Abstract

Advocates bring unique and important viewpoints to the cancer research process, ensuring that scientific and medical advances are patient-centered and relevant. In this article, we discuss the benefits of engaging advocates in cancer research and underscore ways in which both the scientific and patient communities can facilitate this mutually beneficial collaboration. We discuss how to establish and nurture successful scientist–advocate relationships throughout the research process. We review opportunities that are available to advocates who want to obtain training in the evaluation of cancer research. We also suggest practical solutions that can strengthen communication between scientists and advocates, such as introducing scientist–advocate interactions at the trainee level. Finally, we highlight the essential role social media can play in disseminating patient-supported cancer research findings to the patient community and in raising awareness of the importance of promoting cancer research. Our perspective offers a model that Georgetown Breast Cancer Advocates have found effective and which could be one option for those interested in developing productive, successful, and sustainable collaborations between advocates and scientists in cancer research.

Introduction

Advocates are people who have had close personal experiences with cancer. These experiences include living with cancer, surviving cancer, and caring for someone with cancer. Due to their familiarity with cancer, advocates want to use their experience to help others facing the disease. Advocates play a crucial role by providing a collective patient perspective in the design and execution of research goals (1). They are strong proponents of scientific progress and are committed to expanding and spreading their knowledge in the community (2). Advocate participation is key to ensuring that patient needs and concerns are considered when cancer research is designed and implemented. In this article, based on our own experiences in cancer research advocacy, we outline why involving advocates in research—both basic (preclinical) and clinical—is important and how they can work alongside scientists at a research institution. We also describe critical needs for sustaining an active and engaged advocacy committee.

Why Is It Important to Include Advocates in Cancer Research?

Fosters a sense of urgency and purpose

There was a time when it was unheard of for advocates to be part of scientific discussions and decisions. Fortunately, that has changed dramatically over the past several years and advocates are now increasingly considered to be an integral partner in the cancer research process. Advocates participate by providing patient viewpoints during the planning and execution phases of research. When designing clinical trials or research projects, input from advocates can be both meaningful and practical. Meaningful because they represent the people whose lives are at stake, humanizing a process and injecting into it a sense of urgency. Practical because they represent the people who will have to follow through with the requirements of a trial and so are able to assess the feasibility of such requirements. Advocates’ unique perspectives are based on their own experiences and the insights gained through their networks. They are also affected by interactions with other advocates and patients and the knowledge gained through training at workshops, participating at scientific meetings, or serving on review panels. Scientists, particularly those in basic research, rarely get an opportunity to interact with advocates. Most of their time is spent in the laboratory, working with models of cancer or rodents or applying for grants. Although most scientists do not have the chance to interact with advocates in their professional lives, many would appreciate the opportunity to engage with advocates, as it helps to humanize their scientific efforts and gives additional meaning to all the hours they put in behind the bench.

Improves design of and accrual and retention to clinical trials

Although clinical trials are vital to developing new therapies in cancer, accrual rates are remarkably low with <5% of adults with cancer participating in clinical trials (3). Many patients are not even aware of open trials for which they may be eligible and from which they may benefit. Clearly, we need to narrow this awareness gap to improve trial accrual. By helping to design better clinical trials, advocates play a role in increasing enrollment, potentially helping more patients. Advocates offer guidance on how to accrue and retain patients by considering multiple factors that influence differential participation including age, ethnicity, medical comorbidities, or socio-economic barriers (4, 5). They also contribute to the development of research grant proposals, implementation of protocols, and dissemination of research discoveries (6).

Advocate involvement at the beginning of the process brings the collective patient perspective into research design and implementation (7) while also serving as a reminder of the need for patient-friendly protocols and outcomes that address both survival and quality of life (8). Another important role that advocates play is in translating scientific research into terms that are understandable to laypersons (9). Advocates trained in research design who understand basic scientific principles can bridge the gap between researchers and the public. Advocates provide assistance with participant recruitment and retention (10). Once research findings are published, advocates disseminate lay language summaries of these findings to patient and advocate networks and to the public through communication vehicles such as social media. By emphasizing the importance of being transparent about what is expected of patients, advocates help to demystify the objectives of clinical trials and improve patient enrollment.

Enhances focus of research goals

Patients and their families are the major stakeholders in society’s investment in cancer research. To put this into perspective, it is expected that 1,735,350 new cancer cases will be diagnosed in the United States, and 609,640 cancer deaths will occur in 2018 (11). Advocates play a vital role in raising awareness among groups that make health and funding decisions (12). By communicating with advocates, scientists are tapping representatives of patients who are in constant touch with other patients through private, patient-only networks. Input from advocates encourages physician scientists to consider the impact the research could have on the targeted population (13). Advocates also benefit from further communication with scientists allowing them to better understand the scientists’ perspective and giving them a higher level of trust and respect for the research community. With a strong partnership and shared drive, advocates share and amplify research findings and scientific information to patients and the public, bringing awareness to the importance of science.

Conforms to growing requests by funding agencies

Scientists are increasingly seeking patient perspectives on their projects (14, 15). Funding agencies in the United States, such as the Department of Defense, Patient Centered Outcomes Research Institute, and Susan G. Komen, either require or recommend patient involvement in grants and also include advocates as reviewers on grant application panels. The U.S. NCI Physical Sciences-Oncology Centers, an interdisciplinary hub of scientists at the frontiers of cancer research, have recognized the importance of advocacy support in advancing their cause and promoting data transparency, reproducibility, and sharing (16). The presence of advocates on review panels adds an important perspective without increasing the time spent in deliberation (17). There is evidence that including advocates as research team members on grants improves the likelihood of attracting funding (18). Advocates use their understanding of cancer and their unique perspective on it by promoting cancer-related policies at the community and state levels (19, 20) and by sitting on Institutional Review Boards. Advocates also influence policy by participating in clinical guideline panels for professional oncology societies and organizations through drug review panels (21), and also by contributing to the recommendations of National Blue Ribbon panels through the Cancer Moonshot Initiative (22).

How Can You Involve Advocates in Cancer Research?

The following sections address how Georgetown Breast Cancer Advocates have developed and sustained an advocacy committee to work with the cancer center’s researchers:

Identify the need

As the urgency to find better medical treatments grows, momentum is building toward recognizing the value of advocacy in promoting scientific advances (16). Leaders at cancer institutions universally value homegrown bench-to-bedside projects that translate scientific findings into the clinic. Thus, recognizing a common cause between the institution’s goals and the patient can logically lead to the establishment of an advocacy committee to collectively facilitate faster clinical advances. By providing appropriate support, resources, and feedback, the institution will help ensure the success of the committee and the achievement of its objectives.

Assemble a diverse and dynamic group

The first step toward a sustainable volunteer advocacy committee is the selection of a committed member of the institution (e.g., a faculty member or staff) to be the scientific advisor who functions as the informed intermediary between the institution and the advocates. The scientific advisor’s leadership will ensure significant attention is given toward providing basic science and cancer biology education for advocates. Clinicians or the staff from the institutional office of development are valuable sources for finding prospective advocates because these individuals routinely interact with patients from the community, caregivers, or individuals working in a related field. We have found an ideal size for our advocacy committee consisting of 12 to 15 advocates, a number that is manageable but offers the flexibility for members’ schedules and commitments. To embrace varying perspectives and approaches, members should represent a wide range in terms of age, education, race, subtypes of cancer diagnosis if possible, professions, and socio-economic status. Having a broad base allows the committee to leverage the members’ expertise in order to meet the committee’s mission. Generally, patients and survivors who are interested or already involved in some form of outreach activity in the community are considered ideal candidates. As the committee evolves over time, it becomes clear when additional persons are needed to strengthen its diversity. The ultimate goal should be that the committee be reflective of the community served by the group. An advocacy committee should attempt to include people representing a wide range of ages, races, and different diagnoses.

Develop a collective mission

The objective behind assembling an advocacy committee in a cancer research organization should be to integrate the collective patient perspective with the institution’s own goals in specific areas of cancer research. With this understanding, the mission of the advocacy committee must be crafted through an interactive process with its members. Georgetown Breast Cancer Advocates created our own mission statement, taking into account the various stakeholders within the institution including patients, advocates, scientists, and doctors. Our mission promotes research that is patient-centered, innovative, evidence based, and accessible.

Build a strong foundation

The education, experience, and depth of the advocates’ knowledge coupled with outside organizational involvement fosters enhanced credibility at the sponsoring institution where they can be viewed as a valuable resource. Learning the structure and process of developing scientific research grants, protocols, and proposals prepares advocates to provide critical feedback to researchers on their applications prior to submission. Educating advocates on the full grant review process, funding cycles, and importance of the advocate’s voice ensures that they are adept at serving on grant review panels both at the institutional and national levels. In addition, inviting guest speakers from all realms of cancer research, as well as representatives from the pharmaceutical industry and federal funding agencies, provides a variety of perspectives to add to the advocates’ knowledge base.

Establish roles, rules, and responsibilities

From inception, members must understand that they are joining an active working committee and that they must be committed to learning the science necessary to be an effective advocate. Roles and responsibilities of members should be formulated in written guidelines that the members must agree to follow in order to become or remain a member. Some items to consider when formulating the guidelines that define the roles and responsibilities of the members are as follows:

Members must function as an active and engaged part of the committee

They must regularly attend meetings and become familiar with the process of cancer research and educated in the science of cancer. They should share knowledge and expertise and suggest educational and networking opportunities with the committee. Most importantly, members serve as reviewers and advisors for cancer research projects presented to the committee.

Members must recognize the committee is about the mission, not the individual

To accomplish this, they should refrain from promoting a specific area of research as being more important than another and demonstrate professional and respectful conduct at all times, especially when communicating differences of opinion with researchers and other members. They must recognize that researchers have the right to accept or disregard their feedback. Further, they must refrain from soliciting business referrals for personal gain and avoid conflicts of interest. With regard to conflicts of interest, members may be requested to provide the committee with a list of their outside involvements to ensure no financial or other conflict of interest arises. Most importantly, members must maintain confidentiality when research proposals are presented to the committee, and the institution should provide a confidentiality agreement for each member to sign.

The committee needs operational guidelines

The committee must develop guidelines regarding policies such as the frequency of meetings (typically monthly) and the recruitment of new members. Guidelines should be established for orienting new members, including a mentoring process to help integrate new members into the existing committee. When members fail to adhere to the rules of the committee, guidelines should detail how to identify it, provide the member with an opportunity to correct the behavior, and when to request a member to resign. In formulating these guidelines, the objective is to have an evolving, cohesive, productive group capable of achieving its goals.

Nurture bidirectional communication

Scientists and advocates each bring distinctive skill sets, educational backgrounds, and training to the cancer research process. It is important that both groups treat each other with mutual respect. The scientist–advocate communication process works best when the dialogue begins early rather than right before a grant application deadline. It is critical for scientists to share their lay abstracts and ensure that the advocates understand their aims and expectations. When advocates have a good understanding of the proposed research, they are able to provide the collective patient perspective. Advocates support scientists throughout the research project and help strengthen community outreach and partnerships (16, 23). For their contributions, advocates maybe included in the researcher’s budget, as a member of the team (i.e., stipend for consulting services), and for travel to educational meetings or workshops along with the scientists. In addition, scientists should be encouraged to acknowledge advocates in their publications, presentations, and posters to highlight their collaborations. Successful advocate groups maintain regular contact with scientists by inviting them to present research, share concepts, and provide scientific training. In addition, advocates can interact with students and trainees in research, which can provide them with insight to new perspectives and inspiration for their future work (23). Regular contact outside of the grant writing process helps to foster a sense of community and mutual respect beyond research.

Promote ongoing learning and development

A successful advocacy committee requires a commitment to ongoing education and learning among the members. Although the scientific advisor serves as an educational resource for the committee, consistent involvement with professional societies and advocacy-based organizations is equally important. It is crucial that members become involved in opportunities that further their knowledge, skills, and experience in the fields of advocacy and oncology. As such, members should attend meetings (including departmental or program meetings within the institution) and conferences of professional societies and nonprofit organizations that occur throughout the year.

Attending large scientific meetings and conferences requires out-of-town travel, time away from work and family, and of course, expenditures. Although some organizations provide scholarships to reimburse or defray advocate travel costs, building these expenses into the institution’s budget is highly recommended. Investing in the education and experience of its advocates benefits the institution in several ways including improving patient-focused research and dissemination of research findings to the community.

Two examples of meetings that are valuable to attend include the annual meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology and the annual meeting of the American Association for Cancer Research (AACR). Many cancer-specific organizations host annual conferences as well (e.g., San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium). At these conferences, advocates often present posters on behalf of their advocacy committee and attend specifically designed training programs. Advocates may also be invited to speak at scientific and/or educational sessions during the meeting. In addition, advocates should seek out advocacy-themed workshops and meetings sponsored by the NCI and the FDA. Many of these smaller workshops provide the option to participate via webinar, allowing advocates to learn without the burden of travel. In addition, there are online advocacy training modules, such as those created by Friends of Cancer Research, that allow an advocate to learn at his or her own pace (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Resources for research advocacy training

| Name of program | Cancer type | Organization | Mode | Website link |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| e-Training for Patients, Advocates and the Community | All cancers | Cancer Information and Support Network | Online | http://cisncancer.org/eTraining/free_e-Training.html |

| Various Research Advocacy Training Programs and Modules | All cancers | Research Advocacy Network | Online | http://researchadvocacy.org/advocate-institute/online-course-basics-research-advocacy |

| Accelerating Anticancer Agent Development and Validation Workshop Advocacy Education (AAADV) | All cancers | AACR, ASCO, Susan G. Komen, Duke University, and FDA | Online and in-person | https://www.acceleratingworkshop.org/2019/ |

| Research Advocate Training | All cancers | Facing Our Risk of Cancer Empowered (FORCE) | Online | http://www.facingourrisk.org/get-involved/how-to-help/volunteer-fundraise/volunteer.php#FRAT |

| Understanding Evidence-based Healthcare: A Foundation for Action | All cancers | Cochrane United States | Online | https://training.cochrane.org/resource/understanding-evidence-based-healthcare-foundation-action |

| Friends of Cancer Research | All cancers | Friends of Cancer Research | Online | http://www.progressforpatients.org |

| Project LEAD | Breast cancer | National Breast Cancer Coalition | In-person | http://www.breastcancerdeadline2020.org/get-involved/training/project-lead/project-lead-institute-2018.html |

| Respected Influencers through Science and Education (RISE) | All cancers | Young Survival Coalition | In-person | https://www.youngsurvival.org/get-involved/be-an-advocate/be-a-ysc-advocate#become-a-rise-advocate |

| Research Advocacy Training and Support (RATS) | Colorectal cancer | Fight Colorectal Cancer | In-person | https://fightcolorectalcancer.org/advocacy/research-advocacy/ |

| Advocates in Science | Breast cancer | Susan G. Komen | In-person | https://ww5.komen.org/GetInvolved/Participate/BecomeanAdvocate/BecomeanAdvocateinScience.html |

| Partners in Progress: Cancer Patient Advocates and FDA | All cancers | FDA | In-person | https://www.fda.gov/AboutFDA/CentersOffices/OfficeofMedicalProductsandTobacco/OCE/ucm569922.htm |

| Scientist←>Survivor Program | All cancers | AACR | In-person | https://www.aacr.org/AdvocacyPolicy/SurvivorPatientAdvocacy/Pages/scientistharr%3Bsurvivor-program___403E94.aspx#.W0OQpNhKhBw |

| Annual Advocate Program | Breast cancer | Alamo Breast Cancer Foundation | In-person | https://www.sabcs.org/Patient-Advocates#AdvocateProgram |

| Hear My Voice | Metastatic breast cancer | Living Beyond Breast Cancer | In-person | http://www.lbbc.org/living-metastatic-breast-cancer/hear-my-voice-program/hear-my-voice-how-apply |

| Young Advocate Program | Breast cancer | Living Beyond Breast Cancer | In-person | https://www.lbbc.org/young-woman/lbbc-resources/young-advocate-program |

To further their education and knowledge, advocates should also seek out research advocacy training such as that provided by the National Breast Cancer Coalition’s Project LEAD program, AACR’s Scientist-Survivor Program, Research Advocacy Network, or the Fundamentals Workshop at the Accelerating Anticancer Agent Development and Validation workshop. Once advocates complete formal training, they can seek out opportunities to serve as consumer reviewers for various funding agencies.

Develop an online presence

An online presence is a valuable tool to reach scientists and advocates at many levels. A well-maintained website encourages communication with researchers within the institution. It provides a platform for the advocacy committee to share qualifications and success stories and outline the policies that govern interaction between the advocacy committee and the scientists it supports. A scientist visiting the website can get to know the members and see projects on which the advocates have collaborated. In addition, a website allows a group to highlight special skills, educational opportunities, and outreach activities of committee members. Twitter is also a rich resource for advocates to build relationships with each other and with the larger research community. Healthcare hashtag groups provide an excellent forum to aggregate conversations around a disease focus (24) and can increase an advocate’s knowledge about the disease state (25). Twitter interactions allow advocacy committees to build relationships with one another, and they provide opportunities for advocates to learn about important resources and educational opportunities. Our committee’s Twitter account highlights members’ advocacy activities, showing the impact they have on the patient community outside the institution. This is something that many institutions may also like to highlight on their own social media accounts to show their impact on the community.

Challenges and future directions

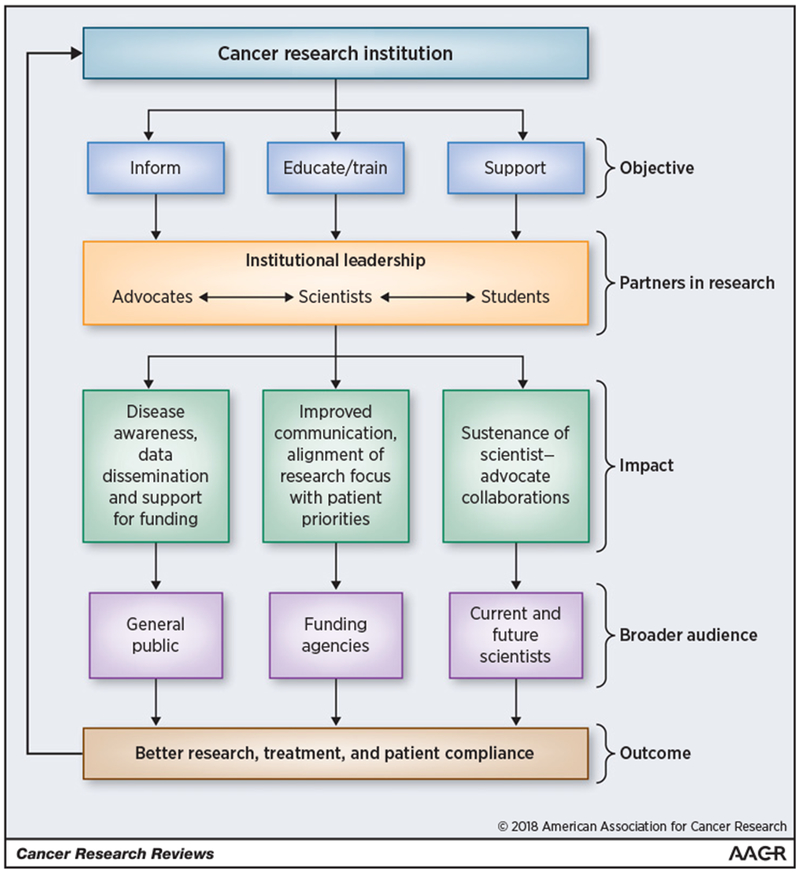

Collaboration between scientists and advocates is integral to making sure patients are represented in research and that their voices are heard. Many scientists find that collaboration with advocates strengthens their proposals by clarifying their goals and impact on patients. The relationship between advocates and scientists is mutually beneficial—as the advocates enrich ongoing research initiatives, they learn more about the latest scientific developments of their disease and future possibilities. Ultimately, both groups learn more about the other and develop an ongoing relationship characterized by a mutual respect and empathy. Figure 1 shows the framework for a successful scientist–advocate collaboration that can be set up at any cancer research institution. The leadership’s objective to encourage collaboration among scientists and advocates should be consistent. This includes financial support for advocacy-related activities and institutional recognition of service for faculty who serve as scientific advisors for the advocacy committees. Trainees should be encouraged to engage with advocates to ensure their research objectives are aligned with an unmet patient need in cancer research and that these collaborations become the norm among future generations of scientists. Working together, scientists and advocates can positively affect cancer research through improved treatment options and patient compliance. They are valuable allies in the fight against cancer.

Figure 1.

Comprehensive approach for promoting scientist–advocate collaboration at a cancer research institution. Leadership directly supports the education and training of advocates and scientists (including students) to work together as partners in the research process. That can lead to patient-focused research goals and increased dissemination and awareness of cancer research and findings. Collectively, the impact on the community through better research outcomes can promote the overall mission of the cancer research institute, thus creating a sustainable scientist–advocate collaboration for current and future generations.

Acknowledgments

We want to thank all patients and their families who contribute in various ways to improve cancer research. We would also like to thank Drs. Minetta Liu, Claudine Isaacs, and Robert Clarke for their support. A special thanks to Dr. Jane Perlmutter for her guidance early in our group’s development. Georgetown Breast Cancer Advocates was formed in April 2011 and has been partly supported through Public Health Service award 1P30-CA-51008 (Lombardi Comprehensive Cancer Center Support Grant) and generous gifts (Nina Hyde Breast Cancer Research Funds and Women and Wine). Ayesha N. Shajahan-Haq is a recipient of Public Health Service NCI grant R01CA201092.

Footnotes

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

R. Carlin is Executive Director at American Association on Health and Disability. No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed by the other authors.

References

- 1.Perlmutter J, Roach N, Smith ML. Involving advocates in cancer research. Semin Oncol 2015;42:681–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Perlmutter J, Bell SK, Darien G. Cancer research advocacy: past, present, and future. Cancer Res 2013;73:4611–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Finn R Surveys identify barriers to participation in clinical trials. J Natl Cancer Inst 2000;92:1556–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tejeda HA, Green SB, Trimble EL, Ford L, High JL, Ungerleider RS, et al. Representation of African-Americans, Hispanics, and whites in National Cancer Institute cancer treatment trials. J Natl Cancer Inst 1996;88:812–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lewis JH, Kilgore ML, Goldman DP, Trimble EL, Kaplan R, Montello MJ, et al. Participation of patients 65 years of age or older in cancer clinical trials. J Clin Oncol 2003;21:1383–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Absolom K, Holch P, Woroncow B, Wright EP, Velikova G. Beyond lip service and box ticking: how effective patient engagement is integral to the development and delivery of patient-reported outcomes. Qual Life Res 2015;24:1077–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ciccarella A, Staley AC, Franco AT. Transforming research: engaging patient advocates at all stages of cancer research. Ann Transl Med 2018;6:167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Huebner J, Rose C, Geissler J, Gleiter CH, Prott FJ, Muenstedt K, et al. Integrating cancer patients’ perspectives into treatment decisions and treatment evaluation using patient-reported outcomes–a concept paper. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl) 2014;23:173–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dellson P, Nilbert M, Bendahl PO, Malmstrom P, Carlsson C. Towards optimised information about clinical trials; identification and validation of key issues in collaboration with cancer patient advocates. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl) 2011;20:445–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Michaels M, Weiss ES, Guidry JA, Blakeney N, Swords L, Gibbs B, et al. The promise of community-based advocacy and education efforts for increasing cancer clinical trials accrual. J Cancer Educ 2012;27:67–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2018. CA Cancer J Clin 2018;68:7–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wittet S, Aylward J, Cowal S, Drope J, Franca E, Goltz S, et al. Advocacy, communication, and partnerships: mobilizing for effective, wide-spread cervical cancer prevention. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2017;138:57–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mishkin G, Minasian LM, Kohn EC, Noone AM, Temkin SM. The generalizability of NCI-sponsored clinical trials accrual among women with gynecologic malignancies. Gynecol Oncol 2016;143:611–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Davis C, Salo L, Redman S. Evaluating the effectiveness of advocacy training for breast cancer advocates in Australia. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl) 2001;10:82–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Katz ML, Archer LE, Peppercorn JM, Kereakoglow S, Collyar DE, Burstein HJ, et al. Patient advocates’ role in clinical trials: perspectives from Cancer and Leukemia Group B investigators and advocates. Cancer 2012;118:4801–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Samson S, Northey JJ, Plaks V, Baas C, Dean I, LaBarge MA, et al. New horizons in advocacy engaged physical sciences and oncology research. Trends Cancer 2018;4:260–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Andejeski Y, Bisceglio IT, Dickersin K, Johnson JE, Robinson SI, Smith HS, et al. Quantitative impact of including consumers in the scientific review of breast cancer research proposals. J Womens Health Gend Based Med 2002;11:379–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Carroll PR, Advocates PC. The impact of patient advocacy: the University of California-San\sFrancisco experience. J Urol 2004;172:S58–61; discussion S-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kovtun IV, Engh J, Jatoi A. A survey of patient advocates within the National Cancer Institute’s Prostate Cancer SPORE Program: who are they? what motivates them? what might they tell us? J Cancer Educ 2008;23:222–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brody JG, Morello-Frosch R, Zota A, Brown P, Pérez C, Rudel RA. Linking exposure assessment science with policy objectives for environmental justice and breast cancer advocacy: the northern California household exposure study. Am J Public Health 2009;99:S600–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hoch JS, Brown MB, McMahon C, Nanson J, Rozmovits L. Meaningful patient representation informing Canada’s cancer drug funding decisions: views of patient representatives on the Pan-Canadian Oncology Drug Review. Curr Oncol 2014;21:263–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Singer DS, Jacks T, Jaffee E. A U.S. “Cancer Moonshot” to accelerate cancer research. Science 2016;353:1105–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Welch DR, Antalis TM, Burnstein K, Vona-Davis L, Jensen RA, Nakshatri H, et al. Essential components of cancer education. Cancer Res 2015;75: 5202–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Katz MS, Utengen A, Anderson PF, Thompson MA, Attai DJ, Johnston C, et al. Disease-specific hashtags for online communication about cancer care. JAMA Oncol 2016;2:392–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Attai DJ, Cowher MS, Al-Hamadani M, Schoger JM, Staley AC, Landercasper J. Twitter social media is an effective tool for breast cancer patient education and support: patient-reported outcomes by survey. J Med Internet Res 2015;17:e188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]