Short abstract

The coevolution of mammals with their gut microbiota is heavily influenced by diet. Here we investigate the evolution of the gut microbiota in an African mole rat, which has a highly fibrous diet that includes underground storage organs of plants. For this purpose, microbial DNA was isolated from the digesta of a Cape dune mole rat gut, and 23 of 62 partial length 16S rRNA sequences were chosen for full length sequence determination. In addition, V4 regions of 16S rRNA were sequenced using Illumina technology. These sequences were then compared to previously identified sequences in the NCBI and Greengenes databases. Treponeme-related sequences within the mole rat showed evidence of a substantial adaptive radiation, with considerable diversity found within the mole rat (81% minimum sequence identity) as well as substantial divergence (87.3% average sequence identity to nearest neighbor) from previously identified organisms. It also appears likely that Desulfovibrio and several other bacterial clades, but not Clostridia-related organisms, have undergone substantial evolutionary changes during the evolution of mole rats and their ancestors. These findings support the intuitive view that some enteric bacteria can be described as “housekeeping,” with a niche defined by the host gut largely independent of diet. This diet-independent niche space and the microbes occupying it appear to be stable despite substantial alteration of diet-dependent niches and adaptive radiation of microbes occupying those niches.

Impact statement

The composition of the microbiota is of critical importance for health and disease, and is receiving increased scientific and medical scrutiny. Of particular interest is the role of changing diets as a function of agriculture and, perhaps to an even greater extent, modern food processing. To probe the connection between diet and the gut’s microbial community, the microbiota from a mole rat, a rodent with a relatively unusual diet, was analyzed in detail, and the microbes found were compared with previously identified organisms. The results show evidence of an adaptive radiation of some microbial clades, but relative stability in others. This suggests that the microbiota, like the genome, carries with it housekeeping components as well as other components which can evolve rapidly when the environment changes. This study provides a very broad view of the niche space in the gut and how factors such as diet might influence that niche space.

Keywords: Diet, evolution, fiber, microbiota, mole rat, niche

Introduction

Diet is perhaps the most important factor that affects the day-to-day composition of the microbiome, having a strong influence on the microbial community of the gut of humans1 and other species.2–5 At the same time, host phylogenetic relationships can strongly influence the microbial composition present in the gut of a given host.6–8 Microbial communities in the guts of a wide range of mammalian species have been characterized, including those from folivores, frugivores, carnivores, and omnivores.2–4,9 Furthermore, microbial communities have also been characterized in animals regarded as dietary specialists, including those that eat exclusively bamboo10 or eucalyptus.11

One clade of mammals that has a particularly fibrous diet is the African mole rat. These subterranean rodents eat underground storage organs of plants such as corms, bulbs, tubers, and rhizomes.12 These storage organs contain a high concentration of nutrients, but are generally unpalatable to most animals. Some are toxic, containing cardiac glycosides,13 whereas others possess thick and spiny coverings.14 Many also have a very high fiber content.15 Despite these defenses, underground storage organs are a mainstay of the African mole rat’s rather atypical diet. Because of the plant’s defenses, mole rats face very little competition for these nutrient-rich food sources. In addition to consumption of underground storage organs, the Cape dune mole rat (Bathyergus suillus) studied here ingests the aerial portions of grasses.

Given the atypical diet of the mole rat compared to many other rodents, understanding the evolution of the mole rat microbiota could provide insight into the differing roles of diet and host physiology in influencing the gut microbiota. To probe the evolution of the mole rat microbiota, microbial DNA was extracted from the gut of a Cape dune mole rat, and full length 16S rRNA encoding sequences were determined by Sanger sequencing. In addition, V4 regions of 16S rRNA encoding sequences were determined using Illumina technology. From the sequences obtained, the four clades which contained the most bacteria in the community were selected for further study, and cladograms were then constructed using pairwise matching algorithms as well as other approaches. Both full length 16S rRNA sequences and V4 16S rRNA sequences were evaluated in this manner to provide more depth and a wider breadth of sequence information, respectively. The diversity of the mole rat’s microbiota and the relatedness of that microbiota to other species were then assessed to derive clues about the origins of the microbiota. Given that this project involves extensive study of the bacteria from a single animal, it was not intended to probe the community structure of the mole rat’s microbiota. Rather, the relatedness of the mole rat’s bacteria with bacteria present in the databases is expected to provide insight into the course of evolution of the mole rat’s microbiota.

Materials and methods

Procurement of samples for microbiota analysis

All procedures involving animals were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Pretoria (protocol number AUCC 040702/015). One female B. suillus (weight = 841 g) was caught in the wild and euthanized immediately as part of an unrelated study; no diet which might alter the microbiota was offered to the animal in captivity. The entire large intestine was excised, fixed in ethanol, and then stored in ethanol at 4°C until use.

Genomic DNA extraction

Intestinal contents were washed three times in 40 mL of sterile phosphate-buffered saline by vortexing fecal material to resuspend and break up any clumps, allowing heavy particles (sand, root pieces, etc.) to settle out for 10–20 s, removing the supernatant to a new, sterile tube, and finally centrifuging the supernatant at 300g for 10 min. Inspection of the washes and remaining resuspended pellets under a microscope following staining with SYTO BC Green Fluorescent Nucleic Acid Stain (Thermo Fisher Scientific) showed that ∼90% of the bacteria contents remained in the pellets after each wash.

The final, washed bacterial pellet was used to isolate genomic DNA (gDNA) with the DNA Isolation for Cells and Tissue Kit (Roche Applied Science, Indianapolis, IN) according to the manufacturer’s instructions, except that some alternative volumes and incubation conditions were used in the following order: 25 mL cellular lysis buffer, 50 µL proteinase K solution, and 833 µL RNase solution were used. The sample was incubated at 37˚C for 40 min, and finally 10 mL of precipitation solution was used.

The resulting gDNA was then cleaned of humics, polyphenols, and other PCR inhibitors inherent in the high plant content of the fecal contents of the mole rat using the PowerClean Pro DNA Clean-Up Kit (Mo Bio Laboratories, Carlsbad, CA) following manufacturer’s instructions. gDNA was used for Illumina sequencing or cloned as described below.

Amplification and cloning of 16S region

Cleaned gDNA was amplified by PCR using Expand High Fidelity+ PCR System (Roche Applied Science), forward primer 16S UNI F-9 CCGTCGACAGAGTTYGATYCTG GCT and reverse primer 16S UNI R-1513 CCGGATCCTA CGGYTACCTTGTTAC (both 5′ to 3′). PCR cycling conditions were 1 cycle of 94˚C for 2 min, 35 cycles of 94˚C for 30 s, 53˚C for 1.5 min, and 72˚C for 2 min and ending in 1 cycle of 72˚C for 7 min. The PCR product was electrophoresed on a 2% agarose gel and a single band ∼1500 bp was purified (Agarose Gel DNA Extraction Kit System, Roche Applied Science).

Purified PCR product was cloned into E. coli plasmid vector pCR 4-TOPO (TOPO TA Cloning Kit, Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA). Plasmids were extracted (QIAprep Spin Minipreps, Qiagen, Valencia, CA or Genopure Plasmid Maxipreps, Roche Applied Science) and used for Sanger sequencing.

Sanger sequencing and analysis

Purified plasmid DNA was sequenced by the Duke University DNA Analysis Facility using Applied Biosystems Dye Terminator Cycle Sequencing systems and BigDye Terminator v1.1 sequencing chemistry with the 3730 PRISM DNA Analyzer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA). All Sanger sequences have been deposited in the GenBank database under accession numbers KY635412-KY635434.

Sequences obtained from cloned 16S rRNA were grouped by homology pairing and assigned presumptive taxonomic classification as described in the Results. Selected partial sequences were further sequenced to obtain full length sequences (See Results), and Trees (cladograms) were constructed using the full length sequences obtained from the Cape dune mole rat in addition to related sequences identified by BLAST.16

Phylogenetic tree construction

Phylogenetic trees (cladograms) were constructed using the full-length and V4 16S rRNA sequences obtained from the Cape dune mole rat in addition to related sequences identified by BLAST.16 Three programs were used to align 16S rRNA sequences and the comparison contigs. CLC Sequences Viewer (QIAGEN), which uses a progressive alignment algorithm, and SSU-ALIGN,17 a software specifically designed for aligning 16S rRNA were used. Sequences were also aligned using the MUSCLE algorithm18 in MEGA719 as an alternative. Three alignment methods were utilized to determine to what extent results were dependent of the approach to alignment. When using SSU-ALIGN,17 the ssu-mask function was ran to mask out alignment columns that are likely to include a significant number of misaligned nucleotides and to convert the files into FASTA (.afa) format. The alignments were then imported in CLC Sequences Viewer (QIAGEN) to convert the .afa suffixed files into the .fa suffixed files. The resulting MEGA719 compatible .fa alignment files were imported into MEGA7 to construct multiple models of genetic ancestry. The following six pairs of statistical methods and model types were utilized for full length sequences aligned with either CLC Sequences Viewer or with SSU-ALIGN: (a) Maximum Parsimony, Sub-tree pruning. (b) Maximum Likelihood, Jukes Cantor, (c) Maximum Likelihood, General Time Reversible, (d) Neighbor Joining, Maximum Composite Likelihood, (e) Neighbor Joining, Jukes Cantor, and (f) UPGMA, Jukes Cantor. For V4 sequences and for full length sequences aligned with MUSCLE, only the Neighbor Joining, Maximum Composite Likelihood model was used.

Illumina sequencing and analysis

A sample containing 50 ng of extracted DNA was sent to Argonne National Laboratory for downstream amplification and Illumina sequencing, as described in McKenney et al.2 The PCR primers 515F (GTG-CCA-GCM-GCC-GCG-GTA-A) and 806R (GGA-CTA-CHV-GGG-TWT-CTA-AT) were used to amplify the V4 region of 16S rRNA with length ∼300 bp for 150 bp paired-end sequencing on the Illumina MiSeq platform according to the methods of Caporaso et al.20 All Illumina sequences have been deposited in the Sequence Read Archive database under accession number SAMN06349216. Forward and reverse Illumina reads were joined using ea-utils.21 A total of 495,829 16S rRNA sequences were joined from the forward and reverse reads; only the joined reads were used in our analysis. Joined 16S rRNA sequence reads were demultiplexed and analyzed using Quantitative Insights Into Microbial Ecology (QIIME, v1.8.0)22 to classify microbial constituents.23 Quality filtering was performed using default settings and the input sequence file was split into libraries using 12 bp barcodes. A total of 494,748 sequences passed quality filtering thresholds.

These sequences were classified into operational taxonomic units (OTUs, a proxy for taxa based on 97% sequence similarity) using the Uclust method24 and identified using the Greengenes 13_8 database.22 Trees (cladograms) were constructed using sequences from the mole rat and related sequences as described above.

Results

Sequencing of 16S rRNA

The primary goal of the Sanger sequencing effort was to determine full length 16s rRNA sequences from the mole rat gut that covered a broad phylogenetic distance. With this in mind, partial length 16s rRNA sequences were first determined in an initial round of cloning, and sequences were selected for full length sequencing if they represented a relatively unique sequence in their clade. Using this approach, 62 partial length 16S rRNA sequences were obtained using PCR amplification and cloning as described above, and a presumptive taxonomic identification was made based on similarity to known sequences. This initial round of cloning facilitated the assignment of the 62 partial length sequences into 8 clades (7 genus level, 1 family level) as shown in Table 1. Of the 62 partially sequenced clones, 23 were selected for further sequencing to obtain full length 16s rRNA sequences. Using this approach, most clones (90% of the total) presumptively assigned to Treponema and Desolfovibrionaceae were fully sequenced. On the other hand, due to their limited diversity, relatively few clones (17% of the total) of 16s rRNA sequences assigned to Lachnospiraceae and Sarcina were sequenced fully, despite their greater abundance in the microbiome. All 16s rRNA clones from clades that were poorly represented (one or two sequences) were sequenced fully.

Table 1.

Microbiota composition of a Cape dune mole rat.

| Nearest clade, reference sequence identifier, % identity | Sanger, number of sequences (% total) | Sanger, % identity to nearest sequence, nearest sequence identifier, source of sequence | Sanger, minimum sequence identity within clade (%) | Illumina, % total sequences |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LachnospiraceaeJX101687, 93.3% | 28 (44.4) | 97.0%, FJ681814.1cow feces | 98.3 | 18.7 |

| SarcinaAF110272.1, 98.8% | 18 (28.6) | 99.2%, EU778650spectacled bear gut | 99.3 | 40.8 |

| TreponemaNR_074742, 85.6% | 6 (9.5) | 87.3%a, AB746820cow gut | 81.8 | 4.4 |

| DesulfovibrioNR_102487.1, 89.5% | 4 (6.3) | 91.3%, JQ085186.1mouse gut | 98.5 | 18.3 |

| ClostridiumNR_102987, 90.7% | 2 (3.2) | 96.4%, LC028782cow feces | 98.7 | — |

| PrevotellaNR_113093, 91.2% | 2 (3.2) | 94.6%, HQ716139pig feces | 92.1 | 0.52 |

| PeptostreptococcaceaeJN713291, 92.7% | 1 (1.6) | 92.9%, AB62770rat cecum | __ | 0.0029 |

| AnaerocellaNR_132392, 84.3% | 1 (1.6) | 92.4%, AB512033sheep rumen | __ | 0.042 |

Note: Sequences determined by the Sanger method were presumptively classified by genus, except for Peptostreptococcaceae (family). The classification, nearest known (identified) sequence identifier, and the percent identity to the nearest known sequence are shown in column 1. The number and relative abundance of each group of sequences is shown in the second column. The third column shows the percent identity between sequences from the Cape dune mole rat and the nearest sequence present in the database (whether from a known or an unidentified organism). The sequence identifier for the nearest known sequence is also shown in that column. The minimum sequencer identity within all possible combinations of Sanger sequences in a given clade, indicating the breadth of diversity in that clade, is shown in column 4. The number of OTUs and the relative number of sequences accounted for by those OTUs as determined by Illumina sequencing are shown in column 5. The percent of OTUs accounted for by a given genus is shown in the right hand column, along with the percent as a function of the relative number of total sequences within those OTUs. A total of 63 and 494,748 sequences were determined by the Sanger method and by Illumina, respectively.

This excludes one sequence from a naked mole rat, which was 90% identical to one of the sequences determined in this study.

To provide a broader coverage of the microbial community in the mole rat gut, Illumina technology was used to evaluate V4 regions of 16S rRNA as described in the Methods. Of the 494,748 V4 sequences obtained using this approach, 82.8% fit within the eight taxonomic clades for which the cloned sequences presumptively fit (Table 1). There were no V4 sequences that fit into the Clostridium genus (Table 1), but clades of all other cloned sequences were represented within the repertoire of V4 sequences.

Both Sanger sequencing and Illumina sequencing revealed a predominance of Clostridia-related bacteria, which were presumptively assigned to Lachnospiraceae and Sarcina (Table 1). These two clades comprised 73% and 59.5% of partial length Sanger sequences and Illumina V4 sequences, respectively. Sequences assigned to Treponema and Desolfovibrionaceae were both well represented in the Sanger and Illumina sequences, although Desolfovibrionaceae was more common in the Illumina sequences (18.3%) than in the Sanger sequences (6.3%).

Sequences assigned to the Treponeme clade

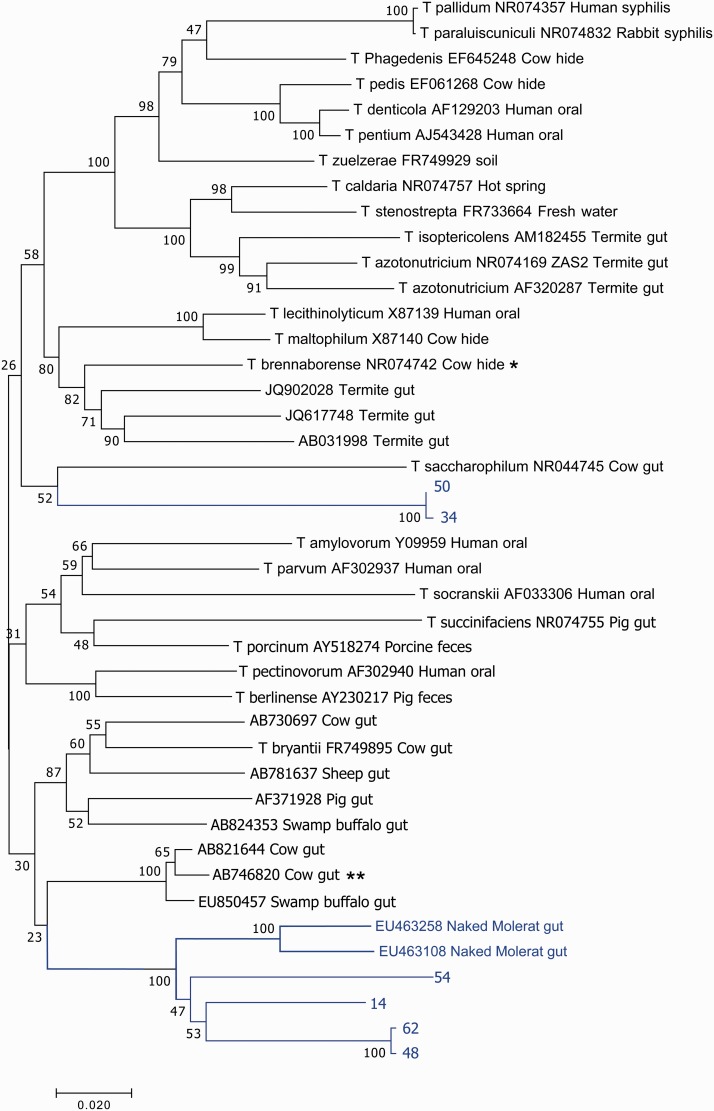

Figure 1 shows a cladogram containing 6 full length Cape dune mole rat-derived 16S rRNA sequences along with 36 other related sequences, 23 of which have been identified as belonging to Treponemes. The remaining 13 were obtained from unknown microbes, including two unknown microbes from the naked mole rat. The closest related sequence by homology was from the bovine gut, and the cladogram indicated closest evolutionary relationship from another sequence obtained from bovine gut (Figure 1). Substantial divergence of the Cape dune mole rat sequences from other sequences is observed, and substantial divergence within the Cape dune mole rat sequences is also observed (Figure 1, Table 1), suggesting substantial evolutionary drift of the microbiota during the course of evolution of mole rats. Taken together, the Cape dune mole rat and naked mole rat full length sequences form two distinct clades when aligned using SSU-ALIGN (Figure 1). These two clades were present regardless of the model used for the tree formation, but the presence of two clades was dependent on the alignment, with mole rat sequences sometimes forming a single clade when aligned with either CLC Sequences Viewer or with MUSCLE, depending on the tree model. The results of alignment using V4 sequences only (Figure 2) identified three distinct groups of mole rat sequences. Two of the groups obtained using V4 sequences (i.e. the group containing full length clones 50 and 34, and the group containing the rest of the full length clones) were the same ones identified in an alignment dependent fashion when full length sequences were considered. However, the third group identified using V4 sequences, consisting of 33 OTUs but no cloned sequences, may represent a distinct group of Treponeme sequences that are substantially diverged from all other known sequences, including the sequences cloned in this study.

Figure 1.

Treponema phylogenetic tree constructed with full length 16S rRNA sequences. Sequences from the mole rat are shown in light color, with nearest neighbors in black. The evolutionary history was inferred using the Neighbor-Joining method.25 The optimal tree with the sum of branch length = 1.92483810 is shown. The percentage of replicate trees in which the associated taxa clustered together in the bootstrap test (1000 replicates) are shown next to the branches.26 The tree is drawn to scale, with branch lengths in the same units as those of the evolutionary distances used to infer the phylogenetic tree. The evolutionary distances were computed using the Maximum Composite Likelihood method27 and are in the units of the number of base substitutions per site. The analysis involved 42 nucleotide sequences. All positions containing gaps and missing data were eliminated. There were a total of 1231 positions in the final dataset. Evolutionary analyses were conducted in MEGA7.19 *Sequence with nearest identity to a sequence from mole rat gut, used for presumptive identification of clade. **Sequence with nearest identity to sequences from mole rat gut (from an unknown bacterial species and therefore not used for identification of clade). (A color version of this figure is available in the online journal.)

Figure 2.

Treponema phylogenetic tree constructed with V4 16S rRNA sequences. Sequences from the mole rat are shown in light color. The evolutionary history was inferred using the Neighbor-Joining method.25 The optimal tree with the sum of branch length = 5.09844727 is shown. The tree is drawn to scale, with branch lengths in the same units as those of the evolutionary distances used to infer the phylogenetic tree. The evolutionary distances were computed using the Maximum Composite Likelihood method27 and are in the units of the number of base substitutions per site. The analysis involved 168 nucleotide sequences. All positions containing gaps and missing data were eliminated. There were a total of 203 positions in the final dataset. Evolutionary analyses were conducted in MEGA7.19 Bootstrap values were typically low (< 50) and are not shown. *Sequence with nearest identity to a sequence from mole rat gut, used for presumptive identification of clade. **Sequence with nearest identity to sequences from mole rat gut (from an unknown bacterial species and therefore not used for identification of clade). (A color version of this figure is available in the online journal.)

Sequences assigned to the Desulfovibrio clade

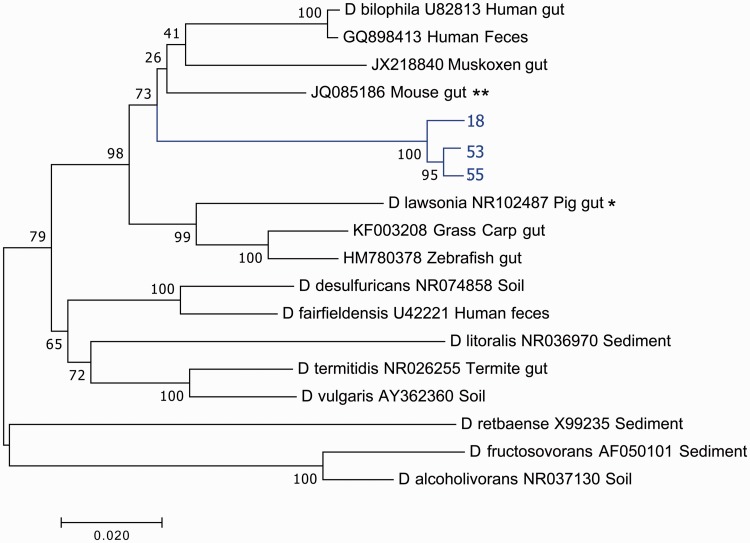

Figure 3 shows a cladogram containing 3 full length Cape dune mole rat-derived 16S rRNA sequences along with 15 other related sequences, 10 of which have been identified as belonging to the genus Desulfovibrio. The remaining five were obtained from unidentified microbes. The most closely related sequence based on homology was from an unidentified bacterium obtained from mouse gut (Figure 3). Substantial divergence of the Cape dune mole rat sequences from other sequences is observed, although little divergence (98% minimum sequence identity) within the sequences obtained from the Cape dune mole rat was observed (Figure 3, Table 1). The Cape dune mole rat sequences assigned as Desulfovibrio formed a single distinct clade, suggesting a possible substantial evolutionary drift of the microbiota during the course of evolution of mole rats. The same result was found regardless of alignment method or model used for tree formation, except that ambiguous results were obtained using CLC alignment and a Maximum Parsimony tree model. The results of alignment using V4 sequences only (Figure 4) yielded a similar result, with one single clade being identified. One sequence obtained from a mouse-associated bacterium was present in that clade, but that result was dependent on the alignment method used: alignments using both CLC Sequences Viewer and MUSCLE showed the sequence from the mouse-associated bacterium outside of the clade with all mole rat sequences.

Figure 3.

Desulfovibrio phylogenetic tree constructed with full length 16S rRNA sequences. Sequences from the mole rat are shown in light color, with nearest neighbors in black. The evolutionary history was inferred using the Neighbor-Joining method.25 The optimal tree with the sum of branch length = 0.69530967 is shown. The percentage of replicate trees in which the associated taxa clustered together in the bootstrap test (1000 replicates) are shown next to the branches.26 The tree is drawn to scale, with branch lengths in the same units as those of the evolutionary distances used to infer the phylogenetic tree. The evolutionary distances were computed using the Maximum Composite Likelihood method27 and are in the units of the number of base substitutions per site. The analysis involved 18 nucleotide sequences. All positions containing gaps and missing data were eliminated. There were a total of 1381 positions in the final dataset. Evolutionary analyses were conducted in MEGA7.19 *Sequence with nearest identity to a sequence from mole rat gut, used for presumptive identification of clade. **Sequence with nearest identity to sequences from mole rat gut (from an unknown bacterial species and therefore not used for identification of clade). (A color version of this figure is available in the online journal.)

Figure 4.

Desulfovibrio phylogenetic tree constructed with V4 16S rRNA sequences. Sequences from the mole rat are shown in light color, with nearest neighbors in black. The evolutionary history was inferred using the Neighbor-Joining method.25 The optimal tree with the sum of branch length = 3.39524189 is shown. The tree is drawn to scale, with branch lengths in the same units as those of the evolutionary distances used to infer the phylogenetic tree. The evolutionary distances were computed using the Maximum Composite Likelihood method27 and are in the units of the number of base substitutions per site. The analysis involved 157 nucleotide sequences. All positions containing gaps and missing data were eliminated. There were a total of 224 positions in the final dataset. Evolutionary analyses were conducted in MEGA7 (19). Bootstrap values were typically low (< 50) and are not shown. *Sequence with nearest identity to a sequence from mole rat gut, used for presumptive identification of clade. **Sequence with nearest identity to sequences from mole rat gut (from an unknown bacterial species and therefore not used for identification of clade). (A color version of this figure is available in the online journal.)

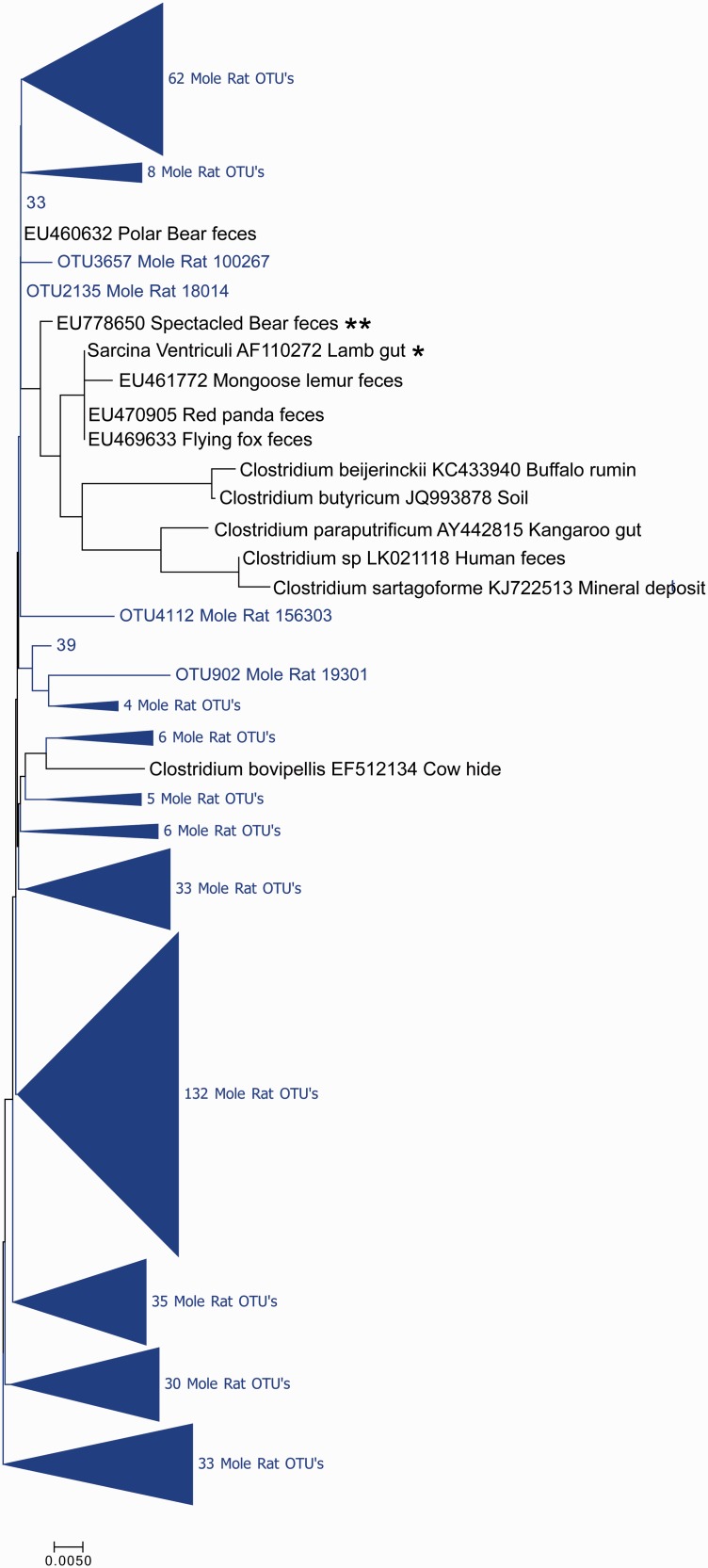

Sequences assigned to the Sarcina clade

Figure 5 shows a cladogram containing 2 full length Cape dune mole rat-derived 16S rRNA sequences along with 12 other related sequences. In this group of sequences, the nearest known related sequence to a Cape dune mole rat derived sequence was from Sarcina ventriculi from lamb gut. Other related sequences of known origin were from the genus Clostridium, but the group was presumptively assigned to the genus Sarcina based on the closest related sequence. The most closely related sequence based on homology was from an unidentified bacterium obtained from Spectacled Bear feces. In this clade, little divergence of the Cape dune mole rat sequences from other sequences was observed. In addition, the mole rat-derived sequence was relatively similar (99% minimum sequence identity) to the bear-derived sequence. The full length Cape dune mole rat sequences assigned as Sarcina formed a single, distinct clade, although this did not hold true when V4 sequences only were considered (Figure 6). That being said, the limited diversity in this group resulted in a low level of confidence in the resulting cladograms, and this clade serves as a dramatic contrast to the Treponeme and Desulfovibrio clades, which showed substantial differences from known sequences.

Figure 5.

Sarcina phylogenetic tree constructed with full length 16S rRNA sequences. Sequences from the mole rat are shown in light color, with nearest neighbors in black. The evolutionary history was inferred using the Neighbor-Joining method.25 The optimal tree with the sum of branch length = 0.17475581 is shown. The percentage of replicate trees in which the associated taxa clustered together in the bootstrap test (1000 replicates) are shown next to the branches.26 The tree is drawn to scale, with branch lengths in the same units as those of the evolutionary distances used to infer the phylogenetic tree. The evolutionary distances were computed using the Maximum Composite Likelihood method27 and are in the units of the number of base substitutions per site. The analysis involved 14 nucleotide sequences. All positions containing gaps and missing data were eliminated. There were a total of 1354 positions in the final dataset. Evolutionary analyses were conducted in MEGA7.19 *Sequence with nearest identity to a sequence from mole rat gut, used for presumptive identification of clade. **Sequence with nearest identity to sequences from mole rat gut (from an unknown bacterial species and therefore not used for identification of clade). (A color version of this figure is available in the online journal.)

Figure 6.

Sarcina phylogenetic tree constructed with V4 16S rRNA sequences. Sequences from the mole rat are shown in light color, with nearest neighbors in black. The evolutionary history was inferred using the Neighbor-Joining method.25 The optimal tree with the sum of branch length = 6.23522357 is shown. The tree is drawn to scale, with branch lengths in the same units as those of the evolutionary distances used to infer the phylogenetic tree. The evolutionary distances were computed using the Maximum Composite Likelihood method27 and are in the units of the number of base substitutions per site. The analysis involved 372 nucleotide sequences. All positions containing gaps and missing data were eliminated. There were a total of 185 positions in the final dataset. Evolutionary analyses were conducted in MEGA7.19 Bootstrap values were typically low (< 50) and are not shown. *Sequence with nearest identity to a sequence from mole rat gut, used for presumptive identification of clade. **Sequence with nearest identity to sequences from mole rat gut (from an unknown bacterial species and therefore not used for identification of clade). (A color version of this figure is available in the online journal.)

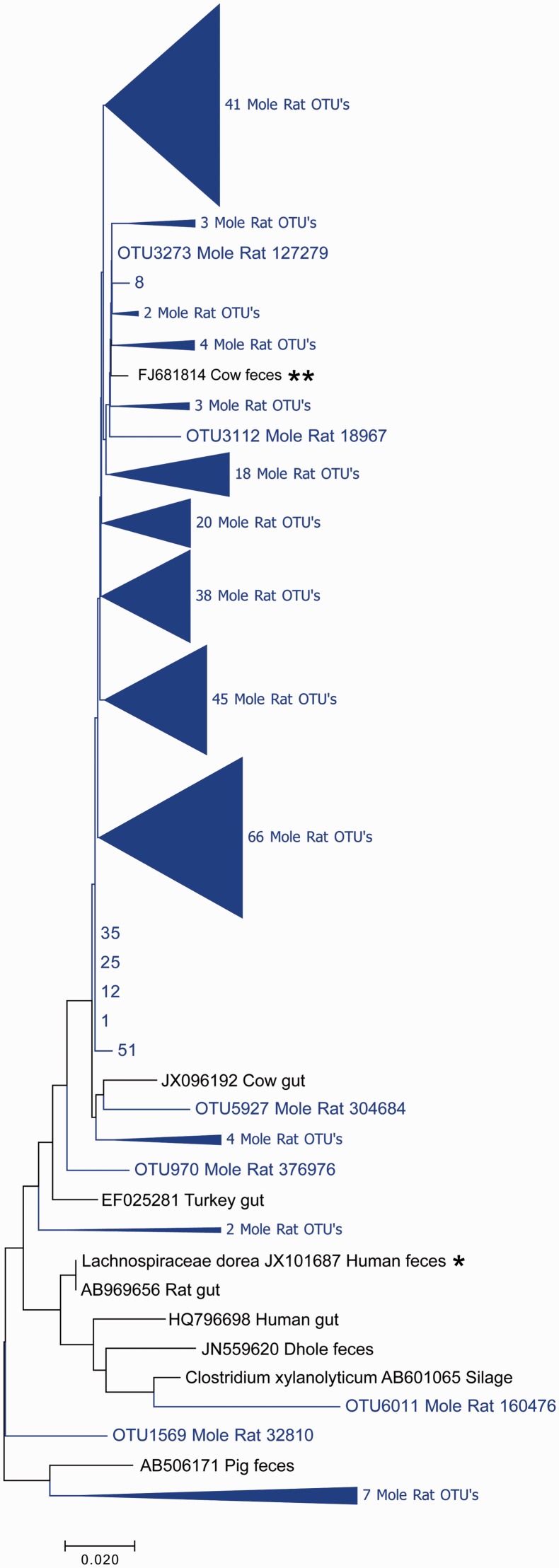

Sequences assigned to the Lachnospiraceae clade

Figure 7 shows a cladogram containing 6 full length Cape dune mole rat-derived 16S rRNA sequences along with 12 other related sequences. In this group of sequences, the nearest known related sequence to a Cape dune mole rat derived sequence was from Lachnospiraceae dorea from human feces. The only other related sequence of known origin in the cladogram was from the genus Clostridium, but the group was presumptively assigned to Lachnospiraceae based on the closest sequence. The sequences most closely related to the mole rat sequences were obtained from cow feces, as determined both by strict homology and by evolutionary relationships evident in the cladogram (Figure 7). This result was independent of alignment method and model of tree formation. In this clade, as with Sarcina, little divergence of the Cape dune mole rat sequences from other sequences was observed and little divergence (98% minimum sequence identity) within the sequences obtained from the Cape dune mole rat was observed (Figure 7, Table 1). As with sequences assigned to Sarcina, the full length Cape dune mole rat sequences assigned as Lachnospiraceae formed a single distinct clade, but this did not hold true when V4 sequences only were considered (Figure 8). Like sequences assigned to Sarcina, the limited diversity in this group resulted in a low level of confidence in the resulting cladograms, and this clade serves as a dramatic contrast to the Treponeme and Desulfovibrio clades, which showed substantial evolutionary drift from known sequences.

Figure 7.

Lachnospiraceae phylogenetic tree constructed with full length 16S rRNA sequences. Sequences from the mole rat are shown in light color, with nearest neighbors in black. The evolutionary history was inferred using the Neighbor-Joining method.25The optimal tree with the sum of branch length = 0.25150654 is shown. The percentage of replicate trees in which the associated taxa clustered together in the bootstrap test (1000 replicates) are shown next to the branches.26 The tree is drawn to scale, with branch lengths in the same units as those of the evolutionary distances used to infer the phylogenetic tree. The evolutionary distances were computed using the Maximum Composite Likelihood method27 and are in the units of the number of base substitutions per site. The analysis involved 15 nucleotide sequences. All positions containing gaps and missing data were eliminated. There were a total of 1277 positions in the final dataset. Evolutionary analyses were conducted in MEGA7.19 *Sequence with nearest identity to a sequence from mole rat gut, used for presumptive identification of clade. **Sequence with nearest identity to sequences from mole rat gut (from an unknown bacterial species and therefore not used for identification of clade). (A color version of this figure is available in the online journal.)

Figure 8.

Lachnospiraceae phylogenetic tree constructed with V4 16S rRNA sequences. Sequences from the mole rat are shown in light color, with nearest neighbors in black. The evolutionary history was inferred using the Neighbor-Joining method.25 The optimal tree with the sum of branch length = 6.81596946 is shown. The tree is drawn to scale, with branch lengths in the same units as those of the evolutionary distances used to infer the phylogenetic tree. The evolutionary distances were computed using the Maximum Composite Likelihood method27 and are in the units of the number of base substitutions per site. The analysis involved 316 nucleotide sequences. All positions containing gaps and missing data were eliminated. There were a total of 204 positions in the final dataset. Evolutionary analyses were conducted in MEGA7.19 Bootstrap values were typically low (<50) and are not shown. *Sequence with nearest identity to a sequence from mole rat gut, used for presumptive identification of clade. **Sequence with nearest identity to sequences from mole rat gut (from an unknown bacterial species and therefore not used for identification of clade). (A color version of this figure is available in the online journal.)

Sequences presumptively assigned to the Clostridium, Prevotella, Peptostreptococcaceae, and Anaerocella clades

A total of six clones were isolated from four clades (three genus level and one family level), and partial length 16S rRNA sequences were determined. Trees were not constructed from these partial sequences, but nearest neighbor sequences were determined. Sequences presumptively assigned to Clostridium, Prevotella, Peptostreptococcaceae, and Anaerocella as described in the Methods were most closely related to sequences found in cow feces, pig feces, rat cecum, and sheep rumen, respectively. Of note was the fact that there were substantial differences between sequences from these four clades and previously identified sequences, particularly for Peptostreptococcaceae (92.9% similarity to nearest sequence), and Anaerocella (92.4% identity to nearest known sequence).

Discussion

Treponemes within the mole rat showed evidence of a substantial adaptive radiation, with considerable diversity found within the mole rat (81% minimum sequence identity) as well as substantial divergence (87.3% average sequence identity to nearest neighbor) from previously identified organisms (Table 1). Of the clades examined, this clade showed the greatest divergence from previously identified species, although Desulfovibrio sequences found in the mole rat also revealed substantial differences from previously described sequences (91.3% sequence identity to nearest neighbor; Table 1). However, the low number of full length sequence information from Desulfovibrio limits conclusions about the degree of adaptive radiation in that clade within the mole rat. These findings suggest that at some point during evolutionary history, the mole rat gut offered unexplored niche space that was particularly well suited for Treponemes and perhaps Desulfovibrio. Based on significant differences between sequences found in the mole rat gut and previously determined sequences from other sources (Table 1), it also seems likely that bacteria related to Peptostreptococcaceae, Anaerocella, and perhaps Prevotella may have extensively evolved in mole rats.

In contrast to the picture obtained with Treponemes and Desulfovibrio, Lachnospiraceae and especially Sarcina exhibited very limited diversity and differences from previously identified species, with 97.0% and 99.2% average sequence identity to nearest neighbors, respectively (Table 1). This suggests that niche space for Lachnospiraceae and Sarcina, both closely related to Clostridia (Figures 5 and 7), in the mole rat gut is relatively more similar to that found in the gut of other species, and perhaps less diverse in nature than niche space for Treponemes and Desulfovibrio. This observation might suggest that Clostridia and related species occupy a niche in the gut that is fundamental to the gut itself, dependent on such ubiquitous intestinal factors as mucus, epithelial cells and immune components that are largely independent of diet. With that in mind, we suggest that some microbial species of the gut may be “housekeeping” organisms, present regardless of diet, whereas other species may be more dependent on diet.

Several factors point toward the robust nature of the results obtained in this study. First, cladograms were consistent regardless of the method of analysis used to produce them. The method of alignment made a slight difference, with the SSU-ALIGN algorithm providing slightly less parsimonious results in some cases than did other methods of alignment evaluated. This may suggest that the SSU-ALIGN method is not ideally suited for the data we analyzed, but the lack of parsimony using SSU-ALIGN was minor, supporting the overall conclusions of the study pointing at substantial adaptive radiation in some clades but not others. A second line of evidence pointing toward the validity of the study is the fact that considerable clade-to-clade variation was observed. While some clades showed substantial divergence from related sequences in the database, others showed very little. This observation suggests that the divergence observed in clade-specific and therefore not an artifact of the methodology used.

Whether this adaptive radiation occurred early in the evolution of the mole rats remains in question, since sequence information from mole rats is very limited. Treponeme sequences from the gut of the Cape dune mole rat form a common clade, as shown in Figure 1, consistent with the view that Treponemes have co-evolved with mole rats. At the same time, Treponeme sequences from the gut of the Cape dune mole rat were substantially diverged (minimum 90% sequence identity) from sequences previously found in the gut of the naked mole rat. The Treponeme sequence from the naked mole rat remained isolated from sequences of the Cape dune mole rat even when taking into account the shorter length V4 sequences obtained by Illumina sequencing (Figure 2). Thus, it is possible that much of the adaptive radiation within the Treponeme clade happened later in the evolution of the mole rats. It is expected that additional work will shed further light on this issue.

Microbiota can be derived from the microbiota of host ancestors, as is known to have happened in the microbiotas of extant primates,6 or microbiota can be obtained by lateral transmission from other hosts, as is known to have happened with Firmicute populations in some termites.28 Alternatively, microbiota may be derived from organisms acquired from the environment. We have previously noted that “the majority of the microorganisms found in the ceca of the (Cape dune) mole rats unexpectedly possessed an elongated and often spirochete-like morphology.”29 The other animal which is known to contain a microbiota with this morphology is the dampwood termite (Zootermopsis nevadensis).30 This observation suggested to us the hypothesis that the Cape dune mole rat may have acquired its microbiota, at least in part, via lateral transfer from a carbohydrate digesting insect.

That hypothesis is not supported here, with organisms from the mole rat gut consistently showing the closest relationship with organisms other than those found in the termite gut. Sequences of Treponemes, Lachnospiraceae, and Clostridium in the gut of the mole rat were most closely related to bacterial sequences obtained from the guts or feces of cows, suggesting that evolution of the mole rat microbiota may have been acquired in part by transfer from grazing animals prior to the adaptive radiation observed here. Sequences of Sarcina, Anaerocella, and Prevotella in the gut of the mole rat were most closely related to bacterial sequences obtained from bear gut, sheep rumen, and pig feces, respectively, suggesting that evolution of the mole rat microbiota may have been a complex process involving a number of acquisition events. Desulfovibrio and Peptostreptococcaceae-related 16S rRNA sequences were closely related to organisms found in mice and in rats, respectively, suggesting that these clades could have been maintained in the rodent lineage rather than acquired by lateral transfer. Thus, these data support the idea that convergent evolution is primarily responsible for the morphological similarities between the microbiota of the mole rat and termite guts. Although it might be hypothesized that the wood-derived cellulose and the geophyte-derived cellulose in the diet of the termite and the mole rat, respectively, drove the evolution of morphological distinctiveness, it is not known by what mechanism a woody, cellulose-rich diet might have driven such evolution.

In the Cape dune mole rat gut, we observed preponderances of Clostridia-related Firmicutes (Sarcina and Lachnospiraceae) and, depending on the methodology (Sanger versus Illumina), Proteobacteria belonging to the genus Desulfovibrio. Although this represents the first examination of the microbiota of the Cape dune mole rat, the microbiota of a domesticated naked mole rat from the St. Louis Zoo has been previously evaluated by analysis of 322 full length 16s sequences.3 About 5% of the sequences from the naked mole rat were attributed to Spirochaetes, consistent with the results of this study. However, in contrast to the results observed in this study, preponderances of gammaproteobacteria (∼48% of total sequences), Actinobacteria (∼27% of total sequences), and Deferribacteres (∼11% of total sequences) were identified in the naked mole rat. Thus, differences between the Cape dune mole rat’s microbiota observed in this study and the previously published microbiota of the naked mole rat are substantial and entail more than 75% of the total microbiota described here. These differences might be attributed to the different species, to the methodology used, or to differences in the diets of the two animals. Indeed, domesticated mole rats typically subsist on a diet of primarily sweet potato, and diet alteration is known to dramatically alter microbiota composition.1–3 For whatever reason, large study-to-study differences in microbiota compositions of vertebrate species are not new,10 indicating the importance of multiple studies using multiple animals before any conclusions about microbiota compositions in a population can be ascertained with any degree of certainty. That being said, this study was not designed to probe the microbiota composition in a population of mole rats, but rather to probe the origins of the microbiota in an animal that has dietary habits which differ markedly from typical related species (i.e. typical rodents).

The finding that cellulose digesting microbes have substantially evolved in the mole rat suggests that these organisms might be of substantial importance for future biotech applications. Indeed, considerable interest has surrounded the potential for cellulose digesting organisms to be harnessed for energy production.31,32 The finding of extensive adaptive radiation in this community suggests that exploration of this niche space or other previously uncharacterized niche spaces may yield novel organisms that could aid greatly in harnessing cellulose as a renewable resource31,32 or perhaps utilization of cellulose digesting non-ruminant animals as a sustainable food source for the human population . However, the present work is also of some interest for basic science.

Mitochondrial 12S rRNA gene studies suggest that New World caviomorpha and Old World phiomorpha separated from a common ancestor around 33–39 million years ago. African mole rats (Bathyergidae) are subterranean Hystricomorph rodents found in the latter group (Old world phiomorpha) and have three close relatives, namely Petromuridae (dassie rats), Thryonomyidae (cane rats) and Hystricidae (Old World porcupines).12 Based on mitochondrial cytochrome b and 12s rRNA molecular clocks, the eusocial naked mole rat, Heterocephalus glaber represents the oldest lineage of the African mole rats, while the solitary Bathyergus genus (together with Georychus) represent the third oldest lineage.33 While the habitats and soil types in which extant Bathyergids live and burrow may differ between species, their herbivorous diets remain remarkably similar in that all consume underground storage organs of plants including roots, corms, and tubers.12 In addition to geophytes, the two Bathyergus species (B. suillus and B. janetta) consume above ground portions of grasses and other vegetation.12 Furthermore, the closest phylogenetic relatives of Bathyergidae are all herbivorous, ingesting roots, fruit, bulbs, and grasses.34 The extinct Bathyergus hendeyi, which probably represents an early precursor to the two modern Bathyergus species, all share similarities in teeth morphology35 which suggest that B. hendeyi was also herbivorous. Mole rat fossil teeth indicate herbivory, probably from the earliest divergence of Bathyergids (Personal communication from Faulkes to SHK, used with permission).

Although the diets of mole rats are atypical of rodents, various species belonging to New World caviomorpha, such as the New World porcupine, can ingest roots and stems. With this in mind, lateral transfer of cellulose-digesting microbes from grazing animals may have happened before mole rats and other extanct animals separated from a common ancestor. Future studies involving the analysis of microbiotas from closely related animals (rock rats, cane rats, old world porcupines, and various species of Caviomorpha) are expected to provide insight into this issue.

Authors’ contributions

All authors participated in the design, interpretation of the studies and analysis of the data and review of the manuscript; LR, RAH, ZEH, SHK, DEB, and EAM conducted the experiments, SSL SHK and DEB supplied critical reagents, and WP, LR and SHK wrote the manuscript.

DECLARATION OF CONFLICTING INTERESTS

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

FUNDING

This work was supported in part by the Fannie E. Ripple foundation.

References

- 1.David LA, Maurice CF, Carmody RN, Gootenberg DB, Button JE, Wolfe BE, Ling AV, Devlin AS, Varma Y, Fischbach MA, Biddinger SB, Dutton RJ, Turnbaugh PJ. Diet rapidly and reproducibly alters the human gut microbiome. Nature 2014; 505:559–63 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Muegge BD, Kuczynski J, Knights D, Clemente JC, Gonzalez A, Fontana L, Henrissat B, Knight R, Gordon JI. Diet drives convergence in gut microbiome functions across mammalian phylogeny and within humans. Science 2011; 332:970–4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ley RE, Hamady M, Lozupone C, Turnbaugh PJ, Ramey RR, Bircher JS, Schlegel ML, Tucker TA, Schrenzel MD, Knight R, Gordon JI. Evolution of mammals and their gut microbes. Science 2008; 320:1647–51 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McKenney EA, Rodrigo A, Yoder AD. Patterns of gut bacterial colonization in three primate species. PLoS One 2015; 10:e0124618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Li T, Long M, Li H, Gatesoupe FJ, Zhang X, Zhang Q, Feng D, Li A. Multi-omics analysis reveals a correlation between the host phylogeny, gut microbiota and metabolite profiles in cyprinid fishes. Front Microbiol 2017; 8:454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ochman H, Worobey M, Kuo CH, Ndjango JB, Peeters M, Hahn BH, Hugenholtz P. Evolutionary relationships of wild hominids recapitulated by gut microbial communities. PLoS Biol 2010; 8:e1000546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tzeng T-D, Pao Y-Y, Chen P-C, Weng FC-H, Jean WD, Wang D. Effects of host phylogeny and habitats on gut microbiomes of oriental river prawn (macrobrachium nipponense). PLoS One 2015; 10:e0132860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tai V, James ER, Nalepa CA, Scheffrahn RH, Perlman SJ, Keeling PJ. The role of host phylogeny varies in shaping microbial diversity in the hindguts of lower termites. Appl Environ Microbiol 2015; 81:1059–70 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ley RE, Lozupone CA, Hamady M, Knight R, Gordon JI. Worlds within worlds: evolution of the vertebrate gut microbiota. Nat Rev Micro 2008; 6:776–88 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Li Y, Guo W, Han S, Kong F, Wang C, Li D, Zhang H, Yang M, Xu H, Zeng B, Zhao J. The evolution of the gut microbiota in the giant and the red pandas. Sci Rep 2015; 5:10185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Barker CJ, Gillett A, Polkinghorne A, Timms P. Investigation of the koala (Phascolarctos cinereus) hindgut microbiome via 16S pyrosequencing. Vet Microbiol 2013; 167:554–64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bennett NC, Faulkes CG. African mole rats: ecology and eusociality. Cambridge: Press Syndicate of the University of Cambridge, 2000 [Google Scholar]

- 13.Watt JM, Breyer-Brandwijk MG. The medicinal and poisonous plants of southern and eastern Africa: being an account of their medicinal and other uses, chemical composition, pharmacological effects and toxicology in man and animal. Edinburgh: E. & S. Livingstone,1962 [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lovegrove BG, Jarvis JUM. Coevolution between mole rats (Bathyergidae) and a geophyte, Micranthus (Iridaceae). Cimbebasia 1986; 8:79–85 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bennett NC, Jarvis JUM. Coefficients of digestibility and nutritional values of geophytes and tubers eaten by southern African mole rats (Rodentia: Bathyergidae). J Zoology 1995; 236:189–98 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Boratyn GM, Schaffer AA, Agarwala R, Altschul SF, Lipman DJ, Madden TL. Domain enhanced lookup time accelerated BLAST. Biol Direct 2012; 7:12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nawrocki EP. Structural RNA homology search and alignment using covariance models. Saint Louis, MO: Washington University in Saint Louis, School of Medicine, 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 18.Edgar RC. MUSCLE: multiple sequence alignment with high accuracy and high throughput. Nucleic Acids Res 2004; 32:1792–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kumar S, Stecher G, Tamura K. MEGA7: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 7.0 for bigger datasets. Mol Biol Evol 2016; 33:1870–4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Caporaso JG, Lauber CL, Walters WA, Berg-Lyons D, Huntley J, Fierer N, Owens SM, Betley J, Fraser L, Bauer M, Gormley N, Gilbert JA, Smith G, Knight R. Ultra-high-throughput microbial community analysis on the Illumina HiSeq and MiSeq platforms. ISME J 2012; 6:1621–4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Aronesty E. ea-utils: command-line tools for processing biological sequencing data. 2011, Available at: https://github.com/ExpressionAnalysis/ea-utils [Google Scholar]

- 22.Caporaso JG, Kuczynski J, Stombaugh J, Bittinger K, Bushman FD, Costello EK, Fierer N, Pena AG, Goodrich JK, Gordon JI, Huttley GA, Kelley ST, Knights D, Koenig JE, Ley RE, Lozupone CA, McDonald D, Muegge BD, Pirrung M, Reeder J, Sevinsky JR, Turnbaugh PJ, Walters WA, Widmann J, Yatsunenko T, Zaneveld J, Knight R. QIIME allows analysis of high-throughput community sequencing data. Nat Methods 2010; 7:335–6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kuczynski J, Stombaugh J, Walters WA, Gonzalez A, Caporaso JG, Knight R. Using QIIME to analyze 16S rRNA gene sequences from microbial communities. Curr Protoc Bioinform 2011; Chapter 10:Unit 10.7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Edgar RC. Search and clustering orders of magnitude faster than BLAST. Bioinformatics 2010; 26:2460–1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Saitou N, Nei M. The neighbor-joining method – a new method for reconstructing phylogenetic trees. Mol Biol Evoln 1987; 4:406–25 .[Mismatch] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Felsenstein J. Confidence limits on phylogenenies: an approach using the bootstrap. Evolution 1985; 39:783–91 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tamura K, Nei M, Kumar S. Prospects for inferring very large phylogenies by using the neighbor-joining method. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2004; 101:11030–5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.He S, Ivanova N, Kirton E, Allgaier M, Bergin C, Scheffrahn RH, Kyrpides NC, Warnecke F, Tringe SG, Hugenholtz P. Comparative metagenomic and metatranscriptomic analysis of hindgut paunch microbiota in wood- and dung-feeding higher termites. PLoS One 2013; 8:e61126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kotze SH, Holzknecht ZE, Thomas AD, Everett ML, Taylor S, Duckett LD, Whitesides J, McDermott P, Lin SS, Parker W. Spontaneous bacterial cell lysis and biofilm formation in the colon of the Cape Dune mole rat and the laboratory rabbit. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 2011; 90:1773–83 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wertheim M, Leadbetter J. The ecology of the termite gut: an Interview with Jared Leadbetter. The Cabinet 2007;25 [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lynd LR, Weimer PJ, van Zyl WH, Pretorius IS. Microbial cellulose utilization: fundamentals and biotechnology. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 2002; 66:506–77 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Carere CR, Sparling R, Cicek N, Levin DB. Third generation biofuels via direct cellulose fermentation. Int J Mol Sci 2008; 9:1342–60 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Faulkes CG, Bennett NC, Cotterill FPD, Stanley W, Mgode GF, Verheyen E. Phylogeography and cryptic diversity of the solitary-dwelling silvery mole rat, genus Heliophobius (family: Bathyergidae). J Zool 2011; 285:324–38 [Google Scholar]

- 34.George W. The diet of Petromus Typicus (Petromuridae, Rodentia) in the Augrabies falls National Park 1981; 24:159–167 [Google Scholar]

- 35.Denys C. Phylogenetic implications of the existence of two modern genera of Bathyergidae genera (Rodentia, Mammalia) in the Pliocene site of Langebaanweg (South Africa). Ann South Afr Mus 1998; 105:265–86 [Google Scholar]