Abstract

This narrative review describes the evidence regarding digital health interventions targeting adolescent and young adult (AYA) cancer survivors. We reviewed the published literature for studies involving Internet, mHealth, social media, telehealth, and other digital interventions for AYA survivors. We highlight selected studies to illustrate the state of the research in this unique patient population. Interventions have used various digital modalities to improve health behaviors (eg, physical activity, nutrition, tobacco cessation), enhance emotional well-being, track and intervene on cancer-related symptoms, and improve survivorship care delivery. The majority of studies have demonstrated feasibility and acceptability of digital health interventions for AYA survivors, but few efficacy studies have been conducted. Digital health interventions are promising to address unmet psychosocial and health information needs of AYA survivors. Researchers should use rigorous development and evaluation methods to demonstrate the efficacy of these approaches to improve health outcomes for AYA survivors.

INTRODUCTION

Digital health can be broadly defined as the use of technology in the promotion, prevention, treatment, and maintenance of health and health care.1,2 Digital health includes electronic health (eHealth), mobile health (mHealth), health information technology, wearable devices, telehealth, and telemedicine. Such technology can be used in multiple ways, including for information delivery, two-way communication, or longitudinal assessment.3 Digital health is particularly relevant for adolescents and young adults (AYAs), who are pervasive users of technology. In the general population, 93% of adolescents ages 13 to 17 years and 99% of young adults ages 18 to 29 years use the Internet.4,5 Most connect to the Internet with mobile devices; 88% of teenagers and 98% of young adults are smartphone or cell phone users. In addition, the vast majority of teens (89%) and young adults (90%) report using at least one social media site (eg, Facebook, Instagram, Snapchat, Twitter).4

AYA cancer survivors are a growing group of survivors ages 15 to 39 years who were diagnosed with cancer during childhood, adolescence, or young adulthood.6 There are over 379,000 childhood cancer survivors in the United States, and approximately one in every 530 young adults ages 20 to 39 years is a cancer survivor.7 The AYA years are a unique developmental period characterized by autonomy and identity development, pursuit of education and career goals, establishment of financial independence, independent living, and formation of intimate relationships.8 It is also a period of increasing mental health problems and risk-taking behaviors.9 AYA cancer survivors face multiple challenges including disruptions to education, employment, and social milestones, and coping with ongoing late effects from their treatment.10,11 A majority of survivors will develop at least one chronic health condition12 that will require life-long follow-up care. However, AYAs are often lost to follow-up, do not have adequate knowledge of their cancer treatment history and late-effects risks,13 and engage in health-compromising behaviors at rates similar to their peers.14,15 Thus, interventions to improve AYA survivors’ health behaviors and address their unmet psychosocial needs are greatly needed.16,17

Digital health interventions have been increasingly examined to overcome barriers to AYA survivors’ participation in health promotion interventions, including their geographic mobility, relatively small number of AYAs at single institutions, and lack of time and competing priorities.18 Such technology aligns well with AYA preferences for program delivery, use of technology in their daily lives, and use of technology for seeking health information and support.19-22 For example, up to 92% of AYA survivors use the Internet to seek health information, but have concerns about trustworthiness of the information and lack of tailoring to their needs.23 AYA survivors also use mobile devices and online support forums to exchange emotional and informational support and to connect with other survivors.19,24

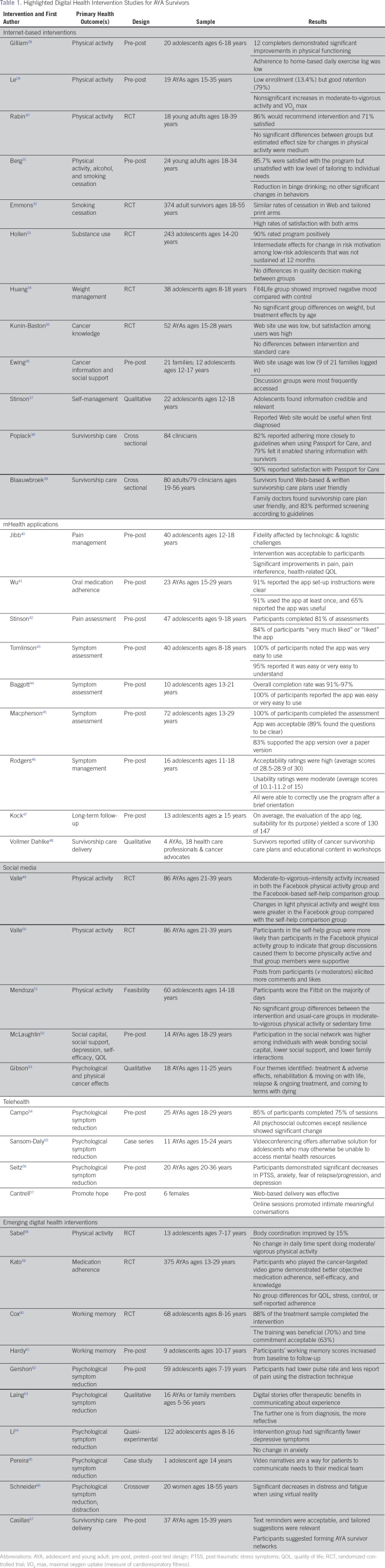

In this review, we extend prior reviews of psychological and health promotion interventions for AYA cancer survivors16,17,25-27 to examine the evidence for digital health interventions targeting AYA survivors. We searched PubMed and Google Scholar using combinations of the following search terms: adolescent, young adult, cancer, survivor, digital, eHealth, mHealth, telehealth, and social media. We also reviewed the reference lists of published studies for additional relevant articles. We highlight primary results from select studies that use the Internet, mHealth, social media, telehealth, and other emerging digital modalities to illustrate the state of the research targeting this unique patient population (Table 1). As can be seen by the studies described, this is an emerging area of research primarily composed of feasibility studies with methodologic weaknesses, such as a lack of control groups and small sample sizes.

Table 1.

Highlighted Digital Health Intervention Studies for AYA Survivors

INTERNET INTERVENTIONS

Early applications of digital health interventions included static Web sites or CD-ROMs.33,36 More recent applications incorporate sophisticated elements of engagement within Web sites (eg, interactive tools, media, and gamification) or other digital health components (eg, text or short messaging service) delivered in conjunction with Web sites.37 Internet-based interventions have been used to translate evidence-based interventions to the digital realm to increase access and convenience for participants, as well as reduce provider resources and costs needed to deliver interventions. For example, a randomized trial of a Web-based versus print smoking cessation intervention for young adult survivors of childhood and adolescent cancers demonstrated equivalency in cessation rates and quit attempts.32 These results support the use of the Internet to scale efficacious interventions.

Internet interventions have also been used as adjuncts to telephone or in-person interventions. For example, a weight loss intervention for child and adolescent acute lymphoblastic leukemia survivors used a combination of Web, text, and telephone counseling to promote weight loss and improve physical activity.34 Other Internet interventions have targeted health promotion behaviors among AYA survivors using a custom-designed Web site,31 an adapted version of an effective Web-based program designed for adults,30 or a commercially available fitness tracker and Web site.29

Although the Internet offers great promise in delivering high-quality and tailored information to AYA survivors and increasing engagement outside of in-person meetings, a major challenge is the reliance on the user to initiate use.68 A randomized pilot study of a Web-based portal to provide AYA cancer survivors with tailored treatment summaries and guidance regarding risk for late effects had low usage, with only 46% accessing the Web site and, of those, only one third logging in more than once.35 Gilliam et al28 demonstrated the feasibility of a Web-based token economy to promote adherence to a community-based face-to-face exercise intervention for child and adolescent survivors, but the intervention did not increase adherence to home exercise between sessions.

Although the majority of Internet interventions have focused on survivors, several studies targeted providers to improve the delivery of survivorship care. In the United States, the Passport for Care Web-based clinical tool was developed for providers to create individual patient survivorship care plans using guidelines-based recommendations for follow-up care.36 Evaluation of a patient-focused portal is ongoing.36 Similarly, in the Netherlands, a Web-based survivorship care plan portal was created to enhance communication among oncologists, family medicine providers, and survivors promoting guidelines-based shared care for long-term follow-up.39

In sum, the Internet offers great promise in terms of convenience, access, and opportunities for engagement in behavioral interventions. There are few rigorously designed studies to make conclusions regarding the efficacy of Internet interventions for AYA survivors. However, it is encouraging that recent reviews have found evidence for the efficacy of Internet interventions in related areas (eg, improving mental health in adults,68 health outcomes in pediatrics69).

mHEALTH APPLICATIONS

mHealth interventions have used text messaging/short messaging service or mobile applications (apps) to deliver interventions targeting a variety of health outcomes. One study examined the feasibility of using text message reminders to increase compliance with survivorship care recommendations and resource use.67 Participants found the text messages to be acceptable, and they recommended adding a social networking component to the program.67 Smartphone apps for AYA cancer survivors have targeted cancer-related symptoms, medication taking, post-treatment follow-up and survivorship, and other health behaviors. A main area of focus has been symptom assessment and management. Existing apps enable AYA patients to record ongoing symptoms, including pain,40,42 mucositis,43 or multiple symptoms.44,45 For example, Macpherson et al45 pilot tested an app that assessed a range of possible symptoms and provided a personalized visualization of symptom clusters. Preliminary evaluations of such symptom assessment apps indicate that they are feasible in terms of the time required to complete the symptom assessment and acceptable to patients in terms of ease; patients were also generally compliant with prompts to complete the electronic assessments.43-45

Other apps have built on assessment to also provide real-time symptom management interventions.40,46 For example, Stinson et al42 piloted an app for pain assessment with adolescent patients with cancer that incorporated a game-based reward system. The assessment app was feasibly deployed, and adolescents reported high satisfaction. In a follow-up study, adolescents using the app received automated messages related to pain management when they reported experiencing pain. If participants reported persistent pain, a nurse contacted the adolescent to discuss other pain management strategies, such as potential medication changes.40

In addition to symptom assessment and management, apps have been used to target other health behaviors, such as medication adherence and compliance with follow-up care. Results of initial feasibility and acceptability studies indicate that AYA patients find such apps easy to use.41,47 For example, 91% of participants offered an app to prompt oral medication taking used the app at least once, and 74% reported that the reminders provided by the app helped them to take their oral medications as prescribed.41 Apps have also been used as part of a larger intervention package, including in an AYA cancer survivorship program with educational components for providers, advocates, survivors, and their families.48 In this latter example, the app provided survivors with information on health behaviors and survivorship care plans.

Given the widespread use of smartphones among AYAs in general,4 apps offer a ubiquitous medium through which to deliver interventions for AYA survivors. Studies on app use in this population thus far have focused primarily on single-site, pretesting/post-testing designs, with initial feasibility and acceptability metrics. As the field develops, multisite studies and efficacy trials will be essential for extending the generalizability of results and documenting the symptom or health behavior outcomes associated with app use. Future work should also examine the potential benefits of using apps to connect survivors with support networks (eg, peers, their families), health care providers, and other digital health technologies (eg, fitness trackers, electronic medical record systems) in real-time across multiple settings.

SOCIAL MEDIA

Social media platforms can be used in health behavior interventions to reach diverse groups without geographic restrictions, provide a forum for information dissemination and exchange, and enable provision of support from peers, family, and health professionals. There is accumulating evidence from studies across target populations that interventions delivered via social media platforms have significant potential to facilitate health communications and promote an array of health-related behaviors.70

Among AYA survivors, social media health promotion research has thus far primarily used Facebook. In an early study, Valle et al49 conducted a randomized controlled trial of a Facebook-based physical activity intervention versus a self-help comparison among young adult cancer survivors. Self-reported moderate to vigorous physical activity increased equally in both groups over a 12-week period, although the participants in the Facebook group had significantly greater increases in light physical activity. Similar to other studies of social media–based interventions with different populations, participant engagement decreased over the course of the intervention, and greater engagement was positively associated with changes in physical activity.50 Several other recent pilot studies demonstrated encouraging feasibility results of Facebook-based interventions for AYA cancer survivors, but they have provided limited evidence of their efficacy with regard to increasing self-reported or objectively measured physical activity.29,51

In terms of other social media platforms, video-based approaches have been used in a number of studies. For example, McLaughlin et al52 developed their own social media site (LIFECommunity) for young adult cancer survivors that allowed individuals to create a blog and share messages, photographs, and videos with other participants. Participants were encouraged to create and share video narratives on different topics (eg, communicating with health care providers, coping with cancer). Participants with weaker face-to-face family and friend social networks used the social media site to a greater degree than individuals with stronger social networks. Interestingly, participants with preexisting strong social connections with other cancer survivors also used the site to a greater degree than individuals with fewer such connections.52 Thus, engagement in social media sites may serve the dual purpose of fulfilling potential deficits in support from family and friends and reaffirming or bolstering support from other cancer survivors.

Observing AYA survivors’ use of existing social media platforms may lead to novel insights on how survivors express and receive social support in these digital mediums. For example, researchers have examined the content of posts in Twitter communities using cancer hashtags,71 online cancer support forums,24 and video diaries in an online support community.53 A list of organizations that use social media platforms to connect with AYA cancer survivors and other interested individuals is available elsewhere.21

Overall, social media–based research related to AYA cancer survivors is in its early stages and has consisted primarily of small-scale pilot and feasibility studies. Future studies should use larger sample sizes, rigorous research designs, and both subjective and objective outcome measures when possible, and expand to consider a broad array of social media platforms that may appeal to AYA cancer survivors (eg, Instagram, Snapchat).

TELEHEALTH

Telehealth is the use of technology such as videoconferencing to connect two or more individuals (eg, AYA survivor and health care provider) in replacement of an in-person connection.3 For example, an Internet cognitive-behavioral intervention to reduce post-traumatic stress symptoms and anxiety had AYA survivors engage in writing sessions online and connected them virtually with a therapist.56 Similarly, group-based interventions have been successfully delivered using online videoconferencing. One example is a nurse-led intervention to enhance hope among young adult survivors of childhood cancer.57 Another example is an instructor-led mindfulness-based self-compassion group intervention to reduce distress and improve psychosocial outcomes.54 This study primarily recruited via social media, demonstrating the feasibility of recruiting and intervening online. Although there are ethical and clinical challenges associated with providing psychotherapy online, giving hard-to-reach groups access to evidence-based interventions is a major advantage.55

Telehealth interventions have also been examined as a strategy for overcoming patient and provider barriers to long-term follow-up care. One study tested the feasibility of a telemedicine transition visit using videoconferencing between a primary care provider and a member of a survivorship care team. Primary care physician and AYA cancer survivor dyads communicated with a pediatric survivorship clinic team member who reviewed the patient’s treatment summary and survivorship care plan. Patients and providers rated the intervention highly, but technologic limitations curtailed the feasibility of this model.72

EMERGING DIGITAL HEALTH INTERVENTIONS

Emerging areas include the use of digital storytelling, video gaming, and virtual reality to address psychosocial and health care utilization concerns of AYA survivors. Digital storytelling involves the creation of a video narrative or personal story through the use of computer and multimedia tools combining video, images, music, voice narration, or other sounds. A qualitative study of 16 AYA survivors and their family members found that the process of creating a digital story provided AYAs and their family members new ways to communicate about and make meaning of their cancer experience.63 The results of a case study of an adolescent who created a video narrative demonstrated similar therapeutic benefits.65

Video gaming has been explored as an intervention for physical activity and adherence for AYA survivors. For example, 13 adolescent brain tumor survivors participated in an active video gaming intervention with videoconference coaching to improve physical activity.58 Despite small to modest improvements in energy expenditure and body composition, high patient-reported satisfaction with the coaching component provided preliminary support for this method of delivery.58 Another video game intervention was used with AYAs to increase medication adherence by targeting behavioral correlates, including self-efficacy and locus of control. This 375-participant, multicenter randomized controlled trial (RCT) showed significantly improved levels of adherence among the intervention group.59 Computerized cognitive remediation uses game-like exercises to improve working memory and has shown promise for acute lymphoblastic leukemia and brain tumor survivors.60,61 Virtual reality has been used to reduce anxiety and depression during medical procedures and chemotherapy for younger62,64 and older adult66 cancer populations. Future exploration of virtual reality for AYA survivors is warranted.

SUMMARY AND FUTURE DIRECTIONS

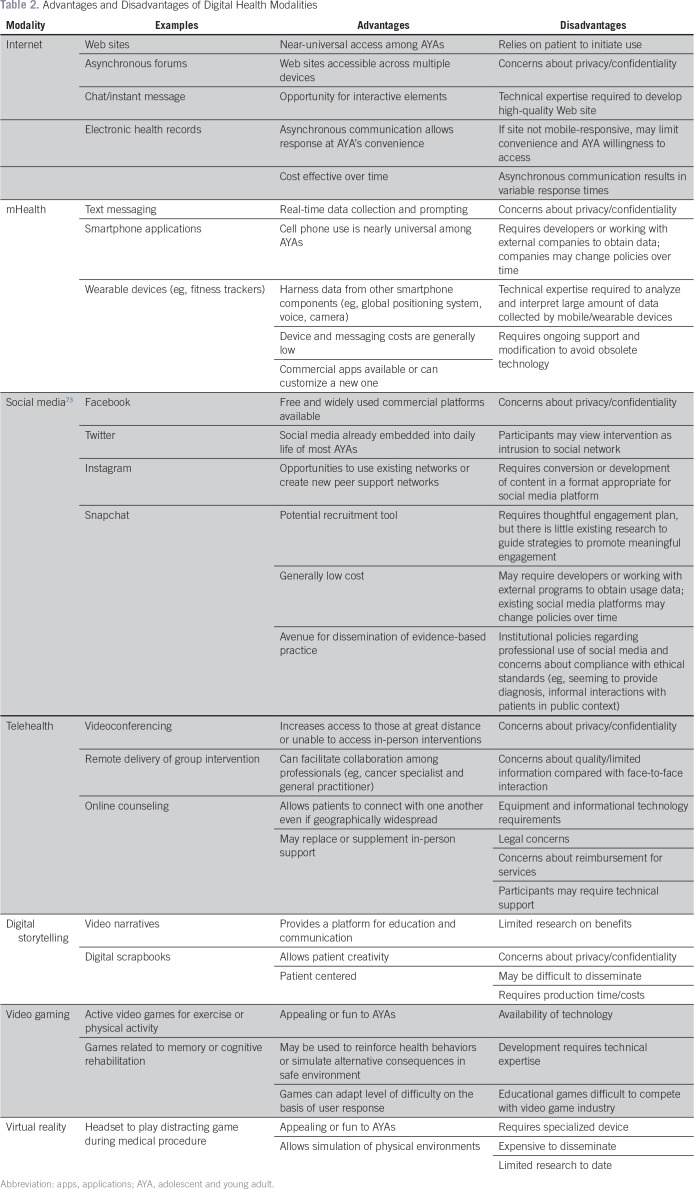

Digital health technology offers immense promise for improving care and outcomes among AYA survivors across a variety of domains. Advantages and disadvantages of different digital modalities are listed in Table 2. Investigators should carefully consider the goal of the intervention; the purpose of the technology (eg, to provide information, to prompt adherence to an intervention, to connect AYA survivors with peer support, to replace face-to-face counseling); the suitability of available commercial platforms versus custom products; resources for developing, maintaining, and analyzing data from the technology; and any training or support required to implement the intervention to select the most appropriate platform.73,74 Notably, health behavior change theory and techniques can be applied in any modality, although some modalities may be advantageous for certain techniques (eg, interventions relying on prompts may prefer to use mobile apps or text messaging in response to triggers collected from mobile data, whereas interventions proposing to change social norms may prefer to use a social media platform).

Table 2.

Advantages and Disadvantages of Digital Health Modalities

The digital health interventions reviewed in this article targeted a range of health behaviors and outcomes, including physical activity, risk behaviors, psychosocial well-being, symptom management, and survivorship delivery and care. These interventions mostly demonstrated feasibility and acceptability among AYA survivors, but rigorous efficacy studies have generally not yet been conducted. Future work should address important AYA-specific concerns, such as successful health care transition (eg, to adult providers or to primary care providers); reproductive health and family planning; and promoting the social, economic, and employment outcomes of AYA patients with cancer.10 Despite the distinct psychological, developmental, and resource needs for this group, few studies have targeted AYA cancer survivors exclusively (instead of grouping them with a broader age range of adult or pediatric survivors).

Characteristic of early intervention work, the studies reviewed primarily used single-arm and feasibility designs. The majority of RCTs conducted thus far tested Internet interventions, which were one of the earlier digital health modalities established. Although RCTs are the traditional gold standard in research, the relatively slow nature of these designs poses problems with outdated and changing technology by the end of the trial.75 Other rigorous research designs have been recommended to optimize technology-based interventions, including single-case or n-of-1 designs, factorial designs, and sequential multiple assignment randomized trials (for review, see Dallery et al75).

Engaging AYA cancer survivors is challenging18,35,76; thus, future digital health interventions should consider methods for enhancing user engagement, which can be assessed subjectively (eg, using surveys or interviews with participants) and objectively (eg, frequency and duration of logins, proportion of intervention material viewed). There are insufficient data from studies of AYA cancer survivors to draw conclusions about user engagement. However, results of studies from other populations suggest that user engagement is positively associated with the efficacy of digital interventions.77 A variety of approaches have been found to enhance user engagement, including gamification, use of prompts, and tailoring of content.78-80

In conclusion, the research to date is promising in that many digital health interventions are feasible and acceptable to AYA survivors. However, more work is needed to evaluate the effectiveness of such interventions in changing behaviors and improving health outcomes. There are many ongoing trials of digital health interventions for this group, particularly in mHealth and multicomponent Internet interventions. We recommend involving AYAs early in the development and usability testing of digital health interventions to gain valuable feedback in creating a feasible intervention.37 We recommend the use of a staged framework to design and evaluate a new intervention, focusing on understanding user and design needs,81 to help researchers decide whether and how to develop digital health solutions for AYA survivors. Although technology poses challenges in terms of the rapidly changing landscape of technical advances (in contrast to the slower speed of academic research) and the initial and ongoing expense of maintaining technology, there are numerous advantages that make it particularly powerful for AYA survivors. As technology is increasingly included in or becoming the primary modality of behavioral interventions, we recommend a team science approach to designing and implementing these interventions, including (but not limited to) behavioral scientists, computer scientists/human-computer interaction specialists, biostatisticians experienced in big data analysis, and mHealth/social media experts.

Footnotes

Supported in part by the National Cancer Institute of the National Institutes of Health (K07CA174728 to K.A.D., K07CA196985 to Y.P.W.). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conception and design: All authors

Financial support: Katie A. Devine, Yelena P. Wu

Collection and assembly of data: All authors

Data analysis and interpretation: All authors

Manuscript writing: All authors

Final approval of manuscript: All authors

Accountable for all aspects of the work: All authors

AUTHORS' DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The following represents disclosure information provided by authors of this manuscript. All relationships are considered compensated. Relationships are self-held unless noted. I = Immediate Family Member, Inst = My Institution. Relationships may not relate to the subject matter of this manuscript. For more information about ASCO's conflict of interest policy, please refer to www.asco.org/rwc or ascopubs.org/jco/site/ifc.

Katie A. Devine

No relationship to disclose

Adrienne S. Viola

No relationship to disclose

Elliot J. Coups

Research Funding: Johnson & Johnson

Yelena P. Wu

No relationship to disclose

REFERENCES

- 1.US Food and Drug Administration Digital health. https://www.fda.gov/MedicalDevices/DigitalHealth/default.htm

- 2.Karlson CW, Palermo TM. eHealth and mHealth in pediatric oncology, in Abrams AN (ed): Pediatric Psychosocial Oncology: Textbook for Multidisciplinary Care. Cham, Switzerland, Springer International Publishing, 2016, pp. :351–365. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cushing CC. eHealth applications in pediatric psychology, in Roberts MC, Steele RG (eds): Handbook of Pediatric Psychology. New York, NY, The Guilford Press, 2017, pp. :201–211. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lenhart A. Teens, social media & technology overview 2015. http://www.pewinternet.org/2015/04/09/teens-social-media-technology-2015/

- 5.Pew Research Center http://www.pewinternet.org/fact-sheet/internet-broadband/

- 6.Thomas DM, Albritton KH, Ferrari A. Adolescent and young adult oncology: An emerging field. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:4781–4782. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.30.5128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ward E, DeSantis C, Robbins A, et al. Childhood and adolescent cancer statistics, 2014. CA Cancer J Clin. 2014;64:83–103. doi: 10.3322/caac.21219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Arnett JJ. Emerging adulthood. A theory of development from the late teens through the twenties. Am Psychol. 2000;55:469–480. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Park MJ, Scott JT, Adams SH, et al. Adolescent and young adult health in the United States in the past decade: Little improvement and young adults remain worse off than adolescents. J Adolesc Health. 2014;55:3–16. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2014.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zebrack B, Isaacson S. Psychosocial care of adolescent and young adult patients with cancer and survivors. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:1221–1226. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.39.5467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Barr RD, Ferrari A, Ries L, et al. Cancer in adolescents and young adults: A narrative review of the current status and a view of the future. JAMA Pediatr. 2016;170:495–501. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2015.4689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Oeffinger KC, Mertens AC, Sklar CA, et al. Chronic health conditions in adult survivors of childhood cancer. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:1572–1582. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa060185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Henderson TO, Friedman DL, Meadows AT. Childhood cancer survivors: Transition to adult-focused risk-based care. Pediatrics. 2010;126:129–136. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-2802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Klosky JL, Howell CR, Li Z, et al. Risky health behavior among adolescents in the childhood cancer survivor study cohort. J Pediatr Psychol. 2012;37:634–646. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jss046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Badr H, Chandra J, Paxton RJ, et al. Health-related quality of life, lifestyle behaviors, and intervention preferences of survivors of childhood cancer. J Cancer Surviv. 2013;7:523–534. doi: 10.1007/s11764-013-0289-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bradford NK, Chan RJ. Health promotion and psychological interventions for adolescent and young adult cancer survivors: A systematic literature review. Cancer Treat Rev. 2017;55:57–70. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2017.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pugh G, Gravestock HL, Hough RE, et al. Health behavior change interventions for teenage and young adult cancer survivors: A systematic review. J Adolesc Young Adult Oncol. 2016;5:91–105. doi: 10.1089/jayao.2015.0042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rabin C, Horowitz S, Marcus B. Recruiting young adult cancer survivors for behavioral research. J Clin Psychol Med Settings. 2013;20:33–36. doi: 10.1007/s10880-012-9317-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Abrol E, Groszmann M, Pitman A, et al. Exploring the digital technology preferences of teenagers and young adults (TYA) with cancer and survivors: A cross-sectional service evaluation questionnaire. J Cancer Surviv. 2017;11:670–682. doi: 10.1007/s11764-017-0618-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Barakat LP, Galtieri LR, Szalda D, et al Assessing the psychosocial needs and program preferences of adolescents and young adults with cancer. Support Care Cancer. 2016;24:823–832. doi: 10.1007/s00520-015-2849-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Perales MA, Drake EK, Pemmaraju N, et al. Social media and the adolescent and young adult (AYA) patient with cancer. Curr Hematol Malig Rep. 2016;11:449–455. doi: 10.1007/s11899-016-0313-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Treadgold CL, Kuperberg A. Been there, done that, wrote the blog: The choices and challenges of supporting adolescents and young adults with cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:4842–4849. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.23.0516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mooney R, Samhouri M, Holton A, et al. Adolescent and young adult cancer survivors’ perspectives on their Internet use for seeking information on healthy eating and exercise. J Adolesc Young Adult Oncol. 2017;6:367–371. doi: 10.1089/jayao.2016.0059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Love B, Crook B, Thompson CM, et al. Exploring psychosocial support online: A content analysis of messages in an adolescent and young adult cancer community. Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw. 2012;15:555–559. doi: 10.1089/cyber.2012.0138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Barnett M, McDonnell G, DeRosa A, et al. Psychosocial outcomes and interventions among cancer survivors diagnosed during adolescence and young adulthood (AYA): A systematic review. J Cancer Surviv. 2016;10:814–831. doi: 10.1007/s11764-016-0527-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kopp LM, Gastelum Z, Guerrero CH, et al. Lifestyle behavior interventions delivered using technology in childhood, adolescent, and young adult cancer survivors: A systematic review. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2017;64:13–17. doi: 10.1002/pbc.26166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wesley KM, Fizur PJ. A review of mobile applications to help adolescent and young adult cancer patients. Adolesc Health Med Ther. 2015;6:141–148. doi: 10.2147/AHMT.S69209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gilliam MB, Ross K, Futch L, et al. A pilot study evaluation of a web‐based token economy to increase adherence with a community‐based exercise intervention in child and adolescent cancer survivors. Rehabil Oncol. 2011;29:16–22. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Le A, Mitchell HR, Zheng DJ, et al. A home-based physical activity intervention using activity trackers in survivors of childhood cancer: A pilot study. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2017;64:387–394. doi: 10.1002/pbc.26235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rabin C, Dunsiger S, Ness KK, et al. Internet-based physical activity intervention targeting young adult cancer survivors. J Adolesc Young Adult Oncol. 2011;1:188–194. doi: 10.1089/jayao.2011.0040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Berg CJ, Stratton E, Giblin J, et al. Pilot results of an online intervention targeting health promoting behaviors among young adult cancer survivors. Psycho-oncology. 2014;23:1196–1199. doi: 10.1002/pon.3526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Emmons KM, Puleo E, Sprunck-Harrild K, et al. Partnership for health-2, a Web-based versus print smoking cessation intervention for childhood and young adult cancer survivors: Randomized comparative effectiveness study. J Med Internet Res. 2013;15:e218. doi: 10.2196/jmir.2533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hollen PJ, Tyc VL, Donnangelo SF, et al. A substance use decision aid for medically at-risk adolescents: Results of a randomized controlled trial for cancer-surviving adolescents. Cancer Nurs. 2013;36:355–367. doi: 10.1097/NCC.0b013e31827910ba. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Huang JS, Dillon L, Terrones L, et al. Fit4Life: A weight loss intervention for children who have survived childhood leukemia. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2014;61:894–900. doi: 10.1002/pbc.24937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kunin-Batson A, Steele J, Mertens A, et al. A randomized controlled pilot trial of a Web-based resource to improve cancer knowledge in adolescent and young adult survivors of childhood cancer. Psychooncology. 2016;25:1308–1316. doi: 10.1002/pon.3956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ewing LJ, Long K, Rotondi A, et al. Brief report: A pilot study of a web-based resource for families of children with cancer. J Pediatr Psychol. 2009;34:523–529. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsn096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Stinson J, Gupta A, Dupuis F, et al. Usability testing of an online self-management program for adolescents with cancer. J Pediatr Oncol Nurs. 2015;32:70–82. doi: 10.1177/1043454214543021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Poplack DG, Fordis M, Landier W, et al. Childhood cancer survivor care: Development of the Passport for Care. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2014;11:740–750. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2014.175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Blaauwbroek R, Barf HA, Groenier KH, et al. Family doctor-driven follow-up for adult childhood cancer survivors supported by a Web-based survivor care plan. J Cancer Surviv. 2012;6:163–171. doi: 10.1007/s11764-011-0207-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jibb LA, Stevens BJ, Nathan PC, et al. Implementation and preliminary effectiveness of a real-time pain management smartphone app for adolescents with cancer: A multicenter pilot clinical study. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2017;64:e26554. doi: 10.1002/pbc.26554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wu YP, Linder LA, Kanokvimankul P, et al. Use of a smartphone application for prompting oral medication adherence among adolescents and young adults with cancer. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2018;45:69–76. doi: 10.1188/18.ONF.69-76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Stinson JN, Jibb LA, Nguyen C, et al. Development and testing of a multidimensional iPhone pain assessment application for adolescents with cancer. J Med Internet Res. 2013;15:e51. doi: 10.2196/jmir.2350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tomlinson D, Hesser T, Maloney AM, et al. Development and initial evaluation of electronic Children's International Mucositis Evaluation Scale (eChIMES) for children with cancer. Support Care Cancer. 2014;22:115–119. doi: 10.1007/s00520-013-1953-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Baggott C, Gibson F, Coll B, et al. Initial evaluation of an electronic symptom diary for adolescents with cancer. JMIR Res Protoc. 2012;1:e23. doi: 10.2196/resprot.2175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Macpherson CF, Linder LA, Ameringer S, et al. Feasibility and acceptability of an iPad application to explore symptom clusters in adolescents and young adults with cancer. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2014;61:1996–2003. doi: 10.1002/pbc.25152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rodgers CC, Krance R, Street RL, Jr, et al. Feasibility of a symptom management intervention for adolescents recovering from a hematopoietic stem cell transplant. Cancer Nurs. 2013;36:394–399. doi: 10.1097/NCC.0b013e31829629b5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kock AK, Kaya RS, Müller C, et al. Design, implementation, and evaluation of a mobile application for patient empowerment and management of long-term follow-up after childhood cancer. Klin Padiatr. 2015;227:166–170. doi: 10.1055/s-0035-1548840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Vollmer Dahlke D, Fair K, Hong YA, et al. Adolescent and young adult cancer survivorship educational programming: A qualitative evaluation. JMIR Cancer. 2017;3:e3. doi: 10.2196/cancer.5821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Valle CG, Tate DF, Mayer DK, et al. A randomized trial of a Facebook-based physical activity intervention for young adult cancer survivors. J Cancer Surviv. 2013;7:355–368. doi: 10.1007/s11764-013-0279-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Valle CG, Tate DF. Engagement of young adult cancer survivors within a Facebook-based physical activity intervention. Transl Behav Med. 2017;7:667–679. doi: 10.1007/s13142-017-0483-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mendoza JA, Baker KS, Moreno MA, et al. A Fitbit and Facebook mHealth intervention for promoting physical activity among adolescent and young adult childhood cancer survivors: A pilot study. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2017;64:e26660. doi: 10.1002/pbc.26660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.McLaughlin M, Nam Y, Gould J, et al. A videosharing social networking intervention for young adult cancer survivors. Comput Human Behav. 2012;28:631–641. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gibson F, Hibbins S, Grew T, et al. How young people describe the impact of living with and beyond a cancer diagnosis: Feasibility of using social media as a research method. Psychooncology. 2016;25:1317–1323. doi: 10.1002/pon.4061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Campo RA, Bluth K, Santacroce SJ, et al. A mindful self-compassion videoconference intervention for nationally recruited posttreatment young adult cancer survivors: Feasibility, acceptability, and psychosocial outcomes. Support Care Cancer. 2017;25:1759–1768. doi: 10.1007/s00520-017-3586-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sansom‐Daly UM, Wakefield CE, McGill BC, et al. Ethical and clinical challenges delivering group‐based cognitive‐behavioural therapy to adolescents and young adults with cancer using videoconferencing technology. Aust Psychol. 2015;50:271–278. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Seitz DC, Knaevelsrud C, Duran G, et al. Efficacy of an Internet-based cognitive-behavioral intervention for long-term survivors of pediatric cancer: A pilot study. Support Care Cancer. 2014;22:2075–2083. doi: 10.1007/s00520-014-2193-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Cantrell MA, Conte T. Enhancing hop among early female survivors of childhood cancer via the Internet: A feasibility study. Cancer Nurs. 2008;31:370–379. doi: 10.1097/01.NCC.0000305766.42475.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sabel M, Sjölund A, Broeren J, et al. Active video gaming improves body coordination in survivors of childhood brain tumours. Disabil Rehabil. 2016;38:2073–2084. doi: 10.3109/09638288.2015.1116619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kato PM, Cole SW, Bradlyn AS, et al. A video game improves behavioral outcomes in adolescents and young adults with cancer: A randomized trial. Pediatrics. 2008;122:e305–e317. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-3134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Cox LE, Ashford JM, Clark KN, et al. Feasibility and acceptability of a remotely administered computerized intervention to address cognitive late effects among childhood cancer survivors. Neurooncol Pract. 2015;2:78–87. doi: 10.1093/nop/npu036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hardy KK, Willard VW, Bonner MJ. Computerized cognitive training in survivors of childhood cancer: A pilot study. J Pediatr Oncol Nurs. 2011;28:27–33. doi: 10.1177/1043454210377178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Gershon J, Zimand E, Pickering M, et al. A pilot and feasibility study of virtual reality as a distraction for children with cancer. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2004;43:1243–1249. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000135621.23145.05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Laing CM, Moules NJ, Estefan A, et al. Stories that heal: Understanding the effects of creating digital stories with pediatric and adolescent/young adult oncology patients. J Pediatr Oncol Nurs. 2017;34:272–282. doi: 10.1177/1043454216688639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Li WH, Chung JO, Ho EK. The effectiveness of therapeutic play, using virtual reality computer games, in promoting the psychological well-being of children hospitalised with cancer. J Clin Nurs. 2011;20:2135–2143. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2011.03733.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Pereira LM, Muench A, Lawton B. The impact of making a video cancer narrative in an adolescent male: A case study. Arts Psychother. 2017;55:195–201. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Schneider SM, Prince-Paul M, Allen MJ, et al. Virtual reality as a distraction intervention for women receiving chemotherapy. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2004;31:81–88. doi: 10.1188/04.ONF.81-88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Casillas J, Goyal A, Bryman J, et al. Development of a text messaging system to improve receipt of survivorship care in adolescent and young adult survivors of childhood cancer. J Cancer Surviv. 2017;11:505–516. doi: 10.1007/s11764-017-0609-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Mohr DC, Burns MN, Schueller SM, et al. Behavioral intervention technologies: Evidence review and recommendations for future research in mental health. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2013;35:332–338. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2013.03.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Cushing CC, Steele RG. A meta-analytic review of eHealth interventions for pediatric health promoting and maintaining behaviors. J Pediatr Psychol. 2010;35:937–949. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsq023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Chou WY, Hunt YM, Beckjord EB, et al. Social media use in the United States: Implications for health communication. J Med Internet Res. 2009;11:e48. doi: 10.2196/jmir.1249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Myrick JG, Holton AE, Himelboim I, et al. #Stupidcancer: Exploring a typology of social support and the role of emotional expression in a social media community. Health Commun. 2016;31:596–605. doi: 10.1080/10410236.2014.981664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Costello AG, Nugent BD, Conover N, et al. Shared care of childhood cancer survivors: A telemedicine feasibility study. J Adolesc Young Adult Oncol. 2017;6:535–541. doi: 10.1089/jayao.2017.0013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Pagoto S, Waring ME, May CN, et al. Adapting behavioral interventions for social media delivery. J Med Internet Res. 2016;18:e24. doi: 10.2196/jmir.5086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Wu YP, Steele RG, Connelly MA, et al. Commentary: Pediatric eHealth interventions: Common challenges during development, implementation, and dissemination. J Pediatr Psychol. 2014;39:612–623. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsu022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Dallery J, Riley WT, Nahum-Shani I. Research designs to develop and evaluate technology-based health behavior interventions, in Marsch LA, Lord SE, Dallery J (eds): Behavioral Healthcare and Technology: Using Science-Based Innovations to Transform Practice (ed 12). New York, NY, Oxford University Press, 2015, pp. :168–186. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Moody L, Turner A, Osmond J, et al. Web-based self-management for young cancer survivors: Consideration of user requirements and barriers to implementation. J Cancer Surviv. 2015;9:188–200. doi: 10.1007/s11764-014-0400-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Perski O, Blandford A, West R, et al. Conceptualising engagement with digital behaviour change interventions: A systematic review using principles from critical interpretive synthesis. Transl Behav Med. 2017;7:254–267. doi: 10.1007/s13142-016-0453-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Schubart JR, Stuckey HL, Ganeshamoorthy A, et al. Chronic health conditions and Internet behavioral interventions: A review of factors to enhance user engagement. Comput Inform Nurs. 2011;29:81–92. doi: 10.1097/NCN.0b013e3182065eed. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Alkhaldi G, Hamilton FL, Lau R, et al. The effectiveness of prompts to promote engagement with digital interventions: A systematic review. J Med Internet Res. 2016;18:e6. doi: 10.2196/jmir.4790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Looyestyn J, Kernot J, Boshoff K, et al. Does gamification increase engagement with online programs? A systematic review. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0173403. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0173403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Reblin M, Wu YP, Pok J, et al. Development of the electronic social network assessment program using the Center for eHealth and Wellbeing Research Roadmap. JMIR Human Factors. 2017;4:e23. doi: 10.2196/humanfactors.7845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]