Abstract

Background:

Gastric cancer (GC) is the first and the third prevalent cancer among males and females in Iran, respectively. The aim of this study was mainly to identify high-risk areas of GC by assessing the spatial and temporal pattern of incidence, and second, to explore some risk factors of GC in ecological setting.

Methods:

In this cross-sectional ecological study we used Bayesian hierarchical space-time model to measure the relative risk and temporal trends of GC in Iran from 2005 to 2010 based on available data. Data analysis was done by the use of integrated nested Laplace approximation Bayesian approach in R software.

Results:

Overall trend of GC was significantly decreasing during the study period. Ardabil, Khorasan Razavi, West Azarbaijan, Zanjan, and Mazandaran provinces had the highest risk of incidence. Overweight and smoking were directly and significantly associated with GC risk.

Conclusions:

During the study period, GC has decreased in Iran. Nevertheless, GC risk was generally high in Northern and Northwestern provinces of Iran. Different health policies according to GC risk and trend are required for each province. Improvements in screening and education programs and conducting further epidemiological studies could help to reduce the incidence of GC in high risk provinces.

Keywords: Bayesian, disease mapping, gastric cancer, hierarchical space-time

Introduction

Cancer is one of major public health issues leading to almost 7.6 million deaths worldwide 70% of which happen in low- and middle-income countries.[1] According to the report of the International Agency for Research on Cancer, GC was the fifth most common cancer and the third leading cause of cancer death in the world in 2012. In 2015, the estimated incident cases and death from stomach cancer was 1.3 million (95% confidence interval [CI] = 1.2–1.4 million) and 819,000 (95% CI = 795,000–844,000) worldwide.[1,2]

Despite declining prevalence in most of the developed countries in the past 5 decades, GC incidence is still high. The incidence and mortality rates of stomach cancer have been reported to be highest in East Asia where it accounts for 15% of annual cancer-related deaths in Japan over the past four decades.[3] These rate are also high in Central and South America, Eastern Europe, and parts of Middle East.[2] The rate and trend of GC incidence is stable with minor decreasing pattern in most of Western Asia countries.[3] In the Middle East, the home of three main ethnicities: Semitic (Arabs and Jews), Indo-European (Persians and Kurdish), and Turkic (Turkish and Turkmens), the incidence differs from very high in Iran, with age-standardized incidence rate (ASR) of 26.1, to very low in Egypt, with ASR of 3.4/100000 population.[3] GC is the most common malignant disease in Iran and Oman, and it occurs nearly 7 times more frequently in Iran than in Iraq.[3] In 2012, GC accounted for 11.4% of all cancer cases in Iran and is considered as the second most prevalent cancer, and the first and the third kind of cancer among males and females, respectively, comprising 15.5% of all cancer deaths. The incidence in males is 2.2 times that in females.[4] According to previous regional studies, Southern provinces in Iran have low incidence, whereas the incidence is intermediate and high for Central and Northern provinces, respectively.[5]

A number of studies have been conducted on cancer mapping in Iran.[6,7,8,9,10,11] However, studies about mapping of GC are not frequent. Furthermore, there is no comprehensive study to assess trends of incidence in all provinces of Iran. The main aim of the current study was to evaluate the geographical distribution and temporal pattern of GC in Iran. As a second target, we used available information on some risk factors to assess their plausible contribution to GC. This was conducted through Bayesian disease mapping methods, a more logical way of analysis of aggregate data in ecological setting, that help to produce atlases, show spatial variation, formulate and validate ecological hypotheses, assess health inequalities and adopt better health policies.[12] Spatiotemporal models account for correlated and uncorrelated heterogeneity, and hence, could help to assess interactions between time and area without problems inherent in commonly used risk indicator of standardized mortality or incidence rates.[13]

Previous studies on GC in Iran have mainly used traditional methods for analysis that have shortcomings. In this study, we aimed to assess GC incidence with modern methods of disease mapping that circumvent previous shortcomings and provide more accurate geographical distribution and incidence of the disease. It also identifies provinces with high and low risk of GC.

Materials and Methods

Study design and data sources

The data on new gastric cancer (GC) cases (ICD10 code C16) were obtained from Iran Cancer Registry Reports by Cancer Office at the Noncommunicable Diseases Center, Iran Ministry of Health and Medical Education in 30 provinces from 2005 to 2010. In Iran, cancer incidence is estimated based on pathology-based cancer registry, in which all pathology centers report all cancer cases. This registry does not cover other sources of population-based cancer registry, including death records, hospital records, and clinical data. Evaluation of the results of the national pathology-based cancer registry showed that this registry was approximately similar in the provinces, but it underestimated the cancer incidence due to covering only 60%–70% of the cancer cases.[14]

Due to the retrospective nature of the study and the use of aggregated data, informed consent and ethics approval were not required.

The results were adjusted for physical activity, smoking, fruit and vegetable consumption, and percent of overweight and obese people in each province. All these factors were calculated in an ecological setting. Smoking in each province was the multiplication of the proportion of smokers by the mean number of daily smoked cigarettes. Overweight and obesity was the percentage of the population with body mass index of >25 in each province. Fruit and vegetable consumption was measured as the mean fruit and vegetable units used daily in each province. Physical activity was measured by combined index of metabolic equivalent.

Statistical analysis

We used space–time models to explore trends of GC incidence and evaluate the association of risk factors on GC incidence.[9,15,16] The crude incidence is estimated by dividing total gastrointestinal (GI) cancer cases in the province to total population of each province scaled per 100,000 population in years 2005–2010. The standardized incidence is derived from the division of the incidence to its predicted value per 100,000 population. Relative risk is also estimated by using statistical methods and compares the incidence in each province against all country.

The following is a summary of the model proposed by Bernardinelli et al. with extra terms for time. If i donate the area or province, and k as the time indicator, by assuming a Poisson distribution for observed number of events, RR can be incorporated into the rate of incidence as follows.

Oit ~ Poisson (Eit RRit)

log(RRit) = α + ui + vi +  βj+xijt+ β × t + δi × t

βj+xijt+ β × t + δi × t

As Oit and Eit are the observed and the expected number of cases for province i = 1,…, 30 in year t = 1,…, 6; is the overall RR, and and are the correlated and uncorrelated heterogeneity, respectively.represents risk factor j = 1,…, J for province i in year t. Temporal trends (TT) reflect mean trends in the whole country, whereas differential trends show the local trends compared to the mean trend. Furthermore, GC relative risk without adjusting for risk factors was studied in age and sex groups.

All analyses were performed in Bayesian setting using R package integrated nested Laplace approximation (http://www.r-inla.org).[17] The Bayesian approach has been used due to the intrinsic property of ecological studies, that is, one observation per study unit for estimating model parameters.

Results

There were 10756 female and 26041 male GC cases in Iran during 2005–2010. The incidence in males was 2.44 times in females in this episode of time. The most number of observed GC cases was in Tehran with 6397 cases [Table 1].

Table 1.

Relative risk of gastric cancer in Iran 2005-2010

| Province | Year | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | |

| Ardebil | 2.716 | 2.671 | 2.627 | 2.540 | 2.497 | 2.455 |

| Kurdistan | 2.528 | 2.486 | 2.445 | 2.364 | 2.324 | 2.285 |

| Khorasan Razavi | 2.310 | 2.271 | 2.234 | 2.160 | 2.123 | 2.088 |

| Zanjan | 2.092 | 2.057 | 2.023 | 1.956 | 1.923 | 1.891 |

| West Azerbaijan | 2.085 | 2.050 | 2.016 | 1.949 | 1.917 | 1.885 |

| Mazandaran | 1.801 | 1.771 | 1.742 | 1.684 | 1.656 | 1.628 |

| Chaharmahal-Bakhtiari | 1.561 | 1.535 | 1.510 | 1.460 | 1.435 | 1.411 |

| Golestan | 1.534 | 1.508 | 1.483 | 1.434 | 1.410 | 1.386 |

| Guilan | 1.526 | 1.501 | 1.476 | 1.427 | 1.403 | 1.380 |

| Lorestan | 1.466 | 1.441 | 1.418 | 1.371 | 1.348 | 1.325 |

| Qom | 1.409 | 1.385 | 1.362 | 1.317 | 1.295 | 1.273 |

| Kermanshah | 1.331 | 1.309 | 1.287 | 1.244 | 1.223 | 1.203 |

| Hamadan | 1.297 | 1.276 | 1.255 | 1.213 | 1.193 | 1.173 |

| Semnan | 1.287 | 1.266 | 1.244 | 1.203 | 1.183 | 1.163 |

| Ilam | 1.156 | 1.137 | 1.118 | 1.081 | 1.063 | 1.045 |

| Kohgiluyeh-Boyer-Ahmad | 1.124 | 1.106 | 1.088 | 1.051 | 1.034 | 1.017 |

| Ghazvin | 1.088 | 1.071 | 1.053 | 1.018 | 1.001 | 0.984 |

| South Khorasan | 1.020 | 1.003 | 0.987 | 0.954 | 0.938 | 0.922 |

| North Khorasan | 0.943 | 0.928 | 0.912 | 0.882 | 0.867 | 0.853 |

| Markazi | 0.915 | 0.901 | 0.885 | 0.856 | 0.842 | 0.828 |

| Fars | 0.838 | 0.825 | 0.811 | 0.784 | 0.771 | 0.758 |

| Isfahan | 0.798 | 0.785 | 0.772 | 0.747 | 0.734 | 0.722 |

| East Azerbaijan | 0.732 | 0.720 | 0.708 | 0.685 | 0.673 | 0.662 |

| Kerman | 0.712 | 0.701 | 0.689 | 0.666 | 0.655 | 0.644 |

| Tehran | 0.642 | 0.632 | 0.622 | 0.601 | 0.591 | 0.581 |

| Yazd | 0.551 | 0.542 | 0.533 | 0.515 | 0.507 | 0.498 |

| Khuzestan | 0.475 | 0.467 | 0.460 | 0.444 | 0.437 | 0.430 |

| Hormozgan | 0.371 | 0.366 | 0.359 | 0.348 | 0.342 | 0.336 |

| Bushehr | 0.347 | 0.341 | 0.336 | 0.325 | 0.319 | 0.314 |

| Sistan-Baluchestan | 0.229 | 0.225 | 0.222 | 0.214 | 0.211 | 0.207 |

Due to data availability, we considered cancer data from 2003 to 2007 for risk evaluation. We considered a lag of 2 years for cancer incidence and diagnosis, that is, the cancer data from 2005 to 2009.

The results of adjusted model are shown in Table 2. In this model, time effect was decreasing and statistically significant. Furthermore, smoking and being overweight had direct correlation with GC.

Table 2.

Estimated coefficients of risk factors from model adjusting for all studied risk factor

| Parameter estimation | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|

| Intercept | −1.087 | −1.3424-−0.08328 |

| Smoking | 0.002 | 0.0015-0.0024 |

| Weight | 0.0178 | 0.0128-0.0229 |

| Physical activity | 0.00005 | −0.0037-0.0038 |

| Fruit and vegetable | 0.0141 | −0.0282-0.0561 |

| Year | −0.0191 | −0.0342-−0.0041 |

CI=Confidence interval

According to this table, risk of GC has decreased by 2% in each year. Furthermore, relative risk of developing GC is 1.002 per each extra cigarette per day and every 5 kg increase in weight is associated with almost 10% increase in GC risk.

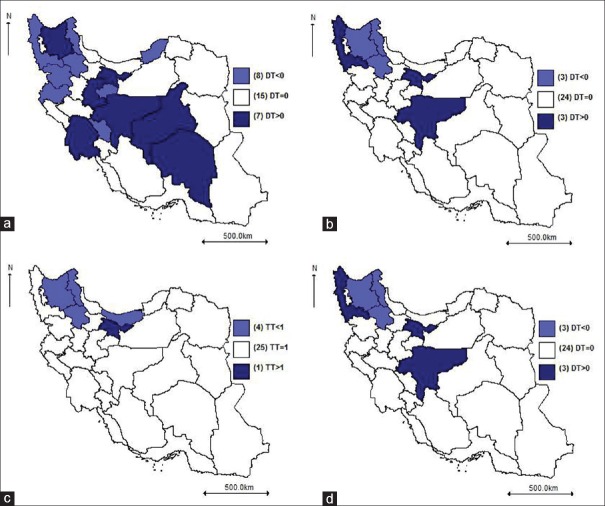

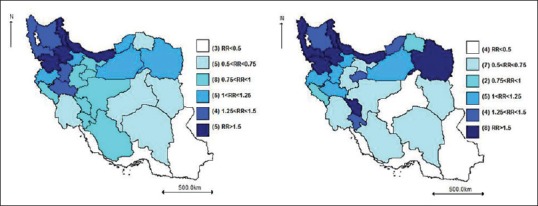

Figure 1a shows relative risk of GC in provinces after adjusting for all risk factors in 2010. According to this map, Ardabil, Khorasan Razavi, West Azarbaijan, Zanjan, and Mazandaran provinces have the highest risk (RR >1.6) and Sistan-Baluchestan, Bushehr, Hormozgan, and Khuzestan provinces have the least risk (RR <0.5) of GC.

Figure 1.

Relative risk of gastric cancer in 2010: (a) adjusted for risk factors in 2010; (b) unadjusted

Figure 1b shows crude risk in 2010 where Ardabil, Kurdistan, West Azarbaijan, Mazandaran, Zanjan, and Gilan had the highest crude risk (RR >1.6) and Sistan-Baluchestan, Bushehr, Hormozgan, and Khuzestan had the least risk (RR <0.5) of GC.

The map of unadjusted relative risk within 6 years is shown in Figure 2. As indicated by this map, Ardebil, Kurdistan, West Azerbaijan, Mazandaran, Gilan, and Khorasan Razavi provinces had the most risk of incidence and Sistan-Baluchestan, Bushehr, and Hormozgan provinces had the least risk of cumulative incidence during 6 years of the study.

Figure 2.

The unadjusted gastric cancer relative risk estimated by the Besag, York, and Mollie model

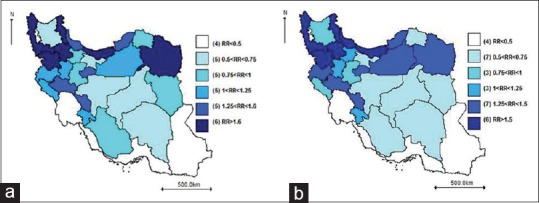

Unadjusted risk for males and females

The maps of GC relative risk without adjusting for risk factors in males and females are shown in Figure 3. Ardabil, Mazandaran, Kurdistan, Gilan, and Zanjan provinces have the most risk (RR >1.5) in both sexes and Sistan-Baluchestan, Bushehr, and Hormozgan provinces have the least risk (RR <0.5) of GC. In contrast, West Azerbaijan, Chaharmahal Bakhtiari and Khorasan Razavi had higher risk among males. Time effect was significant and decreasing in males only.

Figure 3.

Unadjusted relative risk of gastric cancer in Iran for males and females in 2010

Unadjusted risk for age groups

GC cases were divided into 6 age groups of <25, 25–34, 35–44, 45–54, 55–64, and >64 years. Only in the first and the fourth age group, time effect was significantly decreasing. The risk of GC was the lowest (RR <1.5) in age group 1, 2, and 3 (<44-year-old). Khorasan Razavi, Ardabil, Kurdistan, and West Azerbaijan provinces and South Khorasan province had the highest and the least risk of GC in the country in the age group 4 (45–54 years), respectively.

In age group 5 (55–64 years), Kurdistan, Ardabil, West Azarbaijan, Khorasan Razavi, Kermanshah provinces and Bushehr, South Khorasan, and Sistan-Baluchestan provinces have the most and least risk of GC in the country, respectively.

In the age group 6 (>64 years), Ardabil, Khorasan Razavi, Kurdistan, West Azarbaijan, Zanjan, Chaharmahal Bakhtiari, Golestan, Mazandaran and Kermanshah provinces, and South Khorasan, Sistan-Baluchestan, Hormozgan, Northern Khorasan, and Yazd provinces have the most and least risk of GC in the country, respectively.

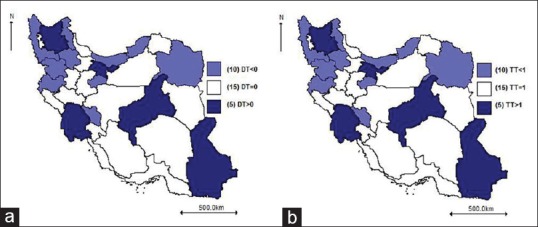

Adjusted temporal trends of gastric cancer

DT is shown in Figure 4. The trend for Eastern Azerbaijan, Khuzestan, Sistan-Baluchestan, Tehran, and Yazd Provinces are considerably steeper than other parts of the country. For making the results clearer, temporal trend was calculated in Figure 4b TT significantly decreasing in Ardabil, West Azarbaijan, Chaharmahal Bakhtiari, Golestan, Kermanshah, Khorasan Razavi, Kurdistan, Mazandaran, Qom, and Zanjan), Eastern Azerbaijan, Khuzestan, Sistan-Baluchestan, Tehran, and Yazd had increasing trend.

Figure 4.

Trends of gastric cancer in Iran during 2005–2010 after adjusting for studied risk factors. (a) temporal trends; (b) differential trends

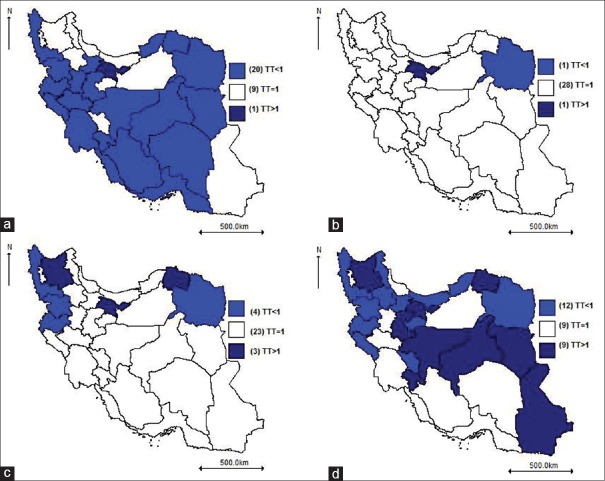

Unadjusted temporal trend maps of gastric cancer in males and females

Figure 5a shows DT among males. The trends for East Azarbaijan, Isfahan, Kerman, Khuzestan, Markazi, Tehran, and Yazd were remarkably steeper than other parts of the country. Figure 5b indicates a decreasing trend in 9 provinces, whereas increasing trend was found in four provinces (East Azarbaijan, Markazi, Tehran and Yazd). Figure 5c represents DT among females. The trend in West Azarbaijan, Isfahan and Tehran was considerably steeper than other parts of the country. Figure 5d indicates decreasing trend in four provinces, whereas increasing trend was seen in Tehran.

Figure 5.

Gastric cancer trends in Iran 2005–2010 without adjusting for risk factors in males and females. (a) temporal trends in males; (b) differential trends in males; (c) differential trends in females; (d) temporal trend in females

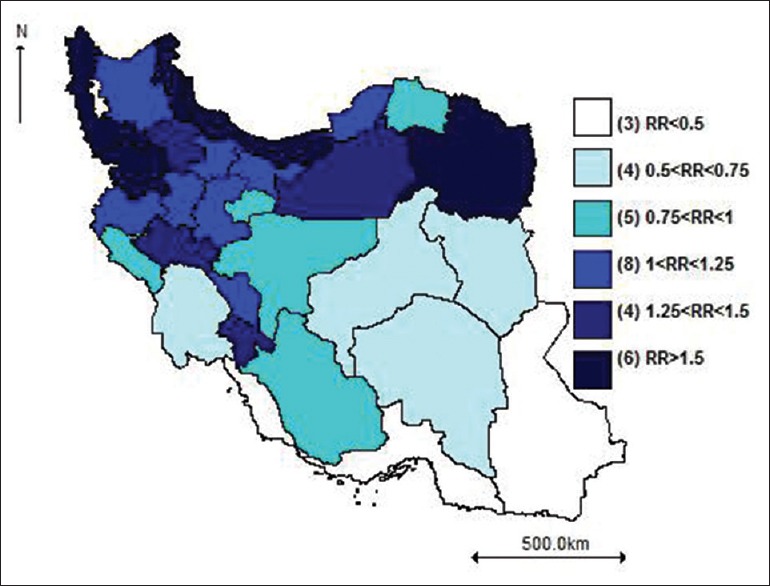

Unadjusted temporal trend map of gastric cancer in age groups

Figure 6 indicates province-specific temporal trend in age groups. In the age groups 1 and 4, Tehran had an increasing trend of GC. In Group 5, East Azarbaijan, Khorasan, and Tehran and in the age group 6, East Azarbaijan, Isfahan, South Khorasan, North Khorasan, Kohgiluyeh and Boyer-Ahmad, Markazi, Sistan-Baluchestan, Tehran, and Yazd have an increasing trend of GC as well. In age groups 2 and 3, no trend was seen.

Figure 6.

Gastric cancer trends for age groups in Iran without adjusting for risk factors during 2005–2010, without adjusting for risk factors (a) Group 1= less than 25-year-old; (b) Group 4= 45–54-year-old; (c) Group 5= 55–64-year-old; (d) Group 6= older than 64-year-old; temporal trends = temporal trend; <1= decreasing trend, 1= fixed trend, >1= increasing trend

Discussion

The findings suggest that people living in North and Northwest of Iran had higher risk of GC than the people living in other areas. There was also a significant decreasing overall trend during 2005–2010. Lack of access to information on risk factors such as consumption of red meat, alcohol, and tobacco consumption at the provincial level for age and gender subgroups as well as the unavailability of data beyond 2010 are the main constraints of this study.

Some previous studies have indicated increasing trend of GC in Iran in an overlapping period.[18,19,20] It should be noted that these studies use classic methods of analysis such as Poisson assumption and joinpoint analysis, that are challenging and could not cover all aspects of the disease distribution, including correlated and uncorrelated heterogeneity between provinces. Inclusion of such considerations in the analysis could improve the fit of data and give more accurate estimates on trends of the GC.[9]

The trends of incidence and mortality rate of GC have steadily declined in the past five decades worldwide.[5] The pattern is common for most countries regardless of the background risk of GC. Even in areas with historically high GC rates, similar decreasing trends were present in recent years.[5] This remarkable decline in the incidence is thought to be, at least partly, due to improvements in food preservation and storage techniques (keeping foods in refrigerator instead of making smoked and smoked salt foods) that have allowed greater intake of fresh fruits and vegetables with higher levels of antioxidants; a general improvement in lifestyle, nutritional status and the quality of drinking-water; improvements in socioeconomic status and having less people residing in the rural areas, as farmers and ranchers, illiterates and all in all, deprived people; use of antibiotics, behavioral patterns, and exposures to pesticides and other related environmental factors.[21,22,23]

A number of studies have been conducted about mapping of GC in Iran, but none of them have focused on the cancer trend and risk factors, sex, and age.[24,25] The cancer control process may remarkably depend on sex and the incidence of this disease significantly. In the present study, the distribution of high-risk zones of GC incidence has similar patterns among males in almost all parts of the country. However, the pattern is a little different among females. In 30 provinces of the country, 8 and 4 provinces have the highest levels of incidence. Time trends are significantly decreasing and increasing in males and females, respectively. GC trend was increasing within females in East Azarbaijan, Markazi, Tehran, and Yazd and within males in Tehran.

GC is more prevalent in the ages over 50.[26] The most frequent cases are seen in 70–80 years of age. GC is rare in the ages below 20 and after age of 40, the incidence increased constantly.[27] The relative frequency of GC was higher in the age group >70, so the incidence is elevated by age. The most common age of GC prevalence is in ages of 61–80. GC incidence is higher in the fifth and the eighth decades of life and the risk is decreased in the ages under 44.

Smoking is an independent risk factor for different types of GI tract cancers. Similar to results from the previous studies, direct link between smoking and GC was found in the current ecological study.[28]

Obesity and its related disorders are claimed to be associated with the increased risk of different cancers of GI tract, especially esophageal and GCs. Epidemiological and experimental evidence suggests that obesity has high impact on cancers.[29] Here, we observed the significant relationship between being overweight and GC.

More research is needed to find other important risk factors of GI tract cancers and the pattern of their distribution in Iran. From this viewpoint, various risk factors may be addressed. Regional case–control and cohort studies have suggested Helicobacter pylori infection, tobacco and opium use, and diets with high levels of salt intake and insufficient levels of antioxidants could contribute to pathogenesis of GC.[5]

Among the possible risk factors of GC, H. pylori infection is claimed to be a main risk factor, especially for noncardia GC. The H. pylori infection rate was found to be very high in different parts of Iran, with a prevalence rate ranging from 69% to 89% and increasing with age. Furthermore, the age at acquisition of H. pylori infection is very low.[3,5] Population-based studies found that >80% of adults aged ≥40 years were infected.[30] However, contribution of the high prevalence of H. pylori infection in Iran to an excess GC risk is not clear. H. pylori in Iran is mostly of cagA-positive type, where its relation to GC is not, at least in the Iranian population, clear.[5,22]

The results of previous studies in the Middle East countries show that the prevalence of H. pylori infection in Iraq, Iran, Turkey, Libya, Egypt, Bahrain, Oman, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates are relatively high and almost similar.[3,5] Despite high H. pylori infection rate in Middle East countries, it is not reflected in GC rates that vary from very high in Iran to intermediate in Turkey to very low in Iraq and Egypt.[3] Studies from Iran, Iraq, Kuwait, and Jordan did not show any association between vacA s and m genotypes and gastroduodenal diseases.[31,32,33] Other antigenic determinants of H. pylori, such as dupA, have not shown any clear links with GC risk in Iran.[34] The inclusion of H. pylori prevalence and pattern could provide useful information on the association. Unfortunately, related data were not available for all provinces and furthermore, the reported information was sporadic and at different times.

Several Iranian studies have shown that environmental risk factors including tobacco use, opium use, high salt intake, and insufficient level of antioxidants are involved in the incidence of GC.[34,35,36] Other factors including male gender and several genetic backgrounds are among the less effective risk factors known to date for the disease.[5] In addition to the well-established risk factors for noncardia GC, gastroesophageal reflux disease, and obesity have been found to be two main risk factors for cardia cancer.[5]

Using fresh fruits, vegetables, and antioxidants are protective against GC. Despite the use of fresh fruits and vegetables is high in some areas with high prevalence of GC, the people in these regions use high amounts of red meat which is considered as risk factors for GC.[22,37] The relationship between risk of GC and frequent consumption of red meat has been reported by several studies.[37] In previous regional studies, such as in Ardabil, the frequent consumption of red meat has been found to be associated with a higher rate of intestinal metaplasia of gastric mucosa. The causal association between red meat and GC could be through potential effects of high levels of fat, protein, nitrite and nitrosamines, salt, heterocyclic amines, and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons.[36] However, full data from all provinces in all years under the study were not available to be included in our analysis.

In general, irrespective of sex and age, GC incidence trend was significantly decreasing. Ten provinces showed decreasing trend and five provinces had increasing trends. These results could be justified by considering factors in these regions. Health science specialists believe that the causes of GI cancer incidence include consuming spicy food, conserved dishes, vinegar and pickles, prolonged use of salted, smoked, and dried foods. They all have huge amounts of nitrate and hurt GI tract. These foods are used more in northern parts of Iran rather than other regions. In Southern regions, people consume date which is full of antioxidants and can be effective in preventing from GI tract cancers. Hence, they suffer less from GC. The way people preserve the food may also be an explanation, at least in part, to the decreasing trend of GC. Although traditional ways of preservation in some areas, the use of refrigerator has been definitely increased during the past decades as a consequence of improvements in overall welfare and economic conditions of Iranian families.[21] Using smoked fish has been considered as major risk factors for provinces in coastal areas of Caspian Sea, especially in its Western side.

We suggest using complete data, if available, for assessing long-term trends of GC in Iran. It is also imperative to conduct focused investigations in the regions with high GC prevalence to find related risk factors. Inclusion of factors such as tobacco and alcohol use, socioeconomic condition, unhealthy nutrition, viral, and genetic agents could be of interest in the future works.

Financial support and sponsorship

This work was financially supported by Isfahan University of Medical Sciences.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to the Noncommunicable Disease Department of Iran Ministry of Health and Medical Education. This paper is extracted from MSc. thesis (number 393556) at Isfahan University of Medical Sciences.

References

- 1.Fateh M, Emamian MH. Cancer incidence and trend analysis in Shahroud, Iran, 2000-2010. Iran J Cancer Prev. 2013;6:85–94. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hussein NR. Helicobacter pylori and gastric cancer in the Middle East: A new enigma.? World J Gastroenterology: WJG. 2010;16:3226–34. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v16.i26.3226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rahman R, Asombang AW, Ibdah AJ. Characteristics of gastric cancer in Asia. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:4483–90. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i16.4483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.GLOBOCAN 2012: Estimated Cancer Incidence, Mortality and Prevalence Worldwide in 2012. [Last accessed on 2017 Jan]. Available from: http://www.globocaniarcfr/Pages/fact_sheets_canceraspx .

- 5.Malekzadeh R. Effect of Helicobacter pylori Eradication on Different Subtypes of Gastric Cancer: Perspective from a Middle Eastern Country. Helicobacter pylori Eradication as Strategy for Preventing Gastric Cancer. 2014;8:55–60. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rastaghi S, Jafari-Koshki T, Mahaki B. Application of bayesian multilevel space-time models to study relative risk of esophageal cancer in Iran 2005-2007 at a county level. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2015;16:5787–92. doi: 10.7314/apjcp.2015.16.14.5787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Khoshkar AH, Koshki TJ, Mahaki B. Comparison of bayesian spatial ecological regression models for investigating the incidence of breast cancer in Iran, 2005- 2008. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2015;16:5669–73. doi: 10.7314/apjcp.2015.16.14.5669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Haddad-Khoshkar A, Jafari-Koshki T, Mahaki B. Investigating the incidence of prostate cancer in Iran 2005 -2008 using bayesian spatial ecological regression models. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2015;16:5917–21. doi: 10.7314/apjcp.2015.16.14.5917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jafari-Koshki T, Arsang-Jang S, Mahaki B. Bladder Cancer in Iran: Geographical Distribution and Risk Factors, Int J Cancer Manag. 2017;10:e5610. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mahaki B, Mehrabi Y, Kavousi A, Schmid VJ. Joint Spatio-Temporal Shared Component Model with an Application in Iran Cancer Data. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2018;19:1553–60. doi: 10.22034/APJCP.2018.19.6.1553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Raei M, Schmid VJ, Mahaki B. Bivariate spatiotemporal disease mapping of cancer of the breast and cervix uteri among Iranian women. Geospatial Health. 2018;13:164–171. doi: 10.4081/gh.2018.645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ahmadipanahmehrabadi V, Hassanzadeh A, Mahaki B. Bivariate spatiotemporal shared component modeling: Mapping of relative death risk due to colorectal and stomach cancers in Iran provinces. Int J Prev Med. 2018;9 doi: 10.4103/ijpvm.IJPVM_31_17. In Press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jafari-Koshki T, Arsang-Jang S, Raei M. Applying spatiotemporal models to study risk of smear-positive tuberculosis in Iran, 2001-2012. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2015;19:469–74. doi: 10.5588/ijtld.14.0459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zendehdel K, Sedighi Z, Hassanloo J, Nahvijou A. Audit of a nationwide pathology-based cancer registry in Iran. Basic Clin Cancer Res. 2011;3:7–13. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jafari-Koshki T, Arsang-Jang S, Raei M. Applying spatiotemporal models to study risk of smear-positive tuberculosis in Iran, 2001-2012. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2015;19:469–74. doi: 10.5588/ijtld.14.0459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mahaki B, Mehrabi Y, Kavousi A, Schmid VJ. Joint spatio-temporal shared component model with an application in Iran Cancer Data. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2018;19:1553–60. doi: 10.22034/APJCP.2018.19.6.1553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Blangiardo M, Cameletti M, Baio G, Rue H. Spatial and spatio-temporal models with R-INLA. Spat Spatiotemporal Epidemiol. 2013;7:39–55. doi: 10.1016/j.sste.2013.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Enayatrad M, Salehiniya H. Trends in gastric cancer incidence in Iran. J Mazandaran Univ Med Sci. 2014;24:8–16. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Almasi Z, Rafiemanesh H, Salehiniya H. Epidemiology characteristics and trends of incidence and morphology of stomach cancer in Iran. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2015;16:2757–61. doi: 10.7314/apjcp.2015.16.7.2757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Darabi M, Asadi Lari M, Motevalian SA, Motlagh A, Arsang-Jang S, Karimi Jaberi M, et al. Trends in gastrointestinal cancer incidence in Iran, 2001-2010: A joinpoint analysis. Epidemiol Health. 2016;38:e2016056. doi: 10.4178/epih.e2016056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Haidari M, Nikbakht MR, Pasdar Y, Najaf F. Trend analysis of gastric cancer incidence in Iran and its six geographical areas during 2000-2005. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2012;13:3335–41. doi: 10.7314/apjcp.2012.13.7.3335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Malekzadeh R, Derakhshan MH, Malekzadeh Z. Gastric cancer in Iran: Epidemiology and risk factors. Arch Iran Med. 2009;12:576–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Goh KL. Changing trends in gastrointestinal disease in the Asia-Pacific region. J Dig Dis. 2007;8:179–85. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-2980.2007.00304.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Asmarian N, Jafari-Koshki T, Soleimani A, Taghi Ayatollahi SM. Area-to-area poisson kriging and spatial bayesian analysis in mapping of gastric cancer incidence in Iran. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2016;17:4587–90. doi: 10.22034/APJCP.2016.17.10.4587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nasrazadani M, Maracy M, Mahaki B. Mapping of stomach, colorectal and bladder cancers in Iran, 2004-2009: Applying bayesian polytomous logit model. Int J Prev Med. 2018;9 doi: 10.4103/ijpvm.IJPVM_30_17. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kavousi A, Bashiri Y, Mehrabi Y, Etemad K. Modeling high-risk areas for gastric cancer in men and women, 2005-2009. J Isfahan Med Sch. 2015;33:82–92. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Moghimi-Dehkordi B, Safaee A, Fatemi R, Ghiasi S, Zali MR. Impact of age on prognosis in Iranian patients with gastric carcinoma: Review of 742 cases. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2010;11:335–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Song Q, Zhang Z, Liu Y, Han S, Zhang X. The tag SNP rs10746463 in decay-accelerating factor is associated with the susceptibility to gastric cancer. Mol Immunol. 2015;63:473–8. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2014.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tilg H, Moschen AR. Mechanisms behind the link between obesity and gastrointestinal cancers. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2014;28:599–610. doi: 10.1016/j.bpg.2014.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sotoudeh M, Derakhshan MH, Abedi-Ardakani B, Nouraie M, Yazdanbod A, Tavangar SM, et al. Critical role of Helicobacter pylori in the pattern of gastritis and carditis in residents of an area with high prevalence of gastric cardia cancer. Dig Dis Sci. 2008;53:27–33. doi: 10.1007/s10620-007-9817-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hussein NR, Mohammadi M, Talebkhan Y, Doraghi M, Letley DP, Muhammad MK, et al. Differences in virulence markers between Helicobacter pylori strains from Iraq and those from Iran: Potential importance of regional differences in H. pylori-associated disease. J Clin Microbiol. 2008;46:1774–9. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01737-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nimri LF, Matalka I, Bani Hani K, Ibrahim M. Helicobacter pylori genotypes identified in gastric biopsy specimens from Jordanian patients. BMC Gastroenterol. 2006;6:27. doi: 10.1186/1471-230X-6-27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Al Qabandi A, Mustafa AS, Siddique I, Khajah AK, Madda JP, Junaid TA, et al. Distribution of vacA and cagA genotypes of Helicobacter pylori in Kuwait. Acta Trop. 2005;93:283–8. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2005.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sadjadi A, Derakhshan MH, Yazdanbod A, Boreiri M, Parsaeian M, Babaei M, et al. Neglected role of hookah and opium in gastric carcinogenesis: A cohort study on risk factors and attributable fractions. Int J Cancer. 2014;134:181–8. doi: 10.1002/ijc.28344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pakseresht M, Forman D, Malekzadeh R, Yazdanbod A, West RM, Greenwood DC, et al. Dietary habits and gastric cancer risk in North-West Iran. Cancer Causes Control. 2011;22:725–36. doi: 10.1007/s10552-011-9744-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pourfarzi F, Whelan A, Kaldor J, Malekzadeh R. The role of diet and other environmental factors in the causation of gastric cancer in Iran – A population based study. Int J Cancer. 2009;125:1953–60. doi: 10.1002/ijc.24499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.González C, Jakszyn P, Pera G, Agudo A, Bingham S, Palli D, et al. Meat intake and risk of stomach and esophageal adenocarcinoma within the European Prospective Investigation Into Cancer and Nutrition (EPIC) J Natl Cancer Inst. 2006;98:345–54. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djj071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]