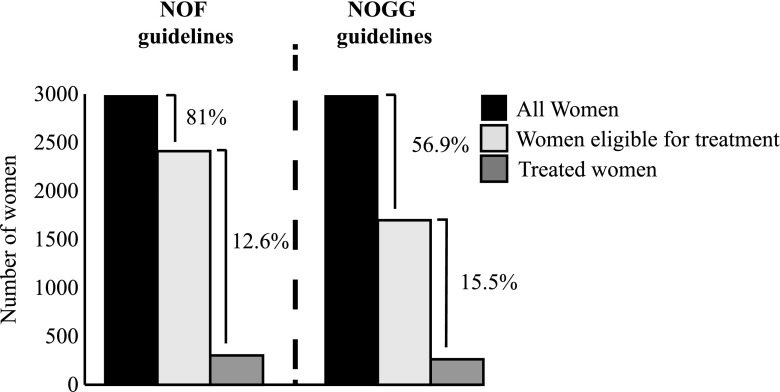

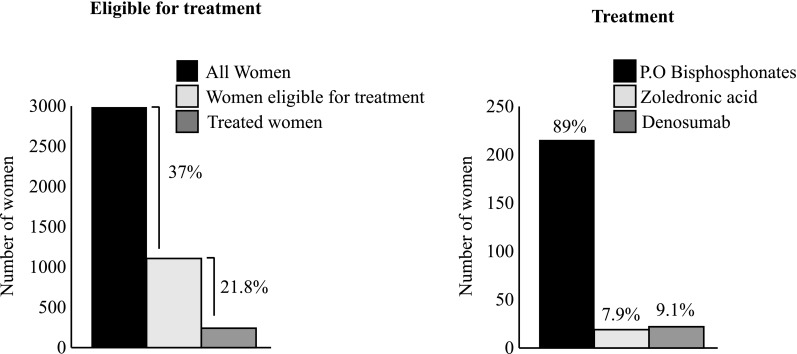

From the total cohort of 2983 women, 1107 (37%) women were eligible for treatment when applying the SvOS guidelines. For these women, only 241 (21.8%) had current or recent osteoporosis medication (Fig. 1). Of the treated women, the most common drugs were the oral bisphosphonates (89.2%), followed by denosumab (9.1%), and zoledronic acid (7.9%) (Fig. 1). From the included 2983 women studied, 2411 (81%) women were eligible for treatment when applying the NOF-guidelines. Of these women, only 303 (12.6%) had current or recent osteoporosis medication (Fig. 2). In the whole cohort, 1698 (56.9%) women were eligible for treatment when considering the NOGG guidelines. For these women, only 263 (15.5%) had current or recent osteoporosis medication (Fig. 2). Seventy-four (23.5%) women who were not eligible for treatment according to SvOS guidelines received osteoporosis medication.

Fig. 1.

Number of women eligible for treatment according to the Swedish Osteoporotic Society (SvOS) criteria and the proportions with current or recent treatment among women eligible for treatment (left panel). To the right, the type of osteoporosis medication used are presented for the treated women

Fig. 2.

Number and proportions of women eligible for treatment, according to the National Osteoporotic Foundation (NOF) and National Osteoporosis Guideline Group (NOGG), and women with actual current or recent treatment among women eligible for treatment. NOF and NOGG guidelines = subjects eligible for treatment as a result of fulfilling any of the NOF or NOGG treatment criteria, respectively

Variables associated with osteoporosis treatment

In the group of women eligible for treatment according to the SvOS guidelines (n = 1107), 241 (21.8%) women in total had reported current or recent osteoporosis treatment (Table 2). Women receiving treatment, more commonly had prior fractures, glucocorticoid treatment (in doses equal to or higher than 5 mg p.o. glucocorticoids for at least 3 months), and a higher FRAX-score for major osteoporotic fracture than controls. A smaller proportion of the treated women than the untreated women had high blood pressure (Table 2). Logistic regression was used to investigate which variables were associated with receiving osteoporosis medication within the SvOS-eligible women. In a univariate analysis, variables associated with increased odds ratio for osteoporosis treatment were prior fracture (OR 2.21, CI 1.61–3.06), glucocorticoid treatment (OR 2.13, CI 1.37–3.30), FRAX-score with BMD for major osteoporotic fracture (OR 1.02 per % increase, CI 1.00–1.03), and FRAX-score with BMD for hip fracture (OR 1.01 per % increase, CI 1.00–1.02) (Table 3). Characteristics associated with a decreased odds ratio of receiving osteoporosis medication was high blood pressure (OR 0.66 per mm/Hg increase, CI 0.49–0.88) (Table 3).

Table 2.

Characteristics of women eligible for treatment, according to SvOS guidelines, and women not eligible for treatment

| Women eligible for treatment | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | No osteoporosis treatment (n = 866) | Osteoporosis treatment (n = 241) | p |

| Age, years | 78.0 ± 1.64 | 78.0 ± 1.61 | 0.93 |

| Height, cm | 160.8 ± 6.06# | 160.7 ± 6.28€ | 0.86 |

| Weight, kg | 64.9 ± 10.8 | 63.7 ± 11.4 | 0.13 |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 25.1 ± 3.97 | 24.6 ± 3.98 | 0.10 |

| Level of education, n (%) | 660 (76.2) | 194 (80.5) | 0.16 |

| Living alone, n (%) | 456 (52.7) | 129 (53.5) | 0.81 |

| Diabetes, n (%) | 64 (7.4) | 17 (7.1) | 0.86 |

| Rheumatoid arthritis, n (%) | 37 (4.3)£ | 7 (2.9) | 0.34 |

| Obesity, n (%) | 89 (10.3) | 27 (11.2) | 0.68 |

| High blood pressure, n (%) | 521 (60.2) | 120 (49.8) | 0.004 |

| Excessive alcohol, n (%) | 5 (0.6) | 2 (0.8) | 0.66 |

| Current smoking, n (%) | 49 (5.7) | 16 (6.6) | 0.57 |

| Previous fall, n (%) | 259 (29.9) | 87 (36.1) | 0.07 |

| Prior fracture, n (%) | 345 (39.8) | 141 (58.5) | < 0.001 |

| Glucocorticoid treatment, n (%) | 64 (7.4) | 35 (14.5) | < 0.001 |

| FRAX-score, MOF (%) | 31.0 ± 12.3 | 33.5 ± 14.1 | 0.01 |

| FRAX-score, HIP (%) | 16.9 ± 13.0 | 19.0 ± 15.3 | 0.05 |

Continuous variables are presented by mean ± SD and were compared by independent samples t test. Dichotomous variables are presented as number of subjects and percentage and differences were analyzed by the chi square test. p values below 0.05 was considered significant and are presented in italic numbers. Obesity = BMI ≥ 30, high blood pressure = either ≥ 90 mmHg diastolic or ≥ 140 mmHg systolic blood pressure, excessive alcohol = 21 drinks or more per week, previous fall = experienced a fall the last 12 months, prior fracture = fracture after the age of 50 at all locations except skull, glucocorticoid treatment = treatment with 5 mg per oral prednisolone or equal for more than 3 months

SvOS Swedish osteoporosis society guidelines, SD standard deviation, FRAX fracture risk assessment tool, MOF major osteoporotic fracture, HIP hip fracture. Each column presents the maximum number of participants and deviations are denoted for each variable by the following: £ = 865, # = 862, € = 240

A p value below 0.05 was considered significant

Table 3.

Associations between anthropometrics, clinical risk factors, and current or recent osteoporosis treatment in women eligible for treatment, according to SvOS guidelines

| Variables | Crude OR | 95% CI | p | Adjusted OR | 95% CI | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 1.00 | 0.91–1.09 | 0.93 | 0.99 | 0.90–1.09 | 0.81 |

| Height | 1.00 | 1.00–1.00 | 0.86 | 1.00 | 1.00–1.00 | 0.26 |

| Weight | 0.99 | 0.98–1.00 | 0.13 | 1.17 | 0.96–1.43 | 0.13 |

| Body mass index | 0.97 | 0.93–1.01 | 0.10 | 0.93 | 0.88–0.98 | 0.01 |

| Level of education | 1.29 | 0.90–1.84 | 0.16 | 1.11 | 0.76–1.60 | 0.60 |

| Living alone | 1.04 | 0.78–1.38 | 0.81 | 0.99 | 0.73–1.34 | 0.94 |

| Diabetes | 0.95 | 0.55–1.66 | 0.86 | 0.93 | 0.52–1.65 | 0.80 |

| Rheumatoid arthritis | 0.67 | 0.30–1.52 | 0.34 | 0.50 | 0.20–1.25 | 0.14 |

| Obesity | 1.10 | 0.70–1.74 | 0.68 | 2.12 | 1.10–4.10 | 0.02 |

| High blood pressure | 0.66 | 0.49–0.88 | 0.004 | 0.67 | 0.50–0.90 | 0.01 |

| Excessive alcohol | 1.44 | 0.28–7.47 | 0.66 | 1.53 | 0.28–8.45 | 0.63 |

| Current smoking | 1.19 | 0.66–2.13 | 0.57 | 1.21 | 0.65–2.24 | 0.54 |

| Previous fall | 1.32 | 0.98–1.79 | 0.07 | 1.18 | 0.86–1.62 | 0.30 |

| Prior fracture | 2.21 | 1.61–3.06 | < 0.001 | 2.58 | 1.84–3.61 | < 0.001 |

| Glucocorticoid treatment | 2.13 | 1.37–3.30 | 0.01 | 2.88 | 1.80–4.59 | < 0.001 |

| FRAX-score | ||||||

| MOF | 1.02 | 1.00–1.03 | 0.01 | 1.02 | 1.00–1.03 | 0.01 |

| HIP | 1.01 | 1.00–1.02 | 0.03 | 1.01 | 1.00–1.02 | 0.03 |

Backward stepwise linear regression was used to investigate the associations between variables and current or recent osteoporosis treatment. The results are presented as odds ratios (OR) with corresponding 95% confidence interval (CI) for the final model and the last given result for variables being dropped from the model. The models investigating FRAX-scores were adjusted for variables not included in the calculation of the investigated score (i.e., level of education, living alone, obesity, high blood pressure, and previous fall). p values below 0.05 was considered significant and are presented in italic numbers. Crude = non-adjusted models, adjusted = models adjusted for all presented variables, obesity = BMI ≥ 30, high blood pressure = above either 90 mmHg diastolic or 140 mmHg systolic, excessive alcohol = 21 drinks or more per week, previous fall = experienced a fall the last 12 months, prior fracture = fracture after the age of 50 at all locations except skull, glucocorticoid treatment = treatment with 5 mg per oral prednisolone or equal for more than 3 months

MOF major osteoporotic fracture, HIP hip fracture

A p value below 0.05 was considered significant

With a backward stepwise regression model, including all variables except FRAX-score, the optimal model of predicting osteoporosis treatment was designed from the following variables: body mass index, obesity (BMI of 30 or over), high blood pressure, prior fracture, and glucocorticoid treatment (Table 3). The same method was used to evaluate the predictive ability of FRAX-score for either hip or major osteoporotic fracture independently of other covariates (i.e., level of education, living alone, obesity, high blood pressure, and prior falls). Together with high blood pressure, both hip and major osteoporotic FRAX-score were associated with receiving osteoporosis medication (Table 3).

Discussion

In this study, we report the existence of a large treatment gap among well characterized elderly Swedish women with a high fracture risk. As many as 1107 (37%) women were found to be eligible for treatment according to SvOS guidelines, but only 21.8% of these women had current or recent osteoporosis medication. Interestingly, as many as 74 women, not eligible for treatment according to SvOS guidelines, were treated despite being in the low-risk group. Factors associated with osteoporosis treatment were predominantly prior fracture and oral treatment with glucocorticoids but also high blood pressure, obesity, and body mass index.

The present study was designed to investigate different lifestyle factors (e.g., smoking, medications, and physical activity) and bone phenotypes’ association with incident fractures, therefore the ability to investigate osteoporosis prevalence might be limited. With a rather low inclusion rate (47.4%), which probably has resulted in inclusion of a healthier part of the population with a lower fracture risk, these findings might not be applicable to the general population of older women. To investigate the potential generalization of our findings, other clinical markers were used (e.g., blood pressure). Within this cohort (SUPERB), 1783 women (59.8%) were hypertensive defined as either having a systolic pressure above or equal to 140 mmHg or a diastolic pressure above or equal to 90 mmHg. The prevalence of hypertension found in SUPERB corresponds well to earlier presented data from a large population based study in Sweden, in which in total 60% of both men and women (age 45–73 years) and 54% for only women, were diagnosed with hypertension [30]. This finding indicates that the SUPERB population is representative of the general population.

Previously performed studies in Europe and in the US have been based on register data for prevalence of osteoporosis and osteoporosis medication [10, 11, 31], and were therefore not able to fully take all relevant clinical risk factors into account. Being able to take most relevant clinical risk factors into account, we found in the present study that the treatment gap, according to NOF guidelines, in our older Swedish women was similar or somewhat lower than what was previously reported in older women in the US [19, 20]. With the updated NOF guidelines [19], Donaldson et al. found that 93%, of the women aged 75 or older included in the study of osteoporotic fractures, and Berry et al. found that 86%, of women in the same age category participating in the Framingham study, would be eligible for treatment with the incorporation of FRAX into the NOF guidelines [19, 20]. However, there is a large variation in fracture risk between different regions of the world [5]. An Israeli study was able to investigate treatment eligibility using also common clinical risk factors. The proportion eligible for treatment using NOF guidelines was only 30.5% compared to the 81% rate observed in the present study. Such difference might be explained by the much higher fracture risk in Swedish elderly women compared to Israeli patients, a group consisting both of men and women with a wide age span from 50 to 90 years of age [32]. The much more treatment conservative SvOS guidelines identify women eligible for treatment at higher risk than the NOF and NOGG guidelines but result in a lower prevalence of women eligible for treatment. Thus, interventions in women according to SvOS vs. NOF or NOGG guidelines will likely result in larger absolute risk reductions in fractures, at the cost of failing to prevent fractures in women with intermediate risk according to SvOS guidelines. Based on the numbers of treatment eligible women and the FRAX hip fracture probabilities, the SvOS guidelines would only identify 193 hip fractures (17.4% FRAX hip fracture probability in 1107 women) while the NOGG guidelines would identify as many as 272 women with hip fractures (16.0% FRAX hip fracture probability in 1698 women).

The existing treatment gap has many potential explanations. To be able to increase the proportion of treated patients, we need a better understanding in which factors that are associated with increased probability of receiving osteoporosis medication. In a large population-based study, women were divided into high- and low-risk groups and different predictors of receiving treatment were investigated. For both groups, a self-reported diagnosis of osteoporosis followed by a self-reported diagnosis of osteopenia were the strongest predictors for treatment. In addition, the study looked at the proportion of treated women for each FRAX variable and compared to women without and found that women who had the most included FRAX risk factors were more likely to receive treatment [16]. However, a higher treatment rate in women with a higher prevalence of FRAX-included risk factors is somewhat expected. Therefore, we investigated different characteristics predictive value of receiving osteoporosis medication when competing with the actual FRAX-score as well as looking at all characteristics individually in a high-risk population-based study. Our results demonstrate that important risk factors for women to receive osteoporosis medication include prior fracture, previous or current treatment with glucocorticoids, and FRAX-scores for major osteoporotic and hip fracture.

The FRAX-score for a major osteoporotic or hip fracture is country specific, resulting in men and women, in different parts of the world (e.g., Sweden and USA), obtaining different FRAX-scores, even if the same risk factors are present. To evaluate potential undertreatment of Swedish elderly women with an American or British treatment definition could be questioned. The obtained fracture risk for the Swedish elderly women in the present study would have been lower if they had been analyzed using the US or UK FRAX calculators. However, these findings emphasize that an even larger proportion of the included Swedish women would have been recommended osteoporosis medication, if the lower treatment thresholds applied by NOF or NOGG would have been used also in Sweden.

This study has some limitations. Treatment with osteoporosis medication was assessed by questionnaire, which is limited by the patient’s recollection of treatment. Preferably, treatment for osteoporosis should have been obtained from the prescription registry. The present study was only performed on elderly women. Therefore, treatment eligibility cannot be presented for younger postmenopausal women or men. The FRAX calculator is a widely used web-based tool for fracture prediction and has been validated in several large cohorts. However, FRAX has some limitations, which include the inability to account for, e.g., falls risk, recency and number of prevalent fractures, dose of glucocorticoid treatment, alcohol, and smoking.

This study also has strengths. It is a population-based study in which we had information not only about the participating women’s skeletal phenotypes but also all other commonly used risk factors for fracture. Such information enables a comprehensive evaluation of fracture risk allowing a well-founded decision regarding treatment eligibility. The cohort (SUPERB) has a rather narrow age span (75–80 years), which enables us to visualize the critical situation close to the dramatic exponential increase in hip fracture risk, the fracture type that results in most patient suffering and highest societal costs, commonly seen after the age of 80 [33].

The present study is first to report of a substantial treatment gap in a well-characterized population of older Swedish women with high fracture risk. The probability to receive osteoporosis medication was higher in women with prior fracture or previous use of oral glucocorticoids.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflicts of interest

Professor Lorentzon has received lecture fees from Amgen, Lilly, Meda, Renapharma, UCB Pharma, and consulting fees from Amgen, Radius Health, UCB Pharma, Renapharma, and Consilient Health. Dr. Nilsson has received lecture fees from Shire and Pfizer. Professor Kanis reports grants from Amgen, Eli Lilly, and Radius Health; non-financial support from Medimaps, and Asahi; and other support from AgNovos. Professor Kanis is the architect of FRAX® but has no financial interest. All other authors state that they have no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.NIH Consensus Development Panel on Osteoporosis Prevention, Diagnosis, and Therapy (2001) Osteoporosis prevention, diagnosis, and therapy. JAMA 285:785–795

- 2.Wiktorowicz ME, Goeree R, Papaioannou A, Adachi JD, Papadimitropoulos E. Economic implications of hip fracture: health service use, institutional care and cost in Canada. Osteoporos Int. 2001;12:271–278. doi: 10.1007/s001980170116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sernbo I, Johnell O. Consequences of a hip fracture: a prospective study over 1 year. Osteoporos Int. 1993;3:148–153. doi: 10.1007/BF01623276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hernlund E, Svedbom A, Ivergard M, Compston J, Cooper C, Stenmark J, McCloskey EV, Jonsson B, Kanis JA. Osteoporosis in the European Union: medical management, epidemiology and economic burden. A report prepared in collaboration with the International Osteoporosis Foundation (IOF) and the European Federation of Pharmaceutical Industry Associations (EFPIA) Arch Osteoporos. 2013;8:136. doi: 10.1007/s11657-013-0136-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kanis JA, Oden A, McCloskey EV, Johansson H, Wahl DA, Cooper C, Epidemiology IOFWGo, Quality of L A systematic review of hip fracture incidence and probability of fracture worldwide. Osteoporos Int. 2012;23:2239–2256. doi: 10.1007/s00198-012-1964-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Svedbom A, Hernlund E, Ivergard M, Compston J, Cooper C, Stenmark J, McCloskey EV, Jonsson B, Kanis JA, IOF EURPo Osteoporosis in the European Union: a compendium of country-specific reports. Arch Osteoporos. 2013;8:137. doi: 10.1007/s11657-013-0137-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Johnell K, Fastbom J. Undertreatment of osteoporosis in the oldest old? A nationwide study of over 700,000 older people. Arch Osteoporos. 2009;4:17–23. doi: 10.1007/s11657-009-0022-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.SKL, Socialstyrelsen (2014) Jämförelser av hälso- och sjukvårdens kvalitet och effektivitet. https://www.socialstyrelsen.se/Lists/Artikelkatalog/Attachments/19604/2014-12-5.pdf

- 9.Kanis JA, Svedbom A, Harvey N, McCloskey EV. The osteoporosis treatment gap. J Bone Miner Res. 2014;29:1926–1928. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.2301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Haussler B, Gothe H, Gol D, Glaeske G, Pientka L, Felsenberg D. Epidemiology, treatment and costs of osteoporosis in Germany--the BoneEVA study. Osteoporos Int. 2007;18:77–84. doi: 10.1007/s00198-006-0206-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yang X, Sajjan S, Modi A. High rate of non-treatment among osteoporotic women enrolled in a US Medicare plan. Curr Med Res Opin. 2016;32:1849–1856. doi: 10.1080/03007995.2016.1211997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Siris ES, Yu J, Bognar K, DeKoven M, Shrestha A, Romley JA, Modi A. Undertreatment of osteoporosis and the role of gastrointestinal events among elderly osteoporotic women with Medicare Part D drug coverage. Clin Interv Aging. 2015;10:1813–1824. doi: 10.2147/CIA.S83488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jha S, Wang Z, Laucis N, Bhattacharyya T. Trends in media reports, oral bisphosphonate prescriptions, and hip fractures 1996-2012: an ecological analysis. J Bone Miner Res. 2015;30:2179–2187. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.2565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Simonelli C, Killeen K, Mehle S, Swanson L. Barriers to osteoporosis identification and treatment among primary care physicians and orthopedic surgeons. Mayo Clin Proc. 2002;77:334–338. doi: 10.4065/77.4.334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Greenspan SL, Wyman A, Hooven FH, Adami S, Gehlbach S, Anderson Jr FA, Boone S, Lacroix AZ, Lindsay R, Coen Netelenbos J, Pfeilschifter J, Silverman S, Siris ES, Watts NB. Predictors of treatment with osteoporosis medications after recent fragility fractures in a multinational cohort of postmenopausal women. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2012;60:455–461. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2011.03854.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Guggina P, Flahive J, Hooven FH, Watts NB, Siris ES, Silverman S, Roux C, Pfeilschifter J, Greenspan SL, Díez-Pérez A, Cooper C, Compston JE, Chapurlat R, Boonen S, Adachi JD, Anderson FA Jr, Gehlbach S, GLOW Investigators Characteristics associated with anti-osteoporosis medication use: data from the global longitudinal study of osteoporosis in women (GLOW) USA cohort. Bone. 2012;51:975–980. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2012.08.130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kanis JA, Harvey NC, Cooper C, Johansson H, Oden A, McCloskey EV, Advisory Board of the National Osteoporosis Guideline G A systematic review of intervention thresholds based on FRAX : a report prepared for the National Osteoporosis Guideline Group and the International Osteoporosis Foundation. Arch Osteoporos. 2016;11:25. doi: 10.1007/s11657-016-0278-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kanis JA, Hans D, Cooper C, et al. Interpretation and use of FRAX in clinical practice. Osteoporos Int. 2011;22:2395–2411. doi: 10.1007/s00198-011-1713-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Berry SD, Kiel DP, Donaldson MG, Cummings SR, Kanis JA, Johansson H, Samelson EJ. Application of the National Osteoporosis Foundation guidelines to postmenopausal women and men: the Framingham Osteoporosis Study. Osteoporos Int. 2010;21:53–60. doi: 10.1007/s00198-009-1127-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Donaldson MG, Cawthon PM, Lui LY, Schousboe JT, Ensrud KE, Taylor BC, Cauley JA, Hillier TA, Black DM, Bauer DC, Cummings SR, for the Study of Osteoporotic Fractures Estimates of the proportion of older white women who would be recommended for pharmacologic treatment by the new U.S. National Osteoporosis Foundation guidelines. J Bone Miner Res. 2009;24:675–680. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.081203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Larsson B, Mellstrom D, Johansson L, Nilsson AG, Lorentzon M, Sundh D. Normal bone microstructure and density but worse physical function in older women treated with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, a cross-sectional population-based study. Calcif Tissue Int. 2018;103:278–288. doi: 10.1007/s00223-018-0427-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nilsson AG, Sundh D, Johansson L, Nilsson M, Mellstrom D, Rudang R, Zoulakis M, Wallander M, Darelid A, Lorentzon M. Type 2 diabetes mellitus is associated with better bone microarchitecture but lower bone material strength and poorer physical function in elderly women: a population-based study. J Bone Miner Res. 2017;32:1062–1071. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.3057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vartiainen E, Seppala T, Lillsunde P, Puska P. Validation of self reported smoking by serum cotinine measurement in a community-based study. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2002;56:167–170. doi: 10.1136/jech.56.3.167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bergman H, Kallmen H. Alcohol use among Swedes and a psychometric evaluation of the alcohol use disorders identification test. Alcohol Alcohol. 2002;37:245–251. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/37.3.245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kelly T. Bone mineral reference databases for American men and women. J Bone Miner Res. 1990;5:S249. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Looker AC, Wahner HW, Dunn WL, Calvo MS, Harris TB, Heyse SP, Johnston CC, Jr, Lindsay R. Updated data on proximal femur bone mineral levels of US adults. Osteoporos Int. 1998;8:468–489. doi: 10.1007/s001980050093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Svenska osteoporossällskapet (SVOS) (2015) Nationella vårdprogram. http://www.svos.se/site/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/SVOS-vardprogram-osteoporos-2015-1.pdf. Accessed 5 July 2018

- 28.Cosman F, de Beur SJ, LeBoff MS, Lewiecki EM, Tanner B, Randall S, Lindsay R, National Osteoporosis F. Clinician's guide to prevention and treatment of osteoporosis. Osteoporos Int. 2014;25:2359–2381. doi: 10.1007/s00198-014-2794-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Compston J, Cooper A, Cooper C, et al. UK clinical guideline for the prevention and treatment of osteoporosis. Arch Osteoporos. 2017;12:43. doi: 10.1007/s11657-017-0324-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Li C, Engstrom G, Hedblad B, Berglund G, Janzon L. Blood pressure control and risk of stroke: a population-based prospective cohort study. Stroke. 2005;36:725–730. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000158925.12740.87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vestergaard P, Rejnmark L, Mosekilde L. Osteoporosis is markedly underdiagnosed: a nationwide study from Denmark. Osteoporos Int. 2005;16:134–141. doi: 10.1007/s00198-004-1680-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Goldshtein I, Ish-Shalom S, Leshno M. Impact of FRAX-based osteoporosis intervention using real world data. Bone. 2017;103:318–324. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2017.07.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.U.S. Congress OoTA . Hip Fracture Outcomes in people age 50 and over-background paper, OTA-BP-H- 120. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office; 1994. [Google Scholar]