Abstract

Emergency departments (EDs) face problems with overcrowding, delays, cost containment, and patient safety. To address these and other problems, EDs increasingly implement an approach called Lean thinking. This study critically reviewed eighteen papers describing the implementation of Lean in fifteen EDs in the US, Australia, and Canada. An analytic framework based on human factors engineering and occupational research generated six core questions about the effects of Lean on ED work structures and processes, patient care, and employees as well as the factors upon which Lean’s success is contingent. The review revealed numerous ED process changes, often involving separate patient streams, accompanied by structural changes such as new technologies, communication systems, staffing changes, and the reorganization of physical space. Patient care usually improved following implementation of Lean, with many EDs reporting decreases in length of stay, waiting times, and proportion of patients leaving the ED without being seen. Few null or negative patient care effects were reported and studies typically did not report patient quality or safety outcomes beyond patient satisfaction. The effects of Lean on employees were rarely discussed or measured systematically but there were some indications of positive effects on employees and organizational culture. Success factors included employee involvement, management support, and preparedness for change. Despite some methodological, practical, and theoretical concerns, Lean appears to offer significant improvement opportunities. Many questions remain about Lean’s effects on patient health and employees and how Lean can be best implemented in health care.

1. Introduction

The need for improvement in emergency departments (EDs) with respect to the cost of care, the speed of service, overcrowding, and patient safety is now widely accepted [1–4]. In an attempt to achieve broad improvement, health care organizations worldwide increasingly adopt an approach called “Lean thinking” (see Table 1 for a description of Lean) [5]. In a 2009 survey of US hospitals, 53% reported having implemented Lean to some extent; of those hospitals, 60% reported implementing Lean in the ED [6]. Furthermore, some public health care systems, including the UK National Health Service (NHS) [7], have adopted or are planning to adopt Lean as a key lever for decreasing costs and improving the quality and safety of care.

Table 1.

Description of Lean.

Key principles:

|

Tools and methods include:

|

Lean thinking

Lean thinking is a bundle of concepts, methods, and tools derived from the Toyota Production System (TPS), the production philosophy of Toyota Motor Corporation. Lean was first implemented in US auto manufacturing in an attempt to replicate Toyota’s success and has subsequently spread to other manufacturers (e.g., Boeing), to service industry (e.g., Tesco), and to the public sector (e.g., UK National Health Service). The key principles of Lean are listed in Table 1. Chief among them is the need to eliminate unnecessary waste. Waste is anything that does not add value to the customer. For example, if the ED patient is the customer, two wastes might be waiting to be seen or undergoing (and paying for) a duplicate test. As waste is eliminated, products (or patient care) flow smoothly, continuously, and without errors from one step to another. After work is completed at one step, it is not pushed to the next step; instead, work is pulled when it is ready to be processed at the next step so that work does not pile up. Problems that arise in the process are to be identified immediately, their causes understood, and a solution applied. Both frontline workers and management are responsible for the quality of work and both are involved in the problem-solving process, often by participating in rapid continuous improvement sessions called kaizen. Indeed, although the support and participation of leadership is crucial, contemporary prescriptions of Lean insist that workers must be involved and empowered to inspect and improve their own work. Workers and management have at their disposal numerous tools and methods to implement the above principles (Table 1).

The much-celebrated success of Lean in manufacturing [8]and success stories of Lean in the NHS and other health care systems [9–12] have resulted in a strong push for introducing Lean to health care [13–16] and more particularly to the ED [17–21]

Given enthusiasm about Lean as an approach to improving emergency care, this paper critically reviews and analyzes the empirical literature on the implementation of Lean in the ED. The present review differs from prior work [9,22–25] in five ways. First, it focuses specifically on the ED. Second, it reviews how Lean affects health care employees in addition to patients. Third, it assesses prior studies for evidence of undesirable and null effects of Lean in addition to desirable effects and in general takes a much-needed critical approach [25–27]. Fourth, it analyzes the factors that may contribute to variability in Lean’s success. Fifth, this study systematically analyzes each prior study according to an analytic framework rather than using studies to build a narrative about Lean in health care. That framework, described below, is based on human factors/systems engineering principles and on occupational research on Lean outside of health care.

2. Methods

Analytic framework

The analytic framework used to generate the core research questions for this review (Figure 1) depicts Lean as having transformative effects on the structure and process of ED work. Structure refers to work system elements such as tools and technology. worker factors (e.g., education/training, responsibilities), organizational factors (e.g., policy, staffing, incentives), communication systems, and the physical environment (e.g., spatial arrangement, noise, lighting) [28, 29]. Process refers to the actual activities of patient care and related work [29] and the “flow” of the patient through the ED or broader care delivery system [30].

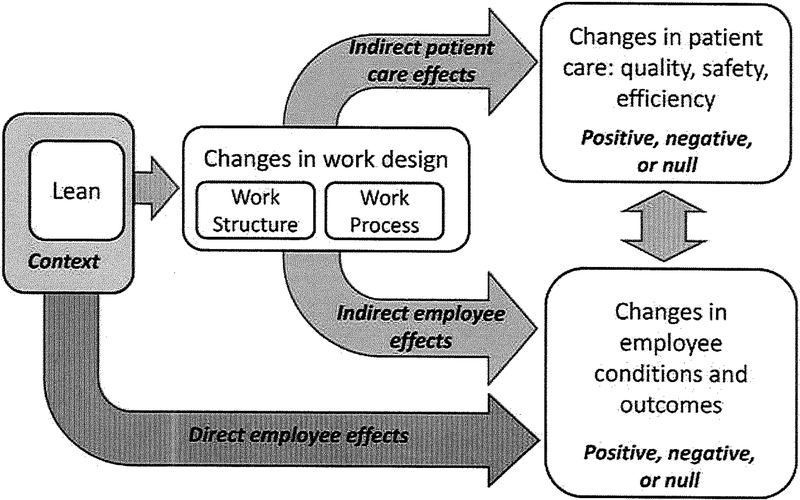

Figure 1.

A model of Lean in health care, proposing that (a) Lean affects patient care and employees indirectly, by changing work structure and process, (b) Lean affects employees directly, (c) employee and patient care changes can affect one another, and (d) Lean is implemented in a patticular context and that the success of Lean is contingent on how a particular Lean implementation fits into the local context.

Understanding how Lean transforms work structure and process is important because those transformations will determine patient care quality and safety indicators such as length of stay, medication errors, and patient satisfaction [29, 31]. How Lean affects patient care, albeit indirectly through structure and process change, ultimately determines the success of Lean.1

By transforming work structures and processes, Lean also affects the employees responsible for carrying out the work, as studies of Lean outside of healthcare demonstrate [32–36]. A representative finding comes from Sprigg and Jackson’s study of call center employees: the introduction of Lean imposed dialog scripting and performance monitoring; this led to lower job control, task variety, skill utilization, and role clarity and higher workload and role conflict; those changes in working conditions were then found to relate to employees’ job strain outcomes Gob-related anxiety and depression) [37]. The effects of Lean on employees may also be desirable ones [38, 39]

Apart from the employee effects of Lean-related changes to the actual work, there may also be a direct path by which Lean affects employees. For example, two intended effects of implementing Lean are to shift employees from merely doing their work to looking for ways to improve it and the empowerment of workers to suggest and implement changes [40]. Similarly, changes in motivation, information, and social standing, to give three examples, might result from the mere involvement of workers in Lean projects, independent of the work changes brought about by the actual projects. Another possible direct effect of Lean is the anxiety brought about by fears of losing one’s job or having a less satisfying job after clinical work is made more efficient.

If workers are affected by Lean, resulting in higher or lower motivation, satisfaction, anxiety, task control, and more, it is reasonable to suggest that patient care, and thus patient outcomes, will improve or suffer. Following this logic, Mehta and Shah’s model of employee effects of Lean proposes that employee outcomes both affect and are affected by “organizational outcomes” such as “productivity” and “performance” [41]. In the healthcare setting, however, the relationship of interest is between employee conditions and outcomes on one hand, and the quality, safety, and efficiency. of patient care on the other [28].

“Lean production is … not a single unitary production concept, either in its design or in its implementation” [33]. Instead, organizations select among numerous principles, tools, methods, and philosophies [42]. Generic Lean principles are interpreted and adapted for each organization’s unique local context [43]. This has led researchers to propose that the effects of Lean are contingent on how and where Lean is implemented [33, 37, 41].

The components of the analytic framework discussed above yield six study questions which guided the analysis of reviewed studies of Lean in the ED. Those questions are:

How does Lean transform work structures and work processes?

How does Lean affect patient care (quality, safety, efficiency)?

How does Lean affect employee working conditions (e.g., autonomy, workload) and outcomes (e.g., motivation, satisfaction) indirectly, by transforming work structures and processes?

How does Lean affect employee outcomes directly, independent of changes to work structures and processes?

How are patient care effects and employee effects of Lean linked?

How are patient care and employee effects of Lean contingent on the features of (a) the organization implementing Lean and (b) the design and implementation of Lean?

Literature review

The scholarly literature spanning January 2005 to January 2010 was searched for papers describing Lean implementation in the ED. Three database searches were conducted: (1) the medical database PubMED, using the search string “Lean OR Toyota Production System;” (2) the business/management database ABI/INFORM (Scholarly Journals) using “Lean OR Toyota Production System” and a collection of health care terms (e.g., hospital*, patient*, health care, clinic*, emergency department*, etc.); and (3) the interdisciplinary database Google Scholar using “emergency room OR emergency medicine OR accident & emergency OR emergency department AND Lean production OR Lean thinking.” Twelve specific journals, including Annals of Emergency Medicine, Journal of Emergency Medicine, Emergency Medicine Journal, American Journal of Emergency Medicine, and International Journal of Emergency Medicine, were searched using the terms “Lean” and “Toyota.” Finally, the references of retrieved articles and of existing articles from a broad literature collection on Lean in health care were searched for other relevant papers.

Non-empirical papers and papers reporting on work design or improvement projects not identified as Lean [44–46] were excluded from the review. Conference abstracts [47–56] and similar condensed publications [57, 58] were excluded because they provided insufficient information. Larger scale (e.g., hospital-wide) studies that included the ED were excluded due to space limitations and difficulty extracting ED-specific content [10, 59–67]. Studies of pre-ED triage only were also excluded [68]. Finally, studies not published in the English language were excluded.

3. Results

Eighteen articles describing Lean initiatives in 15 EDs met inclusion criteria (Table 2).

Table 2.

List of reviewed studies and descriptions of study sites and Lean project teams.

| Study | Study site | Project team composition |

|---|---|---|

| Al Darrab et al, 2006 [69] | EDs at Hamilton Health Sciences, a three-site tertiary/quaternary care facility, Canada | Emergency Medicine/Cardiology leaders and quality improvement facilitators set improvement goals. Project team included pharmacists, staff nurses, managers, educators, residents, nursing program directors, project co-leaders from the ED and Cardiology, quality improvement facilitators, Emergency Medical Services representatives |

| Ben-Tovim etal, 2007, 2008*, King et al, 2006* [70] [71] [72] | ED at Flinders Medical Centre, a 500-bed community teaching hospital, Australia | Facilitators worked with senior staff to make initial assessments then involved multidisciplinary groups of frontline staff to diagnose problems, document the process, and implement and evaluate process redesign. “Participants were drawn from the full range of staff working within the ED, from patient care assistants and clerical staff to junior and senior nursing and medical staff |

| Dickson et al2008, 2009a [73] [74] | Level I trauma center at University of Iowa Hospitals and Clinics, a 700-bed teaching hospital, USA | Improvement team comprised of two ED physicians, two ED nurses, an ED physician assistant, two non-ED physicians, two radiology technicians, a laboratory technician, five industrial engineers, and five external participants from a local business council (representing the patient perspective) |

| Dickson et al, 2009b [75]† | Hospital A: ED at a 690-bed teaching hospital, unspecified urban location Hospital B: ED at a 889-bed community hospital, unspecified urban location Hospital C: Level II trauma center at a 461-bed community hospital, unspecified location Hospital D: Level I trauma center at a 700-bed teaching hospital, unspecified rural location |

Hospital A: Improvement driven by consultant and focus area leader. “Frontline workers not initially asked to provide ideas for process redesign but in the course of implementation were inspired to suggest incremental process improvements.” Hospital B: “Frontline workers,” “led by a consultant team” Hospital C: ED management. “Ideas of frontline workers not sought.” Hospital D: See Dickson et al, 2008, 2009a, above |

| Eller, 2009 [76] | ED at St. Luke’s Episcopal Hospital, a 900-bed faith-based teaching hospital, USA | “Staff members” |

| Ieraci et al, 2008* [77] | ED at Bankstown Hospital, a 400-bed referral hospital, Australia | Intervention developed in “workshop sessions involving key clinical and management staff within the ED” |

| Jacobson et al, 2009 [78] | Level I trauma center at Vanderbilt University Medical Center, a 600-bed teaching hospital, USA | Any physician (resident or attending) wanting to submit an idea, concern, or observation. Although 17% of submissions were from nurses and other staff, the system was initially aimed at physicians. |

| Kelly et af, 2007* [79] | ED at Western Hospital, a 300-bed community teaching hospital serving adult patients only, Australia | “Collaborative design and implementation process involving all professional groups and grades of staff” |

| Kulkarni, 2007, 2008 [20] [80] | ED at Yale-New Haven Hospital, a 950-bed teaching hospital, USA | Team included “representatives from the emergency department, such as nursing, midlevel staff, staff physicians, resident physicians, greeters, registration, security, and technicians/patient care assistants” and “hospital leadership and representatives from inpatient physician and nursing leadership as well as general hospital departments - such as transport and environmental services.” |

| Ng et al, 2010 [81] | ED at Hotel-Dieu Grace Hospital, a 300-bed faith-based tertiary care hospital, Canada | A Lean consultant and “emergency physicians; nurses; nurse practitioners; porters; clerks; cleaning staff; administrators; the ED director, unit manager and educator; the hospital’s senior vice-president; and representatives from diagnostic imaging, laboratory, respiratory therapy, home care and information services.” |

| Parks et al, 2008 [82] | Level I trauma center at Parkland Memorial Hospital, a 950-bed community teaching hospital, USA | Project team included hospital administration, trauma surgeons and nursing staff, and performance improvement personnel trained in Lean Six Sigma |

| Schooley, 2008 [83] | ED at Presbyterian Hospital, a 531-bed regional medical center part of a not-for-profit integrated healthcare system, USA | At first, Lean consultant and managers only. Later, physician, nurses, and other staff were interviewed and became involved in suggesting and implementing changes. Improvement teams included both supporters of change and resistors who were also social leaders in the organization. |

| Stephens-Lee, 2006 [84] | ED at Dartmouth General Hospital, a 131-bed community hospital, USA | Lean consultant and “nurses and clerks from the ED and inpatient units, the bed manager, an inpatient Health Services manager, chief of staff and engineers.” |

| Woodward et al, 2007 [85] | ED at Seattle Children’s Hospital, a 250-bed pediatric teaching hospital, USA | Not described |

Characteristics of reviewed studies

Table 2 describes the study sites and participants. Study sites tended to be larger teaching hospitals, usually situated in the United States, with the remaining sites in Austrialia or Canada. Project team composition varied among sites, but with one exception (Hospital C in [75]), all Lean involved frontline staff in some way. The staff involved ranged from clinicians to clerks, assistants, engineers, and representatives of the patient community. Their involvement ranged from providing suggestions to designing and implementing changes. Usually, a quality improvement facilitator or Lean consultant was involved and management or senior staff was often involved throughout Lean initiatives.

In most cases Lean was the sole approach used. Three studies [69, 82, 83] combined Lean with Six Sigma, a quality improvement method based on minimizing variability, while another also “borrowed from many other manufacturing philosophies” [71]. In other studies, changes such as new leadership [83], increased staffing [77], or other ongoing quality improvement projects [78] were concomitant with Lean.

The typical approach to Lean began with process mapping, wherein the current process steps were diagramed. Sometimes, times for each step were measured [73, 75, 82, 84] or estimated [81] and in one study the location of staff at each step was diagramed [80]. Some type of analysis typically followed, wherein bottlenecks, waste, or other problems were identified and causes or correlates of those problems were sought. Following brainstorming and sometimes future-state mapping of possible improvements, project teams undertook process redesign. Often, changes were evaluated and adjusted in an iterative way; such iteration is a vital component of the Plan-Do-Study-Act cycle adopted by some studies [69, 72, 83] and of the kaizen rapid process improvement workshops reported in other studies [73, 78, 81, 85]. kaizen, or “small, low-cost, low-risk improvements that can be easily implemented” [78], is a cornerstone of Lean and is not surprisingly the chief and sometimes sole Lean tool used in health care [75]. Other components of Lean included education on Lean [72, 75, 78, 81], goal setting [79, 81, 83], formal root cause analysis [69, 79, 82, 83], and various types of data collection [82–84]

How does Lean transform work structures and work processes?

Process redesign was a formal component of all EDs’ Lean initiatives except in one ED where redesign was planned but not yet implemented [84]. Table 3 lists examples of process change, many of which involved some separation of patients into “streams” or “tracks.” New or transformed processes were accompanied by new standard operating procedures, consistent with the focus of Lean on creating standard work. Importantly, as depicted in Figure 1, Lean does not simply alter the process of work: in the reviewed studies, numerous work structure changes accompanied process change. These included (a) new data collection and monitoring systems, (b) education and training, (c) changes to tools and technologies, (d) new systems for communication and teamwork, (e) changes in staffing, roles, and responsibilities, and (f) reassignment or reorganization of physical space. Table 3 provides examples of work system changes within each category.

Table 3.

Work process and work structure changes resulting from implementation of Lean.

| Process changes | Specific examples |

|---|---|

| New processes and related operating operating |

|

| System changes | Specific examples |

| Data collection and monitoring |

|

| Education/training |

|

| Tools/technologies |

|

| Communication and teamwork |

|

| Staffing reassignment / new roles / new responsibilities |

|

| Reassignment / reorganization of space |

|

| Other |

How does Lean affect patient care?

In Table 4, effects on process quality (e.g., waiting times, length of stay) are separated from the ultimate outcomes of patient care (e.g., patient health, satisfaction with care). Several trends can be seen. First, improvements were consistently reported. After Lean, most EDs saw reductions in length of stay, proportion of patients leaving without being seen, and waiting times. This sometimes resulted in better compliance with national standards. Second, patient outcomes often improved as well but such improvements were rarer, and patient outcomes were less commonly measured compared to process improvements. Changes in average patient health outcomes from pre- to post-Lean were never measured, even though timelier care would be expected to result in better outcomes. Patient safety changes were only measured in one study, and even then only indirectly [71]. Third, studies predominantly reported improvements and there were few reported decrements in patient care or failures to achieve improvement. Fourth, not every study adequately reported pre- and post metrics. In some cases, “measures of success” (e.g., door-to-balloon time, door-to-needle-time) were taken but not reported [69]. In others, measures such as patient satisfaction were not described [83], statistical tests were not used to test pre-post differences [20, 75], or no numerical data were given to support reported changes [83]

Table 4.

Effects of Lean on patient care.

Improved care process

|

Improved patient outcomes

|

| Worsened care process or lack of improvement |

| Worsened patient outcomes or lack of improvement |

| Other |

How does Lean affect employee working conditions and outcomes indirectly?

Indirect effects of Lean, those resulting from the types of process and structure changes described in Table 4, were not consistently measured or discussed (Table 5). Some studies, however, noted that after changes were made, staff were less prone to aggression, more courteous, more satisfied with their job and less likely to leave, and faced lower workloads. Further, better utilization of staff; including more time available for supervision and education; communication improvements; (perceived) loss of autonomy due to standardization; and an increased sense of control were among reported working conditions resulting from Lean-driven changes.

Table 5.

Indirect and direct effects of Lean on employees.

| Study | Indirect effect of Lean | Direct effect of Lean | ||

| Al Darrab |

|

|

|

|

| Ben-Tovim, King, etal |

|

|

|

|

| Dickson et al (2008, 2009a) |

|

|

|

|

| Dickson et al (2009b) |

|

|

|

|

| ||||

| ||||

| ||||

| Eller |

|

|

|

|

| Ieraci et al |

|

|

|

|

| Jacobson et al |

|

|

|

|

| Kelly et al |

|

|

|

|

| Kulkarni |

|

|

|

|

| Ng et al |

|

|

|

|

| Parks et al |

|

|

|

|

| Schooley |

|

|

|

|

| Stephens-Lee |

|

|

|

|

| Woodward et al |

|

|

|

|

Empty circle = employee effects not measured or discussed; Half-filled circle employee effects discussed but assessed indirectly or anecdotally, Filled circle = employee effects discussed based on standardized measures.

How does Lean affect employee outcomes directly?

Direct employee effects resulted from the mere presence of, and employees’ participation in, the Lean initiative, quite apart from any operational changes made through Lean (Table 5). By participating in Lean sessions, process mapping, and process redesign, employees became better aware of their work and the problems therein, gained new values, and were more eager to participate in and to accept changes created by Lean. Consistent with the claims of Lean experts, some studies indeed reported that their employees became empowered to suggest future changes [72] and to control the design of their own work [75]; the high participation rates in process improvement described in one study are a testament to such empowering effects of Lean [78]. Indeed, some studies suggested that Lean may have even brought about a new participative, continuous improvement culture such that participating in Lean led frontline staff to take control of their own work and to participate more in shared governance [76, 78, 83]. In turn, managers learned to defer to their frontline staff and to value their input. Less commonly, the introduction of Lean was associated with at least initial resistance and concern over possible changes.

Unfortunately, most of the employee effects described above were not systematically assessed and were either implied by articles’ authors or based on anecdotal evidence. For example, only one study actually measured staff satisfaction (using surveys) and even so did not report numeric values or statistical tests [83].

How are patient care effects and employee effects of Lean linked?

Given the lack of information on employee effects, it was not surprising that no study measured the relationship between Lean-related patient outcomes and employee outcomes, or the reverse. However, the authors of one study wrote, “quality improvement is intimately linked to how individual providers interact with patients, on a day-to-day basis in the outpatient clinic and inpatient unit frontlines” [73]. Because of this vital interaction, it is possible that patient and employee outcomes influenced one another in the reviewed studies. One way that this influence might play out was suggested by another study: “Patients’ irritation with delays can result in displaced anger aimed at nurses and physicians, which deflates staff morale” [83]. This suggests that reductions in delays can improve employees’ quality of work life. In turn, when staff carry out improved work processes, they may exhibit increased courtesy toward patients [73].

How are patient care and employee effects of Lean contingent on the features of (a) the organization implementing Lean and (b) the design and implementation of Lean?

Only one study, Dickson et a1 [75], included multiple Lean implementation across multiple EDs and therefore only this study was able to directly address contingencies. Dickson et a1 [75] wrote that “Lean is not a panacea, but rather a tool that may or may not succeed, according to the efforts surrounding its use” and more formally proposed that Lean’s variable success could be understood as “context +mechanism = outcome,” where context refers to the local context of the ED and mechanism refers to Lean [75]. Based on a comparison of four EDs, Dickson et a1 proposed that the two key contextual contingencies were (a) the involvement of frontline staff in Lean initiatives, and (b) leadership commitment to Lean. Although no other study compared EDs or hospitals (but see other comparative studies of Lean in health care [15, 62]), many of the reviewed studies proposed some of the contingency factors upon which their success was based (Table 6).

Table 6.

Contingency factors suggested by or inferred from reviewed studies.

| Pre-Lean |

| Management involvement |

| Frontline staff involvement |

| Lean process |

| Lean change initiatives |

| Post-change |

4. Discussion

Five years have passed since the first well-publicized Lean initiatives in US health care at Virginia Mason Medical Center [11, 15, 86]. In that time, many EDs, among other health care delivery units, have begun to apply Lean as a way to fight problems such as errors, delays, and overcrowding. This review revealed robust opportunities for improvement in EDs and hospital-wide using Lean but also revealed considerable limitations in Lean implementations and in reports thereof.

Lean is often characterized as a process improvement approach. Thus, not surprisingly, process change was a key component of Lean in the ED. Some process changes resembled those already advised or attempted for EDs, such as “fast-track” streaming [87]. This is indicative of Lean’s role as a philosophy and an approach to change rather than as a specific process solution [88]. Perhaps this is why some EDs reported improvements with Lean but not with earlier change efforts [71, 83]. Process changes and accompanying protocols served to standardize care. In routine situations anticipated by protocols, standardization can be of great benefit, but safety scientists contend that over-standardization can make a system brittle and less able to adapt to unexpected variation [89, 90]. Further work must investigate the extent to which individual providers and EDs as a unit can be resilient following work standardization.

In addition to process change, work structures were modified as a result of Lean. The implication is that implementing Lean is not simply a matter of changing the way things are done. Problematic work structures are also identified and rectified through Lean, even if the focus is on process. Further, resources (e.g., staffing, technology, communication) often need to be allocated to support new processes. Practitioners will need to be aware of the possibility of changing structures and not just processes and researchers will need to measure structural changes, intended and unintended.

Patient care typically improved as a result of Lean-driven process and structure changes, implying the possible value of Lean. One would expect improvements in length of stay, waiting times, and other commonly reported efficiency measures to be accompanied by improved patient health, fewer errors, or more appropriate care. Indeed, a recent study found a link between ED overcrowding and medication errors [91]. However, reviewed studies lacked measures of quality and safety outcome indicators, something that will need to be rectified to determine the whole impact of Lean on patients [92].

Desirable patient care effects of Lean dominate both in the presently reviewed ED literature and in health care more generally [93]. One reviewed ED study noted, “there is a current trend of reporting bias toward publishing positive—and more often than not immediate—results because hospitals who failed to achieve the intended behavioral changes do not come forward to openly analyze the reasons for their failure” [75]. It is possible that a publication bias, not universally positive effects of Lean, is behind the lack of null and negative results [22]. Full disclosure by study authors and formal inclusion of the possibility of undesirable and null effects of Lean (e.g., as in Figure 1) should characterize future reports of Lean in health care. Closely related is the need for better reporting of findings, including lists of all measures with descriptions of each, numeric values (central tendency, variability), and appropriate statistical tests [22]. Other methodological needs are more longitudinal research [22, 75], the use of comparison groups [22], the inclusion of covariates to control for secular changes besides Lean [77], and more attention to the possibility of selection bias [75].

Employees can be affected in two distinct ways, indirectly and directly, hut most reviewed studies tended to avoid measuring those effects or even discussing their possibility. Improving employee outcomes was not typically a goals of Lean; as one study put it, “the purpose of this LEAN initiative was to improve the care of patients who visited our emergency department” [76]. When another study found that Lean allowed senior physicians to spend more time on direct supervision, study authors referred to this as “a by-product of the initiative” [79]. Only one study repeatedly mentioned the aim to improve employees’ working conditions and this was the only study to systematically measure changes in job satisfaction [83]. Disregard of Lean’s employee effects reveals an underestimate of the power of Lean to empower workers and to improve working conditions. The improvements in Table 5, although sporadic and poorly assessed, should inspire systematic attempts to achieve employee benefits of Lean. In parallel, Lean implementers and researchers should be aware that Lean can increase workload, threaten autonomy, and bring about anxiety. These undesirable employee effects are well documented in the broader Lean literature [32–39, 94–97] but may not show up in reports on Lean in health care either because of how Lean is implemented in health care or because studies in health care simply do not measure employee effects. Measures of such effects are generally available to implementers and researchers in compendia of work measures [98, 99] and individual validated questionnaires for perceived working conditions, organizational culture, job satisfaction, empowerment, fear of job loss, and more. Additionally, implementers can devise measures—observational, surveys, interviews—that assess specific employee effects of Lean (e.g., the extent to which workers feel they are able to suggest or initiate changes; acceptance of Lean). Once employee effects are appropriately measured, it will be possible to assess links between employee effects and patient care effects of Lean.

The possibility of direct employee effects, those related to “mere exposure” to Lean, is reminiscent of the Hawthorne effect, the phenomenon that change efforts bring about positive effects in workers merely because more interest is paid to the workers. Considering the Hawthorne effect can be instructive for understanding Lean in the ED in three ways. First, the Hawthorne effect is typically regarded as a confound, meaning that the improvements in Table 4 and those reported in other Lean studies may not be the result of better designed work; as the spotlight on Lean fades, so may the improvements. Second, the Hawthorne effect is a non-trivial way to improve work. It inspired the Human Relations Movement, which promoted paying greater attention to the human element of work, addressing workers’ psychological needs, and letting workers feel involved; thus, according to the Human Relations school of thought, Lean can achieve real improvements if it is worker-centered. Third, the major criticism of the Human Relations Movement was that it disproportionally attempted to make workers feel special without substantially altering the design of work. Subsequent work, for example that of Sociotechnical Systems Theorists and macroergonomists, demonstrated that the most successful change efforts are ones that attend to both humanistic needs and the operational needs for well designed work. By implication, it is important to attend to both direct (“Hawthorne-like”) and indirect (“operational”) effects of Lean.

Finally, EDs in this study differed in their characteristics and they implemented Lean in different ways. For example, studies differed in which components of Lean were implemented, the nature of worker involvement and management support, and the types of changes implemented. Further work will need to assess more closely how those context differences relate to variability in Lean’s patient care and employee outcomes. Such investigations will yield a better understanding of the “critical success factors” for Lean [100]. Nine success factors, derived from this review and a broader (unpublished) review of Lean in hospitals, are hypothesized here and may be of practical value to Lean implementers (Table 7).

Table 7.

Practical suggestions for successful Lean implementation.

| Be ready for change. Prior to implementation there should be a shared recognition that problems exist and that improvements are needed. Failing this, Lean may be viewed as a wasted effort or as dubiously motivated (“Are they trying to make us work faster?” “Are they cutting costs?”). |

| Take a human-centered approach. Recognize the value of people (e.g., workers, patients) and involve them in Lean initiatives to the extent possible. Consider the employee effects of Lean alongside patient care effects. Attend to people’s needs (e.g., worker’s need for control, patients’/families’ need for information). Address concerns such as “How will increased efficiency and performance measurement affect my job?” Practitioners will need to make time and effott for Lean projects, even when they are non-mandatory and non-compensated. |

| Secure expertise. An external expelt on Lean, change management, or quality improvement can educate internal stakeholders and help to facilitate initial effmis. However, over time internal stakeholders (e.g., clinicians), and not consultants, will need to use their expettise to translate Lean from general tools and principles to their local context. Efforts should be undettaken to provide intemal stakeholders with expertise in Lean and to ensure Lean activities can continue after the external expert denalts. |

| Obtain top management support and resource allocation. Without the material and nonmaterial resources needed to do a thorough job, Lean will not succeed. Lean patticipants will need the authority to obtain information, undertake changes and make decisions. Budgetary needs will include worker time participating in Lean; payments to consultants and internal coordinators; education costs; and the costs of implementing, evaluating, and fine-tuning changes. Managers not only provide unique perspectives (e.g., on how multiple units or services are integrated) but their suppmi and involvement also build motivation and legitimate Lean as a wo1ihwhile activity. |

| Secure leadership. A person or group of people will need to act as visible leaders of Lean initiatives. These leaders need not be formal leaders, although project champions who are well respected in their social group will best motivate their peers. Leaders will not only motivate; they will also lead imorovement projects. |

| Aim for culture change. Expetts on Lean argue that to implement Lean, it is not sufficient to apply a few tools. A successful Lean implementation will aim for and achieve culture change [88]. One culture change that Lean can facilitate that future implementers should perhaps strive for is the incorporation of the scientific method into organizational problem solving. Likewise, Lean can be a mechanism for establishing evidence-based decision making or a learning culture. |

| Adapt Lean to the local context. Each of the 15 EDs reviewed here interpreted and implemented Lean in a distinct way. There must be no misconceptions that Lean is a prepackaged program that can be purchased off the shelf and thusly installed. Many decisions are required (e.g., who are our internal/external customers? What tools do we use and how?), many generic concepts will need to be adapted for local use, many adjustments will be needed over time, and all this will require resources. |

| Improve continuously. Lean does not conclude after the first wave of projects. Plans should be made to sustain Lean and to continuously evaluate and adjust previous changes and to plan further change. Part of this should include establishing the architecture (e.g., education, budget, top management commitment) necessary to sustain Lean in the face of evolving needs, staff turnover, and other disruptions. |

| Learn from prior experiences. No amount of advice here can substitute for learning from prior experiences with Lean—one’s own and one’s colleagues’. There is now a growing literature describing how health care units, organizations, and health systems have implemented Lean and, to a lesser extent, the “lessons (they) learned.” There may even be shareable “lessons learned” available from other units in the same organization or from earlier similar changes within the unit. |

5. Conclusion

Lean appears to offer significant improvement opportunities in the ED. The EDs implementing lean in this review reported generally favorable effects of Lean (as do studies of hospital-wide initiatives including the ED, not reviewed here). However, more work remains in understanding Lean in the ED and in health care more generally, including better assessment of Lean’s impact on patient safety and quality outcomes and on employees, as well as identifying the factors upon which Lean’s success depends. Other questions remain as well, including how Lean can best be adapted to health care, the effect of Lean on resilience, whether Lean is sustainable in the long term, whether Lean is more effective than other approaches, and the “Karen Question” (after “Karen,” who seemingly single-handedly coordinated Lean improvements at Western Pennsylvania Hospital’s presurgery unit [9]): Who shall do the Herculean task of coordinating the massive change effort that is Lean? In sum, much remains to be learned about this promising approach.

Funding:

US Agency for Healthcare Quality and Research, 5 T32 HS000083–11.

Footnotes

Presentation information: A summary of findings will be presented at poster session, AHRQ NRSA Trainees Research Conference, June 2010.

Arguably, another necessary, perhaps sufficient, indicator of Lean’s success is the efficient use of limited resources (e.g., financial, material, human resources).

Refrences

- 1.Institute of Medicine. Hospital-Based Emergency Care: At the Breaking Point. Washington, D.C.: National Academies Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Berger EA $9,000 hill to diagnose shingles? Ann Emerg Med. 2010;55:15A–17A.20116009 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kellerman AL. Crisis in the emergency department. N Engl J Med. 2006;355: 1300–1303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Smits M, Groenewegen PP, Timmermans DRM, et al. The nature and causes of unintended events reported at ten emergency departments. BMC Emerg Med. 2009;9 Available at: http://www.biomedceutral.com/1471-227X/9/16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Young TP, McClean SI. A critical look at Lean Thinking in healthcare. Qual Saf Health Care. 2008:17:382–386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.American Society for Quality. Hospitals See Benefits of Lean and Six Sigma. [press release] 2009. March 17; Available at: http:l/m.asa.org/media-room/press-releases/2009/2OO90318-hospitals. Accessed April 8,2009. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jones D, Mitchell A. Lean thinking for the NHS. London: NHS Confederation; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Womack JP, Jones DT, Roos D. The Machine That Changed the World. Revised ed. New York: Free Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Spear SJ. Fixing health care from the inside, today. Haw Bus Rev. 2005;83:78–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Toussaint J Writing the new playbook for U.S. health care: Lessons from Wisconsin. Health Aff: 2009;28:1343–1350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nelson-Peterson DL, Leppa CJ. Creating an environment for caring using lean principles of the Virginia Mason Production System. JNurs Adm. 2007;37:287–294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fillingham D Lean Healthcare: Improving the Patient’s Experience. Chichester, England: Kingsham; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cooper RG, Mohabeersingh C. Lean thinking for medical practices. Journal of Pre-Clinical and Clinical Research. 2008;2:88–89. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dl Ben-Tovim. Letters. Seeing the picture through “lean thinking”. Br Med J. 2007;334:169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Miller D Going lean in health care. Cambridge, MA: Institute for Healthcare Improvement; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bush RW. Reducing waste in US health care systems. JAMA. 2007;297:871–874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Decker WW, Stead LG. Application of lean thinking in health care: A role in emergency departments globally. Int J Emerg Med. 2008;1:161–162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Eitel DR, Rudkin SE, Malvehy MA, et al. Improving service quality by understanding emergency department flow: A white paper and position statement prepared for the American Academy of Emergency Medicine. J Emerg Med. 2010;38:70–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Horwitz LI, Meredith T, Schuur JD, et al. Dropping the baton: A qualitative analysis of failures during the transition from emergency department to inpatient care. Ann Emerg Med. 2009;53:701–710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kulkarni RG. Going lean in the emergency department: A strategy for addressing emergency department overcrowding. MedGenMed. 2007;9:58. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Smallbane S Lean thinking redesign: A weighty matter. Emerg Med Australas. 2007;19:79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vest JR, Gamm LD. A critical review of the research literature on Six Sigma, Lean and StuderGroup’s Hardwiring Excellence in the United States: The need to demonstrate and communicate the effectiveness of transformation strategies in healthcare. Implement Sci. 2009;4: 1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hughes RG. Tools and strategies for quality improvement and patient safety In: Hughes RG, ed. Patient Safety and Quality: An Evidence-Based Handbook for Nurses. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2008:1–39. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cooper RG, Mohabeersingh C. Lean thinking in a healthcare system-innovative roles. Journal of Pre-Clinical and Clinical Research. 2008;2: 110–117. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Brandao de Souza L Trends and approaches. in lean healthcare. Leadersh Health Serv. 2009;22:121–139. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Winch S, Henderson AJ. Making cars - and making health care: A - critical review. Med J Aust. 2009;191:28–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Young TP, McClean SI. Some challenges facing Lean Thinking in healthcare. Int J Qual Health Care. 2009;21:309–310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Carayon P, Schoofs Hundt A, Karsh B, et al. Work system design for patient safety: the SEIPS model. Qual Saf Health Care. 2006;15:i50–i58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Karsh B, Holden RJ, Alper SJ, et al. A human factors engineering paradigm for patient safety - designing to support the performance of the health care professional. Qual Saf Health Care. 2006;15:i59–i65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ben-Tovim DI, Dougherty ML, O’Connell TJ, et al. Patient journeys: The process of clinical redesign. Med J Aust. 2008;188:S14–S17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Holden RJ. Cognitive performance-altering effects of electronic medical records: An application of the human factors paradigm for patient safety. Cognition, Technologv & Work. inpress:doi: 10.1007/sl0111-10010-10141-10118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Conti R, Angelis J, Cooper C, et al. The effects of lean production on worker job stress. International Journal of Operations &Production Management. 2006;26: 1013–1038. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Parker SK. Longitudinal effects of Lean Production on employee outcomes and the mediating role of work characteristics. J Appl Psychol. 2003;88:620–634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jackson PR, Mullarkey S. Lean Production teams and health in garment manufacture. J Occup Health Psychol. 2000;5:231–245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Landsbergis PA. The changing organization of work and the safety and health of working people: A commentary. JOccup Environ Med. 2003;45:61–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Landsbergis PA, Cahill J, Schnall P. The impact of Lean Production and related new systems of work organization on worker health. J Occup Health Psychol. 1999;4:108–130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sprigg CA, Jackson PR. Call centers as lean service environments: Job-related strain and the mediating role ofwork design. J Occup Health Psychol. 2006;11 : 197–212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.de Treville S, Antonakis J. Could lean production job design be intrinsically motivating? Contextual, configurational, and levels-of-analysis issues. Journal of Operations Management. 2006;24:99–123. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schouteten R, Benders J. Lean production assessed by Karasek’s job demand-job control model. Economic and Industrial Democracy. 2004;25:347–373. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ohno T Toyota Production System: Beyond Large-Scale Production. New York: Productivity Press; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mehta V, Shah H. Characteristics of a work organization from a Lean perspective. Engineering Management Journal. 2005;17: 14–20. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pettersen J Defining lean production: Some conceptual and practical issues. The TQM Journal. 2009;21: 127–142. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Black J Transforming the patient care environment with lean six sigma and realistic evaluation. J Healthc Qual. 2009; 31 :29–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rodriguez KL, Burkitt KH, Sevick MA, et al. Assessing processes of care to promote timely initiation of antibiotic therapy for emergency department patients hospitalized for pneumonia. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf: 2009;35:509–518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Banerjee A, Mbamalu D, Hinchley G. The impact ofprocess re-engineering on patient throughput in emergency departments in the UK. Int J Emerg Med. 2008;1: 189–192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Travers JP, Lee FCY. Avoiding prolonged waiting time during busy periods in the emergency department: Is there a role for the senior emergency physician in triage? Eur J Emerg Med. 2006;13:342–348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Farley H, Hines D, Ross E, et al. (Abstract). A Lean-based triage redesign process improves door-to-room times and decreases number of patients at triage. Ann Emerg Med. 2009;54:S96. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Leaver C, Guttmann A, Rowe BH, et al. (Abstract). Qualitative results from an Ontario hospital patient flow improvement program pilot to improve emergency department waiting times. CJEM. 2009;11:259. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kaale RL, Vega DD, Messner K, et al. (Abstract). Time value stream mapping as a tool to measure patient flow through emergency department triage. Ann Emerg Med. 2005;46:S108. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kelly A-M, Bryant M, Cox L. (Abstract). Initiatives in redesigning emergency care to improve patient flow. Australasian Emergency Nursing Journal. 2007;10:195. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kelly A-M, Bryant M, Cox L. (Abstract). Red and blue teams: Changing processes to improve patient flow. Australasian Emergency Nursing Journal. 2007;10:226. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Massucci JL, Farley H, Laskowski Jones L, et al. (Abstract). Reduction in emergency department fast track length of stay. Ann Emerg Med. 2008;52:S111. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Munro PT, Gillespie C, Begbie K, et al. (Abstract). Resource-neutral performance improvement in an urban general hospital emergency department. Ann Emerg Med. 2008;51:541. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Retallick N. (Abstract). Patient process improvements in the emergency department. Australasian Emergency Nursing Journal. 2007;10:221–222. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Schuur JD, Collins D, Smith A, et al. (Abstract). Use of Lean techniques to simplify admission procedures and decreased ED process time. Ann Emerg Med. 2007;50:S90. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Stratton R, Knight A. (Abstract). Utilising buffer management to manage patient flow 16th International Annual EurOMA Conference; 2009; Goteborg, Sweden; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Weinstock M How one hospital slashed ED waits. Hosp Health Netw. 2007;81:22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Foster R Windsor Regional Hospital emergency department revolutionized. Hospital News. 2007;20:1,8. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Stuenkel K, Faulkner T. A community hospital’s journey into lean six sigma. Front Health Sew Manage. 2009;26:5–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Burkitt KH, Mor MK, Jain R, et al. Toyota Production System quality improvement initiative improves perioperative antibiotic therapy. Am J Manag Care. 2009;15:633–642. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Stapleton FB, Hendricks J, Hagan P, et al. Modifying the Toyota Production System for continuous performance improvement in an academic children’s hospital. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2009;56:799–813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Fine BA, Golden B, Hannam R, et al. Leading Lean: A Canadian healthcare leader’s guide. Healthc Q. 2009;12:32–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kim CS, Spahlinger DA, Kin JM, et al. Implementation of lean thinking: One health system’s journey. Jt Comm JQual Patient Saf. 2009;35:406–413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Van den Heuvel J, Does RJMM, de Koning H. Lean Six Sigma in a hospital. International Journal of Six Sigma and Competitive Advantage. 2006;2:377–388. [Google Scholar]

- 65.MacLeod H, Bell B, Deane K, et al. Creating sustained improvements in patient access and flow: Experiences from three Ontario healthcare institutions. Healthc Q. 2008;11:38–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Slunecka F, Farris D. Lean principles provide opportunities for Catholic health care organizations. Health Prog. 2008;89:46–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Fillingham D Can lean save lives? Leadersh Health Serv. 2007;20:231–241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Isaacs AA, Hellenberg DA. Implementing a structured triage system at a community health centre using Kaizen. South African Family Practice. 2009;51 :496–501. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Al Darrab A, Fernandes CMB, Velianou J, et al. Application of Lean Six Sigma for patients presenting with ST-elevation myocardial infarction: The Hamilton Health Sciences experience. Healthc Q. 2006;9:56–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Ben-Tovim DI, Bassham JE, Bolch D, et al. Lean thinking across a hospital: redesigning care at the Flinders Medical Centre. Aust Health Rev. 2007;31: 10–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Ben-Tovim DI, Bassham JE, Bennett DM, et al. Redesigning care at the Flinders Medical Centre: Clinical process redesign using “lean thinking”. Medical Journal ofAustralia. 2008;188:S27–S31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.King DL, Ben-Tovim DI, Bassham J. Redesigning emergency department patient flows: Application of Lean Thinking to health care. Emerg MedAustralas. 2006;18:391–397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Dickson EW, Anguelov Z, Bott P, et al. The sustainable improvement of patient flow in an emergency treatment centre using Lean. International Journal of Six Sigma and Competitive Advantage. 2008;4:289–304. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Dickson EW, Singh S, Cheung DS, et al. Application of lean manufacturing techniques in the emergency department. J Emerg Med. 2009;37:177–182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Dickson EW, Anguelov Z, Vetterick D, et al. Use of lean in the emergency department: A case series of4 hospitals. Ann Emerg Med. 2009;54:504–510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Eller A Rapid assessment and disposition: Applying LEAN in the emergency department. J Healthc Qual. 2009;31: 17–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Ieraci S, Digiusto E, Sonntag P, et al. Streaming by case complexity: Evaluation of a model for emergency department Fast Track. Emerg Med Australas. 2008;20:241–249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Jacobson GH, McCoin NS, Lescallette R, et al. Kaizen: A method of process improvement in the emergency department. Acad Emerg Med. 2009;16:1341–1349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Kelly A-M, Bryant M, Cox L, et al. Improving emergency department efficiency by patient streaming to outcomes-based teams. Aust Health Rev. 2007; 31: 16–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Kulkarni RG. A reader and author respond to “ Going Lean in the emergency department: A strategy for addressing emergency department overcrowding”. Medscape J Med. 2008;10:25. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Ng D, Vail G, Thomas S, et al. Applying the Lean principles of the Toyota Production System to reduce wait times in the emergency department. CJEM. 2010;12:50–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Parks JK, Klein J, Frankel HL, et al. Dissecting delays in trauma care using corporate lean six sigma methodology. J Trauma. 2008;65:1098–1105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Schooley J No longer waiting for answers: Hospital’s process changes inspire new workplace culture. Qual Prog. 2008;41:34–39. [Google Scholar]

- 84.Stephens-Lee C Work flow analysis of admitted patients. Canadian Journal of Nursing Informatics. 2006;1 Available at: http://cnia.ca/journal/volume1_no2e.html [Google Scholar]

- 85.Woodward GA, Godt MG, Fisher K, et al. Children’s hospital and regional medical center emergency department patient flow-Rapid process improvement (RPI) In: Chalice R, ed. Improving Healthcare Quality Using Toyota Lean Production Methods: 46 Steps for Improvement. 2nd ed. Milwaukee, WI: Quality Press; 2007:145–150. [Google Scholar]

- 86.Furman C Implementing a patient safety alert system(TM). Nurs Econ. 2005;23:42–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.O’Brien D, Williams A, Blondell K, et al. Impact of streaming “fast track” emergency department patients. Aust Health Rev. 2006;30:525–532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Ballé M, Régnier A. Lean as a learning system in a hospital ward. Leadersh Health Serv. 2007;20:33–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Woods DD. Escaping failures of foresight. Saf Sci. 2009;47:498–501. [Google Scholar]

- 90.Hollnagel E, Woods DD, Leveson N, eds. Resilience Engineering: Concepts and Precepts. Aldershot, UK: Ashgate; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 91.Kulstad EB, Sikka R, Sweis RT, et al. ED overcrowding is associated with an increased frequency of medication errors. Am J Emerg Med. 2010;28:304–309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Gamm L, Kash B, Bolin J. Organizational technologies for transforming care: Measures and strategies for pursuit of IOM quality aims. J Ambul Care Manage. 2007;30:29l–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Joosten T, Bongers I, Janssen R. Application of lean thinking to health care: Issues and observations. Int J Qual Health Care. 2009;21:341–347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Brown GD, O’Rourke D. Lean manufacturing comes to China: A case study of its impact on workplace health and safety. Int J Occup Environ Health. 2007;13:249–257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Björkman T The Rationalisation Movement in perspective and some ergonomic implications. Appl Ergon. 1996;27:111–117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Koukoulaki T New trends in work environment - New effects on safety Saf Sci. in press:doi: 10.1016/j.ssci.2009.1004.1003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Babson S, ed. Lean Work: Empowerment and Exploitation in the Global Auto Industry. Detroit: Wayne State University Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 98.Fields DL. Taking the Measure of Work: A Guide to Validated Scales for Organizational Research and Diagnosis. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 99.National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health. Organization of Work: Measurement Tools for Research and Practice. 2008; Available at: http://www.cdc.govlniosWtopics/workorg/tools/default.html Accessed April 1,2010. [Google Scholar]

- 100.Lean Näslund D., six sigma and lean sigma: Fads or real process improvement methods? Business Process Managenlent Journal. 2008;14:269–287. [Google Scholar]