Abstract

Purpose

Prostate-specific membrane antigen (PSMA) and gastrin-releasing peptide receptor (GRP-R) are expressed in prostate cancer and can be targeted with radiolabeled inhibitors and antagonists. Their performances for the initial characterization of prostatic tumors have been barely evaluated but never compared. We aimed to gather comparative preclinical data of the role of PSMA and GRP-R targeting in prostate cancer.

Procedures

We retrospectively studied 20 frozen prostatectomy samples with various metastatic risks of the D’Amico classification. Tissue samples were investigated by tissular microimaging using the radiolabeled PSMA inhibitor 111In-PSMA-617 and the radiolabeled GRP-R antagonist 111In-RM2. Bindings of the two radiopharmaceuticals were compared to histology and clinico-biological data (Gleason score, PSA values, metastatic risks).

Results

Binding of 111In-PSMA-617 was high whatever the metastatic risk (p = 0.665), Gleason score (p = 0.555), or PSA value (p = 0.404) while 111In-RM2 exhibited a significantly higher binding in the low metastatic risk group (p = 0.046), in the low PSA value group (p = 0.001), and in samples with Gleason 6 score (p = 0.006).

Conclusion

PSMA and GRP-R based imaging might have complementary performances for the initial characterization of prostatic tumors. Prospective clinical studies comparing the two tracers in this setting are needed.

Keywords: Prostate cancer, PSMA, GRP-R

Introduction

Prostate cancer is the most common cancer in men and the third cause of cancer deaths [1]. It is also a multifocal disease as cancerous cells may arise from different locations within the prostatic gland. Thus, prostate cancer is a combination of different cancerous cells with their own metastatic risks. Prostate cancer classification, prognosis, and management are today based on the two major cell populations (Gleason score). Beside primary staging which includes multi parametric pelvic magnetic resonance imaging (mpMRI), thoraco-abdomino-pelvic computed tomography (CT), and bone scintigraphy, only 18F-Choline positron emission tomography/computed tomography (PET/CT) may be proposed to some patients with high metastatic risk but it has a low accuracy for detection of primary prostate cancer [2].

Attractive targets for a more specific and sensitive imaging of primary prostate cancer are the prostate-specific membrane antigen (PSMA) and the gastrin-releasing peptide receptor (GRP-R). They can be effectively targeted with radiolabeled inhibitors [3] and antagonists [4], respectively.

Prostate-specific membrane antigen (PSMA) is a type 2 glycoprotein expressed in secretory cells of prostatic epithelium. Several radiolabeled PSMA inhibitors have been developed for imaging (68Ga-PSMA-11, 68Ga-PSMA-617, 68Ga-PSMA I&T, or 18F-PSMA1007 [5]). Uptake of radiolabeled PSMA inhibitors correlates well with Gleason score (GS) and PSA level [6] indicating a role for this imaging procedure in high-risk prostate cancer.

The gastrin-releasing peptide receptor (GRP-R) is a G-protein-coupled receptor of the bombesin receptor family [7] which can be targeted with radiolabeled antagonists such as 68Ga-RM2 [8], 68Ga-NeoBOMB1 [9], or 68Ga-RM26 [10] for PET imaging. Contrarily to PSMA, GRP-R is overexpressed in low-risk prostate cancers (low Gleason score, low PSA value, and low tumor size) [11, 12]. A study of initial staging of prostate cancer on 14 patients observed a detection rate of 83%, a sensitivity of 89%, and a specificity of 81% [8].

Although few pilot clinical studies targeting PSMA or GRP-R for initial staging of prostate cancer suggest a complementary role of these imaging procedures, there have never been compared in the same patients. Therefore, in this preclinical work, we aimed to compare PSMA and GRP-R expression on the same histological samples of prostate tumors using radiolabeled probes.

Material and method

Patient characteristics

Twenty frozen samples of prostate cancer were available from the Department of Pathology of University Hospital of Toulouse, France. Patient samples were obtained after informed consent in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and stored at the “CRB Cancer des Hôpitaux de Toulouse (BB-0033-00014)” collection. According to the French law, CRB Cancer collection has been declared to the Ministry of Higher Education and Research (DC-2008-463) and obtained a transfer agreement (AC-2013-1955) after approbation by ethical committees (Conseil Scientifique du Centre de Ressources Biologiques). Clinical and biological annotations of the samples have been declared to CNIL (Comité National Informatique et Libertés). Sample characteristics’ are presented in Table 1. No patient had received neoadjuvant hormone therapy or chemotherapy. For each case, five adjacent sections were used: one for Hematoxylin-Eosin-Saffron (HES) staining and four for high-resolution microimaging (one section per radiopharmaceutical for total binding and another one for non-specific binding). An experienced pathologist manually drew tumoral areas on the HES-stained section. All patients were classified according to their metastatic risk, following the D’Amico classification [13], using clinical and biochemical criteria including tumoral size, PSA value, and Gleason score.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the patients from which samples have been used in this study. nd not determined, PSA prostate-specific antigen

| Patients | Age | Gleason score | PSA (ng/mL) | Clinical tumoral size: cT | Pathological tumoral size: pT | Metastatic risk |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 65 | 6 (3 + 3) | 3.7 | 1 | 2c | Low risk |

| 2 | 57 | 6 (3 + 3) | 4.38 | 1 | 2 | |

| 3 | 51 | 6 (3 + 3) | 3.7 | 2 | 2 | |

| 4 | 49 | 6 (3 + 3) | 4.52 | 2 | 2c | |

| 5 | 56 | 6 (3 + 3) | 4.4 | 2 | 2c | |

| 6 | 63 | 7 (3 + 4) | 10 | 1 | 2c | Intermediate risk |

| 7 | 66 | 7 (3 + 4) | 10 | 2 | 2c | |

| 8 | 59 | 7 (3 + 4) | 13 | 2 | 2b | |

| 9 | 67 | 7 (3 + 4) | 12.5 | 1 | 3a | |

| 10 | 67 | 7 (3 + 4) | 14 | 1 | 3a | |

| 11 | 66 | 7 (3 + 4) | 10.4 | 0 | 3a | |

| 12 | 55 | 7 (3 + 4) | 13 | 1 | 3a | |

| 13 | 56 | 9 (4 + 5) | 26 | 3 | 3a | High risk |

| 14 | 63 | 7 (4 + 3) | 25.6 | 3 | 3b | |

| 15 | 70 | 9 (4 + 5) | 24.5 | 2 | 3b | |

| 16 | 59 | 8 (4 + 4) | 14 | 2 | 4 | |

| 17 | 48 | 7 (4 + 3) | 14.28 | 2 | 3b | |

| 18 | 66 | 7 (4 + 3) | 44 | 2 | 3a | |

| 19 | 53 | 7 (4 + 3) | 20 | 2 | 3a | |

| 20 | 63 | 7 (4 + 3) | 28 | 2 | nd |

Radiosynthesis and quality controls of 111In-RM2 and 111In-PSMA-617

PSMA-617 and RM2 were radiolabeled with 111In using an automated synthesizer (GE FastLab, GE Healthcare, GEMS Benelux, Belgium). Briefly, 40 μg of RM2 (Life Molecular Imaging) or PSMA-617 (ABX GmBH) was heated at 90 °C for 5 min using microwaves or 111InCl3 (CURIUM®) and 5 mg of ascorbic acid for RM2. The raw solution was then purified on a C18 cartridge (WAT023501) preconditioned with 1 mL ethanol (Merck®) and 5 mL water (GE®). The final product was then eluted with 1 mL ethanol and formulated in PBS. 111In-RM2 and 111In-PSMA-617 were checked for radiochemical purity and amount using radio-UV-HPLC (Phenomenex Luna C18; 250 mm × 4.6 mm × 5 μm; 2.5 mL/min, λ = 220 nm; eluent A comprising 0.1% TFA in water, eluent B comprising acetonitrile; gradient 0–10 min, 95% to 5% A). The analytical HPLC system used was a JASCO system with ChromNAV software, a PU-2089 Plus quaternary gradient pump, a MD-2018 Plus photodiode array detector, and Raytest Gabi Star detector.

High-resolution microimaging

Binding assay

Protocol edited by Reubi and co-workers for binding assays was strictly adhered [14]. Frozen samples were kept at − 80 °C. Three days before handling, samples were placed at − 20 °C. The day of the experiment, samples were pre-incubated for 10 min at 37 °C in Tris-HCl buffer at pH 7.4. A hydrophobic pen was used to surround the sample. Then, binding solution containing 10 nM (0.01–0.2 MBq) of 111In-RM2 (IC50 = 9.3 ± 3.3 nM on the GRP-R) [15] or 10 nM (0.03–0.06 MBq) of 111In-PSMA-617 (Kd = 5.4 ± 0.8 nM on the PSMA) [16] in Tris-HCl buffer at pH 8.2, 1% of BSA (Sigma®A2153), 40 μg/mL of bacitracin (Sigma®11,702), and 10 nM of MgCl2 (Sigma®M8266) was applied (ethanol content for 111In-RM2 was 0.003 ± 0.002% and 0.0009 ± 0.0008% for 111In-PSMA-617). For non-specific binding, 1 μM of natGa-labeled RM2 or natGa-PSMA-617 was added to determine non-specific binding (natIn-RM2 and natIn-PSMA-617 were not available to us, we used natGa-RM2 and natGa-PSMA-617 which also bind with high affinity to GRP-R and PSMA, respectively). IC50 of Ga-RM2 for GRP-R is below 0.1 nM and Ki of Ga-PSMA-617 for PSMA is 6.40 ± 1.02 nM [17, 18]. Samples were incubated at 37 °C for 2 h. Afterward, samples were rinsed five times for 8 min in cold Tris-HCl buffer at pH 8.2 with 0.25% of BSA, two times for 8 min in cold Tris-HCl buffer at pH 8.2 without BSA and finally two times for 5 min in distilled water.

Tissular microimaging

Beta Imager-2000 (Biospace Lab) device was used to image and quantify radioactivity in the sample. Then, a Micro Imager (Biospace Lab) was used to obtain high-resolution images (radioactive and optical). Acquisition duration was about 20 h for the Beta Imager 2000 (4 × 106 counts) and 15 h for the Micro Imager.

Data analysis

Imaging analysis was performed as previously described [19].

Statistical analysis

Data, presented as the mean ± standard deviation (SD), were compared using non-parametric t test (Wilcoxon test) and non-parametric one-way ANOVA (Kruskal-Wallis test). Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad software (v 6.01, San Diego, USA). p values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Radiosynthesis and quality controls of 111In-RM2 and 111In-PSMA-617

111In-RM2 was produced with a radiolabeling yield of 78.5 ± 4.6%, radiochemical purity of 99.9 ± 0.2%, and specific activity of 1.4 ± 0.4 GBq/μmol. 111In-PSMA-617 was produced with a radiolabeling yield of 85.6 ± 0.2%, radiochemical purity of 100.0 ± 0.0%, and specific activity of 2.2 ± 0.5 GBq/μmol. Both radiopharmaceuticals are stable in PBS up to 4 h.

High-resolution microimaging (HRMI)

Qualitative analysis

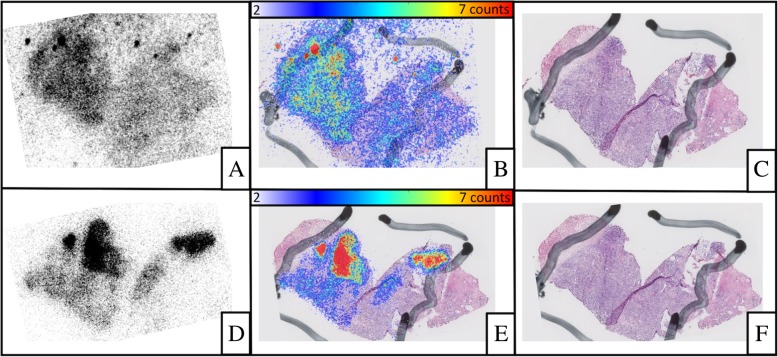

Both radiopharmaceuticals were easily detectable, without excessive noise. As shown in Fig. 1, on samples from low metastatic risk tumors, discrimination between tumoral tissues and normal tissues was good with both 111In-RM2 and 111In-PSMA-617. On high metastatic risk samples, signal-to-noise ratio was higher with 111In-PSMA-617 (Fig. 2).

Fig. 1.

Comparison between 111In-RM2 (a–c) and 111In-PSMA (d–f) on a low-risk sample: radioactive signal (a, d), HES (c, f), and fusion images (b, e). The black line drawing corresponds to the tumoral area. There is good discrimination between tumor tissue and normal tissue on 111In-RM2 (tumor-to-normal ratio, TNR = 1.22) as well as on 111In-PSMA-617 (TNR = 2.09)

Fig. 2.

Comparison between 111In-RM2 (a–c) and 111In-PSMA (d–f) on a high-risk sample: radioactive signal (a, d), HES (c, f), and fusion images (b, e). The black line delimitation corresponds to the tumoral area. There is excellent discrimination between tumor tissue and normal tissue on 111In-PSMA-617 (TNR = 11.20), while the contrast is somewhat lower with 111In-RM2 (TNR = 1.21)

Quantitative analysis

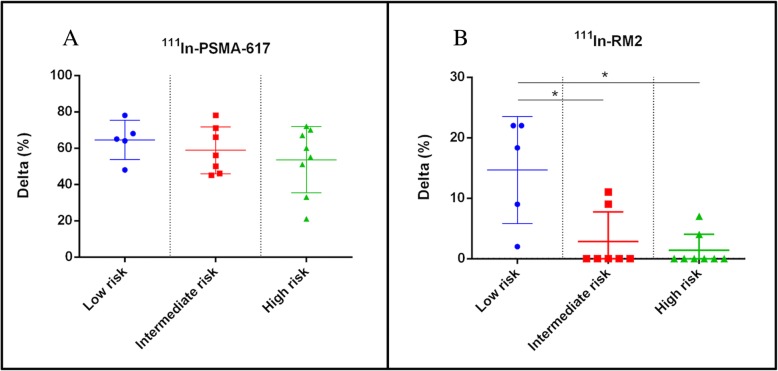

111In-RM2: The binding intensity of 111In-RM2 and the impact of biological, pathological, and clinical parameters are shown in Table 2. 111In-RM2 binding was higher in pT2 tumors compared to pT3/pT4 tumors but not significantly (9.17 ± 2.17% vs 2.82 ± 1.28%; p = 0.161). 111In-RM2 showed a significantly higher specific binding in Gleason 6 samples (Gleason 6, 14.67 ± 3.96%; Gleason 7, 2.58 ± 1.19%; Gleason 8–9, 1.33 ± 1.33%; p = 0.0061). 111In-RM2 also showed a significantly higher binding in tumors from patients with PSA < 10 ng/mL compared to patients with PSA values ≥ 10 ng/mL (14.67 ± 3.96% vs 2.07 ± 0.98; p = 0.0012). The differences in 111In-RM2 binding between low- and intermediate- or high-risk patients were also significant with higher specific binding in low metastatic group (low, 14.67 ± 3.96%; intermediate, 2.86 ± 1.86%; high, 1.38 ± 0.94%; p = 0.046) (Table 2 and Fig. 3).

Table 2.

Statistical analysis of 111In-PSMA-617 and 111In-RM2 bindings according to clinico-biological parameters (pathological size, Gleason score, prostate-specific antigen (PSA) value, and metastatic risk). Non-parametric one-way ANOVA (Kruskal-Wallis test) and non-parametric t test (Wilcoxon test). p < 0.05 was considered significant

| Biological parameters | n | 111In-PSMA-617 | 111In-RM2 | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pathological size | ||||

| pT2 | 8 | 66.00 ± 3.65% | 9.17 ± 2.17% | 0.0078 |

| pT3&4 | 11 | 54.82 ± 4.45% | 2.82 ± 1.28% | 0.0010 |

| p value | 0.105 | 0.161 | ||

| Gleason score | ||||

| 6 | 5 | 64.60 ± 4.83% | 14.67 ± 3.96% | 0.0625 |

| 7 | 12 | 54.50 ± 4.87% | 2.58 ± 1.19% | 0.0005 |

| 8–9 | 3 | 62.33 ± 8.73% | 0.0 ± 0.0% | 0.0065 |

| p value | 0.5554 | 0.0019 | ||

| PSA value | ||||

| < 10 ng/mL | 5 | 64.60 ± 4.83% | 14.67 ± 3.96% | 0.0625 |

| ≥ 10 ng/mL | 15 | 56.07 ± 4.04% | 2.07 ± 0.98% | < 0.0001 |

| p value | 0.404 | 0.0012 | ||

| Metastatic risk | ||||

| Low | 5 | 64.60 ± 4.83% | 14.67 ± 3.96% | 0.0625 |

| Intermediate | 7 | 58.86 ± 4.90% | 2.86 ± 1.86% | 0.0156 |

| High | 8 | 53.63 ± 6.44% | 1.38 ± 0.94% | 0.0078 |

| p value | 0.665 | 0.0046 | ||

| Total | 20 | 58.2 ± 14.82% | 5.2 ± 7.65% | < 0.0001 |

Fig. 3.

a 111In-RM2 binding in low-, intermediate-, and high-risk prostate cancer samples. 111In-RM2 binding is significantly higher in low metastatic risk compared to intermediate- or high-risk samples. b 111In-PSMA-617 binding in low-, intermediate-, and high-risk prostate cancer samples. Binding of 111In-PSMA-617 is high in all samples with no significant differences between groups. Non-parametric one-way ANOVA (Kruskal-Wallis test). p < 0.05 was considered significant

111In-PSMA-617

The binding intensity of 111In-PSMA-617 and the impact of biological pathological and clinical parameters are shown in Table 2. There was no significant difference in 111In-PSMA-617 binding intensity between groups, whether considering pT stage (pT2 vs pT3/pT4; p = 0.105), Gleason score (Gleason 6, 64.60 ± 4.83%; Gleason 7, 54.50 ± 4.87%; Gleason 8–9, 62.33 ± 5.04%; p = 0.5554), or PSA value < 10 ng/mL or ≥ 10 (64.60 ± 4.83,vs 56.07 ± 4.04%; p = 0.404). Again, the differences in binding between low- and intermediate- or high-risk patients were not significant (low metastatic risk, 64.60 ± 4.83%; intermediate metastatic risk, 58.86 ± 4.90%; high metastatic risk, 53.63 ± 6.44%; p = 0.665) (Table 2 and Fig. 3).

Comparison of binding intensity between 111In-PSMA-617 and 111In-RM2 according to the clinical, pathological, and biological parameters

In pT2 tumors and pT3/pT4 tumors, 111In-PSMA-617 binding was higher than 111In-RM2 (p = 0.0078 and p = 0.001, respectively). In the low PSA group, there was only a trend for higher 111In-PSMA-617 binding compared to 111In-RM2 (64.60 ± 4.83% vs 14.67 ± 3.96%, p = 0.0625). However, in the high PSA value group, 111In-PSMA-617 binding was significantly higher than 111In-RM2 (respectively, 56.07 ± 4.04% vs 2.07 ± 0.98%; p < 0.0001). There was no significant difference between the two radiopharmaceuticals in Gleason 6 score. However, in the Gleason 7 group, 111In-PSMA-617 was significantly higher than 111In-RM2 (54.50 ± 4.87% vs 2.58 ± 1.19%; p = 0.005). This was also the case for the few samples with Gleason 8–9 (p = 0.0065). 111In-PSMA-617 binding was significantly higher than 111In-RM2 binding in intermediate and high metastatic risk groups (58.86 ± 4.90% vs 2.86 ± 1.86%; p = 0.0156 and 53.63 ± 6.44% vs 1.38 ± 0.94%; p = 0.0078, respectively), while there was only a trend for higher uptake in the low-risk group (Table 2).

Discussion

Several radiopharmaceuticals have been developed for accurate staging of prostate cancer. 11C-Acetate, marking lipid metabolism, cannot reliably distinguish benign prostatic hyperplasia from prostate tumors [20]. Moreover, the radiolabeled amino-acid 18F-FABC (18F-Flucicovine) did not show good diagnostic performances for characterization of primary lesions [21]. Finally, 11C/18F-Choline, also marking lipid metabolism, showed lower sensitivity than mpMRI for primary detection of prostate cancer [22]. Thus, improvements in current molecular imaging of prostate cancer appear necessary for accurate characterization of primary prostate tumors.

PSMA and GRP-R are differently overexpressed in prostate cancer, which raises hopes for molecular imaging of tumor lesions in the prostate gland. Few studies have investigated PSMA and GRP-R-based PET/CT imaging at initial staging, before radical prostatectomy. In a recent prospective study performed by Liu et al. on 50 newly diagnosed patients with prostate cancer candidates for radical prostatectomy, 68Ga-PSMA-617 PET/CT was able to detect 95% of primary tumors. The detection rate was similar to that of 68Ga-PSMA-11 PET/CT [23]. Another excellent work was performed by Touijer et al., in which authors prospectively investigate 68Ga-RM2 PET/CT in 16 patients before radical prostatectomy. The performances of 68Ga-RM2 PET/CT imaging did not significantly differ compared to mpMRI in terms of sensitivity, specificity, and accuracy. Moreover, 68Ga-RM2 binding did not correlate with Gleason score [24]. To date, no intra-patient comparison of PSMA and GRP-R targeting at initial staging was reported. Therefore, the objective of this work was to investigate and compare in vitro the potential role of 111In-PSMA-617 and 111In-RM2 at the initial staging of prostate cancer.

Qualitative comparison of 111In-PSMA-617 and 111In-RM2 on our primary prostate cancer samples showed good detectability of both radiopharmaceuticals which is an essential quality for contrasted images in vivo. Then, we quantitatively compared 111In-PSMA-617 and 111In-RM2. When considering all metastatic risk groups together, 111In-PSMA-617 binding was significantly higher than 111In-RM2 (p < 0.001). 111In-PSMA-617 binding was high and no differences were seen according to Gleason score or pre-operative PSA values (Table 2). This high 111In-PSMA-617 binding, whatever the characteristics of the sample, clearly reflects the ability of PSMA imaging to detect most prostate cancers [23] whatever their grade or risk [25]. Moreover, this high signal level may also be explained by a lower binding of 111In-PSMA-617 to normal tissues (p = 0.0161), resulting in a higher TNR for 111In-PSMA-617.

An interesting result of our work is that 111In-RM2 was able to discriminate low metastatic risk samples (p = 0.0046) and therefore low Gleason score samples (p = 0.0061) and samples with low PSA value (p = 0.0012). These results agree with the known high GRP-R expression in low-grade prostate cancer [11]. However, data from GRP-R immunohistochemistry and our results did not necessarily translate into parallel findings at patient imaging in pilot studies. For instance, the only two GRP-R imaging study, performed at the initial staging of prostate cancer, did not show any correlation (positive or negative) between SUVmax on PET/CT and Gleason scores [10, 24]. However, only 1/16 prostate cancers in the study by Touijer et al. and 2/17 in the study by Zhang et al were Gleason 6 [10, 24]. Larger clinical studies are needed to elucidate the potential offered by GRP-R targeting at the initial staging of prostate cancer. Comparison with PSMA would also be helpful.

In intermediate and high-risk samples, 111In-PSMA-617 binding was substantially higher than 111In-RM2 binding, in agreement with the known expression of GRP-R which decreases in higher Gleason scores [11]. 111In-PSMA-617 binding was also higher than 111In-RM2 binding in patients for whom pre-surgical PSA value was > 10 ng/mL. These results agree with the known efficacy of PSMA imaging of intra-prostatic tumors in newly diagnosed high-risk prostate cancer patients [6].

Our results may have future clinical value. Prostate cancer patients with low metastatic risk are today not eligible for radical treatments anymore but rather to active surveillance or focal treatments [26]. Moreover, upgrading in Gleason score between biopsies and radical prostatectomy occurs in about 30% of patients [27]. Hence, an imaging procedure capable to discriminate “true” low metastatic risks would be required to schedule focal treatments in this group of patients and not under-treat patients that would in fact be at higher risk. Results of this work indicate that GRP-R targeting is the only imaging procedure amenable to discriminate low metastatic risk from higher risks. We suggest that GRP-R-based imaging may be first proposed in low metastatic risk patients for biopsy guidance and follow-up of active surveillance. Absence or low uptake at GRP-R imaging would suggest a disease of higher risk (or no disease).

In newly diagnosed prostate cancer patients with intermediate and/or high metastatic risk, PSMA-based imaging is obviously the imaging procedure of choice to characterize intra-prostatic tumors. PSMA-based guided biopsies, staging or radiation treatment planning is being explored in prospective studies [28–30].

We have translated GRP-R and PSMA-based imaging in our center. Patient candidates for radical prostatectomy benefit from sequential 68Ga-PSMA-617 PET/CT and 68Ga-RM2 PET/CT. Preliminary results would support our in vitro data presented in this article.

Limitation of our study is obviously the limited number of samples studied. Moreover, the clinical outcome of patient for whom samples have been used in this study is not known, and we could not assess the prognostic value of GRP-R- and/or PSMA-based imaging and therefore their role in the follow-up of patients.

Conclusion

In this work, we have compared GRP-R and PSMA expression in vitro on primary prostate cancer samples by means of 111In-RM2 and 111In-PSMA-617. Our results show that GRP-R and PSMA-based imaging may have a complimentary role to fully characterize prostate cancer disease, GRP-R being targeted in low metastatic risk patients while PSMA could be a valuable target in higher risks. Future prospective studies are warranted to confirm these data.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Life Molecular Imaging for the provision of RM2 precursor and reference compound.

Funding

This study was funded by “La ligue contre le cancer de Gironde” and was achieved within the context of the Laboratory of Excellence TRAIL ANR-10-LABX-57.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- CNIL

Comité National Informatique et Libertés

- CT

Computed tomography

- GRP-R

Gastrin-releasing peptide receptor

- GS

Gleason score

- HES

Hematoxylin-Eosin-Saffron

- HRMI

High-resolution microimaging

- mpMRI

Multiparametric magnetic resonance imaging

- PCa

Prostate cancer

- PET/CT

Positron emission tomography/computed tomography

- PSA

Prostate-specific antigen

- PSMA

Prostate-specific membrane antigen

- SD

Standard deviation

- SUVmax

Maximum standard uptake value

Authors’ contributions

RS performed experiments, analyzed the data, and wrote the manuscript. HDCG supervised the study and reviewed and approved the final manuscript. MY analyzed the biological samples and approved the final manuscript. MLQR collected the samples and obtained consents from the patients. NB and DV performed experiments and approved the final manuscript. EH supervised the study and reviewed and approved the final manuscript. PF was a recipient of the funding and approved the final manuscript. CM supervised the study, participated in experiments and funding acquisition, analyzed the data, and reviewed and approved the final manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All procedures performed in this study involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study for participation.

Consent for publication

Not applicable

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Romain Schollhammer, Phone: +33768552291, Email: romain.scho@gmail.com.

Henri De Clermont Gallerande, Email: henri.de-clermont-galleran@chu-bordeaux.fr.

Mokrane Yacoub, Email: mokrane.yacoub@chu-bordeaux.fr.

Marie-Laure Quintyn Ranty, Email: quintyn.ml@chu-toulouse.fr.

Nicole Barthe, Email: nicole.barthe@u-bordeaux.fr.

Delphine Vimont, Email: delphinevimont@wanadoo.fr.

Elif Hindié, Email: elif.hindie@chu-bordeaux.fr.

Philippe Fernandez, Email: philippe.fernandez@chu-bordeaux.fr.

Clément Morgat, Email: clement.morgat@chu-bordeaux.fr.

References

- 1.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2017. CA Cancer J Clin. 2017;67:7–30. doi: 10.3322/caac.21387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Afshar-Oromieh A, Zechmann CM, Malcher A, et al. Comparison of PET imaging with a 68Ga-labelled PSMA ligand and 18F-choline-based PET/CT for the diagnosis of recurrent prostate cancer. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2014;41:11–20. doi: 10.1007/s00259-013-2525-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Eder M, Schäfer M, Bauder-Wüst U, et al. 68Ga-complex lipophilicity and the targeting property of a urea-based PSMA inhibitor for PET imaging. Bioconjug Chem. 2012;23:688–697. doi: 10.1021/bc200279b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Morgat C, Mishra AK, Varshney R, et al. Targeting neuropeptide receptors for cancer imaging and therapy: perspectives with bombesin, neurotensin, and neuropeptide-Y receptors. J Nucl Med. 2014;55:1650–1657. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.114.142000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schwarzenboeck SM, Rauscher I, Bluemel C, et al. PSMA ligands for PET imaging of prostate cancer. J Nucl Med. 2017;58:1545–1552. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.117.191031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Uprimny C, Kroiss AS, Decristoforo C, et al. 68Ga-PSMA-11 PET/CT in primary staging of prostate cancer: PSA and Gleason score predict the intensity of tracer accumulation in the primary tumour. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2017;44:941–949. doi: 10.1007/s00259-017-3631-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mansi R, Fleischmann A, Mäcke HR, Reubi JC. Targeting GRPR in urological cancers--from basic research to clinical application. Nat Rev Urol. 2013;10:235–244. doi: 10.1038/nrurol.2013.42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kahkonen E, Jambor I, Kemppainen J, et al. In vivo imaging of prostate cancer using [68Ga]-labeled bombesin analog BAY86-7548. Clin Cancer Res. 2013;19:5434–5443. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-3490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nock BA, Kaloudi A, Lymperis E, et al. Theranostic perspectives in prostate cancer with the gastrin-releasing peptide receptor antagonist NeoBOMB1: preclinical and first clinical results. J Nucl Med. 2017;58:75–80. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.116.178889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhang J, Niu G, Fan X, et al. PET using a GRPR antagonist 68 Ga-RM26 in healthy volunteers and prostate cancer patients. J Nucl Med. 2018;59:922–928. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.117.198929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Beer M, Montani M, Gerhardt J, et al. Profiling gastrin-releasing peptide receptor in prostate tissues: clinical implications and molecular correlates. Prostate. 2012;72:318–325. doi: 10.1002/pros.21434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Körner M, Waser B, Rehmann R, Reubi JC. Early over-expression of GRP receptors in prostatic carcinogenesis. Prostate. 2014;74:217–224. doi: 10.1002/pros.22743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.D’Amico AV, Whittington R, Malkowicz SB, et al. Biochemical outcome after radical prostatectomy, external beam radiation therapy, or interstitial radiation therapy for clinically localized prostate cancer. JAMA. 1998;280:969–974. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.11.969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Reubi JC, Kvols LK, Waser B, et al. Detection of somatostatin receptors in surgical and percutaneous needle biopsy samples of carcinoids and islet cell carcinomas. Cancer Res. 1990;50:5969–5977. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mansi R, Abiraj K, Wang X, et al. Evaluation of three different families of bombesin receptor radioantagonists for targeted imaging and therapy of gastrin releasing peptide receptor (GRP-R) positive tumors. J Med Chem. 2015;58:682–691. doi: 10.1021/jm5012066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gourni E, Canovas C, Goncalves V, et al. (R)-NODAGA-PSMA: a versatile precursor for radiometal labeling and nuclear imaging of PSMA-positive tumors. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0145755. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0145755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Borkowski S, DOEHR O, HULTSCH C, et al. Preclinical validation of the Ga-68- bombesin antagonist BAY 86-7548 for a phase I study in prostate cancer patients. J Nucl Med. 2012;53(supplement 1):177. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Benešová M, Schäfer M, Bauder-Wüst U, et al. Preclinical evaluation of a tailor-made DOTA-conjugated PSMA inhibitor with optimized linker moiety for imaging and endoradiotherapy of prostate cancer. J Nucl Med. 2015;56:914–920. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.114.147413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Morgat C, Schollhammer R, Macgrogan G, et al. Comparison of the binding of the gastrin-releasing peptide receptor (GRP-R) antagonist 68Ga-RM2 and 18F-FDG in breast cancer samples. PLoS One. 2019;14:e0210905. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0210905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Spick C, Herrmann K, Czernin J. Evaluation of prostate cancer with 11C-acetate PET/CT. J Nucl Med. 2016;57:30S–37S. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.115.169599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Parent EE, Schuster DM. Update on 18F-Fluciclovine PET for prostate cancer imaging. J Nucl Med. 2018;59:733–739. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.117.204032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nitsch S, Hakenberg OW, Heuschkel M, et al. Evaluation of prostate cancer with 11C- and 18F-choline PET/CT: diagnosis and initial staging. J Nucl Med. 2016;57:38S–42S. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.115.169748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liu C, Liu T, Zhang N, et al. 68Ga-PSMA-617 PET/CT: a promising new technique for predicting risk stratification and metastatic risk of prostate cancer patients. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2018;45:1852–1861. doi: 10.1007/s00259-018-4037-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Touijer KA, Michaud L, Alvarez HAV, et al. Prospective study of the radiolabeled GRPR antagonist BAY86-7548 for positron emission tomography/computed tomography imaging of newly diagnosed prostate cancer. Eur Urol Oncol. 2018;2(2):166–173. doi: 10.1016/j.euo.2018.08.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Woythal N, Arsenic R, Kempkensteffen C, et al. Immunohistochemical validation of PSMA expression measured by 68Ga-PSMA PET/CT in primary prostate cancer. J Nucl Med. 2018;59:238–243. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.117.195172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Moschini M, Carroll PR, Eggener SE, et al. Low-risk prostate cancer: identification, management, and outcomes. Eur Urol. 2017;72:238–249. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2017.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Porcaro AB, Siracusano S, de Luyk N, et al. Low-risk prostate cancer and tumor upgrading in the surgical specimen: analysis of clinical factors predicting tumor upgrading in a contemporary series of patients who were evaluated according to the modified Gleason score grading system. Curr Urol. 2017;10:118–125. doi: 10.1159/000447164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Storz E, Shah A, Zettinig O, et al. PSMA-PET/MRI-guided transrectal fusion biopsy for the detection of prostate cancer. Eur Urol Suppl. 2015;14:e217. doi: 10.1016/S1569-9056(15)60217-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zettinig O, Shah A, Hennersperger C, et al. Multimodal image-guided prostate fusion biopsy based on automatic deformable registration. Int J Comput Assist Radiol Surg. 2015;10:1997–2007. doi: 10.1007/s11548-015-1233-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Calais J, Kishan AU, Cao M, et al. Potential impact of 68 Ga-PSMA-11 PET/CT on prostate cancer definitive radiation therapy planning. J Nucl Med. 2018;59:1714–1721. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.118.209387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.