Abstract

This study evaluates whether a 2012 change in the South Carolina Medicaid policy to reimburse hospitals for provision of immediate postpartum long-acting reversible contraception (IPP-LARC) separately from global payment for all services in a delivery hospitalization was associated with changes in IPP-LARC use and short-interval births between 2010 and 2017.

Short interpregnancy intervals (defined variously as 6, 12, 18, or 24 months between pregnancies) are associated with adverse newborn outcomes.1 Immediate postpartum long-acting reversible contraception (IPP-LARC)—ie, receipt of an intrauterine device or contraceptive implant before hospital discharge following a birth—is recommended to reduce short interpregnancy intervals, but IPP-LARC use remains limited in the United States.2,3 Payers’ common practice of providing one global payment for all services during a delivery hospitalization may disincentivize IPP-LARC provision. In March 2012, South Carolina’s Medicaid program (covering 60% of the state’s births) began reimbursing hospitals for IPP-LARC separately from the global payment.4 We evaluated whether this change was associated with changes in IPP-LARC use and short-interval births.

Methods

We used inpatient Medicaid claims data for all childbirth hospitalizations for women and adolescent girls aged 12 to 50 years between January 2010 and December 2017 in South Carolina. We identified IPP-LARC placement by an insertion and/or device code for a LARC device during hospitalization. We defined short-interval births as subsequent childbirths within 21 months (12-month interpregnancy interval plus 9-month gestation); only births through March 2016 were included to allow 21 months of observation for subsequent births.

We graphed trends in use of IPP-LARC and short-interval births before vs after the reimbursement policy change. An interrupted time series linear regression model included a linear time trend, a postpolicy indicator, and an interaction term to test the change in trend in outcomes after the policy change. Analyses adjusted for seasonality and autocorrelation and were stratified by age group (adolescents [<20 years] and adults [20-50 years]). Data were analyzed using Stata version 15 (Stata Corp). A 2-sided P < .05 defined statistical significance. The study was deemed exempt by the Harvard T. H. Chan School of Public Health Institutional Review Board.

Results

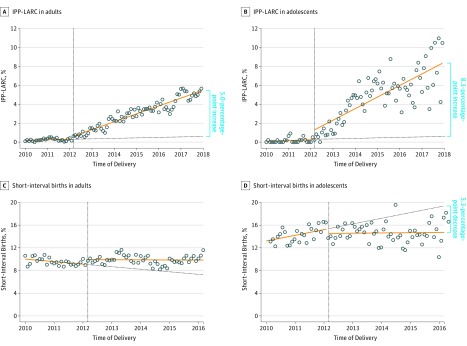

There were 242 825 childbirth hospitalizations, 5795 IPP-LARCs, and 21 372 short-interval births during the study. In January 2010, 0.07% of women received an IPP-LARC (Figure). Following the policy change, the trend in IPP-LARC increased relative to the prepolicy trend (difference in trends before vs after policy change, 0.07 [95% CI, 0.05-0.08; P < .001] percentage points each month among adults and 0.10 [95% CI, 0.07-0.13; P < .001] percentage points each month among adolescents) (Table). In December 2017, 5.65% of adults and 10.48% of adolescents received an IPP-LARC, which corresponds to increases of 5.00 (95% CI, 3.85-6.14; P < .001) percentage points in adults and 8.32 (95% CI, 6.45-10.18; P < .001) percentage points in adolescents relative to that expected without the policy change (Figure).

Figure. Trends in IPP-LARC and Short-Interval Births.

This figure shows the percentage of women whose childbirth was paid for by Medicaid in a given month who received immediate postpartum long-acting reversible contraception (IPP-LARC) (panels A and B) and who had a short-interval birth (panels C and D). Short-interval birth is an indicator equal to 1 if there was less than a 21-month interval between delivery and subsequent birth. Each plot shows a trend line based on predicted values from 2 linear regression models (one line before the start of the Medicaid policy, from January 2010 through February 2012, and a second line starting the month after the policy change, from March 2012 through the end of the study period). The study period was January 2010 to December 2017 for IPP-LARC and from January 2010 to March 2016 for short-interval births. Vertical dotted lines at March 2012 represent the start of Medicaid’s IPP-LARC reimbursement policy change. Horizontal dotted lines represent a counterfactual postpolicy trend line that extends the linear prepolicy trend through the end of the study period. Percentage-point changes represent differences between the observed trend and the counterfactual trend during the last month of the study period. The percentage-point change in short-interval births is omitted for adults because no statistically significant change in trend in short-interval births was found for adults in regression analysis.

Table. Changes in IPP-LARC and Short-Interval Births After South Carolina Medicaid’s Reimbursement Policy Change.

| Baseline %a | Monthly Trend Before Policy, % (95% CI)b | P Value | Monthly Trend After Policy, % (95% CI)b | P Value | Difference in Trends, % (95% CI)b | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IPP-LARC | |||||||

| Adults | 0.09 | 0.00 (−0.01 to 0.02) | .65 | 0.07 (0.06 to 0.07) | <.001 | 0.07 (0.05 to 0.08) | <.001 |

| Adolescents | 0.00 | −0.00 (−0.02 to 0.02) | .94 | 0.10 (0.08 to 0.12) | <.001 | 0.10 (0.07 to 0.13) | <.001 |

| Short-Interval Births (<21 mo Apart) | |||||||

| Adults | 10.61 | −0.03 (−0.07 to 0.01) | .09 | −0.00 (−0.02 to 0.01) | .89 | 0.03 (−0.01 to 0.07) | .14 |

| Adolescents | 13.10 | 0.09 (0.05 to 0.14) | <.001 | 0.01 (−0.03 to 0.04) | .78 | −0.09 (−0.14 to −0.03) | .002 |

Abbreviation: IPP-LARC, immediate postpartum long-acting reversible contraception.

The baseline mean represents the mean from January 2010.

Trends in IPP-LARC and short-interval births were calculated from interrupted time series regression models assessing the change in trend before (January 2010 to February 2012) and after (March 2012 to the end of the policy period) the Medicaid policy change, adjusting for quarter. The postpolicy trend statistics were calculated using Stata’s “lincom” command, used to create linear combinations of the interaction term and the prepolicy trend regression coefficients. Newey-West standard errors were used to adjust for autocorrelation. The study period was from January 2010 to December 2017 for IPP-LARC and from January 2010 to March 2016 for short-interval births.

In January 2010, 10.61% of births by adults and 13.10% of births by adolescents were followed by a short-interval birth (Figure). Adolescent short-interval births were increasing before the policy change and flattened afterward (difference in trends, −0.09 [95% CI, −0.14 to −0.03; P = .002] percentage points each month) (Table). In March 2016, 16.60% of adolescent births were followed by a short-interval birth, corresponding to a decrease of 5.28 (95% CI, −8.34 to −2.22; P = .001) percentage points relative to that expected without the policy change (Figure). In March 2016, 11.59% of births by adults were followed by a short-interval birth; there was no statistically significant change in trend in short-interval births for adults following the policy change (Table).

Discussion

South Carolina Medicaid’s shift to separate reimbursement for IPP-LARC was associated with increases in IPP-LARC initiation among adolescents and adults and flattening of the previously increasing trend in short-interval births among adolescents.

Limitations include that interrupted time series cannot exclude confounding due to other events occurring at the same time as the policy change. Data included Medicaid-funded services, and births paid by commercial payers could have been missed. Before the policy change, some IPP-LARC provision (ie, through training programs) could have occurred without claims. However, national survey data and reports from South Carolina support the finding of near-zero IPP-LARC use prior to the policy change.2

As of February 2018, 36 other states’ Medicaid programs have begun separately reimbursing for IPP-LARC,5 with calls for similar reforms from commercial payers.3 These findings suggest that IPP-LARC reimbursement could increase immediate postpartum contraceptive options and help adolescents avoid short-interval births.

Section Editor: Jody W. Zylke, MD, Deputy Editor.

References

- 1.Ahrens KA, Nelson H, Stidd RL, Moskosky S, Hutcheon JA. Short interpregnancy intervals and adverse perinatal outcomes in high-resource settings: an updated systematic review. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2019;33(1):O25-O47. doi: 10.1111/ppe.12503 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.White K, Teal SB, Potter JE. Contraception after delivery and short interpregnancy intervals among women in the United States. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;125(6):1471-1477. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000000841 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists’ Committee on Obstetric Practice Committee opinion No. 670: immediate postpartum long-acting reversible contraception. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;128(2):e32-e37. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000001587 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wachino V. State Medicaid Payment Approaches to Improve Access to Long-Acting Reversible Contraception. Baltimore, MD: Center for Medicaid and CHIP Services; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Moniz M. Reimbursement for Immediate Postpartum Contraception Outside the Global Fee: Improving Outcomes and Reducing Costs for Moms and Babies. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Institute for Healthcare Policy and Innovation; 2018. [Google Scholar]