Abstract

BACKGROUND

Young adults with familial hypercholesterolemia (FH) are at a critical period for establishing behaviors to promote future cardiovascular health.

OBJECTIVE

To examine challenges transitioning to adult care for young adults with FH and parents of FH-affected young adults in the context of 2 developmental tasks, transitioning from childhood to early adulthood and assuming responsibility for self-management of a chronic disorder.

METHODS

Semistructured, qualitative interviews were conducted with 12 young adults with FH and 12 parents of affected young adults from a pediatric subspecialty preventive cardiology program in a north-eastern academic medical center. Analyses were conducted using a modified grounded theory framework.

RESULTS

Respondents identified 5 challenges: (1) recognizing oneself as a decision maker, (2) navigating emerging independence, (3) prioritizing treatment for a chronic disorder with limited signs and symptoms, (4) managing social implications of FH, and (5) finding credible resources for guidance. Both young adults and parents proposed similar recommendations for addressing these challenges, including the need for family and peer involvement to establish and maintain diet and exercise routines and to provide medication reminders. Systems-level recommendations included early engagement of adolescents in shared decision-making with health care team; providing credible, educational resources regarding FH; and using blood tests to track treatment efficacy.

CONCLUSION

Young adults with FH transitioning to adult care may benefit from explicit interventions to address challenges to establishing healthy lifestyle behaviors and medication adherence as they move toward being responsible for their medical care. Further research should explore the efficacy of recommended interventions.

Keywords: Familial, hypercholesterolemia, Transition to adult care, Young adult, Chronic disorder, Cardiovascular health

Introduction

Adolescents and young adults (hereafter, “young adults”), between the ages of 17 to 21 years, are at a critical period for establishing patterns of behavior to promote cardiovascular health.1–4 The number of healthy lifestyle choices made by young adults—including exercising, adhering to healthy dietary patterns, being at a healthy weight, and not smoking—is strongly associated with maintaining a low risk for heart disease well into middle age.2,5–7 It is at just this time that young adults transition to adult medical care and must learn to independently navigate the health care system while simultaneously managing the routine developmental milestones of early adulthood.8–11 Moreover, health care professionals face uncertainty regarding how to best facilitate this transition in the general pediatric population.12–14

Chronic disorders such as type 1 diabetes or congenital heart disease further complicate the transition to adulthood.15–18 For young adults with chronic disorders, research has documented prolonged gaps between leaving pediatric subspecialty care and entering care with an adult provider.19,20 Factors impeding timely health care transitioning at the patient level include lack of knowledge about one’s disorder, competing life priorities such as work or school, and the desire for continued parental involvement.21 Systems-level barriers to continuous access to care include a lack of specific adult provider referrals and insufficient information transfer between pediatric and adult providers.19,22 Surveys of subspecialty providers have also documented a lack of training regarding managing transitions.23,24

Young adults with lipid disorders provide a salient example of how a chronic disease adds to the challenges of the health care transition. Heterozygous familial hypercholesterolemia (FH) is a genetic lipid disorder characterized by abnormally high lipid levels and an increased risk of premature cardiovascular disease (CVD) events later in life,25,26 with 25% of affected, untreated women and 50% of men having a CVD event by age 50.25,26 Early intervention to lower cholesterol levels—including establishing healthy diet and exercise patterns and taking medication—may decrease this risk.1–4,27 When transitioning to adulthood, young adults with FH must continue these healthy patterns of behavior as they assume responsibility for management of their disorder.16–18

Despite the serious consequences of untreated or poorly managed FH and the importance of early adulthood as a critical period for establishing preventive cardiovascular behaviors, there is a lack of age-specific resources for young adults with FH during the health care transition.8,28 In fact, most of the literature on transition age youth in the general population focuses primarily on the logistics of the transfer to adult medical care, such as selecting a new physician and navigating the health care system. However, transfer to an adult model of care is but one of many issues in the large transition to early adulthood for youth with FH, including the realities of understanding and implementing healthy patterns of behavior within the context of an FH-specific treatment plan.8,28

Further confounding this lack of resources are conflicting recommendations in pediatric and adult guidelines for treating high cholesterol in this age population.29 A recent analysis29 of the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, conducted by Gooding et al, reported that almost 500,000 young people aged 17 to 21 years in the United States have an low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) level that would qualify for pharmacologic treatment under pediatric guidelines (ie, 2011 National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Integrated Guidelines for Cardiovascular Health and Risk Reduction in Children and Adolescents30) but not under a set of adult guidelines (ie, 2013 American College of Cardiology and American Heart Association Guideline on the Treatment of Blood Cholesterol to Reduce Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Risk in Adults31). Although most young adults with FH have an LDL-C ≥190 mg/dL and would thus qualify for lipid-lowering therapy under either guidelines, some patients with heterozygous FH have LDL-C levels in the more moderately elevated range (∼ 160–190 mg/ dL) accompanied by a family history of early CVD and would meet criteria for statins under the pediatric but not the adult guidelines. Whether practicing adult providers recommend continuing lipid-lowering therapy or stopping it for these young people is unknown. The discrepancy in guidelines could create uncertainty and confusion for patients with more moderate lipid elevations as they move from pediatric to adult subspecialty care.29

This research was designed to illuminate the perspectives of young adults with FH and parents of affected young adults during the transition to adult care. A series of semistructured, qualitative interviews was conducted to gain insight into the experiences, transitioning needs, and recommendations of these individuals.

Materials and methods

Overview

Data were obtained as part of a Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute-funded study conducted by a joint research team from Tufts Medical Center and Boston Children’s Hospital (BCH). The qualitative arm of this study sought to characterize patient preferences regarding cholesterol screening and treatment for young adults and parents of young adults who fell into 1 of 3 distinct groups with varying degrees of indicated risk for high cholesterol: living with FH, obese, and no clinically indicated risk. See Mackie et al32 for additional details. The research reported in this article, which was approved and monitored by an Institutional Review Board at BCH, specifically focused on the perspectives of young adults with FH and parents of affected young adults regarding their needs around the transition to adult care.

Sample

Using purposive sampling, 24 participants (12 affected young adults and 12 parents of affected young adults) were recruited from the BCH preventive cardiology program. This multisite program primarily serves privately insured patients, with 12.8% of families receiving public insurance (Medicaid and/or Medicare) and 8.3% of the patient population self-identified as African-American. We sampled until we achieved thematic saturation for each of the 2 samples (young adults and parents); this sampling frame is consistent with prior research suggesting the potential for data saturation within 12 interviews.33

To be considered eligible for participation, individuals had to meet the following criteria: (1) young adult aged 17 to 21 years meeting the Simon Broome criteria for FH or parent of young adult who met the Simon Broome criteria34; (2) a working knowledge of spoken and written English; and (3) without cognitive or communication disorders that would limit participation in interviews. Young adults and parents did not have to participate as parent-child dyads, although most participants (54%) did have a relative who also participated.

The practice electronic medical records were used to identify eligible persons who were sent letters describing the study and soliciting participation. Included was a return-addressed, stamped reply postcard with “Do Not Contact” that could be mailed back if desired. To best facilitate study enrollment, recruitment efforts prioritized contacting those individuals who already had an upcoming clinical visit scheduled. Because our Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute-funded study’s overall aim was to examine medical decision-making, we did not seek to deliberately recruit young adults or parents who were not engaged in the health care system. The sample was recruited and interviewed over a span of 13 months.

Procedure

Semistructured interviews, including a brief demographic survey, were conducted at BCH-affiliated offices. Interviews lasted approximately 1 hour. All interviews were audiotaped and later transcribed verbatim. Members of the research team were trained in data collection and management by a skilled qualitative researcher (Dr Mackie), with fidelity monitoring conducted throughout the study period. Participants received monetary compensation for their travel and time, including a $25 gift card and either a parking voucher or a $9 public transportation card as a reimbursement for transportation.

Measures

The quantitative survey included 3 relevant domains: (1) demographic characteristics of the participant, (2) health of the young adult (self or parent report), and (3) health care of the young adult (self-report or parent report). The qualitative interview asked participants structured questions that broadly addressed decision-making regarding cholesterol screening and treatment. Areas of interest to this research included: (1) perceptions of high cholesterol, (2) perceptions of treatment options for high cholesterol, (3) preferred treatment modality, and (4) information needs and recommendations. Copies of the quantitative survey and interview guide for young adults are included as Supplementary Appendices; parent measures paralleled those of the young adult and are available upon request.

Analysis

Survey data were analyzed using descriptive statistics in Stata (Stata Statistical Software: Release 12; StataCorp LP, College Station, TX). Double entry of data, in combination with subsequent data comparison and creation of a final data set, was used to ensure that the research team captured respondents’ answers as accurately as possible.

The semistructured interview transcripts were analyzed using a modified grounded theory framework referred to as “Coding Consensus, Co-occurrence, and Comparison,” a particular analytic process in which individual members of the research team each read through interview transcripts and create a codebook, then meet to compare their findings, resolve disagreements, and develop one codebook with rigorous, agreed-upon definitions.35 An interdisciplinary team of investigators individually coded 6 interviews based on an initial coding schema. After comparing coded interviews, the team revised definitions for the final codebook. Two members of the team (Drs Sliwinski and Shah), under the supervision of a trained qualitative researcher (Dr Mackie), coded all 24 interviews focusing on codes related to the transition to adult care. Whenever discrepancies arose, members of the research team met to discuss the issue, reached a resolution, and modified the codebook accordingly. The codebook included a priori challenges and recommendations predicted from the literature but also deliberately sought to identify emergent themes about the transition to adult care arising from the interviews. In the results, we present each of the major challenges that emerged in this analysis, detailing the number of young adults and parents who endorsed each challenge and providing illustrative quotations from a young adult and parent, followed by respondent recommendations.

Results

Characteristics of the sample, family history, and decision-making

Demographic characteristics of the sample are provided in Table 1. The mean age of respondents was 18.4 years (±1.2) for young adults and 49.3 years (±7.4) for parents, and most participants in both groups were non-Hispanic whites. On an ordinal scale, all young adults reported their health as at least good; parents responded similarly. About 75% of young adults and 83.3% of parents reported regular use of prescription medicine by the index young adult for high cholesterol. Most respondents disclosed a family history of early cardiovascular events, with two-thirds of young adults and three-quarters of parents reporting that the young adult had a first- or second-degree relative who experienced a stroke and/or heart attack. All respondents endorsed some level of parental involvement in the young adult’s medical decision-making, with the majority describing parents as very involved.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the sample, family history, and decision-making

| Young adults | Parents | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Domain | Variable | n (%) or mean (SD) | n (%) or mean (SD) |

| Demographic characteristics of respondents | Age | 18.4 (1.2) | 49.3 (7.4) |

| Gender | |||

| Female | 6 (50) | 10 (83.3) | |

| Race | |||

| Asian | 1 (8.3) | 0 (0) | |

| Black or African-American | 1 (8.3) | 1 (8.3) | |

| White | 9 (75) | 9 (75) | |

| Missing | 1 (8.3) | 2 (16.7) | |

| Ethnicity | |||

| Hispanic or Latino | 2 (16.7) | 1 (8.3) | |

| Not Hispanic/Latino | 10 (83.3) | 10 (83.3) | |

| Missing | 0 (0) | 1 (8.3) | |

| Health of young adult | Perception of young adult’s health | ||

| Excellent | 1 (8.3) | 3 (25) | |

| Very good | 6 (50) | 5 (41.7) | |

| Good | 5 (41.7) | 3 (25) | |

| Missing | 0 (0) | 1 (8.3) | |

| Regular use of prescription medicine by young adult (cholesterol) | |||

| Yes | 9 (75) | 10 (83.3) | |

| Family history of cardiovascular event (stroke and/or heart attack) | |||

| First-degree relative | 3 (25) | 1 (8.3) | |

| Second-degree relative | 5 (41.7) | 8 (66.6) | |

| No | 1 (8.3) | 2 (16.7) | |

| Do not know | 2 (16.7) | 0 (0) | |

| Missing | 1 (8.3) | 1 (8.3) | |

| Health care of young adult | Young adult’s insurance | ||

| Private | 7 (58.3) | 9 (75) | |

| Public | 1 (8.3) | 2 (16.7) | |

| Do not know | 4 (33.3) | 0 (0) | |

| Missing | 0 (0) | 1 (8.3) | |

| Parental involvement in young adult’s health care | |||

| Very involved | 11 (91.7) | 9 (75) | |

| Somewhat involved | 1 (8.3) | 3 (25) | |

| Rarely/never involved | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

Thematic findings on transition to adult care

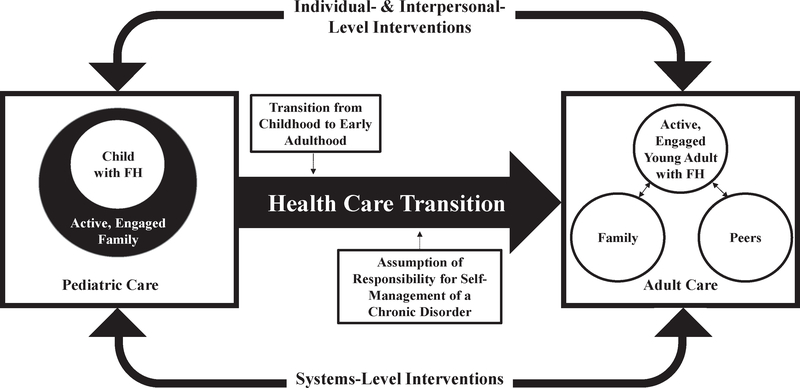

Based on a review of the literature and information gained through qualitative interviews, Figure 1 was developed to serve as conceptual framework and a visual representation of how two tasks, the transition from childhood to early adulthood and the assumption of responsibility for self-management of a chronic disorder like FH, impact the transition to adult care. In childhood, the family makes medical decisions for the child; in early adulthood, the individual moves toward autonomously engaging in shared decision-making with his or her physician with potential input from social networks including family and peers. Young adults and parents identified 5 challenges for young adults with FH transitioning to adult care that aligned with these 2 tasks. Two challenges were associated with the first task: (1) recognizing oneself as a decision maker and (2) navigating emerging independence. The remaining 3 challenges were associated with the second task: (3) prioritizing treatment for a chronic disorder with limited signs and symptoms, (4) managing social implications of FH, and (5) finding credible resources for guidance (see Table 2). Respondents also made recommendations for how one could improve this transitioning process in 2 domains: individual- and interpersonal-level interventions and systems-level interventions. These recommended interventions are represented in Figure 1 by the thin, solid arrows between pediatric and adult care.

Figure 1.

Proposed conceptual framework of study drawing on literature review and qualitative interviews.

Table 2.

Challenges faced by young adults with FH transitioning from pediatric to adult health care

| Challenges and endorsement | Description | Illustrative quotations |

|---|---|---|

| Challenges associated with the transition from childhood to early adulthood | ||

| Recognizing oneself as a decision maker;12 young adults, 10 parents | The commonly young age of diagnosis and strong genetic component of FH can create a dynamic in which parents have made all FH-related medical decisions for children as they age. Young adults described having to reeducate themselves on the specifics of FH and the treatment options available to them. | As an 18 year old, they [my parents] would voice their opinion, but still let me make my own decision and talk it out with me. -Young Adult When they’re children, before [age] 12, you have to help. You have to decide for them… when they’re older like that, it’s that whole buying in process-getting them to understand what’s available [in terms of treatment] and what it’s going to do to them. -Parent |

| Navigating emerging independence;11 young adults, 6 parents | General logistical and developmental issues associated with early adulthood, such as learning to live independently from one’s parents, assuming greater financial responsibility, and adjusting to the rigors of a new academic or professional schedule, complicate the health care transition. | I know sometimes it’s easier just to go. grab a burger than it is to go out and buy food, also it’s cheaper too. So it’s a lot easier for me to use my swipe in the dining hall and get food in there than it is to go down to Whole Foods or something like that. -Young Adult …Especially when she’s in school, just the pressure… and time that go into studies and that kind of stuff. And I think, I don’t know, it’s just a little bit of laziness or not effective use of time, because it’s not as structured. You know? The lack of structure makes it a little harder to… sometimes when they have free time they don’t know what to do… They’re not quite as able/ willing to make their own structure. -Parent |

| Challenges associated with the assumption of responsibility for self-management of a chronic disorder | ||

| Prioritizing treatment for a chronic disorder with limited signs and symptoms;5 young adults, 10 parents | Young adults have difficulty prioritizing treatment that is meant to keep them healthy later in life. | High cholesterol isn’t really something that I can feel. I don’t feel sick if I’m not taking my meds, so it’s like I don’t feel the difference. I see a number on a piece of paper, but it’s like, ‘‘Do I even really need it? Am I really even going to get a heart attack;is it really that likely?’’ It’s like I could just totally go off it and save twenty bucks a bottle. -Young Adult Young adults’ tendency is] to shelve it [treatment], because, “I’ve got more important things to do. I’ve got to graduate from college. I’m going to have a career. Buy my first car. I’m going to get married, you know, so I’ll solve this cholesterol problem later.” -Parent |

| Managing Social Implications of FH;10 Young Adults, 6 Parents | Young adults articulated how concern about peers’ opinions restricted social activities centered around eating, and endorsed feelings of shame stemming from the belief that having a genetic disorder or being on medication makes one “unhealthy.” | It would be kind of embarrassing to tell people what you have. They would probably change their way of looking at you. Maybe they’ll change their friendship or relationship status with you. You never know. -Young Adult Being with a group of his peers he’s more likely to not be a trendsetter and say, ‘‘Oh, let’s go and get some vegetables and fruits.’’ It will be, “Oh, let’s go to the McDonald’s, or let’s go to KFC, or let’s go to Taco Bell.’’ That seems to be am easier sell in social settings. -Parent |

| Finding credible resources for guidance;12 young adults, 10 parents | There is a need for additional credible resources to be made available to young adults seeking with FH. | I think [newly diagnosed young adults] need to hear personal stories. So people of their ages, people like me who live with it and like this is my life, and just hear from us and how it’s not anything to worry about… I know that if I were in those shoes I would want to hear from someone my age… I think it would be good to hear stories from people like me. -Young Adult He [son] just had to do an online alcohol education program for college and pass the test. And I thought, Well, why aren’t they doing this with nutrition? You know, why aren’t they using something like this to inform kids about the condition [familial hypercholesterolemia], the diet, you know, what happens, what’s a good HDL number, what’s a bad LDL number… -Parent |

FH, familial hypercholesterolemia;LDL, low-density lipoprotein;HDL, high-density lipoprotein.

Challenges associated with the transition from childhood to early adulthood

In the following section, we describe the 2 challenges identified by respondents that are associated with the transition from childhood to early adulthood. See Table 2 for descriptions of challenges and illustrative quotations.

Recognizing oneself as a decision maker

All young adults and 10 parents endorsed the young adult’s role as a novice decision maker as a transitioning challenge. Given the genetic basis of FH, parents were typically knowledgeable about the disorder, either through a family member’s experience or their own. This prior knowledge, in combination with the commonly young age of diagnosis of the study’s young adult participants, often created a dynamic in which parents had made FH-related medical decisions for children as they aged.

Many young adults expressed difficulty with adopting responsibility for their treatment due to a perceived lack of understanding of their disorder and the rationale for treatment decisions their parents had previously made with health care providers. This was despite attending multiple medical and nutrition counseling visits in a pediatric preventive cardiology program. Respondents described needing to completely reeducate themselves on the specifics of FH and the treatment options available to them to form their own opinions on what was best for their health.

Although all young adults felt compelled to take control of their care, most still valued guidance from their parents and peers, as represented in Figure 1 by the small, double-ended arrows between the active, engaged patient and his or her family and peers under adult care.

Navigating emerging independence

Eleven young adults and 6 parents described logistical and developmental challenges typical of emerging adults including living independently from parents, assuming greater financial responsibility, and adjusting to the rigors of a new academic or professional schedule.36 In addition, young adults and parents identified challenges specific to FH care. Young adults struggled to make and keep appointments with lipid specialists, locate a pharmacy to regularly pick up medications, and adhere to medication regimens without parental guidance or reminders. Young adults also articulated challenges maintaining diet and exercise regimens while adjusting to a new routine and environment at college or in the workforce. Many respondents expressed how increased academic pressure and busy schedules contributed to multifaceted unhealthy behaviors. Time constraints and financial restrictions also were endorsed as challenges with respect to maintaining a healthy lifestyle and paying for medication. Parents’ perspectives mirrored these comments and attributed decreases in their children’s activity levels to increased academic or work demands and the loss of structured exercise like organized sports.

Challenges associated with the assumption of responsibility for self-management of a chronic disorder

In the following section, we describe the 3 challenges identified by respondents that are associated with the assumption of responsibility for self-management of a chronic disorder. See Table 2 for descriptions of challenges and illustrative quotations.

Prioritizing treatment for a chronic disorder with limited signs and symptoms

Five young adults described difficulty prioritizing treatment when the goal was better health later in life. Young adults attributed this difficulty to a variety of factors, including underestimating their long-term risk for CVD events, the propensity of young adults to focus their energy on addressing other more pressing issues, and perceptions of FH treatment as inconvenient and potentially socially isolating. Ten parents identified myriad challenges for their child with FH to prioritize self-treatment, including a sense of invincibility, an inability to fully understand how current decisions affect future health, and prioritization of other life elements.

Managing social implications of FH

Ten young adults articulated how concern about peers’ opinions or overt peer pressure-restricted social activities centered around eating. Others endorsed feelings of shame stemming from the belief that having a genetic disorder or being on medication makes one “unhealthy,” whether or not the disorder has physical manifestations. Six parents similarly described seeing these social implications of FH in their children.

Finding credible resources for guidance

All young adults and 10 parents explicitly expressed a need for more credible resources for young adults seeking guidance while transitioning to adult care with FH. Commonly requested resources available outside of face-to-face conversations with a physician or specialized dietary guidance from a nutritionist included reliable health websites, personal stories from individuals in similar medical situations, numerical data for efficacy of different treatment methods, and statistics surrounding a medication’s potential side effects.

It is worth noting that, although the interview guide did not specifically ask about concerns regarding establishing new doctor-patient relationships with an adult care provider, 10 young adults and 8 parents spontaneously mentioned valuing a positive doctor-patient relationship, described how important trusting their doctor was, and cited their physician as the best source of medical information. One young adult explicitly voiced concern over leaving the supportive environment of pediatric care and adjusting to a new adult provider.

Respondent-recommended interventions

In the following section, we describe interventions recommended by respondents. See Table 3 for descriptions of respondent-recommended interventions and illustrative quotations.

Table 3.

Respondent-recommended interventions to improve the health care transition for young adults with FH

| Recommended interventions and endorsement | Description | Illustrative quotations |

|---|---|---|

| Individual- and interpersonal-level interventions | ||

| Increased family involvement; 7 young adults, 8 parents | Increase involvement of family in maintaining lifestyle treatments for FH, such as engaging in healthy exercise and eating behaviors. | My parents, specifically my mom, were really integral in teaching us types of food to eat, and even when we were little we’d always be like, “Mom, I want to eat this.’’ But she’s like, ‘‘No, you can’t eat that,” and she would really put the foot down on it. She taught us to see certain foods as bad and other foods as better, and made sure that now that we are at this age we can eat properly.-Young Adult That’s what you have to teach them growing into adulthood, that a physical activity is a smart thing to do and that it’s more than just smart for your heart-it can make you feel good. It can make you look good (your muscles, that is). And it’s something you can do. it can be social. And so, you know, there are so many reasons why physical activity is good for you. -Parent |

| Increased Peer Involvement; 8 young adults, 8 parents | Increase involvement of peers in maintaining lifestyle treatments for FH, such as engaging in healthy exercise and eating behaviors. | Having like a friend or family member there to support you and push you along. that makes it easier. Not just doing it by yourself. Knowing you’re not the only one.-Young Adult She finds like exercising at the gym very boring.that’s why the enlisting of her siblings and friends has helped [to motivate her to adhere to lifestyle treatment].-Parent |

| Medication routine;7 young adults, 8 parents | Utilize a daily routine to encourage medication adherence. | Definitely the routine [would make medication adherence easier] because it’s one of those things where you have to take it every day and you have to be diligent about it, and if that’s not something that you’re used to doing, starting and remembering would be hard…just beginning that routine [makes it easier to adhere]. because right now it’s habitual for me, it’s what happens. -Young Adult Is it right next to the sink when she wakes up in the morning or is it, you know, with her nighttime snack? Like whatever she does during the day.it’s [the] availability and the reminder. Perhaps some people put a calendar and they check it off every day. I don’t think she does that, but I think if it’s physically right next to where her toothbrush is then she’ll remember it. -Parent |

| Systems-level interventions | ||

| Early engagement in shared decision-making by health care team;10 young adults, 8 parents | Engage affected adolescents earlier in shared decision making regarding treatment. | Your primary care physician probably plays a large role. I mean they’re the ones that went to med school;they probably have the better idea of how medication can affect your body and your health. But at the same time, you, as a patient, you have a significant role in what you want to do. Some people don’t like medication, so they may prefer to do the diet and exercise approach. But I think it has to do with the doctor and patient coming to an agreement on what the best option is, ‘cause like the patient might know what’s best for them in terms of a personal standpoint [and] the doctor may know what’s best for them in terms of a medical treatment standpoint’. So I think they have to have some kind of agreement [and] discussion to figure out what the best treatment option is. -Young Adult I don’t know if 17–21 year olds have the greatest perspective. she [daughter] goes in to see the doctor herself. She comes out, she sort of tells me stuff but she doesn’t write it down, she doesn’t remember exact things. I don’t know, capacity-wise if she’s really ready to handle her own medical care. I think you should do it [engage young adults in shared decision-making with their physicians] earlier. –Parent |

| Resources; 12 young adults, 10 parents | Supply young adults with credible external resources which can be used for guidance during the health care transition. | I think having the resources [would make it easy to adhere to lifestyle treatments]… like seeing a nutritionist that can give you options and be like, “These are good foods. This is what you need to do.” Kind of like guidelines in order to help you start that change… -Young Adult I would want to know what cholesterol was. I would want to know what they [the physicians] are checking for and what the range is, what the healthy range is, and if my child is at risk, what I could do... so they could come up with pamphlets, handouts, they have it for other things. -Parent |

| Blood tests; 8 young adults, 7 parents | Use frequent blood tests to monitor cholesterol levels, assess the efficacy of treatment, and remind young adults of the importance of adhering to treatment. | Going to the doctor, and being with the doctor with the blood test results in his hand and having him right there, explaining the numbers, was really awesome. -Young Adult He wants to be healthy. So if he’s getting what he needs, he needs that proof. …When he sees the numbers from one set [change] six months later to the next… He needs to see that scientific piece and how it’s connected. He just needs to see that. -Parent |

FH, familial hypercholesterolemia.

Individual- and interpersonal-level interventions focused on increased involvement of family and peers in maintaining lifestyle treatments for FH, such as engaging in healthy exercise and eating behaviors. Respondents also recommended using a set daily routine to encourage medication adherence.

Systems-level interventions included early engagement of affected adolescents in shared decision-making regarding treatment while still under the care of a pediatric subspecialty health care team; supplying young adults with credible external resources, which can be used for guidance during the health care transition; and using frequent blood tests to monitor cholesterol levels, assess efficacy of treatment, and remind young adults about the importance of treatment. Requested resources were not confined to handouts or Web pages, but reflected young adult communication and social media patterns of use, and included digital recordings or other technological modalities regarding how other young adults with FH had adapted to college or professional life.

Discussion

Given the limited literature available to examine the transitioning experience of young adults with FH, this exploratory research identifies 5 challenges faced by these individuals within the context of 2 developmental tasks, the transition from childhood to early adulthood and the assumption of responsibility for self-management of a chronic disorder. These included: (1) recognizing oneself as a decision maker, (2) navigating emerging independence, (3) prioritizing treatment for a chronic disorder with limited signs and symptoms, (4) managing social implications of FH, and (5) finding credible resources for guidance. Young adults and parents were generally concordant with regard to the difficulties associated with acting as a novice decision maker, coping with developmental and disease-specific issues, and finding credible resources but showed differences in their frequency of reporting the 2 remaining challenges. Nearly, all young adults expressed concern over the social implications of having FH, while parents seemed more preoccupied with the difficulty of prioritizing treatment for a long-term disorder. This might be explained by a combination of the heightened importance of peer evaluation experienced during adolescence and the ability of parents to see how past medical decisions have affected their personal health.37 Respondents almost universally reported on their strong relationship with their pediatric subspecialist, with one articulating concern about transitioning to a new adult provider. Considering that all the young adult respondents were recruited from pediatric clinics, it is likely that more respondents would have expressed apprehension regarding adjusting to a new physician had interviewers deliberately asked about it.

Clinical implications

The results of this study have several clinical implications. Providers caring for children and young adults with FH should consider adopting the systems-level interventions recommended by respondents, including early engagement in shared decision-making by the health care team, supplying young adults with credible external resources, and using frequent blood tests to monitor cholesterol levels, assess efficacy of treatment, and remind young adults about the importance of treatment. It should be noted that feedback about one’s lipid values has not been proven to motivate adolescent behavior change in the general population. While one study of healthy adults found more frequent cholesterol testing led to healthier dietary changes,38 another study of healthy adults found participants who received cholesterol testing results made fewer favorable dietary changes compared with those who did not.39 Whether this recommendation from participants in our study would actually be effective for young adults with FH under treatment (lifestyle alone or combined with lipid-lowering therapy) remains an area of future research.

To effectively engage affected adolescents in shared decision-making regarding treatment, pediatric subspecialists should emphasize patient education and self-efficacy in accessing health care services through several steps. First, basic FH-related patient education—including what FH is, how it is treated, and the benefits and risks of treatment options—should be repeated during early and late adolescence and directed at the patient, even if the same information was previously directed at the parent(s). Second, results suggest that pediatric subspecialists should engage adolescents with FH in shared decision-making as early as is developmentally appropriate. The American Academy of Pediatrics, in conjunction with the American College of Physicians and the American Academy of Family Physicians, recommends assessing the transition readiness of all patients beginning at 12 years of age.8 While patients as young as 12 are many years from the transition to adult care, starting the process at this young age allows the pediatric medical home to prepare the individual for many of the tasks required of adults with chronic disease. By engaging the individual in shared decision-making at a young age, the pediatric subspecialist can model this process for the family and support the young person as an emerging decision maker. For example, providers could employ evidence-based practices like teach-back, where patients are asked to provide their understanding of their diagnosis to better gauge their knowledge base, identify any potential gaps in understanding, and develop a mutually agreed-upon treatment plan.40 Third, providers should regularly ask young adults to schedule their own appointments and know their pharmacy and medication doses and should specifically address large transitions in living situations—such as moving away from home, starting a new job, or going away to college—and help them plan how to integrate healthy lifestyle behaviors into their new schedule. Finally, providers should develop a transition plan with the young adult and parent(s), including identifying an adult subspecialty provider, obtaining permission to share medical information with that provider, and having a discussion about the changing roles of the young adult and parent(s) in the young adult’s medical care.8

Respondents also endorsed the need for patient-centered resources that addressed many of the challenges raised. This was not surprising, given the lack of resources identified by the research team before launching the study. The National Alliance to Advance Adolescent Health website Gottransition.org includes testimonials and tips from young adults with a variety of chronic conditions and could serve as a model for FH-specific resource development. FH-specific advocacy groups such as the FH Foundation could focus educational materials toward young adults. Dedicated social media sites where youth can engage with other young adults with FH, similar to those that exist for other chronic conditions such as type 1 diabetes,41,42 could be created so young adults can share tips for managing the disease while dealing with the competing demands of early adulthood. Incorporation of themes related to shared decision-making would naturally align with the young adult’s developmental transition to managing their own care and could build on materials targeting adults available through groups like the Informed Medical Decisions Foundation.43

A review of the literature shows increasing interest in how to facilitate the transition from pediatric to adult health care for young adults with chronic conditions. Our FH-specific findings echo themes from various studies employing quantitative and/or qualitative data in other chronic pediatric disorders. Similar to our research, most of these studies are exploratory in nature. We were unable to find any data comparing transitional needs and experiences across chronic conditions. A recent Cochrane evidence review exploring interventions was only able to identify 4 intervention studies in the literature.44 These interventions for teens with conditions as diverse as spina bifida, congenital heart disease, and type 1 diabetes, ranged from workshops to nurse-led one-on-one coaching and web-based educational platforms. Follow-up of these interventions was short, and outcomes were generally limited to self-reported increases in disease knowledge and self-confidence with disease management. Clearly, this is an area for future research.

Limitations and implications for future research

The findings of this study are limited in their generalizability by several factors: (1) sample size, (2) sample uniformity, and (3) potential bias on the part of the participants and research team. Although a sample size of 24 participants was adequate for thematic saturation among respondents,33 the data cannot reasonably be generalized to all young adults with FH and parents of affected young adults. In addition to being limited by size, the study sample also demonstrates considerable homogeneity. All members of the sample were recruited from the same health system and share many similar demographic characteristics, with the majority being white, having private medical insurance, and displaying a high level of parental involvement in the young adult’s health care. Because we recruited participants from a pediatric subspecialty clinic, we were limited in our ability to examine some transitional issues such as the confusion that may arise when participants encounter providers who apply adult vs pediatric lipid guidelines. In this article, we did not assess the impact of family history or prior treatment on responses; however, we have previously published on the centrality and ways in which family history influenced perceptions of risk and treatment decision-making with this same sample.45 Our analytic approach attempted to decrease bias on the part of the research team through the use of a standardized interview guide, review of all interviews by the qualitative lead on the study (Dr Mackie), and the use of a coding consensus approach. However, interviews were self-reports and subject to recall and social desirability biases.45

Since all members of the study sample were recruited from 1 health system, these findings may not account for the heterogeneity of experiences of all young adults with FH, especially those who are undiagnosed or not engaged in care. Additional studies with young adults with FH in other geographical areas, who are not currently engaged in care and who have already transferred to adult models of care, will be important for expanding this work. Findings from this and other qualitative studies could then be tested as hypotheses using a large-scale, quantitative survey at a national level. If additional research reinforced these results, interventions could be developed and implemented in an effort to ease the transitioning process.

Conclusions

The transition to early adulthood is challenging for all young adults, but particularly for those with chronic disorders. These individuals have needs for support at the individual, interpersonal, and systems levels. For young adults with FH, interventions could help improve the transition to adult care and hopefully support the maintenance of healthy lifestyle behaviors and adherence to medications that could minimize premature CVD events in this high-risk group.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge PCORI and the NIH for all financial support provided. The authors also thank members of the stakeholder panel for the Hyperlipidemia Evaluation and Treatment in Young Adults (HEAR YA) study for their invaluable contributions to the research process.

This research was supported through a Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI) Assessment of Prevention, Diagnosis, and Treatment Options Program Award (#1443), the National Center for Research Resources Award Number UL1RR025752, and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, National Institutes of Health (NIH), Award Numbers UL1TR000073 and UL1TR001064. All statements in this report, including its findings and conclusions, are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of PCORI, its Board of Governors, or Methodology Committee, nor the official views of the NIH. Consistent with priorities of PCORI, stakeholder engagement was considered central to the research process for the parent study.

Footnotes

Supplementary data

Supplementary data related to this article can be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jacl.2016.11.001.

Contributor Information

Samantha K. Sliwinski, Institute for Clinical Research and Health Policy Studies, Tufts Medical Center, Boston, MA, USA.

Holly Gooding, Division of Adolescent/Young Adult Medicine, Boston Children’s Hospital, Boston, MA, USA.

Sarah de Ferranti, Department of Cardiology, Boston Children’s Hospital, Boston, MA, USA.

Thomas I. Mackie, Institute for Health, Health Care Policy and Aging Research, Rutgers University, New Brunswick, NJ, USA; Department of Health Systems and Policy, School of Public Health, Rutgers University, New Brunswick, NJ, USA.

Supriya Shah, Institute for Clinical Research and Health Policy Studies, Tufts Medical Center, Boston, MA, USA.

Tully Saunders, Institute for Clinical Research and Health Policy Studies, Tufts Medical Center, Boston, MA, USA.

Laurel K. Leslie, Institute for Clinical Research and Health Policy Studies, Tufts Medical Center, Boston, MA, USA; Department of Pediatrics, Floating Hospital for Children at Tufts Medical Center, Boston, MA, USA; Tufts Clinical and Translational Science Institute, Tufts Medical Center, Boston, MA, USA; American Board of Pediatrics, Chapel Hill, NC, USA.

References

- 1.Williams CL, Hayman LL, Daniels SR, et al. Cardiovascular health in childhood: A statement for health professionals from the Committee on Atherosclerosis, Hypertension, and Obesity in the Young (AHOY) of the Council on Cardiovascular Disease in the Young, American Heart Association. Circulation. 2002;106(1):143–160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dickey SB, Deatrick J. Autonomy and decision making for health promotion in adolescence. Pediatr Nurs. 2000;26(5):461–467. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chung RJ, Toulomtzis C, Gooding HC. Staying young at heart: cardiovascular disease prevention in adolescents and young adults. Curr Treat Options Cardiovasc Med. 2015;17(12):61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gooding HC, de Ferranti SD. Cardiovascular risk assessment and cholesterol management in adolescents: getting to the heart of the matter; Curr Opin Pediatr. 2010;22(4):398–404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Crockett LJ, Petersen AC. Adolescent development: health risks and opportunities for health promotion In: Millstein SG, Petersen AC, Nightingale EO, editors. Promoting the Health of Adolescents: New Directions for the Twenty-first Century. New York, New York: Oxford University Press, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Liu K, Daviglus ML, Loria CM, et al. Healthy lifestyle through young adulthood and the presence of low cardiovascular disease risk profile in middle age: the Coronary Artery Risk Development in (Young) Adults (CARDIA) study. Circulation. 2012;125(8):996–1004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gooding HC, Shay CM, Ning H, et al. Optimal lifestyle components in young adulthood are associated with maintaining the ideal cardiovascular health profile into middle age. J Am Heart Assoc. 2015;4(11) pii: e002048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.American Academy of Pediatrics, American Academy of Family Physicians, American College of Physicians, & Transitions Clinical Report Authoring Group. Supporting the health care transition from adolescence to adulthood in the medical home. Pediatrics. 2011; 128(1):182–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schwartz LA, Brumley LD, Tuchman LK, et al. Stakeholder validation of a model of readiness for transition to adult care. JAMA Pediatr. 2013;167(10):939–946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sawicki GS, Kelemen S, Weitzman ER. Ready, set, stop: mismatch between self-care beliefs, transition readiness skills, and transition planning among adolescents, young adults, and parents. Clin Pediatr. 2014;53(11):1062–1068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Beal SJ, Nye A, Marraccini A, Biro FM. Evaluation of readiness to transfer to adult healthcare: what about the well adolescent? Healthc (Amst). 2014;2(4):225–231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Crowley R, Wolfe I, Lock K, McKee M. Improving the transition between paediatric and adult healthcare: a systematic review. Arch Dis Child. 1996;96(6):548–553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gleeson H, McCartney S, Lidstone V. Everybody’s business: transition and the role of adult physicians. Clin Med (Lond). 2012;12(6): 561–566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Por J, Goldberg B, Lennox V, Burr P, Barrow J, Dennard L. Transition of care: Health care professionals’ view. J Nurs Manag. 2004;12(5): 354–361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Oskoui M, Wolfson C. Current practice and views of neurologists on the transition from pediatric to adult care. J Child Neurol. 2012; 27(12):1553–1558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Huang JS. Preparing adolescents with chronic disease for transition to adult care: a technology program. Pediatrics. 2014;133(6):1639–1646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Blum R, Garell D, Hodgman CH, et al. Transition from child-centered to adult health-care systems for adolescents with chronic conditions. J Adolesc Health. 1993;14(7):570–576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schwartz LA, Tuchman LK, Hobbie WL, Ginsberg JP. A socialecological model of readiness for transition to adult-oriented care for adolescents and young adults with chronic health conditions. Child Care Health Dev. 2011;37(6):883–895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Garvey KC, Wolpert HA, Laffel LM, Rhodes ET, Wolfsdorf JI, Finkelstein JA. Health care transition in young adults with type 1 diabetes: barriers to timely establishment of adult diabetes care. Endocr Pract. 2013;19(6):946–952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wisk LE, Finkelstein JA, Sawicki GS, et al. Predictors of timing of transfer from pediatric- to adult-focused primary care. JAMA Pediatr. 2015;169(6):e150951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Heery E, Sheehan AM, While AE, Coyne I. Experiences and outcomes of transition from pediatric to adult health care services for young people with congenital heart disease: a systematic review. Congenit Heart Dis. 2015;10(5):413–427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Garvey KC, Telo GH, Needleman JS, Forbes P, Finkelstein JA, Laffel LM. Health care transition in young adults with type 1 diabetes: perspectives of adult endocrinologists in the U.S. Diabetes Care. 2016;39(2):190–197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Agarwal S, Garvey KC, Raymond JK, Schutta MH. Perspectives on care for young adults with type 1 diabetes transitioning from pediatric to adult health systems: a national survey of pediatric endocrinologists. Pediatr Diabetes. 2016. [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kenney LB, Melvin P, Fishman LN, et al. Transition and transfer of childhood cancer survivors to adult care: a national survey of pediatric oncologists. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2017;64(2):346–352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Brown MS, Goldstein JL. Familial hypercholesterolemia: a genetic defect in the low-density lipoprotein receptor. N Engl J Med. 1976; 294(25):1386–1390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Simon Broome Steering Committee. Risk of fatal coronary heart disease in familial hypercholesterolaemia. Scientific Steering Committee on behalf of the Simon Broome Register Group. Br Med J. 1991;303(6807):893–896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Grundy SM, Cleeman JI, Merz CN, et al. Implications of recent clinical trials for the National Cholesterol Education Program Adult Treatment Panel III guidelines. Circulation. 2004;110(2):227–239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sawicki GS, Lukens-Bull K, Yin X, et al. Measuring the transition readiness of youth with special healthcare needs: validation of the TRAQ- Transition Readiness Assessment Questionnaire. J Pediatr Psychol. 2011;36(2):129–133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gooding HC, Rodday AM, Wong JB, et al. Application of pediatric and adult guidelines for treatment of lipid levels among US adolescents transitioning to young adulthood. JAMA Pediatr. 2015;169(6): 569–574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Expert Panel on Integrated Guidelines for Cardiovascular Health and Risk Reduction in Children and Adolescents; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Expert panel on Integrated Guidelines for Cardiovascular Health and Risk Reduction in Children and Adolescents: summary report. Pediatrics. 2011;128(Suppl 5):S213–S256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stone NJ, Robinson JG, Lichtenstein AH, et al. 2013 ACC/AHA guideline on the treatment of blood cholesterol to reduce atherosclerotic cardiovascular risk in adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2014;129:S1–S45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mackie TI, Tse LL, de Ferranti SD, Ryan HR, Leslie LK. Treatment decision-making for adolescents with familial hypercholesterolemia: role of family history and past experiences. J Clin Lipidol. 2015; 9(4):583–593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Guest G, Bunce A, Johnson L. How many interviews are enough? An experiment with data saturation and variability. Field Methods. 2006; 18(1):59–82. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Marks D, Thorogood M, Neil HAW, Humphries SE. A review on the diagnosis, natural history, and treatment of familial hypercholesterolemia. Atherosclerosis. 2003;168(1):1–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Willms DG, Best JA, Taylor DW, et al. A systematic approach for using qualitative methods in primary prevention research. Med Anthropol Q. 1990;4(4):391–409. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Arnett JJ. Emerging adulthood: a theory of development from the late teens through the twenties. Am Psychol. 2000;55(5):469–480. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Offer D, Boxer AM. Normal adolescent development: empirical research findings In: Lewis M, editor. Child and Adolescent Psychiatry: A Comprehensive Textbook. Baltimore, Maryland: Williams & Wilkins, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gemson DH, Sloan RP, Messeri P, Goldberg IJ. A public health model for cardiovascular risk reduction: impact of cholesterol screening with brief nonphysician counseling. Arch Intern Med. 1990;150(5): 985–989. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Strychar IM, Champagne F, Ghadirian P, Bonin A, Jenicek M, Lasater TM. Impact of receiving blood cholesterol test results on dietary change. Am J Prev Med. 1998;14(2):103–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. AHRQ Health Literacy Universal Precautions Toolkit. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; Published January 2015. Updated August 2016. Available at: http://www.ahrq.gov/professionals/quality-patient-safety/quality-resources/tools/literacy-toolkit/index.html. Accessed October 10, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ho YX, O’Connor BH, Mulvaney SA. Features of online health communities for adolescents with type 1 diabetes. West J Nurs Res. 2014; 36(9):1183–1198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hilliard ME, Sparling KM, Hitchcock J, Oser TK, Hood KK. The emerging diabetes online community. Curr Diabetes Rev. 2015; 11(4):261–272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Informed Medical Decisions Foundation. Why Shared Decision Making. Informed Medical Decisions Foundation; 2016 Available at: https://www.informedmedicaldecisions.org/shareddecisionmaking.aspx; 2016. Accessed October 10, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Campbell F, Biggs K, Aldiss SK, et al. Transition of care for adolescents from paediatric services to adult health services. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;4:CD009794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ulin PR, Robinson ET, Tolley EE. Qualitative Methods in Public Health: A Field Guide for Applied Research. San Francisco, California: Jossey-Bass; 2005. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.