Key Points

Question

What outcomes are associated with topical calcineurin inhibitor (tacrolimus and pimecrolimus) therapy in patients with vitiligo?

Findings

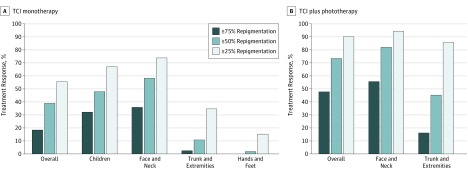

In this meta-analysis of 46 studies including 1499 patients, topical calcineurin inhibitor monotherapy produced an at least mild response in 55.0% of the patients, at least moderate response in 38.5%, and a marked response in 18.1% after a median treatment duration of 3 months. At least moderate responses were achieved in 47.3% of children, 57.5% of lesions on the face and neck, and in 72.9% of participants when topical calcineurin inhibitors were used in combination with phototherapy.

Meaning

Topical calcineurin inhibitors appear to have significant therapeutic effects on vitiligo and it seems that their use should be encouraged in patients with vitiligo.

Abstract

Importance

Topical calcineurin inhibitors (TCIs), including tacrolimus and pimecrolimus, have been widely used for the treatment of vitiligo; however, the efficacy of TCI monotherapy is often underestimated.

Objectives

To estimate the treatment responses to both TCI monotherapy and TCI accompanied by phototherapy for vitiligo, based on relevant prospective studies, and to systematically review the mechanism of action of TCIs for vitiligo treatment.

Data Sources

A comprehensive search of the MEDLINE, Embase, Web of Science and Cochrane Library databases from the date of database inception to August 6, 2018, was conducted. The main key words used were vitiligo, topical calcineurin inhibitor, tacrolimus, pimecrolimus, and FK506.

Study Selection

Of 250 studies initially identified, the full texts of 102 articles were assessed for eligibility. A total of 56 studies were identified: 11 studies on the TCI mechanism, 36 studies on TCI monotherapy, 12 studies on TCI plus phototherapy, and 1 study on TCI maintenance therapy.

Data Extraction and Synthesis

Two reviewers independently extracted data on study design, patients, intervention characteristics, and outcomes. Random-effects meta-analyses using the generic inverse variance weighting were performed for the TCI monotherapy and TCI plus phototherapy groups.

Main Outcomes and Measures

The primary outcomes were the rates of at least mild (≥25%), at least moderate (≥50%), and marked (≥75%) repigmentation responses to treatment. These rates were calculated by dividing the number of participants in an individual study who showed the corresponding repigmentation by the total number of participants who completed that study.

Results

In the 56 studies included in the analysis, 46 (1499 patients) were selected to evaluate treatment response. For TCI monotherapy, an at least mild response was achieved in 55.0% (95% CI, 42.2%-67.8%) of 560 patients in 21 studies, an at least moderate response in 38.5% (95% CI, 28.2%-48.8%) of 619 patients in 23 studies, and a marked response in 18.1% (95% CI, 13.2%-23.1%) of 520 patients in 19 studies after median treatment duration of 3 months (range, 2-7 months). In the subgroup analyses, face and neck lesions showed an at least mild response in 73.1% (95% CI, 32.6-83.5%) of patients, and a marked response in 35.4% (95% CI, 24.9-46.0%) of patients. For TCI plus phototherapy, an at least mild response to TCI plus phototherapy was achieved in 89.5% (95% CI, 81.1-97.9%) of patients, and a marked response was achieved in 47.5% (95% CI, 30.6-64.4%) of patients.

Conclusions and Relevance

The use of TCIs, both as a monotherapy and in combination with phototherapy, should be encouraged in patients with vitiligo.

This systematic review and meta-analysis evaluates studies on the use of topical calcineurin inhibitors for treatment of vitiligo in adults and children.

Introduction

Vitiligo is a common depigmenting skin disorder affecting 0.5% to 1% of the population and is associated with low self-esteem and social stigma.1,2 Among various treatment options, topical calcineurin inhibitors (TCIs) are recommended as first-line treatments for limited forms of vitiligo.3,4 Moreover, combining TCIs with phototherapy has been shown to enhance the treatment response compared with phototherapy alone.5,6 Despite ample evidence for the use of TCIs for the treatment of vitiligo,5,7,8 the therapeutic efficacy of TCI monotherapy is often underestimated, and, to our knowledge, the mechanism of action of TCIs has yet to be established. In the present study, we performed a systematic review and meta-analysis of all relevant prospective studies to evaluate treatment responses to TCI monotherapy and TCI plus phototherapy for vitiligo.

Methods

A systematic review and meta-analyses were performed in the following 4 areas: (1) mechanism of action, (2) treatment responses (TCI monotherapy and TCI plus phototherapy), (3) the use of TCIs for maintenance therapy, and (4) safety. The study was conducted according to the PRISMA guideline.9

Databases

We performed a comprehensive search using predefined search terms (eTable 1 in the Supplement) in MEDLINE, Embase, Web of Science, and Cochrane Library databases from inception to August 6, 2018. The main search terms were vitiligo, topical calcineurin inhibitor, tacrolimus, pimecrolimus, and FK506. All prospective and experimental studies were included with no language restriction.

Study Selection

Selection for the mechanism of action included both in vivo and in vitro experimental studies that have investigated the therapeutic mechanism of TCIs related to vitiligo or melanocytes. Selection for TCI treatment response studies was based on the following inclusion criteria (eTable 2 in the Supplement): (1) prospective study, including randomized and nonrandomized clinical trials and open-label trials; (2) participants of all age groups with a diagnosis of vitiligo; (3) at least 1 TCI monotherapy group or TCI plus phototherapy group; (4) at least 10 participants or 10 patches in each treatment arm, regardless of the dropout rate; (5) outcomes measured based on all vitiligo lesions on the participant’s whole body or each of the patches; and (6) outcomes measured according to the degree of repigmentation on a quartile scale (≥25%, ≥50%, and ≥75%). The types of phototherapy were restricted to narrowband UV-B (NBUVB) and excimer light or laser (EL). Studies that used TCI treatment in combination with any other intervention, such as systemic corticosteroids and antioxidant supplements, were excluded. The selection for maintenance therapy included all prospective studies in which TCIs were used to maintain therapeutic efficacy in patients who had completed treatment.

Two reviewers (J.H.L. and H.S.K.) independently identified relevant articles by searching titles and abstracts. If the abstract did not provide enough information to determine eligibility, the full text was reviewed.

Data Extraction, Synthesis, and Subgroup Analyses

Mechanism of Action

Studies related to the TCI mechanism of action were summarized as study design, participants, brief summary, and conclusion. The mechanism of action was categorized as follows: (1) immune suppression, (2) melanocyte migration and proliferation, (3) melanogenesis, and (4) other.

Treatment Response

The treatment response was evaluated as the degree of repigmentation based on a quartile scale: an at least mild response (≥25% repigmentation), at least moderate response (≥50% repigmentation), and marked response (≥75% repigmentation). The treatment response rates were calculated as the number of participants who achieved the corresponding degree of repigmentation divided by the total number of participants who completed the individual study. The degree of repigmentation was evaluated based on all lesions in each participant or individual patches.

Meta-analyses were carried out separately according to treatment protocol: TCI monotherapy or TCI plus phototherapy. Subgroup analyses were performed to investigate the treatment response to TCIs in children and according to body site, categorized as face and neck, trunk and extremities, and hands and feet. Outcomes for subgroups according to body site included studies containing at least 10 participants; studies with fewer than 10 participants per body part were excluded.

Maintenance Therapy

Studies of TCI maintenance therapy were reviewed and the following information was extracted: study design, number and characteristics of the participants, type of TCI used, previous treatment modalities, treatment frequency and duration, and numbers of participants with depigmentation.

Safety

We investigated all adverse events reported in the included studies of TCI monotherapy. We collected a list of common adverse events, pooled the frequencies, and identified serious adverse events.

Statistical Analysis

The rates of the corresponding treatment responses of the included studies were pooled by the generic inverse variance weighting and were combined using a random-effects model.10 Heterogeneity was assessed using the I2 value,11 and publication bias was evaluated using a funnel plot of sample size against log odds.12 Meta-analyses were conducted in metagen package of R, version 3.5.1 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing) software.

Results

Search Results

A total of 250 records were identified through computerized database searches, of which 148 articles were removed after 2 independent reviewers (J.H.L. and H.S.K.) screened the titles and abstracts (Figure 1). A total of 102 full-text articles were assessed for eligibility, 46 of which were excluded for the following reasons: (1) the use of other interventions, such as combination therapy with topical corticosteroids (n = 1), (2) retrospective or observational study (n = 8), (3) fewer than 10 participants included (n = 11), (4) vitiligo refractory to previous conventional treatment (n = 2), (5) difference in outcome measures (n = 14), (6) duplicate reports (n = 9), and (7) not available after contacting authors (n = 1). Fifty-six studies fulfilled the inclusion criteria and were included in this review.

Figure 1. Flow Diagram Showing How Eligible Studies Were Identified .

Mechanism of Action

We identified 11 studies on the mechanism of action of TCIs (Table 1).8,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22 First, TCIs downregulate proinflammatory cytokines, such as tumor necrosis factor,8 and induce anti-inflammatory cytokines, such as interleukin (IL)-10, in the vitiligo lesions.13 Second, calcineurin inhibitors promote the migration and proliferation of melanocytes and melanoblasts15,18,19 through increasing matrix metalloproteinase (MMP-2 and MMP-9) levels17 and inducing endothelin B receptor expression in melanoblasts.16 In an in vitro study, proliferation of melanocytes was significantly enhanced by tacrolimus-treated keratinocyte supernatant.14 Third, calcineurin inhibitors induce melanogenesis14,15,19,20 through increasing tyrosinase expression15,19,20 and dopa oxidase activity.15 Finally, topical tacrolimus reduced oxidative stress and improved antioxidant capacity in 20 patients with vitiligo who applied topical tacrolimus twice daily for 7 months in a clinical study.22

Table 1. Summary of Possible Mechanisms of TCI in Vitiligo.

| Source | Study Design | TCI Used | Brief Description | Conclusion |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Immune Suppression | ||||

| Grimes et al,8 2004 | In vivo, human | Tacrolimus | After 24-wk treatment with topical tacrolimus in 19 patients, elevated lesional TNF expression was decreased; while IFN-γ and IL-10 were not changed | Decrease of TNF; no change of IFN-γ and IL-10 |

| Taher et al,13 2009 | In vivo, human | Tacrolimus | After 3-mo treatment with topical tacrolimus in 20 patients, lesional IL-10 expression was significantly increased | Increase of IL-10 |

| Melanocyte Migration and Proliferation | ||||

| Lan et al,14 2005 | In vitro, cultured MCs and MBs (NCCmelb4, NCCmelan5) | Tacrolimus | Proliferation of MCs and MBs was significantly enhanced; SCF and MMP-9 activity were increased with KC supernatant; tacrolimus did not alter cell migration without KC supernatant | Proliferation of MCs and MBs with KC supernatant; increase of SCF and MMP-9 with KC supernatant |

| Kang and Choi,15 2006 | In vitro, cultured MCs | Tacrolimus | Tacrolimus enhanced MC migration in cell migration assay and Boyden chamber assay | Increased MC migration |

| Lan et al,16 2011 | In vitro, cultured MBs (NCCmelb4) | Tacrolimus | Tacrolimus stimulated expression of PKA, PKC, and p38 MAPK of MBs, but cell motility was not enhanced; and dose dependently upregulated expression of ETBR; tacrolimus and ET-3 combination stimulated MB mobility | Induction of ETBR in MBs; increase of MB migration with ET-3 |

| Lee et al,17 2013 | In vitro, cultured MCs | Tacrolimus | Tacrolimus induced migration of MCs with Boyden chamber transwell migration assay and stimulated activities of MMP-2 and MMP-9 | Increase of MC migration; increase of MMP-2 and MMP-9 |

| Jung and Oh,18 2016 | In vitro, cultured MCs and melanoma cells (B16F10) | Tacrolimus | Tacrolimus enhanced cell spreading on laminin-332 and increased migration in both MCs and melanoma cells. Tacrolimus also increased the expression of syndecan-2 | Increase of MC migration and increase of syndecan-2 |

| Xu et al,19 2017 | In vitro, cultured MCs | Pimecrolimus | Pimecrolimus stimulates MC migration in wound scratch assay and transwell assays | Increased MC migration |

| Melanogenesis | ||||

| Lan et al,14 2005 | In vitro, cultured MCs and MBs (NCCmelb4, NCCmelan5) | Tacrolimus | Tacrolimus enhanced melanin formation in MCs but did not significantly alter the melanogenic capacity of MBs | Increased melanin contents |

| Kang and Choi,15 2006 | In vitro, cultured MCs | Tacrolimus | Tacrolimus increased melanin contents, level of dopa oxidase activity, and expression of tyrosinase | Increased melanin contents, dopa oxidase, and tyrosinase |

| Park et al,20 2016 | In vitro, cultured MCs | Tacrolimus | Tacrolimus plus excimer laser increased melanin contents and tyrosinase expression than either treatment alone; however, expression of TRP-2 protein was not changed; TRP-1 level was elevated in cells treated with tacrolimus or the combination treatment | Increase of melanin contents and tyrosinase with combination of excimer laser; no change in TRP-2; increase of TRP-1 |

| Jung et al,21 2016 | In vitro, cultured MCs and melanoma cells (B16F10, MNT-1) | Tacrolimus | Tacrolimus increased the melanin content and promoted melanosome maturation by increasing melanosomal pH and enhanced UV-B–mediated melanosome secretion and the uptake of melanosomes by KCs | Increase of melanin contents and promoted melanosome maturation; increased transfer of melanosome to KCs |

| Xu et al,19 2017 | In vitro, cultured MCs | Pimecrolimus | Pimecrolimus significantly increased intracellular tyrosinase activity, MITF expression, and content of melanin | Increased melanin contents, tyrosinase, and MITF |

| Antioxidative Effect | ||||

| Lubaki et al,22 2010 | In vivo, human | Tacrolimus, pimecrolimus | After treatment with topical tacrolimus in 20 patients, significant reduction of oxidative stress and increased antioxidant capacity in serum observed with BAP test and D-Roms test; those treated with pimecrolimus did not show any significant changes | Decrease of serum oxidative stress with topical tacrolimus; no change of serum oxidative stress with topical pimecrolimus |

Abbreviations: BAP, biological antioxidant potential; ET, endothelin; ETBR, endothelin B receptor; IFN, interferon; KC, keratinocyte; MAPK, mitogen-activated protein kinase; MB, melanoblast, MC, melanocyte; MITF, microphthalmia-associated transcription factor; MMP, matrix metalloproteinase; PKA, protein kinase A; PKC, protein kinase C; SCF, stem-cell factor; TCI, topical calcineurin inhibitor; TNF, tumor necrosis factor.

Treatment Response to TCI Monotherapy

We analyzed 46 studies involving 1499 patients to evaluate treatment response to TCI therapy (Table 2); 36 studies with 941 patients were included in the TCI monotherapy group7,8,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,64 and 12 studies with 558 patients were in the TCI plus phototherapy group.30,36,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,65 The median duration of treatment was 3 months (range, 2-7 months). An at least mild response (≥25% repigmentation) to TCI monotherapy was achieved in 55.0% (95% CI, 42.2%-67.8%) of 560 patients in 21 studies (Figure 2) (Table 3) (eFigure in the Supplement),7,8,22,23,24,25,27,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,37,38,39,41,42,43,64 an at least moderate response (≥50% repigmentation) was achieved in 38.5% (95% CI, 28.2%-48.8%) of 619 patients in 23 studies,7,8,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43 and a marked response (≥75% repigmentation) was achieved in 18.1% (95% CI, 13.2%-23.1%) of 520 patients in 19 studies.7,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,37,38,39,41,42,43 In children, an at least mild response to TCI monotherapy was achieved in 66.4% (95% CI, 43.2%-89.7%) of 162 patients in 5 studies,7,25,32,35,41 and a marked response to TCI monotherapy was achieved in 31.7% of patients (31.7%; 95% CI, 6.7%-56.8%) in 5 studies.7,25,32,35,41

Table 2. Characteristics of Prospective Studies on TCIs for Vitiligo Treatment.

| Source | Country | Study Design | Population | Subtype | Assessment | Treatment Duration, mo | Intervention (Patients Enrolled/Completed, No.) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Soriano et al,23 2002 | United States | SA, OL | All | ND | Total patches | 6 | Tacrolimus, 0.1%, twice daily (23/19) |

| Lepe et al,7 2003 | Mexico | WP, DB, RCT | Children | NSV | Total patches | 2 | Tacrolimus, 0.1%, twice daily; clobetasol, 0.05%, twice daily (20/20) |

| Tanghetti,24 2003 | United States | SA, OL | All | ND | Total patches | 9 | Tacrolimus, 0.1%, twice daily (15/15) |

| Grimes et al,8 2004 | United States | SA, OL | All | NSV | Individual patch, total patches | 6 | Tacrolimus, 0.1%, twice daily (23/19) |

| Kanwar et al,25 2004 | India | SA, OL | Children | NSV, SV | Total patches | 3 | Tacrolimus, 0.03%, twice daily (25/22) |

| Passeron et al,55 2004 | France | WP, RCT | All | NSV, SV | Total patches | 3 | Tacrolimus, 0.1%, twice daily + EL twice weekly; EL twice weekly (14/14) |

| Rodríguez and Cervantes,45 2004 | Mexico | SA, OL | All | ND | Individual patch | 4.5 | Pimecrolimus, 1%, twice daily (50/33) |

| Almeida et al,26 2005 | Spain | SA, OL | All | ND | Individual patch, total patches | 6 | Tacrolimus, 0.1%, twice daily (12/12) |

| Dawid et al,64 2006 | Austria | WP, DB, RCT | Adult | NSV | Total patches | 6 | Pimecrolimus, 1%, twice daily; placebo (20/14) |

| Şendur et al,27 2006 | Turkey | SA, OL | All | NSV, SV | Total patches | 6 | Pimecrolimus, 1%, once daily (23/19) |

| Fai et al,56 2007 | Italy | SA, OL | Adult | NSV | Individual patch, total patches | 4 | Tacrolimus, 0.03%, once daily (facial lesions) and tacrolimus, 0.1%, once daily (other areas) + NBUVB twice weekly (124/110) |

| Kanwar,28 2007 | India | SA, OL | ND | ND | Total patches | 4 | Pimecrolimus, 1%, twice daily (22/20) |

| Seirafi et al,29 2007 | Iran | SA, OL | All | NSV | Individual patch, total patches | 3 | Pimecrolimus, 1%, twice daily (30/30) |

| Hartmann et al,46 2008 | Germany | WP, OL | Adult | NSV | Total patches | 12 | Tacrolimus, 0.1%, twice daily, partial occlusion; emollient (31/21) |

| Lotti et al,30 2008 | Italy | PD, OL | Adult | NSV, SV | Total patches | 6 | Tacrolimus, 0.1%, twice daily (22/19); pimecrolimus, 1%, twice daily (19/18); betamethasone dipropionate, 0.05%, twice daily (23/20); calcipotriol, 50 μg/g, twice daily (18/17); L-phenylalanine, 10%, twice daily (18/17); tacrolimus, 0.1%, twice daily + NBUVB biweekly (59/58); pimecrolimus, 1%, twice daily + NBUVB biweekly (63/63); Betamethasone dipropionate, 0.05%, twice daily + NBUVB biweekly (28/26); Calcipotriol, 50 μg/g, twice daily + NBUVB biweekly (60/60); L-phenylalanin 10% twice daily + NBUVB biweekly (60/60); NBUVB biweekly (100/100) |

| Eryilmaz et al,31 2009 | Turkey | WP, DB, RCT | All | ND | Total patches | 2 | Pimecrolimus, 1%, twice daily; clobetasol propionate, 0.05%, twice daily (16/14) |

| Esfandiarpour et al,63 2009 | Iran | PD, DB, RCT | All | NSV | Individual patch, total patches | 3 | Pimecrolimus, 1%, twice daily + NBUVB thrice weekly; NBUVB thrice weekly (34/25) |

| Farajzadeh et al,32 2009 | Iran | WP, RCT | Children | ND | Total patches | 3 | Pimecrolimus, 1%, once daily with occlusion for 10 d (assessed after 3 mo); pimecrolimus, 1%, once daily with occlusion for 10 d + microdermabrasion (assessed after 3 mo); placebo (65/60) |

| Hui-Lan et al,57 2009 | China | WP, RCT | Children | NSV | Total patches | 4 | Pimecrolimus, 1%, twice daily + EL twice weekly; EL twice weekly (49/48) |

| Klahan and Asawanonda,58 2009 | Thailand | WP, RCT | Adult | ND | Total patches | 3 | Tacrolimus, 0.1%, twice daily + NBUVB twice weekly; NBUVB twice weekly (15/15) |

| Radakovic et al,33 2009 | Austria | WP, RCT | All | NSV | Total patches | 6 | Tacrolimus, 0.1%, once daily; tacrolimus, 0.1%, twice daily; untreated (17/15) |

| Stinco et al,47 2009 | Italy | PD, RCT | Adult | ND | Individual patch | 7 | Pimecrolimus, 1%, twice daily (16/13); tacrolimus, 0.1%, twice daily (15/12); NBUVB thrice weekly (13/13) |

| Xu et al,34 2009 | China | SA, OL | All | NSV, SV | Individual patch, total patches | 4 | Tacrolimus, 0.1%, twice daily (30/30) |

| Köse et al,35 2010 | Turkey | PD, OL | Children | NSV, SV | Total patches | 3 | Pimecrolimus, 1%, twice daily (25/20); mometasone, 0.1%, once daily (25/20) |

| Lo et al,48 2010 | Taiwan | SA, OL | All | NSV | Total patches | 3 | Tacrolimus, 0.1%, twice daily (61/37) |

| Lubaki et al,22 2010 | Belgium | WP, DB, RCT | All | NSV | Total patches | 7 | Tacrolimus, 0.1%, twice daily; vehicle (20/20) |

| Lubaki et al,22 2010 | Belgium | SA, OL | All | NSV | Total patches | 7 | Pimecrolimus, 1%, twice daily (20/20) |

| Majid,59 2010 | India | WP, OL | All | NSV | Total patches | 12 | Tacrolimus 0.1%, twice daily + NBUVB thrice weekly; NBUVB thrice weekly (80/74) |

| Paracha et al,49 2010 | Pakistan | PD, OL | All | ND | Total patches | 3 | Tacrolimus, 0.03%, twice daily (30/28); superoxide dismutase and catalase twice daily (30/30) |

| Suo et al,36 2010 | China | PD, RCT | All | ND | Individual patch, total patches | 4 | Tacrolimus, 0.1%, twice daily + NBUVB twice weekly (28/28); tacrolimus, 0.1%, twice daily (27/27); NBUVB twice weekly (27/27) |

| Ho et al,44 2011 | Canada | PD, DB, RCT | Children | NSV, SV | Individual patch | 6 | Tacrolimus, 0.1% (33/31); clobetasol propionate, 0.05% (33/30); placebo (34/29) |

| Juan et al,37 2011 | China | WP, OL | All | NSV, SV | Total patches | 3 | Tacrolimus, 0.1%, or 0.03% (age <12 y), twice daily; mometasone furoate once daily (36/31) |

| Tamler et al,50 2011 | Brazil | SA, OL | ND | ND | Individual patch | 4 | Tacrolimus, 0.1%, twice daily (12/10) |

| Udompataikul et al,38 2011 | Thailand | SA, OL | All | NSV, SV | Individual patch, total patches | 6 | Tacrolimus, 0.1%, twice daily (42/38) |

| Kathuria et al,39 2012 | India | PD, RCT | All | SV | Total patches | 6 | Tacrolimus, 0.1%, twice daily (29/26); fluticasone, 0.05%, once daily (31/26) |

| Du et al,40 2013 | China | SA, OL | ND | ND | Total patches | 3 | Tacrolimus, 0.1%, twice daily (46/34) |

| Farajzadeh et al,41 2013 | Iran | WP, OL | Children | ND | Total patches | 3 | Pimecrolimus, 1%, twice daily; mometasone furoate, 0.1%, once daily; pimecrolimus, 1%, twice daily + mometasone furoate, 0.1%, once daily (40/40) |

| Satyanarayan et al,60 2013 | India | WP, RCT | All | NSV | Individual patch, total patches | 6 | Tacrolimus, 0.1%, once daily + NBUVB thrice weekly; NBUVB thrice weekly (25/25) |

| Wu et al,51 2013 | China | WP, RCT | ND | ND | Total patches | 3 | Tacrolimus, 0.03%, twice daily; EL, 10 times a month (30/27) |

| Baldo et al,52 2014 | Italy | WP, RCT | All | ND | Individual patch | 9 | Tacrolimus, 0.1%, twice daily; NBUVB twice weekly (12/12) |

| Bilal et al,61 2014 | Pakistan | PD, DB, RCT | All | NSV, SV | Total patches | 3 | Tacrolimus, 0.1%, twice daily + NBUVB thrice weekly (30/30); placebo + NBUVB thrice weekly (30/30) |

| Dayal et al,62 2016 | India | WP, OL | Adult | ND | Total patches | 6 | Tacrolimus, 0.03%, twice daily + NBUVB thrice weekly; NBUVB thrice weekly (20/20) |

| Rafiq et al,42 2016 | Pakistan | PD, OL | All | ND | Total patches | 6 | Tacrolimus, 0.03%, twice daily (30/30); clobetasol, 0.05%, 3 wk in 1 mo (30/30) |

| Roy et al,43 2016 | Bangladesh | PD, OL | All | NSV, SV | Total patches | 4 | Tacrolimus, 0.1% (44/44); clobetasol, 0.05% (34/34); tacrolimus, 0.1%, + clobetasol, 0.05% (34/34) |

| Silpa-Archa et al,53 2016 | Thailand | WP, OL | Adult | ND | Individual patch | 6 | Tacrolimus, 0.1%, twice daily; mometasone furoate, 0.1%, twice daily (20/18) |

| Rokni et al,54 2017 | Iran | SA, OL | All | ND | Individual patch | 6 | Tacrolimus, 0.1%, twice daily (30/30) |

| Ullah et al,65 2017 | Pakistan | PD, RCT | All | ND | Total patches | 6 | Tacrolimus, 0.1%, twice daily + NBUVB thrice weekly (47/47); NBUVB thrice weekly (47/47) |

| Maintenance Therapy | |||||||

| Cavalié et al,66 2015 | France | PD, DB, RCT | Adult | NSV | Total patches | 6 | Tacrolimus, 0.1%, twice weekly for maintenance (19/15); placebo twice weekly (16/15) |

Abbreviations: DB, double-blind; EL, excimer laser; ND, not determined; NBUVB, narrow-band UV-B phototherapy; NSV, nonsegmental vitiligo; OL, open label; PD, parallel design; RCT, randomized clinical trial; SA, single arm; SV, segmental vitiligo; TCI, topical calcineurin inhibitor; TNF, tumor necrosis factor; WP, within-patient.

Figure 2. Treatment Response to Topical Calcineurin Inhibitors (TCIs) in Patients With Vitiligo.

A, Treatment response to TCI monotherapy. B, Treatment response to TCI plus phototherapy.

Table 3. Treatment Response Rates to TCIs for Vitiligo.

| Condition | Treatment Response Rate, % (95% CI) | Included Studies | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ≥75% Repigmentation | ≥50% Repigmentation | ≥25% Repigmentation | ||

| TCI Monotherapy | ||||

| Total | 18.1 (13.2-23.1) | 38.5 (28.2-48.8) | 55.0 (42.2-67.8) | 653 Patients in 25 studies (7, 8, 22-43, 64) |

| Children | 31.7 (6.7-56.8) | 47.3 (19.0-75.7) | 66.4 (43.2-89.7) | 177 Patients in 6 studies (7, 28, 32, 35, 41, 44) |

| Face and neck | 35.4 (24.9-46.0) | 57.5 (44.4-70.7) | 73.1 (32.6-83.5) | 392 Patients in 18 studies (8, 22, 26, 29, 34, 36, 38, 44-54) |

| Trunk and extremities | 2.3 (0.3-4.3) | 10.6 (5.3-15.8) | 34.2 (13.9-54.6) | 174 Patients in 9 studies (8, 26, 29, 38, 44, 47, 52-54) |

| Hands and feet | 0.00 (NA) | 1.71 (0.00-4.6) | 15.1 (6.7-23.4) | 52 Patients in 4 studies (26, 29, 47, 52) |

| TCI Plus Phototherapy | ||||

| Total | 47.5 (30.6-64.4) | 72.9 (57.6-88.2) | 89.5 (81.1-97.9) | 533 Patients in 11 studies (30, 36, 55-62, 65) |

| Face and neck | 55.2 (24.6-85.9) | 81.5 (10.3-92.7) | 93.7 (87.6-99.8) | 129 Patients in 5 studies (36, 56, 60, 62, 63) |

| Trunk and extremities | 16.1 (10.2-22.0) | 44.9 (30.3-59.5) | 85.3 (79.8-90.7) | 161 Patients in 3 studies (56, 62, 63) |

Abbreviations: NA, not available; TCI, topical calcineurin inhibitor.

Lesions on the face and neck showed an at least mild response in 73.1% (95% CI, 32.6%-83.5%) of 312 patients in 14 studies,8,29,34,38,45,46,47,48,49,50,52,53,54,64 and a marked response 35.4% (95% CI, 24.9%-7 46.0%) of 353 patients in 16 studies.8,22,26,29,34,38,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54 Lesions on the trunk and extremities showed an at least mild response in 34.2% (95% CI, 13.9%-54.6% of 153 patients in 7 studies,8,29,38,47,52,53,54 and a marked response in 2.3% (95% 10 CI, 0.3%-4.3%) of 185 patients in 8 studies.8,29,38,47,52,53,54 Lesions on the hands and feet showed an at least mild response in 15.1% (95% CI, 6.7%-23.4%) in 48 patients in 3 studies,29,47,52 and no marked response was observed among 52 patients in 4 studies.26,29,47,52

Treatment Response to TCI Plus Phototherapy

Of the 12 studies in the TCI plus phototherapy group, 10 combined TCI treatment with NBVUB30,36,56,58,59,60,61,62,63,65 and 2 combined TCI treatment with EL.55,57 An at least mild response to TCI plus phototherapy was achieved in in 89.5% (95% CI, 81.1%-97.9%) of 433 patients in 8 studies,30,55,56,57,59,60,61,62 an at least moderate response was achieved in 72.9% (95% CI, 57.6%-88.2%) of 486 patients in 10 studies,30,36,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62 and a marked response was achieved in 47.5% (95% CI, 30.6%-64.4%) of 490 patients in 9 studies.30,55,56,57,59,60,61,62,65

In TCI plus phototherapy treatment of face and neck lesions, an at least mild response was achieved 93.7% (95% CI, 87.6%-99.8%) of 103 patients in 4 studies,56,60,62,63 and a marked response was achieved in 55.2% (95% CI, 24.6%-85.9%) of 103 patients in 4 studies.56,60,62,63 In lesions on the trunk and extremities, 85.3% (95% CI, 79.8%-90.7%) of 161 patients in 3 studies achieved an at least mild response,56,62,63 and 16.1% (95% CI, 10.2%-22.0%) of 161 patients in 3 studies achieved a marked response.56,62,63 We did not perform subgroup analyses for hand and foot lesions because only 2 studies met the criteria and the response rate was minimal.

TCI Maintenance Therapy

We identified 1 study that investigated the use of TCIs for maintenance therapy (Table 2). Cavalié et al66 performed a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study to evaluate the efficacy of TCI maintenance therapy with patients achieving 75% or more repigmentation from any treatment modality. Patients were randomized to twice-weekly application of tacrolimus, 0.1%, ointment (n = 19) or placebo (n = 16). Some degree of depigmentation was observed in 9.7% of patients in the tacrolimus group and 40.0% of those in the placebo group after 24 weeks.

Safety of TCI

Of the 36 clinical studies of TCI monotherapy included in this analysis, 25 referred to adverse events and 12 reported the number of occurrences of each adverse event.7,8,22,25,26,27,29,34,35,39,46,48 We pooled the total occurrences of common adverse events seen in TCI monotherapy. In 296 patients, the most common were a burning sensation (29 [9.8%]), pruritus (22 [7.4%]), and erythema (7 [2.4%]).7,8,22,25,26,27,29,34,35,39,46,48 All of the events were transient and did not require additional treatment. Other adverse events, including verruca, dysesthesia, and contact dermatitis, were rarely reported, and no studies reported adverse effects leading to discontinuation of treatment.

Discussion

We systematically reviewed the mechanism of action (11 studies); treatment responses of monotherapy (36 studies), combination therapy with phototherapy (12 studies), and maintenance therapy (1 study); and the safety profiles (12 studies) of TCI for vitiligo in the literature. We also conducted meta-analyses where possible.

Topical calcineurin inhibitors possess a dual mechanism of action for the treatment of vitiligo: immunosuppression and melanocyte induction. First, TCIs inhibit cytotoxic CD8+ T cells, an effector arm of autoimmunity in vitiligo, by inhibiting calcineurin-mediated phosphorylation of the nuclear factor of activated T cells.67 In in vivo studies, TCI treatment led to a decrease in tumor necrosis factor and an increase in IL-10 in vitiligo lesions.8,13 Second, TCIs induce the repigmentation of vitiligo by stimulating melanocyte proliferation and migration14,15,17,18,19 and melanin synthesis.14,15,19,20 This process involves increasing MMP-2 and MMP-9 activity,17 increasing endothelin B receptor expression in melanoblasts,16 and promoting the secretion of stem cell factor from keratinocytes following TCI treatment.14 In addition, reduced oxidative stress and increased antioxidant capacity have also been observed in the serum samples of patients treated with topical tacrolimus.22

We identified a positive treatment response of TCI monotherapy for vitiligo. We found that TCI monotherapy achieved a favorable treatment response rate, with 55.0% of patients achieving an at least mild response (≥25% repigmentation) after a median treatment duration of 3 months. Topical calcineurin inhibitor monotherapy was particularly effective in pediatric patients: 66.4% of children achieved an at least mild response and 31.7% achieved a marked response (≥75% repigmentation). Among the body parts, face and neck showed the best response, and an at least mild response was achieved in 73.1% of patients, whereas such a response was not found for other body parts. Some hypotheses can help to explain these results. Since hair follicles, which serve as reservoirs of melanocytes, are built in the early fetal period and move apart according to the growth of the skin after birth,68 children have a higher hair follicle density than adults and so do the face and neck.69 In addition, daily exposure to sunlight for the head and neck is likely to be associated with better outcomes.

The treatment responses of TCIs combined with phototherapy (an at least mild response achieved in 89.5% of patients) were higher than those of TCI monotherapy. The results were also better than treatment responses to phototherapy alone (an at least mild response achieved in 62.1% of subjects after 3 months of NBUVB phototherapy) published in a previous systematic review,70 which supports the synergistic effects of this combination therapy. The difference in treatment response of TCI monotherapy and TCI combined with phototherapy was particularly evident in sun-protected areas of the body (ie, the trunk and extremities). Our findings are consistent with recent reports on Janus kinase inhibitors showing the improved treatment response with the concomitant use of NBUVB,71,72 and reaffirm the synergistic role of phototherapy and TCI treatment.73 The treatment of vitiligo may require melanocyte induction via UV exposure as well as suppression of the autoimmune response.71 Tacrolimus-induced endothelin B receptor expression in melanoblasts and UV-B–induced endothelin secretion from keratinocytes can serve as a theoretical basis for this synergism.16

One possible issue in the concurrent use of TCI with phototherapy is that the potential photocarcinogenicity of UV light could be enhanced by the immunosuppressive effects of TCIs. However, in rodent studies, TCIs did not accelerate photocarcinogenesis in combination with phototherapy.74 Rather, TCIs have been shown to prevent DNA photodamage by UV light75 and even to inhibit skin tumor induction in a mouse model.76 In addition, although there is a long history of the use of TCIs accompanied by phototherapy for the treatment of vitiligo, to our knowledge, no clinical evidence has been reported for increased carcinogenicity of this combination of therapies in humans. Guidelines thus advocate the use of TCIs in combination with phototherapy for patients with vitiligo to enhance the treatment response.3,4 An additional benefit of combination therapy is that it could shorten the total duration of phototherapy with the enhanced treatment response. Further studies are needed to clarify this issue.

One study demonstrated that maintenance therapy using TCIs prevented the recurrence of vitiligo after successful repigmentation.66 Proactive treatment with TCIs has been recommended for the management of atopic dermatitis for preventing new flare-ups.77 Likewise, TCIs seem to be effective for preventing appearance of new depigmented patches in patients with vitiligo.

Limitations

Our systematic review has limitations. First, there was considerable heterogeneity in study designs, characteristics of the patients, and protocols. However, we assumed that prospective studies with identical protocols would have minimal biases regarding the efficacy of TCIs. Second, the quartile scale may be somewhat arbitrary. However, it has been the most commonly used measure and would have been one of the best estimates of the treatment response at this time.

Conclusions

Topical calcineurin inhibitors are believed to be beneficial in the treatment of vitiligo not only by inhibiting autoimmunity associated with the disease but also by promoting melanocyte induction. Topical calcineurin inhibitor monotherapy appears to produce a favorable therapeutic response, especially in children and in lesions on the face and neck. Therefore, TCI monotherapy is worth attempting for the treatment of face and neck lesions, particularly in children, when phototherapy is not available. Moreover, as phototherapy and TCI treatment have synergistic effects, TCI treatment should also be encouraged in patients with vitiligo who are undergoing phototherapy. In addition, the proactive use of TCIs to maintain remission of vitiligo could be promising, considering its high recurrence rate.

eTable 1. Predetermined Search Terms in Each Database

eTable 2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria Used in This Study

eFigure. Forest Plots of Treatment Response of Topical Calcineurin Inhibitors (TCIs) for Vitiligo

References

- 1.Alikhan A, Felsten LM, Daly M, Petronic-Rosic V. Vitiligo: a comprehensive overview—part I: introduction, epidemiology, quality of life, diagnosis, differential diagnosis, associations, histopathology, etiology, and work-up. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65(3):473-491. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2010.11.061 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bae JM, Lee SC, Kim TH, et al. Factors affecting quality of life in patients with vitiligo: a nationwide study. Br J Dermatol. 2018;178(1):238-244. doi: 10.1111/bjd.15560 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Taieb A, Alomar A, Böhm M, et al. ; Vitiligo European Task Force (VETF); European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology (EADV); Union Europénne des Médecins Spe´cialistes (UEMS) . Guidelines for the management of vitiligo: the European Dermatology Forum consensus. Br J Dermatol. 2013;168(1):5-19. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2012.11197.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Oiso N, Suzuki T, Wataya-Kaneda M, et al. Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of vitiligo in Japan. J Dermatol. 2013;40(5):344-354. doi: 10.1111/1346-8138.12099 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bae JM, Hong BY, Lee JH, Lee JH, Kim GM. The efficacy of 308-nm excimer laser/light (EL) and topical agent combination therapy versus EL monotherapy for vitiligo: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials (RCTs). J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74(5):907-915. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2015.11.044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nordal EJ, Guleng GE, Rönnevig JR. Treatment of vitiligo with narrowband-UVB (TL01) combined with tacrolimus ointment (0.1%) vs placebo ointment, a randomized right/left double-blind comparative study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2011;25(12):1440-1443. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2011.04002.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lepe V, Moncada B, Castanedo-Cazares JP, Torres-Alvarez MB, Ortiz CA, Torres-Rubalcava AB. A double-blind randomized trial of 0.1% tacrolimus vs 0.05% clobetasol for the treatment of childhood vitiligo. Arch Dermatol. 2003;139(5):581-585. doi: 10.1001/archderm.139.5.581 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Grimes PE, Morris R, Avaniss-Aghajani E, Soriano T, Meraz M, Metzger A. Topical tacrolimus therapy for vitiligo: therapeutic responses and skin messenger RNA expression of proinflammatory cytokines. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;51(1):52-61. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2003.12.031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Moher D, Shamseer L, Clarke M, et al. ; PRISMA-P Group . Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Syst Rev. 2015;4:1. doi: 10.1186/2046-4053-4-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials. 1986;7(3):177-188. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(86)90046-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ. 2003;327(7414):557-560. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hunter JP, Saratzis A, Sutton AJ, Boucher RH, Sayers RD, Bown MJ. In meta-analyses of proportion studies, funnel plots were found to be an inaccurate method of assessing publication bias. J Clin Epidemiol. 2014;67(8):897-903. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2014.03.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Taher ZA, Lauzon G, Maguiness S, Dytoc MT. Analysis of interleukin-10 levels in lesions of vitiligo following treatment with topical tacrolimus. Br J Dermatol. 2009;161(3):654-659. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2009.09217.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lan CCE, Chen GS, Chiou MH, Wu CS, Chang CH, Yu HS. FK506 promotes melanocyte and melanoblast growth and creates a favourable milieu for cell migration via keratinocytes: possible mechanisms of how tacrolimus ointment induces repigmentation in patients with vitiligo. Br J Dermatol. 2005;153(3):498-505. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2005.06739.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kang HY, Choi YM. FK506 increases pigmentation and migration of human melanocytes. Br J Dermatol. 2006;155(5):1037-1040. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2006.07467.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lan CC, Wu CS, Chen GS, Yu HS. FK506 (tacrolimus) and endothelin combined treatment induces mobility of melanoblasts: new insights into follicular vitiligo repigmentation induced by topical tacrolimus on sun-exposed skin. Br J Dermatol. 2011;164(3):490-496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lee KY, Jeon SY, Hong JW, et al. Endothelin-1 enhances the proliferation of normal human melanocytes in a paradoxical manner from the TNF-α–inhibited condition, but tacrolimus promotes exclusively the cellular migration without proliferation: a proposed action mechanism for combination therapy of phototherapy and topical tacrolimus in vitiligo treatment. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2013;27(5):609-616. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2012.04498.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jung H, Oh ES. FK506 positively regulates the migratory potential of melanocyte-derived cells by enhancing syndecan-2 expression. Pigment Cell Melanoma Res. 2016;29(4):434-443. doi: 10.1111/pcmr.12480 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Xu P, Chen J, Tan C, Lai RS, Min ZS. Pimecrolimus increases the melanogenesis and migration of melanocytes in vitro. Korean J Physiol Pharmacol. 2017;21(3):287-292. doi: 10.4196/kjpp.2017.21.3.287 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Park OJ, Park GH, Choi JR, et al. A combination of excimer laser treatment and topical tacrolimus is more effective in treating vitiligo than either therapy alone for the initial 6 months, but not thereafter. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2016;41(3):236-241. doi: 10.1111/ced.12742 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jung H, Chung H, Chang SE, Kang DH, Oh ES. FK506 regulates pigmentation by maturing the melanosome and facilitating their transfer to keratinocytes. Pigment Cell Melanoma Res. 2016;29(2):199-209. doi: 10.1111/pcmr.12443 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lubaki LJ, Ghanem G, Vereecken P, et al. Time-kinetic study of repigmentation in vitiligo patients by tacrolimus or pimecrolimus. Arch Dermatol Res. 2010;302(2):131-137. doi: 10.1007/s00403-009-0973-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Soriano T, Grimes PE, Meraz M, Morris R. The efficacy and safety of topical tacrolimus in patients with vitiligo [abstract]. J Invest Dermatol. 2002;119(1):344. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tanghetti EA. Tacrolimus ointment 0.1% produces repigmentation in patients with vitiligo: results of a prospective patient series. Cutis. 2003;71(2):158-162. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kanwar AJ, Dogra S, Parsad D. Topical tacrolimus for treatment of childhood vitiligo in Asians. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2004;29(6):589-592. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2230.2004.01632.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Almeida P, Borrego L, Rodríguez-López J, Luján D, Cameselle D, Hernández B. Vitiligo: treatment of 12 cases with topical tacrolimus [Spanish]. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2005;96(3):159-163. doi: 10.1016/S0001-7310(05)73058-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Şendur N, Karaman G, Saniç N, Şavk E. Topical pimecrolimus: a new horizon for vitiligo treatment? J Dermatolog Treat. 2006;17(6):338-342. doi: 10.1080/09546630601028711 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kanwar AJ. Topical pimecrolimus in vitiligo—a preliminary study [abstract]. Br J Dermatol. 2007;157:65. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Seirafi H, Farnaghi F, Firooz A, Vasheghani-Farahani A, Alirezaie NS, Dowlati Y. Pimecrolimus cream in repigmentation of vitiligo. Dermatology. 2007;214(3):253-259. doi: 10.1159/000099592 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lotti T, Buggiani G, Troiano M, et al. Targeted and combination treatments for vitiligo. Comparative evaluation of different current modalities in 458 subjects. Dermatol Ther. 2008;21(suppl 1):S20-S26. doi: 10.1111/j.1529-8019.2008.00198.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Eryilmaz A, Seçkin D, Baba M. Pimecrolimus: a new choice in the treatment of vitiligo? J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2009;23(11):1347-1348. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2009.03228.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Farajzadeh S, Daraei Z, Esfandiarpour I, Hosseini SH. The efficacy of pimecrolimus 1% cream combined with microdermabrasion in the treatment of nonsegmental childhood vitiligo: a randomized placebo-controlled study. Pediatr Dermatol. 2009;26(3):286-291. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1470.2009.00926.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Radakovic S, Breier-Maly J, Konschitzky R, et al. Response of vitiligo to once- vs. twice-daily topical tacrolimus: a controlled prospective, randomized, observer-blinded trial. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2009;23(8):951-953. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2009.03138.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Xu AE, Zhang DM, Wei XD, Huang B, Lu LJ. Efficacy and safety of tarcrolimus cream 0.1% in the treatment of vitiligo. Int J Dermatol. 2009;48(1):86-90. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2009.03852.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Köse O, Arca E, Kurumlu Z. Mometasone cream versus pimecrolimus cream for the treatment of childhood localized vitiligo. J Dermatolog Treat. 2010;21(3):133-139. doi: 10.3109/09546630903266761 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Suo DF, Zhang JL, Yan CY. Combination of topical tacrolimus ointment and NB-UVB for vitiligo on the face and neck. J Clin Dermatol. 2010;39(2):127-129. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Juan D, Qianxi X, Zhou C, Jianzhong Z. Clinical efficacy and safety of tacrolimus ointment in patients with vitiligo. J Dermatol. 2011;38(11):1092-1094. doi: 10.1111/j.1346-8138.2010.01124.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Udompataikul M, Boonsupthip P, Siriwattanagate R. Effectiveness of 0.1% topical tacrolimus in adult and children patients with vitiligo. J Dermatol. 2011;38(6):536-540. doi: 10.1111/j.1346-8138.2010.01067.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kathuria S, Khaitan BK, Ramam M, Sharma VK. Segmental vitiligo: a randomized controlled trial to evaluate efficacy and safety of 0.1% tacrolimus ointment vs 0.05% fluticasone propionate cream. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2012;78(1):68-73. doi: 10.4103/0378-6323.90949 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Du J, Wang XY, Ding XL, et al. Long-term efficacy and safety of tacrolimus ointment in the treatment of vitiligo. J Dermatol. 2013;40(11):935-936. doi: 10.1111/1346-8138.12283 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Farajzadeh S, Esfandyarpoor I, Poor Khandani E, Ekhlasi A, Safari S, Hasheminasab Gorji S. Efficacy of combination therapy of pimecrolimus 1% cream and mometasone cream with either agent alone in the treatment of childhood vitiligo. J Mazand Univ Med Sci. 2013;23(97):238-248. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rafiq Z, Khurshid K, Pal SS. Comparison of topical 0.03% tacrolimus with 0.05% clobetasol in treatment of vitiligo. J Pak Assoc Dermatol. 2016;26(2):123-128. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Roy P, Saha SK, Paul PC, et al. Effectiveness of topical corticosteroid, topical calcineurin inhibitors and combination of them in the treatment of vitiligo. Mymensingh Med J. 2016;25(4):620-627. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ho N, Pope E, Weinstein M, Greenberg S, Webster C, Krafchik BR. A double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial of topical tacrolimus 0.1% vs. clobetasol propionate 0.05% in childhood vitiligo. Br J Dermatol. 2011;165(3):626-632. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2011.10351.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rodríguez AM, Cervantes AMA. Vitiligo affecting face: treatment with pimecrolimus cream 1%: pilot study. Dermatol Rev Mex. 2004;48(2):71-76. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hartmann A, Bröcker EB, Hamm H. Occlusive treatment enhances efficacy of tacrolimus 0.1% ointment in adult patients with vitiligo: results of a placebo-controlled 12-month prospective study. Acta Derm Venereol. 2008;88(5):474-479. doi: 10.2340/00015555-0464 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Stinco G, Piccirillo F, Forcione M, Valent F, Patrone P. An open randomized study to compare narrow band UVB, topical pimecrolimus and topical tacrolimus in the treatment of vitiligo. Eur J Dermatol. 2009;19(6):588-593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lo YH, Cheng GS, Huang CC, Chang WY, Wu CS. Efficacy and safety of topical tacrolimus for the treatment of face and neck vitiligo. J Dermatol. 2010;37(2):125-129. doi: 10.1111/j.1346-8138.2009.00774.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Paracha M, Khurshid K, Pal S, Ali Z. Comparison of treatment with tacrolimus 0.03% and superoxide dismutase and catalase in vitiligo. J Postgrad Med Inst. 2010;24(2):115-121. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tamler C, Duque-Estrada B, Oliveira PA, Avelleira JC. Tacrolimus 0,1% ointment in the treatment of vitiligo: a series of cases. An Bras Dermatol. 2011;86(1):169-172. doi: 10.1590/S0365-05962011000100034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wu Y, Qiu L, Chen HD, Gao XH. A comparative study on efficacy of 308nm-excimer laser vs. tacrolimus in the treatment of progressive vitiligo on face or neck [abstract]. Lasers Med Sci. 2013;28(6):1430.23307439 [Google Scholar]

- 52.Baldo A, Lodi G, Di Caterino P, Monfrecola G. Vitiligo, NB-UVB and tacrolimus: our experience in Naples. G Ital Dermatol Venereol. 2014;149(1):123-130. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Silpa-Archa N, Nitayavardhana S, Thanomkitti K, Chularojanamontri L, Varothai S, Wongpraparut C. Comparison of the efficacy and safety of 0.1% tacrolimus ointment and 0.1% mometasone furoate cream for adult vitiligo: a single-blinded pilot study. Dermatologica Sinica. 2016;34(4):177-179. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Rokni GR, Golpour M, Gorji AH, Khalilian A, Ghasemi H. Effectiveness and safety of topical tacrolimus in treatment of vitiligo. J Adv Pharm Technol Res. 2017;8(1):29-33. doi: 10.4103/2231-4040.197388 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Passeron T, Ostovari N, Zakaria W, et al. Topical tacrolimus and the 308-nm excimer laser: a synergistic combination for the treatment of vitiligo. Arch Dermatol. 2004;140(9):1065-1069. doi: 10.1001/archderm.140.9.1065 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Fai D, Cassano N, Vena GA. Narrow-band UVB phototherapy combined with tacrolimus ointment in vitiligo: a review of 110 patients. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2007;21(7):916-920. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2006.02101.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hui-Lan Y, Xiao-Yan H, Jian-Yong F, Zong-Rong L. Combination of 308-nm excimer laser with topical pimecrolimus for the treatment of childhood vitiligo. Pediatr Dermatol. 2009;26(3):354-356. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1470.2009.00914.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Klahan S, Asawanonda P. Topical tacrolimus may enhance repigmentation with targeted narrowband ultraviolet B to treat vitiligo: a randomized, controlled study. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2009;34(8):e1029-e1030. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2230.2009.03712.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Majid I. Does topical tacrolimus ointment enhance the efficacy of narrowband ultraviolet B therapy in vitiligo? a left-right comparison study. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. 2010;26(5):230-234. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0781.2010.00540.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Satyanarayan HS, Kanwar AJ, Parsad D, Vinay K. Efficacy and tolerability of combined treatment with NB-UVB and topical tacrolimus versus NB-UVB alone in patients with vitiligo vulgaris: a randomized intra-individual open comparative trial. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2013;79(4):525-527. doi: 10.4103/0378-6323.113091 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Bilal A, Shiakh ZI, Khan S, Iftikhar N, Anwar I, Sadiq S. Efficacy of 0.1% topical tacrolimus with narrow band ultraviolet B phototherapy versus narrow band ultraviolet B phototherapy in vitiligo. J Pak Assoc Dermatol. 2014;24(4):327-331. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Dayal S, Sahu P, Gupta N. Treatment of childhood vitiligo using tacrolimus ointment with narrowband ultraviolet B phototherapy. Pediatr Dermatol. 2016;33(6):646-651. doi: 10.1111/pde.12991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Esfandiarpour I, Ekhlasi A, Farajzadeh S, Shamsadini S. The efficacy of pimecrolimus 1% cream plus narrow-band ultraviolet B in the treatment of vitiligo: a double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial. J Dermatolog Treat. 2009;20(1):14-18. doi: 10.1080/09546630802155057 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Dawid M, Veensalu M, Grassberger M, Wolff K. Efficacy and safety of pimecrolimus cream 1% in adult patients with vitiligo: results of a randomized, double-blind, vehicle-controlled study. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2006;4(11):942-946. doi: 10.1111/j.1610-0387.2006.06124.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ullah G, Rehman S, Noor SM, Paracha MM. Efficacy of tacrolimus plus narrowband ultraviolet B phototherapy versus narrowband ultraviolet B phototherapy alone in the treatment of vitiligo. J Pak Assoc Dermatol. 2017;27(3):232-237. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Cavalié M, Ezzedine K, Fontas E, et al. Maintenance therapy of adult vitiligo with 0.1% tacrolimus ointment: a randomized, double blind, placebo-controlled study. J Invest Dermatol. 2015;135(4):970-974. doi: 10.1038/jid.2014.527 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Al-Daraji WI, Grant KR, Ryan K, Saxton A, Reynolds NJ. Localization of calcineurin/NFAT in human skin and psoriasis and inhibition of calcineurin/NFAT activation in human keratinocytes by cyclosporin A. J Invest Dermatol. 2002;118(5):779-788. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.2002.01709.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Otberg N, Richter H, Schaefer H, Blume-Peytavi U, Sterry W, Lademann J. Variations of hair follicle size and distribution in different body sites. J Invest Dermatol. 2004;122(1):14-19. doi: 10.1046/j.0022-202X.2003.22110.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Esmat SM, El-Tawdy AM, Hafez GA, et al. Acral lesions of vitiligo: why are they resistant to photochemotherapy? J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2012;26(9):1097-1104. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2011.04215.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Bae JM, Jung HM, Hong BY, et al. Phototherapy for vitiligo: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153(7):666-674. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2017.0002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Liu LY, Strassner JP, Refat MA, Harris JE, King BA. Repigmentation in vitiligo using the Janus kinase inhibitor tofacitinib may require concomitant light exposure. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;77(4):675-682. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2017.05.043 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Joshipura D, Alomran A, Zancanaro P, Rosmarin D. Treatment of vitiligo with the topical Janus kinase inhibitor ruxolitinib: a 32-week open-label extension study with optional narrow-band ultraviolet B. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78(6):1205-1207. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2018.02.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Ostovari N, Passeron T, Lacour JP, Ortonne JP. Lack of efficacy of tacrolimus in the treatment of vitiligo in the absence of UV-B exposure. Arch Dermatol. 2006;142(2):252-253. doi: 10.1001/archderm.142.2.252 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Lerche CM, Philipsen PA, Poulsen T, Wulf HC. Topical tacrolimus in combination with simulated solar radiation does not enhance photocarcinogenesis in hairless mice. Exp Dermatol. 2008;17(1):57-62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Tran C, Lübbe J, Sorg O, et al. Topical calcineurin inhibitors decrease the production of UVB-induced thymine dimers from hairless mouse epidermis. Dermatology. 2005;211(4):341-347. doi: 10.1159/000088505 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Mitamura T, Doi Y, Kawabe M, et al. Inhibitory potency of tacrolimus ointment on skin tumor induction in a mouse model of an initiation-promotion skin tumor. J Dermatol. 2011;38(6):562-570. doi: 10.1111/j.1346-8138.2010.01046.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Schmitt J, von Kobyletzki L, Svensson A, Apfelbacher C. Efficacy and tolerability of proactive treatment with topical corticosteroids and calcineurin inhibitors for atopic eczema: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Br J Dermatol. 2011;164(2):415-428. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2010.10030.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eTable 1. Predetermined Search Terms in Each Database

eTable 2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria Used in This Study

eFigure. Forest Plots of Treatment Response of Topical Calcineurin Inhibitors (TCIs) for Vitiligo