Key Points

Question

Was the release of the Netflix show 13 Reasons Why associated with excess suicides in the United States?

Findings

In this time series analysis of monthly suicide data from 1999 to 2017, an immediate increase in suicides beyond the generally increasing trend was observed among the target audience of 10- to 19-year-old individuals in the 3 months after the show’s release. Age- and sex-specific models indicated that the association with suicide mortality was restricted to 10- to 19-year-old individuals, and proportional increases were stronger in females.

Meaning

The increase in suicides in only the youth population and the signal of a potentially larger proportional increase in young females all appeared to be consistent with media contagion and seem to reinforce the need for safer and more thoughtful portrayal of suicide in the media.

Abstract

Importance

On March 31, 2017, Netflix released the show 13 Reasons Why, sparking immediate criticism from suicide prevention organizations for not following media recommendations for responsible suicide portrayal and for possible suicide contagion by media. To date, little research has been conducted into the associations between the show and suicide counts among its young target audience.

Objective

To analyze the changes in suicide counts after the release of 13 Reasons Why.

Design, Setting, and Participants

For this time series analysis, monthly suicide data for the age groups 10 to 19 years, 20 to 29 years, and 30 years or older for both US males and females from January 1, 1999, to December 31, 2017, were extracted from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s WONDER (Wide-ranging Online Data for Epidemiologic Research) database. Twitter and Instagram posts were used as a proxy to estimate the amount of attention the show received through social media from April 1, 2017, to June 30, 2017. Autoregressive integrated moving average time series models were fitted to the pre–April 2017 period to estimate suicides among the age groups and to identify changes in specific suicide methods used. The models were fitted to the full time series with dummy variables for (1) April 2017 and (2) April 1, 2017, to June 30, 2017. Data were analyzed in December 2018 and January 2019.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Suicide data before and after the release of the show in 2017.

Results

Based on social media data, public interest in the show was highest in April 2017 and was negligible after June 2017. For 10- to 19-year-old males and females, increases in the observed values from April to June 2017 were outside the 95% confidence bands of forecasts. Models testing 3-month associated suicide mortality indicated 66 (95% CI, 16.3-115.7) excess suicides among males (12.4% increase; 95% CI, 3.1%-21.8%) and 37 (95% CI, 12.4-61.5) among females (21.7% increase; 95% CI, 7.3%-36.2%). No excess suicide mortality was seen in other age groups. The increase in the hanging suicide method was particularly high (26.9% increase; 95% CI, 15.3%-38.4%).

Conclusions and Relevance

Caution must be taken in interpreting these findings; however, the suicide increase in youth only and the signal of a potentially larger increase in young females all appear to be consistent with a contagion by media and seem to reinforce the need for collaboration toward improving fictional portrayals of suicide.

This study analyzes nearly 20 years of suicide data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, as well as specific Twitter and Instagram posts, to estimate incidence of suicide among children and teenagers exposed to the suicide theme and depiction in the Netflix show 13 Reasons Why.

Introduction

On March 31, 2017, Netflix released its 13-part show 13 Reasons Why. The show describes the events leading up to and the aftermath of the suicide of a character, 17-year-old Hannah Baker, who left her personal story and reasons for her suicide on audiotapes. The tapes are directed at specific people, explaining their roles in Hannah’s death, and each of the tapes provides the context for an episode. The show was one of the most watched shows in 2017, generating more than 11 million Tweets within 3 weeks of its release alone.1,2 It also sparked immediate criticism from mental health and suicide prevention organizations for not following recommendations on responsible media portrayal of suicide.3 In particular, concerns were raised that the graphic depiction of Hannah cutting her wrists in the bathtub, and the implication that seeking help for suicidal thoughts is futile, might trigger imitation acts and additional suicides.3

Little evaluation has been conducted of the consequences of 13 Reasons Why, largely owing to the lags in availability of suicide data. In general, fictional portrayals of suicide have not been found to be consistently associated with suicides. Specifically, a recent meta-analysis of studies did not support contagion by fictional media.4 However, the conclusion in that meta-analysis appeared to be too strong, given that some studies do suggest that entertainment media can be a factor in subsequent suicides.5,6,7

The 7 published studies and reports into 13 Reasons Why focused on suicide attempts, suicidal ideation, and some other outcomes and had mixed results.8,9,10,11,12,13,14 They generally suggested that the show placed vulnerable members of the audience at excess risk.8,9,10,11,12,13 In particular, the show appeared to be associated with increased hospitalizations for suicide attempts and self-harm.8 By contrast, a study commissioned by Netflix suggested that the show was associated with improvements in empathy toward others in some segments of the audience who were potentially struggling with depression.14

An overview of all 6 available studies that present quantitative findings is provided in Table 1. Any observational study examining the potential associated effects of a suicide depiction, such as in 13 Reasons Why, across a population carries a substantial risk of confounding. Nevertheless, efforts to describe the associations between exposures (such as the show) and health outcomes in different regions are important because consistent findings across studies may help to clarify if the associations may be causal.

Table 1. Studies of Exposure to 13 Reasons Why.

| Source | Sample Size | Sample Source | Study Design | Dependent Variable | Negative Outcome | Positive Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cooper et al,8 2018 | 775 | 2002-2017 Suicidal pediatric admissions; Oklahoma City, Oklahoma, United States | Ecological study of suicide attempt admissions in children’s hospital before and after the release of the show | Suicide-oriented admissions, ED | Admissions increased after watching the show | None |

| Rosa et al,9 2019 | 7004 | 84% Female, Facebook; Brazil | Cross-sectional study among exposed adolescents; retrospective self-reports on changes in mood | Changes in mood | 23.7% Reported worsening in mood after watching the show | 32.1% Reported improvement in mood after watching the show |

| Feuer and Havens,10 2017 | NA | Data from 14 sites on a hospital-based listserv; United States | Survey among pediatric emergency services on increases in admission volume before and after the release of the show | Suicide attempt or gesture related to the show | 40% Of sites reported at least 1 case with imitation gestures or attempts within 30 d of watching the show | None |

| Hong et al,11 2019 | 87 | Suicidal patients, ED; 49% exposed to the show; United States | Cross-sectional study among parent-youth dyads during ED visit; retrospective self-reports on suicide risk and identification with main character of the show | Self-reported increase in suicide risk | 51% Of those exposed reported increase in SR; persons who identified with main female character and persons with history of suicidality were at even higher SR | None |

| Zimerman et al,12 2018 | 21 062 | Facebook sample; persons who liked the show, predominately Brazilians (80.1%) and Americans (19.9%) | Surveys on bullying, depression, and SI among adolescents before and after exposure to the show | Self-reported SI, depression, and bullying behavior before and after watching the show | Of individuals with preexisting SI, 16.5% reported more SI after watching the show | Of individuals with preexisting SI, 59.2% reported less SI after watching the show; of adolescents who had engaged in bullying, 90.1% engaged in less bullying after watching the show |

| Lauricella et al,14 2018 | 1880 Parents; 1722 adolescents; 1798 young adults | Survey in 4 world regions | Cross-sectional study among adolescents, young adults, and parents; retrospective self-reports on experiences with and attitudes toward the show | Experiences with and attitudes toward the show | No suicide-related outcomes reported | Several positive outcomes, including 63%-79% of adolescents who reported watching the show was positive for them |

Abbreviations: ED, emergency department; NA, not applicable; SI, suicidal ideation; SR, suicide risk.

The current study is crucial to that effort as it overcomes the limitations of previous studies by explicitly examining the association between the release of 13 Reasons Why and actual suicides and doing so in the country (United States) in which the show takes place. Observers have called for nationwide analyses of death data given the widespread belief that 13 Reasons Why could trigger suicides in the vulnerable younger population.3,15,16 Such studies had not been possible until the recent release of 2017 suicide data by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Methods

No protocol approval was needed for this study in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.17 The data used were deidentified mortality data obtained from a secondary source.

Viewership Over Time

Viewership data for 13 Reasons Why can strengthen models of the show’s possible associated effects; however, Netflix does not publicly share statistics that would allow a direct measurement of the viewership of 13 Reasons Why in the United States.18 However, it is possible to use a proxy to estimate the amount of attention the show received through social media, namely Twitter and Instagram, which are 2 of the most popular platforms frequented by US adolescents. In particular, 72% of US adolescents aged 13 to 17 years reported using Instagram.19

In January 2019, we used the advanced search interface on Twitter to retrieve original Tweets in the English language that contain references to the show or its main characters. Our search terms were 13RW, 13 Reasons Why, Thirteen Reasons Why, Hannah Baker, and Clay Jensen. This search allowed us to generate an exhaustive data set with all mentions of the show, excluding Tweets produced by accounts that Twitter considered malicious bots, up to the retrieval date. This method was used to gather 1 416 175 Tweets, generated by 870 056 users, for the period April 1, 2017, to June 30, 2017.

To measure the attention received on Instagram, we used data from InfluencerDB, a company that owns a database that includes an exhaustive record of metadata of media posted on Instagram by influencers (ie, users with at least 15 000 followers). We processed the data for April to June 2017, selecting content with mentions of the show similar to those on Twitter. We further filtered non-English content with the textcat R package (R Foundation for Statistical Computing), yielding a data set of 26 322 Instagram posts produced by 7875 influencers.

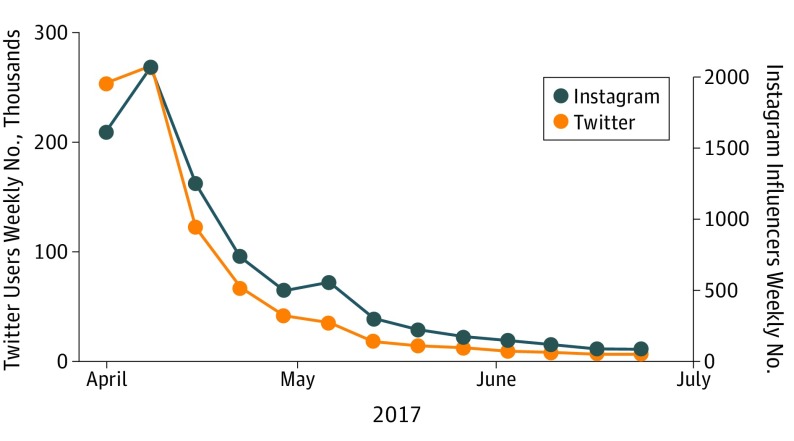

Figure 1 shows the weekly number of Twitter users and Instagram influencers who posted about 13 Reasons Why for the first time between April 1, 2017, and June 30, 2017. Social media attention peaked in April, in which 84% of initial Tweets and 74% of initial Instagram posts about the show occurred. This general trend is supported by Netflix, which reported that the show was the third most binge-watched on Netflix in 2017.20 Thus, this analysis considered the exposure to the show to be sudden during April 2017. Because of the absence of social media attention after June 2017, we defined the exposure window as April to June.

Figure 1. Public Interest in 13 Reasons Why From Twitter Users and Instagram Influencers, April to June 2017.

The show earned the most attention on social media in April 2017, when 84% of Twitter users and 74% of Instagram influencers posted about the show for the first time within the period analyzed.

Suicide Data and Statistical Analysis

We downloaded monthly suicide data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention WONDER (Wide-ranging Online Data for Epidemiologic Research) system21 for the period January 1, 1999, to December 31, 2017. Suicide data were extracted for the age groups 10 to 19 years (the main target audience for 13 Reasons Why), 20 to 29 years, and 30 years or older for both males and females. Identification with the life circumstances of a high school student like Hannah Baker and related issues such as school bullying were expected to be most prominent among individuals aged 10 to 19 years. Therefore, the prespecified hypothesis of this study was that any potential associated effects of 13 Reasons Why would be most pronounced in the 10- to 19-year age group. Similarly, we expected the consequences to be stronger in females, owing to the show’s focus on Hannah’s suicide. We also extracted data on suicide methods for the 10-to 19-year age group, including cutting (the method of suicide used by Hannah), hanging, and shooting with firearms.

Time series models were fitted to the data, according to the analysis of the pre–April 2017 period. For the selection of models, we used SPSS Expert Modeler function, version 25 (IBM), to choose the model with the lowest Bayesian information criterion value, highest stationary R2 value (the variance accounted for by the fitted time series model), and a not significant Ljung-Box Q statistic (indicating whether residuals could be assumed white noise, with stated df). The models were subsequently fitted to the full time series. On the basis of social media data shown in Figure 1, we investigated a temporary association of the release of 13 Reasons Why with suicides (1) for April 2017, which was consistent with the period of strong interest in the show, and (2) for April to June 2017, which included the total period with some indication of public interest in the show. We used dummy variables to model these associations as discrete pulses and calculated the number of excess suicides for each model. Two-sided tests of significance were performed. P < .05 was considered significant.

Results

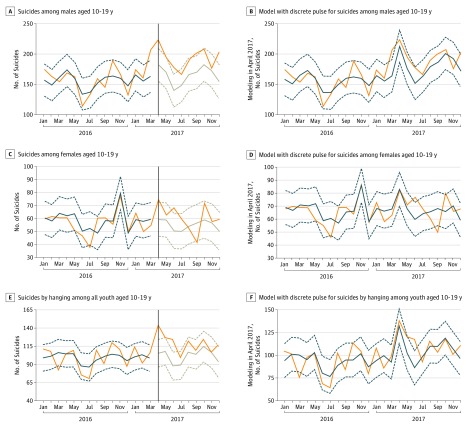

Observed suicides from April to June 2017 exceeded the 95% CIs of model forecasts fitted to pre–April 2017 data for 10- to 19-year-old males and females (Figure 2B, D). This observation was also true for the suicide method of hanging in this age group (Figure 2F).

Figure 2. Youth Suicides in the United States, January 2016 to December 2017.

Orange lines indicate observed values; dark blue lines, model-fitted values; solid tan lines, model-based forecasts; dashed dark blue lines to the left of the vertical line and dashed tan lines to the right of the vertical line, 95% confidence bands of the fitted values and forecasts. Panels A and B show suicides among males; panels C and D, suicides among females; and panels E and F, suicides by hanging. The panels on the left show that increases in the observed values from April to June 2017 are outside the 95% confidence bands of the forecasts of models that were fitted to the pre–April 2017 data only. The panels on the right show the effect of modeling the April 2017 increase with a discrete pulse in the full data.

Models including a discrete pulse for April (Figure 2B, D, and F) indicated 38.2 (95% CI, 10.5-65.9) excess suicides among 10- to 19-year-old individuals of both sexes (14.6% increase; 95% CI, 4.0%-25.3%). Gender-specific models indicated 27.9 (95% CI, 2.3-53.5) excess suicides among males (14.2% increase; 95% CI, 1.2%-27.3%) and 16 (95% CI, 3.5-28.4) excess suicides among females (27.1% increase; 95% CI, 6.0%-48.2%).

Models testing discrete pulses from April to June 2017 indicated 94.4 (95% CI, 39.3-149.6) excess suicides among 10- to 19-year-old individuals in the 3-month period after the show’s release, corresponding to an increase of 13.3% (95% CI, 5.5%-21.1%) when compared with the expected number of suicides. For 10- to 19-year-old males, the model indicated 66 (95% CI, 16.3-115.7) excess suicides (12.4% increase; 95% CI, 3.1%-21.8%). Among females, 37 (95% CI, 12.4-61.5) excess suicides were estimated (21.7% increase; 95% CI, 7.3%-36.2%). No associated differences in suicide mortality were seen in the 20- to 29-year and the 30-year-or-older age groups (Table 2).

Table 2. Fitted Models and Excess Number of Suicides, April 2017 and April to June 2017.

| Time Series | Best-Fitting Time Series Model Before April 2017a | Stationary R2 | Ljung-Box Q Statistic (df) | Estimated Excess No. (SE) of Suicidesb | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| April 2017 Only | % Increase (SE), No. | April-June 2017 | % Increase (SE), No. | ||||

| 10-19 y Age group | |||||||

| All | ARIMA(0,1,1)(0,1,1) | 0.583 | 7.85 (16) | 38.16 (14.13)c | 14.63 (5.42)c | 94.41 (28.14)d | 13.30 (3.97)d |

| Male sex | ARIMA(0,1,1)(0,1,1) | 0.595 | 8.01 (16) | 27.90 (13.04)e | 14.23 (6.65)e | 66.03 (25.35)c | 12.44 (4.77)c |

| Female sex | ARIMA(1,1,2)(0,1,1) | 0.661 | 17.75 (15) | 15.98 (6.35)e | 27.08 (10.76)e | 36.96 (12.51)c | 21.74 (7.36)c |

| Shooting with firearm suicide method, all | ARIMA(0,1,1)(0,1,1) | 0.625 | 18.18 (16) | 2.82 (9.04) | 2.39 (7.65) | 6.48 (17.22) | 2.07 (5.49) |

| Hanging suicide method, all | ARIMA(0,1,2)(0,1,1) | 0.545 | 18.68 (15) | 34.72 (9.17)d | 33.62 (8.88)d | 79.83 (17.49)d | 28.86 (5.89)d |

| Male individuals | |||||||

| 20-29 y age group | ARIMA(0,1,1)(0,1,1) | 0.630 | 25.88 (16) | −21.10 (23.60) | −3.96 (4.43) | 49.41 (45.00) | 3.10 (2.82) |

| ≥30+ y age group | ARIMA(0,1,1)(0,1,1) | 0.655 | 17.58 (16) | 9.52 (60.67) | 0.41 (2.59) | 211.35 (118.05) | 2.97 (1.66) |

| Female individuals | |||||||

| 20-29 y age group | ARIMA(0,1,1)(0,1,1) | 0.681 | 15.34 (16) | 0.59 (9.80) | 0.50 (8.35) | 25.29 (17.85) | 7.17 (5.06) |

| ≥30+ y age group | ARIMA(0,1,1)(0,1,1) | 0.615 | 19.07 (16) | −6.66 (27.59) | −0.96 (3.97) | 38.76 (53.28) | 1.84 (2.54) |

Abbreviation: ARIMA, autoregressive integrated moving average.

The pre–April 2017 data were checked for innovative and additive outliers, which were integrated into the models when necessary. ARIMA(p,d,q)(P,D,Q) time series model, where P = number of time lags, which affect current values autoregressively; d = number of times past values were subtracted from current values to reduce nonstationarity in the time series; and q = number of current and past random noise terms, which affect current values. P, D, and Q are the respective parameters of a seasonal ARIMA model with a periodicity of 12.

Numbers indicate associations of 13 Reasons Why with suicide rates in the respective period.

P < .01.

P < .001.

P < .05.

With regard to suicide methods, cutting (the method portrayed in the show) was rare, with typically no more than 2 cases per month among individuals in the 10- to 19-year age group. Because of the low number of suicides by cutting, these data were not amenable to time series analysis. Increases in suicide by hanging were found. The model testing a discrete pulse in April 2017 indicated 34.7 (95% CI, 16.8-52.7) excess suicides by hanging (33.6% increase; 95% CI, 16.2%-51.0%) in the month with the highest volume of public attention to the show. The model testing 3-month associated suicide mortality estimated 79.8 (95% CI, 45.6-114.1) excess suicides by hanging (26.9% increase; 95% CI, 15.3%-38.4%). No associations were seen for suicide by firearm.

Robustness Analysis

The skewness of the time series data ranged from 0.33 (females ≥30 years) to 1.11 (all 10- to 19-year-olds; males 10-19 years of age). When a square root transformation was applied to reduce the possible consequence of nonnormality, all associations reported in Table 2 retained statistical significance, except for the 1-month period of April 2017, among the 10- to 19-year-old males and females, which only closely missed nominal significance. The specific parameter estimates (with SEs; all on a square root scale) of discrete pulses were as follows: All aged 10 to 19 years 1-month estimate, 1.08 (0.54; P = .045), and 3-month estimate, 3.01 (1.10; P = .007); males aged 10 to 19 years 1-month estimate, 0.91 (0.56; P = .11), and 3-month estimate, 2.48 (1.09; P = .02); females aged 10 to 19 years 1-month estimate, 0.86 (0.53; P = .10), and 3-month estimate, 2.24 (1.04; P = .03); hanging among all youths aged 10 to 19 years 1-month estimate, 1.13 (0.52; P = .03), and 3-month estimate, 4.05 (1.55; P = .01).

Discussion

To our knowledge, this study is the first to investigate the association between 13 Reasons Why and suicides in the United States. Although these results must be interpreted with substantial caution, they do identify a rise in youth suicides above and beyond the generally increasing trend in the country.22 This increase was concurrent with the period of strongest interest in the show, as reflected by Instagram and Twitter data, and occurred only in the age group targeted by the show. Time series modeling from April to June 2017 suggested the magnitude of increase was 13.3% in those aged 10 to 19 years, which would be meaningful from a clinical and public health standpoint at any value within its 95% CI (5.5%-21.1%).

Ecological studies have inherent limitations; however, we believe this method is the best available to answer the research question posed here. A detailed examination of the findings may help to clarify the degree of confidence with which to conclude that the association between 13 Reasons Why and increased suicides is causal. The immediate increase in suicides after the release of 13 Reasons Why among this age group is consistent with the prespecified expectation. Studies on how people self-select for online content strengthen the argument that most viewings of the show (and therefore potentially harmful exposures) occurred in April 2017, when attention on social media was greatest.23 Previous research on suicide contagion subsequent to fictional media portrayals has generally found that the associations were strongest in the first month after public release.5,6 However, 13 Reasons Why was a media phenomenon, which remains available on Netflix, that generated unusually intense press interest for months and was expected to have implications beyond the first month. As indicated by social media data, the associations might have been present for at least 3 months, until June 2017, when social media interest in the show was reduced. Therefore, the timing of the observed associations is consistent with possible contagion by media.

With regard to the specificity of these associations, young people were the clear target demographic of 13 Reasons Why, which portrayed issues such as bullying at schools and life problems in adolescence. Increases in suicide were seen only in this age group with no associations observed for individuals aged 20 to 29 years and 30 years or older, and this finding is potentially consistent with contagion by media.

Potentially greater proportional increases in suicides among females were noted. Previous research indicated that contagion by media most likely (but not exclusively) occurs among individuals of the same sex and age as fictional characters who die by suicide.5 There is no expectation that this association would be exclusive to females, given that some of the life problems presented as causes of Hannah’s suicide and discussed in the show (eg, bullying) similarly adversely affect both female and male adolescents.24 The increase in male suicide may, in part, reflect that suicide deaths are more prevalent in male adolescents, whereas females have higher rates of suicide attempts, which were not analyzed in this study.25

Hanging stood out as the method associated with increased suicides among 10- to 19-year-old individuals in the months after the release of 13 Reasons Why. If the association were causal, the inference may be that suicide increases should occur by cutting (the suicide method depicted in the show) rather than hanging. However, cutting is a method with generally low lethality and may be more likely to rise in suicide attempt rather than suicide death data. Research indicates that cutting has the lowest case fatality rate among suicide methods.26 In contrast, hanging is one of the most lethal methods,26 and the availability of hanging is high. Furthermore, research conducted immediately after the release of 13 Reasons Why indicated that web searches for suicide methods and queries on how to kill oneself increased immediately after the release of the show in the United States.1 Hannah’s controversial suicide scene was discussed on social media, and the discussions highlighted that the method was difficult to carry out.27

Taken together, the findings may reflect a form of selection bias, highlighting only the increases in the most common method of suicide death in adolescents but offering no information on changes in low-lethality methods that would have been present in suicide attempt data. In support of this conjecture, public mass media that speculated on the potential association between youth suicides and the show repeatedly reported about teens who died by hanging in the aftermath of the release of the show.28,29,30

Implications for Suicide Prevention

This study does not provide definitive proof that 13 Reasons Why is associated with harmful outcomes, but the findings are sufficiently concerning so as to warrant greater care and attention by Netflix and other entertainment producers. These findings support the urgent necessity for active engagement between those in the entertainment industry and mental health and suicide prevention experts to minimize or avoid potentially harmful suicide portrayals. In particular, media recommendations for responsible reporting of suicide in the news are readily available,31,32 but few resources are provided for those who create content in the entertainment industry.33,34 National recommendations for depicting suicide with a specific focus on the entertainment industry were recently released by the National Action Alliance for Suicide Prevention.35 Strong collaborations between different sectors could result in on-screen portrayals that not only do no harm but also act as a force for good in suicide prevention.

Strengths and Limitations

A strength of this study was the length of the time series analysis data set: It used monthly data of 19 years to estimate expected suicide counts. Time series models can produce accurate estimates without measuring exogenous variables, and they control for issues such as autocorrelation and seasonal changes in suicide. The structural characteristics of the time series, including trends, temporal fluctuations, and seasonality (eg, known spring peaks in adolescent suicides) were adequately adjusted for in autoregressive integrated moving average time series models, as applied here.

The main limitation of the study was that it was based on ecological data. Thus, it was not possible to ascertain whether the excess suicide decedents had actually watched 13 Reasons Why. Furthermore, viewership data of the show were not available, and therefore the timing of exposure was modeled only through the proxy of interest on social media. The ecological nature of the study also meant that this study could identify only associations and not causation. Many factors are associated with suicide across any population, let alone a country the size of the United States. The wide CIs of the time series analyses underscore this point. The models could not account for other suicide-related media events that occurred during the study period that might have affected suicide counts. For example, on April 28, 2017, the rapper Logic released his song 1-800-273-8255, which shared the telephone number for the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline. The release was followed by the second-highest call volume in the history of the service, and overall calls to the hotline rose approximately 33% over the corresponding time in 2016.36 This outcome might have helped mitigate any harmful consequences of 13 Reasons Why. Furthermore, mental health and suicide prevention organizations shared material for educating teachers, adolescents, clinicians, and parents about how to discuss the show in schools,3 and Netflix added content warnings to the show in May 2017.37

Although it is impossible to account for all potential confounding variables, it is notable that the timing, specificity, and magnitude of the associations observed here are all consistent with a potential contagion by media. This finding would be strengthened by other well-designed studies in other countries with high Netflix viewership. Because it was not possible to do a randomized clinical trial of 13 Reasons Why to examine outcomes such as suicide, for practical and ethical reasons, ecological studies like the present study (in which it is unknown whether those who died from suicide actually watched the show) or individual-level studies that use an alternative outcome to suicide will remain necessary in informing researchers and policymakers.

Conclusions

To our knowledge, this study is the first to examine the associations between suicides and the release of 13 Reasons Why in the United States. The associations identified here must be interpreted with a substantial degree of caution, but they do appear to demonstrate an increase in suicides that is consistent with potential contagion by media. Specifically, excess suicides of approximately 15% occurred in the first month after the show’s release in the main target group, 10- to 19-year-old individuals. Significant associations were present for all of the 3 months in which the show was discussed on social media. Our findings appear to point to the need of engagement by public health and suicide experts to engage with members of the entertainment industry to prevent further harmful suicide portrayals.

References

- 1.Ayers JW, Althouse BM, Leas EC, Dredze M, Allem JP. Internet searches for suicide following the release of 13 Reasons Why. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(10):1527-1529. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.3333 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Variety. 13 Reasons Why renewed for a second season at Netflix. 2017. http://variety.com/2017/tv/news/13-reasons-why-renewed-season-2-netflix-2-1202411389. Accessed November 8, 2017.

- 3.Arendt F, Scherr S, Till B, Prinzellner Y, Hines K, Niederkrotenthaler T. Suicide on TV: minimising the risk to vulnerable viewers. BMJ. 2017;358:j3876. doi: 10.1136/bmj.j3876 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ferguson CJ. 13 Reasons Why not: a methodological and meta-analytic review of evidence regarding suicide contagion by fictional media [published online October 14, 2018]. Suicide Life Threat Behav. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schmidtke A, Häfner H. The Werther effect after television films: new evidence for an old hypothesis. Psychol Med. 1988;18(3):665-676. doi: 10.1017/S0033291700008345 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Niederkrotenthaler T, Stack S, eds. Media and Suicide: International Perspectives on Research, Theory, and Policy. Abingdon, UK: Routledge; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pirkis J, Blood RW. Suicide and the media: part II: portrayal in fictional media. Crisis. 2001;22(4):155-162. doi: 10.1027//0227-5910.22.4.155 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cooper MT Jr, Bard D, Wallace R, Gillaspy S, Deleon S. Suicide attempt admissions from a single children’s hospital before and after the introduction of Netflix series 13 Reasons Why. J Adolesc Health. 2018;63(6):688-693. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2018.08.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rosa GSD, Andrades GS, Caye A, Hidalgo MP, Oliveira MAB, Pilz LK. Thirteen Reasons Why: the impact of suicide portrayal on adolescents’ mental health. J Psychiatr Res. 2019;108:2-6. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2018.10.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Feuer V, Havens J. Teen suicide: fanning the flames of a public health crisis. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2017;56(9):723-724. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2017.07.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hong V, Ewell Foster CJ, Magness CS, McGuire TC, Smith PK, King CA. 13 Reasons Why: viewing patterns and perceived impact among youths at risk of suicide. Psychiatr Serv. 2019;70(2):107-114. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201800384 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zimerman A, Caye A, Zimerman A, Salum GA, Passos IC, Kieling C. Revisiting the Werther effect in the 21st century: bullying and suicidality among adolescents who watched 13 Reasons Why. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2018;57(8):610-613.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2018.02.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Till B, Vesely C, Mairhofer D, Braun M, Niederkrotenthaler T. Reports of adolescent psychiatric outpatients on the impact of the TV series “13 Reasons Why”: a qualitative study. J Adolesc Health. 2019;64(3):414-415. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2018.11.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lauricella AR, Cingel DP, Wartella E. Exploring How Teens and Parents Responded to 13 Reasons Why: United States. Evanston, IL: Center on Media and Human Development, Northwestern University; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 15.O’Brien KHM, Knight JR, Harris SK. A call for social responsibility and suicide risk screening, prevention, and early intervention following the release of the Netflix series 13 Reasons Why. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(10):1418-1419. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.3388 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Quinn SM, Ford CA. Why we should worry about “13 Reasons Why.” J Adolesc Health. 2018;63(6):663-664. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2018.09.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.World Medical Association World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki: ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. JAMA. 2013;310(20):2191-2194. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.281053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.The New York Times Netflix’s opaque disruption annoys rivals on TV. https://www.nytimes.com/2016/01/18/business/media/disruption-by-netflix-irks-tv-foes.html. Published January 17, 2016. Accessed January 17, 2019.

- 19.Pew Research Center Teens, Social Media & Technology 2018. http://www.pewinternet.org/2018/05/31/teens-social-media-technology-2018/. Published May 31, 2018. Accessed January 18, 2019.

- 20.Netflix Media Center A year in bingeing. 2017. https://media.netflix.com/en/press-releases/2017-on-netflix-a-year-in-bingeing. Published December 11, 2017. Accessed January 22, 2018.

- 21.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention CDC WONDER. About underlying cause of death, 1999-2017. http://wonder.cdc.gov/ucd-icd10.html. Accessed December 29, 2018.

- 22.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Suicide mortality in the United States 1999-2017. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/products/databriefs/db330.htm. Accessed December 29, 2018.

- 23.Li X, Hitt LM. Self-selection and information role of online product reviews. Inf Syst Res. 2008;19:456-474. doi: 10.1287/isre.1070.0154 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.DeSisto MC, Smith S. Bullying prevention in schools: position statement. NASN Sch Nurse. 2015;30(3):189-191. doi: 10.1177/1942602X14563683 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cash SJ, Bridge JA. Epidemiology of youth suicide and suicidal behavior. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2009;21(5):613-619. doi: 10.1097/MOP.0b013e32833063e1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Spicer RS, Miller TR. Suicide acts in 8 states: incidence and case fatality rates by demographics and method. Am J Public Health. 2000;90(12):1885-1891. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.90.12.1885 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Reddit. Was Hannah’s suicide scene realistic? https://www.reddit.com/r/13ReasonsWhy/comments/651ygw/was_hannahs_suicide_scene_realistic_spoilers/. Posted 2017. Accessed January 17, 2019.

- 28.KTVU Two families endure suicides, blame popular Netflix show. http://www.ktvu.com/news/2-families-endure-suicides-blame-popular-netflix-show. Published June 22, 2017. Accessed January 17, 2019.

- 29.AJC Families who blame Netflix series '13 Reasons Why' for teen suicides want show cancelled. 2017. https://www.ajc.com/blog/talk-town/families-who-blame-netflix-series-reasons-why-for-teen-suicides-want-show-cancelled/iTbcPmhwdZRX1yEoiMyxNN/. Published June 28, 2017. Accessed January 17, 2019.

- 30.The Sun. Netflix suicide: schoolgirl, 13, hangs herself after mimicking it for prank video linked to Netflix suicide show 13 Reasons Why. https://www.thesun.co.uk/news/5761450/girl-suicide-netflix-13-reasons-why/. Published March 8, 2018. Accessed January 17, 2019.

- 31.World Health Organization Preventing Suicide. A Resource for Media Professionals: Update 2017. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mindframe. Reporting suicide and mental Illness: a Mindframe resource for media professionals. http://www.mindframe-media.info/__data/assets/pdf_file/0011/9983/Mindframe-for-media-book.pdf. Accessed December 29, 2018.

- 33.Samaritans. Media guidelines: factsheet drama portrayals. https://www.samaritans.org/sites/default/files/kcfinder/files/press/Samaritans%20media%20factsheet%20-%20drama%20portrayal.pdf. Accessed December 29, 2018.

- 34.Mindframe. Mental illness and suicide. A Mindframe resource for stage and screen. http://www.mindframe-media.info/__data/assets/pdf_file/0014/6017/Stage-and-Screen-Resource-Book.pdf. Accessed November 29, 2018.

- 35.National Action Alliance for Suicide Prevention National recommendations for depicting suicide. http://www.suicideinscripts.org. Accessed March 13, 2019.

- 36.CNN Calls to suicide prevention hotline spike after VMA performance. 2017. https://edition.cnn.com/2017/08/25/health/logic-suicide-hotline-vma-18002738255/index.html. Published August 29, 2017. Accessed December 29, 2018.

- 37.Variety. Netflix pledges to add more trigger warnings to ‘13 Reasons Why.’ https://variety.com/2017/digital/news/13-reasons-why-trigger-warnings-netflix-1202404969/.Published May 1, 2017. Accessed December 29, 2018.