Abstract

Summary:

Many factors can impair asthma control. One which is frequently overlooked is rhinitis. Asthma patients with significant rhinitis are over four times more likely to have poorly controlled asthma than those without. Over 80% of patients with asthma have rhinitis, which may be allergic or inflammatory/non-allergic. Both types of rhinitis share pathophysiological similarities with eosinophilic asthma, cause bronchial hyper-reactivity, and are predisposing factors for the subsequent development of asthma. Nasal allergen challenge in allergic rhinitis results in inflammation in the bronchi as well as the nose, and the reverse is also true. This article reviews briefly the evidence for the link between asthma and rhinitis, advocates looking for rhinitis when patients present with poorly controlled asthma, and provides guidance for the diagnosis and treatment of rhinitis.

Keywords: rhinitis, asthma, co-morbidity, diagnosis, treatment, airway inflammation

Introduction: the difference between asthma severity and asthma control

National and international asthma treatment guidelines have previously focused on the assessment and classification of the severity of symptoms.1–4 Evidence now suggests that asthma severity is a variable feature of a patient's condition and may fluctuate over months or years,5,6 possibly leading to underestimation of severity, inadequate therapy and increased morbidity. Findings from studies of discordance between asthma severity and symptoms/lung function, and between severity, inhaled corticosteroid (ICS) and reliever medication use,7 suggest that classification and treatment of asthma based on severity alone is inappropriate.

Clinical scenario.

A young woman has just moved into the area and has registered as a patient at your primary care practice. Two weeks later she attends your asthma clinic complaining that she is bothered by intermittent coughing at night and by chest tightness and wheezing if she has to hurry. She has to use her reliever salbutamol inhaler at least twice a day. She is a non-smoker and insists that she is using her inhaled corticosteroid (ICS) plus long-acting β2-agonist (LABA) inhaler regularly as directed. She is on no other medication and has had no recent change in her circumstances. Her inhaler technique is good. She has a family history of hay fever, and admits to occasional sneezing in the summer months.

One possibility is that she has concomitant rhinitis — like 80% of patients with asthma — and that this is presently untreated. On taking a history it becomes clear that rhinitis has not previously been considered and that she has not undergone examination or clinical tests to establish a diagnosis.

(Fictional clinical case; no signed consent form required)

In view of these considerations, and the demonstration in several studies that asthma control was achievable in most patients,8–13 the Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA) guidelines currently recommend treatment based on achieving and maintaining asthma control.1 This is defined as “the extent to which the manifestations of asthma have been reduced or removed by treatment” based on assessment of the dual components of current clinical control (e.g. symptoms, limitation of activities/ quality of life (QoL), reliever/rescue treatment use, and lung function) as well as future risk (e.g. exacerbations, decline in lung function, and side effects of treatment).14,15

The role of rhinitis in poor asthma control

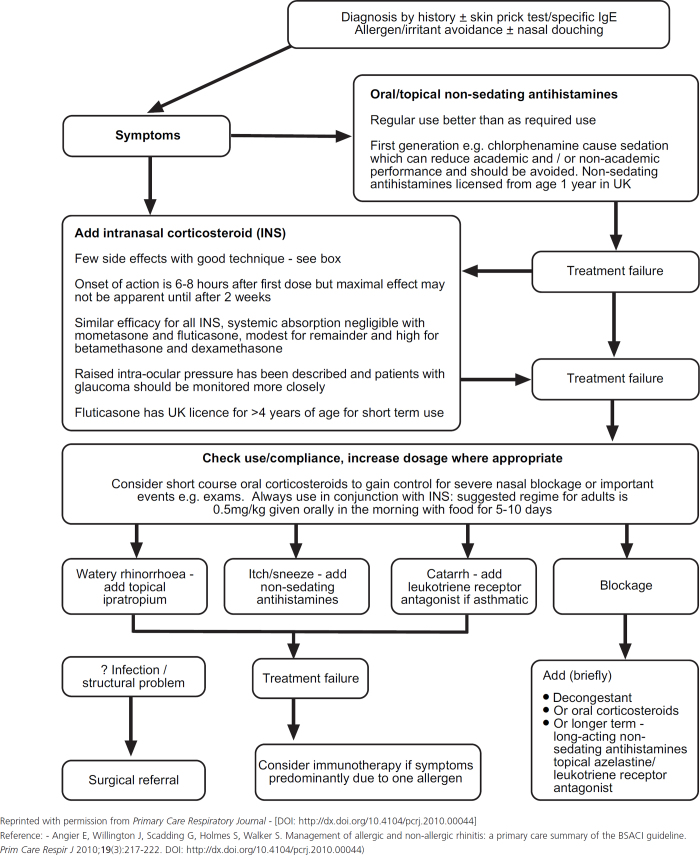

Although guideline-defined asthma control is achievable in the majority of patients under strict clinical trial conditions, in real life many patients with asthma continue to have symptoms and poor asthma control.1,16 The major reasons for this are summarised in Table 1.17,18 It is beyond the scope of this article to discuss in detail the evidence for each factor associated with inadequate asthma control. However, rhinitis is a common co-morbidity in many patients with asthma, and the role of uncontrolled rhinitis as a major contributory factor for poor asthma control has recently been highlighted in several studies.19–21 A survey in UK general practice recently showed that asthma patients with significant rhinitis were 4–5 times more likely to have poorly controlled asthma compared to patients without rhinitis, with an odds ratio greater than that for poor compliance with asthma therapy.19 Similarly, a survey of asthma outpatients indicated that chronic rhinitis was the most important risk factor associated with emergency room visits due to asthma exacerbations.20

Table 1. Reasons for continuing symptoms and poor asthma control.

Making the diagnosis of rhinitis

The cardinal symptoms of rhinitis are rhinorrhoea (nasal discharge), nasal obstruction, itching and sneezing. The diagnosis of rhinitis can be confirmed by following a few simple steps.22 Useful diagnostic questionnaires are available at www.whiar.org.23

- Taking a specific history. Rhinitis can broadly be divided into three categories; allergic, infective and non-allergic.

- Sneezing, itchy nose and palate are likely signs of allergic rhinitis (AR).

- Rhinorrhoea can be due to allergen, viral/bacterial infections, alcohol, medications, malignancies, etc. Rarely, isolated rhinorrhoea can be a CSF leak.

- Nasal obstruction/blockage in alternating nostrils is a normal manifestation of rhinitis; bilateral blockage can occur with severe rhinitis, but is more common with nasal polyps.

- Unilateral symptoms are unlikely to be due to allergy, and referral to an ENT surgeon is wise.

- Bilateral itchy, red, swollen eyes are usually associated with AR.

Taking a family and social history. A family history of any allergic disease (e.g. summer hay fever) makes a diagnosis of AR and asthma more likely. Symptoms on exposure to relevant triggers such as pets, mould, occupational allergens, etc. gives further indication of the probable cause of rhinitis.

Physical examination. Observe the patient for reduced nasal airflow, mouth breathing, a horizontal nasal crease across the dorsum of the nose, and differences in contour of the nasal bridge. Examine for polyps, crusting, a perforated septum, or mucosal congestion, all of which can indicate persistent rhinitis.

Routine tests. Blood tests help to exclude other conditions as well as confirm some causes of rhinitis (e.g. thyroid function tests for nasal obstruction). Skin prick tests or serum specific immunoglobulin E (sIgE) tests can be useful to confirm sensitivity to avoidable triggers and are vital when considering avoidance regimes or allergen-specific treatments such as immunotherapy. Allergy tests are not diagnostic when considered independently of the clinical history and should not be used as a tool to ‘screen’ for allergic triggers.

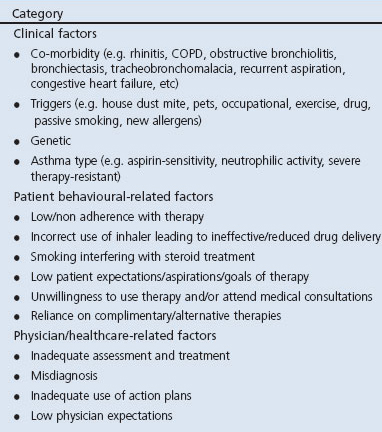

Figure 1. ARIA classification of allergic rhinitis.

What is the evidence for a link between rhinitis and asthma?

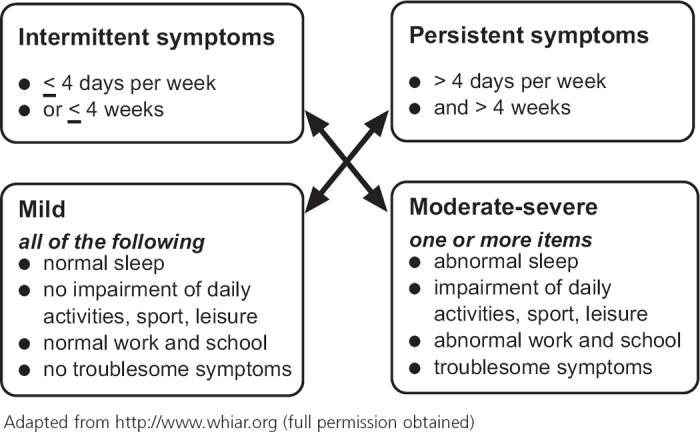

Epidemiological and pathophysiological studies have consistently indicated that rhinitis and asthma frequently co-exist21,24–49 (see Table 2).

Epidemiological studies have demonstrated that approximately 20–60% of patients with rhinitis have clinical asthma, while >80% of patients with allergic asthma have concomitant rhinitis symptoms.24–26 Based on the ARIA classification,23 about one-third of all AR patients have persistent symptoms.27

Pathophysiological studies have provided compelling evidence for both anatomical and physiological similarities between the nose and the bronchi,28–30 as well as there being common agents which can trigger both asthma and rhinitis exacerbations and lead to similar inflammatory responses.29,31,32 Indeed, evidence from some studies suggests that in 20–30% of patients with chronic allergic airway disease, allergen challenge in the upper airways results in significantly reduced lung function33 and increased bronchial responsiveness to methacholine.33,34 Furthermore, allergen challenge in the nasal or bronchial airways leads to marked inflammatory responses in the lower35,36 or upper airways.37,38 Recently, it has been suggested that systemic inflammation triggered by both the adaptive and innate immune system may be the major factor involved in initiating and perpetuating inflammation in combined airway diseases.39

Studies directly investigating the impact of AR on the incidence of asthma have further indicated that worsening AR negatively affects the course of asthma.19,21,40 One cross-sectional survey of over 4400 asthmatic patients recruited from 85 general practices in the UK indicated that the odds of having poor asthma control were more than doubled among patients with mild rhinitis and more than quadrupled among patients with severe rhinitis, compared to patients with no rhinitis.19

Studies investigating the effects of intranasal corticosteroids (INS) on asthma symptoms in subjects with co-morbid AR and asthma have reported conflicting results with regard to the benefits on asthma symptoms.41 Moreover, a meta-analysis of studies assessing the efficacy of INS failed to show a significant effect on asthma outcomes.42 A more recent study, however, has indicated that mometasone furoate nasal spray, a minimally bioavailable nasal corticosteroid, improved the quality of life (QoL) and the burden of respiratory symptoms in patients with persistent AR and asthma.43

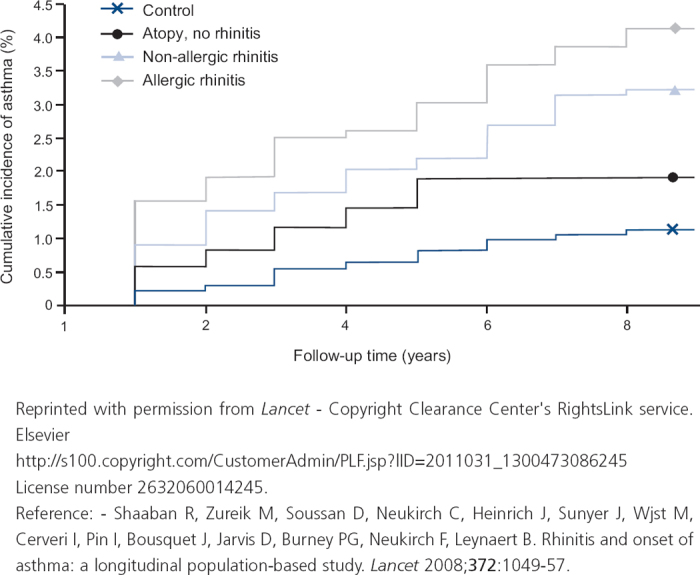

Rhinitis often precedes the development of asthma and is one of the strongest independent risk factors for the onset and incidence of asthma (see Figure 2).44

A considerable body of evidence suggests that AR is one of the strongest independent risk factors for asthma.44–49 Population-based longitudinal studies have demonstrated that childhood AR is associated with a significantly increased risk of incident asthma during pre-adolescence, middle age or adult life;47 whereas AR with sensitisation to mite44 and pet allergens and smoking48 is associated with an increased risk of onset of asthma.

Table 2. Evidence for a link between rhinitis and asthma.

Figure 2. Association of rhinitis with onset and incidence of asthma.

Asthma and rhinitis as co-morbid conditions

- What are the implications for primary care physicians?

- The presence of co-morbid rhinitis and asthma in the majority of patients with asthma may result in logistic, financial, diagnostic and management challenges for primary care. The logistic challenges are likely to be associated with more asthma-related GP visits and hospital referrals, with associated higher costs.50,51 Diagnostic and patient-management challenges, however, are less clear.

- Current guidelines recommend that people with asthma are assessed for rhinitis, and vice versa, so that their symptoms can be managed optimally.23

- This is important because, irrespective of the level of asthma control, patients with rhinitis symptoms have significantly worse health-related QoL compared to patients without, or with a low level of, rhinitis symptoms.52

- Co-existence of rhinitis and asthma may not be recognised by the patient or the clinician.

- Some patients do not perceive rhinitis symptoms as impairing their social life, school and work, and therefore do not complain or seek medical advice.23 Furthermore, it is important to distinguish between allergic and non-allergic symptoms as well as between persistent and/or moderate symptoms,23 since this may influence choice of pharmacotherapy. The diagnosis of asthma is also technically more complicated and it may be confused by the presence of cough caused by rhinitis and postnasal drip leading to either inaccurate diagnosis or assessment of asthma severity.53

- Increasing evidence suggests that better management of rhinitis may result in decreased asthma morbidity.

- Unlike the individual treatment strategies for rhinitis and asthma which are well established, the strategy and optimal therapeutic options for the treatment of co-morbid asthma and rhinitis are currently unclear — i.e. should each condition be treated individually or concurrently, and which therapy option should be employed? Current treatment options for asthma and rhinitis are similar and well documented, and include tertiary prevention (preventive strategies for management of established rhinitis and asthma), pharmacological treatments, and immunotherapy.23,54–56 Moreover, a review of studies investigating the efficacy of commonly employed pharmacological treatments of rhinitis on asthma outcomes has indicated that intranasal glucocorticosteroids, antihistamines, anti-leukotrienes and immunotherapy all have the potential to improve both rhinitis and asthma outcomes in patients with both conditions.55

- Guidelines indicate that pharmacological agents traditionally used for treatment of rhinitis may reduce asthma morbidity and thus they recommend a combined treatment strategy for the upper and lower airways for better efficacy:safety ratio.23

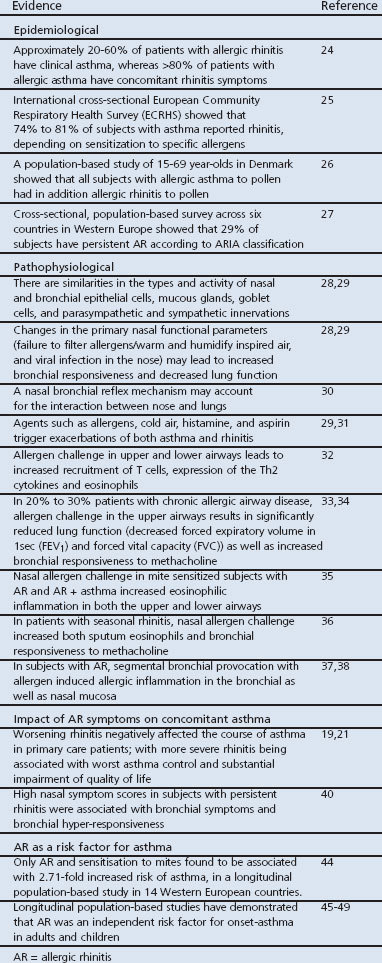

- Current rhinitis management guidelines recommend treatment according to an algorithm based on symptoms and severity (see Figure 3).22

- Oral/topical non-sedating antihistamines, and topical INS are the first-line medications of choice for mild and moderate/severe nasal symptoms, respectively. Cromone and antihistamine-containing eye drops can be used alone or in combination with the oral/topical non-sedating antihistamines and INS for ocular symptoms.

- Special care should be taken in pregnancy and young children, particularly with use of decongestants.

- To encourage compliance, all treatment options should be explained to patients and parents of children with rhinitis

- Compliance with treatment should be monitored regularly until patients reach a level of optimal symptom control

- To encourage compliance, all treatment options should be explained to patients and parents of children with rhinitis

- Diagnosis of co-morbid rhinitis and asthma

- Current guidelines recommend that people with asthma are assessed for rhinitis, and vice versa, so that their symptoms can be managed optimally.23

- This is important because, irrespective of the level of asthma control, patients with rhinitis symptoms have significantly worse health-related QoL compared to patients without, or with a low level of, rhinitis symptoms.52

- Co-existence of rhinitis and asthma may not be recognised by the patient or the clinician.

- Some patients do not perceive rhinitis symptoms as impairing their social life, school and work, and therefore do not complain or seek medical advice.23 Furthermore, it is important to distinguish between allergic and non-allergic symptoms as well as between persistent and/or moderate symptoms,23 since this may influence choice of pharmacotherapy. The diagnosis of asthma is also technically more complicated and it may be confused by the presence of cough caused by rhinitis and postnasal drip leading to either inaccurate diagnosis or assessment of asthma severity.53

- Increasing evidence suggests that better management of rhinitis may result in decreased asthma morbidity.

- Unlike the individual treatment strategies for rhinitis and asthma which are well established, the strategy and optimal therapeutic options for the treatment of co-morbid asthma and rhinitis are currently unclear — i.e. should each condition be treated individually or concurrently, and which therapy option should be employed? Current treatment options for asthma and rhinitis are similar and well documented, and include tertiary prevention (preventive strategies for management of established rhinitis and asthma), pharmacological treatments, and immunotherapy.23,54–56 Moreover, a review of studies investigating the efficacy of commonly employed pharmacological treatments of rhinitis on asthma outcomes has indicated that intranasal glucocorticosteroids, antihistamines, anti-leukotrienes and immunotherapy all have the potential to improve both rhinitis and asthma outcomes in patients with both conditions.55

- Guidelines indicate that pharmacological agents traditionally used for treatment of rhinitis may reduce asthma morbidity and thus they recommend a combined treatment strategy for the upper and lower airways for better efficacy:safety ratio.23

- Current rhinitis management guidelines recommend treatment according to an algorithm based on symptoms and severity (see Figure 3).22

- Oral/topical non-sedating antihistamines, and topical INS are the first-line medications of choice for mild and moderate/severe nasal symptoms, respectively. Cromone and antihistamine-containing eye drops can be used alone or in combination with the oral/topical non-sedating antihistamines and INS for ocular symptoms.

- Special care should be taken in pregnancy and young children, particularly with use of decongestants.

- To encourage compliance, all treatment options should be explained to patients and parents of children with rhinitis

- Compliance with treatment should be monitored regularly until patients reach a level of optimal symptom control

- To encourage compliance, all treatment options should be explained to patients and parents of children with rhinitis

- Management of patients with co-morbid rhinitis and asthma

- Increasing evidence suggests that better management of rhinitis may result in decreased asthma morbidity.

- Unlike the individual treatment strategies for rhinitis and asthma which are well established, the strategy and optimal therapeutic options for the treatment of co-morbid asthma and rhinitis are currently unclear — i.e. should each condition be treated individually or concurrently, and which therapy option should be employed? Current treatment options for asthma and rhinitis are similar and well documented, and include tertiary prevention (preventive strategies for management of established rhinitis and asthma), pharmacological treatments, and immunotherapy.23,54–56 Moreover, a review of studies investigating the efficacy of commonly employed pharmacological treatments of rhinitis on asthma outcomes has indicated that intranasal glucocorticosteroids, antihistamines, anti-leukotrienes and immunotherapy all have the potential to improve both rhinitis and asthma outcomes in patients with both conditions.55

- Guidelines indicate that pharmacological agents traditionally used for treatment of rhinitis may reduce asthma morbidity and thus they recommend a combined treatment strategy for the upper and lower airways for better efficacy:safety ratio.23

- Current rhinitis management guidelines recommend treatment according to an algorithm based on symptoms and severity (see Figure 3).22

- Oral/topical non-sedating antihistamines, and topical INS are the first-line medications of choice for mild and moderate/severe nasal symptoms, respectively. Cromone and antihistamine-containing eye drops can be used alone or in combination with the oral/topical non-sedating antihistamines and INS for ocular symptoms.

- Special care should be taken in pregnancy and young children, particularly with use of decongestants.

- To encourage compliance, all treatment options should be explained to patients and parents of children with rhinitis

- Compliance with treatment should be monitored regularly until patients reach a level of optimal symptom control

- To encourage compliance, all treatment options should be explained to patients and parents of children with rhinitis

- How should you treat and monitor rhinitis in patients with poor asthma control?

- Current rhinitis management guidelines recommend treatment according to an algorithm based on symptoms and severity (see Figure 3).22

- Oral/topical non-sedating antihistamines, and topical INS are the first-line medications of choice for mild and moderate/severe nasal symptoms, respectively. Cromone and antihistamine-containing eye drops can be used alone or in combination with the oral/topical non-sedating antihistamines and INS for ocular symptoms.

- Special care should be taken in pregnancy and young children, particularly with use of decongestants.

- To encourage compliance, all treatment options should be explained to patients and parents of children with rhinitis

- Compliance with treatment should be monitored regularly until patients reach a level of optimal symptom control

- To encourage compliance, all treatment options should be explained to patients and parents of children with rhinitis

Figure 3. Algorithm for the treatment of rhinitis.

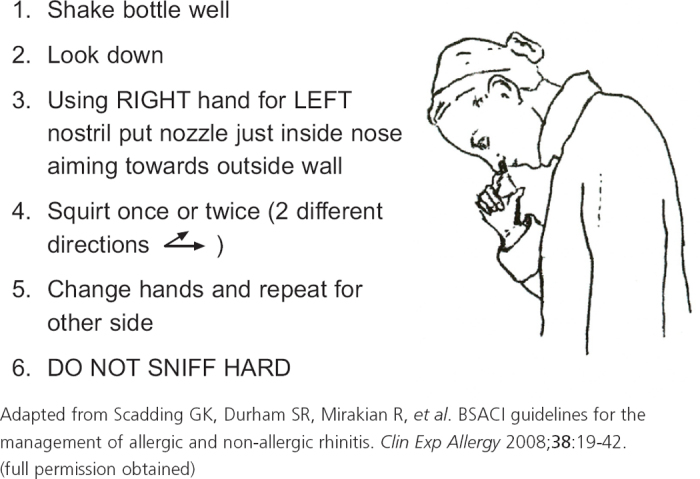

Figure 4. Correct procedure for using a nasal spray.

Conclusions

Substantial epidemiological and pathophysiological evidence indicates that rhinitis and asthma frequently occur as co-morbid conditions in adults and paediatric patients, and that they may be considered as different manifestations of the same inflammatory disease continuum. Rhinitis is a powerful predictor of adult-onset asthma and impacts negatively on the course of more severe asthma, worsening asthma control and impaired QOL as rhinitis severity increases, despite compliance with asthma treatment. Evidence suggests that more aggressive and better treatment of rhinitis is likely to improve asthma outcomes and asthma control, thus emphasising the ARIA-WHO recommendation that patients with asthma and rhinitis should be treated for both conditions. The combination of intranasal corticosteroids for persistent rhinitis and appropriate inhaled asthma therapy should be considered in such patients, with the addition of other drugs including cromones, anti-histamines and leukotriene receptor-antagonists as required. Overall steroid load should be reviewed on a regular basis to prevent unwanted side effects.

Acknowledgments

Funding Editorial assistance was funded by GSK.

Although not fulfilling the criteria for authorship, the authors gratefully acknowledge the editorial assistance provided by Dr Jagdish Devalia of JD Medical and Scientific Communications Limited which was funded by GlaxoSmithKline (GSK).

Footnotes

GS declares honoraria for lecturing, chairing meetings, and advising ALK, GSK, Merck, Stallergenes and Uriach, all of whom make treatments for rhinitis. She has received research funding from ALK, GSK and Merck. SW is a full-time employee of Asthma UK, and declares financial support from Boehringer Ingelheim for international conference attendance.

References

- Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA). Revised 2002: Global Strategy for Asthma Management and Prevention. http://www.ginasthma.org/

- National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI). Expert Panel Report 2: Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Management of Asthma. Full Report 1997. http://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/guidelines/archives/epr-2/asthgdln_archive.pdf

- British Thoracic Society (BTS). British Guideline on the Management of Asthma. Thorax 2003; 58 Suppl 1. http://www.brit-thoracic.org.uk. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canadian Thoracic Society (CTS). Adult asthma consensus guidelines update 2003. http://www.lung.ca/cts-sct/pdf/Adult_Asthma_Consensus.pdf. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Bateman ED, Hurd SS, Barnes PJ, et al. Global strategy for asthma management and prevention: GINA executive summary. Eur Respir J 2008;31:143–78. http://dx.doi.org/10.1183/09031936.00138707 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calhoun WJ, Sutton LB, Emmett A, Dorinsky PM. Asthma variability in patients previously treated with beta2-agonists alone. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2003;112:1088–94. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jaci.2003.09.044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen S. From asthma severity to control: a shift in clinical practice. Prim Care Respir J 2010;19:3–9. http://dx.doi.org/10.4104/pcrj.2009.00059 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bateman ED, Boushey HA, Bousquet J, et al. GOAL Investigators Group. Can guideline-defined asthma control be achieved? The Gaining Optimal Asthma ControL study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2004;170(8):836–44. http://dx.doi.org/10.1164/rccm.200401-033OC [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bateman ED, Bousquet J, Busse WW, et al. GOAL Steering Committee and Investigators. Stability of asthma control with regular treatment: an analysis of the Gaining Optimal Asthma controL (GOAL) study. Allergy 2008;63(7):932–8. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1398-9995.2008.01724.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Godard P, Greillier P, Pigearias B, Nachbaur G, Desfougeres JL, Attali V. Maintaining asthma control in persistent asthma: comparison of three strategies in a 6-month double-blind randomised study. Respir Med 2008;102(8):1124–31. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.rmed.2008.03.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pauwels RA, Pedersen S, Busse WW, et al. START Investigators Group. Early intervention with budesonide in mild persistent asthma: a randomised, double-blind trial. Lancet 2003;361(9363):1071–6. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(03)12891-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bousquet J, Boulet LP, Peters MJ, et al. Budesonide/formoterol for maintenance and relief in uncontrolled asthma vs.high-dose salmeterol/fluticasone. Respir Med 2007;101(12):2437–46. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.rmed.2007.07.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Busse WW, Shah SR, Somerville L, Parasuraman B, Martin P, Goldman M. Comparison of adjustable- and fixed-dose budesonide/formoterol pressurized metered-dose inhaler and fixed-dose fluticasone propionate/salmeterol dry powder inhaler in asthma patients. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2008;121(6):1407–14. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jaci.2008.03.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor DR, Bateman ED, Boulet LP, et al. A new perspective on concepts of asthma severity and control. Eur Respir J 2008;32:545–54. http://dx.doi.org/10.1183/09031936.00155307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reddel HK, Taylor DR, Bateman ED, et al. American Thoracic Society/ European Respiratory Society Task Force on Asthma Control and Exacerbations. An official American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society statement: asthma control and exacerbations: standardizing endpoints for clinical asthma trials and clinical practice. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2009;180:59–99. http://dx.doi.org/10.1164/rccm.200801-060ST [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy ML. Guideline-defined asthma control: a challenge for primary care. Eur Respir J 2008;31:229–31. http://dx.doi.org/10.1183/09031936.00157507 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horne R, Price D, Cleland J, et al. Can asthma control be improved by understanding the patient's perspective? BMC Pulm Med 2007;7:8. http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1471-2466-7-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corrigan CJ. Asthma therapy: there are guidelines and then there is real life… Prim Care Resp J 2011;20:13–14. http://dx.doi.org/10.4104/pcrj.2011.00016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clatworthy J, Price D, Ryan D, Haughney J, Horne R. The value of self-report assessment of adherence, rhinitis and smoking in relation to asthma control. Prim Care Respir J 2009;18:300–05. http://dx.doi.org/10.4104/pcrj.2009.00037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandão HV, Cruz CS, Pinheiro MC, et al. Risk factors for ER visits due to asthma exacerbations in patients enrolled in a program for the control of asthma and allergic rhinitis in Feira de Santana, Brazil. J Bras Pneumol 2009;35:1168–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magnan A, Meunier JP, Saugnac C, Gasteau J, Neukirch F. Frequency and impact of AR in asthma patients in everyday general medical practice: a French observational cross-sectional study. Allergy 2008;63:292–8. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1398-9995.2007.01584.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angier E, Willington J, Scadding G, Holmes S, Walker S. Management of allergic and non-allergic rhinitis: a primary care summary of the BSACI guideline. Prim Care Resp J 2010;19:217–22. http://dx.doi.org/10.4104/pcrj.2010.00044 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allergic Rhinitis and its Impact on Asthma (ARIA). http://www.whiar.org/Documents&Resources.php

- Bousquet J, Vignola AM, Demoly P. Links between rhinitis and asthma. Allergy 2003;58:691–706. http://dx.doi.org/10.1034/j.1398-9995.2003.00105.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leynaert B, Neukirch C, Kony S, et al. Association between asthma and rhinitis according to atopic sensitization in a population-based study. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2004;113:86–93. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jaci.2003.10.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linneberg A, Henrik Nielsen N, Frolund L, Madsen F, Dirksen A, Jorgensen T. The link between AR and allergic asthma: a prospective population-based study. The Copenhagen Allergy Study. Allergy 2002;57:1048–52. http://dx.doi.Org/10.1034/j.1398-9995.2002.23664.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauchau V, Durham SR. Epidemiological characterization of the intermittent and persistent types of AR. Allergy 2005;60:350–3. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1398-9995.2005.00751.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slavin RG. The upper and lower airways: the epidemiological and pathophysiological connection. Allergy asthma proc 2008;29:553–6. http://dx.doi.org/10.2500/aap.2008.29.3169 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simons FER. Allergic rhinobronchitis: the asthma-AR link. J Allergy Clin Immunol 1999;104:534–40. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0091-6749(99)70320-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braunstahl GJ. The unified immune system: Respiratory tract nasobronchial interaction mechanisms in allergic airway disease. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2005;115:142–8. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jaci.2004.10.041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowe-Jones JM. The link between the nose and the lung, perennial rhinitis and asthma -is it the same disease? Allergy 1997;52(suppl 36):20–8. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1398-9995.1997.tb04818.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durham SR. Mechanisms of mucosal inflammation in the nose and lungs. Clin Exp Allergy 1998;28(Suppl 2):11–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Togias A. Mechanisms of nose-lung interaction. Allergy 1999;54(Suppl 57):94–105. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1398-9995.1999.tb04410.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corren J, Adinoff AD, Irvin CG. Changes in bronchial responsiveness following nasal provocation with allergen. J Allergy Clin Immunol 1992;89:611–18. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0091-6749(92)90329-Z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inal A, Kendirli SG, Yilmaz M, Altintas DU, Karakoc GB, Erdogan S. Indices of lower airway inflammation in children monosensitized to house dust mite after nasal allergen challenge. Allergy 2008;63:1345–51. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1398-9995.2008.01694.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonay M, Neukirch C, Grandsaigne M, et al. Changes in airway inflammation following nasal allergic challenge in patients with seasonal rhinitis. Allergy 2006;61:111–18. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1398-9995.2006.00967.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braunstahl GJ, Overbeek SE, Fokkens WJ, et al. Segmental bronchoprovocation in AR patients affects mast cell and basophil numbers in nasal and bronchial mucosa. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2001;164:858–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braunstahl GJ, KleinJan A, Overbeek SE, Prins JB, Hoogsteden HC, Fokkens WJ. Segmental bronchial provocation induces nasal inflammation in AR patients. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2000;161:2051–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fasano MB. Combined airways: impact of upper airway on lower airway. Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2010;18:15–20. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/MOO.0b013e328334aa0e [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Downie SR, Andersson M, Rimmer J, et al. Association between nasal and bronchial symptoms in subjects with persistent AR. Allergy 2004;59:320–6. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1398-9995.2003.00419.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas M. AR: evidence for impact on asthma. BMC Pulm Med 2006;6 Suppl 1:S4. http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1471-2466-6-S1-S4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taramarcaz P, Gibson PG. Intranasal corticosteroids for asthma control in people with coexisting asthma and rhinitis. Cochrane Database Sys Rev 2003;4:CD003570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baiardini I, Villa E, Rogkakou A, et al. Effects of mometasone furoate on the quality of life: a randomized placebo-controlled trial in persistent allergic rhinitis and intermittent asthma using the Rhinasthma questionnaire. Clin Exp Allergy 2011;41:417–23. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2222.2010.03660.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaaban R, Zureik M, Soussan D, et al. Rhinitis and onset of asthma: a longitudinal population-based study. Lancet 2008;372:1049–57. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61446-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guerra S, Sherrill DL, Martinez FD, Barbee RA. Rhinitis as an independent risk factor for adult-onset asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2002;109:419–25. http://dx.doi.org/10.1067/mai.2002.121701 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leynaert B, Neukirch C, Kony S. Association between asthma and rhinitis according to atopic sensitization in a population-based study. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2004;113:86–93. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jaci.2003.10.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burgess JA, Walters EH, Byrnes GB, et al. Childhood AR predicts asthma incidence and persistence to middle age: a longitudinal study. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2007;120:863–9. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jaci.2007.07.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plaschke PP, Janson C, Norrman E, Björnsson E, Ellbar S, Jan/holm B. Onset and remission of AR and asthma and the relationship with atopic sensitization and smoking. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2000;162:920–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bugiani M, Carosso A, Migliore E, et al. AR and asthma comorbidity in a survey of young adults in Italy. Allergy 2005;60:165–70. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1398-9995.2005.00659.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price D, Zhang Q, Kocevar VS, Yin DD, Thomas M. Effect of a concomitant diagnosis of AR on asthma-related health care use by adults. Clin Exp Allergy 2005;35:282–7. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2222.2005.02182.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crystal-Peters J, Neslusan CA, Smith MW, Togias A. Health care costs of AR-associated conditions vary with allergy season. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 2002;89:457–62. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S1081-1206(10)62081-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braido F, Baiardini I, Balestracci S, et al. Does asthma control correlate with quality of life related to upper and lower airways? A real life study. Allergy 2009;64:937–43. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1398-9995.2008.01932.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lack G. Pediatric AR and comorbid disorders. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2001;108(1 Suppl):S9–15. http://dx.doi.org/10.1067/mai.2001.115562 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sur DK, Scandale S. Treatment of AR. Am Fam Physician 2010;81:1440–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nathan RA. Management of patients with AR and asthma: literature review. South Med J 2009;102:935–41. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/SMJ.0b013e3181b01c68 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scadding GK, Durham SR, Mirakian R, et al. BSACI guidelines for the management of allergic and non-allergic rhinitis. Clin Exp Allergy 2008;38:19–42. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2222.2007.02888.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker S, Sheikh A. Rhinitis — 10-minute consultation. BMJ 2002;324:403.11850373 [Google Scholar]