Abstract

Brachial–ankle pulse wave velocity (baPWV), as a marker of arterial stiffness, has been demonstrated to be associated with blood pressure (BP) and onset of hypertension. However, little information is available on the associations between baPWV and BP indices [systolic BP (SBP), diastolic BP (DBP), pulse pressure (PP), mean arterial pressure (MAP)] in treated hypertensive patients. We aimed to assess the associations between BP indices and baPWV. In this cross-sectional study, 14,598 hypertensive patients from China Stroke Primary Prevention Trial (CSPPT) at the exit visit of the trial were analyzed. Elevated baPWV was defined as ≥18.3 m/s. Multivariate linear and logistic regression analyses were performed to evaluate the associations of BP indices with baPWV and elevated baPWV. Moreover, the smooth curve fitting (penalized spline method) was conducted. Multivariate linear regression analyses showed that continuous SBP, DBP, PP and MAP were independently and positively associated with baPWV (β = 0.081, 0.084, 0.078 and 0.115, respectively, all P < 0.001). Compared with controlled SBP group (<140 mm Hg), uncontrolled SBP (≥140 mm Hg) was significantly associated with higher baPWV [β = 2.234, 95% confidence interval (CI): 2.137–2.332]. Similarly, compared with controlled DBP group (<90 mm Hg), uncontrolled DBP (≥90 mm Hg) was significantly associated with higher baPWV (β = 1.466, 95%CI: 1.341–1.590). Multiple logistic analyses also showed that SBP, DBP, PP and MAP were significantly and positively associated with elevated baPWV (OR = 1.056, 1.049, 1.052, and 1.075, respectively, all P < 0.001). The fully-adjusted smooth curve fitting presented a linear association between BP indices with baPWV. In conclusion, among treated hypertensive patients, SBP, DBP, PP and MAP levels were independently and positively associated with baPWV and elevated baPWV, suggesting that baPWV might be a way to predict uncontrolled BP.

Subject terms: Interventional cardiology, Hypertension

Introduction

It is well-known that increased arterial stiffness is closely related to early vascular damage, cardiovascular disease (CVD) and mortality1–3. Brachial-ankle pulse wave velocity (baPWV) is available as a noninvasive measure of arterial stiffness4,5. The European Society of Hypertension (ESH) and of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) recommended that baPWV should be a routine examination for hypertensive patients6. Hypertension is regarded as a public health challenge worldwide and is the leading modifiable risk factor for CVD7,8. Recent studies have showed that the control rate of hypertension is still low, although the awareness and treatment of hypertension have increased9. Poor blood pressure (BP) control further lead to target organ damage10. Therefore, it is important to identify the factors that influence individual response to anti-hypertensive treatment.

Indeed growing evidence has established the associations of baPWV with BP and onset of hypertension11–16. However, obvious conflicting results could be found among those reports. For instance, several epidemiological studies reported that BP indices was positively associated with baPWV11–14. In contrast, some studies showed that diastolic BP (DBP) was not associated with baPWV15. In addition, some studies indicated that DBP was negitvely associated with PWV16. These conflicting results might be attributed to the differences in cohort characteristics, sample size, and adjustment of confounders. Most of these previous studies have only discussed the association between BP and baPWV in general population. Uncertainty remains regarding the associations between BP indices [systolic BP (SBP), DBP, pulse pressure (PP), mean arterial pressure (MAP)] and baPWV because of limited data in treated hypertensive patients.

Therefore, our study aimed to assess the associations between BP indices and baPWV in a large sample of populations with treated hypertension.

Methods

Subject population and design

Our present study was a subset of the China Stroke Primary Prevention Trial (CSPPT)17. Briefly, the CSPPT is a large community-based, randomized, multicenter, double-blind, and actively controlled trial with a total of 20,702 hypertensive participants, conducted from May 2008 to August 2013 in Jiangsu and Anhui provinces of China. It was designed to confirm that enalapril maleate and folic acid tablets combined was more effective in preventing stroke among patients with hypertension when compared with enalapril maleate alone. Participants were scheduled for a visit (the first visit) after a 3-week run-in treatment period, and then were followed-up every 3 months until completion of the trial. Each visit involved recording BPs, heart rate, trial medication compliance, concomitant use of other medications, adverse events, and study outcome events. Details regarding inclusion/exclusion criteria, treatment assignment and outcome measures of the trial have been described in previous publications17 and shared on a related website (http://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT00794885). The study was approved by the ethics committee of the Nanfang Hospital, Guangzhou, China. The patients provided a written informed consent under the premises of the original CSPPT trial, including the possibility of post hoc analyses. This trial was registered with Clinicaltrials.gov (#NCT00794885). All methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations.

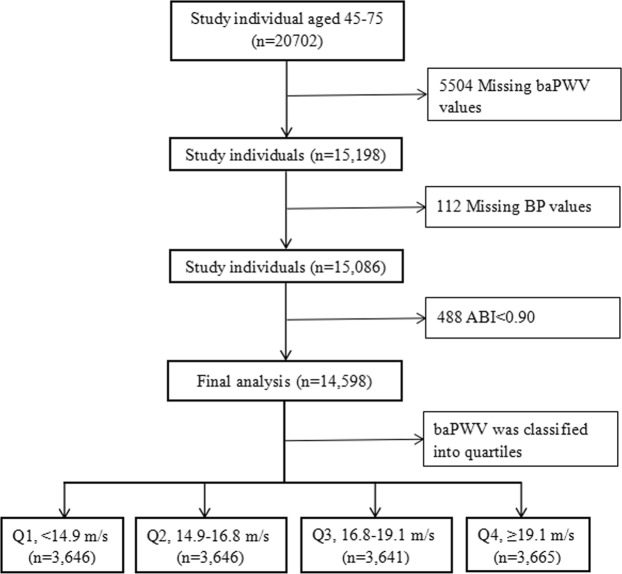

At the exit visit of the trial, each participant was accpeted BaPWV measurement. In total, 20,702 eligible hypertensive participants were enrolled. Next, we selected participants according to the exclusion criteria listed below: missing baPWV values (n = 5504), missing BP values (n = 112), and ankle brachial index (ABI) < 0.90 (n = 488).

Data collection

Brachial–ankle pulse wave velocity (baPWV)

BaPWV was automatically measured by PWV/ABI instruments (form PWV/ABI, BP-203RPE; Omron-Colin, Japan) as previously described by trained volunteers from medical colleges18. Briefly, occlusion and monitoring cuffs matched with oscillometric sensors were wrapped around subjects’ arms and the ankles, and pulse volume wave forms of the bilateral brachial and posterior tibial arteries were recorded simultaneously to determine the time interval between the initial increase in brachial and tibial waveforms (the transit time, Tba). The transmission distance from the brachium to ankle was calculated according to body height. The path length from the suprasternal notch to the brachium (Lb) was obtained using the following equation: Lb = 0.2159 × height of the patient (cm) − 2.0734. The path length from the suprasternal notch to the ankle (La) was obtained using the following equation: La = 0.8129 × height of the patient (cm) + 12.328. And the baPWV value was calculated as the ratio of transmission distance from the brachium to ankle divided by the transit time: baPWV = (La − Lb)/Tba. The maximum of the right and left-side baPWV values was used for analysis. The validation of this automatic device and its reproducibility have been previously published2.

BP and rest heart rate (RHR)

BP and RHR was measured at the last follow up visit with the subject in the sitting position after having rested for more than 5 minutes, and using an electronic sphygmomanometer (Omron; Dalian, China). Three consecutive measurements were obtained on the right arm, with 1-minute intervals between each. Then SBP, DBP, and RHR were calculated as the mean of three independent measures. MAP was calculated as [(2 × DBP) + SBP] / 3. PP was calculated as SBP – DBP. Uncontrolled SBP was defined as a SBP of ≥140 mm Hg and uncontrolled DBP was defined as a DBP of ≥90 mm Hg among treated hypertensive individuals.

Covariables

We selected these covariates on the basis of their associations with baPWV. Continuous variables included age (years), body mass index (BMI, kg/m2), serum homocysteine (hcy, μmol/L), fasting lipids [total cholesterol (TC, mmol/L), high-density lipoprotein-cholesterol (HDL-C, mmol/L), and triglycerides (TG, mmol/L)], fasting plasma glucose (FPG, mmol/L), creatinine (μmol/L), and uric acid (μmol/L). Categorical variables consisted of sex (male, female), Center (Lianyungang, Anqing), smoking (never smoking, former smoking or current smoking), alcohol consumption (never drinking, former drinking or current drinking), treatment group (enalapril, enalapril-folic acid), comorbidities (stroke, diabetes), medication use (combined with other antihypertensive drugs, lipid-lowering drugs and glucose-lowering drugs), methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase (MTHFR) C677T (rs1801133) polymorphism (CC, CT, TT). BMI was calculated as body weight in kilograms divided by the square of height in meters (kg/m2). Laboratory data were measured using automatic clinical analyzers (Beckman Coulter) at the core laboratory of the National Clinical Research Center for Kidney Disease, Nanfang Hospital, Guangzhou, China. MTHFR C677T polymorphisms were detected on an ABI Prism 7900HT sequence detection system (Life Technologies) using the TaqMan assay.

Statistical analysis

Data are presented as mean ± SD for continuous variables and as frequency (%) for categorical variables. The population characteristics by baPWV quartiles were compared using ANOVA tests (continuous variables), or χ2 tests (categorical variables), accordingly. Taking BP indices (SBP, DBP, MAP, and PP) as independent variables and baPWV as an dependent variable, multivariate linear regression analyses were used to assess the β and 95% confidence interval (CI) of baPWV being associated with BP indices (SBP, DBP, MAP, and PP) adjustment for major covariables including age, sex, center, MTHFR C677T polymorphisms, treatment group, antihypertensive treatment, BMI, smoking status, alcohol consumption, RHR, TC, HDL-C, triglycerides, FPG, hcy, creatinine, uric acid. Meanwhile, Toshiaki Ohkuma et al.19 proposed that the optimal cutoff value of baPWV for cardiovascular disease in patients with hypertension was 18.3 m/s. Therefore, the elevated baPWV was defined as ≥18.3 m/s. We investigated the associations of BP indices with elevated baPWV using multivariate binary logistic regression analysis. BP indices were evaluated using models for both continuous and categorical variables according to clinical normal values and quartiles. The lowest level of each BP indice was considered as a reference group. To ensure the robustness of data analysis, we also did the sensitivity analyses. We performed tests for linear trend by entering the median value of each quartiles of BP indices as continuous variables in the models. Moreover, to further characterize the shape of the associations between BP indices and baPWV, we used the smooth curve fitting (penalized spline method). Interaction and stratified analyses were performed to evaluate whether covariates influenced the associations between BP indices and baPWV.

All the analyses were performed using the statistical package R (http://www.R-project.org, The R Foundation) and Empower (R) (www.empowerstats.com; X&Y Solutions, Inc., Boston, MA). A 2-tailed P < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Results

Characteristics of the subjects

Based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria, a total of 14,598 participants (mean age: 64.4 ± 7.4 years; 40.2% males) at the exit visit were selected for final data analysis (Fig. 1). Of the participants, 5.1% had experienced a stroke and 2.3% had diabetes. The mean (SD) values for SBP, DBP, PP, and MAP were 135.4 (17.4) mmHg, 81.9 (10.9) mmHg, 53.5 (15.3) mmHg, and 99.7 (11.3) mmHg, respectively. The mean baPWV was 17.3 (3.4) m/s. The distributions of selective participants sociodemographic characteristics and other covariates according to baPWV quartiles (<14.9, 14.9–16.8, 16.8–19.1 and ≥19.1 m/s) are presented in Table 1. Compared with participants with baPWV in the lower quartiles (Q1–Q3), participants with baPWV in the highest quartile (Q4) had higher values in age, RHR, SBP, DBP, MAP, PP, FPG, TC, TG, hcy, uric acid, creatinine and higher rates of stroke, diabetes, antihypertensive and glucose-lowering drugs (all P < 0.01). In contrast, populations in the highest baPWV group had significantly low BMI value. No significant differences were found between the 4 groups in terms of sex, MTHFR genotype distribution, alcohol consumption, HDL-cholesterol, lipid-lowering drugs or treatment group (all P > 0.05).

Figure 1.

Flow chart of study participants. Abbreviations: baPWV, brachial–ankle pulse wave velocity; BP, blood pressure; ABI, ankle brachial index.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of study participants.

| Characteristics* | Total | BaPWV quartiles, m/s | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Q1(<14.9) | Q2(14.9–16.8) | Q3(16.8–19.1) | Q4(≥19.1) | P value | ||

| N (%) | 14598 | 3646 | 3646 | 3641 | 3665 | |

| Male, N (%) | 5864 (40.2) | 1494 (41.0) | 1486 (40.8) | 1459 (40.1) | 1425 (38.9) | 0.255 |

| Age, years | 64.4 ± 7.4 | 60.4 ± 6.7 | 63.1 ± 6.9 | 65.4 ± 6.8 | 68.6 ± 6.4 | <0.001 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 24.9 ± 3.8 | 25.5 ± 3.9 | 25.1 ± 3.8 | 24.7 ± 3.8 | 24.4 ± 3.7 | <0.001 |

| RHR, bpm | 76.8 ± 11.3 | 73.8 ± 10.1 | 75.5 ± 10.5 | 77.2 ± 11.1 | 80.8 ± 12.4 | <0.001 |

| baPWV, m/s | 17.3 ± 3.4 | 13.5 ± 1.0 | 15.8 ± 0.6 | 17.8 ± 0.7 | 21.9 ± 2.6 | <0.001 |

| Center, N (%) | <0.001 | |||||

| Lianyungang | 3497 (24.0) | 689 (18.9) | 869 (23.8) | 927 (25.5) | 1012 (27.6) | |

| Anqing | 11101 (76.0) | 2957 (81.1) | 2777 (76.2) | 2714 (74.5) | 2653 (72.4) | |

| MTHFR C677T polymorphisms, N (%) | 0.182 | |||||

| CC | 3963 (27.1) | 933 (25.6) | 984 (27.0) | 1028 (28.2) | 1018 (27.8) | |

| CT | 7144 (48.9) | 1817 (49.8) | 1781 (48.8) | 1780 (48.9) | 1766 (48.2) | |

| TT | 3491 (23.9) | 896 (24.6) | 881 (24.2) | 833 (22.9) | 881 (24.0) | |

| Smoking status, N (%) | 0.002 | |||||

| Never | 9844 (67.7) | 2483 (68.3) | 2444 (67.2) | 2462 (67.9) | 2455 (67.3) | |

| Former | 1641 (11.3) | 371 (10.2) | 375 (10.3) | 447 (12.3) | 448 (12.3) | |

| Current | 3065 (21.1) | 783 (21.5) | 816 (22.4) | 719 (19.8) | 747 (20.5) | |

| Alcohol consumption, N (%) | 0.201 | |||||

| Never | 9878 (70.2) | 2454 (69.8) | 2437 (69.5) | 2498 (71.1) | 2489 (70.5) | |

| Former | 972 (6.9) | 234 (6.7) | 228 (6.5) | 259 (7.4) | 251 (7.1) | |

| Current | 3219 (22.9) | 829 (23.6) | 839 (23.9) | 758 (21.6) | 793 (22.4) | |

| BP indices, mm Hg | ||||||

| SBP | 135.4 ± 17.4 | 126.2 ± 14.3 | 132.9 ± 14.8 | 137.2 ± 15.9 | 145.1 ± 18.5 | <0.001 |

| DBP | 81.9 ± 10.9 | 81.2 ± 10.3 | 81.9 ± 10.6 | 81.7 ± 10.9 | 82.8 ± 11.6 | <0.001 |

| PP | 53.5 ± 15.3 | 45.0 ± 12.3 | 51.1 ± 13.1 | 55.5 ± 14.0 | 62.2 ± 16.0 | <0.001 |

| MAP | 99.7 ± 11.3 | 96.2 ± 10.2 | 98.9 ± 10.5 | 100.2 ± 11.0 | 103.6 ± 12.1 | <0.001 |

| Laboratory results | ||||||

| FPG, mmol/L | 6.2 ± 1.9 | 6.0 ± 1.5 | 6.1 ± 1.8 | 6.3 ± 2.0 | 6.5 ± 2.4 | <0.001 |

| TC, mmol/L | 5.3 ± 1.1 | 5.2 ± 1.0 | 5.3 ± 1.1 | 5.3 ± 1.1 | 5.4 ± 1.1 | <0.001 |

| HDL-C, mmol/L | 1.3 ± 0.3 | 1.3 ± 0.3 | 1.3 ± 0.3 | 1.3 ± 0.3 | 1.3 ± 0.3 | 0.477 |

| TG, mmol/L | 1.8 ± 1.5 | 1.7 ± 1.3 | 1.7 ± 1.3 | 1.8 ± 1.6 | 1.9 ± 1.5 | <0.001 |

| Hcy, μmol/L | 13.5 ± 7.1 | 12.9 ± 7.9 | 13.2 ± 5.7 | 13.5 ± 6.0 | 14.4 ± 8.4 | <0.001 |

| Uric acid, μmol/L | 329.3 ± 89.7 | 323.5 ± 85.8 | 328.3 ± 88.7 | 329.8 ± 90.5 | 335.4 ± 93.2 | <0.001 |

| Creatinine, μmol/L | 68.7 ± 26.8 | 67.9 ± 24.6 | 68.2 ± 21.8 | 69.3 ± 34.8 | 69.5 ± 24.3 | 0.032 |

| Comorbidities, N (%) | ||||||

| Stroke | 739 (5.1) | 141 (3.9) | 172 (4.7) | 203 (5.6) | 223 (6.1) | <0.001 |

| Diabetes | 333 (2.3) | 44 (1.2) | 83 (2.3) | 83 (2.3) | 123 (3.4) | <0.001 |

| Medications use, N (%) | ||||||

| Antihypertensive drugs | 14137 (97.2) | 3505 (96.3) | 3542 (97.4) | 3526 (97.2) | 3564 (97.7) | 0.007 |

| Lipid-lowering drugs | 212 (1.5) | 58 (1.6) | 62 (1.7) | 45 (1.2) | 47 (1.3) | 0.343 |

| Glucose-lowering drugs | 830 (5.8) | 133 (3.8) | 189 (5.3) | 239 (6.8) | 269 (7.5) | <0.001 |

| Treatment group, N (%) | 0.258 | |||||

| Enalapril | 7322 (50.2) | 1791 (49.1) | 1870 (51.3) | 1808 (49.7) | 1853 (50.6) | |

| Enalapril-folic acid | 7276 (49.8) | 1855 (50.9) | 1776 (48.7) | 1833 (50.3) | 1812 (49.4) | |

*Data are presented as number (%) or mean ± standard deviation.

Abbreviations: BMI = Body mass index; RHR = resting heart rate; BaPWV = Brachial-ankle pulse wave velocity; MTHFR = methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase; BP = blood pressure; SBP = systolic blood pressure; DBP = diastolic blood pressure; MAP = mean arterial pressure; PP = pulse pressure; FPG = fasting plasma glucose; TC = Total cholesterol; HDL-C = high density lipoprotein cholesterol; TG = triglycerides; Hcy = homocysteine.

Association between BP indices and baPWV

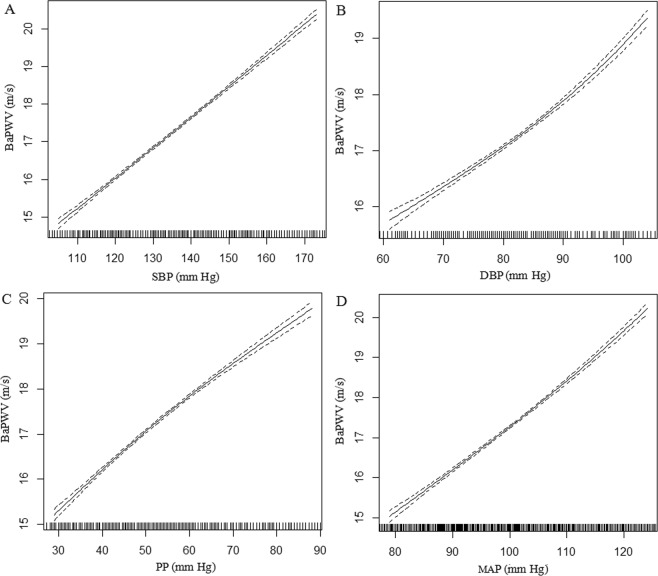

The associations of baPWV with BP indices assessed by multivariate linear regression analyses are listed in Table 2. In the crude model, continuous SBP, DBP, PP and MAP were significantly and positively associated with baPWV (β = 0.081, 0.024, 0.093 and 0.079, respectively, all P < 0.001). In addition, after adjustment for all confounding factors including age, sex, center, MTHFR C677T polymorphisms, treatment group, antihypertensive treatment, BMI, smoking status, alcohol consumption, RHR, TC, HDL-C, TG, FPG, creatinine, hcy, and uric acid, all BP indices were independently and positively associated with baPWV (β = 0.081, 0.084, 0.078 and 0.115, respectively, all P < 0.001). BP indices were also evaluated for categorical variables according to clinical normal values and quartiles. Compared with controlled SBP group (<140 mm Hg), uncontrolled SBP (≥140 mm Hg) was significantly associated with higher baPWV (β = 2.234, 95%CI: 2.137–2.332, P < 0.001). Similarly, compared with controlled DBP group (<90 mm Hg), uncontrolled DBP (≥90 mm Hg) was significantly associated with higher baPWV (β = 1.466, 95%CI: 1.341–1.590, P < 0.001). Patients with higher PP levels (≥40 mmHg) had higher baPWV (β = 1.888, 95%CI: 1.754–2.022, P < 0.001). Compared with normal MAP levels (70–105 mmHg), high MAP levels (≥105 mmHg) were positively associated with baPWV (β = 2.080, 95%CI: 1.973–2.187, P < 0.001), while low MAP levels (<70 mmHg) were negatively associated with baPWV (β = −3.224, 95%CI: −4.235–2.212, P < 0.001). When BP indices were classified into quartiles, we observed a significant and progressive increase in baPWV with BP quartiles (all P for trend < 0.001), suggesting a dose-dependent increase in baPWV with BP indices. Further analyses using smooth curve fitting (penalized spline method) confirmed that the associations of BP indices with baPWV were linear (Fig. 2).

Table 2.

Associations of Brachial-ankle pulse wave velocity with BP indices.

| Variables | N | Mean ± SD | Crude model | Adjusted model* | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β (95%CI) | P value | β (95%CI) | P value | |||

| SBP, mmHg | ||||||

| Continuous | 14598 | 17.3 ± 3.4 | 0.081 (0.078, 0.084) | <0.001 | 0.081 (0.079, 0.084) | <0.001 |

| Categories | ||||||

| <140 | 9091 | 16.4 ± 3.0 | Reference (0) | Reference (0) | ||

| ≥140 | 5507 | 18.8 ± 3.5 | 2.367 (2.260, 2.474) | <0.001 | 2.234 (2.137, 2.332) | <0.001 |

| Quartiles | ||||||

| Q1 (<123.3) | 3647 | 15.7 ± 2.8 | Reference (0) | Reference (0) | ||

| Q2 (123.3–134.0) | 3533 | 16.6 ± 2.9 | 0.976 (0.831, 1.122) | <0.001 | 1.080 (0.950, 1.210) | <0.001 |

| Q3 (134.0–145.3) | 3664 | 17.6 ± 3.1 | 1.931 (1.787, 2.075) | <0.001 | 1.951 (1.822, 2.081) | <0.001 |

| Q4 (≥145.3) | 3754 | 19.2 ± 3.6 | 3.500 (3.357, 3.644) | <0.001 | 3.447 (3.317, 3.577) | <0.001 |

| P for trend | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||

| DBP, mmHg | ||||||

| Continuous | 14598 | 17.3 ± 3.4 | 0.024 (0.019, 0.029) | <0.001 | 0.084 (0.079, 0.089) | <0.001 |

| Categories | ||||||

| <90 | 11300 | 17.2 ± 3.3 | Reference (0) | Reference (0) | ||

| ≥90 | 3298 | 17.7 ± 3.6 | 0.499 (0.367, 0.631) | <0.001 | 1.466 (1.341, 1.590) | <0.001 |

| Quartiles | ||||||

| Q1 (<74.7) | 3483 | 17.1 ± 3.2 | Reference (0) | Reference (0) | ||

| Q2 (74.7–81.3) | 3628 | 17.2 ± 3.3 | 0.055 (−0.103, 0.213) | 0.495 | 0.650 (0.509, 0.791) | <0.001 |

| Q3 (81.3–89.3) | 3835 | 17.2 ± 3.4 | 0.109 (−0.047, 0.265) | 0.171 | 1.138 (0.995, 1.282) | <0.001 |

| Q4 (≥89.3) | 3652 | 17.6 ± 3.6 | 0.513 (0.355, 0.670) | <0.001 | 2.139 (1.986, 2.293) | <0.001 |

| P for trend | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||

| PP, mmHg | ||||||

| Continuous | 14598 | 17.3 ± 3.4 | 0.093 (0.090, 0.096) | <0.001 | 0.078 (0.074, 0.081) | <0.001 |

| Categories | ||||||

| <40 | 2529 | 15.3 ± 2.6 | Reference (0) | Reference (0) | ||

| ≥40 | 12069 | 17.7 ± 3.4 | 2.419 (2.278, 2.559) | <0.001 | 1.888 (1.754, 2.022) | <0.001 |

| Quartiles | ||||||

| Q1 (<42.7) | 3640 | 15.5 ± 2.7 | Reference (0) | Reference (0) | ||

| Q2 (42.7–52.0) | 3605 | 16.7 ± 3.1 | 1.223 (1.079, 1.367) | <0.001 | 1.013 (0.878, 1.148) | <0.001 |

| Q3 (52.0–62.0) | 3583 | 17.7 ± 3.2 | 2.229 (2.085, 2.373) | <0.001 | 1.826 (1.689, 1.964) | <0.001 |

| Q4 (≥62.0) | 3770 | 19.1 ± 3.5 | 3.628 (3.486, 3.771) | <0.001 | 2.922 (2.781, 3.063) | <0.001 |

| P for trend | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||

| MAP, mmHg | ||||||

| Continuous | 14598 | 17.3 ± 3.4 | 0.079 (0.074, 0.084) | <0.001 | 0.115 (0.110, 0.119) | <0.001 |

| Categories | ||||||

| <70 | 35 | 14.9 ± 2.5 | −1.925 (−3.029,−0.820) | <0.001 | −3.224 (−4.235, −2.212) | <0.001 |

| 70–105 | 10209 | 16.8 ± 3.2 | Reference (0) | Reference (0) | ||

| ≥105 | 4354 | 18.3 ± 3.7 | 1.521 (1.403, 1.639) | <0.001 | 2.080 (1.973, 2.187) | <0.001 |

| Quartiles | ||||||

| Q1 (<92.2) | 3624 | 16.4 ± 3.0 | Reference (0) | Reference (0) | ||

| Q2 (92.2–99.1) | 3640 | 16.8 ± 3.2 | 0.474 (0.322, 0.626) | <0.001 | 0.918 (0.785, 1.051) | <0.001 |

| Q3 (99.1–106.7) | 3681 | 17.4 ± 3.3 | 1.076 (0.924, 1.227) | <0.001 | 1.712 (1.578, 1.847) | <0.001 |

| Q4 (≥106.7) | 3653 | 18.5 ± 3.7 | 2.127 (1.975, 2.279) | <0.001 | 3.101 (2.963, 3.240) | <0.001 |

| P for trend | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||

Abbreviations: CI = confidence interval; BP = blood pressure; SBP = systolic blood pressure; DBP = diastolic blood pressure; MAP = mean arterial pressure; PP = pulse pressure.

*Adjusted for age, sex, center, MTHFR C677T polymorphisms, treatment group, antihypertensive treatment, BMI, smoking status, and alcohol consumption, RHR, TC, HDL-C, TG, FPG, creatinine, hcy, uric acid.

Figure 2.

Association between BP indices and baPWV. (A) SBP and baPWV; (B) DBP and baPWV; (C) PP and baPWV; (D) MAP and baPWV. The smooth curve fitting presented linear associations between all BP indices and baPWV among participants with treated hypertension. The solid line and dashed line represent the estimated values and their corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CI). Abbreviations: baPWV, brachial–ankle pulse wave velocity; BP, blood pressure; SBP, systolic blood pressure; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; PP, pulse pressure; MAP, mean arterial pressure. Adjustment factors included age, sex, center, MTHFR C677T polymorphisms, treatment group, antihypertensive treatment, BMI, smoking status, and alcohol consumption, RHR, TC, HDL-cholesterol, TG, FPG, creatinine, homocysteine, uric acid.

Table 3 shows the associations between BP indices and elevated baPWV. In adjusted model, SBP, DBP, PP and MAP were independently and positively associated with elevated baPWV in treated hypertensive patients [odds ratio (OR) = 1.056, 1.049, 1.052, and 1.075, respectively, all P < 0.001]. Compared with SBP control group, uncontrolled SBP was significantly associated with increased prevalence of elevated baPWV (OR = 4.514, 95%CI: 3.808–4.531, P < 0.001). Similarly, uncontrolled DBP was associated with increased prevalence of elevated baPWV (OR = 2.261, 95%CI: 2.038–2.508, P < 0.001) compared with DBP control group. Also, P for trend for all BP indices in the all models was significant, indicating that BP indices were positively associated with elevated baPWV.

Table 3.

Associations between BP indices and elevated brachial-ankle pulse wave velocity

| Variables | Events (%) | Crude model | Adjusted model* | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95%CI) | P value | OR (95%CI) | P value | ||

| SBP, mmHg | |||||

| Continuous | 4739 (32.5) | 1.045 (1.043, 1.048) | <0.001 | 1.056 (1.053, 1.059) | <0.001 |

| Categories | |||||

| <140 | 2021 (22.2) | Reference (1) | Reference (1) | ||

| ≥140 | 2718 (49.4) | 3.409 (3.171, 3.665) | <0.001 | 4.154 (3.808, 4.531) | <0.001 |

| Quartiles | |||||

| Q1 (<123.3) | 570 (15.6) | Reference (1) | Reference (1) | ||

| Q2 (123.3–134.0) | 860 (24.3) | 1.737 (1.544, 1.954) | <0.001 | 2.111 (1.844, 2.417) | <0.001 |

| Q3 (134.0–145.3) | 1295 (35.3) | 2.951 (2.638, 3.301) | <0.001 | 3.824 (3.354, 4.361) | <0.001 |

| Q4 (≥145.3) | 2014 (53.7) | 6.248 (5.597, 6.975) | <0.001 | 9.364 (8.197, 10.698) | <0.001 |

| P for trend | <0.001 | <0.001 | |||

| DBP, mmHg | |||||

| Continuous | 4739 (32.5) | 1.008 (1.005, 1.011) | <0.001 | 1.049 (1.044, 1.053) | <0.001 |

| Categories | |||||

| <90 | 3586 (31.7) | Reference (1) | Reference (1) | ||

| ≥90 | 1153 (35.0) | 1.156 (1.065, 1.255) | <0.001 | 2.261 (2.038, 2.508) | <0.001 |

| Quartiles | |||||

| Q1 (<74.7) | 1109 (31.8) | Reference (1) | Reference (1) | ||

| Q2 (74.7–81.3) | 1144 (31.5) | 0.986 (0.892, 1.089) | 0.780 | 1.382 (1.229, 1.553) | <0.001 |

| Q3 (81.3–89.3) | 1226 (32.0) | 1.006 (0.912, 1.110) | 0.906 | 1.887 (1.675, 2.127) | <0.001 |

| Q4 (≥89.3) | 1260 (34.5) | 1.128 (1.022, 1.245) | 0.017 | 3.201 (2.811, 3.646) | <0.001 |

| P for trend | 0.016 | <0.001 | |||

| PP, mmHg | |||||

| Continuous | 4739 (32.5) | 1.054 (1.052, 1.057) | <0.001 | 1.052 (1.048, 1.055) | <0.001 |

| Categories | |||||

| <40 | 285 (11.3) | Reference (1) | Reference (1) | ||

| ≥40 | 4454 (36.9) | 4.605 (4.049, 5.238) | <0.001 | 4.148 (3.584, 4.800) | <0.001 |

| Quartiles | |||||

| Q1 (<42.7) | 470 (12.9) | Reference (1) | Reference (1) | ||

| Q2 (42.7–52.0) | 900 (25.0) | 2.244 (1.985, 2.537) | <0.001 | 2.140 (1.865, 2.457) | <0.001 |

| Q3 (52.0–62.0) | 1317 (36.8) | 3.920 (3.483, 4.412) | <0.001 | 3.629 (3.173, 4.150) | <0.001 |

| Q4 (≥62.0) | 2052 (54.4) | 8.056 (7.172, 9.048) | <0.001 | 6.953 (6.075, 7.957) | <0.001 |

| P for trend | <0.001 | <0.001 | |||

| MAP, mmHg | |||||

| Continuous | 4739 (32.5) | 1.038 (1.035, 1.042) | <0.001 | 1.075 (1.070, 1.080) | <0.001 |

| Categories | |||||

| <70 | 4 (11.4) | 0.333 (0.117, 0.943) | 0.038 | 0.152 (0.050, 0.457) | <0.001 |

| 70–105 | 2854 (28.0) | Reference (1) | Reference (1) | ||

| ≥105 | 1881 (43.2) | 1.960 (1.820, 2.111) | <0.001 | 3.407 (3.101, 3.743) | <0.001 |

| Quartiles | |||||

| Q1 (<92.2) | 826 (22.8) | Reference (1) | Reference (1) | ||

| Q2 (92.2–99.1) | 1032 (28.4) | 1.340 (1.206, 1.490) | <0.001 | 1.885 (1.664, 2.134) | <0.001 |

| Q3 (99.1–106.7) | 1238 (33.6) | 1.717 (1.548, 1.904) | <0.001 | 2.980 (2.630, 3.376) | <0.001 |

| Q4 (≥106.7) | 1643 (45.0) | 2.769 (2.502, 3.064) | <0.001 | 7.013 (6.149, 7.998) | <0.001 |

| P for trend | <0.001 | <0.001 | |||

Abbreviations: OR = odds ratio; CI = confidence interval; BP = blood pressure; SBP = systolic blood pressure; DBP = diastolic blood pressure; MAP = mean arterial pressure; PP = pulse pressure.

*Adjusted for age, sex, center, MTHFR C677T polymorphisms, treatment group, antihypertensive treatment, BMI, smoking status, and alcohol consumption, RHR, TC, HDL-C, TG, FPG, creatinine, hcy, uric acid.

Subgroup analysis

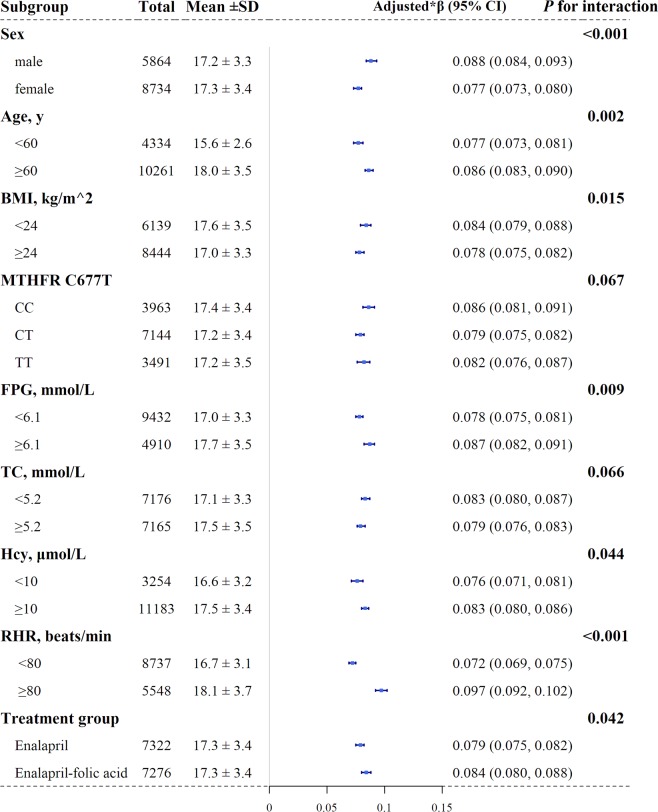

The role of other covariables on the association between BP indices and baPWV was further explored. Figure 3 shows the results of a subgroup analysis assessing the association of baPWV with SBP. Regardless of subgroup, SBP was positively associated with baPWV, and the effect was more significant in the following subgroups: male group (male: β = 0.088, 95%CI: 0.084–0.093; female: β = 0.077, 95%CI: 0.073–0.080, P for interaction < 0.001), aged ≥60 years group (<60 years: β = 0.077, 95%CI: 0.073–0.081; ≥60 years: β = 0.086, 95%CI: 0.083–0.090, P for interaction = 0.002), and in the BMI < 24 kg/m2 group (<24 kg/m2: β = 0.084, 95%CI: 0.079–0.088; ≥24 kg/m2: β = 0.078, 95%CI: 0.075–0.082, P for interaction = 0.015), FPG ≥ 6.1 mmol/L group (<6.1 mmol/L: β = 0.078, 95%CI: 0.075–0.081; ≥6.1 mmol/L: β = 0.087, 95%CI: 0.082–0.091, P for interaction = 0.009), hcy ≥10 μmol/L group (<10 μmol/L: β = 0.076, 95%CI: 0.071–0.081; ≥10 μmol/L: β = 0.083, 95%CI: 0.080–0.086, P for interaction = 0.044), RHR ≥ 80 beats per minute (bpm) group (<80 bpm: β = 0.072, 95%CI: 0.069–0.075; ≥80 bpm: β = 0.097, 95%CI: 0.092–0.102, P for interaction < 0.001) and enalapril-folic acid group (enalapril: β = 0.079, 95%CI: 0.075–0.082; β = 0.084, 95%CI, 0.080–0.088, P for interaction = 0.042). However, the effect of SBP on baPWV was consistent within MTHFR C677T and TC groups (all P for interaction > 0.05).

Figure 3.

Subgroup analyses of the effect of SBP on baPWV. Abbreviations: baPWV, brachial–ankle pulse wave velocity; SBP, systolic blood pressure; BMI, body mass index; MTHFR, methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase; FPG, fasting plasma glucose; TC, total cholesterol; Hcy, homocysteine; RHR, resting heart rate. *Adjusted for age, sex, center, MTHFR C677T polymorphisms, treatment group, antihypertensive treatment, BMI, smoking status, and alcohol consumption, RHR, TC, HDL-cholesterol, TG, FPG, creatinine, hcy, uric acid, if not be stratified.

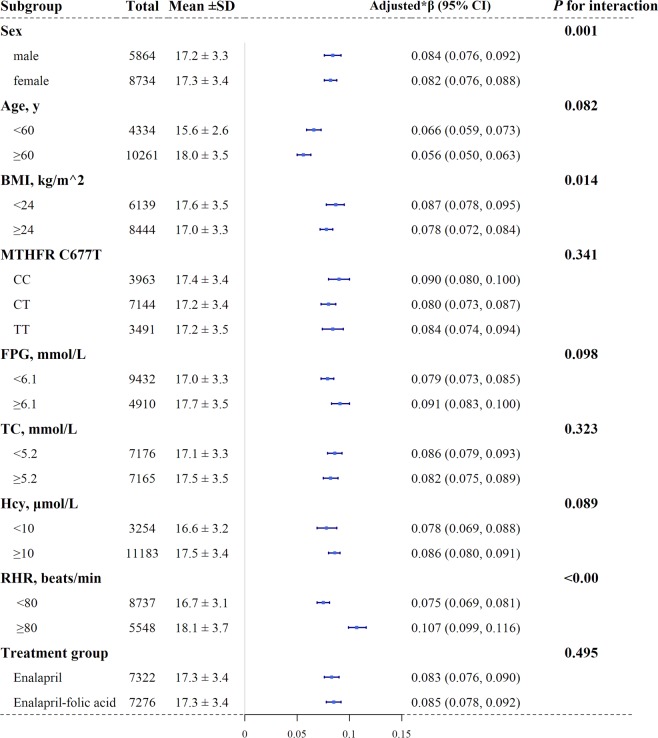

Figure 4 shows that DBP was positively associated with baPWV in each subgroup; thus this association was more significant in male patients than that in female patients and in the BMI < 24 kg/m2 group than that in the BMI ≥ 24 kg/m2 group and in RHR ≥ 80 bpm group (male: β = 0.084, 95%CI: 0.076–0.092; female: β = 0.082, 95%CI: 0.076–0.088, P for interaction = 0.001; BMI < 24 kg/m2: β = 0.087, 95%CI: 0.078–0.095; ≥24 kg/m2: β = 0.078, 95%CI: 0.072–0.084, P for interaction = 0.014; <80 bpm: β = 0.075, 95%CI: 0.069–0.081; ≥80 bpm: β = 0.107, 95%CI: 0.099–0.116, P for interaction < 0.001).

Figure 4.

Subgroup analyses of the effect of DBP on baPWV. Abbreviations: baPWV, brachial–ankle pulse wave velocity; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; BMI, body mass index; MTHFR, methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase; FPG, fasting plasma glucose; TC, total cholesterol; Hcy, homocysteine; RHR, resting heart rate. *Adjusted for age, sex, center, MTHFR C677T polymorphisms, treatment group, antihypertensive treatment, BMI, smoking status, and alcohol consumption, RHR, TC, HDL-cholesterol, TG, FPG, creatinine, hcy, uric acid, if not be stratified.

Supplementary Figure 1 shows the results of a subgroup analysis assessing the association of baPWV with PP. PP was also positively associated with baPWV in each subgroup. The stronger association between PP and baPWV were detected in high FPG (≥6.1 mmol/L) higher RHR (≥80 bpm) and enalapril-folic acid group (all P for interaction < 0.05). As with SBP, the positive association between MAP and baPWV was more stronger in males, age ≥60 years, BMI < 24 kg/m2, FPG ≥ 6.1 mmol/L, hcy ≥ 10 μmol/L and RHR ≥ 80 bpm groups compared with their corresponding groups (all P for interaction < 0.05) (Supplementary Fig. 2).

Discussion

In the present study, we found that SBP, DBP, PP and MAP levels were independently, significantly and positively associated with baPWV and elevated baPWV in treated hypertensive populations. The fully-adjusted smooth curve fitting showed a linear association between BP indices with baPWV. Moreover, uncontrolled SBP and DBP were significantly associated with higher baPWV. These findings suggest that baPWV might be a way to predict uncontrolled BP.

To our knowledge, few small sample population-based studies have addressed the relationship between BP indices and baPWV in treated hypertensive populations. Meili Zheng et al.20 used data from 3056 treated hypertensive subjects and found that baPWV appeared to be an independent determinant of individual response to anti-hypertensive treatment, most notably for SBP (with estimated coefficients of −9.01 for the top quartile, as compared to the bottom quartile). Protogerou Athanase et al.21 conducted a randomized, double-blind trial of 375 patients with hypertension and concluded that baseline PWV was a significant predictor of BP response to antihypertensive treatment, independent from age. Another study in patients with resistant hypertension indicated that a lower PWV reflected the predictors of higher BP reduction during spironolactone treatment22. Coutinho et al.23 noted that PWV was associated with longitudinal increases in SBP, MAP and PP but not DBP in a community-based cohort of hypertensive individuals. Consistent with previous studies, our study included a large sample and further showed that BP indices (SBP, DBP, MAP and PP) were independently and positively associated with baPWV and elevated baPWV in hypertensive populations. We also found the linear relationship between BP indices and baPWV using the smooth curve fitting. Moreover, uncontrolled SBP and DBP were significantly associated with higher baPWV. The study raises the possibility that baPWV may serve as a simple and noninvasive measurement to identify hypertensive adults whose BP was not being well controlled and a novel therapeutic target to further reduce CVD risk. Further research is needed to clarify the issue.

According to STROBE statement24, subgroup analysis can make better use of data to reveal underlying truths. Our findings showed that BP indices were positively assoiated with baPWV in subgroups and some fators modified the associations. The results suggested that males showed the stronger association between BP indices and baPWV. Some potential mechanisms including sex hormones could help explain the sex differences in this association. Male was a common risk factor for hypertension and arterial stiffness25,26. In aging males, hypogonadism is associated with increased arterial stiffening in central and peripheral vessels, while testosterone replacement reduces PWV27. In addition, we found that age could modify the associations of baPWV with SBP and MAP. Some researchers have confirmed that arterial stiffness and BP are increasing with the aging process28,29. Shouling Wu et al. also found that arterial stiffness mediated the positive association between aging and BP13. However, although our results showed that the association between DBP and baPWV was weaker in elderly, there was no statistical difference in the interaction test between different age groups. Perhaps because DBP decreased with increasing age, which was a major determinant of increasing baPWV30,31. Interestingly, we found that the effect of BP indices on baPWV was more significant in the low BMI group, suggesting a negative relationship between BMI and baPWV32,33. This finding might be due to the characteristics of our study participants: the majority of whom were farmers. We suspected that BMI in this population might reflect muscle mass and physical activity rather than adiposity. This finding was also in accordance with prior research34,35. Compared to the findings of previous studies25,32,36, we found, moreover, that higher RHR still had a higher association between baPWV and BP indices, suggesting RHR was the common risk factor for BP and baPWV. This phenomenon might be related to sympathetic nerve activity. Furthermore, previous research reported that FPG and hcy were independent risk factors for baPWV11,26, the present study investigated a large community-based sample from China and further confirmed that those with the higher FPG and hcy had a stronger association between baPWV and SBP and MAP.

Limitations and strengths

Several limitations of the study are worth mentioning. This study was cross-sectional and failed to establish a cause-and-effect relationship between BP indices and baPWV. Additionally, the study participants were from a Chinese, rural hypertensive population aged 45 to 75 years old; thus, the generalizability of the results to other populations remained to be verified. Despite these limitations, this study was one of the largest to assess the associations between BP indices and baPWV in hypertensive populations. Our study also reported the linearity between BP indices and baPWV using smooth curve fitting (penalized spline method).

Conclusions

In summary, our study showed that BP indices (including SBP, DBP, PP and MAP) were independently and positively associated with baPWV in treated hypertensive patients. Moreover, linearity between BP indices with baPWV was found. These findings suggest that baPWV might be a way to predict uncontrolled BP in treated hypertensive patients.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

We thank the investigators and participants of the China Stroke Primary Prevention Trial (CSPPT), the parent study, who made this report possible. Moreover, we gratefully thank Pro. Changzhong Chen and Dr. Xinglin Chen of the Department of Epidemiology and Biostatistics, X&Y solutions Inc. in Boston for their contribution to the statistical support. This work was supported by the National Key Research and Development Program [2016YFC0903101, 2016YFC0904900, 2016YFE0205400], the Projects of the National Natural Science Foundation of China [81473052 and 81402735]; the Science and Technology Planning Project of Guangzhou, China [201707020010]; and the Science, Technology and Innovation Committee of Shenzhen [KQCX20120816105958775, JSGG20160229173428526, JSGG20170412155639040, GJHS20170314114526143, KC2014JSCX0071A].

Author Contributions

Lihua Hu participated in literature search, study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, and wrote the manuscript. Yuanyuan Zhang, Xiao Huang, Yun Song, Ping Li, Huihui Bao, carried out the data collection and analysis, and provided the critical revision. Xianhui Qin, Binyan Wang, Yan Zhang, Genfu Tang, Jianping Li conceived of the study, and participated in its design and coordination. Yong Huo and Xiaoshu Cheng participated in study design and provided the critical revision. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Huihui Bao, Email: huihui_bao77@126.com.

Xiaoshu Cheng, Email: xiaoshumenfan126@163.com.

Supplementary information

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1038/s41598-019-44740-z.

References

- 1.Cavalcante JL, Lima JA, Redheuil A, Al-Mallah MH. Aortic stiffness: current understanding and future directions. J am coll cardiol. 2011;57:1511–22. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.12.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yamashina A, et al. Validity, reproducibility, and clinical significance of noninvasive brachial-ankle pulse wave velocity measurement. Hypertens Res. 2002;25:359–64. doi: 10.1291/hypres.25.359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vlachopoulos C, Aznaouridis K, Terentes-Printzios D, Ioakeimidis N, Stefanadis C. Prediction of cardiovascular events and all-cause mortality with brachial-ankle elasticity index: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Hypertension. 2012;60:556–62. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.112.194779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Najjar SS, et al. Pulse wave velocity is an independent predictor of the longitudinal increase in systolic blood pressure and of incident hypertension in the Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;51:1377–83. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.10.065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tomiyama H, Matsumoto C, Shiina K, Yamashina A. Brachial-Ankle PWV: Current Status and Future Directions as a Useful Marker in the Management of Cardiovascular Disease and/or Cardiovascular Risk Factors. J Atheroscler Thromb. 2016;23:128–46. doi: 10.5551/jat.32979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mancia G, et al. ESH/ESC guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension: the Task Force for the Management of Arterial Hypertension of the European Society of Hypertension (ESH) and of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) Eur Heart J. 2013;34:2159–219. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/eht151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kearney PM, et al. Global burden of hypertension: analysis of worldwide data. Lancet. 2005;365:217–23. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)70151-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lu J, et al. Prevalence, awareness, treatment, and control of hypertension in China: data from 1.7 million adults in a population-based screening study (China PEACE Million Persons Project) Lancet. 2017;390:2549–58. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)32478-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang Z, et al. Status of Hypertension in China: Results From the China Hypertension Survey, 2012–2015. Circulation. 2018;137:2344–56. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.117.032380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.O’Rourke MF, Nichols WW. Aortic diameter, aortic stiffness, and wave reflection increase with age and isolated systolic hypertension. Hypertension. 2005;45:652–8. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000153793.84859.b8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liu X, et al. The Independent and Joint Association of Blood Pressure, Serum Total Homocysteine, and Fasting Serum Glucose Levels With Brachial-Ankle Pulse Wave Velocity in Chinese Hypertensive Adults. Int Heart J. 2016;57:627–33. doi: 10.1536/ihj.16-082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Aatola H, et al. Influence of Child and Adult Elevated Blood Pressure on Adult Arterial Stiffness: The Cardiovascular Risk in Young Finns Study. Hypertension. 2017;70:531–6. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.117.09444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wu S, et al. Aging, Arterial Stiffness, and Blood Pressure Association in Chinese Adults. Hypertension. 2019;73:893–9. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.118.12396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Takase H, et al. Brachial-ankle pulse wave velocity predicts increase in blood pressure and onset of hypertension. Am J Hypertens. 2011;24:667–73. doi: 10.1038/ajh.2011.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McEniery CM, et al. An analysis of prospective risk factors for aortic stiffness in men: 20-year follow-up from the caerphilly prospective study. Hypertension. 2010;56:36–43. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.110.150896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kaess BM, et al. Aortic stiffness, blood pressure progression, and incident hypertension. Jama. 2012;308:875–81. doi: 10.1001/2012.jama.10503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Huo Y, et al. Efficacy of folic acid therapy in primary prevention of stroke among adults with hypertension in China: the CSPPT randomized clinical trial. Jama. 2015;313:1325–35. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.2274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chen SC, et al. Brachial-ankle pulse wave velocity and rate of renal function decline and mortality in chronic kidney disease. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2011;6:724–32. doi: 10.2215/CJN.07700910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ohkuma T, et al. Proposed Cutoff Value of Brachial-Ankle Pulse Wave Velocity for the Management of Hypertension. Circ j. 2017;81:1540–2. doi: 10.1253/circj.CJ-17-0636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zheng M, et al. A prospective study on pulse wave velocity (PWV) and response to anti-hypertensive treatments: PWV determines BP control. Int J Cardiol. 2015;178:226–31. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2014.10.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Protogerou A, Blacher J, Stergiou GS, Achimastos A, Safar ME. Blood Pressure Response Under Chronic Antihypertensive Drug Therapy. J am coll cardiol. 2009;53:445–51. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.09.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.de Souza F, Muxfeldt E, Fiszman R, Salles G. Efficacy of spironolactone therapy in patients with true resistant hypertension. Hypertension. 2010;5:147–52. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.109.140988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Coutinho T, Bailey KR, Turner ST, Kullo IJ. Arterial stiffness is associated with increase in blood pressure over time in treated hypertensives. J Am Soc Hypertens. 2014;8:414–21. doi: 10.1016/j.jash.2014.03.330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vandenbroucke JP, et al. Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE): explanation and elaboration. Plos Med. 2007;4:e297. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0040297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hu L, et al. Prevalence and Risk Factors of Prehypertension and Hypertension in Southern China. Plos One. 2017;12:e170238. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0170238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Qian G, et al. Associations between plasma total homocysteine, blood pressure stages and pulse wave velocity in Chinese rural community population. Blood Press. 2015;24:340–6. doi: 10.3109/08037051.2014.997089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yaron M, et al. Effect of testosterone replacement Therapy On Arterial Stiffness In Older Hypogonadal Men. Eur J Endocrinol. 2009;160:839–46. doi: 10.1530/EJE-09-0052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McEniery CM, et al. The impact of cardiovascular risk factors on aortic stiffness and wave reflections depends on age: the Anglo-Cardiff Collaborative Trial (ACCT III) Hypertension. 2010;56:591–7. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.110.156950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Levine DA, et al. Geographic and demographic variability in 20-year hypertension incidence: the CARDIA study. Hypertension. 2011;57:39–47. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.110.160341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Takahashi R, et al. Very small low-density lipoprotein cholesterol level is a determinant of arterial stiffness in men with impaired glucose metabolism. J Atheroscler Thromb. 2010;17:1282–9. doi: 10.5551/jat.5272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Miyai N, et al. Age-specific nomogram of brachial-ankle pulse wave velocity in Japanese adolescents. Clin Exp Hypertens. 2013;35:95–101. doi: 10.3109/10641963.2012.690473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ato D, Sawayama T. Factors associated with high brachial-ankle pulse wave velocity in non-hypertensive and appropriately treated hypertensive patients with atherosclerotic risk factors. Vasc Health Risk Manag. 2017;13:383–92. doi: 10.2147/VHRM.S144923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Song Y, et al. Independent and Joint Effect of Brachial-Ankle Pulse Wave Velocity and Blood Pressure Control on Incident Stroke in Hypertensive Adults. Hypertension. 2016;68:46–53. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.115.07023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Momin M, et al. Body mass index is inversely associated with arterial stiffness in Chinese adults with primary hypertension: results from the China Stroke Primary Prevention Trial (CSPPT) Clin Exp Hypertens. 2017;39:394–401. doi: 10.1080/10641963.2016.1254226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ochi M, et al. Arterial stiffness is associated with low thigh muscle mass in middle-aged to elderly men. Atherosclerosis. 2010;212:327–32. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2010.05.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sonoda H, Takase H, Dohi Y, Kimura G. Factors associated with brachial-ankle pulse wave velocity in the general population. J Hum Hypertens. 2012;26:701–5. doi: 10.1038/jhh.2011.100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.