Abstract

Acute stroke care systems in Southeast Asian countries are at various stages of development, with disparate treatment availability and practice in terms of intravenous thrombolysis and endovascular therapy. With the advent of successful endovascular therapy stroke trials over the past decade, the pressure to revise and advance acute stroke management has greatly intensified. Southeast Asian patients exhibit unique stroke features, such as increased susceptibility to intracranial atherosclerosis and higher prevalence of intracranial haemorrhage, likely secondary to modified vascular risk factors from differing dietary and lifestyle habits. Accordingly, the practice of acute endovascular stroke interventions needs to take into account these considerations. Acute stroke care systems in Southeast Asia also face a unique challenge of huge stroke burden against a background of ageing population, differing political landscape and healthcare systems in these countries. Building on existing published data, further complemented by multi-national interaction and collaboration over the past few years, the current state of acute stroke care systems with existing endovascular therapy services in Southeast Asian countries are consolidated and analysed in this review. The challenges facing acute stroke care strategies in this region are discussed.

Keywords: Health care, health services, stroke care, thrombectomy, thrombus aspiration

Introduction

Southeast Asia (SEA) comprises 11 countries: Indonesia (IND), Philippines (PHL), Vietnam (VNM), Thailand (THA), Myanmar (MMR), Malaysia (MYS), Cambodia (KHM), Laos (LAO), Singapore (SGP), East Timor (TMP) and Brunei (BRN). SEA spans approximately 4.5 million km2, which represents 3% of Earth's total land mass, with a total population of more than 641 million corresponding to 8.5% of the entire world. This is the third most populous geographical region in the world after South Asia and East Asia, with significant ethnic and cultural diversity. Of the 11 countries, 10 are members of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), a regional organisation established for economic, political, military, educational and cultural integration. According to the new 2017 classification by the World Bank,1 the income per capita of these countries varies widely six of these countries are in the group of lower-middle income economies (IND, PHL, VNM, MMR, KHM, LAO), two are upper-middle income economies (MYS, THA) and two belong to the group of high-income economies (SGP, BRN).

According to the World Health Organisation (WHO) policy brief released on World Stroke Day in 2016, over 11 million strokes occur in lower–middle income countries (LMIC), including those in the Southeast Asian region. Mortality is high at more than 4 million annually, with 87% of these deaths occurring in the LMICs.2 Amongst all stroke survivors, 30% are severely disabled and the rest carry an increased likelihood of suffering recurrent strokes – approximately one in four stroke victims will have another one within 10 years.3

Recurrent stroke is a unique feature of stroke disease in SEA, attributable to the high prevalence of intracranial atherosclerotic disease (ICAD) in this region compared with the western world.4 This is evidenced by the fact that 20–30% of all strokes in the Asian population are related to intracranial atherosclerotic disease as compared with 8–10% in the Caucasian population.4 The incidence increases with age, involves the posterior circulation more than the anterior circulation and is more severe when the posterior circulation is affected. ICAD further complicates endovascular therapy (EVT) case selection and choice of EVT techniques, increases EVT complication and failures rates, as well as increasing the need for intra-procedural angioplasty and stenting.

Incidence and prevalence of stroke disease in SEA

At present, the number of well-designed, population-based studies related to the incidence and prevalence of stroke in Southeast Asian countries is limited. This is in part due to large variation and non-standardized methodology of data analysis, and the results are often incomplete.

Data extracted from a recent study of Asian countries by Venketasubramanian et al. are summarized in Table 1, and revealed the lack of data from most of the regional countries.5 The best available data are from Singapore, where the estimate of stroke prevalence in a sample population of 5.6 million is 3.65% and incidence stands at approximately 180 per 100,000 population per year, within the range of estimated overall incidence of stroke in Asian countries of approximately 116–483 per 100,000 population/year.6 This compares to approximately 94 per 100,000 population/year for high-income countries (HIC) and approximately 117 per 100,000 population/year for LMIC, according to a systematic review published in The Lancet Neurology in 2009.7 No data are available from MMR, KHM, LAO and BRN. The lack of incidence and prevalence data from these countries reflects the pressing need for reliable population-based studies in the future.

Table 1.

Stroke pattern (Southeast Asia): Heterogeneous incidence and prevalence in each country.

| Country | Incidence (per 100,000/year) | Prevalence (per 1000) |

|---|---|---|

| Indonesia | NA | 0.84–4.24 |

| Philippines | NA | 9.0 |

| Vietnam | 250 | 6.1 |

| Thailand | NA | 18.8 |

| Myanmar | NA | NA |

| Malaysia | 67 | NA |

| Cambodia | NA | NA |

| Laos | NA | NA |

| Singapore | 180 | 36.5 |

| Brunei | NA | NA |

To put the matter into perspective, over the past four decades, there has been a 42% decrease in stroke incidence in HIC and more than 100% increase in LMICs; and, for the first time, the overall stroke incidence rate in LMICs was found to exceed that of HICs by rate of 20%.7 This can perhaps be explained by Omran's theory that LMICs have entered the ‘health transition’, in which increased exposure to cardiovascular risk factors, for example smoking, raised blood pressure and glucose concentrations, a westernised diet that is low in fruit and vegetables but high in fat and salt, as well as physical inactivity, contribute to increasing stroke incidence in the region.8 It is also noted that such a constellation of cardiovascular risk factors, otherwise known as metabolic syndrome, is associated with intracranial atherosclerosis.9

Stroke types and temporal patterns

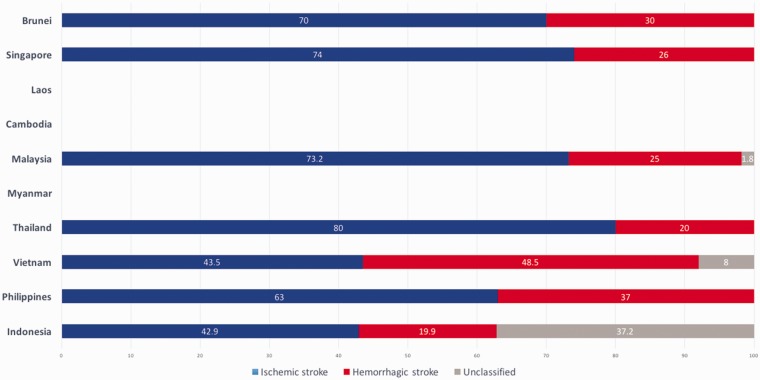

In their review of stroke burden and stroke care system in Asia, Suwanwela et al. noted an increasing trend towards ischemic strokes over haemorrhagic strokes over the years.6 The overall estimate of ischemic strokes in this region is approximately 80% versus 20% of haemorrhagic strokes (Figure 1), which echoes the increasing need for endovascular stroke therapy. This temporal evolution is due to westernisation of diet, ageing population with increasing life expectancy, coupled with improved control of hypertension over the years.

Figure 1.

Proportion of ischemic stroke versus haemorrhagic stroke in each SEA country.

It is also worthy of note that, of all the ischemic strokes, approximately 75–80% occur in the anterior circulation and the rest seen in the vertebrobasilar territory.10

Current status of stroke EVT in SEA

In view of the lack of published data on acute stroke systems and EVT in SEA, a pilot survey was conducted in 2017 amongst leading interventional neuroradiologists (INR) currently active in providing acute stroke EVT in 6 of the 10 SEA countries that have established such a service, to build on existing published information available in each country. Data collected include (1) availability of acute stroke thrombectomy devices, (2) current number of EVT sites and INRs, (3) present number of EVT procedures in each country and (4) projected growth in number of EVT cases.

Results

Availability of acute stroke thrombectomy devices

Acute EVT devices first became available in the SEA region in 2008 when the first-generation device was launched in Singapore. Due to less-than-satisfactory results, newer generations with improved designs were subsequently introduced into the country – Solitaire in 2010 and Trevo in 2012. This was followed by a similar debut of Solitaire stentrievers in VNM, THA and MYS in 2012, and Trevo devices in 2017. Table 2 details the temporal expansion of device availability in Southeast Asia.

Table 2.

EVT device availability.

| IND | PHL | VNM | THA | MMR | MYS | KHM | LAO | SGP | BRN | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trevo | ✓ 2016 | ✓ 2016 | ✓ 2013 | ✓ 2017 | ✓ 2012 | |||||

| Solitaire | ✓ 2016 | ✓ 2012 | ✓ 2012 | ✓ 2012 | ✓ 2010 | |||||

| Balt Catch | ✓ 2017 | |||||||||

| BGC | ✓ 2016 | ✓ 2013 | ✓ 2017 | ✓ 2008 (Merci device) | ||||||

| Penumbra ACE 60–68 | ✓ 2018 | ✓ 2018 | ✓ 2014 | ✓ 2017 | ✓ 2014 |

IND: Indonesia; PHL: Philippines; VNM: Vietnam; THA: Thailand; MMR: Myanmar; MYS: Malaysia; KHM: Cambodia; LAO: Laos; SGP: Singapore; TMP: East Timor; BRN: Brunei.

It is interesting to note that, in the majority of SEA countries, stentrievers were introduced as late as 2016, after a wave of successful EVT trials in 2015. This time-lag in device introduction is due in part to the slow approval process encountered in some of these countries.

Aspiration thrombectomy devices were introduced in this region only recently.

Acute EVT resources: Number of EVT sites and INRs

The number of EVT sites (including those that offer an office-hours-only service and a round-the-clock service) and number of INRs in each SEA country are illustrated in Table 3 – a few observations can be made.

Table 3.

Present situation in Southeast Asia: Number of EVT sites and INRs, as well as population served per site and per INR.

| IND | PHL | VNM | THA | MMR | MYS | KHM | LAO | SGP | BRN | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Population (mil) | 261.1 | 103.3 | 92.7 | 68.7 | 52.9 | 31.2 | 15.7 | 6.8 | 5.6 | 0.42 |

| No of EVT sites | 4 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 0 | 8 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 |

| Public | 0 | 1 | 10 | 10 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 |

| Private | 4 | 9 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| No of EVT sites 24/7 | 4 | 1 | 10 | 10 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 |

| No of INRs | 8 | 4 | 25 | 26 | 0 | 15 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 0 |

| Population per site (mil) | 65.3 | 10.3 | 9.2 | 6.8 | NA | 3.4 | NA | NA | 1.8 | NA |

| Population per INR | 32.6 | 25.8 | 3.7 | 2.6 | NA | 2.1 | NA | NA | 0.9 | NA |

EVT service is not available at all in 4 of 10 SEA countries (MMR, KHM, LAO and BRN). Collectively, these countries represent more than 75 million people or 11.9% of the Southeast Asian population that have no access to EVT service. In those countries that offer an acute EVT service, many are located in city centres with significantly under-served rural areas. Many countries do not have a sufficient number of EVT sites to allow for effective coverage given their geographical size and population. Not all of these EVT sites offer a round-the-clock service. In PHL (1 out of 10), hardly any EVT service is available outside of office hours.

A few SEA nations also have a disproportionate ratio of public versus private institutions offering EVT services; for example, in India and PHL, EVT is dominated by the private sector. One peculiar situation is seen in PHL where there are more EVT sites than there are active INRs, reflecting the nature of private practice and the gross under-utilisation of available resources.

If we subscribe to the belief of having 1 INR per million population, then the vast majority of SEA countries do not satisfy this presumed demand (Table 3). The matter is further complicated by the fact that most of the INRs in Southeast Asia are confined to their specific institution and do not cross-cover, suggesting that the number of INRs required may even be higher.

Present number of acute EVT procedures

From 2015 to the second quarter of 2017, we have witnessed greater than 100% increase in the number of EVT procedures performed in SEA, as illustrated in Table 4. However, if we consider the absolute number of EVT procedures performed in each individual countries, the majority of SEA nations do not even perform 1 procedure per 100,000 population/year in 2016. This is far below the expected projected numbers.11

Table 4.

Present situation in Southeast Asia: Number of procedures 2015–2017.

| IND | PHL | VNM | THA | MMR | MYS | KHM | LAO | SGP | BRN | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Population (mil) | 261.1 | 103.3 | 92.7 | 68.7 | 52.9 | 31.2 | 15.7 | 6.8 | 5.6 | 0.42 |

| 2015 | 5 | 0 | 300 | 95 | 0 | 25 | 0 | 0 | 70 | 0 |

| 2016 | 10 | 3 | 450 | 152 | 0 | 30 | 0 | 0 | 114 | 0 |

| 2017 (up to 2nd quarter) | 8 | 6 | 650 | 186 | 0 | 45 | 0 | 0 | 125 | 0 |

| Procedure per 100,000 population 2016 | 0.004 | 0.003 | 0.49 | 0.22 | 0 | 0.09 | 0 | 0 | 2.0 | 0 |

| Procedure per INR | 1.25 | 0.75 | 18 | 5.8 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 22.8 | 0 |

With regards to the number of procedures performed per INR in 2016, again the majority of countries do not have enough EVT cases to allow for re-accreditation.

Projected growth in number of EVT cases

According to Rai et al.,11 the expected number of EVT procedures is calculated at 3–6 cases per 100,000 population per year, and simple extrapolation yields the estimated number of mechanical thrombectomies per year based on each country's current population – as shown in Table 5. Notably, these number are far greater than the current number EVT procedures in most SEA countries and reflects the potential growth of EVT demand in this region.

Table 5.

Southeast Asia: Projected numbers of EVT each country per year.

| Country | Population (million) | Estimated no of MTs (3–6 per 100,000 person-years) |

|---|---|---|

| Indonesia | 261.1 | 7833 to 15,666 |

| Philippines | 103.3 | 3099 to 6198 |

| Vietnam | 92.7 | 2781 to 5562 |

| Thailand | 68.9 | 2067 to 4134 |

| Myanmar | 52.9 | 1587 to 3174 |

| Malaysia | 31.2 | 936 to 1872 |

| Cambodia | 15.7 | 471 to 942 |

| Laos | 6.8 | 204 to 408 |

| Singapore | 5.6 | 168 to 336 |

| Brunei | 0.42 | 13 to 25 |

Discussion

As with any healthcare system, a successful service hinges on four important factors, namely accessibility, affordability, quality and sustainability. In the current context of acute stroke care in SEA countries, the lack of national-level primary prevention programmes and fragmentary healthcare structures are major obstacles contributing to the huge stroke burden and effective delivery of acute stroke care.

Accessibility and affordability

Healthcare infrastructure determines the type of acute stroke care paradigm in each country, which in turn has a direct effect on its efficiency and performance. Currently, EVT sites are concentrated primarily in major metropoles in large countries, thus leaving large swathes of underserved provincial and rural areas. This is further exacerbated by limited means of effective transport for acute stroke patients in rural areas to EVT centres. Notwithstanding, the present number of EVT sites does not match the expected demand for the number of projected large-vessel-occlusion stroke cases in the majority of SEA countries.

Discussions with leading INRs in the SEA region in 2017 suggested that the lack of government support and socioeconomic status in some of these countries are major constraints in effective and comprehensive development of acute stroke care – in terms of infrastructure, manpower and device availability. Acute stroke care development in any healthcare system represents a significant investment in every country, and the lack of reliable national data such as stroke occurrence and stroke burden hampers governments' ability to make informed and pragmatic policies. This has resulted in the private sector involvement and overshadowing government efforts in some countries, for example in PHL, MLS and IND. On the other hand, this presents a unique opportunity to forge strong partnerships between the public and private sectors by leveraging on the experience gained over the years in private EVT sites.

Apart from deficiencies in acute stroke care infrastructure, the issue of device lag and availability is at present also limited by subvention policies in some SEA countries. For example, anecdotal accounts revealed certain centres have a limited range and combination of devices for mechanical thrombectomy.

The combination of proximal flow arrest using balloon-guiding catheters, distal aspiration techniques or in combination with the use of stentriever devices are essential components for effective mechanical thrombectomy. Restricting the combination of devices at our disposal, due in part to national healthcare fiscal policies and government public hospital subvention policies, negates this effectiveness.

Quality and sustainability

Medical and neuroscience education is at different levels in different SEA countries. Given the complexity of both acute and post stroke management, training needs to be comprehensive, up-to-date and consistent to ensure quality care.

Currently, training guidelines and regulations for practice in EVT in the SEA region are not standardised. Existing international standards from major societies now serves as a guide to ensure consistency and quality of care, but are often not strictly adhered to. Establishment of frequent and regular regional platforms such as the recent AAFITN Conference 2018 in Kota Kinabalu, MYS will bolster discussion and debate in adapting these guidelines to the local SEA ecosystem.

The current low numbers of EVT procedures in some SEA countries poses a challenge in terms of delicate balance between the training new EVT practitioners as well as re-accreditation of existing INRs, with the view of increasing the total number of fully qualified physicians to counter the expected surge in EVT cases.

Reliable and accurate annual projection of EVT numbers in each country will help to estimate training numbers at a rate commensurate with the demand. Similar manpower projections should be made for stroke intensivists and neurologists as training for such practitioners also takes time.

For the time being, one possible course of action to circumvent the issue of prompt diagnosis of acute ischemic stroke, especially in rural areas with deficient number of physicians, is the use of tele-radiology. Close working relationships between hospitals and primary stroke centres, further complemented by a common stroke imaging protocol, will facilitate faster and more accurate assessment of patient condition.

To add insult to injury, according to several INRs in Southeast Asia, some of the low numbers of thrombectomies performed in some SEA countries are allegedly due to reluctance of local neurologists to shift from conservative medical management to active stroke treatment in the form of intravenous rTPA therapy, much less mechanical thrombectomy. This is supposedly due to a lack of confidence in administering intravenous thrombolysis and resistance to change.

Long-term sustainability of care hinges on meticulous planning, appropriate resource allocation and accurate manpower projections. Future installations of comprehensive stroke centres should take into consideration the population density, location of existing EVT sites and their relations to primary stroke centres. Individual national governments' leadership in resource and manpower allocation is paramount.

Summary

Rapid increase and widespread application of mechanical thrombectomy in acute ischemic stroke has created significant strain on practicing EVT physicians in SEA. The Asian population's proclivity for ICAD presents a unique challenge in acute stroke management and further complicates EVT case selection, clot retrieval techniques and clinical outcome. Current endeavours in acute stroke care development are insufficient satisfy the rising demand.

Acknowledgements

We thank Professor Tchoyoson Lim Choie Cheio, Dr. Yu Wai Yung, Mr. Zain Almuthar and the rest of Department of Neuroradiology National Neuroscience Institute Singapore for comments that greatly improved the manuscript.

Declaration of conflicting interests

The authors declared the following potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: The preliminary pilot data was presented at the 14th Congress of World Federation of Interventional and Therapeutic Neuroradiology on 17 October 2017 – Plenary Session 3: Stroke Care Organisation (INV/13) “Acute Stroke Care in South-East Asia” and Commentary Article on South-east Asia region (The burden of stroke: A global perspective) in NeuroNews International published on 16 March 2018.

Funding

The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- 1.Data.worldbank.org. GDP per capita (current US$). Available at: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.PCAP.CD (2018, accessed 24 March 2018).

- 2.World Health Organisation. Policy Brief: Saving lives from strokes – gearing towards better prevention and management of stroke. Available at: http://www.searo.who.int/entity/noncommunicable_diseases/policy-brief-stroke.pdf?ua=1 (2016, accessed 26 March 2018.

- 3.Mohan K, Wolfe C, Rudd A, et al. Risk and cumulative risk of stroke recurrence: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Stroke 2011; 42: 1489–1494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Khan M, Naqvi I, Bansari A, et al. Intracranial atherosclerotic disease. Stroke Res Treat 2011; 2011: 282845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Venketasubramanian N, Yoon B, Pandian J, et al. Stroke epidemiology in South, East, and South-East Asia: a review. J Stroke 2017; 19: 286–294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Suwanwela N, Poungvarin N and Asian Stroke Advisory Panel. Stroke burden and stroke care system in Asia. Neurol India 2016; 64: 46–51. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Feigin VL, Lawes CM, Bennett DA, Barker-Collo SL, Parag V. Worldwide stroke incidence and early case fatality reported in 56 population-based studies: a systematic review. Lancet Neurol 2009; 8: 355–369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Omran A. The epidemiologic transition: a theory of the epidemiology of population change. Milbank Q 2005; 4: 731–757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kim J, Bonovich D. Research on intracranial atherosclerosis from the East and West: why are the results different?. J Stroke 2014; 3: 105–113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Merwick A, Werring D. Posterior circulation ischaemic stroke. BMJ 2014; 348: g3175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rai A, Seldon A, Boo S, et al. A population-based incidence of acute large vessel occlusions and thrombectomy eligible patients indicates significant potential for growth of endovascular stroke therapy in the USA. J Neurointerv Surg 2016; 9: 722–726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]