Abstract

Endoscopic transpapillary biliary drainage is the current standard of care for unresectable hilar malignant biliary obstruction (MBO) and bilateral metal stent placement is shown to have longer patency. However, technical and clinical failure is possible and percutaneous transhepatic biliary drainage (PTBD) is sometimes necessary. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided biliary drainage (EUS-BD) is increasingly being reported as an alternative rescue procedure to PTBD. EUS-BD has a potential advantage of not traversing the biliary stricture and internal drainage can be completed in a single session. Some approaches to bilateral biliary drainage for hilar MBO under EUS-guidance include a bridging method, hepaticoduodenostomy, and a combination of EUS-BD and transpapillary biliary drainage. The aim of this review is to summarize data on EUS-BD for hilar MBO and to clarify its advantages over the conventional approaches such as endoscopic transpapillary biliary drainage and PTBD.

Keywords: Biliary drainage, Endosonography, Hilar biliary obstruction, Neoplasms

Introduction

Patients with hilar malignant biliary obstruction (MBO) often present at an unresectable stage. Endoscopic transpapillary biliary drainage (EBD) is the current standard of care to relieve jaundice. Multiple metallic stent (MS) placement is often performed but is technically demanding and percutaneous transhepatic biliary drainage (PTBD) is sometimes needed after technical or clinical failure by endoscopic approach [1].

Endoscopic ultrasound-guided biliary drainage (EUSBD) for MBO is being increasingly reported but is mostly performed for distal MBO and only by experts [2,3]. Since it has the potential advantage of not traversing the biliary stricture, it may play a role in the management of hilar MBO as well [4]. However, data on EUS-BD for hilar MBO are still limited. In this review article, we will overview EUS-BD for hilar MBO.

Current management of unresectable hilar MBO

In unresectable hilar MBO, biliary drainage can be achieved either by EBD or PTBD. Although a systematic review [5] showed a better success rate of PTBD, EBD is the current standard of care because PTBD impairs the quality of life in general whereas EBD does not. There are some options for endoscopic management of hilar MBO: Plastic stent (PS) vs. MS [6,7] and unilateral vs. bilateral stenting [8,9].

MS is shown to have longer stent patency than PS in randomized controlled trials (RCTs) [6,7]. Some reports have demonstrated the association of liver volume with adequate biliary drainage. One study [10] showed that 33% of the liver volume should be drained in cases that have preserved liver function to obtain adequate biliary drainage, whereas 50% of the liver volume should be drained in those with impaired liver function. In another study, longer survival rates were observed in cases of hilar MBO after draining ≥50% of the liver volume [11]. To drain ≥50% the liver volume, bilateral biliary drainage is necessary in most cases. A recent Korean RCT [12] clearly demonstrated the superiority of bilateral MS placement over unilateral MS placement. Bilateral MS placement showed a longer duration of stent patency (252 days vs. 139 days, p<0.01) and statistically non-significant but clinically significant differences in survival (270 days vs. 178 days, p=0.053).

The recent development of MS suitable for hilar stenting via a thin delivery system allows easy bilateral stent placement, either by using a stent-in-stent method [13,14] or a sideby-side method [15]. These MS also allow re-interventions after recurrent biliary obstruction (RBO) following bilateral stent placement [16]; nevertheless, the procedure can be technically difficult or even impossible. When endoscopic re-intervention fails, PTBD may be necessary to relieve jaundice or cholangitis, which impairs the quality of life due to the indwelling drainage tube. Technical and clinical hurdles of transpapillary multiple MS placement for hilar MBO are caused by the complexity of the stent configuration at the hepatic hilum. To overcome the limitations of conventional approaches such as EBD and/or PTBD, another novel approach for hilar MBO has been long awaited.

Indications of EUS-BD for hilar MBO

EUS-BD is being increasingly utilized in the management of MBO in cases of failed or difficult endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP). In addition to obtaining biliary access after failed ERCP, EUS-BD does not traverse the biliary stricture, which may provide an advantage in the management of hilar MBO. There are two approaches used by EUS-BD, intrahepatic and extrahepatic, but the intrahepatic approach is mandatory for hilar MBO.

Indications and contraindications of EUS-BD for hilar MBO are shown in Table 1. Theoretically, EUS-BD can be indicated for any hilar MBO but the current indications are failed ERCP, surgically altered anatomy, and failed re-interventions for occlusion of transpapillary placed stents. Contraindications are severe coagulopathy, massive ascites, intervening vessels, and unstable conditions unfit for endoscopic procedures. In such cases, EUS-BD might have higher risks of morbidity or mortality due to complications such as bleeding, bile leak, and stent migration. Furthermore, despite reports of a high technical success rate and acceptable adverse event rate, expertise is necessary for EUS-BD as dedicated devices for EUS-BD are currently limited.

Table 1.

Current Indications and Contraindications of Endoscopic Ultrasound-Guided Biliary Drainage for Hilar Malignant Biliary Obstruction

| Indications |

| Failed ERCP |

| Surgically altered anatomy i.e., Roux-en-Y reconstruction |

| Failed re-intervention for transpapillary stent occlusion |

| Contraindications |

| Severe coagulopathy |

| Massive ascites |

| Intervening vessels including collateral vessels |

| Unstable conditions unfit for endoscopic procedures |

ERCP, endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography.

TECHNIQUES OF EUS-BD FOR HILAR MBO

EUS-guided hepaticogastrostomy (EUS-HGS) is one of the most common EUS-BD procedures via an intrahepatic approach [17]. In EUS-HGS, biliary access to segment 2 or 3 is established via the cardia or lesser curvature of the stomach under EUS guidance, and a stent is placed from B2 or B3 to the stomach. In hilar MBO, therefore, biliary drainage of the left biliary system alone is achieved by EUS-HGS, leaving the right biliary system undrained with potential risks of inadequate biliary drainage or segmental cholangitis.

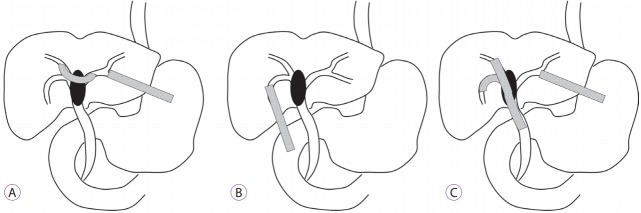

As shown in transpapillary stenting, bilateral drainage can potentially lead to better clinical outcomes for hilar MBO. The approaches to obtain bilateral drainage with EUS-BD include a bridging method, EUS-guided hepaticoduodenostomy (EUS-HDS), and a combined EUS and ERCP approach (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Techniques of bilateral endoscopic ultrasound-guided biliary drainage. (A) Bridging method. (B) Endoscopic ultrasound-guided hepaticoduodenostomy. (C) Combined endoscopic ultrasound-guided hepaticogastrostomy and transpapillary stenting.

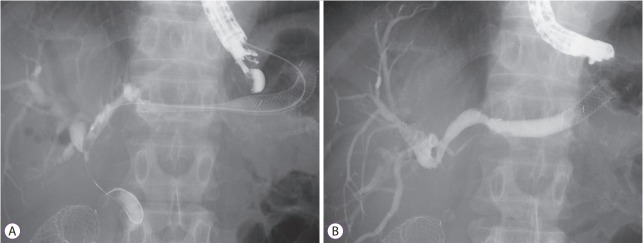

The bridging method [18] employs a left intrahepatic bile duct (IHBD) access similar to conventional EUS-HGS. After obtaining biliary access from the stomach to the left IHBD using a 19-gauge fine needle aspiration needle and a guidewire, the needle is replaced by a standard catheter and a guidewire is advanced through the hilar stricture into the right IHBD. In difficult cases, a steerable catheter and a hydrophilic guidewire are helpful to pass the hilar stricture. An uncovered bridging MS with a thin delivery system is placed across the hilar stricture, followed by a covered MS placement from the left IHBD to the stomach, as seen with conventional EUS-HGS. During this bridging method, guidewire passage or stent deployment to the right biliary system through the hilar stricture can be technically challenging depending on the angle of left and right hepatic duct confluence. In technically difficult cases, a prolonged procedure time can increase the risk of bile leak and sequential bridging stent placement can be an option. A conventional HGS stent is placed in the left IHBD in the first session and after fistula maturation of the HGS, a bridging stent placement can be attempted by cannulating through the HGS stent (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Bridging method. (A) Endoscopic ultrasound-guided hepaticogastrostomy was performed during the first session. (B) A bridging stent was placed during the second session.

EUS-HDS [18,19] employs a right IHBD access from the duodenum, which is a complement of EUS-HGS to the left IHBD. However, EUS-HDS procedures are performed only in a few expert centers and therefore, reports are limited. Ogura et al. [18] reported a locking method with a combination of uncovered and covered MSs to prevent stent migration but the use of a PS dedicated to EUS-BD [20] was also reported. Given the limited number of reports, the best technique of EUS-HDS has not been established thus far.

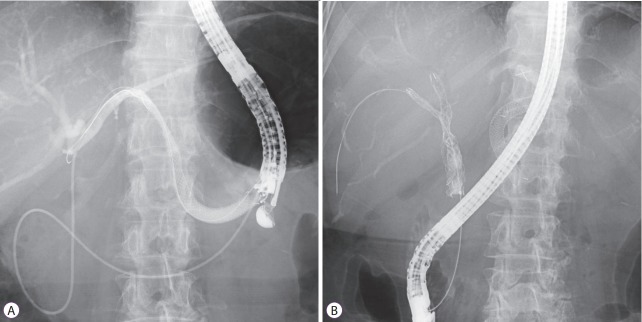

In high-grade hilar MBO, a combined EUS and ERCP approach proposed by Park [21] can be a treatment option. In this approach, EUS-HGS to the left IHBD and transpapillary stenting to the right IHBD are performed (Fig. 3). This approach is feasible due to two anatomical reasons. First, as observed with resectable hilar MBO, the left hepatic duct is longer than the right hepatic duct, allowing drainage of the whole left biliary system by a single EUS-HGS stent. Second, the right IHBD is more prone to cancer invasion especially in cases with gallbladder cancer, necessitating multiple stenting of the right biliary system. Although multiple stenting in EUS-BD is theoretically possible, transpapillary multiple stent placement is more established. Therefore, a combination of simple EUS-HGS in the left IHBD and multiple stenting in the right IHBD can achieve >50% biliary drainage with technical feasibility.

Fig. 3.

Combined endoscopic ultrasound-guided hepaticogastrostomy and transpapillary stenting. (A) Endoscopic ultrasound-guided hepaticogastrostomy was performed during the first session. (B) Transpapillary multiple stent-in-stent placement was performed during the second session.

Clinical outcomes of EUS-BD for hilar MBO

Table 2 summarized data on EUS-BD for hilar MBO [18-20,22-29]. The overall technical success rate was 98% and the overall adverse event rate was 8%. However, the overall clinical success rate was 77%, which was lower than previously reported in a systematic review of EUS-BD [30]. Clinical outcomes were comparable between the initial EUS-BD procedure and the rescue EUS-BD procedure after failed transpapillary drainage. However, the number of cases was too small and the procedures were performed only by experts. Therefore, publication bias was possible especially with respect to adverse events. A relatively low clinical success rate suggests that appropriate biliary drainage for unresectable hilar MBO is difficult in any approach: ERCP, EUS, or PTBD. The available literature was focused on short-term outcomes and long-term outcomes such as RBO and its re-interventions were not investigated. Future studies should be focused on patient selection or on treatment selection for better management of hilar MBO.

Table 2.

Data on Endoscopic Ultrasound-Guided Biliary Drainage for Hilar Malignant Biliary Obstruction

| Study | n | Initial/rescue | Stent | Drainage method | Technical success | Clinical success | Adverse events |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bories et al. (2007) [22] | 4 | Initial | PS | HGS | 4 | 4 | 1 stent clogging |

| Ogura et al. (2014) [23] | 1 | Initial | UMS+CMS | Bridging | 1 | N/A | N/A |

| Ogura et al. (2015) [18] | 11 | Initial/Rescue | UMS+CMS | 4 HDS, 7 Bridging | 11 | N/A | 0 |

| Prachayakul et al. (2015) [24] | 1 | Initial | UMS+CMS | Bridging | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Moryoussef et al. (2017) [25] | 18 | Initial | UMS+CMS | 14 HGS, 3 Bridging | 17 | 13 | 3 |

| Park et al. (2010) [26] | 3 | Rescue | CMS | HGS | 3 | 3 | 0 |

| Park et al. (2013) [19] | 2 | Rescue | CMS | HDS | 2 | 2 | 0 |

| Minaga et al. (2017) [27] | 30 | Rescue | CMS or PS | 28 HGS, 2 HDS | 29 | 22 | 3 bile peritonitis |

| Ogura et al. (2017) [28] | 10 | Rescue | CMS | 8 HGS, 2 HDS | 10 | 9 | 0 |

| Kanno et al. (2017) [29] | 7 | Rescue | CMS | HGS | 7 | 4 | 0 |

| Mukai et al. (2017) [20] | 1 | Rescue | PS | HDS | 1 | N/A | 0 |

| Overall | 88 | 98% (86/88) | 77% (58/75) | 8% (7/87) |

CMS, covered metal stent; HDS, hepaticoduodenostomy; HGS, hepaticogastrostomy; N/A, not available; PS, plastic stent; UMS, uncovered metal stent.

EUS-BD in comparison with transpapillary biliary stenting and PTBD

Transpapillary stenting is still the standard of care for unresectable hilar MBO, and PTBD is often a rescue procedure for failed endoscopic management. As described above, EUS-BD has a definite role in the management of hilar MBO. The advantages and disadvantages are summarized in Table 3. Overall, EUS-BD has a common advantage of both transpapillary stenting and PTBD, namely, a single session internal drainage without crossing the biliary stricture. Internal drainage maintains the quality of life and drainage without crossing the stricture potentially allows longer stent patency.

Table 3.

Advantages and Disadvantages of EUS-BD

| EUS-BD | EBD | PTBD | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Advantage | A single step internal drainage | Long term data available | High technical success rate |

| Simplicity at the hilum: possible longer patency | Possible tube rinse for clogging | ||

| Disadvantage | No long term data | Technical difficulty for multiple stenting | Impaired QOL |

| Special technique necessary for right IHBD approach | Complexity at the hilum | High AE rate and re-intervention rate | |

| Contraindications: ascites, coagulopathy | Chance of Post-ERCP pancreatitis | Contraindications: ascites, coagulopathy | |

| Chance of bile leak, stent migration |

AE, adverse event; EBD, endoscopic transpapillary biliary drainage; ERCP, endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography; EUS-BD, endoscopic ultrasound-guided biliary drainage; IHBD, intrahepatic bile duct; PTBD, percutaneous transhepatic biliary drainage; QOL, quality of life.

Limitations of EUS-BD

First of all, the number of reported cases is small. Although the rate of technical success is high, most studies were reported by experts and publication bias may exist. Theoretically, EUS-BD provides better stent patency but long-term outcomes are unclear. Given the improved survival in cases of biliary malignancy, many patients with unresectable hilar MBO need re-intervention for RBO. Endoscopic re-interventions through the EUS-BD route are often possible but PTBD is sometimes necessary to control cholangitis after complex biliary drainage procedures. In addition, the rate of adverse events was only 8% in our review but the intrahepatic approach reportedly had a higher adverse event rate compared to the extrahepatic approach [31]. Finally, technical expertise for performing EUS-BD is not always available in most centers. In such situations, if urgent drainage for cholangitis is necessary, a PTBD can be temporarily placed and conversion from PTBD to EUS-BD can be performed at a later stage [32]. Overall, the evidence regarding these issues is limited and further investigation is warranted.

Conclusions

In conclusion, EUS-BD can be a promising treatment option for unresectable hilar MBO, both as the initial and the rescue procedure. Standardization of procedures as well as development of dedicated devices are necessary to establish the role of EUS-BD in the management of hilar MBO. Future RCTs comparing EUS-BD with EBD or PTBD are warranted to confirm the role of EUS-BD for managing hilar MBO.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest:The authors have no financial conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Moon JH, Rerknimitr R, Kogure H, Nakai Y, Isayama H. Topic controversies in the endoscopic management of malignant hilar strictures using metal stent: side-by-side versus stent-in-stent techniques. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2015;22:650–656. doi: 10.1002/jhbp.270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nakai Y, Isayama H, Yamamoto N, et al. Indications for endoscopic ultrasonography (EUS)-guided biliary intervention: does EUS always come after failed endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography? Dig Endosc. 2017;29:218–225. doi: 10.1111/den.12752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Minaga K, Kitano M. Recent advances in endoscopic ultrasound-guided biliary drainage. Dig Endosc. 2018;30:38–47. doi: 10.1111/den.12910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nakai Y, Isayama H, Matsubara S, Koike K. Conversion of transpapillary drainage to endoscopic ultrasound-guided hepaticogastrostomy and gallbladder drainage in a case of malignant biliary obstruction with recurrent cholangitis and cholecystitis (with videos) Endosc Ultrasound. 2017;6:205–207. doi: 10.4103/2303-9027.208172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Moole H, Dharmapuri S, Duvvuri A, et al. Endoscopic versus percutaneous biliary drainage in palliation of advanced malignant hilar obstruction: a meta-analysis and systematic review. Can J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;2016:4726078. doi: 10.1155/2016/4726078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sangchan A, Kongkasame W, Pugkhem A, Jenwitheesuk K, Mairiang P. Efficacy of metal and plastic stents in unresectable complex hilar cholangiocarcinoma: a randomized controlled trial. Gastrointest Endosc. 2012;76:93–99. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2012.02.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mukai T, Yasuda I, Nakashima M, et al. Metallic stents are more efficacious than plastic stents in unresectable malignant hilar biliary strictures: a randomized controlled trial. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2013;20:214–222. doi: 10.1007/s00534-012-0508-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.De Palma GD, Galloro G, Siciliano S, Iovino P, Catanzano C. Unilateral versus bilateral endoscopic hepatic duct drainage in patients with malignant hilar biliary obstruction: results of a prospective, randomized, and controlled study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2001;53:547–553. doi: 10.1067/mge.2001.113381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yasuda I, Mukai T, Moriwaki H. Unilateral versus bilateral endoscopic biliary stenting for malignant hilar biliary strictures. Dig Endosc. 2013;25 Suppl 2:81–85. doi: 10.1111/den.12060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Takahashi E, Fukasawa M, Sato T, et al. Biliary drainage strategy of unresectable malignant hilar strictures by computed tomography volumetry. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21:4946–4953. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i16.4946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vienne A, Hobeika E, Gouya H, et al. Prediction of drainage effectiveness during endoscopic stenting of malignant hilar strictures: the role of liver volume assessment. Gastrointest Endosc. 2010;72:728–735. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2010.06.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee TH, Kim TH, Moon JH, et al. Bilateral versus unilateral placement of metal stents for inoperable high-grade malignant hilar biliary strictures: a multicenter, prospective, randomized study (with video) Gastrointest Endosc. 2017;86:817–827. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2017.04.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lee TH, Moon JH, Kim JH, et al. Primary and revision efficacy of crosswired metallic stents for endoscopic bilateral stent-in-stent placement in malignant hilar biliary strictures. Endoscopy. 2013;45:106–113. doi: 10.1055/s-0032-1325928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kogure H, Isayama H, Nakai Y, et al. High single-session success rate of endoscopic bilateral stent-in-stent placement with modified large cell Niti-S stents for malignant hilar biliary obstruction. Dig Endosc. 2014;26:93–99. doi: 10.1111/den.12055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lee TH, Park DH, Lee SS, et al. Technical feasibility and revision efficacy of the sequential deployment of endoscopic bilateral side-by-side metal stents for malignant hilar biliary strictures: a multicenter prospective study. Dig Dis Sci. 2013;58:547–555. doi: 10.1007/s10620-012-2346-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lee TH, Moon JH, Choi HJ, et al. Third metal stent for revision of malignant hilar biliary strictures. Endoscopy. 2016;48:1129–1133. doi: 10.1055/s-0042-112574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nakai Y, Isayama H, Yamamoto N, et al. Safety and effectiveness of a long, partially covered metal stent for endoscopic ultrasound-guided hepaticogastrostomy in patients with malignant biliary obstruction. Endoscopy. 2016;48:1125–1128. doi: 10.1055/s-0042-116595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ogura T, Sano T, Onda S, et al. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided biliary drainage for right hepatic bile duct obstruction: novel technical tips. Endoscopy. 2015;47:72–75. doi: 10.1055/s-0034-1378111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Park SJ, Choi JH, Park DH, et al. Expanding indication: EUS-guided hepaticoduodenostomy for isolated right intrahepatic duct obstruction (with video) Gastrointest Endosc. 2013;78:374–380. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2013.04.183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mukai S, Itoi T, Tsuchiya T, Tanaka R, Tonozuka R. EUS-guided right hepatic bile duct drainage in complicated hilar stricture. Gastrointest Endosc. 2017;85:256–257. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2016.07.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Park DH. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided biliary drainage of hilar biliary obstruction. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2015;22:664–668. doi: 10.1002/jhbp.271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bories E, Pesenti C, Caillol F, Lopes C, Giovannini M. Transgastric endoscopic ultrasonography-guided biliary drainage: results of a pilot study. Endoscopy. 2007;39:287–291. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-966212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ogura T, Masuda D, Imoto A, Umegaki E, Higuchi K. EUS-guided hepaticogastrostomy for hepatic hilar obstruction. Endoscopy. 2014;46 Suppl 1 UCTN:E32–E33. doi: 10.1055/s-0033-1359133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Prachayakul V, Aswakul P. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided biliary drainage: bilateral systems drainage via left duct approach. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21:10045–10048. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i34.10045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Moryoussef F, Sportes A, Leblanc S, Bachet JB, Chaussade S, Prat F. Is EUS-guided drainage a suitable alternative technique in case of proximal biliary obstruction? Therap Adv Gastroenterol. 2017;10:537–544. doi: 10.1177/1756283X17702614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Park DH, Song TJ, Eum J, et al. EUS-guided hepaticogastrostomy with a fully covered metal stent as the biliary diversion technique for an occluded biliary metal stent after a failed ERCP (with videos) Gastrointest Endosc. 2010;71:413–419. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2009.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Minaga K, Takenaka M, Kitano M, et al. Rescue EUS-guided intrahepatic biliary drainage for malignant hilar biliary stricture after failed transpapillary re-intervention. Surg Endosc. 2017;31:4764–4772. doi: 10.1007/s00464-017-5553-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ogura T, Onda S, Takagi W, et al. Clinical utility of endoscopic ultrasound-guided biliary drainage as a rescue of re-intervention procedure for high-grade hilar stricture. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;32:163–168. doi: 10.1111/jgh.13437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kanno Y, Ito K, Koshita S, et al. EUS-guided biliary drainage for malignant perihilar biliary strictures after further transpapillary intervention has been judged to be impossible or ineffective. Intern Med. 2017;56:3145–3151. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.9001-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang K, Zhu J, Xing L, Wang Y, Jin Z, Li Z. Assessment of efficacy and safety of EUS-guided biliary drainage: a systematic review. Gastrointest Endosc. 2016;83:1218–1227. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2015.10.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dhir V, Artifon EL, Gupta K, et al. Multicenter study on endoscopic ultrasound-guided expandable biliary metal stent placement: choice of access route, direction of stent insertion, and drainage route. Dig Endosc. 2014;26:430–435. doi: 10.1111/den.12153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Paik WH, Lee NK, Nakai Y, et al. Conversion of external percutaneous transhepatic biliary drainage to endoscopic ultrasound-guided hepaticogastrostomy after failed standard internal stenting for malignant biliary obstruction. Endoscopy. 2017;49:544–548. doi: 10.1055/s-0043-102388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]