Abstract

Background

Anemia rates are over 60% in disadvantaged children yet there is little information about the quality of anemia care for disadvantaged children.

Methods

Our primary objective was to assess the burden and quality of anemia care for disadvantaged children and to determine how this varied by age and geographic location. We implemented a cross-sectional study using clinical audit data from 2287 Indigenous children aged 6–59 months attending 109 primary health care centers between 2012 and 2014. Data were analysed using multivariable regression models.

Results

Children aged 6–11 months (164, 41.9%) were less likely to receive anemia care than children aged 12–59 months (963, 56.5%) (adjusted odds ratio [aOR] 0.48, CI 0.35, 0.65). Proportion of children receiving anemia care ranged from 10.2% (92) (advice about ‘food security’) to 72.8% (728) (nutrition advice). 70.2% of children had a hemoglobin measurement in the last 12 months. Non-remote area families (115, 38.2) were less likely to receive anemia care compared to remote families (1012, 56.4%) (aOR 0.34, CI 0.15, 0.74). 57% (111) aged 6–11 months were diagnosed with anemia compared to 42.8% (163) aged 12–23 months and 22.4% (201) aged 24–59 months. 49% (48.5%, 219) of children with anemia received follow up.

Conclusions

The burden of anemia and quality of care for disadvantaged Indigenous children was concerning across all remote and urban locations assessed in this study. Improved services are needed for children aged 6–11 months, who are particularly at risk.

Keywords: Child, Anemia, Primary care

Background

Anemia is a major public health issue globally with an estimated prevalence of 47% in children aged under 5 years. [1] Prevalence is reported to be 70% in children living in low income countries and over 30% in disadvantaged Indigenous children aged under 5 years worldwide. [2, 3] Children are born with high hemoglobin concentrations but levels drop after 6 months of age due to depletion of iron stores with the most vulnerable period between 6 and 11 months. [4–7] Iron deficiency is the most important cause of anemia. [8] However, the cycle of poverty, poor environmental conditions, chronic infection, malabsorption and anorexia affecting disadvantaged children and families is also well recognised. [9, 10] Iron deficiency and other forms of anemia are associated with long term deficits in cognitive development and poor educational outcomes, especially in the youngest infants. [11, 12]

Reducing anemia rates requires complex and long-standing changes to nutritional intake, education levels, economic status and the social determinants of health. [9, 10] However, primary health care services have an important role in prevention, early detection and treatment. In Australia, the national government advises primary care providers to administer a ‘child health check’ annually to each Indigenous child across the country. [13] These ‘checks’ are standardised, based on best practice guidelines and include measurements for growth and screening for hemoglobin at least once per year for high risk groups, as well as breastfeeding promotion, dietary and complementary feeding advice, discussion of housing and food security and recommendations about social support services. [13]

Yet, there is little information about how well anemia services are being implemented in busy primary care settings, especially those in remote areas, which service highly disadvantaged communities. Also, despite the high burden, to our knowledge only one study has assessed anemia burden and the quality of anemia care provided to infants aged 6–11 months. [14]

The Audit for Best Practice in Chronic Disease (ABCD) continuous quality improvement (CQI) program was developed for Australian Indigenous primary health care centers for the prevention and management of chronic disease. [15–17] The ABCD program aims to improve service delivery using plan-do-study-act (PDSA) cycles (including analysing current practice, implementing change and then encouraging service providers to assess the impact of the change). [15]

Our primary objective was to assess the quality of anemia care provided to disadvantaged children attending the ABCD primary care centers and to determine how this varied by age. Secondary objectives were to assess the effect of geographic location and to describe the burden of anemia (hemoglobin < 110 g/dl) in children aged 6–59 months.

Methods

Study setting

This was a cross sectional study using audit data from children aged 6–59 months from 109 Indigenous primary health care centers in remote, rural and urban areas across Australia between 2012 and 2014. Details of these methods are published elsewhere. [18, 19] The characteristics of the primary care clinics and health care providers are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Key characteristics by age and geographic location in Indigenous children aged 6–59 months

| Total | Age (months) | Geographic location | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6–11 | 12–23 | 24–59 | Remote | Rural | Urban | ||

| Total | 2287 | 430 (18.8%) | 532 (23.3%) | 1325 (57.9%) | 1861 (81.4%) | 346 (15.1%) | 80 (3.5%) |

| Health Service Characteristics | |||||||

| Governance | |||||||

| Aboriginal community controlled health service | 528 (23.1%) | 88 (20.5%) | 118 (22.2%) | 322 (24.3%) | 293 (15.7%) | 208 (60.1%) | 27 (33.8%) |

| Government health service | 1759 (76.9%) | 342 (79.5%) | 414 (77.8%) | 1003 (75.7%) | 1568 (84.3%) | 138 (39.9%) | 53 (66.3%) |

| Health service provider who first saw the child | |||||||

| Indigenous health worker | 318 (13.9%) | 49 (11.4%) | 67 (12.6%) | 202 (15.2%) | 205 (11%) | 91 (26.3%) | 22 (27.5%) |

| Nurse | 1584 (69.3%) | 321 (74.7%) | 381 (71.6%) | 882 (66.6%) | 1385 (74.4%) | 159 (46%) | 40 (50%) |

| GP | 259 (11.3%) | 50 (11.6%) | 60 (11.3%) | 149 (11.3%) | 157 (8.4%) | 85 (24.6%) | 17 (21.3%) |

| Other | 109 (4.8%) | 8 (1.9%) | 20 (3.8%) | 81 (6.1%) | 98 (5.3%) | 10 (2.9%) | 1 (1.3%) |

| Missing | 17 (0.7%) | 2 (0.5%) | 4 (0.8%) | 11 (0.8%) | 16 (0.9%) | 1 (0.3%) | 0 (0%) |

| Year of data collection | |||||||

| 2012 | 448 (19.6%) | 87 (20.2%) | 107 (20.1%) | 254 (19.2%) | 284 (15.3%) | 144 (41.6%) | 20 (25%) |

| 2013 | 1251 (54.7%) | 230 (53.5%) | 276 (51.9%) | 745 (56.2%) | 1095 (58.8%) | 156 (45.1%) | 0 (0%) |

| 2014 | 588 (25.7%) | 113 (26.3%) | 149 (28%) | 326 (24.6%) | 482 (25.9%) | 46 (13.3%) | 60 (75%) |

| Population size | |||||||

| ≤ 500 | 816 (35.7%) | 105 (24.4%) | 196 (36.8%) | 515 (38.9%) | 802 (43.1%) | 14 (4.0%) | 0 (0%) |

| 501–999 | 458 (20%) | 73 (17%) | 101 (19%) | 284 (21.4%) | 410 (22%) | 39 (11.3%) | 9 (11.3%) |

| ≥ 1000 | 1013 (44.3%) | 252 (58.6%) | 235 (44.2%) | 526 (39.7%) | 649 (34.9%) | 293 (84.7%) | 71 (88.8%) |

| Child characteristics | |||||||

| Sex of child | |||||||

| Male | 1156 (50.5%) | 217 (50.7%) | 272 (51.1%) | 667 (50.3%) | 941 (50.6%) | 175 (50.6%) | 40 (50%) |

| Female | 1131 (49.5%) | 213 (49.5%) | 260 (48.9%) | 658 (49.7%) | 920 (49.4%) | 171 (49.4%) | 40 (50%) |

| Type of child health check completed in the last 12 months | |||||||

| MBS 715 | 928 (40.6%) | 175 (40.7%) | 229 (43%) | 524 (39.6%) | 928 (40.6%) | 781 (42%) | 117 (33.8%) |

| Other child health check | 587 (25.7%) | 120 (27.9%) | 147 (27.6%) | 320 (24.2%) | 587 (25.7%) | 462 (24.8%) | 111 (32.1%) |

| Not known / not recorded | 772 (33.8%) | 135 (31.4%) | 156 (29.3%) | 481 (36.3%) | 772 (33.8%) | 618 (33.2%) | 118 (34.1%) |

| Reason for last clinic attendance | |||||||

| Acute care | 1145 (50.1%) | 210 (48.8%) | 271 (50.9%) | 664 (50.1%) | 1145 (50.1%) | 945 (50.8%) | 163 (47.1%) |

| Immunisation | 324 (14.2%) | 80 (18.6%) | 87 (16.4%) | 157 (11.8%) | 324 (14.2%) | 233 (12.5%) | 73 (21.1%) |

| Child health check | 515 (22.52%) | 93 (21.63%) | 112 (21.05%) | 310 (23.4%) | 515 (22.52%) | 418 (22.46%) | 80 (23.12%) |

| Other | 303 (13.2%) | 47 (10.9%) | 62 (11.7%) | 194 (14.6%) | 303 (13.2%) | 265 (14.2%) | 30 (8.7%) |

CQI Continuous Quality Improvement

Clinic procedures

The annual child health checks were implemented by trained accredited nurses using standardised equipment (including Hemocue™ hemoglobinometers, electronic weighing scales and stadiometers) that were regularly calibrated according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Annual weight measurements, height measurements and blood samples (heel [6–11 months] or finger prick [≥12 months] were taken from each child using standard operating procedures and calibrated hemoglobinometers. [20] Formal laboratory full blood examinations (FBE) using venous samples were only taken when there was specific concerns about a child. The annual child health checks also included advice about breastfeeding and healthy foods, treatment of abnormal hemoglobin measurements, assessment of oral health, assessment of developmental milestones and discussion about social and emotional needs. [13, 21–26]

Data collection

Audits of medical records were performed annually by participating primary health care centers. Records were eligible for inclusion if they were from children i) aged 6–59 months at the time of the audit; ii) resident in the community for 6 months or more (for children aged < 12 months resident for at least 50% of time since birth); and iii) with no major health problem such as congenital abnormalities. If a center had 30 or less eligible children, all records were audited. In larger centers 30 files were randomly selected. Children were excluded if they had not attended the clinic in the preceding 12 months.

A standardised audit tool was used to collect data from selected clinic records. Child characteristics included: birth date, age, sex, Indigenous status, attendance at the clinic in the last 12 months, reason for most recent attendance and provision of any type of child health screening in the previous 12 months. Heath center characteristics included governance (Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Service or government health service), location (urban, rural, remote), population catchment area, and the number of CQI audits the primary care center had completed.

The audit tool included five coded items that related to the quality of anemia care. The auditors scored ‘yes’ if there had been any description in the client file in the previous 12 months of: (i) advice about breastfeeding, (ii) nutrition advice to the mother or child about healthy foods and the minimum acceptable diet, (iii) advice about food security (discussion including availability, affordability, accessibility and attainment and storage of appropriate and nutritious foods on a regular and reliable basis), (iv) hemoglobin measurement, (v) follow up for children with anemia including nutrition advice, iron treatment and repeat hemoglobin measurements within 2 months. Items were ‘not applicable’ if they were not specified in the guidelines for children of that age in the particular state or territory. [13]

Definitions

A composite measure of ‘quality of anemia care’ was defined as documentation in the child’s file of the two items required for all children aged 6–59 months (i) the child’s caregiver had received nutrition advice about healthy foods and the minimum acceptable diet and (ii) the child had received a hemoglobin measurement in the past 12 months. The composite measure was scored as ‘yes’ if both areas were documented in the client file.

A child was defined as having ‘abnormal hemoglobin levels’ according to the clinical practice guidelines in their state or territory for a child of that age (hemoglobin cut point of 100, 105 or 110 g/dl). ‘Anemia’ was defined according to the World Health Organization guidelines as a hemoglobin level less than 110 g/dl for children aged 6–59 months. [27]

Geographic location was defined using categories from the Accessibility/Remoteness Index of Australia (ARIA). [28] The ARIA index was developed by the Commonwealth Department of Health and Aged Care to define remoteness based on accessibility/road distances to service centers. The index includes five categories ranging from 1 (Highly accessible) to 5 (Very remote). In this study ‘urban’ was defined as ARIA category 1, ‘rural’ included ARIA categories 2–4 and ‘remote’ was ARIA category 5.

Statistical analysis

The primary outcome measure was the proportion of children who received the composite measure of anemia care. Our primary objective was to compare the proportion of children who received the composite measure of anaemia care who were aged 6–11 months with children who were aged 12–59 months.

We calculated that a sample size of 2000 children in our study provided 90% power to detect a difference of at least 10% in the quality of anemia care between those aged 6–11 months and 12–59 months. This calculation assumed a 5% significance level, a baseline quality of care of 50% in those 6–11 months of age and a ratio of 1:2 for those aged 6–11 months and 12–59 months of age.

Unadjusted and adjusted odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) were calculated to assess the association between key characteristics, including age (6–11, 12–23, 24–59 months), geographic location and delivery of anemia care. Multilevel binomial generalised estimating equation models with an exchangeable correlation structure and robust standard errors were used with primary care center as the clustering variable. To adjust for potential confounding, multivariable regression models were constructed a priori which included variables: age, sex of child, geographic location, governance structure, CQI participation and year of data collection. Data analyses were conducted using STATA 13.1.

Results

General characteristics

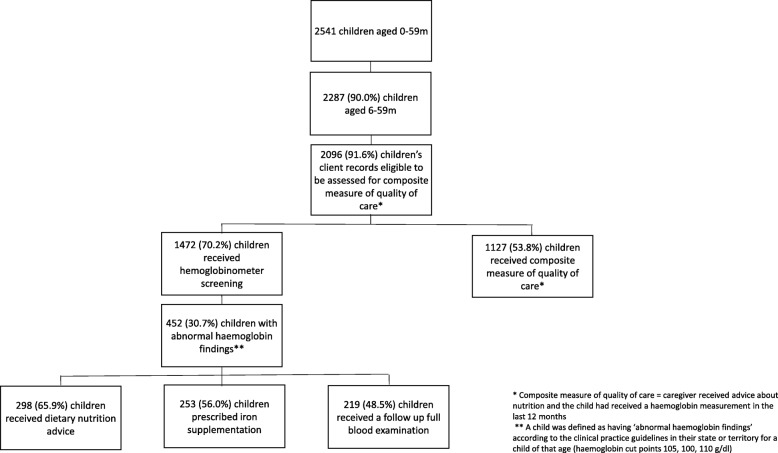

Our study included audits of clinical records for 2287 Indigenous children aged 6 to 59 months who visited one of 109 primary health care centers across Australia during 2012 to 2014, inclusive. Nineteen percent (430) of audits were for children 6 to 11 months of age, 23% (532) 12 to 23 months of age and 58% (1325) 24 to 59 months of age (Table 1, Fig. 1). Health service and child characteristics were similar between different age groups (Table 1). Only 3 % (80) of children were from urban centers whilst over 80% (1861) were from remote areas and 15% (346) from rural areas (Table 1).

Fig. 1.

Participant flow chart

The audit of clinical records showed that our composite measure of quality of anemia care was completed in 54% (1127) of children (Table 2). The proportion of families with a record of receiving specific services ranged from 76% (728) of families who were reported to be educated about breastfeeding to only 10% (92) for advice about food security.

Table 2.

Anaemia care by age and geographic location in Indigenous children aged 6–59 months

| Eligible primary care centres n (%) | Number of client records assesseda n (%) | Proportion receiving care n (%) | Age (months) | Geographic location | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6–11 n (%) | 12–23 n (%) | 24–59 n (%) | Remote | Rural | Urban | ||||

| Total | 109 (100%) | 2287 | 2287 | 430 (18.8%) | 532 (23.3%) | 1325 (57.9%) | 1861 (81.4%) | 346 (15.1%) | 80 (3.5%) |

| Anaemia care | |||||||||

| Anticipatory guidance | |||||||||

| Breastfeeding (< 2 years) | 109 (100%) | 962 (42.1%) | 728 (75.7%) | 376 (87.4%) | 352 (66.2%) | N/A | 638 (80.6%) | 64 (53.8%) | 26 (51%) |

| Nutrition advice | 109 (100%) | 2287 (100%) | 1665 (72.8%) | 344 (80%) | 434 (81.6%) | 887 (66.9%) | 1373 (73.8%) | 233 (67.3%) | 59 (73.8%) |

| Food security | 109 (100%) | 899 (39.3%) | 92 (10.2%) | 29 (15.9%) | 29 (13.9%) | 34 (6.7%) | 66 (9.4%) | 20 (11.4%) | 6 (25%) |

| Child health surveillance | |||||||||

| Haemoglobin documented in last 12 months | 109 (100%) | 2096 (91.6%) | 1472 (70.2%) | 195 (49.9%) | 381 (76.5%) | 896 (74.2%) | 1343 (74.8%) | 109 (41.8%) | 20 (50%) |

| Follow up of abnormal findingsb | |||||||||

| Dietary/nutrition advice | 109 (100%) | 452 (19.8%) | 298 (65.9%) | 51 (65.4%) | 115 (71%) | 132 (62.3%) | 258 (63.5%) | 34 (85%) | 6 (100%) |

| Prescription of iron supplement | 109 (100%) | 452 (19.8%) | 253 (56.0%) | 40 (51.3%) | 97 (59.9%) | 116 (54.7%) | 239 (58.9%) | 11 (27.5%) | 3 (50%) |

| Follow-up FBE or haemoglobin within 2 months | 109 (100%) | 452 (19.8%) | 219 (48.5%) | 40 (51.3%) | 76 (46.9%) | 103 (48.6%) | 208 (51.2%) | 7 (17.5%) | 4 (66.7%) |

| Composite measure of quality of carec | 109 (100%) | 2096 (91.6%) | 1127 (53.8%) | 164 (41.9%) | 322 (64.7%) | 641 (53.1%) | 1012 (56.4%) | 95 (36.4%) | 20 (50%) |

CQI Continuous Quality Improvement, FBE Full blood examination

aProportions are less than 100% if the service is not included in the best practice guidelines for children of that age

bA child was defined as having ‘abnormal haemoglobin findings’ according to the clinical practice guidelines in their state or territory for a child of that age (haemoglobin cut points 105, 100, 110 g/dl)

cCaregiver received advice about nutrition and the child had received a haemoglobin measurement in the last 12 months

Age and geographic location

There was a strong association between anemia care and age group. Children aged 6 to 11 months (164, 41.9%) were 52% less likely to receive the composite measure compared to those aged 12–59 months (963, 56.5%) (Tables 2 and 3). Children aged 6 to 11 months (195, 49.9%) were also 71% less likely to receive a hemoglobin screening measurement compared to those aged 12–59 months (1277, 74.9%) (Tables 2 and 3).

Table 3.

Association between key characteristics and anaemia care in Indigenous children aged 6–59 months

| Total number | Number that received composite measure | OR (95% CI) | P value | aORa (95% CI) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 2096 | 1127 (53.8%) | ||||

| Health service characteristics | ||||||

| Geographic location | ||||||

| Remote | 1795 | 1012 (56.4%) | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Non remote | 301 | 115 (38.2%) | 0.30 (0.14, 0.62) | 0.001 | 0.34 (0.15, 0.74) | 0.006 |

| CQI participation (number of audits completed) | ||||||

| 1 | 349 | 149 (42.7%) | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| 2 | 523 | 253 (48.4%) | 1.49 (0.63, 3.50) | 0.360 | 1.06 (0.45, 2.50) | 0.899 |

| ≥ 3 | 1224 | 725 (59.2%) | 2.27 (1.07, 4.83) | 0.033 | 1.71 (0.81, 3.62) | 0.161 |

| Governance | ||||||

| Aboriginal community controlled health service | 388 | 194 (50%) | 0.81 (0.44, 1.51) | 0.511 | 1.06 (0.56, 2.03) | 0.856 |

| Government health service | 1708 | 933 (54.6%) | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Health service provider who first saw the child | ||||||

| Indigenous health worker | 255 | 120 (47.1%) | 0.83 (0.65, 1.07) | 0.158 | 0.85 (0.65, 1.10) | 0.220 |

| Nurse | 1500 | 822 (54.8%) | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| General practitioner | 225 | 118 (52.4%) | 1.05 (0.76, 1.45) | 0.770 | 1.11 (0.80, 1.54) | 0.519 |

| Other | 99 | 56(56.6%) | 1.02 (0.66, 1.57) | 0.943 | 1.01 (0.65, 1.56) | 0.964 |

| Missing | 17 | 11 (64.7%) | ||||

| Year of data collection | ||||||

| 2012 | 418 | 210 (50.2%) | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| 2013 | 1114 | 577 (51.8%) | 0.99 (0.51, 1.92) | 0.976 | 0.68 (0.37, 1.25) | 0.218 |

| 2014 | 564 | 340 (60.3%) | 1.33 (0.64, 2.77) | 0.445 | 1.20 (0.62, 2.32) | 0.599 |

| Population size | ||||||

| ≤ 500 | 782 | 390 (49.9%) | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| 501–999 | 420 | 250 (59.5%) | 1.41 (0.79, 2.52) | 0.243 | 2.27 (1.22, 4.26) | 0.010 |

| ≥ 1000 | 894 | 487 (54.5%) | 1.20 (0.74, 1.96) | 0.464 | 2.02 (1.27, 3.20) | 0.003 |

| Child characteristics | ||||||

| Age of child | ||||||

| 6-11 m | 391 | 164 (41.9%) | 0.57 (0.41, 0.79) | 0.001 | 0.55 (0.39, 0.78) | 0.001 |

| 12-23 m | 498 | 322 (64.7%) | 1.60 (1.30, 1.97) | < 0.001 | 1.63 (1.31, 2.03) | < 0.001 |

| 24-59 m | 1207 | 641 (53.1%) | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Sex of child | ||||||

| Male | 1055 | 573 (54.3%) | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Female | 1041 | 554 (53.2%) | 0.98 (0.85, 1.13) | 0.777 | 0.98 (0.85, 1.14) | 0.827 |

| Reason for last clinic attendance | ||||||

| Acute care | 1052 | 553 (52.6%) | 0.66 (0.55, 0.79) | < 0.001 | 0.65 (0.54, 0.78) | < 0.001 |

| Immunisation | 296 | 119 (40.2%) | 0.63 (0.51, 0.79) | < 0.001 | 0.63 (0.50, 0.79) | < 0.001 |

| Child health check | 464 | 275 (59.3%) | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Other | 284 | 180 (63.4%) | 0.83 (0.63, 1.11) | 0.206 | 0.81 (0.61, 1.08) | 0.153 |

OR Odds ratio, aOR Adjusted odds ratio

aAdjusted for age, sex, year of data collection, geographic location, governance, CQI participation

The quality of anemia care was strongly associated with location of the health care center. Children attending clinics in non-remote areas (115, 38.2%) were 66% less likely to receive the composite measure compared to those from remote areas (1012, 56.4%) (aOR 0.34, CI 0.15, 0.74) (Tables 2 and 3).

Abnormal findings

The proportion of children who had a hemoglobin measurement within the preceding 12 months and who had abnormal findings (Hb < 100–110 g/dl) was 30.7% (452) (Table 4). Abnormal findings were higher in children aged 6–11 months (78, 40.0%) compared with those 12–59 months of age (374, 29.3%) (Table 4). Children attending clinics in non-remote areas (46, 35.7%) had a similar prevalence of abnormal findings compared to those from remote regions (406, 30.2%) (Table 4).

Table 4.

Associations between key characteristics and abnormal findings in Indigenous children aged 6–59 months

| Total number | Evidence of anaemia | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | n (%) | OR (95% CI) | P value | aOR (95% CI)a | P value | |

| Total | 1472 | 452 (30.7%) | ||||

| Child characteristics | ||||||

| Age of child | ||||||

| 6-11 m | 195 | 78 (40.0%) | 2.28 (1.62, 3.21) | < 0.001 | 2.36 (1.65, 3.39) | < 0.001 |

| 12-23 m | 381 | 162 (42.5%) | 2.62 (2.04, 3.35) | < 0.001 | 2.64 (2.07, 3.38) | < 0.001 |

| 24-59 m | 896 | 212 (23.7%) | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Sex of child | ||||||

| Male | 748 | 225 (30.1%) | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Female | 724 | 227 (31.4%) | 0.99 (0.79, 1.25) | 0.949 | 1.01 (0.79, 1.28) | 0.955 |

| Reason for last clinic attendance | ||||||

| Acute care | 750 | 236 (31.5%) | 1.13 (0.86, 1.50) | 0.380 | 1.13 (0.84, 1.53) | 0.405 |

| Immunisation | 140 | 39 (27.9%) | 0.93 (0.57, 1.52) | 0.773 | 0.87 (0.52, 1.44) | 0.590 |

| Child health check | 341 | 87 (25.5%) | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Other | 241 | 90 (37.3%) | 1.29 (0.86, 1.95) | 0.223 | 1.42 (0.92, 2.20) | 0.114 |

| Health service characteristics | ||||||

| Geographic location | ||||||

| Remote | 1343 | 406 (30.2%) | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Non remote | 129 | 46 (35.7%) | 1.29 (0.68, 2.45) | 0.435 | 0.90 (0.38, 2.12) | 0.805 |

| Number of audit rounds completed | ||||||

| 1 | 215 | 82 (38.1%) | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| 2 | 400 | 145 (36.3%) | 0.93 (0.50, 1.75) | 0.832 | 0.80 (0.44, 1.44) | 0.448 |

| ≥ 3 | 857 | 225 (26.3%) | 0.54 (0.31, 0.93) | 0.026 | 0.47 (0.28, 0.78) | 0.003 |

| Governance | ||||||

| Aboriginal community controlled health service | 233 | 92 (39.5%) | 1.58 (1.03, 2.44) | 0.037 | 1.68 (1.00, 2.83) | 0.052 |

| Government health service | 1239 | 360 (29.1%) | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Health service provider who first saw the child | ||||||

| Indigenous health worker | 158 | 39 (24.7%) | 0.78 (0.55, 1.10) | 0.158 | 0.80 (0.57, 1.13) | 0.201 |

| Nurse | 1087 | 344 (31.6%) | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| General practitioner | 133 | 38 (28.6%) | 1.03 (0.71, 1.50) | 0.858 | 0.96 (0.64, 1.43) | 0.833 |

| Other | 82 | 28 (34.1%) | 1.19 (0.71, 1.97) | 0.511 | 1.39 (0.80, 2.40) | 0.239 |

| Missing | 12 | 3 (25.0%) | ||||

| Year of data collection | ||||||

| 2012 | 253 | 85 (33.6%) | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| 2013 | 763 | 193 (25.3%) | 0.65 (0.40, 1.07) | 0.091 | 0.73 (0.43, 1.25) | 0.255 |

| 2014 | 456 | 174 (38.2%) | 1.29 (0.77, 2.18) | 0.337 | 1.33 (0.76, 2.34) | 0.315 |

| Population size | ||||||

| ≤ 500 | 564 | 145 (25.7%) | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| 501–999 | 306 | 96 (31.4%) | 1.31 (0.74, 2.32) | 0.348 | 1.57 (0.83, 2.95) | 0.165 |

| ≥ 1000 | 602 | 211 (35.1%) | 1.56 (1.02, 2.38) | 0.040 | 1.54 (1.02, 2.33) | 0.041 |

OR Odds ratio, aOR Adjusted odds ratio

aAdjusted for age, sex, year of data collection, geographic location, governance, CQI participation

Treatment and follow up of children diagnosed with abnormal Hb levels was low. Only 65.9% (298) of children with abnormal Hb levels received dietary and nutrition advice, 56.0% (253) were prescribed an iron supplement and 48.5% (219) had a follow-up hemoglobin within 2 months (Table 2). The rates of treatment and follow-up appeared similar between different age groups and geographic regions (remote versus non-remote) (Table 2).

32.2% (475) children were defined as having ‘anemia’ according to WHO criteria (Hb less than 110 g/dl). Levels were lower in younger children (56.9% children aged 6–11 months, 42.8% children aged 12–23 months and 22.4% children aged 24–59 months) (Table 5). Levels were similar in remote and non remote children. Only one child aged 6–11 months had ‘severe anemia’ (Hb < 70 g/dl).

Table 5.

Haemoglobin levels by age group and geographic location in children aged 6–59 months

| Total number | Mean (sd) Hb (g/dl) | Median (IQR) Hb (g/dl) | Range (min-max) Hb (g/dl) | Proportion with Hb < 70 g/dl n (%) | Proportion with Hb < 100 g/dl n (%) | Proportion with Hb < 110 g/dl n (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 1472 | 113.1 (11.1) | 114 (107–120) | 61–158 | 1 (0.1%) | 163 (11.1%) | 475 (32.3%) | |

| 6–11 months | 195 | 107.8 (12.0) | 108 (100–115) | 61–158 | 1 (0.01%) | 45 (23.1%) | 111 (56.9%) | |

| Remote | 184 | 107.8 (11.7) | 108 (100–115) | 75–135 | 0 (0.01%) | 43 (23.4%) | 106 (57.6%) | |

| Non-remote | 11 | 107.4 (17.6) | 111 (102–119) | 61–124 | 1 (0.01%) | 2 (18.2%) | 5 (45.5%) | |

| 12–23 months | 381 | 109.5 (11.8) | 111 (102–117) | 70–148 | 0 (0%) | 73 (19.2%) | 163 (42.8%) | |

| Remote | 344 | 109.4 (11.8) | 111 (102–117) | 70–148 | 0 (0%) | 66 (19.2%) | 149 (43.3%) | |

| Non-remote | 37 | 110.4 (11.8) | 112 (105–119) | 79–129 | 0 (0%) | 7 (18.9%) | 14 (37.8%) | |

| 24–59 months | 896 | 115.7 (9.7) | 115 (110–122) | 83–147 | 0 (0%) | 45 (5.0%) | 201 (22.4%) | |

| Remote | 815 | 115.9 (9.6) | 115 (110–122) | 87–147 | 0 (0%) | 39 (4.8%) | 172 (21.1%) | |

| Non-remote | 81 | 113.0 (10.2) | 113 (107–120) | 83–136 | 0 (0%) | 6 (7.4%) | 29 (35.8%) | |

Hb haemoglobin

Sd standard deviation

IQR interquartile range

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the largest published study describing the quality of anemia care provided to disadvantaged children in primary health care centers. Anemia prevalence was 33% overall and 57% in children aged 6–11 months. Yet only 54% of children received the composite measure of anemia care, 76% of caregivers received nutrition advice, 70% of children had a hemoglobin measurement within the preceding 12 months and only 48% received follow up care for anemia. Young children aged 6–11 months had the poorest quality of care despite having the highest anemia rates. Health centres in remote areas appeared recorded better quality of care than non-remote areas.

The prevalence of anaemia that we reported in our study was similar to anaemia prevalence reported for other disadvantaged children in low and middle income countries globally (especially east and southeast Asia [29%] and southern Africa [30%]). [2] Our rates were also similar to disadvantaged children in high income countries including Inuit children (36%) in Canada [3], urban African-American children (25–35%) in the US [29, 30] and Native Alaskan infants (35%). [31] Rural risk factors for anemia are well known and include tropical diseases and severe food insecurity. However, in both urban and rural areas, poor education levels and poverty also limit food purchasing and the provision of an adequate nutritional intake. [32, 33]

We also found the highest anemia prevalence in children aged 6–11 months (57%) and 12–23 months (43%). Infant anemia is well known to be due to poor maternal nutrition, poor complementary food intake and gastro intestinal infections. [34, 35] Low birth weight and maternal anemia are also important determinants of early onset anemia, [11, 36].

We also reported concerningly low quality of anemia care (54%). Provision of nutrition advice and screening to families by primary care providers in Australia was reported to be as low as 20% in 2011. [14] However, many efforts have been made to improve primary and secondary prevention of anemia in remote areas including training of health care providers, CQI initiatives and community consultation. [37] The quality of anemia care we report this study is substantially better than reported in the 2011 study. These findings are encouraging given the ongoing challenges of high staff turnover and difficulty in accessing professional development in remote areas.

We found six other studies that reported on the poor quality of anemia care for disadvantaged children, [4, 14, 38–42] Of these, one assessed quality of care in infants aged 6 months and compared to older age groups.(38)In our study children aged 6–11 months had the highest anemia burden (56.9%) but were two fold less likely to receive anemia care compared to those aged 12–59 months.

Interestingly, the quality of health centre care in urban areas was significantly poorer than remote areas in our study. This may be due to some participation bias by health centres. i.e., participation was voluntary and more ‘better quality’ health centres may have volunteered in remote than urban areas.. Other possible reasons include difficulties in locating children who live in crowded urban environments, lack of funding for urban based care from local and national governments and lack of community health workers or other ancillary staff to help with communication and follow up. [43] This can result in fragmentation of care with many children receiving care from multiple different service providers. Similar findings have been reported from other high-income urban environments including studies of type 2 diabetes [44], immunisation, [45] and adult preventative health care services. [46]

We also reported poor anemia treatment and follow up in the disadvantaged children in our study. Our low follow up rate (49%) may be explained by the frequent migration between city and country locations commonly seen in disadvantaged families. [14, 47] However, we also reported that only 66% of children with anemia received dietary/nutrition advice and 56% were prescribed an iron supplement at the time of diagnosis. These findings are most likely explained by high staff turnover and the need for ongoing staff trainings. Our standard operating procedures state that nutritional advice and iron therapy should commence immediately while waiting for laboratory results. We have now conducted refresher training in both remote and urban areas and are continuing close follow up of these concerning findings. We are also focusing on ‘structures of care’ such as education and training, capacity building and improvements in the organisation of health systems. [14, 48]

Long term neurodevelopmental and educational outcomes have been linked to early deprivation and micronutrient intake, [11, 12] so it is concerning that very young infants aged 6–11 months had both high levels of anemia and poor quality of care and follow-up in our study. This low prevalence of care for our youngest and most vulnerable infants may be because of the perception that anemia commences later in childhood. [14]

There were some limitations to our study. Some items may not have been documented in client records thus there may have been under reporting of the level of care provided. Participation of health services was voluntary therefore limiting generalisability. We were unable to collect data on cause of anemia e.g. iron deficiency so we cannot comment on aetiology specific issues. We are also aware that our anemia rates were reported only in the 70% of children who received screening for anemia. Children that did not receive screening may be more disadvantaged and have even higher anemia burden. Our anemia burden data relied on capillary samples (heel prick and finger prick) analysed by hemoglobinometers. Venous blood full blood examinations (FBE) are well known to be the gold standard technique for measuring hemoglobin levels. However, there have been many hemoglobinometer diagnostic accuracy studies that report high levels of sensitivity, specificity and level of agreement with venous Coulter samples if the hemoglobinometer is used by well trained staff under optimal situations such as in our study. [49, 50]

Strengths of our study included the large sample size and multicenter design which included a large number of primary health care centers across different regions of Australia. Within the statistical analysis we controlled for confounders such as age, sex, year, geographic location, governance and CQI participation and we feel that residual confounding was unlikely. We also controlled for the effects of clustering of health care centers.

Conclusion

Anemia continues to be an important issue for disadvantaged children in urban, rural and remote areas. In our study children aged 6–11 months had the highest anemia rates but the poorest quality of care. Improving care for these vulnerable children is especially needed. This includes improved training and capacity building of primary care providers in the care of young children, the delivery of standardised health checks and ensuring appropriate follow up and treatment.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the ABCD team, participating health services and CQI facilitators for their assistance with this project.

Abbreviations

- ABCD

Audit for Best Practice in Chronic Disease

- aOR

adjusted odds ratio

- CI

Confidence interval

- CQI

Continuous quality improvement

- FBE

Full blood examinations

- OR

Odds ratio

- PDSA

Plan-do-study-act

Authors’ contributions

CM and KME conceptualised the paper and CM wrote the first draft of the paper and analyses. KM, DM, RB and NAS all made substantial contributions to the conception or design of the work, or the acquisition, analysis or interpretation of data. The work was critically revised for intellectual content by KM, DM, RB and NAS. The final manuscript was reviewed and approved by all authors. All authors also agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Funding

We acknowledge funding from the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) for the for the ABCD National Research Partnership, the Centre for Excellence in Improving health services for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children and the Centre for Excellence in Integrated Quality Improvement. The funding body had no role in the design of the study and collection, analysis, and interpretation of data and in writing the manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are not publicly available due to the lack of an online platform but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The processes for ethical approval and consent to participate were detailed in the original study protocol. [16] Ethics approval was obtained from all Human Research Ethics Committees (HRECs) in the states and territories involved: the Human Research Ethics Committee (HREC) of the Northern Territory Department of Health and Menzies School of Health Research (HREC-EC00153); Central Australian HREC (HREC-12-53); Queensland HREC Darling Downs Health Services District (HREC/11/QTDD/47); South Australian Indigenous Health Research Ethics Committee (04–10-319); Curtin University HREC (HR140/2008); Western Australian Country Health Services Research Ethics Committee (2011/27); Western Australian Aboriginal Health Ethics Committee (111–8/05); and University of Western Australia HREC (RA/4/1/5051). Senior management of all health centres provided consent to participate. Individual patient consent was not required as data were derived from health records and were available to researchers only in de-identified and aggregated form with strict protection of privacy and confidentiality. [16]

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.McLean E, Cogswell M, Egli I, Wojdyla D, de Benoist B. Worldwide prevalence of anaemia, WHO vitamin and mineral nutrition information system, 1993-2005. Public Health Nutr. 2009;12(4):444–454. doi: 10.1017/S1368980008002401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stevens GA, Finucane MM, De-Regil LM, Paciorek CJ, Flaxman SR, Branca F, Pena-Rosas JP, Bhutta ZA, Ezzati M. Nutrition impact model study G. global, regional, and national trends in haemoglobin concentration and prevalence of total and severe anaemia in children and pregnant and non-pregnant women for 1995-2011: a systematic analysis of population-representative data. Lancet Glob Health. 2013;1(1):e16–e25. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(13)70001-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Christofides A, Schauer C, Zlotkin SH. Iron deficiency and anemia prevalence and associated etiologic risk factors in first nations and Inuit communities in northern Ontario and Nunavut. Can J Public Health. 2005;96(4):304–307. doi: 10.1007/BF03405171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sears David, Mpimbaza Arthur, Kigozi Ruth, Sserwanga Asadu, Chang Michelle A., Kapella Bryan K., Yoon Steven, Kamya Moses R., Dorsey Grant, Ruel Theodore. Quality of Inpatient Pediatric Case Management for Four Leading Causes of Child Mortality at Six Government-Run Ugandan Hospitals. PLOS ONE. 2015;10(5):e0127192. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0127192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ewusie JE, Ahiadeke C, Beyene J, Hamid JS. Prevalence of anemia among under-5 children in the Ghanaian population: estimates from the Ghana demographic and health survey. BMC Public Health. 2014;14(1):626. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-14-626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Austin AM, Fawzi W, Hill AG. Anaemia among Egyptian children between 2000 and 2005: trends and predictors. Matern Child Nutr. 2012;8(4):522–532. doi: 10.1111/j.1740-8709.2011.00339.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Xin QQ, Chen BW, Yin DL, Xiao F, Li RL, Yin T, Yang HM, Zheng XG, Wang LH. Prevalence of Anemia and its risk factors among children under 36 months old in China. J Trop Pediatr. 2017;63(1):36–42. doi: 10.1093/tropej/fmw049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lopez A, Cacoub P, Macdougall IC, Peyrin-Biroulet L. Iron deficiency anaemia. Lancet. 2016;387(10021):907–916. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60865-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Khambalia AZ, Aimone AM, Zlotkin SH. Burden of anemia among indigenous populations. Nutr Rev. 2011;69(12):693–719. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-4887.2011.00437.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Marmot M. Social determinants and the health of indigenous Australians. Med J Aust. 2011;194(10):512–513. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2011.tb03086.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Balarajan Y, Ramakrishnan U, Ozaltin E, Shankar AH, Subramanian SV. Anaemia in low-income and middle-income countries. Lancet. 2011;378(9809):2123–2135. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)62304-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Grantham-McGregor S, Ani C. A review of studies on the effect of iron deficiency on cognitive development in children. J Nutr. 2001;131(2S-2):649S–666S. doi: 10.1093/jn/131.2.649S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Department of Health. Health assessment for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people (MBS Item 715). Medicare Benefits Schedule - Note AN.0.44. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia. http://www9.health.gov.au/mbs/fullDisplay.cfm?type=note&qt=NoteID&q=AN.0.44 Accessed 9 Apr 2016

- 14.Bar-Zeev SJ, Kruske SG, Barclay LM, Bar-Zeev N, Kildea SV. Adherence to management guidelines for growth faltering and anaemia in remote dwelling Australian aboriginal infants and barriers to health service delivery. BMC Health Serv Res. 2013;13:250. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-13-250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bailie RS, Si D, O'Donoghue L, Dowden M. Indigenous health: effective and sustainable health services through continuous quality improvement. Med J Aust. 2007;186(10):525–527. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2007.tb01028.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bailie R, Si D, Connors C, Weeramanthri T, Clark L, Dowden M, O'Donohue L, Condon J, Thompson S, Clelland N, et al. Study protocol: audit and best practice for chronic disease extension (ABCDE) project. BMC Health Serv Res. 2008;8:184. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-8-184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bailie R, Si D, Shannon C, Semmens J, Rowley K, Scrimgeour DJ, Nagel T, Anderson I, Connors C, Weeramanthri T, et al. Study protocol: national research partnership to improve primary health care performance and outcomes for indigenous peoples. BMC Health Serv Res. 2010;10:129. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-10-129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Edmond KM, McAuley K, McAullay D, Matthews V, Strobel N, Marriott R, Bailie R. Quality of social and emotional wellbeing services for families of young indigenous children attending primary care centers; a cross sectional analysis. BMC Health Serv Res. 2018;18(1):100. doi: 10.1186/s12913-018-2883-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McAullay D, McAuley K, Bailie R, Mathews V, Jacoby P, Gardner K, Sibthorpe B, Strobel N, Edmond K. Sustained participation in annual continuous quality improvement activities improves quality of care for aboriginal and Torres Strait islander children. J Paediatr Child Health. 2018;54(2):132–140. doi: 10.1111/jpc.13673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Department of Health. Heel prick blood collection. In: Child and Adolescent Community Health, ed. Western Australia: Child and Adolescent Health Service, Department of Health; 2016.

- 21.NACCHO/RACGP . National guide to a preventive health assessment for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. 2. South Melbourne: The RACGP; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kimberley Aboriginal Medical Services Council (KAMSC), WA Country Health Service (WACHS) Kimberley . Healthy Kids. 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kimberley Aboriginal Medical Services Council (KAMSC), WA Country Health Service (WACHS) Kimberley . Anaemia in children. 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Queensland Health. Internet: https://www.health.qld.gov.au/rrcsu/html/health-check-forms Accessed 20 April 2016.

- 25.Queensland Health . Royal Flying Doctor Service (Queensland section). Primary clinical care manual 9th edition. Cairns: The Rural and Remote Clinical Support Unit, Torres and Cape Hospital and Health Service; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Remote Primary Health Care Manuals . CARPA standard treatment manual. 7. Alice Springs: Centre for Remote Health; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 27.WHO . Haemoglobin concentrations for the diagnosis of anaemia and assessment of severity. Vitamin and Mineral Nutrition Information System. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Commonwealth Department of Health and Aged Care. Measuring remoteness: Accessibility/remoteness index of Australia (ARIA). Revised edition: Occasional Papers: New Series Number 14; 2001. Canberra.

- 29.Bogen DL, Krause JP, Serwint JR. Outcome of children identified as anemic by routine screening in an inner-city clinic. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2001;155(3):366–371. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.155.3.366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bogen DL, Duggan AK, Dover GJ, Wilson MH. Screening for iron deficiency anemia by dietary history in a high-risk population. Pediatrics. 2000;105(6):1254–1259. doi: 10.1542/peds.105.6.1254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gessner BD. Geographic and racial patterns of anemia prevalence among low-income Alaskan children and pregnant or postpartum women limit potential etiologies. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2009;48(4):475–481. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0b013e3181888fac. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gracey M, King M. Indigenous health part 1: determinants and disease patterns. Lancet. 2009;374(9683):65–75. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60914-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.ABS . Food security. Canberra: ABS; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hipgrave DB, Fu X, Zhou H, Jin Y, Wang X, Chang S, Scherpbier RW, Wang Y, Guo S. Poor complementary feeding practices and high anaemia prevalence among infants and young children in rural central and western China. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2014;68(8):916–924. doi: 10.1038/ejcn.2014.98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wirth JP, Rohner F, Woodruff BA, Chiwile F, Yankson H, Koroma AS, Russel F, Sesay F, Dominguez E, Petry N, et al. Anemia, micronutrient deficiencies, and malaria in children and women in Sierra Leone prior to the Ebola outbreak - findings of a cross-sectional study. PLoS One. 2016;11(5):e0155031. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0155031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ayoya Mohamed Ag, Ngnie-Teta Ismael, Séraphin Marie Nancy, Mamadoultaibou Aissa, Boldon Ellen, Saint-Fleur Jean Ernst, Koo Leslie, Bernard Samuel. Prevalence and Risk Factors of Anemia among Children 6–59 Months Old in Haiti. Anemia. 2013;2013:1–3. doi: 10.1155/2013/502968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Australian Institute of Health and Welfare . Australia’s health 2016. Australia’s health series no. 15. Cat. no. AUS 199. Canberra: AIHW; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bailie RS, Si D, Dowden MC, Connors CM, O'Donoghue L, Liddle HE, Kennedy CM, Cox RJ, Burke HP, Thompson SC, et al. Delivery of child health services in indigenous communities: implications for the federal government's emergency intervention in the Northern Territory. Med J Aust. 2008;188(10):615–618. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2008.tb01806.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.McLennan JDS, M. Anemia screening and treatment outcomes of children in a low-resource Community in the Dominican Republic. J Trop Pediatr. 2016;62:116–122. doi: 10.1093/tropej/fmv084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Crowell R, Pierce MB, Ferris AM, Slivka H, Joyce P, Bernstein BA, Russell-Curtis S. Managing anemia in low-income toddlers: barriers, challenges and context in primary care. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2005;16(4):791–807. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2005.0092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kempe A, Beaty B, Englund BP, Roark RJ, Hester N, Steiner JF. Quality of care and use of the medical home in a state-funded capitated primary care plan for low-income children. Pediatrics. 2000;105:1020–1028. doi: 10.1542/peds.105.5.1020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Biondich PG, Downs SM, Carroll AE, Laskey AL, Liu GC, Rosenman M, Wang J, Swigonski NL. Shortcomings in infant iron deficiency screening methods. Pediatrics. 2006;117(2):290–294. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-2103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ware V. Improving access to urban and regional early childhood services. Resource sheet no. 17. Produced for the closing the gap clearinghouse. Cnberra: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, Melbourne: Australian Institute of Family Studies,, 2012.

- 44.Matthews V, Schierhout G, McBroom J, Connors C, Kennedy C, Kwedza R, Larkins S, Moore E, Thompson S, Scrimgeour D, et al. Duration of participation in continuous quality improvement: a key factor explaining improved delivery of type 2 diabetes services. BMC Health Serv Res. 2014;14:578. doi: 10.1186/s12913-014-0578-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.O'Grady KA, Krause V, Andrews R. Immunisation coverage in Australian indigenous children: time to move the goal posts. Vaccine. 2009;27(2):307–312. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2008.09.096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bailie RS, Si D, Connors CM, Kwedza R, O'Donoghue L, Kennedy C, Cox R, Liddle H, Hains J, Dowden MC, et al. Variation in quality of preventive care for well adults in indigenous community health centres in Australia. BMC Health Serv Res. 2011;11:139. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-11-139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Aquino D, Marley J, Senior K, Leonard D, Joshua A, Huddleston A, Ferguson H, Helmer J, Hadgraft N, Hobson V. Early childhood nutrition and anaemia prevention project Darwin: The Fred Hollows Foundation, Indigenous Australia Program. 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Strobel Natalie A., McAuley Kimberley, Matthews Veronica, Richardson Alice, Agostino Jason, Bailie Ross, Edmond Karen M., McAullay Daniel. Understanding the structure and processes of primary health care for young indigenous children. Journal of Primary Health Care. 2018;10(3):267. doi: 10.1071/HC18006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cohen AR, Seidl-Friedman J. HemoCue system for hemoglobin measurement. Evaluation in anemic and nonanemic children. Am J Clin Pathol. 1988;90(3):302–305. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/90.3.302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mills AF, Meadows N. Screening for anaemia: evaluation of a haemoglobinometer. Arch Dis Child. 1989;64(10):1468–1471. doi: 10.1136/adc.64.10.1468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are not publicly available due to the lack of an online platform but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.