Abstract

This study examines Medicare Part D prescription drug plans to assess how often branded products were given more favorable formulary placement than generic products.

In the Medicare Part D program, the potential of generic drugs to achieve savings is underused. One reason is that prescription drug plans earn some of their profits through rebates and other price concessions paid by pharmaceutical manufacturers (Medicare calls this direct and indirect remuneration).1 Although the goal of prescription drug plans is to provide cost-effective drug management, the Medicare program has raised concerns that the remuneration structure creates an incentive for plans to prefer higher-priced drugs instead of less expensive alternatives, because manufacturers of higher-priced drugs may offer greater price concessions.1

Methods

We examined the 57 unique drug formularies offered across all 750 Medicare Part D standalone prescription drug plans in November 20162 to determine how often branded products were given more favorable formulary placement than generic products. We defined favorable placement as the placement of a branded product in a lower cost-sharing tier or when a branded product had fewer utilization controls (ie, prior authorization, step therapy, or quantity limits) than its corresponding generic product. We analyzed drugs for which both generic and branded products were available3 (hereafter called multisource drugs) and examined the lowest strength per drug when multiple strengths were available. We compared drug prices by dividing the mean cost per unit of the branded products by the mean cost per unit of the corresponding generic products in 2016 Medicare Part D claims data.4 Because of the confidentiality of price concessions, this approach may have overestimated the difference in price between branded and generic products. The human participants research policy of the Johns Hopkins Institutional Review Board determined that this study did not require approval because it did not involve human participants research.

Results

The 57 formularies covered, on average, 1657 different drugs, of which 935 were multisource. A total of 120 multisource drugs (12.8%) did not have generic products covered in any formulary. A total of 41 of the 57 formularies (72%) placed at least 1 branded product in a lower cost-sharing tier than its generic product, and all formularies had at least 1 multisource drug covered without a generic product. In addition, 17 of the 57 formularies (30%) adopted fewer utilization controls on the branded product for at least 1 drug.

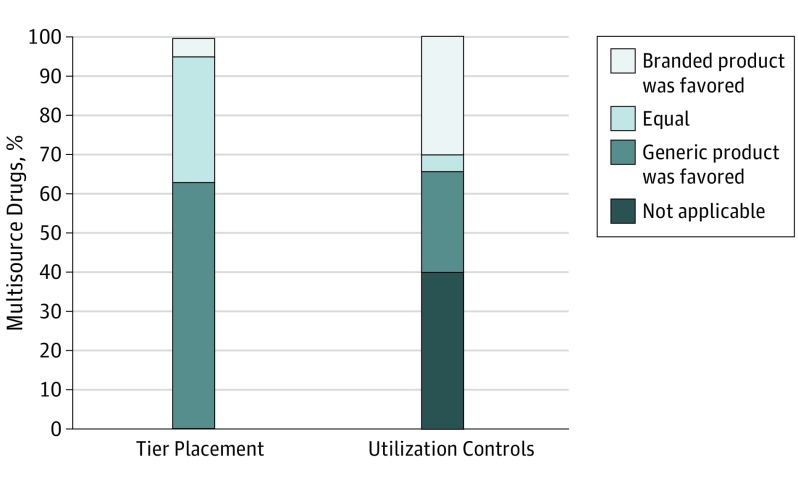

We also examined 222 multisource drugs that were covered in all formularies and had branded and generic products covered in at least 1 formulary. A total of 11 of these drugs (5.0%) had branded products more frequently placed in a lower cost-sharing tier than the corresponding generic products, and 67 drugs (30.2%) had less frequent utilization controls imposed on branded products than on generic products (Figure).

Figure. Multisource Drugs Covered in All Medicare Part D Prescription Drug Plan Formularies, by Cost-Sharing Tier Placement and Utilization Controls.

The sample consists of 222 multisource drugs covered in all Medicare Part D standalone prescription drug plan formularies where the branded and generic product were covered in at least 1 formulary.

Based on the Medicare claims data, we also found that, among these 222 multisource drugs, the price of the branded product was a median of 3.9 times higher than that of the generic product (interquartile range, 1.7-12.5).

Discussion

We found that 72% of Part D formularies had a lower cost-sharing tier and 30% of Part D formularies had fewer utilization controls on branded products for at least 1 multisource drug. Among 222 multisource drugs covered by all formularies, 5.0% had a lower cost-sharing tier and 30.2% had fewer utilization controls on branded products. For a generic product priced at $1, the median price of its branded option was $3.90. This difference is important for beneficiaries because the drug price often determines their cost sharing.

Favorable formulary placement of branded drugs encourages the use of more expensive products and can lead to higher out-of-pocket costs for Medicare beneficiaries and higher expenditures for the Part D program.5 One option is for Medicare to prohibit giving branded products a more favorable formulary placement than generic products. An alternative is to change the incentive structure of Part D plans, as intended by the proposal by the Department of Health and Human Services to remove the “safe-harbor” provision that allows manufacturer rebates to be paid without triggering the federal anti-kickback statute.6 It is important for policy makers to recognize that manufacturers could restructure payments to drug plans as nonrebate items to avoid this restriction.

References

- 1.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, Department of Health and Human Services Proposed rules: Medicare program; contract year 2019 policy and technical changes to the Medicare Advantage, Medicare cost plan, Medicare fee-for-service, the Medicare prescription drug benefit programs, and the PACE program. Pages 56419-56420. https://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/FR-2017-11-28/pdf/2017-25068.pdf. Published November 28, 2017. Accessed August 14, 2018. [PubMed]

- 2.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Prescription drug plan formulary, pharmacy network, and pricing information files. https://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Files-for-Order/NonIdentifiableDataFiles/PrescriptionDrugPlanFormularyPharmacyNetworkandPricingInformationFiles.html. Updated October 3, 2018. Accessed August 14, 2018.

- 3.IBM. IBM Micromedex RED BOOK. http://truvenhealth.com/Products/Micromedex/Product-Suites/Clinical-Knowledge/REDBOOK. Accessed August 14, 2018.

- 4.ResDAC Part D Drug Event File. https://www.resdac.org/cms-data/files/pde. Accessed August 14, 2018.

- 5.Dusetzina SB, Conti RM, Yu NL, Bach PB. Association of prescription drug price rebates in Medicare Part D with patient out-of-pocket and federal spending. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(8):1185-1188. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.1885 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs, Office of Management and Budget Pending EO 12866 regulatory review. https://www.reginfo.gov/public/do/eoDetails?rrid=128288. Accessed August 14, 2018.