Phototropism is enhanced by seedling de-etiolation and is achieved by a molecular rheostat that fine-tunes the phosphorylation and localization status of the phototropic signaling component, NPH3.

Abstract

Phototropin (phot) receptor kinases play important roles in promoting plant growth by controlling light-capturing processes, such as phototropism. Phototropism is mediated through the action of NON-PHOTOTROPIC HYPOCOTYL3 (NPH3), which is dephosphorylated following phot activation. However, the functional significance of this early signaling event remains unclear. Here, we show that the onset of phototropism in dark-grown (etiolated) seedlings of Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana) and tomato (Solanum lycopersicum) is enhanced by greening (deetiolation). Red and blue light were equally effective in promoting phototropism in Arabidopsis, consistent with our observations that deetiolation by phytochrome or cryptochrome was sufficient to enhance phototropism. Increased responsiveness did not result from an enhanced sensitivity to the phytohormone auxin, nor does it involve the phot-interacting protein, ROOT PHOTOTROPISM2. Instead, deetiolated seedlings showed attenuated levels of NPH3 dephosphorylation and diminished relocalization of NPH3 from the plasma membrane during phototropism. Likewise, etiolated seedlings that lack the PHYTOCHROME-INTERACTING FACTORS (PIFs) PIF1, PIF3, PIF4, and PIF5 displayed reduced NPH3 dephosphorylation and enhanced phototropism, consistent with their constitutive photomorphogenic phenotype in darkness. Phototropic enhancement could also be achieved in etiolated seedlings by lowering the light intensity to diminish NPH3 dephosphorylation. Thus, phototropism is enhanced following deetiolation through the modulation of a phosphorylation rheostat, which in turn sustains the activity of NPH3. We propose that this dynamic mode of regulation enables young seedlings to maximize their establishment under changing light conditions, depending on their photoautotrophic capacity.

Plants orient the growth of their stems toward light, a response known as phototropism. Phototropism is induced by UV/blue light and is controlled by two phototropin (phot) receptor kinases, phot1 and phot2 (Fankhauser and Christie, 2015). Phot1 is the primary phototropic receptor and functions over a wide range of fluence rates, whereas phot2 activity predominates at higher light intensities (Sakai et al., 2001). It is widely accepted that phototropism results from differential cell growth across the stem brought about by an asymmetric accumulation of the phytohormone auxin (Christie and Murphy, 2013; Liscum et al., 2014). How this lateral auxin gradient forms in response to phot activation is still not understood (Fankhauser and Christie, 2015). However, members of the NON-PHOTOTROPIC HYPOCOTYL3 (NPH3)/ROOT PHOTOTROPISM2 (RPT2)-like (NRL) family are known to play important roles (Christie et al., 2018).

Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana) mutants deficient in the founding NRL member, NPH3, fail to show phototropism under a variety of different light conditions (Sakai and Haga, 2012; Liscum et al., 2014; Fankhauser and Christie, 2015). NPH3 appears to be instrumental in establishing the lateral auxin gradients required for phototropic growth (Haga et al., 2005, 2015). Its primary amino acid structure can be separated into three regions based on sequence conservation with other NRL proteins: a BTB (bric-a-brac, tramtrack, and broad complex) domain at the N terminus, an NPH3 domain, and a C-terminal coiled-coil domain (Liscum et al., 2014; Christie et al., 2018). NPH3 is reported to form part of the CULLIN3 RING E3 UBIQUITIN LIGASE complex that ubiquitinates phot1 (Roberts et al., 2011; Deng et al., 2014). Polyubiquitination of phot1 is associated with its degradation in response to prolonged irradiation, whereas its monoubiquitination is proposed to initiate the internalization of phot1 from the plasma membrane at low light intensities (Roberts et al., 2011).

NPH3, like the phots, is associated with the plasma membrane in Arabidopsis (Haga et al., 2015). The C-terminal region, including the coiled-coil domain, appears to help localize NPH3 to the plasma membrane (Inoue et al., 2008b), where it interacts with phot1 (Haga et al., 2015). This interaction is transiently disrupted upon irradiation and is correlated with the phosphorylation status of NPH3 (Haga et al., 2015). NPH3 is phosphorylated in darkness but becomes rapidly dephosphorylated when phot1 is activated by light (Pedmale and Liscum, 2007). The phosphatase responsible for NPH3 dephosphorylation remains unknown, but this process appears to be tissue/cell autonomous (Sullivan et al., 2016b). Light not only alters the phosphorylation status of NPH3 but also leads to dynamic changes in its subcellular localization. NPH3 is rapidly internalized into aggregates upon phot1 activation (Haga et al., 2015). The formation of these aggregates is reversible in darkness (Haga et al., 2015), as is the rephosphorylation of NPH3 (Pedmale and Liscum, 2007). However, the functional significance of these changes to NHP3’s phosphorylation status and localization is not fully understood.

RPT2, the second founding member of the NRL family, appears to play a role in sustaining phot1-NPH3 interactions at higher light intensities. RPT2 was first identified from a genetic screen for mutants impaired in root phototropism (Okada and Shimura, 1992; Sakai et al., 2000) and is reported to interact with both phot1 and NPH3 (Inada et al., 2004; Sullivan et al., 2009). Mutants that lack RPT2 exhibit normal phototropism under very low fluence rates of unilateral blue light but show impaired curvature at higher light intensities (Haga et al., 2015). Thus, RPT2 is believed to be important for promoting efficient phototropism under brighter light conditions (Haga et al., 2015). This proposed function of RPT2 correlates well with its expression profile, which increases upon irradiation in a fluence rate-dependent manner (Inada et al., 2004; Tsuchida-Mayama et al., 2008; Haga et al., 2015). Nevertheless, how RPT2 functions alongside NPH3 to generate the lateral auxin gradient required for phototropic growth remains poorly understood. The formation of this gradient appears to involve the activity of auxin efflux carriers from both the PIN-FORMED (PIN) and ATP-BINDING CASSETTE B families (Christie et al., 2011; Willige et al., 2013). PHYTOCHROME KINASE SUBSTRATE proteins (PKS1–PKS4) are also known to play a role in phototropism by influencing auxin transport or auxin-regulated gene expression (Kami et al., 2014).

Phototropism in both monocotyledons and dicotyledons has been studied extensively using dark-grown (etiolated) seedlings (Christie and Murphy, 2013). Other photoreceptors, in addition to the phots, modulate phototropic growth in etiolated seedlings when activated. For instance, the preexposure of seedlings to red light accelerates the onset of phototropism in many plant species, including Arabidopsis, through the action of phytochrome A (phyA; Sakai and Haga, 2012). This effect of phyA on phototropism is restricted to low fluence rates of unilateral blue light and appears to depend on signals that originate in tissues other than the epidermis (Kirchenbauer et al., 2016; Sullivan et al., 2016b). The study of phototropism in green (deetiolated) seedlings has received less attention by comparison (Christie and Murphy, 2013) but has gathered renewed interest in recent years (Christie et al., 2011; Goyal et al., 2013; Hohm et al., 2014; Preuten et al., 2015; Sullivan et al., 2016b).

The aim of this study was to determine whether deetiolation can modulate phototropic responsiveness and to identify the underlying mechanism(s) by which this is achieved. Early work has shown that the hypocotyl curvature responses of cress (Lepidium sativum), lettuce (Lactuca sativa), mustard (Brassica spp.), and radish (Raphanus sativus) are enhanced in deetiolated seedlings compared with etiolated seedlings (Hart and Macdonald, 1981; Gordon et al., 1982). We show that this also holds true for Arabidopsis and for other dicots and that this enhancement is underpinned by a molecular rheostat that fine-tunes the phosphorylation status and subcellular localization of NPH3, independent of the action of RPT2.

RESULTS

Deetiolation Enhances the Onset of Phototropic Growth

Time-lapse imaging of free-standing seedlings germinated on a horizontal surface of moistened silicon oxide provides a more reliable means to measure phototropic growth compared with measurements that are conducted on seedlings grown on vertical agar plates (Sullivan et al., 2016a). We therefore used this approach to study the impact of deetiolation on Arabidopsis phototropism.

Etiolated seedlings were grown in darkness for 3 d prior to phototropic stimulation with a low fluence rate of unilateral blue light (0.5 µmol m−2 s−1). An identical growth regime was used for deetiolated seedlings, except that an 8-h irradiation period with white light (80 µmol m−2 s−1) was introduced after 2 d of growth (Fig. 1A). Etiolated seedlings exhibited a lag time of approximately 1 h before a curvature response was observed (Fig. 1A). The onset of phototropism in deetiolated seedlings occurred more rapidly and was initiated within 30 min. Consequently, the curvature of deetiolated seedlings reached saturation sooner than in etiolated seedlings and at a greater magnitude. A similar enhancement effect of deetiolation on phototropism was observed for tomato (Solanum lycopersicum) seedlings (Supplemental Fig. S1). As reported previously (Christie et al., 2011), the region of hypocotyl curvature is located more basally in deetiolated seedlings compared with etiolated seedlings (Fig. 1B). These differences coincide with the growth capacities of etiolated and deetiolated hypocotyls. For etiolated seedlings, the elongation zone resides within the hypocotyl apex, whereas the largest growth capacity in deetiolated seedlings is located lower in the hypocotyl (Gendreau et al., 1997).

Figure 1.

Deetiolation enhances phototropism and alters the position of hypocotyl curvature. A, Top, Experimental design for analyzing phototropism in etiolated and deetiolated seedlings. Etiolated seedlings were grown in darkness for 3 d. For deetiolated seedlings, deetiolation was induced in 2-d-old, dark-grown seedlings with an 8-h white light treatment (80 µmol m−2 s−1), followed by a 16-h dark adaptation. Three-day-old etiolated and deetiolated seedlings were placed into unilateral blue light to analyze hypocotyl phototropism. Bottom, Phototropism of etiolated and deetiolated seedlings irradiated with 0.5 µmol m−2 s−1 unilateral blue light. Hypocotyl curvatures (θ) were measured every 10 min for 4 h, and each value is the mean ± se of 20 seedlings. B, Top, Positions of hypocotyl curvature in etiolated (Et) and deetiolated (De-et) wild-type seedlings. Composite images of etiolated (left) and deetiolated (right) seedling are shown at 0, 20, 40, and 60 min after commencement of curvature. Arrowheads indicate the positions of hypocotyl curvature. Bottom, Quantification of the position of hypocotyl curvature as measured from the base of the hypocotyl (with 0 being the closest and 1 the farthest). The recorded position was divided by total hypocotyl length to give the relative position of curvature. Values are means ± se of 20 seedlings.

Deetiolation by Phytochrome or Cryptochrome Is Sufficient to Enhance Phototropism

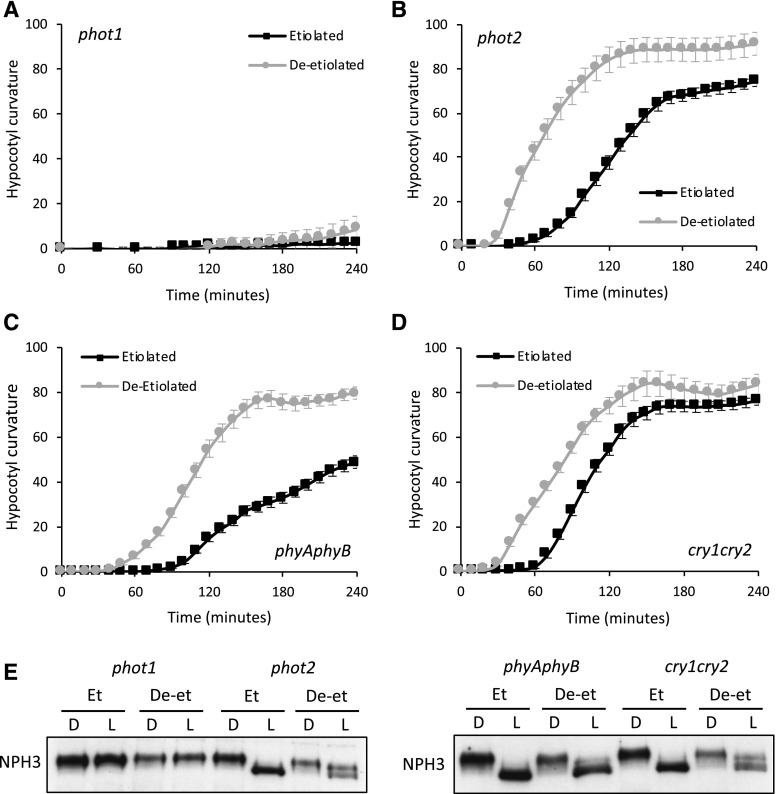

Our examination of the Arabidopsis phot1 single mutant demonstrated that phot1 was responsible for mediating hypocotyl phototropism to 0.5 µmol m−2 s−1 in both etiolated and deetiolated seedlings (Fig. 2A). Since phot2 protein levels are known to increase in response to irradiation (Christie and Murphy, 2013), we rationalized that phot2 could be responsible for mediating the phototropic enhancement in deetiolated seedlings. Indeed, phot2 protein levels were higher in deetiolated versus etiolated seedlings, whereas the abundance of phot1 was reduced (Supplemental Fig. S2). However, mutants that lack phot2 still showed enhanced phototropism post greening (Fig. 2B), indicating that phot2 is not required to mediate this process.

Figure 2.

Phototropic responses and NPH3 phosphorylation status in etiolated and deetiolated seedlings of photoreceptor mutants. A to D, Phototropism of etiolated and deetiolated phot1 (A), phot2 (B), phyA phyB (C), and cry1 cry2 (D) mutant seedlings irradiated with 0.5 µmol m−2 s−1 unilateral blue light. Hypocotyl curvatures were measured every 10 min for 4 h, and each value is the mean ± se of 17 to 20 seedlings. E, Immunoblot analysis of total protein extracts from etiolated (Et) and deetiolated (De-et) phot1, phot2, phyA phyB, and cry1 cry2 mutant seedlings, maintained in darkness (D) or irradiated with 0.5 µmol m−2 s−1 unilateral blue light for 60 min (L). Protein extracts were probed with anti-NPH3 antibody.

A brief (∼15 min) pretreatment with red or blue light is known to enhance the curvature response of etiolated seedlings through the action of phyA (Kami et al., 2012; Sullivan et al., 2016a). We therefore examined whether deetiolation under red or blue light was sufficient to enhance phototropism. Our results showed that red, blue, or white light were equally effective in promoting phototropic enhancement (Supplemental Fig. S3). Thus, we examined whether deetiolation by phytochrome or cryptochrome blue light receptors could enhance phototropism. Etiolated seedlings that lack phyA and phyB exhibited a reduced phototropic response (Fig. 2C), compared with wild-type seedlings (Fig. 1A). However, these results are consistent with previous reports that phyA is necessary for the progression of normal phototropism in Arabidopsis (Whippo and Hangarter, 2004; Sullivan et al., 2016a). Deetiolation was still able to elicit phototropic enhancement in the phyA phyB mutant (Fig. 2C), indicating that this process is not solely dependent on the actions of phyA and phyB. Similar results were also obtained for cryptochrome1 (cry1) cry2 mutants (Fig. 2D). Together, these findings demonstrate that deetiolation by either phytochrome or cryptochrome is sufficient to enhance phototropism.

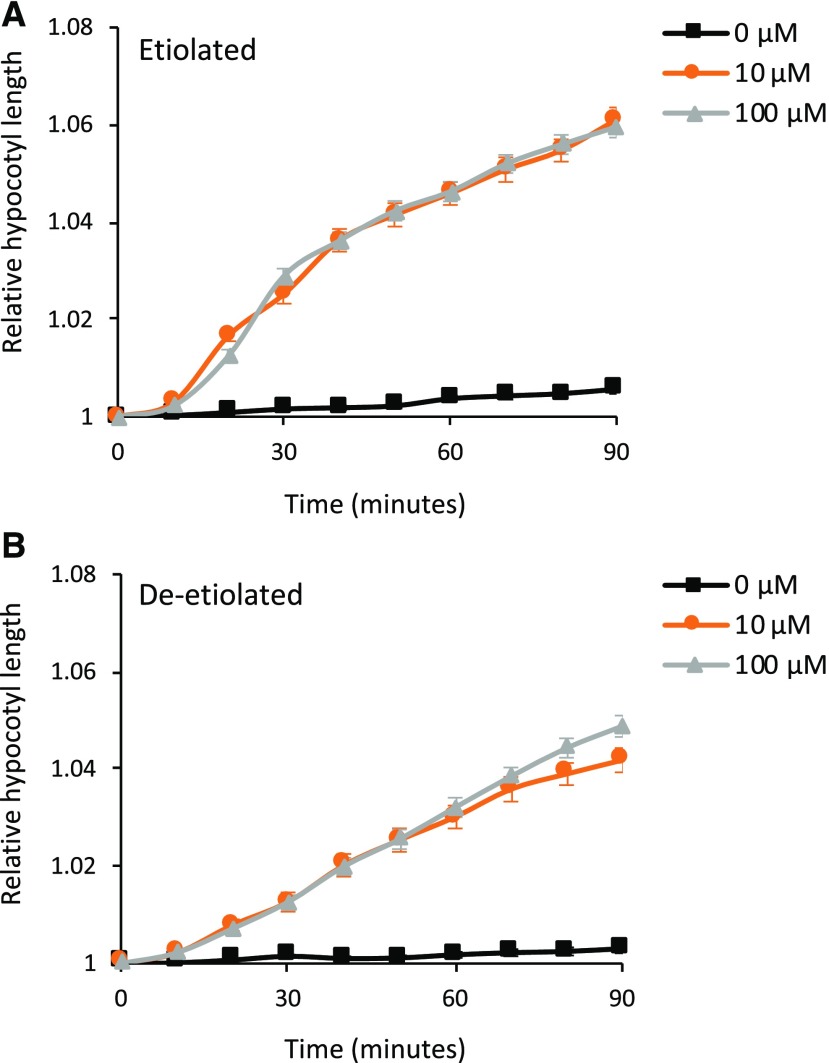

Deetiolated Hypocotyls Do Not Exhibit Increased Sensitivity to Auxin

Lateral auxin accumulation on the shaded side of the hypocotyl is required to promote differential cell elongation (Fankhauser and Christie, 2015). We therefore considered whether deetiolated seedlings exhibit a greater sensitivity to auxin. To determine this, we studied the impact of auxin using a growth assay on hypocotyl sections, as reported previously (Takahashi et al., 2012). Hypocotyl sections were isolated from etiolated and deetiolated seedlings, using a red safe light, and were placed onto agar medium and returned to darkness for 1 to 1.5 h to deplete the endogenous auxin pool. Consequently, little, if any, growth was subsequently detected in these auxin-depleted hypocotyls (Fig. 3). When these hypocotyl sections were transferred to a medium containing the natural auxin indole-3-actic acid (IAA), stem elongation occurred after a lag time of ∼10 min. Treatment with 10 or 100 µm IAA was equally effective at promoting growth in both etiolated (Fig. 3A) and deetiolated (Fig. 3B) hypocotyls. However, deetiolated hypocotyls were notably less responsive to the IAA application and exhibited a lower degree of auxin-induced elongation compared with the etiolated hypocotyls. We therefore conclude that the enhanced phototropic response of deetiolated seedlings is not a consequence of increased sensitivity to auxin. It is also reported that the growth rate of etiolated seedlings is higher than that of deetiolated seedlings (Hart et al., 1982). Therefore, it is unlikely that differences in growth rates account for the enhanced phototropism in etiolated seedlings.

Figure 3.

Auxin-induced elongation of hypocotyl segments of etiolated and deetiolated seedlings. Elongation is shown for 4-mm apical hypocotyl segments prepared from etiolated (A) or deetiolated (B) seedlings. Hypocotyl segments were placed on medium containing 0, 10, or 100 µm IAA, and hypocotyl segment lengths were measured every 10 min for 90 min. Each value is the mean ± se of 30 seedlings.

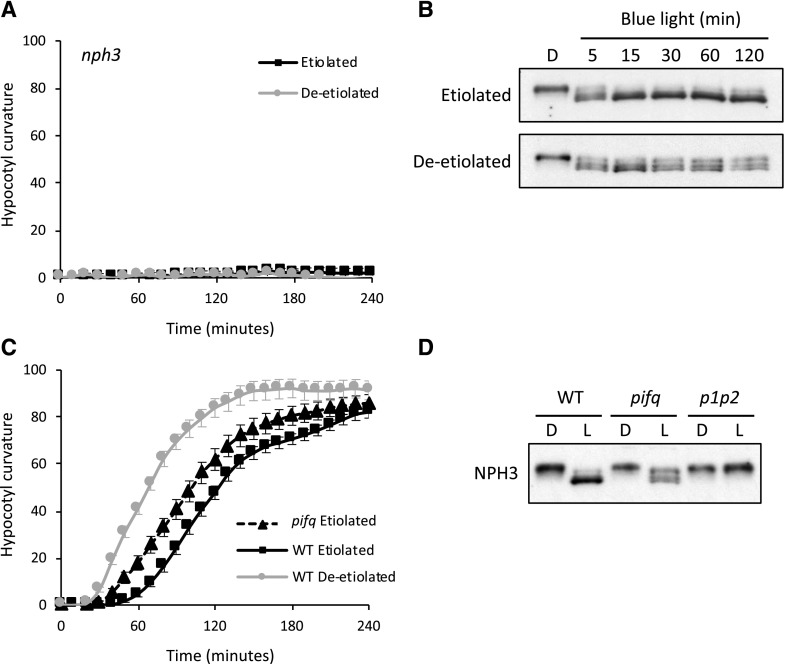

Deetiolation Alleviates NPH3 Dephosphorylation

We next examined whether aspects of phot1 signaling were altered in deetiolated seedlings that could account for the seedlings’ enhanced responsiveness to light. NPH3 is an early signaling component that plays a key role in establishing phototropic curvature (Liscum et al., 2014; Christie et al., 2018). Phototropic measurements performed on the nph3 mutant demonstrated that NPH3 is necessary to mediate hypocotyl curvature in both etiolated and deetiolated seedlings (Fig. 4A).

Figure 4.

NPH3 functionality and phosphorylation status in etiolated and deetiolated seedlings. A, Phototropism of etiolated and deetiolated nph3 mutant seedlings irradiated with 0.5 µmol m−2 s−1 unilateral blue light. Hypocotyl curvatures were measured every 10 min for 4 h, and each value is the mean ± se of 20 seedlings. B, NPH3 phosphorylation status in etiolated and deetiolated seedlings during irradiation with blue light. Immunoblot analysis is shown for total protein extracts from etiolated and deetiolated wild-type seedlings maintained in darkness (D) or irradiated with 0.5 µmol m−2 s−1 unilateral blue light for 5, 15, 30, 60, or 120 min. Protein extracts were probed with anti-NPH3 antibody. C, Phototropism of etiolated pifq mutant seedlings irradiated with 0.5 µmol m−2 s−1 unilateral blue light. Hypocotyl curvatures were measured every 10 min for 4 h, and each value is the mean ± se of 20 seedlings. Phototropic responses of etiolated and deetiolated wild-type (WT) seedlings are also shown. D, Immunoblot analysis of total protein extracts from etiolated wild-type, pifq quadruple mutant, and phot1 phot2 (p1p2) double mutant seedlings maintained in darkness (D) or irradiated with 0.5 µmol m−2 s−1 unilateral blue light for 60 min (L). Protein extracts were probed with anti-NPH3 antibody.

The activation of phot1 leads to a rapid dephosphorylation of NPH3, which can be detected by immunoblotting owing to its enhanced electrophoretic mobility (Fig. 4B). Light-induced dephosphorylation was still apparent in deetiolated seedlings but occurred to a much lesser degree (Fig. 4B), with multiple phosphorylation products remaining over the 2-h irradiation period with 0.5 µmol m−2 s−1. A similar effect on NPH3 dephosphorylation was also observed in etiolated seedlings of the pifq mutant, which lacks the four PHYTOCHROME-INTERACTING FACTORS (PIFs) PIF1, PIF3, PIF4, and PIF5 (Fig. 4D). This mutant is known to display a constitutive photomorphogenic phenotype in darkness (Leivar et al., 2008) and is also impaired in gravity sensing (Kim et al., 2011). Repositioning of pifq seedlings into a vertical position was therefore necessary to assess their phototropic responsiveness. The phototropic response of etiolated pifq seedlings was enhanced relative to wild-type etiolated seedlings (Fig. 4C). These data provide further evidence that deetiolation enhances the onset of phototropism by diminishing NPH3 dephosphorylation. Further support for this conclusion comes from the observation that reduced NPH3 dephosphorylation was evident in deetiolated seedlings of phot2, phyA phyB, and cry1 cry2 mutants (Fig. 2E), which still showed enhanced phototropism upon deetiolation (Fig. 2, B–D).

To discriminate whether the enhanced phototropism observed in stems of etiolated pifq mutant seedlings was from reduced gravity sensing, we examined the phototropic responses of the pgm1 mutant, which lacks PHOSPHOGLUCOMUTASE1. Starchless mutants such as pgm1 are defective in gravity sensing and show enhanced root phototropism (Vitha et al., 2000). However, phototropic enhancement was still apparent in pgm1 mutants following deetiolation (Supplemental Fig. S4A), as was reduced NPH3 dephosphorylation (Supplemental Fig. S4B). These data therefore indicate that the impact of deetiolation on NPH3 phosphorylation status and phototropism does not depend on changes in gravity sensing.

Deetiolation Reduces NPH3 Aggregate Formation

Reduced dephosphorylation of NPH3 in response to deetiolation was also apparent in transgenic seedlings expressing NPH3 as a C-terminal translational fusion to GFP (Supplemental Fig. S5), although the electrophoretic mobility shift was less obvious in this line, presumably owing to the presence of the GFP tag. GFP-NPH3 expression in these lines was driven by the native NPH3 promoter. GFP-NPH3 was fully functional in restoring phototropism in the nph3 mutant background, including the phototropic enhancement in response to deetiolation (Supplemental Fig. S5).

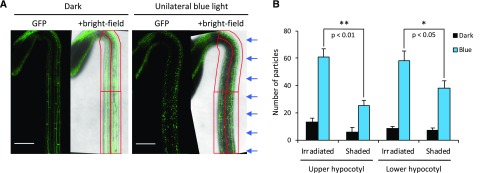

GFP-NPH3 is primarily localized at the plasma membrane in darkness but is rapidly (within minutes) internalized into aggregates upon blue light treatment (Supplemental Movie S1). The formation of these aggregates depends on phot1 activity (Haga et al., 2015). Indeed, unilateral irradiation resulted in differential NPH3 aggregate formation across the etiolated hypocotyl (Fig. 5). These findings are in agreement with the proposal that a gradient of photoreceptor activation across the hypocotyl is necessary to drive phototropic growth (Christie and Murphy, 2013). The difference in GFP-NPH3 aggregate formation between the irradiated and the shaded sides was more significant in the upper hypocotyl than in the lower hypocotyl (Fig. 5), coinciding with this region being the site of phototropic growth (Preuten et al., 2013; Yamamoto et al., 2014).

Figure 5.

Effects of unilateral blue light irradiation on GFP-NPH3 localization across the hypocotyl. A, Confocal images of etiolated NPH3::GFP-NPH3#1 seedlings maintained in darkness (left) or irradiated with 0.5 µmol m−2 s−1 unilateral blue light for 60 min (right). Arrows indicate the direction of blue light. Hypocotyl images were divided into irradiated and shaded sides, and then into upper and lower halves, to give four regions of interest, depicted in red, which were used to analyze NPH3 localization. Bars = 200 µm. B, Quantification of the effects of unilateral blue light irradiation on GFP-NPH3 localization across the hypocotyl. The number of GFP particles was counted in each of the four regions of interest in etiolated seedlings expressing NPH3::GFP-NPH3 maintained in darkness (Dark) or irradiated with 0.5 µmol m−2 s−1 unilateral blue light for 60 min (Blue). Each value is the mean ± se of 12 seedlings. Asterisks indicate significant differences between the number of GFP particles in the irradiated and shaded hypocotyl sides (*, P < 0.05 and **, P < 0.01, Student’s t test).

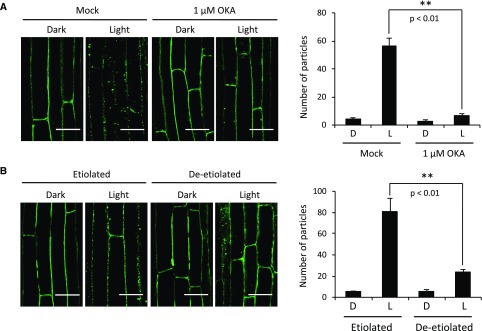

The kinetics for NPH3 dephosphorylation correlate closely with the time scale described for the changes in NPH3 relocalization (Haga et al., 2015). The treatment of etiolated hypocotyl sections with the protein phosphatase inhibitor okadaic acid (OKA) diminished the formation of NPH3 aggregates (Fig. 6A). The OKA treatment was equally effective in inhibiting the light-induced dephosphorylation of NPH3 (Supplemental Fig. S6). Thus, GFP aggregate formation is coupled to NPH3 dephosphorylation. With this in mind, we rationalized that deetiolated seedlings, which retain a sustained level of phosphorylated NPH3 following phototropic stimulation, should exhibit a diminished GFP-NPH3 aggregate formation. Confocal microscopy confirmed that aggregate formation is markedly reduced in deetiolated seedlings compared with etiolated seedlings (Fig. 6B).

Figure 6.

Effects of OKA and deetiolation on blue light-induced GFP-NPH3 relocalization. A, Confocal images of hypocotyl cells of etiolated seedlings expressing NPH3::GFP-NPH3#1 pretreated with 1 µm OKA or solvent-only control (Mock) and maintained in darkness (D) or irradiated with 0.5 µmol m−2 s−1 blue light for 60 min (L). B, Comparison of blue light-induced GFP-NPH3 relocalization in etiolated and deetiolated seedlings. Confocal images show hypocotyl cells of etiolated and deetiolated seedlings expressing NPH3::GFP-NPH3#1 maintained in darkness or irradiated with 0.5 µmol m−2 s−1 blue light for 60 min. The quantification of GFP particles is shown at right. The number of GFP particles was counted in confocal images of hypocotyl cells. Each value is the mean ± se of 12 seedlings, and asterisks indicate significant differences in the number of GFP particles between the indicated samples (**, P < 0.01, Student’s t test). Bars = 50 µm.

Deetiolation Enhances Phototropism by Factors Other Than RPT2

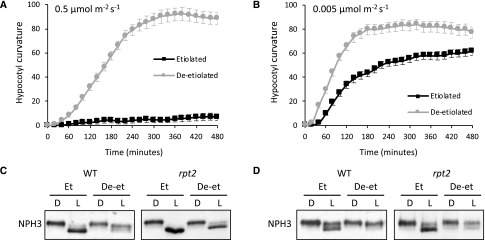

The NRL family member RPT2 appears to play a role in sustaining phot1-NPH3 interactions at higher light intensities and has been recently reported to have a role in modulating the phosphorylation and localization status of NPH3 (Haga et al., 2015). RPT2 transcript abundance is increased 20-fold in response to deetiolation (Supplemental Fig. S7). We therefore investigated whether RPT2 contributed to enhancing phototropism in deetiolated seedlings. As reported previously (Haga et al., 2015), etiolated seedlings of the rpt2 mutant showed impaired hypocotyl phototropism at 0.5 μmol m−2 s−1 blue light (Fig. 7A). By contrast, deetiolated rpt2 seedlings exhibited a robust response (Fig. 7A), indicating that RPT2 is not required for phototropism post deetiolation.

Figure 7.

Deetiolated rpt2 mutant seedlings show enhanced phototropism and reduced dephosphorylation of NPH3. A and B, Phototropism of etiolated and deetiolated rpt2 mutant seedlings irradiated with 0.5 µmol m−2 s−1 (A) or 0.005 µmol m−2 s−1 (B) unilateral blue light. Hypocotyl curvatures were measured every 20 min for 8 h, and each value is the mean ± se of 20 seedlings. C and D, NPH3 phosphorylation status in etiolated (Et) and deetiolated (De-et) seedlings irradiated with 0.5 µmol m−2 s−1 (C) or 0.005 µmol m−2 s−1 (D) unilateral blue light. Immunoblot analysis is shown for total protein extracts from etiolated and deetiolated rpt2 single mutant and wild-type (WT) seedlings maintained in darkness (D) or irradiated with blue light for 60 min (L). Protein extracts were probed with anti-NPH3 antibody.

The phototropic response of the rpt2 mutant is indistinguishable from that of wild-type etiolated seedlings at blue light intensities of 0.01 μmol m−2 s−1 or less (Haga et al., 2015). At lower light intensities (0.005 μmol m−2 s−1), phototropic enhancement in response to deetiolation was clearly apparent in both wild-type seedlings (Supplemental Fig. S8) and the rpt2 mutant (Fig. 7B). Sustained levels of NPH3 phosphorylation were also detected in deetiolated seedlings of the rpt2 mutant, irrespective of whether 0.5 (Fig. 7C) or 0.005 μmol m−2 s−1 (Fig. 7D) was used for phototropic stimulation. These findings demonstrate that the reduction in NPH3 dephosphorylation and the promotion of phototropism in green seedlings occur independently of RPT2.

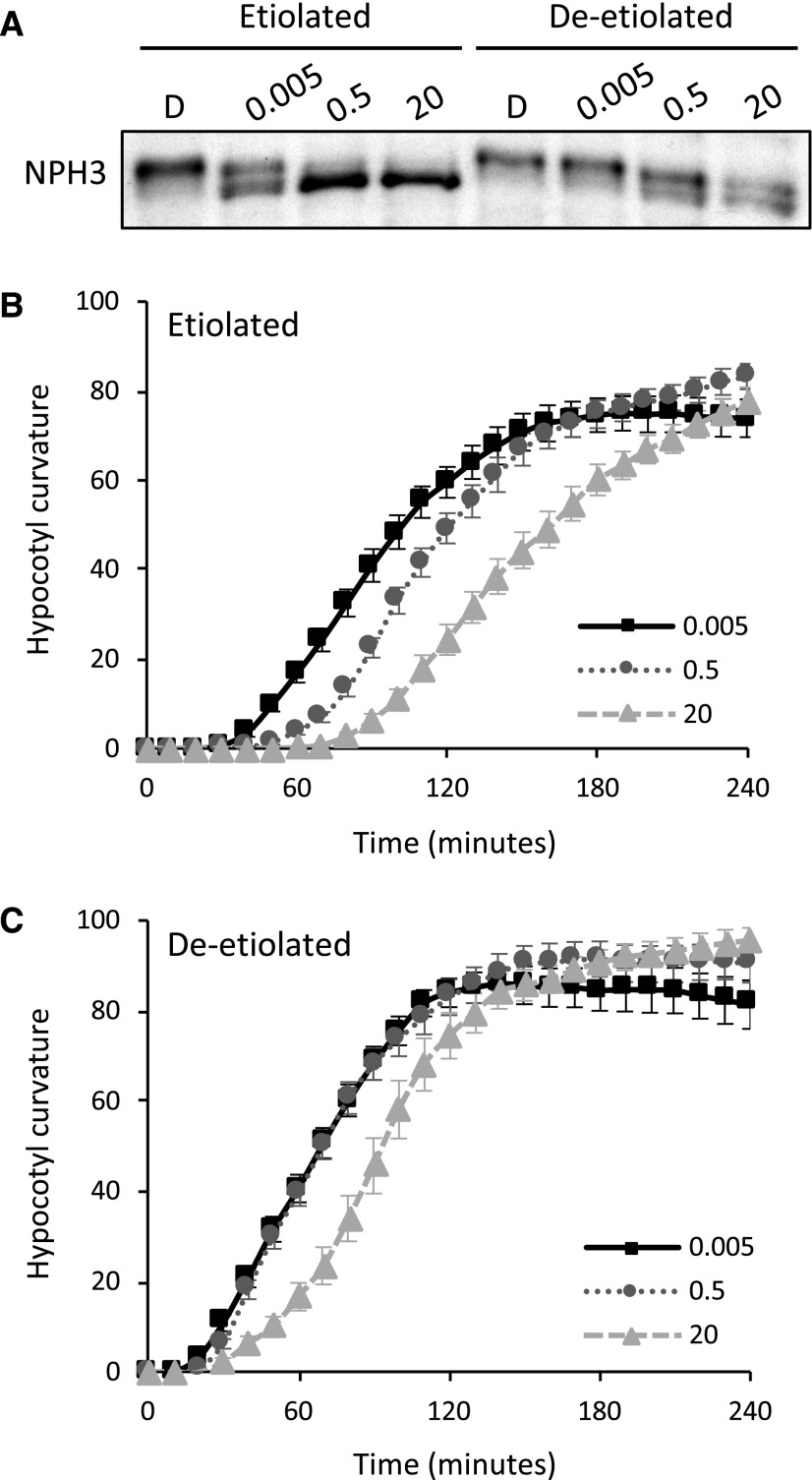

Reducing NPH3 Dephosphorylation in Etiolated Seedlings Enhances Phototropism Onset

Since our findings suggest that NPH3’s mode of action in initiating phototropism is fine-tuned by modulating its phosphorylation status, we rationalized that if we could diminish NPH3 dephosphorylation in etiolated seedlings, we could potentially accelerate the onset of phototropism. Etiolated seedlings were irradiated with 0.005, 0.5, and 20 µmol m−2 s−1 unilateral blue light for 1 h, and the phosphorylation status of NPH3 was examined by immunoblotting. The dephosphorylation of NPH3 became more apparent as the light intensity increased (Fig. 8A). In particular, NPH3 phosphorylation was substantially sustained at 0.005 µmol m−2 s−1. Consistent with a model in which reduced NPH3 dephosphorylation promotes phototropic responsiveness, the onset of phototropism at 0.005 µmol m−2 s−1 was enhanced, compared with the response at 0.5 µmol m−2 s−1 (Fig. 8B). Conversely, phototropism was delayed at 20 µmol m−2 s−1 (Fig. 8B), which corresponded to a small but detectable increase in NPH3 dephosphorylation (Fig. 8A).

Figure 8.

NPH3 dephosphorylation and hypocotyl curvature responses to increasing fluence rates in etiolated and deetiolated seedlings. A, Immunoblot analysis of total protein extracts from etiolated and deetiolated seedlings maintained in darkness (D) or irradiated with 0.005, 0.5, or 20 µmol m−2 s−1 unilateral blue light for 60 min. Protein extracts were probed with anti-NPH3 antibody. B and C, Phototropism of etiolated (B) and deetiolated (C) seedlings irradiated with 0.005, 0.5, or 20 µmol m−2 s−1 unilateral blue light. Hypocotyl curvatures were measured every 10 min for 4 h, and each value is the mean ± se of 20 seedlings.

In deetiolated seedlings, NPH3 remained largely phosphorylated following irradiation with 0.005 µmol m−2 s−1 (Fig. 8A). Phototropic responsiveness at this light level was similar to that measured at 0.5 µmol m−2 s−1 (Fig. 8C). While there is a limit on how accurately we can measure the phosphorylation status of NPH3 by immunoblotting, especially when multiple phosphorylated forms of NPH3 appear to exist (Haga et al., 2015), irradiation at 20 µmol m−2 s−1 delayed the onset of phototropism (Fig. 8C) and increased the level of NPH3 dephosphorylation (Fig. 8A). These data therefore concur with a model in which maintaining a large pool of phosphorylated NPH3 promotes phototropic responsiveness while maintaining a large pool of dephosphorylated NPH3 reduces phototropic responsiveness.

DISCUSSION

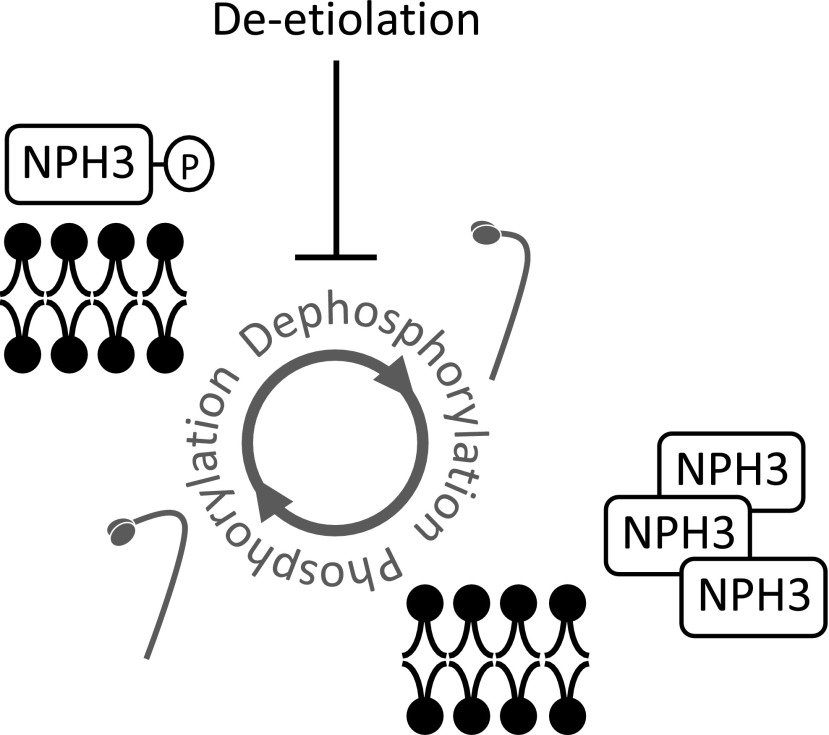

Based on our findings, we propose that deetiolation impacts the phosphorylation status and subcellular localization of NPH3, a core mediator of phototropic growth (Fig. 9). The regulation of protein activity by protein phosphorylation is often viewed as being a binary switch. However, our findings suggest that a finer rheostat-like process regulates NPH3; in this process, phototropic responsiveness is altered by modulating the equilibrium that exists between different NPH3 phosphorylation states. Our observations that deetiolation enhances phototropism in Arabidopsis (Fig. 1) and tomato (Supplemental Fig. S1) are consistent with earlier reports for other plant species (Gordon et al., 1982; Hart et al., 1982; Ellis, 1987; Jin et al., 2001). Increased phototropic responsiveness would enable deetiolated seedlings to maximize their photoautotrophic growth. Etiolated seedlings transition from being heterotrophic to photoautotrophic as they undergo phototropism. Indeed, a weaker phototropic response could help them to become established as they emerge from the soil, before they acquire full photoautotrophic capacity.

Figure 9.

Model depicting the correlation between NPH3 phosphorylation status, localization, and phototropic responsiveness. Sustained phosphorylation of NPH3 promotes its action in mediating phototropic signaling from the plasma membrane, whereas NPH3 dephosphorylation reduces its actions by internalizing NPH3 into aggregates.

The light activation of phot1 triggers the rapid dephosphorylation of NPH3 (Fig. 4B), whereas its rephosphorylation can occur after a period of prolonged irradiation or when plants are returned to darkness (Haga et al., 2015). The kinase(s) and phosphatase(s) responsible for this regulation remain to be identified. However, we propose that the fine-tuning of their activity could alter the steady-state levels of NPH3 phosphorylation, thereby altering the phototropic response. This is especially apparent for deetiolated seedlings, where a sustained level of NPH3 phosphorylation (Fig. 4B) underpins an enhanced phototropic response (Fig. 1A). A link between reduced NPH3 dephosphorylation and an increase in phototropic responsiveness was also detected in etiolated seedlings subjected to different intensities of phototropic stimulation (Fig. 8). These findings lead us to conclude that sustained NPH3 phosphorylation and plasma membrane localization promotes its action in establishing hypocotyl curvature, whereas NPH3 dephosphorylation and internalization into aggregates diminishes it (Fig. 9). Such a model is consistent with recent work showing that the rephosphorylation of NPH3 is necessary for sensory adaptation to promote efficient phototropism under brighter light conditions (Haga et al., 2015; Christie et al., 2018). It is tempting to speculate that light-driven decreases in gibberellin or brassinosteroid levels contribute to the enhancement effect of deetiolation on phototropism. However, gibberellin mutants exhibited reduced phototropism (Tsuchida-Mayama et al., 2010), while brassinosteroid mutants showed normal phototropism under the light conditions used in this study (Whippo and Hangarter, 2005).

Multiple phosphorylation states of NPH3 appear to exist (Fig. 4B). Identifying the differences between these phosphorylated forms and their functional significance will be challenging. So far, ∼18 phosphorylation sites have been identified for NPH3 through global phosphoproteomic approaches (Christie et al., 2018). Ser-212, Ser-222, and Ser-236, which are located downstream of the BTB domain, have been previously identified as being sites of dephosphorylation (Tsuchida-Mayama et al., 2008). However, the mutation of these sites to Ala does not appear to adversely affect the ability of NPH3 to mediate hypocotyl phototropism in Arabidopsis (Tsuchida-Mayama et al., 2008; Haga et al., 2015). Further analysis is therefore required to understand how phosphorylation impacts and influences the function of NPH3.

Our current findings demonstrate that the dephosphorylation of NPH3 and its recruitment into subcellular aggregates can be ameliorated by OKA, a potent inhibitor of PP1 and PP2A (Fig. 6B; Supplemental Fig. S6). We therefore speculate that the sustained levels of NPH3 phosphorylation and plasma membrane localization, which correlate with the enhanced phototropic response of deetiolated seedlings, could arise from a reduced level of PP1/PP2A activity. Our genetic analysis excludes the involvement of phot2 (Fig. 2B) and RPT2 (Fig. 7) in modulating the phosphorylation status of NPH3 in deetiolated seedlings. RPT2 transcripts are abundant in deetiolated seedlings (Supplemental Fig. S7), but the role of RPT2 in facilitating phototropism appears to be negligible at blue light intensities between 0.005 and 0.5 µmol m−2 s−1 (Fig. 7, B and C). Recent work has shown that PKS4 acts in conjunction with phot1 to reduce phototropic responsiveness at higher light intensities (Schumacher et al., 2018). PKS4 is phosphorylated by phot1 (Demarsy et al., 2012), and the accumulation of its phosphorylated form has been shown to delay phototropism (Schumacher et al., 2018). However, this occurs by a mechanism that does not affect NPH3 dephosphorylation (Schumacher et al., 2018).

NPH3 dephosphorylation is tissue and, most likely, cell autonomous (Sullivan et al., 2016b), which agrees with our observations that unilateral blue light can produce a gradient of NPH3 aggregate formation across the irradiated hypocotyl (Fig. 5). Unilateral irradiation is proposed to establish differential phot1 autophosphorylation across the oat (Avena sativa) coleoptile, with a higher level of phosphorylation occurring on the irradiated side (Salomon et al., 1997). The subcellular aggregation profile of NPH3 within the seedling thus provides a convenient in vivo reporter for phot1 kinase activity. The differential activation of phot1, brought about by unilateral irradiation, leads auxin to accumulate on the shaded side of the hypocotyl (Christie et al., 2011; Ding et al., 2011), where it promotes increased cell expansion. How this auxin gradient is achieved, at a mechanistic level, remains unresolved. Mutants that lack the auxin efflux carriers PIN3, PIN4, and PIN7 are severely compromised in phototropism (Willige et al., 2013). PIN3 is laterally redistributed in etiolated seedlings following phototropic stimulation (Ding et al., 2011) by a process that appears to be clathrin dependent (Zhang et al., 2017), but how its relocalization contributes to lateral auxin transport is still not known. PIN-mediated auxin transport is also regulated by protein phosphorylation. D6 PROTEIN KINASES (D6PKs) are known to directly phosphorylate PIN family members, and mutants deficient in D6PKs are defective in phototropism (Willige et al., 2013). Yet, how such changes in phosphorylation coordinate with phot1 and NPH3 remains poorly understood.

Phot1-NPH3 interactions at the plasma membrane are transiently disrupted upon irradiation (Haga et al., 2015), consistent with the partial relocalization of these proteins to different subcellular regions; phot1 internalizes into cytosolic structures (Sakamoto and Briggs, 2002), whereas NPH3 accumulates in subcellular aggregates (Supplemental Movie S1). The functional relevance of these transient changes in subcellular localization are still not known. At least for phot1, approaches aimed at tethering the photoreceptor to the plasma membrane through lipid binding suggest that diminishing its light-induced internalization does not alter its ability to function in Arabidopsis (Preuten et al., 2015). Moreover, biochemical fractionation experiments indicate that NPH3 aggregates accumulate in the cytosol (Haga et al., 2015) and that their formation is unaffected by cytoskeleton inhibitors or by inhibitors of vesicle trafficking (Haga et al., 2015). Although the identity of these aggregates has not been determined, their occurrence is highly dynamic (Supplemental Movie S1).

It is worth noting that the N- and C-terminal regions of NPH3 are predicted to be disordered (Supplemental Fig. S9). Intrinsically disordered regions (IDRs) within proteins are increasingly recognized as being important determinants of cellular signaling (Wright and Dyson, 2015) and can offer accessibility for assembling protein complexes. IDRs are often regions that are targeted for posttranslational modification (Bah and Forman-Kay, 2016) and are associated with the dynamic self-assembly of membrane-less nuclear or cytosolic organelles (Cuevas-Velazquez and Dinneny, 2018). Thus, the phosphorylation-dependent modulation of IDRs within NPH3 could produce different signaling outputs via alterations in its subcellular localization and its affinity for its interaction partners.

NPH3 has been identified as being a component of the 14-3-3 interactome in barley (Hordeum vulgare; Schoonheim et al., 2007). 14-3-3 proteins are also known to bind to phot1 and phot2 upon receptor autophosphorylation (Inoue et al., 2008a; Sullivan et al., 2009; Tseng et al., 2012), but the functional relevance of this interaction remains unknown. Further studies are now required to evaluate how 14-3-3 binding integrates into the rheostat-like mechanism that we propose from our findings here and how this governs the phosphorylation and subcellular localization status of NPH3 (Fig. 9).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plant Materials and Growth Conditions

Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana) wild type (gl-1, ecotype Columbia), phot1-5 (Liscum and Briggs, 1995), phot2-1 (Kagawa et al., 2001), phyA-211 phyB-9 (Sullivan et al., 2016a), cry1-304 cry2-1 (Mockler et al., 1999), nph3-6 (Motchoulski and Liscum, 1999), rpt2-2 (Inada et al., 2004), and the pifq quadruple mutant (Leivar et al., 2008) were previously described, as was tomato (Solanum lycopersicum; Sharma et al., 2014). Arabidopsis seeds were surface sterilized and planted on one-half-strength Murashige and Skoog (MS) medium with 0.8% (w/v) agar and grown vertically or sown in transparent plastic entomology boxes (Watkins and Doncaster) on a layer of silicon dioxide (Sigma-Aldrich) watered with one-quarter-strength MS medium. Following stratification in the dark at 4°C for 2 to 5 d, seeds were exposed to 80 µmol m−2 s−1 white light for 6 to 8 h to induce germination before incubation in the dark for 64 h for etiolated seedlings. Deetiolated seedlings were incubated in the dark for 40 h, exposed to 80 µmol m−2 s−1 white light for 8 h, and then dark adapted for 16 h. For red or blue light treatment, white fluorescent light was filtered through Deep Golden Amber filter No. 135 (Lee Filters) or Moonlight Blue filter No. 183 (Lee Filters), respectively. Fluence rates for all light sources were measured with an Li-250A and quantum sensor (LI-COR).

Transformation of Arabidopsis

The transformation vector for NPH3::GFP-NPH3 was constructed using the modified binary expression vector pEZR(K)-LC (Christie et al., 2002). The 35S promoter was removed using restriction sites SacI and HindIII and replaced with the 2.1-kb NPH3 promoter amplified from Columbia genomic DNA with primers pNPH3-F (5′-AAAAGAGCTCAAACCCCACATTAATCAGACAGAATC-3′) and pNPH3-R (5′-AAAAAAGCTTACACAAGTTAACACTCTCTGTAGTTG-3′). The full-length coding sequence of NPH3 was amplified from complementary DNA and inserted using restriction sites KpnI and BamHI. The nph3-6 mutant was transformed with Agrobacterium tumefaciens strain GV3101 as previously described (Davis et al., 2009). Based on the segregation of kanamycin resistance, independent homozygous T3 lines were selected for analysis.

Phototropism

Phototropism of 3-d-old etiolated and deetiolated seedlings grown on a layer of silicon dioxide was performed as previously described in Sullivan et al. (2016a). Images of seedlings were captured every 10 min for 4 h, or every 20 min for 8 h, during unilateral illumination with 0.5 or 0.005 µmol m−2 s−1 blue light with a Retiga 6000 CCD camera (QImaging) connected to a personal computer running QCapture Pro 7 software (QImaging) with supplemental infrared light-emitting diode illumination. Measurements of hypocotyl angles were made using Fiji software (Schindelin et al., 2012). Tomato seeds were germinated on wet filter paper in the dark for 3 d at 25°C ± 2°C. Single germinated seeds were transferred into custom growth discs (3 cm × 1.5 cm), which contained a mixture of organic potting garden soil mix (Pepper Agro) and peat (1:3), and were grown for an additional 72 h in the dark for etiolated seedlings. Deetiolated seedlings were incubated in the dark for 48 h, exposed to 10 µmol m−2 s−1 white light for 8 h, and then dark adapted for 16 h. The seedlings were irradiated with 0.5 µmol m−2 s−1 blue light obtained from blue (λmax470) light-emitting diodes (Kwality Photonics). Images were captured every 10 min for 2 h with a C270 HD camera (Logitech) connected to a personal computer running Chronolapse software (https://code.google.com/archive/p/chronolapse/) and supplemented with infrared illumination. Measurements of hypocotyl angles were performed using NIH ImageJ software.

Immunoblot Analysis

Total proteins were extracted from 3-d-old etiolated or deetiolated seedlings by directly grinding 50 seedlings in 100 µL of 2× SDS sample buffer under red safelight illumination. Proteins were transferred onto a polyvinylidene fluoride membrane (Bio-Rad) with a Trans-Blot Turbo Transfer System (Bio-Rad) and detected with anti-phot1 or anti-phot2 polyclonal antibodies (Cho et al., 2007), anti-NPH3 polyclonal antibody (Tsuchida-Mayama et al., 2008), and anti-UGPase polyclonal antibody (Agrisera). Blots were developed with horseradish peroxidase-linked secondary antibodies (Promega) and Pierce ECL Plus Western Blotting Substrate (Thermo Fisher Scientific).

Confocal Microscopy

Localization of GFP-tagged NPH3 was visualized using a Leica SP8 laser scanning confocal microscope. The 488-nm excitation line was used, and GFP fluorescence was collected between 505 and 530 nm. Images were acquired at 1,024- × 1,024-pixel resolution with a line average of two. To image etiolated seedlings following unilateral irradiation, seedlings were transferred onto microscope slides covered with a thin layer of one-half-strength MS medium with 0.8% (w/v) agar. Seedlings were maintained in darkness or irradiated with unilateral blue light for 1 h before two partially overlapping sets of images were acquired. Images were assembled by using the Pairwise Stitching Plugin for Fiji (Preibisch et al., 2009). The number of GFP particles was measured using the Analyze Particles tool of Fiji, with a diameter of 0.5 to 50 µm and circularity of 0.5 to 1.

OKA Treatment

OKA (Abcam) was prepared as a 1 mm stock solution in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO). Hypocotyl segments of etiolated and deetiolated seedlings were prepared by dissection immediately below the cotyledonary node and root-shoot junction using a dissecting microscope with micro scissors (Fine Science Tools) using red safelight illumination. Dissected seedlings were transferred to six-well plates containing one-quarter-strength MS medium and the indicated concentration of OKA or DMSO as a solvent control; the final DMSO concentration was 1% (v/v) for all treatments. Seedlings were vacuum infiltrated for 15 min, followed by incubation in darkness for 2 h with gentle agitation. Seedlings were maintained in darkness or irradiated with the indicated fluence of blue light for 1 h before confocal observation or protein extraction. For protein extraction, seedlings were blotted on filter paper before undergoing grinding in 2× SDS sample buffer.

Hypocotyl Elongation Assay

Hypocotyl elongation assays were performed according to Takahashi et al. (2012). Apical hypocotyl segments of 4 mm were prepared from etiolated or deetiolated seedlings using a dissecting microscope with micro scissors (Fine Science Tools) and incubated on depletion medium (10 mm KCl, 1 mm MES-KOH [pH 6], and 0.8% [w/v] agar) for 1 to 1.5 h in darkness. Hypocotyl segments were transferred to depletion medium that contained 0, 10, or 100 µm IAA and were photographed with a digital camera every 10 min for 90 min. All manipulations were performed under red safelight illumination. Hypocotyl segment lengths were measured using Fiji software (Schindelin et al., 2012).

Transcript Analysis

Total RNA was isolated from 3-d-old etiolated and deetiolated seedlings using the RNeasy Plant Mini Kit (Qiagen) and was DNase treated (Turbo DNA-free; Thermo Fisher Scientific). Complementary DNA was synthesized from 1 µg of total RNA using oligo(dT) and SuperScript II reverse transcriptase (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Quantitative PCR was performed with Brilliant III SYBR Green QPCR Master Mix (Agilent) on a StepOnePlus (Thermo Fisher Scientific) real-time PCR system using primers for RPT2 (RTP2-F, 5′-TTGCTGGTCGGACACAAGACTTC-3′, and RTP2-R, 5′-CATTGCCTCGTTGCAAGCCTTAG-3′). IRON SULFUR CLUSTER ASSEMBLY PROTEIN1 (AT4G22220) was used as the reference gene (Bordage et al., 2016).

Protein Disorder Prediction

Protein disorder was predicted by using the online server PrDOS (Ishida and Kinoshita, 2007).

Supplemental Data

The following supplemental materials are available.

Supplemental Figure S1. Deetiolated tomato seedlings show enhanced kinetics of phototropism.

Supplemental Figure S2. Protein abundance of phot1 and phot2 in etiolated and deetiolated seedlings.

Supplemental Figure S3. Phototropic responses of wild-type seedlings deetiolated under different light conditions.

Supplemental Figure S4. Phototropic responses and NPH3 phosphorylation status in etiolated and deetiolated seedlings of the pgm1 mutant.

Supplemental Figure S5. GFP-NPH3 functionality and phosphorylation status in etiolated and deetiolated seedlings.

Supplemental Figure S6. Effect of OKA treatment on blue light-induced NPH3 dephosphorylation.

Supplemental Figure S7. Deetiolated seedlings have increased RPT2 expression levels.

Supplemental Figure S8. Deetiolated wild-type seedlings show enhanced phototropism at 0.005 µmol m−2 s−1 unilateral blue light.

Supplemental Figure S9. PrDOS plot of disordered regions in NPH3.

Supplemental Movie S1. Dynamic blue light-induced changes in the subcellular localization of GFP-NPH3.

Acknowledgments

We thank Eve-Marie Josse for providing pifq seed and for the support from undergraduate and postgraduate project students throughout the duration of this work and Jane Alfred for editing the article.

Footnotes

This work as supported by the Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council (BB/J016047/1, BB/M002128/1, and BB/R001499/1 to J.M.C.), the Department of Biotechnology, Government of India, for a Biotechnology Overseas Associateship (to E.K.), and by the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (16H01231 and 17H03694 to T.S.).

Articles can be viewed without a subscription.

References

- Bah A, Forman-Kay JD (2016) Modulation of intrinsically disordered protein function by post-translational modifications. J Biol Chem 291: 6696–6705 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bordage S, Sullivan S, Laird J, Millar AJ, Nimmo HG (2016) Organ specificity in the plant circadian system is explained by different light inputs to the shoot and root clocks. New Phytol 212: 136–149 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho HY, Tseng TS, Kaiserli E, Sullivan S, Christie JM, Briggs WR (2007) Physiological roles of the light, oxygen, or voltage domains of phototropin 1 and phototropin 2 in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol 143: 517–529 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christie JM, Murphy AS (2013) Shoot phototropism in higher plants: New light through old concepts. Am J Bot 100: 35–46 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christie JM, Swartz TE, Bogomolni RA, Briggs WR (2002) Phototropin LOV domains exhibit distinct roles in regulating photoreceptor function. Plant J 32: 205–219 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christie JM, Yang H, Richter GL, Sullivan S, Thomson CE, Lin J, Titapiwatanakun B, Ennis M, Kaiserli E, Lee OR, et al. (2011) phot1 inhibition of ABCB19 primes lateral auxin fluxes in the shoot apex required for phototropism. PLoS Biol 9: e1001076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christie JM, Suetsugu N, Sullivan S, Wada M (2018) Shining light on the function of NPH3/RPT2-like proteins in phototropin signaling. Plant Physiol 176: 1015–1024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuevas-Velazquez CL, Dinneny JR (2018) Organization out of disorder: Liquid-liquid phase separation in plants. Curr Opin Plant Biol 45: 68–74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis AM, Hall A, Millar AJ, Darrah C, Davis SJ (2009) Protocol: Streamlined sub-protocols for floral-dip transformation and selection of transformants in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Methods 5: 3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demarsy E, Schepens I, Okajima K, Hersch M, Bergmann S, Christie J, Shimazaki K, Tokutomi S, Fankhauser C (2012) Phytochrome Kinase Substrate 4 is phosphorylated by the phototropin 1 photoreceptor. EMBO J 31: 3457–3467 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng Z, Oses-Prieto JA, Kutschera U, Tseng TS, Hao L, Burlingame AL, Wang ZY, Briggs WR (2014) Blue light-induced proteomic changes in etiolated Arabidopsis seedlings. J Proteome Res 13: 2524–2533 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding Z, Galván-Ampudia CS, Demarsy E, Łangowski Ł, Kleine-Vehn J, Fan Y, Morita MT, Tasaka M, Fankhauser C, Offringa R, et al. (2011) Light-mediated polarization of the PIN3 auxin transporter for the phototropic response in Arabidopsis. Nat Cell Biol 13: 447–452 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis RJ. (1987) Comparison of fluence-response relationships of phototropism in light- and dark-grown buckwheat. Plant Physiol 85: 689–692 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fankhauser C, Christie JM (2015) Plant phototropic growth. Curr Biol 25: R384–R389 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gendreau E, Traas J, Desnos T, Grandjean O, Caboche M, Höfte H (1997) Cellular basis of hypocotyl growth in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Physiol 114: 295–305 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon DC, Macdonald IR, Hart JW (1982) Regional growth-patterns in the hypocotyls of etiolated and green cress seedlings in light and darkness. Plant Cell Environ 5: 347–353 [Google Scholar]

- Goyal A, Szarzynska B, Fankhauser C (2013) Phototropism: At the crossroads of light-signaling pathways. Trends Plant Sci 18: 393–401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haga K, Takano M, Neumann R, Iino M (2005) The rice COLEOPTILE PHOTOTROPISM1 gene encoding an ortholog of Arabidopsis NPH3 is required for phototropism of coleoptiles and lateral translocation of auxin. Plant Cell 17: 103–115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haga K, Tsuchida-Mayama T, Yamada M, Sakai T (2015) Arabidopsis ROOT PHOTOTROPISM2 contributes to the adaptation to high-intensity light in phototropic responses. Plant Cell 27: 1098–1112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hart JW, Macdonald IR (1981) Phototropic responses of hypocotyls of etiolated and green seedlings. Plant Sci Lett 21: 151–158 [Google Scholar]

- Hart JW, Gordon DC, Macdonald IR (1982) Analysis of growth during phototropic curvature of cress hypocotyls. Plant Cell Environ 5: 361–366 [Google Scholar]

- Hohm T, Demarsy E, Quan C, Allenbach Petrolati L, Preuten T, Vernoux T, Bergmann S, Fankhauser C (2014) Plasma membrane H+-ATPase regulation is required for auxin gradient formation preceding phototropic growth. Mol Syst Biol 10: 751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inada S, Ohgishi M, Mayama T, Okada K, Sakai T (2004) RPT2 is a signal transducer involved in phototropic response and stomatal opening by association with phototropin 1 in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell 16: 887–896 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inoue S, Kinoshita T, Matsumoto M, Nakayama KI, Doi M, Shimazaki K (2008a) Blue light-induced autophosphorylation of phototropin is a primary step for signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 105: 5626–5631 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inoue S, Kinoshita T, Takemiya A, Doi M, Shimazaki K (2008b) Leaf positioning of Arabidopsis in response to blue light. Mol Plant 1: 15–26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishida T, Kinoshita K (2007) PrDOS: Prediction of disordered protein regions from amino acid sequence. Nucleic Acids Res 35: W460–W464 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin X, Zhu J, Zeiger E (2001) The hypocotyl chloroplast plays a role in phototropic bending of Arabidopsis seedlings: Developmental and genetic evidence. J Exp Bot 52: 91–97 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kagawa T, Sakai T, Suetsugu N, Oikawa K, Ishiguro S, Kato T, Tabata S, Okada K, Wada M (2001) Arabidopsis NPL1: A phototropin homolog controlling the chloroplast high-light avoidance response. Science 291: 2138–2141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kami C, Hersch M, Trevisan M, Genoud T, Hiltbrunner A, Bergmann S, Fankhauser C (2012) Nuclear phytochrome A signaling promotes phototropism in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 24: 566–576 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kami C, Allenbach L, Zourelidou M, Ljung K, Schütz F, Isono E, Watahiki MK, Yamamoto KT, Schwechheimer C, Fankhauser C (2014) Reduced phototropism in pks mutants may be due to altered auxin-regulated gene expression or reduced lateral auxin transport. Plant J 77: 393–403 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim K, Shin J, Lee SH, Kweon HS, Maloof JN, Choi G (2011) Phytochromes inhibit hypocotyl negative gravitropism by regulating the development of endodermal amyloplasts through phytochrome-interacting factors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 108: 1729–1734 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirchenbauer D, Viczián A, Ádám É, Hegedűs Z, Klose C, Leppert M, Hiltbrunner A, Kircher S, Schäfer E, Nagy F (2016) Characterization of photomorphogenic responses and signaling cascades controlled by phytochrome-A expressed in different tissues. New Phytol 211: 584–598 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leivar P, Monte E, Oka Y, Liu T, Carle C, Castillon A, Huq E, Quail PH (2008) Multiple phytochrome-interacting bHLH transcription factors repress premature seedling photomorphogenesis in darkness. Curr Biol 18: 1815–1823 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liscum E, Briggs WR (1995) Mutations in the NPH1 locus of Arabidopsis disrupt the perception of phototropic stimuli. Plant Cell 7: 473–485 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liscum E, Askinosie SK, Leuchtman DL, Morrow J, Willenburg KT, Coats DR (2014) Phototropism: Growing towards an understanding of plant movement. Plant Cell 26: 38–55 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mockler TC, Guo H, Yang H, Duong H, Lin C (1999) Antagonistic actions of Arabidopsis cryptochromes and phytochrome B in the regulation of floral induction. Development 126: 2073–2082 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Motchoulski A, Liscum E (1999) Arabidopsis NPH3: A NPH1 photoreceptor-interacting protein essential for phototropism. Science 286: 961–964 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okada K, Shimura Y (1992) Mutational analysis of root gravitropism and phototropism of Arabidopsis thaliana seedlings. Aust J Plant Physiol 19: 439–448 [Google Scholar]

- Pedmale UV, Liscum E (2007) Regulation of phototropic signaling in Arabidopsis via phosphorylation state changes in the phototropin 1-interacting protein NPH3. J Biol Chem 282: 19992–20001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preibisch S, Saalfeld S, Tomancak P (2009) Globally optimal stitching of tiled 3D microscopic image acquisitions. Bioinformatics 25: 1463–1465 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preuten T, Hohm T, Bergmann S, Fankhauser C (2013) Defining the site of light perception and initiation of phototropism in Arabidopsis. Curr Biol 23: 1934–1938 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preuten T, Blackwood L, Christie JM, Fankhauser C (2015) Lipid anchoring of Arabidopsis phototropin 1 to assess the functional significance of receptor internalization: Should I stay or should I go? New Phytol 206: 1038–1050 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts D, Pedmale UV, Morrow J, Sachdev S, Lechner E, Tang X, Zheng N, Hannink M, Genschik P, Liscum E (2011) Modulation of phototropic responsiveness in Arabidopsis through ubiquitination of phototropin 1 by the CUL3-Ring E3 ubiquitin ligase CRL3(NPH3). Plant Cell 23: 3627–3640 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakai T, Haga K (2012) Molecular genetic analysis of phototropism in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell Physiol 53: 1517–1534 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakai T, Wada T, Ishiguro S, Okada K (2000) RPT2: A signal transducer of the phototropic response in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 12: 225–236 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakai T, Kagawa T, Kasahara M, Swartz TE, Christie JM, Briggs WR, Wada M, Okada K (2001) Arabidopsis nph1 and npl1: Blue light receptors that mediate both phototropism and chloroplast relocation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 98: 6969–6974 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakamoto K, Briggs WR (2002) Cellular and subcellular localization of phototropin 1. Plant Cell 14: 1723–1735 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salomon M, Zacherl M, Rudiger W (1997) Asymmetric, blue light-dependent phosphorylation of a 116-kilodalton plasma membrane protein can be correlated with the first- and second-positive phototropic curvature of oat coleoptiles. Plant Physiol 115: 485–491 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schindelin J, Arganda-Carreras I, Frise E, Kaynig V, Longair M, Pietzsch T, Preibisch S, Rueden C, Saalfeld S, Schmid B, et al. (2012) Fiji: An open-source platform for biological-image analysis. Nat Methods 9: 676–682 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoonheim PJ, Veiga H, Pereira DdC, Friso G, van Wijk KJ, de Boer AH (2007) A comprehensive analysis of the 14-3-3 interactome in barley leaves using a complementary proteomics and two-hybrid approach. Plant Physiol 143: 670–683 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schumacher P, Demarsy E, Waridel P, Petrolati LA, Trevisan M, Fankhauser C (2018) A phosphorylation switch turns a positive regulator of phototropism into an inhibitor of the process. Nat Commun 9: 2403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma S, Kharshiing E, Srinivas A, Zikihara K, Tokutomi S, Nagatani A, Fukayama H, Bodanapu R, Behera RK, Sreelakshmi Y, et al. (2014) A dominant mutation in the light-oxygen and voltage2 domain vicinity impairs phototropin1 signaling in tomato. Plant Physiol 164: 2030–2044 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan S, Thomson CE, Kaiserli E, Christie JM (2009) Interaction specificity of Arabidopsis 14-3-3 proteins with phototropin receptor kinases. FEBS Lett 583: 2187–2193 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan S, Hart JE, Rasch P, Walker CH, Christie JM (2016a) Phytochrome A mediates blue-light enhancement of second-positive phototropism in Arabidopsis. Front Plant Sci 7: 290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan S, Takemiya A, Kharshiing E, Cloix C, Shimazaki KI, Christie JM (2016b) Functional characterization of Arabidopsis phototropin 1 in the hypocotyl apex. Plant J 88: 907–920 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi K, Hayashi K, Kinoshita T (2012) Auxin activates the plasma membrane H+-ATPase by phosphorylation during hypocotyl elongation in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol 159: 632–641 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tseng TS, Whippo C, Hangarter RP, Briggs WR (2012) The role of a 14-3-3 protein in stomatal opening mediated by PHOT2 in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 24: 1114–1126 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsuchida-Mayama T, Nakano M, Uehara Y, Sano M, Fujisawa N, Okada K, Sakai T (2008) Mapping of the phosphorylation sites on the phototropic signal transducer, NPH3. Plant Sci 174: 626–633 [Google Scholar]

- Tsuchida-Mayama T, Sakai T, Hanada A, Uehara Y, Asami T, Yamaguchi S (2010) Role of the phytochrome and cryptochrome signaling pathways in hypocotyl phototropism. Plant J 62: 653–662 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vitha S, Zhao L, Sack FD (2000) Interaction of root gravitropism and phototropism in Arabidopsis wild-type and starchless mutants. Plant Physiol 122: 453–462 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whippo C, Hangarter R (2004) Phytochrome modulation of blue-light-induced phototropism. Plant Cell Environ 27: 1223–1228 [Google Scholar]

- Whippo CW, Hangarter RP (2005) A brassinosteroid-hypersensitive mutant of BAK1 indicates that a convergence of photomorphogenic and hormonal signaling modulates phototropism. Plant Physiol 139: 448–457 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willige BC, Ahlers S, Zourelidou M, Barbosa IC, Demarsy E, Trevisan M, Davis PA, Roelfsema MR, Hangarter R, Fankhauser C, et al. (2013) D6PK AGCVIII kinases are required for auxin transport and phototropic hypocotyl bending in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 25: 1674–1688 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright PE, Dyson HJ (2015) Intrinsically disordered proteins in cellular signalling and regulation. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 16: 18–29 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto K, Suzuki T, Aihara Y, Haga K, Sakai T, Nagatani A (2014) The phototropic response is locally regulated within the topmost light-responsive region of the Arabidopsis thaliana seedling. Plant Cell Physiol 55: 497–506 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Yu Q, Jiang N, Yan X, Wang C, Wang Q, Liu J, Zhu M, Bednarek SY, Xu J, et al. (2017) Clathrin regulates blue light-triggered lateral auxin distribution and hypocotyl phototropism in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell Environ 40: 165–176 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]