Abstract

The eicosanoids are a family of lipid mediators of pain and inflammation involved in multiple pathologies, including asthma, hypertension, cancer, atherosclerosis, and neurodegenerative diseases. These signaling mediators act locally, but are rapidly metabolized and transported to the systemic circulation as a mixture of primary and secondary metabolites. Accordingly, urine has become a useful readily accessible biofluid for monitoring the endogenous synthesis of these molecules. Herein, we present the validation of a rapid, repeatable, and precise method for the extraction and quantification of 32 eicosanoid urinary metabolites by LC-MS/MS. For 12 out of 17 deconjugated glucuronide eicosanoids, there was no improvement in recovered signal. These metabolites cover the major synthetic pathways, including prostaglandins, leukotrienes, and isoprostanes. The method linearity was >0.99 for all metabolites analyzed, the limit of detection ranged from 0.05–5 ng/ml, and the average extraction recoveries were >90%. All analytes were stable for at least three freeze/thaw cycles. The method was formatted for large-scale analysis of clinical cohorts, and the long-term repeatability was demonstrated over 15 months of acquisition, evidencing high precision (CV <15%, except for tetranorPGEM and 2,3-dinor-11β-PGF2α, which were <30%). The presented method is suitable for focused mechanistic studies as well as large-scale clinical and epidemiological studies that require repeatable methods capable of producing data that can be concatenated across multiple cohorts.

Keywords: liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry, lipid mediators, eicosanoids, prostaglandins, isoprostanes, thromboxanes, cysteinyl leukotrienes, urinary metabolites, inflammation, asthma

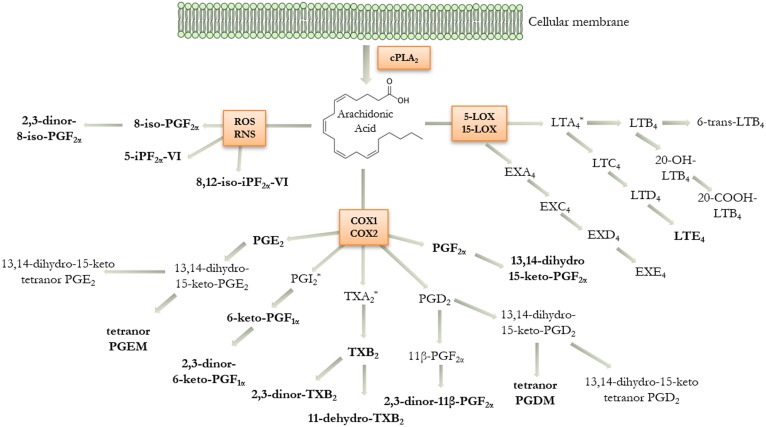

Eicosanoids are bioactive lipid mediators produced by the enzymatic and/or nonenzymatic oxidation of arachidonic acid (5,8,11,14-eicosatetraenoic acid) (1, 2). They play a fundamental role in promoting and modulating inflammation, providing both pro-inflammatory signals and terminating the inflammatory process (2), as well as maintaining tissue and vascular homeostasis (3). The biosynthesis of eicosanoids is initiated by phospholipase A2 (PLA2)-mediated release of arachidonic acid from cellular membrane phospholipids via hydrolysis (Fig. 1). The major enzymatic pathways involved in the generation of oxygenated species are catalyzed by cyclooxygenase (COX), lipoxygenase (LOX), and cytochrome P450. Arachidonic acid can also be converted by reactive oxygen species (ROS) and reactive nitrogen species (RNS) into isoprostanes, which are often used as indices of oxidative stress (Fig. 1) (4). The quantification of eicosanoid metabolites in human urine can serve as a systemic indicator of pathological processes in the vascular, respiratory, and other cellular systems (5–11). During the early inflammatory phase, eicosanoids are excreted by inflammatory cells and can increase up to 100-fold in local concentration (2). However, they are rapidly metabolized, cleared from the local milieu by the blood circulation, and excreted via the urine. Measurements of eicosanoids in the blood are difficult due to low circulating levels, rapid hepatic and renal clearance, and induction of biosynthesis during the sampling. Urine is therefore an optimal noninvasive biofluid for monitoring eicosanoid levels (6–12).

Fig. 1.

Schematic of the eicosanoid metabolic cascade displaying the human urinary metabolites included in the current platform. Arachidonic acid can be metabolized via lipoxygenase (LOX), cyclooxygenase (COX), and oxidative stress (ROS, RNS) pathways. Metabolites detected in urine are shown in bold letters. *Indicates unstable intermediates that are not included in the LC-MS/MS method (PGI2, TXA2, and LTA4). cPLA2, cytosolic phospholipase A2.

Eicosanoids have similar structures and often possess the same mass and fragmentation pattern [e.g., prostaglandin (PG)D2 vs. PGE2, and in particular PGF2α and several metabolites originating from PGD2 or the isoprostane pathway]. It is therefore necessary to achieve sufficient chromatographic separation to discriminate individual eicosanoids with a high degree of specificity. Toward this end, several targeted methods for qualitative and/or quantitative determinations of selected panels of eicosanoids in different biofluids have been published (13–18); however, few studies have examined in depth the urinary eicosanoid profile for large-scale profiling of most of the major pathways at the population level (19–22). In addition, the effect of glucuronide deconjugation upon observed eicosanoid levels has not been evaluated in detail. The current method was designed with the intent to achieve the necessary repeatability and precision for large-scale molecular phenotyping studies and to enable the direct comparison of urinary excretion levels between independent clinical studies. The method has therefore been optimized in terms of low urine volume consumption, broad metabolic pathway coverage, and long-term precision. The resulting method is highly reproducible, repeatable, and stable across multiple years of analysis, and is therefore well-suited for applications in molecular phenotyping studies, drug trials, other clinical investigations, and epidemiological monitoring of responses to exposures.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Standards and reagents

Standards for compounds listed in Table 1, deuterated analogs (supplemental Table S1), and butylated hydroxyl toluene were purchased from Cayman Chemical (Ann Arbor, MI). LC-MS grade methanol, isopropanol, acetonitrile, acetone, and acetic acid were purchased from Fisher Scientific (Waltham, MA). Milli-Q ultrapure deionized water was prepared in-house (Millipore Corporation., Billerica, MA). Methoxyamine hydrochloride, ammonia, and β-glucuronidase from Helix pomatia were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). The internal standard working solution and the standard mixture were stored in glass vials at −80°C for long-term storage. Calibration curves were prepared by serial dilution in methanol/water 1:1 (v/v) of the standard mixture for the PG metabolites and isoprostanes (PGMsIPs) method and in methanol/water 85:15 (v/v) for the cysteinyl leukotrienes (CysLTs) method, as described below. An internal standard mix solution was added to each calibration level prior to analysis.

TABLE 1.

Method characteristics for the quantification of eicosanoid metabolites in urine by LC-MS/MS

| Method | Compound | RT (min) | Transition | LOQ (pg on-column) | r | Recovery (%) | Intra-Day Precision (%) | Inter-Day Precision (%) | Matrix Effect (%) | Stabilitya | |||||||

| Low (n = 6) | Medium (n = 6) | High (n = 6) | Low (n = 6) | Medium (n = 6) | High (n = 6) | Low (n = 6) | Medium (n = 6) | High (n = 6) | t = 0 Months (n = 6) | t = 15 Months (n = 6) | |||||||

| I | Tetranor PGEM | 3.43 | 327 > 143 | 13 | 0.996 | 106 | 99 | 103 | 10 | 7 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 101 | 31.1 ± 5.3 | 40.8 ± 1.4 |

| Tetranor PGDM | 3.91 | 327 > 143 | 1 | 0.999 | 96 | 95 | 100 | 9 | 11 | 13 | 12 | 11 | 16 | 109 | 8.1 ± 0.3 | 7.9 ± 0.3 | |

| 2,3-Dinor-8-iso PGF2α | 6.81 | 325 > 237 | 1 | 0.998 | 105 | 99 | 104 | 4 | 6 | 3 | 7 | 5 | 6 | 84 | 4 ± 0.5 | 3.8 ± 0.2 | |

| 2,3-Dinor-11β-PGF2α | 7.15 | 325 > 145 | 1 | 0.996 | 100 | 97 | 102 | 10 | 2 | 1 | 16 | 18 | 12 | 82 | 4.7 ± 0.5 | 3.3 ± 0.2 | |

| 6-Keto-PGF1α | 7.24 | 369 > 163 | 1 | 0.998 | 104 | 98 | 98 | 0 | 3 | 4 | 9 | 4 | 4 | 119 | 2.3 ± 0.1 | 2.8 ± 0.2 | |

| 13,14-Dihydro-15- keto-tetranor-PGE2 | 7.51 | 297 > 109 | 5 | 0.996 | 92 | 107 | 103 | 11 | 7 | 9 | ND | 18 | 12 | 92 | 5.5 ± 0.2 | 4 ± 0.2 | |

| 13,14-Dihydro-15- keto-tetranor-PGD2 | 8.12 | 297 > 109 | 3 | 0.999 | 102 | 98 | 103 | 8 | 5 | 4 | 6 | 2 | 7 | 92 | 8.1 ± 0.4 | 8.8 ± 0.3 | |

| 8-Iso-PGF2α | 9.08 | 353 > 193 | 2 | 0.999 | 100 | 97 | 95 | 11 | 4 | 5 | 14 | 6 | 7 | 96 | 2.4 ± 0.3 | 1.8 ± 0.1 | |

| 11β-PGF2α | 9.49 | 353 > 291 | 2 | 0.999 | 96 | 91 | 94 | 8 | 3 | 4 | 1 | 4 | 1 | 117 | 11.8 ± 0.1 | 15.3 ± 0.3 | |

| 5-iPF2α-VI | 9.85 | 353 > 115 | 4 | 0.999 | 94 | 93 | 99 | 9 | 3 | 3 | 7 | 2 | 2 | 109 | 8.9 ± 0.3 | 8.5 ± 0.8 | |

| PGF2α | 10.91 | 353 > 291 | 2 | 0.999 | 103 | 86 | 88 | 5 | 5 | 2 | 5 | 2 | 2 | 123 | 17.5 ± 1.2 | 15.8 ± 0.8 | |

| 11-Dehydro-TXB2 | 11.33 | 367 > 161 | 3 | 0.999 | 97 | 92 | 95 | 8 | 2 | 4 | 6 | 3 | 1 | 121 | 7.7 ± 0.3 | 8.7 ± 0.7 | |

| PGE2 | 11.40 | 351 > 271 | 1 | 0.998 | 100 | 91 | 94 | 13 | 6 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 114 | 3.5 ± 0.2 | 3.6 ± 0.3 | |

| PGD2 | 12.19 | 351 > 271 | 2 | 0.996 | ND | 79 | 98 | ND | 11 | 10 | ND | 13 | 5 | 122 | 2.1 ± 0.2 | 5.3 ± 0.2 | |

| PGE1 | 12.25 | 353 > 273 | 10 | 0.999 | ND | 85 | 91 | ND | 5 | 4 | ND | 6 | 2 | 113 | 12.2 ± 0.8 | 12.4 ± 0.3 | |

| 13,14-Dihydro-15-keto-PGE2 | 13.98 | 351 > 175 | 2 | 0.999 | 90 | 90 | 95 | 8 | 4 | 2 | 10 | 2 | 1 | 113 | 9.1 ± 0.3 | 10 ± 0.5 | |

| 8,12-Iso-iPF2α-VI | 14.12 | 353 > 115 | 1 | 0.999 | 100 | 91 | 91 | 6 | 4 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 126 | 11.6 ± 0.4 | 11.3 ± 0.7 | |

| 13,14-Dihydro-15-keto-PGF2α | 14.19 | 353 > 291 | 3 | 0.999 | 101 | 90 | 94 | 8 | 4 | 5 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 125 | 20.2 ± 0.5 | 21.2 ± 0.7 | |

| 13,14-Dihydro-15-keto-PGE1 | 14.86 | 353 > 209 | 2 | 0.997 | 93 | 92 | 88 | 7 | 5 | 4 | 27 | 10 | 4 | 124 | 10.1 ± 0.2 | 10.5 ± 0.6 | |

| 13,14-Dihydro-15-keto-PGD2 | 15.04 | 351 > 175 | 3 | 0.998 | 97 | 90 | 90 | 11 | 6 | 1 | 6 | 5 | 3 | 102 | 12.1 ± 0.5 | 16.4 ± 0.9 | |

| II | 2,3-Dinor-6-keto-PGF1α | 3.12 | 370 > 232 | 10 | 0.999 | 106 | 104 | 104 | 6 | 4 | 6 | 12 | 14 | 11 | 117 | 82.1 ± 5.8 | 68.2 ± 7.8 |

| 2,3-Dinor-TXB2 | 3.45 | 370 > 155 | 3 | 0.999 | 108 | 97 | 100 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 5 | 2 | 2 | 115 | 21.7 ± 2.3 | 21.3 ± 0.9 | |

| TXB2 | 3.81 | 398 > 169 | 1 | 0.999 | 97 | 92 | 95 | 7 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 118 | 3.5 ± 0.3 | 3.4 ± 0.1 | |

| III | 20-Carboxy-LTB4 | 0.85 | 365 > 195 | 3 | 0.996 | ND | 89 | 86 | ND | 6 | 5 | ND | 25 | 27 | 5 | 0.2 ± 0.1 | 4.7 ± 0.4b |

| 20-Hydroxy-LTB4 | 0.90 | 351 > 195 | 3 | 0.997 | 85 | 82 | 82 | 0 | 6 | 6 | 9 | 18 | 18 | 5 | 0.2 ± 0.1 | 0.1 ± 0.1 | |

| EXC4 | 1.55 | 624 > 306 | 4 | 0.999 | 90 | 69 | 80 | 6 | 15 | 13 | 19 | 12 | 4 | 76 | 2.2 ± 0.3 | 0.9 ± 0.1 | |

| LTD4 | 1.68 | 495 > 187 | 3 | 0.997 | 74 | 65 | 68 | 8 | 9 | 8 | 16 | 8 | 9 | 136 | 1.3 ± 0.1c | 3 ± 0.2 | |

| EXE4 | 1.87 | 438 > 333 | 3 | 0.999 | 74 | 75 | 76 | 13 | 6 | 6 | 2 | 5 | 3 | 173 | 2.7 ± 0.2 | 3 ± 0.2 | |

| LTC4 | 2.29 | 624 > 306 | 4 | 0.999 | 93 | 75 | 83 | 10 | 8 | 14 | 9 | 7 | 7 | 80 | 1.6 ± 0.2 | 0.8 ± 0.1 | |

| LTE4 | 2.35 | 438 > 333 | 3 | 0.999 | 82 | 81 | 83 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 131 | 5.1 ± 0.3 | 4.6 ± 0.4 | |

| 6-trans-LTB4 | 3.23 | 335 > 195 | 2 | 0.997 | 84 | 82 | 83 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 140 | 2.7 ± 0.1 | 2.8 ± 0.2 | |

| LTB4 | 3.46 | 335 > 195 | 2 | 0.999 | 77 | 76 | 77 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 5 | 5 | 6 | 129 | 4.3 ± 0.2 | 3.4 ± 0.1 | |

| RT, retention time; r, linearity; Low, low concentration; Medium, medium concentration; High, high concentration; ND, not detected. | |||||||||||||||||

| a Data are shown as the concentration (nanograns per milligram) of the indicated compound in the fortified laboratory reference material at the time of preparation (t = 0 months) or after 15 months storage at −80°C (t = 15 months). | |||||||||||||||||

| b The observed reduced stability of this compound is most likely a combination of large matrix effects, low precision, and low recovery for quantification. | |||||||||||||||||

| c The initial timepoint is t = 4 months for this compound. | |||||||||||||||||

A laboratory reference material was prepared by adding 2 ml of a combined analytical standard mix containing adjusted concentrations of each eicosanoid standard, in the range from 250 to 1,350 ng/ml, to 500 ml of pooled human urine (final analyte concentration 1–5 ng/ml). This level of fortification ensured that optimal signal intensity was always quantified after solid phase extraction. To maintain the homogeneity of the urine during aliquoting, a magnetic stirrer was used while transferring the prepared laboratory reference material into 350 aliquots of 1.4 ml in Eppendorf tubes. Aliquots were immediately stored at −80°C. For LC-MS/MS analysis, urine samples were divided into batches of 21 samples and three aliquots of the laboratory reference material were used as quality control (QC) samples in each batch. QC samples were processed and quantified using the same method as the study samples in order to monitor analyte variability. For the purposes of method validation, volume optimization, and enzymatic hydrolysis experiments, pooled urine was used as described by Balgoma et al. (21).

Solid phase extraction

PGMsIPs.

PG metabolites, thromboxanes, and isoprostanes were extracted on 3 cc/60 mg Evolute Express ABN SPE cartridges (Biotage, Uppsala, Sweden) automatically using positive pressure (nitrogen gas) operated by an Extrahera system (Biotage). Urine samples (300 μl) were mixed with 100 μl of an internal standard mixture (see concentrations in supplemental Table S1) and 0.5 ml of a 0.5% acetic acid solution, and diluted up to 2.5 ml with Milli-Q water. Samples were loaded on SPE cartridges previously conditioned with 2 ml of methanol (N2 positive pressure: 1.2 bar for 80 s) and equilibrated with 2.5 ml 0.1% acetic acid (N2 positive pressure: 1.5 bar for 110 s). The cartridges were washed with 3 ml of 0.1% acetic acid (N2 positive pressure: 1.5 bar for 120 s), then dried by using a N2 positive pressure gradient (1.2 bar for 120 s followed by 5 bar for 750 s). Eicosanoids were eluted with 3 ml of acetonitrile (N2 positive pressure: 1 bar for 250 s followed by 5 bar for 150 s). Eluates were evaporated under a gentle stream of N2 gas to dryness by a TurboVap LV evaporation system (Biotage). Samples were resuspended in 100 μl of methanol/water 1:1 (v/v) and filtered by centrifugation using 0.1 μm polyvinylidene fluoride membrane spin filters (Amicon; Merck Millipore Corporation, Billerica, MA). Analysis was performed by Method I (Table 1). For the analysis of eicosanoid metabolites with tautomers (TXB2, 2,3-dinor-TXB2, and 2,3-dinor-6-keto-PGF1α), 40 μl of the resuspended sample was derivatized by adding 5 μl of methoxyamine hydrochloride 1:2 (w/v). After 15 min, the reaction was stopped by adding 5 μl of acetone. After an additional 15 min, the sample was basified using 5 μl of ammonia 12.5% (w/v). The analysis of derivatized tautomers was performed using Method II (Table 1).

CysLTs.

CysLTs were extracted using 3 cc/60 mg Evolute Express ABN SPE cartridges (Biotage) by the same SPE handling system as for the PGMsIPs. Urine samples (1 ml) were mixed with 50 μl of an internal standard mixture (see concentrations in supplemental Table S1) and 300 μl of a 1% acetic acid solution and diluted up to 3 ml with Milli-Q water. Samples were loaded to SPE cartridges previously conditioned with 3 ml of methanol (N2 positive pressure: 1.2 bar for 80 s) and equilibrated with 2.5 ml 0.1% acetic acid (N2 positive pressure: 1.5 bar for 180 s). The cartridges were washed with 1 ml of water/methanol (1:1, v/v) (N2 positive pressure: 1.5 bar for 90 s) and 3 ml of 0.1% acetic acid (N2 positive pressure: 1.5 bar for 120s). Cartridges were then dried by using a N2 positive pressure gradient (1.2 bar for 120 s followed by 5 bar for 750 s). CysLTs were eluted with 1 ml of methanol (N2 positive pressure: 1 bar for 250 s followed by 5 bar for 150 s). Eluates were evaporated under a gentle stream of N2 gas until dryness using the TurboVap LV evaporation system. Samples were resuspended in 50 μl of methanol/water 85:15 (v/v) and filtered by centrifugation using 0.1 μm polyvinylidene fluoride membrane spin filters (Amicon; Merck Millipore Corporation). Analysis was performed by applying Method III (Table 1).

LC-MS/MS analysis

Chromatographic separations were carried out using a Waters Acquity UPLC system (Waters, Milford, MA). Separation of the eicosanoids was achieved by an ACQUITY UPLC® HSS T3 (100 × 2.1 mm i.d., 1.8 μm particle size) column equipped with an ACQUITY UPLC® HSS T3 VanGuard™ precolumn (5 × 2.1 mm, 1.8 μm). The column temperature was set to 40°C. The mobile phase consisted of water with 0.1% of acetic acid (solvent A) and acetonitrile/isopropanol 9:1 v/v (solvent B) at a flow rate of 0.5 ml/min−1. The injection volume used was 7.5 μl. Chromatographic gradients for LC Methods I–III were as follows: Method I (PGMsIPs): from 0 to 0.5 min, 90% A; from 0.5 to 4.5 min, to 84% A; from 4.5 to 5 min, to 69% A; from 5 to 13 min, to 67% A; from 13 to 16.2 min, 45% A; to 2%A at 16.9 min; during 1.1 min, 2% A; from 18 to 18.5 min, to 90% A; from 18.5 to 20 min, 90% A. Method II (derivatized eicosanoid tautomers): initial at 75% A; from 0 to 2.5 min, 66% A; from 2.5 to 3 min, to 58% A; from 3 to 3.5 min, to 5% A; during 1 min, 5% A; from 4.5 to 4.7 min, to 75% A; from 4.7 to 6 min, 75% A. Method III (CysLTs): initial at 55% A; from 0 to 4 min, 45% A; from 4 to 4.2 min, to 5% A; during 0.8 min, 5% A; from 5 to 5.2 min, to 55% A; from 5.2 to 6 min, 55% A.

Data acquisition was performed using a triple quadrupole (Xevo TQ-S) mass spectrometer system (Waters) equipped with an ESI source. All LC methods used negative ESI and scheduled selected reaction monitoring mode to detect individual eicosanoids (supplemental Fig. S1). The most specific and sensitive selected reaction monitoring transition was selected for each analyte to avoid interference. Dwell time was automatically adjusted in order to acquire 12 points per chromatographic peak. The source parameters were fixed as follows: capillary voltage was set to 2.20 kV, desolvation gas flow was set to 1,000 l/h, cone gas flow at 150 l/h, and desolvation temperature was 600°C. The cone voltage and collision energy were individually optimized for each analyte. Peak detection, integration, and quantification were performed using the software Masslynx™ and TargetLynx™.

Volume optimization

The required volume for urine sample extraction was optimized for each SPE method (PGMsIPs and CysLTs) in order to minimize the amount of sample used. Urine samples with varying specific gravity values (1.0032, 1.0134, and 1.0249) were extracted using different volumes to verify the capability to detect all eicosanoids independently of the extent of the dilution. The sample volumes tested for each method were: PGMsIPs (200, 300, and 400 μl) and CysLTs (0.5, 1.0, and 1.5 ml).

Normalization

Specific gravity was measured in n = 300 urine samples using a refractometer (Digital Urine Specific Gravity Refractometer UG-α; Atago Co. Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) for normalization (23). The urinary eicosanoid concentrations were corrected to a urine specific gravity of 1.0200 based on the following equation (24):

Creatinine was measured in the same urine samples using a previously described method (25).

Glucuronidation

In order to screen for potential eicosanoid glucuronide conjugates in urine, an enzymatic hydrolysis step was evaluated. Prior to the extraction procedure described above, 20 μl of β-glucuronidase from Helix pomatia were added to urine samples (300 μl), and after the addition of 200 μl of acetate buffer 0.1 M (pH 4.9), samples were incubated at 37°C for 2 h. Following cooling at room temperature, 200 μl of methanol/HCl (200 mM) were added to stop the reaction (26). Technical replicates of a native urine sample both with and without β-glucuronidase treatment (n = 5) were worked-up using the conditions described above.

Method validation

The following parameters were evaluated: limit of quantitation (LOQ), linearity, stability, extraction recovery, precision for intra- and inter-assay at three concentration levels, matrix effects, and repeatability. For the eicosanoids listed in Table 1, calibration curves were prepared daily and spiked with internal standards. In order to evaluate the linearity, nine calibration curve points were analyzed by the optimized method. The linearity of the calibration curves was then determined using linear regression analysis using 1/X weighting. The LOQ was defined as the lowest concentration (in terms of on-column eicosanoid levels in picograms) at which the peak response was 10 times that of the noise (10 S/N).

The stability of eicosanoids in urine during freeze/thaw cycles was examined at three time points, and in triplicates, with each time point passing a freeze/thaw cycle from −80°C to 4°C. Baseline measurements (T0) were kept frozen until analysis. Samples were thawed at 4°C and refrozen at −80°C for the next study day. The cycle was repeated for three consecutive days. The stability of analytes after freeze/thaw cycles was assessed by the percentage change from T0 to each freeze/thaw cycle (T1, T2, and T3).

The extraction recovery was assessed by the analysis of six replicates of a native urine sample spiked with the compounds before extraction, and six replicates of the same urine sample to which the analytes were added after extraction. The ratio of the peak areas between the analytes and the internal standard obtained from the extracted spiked samples was compared with ratios obtained for samples in which the analytes were added after extraction of the matrix (representing 100% of extraction recovery).

The intra-assay precision was calculated after analysis of six replicates of samples spiked at three different concentrations on the same day. Inter-assay precision was calculated after analysis of six samples spiked at these three concentration levels in three different days. Precision was measured as the relative standard deviation of the ratios of the peak areas of the compound to the internal standard.

For the evaluation of matrix effects, six aliquots of a native urine sample were extracted and then spiked with the analytes to avoid losses during the extraction procedure. The ion suppression/enhancement was calculated by comparing the responses between these spiked extracts and the same amount of the standard mix spiked into pure LC solvent. Intra- and inter-batch variability was evaluated using QC samples and reported as the percent relative standard deviation (%RSD).

Clinical samples

For the assessment of metabolite excretion of eicosanoid metabolites, urine samples from 18 atopic volunteers (skin prick test positive to birch, timothy grass, Pacific grasses, or Dermatophagoides pterinyssinus) aged 19–50 years were analyzed. Our exposure protocol and patient demographics are described in detail elsewhere (27, 28). Briefly, we employed a double-blinded randomized crossover study on 11 women and 7 men, aged 20–46 years. Baseline forced expiratory volume in 1 s ranged from 66% to 143% of the predicted value. Participants were exposed, in a crossover washed out by 4 weeks, to filtered air and diluted diesel exhaust (at 300 μg PM2.5 per cubic meter, a level similar to those frequently encountered in major Asian cities) for 2 h, each followed by segmental allergen challenge (to an allergen to which they were shown sensitized, by virtue of having a positive skin prick test) (27). Urine samples were collected before diesel exhaust exposure (baseline) and 4 h after the segmental allergen challenge. All participants fasted for at least 12 h prior to each visit. Immediately after urine collection, samples were aliquoted, and butylated hydroxy toluene was added to achieve a final concentration of 227 μM. Samples were then stored at −80°C until the day of analysis. The samples were obtained and utilized consistent with ethical approval from the Clinical Research Ethics Board of the University of British Columbia (certificate H11-01831). Informed consent was obtained from all research participants, and the study abided by the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Data analysis and statistics

For LC-MS/MS data, the TargetLynx application manager (Waters) was used for quantification. Statistical analysis was performed using nonparametric multiple t-test; groups were compared by using the Wilcoxon signed rank test. Statistical analysis was performed in GraphPad Prism v5.02 (GraphPad Software) and graphs were prepared in the same software, Excel 2010 (Microsoft Corp.), or TIBCO Spotfire nv.7.0.0.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Volume optimization

The optimal volume to be extracted for each method was determined based upon the minimum volume of matrix in which those compounds that are routinely detected in urine (Table 2) could be quantified at the highest dilution factor. A volume of 300 μl was selected for the analysis of PGMsIPs (Methods I and II), and 1 ml for the analysis of the CysLTs (Method III). In addition, 100 μl is required for the specific gravity measurement. Accordingly, a total volume of 1.4 ml of urine is required for the complete workflow. This relatively low volume is advantageous for studies in which sample volume may be limited (e.g., pediatric sampling). It also has the advantage that urine samples can be collected in 2 ml tubes, which are amenable for biobanking because they can be stored in standard freezer boxes of 100 positions. This storage format minimizes space consumption in low temperature freezers.

TABLE 2.

Eicosanoid metabolites routinely detectable in urine

| Parent Compound | Eicosanoid Metabolite | %RSDa | %RSD (15 months)b | %RSD [Balgoma et al. (21)]c |

| PGE2 | PGE2 | 6.7 | 12.4 | 6.6 |

| Tetranor PGEM | 15.0 | 28 | 22.9 | |

| PGD2 | 2,3-Dinor-11-β-PGF2α | 6.3 | 18.2 | 14.4 |

| Tetranor PGDM | 5.2 | 9.1 | 8.5 | |

| PGF2α | PGF2α | 8.5 | 8.4 | 9.7 |

| 13,14-Dihydro-15-keto-PGF2α | 3.0 | 7.8 | Not included | |

| PGI2 | 6-Keto-PGF1α | 6.0 | 10.7 | Not included |

| 2,3-Dinor-6-keto-PGF1α | 5.7 | 13.8 | 15.7 | |

| TXA2 | TXB2 | 7.4 | 11.8 | 7.8 |

| 11-DehydroTXB2 | 5.6 | 6.7 | 12.1 | |

| 2,3-Dinor-TXB2 | 11.2 | 7.1 | 15.1 | |

| Isoprostanes | 8-IsoPGF2α | 8.3 | 12.6 | 8.8 |

| 2,3-Dinor-8-isoPGF2α | 7.9 | 14.3 | 8.7 | |

| 5-iPF2α-VI | 3.9 | 9.0 | Not included | |

| 8,12-Iso-iPF2α-VI | 2.7 | 7.3 | 4.0 | |

| LTE4 | LTE4 | 4.1 | 10.1 | 8.4 |

Normalization

The concentrations of endogenous metabolites in urine can vary extensively due to variations in fluid intake or salt excretion (12, 29). Methods for the normalization of metabolite concentrations, such as osmolality, creatinine, or specific gravity (i.e., refractive index), are therefore necessary in order to compensate for the dilution of urine samples. One of the most common methods for metabolite level normalization is to use the urine creatinine concentration (12, 29). However, during exercise, increased muscle turnover contributes to elevated serum creatinine levels, which may skew the normalization results (30). This is of particular relevance for measurements in athletes, who are extremely physically active (29). In addition, a malfunctioning kidney may alter the balance of excretion/re-uptake of creatinine, which for example occurs during kidney failure (30). Taken together, optical density measures such as specific gravity have emerged as an attractive and convenient alternative for normalization of urinary metabolite levels (31). However, there is still a potential confounder because glucose and protein content can influence the optical density of the urine (12, 31). Despite these issues, specific gravity has become the gold standard method for the correction of urinary concentrations used by the World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA)-accredited laboratories (23).

In the current study, creatinine and specific gravity were both measured in order to evaluate their correlation (supplemental Fig. S2). These results were in accordance with previously published results (29, 31–33), with a good correlation between the two approaches (r = 0.79). Given that creatinine and specific gravity gave similar results, and that specific gravity is a simple and rapid standard to estimate the urine concentration accepted by WADA, we chose to use specific gravity normalization for urinary normalization. While specific gravity normalization does require a larger sample volume (100 μl for specific gravity vs. 50 μl for creatinine quantification), specific gravity measurements are generally less laborious and time-consuming compared with creatinine measurements.

Glucuronidation

Glucuronidation is a major conjugation mechanism for the formation of polar metabolites to facilitate their excretion in urine (34). Consequently, it has been recommended to pretreat urine samples with β-glucuronidase to determine the total excretion of urinary eicosanoids and, thus, obtain a more accurate indication of total systemic production (22, 26, 35). For this reason, we tested the effects of an enzymatic hydrolysis step before the extraction of urine. While 12 of the 17 deconjugated eicosanoids demonstrated an improvement in signal, no additional eicosanoid metabolites were detected following enzyme hydrolysis and the unconjugated eicosanoids were unaffected by the enzymatic treatment (supplemental Table S2).

Validation results

The method was validated following the recommendations for bioanalytical method validation (36) (Table 1). The methods were determined to be selective and specific following the analysis of several urine samples from independent sources. Specifically, the absence of interfering substances at the retention times of the compounds of interest and internal standards were verified (data not shown). All calibration curves were linear, with correlation coefficients (r) ranging from 0.996 to 0.999 for all compounds. Extraction recoveries were calculated at three different concentration levels. Values near 100% were obtained for all PG, isoprostane, and thromboxane metabolites (Methods I and II). Recoveries of ∼80% were obtained for the CysLTs (Method III). Extraction recoveries were evaluated as well for the internal standards (supplemental Table S1). Values >90% were obtained for 16 out of 20 internal standards and >70% recoveries were obtained for the remainder. Table 1 lists the intra- and inter-assay precisions, estimated at three concentration levels, expressed as the %RSD of the signals obtained. The intra-day precision values obtained were <15% for all compounds at the three concentrations tested. The %RSD for inter-day precision evidenced <20% variation for all sixteen compounds that were consistently detected in urine.

One of the main obstacles in MS is the ion suppression or enhancement induced by various sample matrix constituents. However, this problem is generally addressed through the use of stable isotopically labeled internal standards. Accordingly, the matrix effects for the current method were evaluated for each endogenous eicosanoid. An elevation of signal >20% was found for nine eicosanoids, while a decrease of 24% was only found for one eicosanoid (Table 1). All the compounds regularly detected in urine were stable for at least three freeze/thaw cycles (supplemental Table S3). In particular, levels of the stable end-point product from the CysLT pathway, leukotriene (LT)E4, were unchanged following freezing, in contrast to the more seldom detected LTC4 and LTD4. Therefore, the method allows for consistent estimation of eicosanoid metabolite pathway concentrations for up to three freeze/thaw cycles.

The reproducibility of the method was further evaluated by the analysis of an in-house laboratory reference material. Reference materials are an important component of the quality assessment strategy to ensure monitoring of sample processing and instrument performance. It is of particular importance to determine the batch performance and concentration range homogeneity over time to enable integration of data from multiple studies. Table 2 displays the %RSD of the eicosanoid metabolites in the laboratory reference urine that are routinely detected in authentic urine samples. In order to compare the performance of our new method versus the earlier version, we compared the %RSD obtained in the diesel exhaust exposure study (n = 36) (27), and the %RSD obtained in the laboratory reference material (n = 32) from our previously published allergen provocation study (21). Improved CVs were obtained for all compounds in the present method, as demonstrated by reducing the individual CVs by an average of 3.7 unit percent. For all reported eicosanoids in the allergy provocation study (27), individual CVs obtained did not exceed 10%, except for tetranor PGEM (15%) and 2,3-dinor-TXB2 (11%), demonstrating the improved performance of the method (Table 2).

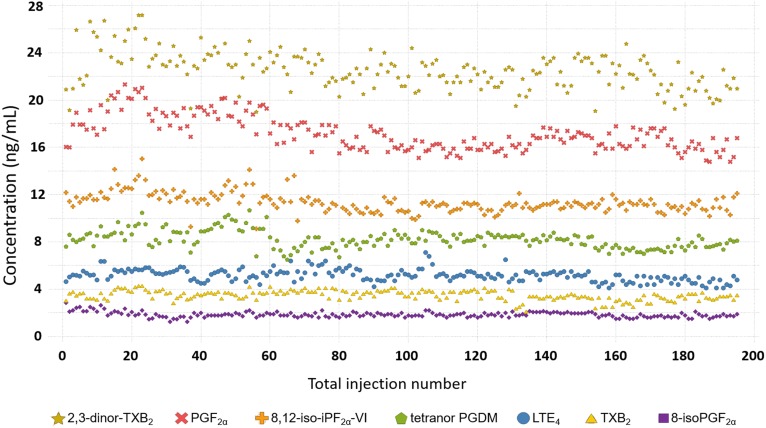

The long-term repeatability of the method was demonstrated across seven independent cohorts analyzed over a period of 15 months (Table 2; Fig. 2). The graph represents the analysis of n = 195 aliquots of the prepared laboratory reference material (n = 3 aliquots per batch across n = 65 batches) included during the analysis of n = 1,365 authentic study samples. The laboratory reference material samples are used as external QC samples during long-term routine analysis to monitor method performance, and for the integration of multiple studies. The method evidenced high precision (CV <15%, except for tetranor PGEM and 2,3-dinor-11β-PGF2α, which were <30%), demonstrating its suitability for long-term monitoring and concatenation of concentration data from independent studies.

Fig. 2.

Concentration of seven representative metabolites (2,3-dinor-TXB2, PGF2α, 8,12-iso-iPF2α-VI, tetranor PGDM, LTE4, TXB2, and 8-isoPGF2α) quantified in 195 aliquots of a fortified laboratory reference material over a period of 15 months. For each batch of samples (n = 21), three aliquots of the reference material were extracted. The graph represents the analysis of 65 batches of samples distributed in seven different cohorts (n = 1,365 samples).

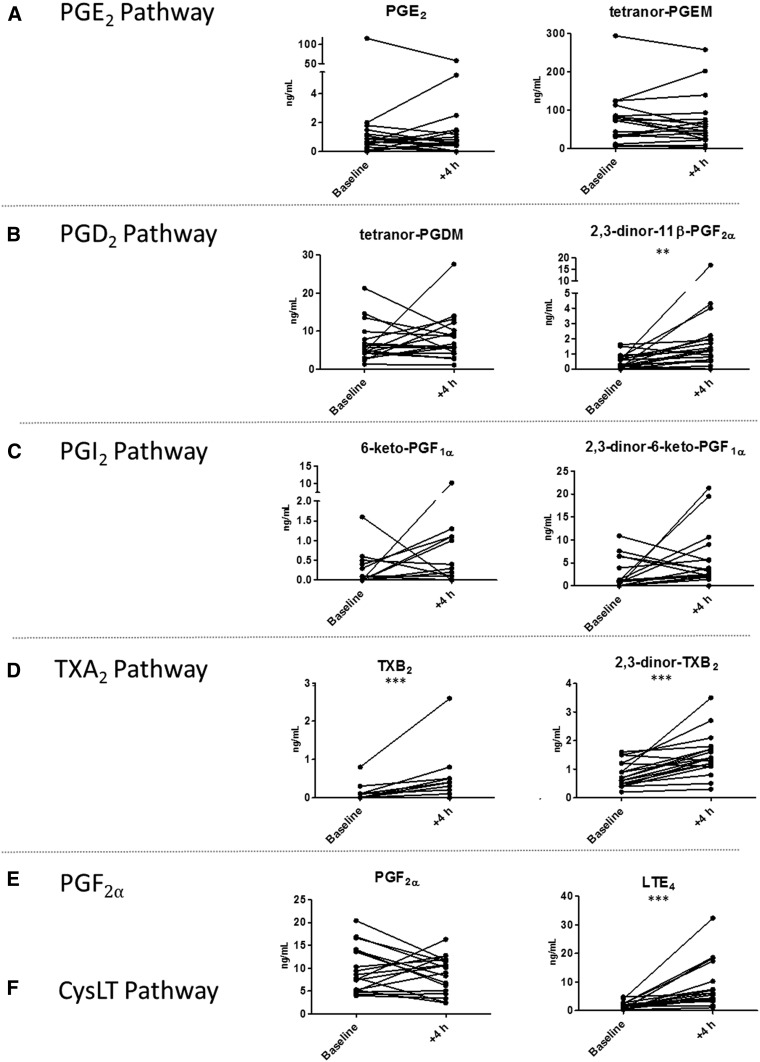

Urinary eicosanoids increase following allergen challenge

The method was applied to urine samples collected from 18 atopic volunteers before and after exposure to diesel exhaust for 2 h followed by a segmental allergen challenge (27). A total of 15 urinary eicosanoid metabolites were detected in the samples, 11 of which were produced from enzymatic sources (Fig. 3) and 4 from autoxidation (supplemental Fig. S3). Following allergen challenge, the urinary levels of LTE4 significantly increased, in accordance with previous studies (17, 21, 37–39). The urinary levels of the bronchoconstrictor PGD2 metabolite, 2,3-dinor-11β-PGF2α, were also significantly elevated (39). The allergen provocation was associated with significantly increased urinary excretion of TXB2 and 2,3-dinor-TXB2, indicating increased biosynthesis of TXA2 (17, 37, 38, 40). TXA2 is most likely produced by platelets and is also a potent bronchoconstrictor. The effect of PGD2 and TXA2 on the thromboxane receptor (TP) might explain the protective effects of TP antagonists observed in allergen-induced bronchoconstriction (41). Significant changes in urinary concentrations of isoprostanes, 2,3-dinor-8-isoPGF2α, 8-isoPGF2α, and 5-iPF2α-VI, were also found (supplemental Fig. S3), consistent with increased oxidative stress associated with allergen provocation (17, 42). In agreement with our previous allergen-challenge study using the prior more limited version of this platform (17), we did not detect any changes in the urinary levels of the bronchoprotective PGE2 or its metabolite, tetranor PGEM, or in the prostacyclin metabolites, 6-keto-PGF1α and 2,3-dinor-6-keto-PGF1α, after the challenge (17, 37, 40). These findings further demonstrate the utility of urinary eicosanoid profiling to detect inflammatory responses associated with allergen provocation. Moreover, the current data derive from a local topical allergen challenge in only one airway segment, whereas the previous investigation used inhaled allergen exposing the whole lung to the allergen (17). The complete replication of the profile of eicosanoid metabolites in urine after the whole lung challenge in this local challenge lends strong support to the concept that changes in urinary metabolites truly reflect the local reactions in the airways even when the whole lung has been activated by the inhalation challenge. The possibility that secondary release from extra-pulmonary sources contribute may therefore be dismissed.

Fig. 3.

Urinary concentration of detected enzymatically-derived eicosanoids in pre- (baseline) and 4 hours post-allergen challenge performed after diesel exhaust exposure (n=18) (27). Metabolites are displayed on a pathway-specific basis. A: tetranor-PGEM from prostaglandin E2 (PGE2). B: tetranor-PGDM and 2,3-dinor-11β-PGF2α from prostaglandin D2 (PGD2). C: 6-keto-PGF1α and 2,3-dinor-6-keto-PGF1α from the prostaglandin I2 (PGI2). D: 2,3-dinor-TXB2 from thromboxane B2 (TXB2). E: prostaglandin F2α (PGF2α). F: cysteinyl-leukotriene E4 (LTE4) from the CysLT pathway. The compound 11-dehydroTXB2 did not change with allergen challenge and is excluded for graphical simplicity. Groups were compared by using the Wilcoxon signed-rank test; *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001.

Methodological improvements

Multiple improvements were made to the current workflow in relation to previously published methods, with a focus on formatting the current method to be suitable for large-scale analyses. Previous methods were limited in metabolic coverage (11, 43–47), required laborious solvent-intensive liquid-liquid extraction (35), long run-times (6, 21, 43–45), time-consuming absorbance measurements (21), large extraction volume (22, 44, 47), and/or enzymatic hydrolysis (22, 35). While these methods may offer specific advantages for targeted studies of a few particular metabolites, they are not readily formattable for large-scale global assessment of eicosanoid in vivo metabolism. A limitation with the current platform is that proposed pro-resolving lipid mediators are not included, but that is currently not possible because little is known about their in vivo metabolism in humans. Our workflow encompasses the majority of the eicosanoid pathways that have established clinical or physiological functions (Fig. 1). In particular, we have added the compound, 13,14-dihydro-15-keto-PGF2α, which enables us to monitor the PGF2α pathway. This improved workflow has been semi-automated using an SPE automation system, includes shortened chromatographic run-times, only requires 1.4 ml of urine for all analyses, and does not involve an enzymatic hydrolysis step. In addition, all three methods have been harmonized to use the same flow rate, column temperature, ionization polarity, and mobile phase. This simplifies the procedure, reducing both analysis time and costs compared with other methods (6, 21, 35, 43–45, 47). The use of specific gravity for the normalization eliminates the need to measure creatinine, which, while straightforward, adds an extra step to the workflow. The minimal required volume for analysis with the complete workflow simplifies planning of clinical studies because the same volume can be stored for all samples using 2 ml cryotubes, which consume less freezer space for biobanking. Lastly, the use of the fortified laboratory reference material enables the monitoring of method performance over time and stitching together data from independent studies for integrative meta-analyses.

In conclusion, the developed urinary eicosanoid profiling workflow provides an integrative signal of systemic inflammatory processes and is informative for mechanistic insight into numerous pathologies. The current platform improves on previous methods in terms of simplicity, metabolic coverage, and precision. Monitoring eicosanoid levels in urine is practical for multiple reasons including the stability of eicosanoid metabolites during multiple freeze/thaw cycles and deep frozen in urine for at least 1 year, as well as the suitability of urine for clinical study collection protocols (e.g., pediatric and repeat sampling). In addition, the developed panel of urinary eicosanoids is also pharmacologically relevant, as was shown by the replication of similar eicosanoid release profiles following both local and whole lung exposure. The developed platform covers the major eicosanoid urinary metabolites including the prostanoids, leukotrienes, and isoprostanes. The methods presented herein enable the monitoring of systemic end-point markers of inflammation and oxidative stress and are sufficiently repeatable and precise for applications in large population-based studies and clinical investigations.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Abbreviations:

- COX

- cyclooxygenase

- CysLT

- cysteinyl leukotriene

- LOQ

- limit of quantitation

- LOX

- lipoxygenase

- LT

- leukotriene

- PG

- prostaglandin

- PGMsIPs

- prostaglandin metabolites and isoprostanes

- PLA2

- phospholipase A2

- RNS

- reactive nitrogen species

- ROS

- reactive oxygen species

- %RSD

- percent relative standard deviation

- QC

- quality control

- WADA

- World Anti-Doping Agency

This work was supported by Swedish Heart-Lung Foundation Grants 20170603 and 20170734, Swedish Research Council Grant 2016-02798, AllerGen National Center of Excellence Grant GxE4, Stockholm County Council Research Funds (ALF), and the Centre for Allergy Research Highlights Asthma Markers of Phenotype (ChAMP) consortium, which is funded by the Swedish Foundation for Strategic Research, the Karolinska Institutet, AstraZeneca Canada and Science for Life Laboratory Joint Research Collaboration, and the Vårdal Foundation. C.E.W. was supported by Swedish Heart-Lung Foundation Grant 20180290. C.C. was supported by the Canada Research Chairs program and the AstraZeneca Canada Chair in Occupational and Environmental Lung Disease.

The online version of this article (available at http://www.jlr.org) contains a supplement.

REFERENCES

- 1.Funk C. D. 2001. Prostaglandins and leukotrienes: advances in eicosanoid biology. Science. 294: 1871–1875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dennis E. A., and Norris P. C.. 2015. Eicosanoid storm in infection and inflammation. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 15: 511–523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shimizu T. 2009. Lipid mediators in health and disease: enzymes and receptors as therapeutic targets for the regulation of immunity and inflammation. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 49: 123–150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Milne G. L., Yin H., Hardy K. D., Davies S. S., and Roberts L. J.. 2011. Isoprostane generation and function. Chem. Rev. 111: 5973–5996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mitchell J. A., Knowles R. B., Kirkby N. S., Reed D. M., Edin M. L., White W. E., Chan M. V., Longhurst H., Yaqoob M. M., Milne G. L., et al. . 2018. Kidney transplantation in a patient lacking cytosolic phospholipase A2 proves renal origins of urinary PGI-M and TX-M. Circ. Res. 122: 555–559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Song W-L., Wang M., Ricciotti E., Fries S., Yu Y., Grosser T., Reilly M., Lawson J. A., and FitzGerald G. A.. 2008. Tetranor PGDM, an abundant urinary metabolite reflects biosynthesis of prostaglandin D2 in mice and humans. J. Biol. Chem. 283: 1179–1188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hagan J. B., Laidlaw T. M., Divekar R., O’Brien E. K., Kita H., Volcheck G. W., Hagan C. R., Lal D., Teaford H. G., Erwin P. J., et al. . 2017. Urinary leukotriene E4 to determine aspirin intolerance in asthma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. Pract. 5: 990–997.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.King C. C., Piper M. E., Gepner A. D., Fiore M. C., Baker T. B., and Stein J. H.. 2017. Longitudinal impact of smoking and smoking cessation on inflammatory markers of cardiovascular disease risk. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 37: 374–379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Szczeklik W., Stodółkiewicz E., Rzeszutko M., Tomala M., Chrustowicz A., Żmudka K., and Sanak M.. 2016. Urinary 11-dehydro-thromboxane B2 as a predictor of acute myocardial infarction outcomes: results of Leukotrienes and Thromboxane in Myocardial Infarction (LTIMI) study. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 5: e003702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lazarinis N., Bood J., Gomez C., Kolmert J., Lantz A-S., Gyllfors P., Davis A., Wheelock C. E., Dahlén S-E., and Dahlén B.. 2018. Leukotriene E4 induces airflow obstruction and mast cell activation via the cysteinyl leukotriene type 1 receptor. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 142: 1080–1089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Inagaki S., Maeda S., Narita M., Nakamura T., Shimosawa T., Murata T., and Ohya Y.. 2018. Urinary PGDM, a prostaglandin D2 metabolite, is a novel biomarker for objectively detecting allergic reactions of food allergy. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 142: 1634–1636.e10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chadha V., Garg U., and Alon U. S.. 2001. Measurement of urinary concentration: a critical appraisal of methodologies. Pediatr. Nephrol. 16: 374–382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Montuschi P., Santini G., Valente S., Mondino C., Macagno F., Cattani P., Zini G., and Mores N.. 2014. Liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry measurement of leukotrienes in asthma and other respiratory diseases. J. Chromatogr. B Analyt. Technol. Biomed. Life Sci. 964: 12–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kolmert J., Fauland A., Fuchs D., Säfholm J., Gómez C., Adner M., Dahlén S. E., and Wheelock C. E.. 2018. Lipid mediator quantification in isolated human and guinea pig airways: an expanded approach for respiratory research. Anal. Chem. 90: 10239–10248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wolfer A. M., Gaudin M., Taylor-Robinson S. D., Holmes E., and Nicholson J. K.. 2015. Development and validation of a high-throughput ultrahigh-performance liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry approach for screening of oxylipins and their precursors. Anal. Chem. 87: 11721–11731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pedersen T. L., and Newman J. W.. 2018. Establishing and performing targeted multi-residue analysis for lipid mediators and fatty acids in small clinical plasma samples. Methods Mol. Biol. 1730: 175–212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Daham K., James A., Balgoma D., Kupczyk M., Billing B., Lindeberg A., Henriksson E., FitzGerald G. A., Wheelock C. E., Dahlen S-E., et al. . 2014. Effects of selective COX-2 inhibition on allergen-induced bronchoconstriction and airway inflammation in asthma. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 134: 306–313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Strassburg K., Huijbrechts A. M. L., Kortekaas K. A., Lindeman J. H., Pedersen T. L., Dane A., Berger R., Brenkman A., Hankemeier T., Van Duynhoven J., et al. . 2012. Quantitative profiling of oxylipins through comprehensive LC-MS/MS analysis: application in cardiac surgery. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 404: 1413–1426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rockwell H. E., Gao F., Chen E. Y., McDaniel J., Sarangarajan R., Narain N. R., and Kiebish M. A.. 2016. Dynamic assessment of functional lipidomic analysis in human urine. Lipids. 51: 875–886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brannan J. D., Bood J., Alkhabaz A., Balgoma D., Otis J., Delin I., Dahlén B., Wheelock C. E., Nair P., Dahlén S-E., et al. . 2015. The effect of omega-3 fatty acids on bronchial hyperresponsiveness, sputum eosinophilia, and mast cell mediators in asthma. Chest. 147: 397–405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Balgoma D., Larsson J., Rokach J., Lawson J. A., Daham K., Wheelock C. E., Dahlén B., Dahlén S-E., and Wheelock C. E.. 2013. Quantification of lipid mediator metabolites in human urine from asthma patients by electrospray ionization mass spectrometry: controlling matrix effects. Anal. Chem. 85: 7866–7874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sasaki A., Fukuda H., Shiida N., Tanaka N., Furugen A., Ogura J., Shuto S., Mano N., and Yamaguchi H.. 2015. Determination of ω-6 and ω-3 PUFA metabolites in human urine samples using UPLC/MS/MS. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 407: 1625–1639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA). 2014. ISTI: Urine Sample Collection Guidelines. Accessed November 10, 2017, at https://www.wada-ama.org/sites/default/files/resources/files/wada_guidelines_urine_sample_collection_2014_v1.0_en.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 24.World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA). 2016. WADA Technical Document – TD2016EAAS. Endogenous Anabolic Androgenic Steroids: Measurement and Reporting. Accessed May 15, 2017, at https://www.wada-ama.org/sites/default/files/resources/files/wada-td2016eaas-eaas-measurement-and-reporting-en.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fraselle S., De Cremer K., Coucke W., Glorieux G., Vanmassenhove J., Schepers E., Neirynck N., Van Overmeire I., Van Loco J., Van Biesen W., et al. . 2015. Development and validation of an ultra-high performance liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry method to measure creatinine in human urine. J. Chromatogr. B Analyt. Technol. Biomed. Life Sci. 988: 88–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Medina S., Miguel-Elízaga I. D., Oger C., Galano J. M., Durand T., Martínez-Villanueva M., Castillo M. L., Villegas-Martínez I., Ferreres F., Martínez-Hernández P., et al. . 2015. Dihomo-isoprostanes-nonenzymatic metabolites of AdA-are higher in epileptic patients compared to healthy individuals by a new ultrahigh pressure liquid chromatography-triple quadrupole-tandem mass spectrometry method. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 79: 154–163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Carlsten C., Blomberg A., Pui M., Sandstrom T., Wong S. W., Alexis N., and Hirota J.. 2016. Diesel exhaust augments allergen-induced lower airway inflammation in allergic individuals: a controlled human exposure study. Thorax. 71: 35–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Birger N., Gould T., Stewart J., Miller M. R., Larson T., and Carlsten C.. 2011. The Air Pollution Exposure Laboratory (APEL) for controlled human exposure to diesel exhaust and other inhalants: characterization and comparison to existing facilities. Inhal. Toxicol. 23: 219–225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cone E. J., Caplan Y. H., Moser F., Robert T., Shelby M. K., and Black D. L.. 2009. Normalization of urinary drug concentrations with specific gravity and creatinine. J. Anal. Toxicol. 33: 1–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Narayanan S., and Appleton H. D.. 1980. Creatinine: a review. Clin. Chem. 26: 1119–1126. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sauvé J. F., Lévesque M., Huard M., Drolet D., Lavoué J., Tardif R., and Truchon G.. 2015. Creatinine and specific gravity normalization in biological monitoring of occupational exposures. J. Occup. Environ. Hyg. 12: 123–129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Xia Y., Wong L. Y., Bunker B. C., and Bernert J. T.. 2014. comparison of creatinine and specific gravity for hydration corrections on measurement of the tobacco-specific nitrosamine 4-(methylnitrosamino)-1-(3-pyridyl)-1-butanol (NNAL) in urine. J. Clin. Lab. Anal. 28: 353–363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Singh G. K., Balzer B. W., Desai R., Jimenez M., Steinbeck K. S., and Handelsman D. J.. 2015. Requirement for specific gravity and creatinine adjustments for urinary steroids and luteinizing hormone concentrations in adolescents. Ann. Clin. Biochem. 52: 665–671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Burchell B., and Coughtrie M. W. H.. 1989. UDP-glucuronosyltransferases. Pharmacol. Ther. 43: 261–289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fu J., Schoeman J. C., Harms A. C., van Wietmarschen H. A., Vreeken R. J., Berger R., Cuppen B. V. J., Lafeber F. P. J. G., van der Greef J., and Hankemeier T.. 2016. Metabolomics profiling of the free and total oxidised lipids in urine by LC-MS/MS: application in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 408: 6307–6319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.US Department of Health and Human Services, Food and Drug Administration, Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (CDER), and Center for Veterinary Medicine (CVM). 2018. Bioanalytical Method Validation: Guidance for Industry. Accessed July 20, 2018, at https://www.fda.gov/downloads/drugs/guidances/ucm070107.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kumlin M., Dahlén B., Björck T., Zetterström O., Granström E., and Dahlén S. E.. 1992. Urinary excretion of leukotriene E4 and 11-dehydro-thromboxane B2 in response to bronchial provocations with allergen, aspirin, leukotriene D4, and histamine in asthmatics. Am. Rev. Respir. Dis. 146: 96–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sladek K., Dworski R., Fitzgerald G. A., Buitkus K. L., Block F. J., Marney S. R., and Sheller J. R.. 1990. Allergen-stimulated release of thromboxane a2 and leukotriene E4 in humans: effect of indomethacin. Am. Rev. Respir. Dis. 141: 1441–1445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bochenek G., Nizankowska E., Gielicz A., Swierczynska M., and Szczeklik A.. 2004. Plasma 9alpha,11beta-PGF2, a PGD2 metabolite, as a sensitive marker of mast cell activation by allergen in bronchial asthma. Thorax. 59: 459–464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lupinetti M. D., Sheller J. R., Catella F., and Fitzgerald G. A.. 1989. Thromboxane biosynthesis in allergen-induced bronchospasm: evidence for platelet activation. Am. Rev. Respir. Dis. 140: 932–935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Manning P. J., Stevens W. H., Cockcroft D. W., and O’Byrne P. M.. 1991. The role of thromboxane in allergen-induced asthmatic responses. Eur. Respir. J. 4: 667–672. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dworski R., Jackson Roberts Ii L., Murray J. J., Morrow J. D., Hartert T. V., and Sheller J. R.. 2001. Assessment of oxidant stress in allergic asthma by measurement of the major urinary metabolite of F2-isoprostane, 15-F2t-IsoP (8-iso-PGF2alpha). Clin. Exp. Allergy. 31: 387–390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Davies S. S., Zackert W., Luo Y., Cunningham C. C., Frisard M., and Roberts L. J.. 2006. Quantification of dinor, dihydro metabolites of F2-isoprostanes in urine by liquid chromatography/tandem mass spectrometry. Anal. Biochem. 348: 185–191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Armstrong M., Liu A. H., Harbeck R., Reisdorph R., Rabinovitch N., and Reisdorph N.. 2009. Leukotriene-E4 in human urine: Comparison of on-line purification and liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry to affinity purification followed by enzyme immunoassay. J. Chromatogr. B Analyt. Technol. Biomed. Life Sci. 877: 3169–3174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Syslová K., Kačer P., Kuzma M., Najmanová V., Fenclová Z., Vlčková Š., Lebedová J., and Pelclová D.. 2009. Rapid and easy method for monitoring oxidative stress markers in body fluids of patients with asbestos or silica-induced lung diseases. J. Chromatogr. B Analyt. Technol. Biomed. Life Sci. 877: 2477–2486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Prasain J. K., Arabshahi A., Taub P. R., Sweeney S., Moore R., Sharer J. D., and Barnes S.. 2013. Simultaneous quantification of F2-isoprostanes and prostaglandins in human urine by liquid chromatography tandem-mass spectrometry. J. Chromatogr. B Analyt. Technol. Biomed. Life Sci. 913–914: 161–168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sterz K., Scherer G., and Ecker J.. 2012. A simple and robust UPLC-SRM/MS method to quantify urinary eicosanoids. J. Lipid Res. 53: 1026–1036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.