Abstract

Most natural product biosynthetic gene clusters identified in bacterial genomic and metagenomic sequencing efforts are silent under laboratory growth conditions. Here, we describe a scalable biosynthetic gene cluster activation method wherein the gene clusters are disassembled at interoperonic regions in vitro using CRISPR/Cas9 and then reassembled with PCR-amplified, short DNAs, carrying synthetic promoters, using transformation assisted recombination (TAR) in yeast. This simple, cost-effective, and scalable method allows for the simultaneous generation of combinatorial libraries of refactored gene clusters, eliminating the need to understand the transcriptional hierarchy of the silent genes. In two test cases, this in vitro disassembly-TAR reassembly method was used to create collections of promoter-replaced gene clusters that were tested in parallel to identify versions that enabled secondary metabolite production. Activation of the atolypene (ato) gene cluster led to the characterization of two unprecedented, bacterial cyclic sesterterpenes, atolypene A (1) and B (2), which are moderately cytotoxic to human cancer cell lines. This streamlined in vitro disassembly-in vivo reassembly method offers a simplified approach for silent gene cluster refactoring that should facilitate the discovery of natural products from silent gene clusters cloned from either metagenomes or cultured bacteria.

Keywords: Natural products, Promoter engineering, Metagenomics, Genome mining, Sesterterpene

Graphical Abstract

INTRODUCTION

Bacterial secondary metabolites have been one of the most prolific sources of lead structures used in the development of diverse therapeutic agents.1, 2 It is now well established that although conventional, fermentation-based natural product discovery approaches have been very productive, they have failed to access metabolites encoded by the vast majority of biosynthetic gene clusters that are present in the global microbiome.3–6 While systematic methods have been developed for identifying and cloning previously unstudied gene clusters found in sequenced bacterial genomes and metagenomes, a key limitation to exploiting this biosynthetic diversity is that majority of gene clusters identified in DNA-sequencing studies remain silent.7–11

A growing number of approaches are being explored to access molecules encoded by silent biosynthetic gene clusters.5, 12–18 Evidence suggests that transcriptional silencing is a key bottleneck in this process.19–21 An appealingly simple approach for alleviating this bottleneck is targeted induction of naturally coregulated biosynthetic operons across a cloned biosynthetic gene cluster using constitutively active promoters. We recently outlined a multiplexed promoter refactoring approach that relies on the use of CRISPR/Cas9 in yeast to cut the target gene cluster at native promoter regions and then transformation assisted recombination (TAR) in yeast to reassemble the gene cluster using DNAs carrying synthetic promoters (mCRISTAR, multiplexed CRISPR TAR).15 Pre-digestion of target sequences with CRISPR/Cas9 greatly increases the efficiency of TAR, allowing for the simultaneous refactoring of promoters controlling multiple operons in the same reaction. A large and diverse collection of CRISPR/Cas9-based methodologies has been developed for manipulating DNA.22–26 Only a small subset of these have so far been applied to the study of natural product biosynthetic gene clusters.15, 17, 27–29 Here, we describe an improved, multiplexed promoter exchange methodology for use in activating cloned biosynthetic gene clusters. In this method the gene cluster disassembly process is done by Cas9 in vitro, followed by TAR reassembly in yeast providing a higher throughput, more flexible, and more cost-effective means of refactoring natural product biosynthetic gene clusters (Figure 1). In vitro Cas9 digestion and TAR have been coupled in previous studies to provide an improved DNA cloning tool.9 We reasoned that the refactoring of natural product biosynthetic gene clusters would similarly benefit from the development of a multiplexed, in vitro Cas9-TAR-coupled method capable of the simultaneous exchange of multiple promoters across a targeted natural product biosynthetic gene cluster. For simplicity, we have called this multiplexed approach to refactoring natural product biosynthetic gene clusters, miCASTAR (multiplex in vitro Cas9-TAR). Compared to mCRISTAR, miCASTAR simplifies the refactoring process by eliminating the time-consuming requirement to construct and transform unique CRISPR/Cas9 plasmids into yeast for each refactoring experiment.

Figure 1.

Schematic procedure for miCASTAR method including gene cluster disassembly using in vitro Cas9 digestion and reassembly using yeast-mediated TAR to generate a library of differentially refactored gene clusters for use in heterologous expression experiments. The triangles indicate promoter insertion events. Different colored triangles are indicative of different promoter cassettes.

In a proof-of-concept study, we used this method to activate the well-characterized, naturally silent tetarimycin A (tam) biosynthetic gene cluster that we had previously cloned from a soil metagenome.15, 21 We then used miCASTAR to activate the previously uncharacterized atolypene (ato) biosynthetic gene cluster, which we cloned from the genome of the cultured actinomycete Amycolatopsis tolypomycina NRRL B-24205.30 Upon promoter refactoring with miCASTAR, the ato gene cluster was found to encode atolypenes A and B. The atolypenes are cytotoxic to human cancer cell lines and are predicted to arise from a sesterterpene precursor, very rarely seen in characterized bacterial secondary metabolites.31–34 miCASTAR provides a simple, cost-effective and easily parallelized approach for scaling the study of silent gene clusters and, consequently, the discovery of novel bioactive natural products.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Development of miCASTAR using the model tam gene cluster

We envisioned that the miCASTAR method would consist of two steps. The first step would involve the in vitro cleavage of a gene cluster at native promoter sites using small guide RNA (sgRNA)-directed Cas9 digestion. This would be followed by the gene cluster reassembly in vivo, using small DNA cassettes containing synthetic promoters with homology arms matching each Cas9 digestion site in a TAR reaction in yeast. The sgRNAs needed for this process can be easily generated from DNA oligos using in vitro transcription, while the short DNAs containing promoters and gene cluster-specific homology arms can be easily generated by PCR using existing promoter cassette libraries as templates.15 The optimization of this two-step process is described below, using a bacterial artificial chromosome (BAC) carrying the tetarimycin A biosynthetic gene cluster (pTARa:tam, Genbank accession No. JX843821). The tam gene cluster is a silent Type II polyketide biosynthetic gene cluster that was originally cloned from the soil metagenome.21

Optimization of the initial in vitro Cas9 gene cluster digestion step

Cas9 digestion efficiency is known to depend on the ratio of sgRNA(s) to target DNA as well as the time of digestion.29, 35 To determine the appropriate experimental conditions for miCASTAR we tested these two parameters by incubating a fixed amount of pTARa:tam with varying amounts of two sgRNAs for different periods of time.15, 21 The sgRNA:Cas9 molar ratio was fixed at 1:1 for all experiments. The efficiency of digestion was evaluated by agarose gel electrophoresis (Figure S1). The most efficient digestion was achieved using a molar ratio of 200 sgRNA to 1 cloned gene cluster and at least 16 hours of incubation at 37 °C. Accordingly, a molar ratio of 200:200:1 of sgRNA:Cas9:DNA and overnight incubation at 37 °C were used for all subsequent experiments.

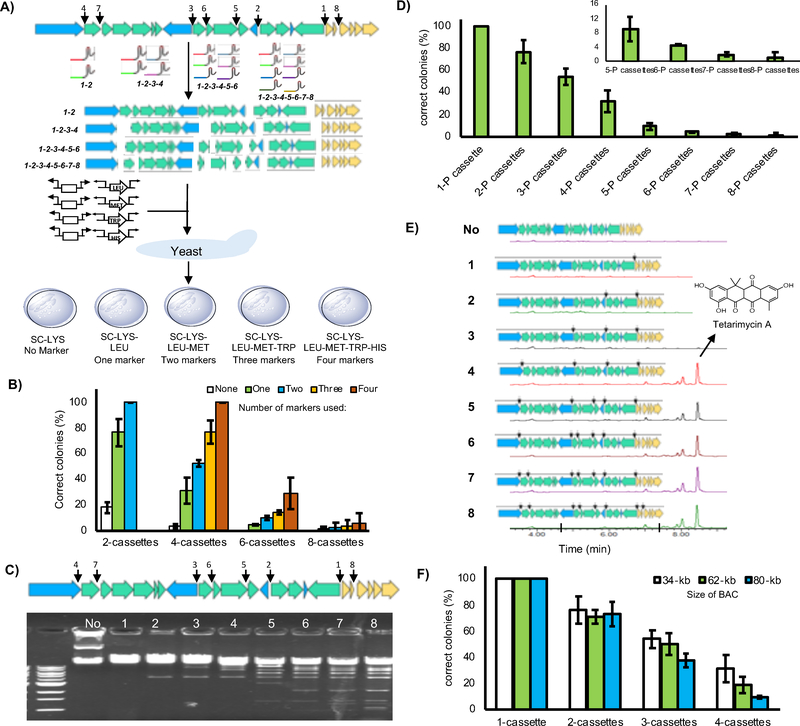

Gene cluster reassembly with marker-free promoter cassettes

Once a gene cluster is fragmented, miCASTAR relies on the reassembly of the gene cluster in yeast using PCR-generated, promoter-containing DNA fragments appended with homology arms matching each Cas9 digestion site. Although the selection for a correctly reassembled gene cluster could be achieved through the use of promoter cassettes carrying prototrophic markers and plating on appropriate dropout media, the limited number of commonly used prototrophic markers restricts the versatility of this approach. To overcome this limitation, we evaluated the efficiency of re-assembling a gene cluster both with and without auxotrophic selection. For this study, pTARa:tam was digested with Cas9 and 2, 4, 6, or 8 sgRNAs. The fragmented DNAs were then co-transformed into Saccharomyces cerevisiae with the corresponding number of promoter cassettes with or without the prototrophic markers. Transformants were plated on yeast synthetic dropout media missing lysine to select for the BAC vector as well as one, two, three or four additional amino acids to select for the introduced promoter cassettes (Figure 2A). To determine the efficiency of each reassembly condition, at least twenty yeast colonies from each dropout condition were PCR screened for the presence of all expected promoters. As expected, the percentage of yeast colonies harboring fully refactored constructs increased in concert with the number of auxotrophic selections used (Figure 2B). Our data indicate that four simultaneous refactoring events can be achieved with a 25% success rate using one promoter cassette containing a prototrophic marker and three marker-free promoter cassettes. Under these conditions, only a small number of yeast colonies must be screened after each refactoring experiment to identify a correctly refactored construct.

Figure 2.

miCASTAR development. A) Experimental design for assessing the efficiency of using different numbers of prototrophic markers to select for the simultaneous insertion of 2, 4, 6 or 8 promoter cassettes into the tam gene cluster. White boxes indicate marker free bi-directional promoter cassettes. Open arrows indicate bi-directional promoter cassettes with prototrophic markers. B) Efficiency of selecting of the multiplexed, TAR-based insertion of promoter cassettes using between zero and four auxotrophic selections. C) The tam gene cluster was digested at between 1 to 8 interoperonic regions (shown by arrows) using 8 different tam gene cluster specific sgRNAs and Cas9. Fragmented pTARa:tam was visualized by agarose gel electrophoresis. The numbers in the gel indicate the number of interoperonic regions that was targeted in each reaction. Specific cut site patterns are shown E. D) Efficiency of selecting for the correctly refactored construct when single marker miCASTAR was conducted on pTARa:tam using different numbers of promoter (P) cassettes. E) HPLC profiles of ethyl acetate extracts derived from cultures of S. albus transformed with native and refactored tam gene clusters. The production of tetarimycin A is seen upon introduction of four or more promoters. F) The efficiency of using single-marker miCASTAR to correctly engineer BACs of different sizes is shown. BACs used in this study contain either uncharacterized type I polyketide or nonribosomal biosynthetic gene clusters cloned from a soil metagenome.

Systematic refactoring of the tam gene cluster using single-marker miCASTAR

The tam gene cluster is naturally silent when cloned into the model heterologous expression host Streptomyces albus J1074.21, 36, 37 A variety of promoter exchange events have been shown to induce the tam gene cluster to produce tetarimycin A in the S. albus background.14, 15 In one instance, the introduction of eight promoter cassettes, including five uni- and three bi-directional cassettes, were shown to induce production of tetarimycin A.15 To further assess the versatility of single-marker miCASTAR sgRNAs targeting these eight sites were used to introduce promoter cassettes at between 1 and 8 sites in pTARa:tam (Figure 2C, Table S2). The tam gene cluster-specific promoter refactoring cassettes were generated by PCR using primers containing 40-bp of sequence homologous to either the upstream or downstream sequence at each cut site and an existing set of Streptomyces-based promoter exchange cassettes as template (Table S1).15

Each set of digested pTARa:tam fragments was co-transformed into yeast with the corresponding collection of the promoter cassettes required for gene cluster reassembly. Transformants were selected on lysine/leucine dropout medium, selecting for the BAC vector and the single prototrophic marker, respectively. Resulting colonies were screened by PCR for the presence of each expected refactoring cassette. Similar to the trend seen in our initial, method development experiments, the effectiveness of using a single marker for refactoring ranged from 100% correct constructs for a single promoter cassette insertion to approximately 5% correct products for the simultaneous insertion of eight cassettes (Figure 2D). Each refactored tam gene cluster was conjugated into S. albus and tested for the ability to confer production of tetarimycin A to the host. As expected from previous refactoring studies, S. albus transformed with tam constructs that, at a minimum, contained the four synthetic promoter cassettes that are expected to drive the expression of all biosynthetic operons, produced tetarimycin A (Figure 2E).15

The effect of BAC size on refactoring efficiency

We examined the effect of gene cluster size on the efficiency of single-marker miCASTAR by introducing up to four promoter cassettes into BACs of increasing size (34-, 62-, and 80-kb). These three BACs contain either uncharacterized type I polyketide biosynthetic or nonribosomal peptide gene clusters cloned from soil metagenomes. We did not observe a dramatic size-dependent change in miCASTAR efficiency when introducing between 1 and 3 cassettes and only a small decrease in efficiency was observed when introducing 4 cassettes into the largest construct (Figure 2F), suggesting that miCASTAR should be useful for refactoring even very large gene clusters.

Comparison of miCASTAR and mCRISTAR methods

Figure S2 shows a detailed stepwise comparison of the miCASTAR and mCRISTAR methods. We estimate that in vitro Cas9 gene cluster digestion with the miCASTAR method saves almost a week over the in vivo digest protocol used in mCRISTAR. The cost of reagents needed for refactoring a single gene cluster is comparable for both methods. However, a key advantage for the miCASTAR method is that a single set of refactoring reagents (i.e., DNA oligos for generating guide RNAs and primers for generating gene cluster specific promoter cassettes) can be used for generating a library of differentially refactored gene clusters. With mCRISTAR different gBlocks must be purchased and cloned for each unique refactoring experiment.

Application of miCASTAR to the discovery of novel natural products from the ato gene cluster

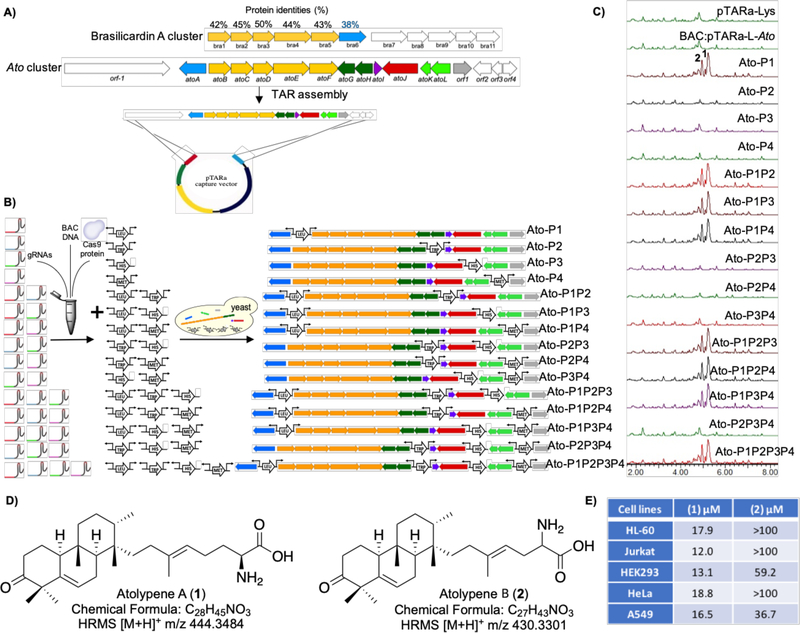

Terpenes make up the most structurally diverse class of natural products, with more than 80,000 compounds identified to date.38 Historically, the vast majority of terpenes have been found from plants and fungi, with a relatively minor fraction having been isolated from bacterial sources.39 Bioinformatic analysis of the rapidly growing number of sequenced bacterial (meta)genomes suggests that bacteria should also represent a fertile source of novel, biologically interesting terpenes.39–42 Gene clusters encoding Class II terpene cyclases are of particular interest to us because they are predicted to cyclize large isoprene precursors (>20 carbons) which have only rarely been reported in bacteria.38, 42, 43 We have initially focused our discovery efforts on a predicted Class II cyclase-containing gene cluster, found in the genome of A. tolypomycina, which we have called the ato gene cluster. Based on gene organization and gene content, the genomic region directly adjacent to the predicted atoE Class II terpene cyclase is closely related to the brasilicardin A (bra) gene cluster found in the genome of Nocardia brasiliensis IFM 0406 (also referred to as Nocardia terpenica). Brasilicardin A is a glycosylated tricyclic diterpene with potent immunosuppressive activity and a rare anti/syn/anti-perhydrophenanthrene skeleton.44–46 The genomic region around atoE contains all of the genes that are predicted to encode enzymes involved in the biosynthesis of brasilicardin A terpene skeleton (Figure 3A, S3).47 However, atoE shares only 44% sequence identity with the brasilicardin terpene cyclase (bra4) and only a maximum of 46% sequence identity with any predicted terpene cyclase found in Genbank, which suggested to us that the ato gene cluster might encode for a large terpene that was structurally distinct from brasilicardin A.

Figure 3.

Systematic refactoring the silent atolypene gene cluster using miCASTAR. A) Comparison between the brasilicardin A (bra) and ato gene clusters, and TAR assembly of the ato gene cluster. AtoG through atoL were ultimately determined not to be part the ato gene cluster. B) miCASTAR to generate 15 different combinations of promoter refactored constructs. C) Total positive ion chromatogram resulting from UPLC-MS analysis of extracts from S. albus hosting different refactored gene clusters, native gene cluster, and pTARa-Lys empty vector. D) Structures of atolypenes A and B isolated from strains hosting refactored ato gene clusters. This figure shows the relative stereochemistry throughout the tricyclic ring system, and the absolute configures of the amino acid. E) IC50 data for atolypenes A and B against human cell lines. IC50 values were also determined for melittin versus HEK293 (3.71 μM), HeLa (0.91 μM), and A549 (0.39 μM) as positive controls.

Cloning of the ato gene cluster using TAR

The exact boundaries of the gene cluster associated with atoE were not initially known. Based on the bra gene cluster and the nearby presence of genes predicted to be involved in primary metabolism we identified 7 operons as candidates for making up the ato gene cluster. The twelve genes in these operons were tentatively named atoA through atoL. This region of the genome was cloned directly from A. tolypomycina genomic DNA using TAR and an Escherichia coli:Yeast:Streptomyces shuttle capture vector (pTARa-Lys) (Figure 3A).8, 10 The cloned ato gene cluster (BAC:pTARa-L-ato) was then shuttled to S. albus for heterologous expression. Unfortunately, it did not confer the production of any detectable clone specific metabolites to the host under the conditions we examined.

Parallelized, combinatorial refactoring of the ato gene cluster using miCASTAR

We initially predicted that the ato gene cluster could be composed of up to seven operons that are controlled by four interoperonic regions (Figure S4A). Three of the interoperonic regions were predicted to contain bidirectional promoters, and one was predicted to contain a unidirectional promoter. As is typically the case, it was not immediately obvious which of these promoters would need to be replaced in order to induce production of the encoded metabolite. The two- step miCASTAR process is, by its nature, easily multiplexed, allowing for the rapid generation of differentially refactored gene clusters that can be tested empirically for their ability to confer metabolite production to a model host. In this case, we used four ato gene cluster-specific sgRNAs and four promoter cassettes to generate all 15 possible promoter exchange combinations in parallel (Figure 3B). A collection of previously described ermE*-based strong constitutive promoters were used in this study (Table S1).48 For refactoring the ato gene cluster promoters were selected at random for this collection. Based on the operon structure at each promoter site three bi-directional and one uni-directional promoter cassettes were used in the refactoring experiments. Initially, the four sgRNAs were used to digest BAC:pTARa-L-ato into 15 combinations of fragments. Fragmented BAC DNAs and an appropriate collection of PCR-amplified promoter cassettes were then co-transformed into yeast for gene cluster reassembly and plated on dropout plates containing amino acid combinations that corresponded to the prototrophic markers carried by the specific collection of promoter cassettes used in each reassembly experiment. Yeast colonies carrying appropriately refactored gene clusters were identified by PCR-based genotyping and confirmed with restriction mapping and sequencing (Figure S4B, S4C). All 15 promoter refactored constructs (Figure 3B, Ato-P1 through AtoP1P2P3P4) were successfully generated in parallel in one round of yeast transformations.

Analysis of metabolites produced by S. albus transformed with differentially refactored ato gene clusters

All 15 promoter-refactored constructs, as well as BAC:pTARa-L-ato and an empty pTARa-Lys, were conjugated into S. albus for heterologous expression studies. Ethyl acetate extracts from exconjugants grown in liquid culture were analyzed by ultra-performance liquid chromatography mass-spectrometry (UPLC-MS) for the presence of clone-specific metabolites. This analysis identified two major, clone-specific peaks (ESI-MS [M+H]+ m/z 444.3 for 1 and [M+H]+ m/z 430.3 for 2) from culture extracts of S. albus transformed with Ato-P1, Ato-P1P2, Ato-P1P3, Ato-P1P4, Ato-P1P2P3, Ato-P1P2P4, Ato-P1P3P4, and Ato-P1P2P3P4 (Figure 3C, S5). Neither peak was found in extracts from cultures of S. albus transformed with the pTARa-Lys empty vector control, BAC:pTARa-L-ato, or any other refactored constructs.

The metabolites associated with these peaks were given the trivial names atolypene A and B, respectively. The commonality among the refactored gene clusters that produced atolypenes A and B was the insertion of a promoter cassette at the P1 position in the gene cluster, indicating that a single promoter exchange event at his position is sufficient to activate the ato gene cluster. As seen when refactoring the tam gene cluster, metabolite production was not disrupted by additional promoter exchange events beyond the minimum required to activate the gene cluster.15 As there are still no general rules for how best to transcriptionally activate a silent biosynthetic gene cluster, we believe that the development of methods for the parallel, rapid, and cost-effective creation of collections of gene clusters where promoters can be systemically refactored throughout a gene cluster will prove the most useful for accessing natural products encoded by diverse silent biosynthetic gene clusters.

Atolypene isolation, structure elucidation, bioactivity and biosynthesis

Ethyl acetate extracts from 35 L of S. albus transformed with Ato-P1P2P3P4 were used to obtain sufficient quantities of atolypene A (8 mg) and B (4 mg) for structure elucidation and bioactivity studies. The structures of atolypenes A and B were determined using a combination of HRMS and NMR data (Table S3, Figure S6–S19). Atolypenes A and B contain tricyclic ring systems appended with isoprene-derived amino acid moieties of varying length (Figure 3D). The relative stereochemistry throughout the tricyclic ring system in atolypene A was determined using NOESY data (Figure S20) and the absolute configuration of the amino acid was determined by phenylglycine methyl ester (PGME) analysis (Figure S21).49

The biosynthesis of atolypene A can be rationalized based on the predicted functions of the enzymes encoded by atoA, B, C, D, E and F (Figure 4A). The two operons that contain these six genes are only found in the genome of A. tolypomycina NRRL B-24205, while operons containing other genes we originally hypothesized might be part of the ato gene cluster (Figure 3A) are found in many sequenced Amycolatopsis species (Figure S2). Based on our ability to rationalize the biosynthesis of atolypene A and the unique association of the operons containing atoA – F with A. tolypomycina NRRL B-24205, we believe that atolypene A is likely the metabolite encoded by the ato gene cluster, which we now define as atoA – F. The flexible mixand-match nature of miCASTAR allowed us to systematically explore the genomic region around atoE (sesterterpene cyclase) and ultimately define the ato gene cluster. The origin of the minor metabolite atolypene B is not bioinformatically obvious and will require additional biosynthetic studies; although, we speculate that it may arise from host oxidation and decarboxylation of the intermediate produced by atoD (prenyltransferase).

Figure 4.

Atolypene A biosynthesis and structure. A) Proposed atolypene A biosynthetic pathway with the table of proposed biosynthetic gene function. B) Geranyl-geranyl pyrophosphate origin brasilicardin A. C) Known tri- and tetra- cyclic sesterterpenes with methyl migration patterns similar to that seen in the atolypenes.

Although brasilicardin A and the atolypenes contain similar tricyclic ring systems, they differ by the methyl substitution patterns around the rings and by the length of the isoprene-derived amino acid moiety attached to the ring system. They also differ in their predicted isoprene precursor. In our proposed biosynthetic scheme, atolypene A arises from a C-25 sesterterpene precursor, while brasilicardin A is predicted to arise from a C-20 diterpene precursor, resulting in atolypene A amino acid moiety being five carbons longer than the one seen in brasilicardin A (Figure 4A, 4B). Interestingly, the generally rare sesterterpenes have most often been characterized from plants or fungi and only seldom seen in bacteria.31 The carbon skeletons seen in the atolypenes have not been reported previously, and the specific methylation pattern around their tricyclic core has only been reported previously in one sponge-derived sesterterpene (Figure 4C, aplysolide A).50 The structures of the atolypenes suggest that they represent rarely reported examples of bacteria producing cyclic sesterterpenes.31–34 Due to the infrequency with which large cyclic terpenes have been identified from bacteria, the systematic exploration of bacterial biosynthetic gene clusters that encode Class II terpene cyclases is likely to be a productive strategy for identifying structurally novel natural products.

In antimicrobial assays, neither atolypene A nor B inhibited the growth of the bacteria or yeast strains that were tested (Staphylococcus aureus USA300, Bacillus subtilis 168 1A1, E. coli DH5α, Candida albicans CAI4). Both atolypenes were, however, cytotoxic to diverse human cell lines (Figure 3E). In general, atolypene A was more potent than atolypene B in these assays (Figure 3E). Brasilicardin A was also reported to be inactive against microbial strains but cytotoxic against many mammalian cell lines.44, 45 Its biological activity is thought to arise from the inhibition of amino acid transport system L.51 As the atolypenes retain the amino acid side chain seen in brasilicardin A, we tested atolypene A for inhibition against the amino acid transport system L. At the highest concentration tested (125 μM) we did not observe any inhibition of [14C]L-leucine uptake, suggesting the mechanism of atolypene A cytotoxicity differs from that of brasilicardin A. A more detailed mechanistic analysis will be the focus of future studies.

CONCLUSION

miCASTAR offers a simplified, scalable protocol for systematic refactoring of silent biosynthetic gene clusters. By coupling in vitro Cas9 gene cluster disassembly with in vivo TAR-based DNA assembly, this refactoring method achieves facile, multiplexed construction of promoter-refactored biosynthetic gene clusters. This flexible, mix-and-match, two-step method makes it possible to use a single set of reagents (i.e., sgRNAs and promoter cassettes) to construct and screen collections of gene clusters with different promoter combinations, diminishing the need to understand the transcription hierarchy of a gene cluster that is being refactored. In contrast to gene cluster refactoring strategies that rely on the de novo synthesis and DNA assembly, miCASTAR starts with cloned gene clusters and uses minimal synthetic manipulations in the refactoring process, reducing the cost and labor needed to survey the transcriptional landscape of, even very large, biosynthetic gene clusters.

Our understanding of the transcriptional regulation hierarchy is insufficient to precisely predict the exact promoter refactoring events required for inducing secondary metabolite production from most silent biosynthetic gene clusters. The rapid and flexible nature of miCASTAR allowed us to systematically create collections of promoter-refactored gene clusters that could be empirically tested, in parallel, to identify constructs that would induce secondary metabolite production. Using miCASTAR to generate all 15 possible promoter-reengineered constructs we successfully activated the ato gene cluster and, in doing so, discovered two unprecedented bioactive sesterterpenes. To the best of our knowledge, the atolypenes are the first structurally complex (i.e., plant/fungal-like) polycyclic sesterterpenes to be isolated from a bacterium.31–34 The large-scale application of miCASTAR should help simplify the discovery of novel bioactive natural products from the growing number of silent biosynthetic gene clusters identified in cloned metagenomes and sequenced bacteria.

Materials and methods

In vitro sgRNA transcription and purification

The CHOPCHOP web tool was used to identify PAM sequences in interoperonic regions.52 54- or 55-nucleotides (nt) target-specific oligonucleotides were designed to contain 20- or 21-nt of T7 RNA polymerase promoter sequence (TTCTAATACGACTCACTATAg) followed by the desired 20-nt target sequence, and a 14-nt crRNA overlap sequence (GTTTTAGAGCTAGA). All oligonucleotides used in this study were obtained from Integrated DNA Technologies. The oligonucleotides (Tam-gR and Ato-gR sequences in Table S2) were converted to 100- or 101-nt sgRNAs using the “EnGen sgRNA Synthesis Kit, S. pyogenes” kit (NEB). sgRNAs were purified from the enzymatic mixture using RNA Clean & Concentrator (Zymo Research) and then re-suspended in nuclease-free water. RNA concentration was determined by measuring absorbance at 260 nm using a NanoDrop instrument (ThermoFisher Scientific).

In vitro BAC DNA digestion with Cas9

Synthesized sgRNA(s) and Cas9 Nuclease (S. pyogenes, NEB) were mixed in a ~1:1 molar ratio in Cas9 Nuclease Reaction Buffer and incubated at 37 °C for 15 minutes. BAC DNA was then added (~100 fmol) to give a final sgRNA:DNA molar ratio of 200:1 and the reaction incubated at 37 °C overnight. The reaction was terminated by heating at 65 °C for 10 minutes. DNA was recovered from the fragmentation reaction using a Zymoclean™ Large Fragment DNA Recovery Kit (Zymo Research) and reconstituted in 10 mM Tris-HCl buffer (pH 8.5).

PCR amplification of cluster-specific promoter cassettes and in-yeast assembly

All synthetic constitutively active promoters used in this study (P15, P16, P14, P13, P19, P12, P21, P23, P17, P18, P06, P10, P04, and P05) have been described previously.15 pRS constructs carrying prototrophic markers and primers with synthetic promoter sequences were used to generate promoter cassettes that were TOPO cloned into pCR2.1 (Invitrogen) to yield SNP11-LEU2-topo, SNP12-TRP1-topo, SNP13-MET15-topo and SNP14-HIS3-topo (Table S1, S2). These four plasmids containing promoters flanking prototrophic marker served as template DNAs for amplification of promoter cassettes used in the refactoring of the ato gene cluster, as well as refactoring experiments with the tam gene cluster that were used to assess the efficiency of gene cluster reassembly. (Table S1). The promoter cassette inserted into region 3 of the tam gene cluster result in ~800-bp truncation of tamI (SARP transcriptional activator gene) to avoid its effect on the activation of the tam gene cluster. In addition, four marker-free promoter cassettes with 1kb random DNA between two promoters were TOPO cloned into pCR2.1 for generating SNP12–1kb-topo, SNP13–1kb-topo, SNP14–1kb-topo and SNP15–1kb-topo plasmids (Table S1). SNP11-LEU2-topo plasmid and seven marker-free promoter templates (SNP12–1kb-topo, SNP13–1kb-topo, SNP14–1kbtopo, SNP15–1kb-topo, SNP16-topo, SNP17-topo and pIJ10257 plasmids) were used for single-marker refactoring of the tam gene cluster (Table S1). Promoter cassettes both with and without prototrophic markers were PCR-amplified using Tam-PE or Ato-PE primer sets (Table S2), which contain 40bp homology derived from the tam or ato gene cluster, respectively. PCR-amplified cassettes and Cas9-digested DNA fragments were transformed into S. cerevisiae BY4727 Δdnl4 using a LiAc/ss carrier DNA/PEG yeast transformation protocol.14, 53 Strains and vectors used in this study appear in Table S1. Selection was performed on SC amino acid dropout media (Sunrise Science Products). Yeast colonies with the correct insertion of promoter cassettes were identified with PCR-based genotyping (see Table S2 for screening primers). PCR positive DNA constructs were isolated from overnight yeast culture and then electroporated into E. coli EPI300 (Lucigen). Modified gene clusters were verified by restriction mapping or by Ion Torrent™ PGM sequencing.

Metabolite analysis of S. albus transformed with refactored tam gene clusters

A BAC carrying either a refactored or native tam gene cluster was electroporated into E. coli S17–1 and then integrated into the S. albus genome via intergenic conjugation.54 S. albus strains harboring native and refactored tam gene clusters were grown at 30 °C for 5 days on ISP4 agar [soluble starch (10 g/L), K2HPO4 (1 g/L), MgSO4 (1 g/L), NaCl (1 g/L), (NH4)2SO4 (2 g/L), CaCO3 (2 g/L), FeSO4 (1 mg/L), MnCl2 (1 mg/L), ZnSO4 (1 mg/L) and agar (20 g/L), pH 7.2] supplemented with 50 μg/mL apramycin and 25 μg/mL nalidixic acid. Single colonies were used to inoculate Tryptone Soya Broth (TSB) [glucose (2.5 g/L), tryptone (17 g/L), soytone (3 g/L), NaCl (5 g/L), and K2HPO4 (2.5 g/L), pH 7.3] seed cultures which were grown for 2 days (30 °C, 200 rpm). Molecule production studies were carried out in 125 mL baffled flasks containing 50 mL of R5a medium [sucrose (100 g/L), K2SO4 (0.25 g/L), MgCl2 (10.12 g/L), glucose (10 g/L), casamino acids (0.1 g/L), yeast extract (5 g/L), MOPS (21 g/L), and trace elements: ZnCl2 (80 μg/L), FeCl3.6H2O (400 μg/L), CuCl2.2H2O (20 μg/L), MnCl2.4H2O (20 μg/L), Na2B4O7.10H2O (20 μg/L), (NH4)6Mo7O24.4H2O (20 μg/L), pH 6.85]. Cultures were shaken (200 rpm) for 7 days at 30 °C and then extracted with an equal volume of ethyl acetate. The presence of tetarimycin A in extracts was confirmed by reversed phase HPLC-MS analysis (C18 Waters Xbridge 5 μM, 4.6 × 150 mm, flow rate 1 mL/min) using a 5% to 95% gradient of acetonitrile/water with 0.1% formic acid over 15 min.

TAR cloning of the atolypene gene cluster

~21 kb of DNA predicted to contain the ato gene cluster (Genbank accession No. NZ_FNSO01000004, region: 5921897 to 5943258) was directly cloned from A. tolypomycina genomic DNA into the pTARa-Lys vector using TAR in yeast. A pathway-specific atoTAR capture vector was constructed using pTARa-Lys as described previously (see primers in Table S2).15 The primers Ato-UPS_FW and Ato-DWS_RV each contain 15-bp sequences that are identical to the ends of SphI-linearized pTARaLys. The primer Ato-DWS_FW was designed to contain a PmeI restriction site to facilitate the linearization of the pathway-specific capture vector. The upstream and downstream homologous arms were PCR-amplified using A. tolypomycina genomic DNA as template. The resulting 600-bp and 440-bp PCR products were combined by a second round of PCR. The final ~1 kb PCR product was cloned into SphI-linearized pTARa-Lys capture vector using a standard InFusion cloning reaction (Clontech) to create an ato gene cluster-specific capture vector. For TAR assembly, PmeI-linearized pathway-specific capture vector (200 ng) was co-transformed with briefly sheared A. tolypomycina genomic DNA (1 μg) into S. cerevisiae BY4727 Δdnl4, and transformants were plated on SC lysine dropout plates.8 The resulting transformants were screened by colony PCR using Ato-scrF/scrR specific primers to identify colonies with BACs containing the ato gene cluster (BAC:pTARa-L-ato). BACs from PCR positive colonies were PGM-sequenced to verify the correct cloning of the ato gene cluster.

Metabolite analysis of S. albus transformed with refactored atolypene gene clusters

S. albus transformants containing the empty pTARa-Lys vector, the native ato gene cluster or a refactored ato gene cluster were grown on ISP4 agar for 5 days and inoculated into the TSB seed cultures for 2 days. Production cultures were prepared using SMM [casamino acids (2 g/L), TES (5.73 g/L), glucose (9 g/L), NaH2PO4 (0.12 g/L), K2HPO4 (0.17 g/L), and trace elements: ZnCl2 (40 μg/L), FeCl3.6H2O (20 μg/L), MnCl2.4H2O (10 μg/L), (NH4)6Mo7O24.4H2O (10 μg/L), pH 7.0]. Cultures were grown in baffled flasks and shaken (200 rpm) for 7 days at 30 °C. Mature cultures were extracted with ethyl acetate and extracts were analyzed by UPLC-MS [Waters ACQUITY, C18 column (ACQUITY UPLC™ BEH 1,7 μM, 2.1 × 50 mm, flow rate 0.6 mL/min) 10% to 100% acetonitrile/water with 0.1% formic acid gradient over 8.1 minutes].

Isolation of atolypene A and B

The ethyl acetate extract from 35 L of S. albus:Ato-P1P2P3P4 grown in SMM was absorbed on 4 g of C18 resin, loaded onto a C18 column (Teledyne Isco, RediSep RF Gold 50 g) and fractionated using a stepwise gradient of 20%, 40%, 60%, 80% and 100% methanol in water (60 mL each). The atolypenes mainly eluted in the 80% methanol/water fraction. Atolypene A was isolated by isocratic HPLC using 48% acetonitrile/water with 0.1% formic acid (C18 Waters Xbridge 5 μM, 10 × 150 mm, flow rate 4 mL/min). Atolypene B was isolated by isocratic HPLC using 43% acetonitrile/water with 0.1% formic acid.

PGME derivatization of atolypene A

2 mg of dry atolypene A was dissolved in 2 mL of tetrahydrofuran (THF) and divided equally into two separate vials. Vials were treated with either 4 mg of S-PGME or R-PGME, and 5 mg of EDC (ethyl-(N,N-dimethylamino)- propylcarbodiimide hydrochloride). The reaction mixtures were stirred at room temperature for 4 hours. The resulting S- or R-PGME amide was detected by UPLC: [M+H]+ 591 m/z. S- or R-PGME amides of atolypene A was purified by reversed-phase HPLC (C18 Waters Xbridge 5 μM, 10 × 150 mm, flow rate 4 mL/min, gradient 30%−60% acetonitrile/water with 0.1% formic acid over 30 minutes).

Antimicrobial assays of atolypene A and B

Minimum inhibitory concentrations of atolypene A and B against a panel of microorganisms were determined using serial dilution in 96-well microtiter plates. S. aureus USA300, E. coli DH5a and B. subtilis 168 1A1 were cultured in Lysogeny broth whereas C. albicans CAI4 was cultured in YPD medium [glucose (20 g/L), yeast extract (10 g/L), and peptone (20 g/L), pH 6.5]. Overnight cultures were diluted 5,000-fold for each assay. MIC values were determined by visual inspection after 18 hours incubation at 37 °C for bacteria and 30 °C for yeast.

Cytotoxicity assessment for atolypene A and atolypene B

Cytotoxicity of atolypene A and B was determined using serial dilution in 96-well microtiter plates and 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl) diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT). HEK293, A549, and HeLa cells were cultured in DMEM medium. HL-60 and Jurkat cells were cultured in RPMI medium. All cells were grown at 37 °C with 5% CO2. Cells were harvested using trypsin prior to seeding at 104 cells/well in sterile tissue culture-treated polystyrene 96-well plates (180 μL of medium per well). After twenty-four hours plates were exposed to atolypene A and B and after 48 hours of exposure cell viability was assessed using MTT (570 nm).

Measurement of [14C] L-leucine uptake

As described previously, an amino acid uptake assay was performed using [14C]L-leucine.55 HeLa cells were seeded into DMEM medium in 24-well plates (105 cells/well) and grown to 85–95% confluent. The cells were washed three times with uptake solution (125 mM NaCl, 4.8 mM KCl, 1.3 mM CaCl2, 1.2 mM MgSO4, 25 mM HEPES, 1.2 mM KH2PO4, 5.6 mM glucose, pH 7.4), and then preincubated with different concentrations of atolypene A or 2-aminobicyclo-(2,2,1)-heptane-2-carboxylic acid (BCH, served as positive control) for 10 minutes at 37 °C. The medium was then replaced with fresh uptake solution containing 1 μM [14C] L-leucine. After a 1 minute incubation, the [14C] L-leucine uptake solution was removed and the uptake reaction terminated by washing the cells in three times with ice-cold uptake solution. Cells were solubilized with 0.1 N NaOH and the radioactivity of taken up [14C] L-leucine was measured using a liquid scintillation counter.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grants U01 GM110714 and 1R35 GM122559.

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supporting Information

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website. Additional experimental details, NMR data, supplemental tables and figures.

REFERENCES

- 1.Newman DJ; Cragg GM, Natural Products as Sources of New Drugs from 1981 to 2014. J Nat Prod 2016, 79 (3), 629–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Katz L; Baltz RH, Natural product discovery: past, present, and future. J Ind Microbiol Biotechnol 2016, 43 (2–3), 155–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bentley SD; Chater KF; Cerdeño-Tárraga AM; Challis GL; Thomson NR; James KD; Harris DE; Quail MA; Kieser H; Harper D; Bateman A; Brown S; Chandra G; Chen CW; Collins M; Cronin A; Fraser A; Goble A; Hidalgo J; Hornsby T; Howarth S; Huang CH; Kieser T; Larke L; Murphy L; Oliver K; O’Neil S; Rabbinowitsch E; Rajandream MA; Rutherford K; Rutter S; Seeger K; Saunders D; Sharp S; Squares R; Squares S; Taylor K; Warren T; Wietzorrek A; Woodward J; Barrell BG; Parkhill J; Hopwood DA, Complete genome sequence of the model actinomycete Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2). Nature 2002, 417 (6885), 141–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Keller NP; Turner G; Bennett JW, Fungal secondary metabolism - from biochemistry to genomics. Nat Rev Microbiol 2005, 3 (12), 937–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rutledge PJ; Challis GL, Discovery of microbial natural products by activation of silent biosynthetic gene clusters. Nat Rev Microbiol 2015, 13 (8), 509–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Niu G, Genomics-Driven Natural Product Discovery in Actinomycetes. Trends Biotechnol 2018, 36 (3), 238–241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kim JH; Feng Z; Bauer JD; Kallifidas D; Calle PY; Brady SF, Cloning large natural product gene clusters from the environment: piecing environmental DNA gene clusters back together with TAR. Biopolymers 2010, 93 (9), 833–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kallifidas D; Brady SF, Reassembly of functionally intact environmental DNA-derived biosynthetic gene clusters. Methods Enzymol 2012, 517, 225–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lee NC; Larionov V; Kouprina N, Highly efficient CRISPR/Cas9-mediated TAR cloning of genes and chromosomal loci from complex genomes in yeast. Nucleic Acids Res 2015, 43 (8), e55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kouprina N; Larionov V, Transformation-associated recombination (TAR) cloning for genomics studies and synthetic biology. Chromosoma 2016, 125 (4), 621–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jensen PR; Chavarria KL; Fenical W; Moore BS; Ziemert N, Challenges and triumphs to genomics-based natural product discovery. J Ind Microbiol Biotechnol 2014, 41 (2), 203–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shao Z; Rao G; Li C; Abil Z; Luo Y; Zhao H, Refactoring the silent spectinabilin gene cluster using a plug-and-play scaffold. ACS Synth Biol 2013, 2 (11), 662–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Luo Y; Huang H; Liang J; Wang M; Lu L; Shao Z; Cobb RE; Zhao H, Activation and characterization of a cryptic polycyclic tetramate macrolactam biosynthetic gene cluster. Nat Commun 2013, 4, 2894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Montiel D; Kang HS; Chang FY; Charlop-Powers Z; Brady SF, Yeast homologous recombination-based promoter engineering for the activation of silent natural product biosynthetic gene clusters. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2015, 112 (29), 8953–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kang HS; Charlop-Powers Z; Brady SF, Multiplexed CRISPR/Cas9- and TAR-Mediated Promoter Engineering of Natural Product Biosynthetic Gene Clusters in Yeast. ACS Synth Biol 2016, 5 (9), 1002–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Basitta P; Westrich L; Rösch M; Kulik A; Gust B; Apel AK, AGOS: A Plug-and-Play Method for the Assembly of Artificial Gene Operons into Functional Biosynthetic Gene Clusters. ACS Synth Biol 2017, 6 (5), 817–825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhang MM; Wong FT; Wang Y; Luo S; Lim YH; Heng E; Yeo WL; Cobb RE; Enghiad B; Ang EL; Zhao H, CRISPR-Cas9 strategy for activation of silent Streptomyces biosynthetic gene clusters. Nat Chem Biol 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang X; Zhou H; Chen H; Jing X; Zheng W; Li R; Sun T; Liu J; Fu J; Huo L; Li YZ; Shen Y; Ding X; Müller R; Bian X; Zhang Y, Discovery of recombinases enables genome mining of cryptic biosynthetic gene clusters in Burkholderiales species. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Olano C; García I; González A; Rodriguez M; Rozas D; Rubio J; Sánchez-Hidalgo M; Braña AF; Méndez C; Salas JA, Activation and identification of five clusters for secondary metabolites in Streptomyces albus J1074. Microb Biotechnol 2014, 7 (3), 242–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jiang L; Wang L; Zhang J; Liu H; Hong B; Tan H; Niu G, Identification of novel mureidomycin analogues via rational activation of a cryptic gene cluster in Streptomyces roseosporus NRRL 15998. Sci Rep 2015, 5, 14111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kallifidas D; Kang HS; Brady SF, Tetarimycin A, an MRSA-active antibiotic identified through induced expression of environmental DNA gene clusters. J Am Chem Soc 2012, 134 (48), 19552–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Makarova KS; Haft DH; Barrangou R; Brouns SJJ; Charpentier E; Horvath P; Moineau S; Mojica FJM; Wolf YI; Yakunin AF; van der Oost J; Koonin EV, Evolution and classification of the CRISPR–Cas systems. Nature Reviews Microbiology 2011, 9, 467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hsu Patrick D.; Lander Eric S.; Zhang F, Development and Applications of CRISPR-Cas9 for Genome Engineering. Cell 2014, 157 (6), 1262–1278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang H; Russa ML; Qi LS, CRISPR/Cas9 in Genome Editing and Beyond. Annual Review of Biochemistry 2016, 85 (1), 227264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mali P; Yang L; Esvelt KM; Aach J; Guell M; DiCarlo JE; Norville JE; Church GM, RNA-Guided Human Genome Engineering via Cas9. Science 2013, 339 (6121), 823–826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Doudna JA; Charpentier E, The new frontier of genome engineering with CRISPR-Cas9. Science 2014, 346 (6213). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tong Y; Charusanti P; Zhang L; Weber T; Lee SY, CRISPR-Cas9 Based Engineering of Actinomycetal Genomes. ACS Synthetic Biology 2015, 4 (9), 1020–1029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cobb RE; Wang Y; Zhao H, High-Efficiency Multiplex Genome Editing of Streptomyces Species Using an Engineered CRISPR/Cas System. ACS Synthetic Biology 2015, 4 (6), 723–728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Liu Y; Tao W; Wen S; Li Z; Yang A; Deng Z; Sun Y, In Vitro CRISPR/Cas9 System for Efficient Targeted DNA Editing. MBio 2015, 6 (6), e01714–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wink JM; Kroppenstedt RM; Ganguli BN; Nadkarni SR; Schumann P; Seibert G; Stackebrandt E, Three new antibiotic producing species of the genus Amycolatopsis, Amycolatopsis balhimycina sp. nov., A. tolypomycina sp. nov., A. vancoresmycina sp. nov., and description of Amycolatopsis keratiniphila subsp. keratiniphila subsp. nov. and A. keratiniphila subsp. nogabecina subsp. nov. Syst Appl Microbiol 2003, 26 (1), 38–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wang L; Yang B; Lin XP; Zhou XF; Liu Y, Sesterterpenoids. Nat Prod Rep 2013, 30 (3), 455–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sato T; Yamaga H; Kashima S; Murata Y; Shinada T; Nakano C; Hoshino T, Identification of novel sesterterpene/triterpene synthase from Bacillus clausii. Chembiochem 2013, 14 (7), 822–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jan R; Lukas L; S., D. J., Spata-13,17-diene Synthase—An Enzyme with Sesqui-, Di-, and Sesterterpene Synthase Activity from Streptomyces xinghaiensis. Angewandte Chemie International Edition 2017, 56 (51), 16385–16389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yang Y; Zhang Y; Zhang S; Chen Q; Ma K; Bao L; Tao Y; Yin W; Wang G; Liu H, Identification and Characterization of a Membrane-Bound Sesterterpene Cyclase from Streptomyces somaliensis. J Nat Prod 2018, 81 (4), 1089–1092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Anders C; Jinek M, In vitro enzymology of Cas9. Methods Enzymol 2014, 546, 1–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chater KF; Wilde LC, Restriction of a bacteriophage of Streptomyces albus G involving endonuclease SalI. J Bacteriol 1976, 128 (2), 644–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zaburannyi N; Rabyk M; Ostash B; Fedorenko V; Luzhetskyy A, Insights into naturally minimised Streptomyces albus J1074 genome. BMC Genomics 2014, 15, 97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Christianson DW, Structural and Chemical Biology of Terpenoid Cyclases. Chem Rev 2017, 117 (17), 11570–11648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yamada Y; Cane DE; Ikeda H, Diversity and analysis of bacterial terpene synthases. Methods Enzymol 2012, 515, 123–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yamada Y; Kuzuyama T; Komatsu M; Shin-Ya K; Omura S; Cane DE; Ikeda H, Terpene synthases are widely distributed in bacteria. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2015, 112 (3), 857–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cane DE; Ikeda H, Exploration and mining of the bacterial terpenome. Acc Chem Res 2012, 45 (3), 463–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dong LB; Rudolf JD; Deng MR; Yan X; Shen B, Discovery of the Tiancilactone Antibiotics by Genome Mining of Atypical Bacterial Type II Diterpene Synthases. Chembiochem 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dickschat JS, Bacterial terpene cyclases. Nat Prod Rep 2016, 33 (1), 87–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Shigemori H; Komaki H; Yazawa K; Mikami Y; Nemoto A; Tanaka Y; Sasaki T; In Y; Ishida T; Kobayashi J, Brasilicardin A A Novel Tricyclic Metabolite with Potent Immunosuppressive Activity from Actinomycete Nocardiabrasiliensis. J Org Chem 1998, 63 (20), 6900–6904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Komaki H; Nemoto A; Tanaka Y; Takagi H; Yazawa K; Mikami Y; Shigemori H; Kobayashi J; Ando A; Nagata Y, Brasilicardin A, a new terpenoid antibiotic from pathogenic Nocardia brasiliensis: fermentation, isolation and biological activity. J Antibiot (Tokyo) 1999, 52 (1), 13–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Schwarz PN; Buchmann A; Roller L; Kulik A; Gross H; Wohlleben W; Stegmann E, The Immunosuppressant Brasilicardin: Determination of the Biosynthetic Gene Cluster in the Heterologous Host Amycolatopsis japonicum. Biotechnol J 2018, 13 (2). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hayashi Y; Matsuura N; Toshima H; Itoh N; Ishikawa J; Mikami Y; Dairi T, Cloning of the gene cluster responsible for the biosynthesis of brasilicardin A, a unique diterpenoid. J Antibiot (Tokyo) 2008, 61 (3), 164–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hong HJ; Hutchings MI; Hill LM; Buttner MJ, The role of the novel Fem protein VanK in vancomycin resistance in Streptomyces coelicolor. J Biol Chem 2005, 280 (13), 13055–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yabuuchi T; Kusumi T, Phenylglycine Methyl Ester, a Useful Tool for Absolute Configuration Determination of Various Chiral Carboxylic Acids. J. Org. Chem 2000, 65, 397–404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Crews P; Jiménez C; O’Neil-Johnson M, Using spectroscopic and database strategies to unravel structures of polycyclic bioactive marine sponge sesterterpenes. Tetrahedron 1991, 47 (22), 35853600. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Usui T; Nagumo Y; Watanabe A; Kubota T; Komatsu K; Kobayashi J; Osada H, Brasilicardin A, a natural immunosuppressant, targets amino Acid transport system L. Chem Biol 2006, 13 (11), 1153–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Montague TG; Cruz JM; Gagnon JA; Church GM; Valen E, CHOPCHOP: a CRISPR/Cas9 and TALEN web tool for genome editing. Nucleic Acids Res 2014, 42 (Web Server issue), W401–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gietz RD; Schiestl RH, High-efficiency yeast transformation using the LiAc/SS carrier DNA/PEG method. Nat Protoc 2007, 2 (1), 31–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kieser T; Bibb MJ; Buttner MJ; Chater KF; Hopwood DA, Practical Streptomyces Genetics. The John Innes Foundation: Norwich, England, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kim DK; Kanai Y; Choi HW; Tangtrongsup S; Chairoungdua A; Babu E; Tachampa K; Anzai N; Iribe Y; Endou H, Characterization of the system L amino acid transporter in T24 human bladder carcinoma cells. Biochim Biophys Acta 2002, 1565 (1), 112–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.