Key Points

Question

Are there differences in the use of diagnostic imaging between pediatric emergency departments located in the United States and Canada?

Findings

In this cohort study, overall and low-value diagnostic imaging use rates were lower in pediatric emergency departments in Ontario, Canada, than those in the United States. No differences in post–emergency department adverse outcomes were observed.

Meaning

There may be opportunities to safely reduce imaging rates in pediatric emergency departments in the United States.

This cohort study combines data from 4 pediatric emergency departments in Ontario, Canada, and 26 pediatric emergency departments in the United States to compare overall and low-value use of diagnostic imaging across pediatric emergency care.

Abstract

Importance

Diagnostic imaging overuse in children evaluated in emergency departments (EDs) is a potential target for reducing low-value care. Variation in practice patterns across Canada and the United States stemming from organization of care, payment structures, and medicolegal environments may lead to differences in imaging overuse between countries.

Objective

To compare overall and low-value use of diagnostic imaging across pediatric ED visits in Ontario, Canada, and the United States.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This study used administrative health databases from 4 pediatric EDs in Ontario and 26 in the United States in calendar years 2006 through 2016. Individuals 18 years and younger who were discharged from the ED, including after visits for diagnoses in which imaging is not routinely recommended (eg, asthma, bronchiolitis, abdominal pain, constipation, concussion, febrile convulsion, seizure, and headache) were included. Data analysis occurred from April 2018 to October 2018.

Exposures

Diagnostic imaging use.

Main Outcome and Measures

Overall and condition-specific low-value imaging use. Three-day and 7-day rates of hospital admission and those admissions resulting in intensive care, surgery, or in-hospital mortality were assessed as balancing measures.

Results

A total of 1 783 752 visits in Ontario and 21 807 332 visits in the United States were analyzed. Compared with visits in the United States, those in Canada had lower overall use of head computed tomography (Canada, 22 942 [1.3%] vs the United States, 753 270 [3.5%]; P < .001), abdomen computed tomography (5626 [0.3%] vs 211 018 [1.0%]; P < .001), chest radiographic imaging (208 843 [11.7%] vs 3 408 540 [15.6%]; P < .001), and abdominal radiographic imaging (77 147 [4.3%] vs 3 607 141 [16.5%]; P < .001). Low-value imaging use was lower in Canada than the United States for multiple indications, including abdominal radiographic images for constipation (absolute difference, 23.7% [95% CI, 23.2%-24.3%]) and abdominal pain (20.6% [95% CI, 20.3%-21.0%]) and head computed tomographic scans for concussion (22.9% [95% CI, 22.3%-23.4%]). Abdominal computed tomographic use for constipation and abdominal pain, although low overall, were approximately 10-fold higher in the United States (0.1% [95% CI, 0.1%-0.2%] vs 1.2% [95% CI, 1.2%-1.2%]) and abdominal pain (0.8% [95% CI, 0.7%-0.9%] vs 7.0% [95% CI, 6.9%-7.1%]). Rates of 3-day and 7-day post-ED adverse outcomes were similar.

Conclusions and Relevance

Low-value imaging rates were lower in pediatric EDs in Ontario compared with the United States, particularly those involving ionizing radiation. Lower use of imaging in Canada was not associated with higher rates of adverse outcomes, suggesting that usage may be safely reduced in the United States.

Introduction

Minimizing care that provides little benefit (ie, low-value care) has become an important focus for decreasing health care costs and improving the quality of care delivery.1 A key target for low-value care is emergency department (ED) diagnostic imaging overuse. Choosing Wisely, a campaign targeting overuse, was launched in 2012 and has spread internationally.2 Diagnostic imaging overuse in children who present to the ED accounts for 3 of the first 5 of the 2013 American Academy of Pediatrics Choosing Wisely Recommendations3 and 6 of 10 Choosing Wisely Recommendations in emergency medicine in Canada.4

Canadian and US populations have similar rates of ED use,5 but the systems differ in overall organization of care and payment structures.6 Canada provides government-funded universal access to acute care services, while residents in the United States receive care funded through a number of sources, including public coverage, private insurance, and/or out-of-pocket spending. There is an increased perception of medicolegal risk in the United States that could lead to overreliance on potentially low-yield diagnostic imaging.7,8 Consequently, varying practice patterns may account for differences in health care expenditures and diagnostic imaging use. It is unknown whether campaigns such as Choosing Wisely have affected the rates of low-value diagnostic imaging in pediatric EDs.

The aim of this study was to compare the use of diagnostic imaging in children evaluated in pediatric EDs in the United States and Ontario, Canada’s most populous province, and explore whether observed differences are associated with variation in outcomes. We hypothesized that rates of use would be higher in the United States for a subset of diagnoses in which diagnostic imaging is not routinely recommended without improved outcomes, thus reflecting potential overuse.

Methods

Study Design

This was a retrospective study of ED visits to children’s hospitals for individuals 18 years and younger from calendar years 2006 through 2016, using administrative health databases in Ontario, Canada, and the United States. We excluded patients who died in the ED, those transferred into the ED from another hospital, and those transferred to another facility for ongoing care. Ethics review for this study was obtained from the institutional review board of the Hospital for Sick Children. All data were deidentified in all sources, and consent was therefore waived. Diagnostic imaging and diagnostic codes from which data were collected are described in eTables 1 and 2 of the Supplement.

Population and Data Sets

Canada

Data from visits to any of Ontario’s 4 pediatric EDs were abstracted from population-based databases at ICES (formerly known as the Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences), an independent, nonprofit research institute whose legal status under Ontario’s health information privacy law allows it to collect and analyze health care and demographic data, without patient consent, for health system evaluation and improvement. These data sets were linked using an unique encoded patient-level identifiers and analyzed at ICES.9 Ontario is Canada’s most populous province, with about 14 million residents (approximately 40% of Canada’s population). Databases used included the National Ambulatory Care Reporting System, containing information on discharge diagnosis (International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision [ICD-10] codes), and admission-discharge-transfer systems for every ED visit in the province.10 The Ontario Health Insurance Plan database contains billing data for all publicly funded fee-for-service physician services in Ontario, including diagnostic imaging. The Canadian Institute for Health Information Discharge Abstract Database was used to evaluate clinical information for hospitalized patients. The Ontario Registered Persons Database was used to identify postal code of residence for included individuals.

United States

Data from the United States were abstracted from the Pediatric Health Information System database (from the Children’s Hospital Association). The Pediatric Health Information System database contains clinical and billing data from 51 not-for-profit, tertiary care children’s hospitals in the United States. Participating hospitals are located in 27 states plus the District of Columbia and account for approximately 13% of all pediatric ED visits in the United States (independent analysis conducted by the Children’s Hospital Association). The data collection, validation, and safeguarding procedures are assured through a joint effort between the Children’s Hospital Association and participating hospitals.11 In this study, we included data from the 26 hospitals with complete demographic and billing information during the study period for all ED encounters.

Variables

We abstracted the following characteristics of the ED visit: patient age, sex, neighborhood income quintile (derived in the data from Canada using postal code linkage at the level of dissemination area [400-700 residents] by applying 2011 census data and in data from the United States by zip code, linked to zip code tabulation areas from the 2010 census data), straight-line distance from the centroid of the child’s residential postal or zip code to the hospital’s postal or zip code, arrival day of week, and arrival time. Patient complexity was assessed using International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision or ICD-10, mapping to complex chronic conditions (CCCs).12 The presence of a CCC was ascertained using diagnoses associated with the ED visit or present during a prior ED visit or hospitalization to the same institution within the preceding 365-day period.

Imaging data were captured for the diagnostic modalities of chest radiographic imaging, abdominal radiographic imaging, abdominal ultrasonographic imaging, abdominal computed tomography (CT), head CT, and head magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Rates of use in the ED were collected for all users of the ED in both Ontario and the United States.

To assess the main study objective, potential low-value imaging use, we assessed imaging use in individuals who were discharged from the ED (ie, not admitted to the hospital). We limited the population to those individuals with visits resulting in discharge to focus on a lower-acuity population for whom routine use of imaging is not recommended.13 The conditions assessed were determined by 11 study authors (E.C., S.B.F., P.L.A., H.K.S., J.R.M., M.S.-K., E.R.A., R.B.M., S.S.S., A.P., and M.I.N.) by group consensus and included the following primary diagnoses and their associated imaging modalities: asthma (chest radiographic imaging),14,15 bronchiolitis (chest radiographic imaging),15,16 abdominal pain (abdominal radiographic imaging, abdominal ultrasonographic imaging, and abdominal CT),17 constipation (abdominal radiographic imaging, abdominal ultrasonographic imaging, and abdominal CT),18,19,20 concussion (head CT and head MRI),21,22 simple febrile convulsion (head CT),23 complex febrile convulsion (head CT),24 seizure (head CT and head MRI),25,26 and headache (head CT and head MRI).27

As balancing measures, we assessed whether patients who were discharged without imaging had deleterious outcomes by examining the rates of hospital admission within the 3-day and 7-day periods after the ED visit, and those admissions resulting in intensive care unit care hospitalization, surgery, or mortality. These outcomes were also evaluated in the full cohort of children, including children with imaging and children without imaging, to allow comparisons that incorporate possible differences in severity of illness or other diagnostic or therapeutic interventions between Ontario and the United States.

To assess the accuracy of imaging use capture across the 2 data sets, we measured imaging use for conditions in which diagnostic imaging is routinely indicated. These quality-control measures included hospitalized children with pneumonia (chest radiographic imaging), bowel obstruction (abdominal radiographic imaging), intussusception (abdominal ultrasonographic imaging), pancreatic or liver laceration (abdominal CT), ventricular shunt malfunction (head CT), and acute stroke (head MRI).

Analysis

Data were presented as proportions with 95% CIs. Comparisons between Canada and the United States were expressed as absolute differences (with 95% CIs calculated using standard formulas for differences in proportions) for the main analysis (an ED discharge diagnosis in which routine use of imaging is not recommended), for the 3-day and 7-day outcome balancing measures (hospitalization, a need for intensive care unit care, a need for surgery, or in-hospital mortality), and imaging rates for the quality-control measures. Since children with underlying comorbidities may be more likely to receive diagnostic imaging, we performed a sensitivity analysis limited to children without CCCs. Yearly proportions of imaging use were calculated to examine trends across the study period. Analyses were performed with SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Inc), and P values less than .001 were considered statistically significant because of the large sample sizes.

Results

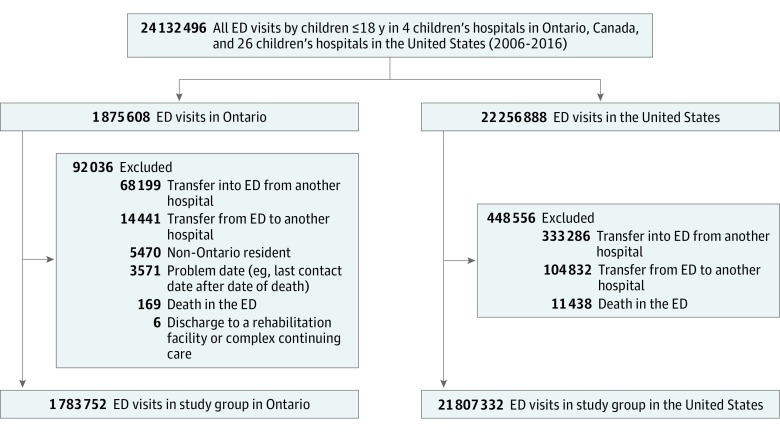

During the 10-year study period, there were 1 875 608 ED visits among children 18 years and younger to pediatric EDs in Ontario and 22 256 888 visits to the study pediatric EDs in the United States (Figure 1). After exclusions, 1 783 752 ED visits (95.1%) from Canada and 21 807 332 ED visits (98.0%) from the United States were included. In Ontario, the mean [SD] age was 6.1 [5.5] years, and 821 984 patients (46.1%) were female. In the United States, the mean [SD] age was 5.6 [5.3] years, and 10 198 965 patients (46.8%) were female.

Figure 1. Cohort Derivation.

ED indicates emergency department.

Compared with those in the United States, children presenting to pediatric EDs in Canada lived closer to the children’s hospital than those in the United States (Canada, 47 432 of 1 783 752 [2.7%]; the United States, 1 792 720 of 21 807 332 [4.2%] more than 80 km from the hospital; P < .001), resided in wealthier neighborhoods (340 155 [19.1%] vs 3 252 381 [14.9%] in the highest quintile; P < .001), were less likely to have a CCC (101 608 [5.7%] vs 1 792 720 [8.2%]; P < .001), and were less likely to be admitted to the hospital (135 189 [7.6%] vs 2 296 996 [10.5%]; P < .001; Table 1). No material differences were observed between Canadian and US ED visits with respect to patient age, sex, arrival day of the week, or arrival time.

Table 1. Characteristics of All Emergency Department Visits by Children 18 Years and Younger in 4 Children’s Hospitals in Ontario, Canada, and 26 Children’s Hospitals in the United States (2006-2016).

| Characteristic | Patients, No. (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Ontario (n = 1 783 752) | United States (n = 21 807 332) | |

| Age, mean (SD), y | 6.1 (5.5) | 5.6 (5.3) |

| Age group, y | ||

| <2 | 503 673 (28.2) | 6 716 541 (30.8) |

| 2-5 | 510 243 (28.6) | 6 157 384 (28.2) |

| 6-9 | 265 586 (14.9) | 3 566 308 (16.4) |

| 10-14 | 297 223 (16.7) | 3 404 154 (15.6) |

| 15-18 | 207 027 (11.6) | 1 962 945 (9.0) |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 961 768 (53.9) | 11 600 876 (53.2) |

| Female | 821 984 (46.1) | 10 198 965 (46.8) |

| Neighborhood income quintile | ||

| 1 (Lowest) | 415 443 (23.3) | 5 357 545 (24.6) |

| 2 | 345 899 (19.4) | 4 430 282 (20.3) |

| 3 | 321 844 (18.0) | 4 134 457 (19.0) |

| 4 | 348 233 (19.5) | 4 201 084 (19.3) |

| 5 (Highest) | 340 155 (19.1) | 3 252 381 (14.9) |

| Missing | 12 178 (0.7) | 431 583 (2.0) |

| Distance (categories), km | ||

| 0-10 | 982 566 (55.1) | 7 554 587 (35.5) |

| 11-30 | 563 086 (31.6) | 9 506 553 (44.7) |

| 31-50 | 143 322 (8.0) | 2 244 240 (10.6) |

| 51-80 | 47 346 (2.7) | 1 068 936 (5.0) |

| >80 | 47 432 (2.7) | 888 765 (4.2) |

| Any complex chronic condition | 101 608 (5.7) | 1 792 720 (8.2) |

| Emergency department disposition | ||

| Discharged | 1 648 563 (92.4) | 19 510 336 (88.8) |

| Admitted | 135 189 (7.6) | 2 296 996 (10.5) |

| Day of week | ||

| Weekday | 1 260 557 (70.7) | 15 349 280 (70.4) |

| Weekend | 523 195 (29.3) | 6 458 052 (29.6) |

| Arrival time | ||

| 12 am to 8 am | 219 308 (12.3) | 3 257 112 (15.0) |

| 8 am to 4 pm | 757 558 (42.5) | 7 887 930 (36.3) |

| 4 pm to 12 am | 806 886 (45.2) | 10 573 709 (48.7) |

| Imaging use among all ED visits | ||

| Computed tomography | ||

| Head | 22 942 (1.3) | 753 270 (3.5) |

| Abdomen | 5626 (0.3) | 211 018 (1.0) |

| Magnetic resonance imaging, head | 9224 (0.5) | 105 515 (0.5) |

| Radiographic imaging | ||

| Chest | 208 843 (11.7) | 3 408 540 (15.6) |

| Abdomen | 77 147 (4.3) | 3 607 141 (16.5) |

| Ultrasonographic imaging, abdomen | 69 750 (3.9) | 624 518 (2.9) |

Overall Imaging Use

Compared with children presenting to pediatric EDs in the United States, those in Ontario had lower overall use of head CT (Canada, 22 942 [1.3%] vs the United States, 753 270 [3.5%]; P < .001), abdomen CT (5626 [0.3%] vs 211 018 [1.0%]; P < .001), chest radiography (208 843 [11.7%] vs 3 408 540 [15.6%]; P < .001), and abdominal radiography (77 147 [4.3%] vs 3 607 141 [16.5%]; P < .001). Use of abdominal ultrasonographic imaging was higher in Canada compared with the United States (69 750 [3.9%] vs 624 518 [2.9%]; P < .001), while MRI head use was 0.5% of ED visits in both countries (9224 in Canada and 105 515 in the United States).

Low-Value Imaging Use

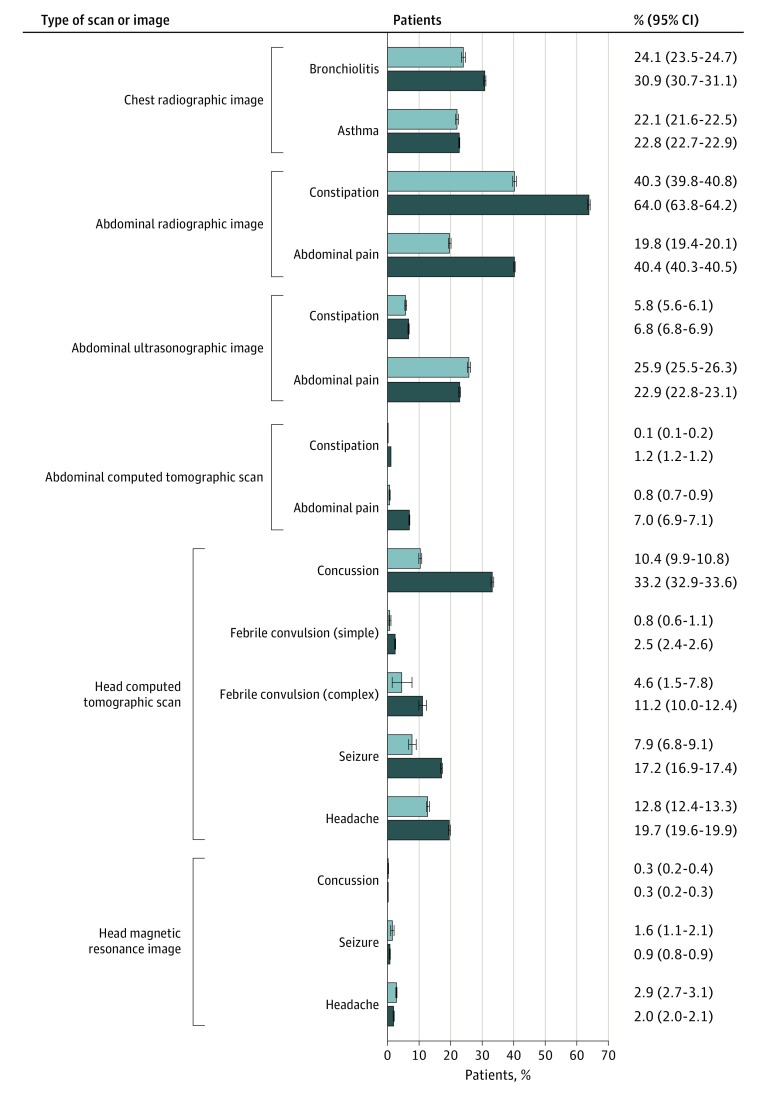

Imaging use for patients who were discharged from the ED with a diagnosis in which routine use of imaging is not recommended across all years is presented in Figure 2. For chest radiography, compared with pediatric EDs in the United States, use was lower in Ontario for both bronchiolitis (absolute difference, 6.8% [95% CI, 6.2%-7.4%]) and asthma (absolute difference, 0.7% [95% CI, 0.3%-1.1%]). For abdominal radiography, use was lower in pediatric EDs in Ontario compared with the United States for both constipation (absolute difference, 23.7% [95% CI, 23.2%-24.3%]) and abdominal pain (absolute difference, 20.6% [95% CI, 20.3%-21.0%]). Use of abdominal CT in patients was uncommon in both countries for the target conditions, but approximately 10-fold lower in Canada than the United States for both constipation (0.1% [95% CI, 0.1%-0.2%] vs 1.2% [95% CI, 1.2%-1.2%]) and abdominal pain (0.8% [95% CI, 0.7%-0.9%] vs 7.0% [95% CI, 6.9%-7.1%]). Use of head CT was lower in Canada for febrile convulsion (both simple [absolute difference, 1.7% (95% CI, 1.4%-1.9%)] and complex [absolute difference, 6.6% (95% CI, 3.2%-9.9%)]), seizure (absolute difference, 9.2% [95% CI, 8.1%-10.3%]), and headache (absolute difference, 6.9% [95% CI, 6.4%-7.4%]) and, most notably, for concussion (absolute difference, 22.9% [95% CI, 22.3%-23.4%]). For nonionizing imaging modalities, use of abdominal ultrasonographic imaging was lower for constipation (5.8% [95% CI, 5.6%-6.1%] vs 6.8% [95% CI, 6.8%-6.9%]) and higher for abdominal pain (25.9% [95% CI, 25.5%-26.3%] vs 22.9% [95% CI, 22.8%-23.1%]) in Ontario than the United States. Use of head MRI for concussion, seizure, and headache did not show clinically meaningful differences across the 2 countries.

Figure 2. Condition-Specific Diagnostic Imaging Use Among Overall Discharges From the Emergency Department in 4 Children’s Hospitals in Ontario, Canada, and 26 Children’s Hospitals in the United States (2006-2016).

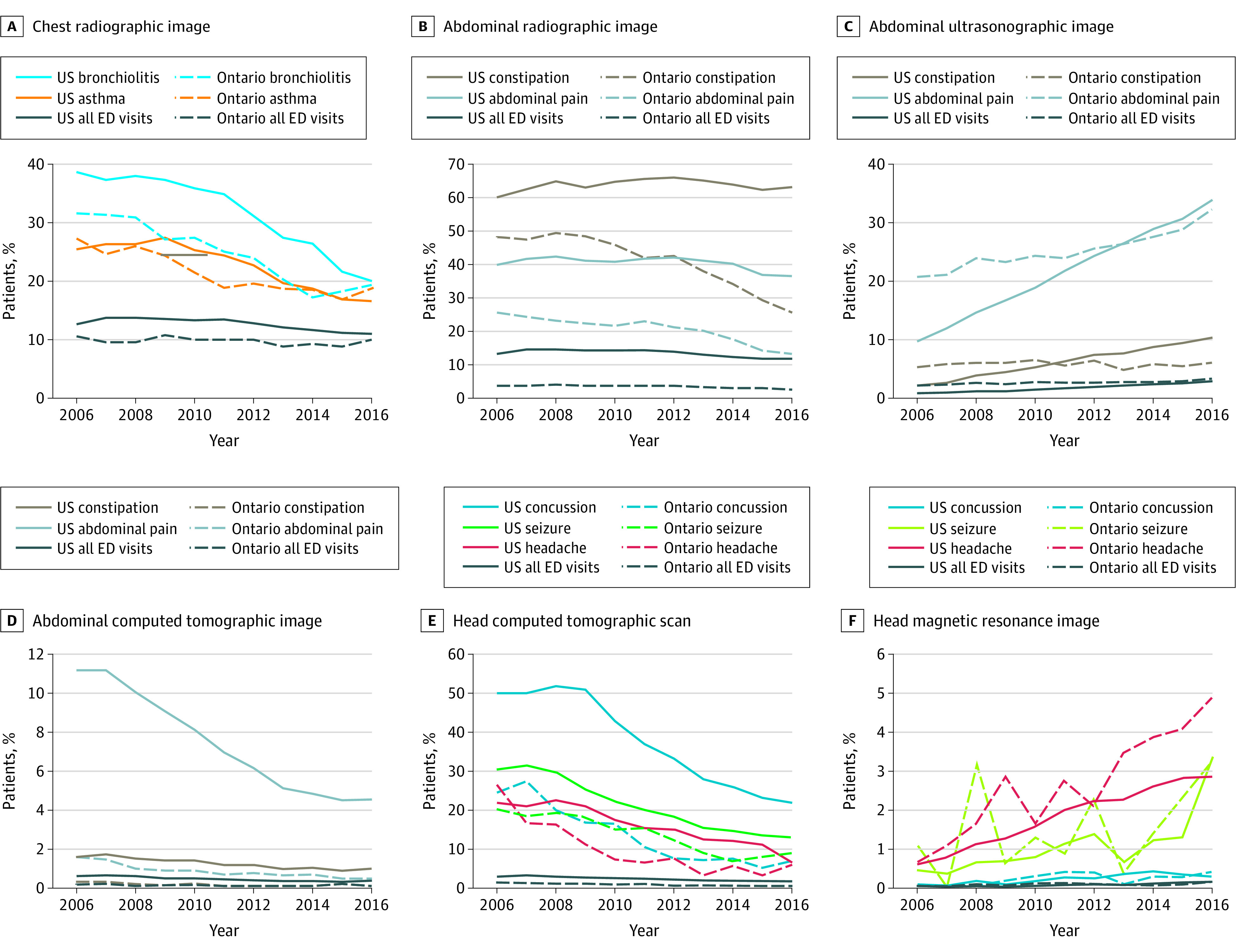

Trends in Imaging Over Time

Differences in low-value imaging between Ontario and the United States were not categorically sustained over the entire study period for all imaging modalities (Figure 3). In some cases, the difference between the 2 countries was reduced in more recent years. The 11-year difference in chest radiography use for bronchiolitis and asthma was −6.8% (95% CI, −7.4% to −6.2%) and −0.7% (95% CI, −1.1% to −0.3%), respectively. However, in 2016 alone, those differences were −1.0% (95% CI, −2.7% to 0.7%) and 3.0% (95% CI, 1.6%-4.4%), respectively (eTable 3 in the Supplement). For some diagnoses, differences in low-value imaging between Ontario and the United States varied in some imaging modalities but not others. While the use of abdominal ultrasonographic imaging for constipation in the United States compared with Canada was 3.1% lower in 2006 and 4.2% higher in 2016, rates of abdominal CTs and abdominal radiographic imaging for constipation remained higher in the United States across all 11 years.

Figure 3. Condition-Specific Diagnostic Imaging Use Among Discharges From the Emergency Department (ED) in 4 Children’s Hospitals in Ontario, Canada, and 26 Children’s Hospitals in the United States (2006-2016).

Data are presented by calendar year.

Outcomes After ED Visits in Ontario and the United States

There were no meaningful differences found in 3-day or 7-day hospitalization rates (or hospitalization resulting in intensive care unit care, operative care, or death) between individuals discharged from a pediatric ED in Ontario vs the United States including subanalyses of individuals without imaging during the index ED visit (Table 2 and eTable 4 in the Supplement), as well as among all children visiting the ED (with and without imaging; eTable 5 in the Supplement). An additional analysis limited to children without CCCs similarly did not yield substantive difference in the results (eTable 6 and eTable 7 in the Supplement).

Table 2. Admission and Intensive Care Unit Admission, Surgery, or Death Within 3 Days of Emergency Department Visit Among Discharged Children Without Imaging by Diagnosis in 4 Children’s Hospitals in Ontario and 26 Children’s Hospitals in the United States (2006-2016).

| Characteristic | Hospital Admission Within 3 d of Emergency Department Visit | Hospital Admission Within 3 d of Emergency Department Visit Resulting in Intensive Care Unit Admission, Surgery, or Death | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All Patients, No./Total No. (%) | Difference, % (95% CI) | Patients, No./Total No. (%) | Difference, % (95% CI) | |||

| Ontario | United States | Ontario | United States | |||

| Chest radiographic imaging | ||||||

| Bronchiolitis | 548/14 256 (3.8) | 7848/215 108 (3.6) | 0.2 (−0.1 to 0.5) | 23/14 256 (0.2) | 967/215 108 (0.4) | −0.3 (−0.4 to −0.2) |

| Asthma | 145/29 278 (0.5) | 6910/502 310 (1.4) | −0.9 (−1.0 to −0.8) | 9/29 278 (0.0) | 559/502 310 (0.1) | −0.1 (−0.1 to −0.1) |

| Abdominal radiographic imaging | ||||||

| Constipation | 98/19 930 (0.5) | 788/113 166 (0.7) | −0.2 (−0.3 to −0.1) | 22/19 930 (0.1) | 137/113 166 (0.1) | 0.0 (−0.1 to 0.0) |

| Abdominal pain | 476/41 167 (1.2) | 4479/289 917 (1.5) | −0.4 (−0.5 to −0.3) | 173/41 167 (0.4) | 1281/289 917 (0.4) | 0.0 (0.00-0.1) |

| Abdominal ultrasonographic image | ||||||

| Constipation | 224/31 443 (0.7) | 2935/292 974 (1.0) | −0.3 (−0.4 to −0.2) | 46/31 443 (0.1) | 582/292 974 (0.2) | −0.1 (−0.1 to 0.0) |

| Abdominal pain | 377/38 022 (1.0) | 5721/374 904 (1.5) | −0.5 (−0.6 to −0.4) | 135/38 022 (0.4) | 1591/374 904 (0.4) | −0.1 (−0.1 to 0.0) |

| Abdominal computed tomography | ||||||

| Constipation | 291/33 345 (0.9) | 3181/310 685 (1.0) | −0.2 (−0.3 to 0.0) | 67/33 345 (0.2) | 632/310 685 (0.2) | 0.0 (−0.1 to 0.0) |

| Abdominal pain | 720/50 888 (1.4) | 7015/452 381 (1.6) | −0.1 (−0.2 to 0.0) | 242/50 888 (0.5) | 1924/452 381 (0.4) | 0.1 (0.0-0.1) |

| Head computed tomography | ||||||

| Concussion | 13/15 563 (0.1) | 82/47 760 (0.2) | −0.1 (−0.1 to 0.0) | ≤5/15 563 | 10/47 760 (0.0) | NAa |

| Simple febrile convulsion | 74/5265 (1.4) | 1801/81 916 (2.2) | −0.8 (−1.1 to −0.5) | ≤5/5265 | 92/81 916 (0.1) | NAa |

| Complex febrile convulsion | ≤5/165 | 103/2513 (4.1) | NAa | ≤5/165 | ≤5/2513 | NAa |

| Seizure | 50/2109 (2.4) | 2588/70 488 (3.7) | −1.3 (−2.0 to −0.6) | ≤5/2109 | 280/70 488 (0.4) | NAa |

| Headache | 164/17 891 (0.9) | 3738/205 501 (1.8) | −0.9 (−1.1 to −0.8) | 23/17 891 (0.1) | 357/205 501 (0.2) | 0.0 (−0.1 to 0.0) |

| Head magnetic resonance imaging | ||||||

| Concussion | 28/17 315 (0.2) | 198/71 333 (0.3) | −0.1 (−0.2 to 0.0) | ≤5/17 315 | 21/71 333 (0.0) | NAa |

| Seizure | 55/2254 (2.4) | 3020/84 343 (3.6) | −1.1 (−1.8 to −0.5) | ≤5/2254 | 322/84 343 (0.4) | NAa |

| Headache | 204/19 929 (1.0) | 4770/250 813 (1.9) | −0.9 (−1.0 to −0.7) | 26/19 929 (0.1) | 592/250 813 (0.2) | −0.2 (−0.3 to −0.2) |

Abbreviation: NA, not available.

Unable to calculate owing to suppressed data as a result of small cell sizes.

Quality Controls

Use of imaging for the quality-control conditions was higher or similar among patients presenting to Ontario EDs compared with EDs in the United States (eFigure in the Supplement). This included admitted patients with pneumonia who had chest radiographic imaging (95.2% [95% CI, 94.7%-95.7%] vs 84.7% [95% CI, 84.4%-84.9%]; P < .001), patients with bowel obstruction who had abdominal radiographic imaging (96.2% [95% CI, 94.9%-97.5%] vs 90.0% [95% CI, 89.4%-90.5%]; P < .001), patients with intussusception who had abdominal ultrasonographic imaging (95.9% [95% CI, 94.1%-97.8%] vs 74.5% [95% CI, 73.6%-75.4%]; P < .001), patients with liver or pancreas laceration who had abdominal CT (85.7% [95% CI, 76.5%-94.9%] vs 56.9% [95% CI, 55.1%-58.8%]; P < .001), patients with shunt malfunction who had head CT (81.8% [95% CI, 79.3%-84.3%] vs 79.9% [95% CI, 79.2%-80.5%]; P = .15), and patients with acute stroke with head MRI (82.3% [95% CI, 75.3%-89.3%] vs. 75.2% [95 % CI, 73.2%-77.1%]; P = .06).

Discussion

Overall and condition-specific diagnostic imaging rates for a variety of conditions in which imaging is not routinely recommended were higher for children discharged from pediatric EDs in the United States compared with those located in Ontario, Canada. This was most pronounced for diagnostic imaging associated with ionizing radiation (ie, plain radiographs and CT), gastrointestinal diagnoses (ie, abdominal pain and constipation), and concussion. Furthermore, lower imaging rates in Canada were not associated with future hospitalization, intensive care unit admissions, surgery, or death, suggesting that imaging rates may be safely reduced in the United States.

Reports on population-level use suggest that imaging use is consistently higher in the United States than other high-income countries. Compared with Canada, the United States has a higher rate of use of both CT (153 vs 245 per 1000 population) and MRI (56 vs 118 per 1000 population).28 This study extends these findings to other imaging modalities and discharge diagnoses in pediatric EDs, except for MRI, for which rates were similar in both countries. The findings are consistent with a previous report of increased use of CT from 2003 to 2008 in both pediatric and adult patients presenting to EDs in the United States compared with Ontario.29 The overall proportion of children receiving a CT (4.7% in the United States and 1.4% in Ontario) was similar to the findings of this study.

There are a number of potential explanations for these findings. First, although many health care practitioners in both countries are remunerated in fee-for-service payment models, Canadian physicians practice within a broader system of strict global budgets for hospitals and regional health authorities.30 Such financial restrictions may reduce the overall volume of certain services, such as diagnostic imaging, leading to selective use of imaging in certain situations. Second, there may be differences in physician practice associated with differences in training31 and/or national guidelines32 in each country. However, guidelines are often outdated and may be poorly adhered to,33,34 and their use can cross international borders. Third, there may be heightened perception of medicolegal risk in the United States, which may result in reliance on diagnostic imaging for conditions in which the yield of imaging is low.35,36 Canadian physicians are named in malpractice suits approximately one-quarter as frequently as their US counterparts.37 The decline observed in both countries for some low-value imaging predated Choosing Wisely, possibly because of other published data on the risk of ionizing radiation in children.38,39,40 Fourth, patient and parent expectations may differ between the 2 countries. For example, in a setting of paying for services in the United States, the limiting of imaging may not be viewed favorably by some health care consumers. Fifth, patient populations may differ somewhat in the 2 countries, leading to different clinical practice in pediatric ED settings. For instance, patients in the United States may have higher levels of underlying medical complexity and hence may be more challenging to evaluate without imaging (eg, there were more patients with CCCs in the US pediatric EDs). However, exclusion of patients with CCCs did not meaningfully change the findings of this study. Sixth, some diagnostic imaging may be more readily available in pediatric EDs in the United States, although imaging use was higher for every quality-control indication in Ontario. Lastly, higher rates of uninsurance and underinsurance in the United States compared with universal health care coverage in Canada may lead to more reliance on diagnostic testing in the ED, because these patients may lack reliable follow-up care or alternative sources of health care services.

Limitations

We captured virtually all pediatric ED visits with minimal exclusions in the most populated region of Canada and in a representative sample of pediatric ED visits in the United States. However, most ED visits (approximately 85%) occur at general (rather than pediatric-specific) EDs.41 We would not generalize these findings to nonpediatric EDs. There may also be differences in patient demographic factors and practice patterns across US regions and Canadian provinces outside Ontario that may limit national generalizations of these findings. We used 2 different data sources with differing quality control and verification processes, which could have introduced misclassification bias in both data sets. We were unable to completely harmonize data collection (eg, race/ethnicity data are not routinely collected in Canada, triage scores were not available in the United States), which limits the ability to compare these cohorts across all relevant variables. There were differences in some baseline demographic factors (eg, neighborhood income, distance from hospital), but these were relatively small compared with the differences in use for some indications. Unfortunately, it was not possible to combine individual-level data across data sets, because the sharing of such data outside of each country was not permitted to conduct adjusted analyses. We were thus limited in ability to assess the appropriateness of imaging at the patient level. While there are situations where imaging is appropriate for the conditions evaluated (eg, atypical presentations), this is likely true in both countries, and we were unable to discern any differences in adverse outcomes between the countries of patients discharged from the pediatric ED without imaging. Additionally, the condition-specific rates of diagnostic imaging relied on discharge diagnosis coding for the ED encounter, rather than chief complaints or reason for visits. Thus, appropriateness of imaging for individual patients cannot be assessed. All analyses were conducted at the level of the ED encounter and patients with multiple ED presentations with the same discharge diagnosis may be at differential risk of having imaging performed. In some cases, the risk may be higher (eg, if undiagnosed symptoms are not resolving), and in other cases, it may be lower (eg, if they present with an exacerbation of a chronic condition). However, we have no reason to believe that multiple ED visits for individual patients differ between countries. Patients with return visits may have also presented at another hospital, so the report of return admissions are likely underestimates. Patients may have also had other consequences of not having imaging performed in the ED, such as return ED visits. The ED returns were not selected as an outcome, because recidivism is not directly associated with disease progression.42 Diagnostic imaging rates may have been underreported owing to bundled charges or billing errors or because some imaging may not be captured (eg, those conducted in the community prior to referral to the pediatric ED). However, the quality-control data suggest that, if anything, imaging was more likely underreported in the United States, which would bias this study toward the null hypothesis. We also did not assess each hospital’s imaging availability (eg, after hours), but the quality-control data did not suggest that there was less access in Ontario than the United States.

Conclusions

In this analysis of visits to pediatric EDs across the United States and Ontario, overall and low-value use of diagnostic imaging is higher in the United States compared with Canada for conditions in which routine use of imaging is not routinely recommended. Lower imaging rates were not associated with increased post-ED adverse outcomes. These findings suggest that there may be an opportunity to safely reduce imaging rates in pediatric EDs in the United States to better align resource use with high-quality care delivery.

eTable 1. Diagnostic imaging codes from the Ontario Health Insurance Plan (OHIP) and Pediatric Health Information System (PHIS)

eTable 2. International Classification of Diseases 9th and 10th versions (ICD9 and ICD10) used in the study.

eTable 3. Rates of imaging and hospital admission wthin 3 days among discharged children without imaging from the ED in 4 children’s hospitals in Ontario, Canada and 26 children’s hospitals in the United States limited to 2016.

eTable 4. Admission and ICU/Surgery/Death within 7 days of ED visit among discharged children without imaging by diagnosis in 4 children’s hospitals in Ontario, Canada and 26 children’s hospitals in the United States, 2006 to 2016.

eTable 5. Hospital admission rates and ICU/surgery/death 3-days and 7-days following ED discharge among all children (with and without imaging) in 4 children’s hospitals in Ontario, Canada and 26 children’s hospitals in the United States, 2006 to 2016.

eTable 6. Rates of imaging among all children and limited to those without complex chronic conditions (CCC) who were discharged from the ED in 4 children’s hospitals in Ontario, Canada and 26 children’s hospitals in the United States, 2006 to 2016.

eTable 7. Sub-analysis: Hospital admission rates and ICU/surgery/death 3-days and 7-days following ED discharge among children without a complex chronic condition (with and without imaging) and outcomes in 4 children’s hospitals in Canada and 26 children’s hospitals in the United States, 2006 to 2016.

eFigure. Diagnostic imaging use among quality control conditions from the emergency department in 4 children’s hospitals in Ontario, Canada and 26 children’s hospitals in the United States, 2006 to 2016.

eReferences.

References

- 1.Mafi JN, Parchman M. Low-value care: an intractable global problem with no quick fix. BMJ Qual Saf. 2018;27(5):333-336. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2017-007477 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Levinson W, Born K, Wolfson D. Choosing wisely campaigns: a work in progress. JAMA. 2018;319(19):1975-1976. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.2202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.American Academy of Pediatrics . Ten things physicians and patients should question. http://www.choosingwisely.org/societies/american-academy-of-pediatrics/. Published February 21, 2013. Accessed February 19, 2019.

- 4.Canadian Association of Emergency Physicians . Ten things physicians and patients should question. https://choosingwiselycanada.org/emergency-medicine/. Published March 2018. Accessed February 19, 2019.

- 5.Li G, Lau JT, McCarthy ML, Schull MJ, Vermeulen M, Kelen GD. Emergency department utilization in the United States and Ontario, Canada. Acad Emerg Med. 2007;14(6):582-584. doi: 10.1197/j.aem.2007.02.030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ivers N, Brown AD, Detsky AS. Lessons from the Canadian experience with single-payer health insurance: just comfortable enough with the status quo. JAMA Intern Med. 2018;178(9):1250-1255. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.3568 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yan SC, Hulou MM, Cote DJ, et al. International defensive medicine in neurosurgery: comparison of Canada, South Africa, and the United States. World Neurosurg. 2016;95:53-61. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2016.07.069 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Emil S, Laberge JM. Canada-trained pediatric surgeons: a cross-border survey of satisfaction and preferences. J Pediatr Surg. 2007;42(5):878-884. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2006.12.054 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Williams JI, Young WA. Summary of studies on the quality of health care administrative databases in Canada. In: Goel V, Williams JI, Anderson GM, Blackstien-Hirsch P, Fooks C, Naylor CD, eds. Patterns of Health Care in Ontario, the ICES Practice Atlas. 2nd ed. Ottawa, Canada: Canadian Medical Association; 1996:339-345. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Canadian Institute for Health Information . National Ambulatory Care Reporting System. https://www.cihi.ca/sites/default/files/document/nacrs_multi-year_info_en.pdf. Published 2012. Accessed February 19, 2019.

- 11.Knapp JF, Hall M, Sharma V. Benchmarks for the emergency department care of children with asthma, bronchiolitis, and croup. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2010;26(5):364-369. doi: 10.1097/PEC.0b013e3181db2262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Feudtner C, Feinstein JA, Zhong W, Hall M, Dai D. Pediatric complex chronic conditions classification system version 2: updated for ICD-10 and complex medical technology dependence and transplantation. BMC Pediatr. 2014;14:199. doi: 10.1186/1471-2431-14-199 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Horner KB, Jones A, Wang L, Winger DG, Marin JR. Variation in advanced imaging for pediatric patients with abdominal pain discharged from the ED. Am J Emerg Med. 2016;34(12):2320-2325. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2016.08.041 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Allie EH, Dingle HE, Johnson WN, et al. ED chest radiography for children with asthma exacerbation is infrequently associated with change of management. Am J Emerg Med. 2018;36(5):769-773. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2017.10.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Quinonez RA, Garber MD, Schroeder AR, et al. Choosing wisely in pediatric hospital medicine: five opportunities for improved healthcare value. J Hosp Med. 2013;8(9):479-485. doi: 10.1002/jhm.2064 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ralston SL, Lieberthal AS, Meissner HC, et al. ; American Academy of Pediatrics . Clinical practice guideline: the diagnosis, management, and prevention of bronchiolitis. Pediatrics. 2014;134(5):e1474-e1502. doi: 10.1542/peds.2014-2742 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Niles LM, Goyal MK, Badolato GM, Chamberlain JM, Cohen JS. US emergency department trends in imaging for pediatric nontraumatic abdominal pain. Pediatrics. 2017;140(4):e20170615. doi: 10.1542/peds.2017-0615 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Reuchlin-Vroklage LM, Bierma-Zeinstra S, Benninga MA, Berger MY. Diagnostic value of abdominal radiography in constipated children: a systematic review. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2005;159(7):671-678. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.159.7.671 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ferguson CC, Gray MP, Diaz M, Boyd KP. Reducing unnecessary imaging for patients with constipation in the pediatric emergency department. Pediatrics. 2017;140(1):e20162290. doi: 10.1542/peds.2016-2290 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tabbers MM, DiLorenzo C, Berger MY, et al. ; European Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition; North American Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology . Evaluation and treatment of functional constipation in infants and children: evidence-based recommendations from ESPGHAN and NASPGHAN. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2014;58(2):258-274. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0000000000000266 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cheng AHY, Campbell S, Chartier LB, et al. Choosing Wisely Canada®: five tests, procedures and treatments to question in Emergency Medicine. CJEM. 2017;19(S2):S9-S17. doi: 10.1017/cem.2017.1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.DeAngelis J, Lou V, Li T, et al. Head CT for minor head injury presenting to the emergency department in the era of choosing wisely. West J Emerg Med. 2017;18(5):821-829. doi: 10.5811/westjem.2017.6.33685 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Subcommittee on Febrile Seizures; American Academy of Pediatrics . Neurodiagnostic evaluation of the child with a simple febrile seizure. Pediatrics. 2011;127(2):389-394. doi: 10.1542/peds.2010-3318 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kimia AA, Ben-Joseph E, Prabhu S, et al. Yield of emergent neuroimaging among children presenting with a first complex febrile seizure. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2012;28(4):316-321. doi: 10.1097/PEC.0b013e31824d8b0b [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lyons TW, Johnson KB, Michelson KA, et al. Yield of emergent neuroimaging in children with new-onset seizure and status epilepticus. Seizure. 2016;35:4-10. doi: 10.1016/j.seizure.2015.12.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sharma S, Riviello JJ, Harper MB, Baskin MN. The role of emergent neuroimaging in children with new-onset afebrile seizures. Pediatrics. 2003;111(1):1-5. doi: 10.1542/peds.111.1.1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chua KP, Schwartz AL, Volerman A, Conti RM, Huang ES. Use of low-value pediatric services among the commercially insured. Pediatrics. 2016;138(6):e20161809. doi: 10.1542/peds.2016-1809 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Papanicolas I, Woskie LR, Jha AK. Health care spending in the united states and other high-income countries. JAMA. 2018;319(10):1024-1039. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.1150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Berdahl CT, Vermeulen MJ, Larson DB, Schull MJ. Emergency department computed tomography utilization in the United States and Canada. Ann Emerg Med. 2013;62(5):486-494.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2013.02.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Woolhandler S, Campbell T, Himmelstein DU. Costs of health care administration in the United States and Canada. N Engl J Med. 2003;349(8):768-775. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa022033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Steiner IP. Emergency medicine practice and training in Canada. CMAJ. 2003;168(12):1549-1550. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bakel LA, Hamid J, Ewusie J, et al. International variation in asthma and bronchiolitis guidelines. Pediatrics. 2017;140(5):e20170092. doi: 10.1542/peds.2017-0092 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gong C, Byczkowski T, McAneney C, Goyal MK, Florin TA. Emergency department management of bronchiolitis in the United States. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2017. doi: 10.1097/PEC.0000000000001145 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hudgins JD, Neuman MI, Monuteaux MC, Porter J, Nelson KA. Provision of guideline-based pediatric asthma care in us emergency departments. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2019. doi: 10.1097/PEC.0000000000001706 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Studdert DM, Mello MM, Sage WM, et al. Defensive medicine among high-risk specialist physicians in a volatile malpractice environment. JAMA. 2005;293(21):2609-2617. doi: 10.1001/jama.293.21.2609 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wong AC, Kowalenko T, Roahen-Harrison S, Smith B, Maio RF, Stanley RM. A survey of emergency physicians’ fear of malpractice and its association with the decision to order computed tomography scans for children with minor head trauma. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2011;27(3):182-185. doi: 10.1097/PEC.0b013e31820d64f7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gallagher TH, Waterman AD, Garbutt JM, et al. US and Canadian physicians’ attitudes and experiences regarding disclosing errors to patients. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166(15):1605-1611. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.15.1605 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Brenner DJ, Hall EJ. Computed tomography—an increasing source of radiation exposure. N Engl J Med. 2007;357(22):2277-2284. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra072149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kuppermann N, Holmes JF, Dayan PS, et al. ; Pediatric Emergency Care Applied Research Network (PECARN) . Identification of children at very low risk of clinically-important brain injuries after head trauma: a prospective cohort study. Lancet. 2009;374(9696):1160-1170. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61558-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Blackwell CD, Gorelick M, Holmes JF, Bandyopadhyay S, Kuppermann N. Pediatric head trauma: changes in use of computed tomography in emergency departments in the United States over time. Ann Emerg Med. 2007;49(3):320-324. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2006.09.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bourgeois FT, Shannon MW. Emergency care for children in pediatric and general emergency departments. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2007;23(2):94-102. doi: 10.1097/PEC.0b013e3180302c22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Health Quality Ontario . The emergency department return visit quality program: report on the 2017 results. https://www.hqontario.ca/Portals/0/documents/qi/ed/report-ed-return-visit-program-2017-en.pdf. Published 2018. Accessed February 19, 2019.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eTable 1. Diagnostic imaging codes from the Ontario Health Insurance Plan (OHIP) and Pediatric Health Information System (PHIS)

eTable 2. International Classification of Diseases 9th and 10th versions (ICD9 and ICD10) used in the study.

eTable 3. Rates of imaging and hospital admission wthin 3 days among discharged children without imaging from the ED in 4 children’s hospitals in Ontario, Canada and 26 children’s hospitals in the United States limited to 2016.

eTable 4. Admission and ICU/Surgery/Death within 7 days of ED visit among discharged children without imaging by diagnosis in 4 children’s hospitals in Ontario, Canada and 26 children’s hospitals in the United States, 2006 to 2016.

eTable 5. Hospital admission rates and ICU/surgery/death 3-days and 7-days following ED discharge among all children (with and without imaging) in 4 children’s hospitals in Ontario, Canada and 26 children’s hospitals in the United States, 2006 to 2016.

eTable 6. Rates of imaging among all children and limited to those without complex chronic conditions (CCC) who were discharged from the ED in 4 children’s hospitals in Ontario, Canada and 26 children’s hospitals in the United States, 2006 to 2016.

eTable 7. Sub-analysis: Hospital admission rates and ICU/surgery/death 3-days and 7-days following ED discharge among children without a complex chronic condition (with and without imaging) and outcomes in 4 children’s hospitals in Canada and 26 children’s hospitals in the United States, 2006 to 2016.

eFigure. Diagnostic imaging use among quality control conditions from the emergency department in 4 children’s hospitals in Ontario, Canada and 26 children’s hospitals in the United States, 2006 to 2016.

eReferences.