Key Points

Question

How did Medicare spending, quality, volume of episodes, and patient characteristics change for primary lower extremity joint replacements after the Comprehensive Care for Joint Replacement model was instituted?

Findings

In the first 2 years, 90-day Medicare Part A spending decreased significantly by $582 per episode (−2.5%) associated with the Comprehensive Care for Joint Replacement model, driven by a 5.5% decrease in postacute spending. No detectable changes in hospital length of stay, readmissions, complications, 30- or 90-day mortality, volume of episodes, or patient characteristics relative to control were found.

Meaning

Over 2 years, the Comprehensive Care for Joint Replacement model was associated with reduced Medicare Part A spending driven by postacute savings, without changes in volume, quality, or patient selection.

Abstract

Importance

In 2016, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) launched its first mandatory bundled payment program, the Comprehensive Care for Joint Replacement (CJR) model, by randomizing metropolitan statistical areas (MSAs) into the payment model.

Objective

To evaluate changes in key economic and clinical outcomes associated with the CJR model.

Design, Setting, and Participants

A retrospective, national, population-based analysis of Medicare fee-for-service beneficiaries undergoing lower extremity joint replacement was conducted using 100% Medicare Part A data and 5% Medicare Part B data. Within an intention-to-treat framework, a difference-in-differences approach was used to compare Medicare spending, quality of care, volume of episodes, and patient selection in episodes of lower extremity joint replacements in the first 2 years of the program between propensity score–matched CJR and non-CJR hospitals (episodes initiated from April 1, 2016, through December 31, 2017, with the latter completed by March 31, 2018). Lower extremity joint replacement episodes in MSAs randomly assigned to the CJR model were compared with those in MSAs not assigned to the CJR model.

Exposures

Random assignment of MSAs into the CJR model within prespecified strata.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Spending and its components, quality of care, volume of episodes, and patient characteristics were the main outcomes.

Results

After propensity score matching, there were 157 828 primary lower extremity joint replacement cases across 684 hospitals in the CJR (treatment) group (101 641 [64.4%] women; mean [SD] age, 72.8 [8.9] years) and 180 594 cases across 726 hospitals in the non-CJR (control) group (115 580 women [64.0%] women; mean [SD] age, 72.6 [8.8] years). The CJR was associated with a decrease of $582 per episode in Medicare Part A spending, a 2.5% savings on claims (95% CI, −$873 to −$290; P < .001) driven by a 5.5% decline in 90-day postacute care spending, concentrated in skilled nursing facilities (−4.5% change from baseline; 95% CI, −$460 to −$26; P = .03) and inpatient rehabilitation facilities (−22.9% change from baseline; 95% CI,−$497 to −$176; P < .001). Estimated savings on claims, while consistent with changes in practice patterns, may not have exceeded the reconciliation payments to hospitals reported by CMS to date. No significant changes in hospital length of stay, readmissions, complications, 30- or 90-day mortality, volume of episodes, or patient characteristics relative to control were found.

Conclusions and Relevance

The CJR was associated with reduced Medicare Part A spending on claims over 2 years, largely through lower postacute spending. Mandatory bundled payments may serve as a useful model for policy efforts to change clinicians’ and facilities’ behavior without harming quality.

This population-based study examines the changes in economic and clinical outcomes after institution of the Comprehensive Care for Joint Replacement bundled payment program by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services.

Introduction

In April 2016, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) initiated its first mandatory bundled payment program, the Comprehensive Care for Joint Replacement (CJR) model.1 The CJR aimed to improve the value of care for patients undergoing lower extremity joint replacements. By paying hospitals a bundled payment that covered essentially all services from hospitalization through 90 days after discharge, the CJR encouraged hospitals and allied clinicians and facilities to work together to reduce spending and improve the quality of care.

The CJR provided a unique experiment to assess the outcome of a mandatory bundled payment model in a clinical domain with potential for savings.2 Within the program, hospitals could earn a reconciliation payment from CMS (shared savings) if total Medicare fee-for-service payments for the joint replacement episode were less than a target set by CMS based on a combination of a hospital’s historical spending and regional spending.3 Only hospitals that met CMS quality thresholds would be eligible for the reconciliation payment, which was capped at 5% of the target in the first calendar year (2016) and 10% in the second (2017). Hospitals had no downside financial risk in 2016, the first year, if total CMS payments exceeded the target or if quality was below the CMS threshold, but began to assume downside risk of up to 5% of the target in 2017. Early evidence from the first 9 months of the CJR showed decreased use of institutional postacute care, mixed results on spending, and no effects on quality.4,5 Before the CJR, 2 voluntary CMS bundled payment models for lower extremity joint replacements—the Acute Care Episode demonstration and the Bundled Payments for Care Improvement (BPCI)—were also associated with mixed results on spending and no significant changes in quality.6,7,8,9

We studied changes in spending, quality, volume of episodes, and patient characteristics associated with the CJR model over the first 2 years of the program (episodes initiated from April 1, 2016, through December 31, 2017, with the latter completed by March 31, 2018).

Methods

Study Design

We conducted a retrospective, national, population-based analysis of Medicare fee-for-service beneficiaries undergoing lower extremity joint replacement. The study was approved by the institutional review board of Harvard Medical School.

The CJR was implemented through the random assignment of metropolitan statistical areas (MSAs) into the model. The CMS first grouped MSAs into 8 strata according to population size and historical spending and then randomized a portion of MSAs within each stratum into the CJR. Initially, 75 such MSAs were randomly selected into the CJR, within which all hospitals were required to participate, provided they were not participating in the BPCI program for lower extremity joint replacements.3 After subsequent CMS modifications to the exclusion criteria, 67 of the initial 75 MSAs were retained in the CJR.1,10

Target spending for the episode set by the CMS included all Medicare Part A and B claims payments through 90 days postdischarge, except a list of specific claims that the CMS identified as unlikely to be related to a lower extremity joint replacement.11 Given that patients with hip fractures have higher needs after discharge, the CMS set a different target price for hip fracture episodes.12

We used an intention-to-treat approach within a difference-in-differences framework to compare episodes of care among hospitals in treatment and control MSAs. Despite the reduction of MSAs in the CMS final rule, we considered all hospitals in the randomly assigned 75 MSAs to be eligible for the treatment group, as the 8 excluded MSAs may have been plausibly affected by the program. Hospitals from the 121 MSAs not selected to participate in CJR composed the control group. We excluded all 155 hospitals in the BPCI program for major joint replacement of the lower extremity from the 196 eligible MSAs. To balance the treatment and control groups before analysis, we matched hospitals within each of the 8 CMS strata based on a propensity score calculated using preintervention hospital characteristics, including patient case mix, nature of lower extremity joint replacement cases, volume of cases, bed size, and discharge disposition (eFigure 1 in the Supplement).13 We restricted the analysis to episodes from matched hospitals.

This evaluation spanned the first 24 months of the program (ie, the first 2 full performance years), with our postintervention period defined as April 2016, when hospitals began facing CJR incentives, through March 2018 when the last episodes were completed. Our preintervention period spanned January 2014 through July 2015, when the CMS first announced the CJR model. We omitted the intervening period between July 2015 and April 2016 during which the public comment period and final rule were taking place, given that public knowledge of the program existed but hospitals had yet to face incentives.

Data Source

We used 100% Medicare Part A and 5% Part B fee-for-service claims data from January 2014 through March 2018. The Part B claims data included a consistent subsample of fee-for-service Medicare beneficiaries across years. We identified episodes of lower extremity joint replacement (typically knee and hip replacements) using the billing Medicare Severity Diagnosis Related Group (MS-DRG) 469 or 470, denoting major joint replacement or reattachment of lower extremity, with and without major complication or comorbidity, respectively. Approximately 90% of Medicare episode spending for the CJR patients is for Part A coverage, for which we analyzed the 100% claims data. The CJR excluded patients who died within 90 days of hospital discharge; we included those patients to assess changes in mortality. Following CJR exclusion criteria as set forth by the CMS, we excluded beneficiaries without Medicare as their primary payer or enrolled in Medicare Advantage.1

Statistical Analysis

Within our intention-to-treat framework, we used a difference-in-differences approach to assess changes in key economic and clinical outcomes associated with the CJR. The dependent variables included Medicare spending, quality of care, volume of episodes, and patient characteristics. In analyzing Medicare spending, we focused on Part A spending using the 100% Part A claims and distinguished Part A spending for the index hospitalization from Part A spending on postacute care during the 90-day period following the index hospitalization. Given that the postdischarge period was a substantive opportunity to influence spending, specifically through changes in postacute care, we further decomposed Part A postacute spending into its components: skilled nursing facilities, inpatient rehabilitation facilities, home health agencies, readmissions, long-term care hospitals, psychiatric hospitals, and other outpatient payments. We augmented these detailed Part A spending analyses with 5% Part B claims, which allowed us to analyze changes in Part B spending on physician and other services among a 5% subsample of the episodes. Within this 5% subsample, we were also able to assess total Medicare spending, calculated as the sum of Part A and Part B spending. We adjusted spending for geographic differences in regional labor costs and practice expense following the CMS Standardization Methodology.14 Outcomes related to quality of care included the length of stay of the hospitalization, 90-day complication rates, 90-day readmission rates, and 30-day as well as 90-day mortality rates.

For our spending and quality analyses, we used a linear ordinary least-squares model at the episode level15,16 in which we regressed the outcome of interest on a vector of episode-level characteristics, including beneficiary age and sex; the CMS Hierarchical Condition Category risk score17; an indicator for hip fracture status; a vector of quarter-year indicators; and interactions between each quarter-year indicator and an indicator denoting initial randomization of the index hospital where the episode was triggered into the CJR, consistent with our intention-to-treat approach (irrespective of any subsequent exit). To account for unobserved time-invariant hospital characteristics, we included a hospital fixed effect. The interactions between the quarter-year indicators and the indicator of random assignment into the CJR produced our coefficients of interest. We calculated mean program effects using a linear combination of these interaction term coefficients in the post-CJR period. Standard errors were clustered at the hospital level.

Our measures of use comprised the volume of lower extremity joint replacement episodes (MS-DRG 469 and 470) per 1000 fee-for-service Medicare beneficiaries triggered. To account for potential shifts in volume between hospitals within MSAs, we examined changes in use using an analogous difference-in-differences model at the MSA level.

Furthermore, because bundled payment incentives might lead hospitals to differentially select patients of certain risk or clinical profiles, we conducted analyses of selection using a similar model at the MSA level. We examined changes in the mean age, sex, and CMS Hierarchical Condition Category risk score of beneficiaries admitted for lower extremity joint replacements. We also examined changes in the proportion of episodes that involved a hip fracture.

In secondary analyses, we examined changes in skilled nursing facility and inpatient rehabilitation facility spending—the 2 largest components of postacute care spending—among episodes that involved admission to these postacute facilities. Other outcomes of interest, such as pain and functional status, were not available in the administrative claims data. In sensitivity analyses, we examined changes in spending among episodes in the 67 MSAs that received the full CJR treatment relative to controls. We used an instrumental variables approach in which we allowed initial random assignment to the CJR to serve as the instrument for eventual receipt of full CJR treatment, analogous to prior work in the literature.3,18 We also tested the robustness of our main results after excluding hip fracture cases from the sample. Results are reported with 2-tailed P values, with P < .05 considered significant. Statistical analysis was conducting using R, version 3.5.1 (R Core Team).

Results

Sample

We identified 815 hospitals in MSAs that were randomly selected to participate in the CJR and 955 hospitals in MSAs that were randomly selected not to participate in the program (eTable 1 in the Supplement). At the hospital and episode levels, baseline preintervention differences in hospital and episode characteristics between treatment and control groups were statistically significant. After the propensity score match (eFigure 2 in the Supplement), 684 hospitals from CJR MSAs and 726 hospitals from non-CJR MSAs composed our main analytic sample. Baseline characteristics exhibited improved balance, and the standardized mean difference decreased after propensity score matching (Table 1). Within a joint replacement episode, Medicare Part A spending accounted for a mean of 88% in the CJR group and 89% in the non-CJR group with Part B spending accounting for the remainder.

Table 1. Baseline Characteristics of Treatment and Control Groupsa.

| Variable | Treatment Group (CJR) (n = 684) | Control Group (Non-CJR) (n = 726) | Standardized Mean Difference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Area characteristics | NAb | ||

| MSAs, No. | 73 | 121 | |

| Mean MSA population, No. | 1 376 941 | 952 203 | |

| Hospital characteristics | |||

| Teaching, No. (%) | 367 (53.7) | 375 (51.7) | 0.032 |

| Beds, mean (SD), No. | 313 | 313 | 0.009 |

| Episode characteristics | |||

| Total CJR episodes, No. | 157 828 | 180 594 | |

| Hip fracture, No. (%) | 20 675 (13.1) | 22 755 (12.6) | 0.014 |

| Age, mean (SD), y | 72.8 (8.9) | 72.6 (8.8) | 0.022 |

| Women, No. (%) | 101 641 (64.4) | 115 580 (64.0) | 0.009 |

| CMS-HCC risk score, mean (SD)c | 1.09 (1.03) | 1.08 (1.02) | 0.008 |

| Length of stay, mean (SD), d | 4.22 (1.9) | 4.08 (1.8) | 0.07 |

| Medicare Part A spending, mean (SD), $d | 23 483 (14 447) | 22 874 (14 301) | 0.042 |

| Index admission spending, mean (SD), $ | 12 808 (1638) | 12 782 (1578) | 0.016 |

| 90-d Postacute care spending, mean (SD), $ | 10 675 (13 944) | 10 092 (13 833) | 0.042 |

| Skilled nursing facility | 5456 (10 166) | 5174 (9726) | 0.028 |

| Inpatient rehabilitation facility | 1470 (5138) | 1258 (4744) | 0.043 |

| Home health agency | 1863 (1782) | 1775 (1773) | 0.049 |

| Readmission payments | 1172 (4815) | 1093 (4715) | 0.017 |

| Long-term care payments | 111 (2369) | 155 (3053) | 0.016 |

| Psychiatric unit payments | 21 (633) | 23 (650) | 0.002 |

| Outpatient payments | 582 (1032) | 615 (1056) | 0.031 |

| Medicare Part B spending, $ mean (SD),e | 3012 (1450) | 2909 (1358) | 0.073 |

| Total 90-d episode spending, mean (SD), $e | 26 548 (15 099) | 25 719 (14 490) | 0.056 |

Abbreviations: CJR, Comprehensive Care for Joint Replacement; CMS-HCC, Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Hierarchical Condition Category; MSA, metropolitan statistical area; NA, not applicable.

Baseline characteristics compared between treatment and control groups following propensity score matching (intention to treat). Both Medicare Severity Diagnosis Related Group 470 and 469 episodes were included, which denoted major joint replacement or reattachment of lower extremity without and with major complication conditions, respectively. Characteristics were calculated from the preintervention period January 2014 through July 2015 (before initial CJR announcement).

Data are population statistics, and standardized mean difference does not apply to these measures.

Beneficiary risk scores were calculated using the CMS-HCC model, 2017 model year program.

All Medicare Part A spending outcomes were derived using the 100% Medicare Part A claims data.

Medicare Part B and total 90-day episode spending were derived using the 5% Medicare Part B claims data. Thus, these results are not directly comparable to the Part A spending results, as they were derived from a subsample of Medicare beneficiaries.

Spending

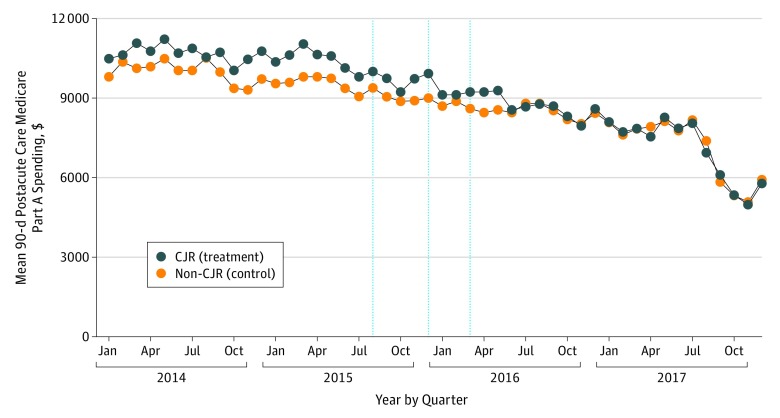

Total Medicare Part A spending decreased by a mean of $582 per episode among episodes in MSAs randomly assigned to the CJR relative to that among episodes in non-CJR MSAs over the first 2 years of the program, a 2.5% savings from baseline (95% CI, −$873 to −$290; P < .001) compared with the mean pre-CJR episode spending in the treatment group (Table 2). Within Part A spending, spending on the index admission did not change (a difference of $3 per episode; 0.0% relative to baseline; 95% CI, −$26 to $32; P = .83). Rather, the claims savings were explained by a decline in 90-day postacute care spending of $585 per episode, a 5.5% savings relative to the pre-CJR mean (95% CI, −$874 to −$296; P < .001). The Figure shows unadjusted 90-day, postacute care spending in the treatment and control groups across the study period.

Table 2. Changes in Spending and Quality of Care Associated With Random Assignment Into the CJRa.

| Variable | Change in Outcome Associated With the CJR | Baseline Pre-CJR Mean in CJR Group | Change Relative to Baseline, % (95% CI) | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spending outcomes per episode, $ | ||||

| Medicare Part A spendingb | −582 | 23 483 | −2.5 (−873 to −290) | <.001 |

| Index admission spending | 3 | 12 808 | 0.0 (−26 to 32) | .83 |

| 90-d Postacute care spending | −585 | 10 675 | −5.5 (−874 to −296) | <.001 |

| Skilled nursing facility | −243 | 5456 | −4.5 (−460 to −26) | .03 |

| Inpatient rehabilitation facility | −337 | 1470 | −22.9 (−497 to −176) | <.001 |

| Home health agency | 35 | 1863 | 1.9 (−47 to 118) | .40 |

| Readmission spending | −50 | 1172 | −4.3 (−143 to 43) | .29 |

| Long-term care hospital | −3 | 111 | −2.6 (−44 to 39) | .89 |

| Psychiatric units | −7 | 21 | −32.6 (−18 to 6) | .23 |

| Outpatient payments | 20 | 582 | 3.4 (0 to 40) | .05 |

| Medicare Part B spendingc | −68 | 3012 | −2.3 (−205 to 69) | .33 |

| Total 90-d episode spendingc | −730 | 26 548 | −2.7 (−1745 to 286) | .16 |

| Quality outcomes | ||||

| Hospitalization length of stay, d | 0.01 | 4.2 | 0.2 (−0.03 to 0.04) | .44 |

| 90-d Readmission rate, % | −0.01 | 10.0 | −0.1 (−0.08 to 0.03) | .80 |

| 90-d Complication rate, %d | 0.26 | 2.6 | 10.2 (−0.04 to 0.56) | .09 |

| 30-d Mortality rate, % | 0.01 | 2.1 | 0.2 (−0.30 to 0.30) | .98 |

| 90-d Mortality rate, % | −0.05 | 2.5 | −1.8 (−0.33 to 0.24) | .75 |

Abbreviation: CJR, Comprehensive Care for Joint Replacement.

Estimates of changes in outcomes at the episode level associated with random assignment of the index hospital into the CJR model (intention to treat). The model was adjusted for age, sex, Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Hierarchical Condition Category risk score, indicator for hip fracture status, hospital fixed effect, a vector of quarter indicators, and interactions between each quarter and CJR status. Preintervention spanned January 2014 to July 2015; postintervention, April 2016 to March 2018. All Medicare Severity Diagnosis Related Group 470 and 469 episodes were included.

All Medicare Part A spending outcomes per episode were derived using the 100% Medicare Part A claims data.

Medicare Part B and total 90-day episode spending were derived using the 5% Medicare Part B claims data. Thus, these results are not directly comparable to the Part A spending results, as they were derived from a subsample of Medicare beneficiaries in the data.

Primary elective total hip arthroplasty and total knee arthroplasty 90-day complication rate.

Figure. Medicare Spending on Postacute Care in the 90 Days After Discharge per Episode.

Unadjusted, 90-day postacute care spending among episodes with index admissions at Comprehensive Care for Joint Replacement (CJR) hospitals and non-CJR hospitals. All Medicare Severity Diagnosis Related Group 470 and 469 episodes were included. Data points denote the month of the index admission; thus, the last data point shown is 3 months before the end of data availability. The first vertical line indicates the initial CJR announcement by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid (CMS), the second vertical line indicates the release of the CMS final rule, and the third vertical line was the start of the CJR model.

Savings within postacute claims were explained by lower spending on skilled nursing facilities (−$243 per episode or −4.5%; 95% CI, −$460 to −$26; P = .03) and inpatient rehabilitation facilities (−$337 per episode or −22.9%; 95% CI, −$497 to −$176; P < .001). No statistically significant changes were detected in other segments of Part A spending, including on home health agencies ($35 or 1.9% per episode; 95% CI, −$47 to $118; P = 0.40), readmissions (−$50 per episode or −4.3%; 95% CI, −$143 to $43; P = 0.29), long-term care hospitals (−$3 per episode or −2.6%; 95% CI, −$44 to $39; P = 0.89), psychiatric hospitals (−$7 per episode or −32.6%; 95% CI, −$18 to $6; P = .23), or outpatient payments ($20 per episode or 3.4%; 95% CI, $0 to $40; P = .05) (Table 2).

In our 5% subsample of beneficiaries with Medicare Part B data, changes in Part B spending were not statistically significant (−$68 per episode or −2.3%; 95% CI, −$205 to $69; P = .33). Total Part A and B claims spending for the 5% subsample was estimated to have decreased by a mean of $730 per episode among CJR hospitals relative to non-CJR hospitals (2.7% savings), but this was less statistically precise (95% CI, −$1745 to $286; P = .16) owing in part to the smaller sample size of the 5% population (Table 2).

Results were qualitatively similar when excluding or including only hip fracture cases (eTable 2 in the Supplement). Tests of preintervention spending trends between treatment and control showed that differences were not statistically significant (eTable 3 in the Supplement). Instrumental variables analysis of the 67 MSAs that received full treatment in the CJR produced qualitatively similar results relative to our main findings, including Part A savings of $522 per episode (2.2% savings; 95% CI, −$820 to −$225; P < .001) and a 4.8% reduction in postacute spending ($522 per episode, 95% CI, −$816 to −$227; P < .001) (eTable 4 in the Supplement).

Estimates of net savings require comparing savings on claims with reconciliation payments to hospitals from the program. The CMS reported that the mean reconciliation payment to hospitals was $872 per episode over the first 2 years.3 This amount exceeds our estimated savings on Medicare Part A claims and is closer to, but also exceeds, our estimated savings from Part A and Part B claims using the 5% subsample, although that estimate was statistically less precise. This comparison is limited by differences in the sample; CMS payments were calculated across all episodes nationwide, whereas our sample was generated using the exclusion criteria and propensity match. Moreover, this study included episodes extending into quarter 1 of 2018, whereas CMS payments reported on episodes ending in 2016-2017. Nevertheless, this crude comparison cautions that savings on claims, while consistent with changes in clinician or hospital behavior, may not have exceeded the reconciliation payments from the CMS in the first 2 years.

Quality

The CJR was not associated with a statistically significant change relative to baseline in mean length of stay during the index hospitalization (0.2%; 95% CI, −0.03 to 0.04 days), 90-day readmission rates (−0.1%; 95% CI, −0.08% to 0.03%), 90-day complication rates among hip and knee replacements (10.2%; 95% CI, −0.04% to 0.56%), 30-day mortality rates (0.2%; 95% CI, −0.30% to 0.30%), or 90-day mortality rates (−1.8%; 95% CI, −0.33% to 0.24%) (Table 2; and eTable 2 in the Supplement).

Volume of Episodes

At the MSA level, the CJR was not associated with statistically significant changes in the volume of joint replacement episodes per 1000 beneficiaries triggered at CJR hospitals relative to those at non-CJR hospitals (0.30 episodes for MS-DRG 470: 95% CI, −0.09 to 0.68; P = .13; and 0.02 episodes for MS-DRG 469: 95% CI, −0.41 to 3.85; P = .11) (Table 3; and eTable 5 in the Supplement).

Table 3. Changes in Use and Patient Characteristics Associated With Random Assignment Into the CJRa.

| Variable | Change in Outcome Associated With the CJR | Baseline Pre-CJR Average in CJR Group | Change Relative to Baseline, % (95% CI) | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Medicare use outcomesb | ||||

| MS-DRG 470 episodes per 1000 beneficiaries | 0.30 | 2.32 | 12.8 (−0.09 to 0.68) | .13 |

| MS-DRG 469 episodes per 1000 beneficiaries | 0.02 | 0.12 | 14.3 (−0.41 to 3.85) | .11 |

| Patient characteristics | ||||

| Age, y | −0.08 | 72.8 | −0.1 (−0.35 to 0.19) | .54 |

| Women, % | 0.21 | 64.4 | 0.3 (−0.49 to 0.91) | .56 |

| Hip fracture episodes, % | 0.02 | 13.1 | 0.1 (−1.39 to 1.42) | .98 |

| CMS-HCC risk score | 0.004 | 1.09 | 0.4 (−0.029 to 0.037) | .81 |

Abbreviations: CJR, Comprehensive Care for Joint Replacement; CMS-HCC, Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Hierarchical Condition Category.

Changes in use outcomes and patient characteristics at the metropolitan statistical area (MSA) level associated with random assignment of the MSA into the CJR model. Dependent variables included a vector of quarter indicators, interactions between each quarter and CJR status, and MSA fixed effect. All Medicare Severity Diagnosis Related Group (MS-DRG) 470 and 469 episodes were included. The CMS-HCC risk score was calculated using age, sex, and diagnoses.

Volume of episodes was measured on a quarterly basis at the MSA level. MS-DRG 470 and MS-DRG 469 episodes denote major joint replacement or reattachment of lower extremity without and with major complication conditions, respectively.

Patient Selection

We found no evidence that the CJR was associated with a change in the characteristics of patients undergoing joint replacements at the MSA level. Specifically, we found no changes in the mean age, sex, CMS Hierarchical Condition Category score, and proportion of cases involving a hip fracture among patients at CJR hospitals relative to non-CJR hospitals (Table 3). Results were mostly consistent when excluding hip fracture cases or within hip fracture cases (eTable 5 in the Supplement).

Secondary Analyses

Among episodes that involved a skilled nursing facility stay, spending on skilled nursing facilities decreased by $842 per episode, a 5.9% savings (95% CI, −$1237 to −$446; P < .001). This decrease was consistent with a 1.5-day decline in mean length of stay at skilled nursing facilities (95% CI, −2.2 to −0.9 days; P < .001) and modestly lower unadjusted use rates (from 38.3% to 28.6% for the CJR group and 38.0% to 28.6% for the non-CJR group) (Table 4; and eTable 6 in the Supplement). Meanwhile, among episodes that involved an inpatient rehabilitation facility stay, spending on those facilities did not change significantly, nor did rehabilitation facility length of stay, although such facilities appeared to have been used less frequently (from 8.8% to 4.6% for the CJR group and 7.4% to 5.5% for the non-CJR group) (Table 4; eTable 6 in the Supplement). Results were similar without hip fracture cases (eTable 7 in the Supplement).

Table 4. Changes in Institutional Postacute Spending and Length of Stay Among Episodes With Institutional Postacute Care Associated With Random Assignment Into the CJRa.

| Variable | Change in Outcome Associated With the CJR | Baseline Pre-CJR Average in CJR Group | Change Relative to Baseline, % (95% CI)b | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Skilled nursing facilities | ||||

| Payments, $ | −842 | 14 245 | −5.9 (−1237 to −446) | <.001 |

| LOS per visit, d | −1.5 | 25.4 | −5.9 (−2.2 to −0.9) | <.001 |

| Payment per day, $ | 9 | 522 | 1.7 (−1 to 18) | .07 |

| Inpatient rehabilitation facilities | ||||

| Payments, $ | 394 | 16 730 | 2.4 (−367 to 1155) | .31 |

| LOS per visit, d | −0.1 | 11.8 | −0.9 (−0.5 to 0.2) | .53 |

| Payment per day, $ | 79 | 1554 | 5.1 (8 to 150) | .03 |

Abbreviations: CJR, Comprehensive Care for Joint Replacement; LOS, length of stay.

Episode-level changes in spending, LOS, and average Medicare payments per day at skilled nursing facilities (SNFs) and inpatient rehabilitation facilities (IRF) associated with the CJR for episodes in which the beneficiary was admitted to an SNF or IRF.

Percent change was defined as a share of the baseline level of the outcome among this subset of episodes.

Discussion

The CJR model is the first wide-scale mandatory bundled payment model implemented by the CMS in a randomized fashion. In this evaluation of the first 2 full years (episodes initiated from April 1, 2016, through December 31, 2017, with the latter completed by March 31, 2018), we found that the CJR was associated with a 2.5% decrease in 90-day Medicare Part A spending per episode, without detectable changes in the volume of inpatient admissions for primary hip and knee replacements, mean length of stay, complication rates of hip and knee replacements, 90-day readmissions, mortality out to 90 days, or characteristics of beneficiaries in whom the bundled payment was triggered. Lower episode spending on claims was driven by a decrease in 90-day postacute care spending, concentrated within skilled nursing facilities and inpatient rehabilitation facilities. There was a secular slowing in postacute spending among both the treatment and control groups during this period, but claims spending on episodes triggered by CJR hospitals slowed differentially more than claims spending triggered at non-CJR hospitals. However, our estimated savings on claims, while consistent with changes in clinician or hospital behavior, may not have exceeded the reconciliation payments to hospitals reported by the CMS to date. These estimates were more modest, although qualitatively similar, relative to a recent study of the CJR through 2017, in which estimated total savings on Part A and B claims within a 20% sample of Medicare beneficiaries ($1084 per episode) produced a net savings of 0.7%.19

Our finding that episode savings were driven by declines in postacute care spending is consistent with interim analyses and qualitative evidence of hospital strategy.3,4,20 Our results also provide clues to the mechanisms by which postacute savings were achieved. For skilled nursing facilities, savings were from reduced lengths of stay and reduced use. For inpatient rehabilitation facilities, savings were primarily the result of reduced use.

Our results are qualitatively similar to those of some evaluations of voluntary bundled payment models for joint replacements.5,6,7,8 A study of the Baptist Health System, for example, a participant in the Acute Care Episode demonstration and BPCI initiative, found a 20.8% decline in Medicare payments through lower postacute spending.21 Hospitals participating in the BPCI have been generally larger and had higher case volumes than CJR hospitals,22 although hospitals achieving savings across both programs had higher case volumes than hospitals without savings.23

The absence of changes in the volume of episodes or patient characteristics at the MSA level suggests that hospitals in the CJR, on average, generally did not perform operations on more patients or change their patient case mix in response to the program, similar to recent findings from the BPCI initiative.24 This finding suggests that savings within the episode were not offset by an increase in total episodes, which was a concern among earlier results from the BPCI initiative.25

Limitations

We note several limitations of the study. First, our measures of total 90-day episode spending and Part B spending used 5% Medicare Part B claims data, while the rest of our outcomes used 100% Part A claims. Thus, the lack of statistical significance in our total 90-day episode spending estimate is likely owing to a lack of precision from the smaller sample size in that model. Moreover, our Part A and total 90-day spending results may not be directly comparable, as the latter is derived from a 5% subsample of the former. Second, we analyzed the quantity of episodes and patient characteristics at the MSA level to test for volume and selection program-wide. Although this is of policy interest, it is agnostic toward potential within-MSA shifts in volume or selection effects between hospitals. Third, our results may not generalize to other bundled payment programs or future years of the CJR when the potential gains and losses for hospitals increase from 5% to 10%, then 20%, and the model became voluntary for hospitals in certain MSAs. Fourth, there may be spillover effects from other payment reforms differentially adopted by CJR relative to non-CJR hospitals. Fifth, despite the program design and statistical adjustments, it is possible that unobserved confounders may influence our results.

Conclusions

Mandatory bundled payments for lower extremity joint replacements may be a useful strategy for slowing spending without harming quality. In subsequent years of the CJR, hospitals begin to bear downside risk and face further potential upside gains, which could heighten CJR incentives. Moreover, episode target prices will increasingly be based on the performance of hospitals in a region; thus, as average spending in a region falls, target prices will likely decrease and hospitals may find it more difficult to generate savings beneath the target. Further studies will be needed to assess the results of these changes associated with the CJR program over time.

eTable 1. Baseline Characteristics of Treatment and Control Groups Before Propensity Score Match

eTable 2. Changes in Spending and Quality of Care Associated with Random Assignment into the CJR Without and Among Episodes with Primary Hip Fracture Diagnoses

eTable 3. Tests of Pre-intervention Trends Between Treatment and Control

eTable 4. Changes in Spending Associated With the CJR Among 67 Fully-Treated Metropolitan Statistical Areas

eTable 5. Changes in Utilization and Patient Characteristics Associated With Random Assignment Into the CJR Without and Among Episodes With Primary Hip Fracture Diagnoses

eTable 6. Average Post-Acute Care Usage Rates Among Treatment and Control Groups Before and After the CJR

eTable 7. Changes in Institutional Post-Acute Spending and Length of Stay Associated With Random Assignment Into the CJR Among Episodes With Institutional Post-Acute Care, Without and Among Primary Hip Fracture Diagnoses

eFigure 1. Description of Propensity Score Matching

eFigure 2. Propensity Score Distributions of CJR and Non-CJR Hospitals

References

- 1.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), HHS Medicare Program; Comprehensive Care for Joint Replacement Payment Model for acute care hospitals furnishing lower extremity joint replacement services: final rule. Fed Regist. 2015;80(226):73273-73554. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lam V, Teutsch S, Fielding J. Hip and knee replacements: a neglected potential savings opportunity. JAMA. 2018;319(10):977-978. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.2310 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Comprehensive Care for Joint Replacement model. https://innovation.cms.gov/initiatives/cjr. Updated March 18, 2019. Accessed January 9, 2019.

- 4.Finkelstein A, Ji Y, Mahoney N, Skinner J. Mandatory Medicare Bundled Payment program for lower extremity joint replacement and discharge to institutional postacute care: interim analysis of the first year of a 5-year randomized trial. JAMA. 2018;320(9):892-900. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.12346 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lewin Group CMS Comprehensive Care for Joint Replacement Model: performance year 1 evaluation report. https://innovation.cms.gov/Files/reports/cjr-firstannrpt.pdf. Published August 2018. Accessed January 9, 2019.

- 6.Chen LM, Ryan AM, Shih T, Thumma JR, Dimick JB. Medicare’s acute care episode demonstration: effects of bundled payments on costs and quality of surgical care. Health Serv Res. 2018;53(2):632-648. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.12681 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lewin Group CMS Bundled Payments for Care Improvement (BPCI) initiative models 2-4: year 1 evaluation & monitoring annual report. https://innovation.cms.gov/Files/reports/BPCI-EvalRpt1.pdf. Published February 2015. Accessed January 9, 2019.

- 8.Lewin Group CMS Bundled Payments for Care Improvement initiative models 24: year 4 evaluation & monitoring annual report. https://innovation.cms.gov/Files/reports/bpci-models2-4-yr4evalrpt.pdf. Published June 2018. Accessed January 9, 2019.

- 9.Dummit LA, Kahvecioglu D, Marrufo G, et al. Association between hospital participation in a Medicare bundled payment initiative and payments and quality outcomes for lower extremity joint replacement episodes. JAMA. 2016;316(12):1267-1278. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.12717 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Medicare program; cancellation of advancing care coordination through episode payment and cardiac rehabilitation incentive payment models; changes to Comprehensive Care for Joint Replacement Payment Model: Extreme and Uncontrollable Circumstances Policy for the Comprehensive Care for Joint Replacement Payment Model (CMS-5524-P). https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2017/12/01/2017-25979/medicare-program-cancellation-of-advancing-care-coordination-through-episode-payment-and-cardiac. Published December 1, 2017. Accessed January 9, 2019. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Comprehensive Care for Joint Replacement Model: episode exclusions. https://innovation.cms.gov/Files/worksheets/ccjr-exclusions.xlsx. Published July 30, 2018. Accessed January 9, 2019.

- 12.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Comprehensive Care for Joint Replacement Model: PBPM exclusions. https://innovation.cms.gov/Files/worksheets/cjr-icd10hipfracturecodes.xlsx. Published July 30, 2018. Accessed January 9, 2019.

- 13.Austin PC. An Introduction to propensity score methods for reducing the effects of confounding in observational studies. Multivariate Behav Res. 2011;46(3):399-424. doi: 10.1080/00273171.2011.568786 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.O’Donnell BE, Schneider KM, Brooks JM, et al. Standardizing Medicare payment information to support examining geographic variation in costs. Medicare Medicaid Res Rev. 2013;3(3):E1-E17. doi: 10.5600/mmrr.003.03.a06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wooldridge J. Econometric Analysis of Cross Section and Panel Data. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Buntin MB, Zaslavsky AM. Too much ado about two-part models and transformation? comparing methods of modeling Medicare expenditures. J Health Econ. 2004;23(3):525-542. doi: 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2003.10.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pope GC, Kautter J, Ellis RP, et al. Risk adjustment of Medicare capitation payments using the CMS-HCC model. Health Care Financ Rev. 2004;25(4):119-141. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Angrist J, Pischke J-S. Mostly Harmless Econometrics: An Empiricist’s Companion. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Barnett ML, Wilcock A, McWilliams JM, et al. Two-year evaluation of mandatory bundled payments for joint replacement. N Engl J Med. 2019;380(3):252-262. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1809010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhu JM, Patel V, Shea JA, Neuman MD, Werner RM. Hospitals using bundled payment report reducing skilled nursing facility use and improving care integration. Health Aff (Millwood). 2018;37(8):1282-1289. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2018.0257 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Navathe AS, Troxel AB, Liao JM, et al. Cost of joint replacement using bundled payment models. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(2):214-222. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.8263 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Navathe AS, Liao JM, Polsky D, et al. Comparison of hospitals participating in Medicare’s voluntary and mandatory orthopedic bundle programs. Health Aff (Millwood). 2018;37(6):854-863. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2017.1358 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Navathe AS, Liao JM, Shah Y, et al. Characteristics of hospitals earning savings in the first year of mandatory bundled payment for hip and knee surgery. JAMA. 2018;319(9):930-932. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.0678 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Navathe AS, Liao JM, Dykstra SE, et al. Association of hospital participation in a Medicare bundled payment program with volume and case mix of lower extremity joint replacement episodes. JAMA. 2018;320(9):901-910. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.12345 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fisher ES. Medicare’s bundled payment program for joint replacement: promise and peril? JAMA. 2016;316(12):1262-1264. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.12525 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eTable 1. Baseline Characteristics of Treatment and Control Groups Before Propensity Score Match

eTable 2. Changes in Spending and Quality of Care Associated with Random Assignment into the CJR Without and Among Episodes with Primary Hip Fracture Diagnoses

eTable 3. Tests of Pre-intervention Trends Between Treatment and Control

eTable 4. Changes in Spending Associated With the CJR Among 67 Fully-Treated Metropolitan Statistical Areas

eTable 5. Changes in Utilization and Patient Characteristics Associated With Random Assignment Into the CJR Without and Among Episodes With Primary Hip Fracture Diagnoses

eTable 6. Average Post-Acute Care Usage Rates Among Treatment and Control Groups Before and After the CJR

eTable 7. Changes in Institutional Post-Acute Spending and Length of Stay Associated With Random Assignment Into the CJR Among Episodes With Institutional Post-Acute Care, Without and Among Primary Hip Fracture Diagnoses

eFigure 1. Description of Propensity Score Matching

eFigure 2. Propensity Score Distributions of CJR and Non-CJR Hospitals