Abstract

Background:

Community-based care, underpinned by relevant primary care research, is an important component of the global fight against non-communicable diseases. The International Primary Care Research Group's (IPCRG's) Research Needs Statement identified 145 research questions within five domains (asthma, rhinitis, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), smoking, respiratory infections).

Aims:

To use an e-mail Delphi process to prioritise the research questions.

Methods:

An international panel of primary care clinicians scored the clinical importance, feasibility, and international relevance of each question on a scale of 1–5 (5 = most important). In subsequent rounds, informed by the Group's median scores, participants scored overall priority. Consensus was defined as 80% agreement for priority scores 4 or 5.

Results:

Twenty-three experts from 21 countries completed all three rounds. Sixty-two questions were prioritised across the five domains. A recurring theme was for ‘simple tools’ (e.g. questionnaires) enabling diagnosis and assessment in community settings, often with limited access to investigations. Seven questions recorded 100% agreement: these involved pragmatic approaches to the diagnosis of COPD and rhinitis, assessment of asthma and respiratory infections, management of rhinitis, and implementing asthma self-management.

Conclusions:

Evidence to underpin the primary care approach to diagnosis and assessment and broad management strategies were overarching priorities. If primary care is to contribute to the global challenge of managing respiratory non-communicable diseases, policymakers, funders, and researchers need to prioritise these questions.

Keywords: non-communicable diseases, primary care, research priorities, respiratory medicine, IPCRG

Introduction

In September 2011 the General Assembly of the United Nations (UN) adopted a declaration on the Prevention and Control of Non-communicable Diseases (NCDs) which highlighted the ‘rapidly growing magnitude of NCDs affecting people of all ages, gender, race and income levels’.1 Acknowledging that the impact of NCDs (specifically including chronic respiratory disease) could be ‘significantly reduced’, the UN declaration encouraged a range of political, societal, and healthcare initiatives ‘especially at the primary healthcare level’. Professional organisations actively supported the campaigning that led to this initiative.2–4

Pre-empting the UN call for facilitation of translational research to inform national and global action,1 research agendas have been published from different professional and geographical perspectives.4–6 In line with the Action Plans of the World Health Organization, these emphasise the pivotal importance of evidence-based primary healthcare,7,8 although none explores the challenge specifically from the primary care perspective.

In June 2010 the International Primary Care Respiratory Group (IPCRG) began the process of addressing this gap by publishing a Research Needs Statement (RNS).9 It was hoped that the statement would be used by clinicians and patients campaigning for answers to questions relevant to the delivery of respiratory care in the community, to support researchers seeking funding to provide answers to these questions, and to inform funding bodies prioritising research agendas. An overarching theme was the need for research undertaken within primary care, recruiting participants representative of primary care populations, evaluating interventions realistically delivered over appropriate timescales within primary care, and drawing conclusions that will be meaningful to professionals working within primary care. The recent surge of interest in ‘real-life’ research reflects the importance of this agenda.10–12

Development of the IPCRG Research Needs Statement

The list of research questions in the RNS was compiled using an informal but inclusive consultation process.9 Draft statements in asthma, rhinitis, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), tobacco dependence, and respiratory infections were circulated widely to a total of 42 participants from 22 countries including IPCRG members, other recognised experts, and representatives from a range of economic and healthcare backgrounds. Following an iterative process, a total of 145 questions was generated across five disease areas (asthma, n=47; allergic rhinitis, n=26; COPD, n=35; tobacco dependence, n=16; respiratory infections, n=21). Disease-specific questions focused on effective and cost-effective ways to prevent disease, confirm a diagnosis, assess control, manage treatment, and empower self-management. Practical questions were highlighted about how to deliver this comprehensive agenda in the diverse primary care settings of low and middle income countries as well as relatively well-resourced healthcare systems.

Within this broad agenda, however, there was a need to prioritise and, in 2011, the IPCRG commissioned an e-Delphi consensus process to identify the priority research questions in each disease domain of the RNS.

Methods

Ethics

We were advised by the South East Scotland research ethics service that we did not require ethical approval for this study (personal communication, 17 December 2010).

e-Delphi methodology

Originating from the RAND Corporation in the 1950s,13 the Delphi method is a technique for reaching consensus among experts about topics for which there is limited evidence.14–17 The underlying concept is that an expert panel is recruited, the members of which contribute ideas and then rank suggestions in successive rounds until predefined consensus is reached. In each round, responses are influenced by summary feedback from previous rounds; however, the panellists work independently and their contributions are anonymous, thus giving equal weight to all perspectives and overcoming the potential bias introduced by powerful opinionated minorities in consensus meetings.17 As face-to-face discussion is not required, the exercise can be administered by e-mail. The technique has been widely used in a range of healthcare contexts including defining the components of an anaphylaxis plan,18 identifying safety standards of GP computer systems,19 and prioritising research needs within the UK.20

The IPCRG e-Delphi

We undertook an international e-Delphi exercise which differed from the classic description in two important ways:

We omitted the first step in which the expert panel is asked open questions and invited to contribute ideas for subsequent ranking.14,16 Instead, we started with the 145 research questions of the RNS which had already been generated by wide discussion among international experts in the field.

A number of constructs (clinical importance, feasibility, and international relevance) were identified by the international research team as contributing to the final ranking of the priority of the research questions. To ensure that participants considered all three aspects, in the first round we asked the panel to score each question against each of the three constructs and then in the second and subsequent rounds to take an overview of the rankings as a priority for the IPCRG.

Recruitment of an expert panel

The IPCRG is an umbrella organisation for 18 national primary care respiratory organisations and 28 individual associate members from countries with no national organisation. To achieve a broad geographical spread, we aimed to recruit an expert panel with representatives of primary care-based clinicians from our member countries and as many as possible of the associated countries, ensuring that we also encompassed relevant clinical, research, and educational expertise.15,17 We compiled a list of:

Authors and contributors of the RNS (excluding the team conducting the Delphi exercise).

Members of the IPCRG research sub-committee and research network.

Representatives of the member and associate member countries.

Members of the IPCRG education sub-committee and panel.

After removing duplication, the potential pool was 63 people from 34 countries. An e-mailed invitation was sent to all potential members which included a description of the process, the anticipated timescale, and the estimated commitment. We made it clear that we expected participants to contribute to all three rounds.

Piloting

We piloted the process to ensure that the instructions were clear, data collection was feasible, and the process of data entry, analysis and feedback of results at each round was streamlined. Minor adjustments were made to the instructions to improve clarity.

The e-Delphi consensus process

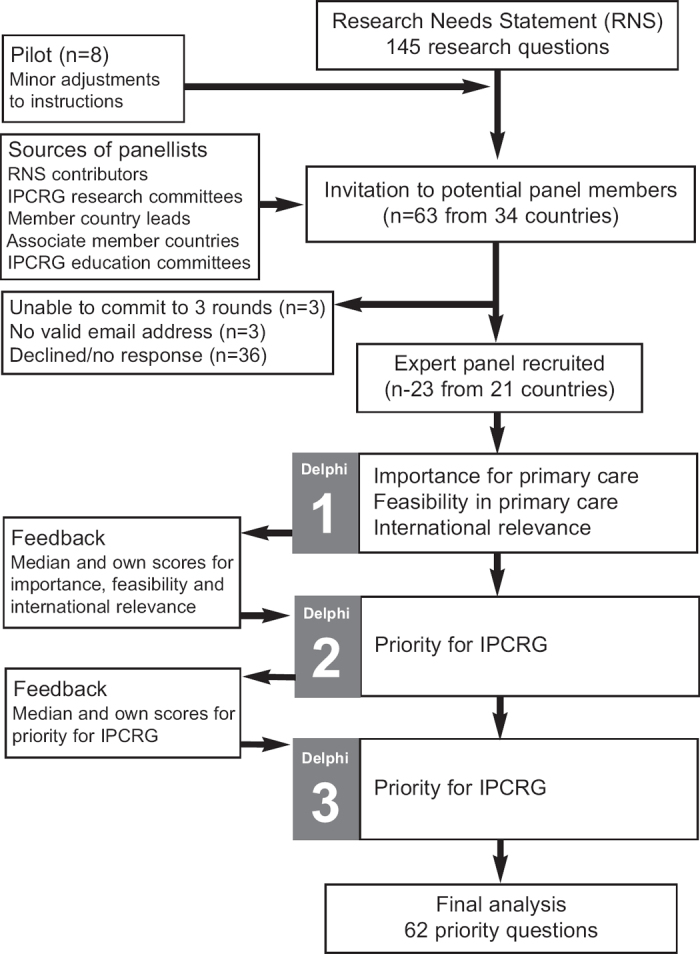

Figure 1 illustrates the flow of the e-Delphi consensus process which took place over 5 months in Spring 2011. In each of the three rounds, panel members were asked to return their completed spreadsheets within 2 weeks, with a reminder being sent a few days before the deadline. A second reminder was sent to non-responders the day after the due date with a 3-day deadline.

Figure 1. Flow diagram of the e-Delphi process.

Round 1

The research questions were reproduced verbatim from the RNS on an Excel spreadsheet (Microsoft Corporation, Washington, USA). Panel members were asked to score each research question on a scale of 1–5 against three constructs (where 1 is the least and 5 is the most important/feasible/international ly relevant).

Importance for primary care practice: Participants were asked to answer the following question from their perspective as a primary care clinician and/or researcher. “How important is it for improving the care of people with respiratory conditions in your healthcare system to have the answer to this question?”

Feasibility to be conducted in primary care: Participants were asked to consider the following question from their perspective as a primary care clinician and/or researcher. “How feasible do you think a research project in this area would be in your healthcare setting?”

Potential for international collaboration: “What is the potential for collaborative research to answer this question involving a number of countries, either working together or comparing between healthcare systems?”

The results were collated onto an Excel spreadsheet and a median score was calculated for each of the three constructs.

Round 2

The second round spreadsheet included the median scores from round 1 for each of the three constructs as well as the participant's own score. Respondents were asked to trade off or balance the importance, feasibility, and international relevance of each question and to decide on the priority of each question for the IPCRG.

Overall priority: Participants were asked to score the overall priority for the IPCRG (“Which of these research questions should the IPCRG invest time, money and effort in trying to answer?”), allocating a score of 1–5 (where 1 is the lowest and 5 is the highest priority).

The results were collated onto an Excel spreadsheet and an overall median score was calculated for each research question.

Round 3

The median scores for each question were entered onto the round 3 spreadsheet and fed back to individual panel members along with their own score.14 Panel members were then given the opportunity to revise their opinions on the overall priority of each question for the IPCRG in the light of the findings of the previous round by again ranking each research question on a score of 1–5.

Analysis of data

We calculated median scores for each of the questions and the proportion of respondents agreeing that the question was a priority.17 Consensus was defined a priori as 80% agreement for the priority score of 4 or 5. We anticipated that three rounds would allow an acceptable degree of agreement on research priorities but, if not, a final fourth round using the format of round 3 would be undertaken.

In order to enable overarching themes to be identified, four members of the research team (HP, BS, IT, AO) coded the questions into categories (e.g. diagnosis, management, organisation of care). Disagreements were resolved by negotiation.

Results

We recruited 23 participants from 21 countries to the expert panel. Table 1 lists the countries of origin and professional background of the participants. Participants included 11 (61%) of the IPCRG member countries and 10 (36%) of the associate member countries. All the participants completed all three rounds.

Table 1. Countries of origin and professional background of the expert group.

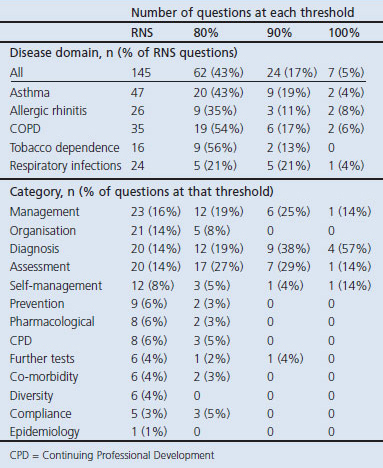

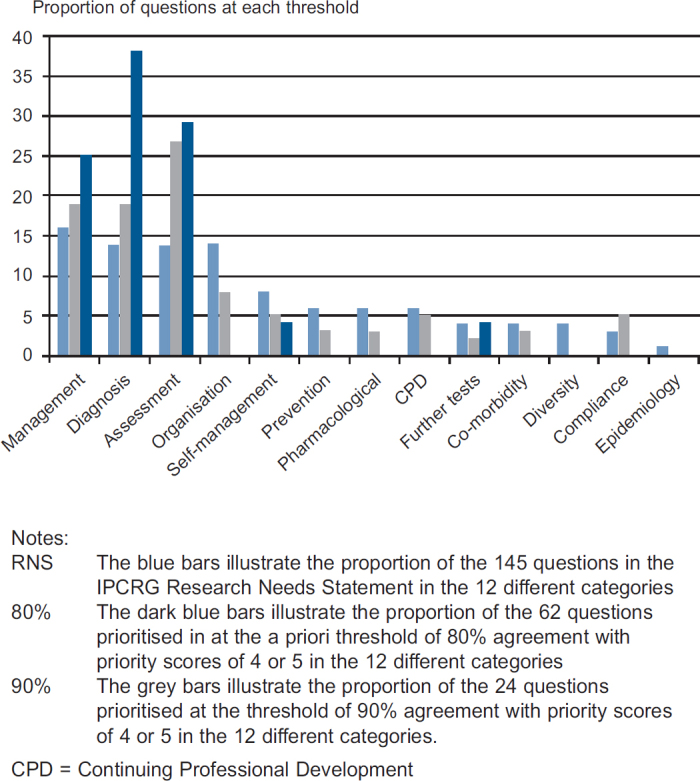

Proportion reaching consensus thresholds

Of the 145 research questions, 62 achieved the a priori consensus level of 80% agreement with priority scores of 4 or 5. Seven questions achieved 100% agreement and 24 reached a consensus threshold of 90%. The prioritised questions were evenly distributed across all five disease domains (Table 2).

Table 2. Number of questions prioritised in each domain and category.

Prioritised questions in each disease domain

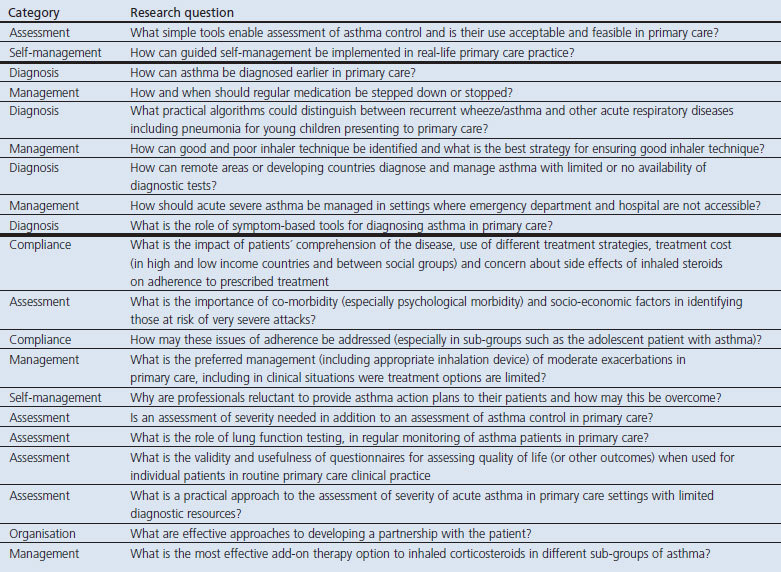

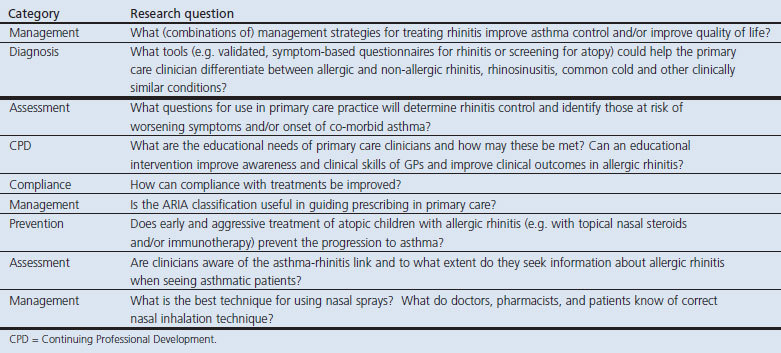

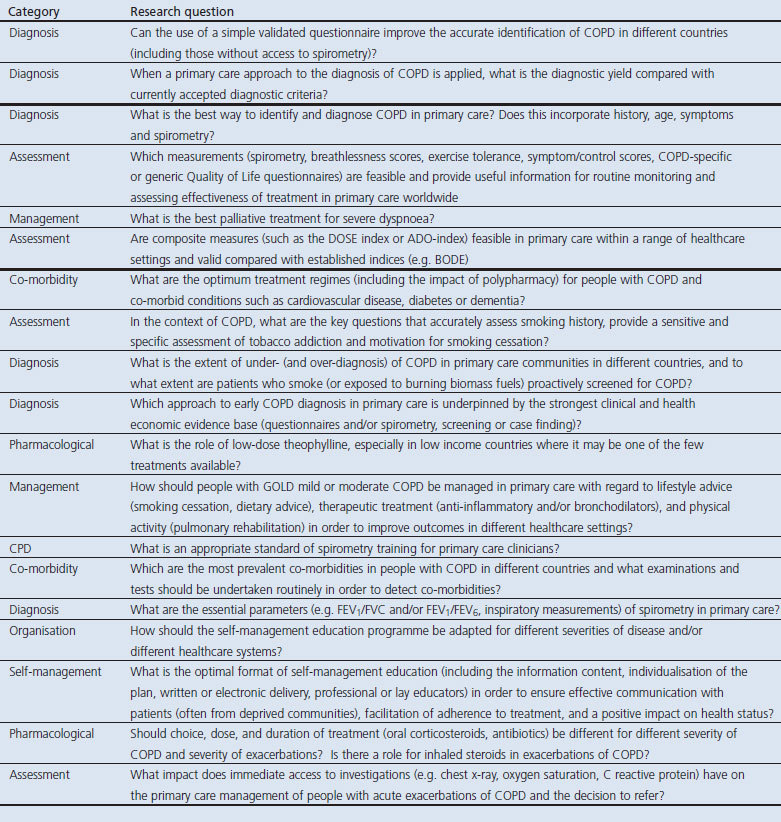

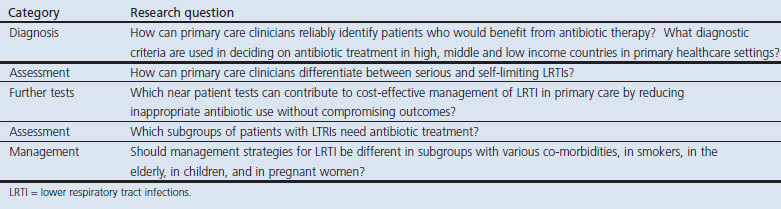

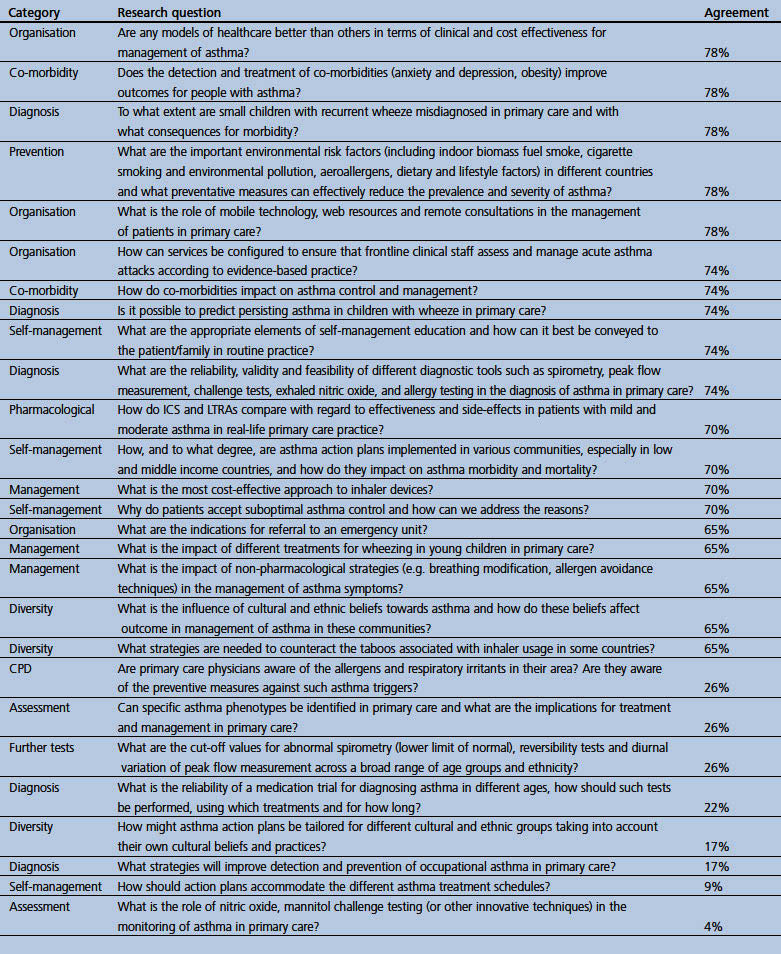

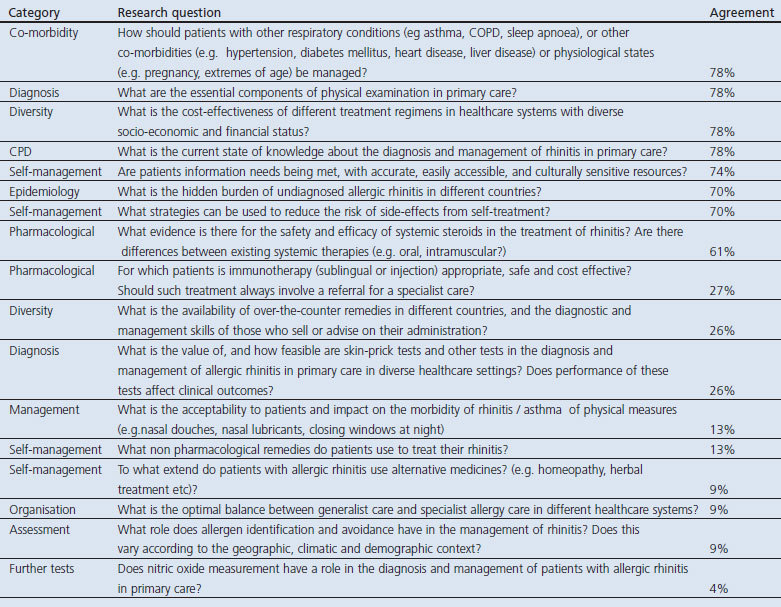

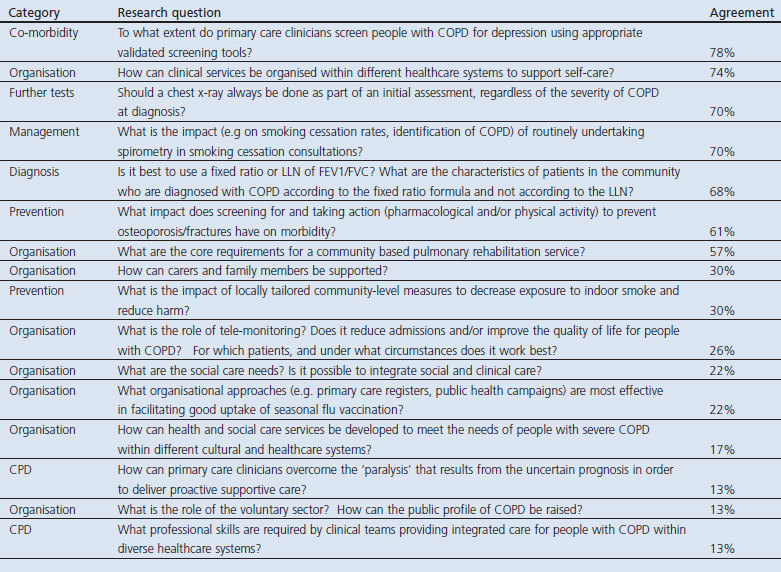

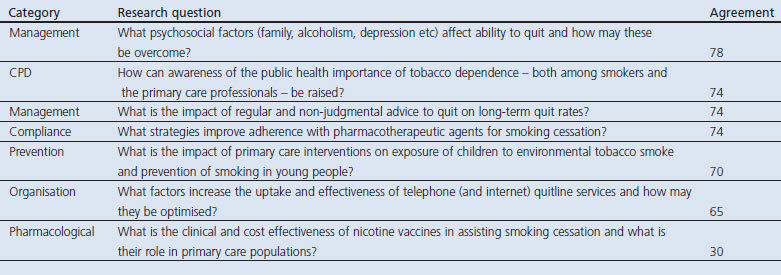

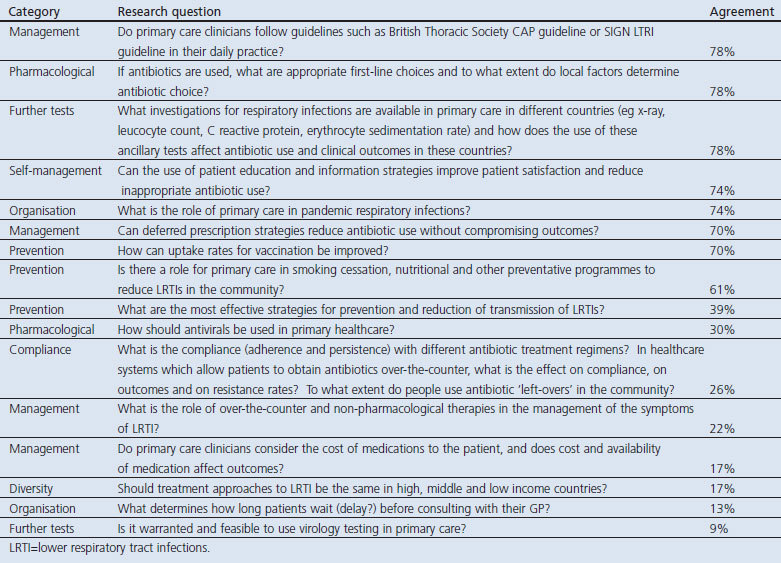

The 62 questions in the five disease domains prioritised at the 80% threshold are listed in Tables 3,4,5,6,7. All the seven questions achieving 100% consensus emphasised the need for a practical ‘primary care approach’. Two questions were in the asthma domain ('simple' tools for assessing control and implementing self-management), two in the allergic rhinitis domain (diagnosing the cause of nasal symptoms and management strategies), two in the COPD domain (diagnosis in primary care) and one in the respiratory infections domain (identifying when antibiotics were indicated). The 83 questions not prioritised are listed in Appendices 1,2,3,4,5, available online at www.thepcrj.org.

Table 3. Consensus on the research priorities in asthma listed in rank order.

Table 4. Consensus on the research priorities in allergic rhinitis listed in rank order.

Table 5. Consensus on the research priorities in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) listed in rank order.

Table 6. Consensus on the research priorities in tobacco dependence listed in rank order.

Table 7. Consensus on the research priorities in respiratory infections listed in rank order.

Over-arching themes

The questions were allocated to 12 categories (listed in Table 2). Comparison of the relative proportion of questions from each category prioritised at the 80% and 90% thresholds with the 145 questions of the RNS illustrates the prioritisation process; for example, 40 (28%) of the 145 questions in the RNS related to diagnosis or assessment. These questions were actively prioritised, accounting for 29 (46%) of the 62 questions which achieved consensus at the 80% level and 16 (67%) of the 24 questions achieving 90% agreement. This process is illustrated for each of the categories in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Prioritisation of the different categories of questions.

Discussion

Main findings

The five disease areas all included priorities for the international primary care expert group in our study and a range of specific questions were highlighted within each domain. A number of overarching priorities could be identified. The need for ‘simple tools’ for establishing a diagnosis and assessing severity within low-technology consultations in primary care were prioritised over more complex investigations, broad management strategies were of more interest than evidence about efficacy of individual treatments, and practical approaches were sought for supporting self-management and lifestyle change.

Strengths and limitations of this study

Our expert panel of 23 primary care clinicians is unlikely to have represented the full range of perspectives from community-based care globally. In many countries primary healthcare is poorly developed with no co-ordinating body that can represent their views, and other techniques will be required to explore their views. However, our participants were all actively involved in primary care and represented 21 countries with a broad range of economic backgrounds and healthcare systems. This is a similar number to expert panels in other reported e-Delphi studies.18,19 Importantly, all the participants contributed to all three rounds, enabling a consensus to be reached.

We did not formally request free text contributions (although suggestions could have been made in the covering e-mail) because the aim of the e-Delphi process was to prioritise the existing questions from the RNS which had already attracted contributions from the global membership of the IPCRG.9

Categorising the questions proved useful for identifying overarching themes but had the limitation that some questions could have fitted more than one category. For example, some of the questions coded as ‘management’ overlapped with ‘organisation of care’. Although it was an overarching theme of the RNS,9 we did not include a category for guideline implementation because the relevant questions were already included as disease-specific priorities.

Interpretation of findings in relation to previously published work

In line with global priorities,1,3,4,7,8 a recently published research agenda for prevention and control of chronic respiratory diseases from the public health perspective highlighted the role of primary care in meeting the challenge of respiratory NCDs.5 Our findings complement this paper by defining the evidence needed to inform management of common respiratory conditions in primary care settings. There was universal agreement (from relatively well-resourced healthcare systems as well as low and middle income countries) that there was a need in all the disease domains to understand better the role of asking the right questions, using questionnaires and ‘simple’ investigations readily available in all surgeries to identify, diagnose, and assess patients with respiratory disease. This was not to downgrade the importance of diagnostic investigations (indeed, achieving standards for primary care spirometry was one of the prioritised questions) but recognises that access to such investigations may be limited in many healthcare systems and that there is a need to maximise the potential of what can be achieved with minimal equipment in a consultation. A recent example which resonates with the stepwise approach to diagnosing respiratory disease advocated by the Global Alliance against Chronic Respiratory Diseases4 is the identification of potential COPD with a short questionnaire and a Piko-6® meter enabling targeted spirometry.21

The recognised challenge of diagnosing community-acquired pneumonia in primary care and, more pragmatically, deciding which patients with chest infections should be treated with antibiotics was highlighted as a research priority by our expert panel. A recent consensus initiative has developed definitions of respiratory infections which ‘maintain relevance to everyday practice and are not over-reliant on investigations’ which it is hoped will be more resonant with the needs of primary care research and clinical practice.22 Reinforcing the overarching theme of adopting a ‘primary care approach’, adapting evidence from hospital settings may be unhelpful. For example, the CRB-65 score23 designed to predict outcome in confirmed pneumonia in secondary care has been shown not to be helpful to the primary care clinician deciding on a management strategy without the benefit of a chest x-ray.24

Overall management strategies were of more interest than the efficacy of specific drugs or treatments, reflecting the recent interest in ‘real-life’ studies.11,12 Such studies not only inform the use of different therapeutic options in unselected populations9 but also provide evidence for how care may be organised to meet the needs of practice populations.25 Guidelines, typically reliant on evidence from traditional randomised clinical trials, are complemented by real-world studies to inform implementation.26,27

Implications for future research, policy and practice

Policy documents and research agendas universally agree that primary care is an important component of the fight against NCDs.1,3,4,5,7,8 Our prioritisation exercise contributes to the debate by highlighting the basic pragmatic questions which tax primary care clinicians globally. Crucially, evidence is needed about how — with only the ‘simple’ tools available in a consultation — a diagnosis may be suspected and a known respiratory condition assessed. Effective management strategies need to be informed by research recruiting populations typical of the broad spectrum of primary care.

It is our hope and expectation that this global prioritisation exercise will act as a stimulus to researchers, funders, and commissioners to focus research efforts on the areas of greatest need. Reflecting the diversity of healthcare systems in low, middle, and high income countries, many of the priority areas can be addressed by appropriately designed and funded projects in individual countries tailored to local recruitment, feasibility, sociocultural, and funding issues. Some priorities may be best addressed through multinational collaboration. Although the IPCRG is unable to commission or fund projects systematically, it can focus its expertise and support on small-scale pilot work which underpins programmes of work in line with the priorities, and broker international collaboration such as the UNLOCK project.28 The IPCRG research network will continue to monitor, assess, and highlight ongoing primary care research needs, thus providing a robust platform on which grass-root level researchers can build as they seek to justify their projects to funding authorities.

Conclusions

The hope was expressed with the launch of the RNS that it would influence funders and researchers to prioritise real-life primary care respiratory research. In an era when ‘comprehensive strengthening’ of primary care is seen as an important component of the global response to the increasing burden of NCDs,1,29 this hope must become a reality.

Acknowledgments

Handling editor Maureen George

Funding The International Primary Care Respiratory Group supported the administration of the e-Delphi. HP is supported by a Primary Care Research Career Award from the Chief Scientist's Office, Scottish Government. MT's academic position is supported by Asthma UK.

We are grateful to all the members of the expert panel who gave their time and responded to the three rounds within the tight timeframe that we gave them: Niels H Chavannes, The Netherlands; Javiera Corbalan, Chile; Jaime Correia de Sousa, Portugal; John Fardy, Australia; Antonio Infantino, Italy; Alan Kaplan, Canada; Elzbieta Kryj-Radziszewska, Poland; Arnulf Langhammer, Norway; Elena Latysheva, Russia; Tan Tze Lee, Singapore; Christos Lionis, Greece; Karen Lisspers, Sweden; Charles Llor, Spain; Catalina Panaitescu, Romania; David Price, UK; Jim Reid, New Zealand; Sundeep Salvi, India; Antonius Schneider, Germany; Laura Stacul, Argentina; Marianne Stubbe Ostergaard, Denmark; Ron Tomlins, Australia; Nguyen Nhu Vinh, Vietnam; Hakan Yaman, Turkey. We also thank Professor Aziz Sheikh, Dr Allison Worth and Dr Elizabeth Grant for their helpful comments on an earlier draft. Katie Searles undertook the administration.

Appendix 1. Research questions in asthma which did not reach 80% consensus threshold

Appendix 2. Research questions in allergic rhinitis which did not reach 80% consensus threshold

Appendix 3. Research questions in COPD which did not reach 80% consensus threshold

Appendix 4. Research questions in tobacco dependence which did not reach 80% consensus threshold

Appendix 5. Research questions in respiratory infections which did not reach 80% consensus threshold

Footnotes

HP has received fees for lecturing or attending advisory groups from GlaxoSmithKline (GSK), AstraZeneca, Boeringher Ingelheim and has been sponsored to attend conferences by AstraZeneca, Boeringher Ingelheim/Pfizer, Napp pharmaceuticals. DR has received sponsorship from, lectured on behalf of or provided consultancy to AstraZeneca, ALK Abello, Novartis, Uriach, Mundipharma, Orion Pharma, MSD, Pfizer, Boehringer Ingelheim, and Almirall. He is Allergy lead for both the PCRS (UK) and PCRG. He is employed as clinical lead for COPD by East Midlands Strategic Health Authority and as Respiratory Commissioning lead by East and West CCGs. BS has received payment for lectures by AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Pfizer and MSD, for development of educational presentations by AstraZeneca and MSD, and payment for national consultancy meetings with AstraZeneca, MSD, Boehringer Ingelheim, Nycomed, and GSK. Neither MT nor any member of his close family has any shares in pharmaceutical companies. He has received speaker's honoraria for speaking at sponsored meetings from the following companies marketing respiratory and allergy products: AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingleheim, GSK, MSD, Napp, Schering-Plough, and Teva. He has received honoraria for attending advisory panels with AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingleheim, GSK, MSD, Merck Respiratory, Schering-Plough, Teva, Abbott, and Novartis. He has received sponsorship to attend international scientific meetings and has received funding for research projects from GSK, MSD, and AstraZeneca. He held a research fellowship and is Chief Medical Advisor to Asthma UK. He is a member of the UK Department of Health Asthma Strategy Group and Home Oxygen Group, the MHRA Respiratory and Allergy Expert Advisory Group, the BTS SIGN Asthma Guideline Group, and the EAAACI Rhinosinusitis (EPOS) Guideline Group. SW is Executive Officer of the IPCRG, a charity that has as its mission the dissemination of research for the public good. We hope that publication of this study may increase global investment in real-life pragmatic respiratory research and IPCRG may be one of the beneficiaries of that investment. She declares this interest, although does not judge it to be a conflict. AO, MRR, IT, and OY have declared no conflicts of interest.

References

- United Nations General Assembly: Sixty-sixth session. Political declaration of the High-level Meeting of the General Assembly on the Prevention and Control of Non-communicable Diseases. New York: United Nations, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- International Primary Care Respiratory Group. IPCRG campaigns. http://www.theipcrg.org/campaigns/index.php (accessed October 2011).

- Non-Communicable Disease Alliance. Proposed outcomes document for the United Nations high level summit on non-communicable diseases. Geneva: NCD Alliance, 2010. http://www.ncdalliance.org/od (accessed October 2011). [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Global Alliance against Chronic Respiratory Diseases. Global surveillance, prevention and control of chronic respiratory diseases: a comprehensive approach. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Bousquet J, Kiley J, Bateman ED, et al. Prioritised research agenda for prevention and control of chronic respiratory diseases. Eur Respir J 2010;36:995–1001. http://dx.doi.org/10.1183/09031936.00012610 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCarthy M, Maher D, Ly A, Ndip A. Developing the agenda for European Union collaboration on non-communicable diseases research in sub-Saharan Africa. Health Res Policy Syst 2010;8:13. http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1478-4505-8-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. 2008-2013 Action Plan for the global strategy for the prevention and control of non-communicable diseases. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Global alliance against chronic respiratory diseases. Action Plan 2008-2013. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Pinnock H, Thomas M, Tsiligianni I, et al. The International Primary Care Respiratory Group (IPCRG) Research Needs Statement 2010. Prim Care Respir J 2010;19(Suppl 1):S1–S21. http://dx.doi.org/10.4104/pcrj.2010.00021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price D, Musgrave SD, Shepstone L, et al. Leukotriene antagonists as first-line or add-on asthma-controller therapy. N Engl J Med 2011;364:1695–707. http://dx.doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1010846 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dahlén S-E, Dahlén B, Drazen JM. Asthma treatment guidelines meet the real world. N Engl J Med 2011;364:1769–70. http://dx.doi.org/10.1056/NEJMe1100937 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ducharme FM. Leukotriene receptor antagonists as first line or add-on treatment for asthma. BMJ 2011;343:d5314. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bmj.d5314 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalkey N, Helmer O. An experimental application of the Delphi method to the use of experts. Manage Sci 1963;9:458–67. http://dx.doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.9.3.458 [Google Scholar]

- Hasson F, Keeney S, McKenna H. Research guidelines for the Delphi survey technique. J Advanced Nursing 2000;32:1008–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okoli C, Pawlowski SD. The Delphi method as a research tool: an example, design considerations and applications. Inform Manage 2004;42:15–29. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.im.2003.11.002 [Google Scholar]

- Powell C. The Delphi technique: myths and realities. J Advanced Nursing 2003;41:376–82. http://dx.doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2648.2003.02537.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy MK, Sanderson CFB, Black NA, et al. Consensus development methods and their use in clinical guideline development. Health Technol Assess 1998;2(3):1–88. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Worth A, Nurmatov U, Sheikh A. Key components of anaphylaxis management plans: consensus findings from a national electronic Delphi study. J R Soc Med Sh Rep 2010;1:42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avery AJ, Savelyich BSP, Sheikh A, et al. Identifying and establishing consensus on the most important safety features of GP computer systems: e-Delphi study. Informatics Prim Care 2005;13:3–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheikh A, Major P, Holgate ST. Developing consensus on national respiratory research priorities: key findings from the UK Respiratory Research Collaborative's e-Delphi exercise. Respir Med 2008;102:1089–92. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.rmed.2008.03.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sichletidis L, Spyratos D, Papaioannou M, et al. A combination of the IPAG questionnaire and PiKo-6® flow meter is a valuable screening tool for COPD in the primary care setting. Prim Care Respir J 2011;20:184–9. http://dx.doi.org/10.4104/pcrj.2011.00038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greene G, Hood K, Little P, et al. Towards clinical definitions of lower respiratory tract infection (LRTI) for research and primary care practice in Europe: an international consensus study. Prim Care Respir J 2011;20:299–306. http://dx.doi.org/10.4104/pcrj.2011.00034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim WS, Baudouin SV, George RC, et al. BTS guidelines for the management of community acquired pneumonia in adults: update 2009. Thorax 2009;64(Suppl 3):iii1–55. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/thx.2009.121434 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Francis NA, Cals JW, Butler CC, et al, on behalf of the GRACE Project Group. Severity assessment for lower respiratory tract infections: potential use and validity of the CRB-65 in primary care. Prim Care Respir J 2012;21(1):65–70. http://dx.doi.org/10.4104/pcrj.2011.00083 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinnock H, Adlem L, Gaskin S, Harris J, Snellgrove C, Sheikh A. Accessibility, clinical effectiveness and practice costs of providing a telephone option for routine asthma reviews: controlled implementation study. Br J Gen Pract 2007;57:714–22. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holgate S, Bisgaard H, Bjermer L, et al. The Brussels Declaration: the need for change in asthma management. Eur Respir J 2008;32:1433–42. http://dx.doi.org/10.1183/09031936.00053108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olesen F. Putting research into clinical practice. BMJ 2011;343:d3922. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bmj.d3922 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chavannes N, Stallberg B, Lisspers K, et al. UNLOCK: Uncovering and Noting Long-term Outcomes in COPD to enhance Knowledge. Prim Care Respir J 2010;19:408. http://dx.doi.org/10.4104/pcrj.2010.00084 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Global status report on non-communicable diseases 2010. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2010. [Google Scholar]