Abstract

How plasma membrane (PM) cholesterol is controlled is poorly understood. Ablation of the gene encoding the ER stress steroidogenic acute regulatory-related lipid transfer domain (StarD)5 leads to a decrease in PM cholesterol content, a decrease in cholesterol efflux, and an increase in intracellular neutral lipid accumulation in macrophages, the major cell type that expresses StarD5. ER stress increases StarD5 expression in mouse hepatocytes, which results in an increase in accessible PM cholesterol in WT but not in StarD5−/− hepatocytes. StarD5−/− mice store higher levels of cholesterol and triglycerides, which leads to altered expression of cholesterol-regulated genes. In vitro, a recombinant GST-StarD5 protein transfers cholesterol between synthetic liposomes. StarD5 overexpression leads to a marked increase in PM cholesterol. Phasor analysis of 6-dodecanoyl-2-dimethylaminonaphthalene fluorescence lifetime imaging microscopy data revealed an increase in PM fluidity in StarD5−/− macrophages. Taken together, these studies show that StarD5 is a stress-responsive protein that regulates PM cholesterol and intracellular cholesterol homeostasis.

Keywords: cholesterol trafficking, macrophages, endoplasmic reticulum, Niemann-Pick C, fluorescence, steroidogenic acute regulatory protein-related lipid transfer proteins, fatty liver, steroidogenic acute regulatory-related lipid transfer domain 5

Cholesterol can be synthesized de novo within the ER, or taken up from outside the cell via receptor-mediated endocytosis (1). Most cellular cholesterol is acquired from lipoproteins, which deliver cholesterol to the lysosomes. Cholesterol then flows to the ER and back to the plasma membrane (PM) against a cholesterol concentration gradient (2) or, from the lysosomes, first travels to the PM and then to the ER to suppress both cholesterol uptake and synthesis (3). Cholesterol movement is very fast (t1/2 ∼10 min) (4), bidirectional, and independent of the secretory pathway (5); hence, nonvesicular mechanisms must exist to transfer cholesterol from inside the cell to the PM (6).

Within the PM, cholesterol plays an essential role in regulating fluidity, lipid raft structure, cell signaling, and cholesterol efflux (7–10). This is essential for membrane function because the amount of cholesterol content impacts the order and fluidity of the membrane. However, it is still unknown how mammalian cells maintain cholesterol gradients and maintain different cholesterol to phospholipid ratios. Thus, in the PM, the cholesterol/phospholipid ratio is 1.0, whereas in the ER that ratio is only 0.15 (11). Das et al. (12) recently reported that PM cholesterol exists in three pools: a residual or essential pool, which does not change significantly, but is essential for membrane integrity; a sphingomyelin-sequestered pool, which likely participates in lipid raft-associated membrane functions; and an easily accessible cholesterol pool, available for cholesterol efflux. These observations emphasize the need to elucidate the mechanisms regulating how newly synthesized or exogenous cholesterol taken from the diet is sensed in the ER and moves within the cell to maintain cholesterol homeostasis.

The ability of a cell to increase cholesterol in the PM while decreasing its cholesterol content in the ER and Golgi is regarded as a key element of the acute ER stress cell survival response. The mechanisms by which cholesterol is transferred from the lumen of lysosomes to the lysosomal membrane, prior to being carried to the PM, have been unraveled and involve the action of the Niemann-Pick C (NPC)1 and NPC2 lysosomal proteins (13). Recently, Mesmin and Antonny (14) have described an oxysterol-binding protein (OSBP)-mediated transfer of cholesterol from the ER to the trans Golgi; potentially unraveling one further step in the movement of cholesterol from inside the cell to the PM (14). However, it still remains unclear how cholesterol is then transferred from the lysosome to the ER, and from the ER/Golgi to the PM. The fluctuations in PM cholesterol content and the need of a rapid cholesterol delivery response suggest that a mechanism(s) of transport of a nonvesicular nature must exist.

A family of lipid-binding proteins, known as the START proteins, contains a conserved steroidogenic acute regulatory protein-related lipid transfer (START) domain that forms a hydrophobic pocket for lipid binding (15). Members of this family of proteins include steroidogenic acute regulatory-related lipid transfer domain (StarD)1, MLN64 (StarD3), the phosphatidylcholine transfer protein (PC-TP/StarD2), and StarD4 and StarD5, which form a subfamily of START proteins (16). Whereas StarD1 and StarD3 have a targeting sequence or membrane spanning domain, respectively, StarD4 and -5 lack an identifiable targeting domain; and are only 205–233 amino acids in size consisting almost entirely of a START-domain (16). Unlike StarD1, which is known to distribute cholesterol to the mitochondria (17), and StarD3, which appears to mediate ER-to-endosome cholesterol transport (18), the function of StarD5 remains uncertain.

It has previously been shown that StarD5 expression is induced upon ER stress (19, 20). We have shown that StarD5 binds cholesterol (21), associates with the Golgi and ER (19, 22), and is abundant in immune-mediating cells (22). These observations suggested a role for StarD5 in cell membrane stabilization through alterations of the PM cholesterol concentration and, subsequently, membrane fluidity and permeability. However, StarD5 function remains unknown.

In this study, we employed a CRISPR/Cas9 strategy to generate a StarD5 KO (StarD5−/−) mouse line to study the role of StarD5 in intracellular cholesterol distribution and homeostasis. The studies presented here show a correlation between StarD5 protein presence, PM and intracellular cholesterol content, and PM physical state.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) WT cell line was from ATCC and the CHO 10-3 NPC1 mutant cell line was a gift from the Liscum laboratory (23). The Amplex Red cholesterol assay kit was from Invitrogen. The Infinity triglyceride assay kit was from Thermo Fisher Scientific. Primers and fluorescent probes for quantitative (q)RT-PCR (supplemental Table S1) were from Integrated DNA Technologies (Coralville, IA). Alexa Fluor 488 C5-maleimide, Acldl, apoA1, and SuperSignal West Pico chemiluminiscent substrate were from Thermo Fisher Scientific. F4/80 pluriBeads and M-pluriBead Mini reagent kit were from pluriSelect (San Diego, CA). Polyclonal anti-StarD5 antibody from Santa Cruz (catalog #sc-66668) was used to quantify mouse StarD5 protein. Polyclonal anti-StarD5 prepared as described (21) was used to quantify human StarD5 protein. Polyclonal anti-StarD4 was described previously (24). Polyclonal anti-β-actin (catalog #A5441) and anti-Flag (catalog #F7425) were from Sigma-Aldrich. Monoclonal anti-CCAAT-enhancer-binding protein homologous (CHOP) was from Thermo Fisher Scientific (catalog #MA1-250); anti-protein disulfide isomerase (PDI) was from Abcam (catalog #ab2792); anti-Na+/K+ ATPase α-1 was from Millipore (catalog #05-369); and goat anti-rabbit HRP-conjugated IgG (catalog #170-6515), goat anti-mouse HRP-conjugated IgG (catalog #170-6516), and rabbit anti-goat HRP-conjugated IgG were from Bio-Rad (catalog #172-1034). Egg phosphatidylcholine (PC) was from Avanti Polar Lipids (catalog #840051), Cholesterol was from Steraloids. [3H]cholesterol and [14C]oleoyl-CoA were from PerkinElmer. The RNeasy Plus mini kit was from Qiagen. The Brilliant III Ultra-Fast QRT-PCR Master Mix kit was from Agilent. Filipin was from Cayman Biochemicals; cholesterol oxidase was from Calbiochem, BODIPY 493/503 was from Fisher Scientific; cAMP, cyclosporin A, and other general chemicals were from Sigma. Ad-StarD4 was prepared as described before (25). Ad-StarD5 was prepared by SignaGen Laboratories using a plasmid encoding the human StarD5 cDNA fused to myc and flag tags driven by the CMV promoter (catalog #RC202407), which was from Origene. Multiplicity of infection (MOI) was quantified with the Adeno-X Rapid Test kit from Clontech. The 6-dodecanoyl-2-dimethylaminonaphthalene (LAURDAN) was from Fisher Scientific.

Animal studies

All animal studies and care were performed under the guidelines of the Virginia Commonwealth University (VCU) and McGuire Veterans Affairs Medical Center IACUCs, in accordance with the principles and procedures outlined in the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals under assurance number A3281-01. Animals were housed in individually ventilated cages in a barrier vivarium, which excludes all known mouse viruses and parasites and most bacteria (including helicobacter). The mice were fed standard mouse chow (irradiated Teklad LM-485 diet) and autoclaved water. Mice of both sexes and multiple ages were euthanized under isoflurane anesthesia followed by cervical dislocation for collection of liver tissue.

Generation of StarD5−/− mice

A CRISPR/Cas9 approach was employed to generate StarD5 KO mice, using methods described by Low, Kutny, and Wiles (26). A guide RNA sequence was selected using a combination of the MIT CRISPR design tool developed by Feng Zhang (27) and a second design tool developed by Doench et al. (28). The 20 nt guide sequence selected (supplemental Fig. S1A, B; shown in blue) had a crispr.mit.edu score of 95, indicating a very low likelihood of off-target cleavage, and was predicted to create a double-strand cleavage 10 bp upstream of the translational start site. The biologically active sgRNA was generated as described (26), using RNA templates from Integrated DNA Technologies. Homology-directed repair at the cleavage site utilized a 200 nt single-stranded oligodeoxynucleotide (ssODN) with homology to StarD5 exon 1 and the 5′-flanking region (supplemental Fig. S1A, C). The ssODN contained a single-base deletion in codon 2 that induces a translational frame-shift, as well as eight mutations upstream of the start codon that: 1) create an optimized Kozak sequence for efficient translational initiation; 2) eliminate the Cas9 PAM sequence to prevent retargeting; and 3) create a BglI site for screening purposes (supplemental Fig. S1C shows a partial sequence of the ssODN). A mix containing 10 ng/μl Cas9 mRNA (purchased from TriLink BioTechnologies), 10 ng/μl sgRNA, and 10 ng/μl ssODN was microinjected into the pronuclei of fertilized C57BL/6J mouse eggs by the VCU Transgenic/Knockout Mouse Core using standard methods. Microinjected eggs were implanted into the oviducts of ICR pseudopregnant females, and the resulting pups were screened for the desired KO allele by PCR amplification of a 661 bp product spanning the targeted region, followed by BglI digestion of PCR products (supplemental Fig. S1E). PCR primer sequences were (5′-ACCAAGGGGTAAACATCCAAACTC-3′) and (5′-AGAGGGATTGTGCAACAATGAACG-3′). Five potential founders were selected for breeding and further characterization, including DNA sequencing. One line carrying the desired sequence changes as well as a short deletion upstream of the Kozak sequence was ultimately selected for study (supplemental Fig. S1D). Heterozygotes were bred to each other, yielding homozygous offspring with the expected frequency (supplemental Fig. S1E). Western blot analysis confirmed that homozygous KO mice expressed no StarD5 (supplemental Fig. S1F).

Isolation of murine peritoneal macrophages and hepatocytes

Peritoneal macrophages from WT and StarD5−/− mice were isolated 4 days after intraperitoneal injection of 3% thioglycollate solution. The mice were euthanized, and then cold DMEM medium was injected into the peritoneal cavity using an 18 gauge needle and aspirated to harvest the peritoneal macrophages. Then macrophages were positively selected with F4/80 pluriBeads and M-pluriBead Mini reagent kit. Macrophages were then plated as indicated. Primary hepatocytes were isolated from WT and StarD5−/− mice as previously described (29, 30).

Isolation of peritoneal macrophage PM

PM was isolated from peritoneal macrophages as described (31) and cultured in 100 mm dishes. After 3 days, cells were washed twice with cold PBS and harvested in 1 ml of buffer A [250 mM sucrose, 20 mM tricine, and 1 mM EDTA (pH 7.8)]. The cells were broken in a glass homogenizer with 20 strokes. The homogenate was transferred to a 1.5 ml tube and centrifuged at 1,000 g for 10 min in a tabletop centrifuge at 4°C. The post-nuclear supernatant (PNS) was collected and stored on ice. The process of homogenization and centrifugation was repeated with the pellet collected and pooled with the PNS. The PNS was layered on the top of 12 ml of 30% Percoll in buffer A and centrifuged at 84,000 g for 30 min at 4°C. The PM fraction, visible as a band/ring at a distance of 2 cm from the top of the tube, was collected. This PM fraction contained Percoll and it was removed by centrifugation at 105,000 g for 90 min. Percoll formed a tightly packed pellet at the bottom of the tube. The PM fraction was floating above the pellet and it was carefully removed and resuspended in buffer A.

Cholesterol and triglyceride quantification

Macrophages (8 ×106) were harvested and resuspended in 0.8 ml of PBS and sonicated for 20 min in a glass tube. Then, proteinase K was added at 1 μg/ml final concentration and incubated for 5 h at 50°C. Then, 16 ml of a chloroform:methanol (2:1) solution were added and incubated at room temperature (23–25°C) for 18 h. For livers, 0.1 g of tissue was homogenized in 0.7 ml of 1% NP-40, 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 150 mM NaCl, and 0.05% SDS, and sonicated. From the homogenates, 0.1 ml was incubated with 3.5 ml of a chloroform:methanol (2:1) solution at room temperature (23–25°C) for 18 h. To separate the phases, 1 ml of HPLC grade water was added and the tube centrifuged at 1,800 g for 10 min. The methanol-water phase was removed, and the chloroform phase (containing the lipids) was evaporated under nitrogen. The lipids were finally resuspended in a solution of isopropanol-10% Triton X-100. PM cholesterol was quantified without lipid extraction. Total and free cholesterol were measured using the Amplex Red cholesterol assay kit. To calculate the amount of cholesterol esters, the free cholesterol was subtracted from the total cholesterol. Triglycerides were measured using the Infinity triglyceride assay kit.

Immunoblots

Protein samples from cultured cells and tissues were separated on 12% SDS-PAGE gels and then transferred onto a PVDF membrane using a Bio-Rad semidry transfer cell apparatus. The membrane was transferred to a blocking solution, 5% nonfat dry milk in wash buffer (1.7 mM NaH2PO4, 8 mM Na2HPO4, 145 mM NaCl, 0.1% Tween 20), for 2 h at room temperature. The membrane was then incubated overnight in 2.5% nonfat dry milk in wash buffer containing a dilution of a primary antibody at 4°C, as indicated. The membrane was then washed three times in wash buffer for 30 min at room temperature. After washing, the membrane was incubated in a 1:2,000 dilution of a HRP-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG in a 2.5% nonfat dry milk blocking solution in PBS-wash buffer for 1.5 h at room temperature. Finally, the membrane was washed three more times in wash buffer. Protein bands were visualized using SuperSignal West Pico chemiluminescent substrate and developed on a Bio-Rad ChemiDoc Touch imaging system.

Filipin staining

Cells grown on glass cover slips were rinsed three times with PBS and then fixed for 10 min at room temperature with 3.7% formaldehyde in PBS. Then the cells were rinsed twice with PBS and once with “medium 1” [150 mM NaCl, 5 mM KCl, 1 mM CaCl2, 20 mM HEPES (pH 7.4), and 2 mg/ml glucose]. The cells were then stained for 2 h at room temperature in the dark with filipin at 50 μg/ml dissolved in medium 1 buffer. Finally, the cells were washed three times for 5 min with medium 1 buffer and mounted on slides. For filipin visualization, we used a Ti-U inverted fluorescent microscope with a UV-2A neutral density filter to slow down photobleaching. In addition to slow down photobleaching, the UV-2A filter also provides a more linear dynamic range of the filipin complexes’ fluorescence than the UV-2B or DAPI filters. To focus and determine the exposition time, we used a different field of cells within the sample than the ones to be photographed to avoid photobleaching of the cells.

BODIPY staining

Cells grown on glass cover slips were washed twice with PBS and then fixed for 10 min at room temperature with 3.7% formaldehyde in PBS. Then, they were rinsed twice with PBS and permeabilized for 3 min at room temperature in 0.05% saponin in PBS. The samples were then rinsed three times with PBS and stained for 2 h at room temperature in the dark with BODIPY 493/503 at 20 μg/ml in PBS. Finally, the samples were washed three times for 10 min in PBS and mounted on slides for visualization on a fluorescent microscope using a FITC filter.

Quantification of accessible PM cholesterol

Recombinant ALOD4 was purified from Escherichia coli expressing ALOD4 from a bacterial expression plasmid encoding ALOD4 with two point mutations (S404C and C472A) and a His tag at the aminus terminus (pRSETB-ALOD4), a gift from Dr. Arun Radhakrishnan (University of Texas Southwestern) as described (32). Purified ALOD4 was labeled with Alexa Fluor 488 C5-maleimide and used to quantify accessible PM free cholesterol in macrophages and CHO cells through fluorescence activated cell sorting (FACS) analysis, also as described (32), with minor modifications as described in the figure legends. Briefly, cells were harvested by scraping them (macrophages) or with 0.25% trypsin or Accutase cocktail (eBioscience) for 5 min (hepatocytes and CHO cells) and suspended in K-free PBS with 1 mM EDTA and 2% LPDS at a concentration of 106 cells per milliliter, and suspended in K-free PBS with 1 mM EDTA and 2% LPDS at a concentration of 106 cells per milliliter. Half a million cells were incubated by rotating with the indicated amounts of fluorescence anthrolysin O domain 4 (fALOD4) for 3 h at 4°C in darkness. The fluorescently labeled cells were washed with PBS, spun down for 2.5 min at 2,500 g, and suspended in K-free PBS for flow cytometry (FACS) analysis using a BD LSRFortessa-X2 flow cytometer at the VCU Massey Cancer Center Flow Cytometry. A total of 10,000 cells were analyzed for each condition. Flow cytometry data analysis was done using FACSDIVA software (BD Sciences, San Jose, CA) for acquisition and analysis. Median fluorescent intensity was used to quantify fALOD4 binding per cell.

ACAT activity assay

ACAT activity was determined in the microsomal fraction of macrophages or livers from WT and StarD5−/− mice as previously described (25). [14C]oleoyl-CoA was added to the reactions, incubated for 4 min, and stopped by adding methanol/chloroform (2:1, v/v). After phases were separated, the chloroform phase was dried under nitrogen and the precipitate resuspended in acetone. The reaction products were separated by thin-layer chromatography in a mobile phase of hexane/ethyl acetate (9:1, v/v). Bands corresponding to cholesteryl esters were scraped and counted in a scintillation counter to determine ACAT activity. Units correspond to the picomoles of cholesteryl esters formed per milligram of microsomal protein per minute.

mRNA quantification

WT and StarD5−/− mice, fed a chow laboratory diet, were euthanized, livers were harvested, and RNA was extracted with a RNeasy Plus Mini Kit and quantified on a Nanodrop spectrophotometer. qRT-PCR was run with the Brilliant III Ultra-Fast QRT-PCR Master Mix kit. Relative mRNA expression was determined for StarD5, HMG-CoA reductase, ABCA1, NPC1, with Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH), or actin, used as a control.

Cholesterol efflux assay

Peritoneal macrophages from WT and StarD5−/− mice were plated in 24-well plates at 2 × 105 cells per well. The following day, the cells were cholesterol-loaded for 2 days at 37°C with medium containing 1% FBS containing 1 μCi/ml [3H]cholesterol and 50 μg/ml acLDL. The cells were then equilibrated for 24 h at 37°C in serum-free medium with or without 10 μM cAMP and 0.3 mM cyclosporin A. Finally, efflux was performed in medium with or without cyclic-AMP and cyclosporine A with 25 μg/ml ApoA1 as acceptor. Medium was collected after 4 h. At the end of the efflux, cells were harvested in 1 M NaOH. Radioactivity in medium and cells (50 μl) was quantified in a scintillation counter. The percentage of cholesterol efflux was calculated as 100 × (medium dpm)/(medium dpm + cell dpm). The y axis represents changes in effluxed cholesterol compared with WT control.

Cholesterol transport assay

An in vitro cholesterol transport assay was carried out between PC liposomes as described by Horenkamp et al. (33). Briefly, acceptor liposomes (LA, unilamellar) were prepared drying egg PC under nitrogen gas. The lipid was hydrated at 1 mM final concentration at 37°C in 50 mM HEPES (pH 7.2) and 120 mM K-acetate, freeze/thawed five times with liquid nitrogen, and extruded through polycarbonate filters (100 nm pore) using a Thermobarrel extruder from Lipex™. Donor liposomes (LD, multilamellar) were prepared similarly but using 95% mol% egg PC and 5 mol% cholesterol, and 2 μCi/ml 3H-cholesterol. The buffer used to make the LD “heavy” contained 0.75 M sucrose and they were not extruded. LA, LD, and the protein to be tested were mixed and incubated at 37°C for 1 h under rotation. Then, LA and LD liposomes were separated by centrifugation and the radioactivity in the pellet (P) and supernatant (S) was quantified by scintillation counting. The percentage of total cholesterol transfer was calculated by the formula: % cholesterol transfer = 100 × (S)/(S + P) – 100 × (S0)/(S0 + P0), where S0 and P0 were the radioactivity measured in the pellet and in the supernatant in the absence of protein. The recombinant GST-human StarD5 and GST proteins were prepared as previously described (25).

Fluorescence lifetime imaging microscopy

We used a final 1 μM solution of LAURDAN for the experiments of fluidity and/or dipolar relaxation (34). Cells were incubated with LAURDAN for 30 min at 37°C. Fluorescence lifetime imaging microscopy (FLIM) was acquired using a Zeiss LSM880 laser scanning microscope (Carl Zeiss, Dublin, CA-USA). The instrument was equipped with a Ti:Sapphire laser (Spectra-Physics), producing 80 fs pulses at a repetition rate of 80 MHz. An ISS A320 FastFLIM box (ISS) was used to collect the lifetime decay data. Images were acquired using a 40× water immersion objective 1.2 numerical aperture (Carl Zeiss). LAURDAN was excited using 780 nm wavelength. In the excitation path, a λ/4 plate was included to avoid photoselection effect. For the detection, two high efficiency GaAsP Hybrid Detectors (HPM-100-40, Becker and Hickl GmbH) were used, and before the detector a filter cube composed of two bandpass filters (440/60 nm and 500/60 nm) and a 470 nm dichroic mirror from Semrock were employed. Image acquisition was performed with a pixel frame size of 256 × 256 and a pixel dwell time of 16.38 μs/pixel. FLIM data was processed using SimFCS software developed at the Laboratory for Fluorescence Dynamics (www.lfd.uci.edu). Calibration of the lifetime measurements was performed using a 100 nM solution of Coumarin 6, we use a reference lifetime of 2.5 ns (www.iss.com).

FLIM phasor plot analysis

The phasor plot was obtained following equations 1 and 2, as previously described (35, 36). Briefly, the fluorescence decay I(t) was acquired at each pixel of an image and then the G and S coordinates were calculated. The G and S coordinate for each pixel was plotted in a polar plot (referred to as phasor plot or phasor space) as follows:

| (Eq. 1) |

| (Eq. 2) |

where ω is the angular modulation frequency (equal to 2πf, and f is the repetition frequency of the laser) and T is the period of the laser frequency. Phasors follow rules of vector addition, orthogonality, and reciprocity, i.e., pixels that contain a linear combination of two independent fluorescent species will appear in the line joining the two independent emissions in the phasor plot. An illustration and extended explanation can be found in supplemental Fig. S2. A hand drawn masking was used for the isolation of the PM-related areas (supplemental Fig. S3) (35).

Data reproducibility and statistics

Data are shown as mean ± SD and were analyzed using the ANOVA and Tukey posttest, or a significant experiment is shown of three or more with similar results. The experiments based on images were performed by three independent biological replicates, and for each replicate more than 20 images were acquired in order to perform the statistical analysis. All the samples showed normal distributions as judged by the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical analysis was performed using Microsoft Office Excel or Prism 5 software (GraphPad Inc.).

RESULTS

StarD5 deletion reduces PM cholesterol and cholesterol efflux, and triggers lipid accumulation

To generate a line of StarD5−/− mice, a CRISPR/Cas9 strategy (26, 37, 38) was employed to introduce a 1 bp deletion immediately after the ATG translation start site, creating a translational frame-shift that was expected to generate a null allele. Additional sequence changes were introduced immediately preceding the ATG to optimize the Kozak sequence, ensuring that all translation would initiate at this ATG sequence, and not at a downstream ATG that might allow for production of a truncated protein (supplemental Fig. S1A–D; see the Materials and Methods for a full description of creation of the mouse model). One line of mice carrying these mutations was generated, and upon mating of heterozygotes, homozygous offspring were generated in the expected numbers. Western blot analysis demonstrated the absence of StarD5 protein in tissues from homozygous KOs (supplemental Fig. S1E, F).

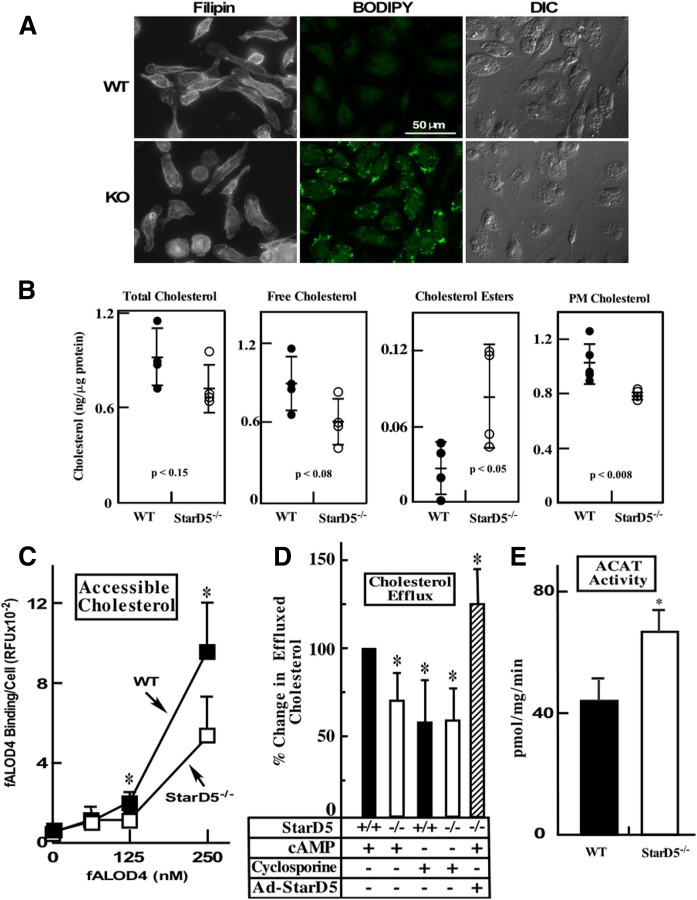

StarD5 is expressed at high levels in macrophages (22). To start characterizing the StarD5−/− mouse and to understand StarD5 function, we isolated primary peritoneal macrophages from both WT and StarD5−/− mice and stained them with filipin, which detects cellular free cholesterol, as well as with BODIPY 493/503, which detects neutral lipids. Figure 1A shows that, in StarD5−/− macrophages, PM cholesterol was significantly reduced. In contrast, neutral lipids, as observed by BODIPY 493/503 staining, were increased in StarD5−/− macrophages (Fig. 1A). Cholesterol quantification (Fig. 1B) shows that total cellular cholesterol did not significantly change, whereas cholesterol esters, which are found exclusively inside cells, were higher in StarD5−/− macrophages. Free cholesterol, which is located mostly in the PM (39, 40) showed a trend toward being lower in StarD5−/− macrophages. Cholesterol quantification in purified PM was significantly lower in StarD5−/− macrophages. To further characterize changes in PM cholesterol due to the lack of StarD5 protein, we quantified PM-accessible cholesterol in WT and StarD5−/− macrophages. PM cholesterol is believed to exist in three pools, i.e., accessible cholesterol, sphingomyelin-sequestered cholesterol, and essential or residual cholesterol (12). We used the bacterial cholesterol binding domain 4 of the Bacillus anthracis anthrolysin O (ALOD4) protein covalently conjugated to a fluorescent dye (Alexa Fluor 488) to quantify accessible PM cholesterol (12). Figure 1C shows that StarD5 deletion reduces accessible PM cholesterol as quantified using the bacterial cholesterol-binding protein (32). Thus, cholesterol quantification confirms the imaging studies.

Fig. 1.

StarD5 deletion lowers PM cholesterol in macrophages and ABCA1-dependent cholesterol efflux. A: Primary peritoneal macrophages from WT and StarD5−/− mice were imaged following staining with filipin and BODIPY 493-503, as indicated, as well as by differential interference contrast for those stained with BODIPY 493-503. B: Total, free, esterified, and PM cholesterol were quantified as described in the Materials and Methods (n = 4). C: Accessible PM cholesterol was quantified as described in the Materials and Methods (n = 3, *P ≤ 0.05 for WT versus StarD5−/−). D: Primary peritoneal macrophages from WT and StarD5−/− mice were used in cholesterol efflux assays as described in the Materials and Methods in the absence or presence of cAMP or cyclosporine A. Cholesterol efflux was calculated as the percentage of total cell 3H-cholesterol content, which was about 5% of the total cholesterol (total effluxed 3H-cholesterol + cell-associated 3H-cholesterol) and represented as a percentage of the effluxed cholesterol in WT macrophages in the presence of cAMP. Primary peritoneal macrophages from StarD5−/− mice infected with Ad-StarD5 (MOI of 200) were also used. The values represent the average ± SD (n = 4, *P < 0.05 with respect to the WT control). There was no significant difference in cholesterol effluxed from WT macrophages compared with StarD5−/− macrophages in the presence of cyclosporine A. E: Microsomes were prepared from WT and StarD5−/− macrophages (108 per condition) and ACAT activity was quantified as described in the Materials and Methods (n = 3, P < 0.05).

To assess whether lack of StarD5 affects cholesterol efflux, we quantified cholesterol efflux through the ABCA1 pathway, using a standard assay (41). Primary peritoneal macrophages from WT and StarD5−/− mice loaded with 3H-cholesterol were used to measure rates of cholesterol efflux. Cells were incubated in the absence and presence of cAMP, an activator of ABCA1 expression (41), or cyclosporine A, an inhibitor of ABCA1-mediated cholesterol efflux (42), as indicated (Fig. 1D). Then medium was changed to serum-free medium containing 25 μg/ml apoA1 as a cholesterol acceptor. Figure 1D shows that StarD5−/− macrophages efflux cholesterol through the ABCA1 pathway at significantly lower rates than WT cells. When macrophages were incubated with the ABCA1 inhibitor, cyclosporine A, there was no difference in cholesterol efflux between WT or StarD5−/− macrophages (Fig. 1D). To further test the role of StarD5 in cholesterol efflux, we overexpressed StarD5 in StarD5−/− peritoneal macrophages using an adenovirus vector encoding the human StarD5 cDNA driven by the cytomegalovirus promoter tagged with the Flag sequence (Ad-StarD5) and then quantified ABCA1-dependent cholesterol efflux. Figure 1D also shows that StarD5 overexpression increased cholesterol efflux. Because sterols are allosteric ACAT activators (43), we quantified ACAT activity in macrophages from StarD5−/− and WT mice. Figure 1E shows that StarD5−/− macrophages have higher ACAT activity.

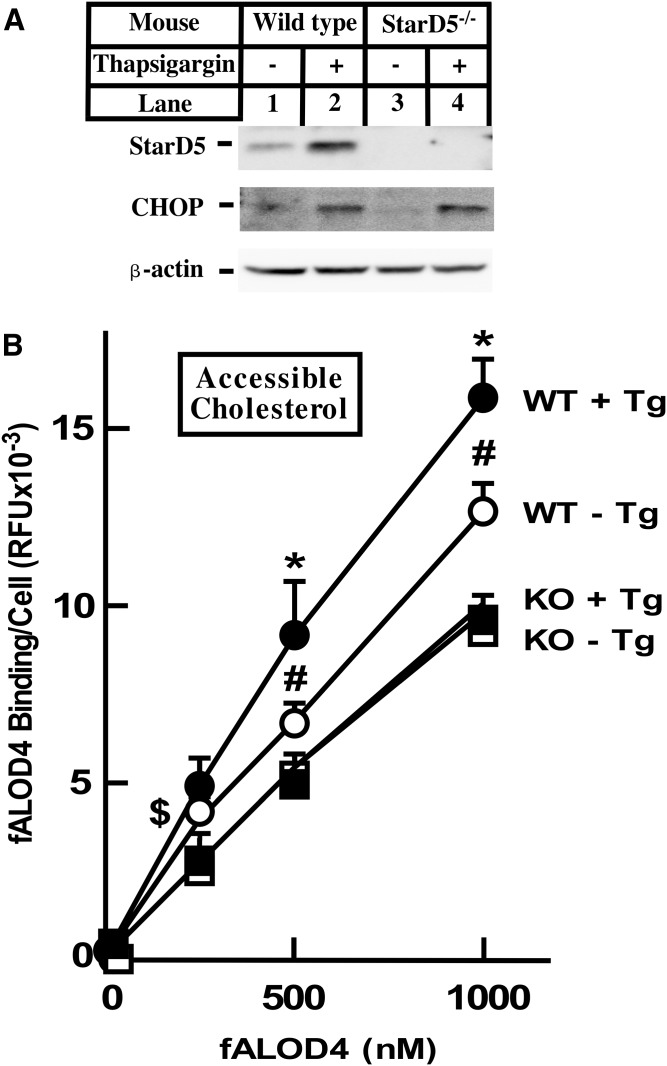

StarD5 is expressed at high levels in macrophages. However, ER stress activates StarD5 expression in all cells tested (19, 20). To characterize whether the increase in StarD5 expression upon ER stress results in an increase in PM cholesterol, we isolated primary hepatocytes from WT and StarD5−/− mice and incubated them with thapsigargin (Tg), a known ER stressor. Figure 2A shows that ER stress increases StarD5 expression in mouse hepatocytes, which results in an increase in accessible PM cholesterol in WT but not in StarD5−/− hepatocytes (Fig. 2B). As expected, CHOP protein, was increased by Tg in both WT and StarD5−/− hepatocytes.

Fig. 2.

ER stress increases accessible PM cholesterol in WT mouse hepatocytes. Primary hepatocytes were isolated from WT and StarD5−/− mice as indicated in the Materials and Methods and incubated in 10% FBS-containing medium for 48 h. Then, the cells were incubated in the presence of 2 μM Tg or vehicle for 4 h, as indicated. A: A portion of the cells were used to extract total cellular protein and used in Western blots to quantify StarD5, CHOP, and β-actin. B: Accessible PM cholesterol was quantified as described in the Materials and Methods (n = 4, *P < 0.05 FOR WT + Tg/WT − Tg; #P < 0.005 for WT − Tg/KO − Tg; $P < 0.05 for WT − Tg/KO − Tg).

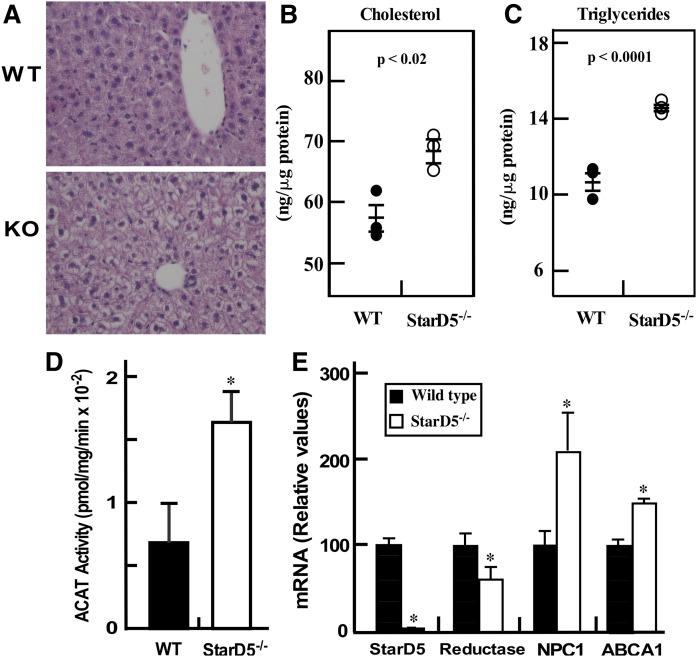

In mammals, the liver is a key organ in handling cholesterol and other lipids. To characterize a potential phenotype due to the lack of StarD5, we studied cholesterol and lipid content in the livers of StarD5−/− mice compared with WT mice. Figure 3A shows that StarD5−/− livers have higher lipid content based on H&E staining. Both cholesterol and triglycerides are increased in StarD5−/− livers (Fig. 3B, C). As in isolated macrophages, the increase in liver cholesterol in StarD5−/− mice results in an increase in ACAT activity (Fig. 3D). Alteration of cellular cholesterol should lead to changes in the expression of genes involved in cholesterol synthesis and transport. Figure 3E shows that HMG-CoA reductase mRNA was decreased by about 40% in StarD5−/−. NPC1 and ABCA1 were increased 2-fold and 40%, respectively. The changes in lipid content are likely the result of higher levels of intracellular cholesterol being converted to oxysterols that activate the nuclear receptor, LXR, known to suppress HMG-CoA reductase transcription and activate NPC1 (44, 45), ABCA1 (41), fatty acid synthesis, and acetyl-CoA carboxylase (46).

Fig. 3.

StarD5 deletion increases liver lipid content. A: Formalin-fixed sections from WT and StarD5−/− mouse livers were stained with H&E and visualized with a 40× objective using a Nikon Ti-U inverted microscope. Representative images from three mice are shown. (B and C) Liver total cholesterol (B) and triglycerides (C) were quantified as described in the Materials and Methods (n = 3). (D) Microsomes were prepared from WT and StarD5−/− livers and ACAT activity was quantified as described in the Materials and Methods (n = 3, P < 0.05). E: Total RNA was extracted from WT and StarD5−/− mouse livers and used in qRT-PCR as described in the Materials and Methods section, n = 3, *P < 0.05, WT compared with StarD5−/−.

StarD5 overexpression increases accessible PM cholesterol

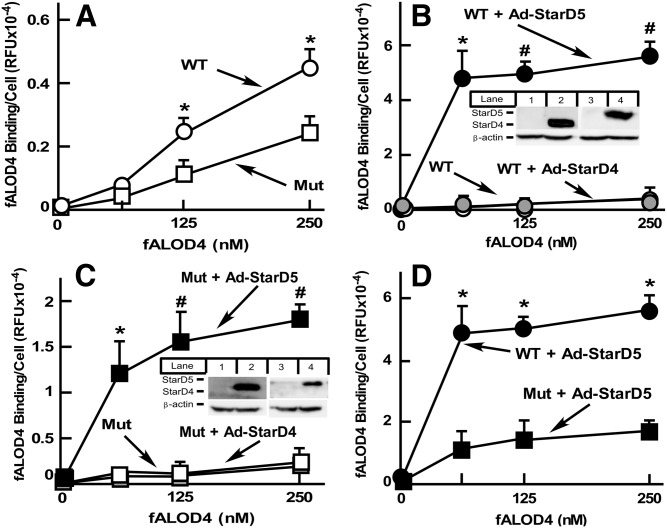

To further characterize the role of StarD5 in intracellular cholesterol distribution, we used CHO cells because of their extensive use in cholesterol metabolism studies and the availability of a variety of mutants altering cholesterol metabolism (12, 47). We overexpressed StarD5 using the adenovirus vector, Ad-StarD5, described in Fig. 1D. We used a high MOI to maximize the effect of StarD5 on PM cholesterol. We used CHO WT and a CHO NPC1-null mutant 10-3, known to have less PM cholesterol than WT CHO cells (23). As expected, as a function of cholesterol being retained within the late endosomes (23), CHO 10-3 mutant cells have less accessible PM cholesterol than CHO WT cells (Fig. 4A). Overexpression of StarD5, but not overexpression of StarD4, a protein which is homologous to StarD5, dramatically increased PM cholesterol both in CHO WT cells and 10-3 mutants (Fig. 4B, C). Interestingly, StarD5 overexpression in WT cells had about 5-fold more cholesterol than when NPC1 10-3 mutant cells were used (Fig. 4D), suggesting that the lower ER cholesterol content found in NPC1 10-3 mutant cells, as a function of their endosomal cholesterol retention, decreases cholesterol available for StarD5 transfer to the PM.

Fig. 4.

StarD5 overexpression results in higher accessible PM cholesterol in CHO cells. A: WT CHO and NPC1 10-3 mutant cells, grown in 10% FBS-containing F12 medium. Accessible PM cholesterol was quantified as described in the Materials and Methods (n = 3, *P < 0.005, WT cells versus NPC1 mutant cells). B: WT CHO cells, noninfected or infected with the indicated virus (3,000 MOI), were harvested, incubated with fALOD4, and fluorescent intensity was quantified as in A (n = 3, *P < 0.005, #P < 0.00005 WT cells infected with Ad-StarD5 versus noninfected or infected with Ad-StarD4). A portion of the cells were used to extract total cellular protein and quantify either StarD4 (lanes 1 and 2) or StarD5 (lanes 3 and 4) by Western blots to assess protein expression (insert). C: CHO NPC1 mutant 10-3 cells were used instead of WT CHO cells, as in B (n = 3, *P < 0.005, #P < 0.0005 NPC1 mutant cells infected with Ad-StarD5 versus WT noninfected or infected with Ad-StarD4). (D) Data from the StarD5-infected cells from B and C is plotted together to show the different response to StarD5 overexpression in accessible PM cholesterol of CHO WT versus NPC1 mutant 10-3 cells (n = 3, *P < 0.0005, WT cells versus NPC1 mutant cells infected with Ad-StarD5).

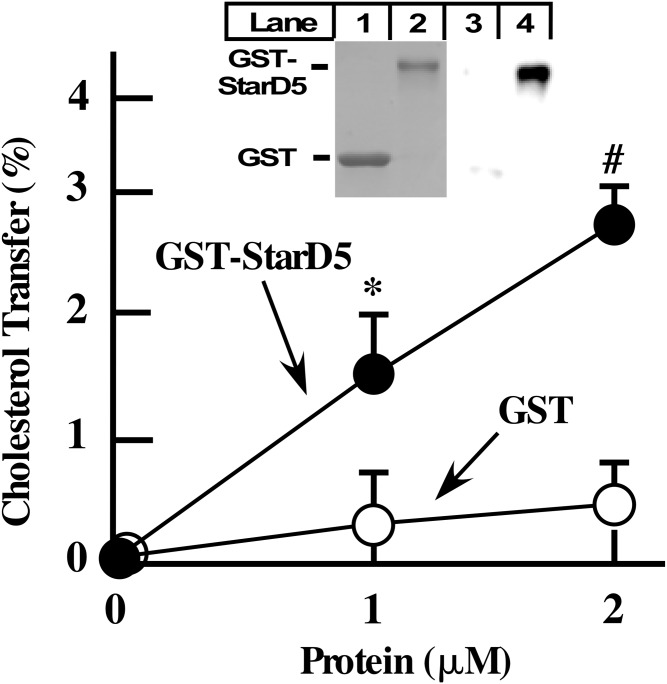

StarD5 transfers cholesterol between liposomes

The studies described above demonstrate that StarD5 increases PM cholesterol and diminishes intracellular cholesterol by yet unknown mechanisms. To characterize whether StarD5 is capable of transferring cholesterol between membranes, we used an in vitro system where StarD5 is the only protein in the system. Figure 5 shows that a recombinant GST-StarD5 protein is capable and sufficient to transfer cholesterol between liposomes.

Fig. 5.

StarD5 transfers cholesterol between membranes. Recombinant GST-human StarD5 protein (GST-StarD5) and GST as control were used in an in vitro cholesterol transfer assay between acceptor and donor liposomes as explained in the Materials and Methods (n = 3, *P < 0.05, P < 0.005 for GST-StarD5 versus GST at the indicated protein concentration). The insert shows the two proteins used in the assay visualized by Coomassie blue staining (lanes 1 and 2) and by Western blotting (lanes 3 and 4) using an anti-StarD5 antibody.

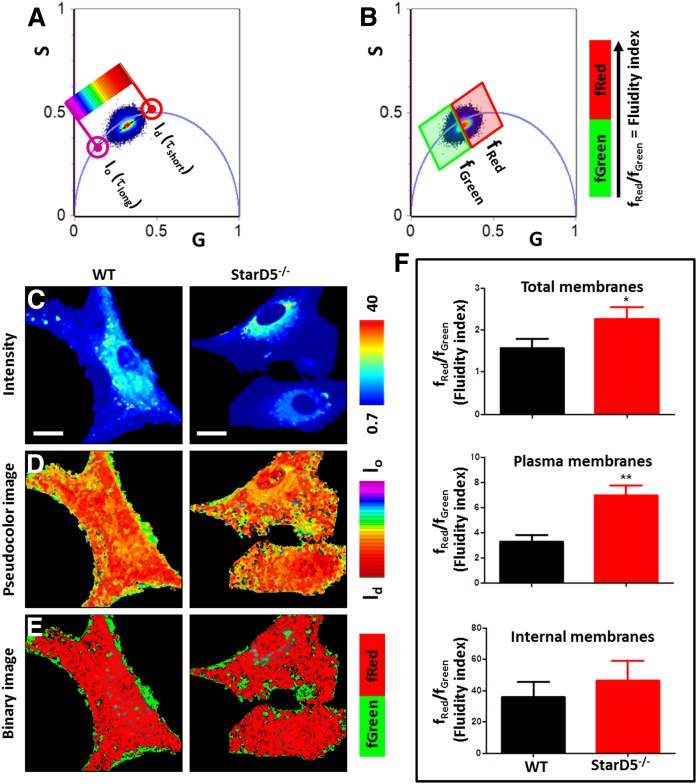

StarD5 deletion alters the physical properties of PMs

Based on the above studies, the cholesterol distribution in the StarD5−/− macrophages should modify all membrane dynamics, both internal and of the PM. To determine whether the reduced PM cholesterol in StarD5−/− macrophages alters its physical properties, we used fluorescence lifetime imaging microscopy (FLIM) and phasor analysis of LAURDAN fluorescence of subcellular regions of interest by a masking procedure (35) (supplemental Figs. S3, S4). LAURDAN spectroscopic properties are affected by the physical properties of cellular membranes and the amount of cholesterol in a membrane can be quantified in two complementary ways by a combination of emission filters (48). In the so called “blue filter,” we can measure the amount of lo and ld phase in a membrane, which is affected by the amount of cholesterol (more cholesterol results in more lo phase). Cholesterol also affects the rate of dipolar relaxation in a membrane and this signal is detected in the “green filter” (more cholesterol results in an increase in dipolar relaxations) (48, 49). Given the focus of this work in detecting the spatial and temporal distribution of cholesterol, we opted to use both methods to unequivocally assign the spectroscopic changes to cholesterol concentration. To discriminate between the effects of the StarD5−/− on the polarity and/or dipolar relaxation sensed by LAURDAN, we collected lifetime images using two bandpass filters (blue and green, 440/60 nm and 500/60 nm, respectively). The phasor plot in the blue channel shows a cluster of pixels for the LAURDAN in cells located in the line of linear combinations with different fraction of ld and lo environments (short and long lifetimes, respectively). Figure 6 shows that StarD5−/− macrophages have fewer pixels of lo membranes. By using a continuous color scheme related to the phasor position along the linear combination line (Fig. 6A, D), it was possible to visualize that the PM has more lo membranes in the WT macrophages compared with the StarD5−/− macrophages. We also performed a binary analysis (lo or ld membranes, green or red pixels, respectively) of the pixel fractions from the phasor plot (Fig. 6B, E). The quantitative analysis for the number of pixels at each cursor (Fig. 6B) was used to construct the ratio fRed/fGreen (= ld/lo that we call fluidity index), showing a significant increase of ld in the StarD5−/− macrophages. To specifically select the PM, we masked the images using the same procedure described before (35). The masking analysis of same data indicated that the main change in the fluidity index change was identified in the PM (Fig. 6F).

Fig. 6.

Phasor-FLIM of LAURDAN fluorescence in WT and StarD5−/−macrophages for blue-channel. A: Phasor distribution of LAURDAN fluorescence for WT and StarD5−/− macrophages. Red and purple cursors identify the trajectory for LAURDAN in cell membranes. The red cursor represents ld membranes (τshort = short lifetime) and the purple cursor represents lo membranes (τlong = long lifetime). Using a continuum cursor design the cells were masked based on their fluidity or the lo/ld ratio (D). B: Binary cursor selection for the fractional analysis of panel F. C: Representative intensity fluorescence images of WT and StarD5−/− macrophages. The bar at the left represents the intensity scale in counts. D: Pseudocolor images produced by the cursor code selection of panel A. The bar at the left represents the color scale used for the masking along the lo/ld ratio trajectory. E: Binary images produced by the cursor code selection in B. The bar at the left represents the color scale used for the binary masking. F: Analysis of number of pixels fraction for total, plasma, or internal membranes, respectively. The separation of plasma and internal membranes was done using masks. In the ratio analysis, we used more than 20 cells by group. *P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01, for WT versus StarD5−/−. Bars represent 20 μm.

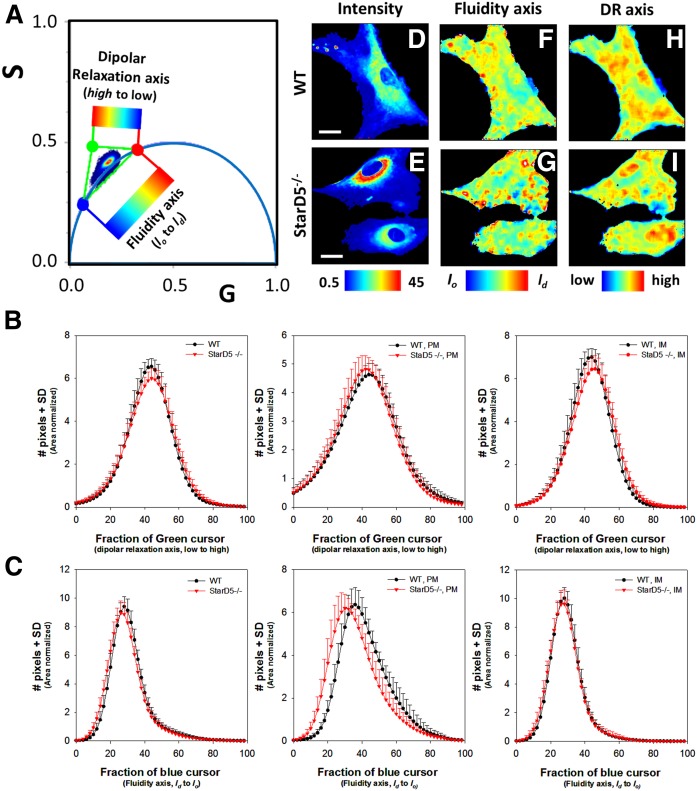

The phasor distributions for LAURDAN in WT and StarD5−/− macrophages using the green channel are shown in Fig. 7A. Similarly to what was done for the blue channel data, we positioned three cursors at the extremes of the phasor trajectory. As Ranjit et al. (50) describe, we calculated the histogram for the pixel distribution along the line of linear combination of LAURDAN in StarD5−/− macrophages. By the three-cursor analysis, we are able to discriminate between fraction of lo/ld (fluidity axis) and dipolar relaxation around the LAURDAN (dipolar relaxation axis), Fig. 7A.

Fig. 7.

Phasor-FLIM of LAURDAN fluorescence in WT and StarD5−/− macrophages for green-channel. A: Three cursors fraction histogram analysis on the phasor distribution for the green channel. The analysis calculates an area normalized number of pixels in the phasor distribution between red-green and red-blue cursors. We define the trajectory between red-green points as the dipolar relaxation axis and from red-blue points as the fluidity axis. The images can be colored by using the scale shown. The values for the G and S coordinates were calculated as detailed in the Materials and Methods section. B: Histograms of the pixel fraction distribution along the red-green trajectory for total membrane, PM, and internal membrane (IM), respectively, from left to right. C: Histogram of the pixel fraction distribution along the red-blue trajectory for total membrane, PM, and internal membrane (IM), respectively. D, E: Representative intensity fluorescence images of WT (D) and StarD5−/− (E) macrophages. The bar at the bottom represents the intensity scale in counts. F, G: Pseudocolor images produced by the cursor selection between red-green cursors (fluidity axis). The bar at the bottom represents the color scale used for the pseudo-coloring between the lo/ld trajectory. H, I: Pseudocolor images produced by the cursor selection between red-blue cursors (dipolar relaxation axis). The bar at the bottom represents the color scale used for the pseudo-coloring between low and high dipolar relaxation trajectory. The separation of plasma and internal membranes was done using masks. In the trajectory analysis, we used more than 20 cells by group. Bars represent 20 μm.

Using the histograms of the pixels along the dipolar relaxation axis, we could not identify a significant difference in the dipolar relaxation axis of the LAURDAN between the WT and StarD5−/− macrophages (green channel, Fig. 7A, along the DR axis the histograms are similar). Instead, the analysis of the data in the green channel for the fluidity axis confirms the increase in fluidity (lo fraction is decreasing in Fig. 5C, for the histogram of the PM panel) in the StarD5−/− macrophage PMs. Figure 7D–I shows representative images for the LAURDAN intensity and the fluidity and dipolar relaxation axis, respectively, in WT and Star D5−/− macrophages.

DISCUSSION

How cholesterol is redistributed within the cell has not been clearly elucidated. The intracellular transport of cholesterol is important for the regulation of uptake, efflux, and synthesis of cholesterol, and is necessary to maintain the fluidity and integrity of the various cellular membranes. From the ER, cholesterol moves to the PM against a cholesterol concentration gradient (2). While intracellular cholesterol transport is in part mediated by vesicles, nonvesicular mechanisms represent a large portion of cholesterol transport and are poorly understood (51). In the present study, we used loss- and gain-of-function approaches to study the biological and physiological function of StarD5 and its role in maintaining PM content and cholesterol homeostasis.

Among the best understood proteins that play a role in intracellular cholesterol transport is NPC1. NPC1 is a membrane bound protein found in the late endosomes. It has been proposed that NPC1 mediates the exit of LDL-derived cholesterol from lysosomes to the ER (23, 52), although recent studies suggest that NPC1 mediates the exit of cholesterol from the lysosomes to the PM (3, 12). Other proteins believed to be involved in intracellular cholesterol transport are StarD4, which has been shown to facilitate the movement of ER cholesterol to ACAT (24, 53), and OSBP, which drives cholesterol exchange at contact sites between the ER and the trans-Golgi network (54). ORP2 delivers cholesterol to the PM in exchange for phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate [PI(4,5)P2] (55). In the present study, we show evidence that StarD5, a member of the START family of proteins (56), regulates PM and intracellular cholesterol. This evidence is supported by the changes in liver lipid content and in the physical order parameter observed at the PM in StarD5−/− macrophages. The fluidity of the membrane can be defined by the order parameters of the phospholipids, and cholesterol is a key factor to modulate the order parameters, and thereby, the fluidity (48). The FLIM-phasor approach for LAURDAN fluorescence (35) shows spatial effects on the membrane fluidity for the StarD5−/− macrophages, and allowed us to quantitatively evaluate in space and time cholesterol redistribution in StarD5−/− cell membranes using the fluidity index changes.

The fact that the fluorescent probe, LAURDAN, is ubiquitously distributed in the cell and has a lack of segregation for specific phases is one of the major advantages of LAURDAN over other membrane probes and LAURDAN variants. This property is exploited in the literature to obtain information related to the dipolar relaxation, as well as the polarity at the interphase of the membranes (35, 57–60). The use of masking of different membranes is mandatory in our in cellulo experiments to uniquely determine the subcellular location of LAURDAN (35). We applied PM masks to discriminate between the intracellular membrane and the PM-related subregions.

Using this approach, we were able to define an index of fluidity related to the ratio of the number of pixels with ld/lo membranes (short or long lifetime). We concluded that knocking-out StarD5 in macrophages produces a significant reduction of the lo pixels. Taken together, these results with the biochemical effects of StarD5−/− support the physicochemical modification of the PM interphase by the reduction in the PM cholesterol content in the StarD5−/− macrophages. Our studies are in line with the report of Ito et al. (61), where they link the PM organization and composition with the role of ABCA1 as a sterol transporter. In the same logic, our studies support a connection between PM cholesterol controlled by a protein and the physical reorganization of the PM.

Cholesterol binding proteins, including START domain proteins, have been demonstrated to control the transport of cholesterol from the ER to other cellular organelles. For example, the sterol binding protein, OSBP, has been shown to act at ER-trans Golgi membrane contact sites. The START domain protein, StarD1, has been shown to promote the transport of cholesterol to the mitochondria for synthesis of steroid hormones, possibly acting at ER-mitochondria contact sites (62). How StarD5 functions to control PM and intracellular cholesterol is not fully clear from the studies presented here. A recent publication suggests that StarD5 transfers cholesterol to the ER (63). However, our studies do not support that idea. Whereas our studies show that StarD5 regulates PM cholesterol content, they cannot differentiate whether StarD5 transfers cholesterol to the PM or inhibits its movement from the PM by perhaps holding it in place, the gain- and loss-of-function studies shown here are in conflict with the idea that StarD5 transfers cholesterol to the ER. Additionally, the ability of StarD5 to transfer cholesterol between liposomes shown in our studies, the fact that other members of the START family of proteins, such as StarD1 (17, 62), StarD3 (18), StarD4 (51), and StarD6 (15), transfer cholesterol intracellularly, and the lack of a membrane spanning domain in the StarD5 protein strongly suggest that StarD5 functions by transferring cholesterol to the PM rather than holding it in place.

Interestingly, the inability of StarD4 overexpression to increase PM cholesterol, as StarD5 overexpression does, suggests that StarD4 does not mobilize cholesterol to the PM, at variance with a recently reported study (51). The studies showing that StarD4 lies near to ACAT (64) and that it appears to be rate-determining in the transfer of cholesterol for its esterification (25), suggest StarD4 to be more a cholesterol facilitator between membranes along the lines of the recently proposed transfer of cholesterol by OSBPs (55, 65).

There is some controversy in the literature regarding StarD5 ligands, as well as the cell types in which StarD5 is expressed. Two publications from the same laboratory (66, 67) claimed that StarD5 binds bile acids and put in doubt its cholesterol binding capabilities. Our laboratory has failed to demonstrate bile acid binding to StarD5. Most importantly, several publications from our laboratory and other laboratories have shown the ability of StarD5 to bind cholesterol (16, 19–22, 56, 68). The ability of StarD5 to transfer cholesterol between membranes shown in this study, adds further support to the notion that StarD5 binds cholesterol. Yet as with the studies showing bile acid binding, StarD5 binds 25-hydroxycholesterol at much lower affinity than cholesterol, which of uncertain. Thus, perhaps StarD5 is able to bind bile acids in vitro. However, it is unlikely that bile acids binding to StarD5 have any significant physiological role in nonhepatic cells.

Our study has important physio-pathological implications, such as activation of cholesterol efflux, a major function of macrophages and hepatocytes. The ability of StarD5 to respond to ER stress (19) by regulating PM and intracellular cholesterol content, may allow the cell to survive the stress and reduce cell cholesterol/lipid content. More specifically, StarD5 appears able to potentiate the ABCA1-dependent cholesterol efflux pathway suggesting a possible role in preventing atherosclerosis. And, in hepatocytes, StarD5 also appears to lessen lipid accumulation; suggesting that the StarD5 level of expression could play an important role in fatty liver disease.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to Drs. Charles C. Schwartz, Philips B. Hylemon, Jerome F. Strauss, Sarah Spiegel, Timothy F. Osborne, and Helen H. Hobbs for discussions and critical comments, to Dr. Laura Liscum for providing the CHO 10-3 mutant cell line, and to Dr. Arun Radhakrishnan for providing plasmid pRSETB-ALOD4 and advice to overexpress the ALOD4 protein. Dalila Marquez and Patsy Cooper provided excellent technical assistance.

Footnotes

Abbreviations:

- CHOP

- CCAAT-enhancer-binding protein homologous

- FACS

- fluorescence activated cell sorting

- fALOD4

- fluorescence anthrolysin O domain 4

- FLIM

- fluorescence lifetime imaging microscopy

- LAURDAN

- 6-dodecanoyl-2-dimethylaminonaphthalene

- MOI

- multiplicity of infection

- NPC

- Niemann-Pick C

- OSBP

- oxysterol-binding protein

- PM

- plasma membrane

- PNS

- post-nuclear supernatant

- qRT-PCR

- quantitative RT-PCR

- ssODN

- single-stranded oligodeoxynucleotide

- StarD

- steroidogenic acute regulatory-related lipid transfer domain

- START

- steroidogenic acute regulatory protein-related lipid transfer

- Tg

- thapsigargin

- VCU

- Virginia Commonwealth University

This work was supported by Health Services Research and Development Grant I01 BX000197-07 (to W.M.P.), an award from Virginia Commonwealth University (VCU) Center for Clinical and Translational Research (CTSA) (National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences Grant UL1TR000058) and the CCTR Endowment Fund of VCU (to G.G.), an award from the Ara Parseghian Medical Research Foundation (to G.G.), and National Institutes of Health Grants P41 GM103540 and P50 GM076516 (to E. G. Services). Products in support of this project were provided by the VCU Massey Cancer Center Transgenic/Knockout Mouse Shared Resource and the Flow Cytometry Shared Resource, supported in part with funding from National Cancer Institute Grant P30 CA016059. L.M. is supported by the Universidad de la República-Uruguay as a full-time professor. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

The online version of this article (available at http://www.jlr.org) contains a supplement.

REFERENCES

- 1.Brown M. S., and Goldstein J. L.. 1986. A receptor-mediated pathway for cholesterol homeostasis. Science. 232: 34–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jacobs N. L., Andemariam B., Underwood K. W., Panchalingam K., Sternberg D., Kielian M., and Liscum L.. 1997. Analysis of a Chinese hamster ovary cell mutant with defective mobilization of cholesterol from the plasma membrane to the endoplasmic reticulum. J. Lipid Res. 38: 1973–1987. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Infante R. E., and Radhakrishnan A.. 2017. Continuous transport of a small fraction of plasma membrane cholesterol to endoplasmic reticulum regulates total cellular cholesterol. eLife. 6: e25466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.DeGrella R. F., and Simoni R. D.. 1982. Intracellular transport of cholesterol to the plasma membrane. J. Biol. Chem. 257: 14256–14262. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Simons K., and Ikonen E.. 2000. How cells handle cholesterol. Science. 290: 1721–1726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gatta A. T., Wong L. H., Sere Y. Y., Calderon-Norena D. M., Cockcroft S., Menon A. K., and Levine T. P.. 2015. A new family of StART domain proteins at membrane contact sites has a role in ER-PM sterol transport. eLife. 4: e07253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bagatolli L. A., and Mouritsen O. G.. 2013. Is the fluid mosaic (and the accompanying raft hypothesis) a suitable model to describe fundamental features of biological membranes? What may be missing? Front. Plant Sci. 4: 457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ipsen J. H., Karlstrom G., Mouritsen O. G., Wennerstrom H., and Zuckermann M. J.. 1987. Phase equilibria in the phosphatidylcholine-cholesterol system. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 905: 162–172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lange Y., and Steck T. L.. 2016. Active membrane cholesterol as a physiological effector. Chem. Phys. Lipids. 199: 74–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Phillips M. C. 2014. Molecular mechanisms of cellular cholesterol efflux. J. Biol. Chem. 289: 24020–24029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.van Meer G., Voelker D. R., and Feigenson G. W.. 2008. Membrane lipids: where they are and how they behave. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 9: 112–124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Das A., Brown M. S., Anderson D. D., Goldstein J. L., and Radhakrishnan A.. 2014. Three pools of plasma membrane cholesterol and their relation to cholesterol homeostasis. eLife. 3: e02882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Infante R. E., Wang M. L., Radhakrishnan A., Kwon H. J., Brown M. S., and Goldstein J. L.. 2008. NPC2 facilitates bidirectional transfer of cholesterol between NPC1 and lipid bilayers, a step in cholesterol egress from lysosomes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 105: 15287–15292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mesmin B., and Antonny B.. 2016. The counterflow transport of sterols and PI4P. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1861: 940–951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Clark B. J. 2012. The mammalian START domain protein family in lipid transport in health and disease. J. Endocrinol. 212: 257–275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Soccio R. E., Adams R. M., Romanowski M. J., Sehayek E., Burley S. K., and Breslow J. L.. 2002. The cholesterol-regulated StarD4 gene encodes a StAR-related lipid transfer protein with two closely related homologues, StarD5 and StarD6. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 99: 6943–6948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Clark B. J., Wells J., King S. R., and Stocco D. M.. 1994. The purification, cloning, and expression of a novel luteinizing hormone-induced mitochondrial protein in MA-10 mouse Leydig tumor cells. Characterization of the steroidogenic acute regulatory protein (StAR). J. Biol. Chem. 269: 28314–28322. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wilhelm L. P., Wendling C., Vedie B., Kobayashi T., Chenard M. P., Tomasetto C., Drin G., and Alpy F.. 2017. STARD3 mediates endoplasmic reticulum-to-endosome cholesterol transport at membrane contact sites. EMBO J. 36: 1412–1433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rodriguez-Agudo D., Calderon-Dominguez M., Medina M. A., Ren S., Gil G., and Pandak W. M.. 2012. ER stress increases StarD5 expression by stabilizing its mRNA and leads to relocalization of its protein from the nucleus to the membranes. J. Lipid Res. 53: 2708–2715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Soccio R. E., Adams R. M., Maxwell K. N., and Breslow J. L.. 2005. Differential gene regulation of StarD4 and StarD5 cholesterol transfer proteins. Activation of StarD4 by sterol regulatory element-binding protein-2 and StarD5 by endoplasmic reticulum stress. J. Biol. Chem. 280: 19410–19418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rodriguez-Agudo D., Ren S., Hylemon P. B., Redford K., Natarajan R., Del Castillo A., Gil G., and Pandak W. M.. 2005. Human StarD5, a cytosolic StAR-related lipid binding protein. J. Lipid Res. 46: 1615–1623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rodriguez-Agudo D., Ren S., Hylemon P. B., Montanez R., Redford K., Natarajan R., Medina M. A., Gil G., and Pandak W. M.. 2006. Localization of StarD5 cholesterol binding protein. J. Lipid Res. 47: 1168–1175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Underwood K. W., Jacobs N. L., Howley A., and Liscum L.. 1998. Evidence for a cholesterol transport pathway from lysosomes to endoplasmic reticulum that is independent of the plasma membrane. J. Biol. Chem. 273: 4266–4274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rodriguez-Agudo D., Calderon-Dominguez M., Ren S., Marques D., Redford K., Medina-Torres M. A., Hylemon P., Gil G., and Pandak W. M.. 2011. Subcellular localization and regulation of StarD4 protein in macrophages and fibroblasts. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1811: 597–606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rodriguez-Agudo D., Ren S., Wong E., Marques D., Redford K., Gil G., Hylemon P., and Pandak W. M.. 2008. Intracellular cholesterol transporter StarD4 binds free cholesterol and increases cholesteryl ester formation. J. Lipid Res. 49: 1409–1419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Low B. E., Kutny P. M., and Wiles M. V.. 2016. Simple, efficient CRISPR-Cas9-mediated gene editing in mice: strategies and methods. Methods Mol. Biol. 1438: 19–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hsu P. D., Scott D. A., Weinstein J. A., Ran F. A., Konermann S., Agarwala V., Li Y., Fine E. J., Wu X., Shalem O., et al. . 2013. DNA targeting specificity of RNA-guided Cas9 nucleases. Nat. Biotechnol. 31: 827–832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Doench J. G., Hartenian E., Graham D. B., Tothova Z., Hegde M., Smith I., Sullender M., Ebert B. L., Xavier R. J., and Root D. E.. 2014. Rational design of highly active sgRNAs for CRISPR-Cas9-mediated gene inactivation. Nat. Biotechnol. 32: 1262–1267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pandak W. M., Ren S., Marques D., Hall E., Redford K., Mallonee D., Bohdan P., Heuman D. M., Gil G., and Hylemon P. B.. 2002. Transport of cholesterol into mitochondria is rate limiting for bile acid synthesis via the alternative pathway in primary rat hepatocytes. J. Biol. Chem. 277: 48158–48164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Xu Z., Tavares-Sanchez O. L., Li Q., Fernando J., Rodriguez C. M., Studer E. J., Pandak W. M., Hylemon P. B., and Gil G.. 2007. Activation of bile acid biosynthesis by the p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK): hepatocyte nuclear factor-4alpha phosphorylation by the p38 MAPK is required for cholesterol 7alpha-hydroxylase expression. J. Biol. Chem. 282: 24607–24614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Smart E. J., Ying Y. S., Mineo C., and Anderson R. G.. 1995. A detergent-free method for purifying caveolae membrane from tissue culture cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 92: 10104–10108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chakrabarti R. S., Ingham S. A., Kozlitina J., Gay A., Cohen J. C., Radhakrishnan A., and Hobbs H. H.. 2017. Variability of cholesterol accessibility in human red blood cells measured using a bacterial cholesterol-binding toxin. eLife. 6: e23355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Horenkamp F. A., Valverde D. P., Nunnari J., and Reinisch K. M.. 2018. Molecular basis for sterol transport by StART-like lipid transfer domains. EMBO J. 37: e98002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Malacrida L., Astrada S., Briva A., Bollati-Fogolin M., Gratton E., and Bagatolli L. A.. 2016. Spectral phasor analysis of LAURDAN fluorescence in live A549 lung cells to study the hydration and time evolution of intracellular lamellar body-like structures. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1858: 2625–2635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Malacrida L., Jameson D. M., and Gratton E.. 2017. A multidimensional phasor approach reveals LAURDAN photophysics in NIH-3T3 cell membranes. Sci. Rep. 7: 9215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ranjit S., Malacrida L., Jameson D. M., and Gratton E.. 2018. Fit-free analysis of fluorescence lifetime imaging data using the phasor approach. Nat. Protoc. 13: 1979–2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cong L., Ran F. A., Cox D., Lin S., Barretto R., Habib N., Hsu P. D., Wu X., Jiang W., Marraffini L. A., et al. . 2013. Multiplex genome engineering using CRISPR/Cas systems. Science. 339: 819–823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jinek M., Chylinski K., Fonfara I., Hauer M., Doudna J. A., and Charpentier E.. 2012. A programmable dual-RNA-guided DNA endonuclease in adaptive bacterial immunity. Science. 337: 816–821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lange Y. 1991. Disposition of intracellular cholesterol in human fibroblasts. J. Lipid Res. 32: 329–339. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lange Y., and Ramos B. V.. 1983. Analysis of the distribution of cholesterol in the intact cell. J. Biol. Chem. 258: 15130–15134. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Smith J. D., Miyata M., Ginsberg M., Grigaux C., Shmookler E., and Plump A. S.. 1996. Cyclic AMP induces apolipoprotein E binding activity and promotes cholesterol efflux from a macrophage cell line to apolipoprotein acceptors. J. Biol. Chem. 271: 30647–30655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Le Goff W., Peng D. Q., Settle M., Brubaker G., Morton R. E., and Smith J. D.. 2004. Cyclosporin A traps ABCA1 at the plasma membrane and inhibits ABCA1-mediated lipid efflux to apolipoprotein A-I. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 24: 2155–2161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rogers M. A., Liu J., Song B. L., Li B. L., Chang C. C., and Chang T. Y.. 2015. Acyl-CoA:cholesterol acyltransferases (ACATs/SOATs): enzymes with multiple sterols as substrates and as activators. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 151: 102–107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Frolov A., Zielinski S. E., Crowley J. R., Dudley-Rucker N., Schaffer J. E., and Ory D. S.. 2003. NPC1 and NPC2 regulate cellular cholesterol homeostasis through generation of low density lipoprotein cholesterol-derived oxysterols. J. Biol. Chem. 278: 25517–25525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ma X., Hu Y. W., Mo Z. C., Li X. X., Liu X. H., Xiao J., Yin W. D., Liao D. F., and Tang C. K.. 2009. NO-1886 up-regulates Niemann-Pick C1 protein (NPC1) expression through liver X receptor alpha signaling pathway in THP-1 macrophage-derived foam cells. Cardiovasc. Drugs Ther. 23: 199–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Schultz J. R., Tu H., Luk A., Repa J. J., Medina J. C., Li L., Schwendner S., Wang S., Thoolen M., Mangelsdorf D. J., et al. . 2000. Role of LXRs in control of lipogenesis. Genes Dev. 14: 2831–2838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Das A., Goldstein J. L., Anderson D. D., Brown M. S., and Radhakrishnan A.. 2013. Use of mutant 125I-perfringolysin O to probe transport and organization of cholesterol in membranes of animal cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 110: 10580–10585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Golfetto O., Hinde E., and Gratton E.. 2013. Laurdan fluorescence lifetime discriminates cholesterol content from changes in fluidity in living cell membranes. Biophys. J. 104: 1238–1247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Malacrida L., and Gratton E.. 2018. LAURDAN fluorescence and phasor plots reveal the effects of a H2O2 bolus in NIH-3T3 fibroblast membranes dynamics and hydration. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 128: 144–156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ranjit S., Dvornikov A., Dobrinskikh E., Wang X., Luo Y., Levi M., and Gratton E.. 2017. Measuring the effect of a Western diet on liver tissue architecture by FLIM autofluorescence and harmonic generation microscopy. Biomed. Opt. Express. 8: 3143–3154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Iaea D. B., Mao S., Lund F. W., and Maxfield F. R.. 2017. Role of STARD4 in sterol transport between the endocytic recycling compartment and the plasma membrane. Mol. Biol. Cell. 28: 1111–1122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Neufeld E. B., Cooney A. M., Pitha J., Dawidowicz E. A., Dwyer N. K., Pentchev P. G., and Blanchette-Mackie E. J.. 1996. Intracellular trafficking of cholesterol monitored with a cyclodextrin. J. Biol. Chem. 271: 21604–21613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Garbarino J., Pan M., Chin H. F., Lund F. W., Maxfield F. R., and Breslow J. L.. 2012. STARD4 knockdown in HepG2 cells disrupts cholesterol trafficking associated with the plasma membrane, ER, and ERC. J. Lipid Res. 53: 2716–2725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Mesmin B., Bigay J., Polidori J., Jamecna D., Lacas-Gervais S., and Antonny B.. 2017. Sterol transfer, PI4P consumption, and control of membrane lipid order by endogenous OSBP. EMBO J. 36: 3156–3174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wang H., Ma Q., Qi Y., Dong J., Du X., Rae J., Wang J., Wu W. F., Brown A. J., Parton R. G., et al. . 2019. ORP2 delivers cholesterol to the plasma membrane in exchange for phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate (PI(4,5)P2). Mol. Cell. 73: 458–473.e7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Calderon-Dominguez M., Gil G., Medina M. A., Pandak W. M., and Rodriguez-Agudo D.. 2014. The StarD4 subfamily of steroidogenic acute regulatory-related lipid transfer (START) domain proteins: new players in cholesterol metabolism. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 49: 64–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bagatolli L. A. 2015. Monitoring membrane hydration with 2-(dimethylamino)-6-acylnaphtalenes fluorescent probes. Subcell. Biochem. 71: 105–125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Malacrida L., Gratton E., and Jameson D. M.. 2015. Model-free methods to study membrane environmental probes: a comparison of the spectral phasor and generalized polarization approaches. Methods Appl. Fluoresc. 3: 047001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Parasassi T., Di Stefano M., Ravagnan G., Sapora O., and Gratton E.. 1992. Membrane aging during cell growth ascertained by Laurdan generalized polarization. Exp. Cell Res. 202: 432–439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Parasassi T., Gratton E., Yu W. M., Wilson P., and Levi M.. 1997. Two-photon fluorescence microscopy of laurdan generalized polarization domains in model and natural membranes. Biophys. J. 72: 2413–2429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ito A., Hong C., Rong X., Zhu X., Tarling E. J., Hedde P. N., Gratton E., Parks J., and Tontonoz P.. 2015. LXRs link metabolism to inflammation through Abca1-dependent regulation of membrane composition and TLR signaling. eLife. 4: e08009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Elustondo P., Martin L. A., and Karten B.. 2017. Mitochondrial cholesterol import. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Cell Biol. Lipids. 1862: 90–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Perreault M., Maltais R., Kenmogne L. C., Letourneau D., LeHoux J. G., Gobeil S., and Poirier D.. 2018. Implication of STARD5 and cholesterol homeostasis disturbance in the endoplasmic reticulum stress-related response induced by pro-apoptotic aminosteroid RM-133. Pharmacol. Res. 128: 52–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Mesmin B., Pipalia N. H., Lund F. W., Ramlall T. F., Sokolov A., Eliezer D., and Maxfield F. R.. 2011. STARD4 abundance regulates sterol transport and sensing. Mol. Biol. Cell. 22: 4004–4015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Zhao K., and Ridgway N. D.. 2017. Oxysterol-binding protein-related protein 1L regulates cholesterol egress from the endo-lysosomal system. Cell Reports. 19: 1807–1818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Létourneau D., Lorin A., Lefebvre A., Cabana J., Lavigne P., and LeHoux J. G.. 2013. Thermodynamic and solution state NMR characterization of the binding of secondary and conjugated bile acids to STARD5. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1831: 1589–1599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Létourneau D., Lorin A., Lefebvre A., Frappier V., Gaudreault F., Najmanovich R., Lavigne P., and LeHoux J. G.. 2012. StAR-related lipid transfer domain protein 5 binds primary bile acids. J. Lipid Res. 53: 2677–2689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Stocco D. M. 2000. StARTing to understand cholesterol transfer. Nat. Struct. Biol. 7: 445–447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.