Abstract

Growing evidences suggest that stroke is a systemic disease affecting many organ systems beyond the brain. Stroke-related systemic inflammatory response and immune dysregulations may play an important role in brain injury, recovery, and stroke outcome. The two main phenomena in stroke-related peripheral immune dysregulations are systemic inflammation and post-stroke immunosuppression. There is emerging evidence suggesting that the spleen contracts following ischemic stroke, activates peripheral immune response and this may further potentiate brain injury. Whether similar brain–immune crosstalk occurs in hemorrhagic strokes such as intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH) and subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH) is not established. In this review, we systematically examined animal and human evidence to date on peripheral immune responses associated with hemorrhagic strokes. Specifically, we reviewed the impact of clinical systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS), inflammation- and immune-associated biomarkers, the brain–spleen interaction, and cellular mediators of peripheral immune responses to ICH and SAH including regulatory T cells (Tregs). While there is growing data suggesting that peripheral immune dysregulation following hemorrhagic strokes may be important in brain injury pathogenesis and outcome, details of this brain-immune system cross-talk remain insufficiently understood. This is an important unmet scientific need that may lead to novel therapeutic strategies in this highly morbid condition.

Keywords: Systemic inflammation, intracerebral hemorrhage, subarachnoid hemorrhage, stroke, spleen, immune dysregulation, regulatory T cells, biomarkers

Introduction

Historically, stroke was thought to be a single-organ disease where the most important pathophysiologic processes occur within the central nervous system (CNS) and that these CNS processes determine stroke outcomes. Growing evidence now suggests that stroke is in fact a systemic disease with numerous extra-CNS manifestations including neurogenic cardiac dysfunction,1 lung injury2 and systemic immune dysregulations.3 Stroke therapeutic strategies to date have focused on treating these two compartments separately – targeting the CNS for brain injury and treating systemic complications as their own entity. A paradigm shift is occurring with the emergence of data suggesting that the brain–body crosstalk in stroke may be an important part of the overall pathophysiology and may in fact impact stroke outcome.4,5

The brain–immune system interaction has been extensively studied in ischemic stroke animal models and human cohorts. Immuno-dysregulations following ischemic stroke include upregulation of systemic inflammatory response as well as immuno-suppression-associated post-stroke infections.4 Developing systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) after ischemic stroke is associated with higher National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS) on hospital admission, worse Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS), and worse subsequent stroke outcome and higher mortality.6,7 Post-stroke immunosuppression, often characterized by lymphopenia upon stroke presentation, is strongly associated with increased susceptibility for post-stroke infections.4,8,9 Furthermore, ischemic stroke may be associated with an autoimmune process where systemic T-helper cell type 1 (Th1) reacts to brain-specific antigens such as myelin basic protein (MBP), which may further compound brain injury and worsen stroke outcomes.10,11 Taken together, these data suggest that the peripheral immune system dysregulation is not simply a sequelae of ischemic stroke but an active and important process that further promotes brain injury.

While much is known about ischemic stroke-related immuno-dysregulations, relatively little is known about the systemic immune and inflammatory reactions in hemorrhagic strokes. In this review, we examine the potential roles and impact of systemic inflammatory and immune responses in primary hemorrhagic strokes – intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH) and subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH). Specifically, we will examine potential organ, cellular, and molecular mediators of immune function and human data on the effects of systemic inflammation and immune dysregulations in ICH and SAH complications and outcomes.

The spleen – An immune system checkpoint in ischemic stroke

The spleen is a major reservoir for peripheral immune cells. Splenic activation is associated with altered inflammatory responses, immune system dysregulation, neuroinflammation, increased infection risk and impaired neurological recovery.12,13 Pre-clinical studies showed that the spleen acutely decreases in size and changes its cellular composition upon ischemic stroke onset and the degree of splenic contraction positively correlated with stroke volume.14,15 Obliteration of splenic response pre- or post-stroke either by removing or radiating the spleen reduces infarct size and enhanced recovery in experimental ischemic stroke models.16,17 Human data corroborated the positive association between splenic contraction and initial stroke severity.18

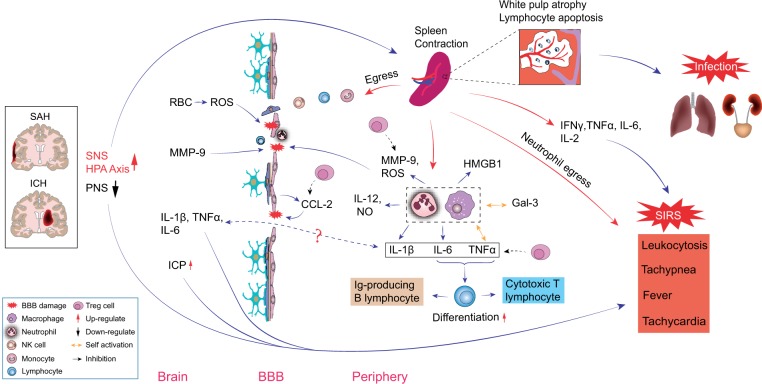

Pre-clinical ischemic stroke studies using middle cerebral artery occlusion (MCAO) models consistently show that spleen contraction in acute stroke is followed by an increase in number of spleen-derived immune cell first in the blood and then in the brain, suggesting possible CNS migration of peripheral immune cells.19,20 Different immune cells appear to migrate at different time points. Spleen-derived natural killer (NK) cells and markers of NK cell activation such as CD69 and interferon gamma (IFN-γ) peak in the brain one day after stroke onset,21 while spleen-derived lymphocytes infiltrate the brain later, peaking at 96 h post MCAO.19 Spleen-derived monocyte/macrophage enters the circulation and then the brain as early as 48 h following MCAO.15,19 As the spleen shrinks, spleen-derived monocytes decrease in number but the ratio of pro-inflammatory Ly-6Chigh to anti-inflammatory Ly-6Clow monocytes increases in the blood and subsequently the brain, reflecting transformation into a pro-inflammatory milieu.20 Splenectomy decreased monocyte/macrophage infiltration into the ischemic brain and alleviated brain injury, suggesting these spleen-derived monocytes play an important role in ischemic stroke brain injury.20,22 Taken together, these data suggest that splenic contraction following ischemic stroke leads to mobilization and release of peripheral immune cells from this reservoir. These peripheral immune cells then infiltrate the CNS and may participate in brain injury processes or affect post-stroke recovery23,24 (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Peripheral Immune System Responses in Hemorrhagic Strokes: Brain-Body Interaction.

Spleen contraction following ischemic stroke also significantly alters the balance of pro- and anti-inflammatory mediators in the peripheral immune system. Within 6–22 h post MCAO, the spleen develops an inflammatory phase when activated splenocytes produce significantly higher levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines including tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α, IFN-γ, interleukin (IL)-2, IL-6 and C-C motif chemokine ligand 2 (CCL2).25 This is followed by a phase of immunosuppression at 22 h to four days post MCAO when both the spleen and the thymus develop dramatic reduction in cellularity, spleen-derived T lymphocyte becomes less responsive to mitogens, and splenocytes express more anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-1025 and less TNF-α, IFN-γ and IL-6.15 At the same time, B lymphocytes numbers contract in both the spleen and the blood, while Regulatory T cell (T reg) numbers markedly expand. Tregs are a specialized subgroup of T lymphocyte that may regulate the immune system, inhibit inflammation and autoimmunity and possibly reduce immune-surveillance.26–28 T reg populations expand both within the spleen and in blood 96 h following MCAO.15 While the mechanism of post-stroke immunosuppression and apparent susceptibility to infection is not known, it is postulated that splenic immune cell changes play an important role in post-stroke immunosuppression.

The spleen and peripheral immune response in hemorrhagic strokes

The spleen in ICH – Animal models

Compared to ischemic stroke, much less is known about splenic changes following hemorrhagic strokes. Few preclinical studies address the relationship between ICH, the spleen, and the peripheral immune system (Table 1). Illanes et al.29 examined changes in immune cell composition, cytokine profiles and infectious complications after ICH in an autologous blood mouse model using three different ICH sizes (10 μl, 30 μl, 50 μl). Large ICH resulted in marked decrease in leukocytes and lymphocytes and a 10-fold increase in monocyte population in the blood and the spleen. Meanwhile, circulating spleen-derived T and B lymphocytes, helper and cytotoxic T lymphocytes all decreased significantly regardless of ICH size. This study did not report spleen size changes but noted that mice with large ICH had significantly lower splenocyte count. A second study demonstrated that ICH leads to splenic contraction in both collagenase injection and in autologous blood injection mice ICH models, where larger ICH volume was associated with more splenic shrinkage in the collagenase model.30 There is evidence that the spleen may mediate neuroprotective therapies in ICH. Using a rat collagenase ICH model, Lee et al.31 observed that human neural stem cell IV infusion 2 h after ICH induction significantly attenuated TNF-α, IL-6 and nuclear factor-kappa B (NF-κB) upregulation in both the brain and in the spleen, but splenectomy prior to ICH induction eliminated beneficial effects of neural stem cell transplantation.

Table 1.

Splenic changes following ischemic and hemorrhagic strokes – Pre-clinical data.

| Author | Animal model | Time points | Relevant results |

|---|---|---|---|

| Intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH) | |||

| Zhang et al.30 | Male C57BL/6J mice, collagenase and autologous blood models | 0, 1, 3 and 7 days post-ICH | Spleen weight was significantly decreased at post-ICH days 1, 3, and 7 in collagenase model. Spleen weight was significantly decreased at post-ICH day 3 and recovered by day 7 in autologous blood model. Larger initial hematoma was associated with increased spleen shrinkage. Blood T lymphocyte, B lymphocyte and NK cell were significantly lower at post-ICH day 1 and were sustained until post-ICH day 7. Spleen T lymphocyte, B lymphocyte and NK cell were significantly lower at post-ICH day 1 but were recovered at post-ICH day 7. |

| Subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH) | |||

| No studies found | |||

| Ischemic stroke (IS) | |||

| Offner et al.15 | Male C57BL/6J mice, transient middle cerebral artery occlusion (MCAO) model (90 min) | 6, 22 and 96 h post-MCAO | Spleen significantly contracted its size at post-MCAO 96 h. Spleen shrinkage was reflected by a reduction of lymphoid tissue and hemopoietic tissue in the red pulp. Spleen shrinkage was associated with decrease of geminal centers and increased apoptotic splenocyte count. Spleen shrinkage was also associated with increased CD4+FoxP3+ regulatory T (Treg) cells and CD11b+ macrophages/dendritic cells. |

| Seifert et al.19 | Male Sprague-Dawley rats, permanent MCAO model | 3, 24, 48, 51, 72 and 96 h post-MCAO | Spleen size was significantly decreased at post-MCAO 24, 48 and 51 h Total number of spleen cell was decreased at post-MCAO 48 h. Spleen-derived monocyte and NK cells were present in the brain at post-MCAO 48 h, lymphocyte T cells of spleen origin were present in the brain at post-MCAO 96 h. Circulating spleen-derived lymphocyte and neutrophil were significantly increased at post-MCAO 48 h; however, spleen-derived monocyte count was significantly decreased at post-MCAO 48 h in the blood. |

| Liu et al.21 | Male C57BL/6J mice, tMCAO model (60 min) | 24 h and 7 days post-MCAO | Spleen volume significantly decreased at post-MCAO 24 h but recovered by post-MCAO day 7. NK cell and splenic CD69 and IFN-γ expressions were significantly decreased on post-MCAO days 1 and 3 and recovered by post-MCAO day 7. Brain NK cell count and CD69 and IFN-γ expressions peaked at post-MCAO day 1 and declined afterwards. |

| Jin et al.68 | Male C57BL/6J mice, tMCAO model (60 min) | 3 and 5 days post-MCAO | The spleen weight and splenocyte count were significantly decreased at post-MCAO days 3 and 5. |

The spleen in SAH – Animal models

We found no studies that examined the spleen in SAH models.

Human data

We performed comprehensive Pubmed literature search using keywords spleen, ICH, SAH, and included all human studies. Table 2 summarizes human data to date on splenic changes in hemorrhagic strokes versus ischemic strokes. Only one small human study exclusively studied ICH patients. This prospective study measured spleen volume in serial abdominal MRIs and showed that splenic shrinkage observed on post-ICH day 3 resolved by day 14 and that larger ICH size is associated with more severe splenic shrinkage. ICH patients with lower lymphocyte and NK-cell counts on presentation had increased risks for infection and unfavorable prognosis.30 Interestingly, the same study also found that splenic contraction is associated with potentially beneficial effects such as decreased perihematomal edema (PHE) expansion and better neurological recovery.30 Other studies combined ischemic stroke and ICH populations and did not separately analyze the ICH sub-cohort. These combined cohort studies consistently found that the spleen shrinks immediately following ischemic stroke/ICH onset.18,21,30,32,33 Splenic atrophy appears to reach nadir at 48 h after stroke/ICH onset, followed by re-expansion and return to normal volume 7–10 days after onset.21,33 Post-stroke/ICH spleen contraction is associated with peripheral immune activation characterized by circulating neutrophil count increase,32,33 lymphocyte and NK-cell count decrease21,30,33 and elevation in circulating pro-inflammatory cytokines such IFN-γ, IL-6, IL-10, IL-12 and IL-13.18 Whether these responses differ between ICH and ischemic strokes is not known as studies to date reported only combined results.

Table 2.

Splenic changes following ischemic and hemorrhagic strokes – Human data.

| Author | Study populations and design | Time points | Relevant results |

|---|---|---|---|

| Intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH) | |||

| Zhang et al.30 | 39 cases, Prospective | 3 and 14 days post-ICH | Spleen contraction (SC) was associated with the hematoma volume on admission. ICH patients with severe SC had lesser perihematomal edema (PHE) expansion and better neurological recovery. Post-ICH infection was associated with T- and natural killer (NK) cell deficiency. Post-ICH infection was associated with poorer clinical outcomes. |

| Ischemic stroke (IS) + intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH) | |||

| Vahidy et al.18 | 158 cases, Prospective | Within 24 h of stroke/ICH onset and daily for 7 days | 40% of stroke patients had substantial SC after stroke. African Americans, elderly patients and patients with history of stroke had higher odds of SC. SC was associated with increased IFN-γ, IL-6, IL-10, IL-12 and IL-13. Patients with SC had significantly higher National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS) score, as compared to those without SC. |

| Chiu et al.33 | 82 cases, Retrospective | Within 24 h of stroke onset and daily for 6 days | SC happened during acute phase (nadir on day 2), followed by spleen re-expansion. The spleen volume was inversely associated with blood lymphocyte count and positively associated with blood neutrophil count. |

| Subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH) | |||

| No studies found | |||

| Ischemic stroke (IS) | |||

| Sahota et al.32 | 30 cases, Prospective | Within 24 h of IS onset and daily for 7 days | Spleen volume decreased until day 3 after stroke, which was followed by re-expansion. No clear associations between spleen volume and initial stroke severity (NIHSS). Significant negative association between neutrophil count and the spleen volume change. |

| Liu et al.21 | 30 cases, Prospective | Post-IS days 1 and 7–10 | Marked SC within 24 h of onset, but re-expansion to initial volume between days 7 and 10 post-stroke. Decreased circulating lymphocyte, NK cell and CD69 expression on post-stroke day1 but these were normalized to basal value at days 7–10. |

We found no human studies reporting on spleen size changes in SAH. Overall, there is a paucity of preclinical and clinical data on the peripheral immune and systemic inflammatory response in hemorrhagic strokes and their possible interplay with hemorrhagic stroke injury mechanisms and outcome.

Potential brain–spleen and brain–immune communications in hemorrhagic stroke

How do acute vascular brain injuries lead to changes in spleen size? Below are several postulated modes of brain–spleen communication:

The sympathetic nervous system/hypothalamus-pituitary-adrenal axis

Sympathetic nerve fibers make up 98% of total splenic innervation.34 Rapid activation of the SNS/HPA axis following stroke onset is thought to be the first mode of communication between the CNS and the peripheral immune system.35,36 Human data from ischemic and hemorrhagic strokes showed that plasma catecholamines and cortisol levels acutely rise following stroke onset.30,37,38 In ICH animal models, pharmacologic inhibition of the SNS/HPA axis by β-adrenergic receptor blocker propranolol and glucocorticoid receptor (GCR) blocker RU486 reversed splenic contraction, confirming the key role of SNS/HPA in post-stroke splenic shrinkage.30 While there are several ways the SNS/HPA can mediate splenic shrinkage, decreased splenic blood flow is not one of them. In a prospective human ICH study, serial abdominal magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed splenic capillary perfusion actually increased during splenic contraction.30 Among all stroke syndromes, SAH is known to cause profound sympathetic activation and catecholamine surges.39–42 Theoretically, the SNS/HPA activation in SAH should result in splenic contraction. However, we found no studies that report splenic changes in SAH.

In addition to direct effects on spleen size, the SNS/HPA system activation may have spleen-independent effects on post-stroke immune deficiency and infection risks. Lymphocytes, NK cells and macrophages express β2 adrenergic receptor and GCR.43,44 Activation of these receptors promotes immune cell apoptosis, reduces cell proliferation and enhances cytokine production in animal ischemic stroke models.44–46 Activation of the SNS can also expand Treg cell population in the bone marrow and thereby directly affect immunomodulation.47 Precisely how the SNS/HPA axis regulates spleen size and spleen-mediated peripheral immune response following ischemic and hemorrhagic strokes is not known. This remains an important knowledge and translational gap.

The parasympathetic nervous system

The parasympathetic nervous system (PNS) is another important mediator by which the brain may regulate the spleen and the peripheral immune system.48 Though the PNS does not directly innervate the spleen, it may modulate splenic immune responses through its interfaces with the SNS.49 PNS activation by the vagus nerve and by α7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor (nAchR) stimulation inhibited inflammatory responses in an animal model of endotoxemia and sepsis. This effect was abolished in splenectomized animals,50 suggesting that the spleen is essential in PNS modulation of systemic inflammation.

PNS activation appears to attenuate both systemic and neuroinflammation in ischemic51 and hemorrhagic52 stroke animal models. In a collagenase ICH rat model, PNS manipulation by intraventricular muscarine injection decreased high mobility group box-1(HMGB-1), TNF-α, IL-1β and Fas ligand (FasL) in both the brain and the spleen and improved neurological outcomes.52 However, the PNS does not appear to play a role in post-ICH splenic contraction since PNS inhibition by α4β2 cholinergic blocker DhβE does not prevent splenic contraction following ICH.30 In SAH models, PNS activation by intraperitoneal injection of α7 nAchR agonist decreased caspase-3 cleavage in neurons and improved neurological recovery in a rat filament-peroration model.53 However, whether the spleen plays a role in PNS-mediated neuroprotection in SAH is not known. In human cohorts, PNS de-activation has been indirectly linked with unfavorable hemorrhagic stroke outcomes. Impaired baroreflex sensitivity (BRS) is a surrogate measure of PNS downregulation. Decreased BRS is independently associated with unfavorable 10-day outcome54 and increased infection risks in ICH patients55,56 and with poor SAH outcome at three month.57

Brain-derived antigens

The brain may directly activate the peripheral immune system by exposing it to CNS-specific antigens and generating an auto-immune response that potentiates secondary brain injury. CNS-specific antigen may come into contact with the peripheral immune system through the injured blood–brain barrier (BBB) or via CNS lymphatic drainage into lymph nodes.58,59 CNS-specific antigens such as microtubule-associated protein-2, N-methyl D-aspartate receptor subunit NR-2A and MBP have been found in the palatine tonsils and cervical lymph nodes from acute ischemic stroke patients, suggesting that the peripheral immune system can become exposed to CNS antigens possibly through lymphatic connections.60 Ischemic stroke animal models found that brain-derived antigens can activate CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in the cervical lymph node and in the spleen61 and shift the peripheral immune response into a Th1-like pattern which is associated with worse neurological outcome.10 Compared with ischemic stroke, little is known about the effects of CNS-specific antigens exposure on peripheral immune activation in ICH and SAH where BBB injury is a prominent feature.

Peripheral immune response as a potential therapeutic target

Targeting the spleen

Growing data suggest that stroke-spleen-peripheral immune system interaction has significant impact on ischemic stroke outcome and possibly on hemorrhagic stroke outcomes. Targeting spleen-mediated immune responses may be a novel therapeutic approach. Stem cells from umbilical cord blood and from the bone marrow are known to preferentially migrate into the spleen where they persist for days.62,63 In ischemic stroke animal models, stem cell transplantation has successfully reversed splenic contraction, increased splenic Treg cell population,62 and protected against ischemic brain injury.14,63,64 These changes are associated with subsequent anti-inflammatory effects including down-regulation of brain TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6 and IFN-γ and up-regulation of anti-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-10 within the spleen.62

In autologous blood injection ICH models, intravenous infusion of bone marrow-derived mononuclear cells (MNCs) reduced peri-hematoma neuroinflammation and brain edema. Similar to ischemic stroke, MNCs appear to preferentially accumulate within the spleen.65 Neural stem cells administered at 2 h after ICH induction also appear to accumulate and persist in the spleen for up to 35 days after transplantation and promote neurological recovery by decreasing TNF-α and IL-6 in the brain and the spleen.31 To date, there are no reports on whether functional or physical splenectomy alters the results of stem cell transplantation in ICH models.

In addition to stem cells, other potential therapies that can target the spleen include SNS inhibitors and statins. In ischemic stroke models, sympatholytic agents agmatine,66 prazosin and carvedilol67 have effectively reversed splenic contraction and reduced brain injury. When administered immediately following stroke, simvastatin reduced splenic atrophy and splenocyte apoptosis, inhibited brain IFN-γ expression and attenuated pulmonary bacterial infection risks in a mouse MCAO model.68 Interestingly, neuroprotective effects of these therapeutic interventions were abolished in splenectomized animals,31,62,68 suggesting that the spleen is essential in the mechanisms of action in these neuroprotective strategies.

Statins and their potential neuroprotective effects have been extensively studied in SAH. Multiple pre-clinical69 and some small human clinical trials70–72 all found statins to be beneficial in reducing vasospasm and improving outcome in SAH. However, recent large phase 3 randomized clinical trial demonstrated no outcome benefit from statin use in SAH.73 Sympatholytic agents have also been tested in SAH. β-blockers suppressed the elevation of CSF IL-6 in animal models74 and small SAH human cohort studies suggest that they improve outcome.75–77 However, these results have not been validated in sufficiently powered clinical trials.

Targeting regulatory T cells

There is growing data supporting Tregs as master immune regulators in multiple organ systems including the brain. In ischemic stroke, Tregs regulate inflammation, balance brain pro-inflammatory (TNF-α and IFN-γ) and anti-inflammatory (IL-10) cytokine production, restore immune homeostasis, and are potentially neuroprotective.26,27,78–81 Tregs may protect BBB integrity by inhibiting matrix metallopeptidase (MMP)-9 production27 and preserve endothelial function by inhibiting endothelial CCL-2 production.82 Within the CNS, Tregs can shift the microglia/macrophage response toward a more favorable M2-like phenotype and secret CCN3 to promote oligodendrocyte progenitor cell differentiation.83

Emerging data suggest that Tregs may also be neuroprotective in ICH84,85 and SAH.86 In autologous blood injection ICH models, boosting Tregs via either adoptive transfer or with CD28 super-agonist antibody stimulation alleviated ICH-induced inflammatory injury by inhibiting microglia activation and modulating microglia/macrophage polarization toward a more favorable M2 phenotype.84,85 In a rat SAH model with autologous blood injection into the cisterna magna, adoptive Treg transfer decreased inflammatory reactions by hindering the activation of toll-like receptor 4/nuclear factor-kappa B (TLR4/NF-κB) signaling pathway.86 Data on Treg changes following ICH have been consistent across human and animal studies, though the number of available studies on ICH is far fewer than that in ischemic stroke. In both animal and human studies, the proportion of circulating Tregs positively correlates with ICH hematoma size, extent of spleen atrophy and ICH disease severity.29,87 These characteristics make Treg a very attractive potential therapeutic target in acute brain injury. In vivo, Treg population can be successfully expanded by low-dose stimulants such as IL-2, IL-2 + anti IL-2 antibody JES6-1 complex88 and monoclonal antibodies against DR3.89 This ability to manipulate Treg population is an important step towards translation of Treg into human therapy in ICH and SAH.

While Tregs possess numerous attractive characteristics as a novel therapeutic target, important caveats exist in its translation into human therapy. The reactive expansion of Tregs following brain injury is thought to be an endogenous mechanism to protect the brain from overactivated immune response, but precise mechanisms remain incompletely understood. Animal models do not fully capture the complexity and heterogeneity in human host conditions and baseline immune status. Moreover, there are important differences between human data and animal model observations on Treg responses in ischemic stroke. While animal studies consistently reported Treg population expand following ischemic stroke15 and that SNS activation stimulates Treg expansion,47 human studies found that Treg decreases immediately following stroke, reaching nadir after two days, and then slowly re-expands.90 An important next step towards potential translation of Treg therapy is to better characterize the peripheral immune and Treg responses to human hemorrhagic and ischemic strokes. Another concern in Treg cell therapy is the potential for immunosuppression and post-stroke infections. In ischemic stroke, animal studies found that adoptive Treg cell transfer preserved peripheral lymphocyte populations and did not lead to immunosuppression.27,78 No such study has been conducted in ICH or SAH where infection risks are relatively high and associated with worse outcome.91 Furthermore, most animal studies focused on short-term outcomes. The long-term effects of Treg cell therapy remain unknown. One particularly important consideration in Treg cell therapy is the potential risk for malignancy over time. Longer term animal studies and translational studies are clearly needed to further understand the potential effects of therapeutic Treg expansion or Treg transfer in human ischemic and hemorrhagic strokes.

Peripheral immune system response in hemorrhagic stroke outcomes in clinical populations

The lack of biomarkers that reflect disease progression and predict clinical outcomes remains a significant unmet need in hemorrhagic strokes. Mediators of systemic inflammation and immune response are one of the largest class of biomarkers that have shown associations with clinical complications and outcomes in hemorrhagic strokes. These signals suggest that systemic inflammatory response is a prominent feature and that the peripheral immune response may impact secondary brain injury and recovery in hemorrhagic strokes. Here, we review available data on cellular and molecular mediators of peripheral immune response and inflammation in hemorrhagic strokes.

Peripheral immune cells and hemorrhagic stroke

Blood total leukocyte count

Human studies have consistently demonstrated that increase blood leukocyte count is associated with higher disease severity and worse outcomes in ischemic92,93 and in hemorrhagic strokes (Table 3), though most are retrospective studies limited by known and unknown confounders. Higher leukocyte count is consistently associated with larger ICH volume across all studies, while its association with ICH mortality and infection risk is only reported in one study.94 There are conflicting data on the association between leukocyte counts and ICH prognosis.94,95 One study found higher leukocyte count was associated with reduced risk of ICH hematoma expansion96 which suggested potential beneficial effects of systemic leukocytosis. Given the limitations of retrospective studies and inconsistent results, larger and prospective studies are needed to elucidate the relationship between leukocyte count and ICH outcomes.

Table 3.

Circulating leukocytes and hemorrhagic strokes outcomes.

| Author | Study population and design | Time points | Relevant results |

|---|---|---|---|

| Intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH) | |||

| Yu et al.95 | 2630 cases, Retrospective | At hospital admission | Higher total white blood cell (WBC) count was associated with larger baseline hematoma volume and ICH intraventricular expansion. Hospital admission WBC was not a predictor of three-month ICH outcome. |

| Morotti et al.96 | 1302 cases, Retrospective | At hospital admission | Higher leukocyte and neutrophil counts were associated with reduced risk of hematoma expansion. Higher monocyte count was independently associated with hematoma expansion. No correlation between lymphocyte and hematoma expansion. |

| Tapia-Perez et al.94 | 43 cases, Retrospective | At hospital admission and at 3 and 7 days post-stroke | Patients who died within 30 days of ICH had higher leukocyte and neutrophil counts on hospital admission. Leukocytosis at post-stroke day 3 was associated with increased risk for respiratory infection. |

| Subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH) | |||

| Al-mufti et al.97 | 849 cases, Prospective | Within 72 h of SAH onset | In SAH patients with World Federation of Neurosurgical Societies (WFNS) Grade < 3, WBC was the strongest predictor for delayed cerebral ischemia (DCI) compared to other cell counts from a complete blood count panel. |

| Srinivasan et al.98 | 246 cases, Prospective | Within 24 h of SAH onset | Leukocyte count was significantly higher in patients with DCI and infarcts at 3-month. Leukocyte count on hospital admission was inversely correlated with Glasgow Outcome Scale (GOS) score at 3-month. |

| McMahon et al.99 | 179 cases, Prospective | 0–13 days after SAH onset | Final value and rate change of leukocyte count were associated with DCI. |

| Chamling et al.100 | 89 cases, Prospective | On hospital admission and 1,4,7,10 and 14 days post-SAH | High leukocyte on hospital admission was associated with increased occurrence of DCI. |

| Chou et al.133 | 55 cases, Prospective | 0–14 days post-SAH | Elevated WBC and neutrophil counts in blood over time were independently associated with vasospasm after adjusting for SAH clinical severity and age. Early rise of blood neutrophil count was associated with poor 3-month SAH clinical outcome. |

| McGirt et al.134 | 224 cases, Retrospective | 1-5 days post SAH | Serum leukocyte count greater than 15 × 109/L was independently associated with vasospasm. |

| Da Silva et al.220 | 55 cases, Retrospective | First 7 days after SAH onset | Leukocytosis on day 3 post-SAH was significantly associated with DCI. |

| Ischemic stroke (IS) | |||

| Nardi et al.92 | 811 cases, Prospective | Within 12 h of IS onset | Higher WBC predicted worst clinical presentation and worse NIHSS at day 3 post-IS and worse mRS at hospital discharge. Leukocytosis was an independent predictor of poor initial disease severity (NIHSS). |

| Sahota et al.32 | 30 cases, Prospective | 6 h – 7 days after IS onset | Neutrophil count was negatively associated with spleen volume change. Leukocyte count did not predict outcome. |

Unlike ICH, there are abundant prospective human data in SAH to suggest elevated circulating leukocyte is associated with poor outcome and SAH complications97–101 (Table 3). Across studies, early increase in blood leucocytes predicted delayed cerebral ischemia (DCI) and poor SAH outcome, while its association with cerebral vasospasm was inconsistent. In addition to single time-point elevations, leukocyte elevation throughout 0–14 days post SAH predicted SAH patients who develop subsequent vasospasm and poor long-term outcome.101

Lymphocyte and monocyte count in blood

In addition to total leukocyte count, individual leukocyte subpopulations may undergo specific changes following ischemic and hemorrhagic strokes. Table 4 summarizes data to date on known associations between circulating lymphocyte and monocyte subpopulations in ICH and SAH. One large retrospective study in ICH found lower lymphocyte count is associated with larger hematoma volume, presence of intraventricular hemorrhage (IVH), lower initial GCS, and is an independent predictor of infection risk and three-month mortality.79 A prospective study that combined ICH and ischemic stroke cohorts corroborated the association between lymphopenia, higher stroke severity and higher infection risks.80 Beyond total lymphocyte count, changes in specific lymphocyte subpopulations appear to be important in ICH prognosis. One small prospective study with mixed ICH and ischemic stroke cohorts showed that T lymphocytes decline or delayed recovery is associated with initial stroke severity and post-stroke infection risk, while lower B lymphocyte count and increased B cell CD86 expression are associated with poor three-month stroke outcome.9,90 The observation of acute lymphopenia and the association between lymphopenia, initial stroke severity, subsequent infection risk, and poor outcome are consistent across ischemic stroke and ICH.9,90,102–104

Table 4.

Circulating lymphocyte and monocyte and hemorrhagic stroke outcomes.

| Author | Study population and design | Time points | Results |

|---|---|---|---|

| Intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH) | |||

| Morotti et al.217 | 2014 ICH cases, Retrospective | Within 24 h of ICH onset | Admission lymphocytopenia (AL) was associated with larger hematoma volume, higher frequency of intraventricular hemorrhage (IVH) and lower GCS on presentation. AL was independently associated with higher risk for pneumonia and multiple infections. AL was an independent predictor of three-month mortality. |

| You et al.108 | 413 ICH cases, Prospective | Within 24 h after ICH onset | Higher monocyte count on hospital admission was associated with worse clinical outcome (mRS) at 3-month. High monocyte-to-high-density lipoprotein (HDL) ratio was associated with increased odds of disability or death at discharge and at 3-month. |

| Walsh et al.109 | 240 ICH cases, Prospective | Within 24 h after ICH onset | Increased baseline monocyte count was independently associated with higher 30-day case-fatality. |

| Shi et al.87 | 90 ICH cases, Prospective | Days 3 and 7 after ICH onset | Percentage of circulating Tregs was higher in ICH compared to controls. Higher initial ICH severity (higher NIHSS) was associated with increase in circulating Treg at 3 and 7 days post-ICH. ICH patients had significantly higher plasma TGF-β and IL-10 compared to controls. |

| Zhang et al.30 | 39 ICH cases, Prospective | On hospital admission, 3 and 14 days post-ICH | Lymphocytopenia was present and sustained up to day 14 post-ICH. ICH patients who presented infection during hospital stay had significant lower T lymphocyte and NK cell count. |

| Subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH) | |||

| Zhou et al.105 | 27 SAH cases with craniotomy and clipping surgery, Prospective | On hospital admission, 1, 3 and 6 days post-op | Percentage of CD3+, CD8+, natural killer T (NKT), CD4+ and Treg cells was significantly decreased on post-op day 1. Natural killer (NK), NK group 2 member D (NKG2D) and B cells were increased on post-op day 1. Higher percentage of CD3+, CD4+, CD8+, NK, NKT, NKG2D and Treg cells was associated with better prognosis (GCS). |

| Sarrafzadeh et al.106 | 16 SAH cases, Prospective | Post-SAH days 1 to 10 | SAH patients with symptomatic vasospasm/hydrocephalus showed significantly lower CD4+ T cells, CD8+ T cells and NK cell counts as early as post-SAH day 2 when compared with SAH patients without neurological deficits. Decreased T lymphocyte count was associated with higher risk for pneumonia. |

| Moraes et al.107 | 12 SAH cases, Prospective | Within post-SAH 6 days | SAH had significantly lower lymphocyte count in blood when compared with healthy controls. Lymphocytes were activated in SAH blood (assessed with CD4+CD69+ T cell/total CD4+ T cell and CD8+CD69+ T cell/ total CD8+ T cell ratio). |

| Combined intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH) plus ischemic stroke (IS) cohorts | |||

| Liesz et al.221 | 136 ICH and IS cases, Prospective | On hospital admission, days 2,7 and follow-up at 60–90 days | AL was an independent predictor of bacterial infection. Disease severity (NIHSS) was the only independent predictor of lymphocytopenia. No report on association between lymphocyte count and outcome. |

| Urra et al.90 | 46 ICH and IS cases, Prospective | Within 3 h of stroke onset, days 2,7 and 90 | Disease severity on hospital admission and post-stroke infection was associated with decline of T cells. Poor 3-month outcome (NIHSS) was associated with reduced B cell count and increased CD86 expression on B cells. |

| Ischemic stroke (IS) | |||

| Tuttolomondo et al.104 | 98 IS cases, Prospective | 48 h after stroke onset | Patients with cardioembolic stroke had significantly higher peripheral CD4+ and CD4+CD28- T cells when compared with other subtypes. CD4+CD28- T cell was positively associated with Scandinavian Stroke Scale and NIHSS scores. |

| Jiang et al.103 | 96 IS cases, Prospective | Post-stroke days 1, 3 and 7 | Spleen volume was positively associated with blood B, T-helper cells and cytotoxic T lymphocyte counts on day 3 post-stroke. Spleen volume was negatively associated with Treg count on day 3 post-stroke. Post-stroke infections were associated with reduced spleen volume, increased circulating leukocyte count and percentage of Treg cell count. |

| Wang et al.102 | 50 IS cases, Prospective | On hospital admission and day 7 | B and T lymphocyte counts were negatively associated with stroke severity on hospital admission. B lymphocyte count on hospital admission correlated negatively with long-term neurological outcomes. |

| Vogelgesang et al.9 | 46 IS cases, Prospective | Post-stroke days 1, 7 and 14 | IS induced dramatic and immediate loss of T lymphocyte in the circulation. Delayed recovery of CD4+ T lymphocyte was associated with increased risk for multiple infections. |

| Ren et al.110 | 512 IS cases, Retrospective | Within 24 h of hospital admission | Lower lymphocyte-to-monocyte ratio (LMR) on admission was independently associated with 3-month poor outcome. |

In SAH, few studies reported on changes in lymphocyte subpopulation. They consistently demonstrated significant decrease in circulating T lymphocytes during acute phase SAH.105–107 Specifically, acute SAH may be associated with significant decrease in natural killer T cells (NKT) and Tregs with simultaneous increase in NK, NK group 2 member D (NKG2D) and B lymphocytes105 though data are inconsistent across studies.106 Decreased T lymphocyte count may be associated with higher risk for pneumonia and increased proportions of CD3+, CD4+, CD8+, NK, NKT, NKG2D and Tregs may be associated with better prognosis in SAH.107

While T and B lymphocytes decline, circulating CD4+CD25+FoxP3+ Treg cell population appears to expand following ICH along with elevated levels of serum IL-10 and TGF-β. Post-ICH Treg expansion appears proportional to initial ICH severity.87 There are currently no data on whether Treg expansion in ICH has any effect on long-term ICH outcome. Unlike ICH and ischemic stroke, Treg counts appear to decrease in acute SAH,105 though this must be interpreted with caution because ICH and SAH Treg studies are few and some have very small sample sizes.

In addition to lymphocyte subpopulations, monocyte counts also appear to be associated with ICH outcome. Two separate prospective human ICH studies reported increased monocyte count on ICH presentation to be associated with poor ICH outcome and higher mortality.108,109 Higher monocyte count, or decreased lymphocyte-to-monocyte ratio (LMR), has also been linked to poor outcome in ischemic stroke.110

Taken together, the data to date suggest that the effect of leukocyte subpopulations on hemorrhagic stroke complications and outcomes is complex and different sub-populations need to be examined separately for their effects on hemorrhagic brain injury.

Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio

The coexistence of lymphopenia and leukocytosis on initial stroke presentation suggest that neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR) may be a useful biomarker for stroke severity and outcome (Table 5). NLR is consistently associated with outcome and mortality in ischemic stroke.111–113 Two large prospective and three retrospective ICH cohort studies consistently reported higher NLR is associated with larger baseline hematoma volume114,115 and higher initial NIHSS.115 The association between NLR and ICH outcome appears inconsistent across two large prospective studies.114,115 One retrospective study found higher NLR is associated with more severe peri-hematoma edema growth in ICH.116 In SAH, only two retrospective studies examined NLR and found it to be associated with DCI, in-hospital death and one-year mortality.117

Table 5.

Circulating neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR) and outcomes in hemorrhagic strokes.

| Author | Study population and Design | Time points | Results |

|---|---|---|---|

| Intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH) | |||

| Giede-Jeppe et al.114 | 855 cases, Prospective | At hospital admission and 1, 2, 3, 5, 7, 10, and 14 days post-ICH | Higher NLR (≥4.66) was associated with worse NIHSS and larger hematoma volume on hospital admission and poor outcome (mRS) at 3-month. Patients with NLR > 8.508 had worse NIHSS and larger hematoma on hospital admission and higher odds for poor 3-month outcome. NLR was associated with infectious complications (pneumonia and sepsis). |

| Sun et al.115 | 352 cases, Prospective | On hospital admission | Higher NLR on hospital admission was associated with larger hematoma volume and higher NIHSS. NLR did not predict 3-month outcome. |

| Lattanzi et al.222 | 177 cases, Retrospective | Within 24 h of ICH onset | Higher NLR was associated with worse 3-month outcome (mRS). |

| Gusdon et al.116 | 153 cases, Retrospective | On hospital admission | Peri-hematoma edema (PHE) growth was associated with higher NLR. Each unit increase in NLR was associated with 22% PHE growth per 24-hours. |

| Subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH) | |||

| Huang et al.117 | 274 cases, Retrospective | Not specified | NLR was associated with in-hospital death and 1-year mortality following SAH. |

| Tao et al.140 | 247 cases, Retrospective | Within 24 h of SAH onset | Increased NLR was associated with worse WFNS grade and modified Fisher grade at 3-month. Higher NLR was independently associated with increased risk of DCI and worse functional outcome (mRS ≥ 3). |

| Ischemic stroke (IS) | |||

| Tokgoz et al.111 | 151 cases, Retrospective | On hospital admission | NLR was an independent predictor of 30-day mortality. Optimal cutoff value for NLR was 4.81. |

| Qun et al.112 | 143 cases, Retrospective | On hospital admission | NLR was independently associated with 3-month outcome (mRS). Optimal cutoff for NLR was 2.99. |

| Brooks et al.113 | 116 cases, Retrospective | On hospital admission | NLR was independently correlated with 3-month outcome (mRS). NLR > 5.9 predicted poor outcome and death at 3-month. |

Clinical features of systemic inflammation and immune dysfunction in hemorrhagic strokes

Systemic inflammation response syndrome in hemorrhagic strokes

Clinical SIRS criteria were originally selected to capture systemic inflammation in acute disease or injury such as sepsis.118–120 SIRS is defined as the presence of two or more of the following features: (1) temperature > 38 ℃ or < 36 ℃, (2) leukocytosis (>10,000/µL) or leukopenia (<4 000/µL), (3) tachycardia (>90 beats per min) and (4) tachypnea (>20 respirations per min).121 Presence of SIRS is generally associated with longer intensive care unit (ICU) length of stay, increased number of ICU interventions and mortality.118 In a general ICU population, incremental increase in number of SIRS criteria met at any given time predicted higher mortality in a linear fashion.120 While SIRS is a validated and useful tool for measuring systemic inflammation severity, it has well recognized short-comings122,123 and alternative classification tools have been developed.123 In critically ill patients with ischemic stroke, ICH, and SAH, SIRS remains by far the most common measure of clinical systemic inflammation in the literature.

We performed systemic literature search through PubMed using the following terms: “stroke” “subarachnoid hemorrhage” “systemic inflammation” “systemic inflammatory response syndrome” and identified five human studies that reported the SIRS in SAH (Table 6). Four out of five studies reported a positive association between developing SIRS and higher risk for SAH complications and worse outcomes.124–127 These studies were largely retrospective cohort studies with sample sizes ranging from 40–364 subjects, and SAH outcome was typically reported as 90-day Glasgow Outcome Scale (GOS) and mortality. SIRS criteria were generally assessed within four days of hospital admission. Meeting SIRS criteria was associated with worse initial SAH clinical severity and larger hematoma volume on CT, which suggests that SIRS may be a response to and a surrogate marker for initial SAH severity. Developing SIRS also increased infection risk and SAH-associated morbidity and mortality. A recent retrospective observational study showed early SIRS was associated with worse SAH clinical severity (Hunts and Hess grade) and radiographic severity (modified Fischer score) and total SIRS burden measured by number of SIRS criteria met was predictive of three-month poor outcome in SAH.128 Whether SIRS simply reflects initial SAH severity or whether it exerts independent effects on SAH outcome is not yet known. In a preliminary SAH retrospective cohort study, having SIRS at hospital presentation was independently associated with worse GCS on presentation and higher in-hospital mortality.129

Table 6.

Systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) and outcome in hemorrhagic strokes.

| Author | Sample size and study design | Relevant results |

|---|---|---|

| Intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH) | ||

| Elmer et al.130 | 697 ICH cases, Retrospective | 90% patients met at least 2 SIRS criteria within 48 h of ICH. 35% patients were febrile at a threshold of ≥38.3 ℃. Younger age, male sex, fever, greater number of SIRS criteria met and radiographic infiltrates of chest imaging were associated with antibiotic exposure. |

| Boehme et al.131 | 249 ICH cases, Retrospective | 21.3% patients with ICH developed SIRS. SIRS was associated with increased risk of poor functional outcomes at hospital discharge. (OR 3.74, 95%CI 1.58–4.83) 33% of the effect of ICH scores on poor functional outcome at discharge was explained by the development of SIRS during hospitalization. |

| Combined intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH) plus ischemic stroke (IS) cohorts | ||

| Kalita et al.6 | 75 IS and 125 ICH cases, Prospective | SIRS was present on admission in 60% cases and was more frequent in ICH (64%) compared to IS (53%). Prevalence of SIRS decreased with time: 57% on 2nd day, 43% on 7th day and 21% on 15th day. SIRS on hospital admission correlated with GCS, NIHSS, volume of ICH, infarction size, hypernatremia and respiratory paralysis. Among patients who died, 97% had SIRS. At 3 months: 55% of patients had poor outcomes (mRS ≥ 2) and 82% had SIRS. Number of SIRS criteria was independently associated with NIHSS at admission and duration of hospitalization. |

| Subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH) | ||

| Tam et al.126 | 364 SAH cases, Exploratory analysis of CONSIOUS-1223 | 63% patients were diagnosed with SIRS. Poor WFNS grade and pneumonia were independently associated with SIRS. SIRS burden (number of SIRS variables per day over the first 4 days) was associated with poor outcome but not with vasospasm, neurological deficit or cerebral infarction. |

| Yoshimoto et al.127 | 103 SAH cases, Retrospective | SIRS was highly related to poor clinical grade (Hunts and Hess grade), larger amounts of SAH on CT and high plasma glucose on hospital admission. Occurrence of SIRS was associated with higher mortality and worse GOS. SIRS was associated with increased risks for complications: vasospasm and normal pressure hydrocephalus (NPH) as well as systemic complications, such as respiratory dysfunction, sepsis, disseminated intravascular coagulopathy, cardiac failure and renal failure. |

| Dhar and Diringer124 | 276 SAH cases, Retrospective | SIRS was present in over 50% patients on hospital admission. 85% of patients developed SIRS in over 4 days of SAH. Factors associated with SIRS included: poor clinical grade, thick cisternal blood, large aneurysm size, higher blood pressure on admission, surgery for aneurysm clipping. Higher SIRS burden was independently associated with vasospasm and worse outcome. Greater SIRS burden predicted increased risk of delayed ischemic neurological deficits. |

| Festic et al.125 | 40 SAH cases, Prospective | 88% patients developed SIRS during hospitalization. Serum procalcitonin (biomarker for infection) was specific for all major infections and distinguished sepsis from SIRS. |

| Guterman et al.224 | 66 SAH cases, Retrospective | SIRS developed in 86% patients. The time from SIRS onset to antibiotic initiation was not associated with 6-month mRS scores. Results did not support using SIRS as the only criteria to start antibiotics in patients with SAH. |

We identified three human studies that examined SIRS in ICH (Table 6). All three reported a positive association between SIRS and worse ICH functional outcome at hospital discharge and at three months.6,130,131 One reported that nearly 90% patients met SIRS criteria within 48 h of ICH,130 suggesting that SIRS is highly prevalent in ICH and perhaps not a great tool to distinguish different degrees of systemic inflammation. However, other studies reported lower SIRS prevalence in ICH.6,131 SIRS being present on ICH hospital admission was associated with higher initial NIHSS, worse GCS, larger ICH volume, hypernatremia and the need for mechanical ventilation. One study reported significant associations between SIRS and mortality, where 97% of all patients who died from ICH had met SIRS criteria during their hospitalization.6 Similar to SAH, it is not known whether SIRS is only a surrogate for initial ICH severity or whether it has independent impact on ICH outcome. A preliminary large rerospective cohort study of 2650 subjects showed that developing SIRS was independently associated with in-hospital mortality in ICH after adjustment for age and initial GCS.132

Though clinical data to date are limited by retrospective study design, these data do suggest that SIRS is an important clinical feature in hemorrhagic strokes and may in fact independently contribute to post-stroke complications and outcome. What we don't know is whether it is the global SIRS syndrome or a particular component of SIRS that drives the effect on poor post-stroke outcome, and what the underlying mechanisms may be. There have been no prospective studies that examines whether reducing SIRS could improve hemorrhagic stroke outcome.

SIRS component: Leukocyte changes in SAH and ICH

A number of human studies have identified a positive association between circulating leukocyte elevation and complications and clinical outcomes following hemorrhagic strokes (Table 3).100,133–135

In SAH, the first descriptive studies examined leukocyte measurement at a single time point, typically upon hospital presentation. Leukocytosis exceeding 15 × 109/L within the first five days of SAH was associated with three-fold increase in vasospasm following SAH.134 In a more recent study that examined leukocyte and neutrophil time profiles, elevated blood leukocyte count over the first 14 days of SAH was independently associated with subsequent angiographic vasospasm and worse SAH outcome133 after adjusting for important confounders including age, Hunt and Hess grade, and mode of aneurysm treatment. In this SAH cohort, longitudinal regression analysis showed that patients who were destined to develop angiographic vasospasm and poor outcome had a different leukocyte count profile from the moment they presented with SAH and well before the development of vasospasm and poor outcome. This human data corroborates the hypothesis that patients at risk for complications such as vasospasm and for poor outcome have a different global immune and inflammatory response to the initial insult (SAH) over time, and this difference in immune response can distinguish between patients at risk for vasospasm and/or poor outcome.

The association between leukocyte count and ICH outcome is less clear. In a comprehensive literature search using PubMed, the following search criteria were used: “stroke” “intracerebral hemorrhage” “leukocyte” “systemic inflammation” “systemic inflammatory response syndrome”. We identified three studies that examined the relationship between leukocyte count and ICH outcome in human cohorts (Table 3). Some reported that leukocyte and neutrophil counts at hospital admission were significantly increased in ICH patients who died within 30 days.135 Several studies failed to find a positive association between leukocyte elevation and ICH outcome. Yu et al.95 found that elevated leukocyte count at hospital admission was not an independent prognostic factor in acute ICH. Another study reported that higher leukocyte count on hospital admission may even be favorable, as it was associated with lower risk of hematoma expansion in ICH patients.136

Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR) has been proposed as a potential biomarker for systemic inflammation and mortality in sepsis.137 In ischemic stroke, higher NLR is an independent predictor for mortality at three months.138 In ICH, the two largest prospective studies both showed that higher NLR is associated with worse initial neurological status and larger hematoma volume on hospital admission. However, while one study reported association between higher NLR and worse neurological function at three month following ICH, others could not replicate this finding114,139 (Table 5). In addition to neurological function and hematoma size, higher NLR in ICH is also associated with infectious complications114 and risk for developing peri-hematoma edema.116 Interestingly, while NLR was predictive of ICH complications, total leukocyte counts in these patients did not show any such association, raising the possibility that the interaction of subsets of peripheral immune cells may play a role in ICH complications and outcomes, while leukocyte count as a global measure may be insufficient in reflecting the complex underlying pathophysiology. In SAH, only two retrospective studies examined NLR. These studies found higher NLR to be associated with SAH mortality, SAH clinical severity measured by World Federation of Neurological Surgeons (WFNS) grade and with DCI post SAH.140,141

Taken together, these findings suggest that peripheral inflammatory and immune cells responses may directly impact risks for complications following hemorrhagic strokes and they may represent novel therapeutic targets.

SIRS component: Fever in SAH and ICH

Fever is a classic clinical sign of systemic inflammation and is generally associated with worse outcomes for many acute diseases142,143 and specifically in the neurocritical care patient population including patients with ischemic stroke, ICH, and SAH.142,143 Fever is prevalent in stroke patients, particularly those with ICH.130,144,145 Specifically in SAH, Pegoli et al.146 showed that patients with fewer hours of fever during ICU stay had better clinical outcomes. In addition to outcome, fever also appears to be an independent risk factor for DCI following SAH.147 SAH patients with higher clinical severity (Hunts-Hess grades > 2) and leukocytosis on presentation are at higher risk for developing central fever during the first seven days of their hospital stay.148

Many studies discussed the role of fever in ICH, where higher fever burden is associated with neurological deterioration and lower health-related quality of life at follow-up.142,144,149 Extrapolating from these observations, many experts recommend fever control, or targeted temperature management (TTM) in critically ill patients with brain injuries.150 Whether fever control can improve outcome and reduce hemorrhagic stroke complications has not yet been demonstrated. This is being evaluated in ongoing prospective clinical trials.

Cellular and molecular biomarkers of systemic inflammation and immune dysfunction in hemorrhagic strokes

There are abundant human data to suggest that cellular and molecular mediators of inflammation are upregulated in SAH and ICH and some are be independently associated with clinical outcomes.151

Biomarkers of immune function and inflammation in SAH

Table 7 summarizes human studies to date on biomarkers of immune function and inflammation in SAH. Inflammatory mediators that have shown most consistent associations with SAH outcome across multiple studies include MMP-9, TNF-α and IL-6. Blood and CSF MMP-9 elevations early in SAH course are associated with higher risk for DCI and worse three-month SAH outcome with modified Rankin Scale (mRS) > 2133,152,153 but their associations with vasospasm are inconsistent.101,153 TNF-α is a pro-inflammatory cytokine whose elevation in serum is independently associated with poor three-month SAH outcome but not with vasospasm.154 Associations between CSF TNF-α levels and SAH outcome have been inconsistent.154–156 Blood IL-6, another pro-inflammatory cytokine, is consistently elevated after SAH. Higher IL-6 serum levels have been associated with higher SAH clinical severity (Hunts and Hess grade), increased age, presence of intraventricular and intracerebral hematoma, increased MMP-9 levels, cerebral vasospasm and worse neurological outcomes.153,157 However, the association between IL-6 and vasospasm and poor outcomes is not consistent across studies, with some studies reporting a positive association between high IL-6 and poor outcome,153,156,157 while others do not.154 In SAH, CSF concentration of IL-6 is significantly higher than that in the serum, suggesting an intrathecal origin.156 Some studies report higher CSF IL-6 and IL-1β are associated with worse SAH outcome.157,156

Table 7.

Biomarkers of immune function and inflammation in subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH).

| Biomarker | Study population and design | Relevant results |

|---|---|---|

| Molecular mediators | ||

| Matrix metalloproteinase-9 (MMP-9) | 30 SAH cases, Prospective | Within 48 h of aneurysmal SAH onset, plasma and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) MMP-9 concentration and activity were highly predictive of delayed cerebral ischemia (DCI) occurrence several days later.152 |

| 43 SAH cases and 23 controls, Prospective | Higher serum MMP-9 levels were associated with increased SAH clinical severity (Hunt and Hess grade). Serum MMP-9 levels were elevated in patients with vasospasm and poor outcomes.153 | |

| 55 SAH cases, Prospective | Blood MMP-9 on post-SAH days 4–5 and CSF MMP-9 on post-SAH days 2–3 were independently associated with poor 3-month outcome (mRS>2). Neither CSF nor blood MMP-9 correlated with vasospasm.101 | |

| Interleukin- 1β (IL-1β) | 89 SAH and 12 unruptured aneurysm cases, Prospective | IL-1β was higher in CSF compared to serum in SAH patients.160 No association of IL-1β with SAH severity. |

| Interleukin-10 (IL-10) | 89 SAH and 12 unruptured aneurysm cases, Prospective | Higher IL-10 levels correlated with higher Fisher grade on admission. Higher IL-10 and CRP significantly associated with severe early brain injury (EBI) and increase the susceptibility to pneumonia.160 |

| Tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α) | 52 SAH cases, Prospective | TNF-α was elevated throughout acute phase of SAH. Elevated serum TNF-α over time and elevated TNF-α on post-SAH days 2–3 were independently associated with poor 3-month outcome after adjusting for SAH clinical severity (Hunt and Hess grade) and age. Serum TNFα was not associated with angiographic vasospasm.154 |

| 22 SAH cases and 10 controls, Prospective | Elevated CSF TNF-α levels on post-SAH days 4–10 were associated with poor outcome.155 | |

| 35 SAH cases & 20 controls, Prospective | CSF TNF-α did not show significant association with outcome.156 | |

| Interleukin 6 (IL-6) | 43 SAH cases and 23 controls, Prospective | Higher serum IL-6 levels were associated with increase in Hunt and Hess grades. Serum IL-6 levels were elevated in those with vasospasm and poor outcomes. Expression of MMP-9 was positively correlated with IL-6.153 |

| 52 SAH cases, Prospective | IL-6 was not associated with angiographic vasospasm or SAH outcome.154 | |

| 60 SAH cases, Prospective | IL-6 levels increased with higher Hunt and Hess grade, increasing age, intraventricular and intracerebral hemorrhage. IL-6 levels significantly raised in patients who developed seizures, cerebral vasospasm, chronic hydrocephalus and pneumonia.157 | |

| 35 SAH cases and 20 controls, Prospective | IL-6 in CSF was significantly higher than in serum in SAH patients. CSF IL-6 on post-SAH day 5 was significantly increased in the poor outcome group.156 | |

| Toll-like receptor 2 (TLR2) and Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) | 30 SAH cases and 20 controls, Prospective | Aneurysmal SAH patients had higher plasma TLR4 levels compared to healthy controls. Patients who developed DCI had higher plasma TLR4 levels than those without DCI. Plasma TLR4 on post-SAH day 1 was an independent predictor for DCI and for poor outcome at 3 months post-SAH.161,162 |

| 18 SAH cases and 8 controls, Prospective | None of the study groups showed detectable levels of TLR2 and TLR4 in the CSF on days 0–3 post-SAH. Strongest correlation between soluble TLR2 (sTLR2) levels and outcome were observed with TLR2 levels on post-SAH days 10–12.163 | |

| Nuclear and mitochondrial DNA | 21 SAH cases and 39 controls, Prospective | Plasma and CSF cell-free nuclear and mitochondrial DNA concentrations on hospital admission were significantly higher in SAH patients compared to health controls. CSF nuclear and mitochondrial DNA levels were significantly higher on post-SAH days 1 and 4 in the poor outcome group. High CSF nuclear and mitochondrial DNA levels were associated with worse outcomes in SAH patients.177 |

| Extracellular mitochondria | 41 SAH cases & 27 controls, Prospective | Extracellular mitochondria were identified in the CSF of SAH patients. Extracellular mitochondrial membrane potentials measured by JC1 assays were detected in the CSF of both SAH and control subjects. Control subjects had significantly higher extracellular mitochondrial membrane potential compared to SAH. Higher extracellular mitochondrial membrane potentials in CSF were associated with better SAH clinical grade and with good 3-month outcome in SAH.178 |

| Galectin-3 (Gal-3) | 83 SAH cases, Prospective | Plasma Gal-3 was an independent predictor for poor SAH outcome after adjusting for age, WFNS grade, modified Fischer grade and acute hydrocephalus. Gal-3 levels on days 1–3 significantly correlated with DCI and infarction, but not with angiographic vasospasm.225 |

| C-Reactive protein (CRP) | 106 SAH cases and 21 controls, Prospective | CRP increased incrementally with worse early brain injury and Hunt and Hess grade over 72 h. At 3 months: death or severe disability was more likely with higher platelet activation and CRP.167 |

| 109 SAH cases, Prospective | CSF and blood CRP time courses were not associated with DCI in SAH patients.168 | |

| ADAMTS13 (Disintergrin and metalloproteinase with thrombospondin type 1) | 40 SAH cases and 40 controls, Prospective | Plasma ADAMTS13 activity in SAH patients was significantly lower than in healthy controls.171 Lower plasma ADAMTS13 was associated with mortality in SAH. |

| Von Willibrand Factor (vWF) | 40 SAH cases and 40 controls, Prospective | Plasma vWF antigen and activity were significantly higher in SAH patients compared to healthy controls.171 Increased plasma vWF antigen and activity observed, which was associated with mortality in SAH. |

| 106 SAH cases, Prospective | Plasma vWF concentrations within 72 hours of SAH were associated with poor outcome. Early vWF levels positively correlated with occurrence of all ischemic events and DCI.170 | |

| Asymmetric and symmetric dimethylarginines (ADMA and SDMA) | 56 SAH cases, Prospective | ADMA levels were lower and peak arginine/ADMA ratio was higher in patients with Hunt and Hess grades 1–2 compared to Hunts-Hess 3–5.226 Plasma ADMA levels were higher in patients with DCI compared to non-DCI group. The arginine/ADMA ratio inversely correlated with neurological outcome on the day of hospital discharge and at 3 months. |

| 34 SAH cases, Prospective | Baseline plasma arginine/ADMA ratio was significantly lower in patients with DCI. CSF ADMA was negatively associated with DCI incidence. CSF SDMA was associated with poor 30-day neurological outcome.172 | |

| High Mobility Group Box 1 (HMGB-1) | 303 SAH cases and 150 controls, Prospective | Plasma HMGB-1 levels on hospital admission were significantly higher in SAH patients compared to healthy controls. In multivariate analysis, plasma HMGB-1 was an independent predictor of poor functional outcome, 1-year mortality, in-hospital mortality and cerebral vasospasm.164 |

| 40 SAH cases, Prospective | Higher CSF HMGB-1 levels were independently associated with unfavorable 3-month outcome.227 | |

| Plasma-type gelsolin (pGSN) | 42 SAH cases and 20 controls, Prospective | pGSN levels in CSF and plasma were lower in SAH patients compared to controls.158 Novel pGSN fragment was identified in CSF of SAH patients but not in control patients. |

| 262 SAH cases and 150 controls, Prospective | Plasma pGSN levels on admission were lower in SAH patients compared to healthy controls. Plasma pGSN was negatively associated with WFNS and Fisher score and was an independent predictor of poor functional outcome and death after 6 months.159 | |

| Soluble intercellular adhesion molecule 1 (sICAM1) | 100 SAH cases, Prospective | Elevated plasma sICAM-1 levels on days 8–12 post-SAH was associated with poor outcome (mRS 4–6) at discharge.169 |

| Clusterin | 27 SAH cases and 25 controls, Prospective | Mean CSF clusterin levels were significantly higher healthy controls compared with SAH. Significantly higher levels of CSF clusterin were found in patients with good outcomes on post-SAH days 5–7. CSF clusterin levels on post-SAH days 5–7 correlated with 3-month outcome.228 |

| Cellular mediators (please see tables 2, 3 & 4) | ||

Plasma-type gelsolin (pGSN) is cleaved by MMP-9 and is postulated to have anti-inflammatory effects. SAH patients have lower blood and CSF pGSN levels compared to controls.158 Lower plasma pGSN is an independent predictor of poor outcome and mortality after six months.158,159 Another mediator with anti-inflammatory effects, IL-10 appears to have elevated blood levels post SAH and is associated with early brain injury and increased risk of pneumonia in SAH.160

Toll-like receptors (TLRs) are a class of innate immunity receptor known to recognize damage-associated molecular pattern (DAMP). TLR-4 is not detectable in the CSF following SAH161–163 but higher plasma TLR-4 levels have been linked to higher DCI risk in SAH.162 HMGB-1 is an important nuclear protein that regulates DNA transcription. Immune cells such as macrophages and monocytes secrete HMGB1 which binds to TLR-2 and TLR-4, leading to NF-κB upregulation and subsequently stimulate macrophage cytokine release. In SAH, higher plasma and CSF levels of HMGB-1 are associated with worse outcome.103,164

Several studies explored C-reactive protein (CRP) as a potential biomarker in SAH. CRP is an acute phase reactant generally elevated in many acute conditions.165,166 In SAH, CRP appears to increase incrementally in parallel with SAH clinical severity and may be associated with death or severe disability at three months.167 However, its association with DCI is inconsistent across studies (Table 7).167,168 Another non-specific inflammatory marker found to be elevated in SAH is soluble intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (sICAM1). Delayed increases in plasma sICAM-1 levels on post-SAH days 8–12 are associated with worse outcome at discharge.169 Just like the case of CRP, the association between sICAM1 and DCI after SAH is inconsistent.170 It is possible that these markers reflect generalized, nonspecific systemic inflammation but may not directly participate in the pathogenesis of brain injury in SAH.

Molecular mediators of endothelial function such as von Willbrand factor (vWF), ADAMTS13 (a disintegrin and metalloproteinase with thrombospondin type 1) and asymmetric dimethylarginine (ADMA) also appear to be important in SAH-associated inflammatory responses. vWF-antigen levels and activity in plasma are significantly higher in SAH compared to controls.171 One prospective SAH cohort study with 106 subjects showed that early serum vWF increase is associated with DCI and poor outcome following SAH.170 ADAMTS13, a metalloproteinase that cleaves vWF, is significantly lower in SAH than in controls.171 Asymmetric dimethylarginine (ADMA), a competitive inhibitor of nitric oxide synthase (NOS), can induce vasoconstriction by reducing nitric oxide production and potentiate endothelial dysfunction and inflammation. Recent studies showed that higher plasma and CSF ADMA to be associated with SAH clinical severity (Hunts and Hess grade) and DCI, while lower plasma arginine/ADMA ratio was associated with DCI in SAH.171,172

Circulating cell-free deoxyribonucleic acid (cfDNA) is emerging as novel biomarkers in cancer as well as cardiovascular diseases. Primarily released due to cell death and necrosis, blood cfDNA was recently shown to be a potential biomarker for short-term173 and long-term ischemic stroke outcome174,175 and may distinguish between ischemic and hemorrhagic strokes.176 A study with 21 SAH patients and 39 health controls undergoing myelography found that SAH patients had higher blood and CSF nuclear and mitochondrial cfDNA levels and higher CSF nuclear and mitochondrial cfDNA levels were associated with worse SAH outcome.177 In addition to extracellular DNA, a recent study demonstrated that extracellular organelles may also play an important role in hemorrhagic strokes and could be a candidate biomarker. This study reported presence of extra-cellular mitochondria in cell-free SAH CSF and detected active mitochondrial membrane potentials in CSF from control and SAH subjects, suggesting these mitochondria may be at least partially functional. CSF extracellular mitochondrial membrane potentials were significantly higher in control subjects compared to SAH. In SAH subjects, lower CSF extracellular mitochondrial membrane potentials were associated with worse clinical grade and independently associated with worse three-month SAH outcome.178

Biomarkers of immune function and inflammation in ICH

Several mediators associated with SAH complications and outcome also exhibit similar associations with ICH (Table 8). Similar to SAH, increased blood MMP-9 levels in ICH appear deleterious and associated with ICH hematoma expansion.179 A prospective study of hypertensive ICH patients found serum TNF-α and IL-11 to be significantly higher in ICH compared with controls and their elevations are associated with ICH severity.180 Soluble TNF receptors (TNFR) 1 and 2 in blood are associated with higher incidence of ICH,181 but whether these markers are elevated after ICH onset or their effects on ICH outcome have not been studied.

Table 8.

Biomarkers of immune function and inflammation in intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH).

| Biomarker | Study population and design | Relevant results |

|---|---|---|

| Molecular mediators | ||

| Matrix metalloproteinase-9 (MMP-9) | 186 hypertensive ICH, Prospective | Increased plasma MMP-9 was an independent risk factor for hematoma expansion in patients with acute hypertensive cerebral hemorrhage.179 |

| Tumor Necrosis Factor α (TNF-α) | 99 hypertensive ICH cases and 45 controls, Prospective | Serum TNF-α was higher in ICH cases compared to controls. Serum TNF-α was higher on day 3 after ICH onset than other time points. Serum TNF-α levels were associated with disease severity.180 |

| Interleukin 11 (IL-11) | 99 hypertensive ICH cases and 45 controls, Prospective | Serum IL-11 was higher in ICH cases compared to controls. Serum IL-11 peaked at day 7 and dropped below baseline at day 14 post-ICH. Serum IL-11 levels were associated with ICH severity.180 |

| Toll-like receptors 2 and 4 (TLR 2 and TLR 4) | 141 ICH cases, Prospective | Patients with poor outcome (mRS > 2 at 3 months) showed increased expression of blood TLR2 and TLR4 in both monocytes and neutrophils at admission. Increased expression of TLR2 and TLR4 was associated with greater residual lesion volume at 3 months in ICH patients.182 |

| CD163 | 41 ICH cases, Retrospective | Mean serum CD163 levels (measured by ELISA) on day 1 were significantly associated with functional outcome at 3 and 12 months.188 |

| Galectin 3 (Gal-3) | 110 ICH cases and 110 controls, Prospective | Increased plasma Gal-3 correlated with injury severity reflected by hematoma volumes and NIHSS scores, as well as systemic inflammation reflected by CRP levels following ICH. Higher plasma Gal-3 levels predicted mortality at 1-week and at 6 months post-ICH as well as unfavorable ICH outcome at 6 months.229 |

| C-Reactive protein (CRP) | 399 ICH cases, Prospective | Plasma CRP>10 mg/L on hospital admission independently predicted early hematoma growth and early neurological worsening, which was associated with increased mortality.185 |

| 91 ICH patients, Retrospective | Plasma CRP level at 24 h from admission was significantly associated with hematoma volumes and 30-day mortality.186 | |

| YKL-40 (chitinase-3-like protein 1 (CHI3L1) | 172 ICH cases and 172 healthy controls, Prospective | Serum YKL-40 levels were an independent predictor of 3-month clinical outcomes. Serum YKL-40 was associated with disease severity (measured by NIHSS scores) and long-term clinical outcomes (measured by mRS) in ICH patients.230 |

| Hepcidin | 81 ICH cases, Prospective | Higher serum hepcidin levels 3 days after ICH onset correlated with poor mRS scores at 3 months.187 |

| Ferritin | 41 ICH cases, Retrospective | Elevated mean serum ferritin concentrations on days 1 and 7 post-ICH were associated with poor outcomes at 3 months. Day 7 ferritin levels were independently associated with 12-month outcomes.188 |

| HMGB-1 | 60 ICH cases and 40 controls, Prospective | Compared to controls, ICH patients had higher HMGB-1 levels in serum. Serum HMGB-1 levels correlated with IL-6 and TNF-α, NIHSS score on day 10 and mRS at 3 months. Patients with poor outcome had significantly higher HMGB-1 levels compared to patients with favorable outcomes at 3 months.184 |

| Nuclear and Mitochondrial DNA | 60 ICH cases and 60 healthy controls, Prospective | Plasma nuclear DNA levels correlated with GCS and ICH volume at initial presentation. Plasma nuclear DNA levels from days 1 to 7 post-ICH were elevated in the poor outcome group.183 |

| Cellular mediators (Refer to Tables 3 to 5) | ||