Abstract

Background

In Europe, although the prevalence of childhood obesity seems to be plateauing in some countries, progress on tackling this important public health issue remains slow and inconsistent. Breastfeeding has been described as a protective factor, and the more exclusively and the longer children are breastfed, the greater their protection from obesity. Birth weight has been shown to have a positive association with later risk for obesity.

Objectives

It was the aim of this paper to investigate the association of early-life factors, namely breastfeeding, exclusive breastfeeding and birth weight, with obesity among children.

Method

Data from 22 participating countries in the WHO European COSI study (round 4: 2015/2017) were collected using cross-sectional, nationally representative samples of 6- to 9-year-olds (n = 100,583). The children's standardized weight and height measurements followed a common WHO protocol. Information on the children's birth weight and breastfeeding practice and duration was collected through a family record form. A multivariate multilevel logistic regression analysis regarding breastfeeding practice (both general and exclusive) and characteristics at birth was performed.

Results

The highest prevalence rates of obesity were observed in Spain (17.7%), Malta (17.2%) and Italy (16.8%). A wide between-country disparity in breastfeeding prevalence was found. Tajikistan had the highest percentage of children that were breastfed for ≥6 months (94.4%) and exclusively breastfed for ≥6 months (73.3%). In France, Ireland and Malta, only around 1 in 4 children was breastfed for ≥6 months. Italy and Malta showed the highest prevalence of obesity among children who have never been breastfed (21.2%), followed by Spain (21.0%). The pooled analysis showed that, compared to children who were breastfed for at least 6 months, the odds of being obese were higher among children never breastfed or breastfed for a shorter period, both in case of general (adjusted odds ratio [adjOR] [95% CI] 1.22 [1.16–1.28] and 1.12 [1.07–1.16], respectively) and exclusive breastfeeding (adjOR [95% CI] 1.25 [1.17–1.36] and 1.05 [0.99–1.12], respectively). Higher birth weight was associated with a higher risk of being overweight, which was reported in 11 out of the 22 countries. Bulgaria, Croatia, France, Italy, Poland and Romania showed that children who were preterm at birth had higher odds of being obese, compared to children who were full-term babies.

Conclusion

The present work confirms the beneficial effect of breastfeeding against obesity, which was highly increased if children had never been breastfed or had been breastfed for a shorter period. Nevertheless, adoption of exclusive breastfeeding is below global recommendations and far from the target endorsed by the WHO Member States at the World Health Assembly Global Targets for Nutrition of increasing the prevalence of exclusive breastfeeding in the first 6 months up to at least 50% by 2025.

Keywords: Breastfeeding, Birth weight, Childhood obesity, WHO/Europe, COSI Europe

Introduction

Within the World Health Organization (WHO) European Region, childhood overweight and obesity remains an important public health concern. For the last decade, this diverse Region has shown a north-south gradient in the prevalence of overweight including obesity (from 9 to 43% among boys and from 5 to 43% among girls) and obesity alone (from 2 to 21% among boys and from 1 to 19% among girls), with higher rates in the so-called Mediterranean countries [1, 2, 3].

Although the rates seem to be plateauing in some European countries [4], progress in tackling the problem of childhood obesity has been slow and inconsistent. Addressing this serious challenge requires understanding and consideration of the environmental drivers and of the critical time periods in the life course [5].

Infancy seems to be one of the most important periods influencing health later in life, and may thus represent the best time to prevent obesity and its adverse consequences [6]. Among the modifiable risk factors for childhood obesity in the first 1,000 days of life, breastfeeding has been shown by a large body of evidence to be a protective factor [6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11]. A meta-analysis found that breastfeeding was associated with a reduction of 13% in the odds of overweight and obesity [9], and Harder et al. [12] found that each additional month of breastfeeding was associated with a 4% reduction in the prevalence of overweight.

The WHO recommends exclusive breastfeeding until 6 months, with continued breastfeeding and appropriate complementary foods up to 2 years of age or beyond [13]. It has been widely shown that human milk, due to its bioactive compounds, has immunological, endocrinological, neuronal and psychological benefits for the child [8, 14, 15, 16]. Infants who are breastfed exclusively during the first 6 months of life are less likely to have excess weight during late infancy (>6 months of age) [17]. This can be partially explained by the fact that breastfeeding induces different hormonal responses when compared with infant formula, the latter causing a greater insulin response, which leads to fat deposition and increased adiposity [14]. Human milk is also rich in Bifidobacteria, which have been shown to be present to a lesser extent in the gut of obese children. In addition, children who were breastfed seem to have more favourable food preferences, eating more fruit and vegetables as compared to those who are formula fed [18].

Despite strong political commitments and robust evidence on its benefits, the prevalence of breastfeeding (especially exclusive breastfeeding) remains low in the WHO European Region [19]. In 2006–2012, only an estimated 25% of infants were exclusively breastfed for the first 6 months of life in the WHO European Region [20], compared with 40% globally [21]. The goal is to increase this proportion of exclusive breastfeeding up to at least 50% by 2025 [21, 22].

Birth weight has also been found to be associated with childhood and adult obesity [23, 24, 25, 26, 27]. A systematic review and meta-analysis showed that high birth weight (>4,000 g) is associated with an increased risk of obesity [27]. Other studies also confirmed that high birth weight contributes to later childhood obesity [7, 24, 26, 28, 29] and to increased body fat mass [23]. Low birth weight (<2,500 g) occurs due to inadequate intrauterine conditions that lead to abnormal fetal development, and although the influence of low birth weight on the development of obesity is still not so clear [27], it has been associated with lower lean body mass and greater central adiposity, measured by the waist-to-hip ratio or skinfold thickness in adults [30, 31]. This association is supported by studies showing that infants who are born small experience rapid catch-up growth in early infancy, which results in larger fat mass in later life [30, 31].

The collection of data on breastfeeding and birth weight and its association with obesity continues to be limited in the WHO European Region. The WHO European Childhood Obesity Surveillance Initiative (COSI) [2] was established in 2007 with the aim to measure trends in overweight and obesity among children aged 6.0–9.9 years, in order to monitor the progress of the epidemic and to permit inter-country comparisons [1, 2, 32, 33, 34, 35]. In these years the COSI has included more than 35 participating countries [1] and has allowed a thorough and better understanding of some factors underlying childhood obesity. In all four COSI rounds, between 2007/2008 and 2015/2016, data were collected according to a common COSI protocol [36] and a standardized manual of data collection procedures [37]. Besides the mandatory measurements of the children's weight and height, the COSI protocol [36] also includes the option to gather information about simple indicators of the first year of life, such as children's birth weight and breastfeeding practice and duration.

The aim of this study was to evaluate the association between early-life factors, notably breastfeeding (in general and exclusively) and birth weight, and obesity among children participating in the COSI.

Materials and Methods

Study Design and Sampling

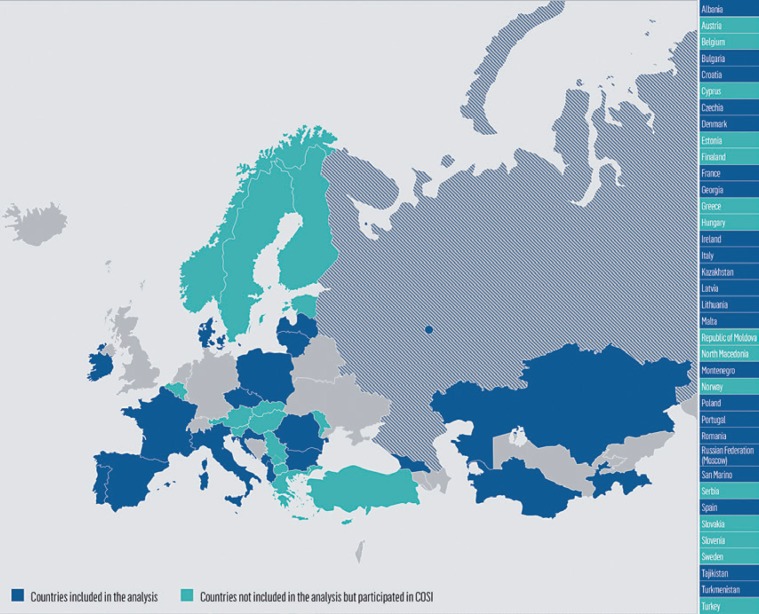

The fourth COSI data collection round was conducted in 2015/2017 in 35 countries from the WHO European Region. Nationally representative samples of children were drawn in all countries except for the Russian Federation, where data collection was carried out only in the city of Moscow. Thirteen countries were not able to apply the voluntary COSI family record form; thus, of the countries participating in the COSI, 22 collected data on breastfeeding and characteristics at birth and were included in this study (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Countries that have participated in the COSI (in at least 1 round of data collection in the period 2007–2017) and countries included in this study.

Thirteen of these 22 countries used two-stage cluster samples, with primary school as the primary sampling unit and school classes as the secondary sampling unit. Five countries adopted a cluster design with classes (Croatia and Italy), schools (Denmark and Latvia) and paediatric units (Czechia) as sampling units. Finally, a three- and four-stage sampling design was used in Bulgaria and Poland, respectively. Malta and San Marino included all classes of their targeted grades of primary schools. Further details on the sampling procedures in each country have been described elsewhere [1, 36, 37].

The countries follow a common COSI protocol [36, 37], which is in accordance with the International Ethical Guidelines for Biomedical Research Involving Human Subjects [38], and the protocol and procedures were also approved by local Ethics Committees. According to the COSI protocol, countries could choose one or more of the following age groups: 6.0–6.9, 7.0–7.9, 8.0–8.9, or 9.0–9.9 years. Most of the countries targeted only 7-year-olds (Bulgaria, Czechia, Denmark, Georgia, Ireland, Latvia, Lithuania, Malta, Montenegro, Portugal, the Russian Federation, Tajikistan and Turkmenistan); others targeted only 8-year-olds (Albania, Croatia, Poland and Romania) or 9-year-olds (Kazakhstan). Three countries targeted two age groups (7- to 8-year-olds in France and 8- to 9-year-olds in Italy and San Marino), while Spain targeted all age groups.

In most of the countries that adopted a sampling approach, the number of measured children per targeted age group was equal to or above the minimum sample size suggested by the Protocol (i.e. 2,800 children per age group), while in 7 countries it was considerably lower (Czechia and Ireland) or slightly lower (Denmark, Montenegro, Lithuania and the Russian Federation). Data on children's body weight, height, sex and age were collected by trained examiners in the Child's Record Form. Children's consent was always obtained prior to the anthropometric measurements. Children's weight and height were measured by fieldworkers who were trained in taking measurements following WHO standardized techniques [36, 37]. Measurements in each country were taken during the data collection period defined for round 4 (2015/2017). Taking into account local arrangements and available budgets, countries chose the most appropriate professionals to measure the children's weight and height (e.g. physical education teachers, national or regional health professionals). The voluntary family record form included questions on a child's birth weight, breastfeeding and its duration, and other environmental and socioeconomic characteristics of the family and was completed by parents or caregivers [37].

Inclusion criteria were: (1) children aged between 6 and 9 years (irrespective of whether or not they belonged to the target age groups); (2) having available data on sex, age, height and adjusted body weight following the procedures explained elsewhere [34, 36]; and (3) having a family record form filled in by the mother, with complete information about breastfeeding and birth weight.

For assessment of the association between breastfeeding practice in general and obesity, 22 countries were included, and for assessment of the association between exclusive breastfeeding and obesity, 12 countries were eligible (Bulgaria, Georgia, Ireland, Kazakhstan, Lithuania, Latvia, Poland, Portugal, the Russian Federation (Moscow), Spain, Tajikistan and Turkmenistan).

Children's Nutritional Status

The body mass index (BMI) was calculated, and the WHO BMI-for-age (BMI/A) distributions for children (>5 years old) were used to compute BMI/A z-scores [39]. Thinness was defined as a BMI/A value below a z-score of −2, normal weight as a z-score between −2 and +1; overweight and obesity were defined as a BMI/A value above a z-score of +1 and +2, respectively. Children who did not have biologically plausible values (i.e. a BMI/A z-score between −5 and +5) were excluded from the analyses.

Definition of Variables

Associations between children's nutritional status and the study variables were assessed considering the following categorization of variables:

General breastfeeding: general breastfeeding was assessed by asking the mother “Was your child ever breastfed?” For mothers who replied “no,” children were categorized as “never breastfed.” Next, mothers who replied “yes” were asked for how many months they breastfed. If they reported breastfeeding for a range between less than 1 month and 5 months, their children were categorized as “breastfed for less than 6 months.” If mothers reported breastfeeding for 6 months or more, their children were categorized as “breastfed for at least 6 months”

Exclusive breastfeeding: mothers were also asked “Was your child ever exclusively breastfed? (Exclusive breastfeeding means that the infant receives only breast milk. No other liquids or solids are given – not even water – with the exception of oral rehydration solution, or drops/syrups of vitamins, minerals or medicines).” For mothers who replied “no,” their children were categorized as “never exclusively breastfed.” Mothers who replied “yes” were asked for how many months they exclusively breastfed. If they reported exclusive breastfeeding within the range of less than 1 month to 5 months, their children were categorized as “exclusively breastfed for less than 6 months.” If mothers reported exclusively breastfeeding for 6 months or more, their children were categorized as “exclusively breastfed for at least 6 months” [10]

The above-mentioned categorization was not available for Italy and San Marino. To these 2 countries the following categorization was applied: never breastfed; breastfed up to 6 months; or breastfed for more than 6 months.

Characteristics at Birth

Preterm birth was defined as below 37 gestational weeks, and full-term birth as at 37 gestational weeks or above [40]. Low birth weight was defined as lower than 2,500 g, normal birth weight as between 2,501 and 4,000 g, and high birth weight as 4,001 g and above [40, 41].

Statistical Analysis

For each country included in the analysis, the prevalence of obesity by duration of breastfeeding (general and exclusive) and the 95% confidence interval (95% CI) were estimated. The statistical significance of associations with obesity was assessed using Pearson's χ2 test corrected using the Rao-Scott method.

Multivariate multilevel logistic regression analysis was carried out for being obese compared to not being obese at country level and by pooling countries. Adjusted odds ratios (adjORs) with 95% CIs for having not been breastfed at all and having been breastfed for less than 6 months versus having been breastfed for at least 6 months were estimated for both general breastfeeding and exclusive breastfeeding. AdjORs and 95% CIs for premature birth (reference category: full term) and low and high birth weight (reference category: 2,500–4,000 g) were also estimated. Children's sex and age, maternal education and weight status, and region/administrative division of residence were included as potential confounders. For maternal educational attainment, two categories were considered: (1) low-to-medium level (i.e. “primary school or less,” “secondary or high school” and “vocational school”) and (2) high level (“undergraduate or bachelor degree” and “master degree or higher”). Maternal weight status was defined using the maternal BMI, which was calculated based on self-reported weight and height. Mothers were classified as “normal weight,” “pre-obese” or “obese” based on WHO definitions [41].

All country-specific models included random effects for the primary sampling units. Because of the low number of obese children, the models for obesity led to less reliable results for Denmark, San Marino and Tajikistan, so these countries were not included in the regression analysis. The Russian Federation was also excluded, because of the lack of information about maternal education. Maternal weight was not assessed in Ireland, and thus the regression analysis for this country was carried out without considering this variable.

As for the pooled models, only countries with available information on the above-mentioned covariates were included. More specifically, 16 countries were included in the regression model with general breastfeeding among the explanatory variables (namely Albania, Bulgaria, Croatia, Czechia, France, Georgia, Kazakhstan, Lithuania, Latvia, Malta, Montenegro, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Spain and Turkmenistan). Italy and San Marino were excluded because the data on duration of general breastfeeding were not compatible with the other country measures. With one exception (Ireland), the pooled model with exclusive breastfeeding included all 8 countries that collected this information: Bulgaria, Georgia, Kazakhstan, Lithuania, Latvia, Poland, Portugal and Spain. The regression analysis of pooled data sets included only children belonging to one target age group for each country: 7-year-olds for 10 countries, 8-year-olds for 5 countries and 9-year-olds for 1 country. The pooled models included random effects for countries.

Post-stratification weights to adjust for the sampling design, oversampling and non-response were available for all countries that applied a sampling approach in round 4 except for Lithuania, and they were used in all analyses to infer the results from the sample to the population. For Lithuania, an unweighted analysis was carried out. All analyses took account of the cluster sample design. In the pooled analysis, an adjusting factor was applied to the post-stratification weights to take into consideration differences in population size of the countries involved. The adjusting factor was calculated based on the number of children belonging to the targeted age group according to Eurostat figures or national official statistics for 2016. Finally, children with a missing value for any of the covariates were excluded from the regression analysis.

All statistical analyses were performed using the statistical software package Stata version 15.1, except the multilevel regression analysis, for which the statistical package SAS version 9.2 was used.

Results

In total 100,583 children were eligible for this study out of the 156,181 invited to participate in COSI round 4 in 22 European countries. Turkmenistan had the highest child participation rate (96.7%) and Ireland the lowest (56.6%). As expected, the average family participation rate was lower (78.8%) than the average child participation rate (85.1%), and was highest in Italy and Turkmenistan (around 95%) and lowest in Denmark (29.9%) (Table 1). As shown in Table 1, the number of children invited to participate varied between countries due to differences in the number of targeted age groups and, to a lesser extent, differences between the school systems through which the children were enrolled. In Italy, the sample size was considerably higher because the country decided to produce estimates at subnational level and not only at national level. The sample size, the level of participation in the survey, the level of availability of data on breastfeeding practices, the percentage of family record forms filled in by the mothers and the percentage of children belonging to the 6- to 9-year age groups were factors that influenced the final number of children included in the analysis.

Table 1.

Child participation rates and rates of completed family record forms in COSI/WHO Europe round 4 by country

| Country a | Children invited to participate |

Measured 6- to 9-year-old children with the family record form filled in, n | Children included in the analysis b, n | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| total number | proportion who participated in measurements ”, % | proportion whose family record form was filled in c, % | |||

| ALB | 7,113 | 91.8 | 36.2 | 2,527 | 1,624 |

| BUL | 4,090 | 83.7 | 83.1 | 3,400 | 2,945 |

| CRO d | 7,220 | 78.6 | 76.0 | 2,651 | 2,222 |

| CZH | NA | NA | NA | 1,406 | 1,368 |

| DEN | 3,202 | 84.6 | 29.9 | 957 | 805 |

| FRA | 7,094 | 76.8 | 75.6 | 5,318 | 5,183 |

| GEO | 4,143 | 80.7 | 78.4 | 3,246 | 2,876 |

| IRE | 2,704 | 56.6 | 32.4 | 874 | 748 |

| ITA | 50,902 | 90.2 | 95.2 | 44,020 | 37,359 |

| KAZ | 6,026 | 92.7 | 82.3 | 4,311 | 3,490 |

| LVA | 8,143 | 80.4 | 71.5 | 3,550 | 5,206 |

| LTU | NA | NA | NA | 5,707 | 3,150 |

| MAT | 4,329 | 91.8 | 73.4 | 3,179 | 3,064 |

| MNE | 4,094 | 84.1 | 66.8 | 2,736 | 2,084 |

| POL | 3,828 | 89.0 | 76.9 | 2,945 | 2,648 |

| POR | 7,475 | 92.1 | 85.6 | 6,391 | 5,321 |

| ROM | 9,094 | 83.7 | 73.6 | 6,610 | 5,156 |

| RUS | 3,900 | 77.7 | 52.6 | 2,052 | 1,854 |

| SMR | 329 | 95.1 | 93.6 | 306 | 257 |

| SPA | 14,908 | 73.1 | 70.1 | 10,453 | 8,349 |

| TJK | 3,502 | 94.7 | 93.5 | 3,270 | 1,935 |

| TKM | 4,085 | 96.7 | 95.3 | 3,891 | 2,939 |

| Total | 156,181 | 85.1 | 78.8 | 119,800 | 100,583 |

Figures refer to primary school children from: Albania (ALB); Bulgaria (BUL); Croatia (CRO); Czechia (CZH); Denmark (DEN); France (FRA); Georgia (GEO); Ireland (IRE); Italy (ITA); Kazakhstan (KAZ); Latvia (LVA); Lithuania (LTU); Malta (MAT); Montenegro (MNE); Poland (POL); Portugal (POR); Romania (ROM); Moscow city (RUS); San Marino (SMR); Spain (SPA); Tajikistan (TJK); and Turkmenistan (TKM).

All children with complete information on sex, whose age was between 6 and 9 years, whose weight and height were measured, whose BMI/A z-scores were within the normal range (>-5 to <+5), whose mothers had filled in the family record form and with complete information about breastfeeding practice.

Total figures were calculated including only countries with available information about the number of children invited to participate in the surveillance.

For Croatia, only data on 8-year-olds were available for comparison at the European level. Children ' s and families ' participation in the survey was calculated for the whole sample (not only 8-year-olds).

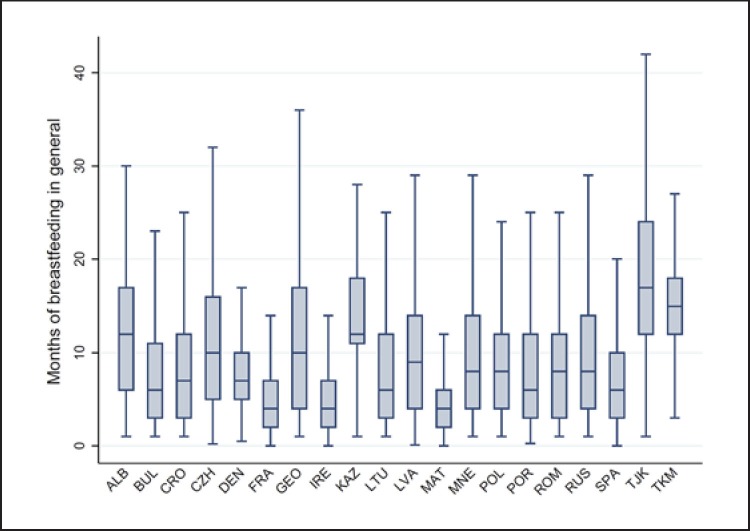

The distribution of the children by characteristics at birth and breastfeeding practice (general and exclusive) was estimated for each country, and the results are presented in Table 2. Malta had the highest percentage of children with low birth weight (10.2%) and Ireland the highest percentage of children with high birth weight (19.2%) and also the highest percentage of children who have never been breastfed (46.2%). Tajikistan had the highest percentage of children that were breastfed for 6 months and more (94.4%) or exclusively breastfed for 6 months and more (73.3%), whereas in France, Ireland and Malta only around 1 in 4 children was breastfed for at least 6 months. The COSI data showed considerable heterogeneity in breastfeeding practices, as confirmed by Figure 2, which illustrates the country-specific distribution of general breastfeeding duration in months.

Table 2.

Characteristics at birth and breastfeeding practice of the study population, by country, COSI round 4 (2015/2017)

| Country | Male, % | Median age (Q1-Q3), years | Characteristics at birth |

Breastfeeding practice |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| full-term birth, % | birth weight, % |

duration of any breastfeeding, % |

duration of exclusive breastfeeding, % |

||||||||||

| <2,500 g | 2,5004,000 g | >4,000 g | never | <6 months | >6 months | never | <6 months | >6 months | unknown | ||||

| ALB | 51.2 | 8.5 (8.0-9.0) | 96.2 | 6.2 | 86.2 | 7.6 | 5.2 | 15.1 | 79.7 | - | - | - | |

| BUL | 51.0 | 7.6 (7.4-7.8) | 90.5 | 6.2 | 88.6 | 5.2 | 17.1 | 37.3 | 45.6 | 28.1 | 47.6 | 17.0 | 7.3 |

| CRO | 51.8 | 8.5 (8.2-8.8) | 91.0 | 3.7 | 83.7 | 12.6 | 10.0 | 33.8 | 56.2 | - | - | - | - |

| CZH | 50.7 | 7.0 (6.9-7.1) | 79.7 | 6.8 | 86.2 | 7.0 | 7.1 | 25.6 | 67.3 | - | - | - | - |

| DEN | 52.9 | 7.2 (7.0-7.4) | 86.6 | - | - | - | 10.8 | 27.5 | 61.7 | - | - | - | - |

| FRA | 50.3 | 8.2 (7.6-8.6) | 86.2 | 7.8 | 85.2 | 7.0 | 33.7 | 39.9 | 26.4 | - | - | - | - |

| GEO | 50.7 | 7.6 (7.3-7.9) | 93.5 | 4.5 | 86.7 | 8.8 | 13.1 | 26.7 | 60.2 | 14.5 | 42.3 | 34.6 | 8.6 |

| IRE | 54.0 | 7.1 (6.8-7.4) | 92.4 | 4.6 | 76.2 | 19.2 | 46.2 | 31.2 | 22.6 | 50.1 | 37.7 | 10.5 | 1.7 |

| ITA | 51.2 | 8.8 (8.6-9.0) | 85.4 | 7.5 | 87.1 | 5.4 | 10.2 a | 47.5 a | 42.3 a | - | - | - | - |

| KAZ | 49.4 | 9.0 (8.6-9.5) | 95.9 | 4.1 | 89.7 | 6.1 | 5.7 | 5.8 | 88.5 | 5.7 | 12.0 | 50.7 | 31.6 |

| LTU | 49.8 | 7.8 (7.6-8.1) | 91.5 | 4.1 | 79.9 | 16.0 | 13.4 | 39.1 | 47.5 | 15.2 | 58.8 | 22.3 | 3.7 |

| LVA | 47.7 | 8.0 (7.3-9.3) | 94.1 | 3.9 | 81.3 | 14.8 | 7.6 | 30.4 | 62.0 | 9.5 | 46.5 | 22.7 | 21.3 |

| MAT | 49.6 | 7.8 (7.5-8.1) | 91.1 | 10.2 | 84.5 | 5.3 | 35.2 | 40.2 | 24.6 | - | - | - | - |

| MNE | 51.9 | 7.4 (6.9-7.9) | 93.3 | 4.9 | 82.3 | 12.8 | 13.0 | 27.6 | 59.4 | - | - | - | - |

| POL | 49.8 | 8.4 (8.2-8.7) | 89.4 | 6.0 | 82.9 | 11.1 | 13.3 | 28.6 | 58.1 | 15.8 | 52.6 | 16.9 | 14.7 |

| POR | 50.3 | 7.5 (7.0-8.0) | 89.7 | 9.1 | 86.2 | 4.7 | 12.9 | 35.4 | 51.7 | 16.8 | 55.0 | 21.0 | 7.2 |

| ROM | 48.4 | 8.5 (7.9-9.0) | 92.6 | 7.1 | 87.5 | 5.4 | 10.3 | 33.8 | 55.9 | - | - | - | - |

| RUS | 49.9 | 7.4 (7.1-7.7) | 93.6 | 4.8 | 85.0 | 10.2 | 10.3 | 29.5 | 60.2 | 16.0 | 49.1 | 25.5 | 9.4 |

| SMR | 46.3 | 8.8 (8.6-9.0) | 87.9 | 7.1 | 83.1 | 9.8 | 8.6 a | 31.1 a | 60.3 a | - | - | - | - |

| SPA | 50.6 | 8.0 (7.0-9.0) | 83.9 | 8.5 | 86.4 | 5.1 | 22.5 | 34.2 | 43.3 | 22.7 | 45.4 | 21.8 | 10.1 |

| TJK | 50.5 | 7.4 (7.2-7.6) | 96.7 | 6.8 | 88.1 | 5.1 | 2.5 | 3.1 | 94.4 | 2.5 | 15.0 | 73.3 | 9.2 |

| TKM | 49.2 | 7.7 (7.5-8.0) | 97.7 | 4.6 | 89.6 | 5.8 | 2.7 | 3.6 | 93.7 | 2.7 | 27.7 | 56.9 | 12.7 |

For an explanation of the country abbreviations, see Table 1. Q1, first quartile; Q3, third quartile.

For Italy and San Marino, the figures about breastfeeding duration refer to the following categories: “ never, ” “ up to 6 months ” and “ more than 6 months. ”

Fig. 2.

Box plot of duration of breastfeeding among children aged 6–9 years by country. COSI round 4 (2015/2017).

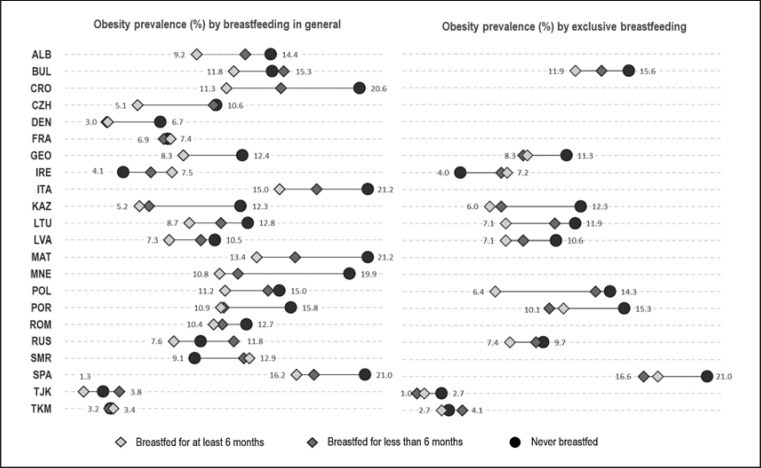

The prevalence of obesity among children aged 6–9 years – by breastfeeding practice and by country – is represented in Figure 3. Among the 22 countries in the study, the highest prevalence of overall obesity was observed in Spain (17.7%), followed by Malta (17.2%) and Italy (16.8%). Italy and Malta showed the highest prevalence of obesity among children who have never been breastfed (21.2%), followed by Spain (21.0%). Except for France, Ireland and San Marino, all countries showed a higher prevalence of obesity among children who had never been breastfed and/or had been breastfed less than 6 months than among those who were breastfed for more than 6 months. Of the 22 countries, 13 countries showed statistically significant differences in obesity prevalence between breastfeeding duration categories. Country-specific prevalence values for obesity by breastfeeding practice (general and exclusive) with their 95% CIs are provided in online supplementary Table 1 (for all online suppl. material, see www.karger.com/doi/10.1159/000500425).

Fig. 3.

Prevalence of obesity among children aged 6–9 years, by breastfeeding duration and country. COSI round 4 (2015/2017).

Table 3 illustrates the results of the multivariate multilevel logistic regression analysis regarding breastfeeding practice (both general and exclusive) and characteristics at birth. As for breastfeeding in general, the pooled analysis, which included 16 countries and 29,245 children, found a protective effect: compared to children who were breastfed for 6 months, children's odds of being obese were highly increased if they were never breastfed (adjOR: 1.22; 95% CI: 1.16–1.28) or breastfed for a shorter period (adjOR: 1.12; 95% CI: 1.07–1.16). Similar figures arose also for exclusive breastfeeding based on data from 8 countries (15,371 children). At the country level, the stratified multivariate regression analysis confirmed the results of the pooled bivariate analysis. Six countries, i.e. Croatia (adjOR: 1.62; 95% CI: 1.07–2.44), Georgia (adjOR: 1.53; 95% CI: 1.02–2.30), Italy (adjOR: 1.21; 95% CI: 1.10–1.35), Malta (adjOR: 1.69; 95% CI: 1.23–2.33), Montenegro (adjOR: 1.90; 95% CI: 1.26–2.33) and Spain (adjOR: 1.25; 95% CI: 1.06–1.48), showed that having never been breastfeed was associated with a higher risk of being obese, compared to having been breastfed for at least 6 months. Albania, Kazakhstan and Portugal presented similar figures, even if the differences did not reach statistical significance at the 0.05 level. General breastfeeding for at least 6 months had a protective effect compared to a shorter duration of breastfeeding in Croatia (adjOR: 1.38; 95% CI: 1.04–1.83), Malta (adjOR: 1.36; 95% CI: 1.00–1.85) and Poland (adjOR: 1.46; 95% CI: 1.09–1.96). As for exclusive breastfeeding, the data showed a tendency towards having a higher risk of obesity among children never exclusively breastfed compared to those exclusively breastfed for at least 6 months in 3 countries (Albania, Lithuania and Portugal), while in Poland children not exclusively breastfed at all and those breastfed for less than 6 months were, respectively, 1.86 and 1.99 times more likely to be obese (95% CIs: 1.11–3.10 and 1.30–3.06, respectively).

Table 3.

Adjusted ORs (adjORs) of being obese (compared to not being obese) related to breastfeeding duration and characteristics at birth, by country, COSI round 4 (2015/2017)

| AdjOR (95% CI) of being obese - breastfeeding in general and characteristics at birth |

AdjOR (95% CI) of being obese - exclusive breastfeeding |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | breastfeeding in general (reference = breastfed for >6 months) |

preterm vs. full-term (reference = full-term) | birth weight (reference = 2,500-4,000 g) |

n | exclusive breastfeeding (reference = breastfed for >6 months) |

||||

| never breastfed | <6 months of breastfeeding | <2,500 g (low birth weight) |

>4,000 g (high birth weight) |

never exclusively breastfed | <6 months of exclusive breastfeeding | ||||

| Country-specific models | |||||||||

| ALB | 1,395 | 2.10 (0.98-4.51) | 1.39 (0.84-2.30) | 0.57 (0.17-1.86) | 1.00 (0.39-2.61) | 1.66 (0.89-3.07) | - | ||

| BUL | 2,750 | 1.19 (0.86-1.66) | 1.27 (0.99-1.63) | 1.59 (1.07-2.35) | 0.52 (0.29-0.92) | 1.82 (1.21-2.76) | 2,507 | 1.31 (0.92-1.88) | 1.17 (0.84-1.64) |

| CRO | 2,107 | 1.62 (1.07-2.44) | 1.38 (1.04-1.83) | 1.60 (1.05-2.42) | 1.55 (0.84-2.85) | 1.68 (1.19-2.38) | - | ||

| CZH | 1,150 | 1.30 (0.50-3.39) | 1.39 (0.80-2.41) | 0.96 (0.50-1.85) | 0.69 (0.21-2.21) | 0.81 (0.30-2.19) | - | ||

| FRA | 4,188 | 0.88 (0.63-1.25) | 0.99 (0.72-1.36) | 2.14 (1,51-3.04) | 0.55 (0.32-0.96) | 1.09 (0.69-1.72) | - | ||

| GEO | 2,472 | 1.53 (1.02-2.30) | 1.15 (0.82-1.61) | 0.74 (0.39-1.44) | 0.51 (0.20-1.29) | 1.16 (0.73-1.84) | 2,273 | 1.36 (0.88-2.10) | 1.08 (0.77-1.51) |

| IRE | 721 | 0.38 (0.16-0.90) | 0.72 (0.31-1.64) | 1.57 (0.35-7.11) | 0.33 (0.03-4.18) | 1.77 (0.86-3.65) | 708 | 0.50 (0.17-1.47) | 1.08 (0.38-3.04) |

| ITA | 34,700 | 1.21 (1.10-1.35) | 1.02 (0.95-1.09) | 1.24 (1.14-1.36) | 0.81 (0.72-0.93) | 1.49 (1.32-1.68) | - | ||

| KAZ | 2,967 | 1.78 (0.98-3.50) | 0.97 (0.52-1.83) | 0.65 (0.24-1.79) | 0.99 (0.38-2.57) | 1.79 (1.05-3.04) | 2,332 | 1.46 (0.78-2.71) | 1.03 (0.65-1.64) |

| LTU | 2,939 | 1.33 (0.92-1.93) | 1.18 (0.89-1.56) | 1.07 (0.66-1.74) | 0.40 (0.16-1.06) | 1.39 (1.02-1.89) | 2,841 | 1.46 (0.95-2.24) | 1.37 (0.98-1.93) |

| LVA | 4,872 | 1.18 (0.80-1.74) | 1.15 (0.91-1.45) | 0.97 (0.58-1.61) | 0.66 (0.33-1.32) | 1.05 (0.79-1.40) | 3,847 | 1.24 (0.83-1.85) | 1.09 (0.82-1.45) |

| MAT | 2,317 | 1.69 (1.23-2.33) | 1.36 (1.00-1.85) | 0.94 (0.60-1.16) | 0.76 (0.50-1.18) | 1.65 (1.08-2.54) | - | ||

| MNE | 1,816 | 1.90 (1.26-2.87) | 1.18 (0.84-1.07) | 1.63 (0.93-2.89) | 0.80 (0.37-1.71) | 1.15 (0.77-1.73) | - | ||

| POL | 2,393 | 1.24 (0.84-1.83) | 1.46 (1.09-1.96) | 1.60 (1.04-2.46) | 0.46 (0.23-0.93) | 1.56 (1.09-2.13) | 2,062 | 1.86 (1.11-3.10) | 1.99 (1.30-3.06) |

| POR | 4,807 | 1.27 (0.98-1.66) | 0.93 (0.77-1.16) | 1.15 (0.82-1.61) | 0.56 (0.37-0.86) | 1.82 (1.27-2.60) | 4,508 | 1.26 (0.94-1.68) | 0.87 (0.69-1.11) |

| ROM | 4,639 | 1.23 (0.90-1.69) | 1.02 (0.82-1.26) | 1.71 (1.17-2.51) | 0.56 (0.34-0.91) | 1.52 (1.07-2.18) | - | ||

| SPA | 7,123 | 1.25 (1.06-1.48) | 1.00 (0.86-1.17) | 1.16 (0.97-1.39) | 1.01 (0.80-1.29) | 1.34 (1.02-1.76) | 6,393 | 1.11 (0.92-1.35) | 0.88 (0.74-1.04) |

| TKM | 2,377 | 1.07 (0.27-4.19) | 0.82 (0.24-2.74) | 2.09 (0.37-11.24) | 1.11 (0.26-4.81) | 2.52 (1.24-5.10) | - | ||

| | |||||||||

| Pooled model | |||||||||

| 29,245 | 1.22 (1.16-1.28) | 1.12 (1.07-1.16) | 1.50 (1.42-1.59) | 0.65 (0.60-0.71) | 1.09 (1.02-1.16) | 15,371 | 1.25 (1.17-1.36) | 1.05 (0.99-1.12) | |

For an explanation of the country abbreviations, see Table 1. As for country-specific analysis, the adjORs were estimated through multilevel logistic models with random effects for the primary sampling unit, while for the overall analysis, multilevel logistic models with random effects for countries were calculated. The models included the child ' s sex and age, maternal education and weight status, region of residence, the child ' s characteristics at birth (full-term birth; weight at birth) and breastfeeding in general/exclusive breastfeeding as covariates. The pooled model with general breastfeeding among the covariates was obtained including children from the following countries and age groups: 7-year-olds from Bulgaria, Czechia, Georgia, Latvia, Lithuania, Malta, Montenegro, Portugal, Spain and Turkmenistan; 8-year-olds from Albania, Croatia, France, Poland and Romania; and 9-year-olds from Kazakhstan. The pooled model with exclusive breastfeeding among the covariates was obtained including children from the following countries and age groups: 7-year-olds from Bulgaria, Georgia, Latvia, Lithuania, Portugal and Spain; 8-year-olds from Poland; and 9-year-olds from Kazakhstan.

Regarding the association between obesity and characteristics at birth, the pooled analysis revealed higher odds of being obese in case of preterm birth (adjOR: 1.50; 95% CI: 1.42–1.59). A low birth weight was associated with a lower risk of being obese (adjOR: 0.65; 95% CI: 0.60–0.71), while a high birth weight was associated with a slightly greater risk (adjOR: 1.09; 95% CI: 1.02–1.16).

At the country level, 6 countries showed that children who were preterm at birth had a higher risk of being obese, compared to children who were full-term babies (Bulgaria [adjOR: 1.59; 95% CI: 1.07–2.35], Croatia [adjOR: 1.60; 95% CI: 1.05–2.42], France [OR: 2.14; 95% CI: 1.51–3.04], Italy [OR: 1.24; 95% CI: 1.14–1.36], Poland [adjOR: 1.60; 95% CI: 1.04–2.46] and Romania [OR: 1.71; 95% CI: 1.17–2.51]). Low-birth-weight children were less likely to be obese in 6 countries (Bulgaria, France, Italy, Poland, Portugal and Romania) with adjOR values ranging from 0.46 to 0.81. In contrast, in 11 of the 22 countries, high birth weight was associated with elevated odds of being obese (adjOR values ranging from 1.34 in Spain to 2.52 in Turkmenistan).

Discussion and Conclusion

This study presents a collection of comparable data from 22 countries in the WHO European Region on characteristics at birth, breastfeeding practices (general and exclusive) and risk of childhood obesity. Our analyses showed that in nearly all countries, more than 77% of children were breastfed, but there were exceptions, i.e. Ireland, France and Malta, where 46.2, 37.7 and 35.2% of children, respectively, were never breastfed. Despite the consistent flow of research evidence showing the health benefits from breastfeeding, along with numerous policy initiatives aimed at promoting optimal breastfeeding practices, adoption of exclusive breastfeeding remains below global recommendations [13]. In agreement with previous data from this WHO Region [19], these findings confirmed that only 4 out of 12 countries had a ≥25% prevalence of exclusive breastfeeding (for ≥6 months), namely Georgia (34.6%), Kazakhstan (50.7%), Turkmenistan (56.9%) and Tajikistan (73.3%).

A higher prevalence of obesity was observed among all children who were never breastfed and/or were breastfed less than 6 months compared to those who were breastfed more than 6 months, except in France and Ireland. Breastfed children had a statistically significantly lower risk of obesity than children who were never breastfed or were breastfed for a shorter period.

The Mediterranean countries have some of the highest prevalence rates of obesity (>16%). Our study showed that children from Spain, Malta, Italy, Croatia, Georgia and Montenegro who had never been breastfeed had a higher chance of being obese than those who were breastfed for at least 6 months.

Overall, our findings on breastfeeding practices confirm the results from earlier studies [8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 14, 19, 42]; there are slow improvements in breastfeeding practices, low proportions of exclusive breastfeeding (both under 6 months and at 6 months of age) and wide between-country disparities in breastfeeding prevalence rates. Indeed, some of the differences between countries are striking. The high prevalence of long general breastfeeding in countries from Central Asia (Fig. 2; Table 2) such as Kazakhstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan and Georgia might be explained by strong action at the country level, notably support by health professionals and other initiatives known to be critical for breastfeeding promotion and protection.

Exclusive breastfeeding prevents the early introduction of complementary foods that could lead to excessive weight gain. Some studies have shown that protein and total energy intake are lower among breastfed children relative to formula-fed ones [43, 44]. Additionally, evidence shows that formula-fed children, in general, have an increased body weight [45], which suggests that both higher protein intake [46] and weight gain [47] in an early period of life are positively associated with being obese later in childhood. Formula-fed infants showed higher plasma levels of insulin than breastfed children, which can stimulate fat deposition and early development of adipocytes [48]. Breast milk acts in the regulation of food intake and energy balance due to the hormones and biological factors that it contains, which may help shape long-term physiological processes responsible for maintaining energy balance [49]. By promoting healthy weight gain during infancy, breastfeeding might assist in “programming” an individual to have a lower risk of being overweight or obese later in life [50].

Considering that promoting breastfeeding presents a “window of opportunity” for obesity prevention policy to respond to the problem of childhood obesity in Europe [51], the existence of national policies for promoting breastfeeding practices, and how these policies are developed, can lead some countries to being more or less successful. In general, breastfeeding practices in Europe fall short of WHO recommendations, due to inefficient policies for encouraging breastfeeding; lack of preparation of health professionals to support breastfeeding; intensive marketing of breast milk substitutes; and problems in legislation on maternity protection, among others [42].

In 2012, WHO Member States adopted the Global Strategy for Infant and Young Child Feeding, which demands comprehensive national policies that promote, protect and support infant and young child feeding (IYCF) practices [13]. This Global Strategy includes many components that play an important role in increasing the prevalence of breastfeeding: the International Code of Marketing of Breastmilk Substitutes [49], the Innocenti Declaration [50], the Baby Friendly Hospitals Initiative [52], the WHO Maternal, Infant and Young Child Nutrition Implementation Plan [53] and the World Health Assembly Global Targets for Nutrition 2025 [22]. Furthermore, the WHO European Food and Nutrition Action Plan 2015–2020 highlights the importance of promoting the gains of a healthy diet throughout life, especially for the most vulnerable, making breastfeeding one of its main priorities [54].

Despite these commitments, and global recommendations being strongly supported by international communities, organizations and scientists, and the promotion, protection and support of breastfeeding becoming a public health priority [55], data from a previous publication [19] showed that 9 countries out of the 22 from our study (Albania, Bulgaria, Croatia, Italy, Kazakhstan, Lithuania, Latvia, Romania and the Russian Federation [Moscow City]) reported having a national breastfeeding policy on IYCF or a nutrition policy. Czechia, France, Ireland, Malta, Portugal and Spain did not have any policies that included IYCF at that time of the study. In addition, the Russian Federation, Poland, Czechia, Romania, Italy and Croatia were the countries with the highest numbers of baby-friendly hospitals (287, 89, 58, 30, 24 and 21, respectively). Bagci Bosi et al. [19] also underlined that Europe still lacks a common strategy for the monitoring of breastfeeding practices, and therefore interpretations and comparisons should be made with caution. Nevertheless, the presence of such initiatives appears to positively affect the prevalence of breastfeeding; national policies that promote IYCF practices and a high quantity of baby-friendly hospitals were found in those countries with higher proportions of breastfeeding until 6 months of age or more, particularly in Latvia, the Russian Federation (Moscow City), Croatia and Romania.

Analysis of other characteristics at birth in this study revealed that a high birth weight was also associated with a higher risk of being overweight, which was reported in 11 of the 22 countries, and higher odds of being obese were also observed in cases of premature birth. The data from Bulgaria, Croatia, France, Italy, Poland and Romania showed that children who were preterm at birth had a higher risk of being obese, compared to children who were full-term babies. These results are consistent with those of previous cohort studies that showed high birth weight to be associated with being overweight during childhood [23, 29, 56, 57]. The relationship between high birth weight and later obesity might be explained by disturbances during critical periods of development (such as intrauterine growth and infancy), which may cause permanent metabolic, physiological and structural adaptations [29]. Other related factors include gestational overnutrition, maternal diabetes mellitus, maternal obesity, excessive maternal weight gain and prolonged gestation, which increase the risk of later obesity [28, 58] and have also been related to premature delivery. In a study which included more than 1 million women from 84 studies [59], analysis confirmed that overweight and obese women had a higher risk of delivering prior to 32 weeks of gestation and had a higher risk of induced delivery before 37 weeks; also, being overweight or obese was associated with a 30% increased risk of early delivery [59].

Strengths and Limitations

The use of systematic, nationally representative data makes these findings important for monitoring the progression of breastfeeding practices and other birth characteristics, relevant to the study of childhood obesity. Additionally, a strength of this study is its large sample size (100,583 schoolchildren). A large sample size is more representative of the population, limiting the influence of outliers or extreme observations. Moreover, a large sample size increases the likelihood that the results are truly indicative of the phenomena in a population. However, this study is not without its limitations. Firstly, there was no information about the maternal BMI at the time of her child's birth, which has been shown to be amongst the determinants of birth outcomes and childhood overweight, reflecting the contributions of shared genes and the environment [60]. Secondly, the data come from cross-sectional studies, which can detect an association between exposure and outcome but do not justify causal inference. Furthermore, although many variables were used to adjust the models, it is impossible to rule out residual confounding by other unmeasured or unmeasurable confounders. Lastly, the fact that the study used recalled data on breastfeeding increased the chance of memory bias.

Conclusions

The present work confirms the beneficial effect of breastfeeding with regard to the odds of becoming obese – which was statistically significantly increased if children were never breastfed or breastfed for less than 6 months. Nevertheless, adoption of exclusive breastfeeding is below global recommendations [13] and far from the target of increasing the prevalence of exclusive breastfeeding in the first 6 months up to at least 50% by 2025, a goal endorsed by the WHO Member States at the World Health Assembly Global Targets for Nutrition [22].

Up-to-date information on breastfeeding and other characteristics at birth that might be associated with overweight and obesity is essential for tracking progress in countries. Also, it is recommended that alignment and harmonization of breastfeeding indicators be taken forward in Member States of the WHO European Region. The massive amount of information now available through the WHO/Europe COSI study allows the systematic identification of challenges, as well as monitoring and fine-tuning of the policy actions around the important public health issue of childhood obesity and later non-communicable diseases.

Statement of Ethics

The WHO COSI study protocol was approved by the International Ethical Guidelines for Biomedical Research Involving Human Subjects, and all procedures were also approved by local Ethics Committees in each country. Furthermore, the children's parents or guardians have given their written informed consent.

Disclosure Statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses or interpretation of the data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

The writing group takes sole responsibility for the content of this article, and the content of this article reflects the views of the authors only. J.B. and J.W. are staff members of the WHO, and M.B. is a WHO consultant. The WHO is not liable for any use that may be made of the information contained therein.

Funding Sources

The authors gratefully acknowledge support from a grant from the Russian Government in the context of the WHO European Office for the Prevention and Control of NCDs.

Data collection in the countries was made possible through funding from: Albania: WHO through the Joint Programme on Children, Food Security and Nutrition “Reducing Malnutrition in Children,” funded by the Millennium Development Goals Achievement Fund, and the Institute of Public Health; Bulgaria: Ministry of Health, National Center of Public Health and Analyses, WHO Regional Office for Europe; Croatia: Ministry of Health, Croatian Institute of Public Health and WHO Regional Office for Europe; Czechia: grants AZV MZČR 17-31670 A and MZČR – RVO EÚ 00023761; Denmark: Danish Ministry of Health; France: French Public Health Agency; Georgia: WHO; Ireland: Health Service Executive; Italy: Ministry of Health; Istituto Superiore di Sanità (National Institute of Health); Kazakhstan: Ministry of Health of the Republic of Kazakhstan and WHO Country Office; Latvia: n/a; Lithuania: Science Foundation of Lithuanian University of Health Sciences and Lithuanian Science Council and WHO; Malta: Ministry of Health; Montenegro: WHO and Institute of Public Health of Montenegro; Poland: National Health Programme, Ministry of Health; Portugal: Ministry of Health Institutions, the National Institute of Health, Directorate General of Health, Regional Health Directorates and the kind technical support from the Center for Studies and Research on Social Dynamics and Health (CEIDSS); Romania: Ministry of Health; Russian Federation (Moscow City): n/a; San Marino: Health Ministry, Educational Ministry, Social Security Institute and Health Authority; Spain: Spanish Agency for Food Safety and Nutrition (AESAN); Tajikistan: n/a; Turkmenistan: WHO Country Office in Turkmenistan and Ministry of Health.

Author Contributions

A.I.R. collected the data in Portugal, conceptualized the study, drafted the manuscript, analysed and interpreted the results, and wrote the manuscript; M.B. contributed to data presentation, conducted all analyses, drafted the manuscript and made substantial contributions to the interpretation of the results; A.S., B.S., M.K., T.H., M.G.S., A.F., L.S., J.H., C.K., V.D., S.M.M., V.F.S., S.A., E.K., V.P., A.G., I.P., A.P., M.T., R.S. and C.H.-P. contributed to data collection and data cleaning, and critically reviewed the manuscript; and J.W., W.A. and J.B. substantially contributed to the revision of the manuscript. All authors contributed to and approved the final manuscript.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary data

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge all participating children, their parents, and the school teachers and principals for kindly volunteering to participate in the study. We also thank the examiners and regional and local supervisors/coordinators who collected the data in each country. Furthermore, we would like to acknowledge the contribution of other researchers and/or principal investigators in this study, namely: Quenia Santos, consultant at the WHO Regional Office for Europe; Radka Taxova Braunerova from the Obesity Management Centre – Institute of Endocrinology, Czechia; Paola Nardone from the Istituto Superiore di Sanità, Italy; Boban Mugoša from the Institute of Public Health of Montenegro and Natasa Terzic from the Center for Health System Development – Institute of Public Health of Montenegro; Alexandra Cucu from the Department of Public Health and Management of the University of Medicine and Pharmacy, Romania; Elena Sacchini from the Health Authority San Marino; María Ángeles Dal Re Saavedra from the Spanish Agency for Food Safety & Nutrition (AESAN); Mukhtarova Parvina from the Ministry of Health and Social Protection of Population of the Republic of Tajikistan; and Guljemal Ovezmyradova and Laura Vremis from the WHO Country Office in Turkmenistan.

References

- 1.Childhood Obesity Surveillance Initiative - Factsheet . Copenhagen: World Health Organization Regional Office for Europe; 2018. Highlights 2015-17. [Google Scholar]

- 2.WHO European Childhood Obesity Surveillance Initiative: overweight and obesity among 6–9 year old children- Report of the third round of data collection 2012-2013 . Copenhagen: World Health Organization Regional Office for Europe; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wijnhoven TM, van Raaij JM, Spinelli A, Starc G, Hassapidou M, Spiroski I, et al. WHO European Childhood Obesity Surveillance Initiative: body mass index and level of overweight among 6-9-year-old children from school year 2007/2008 to school year 2009/2010. BMC Public Health. 2014 Aug;14((1)):806. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-14-806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Abarca-Gómez L, Abdeen ZA, Hamid ZA, Abu-Rmeileh NM, Acosta-Cazares B, Acuin C, et al. NCD Risk Factor Collaboration (NCD-RisC) Worldwide trends in body-mass index, underweight, overweight, and obesity from 1975 to 2016: a pooled analysis of 2416 population-based measurement studies in 128·9 million children, adolescents, and adults. Lancet. 2017 Dec;390((10113)):2627–42. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)32129-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Report of the commission on ending childhood obesity: World Health Organization 2016.

- 6.Pietrobelli A, Agosti M, MeNu Group Nutrition in the First 1000 Days: Ten Practices to Minimize Obesity Emerging from Published Science. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2017 Dec;14((12)):E1491. doi: 10.3390/ijerph14121491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Woo Baidal JA, Locks LM, Cheng ER, Blake-Lamb TL, Perkins ME, Taveras EM. Risk Factors for Childhood Obesity in the First 1,000 Days: A Systematic Review. Am J Prev Med. 2016 Jun;50((6)):761–79. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2015.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Marseglia L, Manti S, D'Angelo G, Cuppari C, Salpietro V, Filippelli M, et al. Obesity and breastfeeding: the strength of association. Women Birth. 2015 Jun;28((2)):81–6. doi: 10.1016/j.wombi.2014.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Horta BL, Loret de Mola C, Victora CG. Long-term consequences of breastfeeding on cholesterol, obesity, systolic blood pressure and type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Acta paediatrica (Oslo, Norway: 1992) 2015;104((467)):30–37. doi: 10.1111/apa.13133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Victora CG, Bahl R, Barros AJ, França GV, Horton S, Krasevec J, et al. Lancet Breastfeeding Series Group Breastfeeding in the 21st century: epidemiology, mechanisms, and lifelong effect. Lancet. 2016 Jan;387((10017)):475–90. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)01024-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Spatz DL. Preventing obesity starts with breastfeeding. J Perinat Neonatal Nurs. 2014 Jan-Mar;28((1)):41–50. doi: 10.1097/JPN.0000000000000009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Harder T, Bergmann R, Kallischnigg G, Plagemann A. Duration of breastfeeding and risk of overweight: a meta-analysis. Am J Epidemiol. 2005 Sep;162((5)):397–403. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwi222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Global Strategy for Infant and Young Child Feeding . Geneva: World Health Organization UNICEF; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Horta BL, Victora CG. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2013. Long-term effects of breastfeeding - A Systematic Review. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mosca F, Gianni ML. Human milk: composition and health benefits. La Pediatria medica e chirurgica: Medical and surgical pediatrics. 2017;39((2)):155. doi: 10.4081/pmc.2017.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Eidelman AI, Schanler RJ, Section on Breastfeeding Breastfeeding and the use of human milk. Pediatrics. 2012 Mar;129((3)):e827–41. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-3552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Spatz DL, Lessen R. Risks of Not Breastfeeding. International Lactation Consultant Association. 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 18.Oddy WH, Smith GJ, Jacoby P. A possible strategy for developing a model to account for attrition bias in a longitudinal cohort to investigate associations between exclusive breastfeeding and overweight and obesity at 20 years. Ann Nutr Metab. 2014;65((2-3)):234–5. doi: 10.1159/000360548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bagci Bosi AT, Eriksen KG, Sobko T, Wijnhoven TM, Breda J. Breastfeeding practices and policies in WHO European Region Member States. Public Health Nutr. 2016 Mar;19((4)):753–64. doi: 10.1017/S1368980015001767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.WHO. World Health Statistics 2013 Geneva: World Health Organization. 2013.

- 21.Infant and young child feeding: World Health Organization 2018 [Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/infant-and-young-child-feeding. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Global Targets 2025 To improve maternal, infant and young child nutrition: World Health Organization. 2014 [Available from: https://www.who.int/nutrition/topics/nutrition_globaltargets2025/en/ [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kang M, Yoo JE, Kim K, Choi S, Park SM. Associations between birth weight, obesity, fat mass and lean mass in Korean adolescents: the Fifth Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. BMJ Open. 2018 Feb;8((2)):e018039. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-018039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Glavin K, Roelants M, Strand BH, Júlíusson PB, Lie KK, Helseth S, et al. Important periods of weight development in childhood: a population-based longitudinal study. BMC Public Health. 2014 Feb;14((1)):160. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-14-160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rooney BL, Mathiason MA, Schauberger CW. Predictors of obesity in childhood, adolescence, and adulthood in a birth cohort. Matern Child Health J. 2011 Nov;15((8)):1166–75. doi: 10.1007/s10995-010-0689-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vasylyeva TL, Barche A, Chennasamudram SP, Sheehan C, Singh R, Okogbo ME. Obesity in prematurely born children and adolescents: follow up in pediatric clinic. Nutr J. 2013 Nov;12((1)):150. doi: 10.1186/1475-2891-12-150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yu ZB, Han SP, Zhu GZ, Zhu C, Wang XJ, Cao XG, et al. Birth weight and subsequent risk of obesity: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes Rev. 2011 Jul;12((7)):525–42. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2011.00867.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhao Y, Wang SF, Mu M, Sheng J. Birth weight and overweight/obesity in adults: a meta-analysis. Eur J Pediatr. 2012 Dec;171((12)):1737–46. doi: 10.1007/s00431-012-1701-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sacco MR, de Castro NP, Euclydes VL, Souza JM, Rondó PH. Birth weight, rapid weight gain in infancy and markers of overweight and obesity in childhood. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2013 Nov;67((11)):1147–53. doi: 10.1038/ejcn.2013.183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Garnett SP, Cowell CT, Baur LA, Fay RA, Lee J, Coakley J, et al. Abdominal fat and birth size in healthy prepubertal children. International journal of obesity and related metabolic disorders: journal of the International Association for the Study of Obesity. 2001;25((11)):1667–1673. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0801821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ibáñez L, Ong K, Dunger DB, de Zegher F. Early development of adiposity and insulin resistance after catch-up weight gain in small-for-gestational-age children. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2006 Jun;91((6)):2153–8. doi: 10.1210/jc.2005-2778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wijnhoven TM, van Raaij JM, Spinelli A, Rito AI, Hovengen R, Kunesova M, et al. WHO European Childhood Obesity Surveillance Initiative 2008: weight, height and body mass index in 6-9-year-old children. Pediatr Obes. 2013 Apr;8((2)):79–97. doi: 10.1111/j.2047-6310.2012.00090.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Börnhorst C, Wijnhoven TM, Kunešová M, Yngve A, Rito AI, Lissner L, et al. WHO European Childhood Obesity Surveillance Initiative: associations between sleep duration, screen time and food consumption frequencies. BMC Public Health. 2015 Apr;15((1)):442. doi: 10.1186/s12889-015-1793-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wijnhoven TM, van Raaij JM, Spinelli A, Yngve A, Lissner L, Spiroski I, et al. WHO European Childhood Obesity Surveillance Initiative: Impact of Type of Clothing Worn during Anthropometric Measurements and Timing of the Survey on Weight and Body Mass Index Outcome Measures in 6–9-Year-Old Children %J. Epidemiol Res Int. 2016;2016:16. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rito A, Wijnhoven TM, Rutter H, Carvalho MA, Paixão E, Ramos C, et al. Prevalence of obesity among Portuguese children (6–8 years old) using three definition criteria: COSI Portugal, 2008. Pediatr Obes. 2012 Dec;7((6)):413–22. doi: 10.1111/j.2047-6310.2012.00068.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Childhood Obesity Surveillance Initiative (COSI) Protocol World Health Organization Regional Office for Europe. 2016 [Google Scholar]

- 37.Childhood Obesity Surveillance Initiative (COSI) - Data collection procedures World Health Organization Regional Office for Europe. 2016 [Google Scholar]

- 38.International ethical guidelines for biomedical research involving human subjects Geneva, Council for International Organizations of Medical Sciences, World Health Organization. 2002 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.de Onis M, Onyango AW, Borghi E, Siyam A, Nishida C, Siekmann J. Development of a WHO growth reference for school-aged children and adolescents. Bull World Health Organ. 2007 Sep;85((9)):660–7. doi: 10.2471/BLT.07.043497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Physical status The use and interpretation of anthropometry. Geneva, World Health Organization. 1995 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ota E, Haruna M, Suzuki M, Anh DD, Tho H, Tam NT, et al. Maternal body mass index and gestational weight gain and their association with perinatal outcomes in Viet Nam. Bull World Health Organ. 2011 Feb;89((2)):127–36. doi: 10.2471/BLT.10.077982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cattaneo A, Burmaz T, Arendt M, Nilsson I, Mikiel-Kostyra K, Kondrate I, et al. ‘Promotion of Breastfeeding in Europe: Pilot Testing the Blueprint for Action’ Project Protection, promotion and support of breast-feeding in Europe: progress from 2002 to 2007. Public Health Nutr. 2010 Jun;13((6)):751–9. doi: 10.1017/S1368980009991844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Whitehead RG. For how long is exclusive breast-feeding adequate to satisfy the dietary energy needs of the average young baby? Pediatr Res. 1995 Feb;37((2)):239–43. doi: 10.1203/00006450-199502000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Heinig MJ, Nommsen LA, Peerson JM, Lonnerdal B, Dewey KG. Energy and protein intakes of breast-fed and formula-fed infants during the first year of life and their association with growth velocity: the DARLING Study. Am J Clin Nutr. 1993 Aug;58((2)):152–61. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/58.2.152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Owen CG, Whincup PH, Kaye SJ, Martin RM, Davey Smith G, Cook DG, et al. Does initial breastfeeding lead to lower blood cholesterol in adult life? A quantitative review of the evidence. Am J Clin Nutr. 2008 Aug;88((2)):305–14. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/88.2.305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rolland-Cachera MF, Deheeger M, Akrout M, Bellisle F. Influence of macronutrients on adiposity development: a follow up study of nutrition and growth from 10 months to 8 years of age. International journal of obesity and related metabolic disorders: journal of the International Association for the Study of Obesity. 1995;19((8)):573–578. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Stettler N, Zemel BS, Kumanyika S, Stallings VA. Infant weight gain and childhood overweight status in a multicenter, cohort study. Pediatrics. 2002 Feb;109((2)):194–9. doi: 10.1542/peds.109.2.194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lucas A, Sarson DL, Blackburn AM, Adrian TE, Aynsley-Green A, Bloom SR. Breast vs bottle: endocrine responses are different with formula feeding. Lancet. 1980 Jun;1((8181)):1267–9. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(80)91731-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.International Code of Marketing of Breast-milk Substitutes Geneva, World Health Organization. 1981 [Google Scholar]

- 50.Innocenti Declaration on the Protection Promotion and Support of Breastfeeding. UNICEF. 2014 [Google Scholar]

- 51.Paul IM, Bartok CJ, Downs DS, Stifter CA, Ventura AK, Birch LL. Opportunities for the primary prevention of obesity during infancy. Adv Pediatr. 2009;56((1)):107–33. doi: 10.1016/j.yapd.2009.08.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.The Baby Friendly Hopital Initiative UNICEF. 2014 [Google Scholar]

- 53.Maternal I, Plan YC. Report by the Secretariat. Geneva, World Health Organization. 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 54.European Food and Nutrition Action Plan 2015–2020 Copenhagen. World Health Organization- Regional Office for Europe. 2014 [Available from: http://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0008/253727/64wd14e_FoodNutAP_140426.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Protection, promotion and support of breastfeeding in Europe: a blueprint for action EU Conference on Promotion of Breastfeeding in Europe. Dublin Castle, Ireland: Promotion of Breastfeeding in Europe [Google Scholar]

- 56.Yuan ZP, Yang M, Liang L, Fu JF, Xiong F, Liu GL, et al. Possible role of birth weight on general and central obesity in Chinese children and adolescents: a cross-sectional study. Ann Epidemiol. 2015 Oct;25((10)):748–52. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2015.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zhang X, Liu E, Tian Z, Wang W, Ye T, Liu G, et al. High birth weight and overweight or obesity among Chinese children 3–6 years old. Prev Med. 2009 Aug-Sep;49((2-3)):172–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2009.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Rogers I. The influence of birthweight and intrauterine environment on adiposity and fat distribution in later life. International journal of obesity and related metabolic disorders: journal of the International Association for the Study of Obesity. 2003;27((7)):755–777. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0802316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.McDonald SD, Han Z, Mulla S, Beyene J, Knowledge Synthesis Group Overweight and obesity in mothers and risk of preterm birth and low birth weight infants: systematic review and meta-analyses. BMJ. 2010 Jul;341(jul20 1):c3428. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c3428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.McCrory C, Layte R. Breastfeeding and risk of overweight and obesity at nine-years of age. Social science & medicine (1982) 2012;75((2)):323–330. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2012.02.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary data