Highlights

-

•

Obstacles during rehabilitation need to be faced in order to promote adherence.

-

•

Financial crisis has an impact in adherence to recommended home exercises.

-

•

Communication, individual's needs, capacities, and resources are essential for adherence.

Keywords: Spinal paraplegia, Home rehabilitation, Compliance, Physical therapists

Abstract

Background

The overall purpose of physical therapy for patients with spinal cord injury is to improve health-related quality of life. However, poor adherence is a problem in physical therapy and may have negative impact on outcomes.

Objectives

To explore the physical therapists’ perspectives about patients with incomplete post-traumatic paraplegia adherence to recommended home exercises.

Methods

A qualitative content analysis was conducted. Data were collected in a convenience sample using semi-structured interviews. Thirteen registered physical therapists in Athens area participated in the study.

Results

Five categories emerged from the data: (1) reasons to recommend home exercise by the physical therapist; (2) obstacles to recommend home exercise by the physical therapist; (3) methods addressing these obstacles; (4) the family's role in the adherence to recommended home exercise; and (5) the impact of financial crisis in adherence to recommended home exercise. All participants found the recommended home exercises essential to rehabilitation and health maintenance, and they value their benefits. They also expressed the obstacles that need to be faced during rehabilitation process in order to promote adherence.

Conclusion

Physical therapists should take into account the different obstacles that may prevent patients with incomplete post-traumatic paraplegia adherence to recommended home exercises. These involve the patients and their families, while, financial crisis has also an impact in adherence. In order to overcome these obstacles and increase adherence, communication with patient and family while taking into account the individual's needs, capacities, and resources are essential.

Introduction

Thoracic Spinal Cord Injury (SCI) commonly causes sensory and/or motor loss in the trunk and legs, a condition called paraplegia. The extent and severity of sensory, motor, and autonomic loss from SCI depends on the level of injury to the spinal cord and whether the lesion is “complete” or “incomplete”.1 The global incidence of Traumatic Spinal Cord Injury (TSCI) varies from 8.0 to 246.0 cases/million inhabitants per year and the global prevalence varies from 236.0 to 1298.0 per million inhabitants.2 In Greece, there are several studies on this topic but no official statistics.3, 4, 5, 6, 7 SCI per million in Europe ranges from 8.3 in Denmark to 33.6 in Greece – the highest rate.8

Paraplegia leads to impairment or loss of motor and/or sensory function in the thoracic, lumbar, or sacral (but not cervical) segments of the spinal cord, secondary to damage of neural elements within the spinal canal. With paraplegia arm functioning is spared, but, depending on the level of injury, the trunk, legs, and pelvic organs may be involved.9 Appropriate medical care and rehabilitation can prevent complications and assist the person towards a fulfilling and productive life.10 The SCI rehabilitation process includes multiple phases which take place over a period of weeks, months, or years.11 Progressively challenging community-based ambulation training may result in long-lasting benefits in incomplete SCI.12 Exercise demonstrates ability to enhance activity, life satisfaction, and health of those with SCI.13 The purpose of physical therapy is to improve health-related quality of life by improving patients’ ability to participate in daily life activities.14

Adherence is defined as the extent to which a person's behaviour corresponds with agreed recommendations from a health care provider.15 Poor adherence may negatively affect outcomes and increase healthcare costs. Therefore, physical therapists should take into account attitudes, beliefs, and barriers faced by patients, and design realistic customised treatment plans.16 Poor adherence to physical therapy is a problem, with up to 65% of patients being either non-adherent or partially adherent to their home programmes, and approximately 10% of patients failing to complete their prescribed course of physical therapy.17 A custom-based exercise programme which can balance goals and identify potential limitations for adherence may ensure engagement after SCI. Additionally, goal sharing and planning with the patient are essential elements in designing a custom based exercise programme which ensures long-term exercise commitment.18 A recent qualitative study found that patient education is the most important strategy for ensuring adherence19 and another concluded that trust in the physical therapist's competence, as well as a desire to participate in clinical decision making, fosters active engagement in physical therapy.20

Rehabilitation is proven to benefit those with paraplegia. Adherence, which according to the literature is poor, especially at home, is very important for an effective rehabilitation programme. Hence, it is very important to identify how physical therapists perceive adherence when they recommend home-exercises to patients. This study aimed to explore Greek physical therapists’ perceptions regarding adherence of patients with incomplete post-traumatic paraplegia to recommended home-exercises.

Methods

Design

The current study used a qualitative design with a methodological approach of qualitative content analysis. Qualitative content analysis is used to analyse text data which have been obtained from different resources including interviews.21 Interviews were chosen in order to identify all possible ways in which respondents view/experience phenomena.22

The data analysis was performed by two researchers to prevent the researcher's own hypotheses or previous experiences from influencing the research process,23 and to minimise the subjectivity of the analysis.22 The two researchers have experience in qualitative research methodology; one of them (IS) is a physical therapist with experience in paraplegia and the second (ES) is a health visitor with extensive experience in home care.

Participants

In qualitative research the sample population can vary from one individual to small groups.24 Convenience sampling is a useful method for exploratory studies.21 A convenience sample of 13 physical therapists in Athens participated in the study. The inclusion criteria were: (i) registered physical therapist, (ii) providing home-services to people with incomplete post-traumatic paraplegia, (iii) recommending home-exercises, (iv) having at least 5 years of working experience and additional specialisation in neurological rehabilitation was not required, and (v) understand and speak Greek.

One of the researchers first contacted the Association of Physical Therapists at Attica Prefecture (greater Athens area) and received a list of registered physical therapists who provide home services. Registry based non stratified computer generated randomisation and the researcher contacted by telephone 50 registered physical therapists from the list who were working as private physical therapists, in order to provide them with information about the study, confirm that they meet the inclusion criteria, and inquire whether they wished to participate. After the telephone contact, 20 registered physical therapists fulfilled the inclusion criteria and agreed to participate in the study. Seven were not interviewed due to time constraints, resulting in 13 physical therapists participating in the study.

Data collection

Individual semi-structured interviews were conducted by one of the researchers (IS) who is also a physical therapist. She had no previous personal or professional relationship with the study participants.

The interviewer used an interview guide which included open-ended questions (Table 1). Probes were also used in order to facilitate the interview process, such as repeating a question, asking to give an example, repeating the participants’ answer in researcher's own words, etc. The researcher introduced herself and asked the participants to answer background information questions and then moved to the main research questions.

Table 1.

Interview questions.

| What is your opinion about recommended home-exercise for patients with incomplete post-traumatic paraplegia? |

| What is your experience with recommended home-exercise for patients with incomplete post-traumatic paraplegia? |

| During the years you have been providing home services to patients with incomplete post-traumatic paraplegia, have you noticed any important changes (either improvements or problems)? |

The interviews took place at the participants’ workplaces – primary health care rehabilitation centres. Each interview lasted 30′–45′ and was digitally recorded. Anonymity was ensured since no names were used during the interviews and the interviewer did not make any notes during or after the interviews. The transcripts were not returned to the participants for comments or corrections.

Data analysis

The interviews were transcribed verbatim in Greek. Data was analysed by an inductive qualitative approach using content analysis25 intending to aid an understanding of meaning in complex data through the development of summary themes or categories.26 Content analysis provides a systematic and objective means to make valid inferences from verbal, visual, or written data in order to describe specific phenomena.27

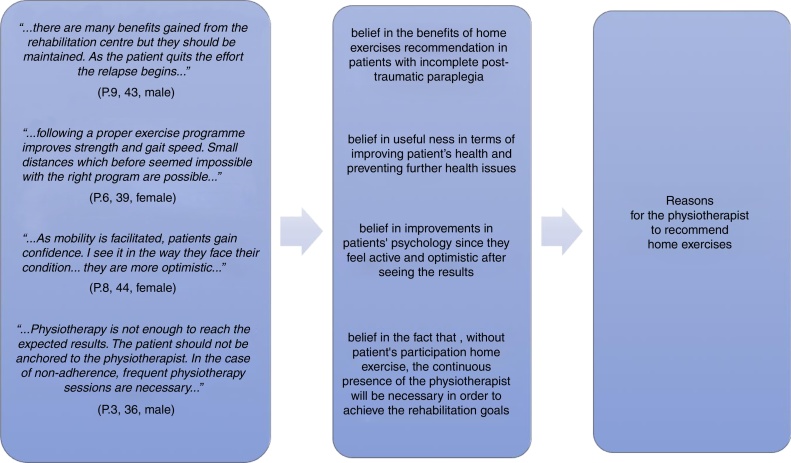

The data analysis was performed by two researchers (IS and ES) and no software was used for the analysis. First, the two researchers read the data several times in order to familiarise themselves with the data and gain an understanding of the text. Second, the two researchers independently produced a data coding and further identified categories and subcategories. Categories emerged by combining similar content areas. A final list of categories was created by mutual consensus between the two researchers. Participants did not provide feedback on the categories. An example of how categories were created is presented in Fig. 1.

Figure 1.

Example of how categories were emerged.

Ethical issues

Ethical approval was granted by the ethics committee of the Medical School, University of Thessaly, Greece (34/2014). All potential participants were informed about the study. Confidentiality and anonymity were reassured. Every participant signed an informed consent form.

Quality reporting criteria

The Consolidated criteria for Reporting Qualitative research28 and the Standards for Reporting Qualitative Research29 were used to report the current study.

Furthermore, the study's trustworthiness was reassured by taking into account Lincoln and Guba's (1985)30 evaluative criteria. Credibility was enhanced by including a second researcher in the data analysis and by using a multidisciplinary group (physical therapist, health visitor, nurse). Furthermore, the participants’ anonymity and the fact that their participation was voluntary add to the trustworthiness of their answers. In order to provide accurate complete answers without needing to rely on the interviewer's memory or notes, the interviews were recorded by a digital device. Previous studies were reviewed in order to relate the current study to the existing body of literature.

Detailed information regarding the overall study process and the methods used are provided to allow researchers to evaluate whether the context is similar to other studies, to assist others in implementing a similar study, and to determine any potential transferability.

The process of data collection and analysis is presented in order to increase the dependability of the study, and to allow others to review the decision making process. Dependability is further enhanced by including in the results original quotations from the participants’ answers and by providing an example on how the categories were formulated (Fig. 1).

Confirmability was established through the objectivity and neutrality with which the data were handled. Furthermore, the entire research team reviewed the process and data analysis. In addition, all the different phases of the analysis have been reported allowing readers to evaluate it.

Results

The 13 participants’ mean age was 46.8 years with mean working experience 13 (range 5–22) years. Their characteristics are presented in Table 2. The physical therapists’ perceptions about patients with incomplete post-traumatic paraplegia adherence to recommended home-exercises are presented in Table 3 using quotations from their answers.

Table 2.

Participants demographic data.

| Participants | Gender | Age | Years of working experience |

|---|---|---|---|

| Participant 1 | Male | 32 | 7 |

| Participant 2 | Female | 47 | 22 |

| Participant 3 | Male | 36 | 12 |

| Participant 4 | Female | 32 | 9 |

| Participant 5 | Male | 40 | 13 |

| Participant 6 | Female | 39 | 13 |

| Participant 7 | Male | 46 | 20 |

| Participant 8 | Female | 44 | 16 |

| Participant 9 | Male | 43 | 15 |

| Participant 10 | Female | 39 | 14 |

| Participant 11 | Male | 30 | 5 |

| Participant 12 | Male | 40 | 16 |

| Participant 13 | Female | 31 | 8 |

Table 3.

Participants’ perceptions about patients with incomplete post-traumatic paraplegia adherence to recommended home exercises.

| 1 | Reasons for the physiotherapist to recommend home-exercises |

“…there are many benefits gained from the rehabilitation centre but they should be maintained. As the patient quits the effort the relapse begins…” (P.9, 43, male) “…following a proper exercise programme improves strength and gait speed. Small distances which before seemed impossible with the right programme are possible…” (P.6, 39, female) “…As mobility is facilitated, patients gain confidence. I see it in the way they face their condition...they are more optimistic...” (P.8, 44, female) “…Physiotherapy is not enough to reach the expected results. The patient should not be anchored to the physiotherapist. In the case of non-adherence, frequent physiotherapy sessions are necessary…” (P.3, 36, male) |

| 2 | Obstacles to recommend home-exercise by the physiotherapist |

“…Patients who resist performing home-exercise are usually mentally tired and shocked by the change in their body, their mobility and generally in their everyday life…” (P.6, 39, female) “…I can understand them... they have been hospitalised, they had a long stay at a rehabilitation centre and then they return home in a new situation, others return in a wheelchair, others with aids. It takes time to adapt. They are very tired and the results are not what they expected…” (P.9, 43, male) “…Some patients are hesitant with benefits of exercise. They believe that everything needed to be done it was done in the rehabilitation centre. They have abandoned the effort and they question the exercises usefulness, as an excuse…” (P. 8, 44, female) “…Patients have stress for the new. Home-exercise is something new for them. At the rehabilitation centre they have been with a colleague (physiotherapist) in a safe environment while at home they have to do some activities by themselves…” (P. 11, 30, male) “…while I notice in many patients who are overconfident...for example, they decide not to use aids. Failure to use the body brace and walking with lumbar spine prolonged hyperextension lead to fatigue, pain and risk of further damage…” (P. 1, 32, male) |

| 3 | Methods addressing the obstacles |

“…My communication with the patients is open. Any time the patients can call me and tell me their problems. They do not need to wait for the day of our session to tell me what bothers them...the programme is exclusively designed for each patient and the slightest difficulty they might face, they can contact me to make immediately the necessary modifications…”(P.4, 32, female) “…with any easy and small, at the beginning, exercise schedule, the patient becomes familiar with the exercise process and overcomes his/her fear and stress…” (P.1, 32, male) “…the programme is determined with the patient. We set together specific and realistic goals. The programme is flexible and can be customised. I am patient's partner and we work together in order to set the goals…” (P.4, 32, female) “…Depression is very common. Any mental health issue is a burden for the patient himself/herself as well as his/her social environment, and it is a factor suspending the adherence to the exercises at home. I suggest to see a mental health specialist…” (P.5, 40, male) |

| 4 | The family's role in the adherence to recommended home-exercise |

“…family has an important role. Frequently I meet tired and frustrated patients and tired families. The goal is that the patient does not give up his/her effort, but also family does not give up support too. The return at home includes several new challenges for the whole family…” (P. 11, 30, male) “…For me, family is an ally. Family members have everyday contact with the patient and they see the difficulties that the patient faces. Family can see the changes in mental status, as well as in patient's physical status. That is the reason that I make sure I have good communication with the family members…” (P. 9, 43, male) “…excessive care provision by the family leads to adverse outcomes. Family does not realise that this prevents patient to be independent and continue his/her effort…” (P. 12, 40, male) |

| 5 | The impact of financial crisis in adherence to recommended home-exercise |

“…increased family needs, long periods of hospitalisation in hospital and at the rehabilitation centre, in addition to the decreased family income and the need of hiring a home carer, all have an impact on physiotherapy…” (P. 9, 43, male) “…it is sad, many patients are forced to stop physiotherapy due to financial reasons even if you see there are possibilities for improvement…” (P. 6, 39, female) “…patient feels that he/she is a burden to his/her family especially when he/she can’t work. I meet often people who are depressed because of this and of course there is no adherence to the home-exercises programme…” (P. 3, 36, male) “…because patients want to have as less as possible physiotherapy sessions, they ask me to design home-exercises programme. They want the best outcome with the least cost for them…” (P. 12, 40, male) |

Reasons for physical therapists to recommend home-exercises

All participants believe in the benefits of home-exercise in patients with incomplete post-traumatic paraplegia. They consider home-exercises necessary for rehabilitation and health maintenance as well as, useful in terms of improving patient's health and preventing further health issues. Adherence to the exercise programme shows improvement in endurance, muscle strength, improved balance and gait, safe mobility, injury prevention, and other conditions such as osteoporosis, arthritis, and cardio-respiratory conditions.

Participants also mentioned that patients with incomplete post-traumatic paraplegia face psychological distress when returning home. Patients’ active participation in the rehabilitation and maintenance programme improves their psychological status since they feel active and optimistic after seeing the results. Physical therapists believe that, without patients’ participation and home-exercise, the continuous presence of the physical therapist will be necessary in order to achieve the rehabilitation goals.

Obstacles for recommending home-exercises

All participants have faced problems with recommending exercises, and patients’ adherence to exercises, partly due to the patients’ physical and mental status. There is fatigue and resignation from the rehabilitation and maintenance process. Patients show mental fatigue, lack of mental strength, and they are in shock due to the change of their mobility and their life in general.

Patients with incomplete post-traumatic paraplegia often feel frustrated and hopeless when their rate of progress begins to slow. Additionally, many expect full recovery during their stay in the rehabilitation centre, and feelings of frustration can intensify when this does not happen.

Physical therapists face the patients’ refusal to cooperate and perform home-exercise, since they consider that their rehabilitation finished when they were discharged from the rehabilitation centre. They are indifferent to their condition and remain passive receivers, not cooperating with the physical therapist, refusing to confront the issue. Physical therapists also mentioned the patients’ fear and insecurity in performing home-exercise themselves, which leads to stress, reduced self-confidence, and lack of self-trust.

Other patients overestimate their abilities, having the impression that by doing more than what the physical therapist recommends they will have better results sooner. Not achieving the result they envisioned can cause frustration, mental, and physical fatigue, which leads them to cease their effort. In addition, this is likely to increase the risk of injury.

Methods addressing the obstacles

All participants agree that good communication with the patient helps in overcoming obstacles. Communication is a two-way process between the physical therapist and the patient, and it is necessary in order to understand each other's problems and expectations.

Designing an individual programme which progresses gradually helps to overcome potential barriers. Furthermore, the physical therapist and the patient together determine the programme, setting realistic goals. The exercises are performed under the physical therapist's supervision while explaining the benefits.

Addressing the patients’ mental health issues is also essential and should be done before the individual has given up or succumb to psychological issues, which require the assistance of mental health professionals.

The family's role in the adherence to recommended home-exercise

Family plays a special role in the adherence to recommended home-exercise; it can play a dynamic role, but it may also be a restraining factor. The family observes the patient's status and may report changes in patient's physical and mental health. Thus, the family can be a partner in the rehabilitation and maintenance process. Nevertheless, a family's excessive love and overprotection can be a factor preventing adherence. In addition, they may cause stress to the patient, leading to adverse outcomes.

The financial crisis’ impact in adherence to recommended home-exercise

In Greece, the financial crisis has had an impact on the health sector. A major part of the cost of physical therapy is covered by the patients and their families. Hence, the number of weekly sessions and the number of patients who receive physical therapy at home have decreased. However, more patients ask for home-exercise programmes for financial reasons. In addition, the financial crisis has had an impact on the patients’ psychology, which is often already burdened.

Discussion

The participants provided rich descriptions regarding adherence to recommended home-exercises by patients with incomplete post-traumatic paraplegia, providing an insight into this important issue for rehabilitation and maintenance.

All participants believe in the benefits of home-exercise recommendations for patients with incomplete post-traumatic paraplegia, and its necessity for rehabilitation and health maintenance. This was expected since there are guidelines about rehabilitation and health maintenance for people with SCI,13 and principles of physical therapy rehabilitation.31 Home-exercises are recommended for improving physical health, as well as for promoting psychological health.32, 33, 34, 35, 36

All participants have faced problems when recommending exercises, and with patients’ adherence to these exercises. There are several obstacles that prevent patients from adhering to the recommended exercises. Part of the problem lies in their physical and mental status, since there may be fatigue, frustration, hopelessness, and resignation from the rehabilitation and maintenance process. Physical therapists face the patients’ refusal to cooperate and to perform home-exercises. Patients don’t find exercises useful and necessary since they consider their rehabilitation completed when they are discharged. They are indifferent to their condition and remain passive receivers, not cooperating with the physical therapist, refusing to confront their problems. An earlier study37 found that positive expectations about being able to walk again, and recovery in general, seemed to be common substantive aspects of hope; patients hoped for recovery and every improvement stimulated that hope. In the current study, physical therapists also mentioned the patients’ fear and insecurity in performing home-exercise by themselves. This fear leads to stress, reduced self-confidence, and lack of self-trust. Fear of injury was also previously identified as a barrier.38 Overestimation of abilities can also result in cessation of exercising, frustration, fatigue, and increased risk of injury.

Despite motivation and interest in being physically active, people with SCI face many obstacles, and thus, removal of barriers, coupled with promotion of facilitating factors, is vital for enhancing opportunities for physical activity and reducing the risk of costly secondary conditions in this population.38 If adherence is proven to be less than desirable, an effective solution to the problem can be sought when its underlying reasons have been identified.17 It has been found that meeting obstacles, the physical therapists’ sensitivity and ability to negotiate the task, the emotions related to the task, and the nature of the relationship seem to restore the facilitation of change.39 All study participants agreed that good communication with the patient helps in overcoming the obstacles in regards to adherence. Similarly, in another study, physical therapists identified communication skills as the primary area of learning for difficult patients.40 Designing an individual programme which progresses gradually helps to overcome potential barriers. Furthermore, the physical therapist and the patient together determine the programme, setting realistic goals. The literature supports that goals sharing and planning with patients are important in designing a custom based exercise programme that ensures long-term exercise commitment.18

Rehabilitation should include emotional and social support.41 The participants supported that it is essential to address the patients’ mental health issues since patients may abandon their efforts and, in return, the physical therapists make referrals to mental health professionals. Similarly, the literature suggests that suboptimal functional outcomes associated with poor emotional health have been reported in a variety of orthopaedic specialties.42

According to the World Health Organization,1 family members are encouraged to be active members of the rehabilitation team. This study revealed that family plays a special role in adherence to recommended home-exercise; they can play a dynamic role, but they can also be a restraining factor. The family experiences daily the patient's reality and may report to the health professionals the changes in the patient's physical and mental health. Thus, family can be a partner in the rehabilitation and maintenance process. These findings agree with the literature. It has been found that family support provides patients with practical help and can buffer the stresses of living with illness.43 Moreover, the relationship between social support and health outcomes may be mediated by patient adherence.44

Nonetheless, the family's excessive love and overprotection may prevent from adherence. They may cause stress to the patient which can lead to adverse outcomes. An earlier study has found that family members considered their involvement as very important and they were often given opportunities to be involved. However, there might be disagreements between patients and family members regarding the care quality and delivery, which may disrupt the rehabilitation process and its outcomes. Therefore, it is important that differences in perspectives are identified and successfully resolved.45

Finally, as revealed by the current study, in Greece, the financial crisis has had an impact on patients’ rehabilitation, which goes beyond Greece and is relevant to other countries as well. The literature also supports that globally, people's health status is definitely affected by the economic crisis and consequently the healthcare sector will be charged to meet efficiently the increasing needs.46 According to our study participants, a major part of the physical therapy cost is covered by the patients and their families. Hence, the number of weekly sessions and the number of patients who have physical therapy at home have decreased. However, more patients ask for home-exercise programmes due to financial reasons.

It seems apparent that there has been a failure to address people's health and social needs in Greece.47 Since 2011, a horizontal cut of 50% of the cost ceilings for rehabilitation aid and equipment has been imposed, along with an additional 30–50% cut on medical supplies and specialised health services.48 Austerity measures shifted the financial burden for healthcare costs to households.49 Furthermore, there is an increase in the incidence of mental health disorders due to the financial crisis.50 This is also depicted in the current study, where it was seen that financial crisis has an impact on the patients’ psychological state which in most cases is already burdened due to their decreased functionality. Similar impact of financial crisis is indicated by recent data in Ireland where at least 72,000 people are waiting for physical therapy and other rehabilitation services in the community.51 Addition, in Canada, the current global economic crisis led to tightened federal budgets including alterations to the funding of physical therapy services.52

Limitations

The study limitations include the fact that recruitment was done via telephone which may hide a selective bias. However, recruitment via telephone is used in studies with convenience sample as a common way to recruit potential participants and save time in planning interviews. Another limitation is that the convenience sample does not allow for generalisation of the findings, which is also due to the small number of participants attributed to the qualitative design approach and the cultural differences among different countries. The fact that specialisation in neurological rehabilitation was not required for the participants may have influenced the findings. Nevertheless, the results are in line with and expand those of previous studies.

Conclusions

All participants found essential the recommended home-exercises and they value their benefits for the patients’ physical health as well as their mental health. However, during the rehabilitation process there are several obstacles that may cause low adherence. These obstacles may involve the patients (e.g. refusal to cooperate, abilities overestimation, frustration, fatigue) and their families (e.g. overprotection). The financial crisis is an additional obstacle. Physical therapists need to be prepared to address those obstacles and open communication channels with the patients and their families taking into account the individual's needs, capacities, and resources. Additionally, the current study provides information that can be used in physical therapy education on how to promote adherence and manage non-adherence.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.W.H.O. International Perspectives on Spinal Cord Injury. 2013, http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/94190/1/9789241564663_eng.pdf Accessed 03.11.17.

- 2.Furlan J.C., Sakakibara B.M., Miller W.C., Krassioukov A.V. Global incidence and prevalence of traumatic spinal cord injury. Can J Neurol Sci. 2013;40:456–464. doi: 10.1017/s0317167100014530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sapountzi-Krepia D., Soumilas A., Papadakis N. Post traumatic paraplegics living in Athens: the impact of pressure sores and UTIs on everyday life activities. Spinal Cord. 1998;36:432–437. doi: 10.1038/sj.sc.3100641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Divanoglou A., Levi R. Incidence of traumatic spinal cord injury in Thessaloniki, Greece and Stockholm, Sweden: a prospective population-based study. Spinal Cord. 2009;47:796–801. doi: 10.1038/sc.2009.28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Koutsodontis I., Lavdaniti M., Sapountzi-Krepia D. A study of the spinal cord injured population of the Chios island of Greece. Int J Caring Sci. 2011;4:90. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Latsou D., Pierrakos G., Yfantopoulos N., Yfantopoulos J. Health-related quality of life of people with mobility limitations using wheelchairs in Greece. Arch Hellenic Med. 2014;31:591–598. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Papadakis S.A., Galanakos S., Apostolaki K. Spinal cord injuries following suicide attempts. In: Dionyssiotis Y., editor. Topics in Paraplegia. InTech; Athens: 2014. pp. 53–70. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jazayeri S.B., Beygi S., Shokraneh F., Hagen E.M., Rahimi-Movaghar V. Incidence of traumatic spinal cord injury worldwide: a systematic review. Eur Spine J. 2014;24:905–918. doi: 10.1007/s00586-014-3424-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kirshblum S.C., Burns S.P., Biering-Sorensen F. International standards for neurological classification of spinal cord injury (Revised 2011) J Spinal Cord Med. 2011;34:535–546. doi: 10.1179/204577211X13207446293695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.W.H.O. World report on disability. 2011, http://www.who.int/disabilities/world_report/2011/report.pdf Accessed 03.11.17.

- 11.Suzon H., Zahangir A., Maliha H. Rehabilitation of patients with paraplegia from Spinal Cord Injury: a review. JCMCTA. 2009;20:53–57. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lam T., Wolfe D.L., Domingo A., Eng J.J., Sproule S. 2014. Lower Limb Rehabilitation Following Spinal Cord Injury. https://scireproject.com/evidence/rehabilitation-evidence/lower-limb/ Accessed 03.11.17. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jacobs P.L., Nash M.S. Exercise recommendations for individuals with Spinal Cord Injury. Sports Med. 2004;34:727–751. doi: 10.2165/00007256-200434110-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Harvey L. Elsevier; London: 2008. Management of Spinal Cord Injury. A Guide for Physiotherapists. [Google Scholar]

- 15.W.H.O. Adherence to Long-Term Therapies. Evidence for Action. 2003. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/42682/1/9241545992.pdf Accessed 03.11.17.

- 16.Jack K., McLean S.M., Moffett J.K., Gardinerc E. Barriers to treatment adherence in physiotherapy outpatient clinics: a systematic review. Man Ther. 2010;15:220–228. doi: 10.1016/j.math.2009.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bassett S.F. The assessment of patient adherence to physiotherapy rehabilitation. N Z J Physiother. 2003;31:60–66. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gorgey A.S. Exercise awareness and barriers after spinal cord injury. World J Orthop. 2014;5:158–162. doi: 10.5312/wjo.v5.i3.158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stickler K.R. Adherence to physical therapy: a qualitative study. J Stud Phys Ther Res. 2015;8:32–40. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bernhardsson S., Larsson M.E.H., Johansson K., Öberg B. “In the physio we trust”: a qualitative study on patients’ preferences for physiotherapy. Physiother Theory Pract. 2017;33:535–549. doi: 10.1080/09593985.2017.1328720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Burns N., Grove S.K. 6th ed. Saunders Elsevier; St. Louis, USA: 2009. The Practice of Nursing Research. Appraisal, Synthesis and Generation of Evidence. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Parahoo K. Palgrave Macmillan; New York: 2006. Nursing Research. Principles, Process and Issues. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mays N., Pope C. Assessing quality in qualitative research. Br Med J. 2000;320:50–52. doi: 10.1136/bmj.320.7226.50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ingham-Broomfield R.B. A nurses’ guide to qualitative research. Aust J Adv Nurs. 2014;32:34–40. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Miles M., Huberman A. 2nd ed. Sage Publications, CA; Thousands Oaks: 2001. Qualitative Data Analysis. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Thomas D.R. A general inductive approach for analyzing qualitative evaluation data. Am J Eval. 2006;27:237–246. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Downe-Wambolt B. Content analysis: method, applications and issues. Health Care Women Int. 1992;13:313–321. doi: 10.1080/07399339209516006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.O’Brien B.C., Harris I.B., Beckman T.J., Reed D.A., Cook D.A. Standards for reporting qualitative research: a synthesis of recommendations. Acad Med. 2014;89:1245–1251. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000000388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tong A., Sainsbury P., Craig J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care. 2007;19:349–357. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzm042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lincoln Y.S., Guba E.G. Sage Publications; Newbury Park, CA: 1985. Naturalistic Inquiry. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Harvey L.A. Physiotherapy rehabilitation for people with spinal cord injuries. J Physiother. 2016;62:4–11. doi: 10.1016/j.jphys.2015.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Brown A.K., Woller S.A., Moreno G., Grau J.W., Hook M.A. Exercise therapy and recovery after SCI: evidence that shows early intervention improves recovery of function. Spinal Cord. 2011;49:623–628. doi: 10.1038/sc.2010.167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Giangregorio L.M., Webber C.E., Phillips S.M. Can body weight supported treadmill training increase bone mass and reverse muscle atrophy in individuals with chronic incomplete spinal cord injury? Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. 2006;31:283–291. doi: 10.1139/h05-036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hicks A.L., Adams M.M., Martin Ginis K., Giangregorio L., Latimer A., Phillips S.M. Long-term body-weight-supported treadmill training and subsequent follow-up in persons with chronic SCI: effects on functional walking ability and measures of subjective well-being. Spinal Cord. 2005;43:291–298. doi: 10.1038/sj.sc.3101710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hicks A.L., Martin K.A., Ditor D.S. Long-term exercise training in persons with spinal cord injury: effects on strength, arm ergometry performance and psychological well-being. Spinal Cord. 2003;41:34–43. doi: 10.1038/sj.sc.3101389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Martin Ginis K.A., Latimer A.E., McKechnie K. Using exercise to enhance subjective well-being among people with spinal cord injury: the mediating influences of stress and pain. Rehabil Psychol. 2003;48(3):157–164. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lohne V., Severinsson E. Hope during the first month after acute spinal cord injury. J Adv Nurs. 2004;47:279–286. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2004.03099.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kehn M., Kroll T. Staying physically active after spinal cord injury: a qualitative exploration of barriers and facilitators to exercise participation. BMC Public Health. 2009;9:168. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-9-168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Øien A.M., Steihaug S., Iversen S., Råheim M. Communication as negotiation processes in long-term physiotherapy: a qualitative study. Scand J Caring Sci. 2011;25:53–61. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-6712.2010.00790.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Potter M., Gordon S., Hamer P. The physiotherapy experience in private practice: the patients’ perspective. Aust J Physiother. 2003;49:195–202. doi: 10.1016/s0004-9514(14)60239-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rabeh S.A., Caliri M.H.L. Functional ability in individuals with spinal cord injury. Acta Paul Enferm. 2010;23:321–327. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ayers D.C., Franklin P.D., Ring D.C. The role of emotional health in functional outcomes after orthopaedic surgery: extending the biopsychosocial model to orthopaedics. J Bone Jt Surg Am. 2013;95 doi: 10.2106/JBJS.L.00799. e165(1–7) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Miller T.A., DiMatteo M.R. Importance of family/social support and impact on adherence to diabetic therapy. Diabetes Metab Syndr Obes. 2013;6:421–426. doi: 10.2147/DMSO.S36368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.DiMatteo M.R. Social support and patient adherence to medical treatment: a meta-analysis. Health Psychol. 2004;23:207–218. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.23.2.207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lindberg J., Kreuter M., Persson L.-O., Charles Taft C. Family members’ perspectives on patient participation in spinal cord injury rehabilitation. Int J Phys Med Rehabil. 2014;2:223. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Notara V., Koulouridis K., Violatzis A., Vagka E. Economic crisis and health. The role of health care professionals. Health Sci J. 2013;7:149–154. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sakellari E., Pikouli K. Assessing the impact of the financial crisis in mental health in Greece. Ment Health Nurs. 2013;33:19–21. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hauben H, Coucheir M, Spooren J, McAnaney D, Delfosse C. Assessing the impact of European governments’ austerity plans on the rights of people with disabilities. 2012, http://www.enil.eu/wp-content/uploads/2012/12/Austerity-European-Report_FINAL.pdf Accessed 03.11.17.

- 49.Karanikolos M., Mladovsky P., Cylus J. Financial crisis, austerity, and health in Europe. Lancet. 2013;381:1323–1331. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60102-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kentikelenis A., Karanikolos M., Papanicolas I., Basu S., McKee M., Stuckler D. Health effects of financial crisis: omens of a Greek tragedy. Lancet. 2011;378:1457–1458. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61556-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Nolan A, Barry S, Burke S, Thomas S. The impact of the financial crisis on the health system and health in Ireland. 2014, http://www.euro.who.int/_data/assets/pdf_file/0011/266384/The-impact-of-the-financial-crisis-on-the-health-system-and-health-in-Ireland.pdf?ua=1 Accessed 03.11.17.

- 52.Gibson B.A., Nixon S.A., Nicholls D.A. Critical reflections on the physiotherapy profession in Canada. Physiother Can. 2010;62:98–100. doi: 10.3138/physio.62.2.98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]