Abstract

Background:

The importance of identifying chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) at an early stage is recognised. Improved and easily accessible identification of individuals at risk of COPD in primary care is needed to select patients for spirometry more accurately.

Aims:

To explore whether use of a mini-spirometer can predict a diagnosis of COPD in patients at risk of COPD in primary care, and to assess its cost-effectiveness in detecting patients with COPD.

Methods:

Primary care patients aged 45–85 years with a smoking history of ≥15 pack-years were selected. Data were collected on the Clinical COPD Questionnaire (CCQ), Medical Research Council (MRC) dyspnoea scale and smoking habits. Lung function (forced expiratory volume in 1 and 6 s; FEV1 and FEV6, respectively) was measured by mini-spirometer (copd-6), followed by diagnostic standard spirometry (COPD diagnosis post-bronchodilation ratio of FEV1 to forced vital capacity (FVC) <0.7). Time consumed was recorded. Univariate logistic regression and receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves were used.

Results:

A total of 305 patients (57% females) of mean (SD) age 61.2 (8.4) years, mean (SD) total CCQ 1.0 (0.8) and mean (SD) MRC 0.8 (0.8) were recruited from 21 centres. COPD was diagnosed in 77 patients (25.2%) by standard diagnostic spirometry. Using the copd-6 device, mean (SD) FEV1/FEV6 was 68 (8)% in patients with COPD and 78 (10)% in patients without COPD. Sensitivity and specificity at a FEV1/FEV6 cut-off of 73% were 79.2% and 80.3%, respectively. The area under the ROC curve was 0.84. Screening with the copd-6 device significantly predicted COPD. Gender, CCQ, and MRC were not found to predict COPD.

Conclusions:

Using the copd-6 as a pre-screening device, the rate of COPD diagnoses by standard diagnostic spirometry increased from 25.2% to 79.2%. Although the sensitivity and specificity of the copd-6 could be improved, it might be an important device for pre-screening of COPD in primary care and may reduce the number of unnecessary spirometric tests performed.

Keywords: COPD, early diagnosis, spirometry, mini-spirometer, copd-6, cost-effectiveness

Introduction

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is a common condition, the prevalence of which is increasing in developed countries, as is the mortality rate.1 In most countries, primary care clinicians diagnose and treat the majority of patients with chronic respiratory diseases, as exemplified by the UK and the Netherlands where approximately 85% of patients with asthma and COPD are managed almost entirely by general practitioners and primary care nurses.2

In the early stages the disease can be non-symptomatic, although episodes with coughing and sputum production may occur. Other than during the earliest stages of the disease, COPD has a great impact on health care systems and causes increasing costs to society due to absence from work, doctor office visits, medication, and hospital admissions.1 COPD is usually diagnosed in the later stages when significant lung function has already been lost or, in extreme cases, patients are not diagnosed until they are hospitalised for an acute exacerbation.3 The diagnosis of COPD in developing countries is even more difficult as these countries often lack the technical resources and expensive equipment for objective diagnosis. There are many barriers to early diagnosis. One is the delay due to the patient's gradual adaptation to decreasing lung function. Another barrier for early diagnosis of COPD is the ‘doctor's/health care delay’ — for example, poor access to spirometers or limited use of spirometers in primary care.

The presence of spirometers in developed countries is, however, increasing in primary care. For example, in Sweden about 90% of primary health care centres (PHCC) have access to spirometers, but their use is limited.4,5

Although there is increased access to spirometers, it is reported that primary care physicians seldom use spirometry to detect COPD in smokers or individuals with respiratory symptoms.6 Population-based studies from different countries show that COPD is significantly under-diagnosed.7–9 In one study only 25% of smokers with COPD were previously aware of the diagnosis.10 Even among those with severe or very severe airflow obstruction, less than half were diagnosed.11 COPD could easily be detected in its early phase when smoking cessation advice would have the best chance of preventing progression to severe disabling disease.12 More frequent use of spirometry in primary care to improve the diagnosis of COPD has been promoted.13

The main risk factors for COPD are increasing age — which expresses the total lifetime exposure — and smoking.1 In primary care, improved and easily accessible methods of identification of individuals at risk of COPD are needed to identify more accurately patients with a high probability of COPD. Although COPD is easily diagnosed by standard spirometry, at present this is difficult to perform in all smokers at risk of COPD in primary care as the procedure is both personnel- and time-consuming within the normal day-to-day activities.

The aim of this study was to explore, under real-life conditions, whether the use of a mini-spirometer could predict a diagnosis of COPD in patients at risk of COPD in primary health care. An additional aim was to analyse the costs of detecting a patient with COPD.

Methods

Patient selection

Twenty-one urban and rural PHCCs in Sweden participated in the study (clinicaltrials.gov, NCT01013922). To participate in the study the PHCC had to have an asthma/COPD nurse who was responsible for patients with asthma/COPD, including routine spirometry testing. Patients aged 45–85 years who visited their PHCC were consecutively asked at admission to complete a form about smoking habits. Those with a smoking history of at least 15 pack-years were asked to participate in the study. If the patient agreed to participate, an appointment was made with the asthma/COPD nurse for lung function tests to be performed. The recruitment of smokers lasted for 5 months.

Lung function testing

Lung function was measured in all subjects by two separate methods. At the visit to the nurse, the subjects first performed lung function tests with a mini-spirometer (copd-6, Vitalograph, Ireland). Pre-bronchodilation lung function was indicated by forced expiratory volume in 1 and 6 s (FEV1 and FEV6, respectively) and the FEV1/FEV6 ratio; the highest values of the three measurements were recorded.

The subjects then performed a diagnostic standard spirometry: FEV1, forced vital capacity (FVC), vital capacity (VC), and the FEV1/FVC ratio were measured. Standard spirometry was performed with the spirometers used in daily practice in the PHCCs. They were calibrated prior to each lung function test. The spirometric tests had to meet the recommendations of the American Thoracic Society.14

Spirometry was performed in a sitting upright position with the patient wearing a nose clip. Lung function tests consisted of three expiratory manoeuvres during which the patient had to exhale from full inspiration as hard and as fast as possible. The highest values of FEV1 and FVC were recorded. Reversibility was tested by inhalation of 2–3 doses of a short-acting β2-agonist (terbutaline 0.5mg) and FEV1 was measured after 15±5 mins.

Definitions and diagnostic criteria of COPD

The lung function tests performed by standard spirometry were classified according to the guidelines of the Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD).1 The results were classified as COPD if the post-bronchodilation FEV1/FVC ratio was <0.7. COPD was classified as stage I (FEV1 ≥80% of predicted), stage II 50%≤FEV1<80% of predicted), stage III (30%≤FEV1<50% of predicted), and stage IV (FEV1 <30% of predicted value).

Pack-years were defined as the number of years of smoking multiplied by the average number of cigarettes smoked per day divided by 20.

Questionnaires

Airway symptoms and health-related quality of life were evaluated with the Clinical COPD Questionnaire (CCQ)15 and breathlessness was measured with the Medical Research Council (MRC) dyspnoea scale.

Ethics

Informed consent was obtained and the study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the University Hospital Linköping, Sweden.

Statistical analyses

The diagnostic sensitivity and specificity of the copd-6 device was evaluated by comparing the copd-6 results with the values from standard spirometry. The variables measured by the copd-6 device (FEV1/FEV6, FEV1 (in litres and predicted of normal), FEV6 (in litres and predicted of normal)) with the highest area under the receiver operating characteristics (ROC) curve were selected and investigated further to find the best cut-off value.

Cost calculations

The time to perform copd-6 measurements and diagnostic standard spirometry was measured at three centres of different sizes (total of 24 patients). For full-time employment, assumptions of 220 working days per year and 8 working hours per day were made. The procedures were assumed to be performed by a nurse. Costs were calculated from a health care provider perspective by multiplying the average time per procedure by the average national full-time district nurse wage (SEK28,100/month in 2009)16 plus social benefit payments (41.93% in 2009).17 The incremental cost of detecting a COPD patient was derived by comparing the most effective strategy in terms of number of COPD cases detected with the next most effective detection strategy. The addition of pre-selection criteria for diagnostic standard spirometry, such as copd-6 measurement, increases the risk of false negatives. Thus, given the increasing risk of false negatives, adding pre-selection criteria will decrease the effectiveness compared with a strategy without pre-selection criteria. While by definition more effective, we do not know whether a strategy without any pre-selection criteria is cost-effective relative to a strategy involving pre-selection criteria. We therefore assessed the cost-effectiveness by calculating the incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) as defined below:

where N = the total number of patients, Npositives = the number of patients who met the copd-6 criteria for spirometry (true positives + false positives), Cspirometry = cost per spirometry, Ccopd-6 = cost per copd-6 measurement, Effect = number of COPD cases detected.

The copd-6 devices and spirometers were assumed to be available. Acquisition costs were not included in the analysis. An exchange rate of 1SEK = €0.109 was used.18

Results

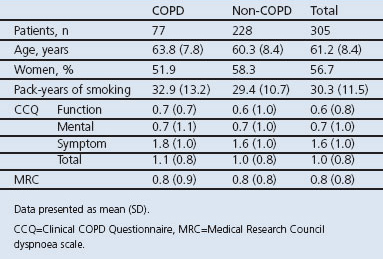

In all, 305 patients from 21 Swedish primary care centres were included. The baseline characteristics of the included subjects are presented in Table 1. There were no significant differences between COPD and non-COPD patients regarding age, gender, pack years, CCQ, and MRC.

Table 1. Patient baseline characteristics (classification according to the Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease1).

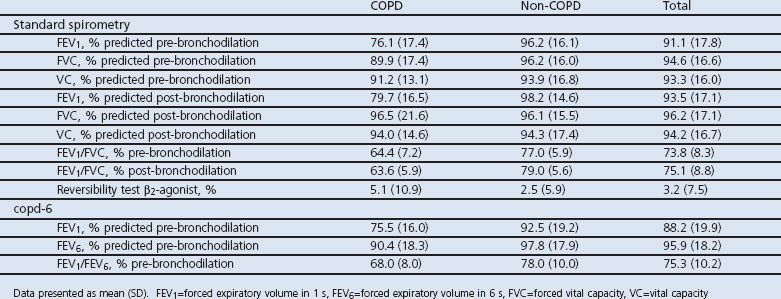

Lung function measurements are shown in Table 2. COPD was diagnosed in 77 patients (25.2%) by standard diagnostic spirometry, 35 out of 77 (45.5%) with stage I (mild disease), 41 (53.2%) with stage II (moderate disease), and one patient (1.3%) with stage III (severe disease). None were in stage IV.

Table 2. Lung function values by standard spirometry and with the copd-6 device (classification according to the Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease1).

The FEV1/FVC ratio by standard spirometry and the FEV1/FEV6 ratio by the copd-6 device gave similar results in all subjects (Table 2). Similar findings were found for FEV1 performed by standard spirometry (pre-bronchodilation) and the copd-6 device and FVC compared with FEV6 among the studied subjects.

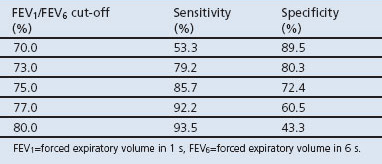

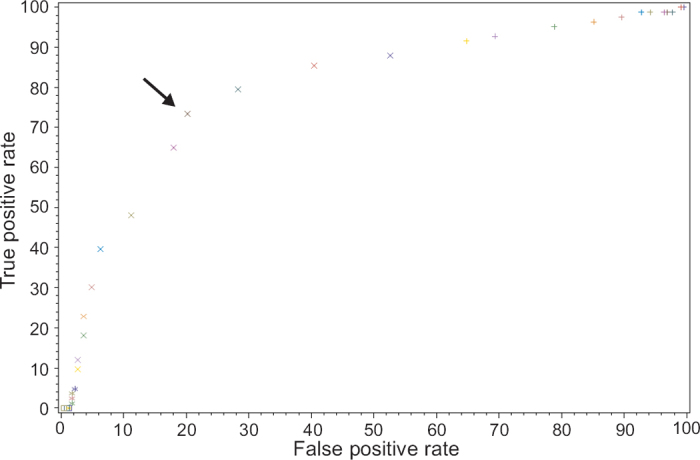

The FEV1/FEV6 cut-off ratio affects the sensitivity and specificity of assessing COPD diagnosis (Table 3). At an FEV1/FEV6 cut-off of 73%, the highest sensitivity with an acceptable specificity was found according to the ROC curve, with the copd-6 device having a sensitivity of 79.2% and a specificity of 80.3% (Figure 1, Table 3). Using the FEV1 (instead of the FEV1/FEV6 ratio), at a cut-off of 80% of the predicted value the sensitivity of the copd-6 was only 62.0% and the specificity was 82.0%, with an area under the ROC curve of 0.74.

Table 3. Sensitivity and specificity at different cut-off FEV1/FEV6 ratios.

Figure 1. Receiver operating characteristics (ROC) curve for the forced expiratory volume in 1 s/forced expiratory volume in 6 s (FEV1/FEV6) ratio with the copd-6 device. The arrow indicates the selected FEV1/FEV6 ratio cut-off of 73%. Area under the curve=0.84.

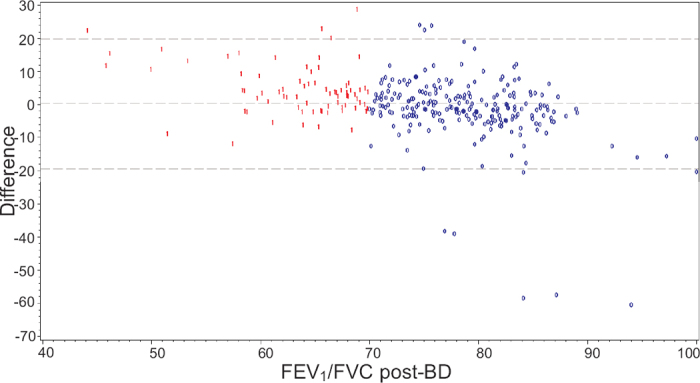

The difference between the FEV1/FEV6 ratio pre-bronchodilation and the FEV1/FVC ratio post-bronchodilation is shown in Figure 2. It should be noted that the mean difference was very small (0.23), showing that the level of measurements overall is the same by the two methods. If the patients are divided into COPD and non-COPD patients, the difference was higher for COPD patients (4.80) and lower for non-COPD patients (−1.32), indicating that patients with COPD have higher values. This was compensated for by changing the suggested cut-off for the copd-6 measurement from 0.70 to 0.73. Some of the difference was also caused by five patients having very low values with the copd-6 device.

Figure 2. Difference between the forced expiratory volume in 1 s/forced expiratory volume in 6 s (FEV1/FEV6) ratio pre-bronchodilation with the copd-6 device and the forced expiratory volume in 1 s/forced vital capacity (FEV1/FVC) ratio post-bronchodilation (post-BD) by standard spirometry. Blue ‘0’ = no COPD, Red ‘1’ = COPD.

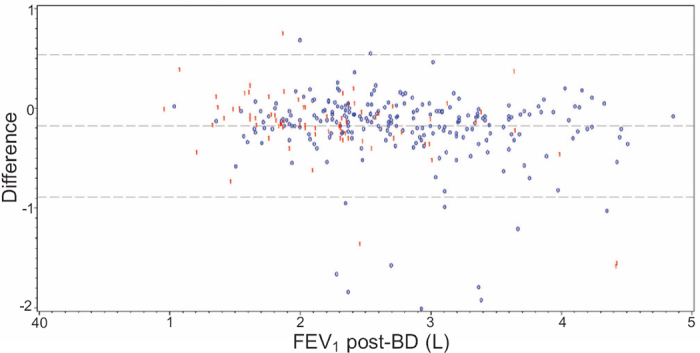

The difference between FEV1 with the copd-6 device pre-bronchodilation and FEV1 by standard spirometry post-bronchodilation is shown in Figure 3. FEV1 measured by the copd-6 device was lower than post-bronchodilation FEV1 measurements by ordinary spirometry. The mean value was 0.18L lower. There was no trend to indicate that a person with low or high FEV1 values systematically had measurements that were too low or too high with the copd-6 device.

Figure 3. Difference between forced expiratory volume in 1 s (FEV1) with the copd-6 device) pre-bronchodilation and FEV1 by standard spirometry post-bronchodilation (post-BD). Blue ‘0’ = no COPD, Red ‘1’ = COPD.

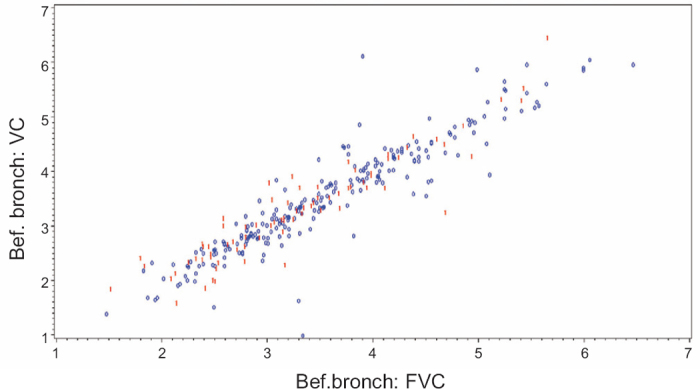

In Figure 4, slow VC is compared with FVC measurements pre-bronchodilation by standard spirometry. A linear correlation between the VC and FVC measurements was found.

Figure 4. Comparison of slow vital capacity (VC) with forced vital capacity (FVC) measurements pre-bronchodilation by standard spirometry. Blue ‘0’ = no COPD, Red ‘1’ = COPD.

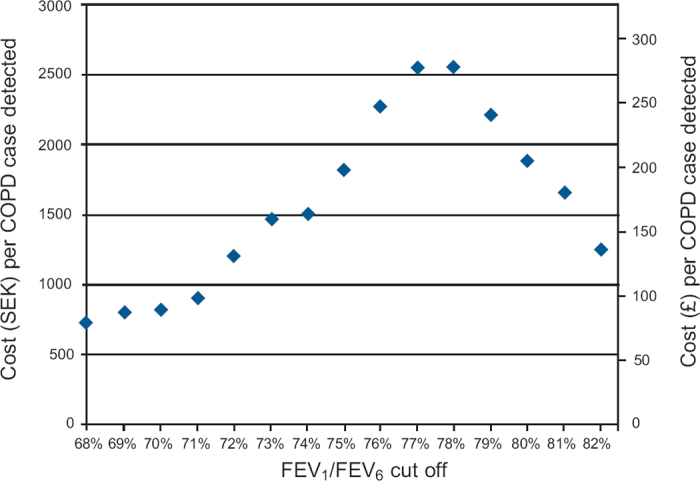

The average time for copd-6 measurement and standard diagnostic spirometry was 4:17mins and 32:31mins, respectively. This resulted in cost estimations of SEK19.41 (€2.12) per copd-6 measurement and SEK147.37 (€16.07) per standard spirometry measurement. ICERs reflecting the cost per additional COPD case detected by screening without copd-6 versus screening with copd-6 at different FEV1/FEV6 cut-off ratios are shown in Figure 5. The maximum ICER (SEK2559 = €279) per additional COPD case detected by ordinary health care routines (i.e. without copd-6) was found at a copd-6 FEV1/FEV6 cut-off of 78%.

Figure 5. Incremental cost-effectiveness ratios (ICERs) of COPD screening without copd-6 versus screening with copd-6 at different cut-off forced expiratory volume in 1 s/forced expiratory volume in 6 s (FEV1/FEV6) ratios.

Discussion

Main findings

Previous studies suggest that early detection of COPD and intervention for smoking cessation can delay lung function decline, reduce the burden of COPD symptoms, and improve patients' quality of life.19–22

Our results suggest that, by using a mini-spirometer (copd-6) as a pre-screening device in a primary care population at risk of COPD to select patients for standard spirometry, the resulting frequency of detected COPD diagnoses by standard spirometry (number of positive COPD diagnoses divided by total number of spirometries performed) increased from 25.2% to 79.2% when the cut-off value for FEV1/FEV6 was 73%.

When using a diagnostic tool, the establishment of a suitable cut-off value is vital to achieve a useful sensitivity at an acceptable specificity. Diagnostic criteria for COPD set by GOLD are based on the finding of a post-bronchodilator FEV1/FVC ratio of <0.7 with standard diagnostic spirometry.1 This cut-off is used for purposes of simplicity. It has been acknowledged that reduction in lung function due to ageing may affect the diagnostic accuracy of these measures in older patients, with a risk of over-diagnosis in the elderly population. On the other hand, the same fixed ratio can result in under-diagnosis of COPD in a younger population.23,24 An FEV1/FEV6 cut-off ratio of 70% with the copd-6 would have a higher specificity than our proposed cut-off ratio of 73% but would, however, have a much lower sensitivity (Table 3).

The results of this study suggest that an FEV1/FEV6 ratio of 73% is the cut-off value of choice for use of copd-6 in a primary care population at risk of developing COPD. On the other hand, the balance of false negative versus false positive COPD diagnoses by copd-6 needs to be taken into account, and awareness of the clinical implications needs to be stressed. The area under the ROC curve was 0.84 for copd-6, which might be considered somewhat low for a useful diagnostic device. However, the frequency of detected COPD diagnoses improved by using the copd-6 as a pre-screening device (Figure 1).

A sensitivity of 79.2% was achieved with the mini-spirometer using an FEV1/FEV6 cut-off of 73%, which means that 20.8% of patients with COPD were not diagnosed. Is this acceptable? This must of course be related to current recommendations and practices. Using copd-6 as a pre-screening device, false positive cases judged as having COPD with the mini-spirometer will correctly be excluded after performing standard diagnostic spirometry. The missed cases of COPD with the mini-spirometer may be due to the built-in weakness of the method. Instead of measuring the whole FVC, the mini-spirometer stops measuring after 6 s with the risk of a falsely high FEV1/FEV6 ratio. Another cause for missed COPD cases could be the fact that the definition of COPD with diagnostic standard spirometry uses the post-bronchodilation values.

For case identification, it is acceptable to perform a less specific but relatively sensitive test. The International Primary Care Respiratory Group (IPCRG) proposes a FEV1/FEV6 of ≤0.8 (80%).25,26 In our study this FEV1/FEV6 cut-off would give a higher sensitivity (93.5%) but a very low specificity (43.4%) (Table 3). Furthermore, our results suggest that a cut-off of 73% seems to be a good compromise with a high sensitivity and an acceptable specificity.

Traditionally, measurement of the degree of reversibility using bronchodilators has been used to try to separate patients with asthma from those with COPD. There are many difficulties with this approach. The guidelines state that increases of 15% in FEV1 after inhalation of short-acting (β2-agonists can be seen in asthma, but these guidelines do not deal specifically with the differentiation of asthma from COPD. This makes it virtually impossible to interpret the response to an individual reversibility test unless the response is very large (e.g. an increase in FEV1 of >400mL) according to the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) guidelines.27 In this study eight patients without COPD and four with COPD had reversibility of >400mL, suggesting possible asthma.

In order to assess the cost-effectiveness of using the copd-6 as a pre-screening tool for spirometry, the health care provider's willingness to pay (WTP) for detecting a case of COPD should be judged against the ICER. In simplified terms, a strategy is considered cost-effective when the WTP exceeds the ICER. At an FEV1/FEV6 cut-off of 78%, the highest WTP (>SEK2559 = €279) is required for a strategy without copd-6 pre-screening (ordinary health care routines) to be considered cost-effective. If the WTP does not exceed the ICER, pre-screening with copd-6 is the cost-effective option. Thus, the use of copd-6 can also be considered cost-effective at a 73% cut-off if the WTP does not exceed SEK1463 = €160. The cost calculations are conservative as only labour costs were considered. A more comprehensive cost analysis (including equipment acquisition costs, fixed costs, etc) would probably increase the cost-effectiveness of the copd-6 pre-screening strategy. The cost calculations do not reflect potential real-life differences in the number of patients who are actually referred to spirometry because of the disparity in the proportion of spirometric tests detecting COPD following pre-screening with copd-6 compared with no pre-screening. It could be that the copd-6 device drives more patients – selected with better precision – to spirometry. If this reasoning holds true, the cost-effectiveness of copd-6 would probably be further enhanced and suggests that an easy and practicable pre-screening approach should be undertaken.

The GOLD guidelines recommend that all smokers aged ≥40 years should undergo spirometry.1 Some guidelines recommend case-finding spirometry in smokers aged ≥35 years.28 In reality, it is not possible to perform spirometric tests in a PHCC (at least not in Sweden) in all smokers aged 35–40 years and older as the procedure is both personnel- and time-consuming. In some countries PHCCs may not incur the cost of the spirometry equipment because of the high cost, and in other countries the spirometer is not used because standard diagnostic spirometry is too time-consuming or the personnel may lack time and motivation.10,29–31 Thus, improved and easily accessible identification of individuals at risk of COPD is needed in primary care to identify more accurately patients with a high probability of COPD in whom spirometry should be performed.

Implications for future research, policy and practice

This paper deals with real-life validation of a mini-spirometer to determine whether spirometric values with the copd-6 device may indicate if a patient at risk of COPD is likely to have a diagnosis of COPD. The results suggest that a mini-spirometer can be used as a pre-screening device for identification of individuals at risk of COPD. One ethical consideration was the fact that approximately 20% of patients were initially suspected to have COPD which could not, however, be confirmed by standard diagnostic spirometry. Another ethical dilemma is that some smokers who actually have COPD are missed by pre-screening with copd-6 at a cut-off level of 73%. These smokers should be advised that the method is not 100% reliable in excluding COPD. Their smoking habits should be discussed and smoking cessation advice given, and they should be offered another pre-screening spirometry test within a year.

Regardless of the presence or absence of airflow obstruction, all current smokers should receive smoking cessation advice. This approach was used in this study. Smoking cessation advice was given to all confirmed COPD patients as well as those who, after completing standard diagnostic spirometry, were found to have normal lung function. Studies have shown that smokers do not perceive the information of normal lung function as a ‘carte blanche’ to smoke more.20

Screening for COPD, even in populations at higher risk, is not recommended in the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) guidelines, largely because of concerns about the cost/benefits in screening for COPD using standard diagnostic spirometry (time and effort required by both patients and the health care system).32 However, this has to be balanced against the costs of treating patients with more severe COPD, since the key drivers among the direct costs are the costs of drugs and hospitalisations.1,33,34

The aim of mini-spirometry performed for case identification purposes is to facilitate early diagnosis of COPD before significant lung function has been lost and airflow limitation is so large that patients seek medical attention for that reason (i.e. fully developed dyspnoea).

Interpretation of findings in relation to previously published work

The results of this study are similar to those of two recently published studies where a mini-spirometer (PiKo-6® flow meter) was used as a screening tool for COPD.35,36 These studies were also multicentre studies and included patients without COPD. The purpose of these studies was to validate the mini-spirometer and to determine whether the use of a mini-spirometer could predict a COPD diagnosis alone or in combination with a COPD questionnaire. The mini-spirometers were compared with a standard spirometer. When using a cut-off level for FEV1/FEV6 of 0.7 in smokers, Sichletidis et al.35 reported a sensitivity of 80% and specificity of 94%. With a cut-off level for FEV1/FEV6 of 0.75 in smokers, Frith et al.36 achieved a sensitivity of 81% and specificity of 71%, and the area under the ROC curve was 0.85. Together, these studies suggest that a mini-spirometer could be a simple and reliable screening tool for COPD. However, longitudinal studies are needed to determine and compare the cost of a severe COPD exacerbation (including hospitalisation) which was avoided by early case-finding.

Conclusions

In conclusion, the frequency of detected COPD diagnoses was 25.2% by standard diagnostic spirometry in this selected primary care population, which increased to 79.2% with the use of the copd-6 as a pre-screening device. Although the sensitivity and specificity of the copd-6 could be improved, it might be an important device for pre-screening of COPD in primary care and may reduce the number of unnecessary spirometric tests performed.

Previously presented at the European Respiratory Society (ERS) Annual Congress 2010 and at the International Society for Pharmacoeconomics and Outcomes Research (ISPOR) Annual European Congress 2010.

Acknowledgments

Handling editor Anthony D'Urzo

Statistical review Gopal Netuveli

Funding The study was sponsored by AstraZeneca.

The study is sponsored by AstraZeneca. We would like to thank the asthma/COPD nurses who performed the pulmonary function tests.

Footnotes

JT received speaking fees from AstraZeneca. BT received speaking fees from AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Pfizer, and GlaxoSmithKline. KL received speaking fees from AstraZeneca, Merck Sharp & Dohme, and Boehringer Ingelheim. LJ, AS, and GS are full-time employees of AstraZeneca.

References

- Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease. Global strategy for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. 2009.

- van Schayck CP, Levy ML, Stephenson P, Sheikh A. The IPCRG guidelines: developing guidelines for managing chronic respiratory diseases in primary care. Prim Care Respir J 2006;15(1):1–4. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.pcrj.2005.12.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calverley PM. COPD: early detection and intervention. Chest 2000;117(5 Suppl 2):365–71S. http://dx.doi.org/10.1378/chest.117.5_suppl_2.365S [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lisspers K, Ställberg B, Hasselgren M, Johansson G, Svärdsudd K. Organisation of asthma care in primary health care in Mid-Sweden. Prim Care Respir J 2005;14(3):147–53. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.pcrj.2005.03.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thorn J, Norrhall M, Larsson R, et al. Management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) in primary care: a questionnaire survey in western Sweden. Prim Care Respir J 2008;17(1):26–31. http://dx.doi.org/10.3132/pcrj.2008.00008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- den Otter JJ, van Dijk B, van Schayck CP, Molema J, van Weel C. How to avoid underdiagnosed asthma/chronic obstructive pulmonary disease? J Asthma 1998;35(4):381–7. http://dx.doi.org/10.3109/02770909809075672 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nihlen U, Montnemery P, Lindholm LH, Lofdahl CG. Detection of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) in primary health care: role of spirometry and respiratory symptoms. Scand J Prim Health Care 1999;17(4):232–7. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/028134399750002467 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindberg A, Bjerg A, Ronmark E, Larsson LG, Lundback B. Prevalence and underdiagnosis of COPD by disease severity and the attributable fraction of smoking. Report from the Obstructive Lung Disease in Northern Sweden Studies. Respir Med 2006;100(2):264–72. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.rmed.2005.04.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tinkelman DG, Price D, Nordyke RJ, Halbert RJ. COPD screening efforts in primary care: what is the yield? Prim Care Respir J 2007;16(1):41–8. http://dx.doi.org/10.3132/pcrj.2007.00009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miravitlles M, Soriano JB, Garcia-Rio F, et al. Prevalence of COPD in Spain: impact of undiagnosed COPD on quality of life and daily life activities. Thorax 2009;64(10):863–8. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/thx.2009.115725 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shahab L, Jarvis MJ, Britton J, West R. Prevalence, diagnosis and relation to tobacco dependence of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in a nationally representative population sample. Thorax 2006;61(12):1043–7. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/thx.2006.064410 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anthonisen NR, Connett JE, Murray RP. Smoking and lung function of Lung Health Study participants after 11 years. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2002;166(5):675–9. http://dx.doi.org/10.1164/rccm.2112096 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sauro A, Scalzitti F, Buono N, et al. Spirometry is really useful and feasible in the GP's daily practice but guidelines alone are not. Eur J Gen Pract 2005;11(1):29–31. http://dx.doi.org/10.3109/13814780509178015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Thoracic Society. Standardization of Spirometry, 1994 Update. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1995;152(3):1107–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Molen T, Willemse BW, Schokker S, ten Hacken NH, Postma DS, Juniper EF. Development, validity and responsiveness of the Clinical COPD Questionnaire. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2003;1:13. http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1477-7525-1-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Statistics Sweden. May 2010. Available at: www.scb.se (accessed 9 June 2010).

- Swedish Association of Local Authorities and Regions. December 2009. Available at: www.skl.se (accessed 9 June 2010).

- XE. Available at: www.xe.com (accessed 26 September 2010).

- Stratelis G, Jakobsson P, Molstad S, Zetterstrom O. Early detection of COPD in primary care: screening by invitation of smokers aged 40 to 55 years. Br J Gen Pract 2004;54(500):201–06. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stratelis G, Molstad S, Jakobsson P, Zetterstrom O. The impact of repeated spirometry and smoking cessation advice on smokers with mild COPD. Scand J Prim Health Care 2006;24(3):133–9. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/02813430600819751 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scanlon PD, Connett JE, Waller LA, Altose MD, Bailey WC, Buist AS. Smoking cessation and lung function in mild-to-moderate chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. The Lung Health Study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2000;161(2 Pt 1):381–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anthonisen N. Effects of smoking intervention and the use of an inhaled anticholinergic bronchodilator on the rate of decline of FEV1. The Lung Health Study. JAMA 1994;272:1497–505. http://dx.doi.org/10.1001/jama.272.19.1497 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardie JA, Buist AS, Vollmer WM, Ellingsen I, Bakke PS, Morkve O. Risk of overdiagnosis of COPD in asymptomatic elderly never-smokers. Eur Respir J 2002;20(5):1117–22. http://dx.doi.org/10.1183/09031936.02.00023202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johannessen A, Lehmann S, Omenaas ER, Eide GE, Bakke PS, Gulsvik A. Post-bronchodilator spirometry reference values in adults and implications for disease management. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2006;173(12):1316–25. http://dx.doi.org/10.1164/rccm.200601-023OC [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price D, Crockett A, Arne M, et al. Spirometry in primary care case-identification, diagnosis and management of COPD. Prim Care Respir J 2009;18(3):216–23. http://dx.doi.org/10.4104/pcrj.2009.00055 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price D. Earlier diagnosis and earlier treatment of COPD in primary care. Prim Care Respir J 2010;20(1):15–22. http://dx.doi.org/10.4104/pcrj.2010.00060 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE). Available at: http://www.nice.org.uk.

- Levy ML, Fletcher M, Price DB, Hausen T, Halbert RJ, Yawn BP. International Primary Care Respiratory Group (IPCRG) guidelines: diagnosis of respiratory diseases in primary care. Prim Care Respir J 2006;15(1):20–34. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.pcrj.2005.10.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derom E, van Weel C, Liistro G, et al. Primary care spirometry. Eur Respir J 2008;31(1):197–203. http://dx.doi.org/10.1183/09031936.00066607 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lusuardi M, De Benedetto F, Paggiaro P, et al. A randomized controlled trial on office spirometry in asthma and COPD in standard general practice: data from spirometry in asthma and COPD: a comparative evaluation Italian study. Chest 2006;129(4):844–52. http://dx.doi.org/10.1378/chest.129.4.844 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yawn BP, Wollan PC. Knowledge and attitudes of family physicians coming to COPD continuing medical education. Int J COPD 2008;3(2):311–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- US Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease using spirometry: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med 2008;148:529–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jansson SA, Andersson F, Borg S, Ericsson A, Jonsson E, Lundback B. Costs of COPD in Sweden according to disease severity. Chest 2002;122(6):1994–2002. http://dx.doi.org/10.1378/chest.122.6.1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mannino DM, Buist AS. Global burden of COPD: risk factors, prevalence, and future trends. Lancet 2007;370(9589):765–73. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61380-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sichletidis L, Spyratos D, Papaioannou M, et al. A combination of the IPAG questionnaire and PiKo-6® flow meter is a valuable screening tool for COPD in the primary care setting. Prim Care Respir J 2011;20:184–9. http://dx.doi.org/10.4104/pcrj.2011.00038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frith P, Crockett A, Beilby J, et al. Simplified COPD screening: validation of the PiKo-6® in primary care. Prim Care Respir J 2011;20:190–8. http://dx.doi.org/10.4104/pcrj.2011.00040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]