Abstract

Understanding the role of the epigenome in protein-misfolding diseases remains a challenge in light of genetic diversity found in the world-wide population revealed by human genome sequencing efforts and the highly variable response of the disease population to therapeutics. An ever-growing body of evidence has shown that histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitors (HDACi) can have significant benefit in correcting protein-misfolding diseases that occur in response to both familial and somatic mutation. Cystic fibrosis (CF) is a familial autosomal recessive disease, caused by genetic diversity in the CF transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) gene, a cyclic Adenosine MonoPhosphate (cAMP)-dependent chloride channel expressed at the apical plasma membrane of epithelial cells in multiple tissues. The potential utility of HDACi in correcting the phenylalanine 508 deletion (F508del) CFTR variant as well as the over 2000 CF-associated variants remains controversial. To address this concern, we examined the impact of US Food and Drug Administration–approved HDACi on the trafficking and function of a panel of CFTR variants. Our data reveal that panobinostat (LBH-589) and romidepsin (FK-228) provide functional correction of Class II and III CFTR variants, restoring cell surface chloride channel activity in primary human bronchial epithelial cells. We further demonstrate a synergistic effect of these HDACi with Vx809, which can significantly restore channel activity for multiple CFTR variants. These data suggest that HDACi can serve to level the cellular playing field for correcting CF-causing mutations, a leveling effect that might also extend to other protein-misfolding diseases.

Introduction

Cystic fibrosis (CF) transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) is a multi-membrane–spanning polypeptide belonging to the ATP Binding Cassette (ABC) transporter family. It is composed of five functional domains: two nucleotidebinding domains (NBD1 and NBD2), two membrane-spanning domains (MSD1 and MSD2) and one regulatory domain. CFTR functions as a cAMP-sensitive chloride channel at the apical plasma membrane (PM) of cells. It is charged with maintaining ion balance and hydration in sweat, intestinal, pancreatic and pulmonary tissues; each providing a unique physiological environment that could affect the synthesis, trafficking and function of this chloride channel (1), differences that are assigned through Variation Spatial Profiling (VSP), a new approach that captures the influence of Spatial Covariance (SCV) on CFTR variant activity for the entire protein fold (2). The biogenesis of CFTR requires trafficking from the endoplasmic reticulum (ER), the first step in the exocytic pathway, through the Golgi to its final destination at the apical cell surface of epithelial cells. The loss of a functional CFTR channel disrupts ion homeostasis, resulting in increased mucus viscosity in the airway of the lung (3) and ductal systems of the pancreas and liver and hydration of the intestinal tract (4). The increased mucus viscosity causes increased risk for inflammation and infection by Pseudomonas aeruginosa in the lung (3) and reduced enzyme secretion in the digestive tract (4).

An analysis of the allele frequency of CF-causing mutations revealed that approximately 90% of patients carry at least one copy of a three base pair deletion leading to the loss of a phenylalanine at position 508 (F508del) in NBD1 (5,6). The F508del mutation disrupts the folding of the variant protein, leading to its retention in the ER and clearance by ER-associated degradation (7–13). While F508del-CFTR is by far the most common CF-associated variant, more than 2000 disease-causing mutations have been reported in the clinic (www.genet.sickkids.on.ca and www.CFTR2.org), with ~40% of them predicted to be missense mutations (4). These mutations are distributed across the entire sequence of the CFTR gene and are grouped into one of six Classes based on their associated functional defect including mutations that lead to a loss of CFTR production (Class I), misfolding and/or premature degradation (Class II), functional impairment (Class III), obstruction of the channel pore (Class IV), a reduction in the amount of CFTR produced (Class V) and destabilization of CFTR at the cell surface (Class VI) (4,6,14).

The search for therapeutic solutions that address the genetic diversity responsible for the differential onset and progression of CF disease (2) resulted in the discovery of Lumacaftor (Vx809), a small molecule that corrects the trafficking defect associated with the F508del variant and other Class II variants (15,16). However, it has shown limited and variable clinical value to date (14). In contrast, a different Class of compounds, referred to as ‘potentiators’, such as the compound Ivacaftor, which acts as a small molecule ‘gate opener’, can provide significant improvement in the channel activity of Class III and IV variants (<5% of the CF population) that show variable degrees of trafficking to the cell surface (17,18). Ivacaftor is currently approved for clinical use in combination with correctors such as Lumacaftor (Orkambi) and Tezacaftor to partially improve the efficacy of these drugs for Class II variants. They do so, presumably, by improving the channel gating of the trafficking-corrected pool of Class II variants. In some instances, these potentiators can antagonize corrector properties, suggesting the need to properly manage the fold at different stages of trafficking (19). Despite these clinical advancements, the vast majority of CFTR variants remain largely refractory to current therapeutic approaches. Thus, considerable work is needed to improve patient responses to existing therapeutics, including the heterogeneous clinical response exhibited by patients with the same genotype such as F508del reflecting the inherent diversity of their genomes, effects that might be caused by differences in genetic and epigenetic modifiers.

We now appreciate the importance of epigenetic modifications, such as methylation and acetylation, as key features impacting genetic diversity during development and aging. Epigenomic changes are regulated by histone deacetylases (HDACs) and histone acetyl transferases (HATs), as well as by other factors including Histone Methyl Transferases (HMTs), histone demethylases and Bromo-Domain proteins, together comprising the ‘reader, writer, eraser’ cohort that differentially and uniquely manage the genome of each individual (20–24). HATs/HDACs mediate the acetylation balance of histones, which manage the open and closed chromatin states to provide access to transcription factors. They also mediate the acetylation state of numerous non-histone proteins, highlighted by the dynamic acetylome, that includes proteostasis components (1,25–31) regulating the central heat shock response (HSR) (32) and unfolded protein response (UPR) (33,34) programs responsible for recovery from protein-folding stress (24,35–41), as observed in CF (42).

How HDAC-regulated epigenomic programs translate genetic diversity found in the genome into a functional proteome to contribute to health and disease of each CF individual remains enigmatic. There is now considerable interest in the use of HDAC inhibitors (HDACi) to improve the management of numerous rare protein-folding diseases including CF, Niemann–Pick C1 (43–46), Alpha-1-AntiTrypsin Deficiency (47–49) and lysosomal storage disorders (24,50–65). Moreover, there is an ever-growing body of evidence that HDACi could play a crucial therapeutic role in complex familial and somatic disease including lung fibrosis, Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (66), arthritis, hypertension, septic shock and neurodegenerative disease including Alzheimer’s, Huntington’s and Parkinson’s (67–69). These results suggest a more general role for HDAC in establishing operational ‘set-points’ in the cell for folding management in response to genetic diversity contributing to human health and disease (2,70). This raises the possibility that modulators of HDAC could serve as more global epigenetic modifiers to manipulate the physiological state of the cell to accommodate the broad range of familial and somatic variation observed in the world-wide CF population.

To address the role of the epigenome in CF biology, we now examine the impact of a rapidly expanding Class of HDACi on mitigation of CF etiology (43,47–49,71–74). While the vast majority of these compounds are under investigation as anti-cancer therapeutics, where they are used to kill cells, we focus on their potential beneficial effects given the well-recognized role of HDACs in promoting normal development, differentiation and response to stress and the environment (75). The human genome encodes 18 HDACs, grouped into 4 Classes (I–IV) with a wide range of substrate specificities based on domain structures flanking the highly conserved catalytic site found in each isoform that distinguish the Zn2+-dependent Class I & II enzymes (76). HDACi can have both positive and negative effects on gene expression and protein function depending on the Lys/Arg residues affected by the targeted HDAC and the role of these residues in protein function (76).

It is clear that the epigenetic impact of HDACs represent an important yet unfulfilled opportunity to alter the transcriptional, translational and/or post-translational acetylation balance to improve the function and stability of misfolded proteins driving human disease. Vorinostat, belinostat, panobinostat and romidepsin are four HDACi approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to treat cutaneous and peripheral T-cell lymphoma (75,77–79). Vorinostat appears to abrogate the phenotypic defects associated with the F508del variant by modulating immune responses (80,81) and improving the stability and trafficking of F508del-CFTR (74,82). While a recent manuscript has reported conflicting data pertaining to the impact of Vorinostat on the F508del variant of CFTR in nasal epithelial cells, the results likely reflect expected cell-specific environments that are differentially sensitive to epigenetic alterations (82). Given the low and variable response for all CFTR Classes to known corrector/potentiator therapeutics, an urgent need exists for general modifiers of drug responses that level the playing field for a given variant within the population.

Herein, we examine the impact of the HDACi belinostat (PXD-101), panobinostat (LBH-589) and romidepsin (FK-228) on the stability, trafficking and function of CFTR variants alone or in combination with the CFTR corrector, Vx809. We provide evidence that these HDACi can correct the trafficking defect associated with Class II (ER export defective) & III/IV (gating/channel function defective) CFTR variants and restore cell surface chloride channel activity in primary human bronchial epithelial (hBE) cells homozygous for F508del. We observe a synergistic effect of these HDACi when treated in combination with Vx809 for restoring channel activity to therapeutically relevant levels for multiple CFTR variants.

Results

HDACi treatment corrects F508del CFTR trafficking

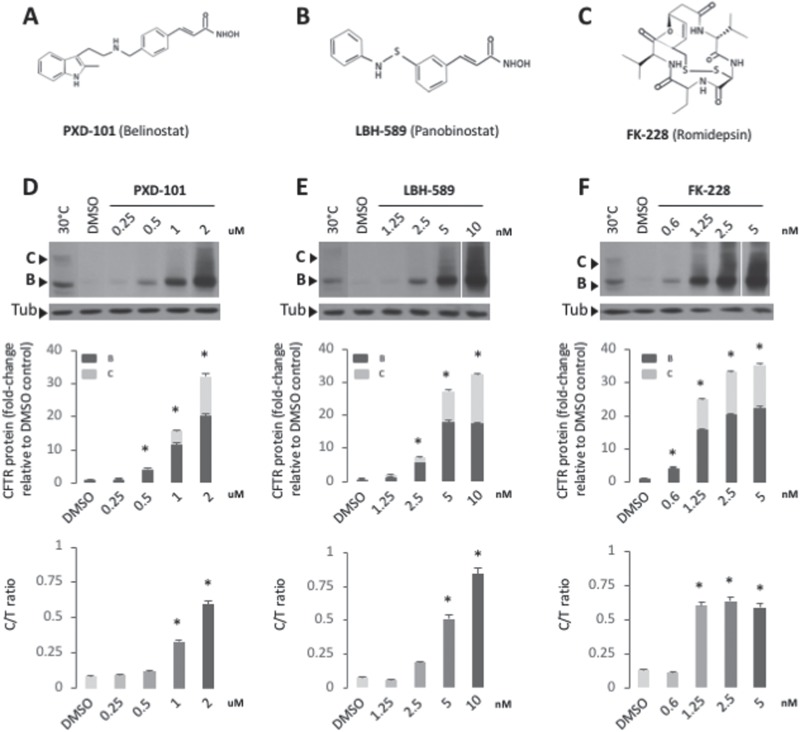

To begin to address the role of the epigenome in managing the cellular proteostasis environment, which determines the fate of disease-associated misfolded proteins, we investigated the impact of three additional FDA-approved HDACi, namely PXD-101, LBH-589 and FK-228 (Fig. 1A–C) (75,77,78), on the trafficking and functional correction of F508del CFTR in CFBE-F508del and primary hBE cells homozygous for the F508del variant.

Figure 1.

PXD-101, LBH-589 & FK-228 rescue F508del CFTR trafficking in CFBE-F508del. Chemical structure of PXD-101 (A), LBH-589 (B) and FK-228 (C). Immunoblot analysis (upper) and quantifications (middle and lower) of CFTR expression following treatment of CFBE-F508del cells with different concentration of PXD-101 (D), LBH-589 (E) and FK-228 (F). Data are presented in middle panel as fold change relative to DMSO treatment (mean ± SEM, n ≥ 3). Lower panel represent a quantification of C/T ratio expressed as a % (mean ± SEM, n ≥ 3).

The membrane trafficking of CFTR from the ER to the Golgi compartment can be assessed by monitoring the differential migration of the CFTR glycoforms on sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE). The band B fraction represents the N-linked glycosylated ER pool of CFTR (Fig. 1D–F). The trimming of these glycan chains in the Golgi compartment leads to the slower migration of the post-ER fraction of CFTR on an SDS-PAGE and is represented by the band C fraction (Fig. 1D–F). To assess the steady state distribution of these glycoforms and their response to HDACi, we first utilized CFBE-F508del cells, a bronchial epithelial cell line stably expressing the F508del CFTR transgene. In order to have a reference for the migration of the band B and C glycoforms, we included a loading control of CFBE-F508del cells cultured at reduced temperature (30°C), which has been shown to cause a partial correction of the trafficking defect associated with F508del CFTR (83). We observed that treatment with each of the three HDACi, PXD-101, LBH-589 and FK-228, caused a dose-dependent improvement in the expression of F508del CFTR (Fig. 1D–F), leading to as much as a 30-fold increase in total CFTR relative to that seen with vehicle treatment (Fig. 1D–F). It is important to note that the increased level of F508del CFTR seen with PXD-101 occurs in the micromolar range, while we obtained similar results with LBH-589 and FK-228 in the nanomolar range.

Given that HDACi’s have been largely used to induce cell death (84), we addressed if the observed effects on F508del CFTR were the result of cytotoxic changes in cellular proteostasis management leading to the loss of misfolding surveillance in the ER. To this end, we monitored the impact of PXD-101, LBH-589 and FK-228 on the viability of CFBE-F508del cells using the lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) cytotoxicity assay, which monitors the integrity of the PM by measuring the amount of the cytosolic enzyme, LDH, secreted into the culture media. We did not observe any toxicity with PXD-101 or LBH-589 at doses between 10 pm and 10 μm (Supplemetary Material, Fig. S1), indicating that these HDACi are not inducing cytotoxicity in the range where we observe changes in CFTR expression. While we did observe toxicity with FK-228 at 10 μm (Supplemetary Material, Fig. S1), this is three orders of magnitude above the dose where we see alterations in CFTR expression. The concentrations of HDACi where we observe correction of trafficking defect of the F508del variants are at or below the IC50 values shown to cause growth arrest of multiple cancer cell lines. Herein, we observed correction of F508del-CFTR trafficking with LBH589 and FK-228 at a doses of 5–10 nm and 1–5 nm, respectively, values below the reported IC50 value for LBH589 (IC50 = 25 nm) (85) and well-below to that of FK-228 (IC50 = 1 mm) (86,87) induced growth arrest. On the other hand, PXD-101-mediated correction of F508del-CFTR occurred at 1–2 μm, a dose similar to its IC50 for growth arrest (IC50 = 2.5 μm) (88,89). Taken as a whole, these data suggest that the observed effect of HDACi on F508del CFTR can be significantly below values associated with their potential cytotoxic effects in cancer cell–based models.

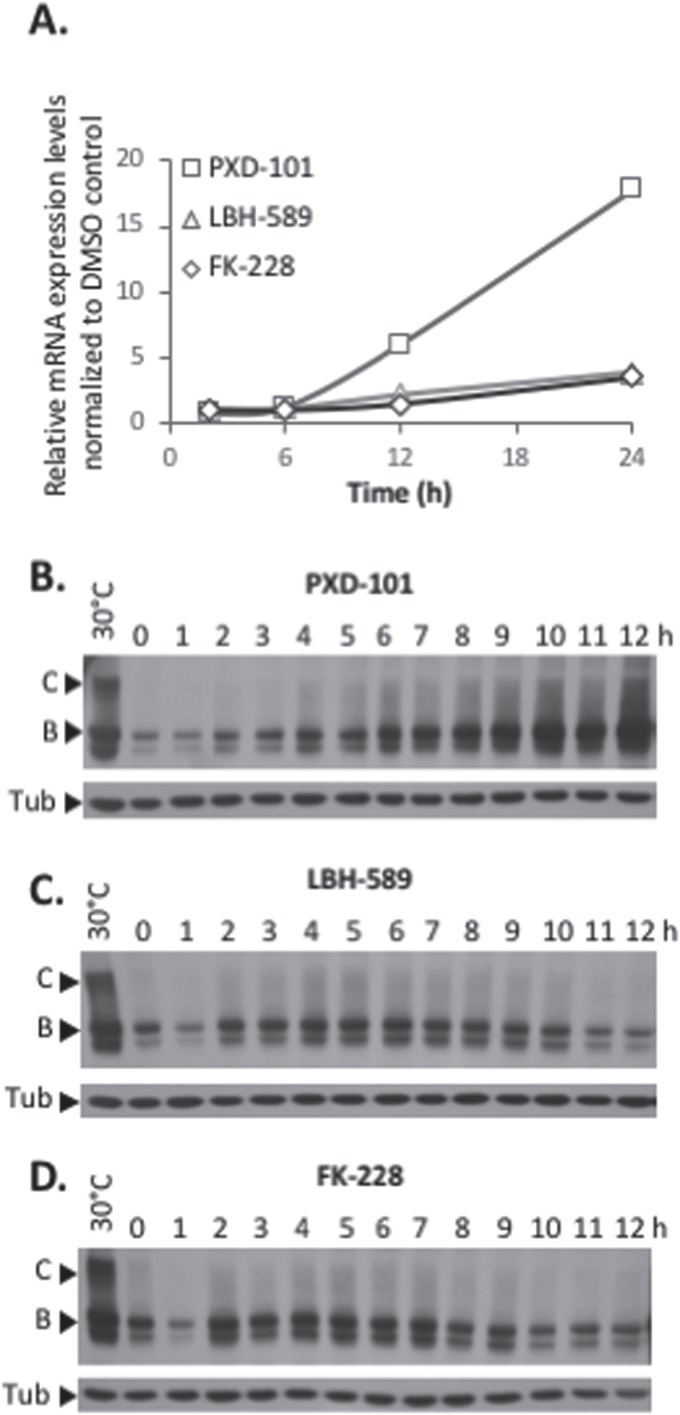

The increased cellular protein level of F508del CFTR could arise from increased stabilization and/or folding of the polypeptide or could stem from increased transcription. To address this latter possibility, we performed quantitative Polymerase Chain Reaction (qPCR) on HDACi-treated CFBE-F508del cells at the dose where we observed the maximal increase in CFTR protein levels. We observed a time-dependent increase in CFTR mRNA levels starting between 6 and 12 h post-HDACi treatment and continuing to increase up to 24 h after treatment (Fig. 2A).

Figure 2.

Establishment of F508del CFTR rescue following PXD-101, LBH-589 or FK-228 treatment. (A) Quantification of CFTR mRNA level following treatment of CFBE-F508del cells with PXD-101, LBH-589 or FK-228 after 2, 6, 12 and 24 h. mRNA was standardized by quantification of GUS mRNA, and all values were expressed relative to GUS (mean ± SEM, n ≥ 3). (B, C & D) Immunoblot analysis of CFTR expression following treatment of CFBE-F508del cells with 2 μm PXD-101, 10 nm LBH-589 and 5 nm FK-228, respectively.

To address if the protein expression levels tracked with changes in mRNA levels, we next monitored the changes in F508del CFTR protein levels over the first 12 h of exposure to PXD-101, LBH-589 and FK-228 for PXD-101. We observed no changes in CFTR mRNA level in the first 6 h of exposure (Fig. 2A); however, we do detect changes in the protein levels of F508del CFTR starting as early as 2 h and continuing to increase up to 24 h (Fig. 2B & Supplementary Material, Fig. S2A). Treatment of CFBE-F508del cells with LBH-589 and FK-228 also did not induce statistically significant changes in the mRNA levels of F508del CFTR in the first 12 h (Fig. 2A) but did cause an increase in the protein levels of F508del CFTR (Fig. 2C–D & Supplemetary Material, Fig. S2B–C). Interestingly, the altered protein levels seen in response to LBH-589 and FK-228 appear to be biphasic, as we observed a decrease in F508del CFTR protein levels occurring between 6 and 12 h post-treatment (Fig. 2C and D) and returning to elevated levels at 24 h (Fig. 1E and F). These data show that early in the HDACi-dosing period, transcriptional and/or translational changes impact the stability of the F508del variant prior to changes in CFTR transcription itself. Thus, the observed changes are not solely the result of increased CFTR expression. Additionally, we observed that all three HDACi induced a similar 30-fold increase in F508del CFTR protein levels relative to that seen with DiMethyl SulfOxide (DMSO) treatment in CFBE-F508del cells (Fig. 1D–F), yet the mRNA changes induced by PXD-101 (18-fold) are significantly greater than to that seen with either LBH-589 or FK-228 (3-fold), suggesting that other cellular factors are responding to these HDACi to impact the stability and/or folding of the resulting F508del CFTR protein.

Increased levels of CFTR are not necessarily indicative of improved trafficking of CF-causing disease variant (90). We, therefore, performed a more detailed analysis of our data, which revealed that all three HDACi cause a dose-dependent improvement in the level of the band C glycoform (Fig. 1D–F), suggesting that they are providing correction of the trafficking defect associated with F508del CFTR. In order to assess if the HDACi treatment of CFBE-F508del cells is increasing the trafficking efficiency of F508del CFTR, we also calculated the ratio of band C obtained relative to the amount of total CFTR (referred to as the C/T ratio), a trafficking index that determines whether the increase in band C is proportional to the increase in the ER pool generated or whether a given treatment has altered the fractional distribution of the CFTR glycoforms.

An analysis of the C/T ratios for the early response of the F508del CFTR protein to PXD-101, LBH-589 and FK-228revealed differing patterns of response to each HDACi. We did observe an increase in the C/T ratio with PXD-101 but only following changes in CFTR mRNA levels (Fig. 2A & Supplementary Material, Fig. S2A). The response to LBH-589 revealed no changes in the C/T ratio in the first 12 h of the dosing regimen (Fig. 2C & Supplementary Material, Fig. S2B), suggesting that the improved trafficking occurred much later in the dosing period (Fig. 1E). Conversely, the treatment with FK-228 induced a biphasic improvement in F508del CFTR trafficking, with a significant increase in C/T observed between the 2 and 7 h mark (Fig. 2D & Supplementary Material, Fig. S2C) and again at the 24 h mark (Fig. 1F). Taken as a whole, these data suggest that the HDACi are in fact not only increasing the level of total F508del CFTR but also improving the trafficking efficiency of this CF-causing variant.

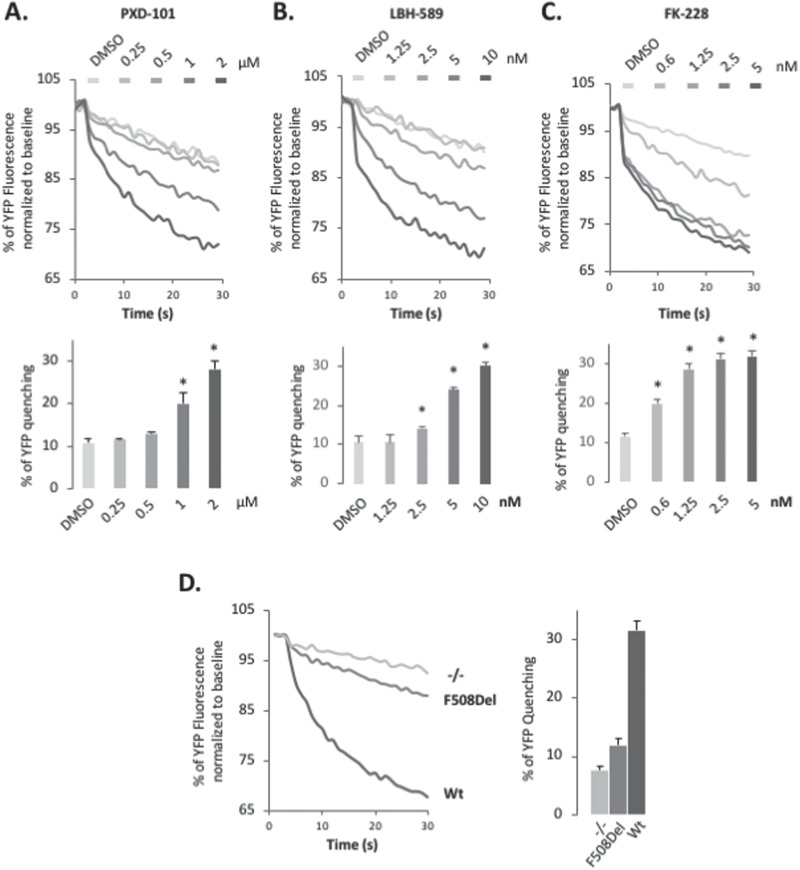

HDACi restore a functional F508del CFTR at cell surface

We next determined if the increased band C fraction represented a functional cell surface-localized chloride channel. In order to assess the functional status of F508del CFTR in CFBE-F508del cells treated with PXD-101, LBH-589 or FK-228, we used CFBE-F508del cells stably expressing the halide-sensitive YFP-H148Q/I152L, a yellow fluorescent protein (YFP) variant whose fluorescence can be quenched in response to iodide influx entering the cell through a functional, cell surface localized CFTR channel (91). Treatment with the PXD-101, LBH-589 or FK-228 caused a dose-dependent increase in YFP quenching in CFBE-F508del cells (Fig. 3A–C) at the same doses where we observed correction of the trafficking defect of F508del (Fig. 1D–F). CFBE-F508del cells treated with 2 μm PXD-101, 10 nm LBH-589 and 1.25 nm FK-228 produced similar level of YFP quenching to that seen in wild-type (WT) CFTR-expressing CFBE-F508del cells (Fig. 3D (WT activity)). This result indicates that the HDACi-corrected F508del CFTR is functional, and the amount of F508del CFTR found at the cell surface is sufficient to restore WT-like activity in CFBE-F508del cells.

Figure 3.

PXD-101, LBH-589 & FK-228 rescue F508del CFTR function in F508del CFBE-F508del. Representative Fluorescent Imaging Plate Reader traces (upper) and quantification (lower) of YFP-quenching following treatment of CFBE-F508del-YFP cells with different concentrations of PXD-101 (A), LBH-589 (B) and FK-228 (C). Data are presented as % relative to baseline (mean ± SEM, n ≥ 3). In all panels, * indicates significant differences (P < 0.05) relative to DMSO treatment as determined by two-tailed t-test. (D) Representative FLIPR traces (left) and quantification (right) of YFP-quenching of CFBE-YFP, CFBE-F508del-YFP and CFBE-Wt-YFP cells. Data are presented as % relative to baseline (mean ± SEM, n ≥ 3).

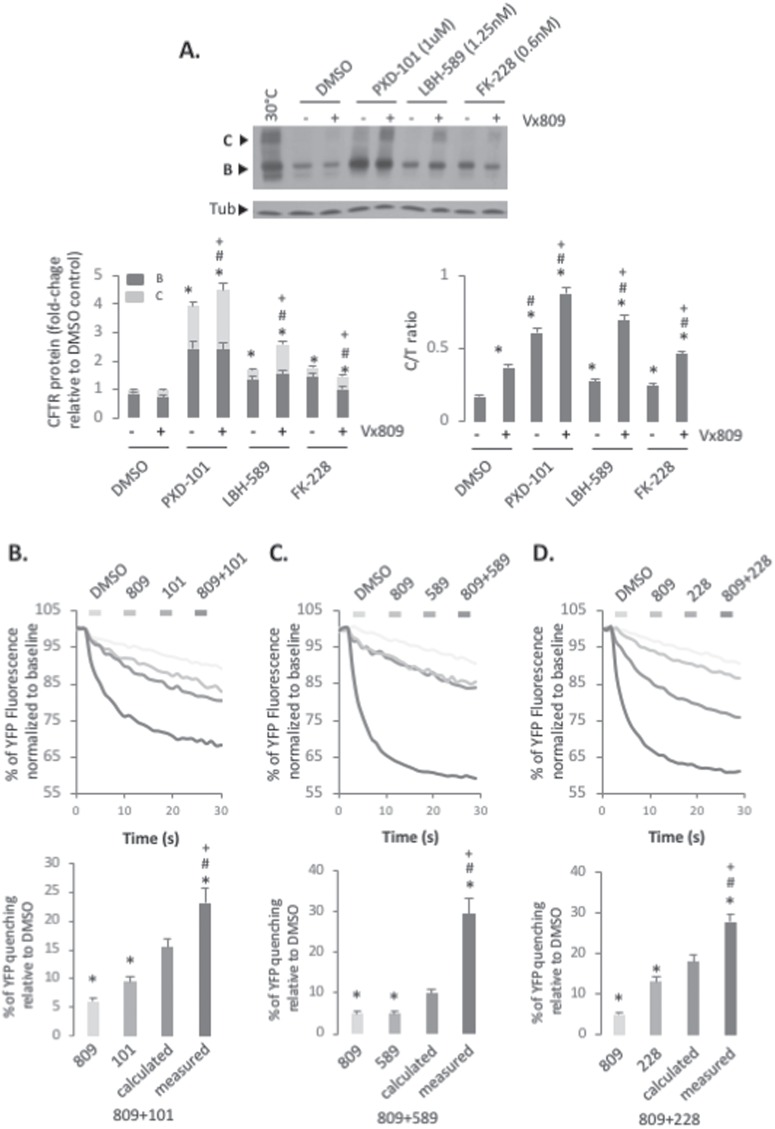

HDACi synergize with Vx809 to correct F508del CFTR

While numerous efforts have been made to identify small molecule correctors of the F508del variant of CFTR, the best characterized is Lumacaftor (Vx809) (15,16). Treatment of CFBE-F508del cells with Vx809 resulted in a 2-fold increase in the C/T ratio of F508del CFTR without causing a global increase in total F508del CFTR protein level (Fig. 4A). As expected, the Vx809-mediated correction of the trafficking defect of F508del CFTR correlated with a very modest 50% increase over the basal channel activity seen in F508del-expressing cells (Fig. 4B–D).

Figure 4.

Synergistic effect of PXD-101, LBH-589 or FK-228 in combination with Vx809. (A) Immunoblot analysis (upper) and quantification (lower) of CFTR expression following treatment of CFBE-F508del cells with 1 μm of PXD-101, 1.25 nm LBH-589 or 0.6 nm FK-228 with or without 3 μm of Vx809. Data are presented as fold change relative to DMSO treatment (lower left) or as a % of C/T ratio (mean ± SEM, n ≥ 3) (lower right). Representative FLIPR traces (upper) and quantification (lower) of YFP-quenching following treatment of CFBE-F508del-YFP cells with 1 μm of PXD-101 (B), 1.25 nm LBH-589 (C) or 0.6 nm FK-228 (D) with or without 3 μm of Vx809. Data are presented as % relative to DMSO (mean ± SEM, n ≥ 3). A calculated additive effect is shown next to the measured combinatorial effect. Abbreviations: 809 (Vx809), 101 (PXD-101), 589 (LBH-589) and 228 (FK-228). In all panels, * and # indicate significant differences (P < 0.05) relative to DMSO and Vx809 treatment, respectively, as determined by two-tailed t-test. + indicates significant difference between the same HDACi treatment with or without Vx809.

The inability of Vx809 to provide statistically significant improvement in patients homozygous for the F508del variant initially spelled failure for this drug (92); however, recent efforts have shown clinical benefit of Vx809 when combined with the FDA-approved small molecule potentiator Ivacaftor (Vx770) in patients carrying at least one F508del allele (93–95) in the form of Orkambi and, more recently, as the improved Lumacaftor scaffold Tezacaftor (96). These data highlight that Vx809, while able to weakly correct the trafficking defect associated with F508del, requires additional ‘help’ to overcome the threshold level of PM-resident F508del to achieve global improvement in cellular chloride channel activity or to potentiate the corrected channel localized in the PM.

In light of these observations, we investigated the effect of combining Vx809 with PXD-101, LBH-589 or FK-228 on F508del CFTR. Considering the potency of the HDACi at maximal dosing (Fig. 1D–F), we utilized doses of PXD-101 (1 μm), LBH-589 (2.5 nm) and FK-228 (0.6 nm), where the corrective benefit was just beginning to be observed to allow for potential additive or synergistic effects to be detected. When we combined these lower doses of HDACi with a treatment of 3 μm Vx809, we observed an additive effect on the level of band C glycoform observed relative to the effect seen with Vx809, PXD-101, LBH-589 and FK-228 alone (Fig. 4A). The combined treatment of PXD-101 or FK-228 and Vx809 resulted in an additive effect on the trafficking efficiency of F508del CFTR (Fig. 4A). However, combining Vx809 with LBH-589 resulted in a synergistic improvement in the trafficking efficiency of the F508del variant (Fig. 4A).

Given the impact of these combinatorial treatments in improving the level of band C correction for the F508del variant, we next addressed the functionality of the accumulated band C using the YFP-quenching assay. We observed a synergistic improvement in the amount of functional F508del CFTR in cells treated with Vx809 in combination with PXD-101, LBH-589 and FK-228, compared to that seen with any of the treatments alone (Fig. 4B–D). Interestingly, we observed a greater increase in F508del activity in cells treated with Vx809 combined with either LBH-589 or FK-228 than with PXD-101 (Fig. 4B–D) despite detecting a more pronounced increase in total CFTR and band C with the PXD-101/Vx809 combination treatment than with the former two combinations (Fig. 4A). Additionally, we observed additivity in the trafficking by combining Vx809 with either PXD-101 or FK-228, yet observed synergistic increases in activity of the corrected F508del fraction, suggesting that the combinatorial treatments are altering the channel properties of the F508del variant such that the measurable activity is no longer a direct correlation of its band C expression. These results suggest that the combined treatment with LBH-589 and/or FK-228 with Vx809 provides a more effective improvement in F508del CFTR stability, trafficking, folding and/or function than PXD-101.

HDACi rescue F508del CFTR in primary airway cells

While CFBE-F508del cells are a commonly used cellular model to study the folding, trafficking and function of CFTR variants and have proven useful in the identification of small molecule therapeutics and targets to treat CFTR phenotypic defects, they express CFTR from a transgene driven by a viral promoter, which fails to recapitulate CFTR biology and its endogenous promoter activity that are likely to have tissue-specific responses triggering variable levels of expression and/or the maladaptive stress response (MSR) that is known to contribute to the etiology of disease and its corrective potential through proteostasis modulation (42). Consistent with this view, a recent report indicated that Vorinostat cannot correct nasal epithelial cell conductance when placed in transwell culture, conditions that recapitulate the nasal respiratory environment (82).

In order to address the potential therapeutic benefit of PXD-101, LBH-589 and FK-228 in correcting the defects associated with the more native state of the F508del variant in a lung-like polarized environment, we tested their ability to provide functional correction of endogenously expressed F508del CFTR in differentiated primary human bronchial airway cells (hBE) isolated from the lung of a CF patient homozygous for the F508del mutation using Transwell culture. The treatment of hBE cells with Vx809 results in a modest 25% increase in the band B glycoform of F508del CFTR, as well as a 300% increase in the post-ER band C fraction, confirming the ability of Vx809 to improve the trafficking of F508del CFTR (Fig. 5A). The Vx809-corrected band C fraction represents a functional F508del CFTR chloride channel as we observe a 3.5-fold increase in the forskolin (Fsk)- and Genistein (Gen)-stimulated short-circuit current (Isc) measurements in hBE cells (Fig. 5B–D and F). Following treatment with Vx809, the channel activity reaches a level of 16.2 μAmp/cm2 a level, representing ~25% of WT channel activity.

Figure 5.

Impact of PXD-101, LBH-589 or FK-228 alone or in combination with Vx809 on F508del CFTR in hBE airway cells homozygous for F508del. (A) Immunoblot analysis (upper) and quantification (lower) of CFTR expression following treatment of F508del/F508del hBE primary cells with 2 μm of PXD-101, 5 nm LBH-589 or 5 nm FK-228 with or without 3 μm of Vx809. Data are presented as fold change relative to DMSO treatment (lower left) or as a % of C/T ratio (mean ± SEM, n ≥ 3) (lower right). Representative short-circuit current (Isc) traces for F508del/F508del hBE following treatment with 2 μm PXD-101 (B), 5 nm LBH-589 (C) and 5 nm FK-228 (D), with or without 3 μm of Vx809. Quantification of Isc for F508del/F508del hBE following treatment with 2 μm PXD-101, 5 nm LBH-589 and 5 nm FK-228 without (E) or with (F) 3 μm of Vx809, respectively (mean ± SEM, n ≥ 3). Abbreviations: 809 (Vx809), 101 (PXD-101), 589 (LBH-589) and 228 (FK-228). In all panels, * and # indicate significant differences (P < 0.05) relative to DMSO and Vx809 treatment, respectively, as determined by two-tailed t-test.

Both LBH-589 and FK-228 induced a stabilization of the band B pool and improved trafficking to band C (Fig. 5A). The increase in the post-ER pool of F508del CFTR induced by LBH-589 and FK-228 represented functional chloride channels as determined by Isc measurements, where we observed an ~50% and 25% increase in the basal channel activity, respectively. These effects significantly impact the effect of Vx809. HDACi-mediated stabilization of CFTR further improved the Vx809 sensitive trafficking of F508del CFTR, leading to a statistically significant improvement in the C/T trafficking index (Fig. 5A). Moreover, combining HDACi and Vx809 in the hBE cell model improved the cell surface channel activity seen with Vx809 alone, leading to correction of the F508del CFTR functional defect to a level representing 37% and 33% of WT CFTR channel activity (Fig. 5C–F), a level considered to provide significant benefit in the clinic (97,98). Surprisingly, and in contrast to the observations made in CFBE-F508del cells, PXD-101 treatment of hBE cells resulted in a destabilization of the F508del CFTR protein, which could not be overcome by combining the treatment with Vx809 (Fig. 5A). Measurement of Isc for hBE cells treated with PXD-101, either alone or in combination with Vx809, revealed a complete loss of Fsk/Gen-stimulated chloride channel activity (Fig. 5B, E and F). These data support the potential therapeutic benefit of LBH-589 and FK-228 in combination with small molecule correctors such as Vx809/Lumacaftor, the established clinical practice when used in combination with Ivacaftor (Orkambi). The differential effect of PDX-101 in CFBE-508del compared to primary hBE suggests that both cell- and/or tissue-specific epigenetic states may influence the impact of HDACi on disease.

HDACi rescue CFTR trafficking and function through multiple pathways

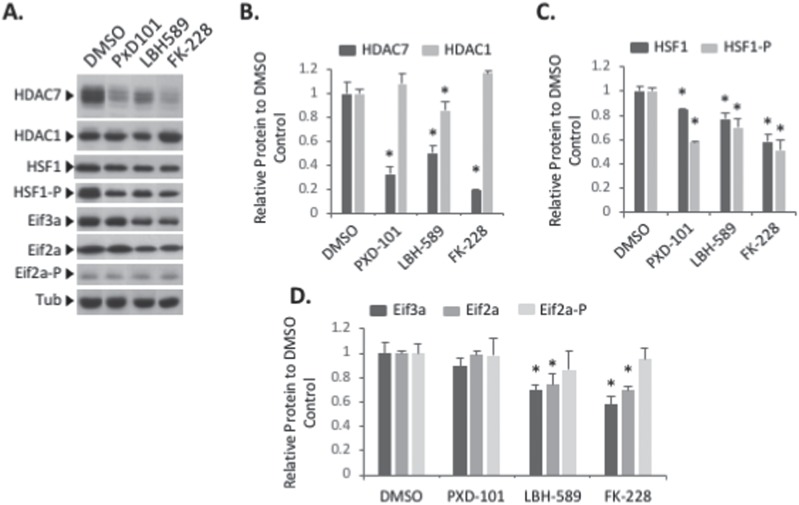

To provide insight into the mechanistic impact of HDACi on proteostatic environment of hBE cells, we performed a western blot analysis to monitor any changes in expression or activation of markers of a number of known CF-linked cellular pathways. These included the expression level of HDAC7, previously shown to be affected by HDACi treatment (74,99) and the eukaryotic translation Initiation Factor 3a (eIF3a), whose silencing has been shown to mediate significant correction of F508del-CFTR based on our recent proteomic and molecular analysis (100,101). Additionally, we monitored the expression and phosphorylation status of eIF2α and HSF1, markers of the UPR and HSR pathways, respectively, which have been shown to be chronically activated in F508del-expressing cells and impact the severity of the disease state (42).

An analysis revealed that all three HDACi resulted in a significant reduction in the expression of HDAC7 without affecting HDAC1 (Fig. 6A and B), a result that is consistent with the ability of the HDACi Vorinostat to selectively reduce the expression of this HDAC7 (74,99). An analysis of the impact of these compounds on stress-related pathways revealed that none of the compounds altered the phosphorylation state of eIF2α (Fig. 6A and D), indicating that they are not activating the Protein kinase RNA-like ER kinase (PERK) arm of the UPR. However, we did observe a reduction in the levels of phospho-HSF1 (Fig. 6A and C), suggesting that they are all providing a modest relief for the MSR characteristic of F508del expressing cells (42). Given the importance of phosphorylation in the function of both HSF1 and HDAC7, an analysis of the impact of siHDAC7 and siHSF1 revealed no reciprocal changes in their expression or phosphorylation state (Supplementary Material, Fig. S3), suggesting that the ability of HDACi to modulate the expression and/or functional state of HDAC7 and/or HSF1 could reflect independent corrective cellular states.

Figure 6.

HDACi rescue CFTR trafficking and function through multiple pathways. Immunoblot analysis (A) and quantification of HDAC7, HDAC1 (B), HSF1, HSF1 phosphorylated (C), Eif3a, Eif2a and Eif2a phosphorylated (D) expression following treatment of F508del/F508del hBE primary cells with 2 μm of PXD-101, 5 nm LBH-589 or 5 nm FK-228. Data are presented as fold change relative to DMSO treatment (mean ± SEM, n ≥ 3). In all panels, * indicate significant differences (P < 0.05) relative to DMSO treatment, as determined by two-tailed t-test.

An analysis of the expression of translational components revealed changes that correlated with chloride channel restoration in hBE cells. Specifically, we observed that LBH589 and FK-228 treatments caused a reduction in the expression of the translation initiation components eIF3a (Fig. 6A and D), a core component of the eIF3 translation initiation complex, as well as eIF2α (Fig. 6A and D), which mediates the delivery of the tRNAMet to the 40S ribosome. We have previously shown that the silencing of eIF3a can mediate the correction of F508del-CFTR through modulation of the translational rate of CFTR, leading to correction of the trafficking defect associated with multiple CF-causing variants (101). These effects were not observed with PXD-101. Analysis of the impact of silencing HDAC7 and HSF1 revealed no changes in the expression of either of these translation initiation components (Supplementary Material, Fig. S3), suggesting that LBH589 and FK-228 effects are not solely driven by changing the cellular level of HDAC7 and/or HSF1.

Taken as a whole, these results demonstrate that the rescue of F508del-CFTR by HDACi may operate through multiple transcriptional and proteostatic pathways that are sensitive to changes in the expression of HDAC7 (74,99) and translational components (101), culminating in the abrogation of MSR stress (42).

LBH-589 and FK-228 modulate CFTR2 variant stability, trafficking and activity

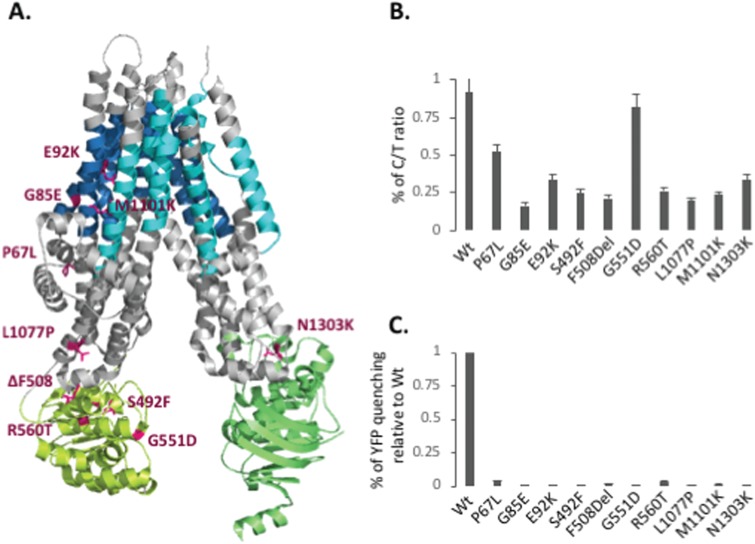

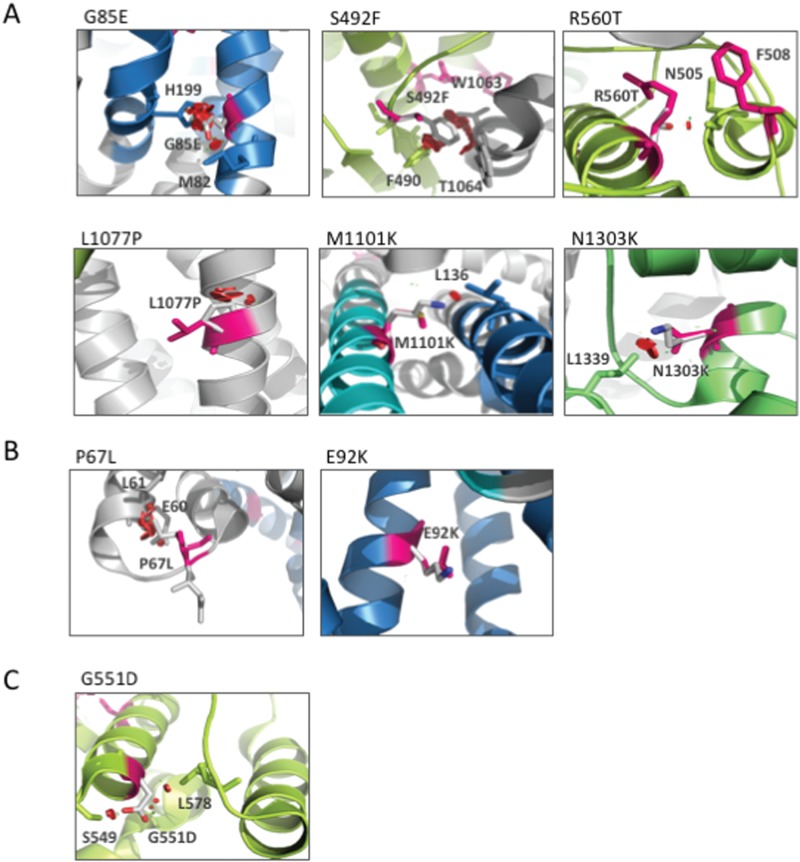

While F508del CFTR is the most common CF-causing mutation, there are currently more than 2000 disease-associated variants reported in the clinic (www.genet.sickkids.on.ca and www.CFTR2.org) (4). A large-scale study, which examined the most common mutations (allele frequency ≥ 0.01%) representing ~96% of the CF population, identified 67 missense CF-causing mutations, with nearly half of these variants exhibiting a trafficking defect (Class II). We characterized the impact of HDACi on nine Class II variants: P67L, G85E, E92K, S492F, F508del, R560T, L1077P, M1101K and N1303K, as well as the Class III G551D variant, the third most common CF-causing mutation in the patient population (6), which exhibits WT-like trafficking but is characterized by a gating defect. The Class II mutations are distributed throughout the CFTR polypeptide (Fig. 7A) and predicted to induce different structural changes and their respective phenotypic responses (2).

Figure 7.

Characterization of CFTR2 variant trafficking. (A) Cryo-EM model of human CFTR (112) (blue: TMs of MSD1, yellow-green: NBD1, cyan: TMs of MSD2 and green: NBD2) showing the positions of the selected CFTR2 mutations in Magenta. (B) Quantification of C/T ratios following adenovirus transduction of CFTR2 variants into CFBE cells. C/T ratios are expressed as a % (mean ± SEM, n ≥ 3). (C) Quantification of YFP-quenching following adenovirus transduction of CFTR2 variants into CFBE-YFP cells. Data are presented as % normalized to WT (mean ± SEM, n ≥ 3).

To perform a side-by-side comparison of the different CF variants, we utilized parental CFBE cells, which are genotypically F508del/F508del, and do not express detectable CFTR mRNA or protein. The choice of these CFBE null cell lines provides a cellular environment optimized for the expression, folding, trafficking and functional regulation of CFTR (100). To characterize the 10 variants described above in response to HDACi in the presence or absence of Lumacaftor, we transduced the CFBE null cells with adenoviral particles carrying the different CFTR variant cDNAs. While the transient expression level of the F508del variant in CFBE null cells was much lower than seen in CFBE-F508del stable cell lines, the stability and trafficking of the variants observed is consistent with what has been previously reported for these variants (102,103) (Figs 7B and 8).

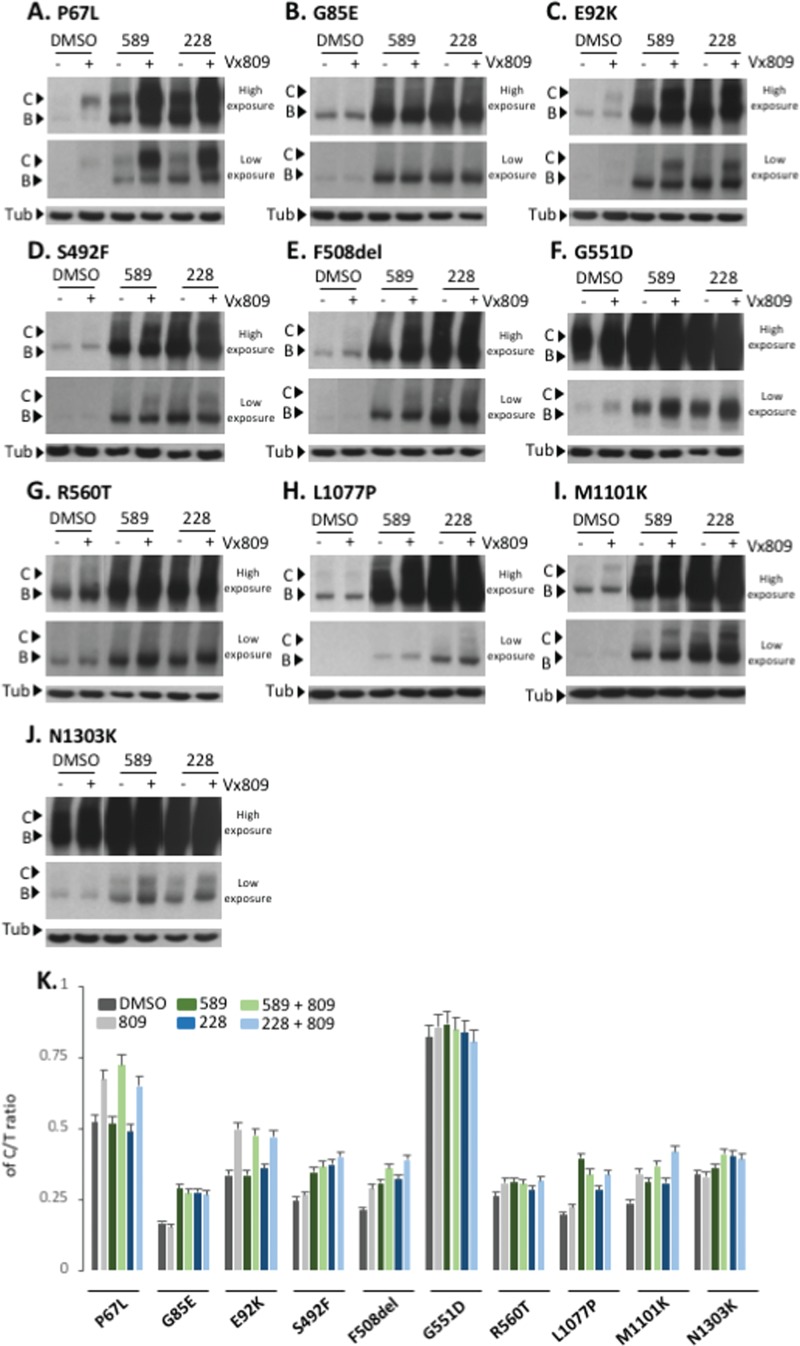

Using 5 nm LBH-589 and 2.5 nm FK-228, doses shown to provide maximal correction of F508del CFTR in CFBE-F508del cells, we observed a significant improvement in the stabilization of band B for all CFTR2 variants tested as well as correction to band C (Fig. 8A–K). We also observed improvement in the trafficking efficiency for all variants tested (Fig. 8A–K). We observed that P67L, E92K, F508del and M1101K-CFTR modestly responded to the Vx809 treatment (Fig. 8A–J). The combined treatment of Vx809 with LBH-589 or FK-228 results in an HDACi-mediated increase in the expression of P67L- and E92K-CFTR whose trafficking can subsequently be corrected by Vx809 (Fig. 8A and C) culminating in an increased C/T ratio relative to that seen with either HDACi treatment alone (Fig. 8K). Not all variants responded equally as other tested variants failed to show an additive or synergistic effect in response to the combined treatment of HDACi and Vx809, possibly reflecting the impact of LBH-589 and FK-228, whose effects alone would mask the weak impact of Vx809 observed when treated alone. Interestingly, we observed that both LBH-589 and FK-228 increased the amount of G551D band C without affecting the C/T trafficking index, consistent with the observation that CFTR variants that do not exhibit trafficking defects already exhibit efficient ER export.

Figure 8.

Effect of LBH-589 or FK-228 alone or in combination with Vx809 on CFTR2 variant trafficking. (A to J) Immunoblot analysis of CFTR expression following treatment of CFBE transduced cells with 5 nm LBH-589 or 2.5 nm FK-228 with or without 3 μm Vx809 for P67L, G85E, E92K, S492F, F508del, G551D, R560T, L1077P, M1101K and N1303K variants, respectively. (K) Quantification of the C/T ratio for each of the 10 variants expressed as a % (mean ± SEM, n ≥ 3). Abbreviations: 589 (LBH-589) and 228 (FK-228).

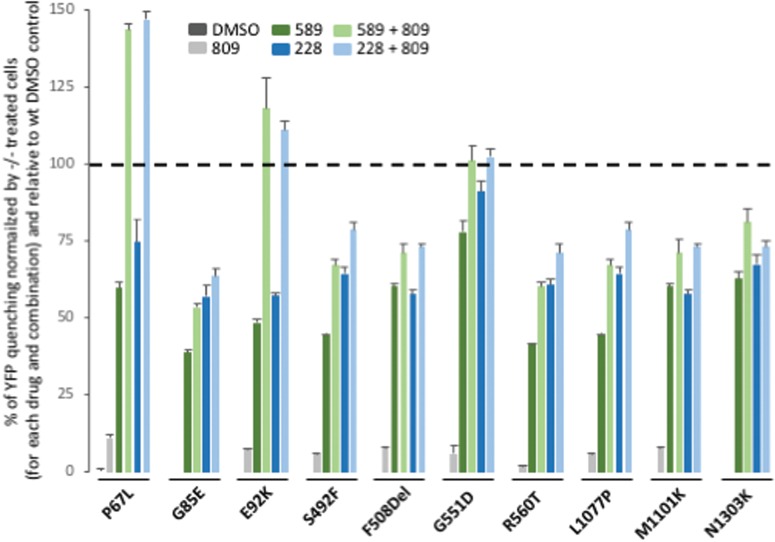

While LBH-589 and FK-228 did not improve the C/T ratio for all variants tested, they did exhibit the ability to increase the amount of band C for all variants. To address if the corrected fraction of band C represented a functional pool of CFTR, we used the YFP quenching assay in transduced CFBE null cells stably expressing the YFP-H148Q/I152L variant. LBH-589 and FK-228 were able to restore activity to a level exceeding 30% of WT CFTR YFP quenching for all CFTR2 variants tested (Fig. 9). When we combined the HDACi treatment with Vx809, we further improved the activity of all variants. Two conclusions are evident from these data. First, the combined treatment of HDACi + Vx809 for the P67L and E92K resulted in functional correction of these CF-causing variants to levels that exceed the activity seen with WT CFTR, suggesting that the HDACi-responsive modulation appear to be particularly permissive for these variants; second, the HDACi treatment of the G551D variant corrected the functional defect associated with this Class III variant to levels approaching to that seen with WT CFTR.

Figure 9.

Effect of LBH-589 or FK-228 alone or in combination with Vx809 on CFTR2 variant activity. Quantification of YFP-quenching following treatment with 5 nm LBH-589 or 2.5 nm FK-228 with or without 3 um Vx809 of CFBE-YFP transduced cells with P67L, G85E, E92K, S492F, F508del, G551D, R560T, L1077P, M1101K and N1303K variants. Data are presented as a % of YFP quenching normalized by CFBE-YFP identically treated cells and relative to CFBE-YFP cells transduced with WT CFTR and treated with DMSO.

Taken as a whole, these data indicate that the HDACi-mediated correction of the F508del variant can be extended to other ER-restricted Class II and III variants. These results suggest that HDACi-mediated changes could include alterations in the CFTR interaction network that impact the protein both in its early biogenesis as well as at the PM where membrane localization, internalization and channel gating and function defects are potentially responsive to HDAC sensitive events.

Discussion

There are a number of reports highlighting the beneficial impact of HDACi on abrogating the expression and aggregation of disease-causing protein variants (reviewed in 75,104), including the impact of Vorinostat on F508del-CFTR (74). In the present study, we provide new evidence showing that LBH-589 and FK-228 can correct the trafficking defect associated with the F508del variant of CFTR, leading to restoration of a functional chloride channel at the cell surface of both CFBE-F508del and primary hBE cells at nm levels. Importantly, the HDACi-mediated correction of F508del-CFTR can synergize with the small molecule corrector, Vx809, to provide functional correction of this common CF-causing variant to a level approaching 40% of WT CFTR, a value that is predicted to provide significant therapeutic benefit in the clinic (97,98). Interestingly, while the HDACi PXD-101 showed corrector capability in the CFBE-F508del model, it completely destabilized F508del CFTR in hBE cells, an effect which could not be overcome by Vx809. These results suggest that this HDACi influences a different collection of HDAC activities in hBE cells compared to those seen in response to LBH-589 and FK-228 in CFBE cells, likely reflecting their unique transcriptional and/or proteostasis programs.

We found that the LBH589- and FK-228-mediated rescue of F508del CFTR in hBE occurs via the modulation of multiple non-overlapping CF-linked pathways (42,72,74,101) that may include the downregulation of the expression of HDAC7, which initiates an altered epigenetic program to create a more permissive environment for the trafficking of CF-causing variants, and abrogation of the misfolding stress associated MSR (42). Specifically, LBH589 and FK-228 modulated the expression of the translation initiation components, eIF3a and eIF2α, which are critical for the formation of a functional 43S preinitiation complex (PIC) (101,105) and elongation (105,106), respectively, factors that we and others have been shown to mediate the correction of phenotypic defects associated with multiple CFTR variants. Therefore, we posit that it is the additive and/or synergistic effect of multiple CF-linked processing and regulatory pathways that mechanistically mediate the corrective properties of FK-228 and LBH589, changes that will now need to be explored in further depth to understand clinical relevancy.

Strikingly, the corrective properties of LBH-589 and FK-228 extend beyond the ability to correct F508del CFTR, as we show that they can also provide functional correction of other Class II and III variants, both alone and in combination with Vx809, suggesting a more generalized mechanism of correction of CFTR variants. Although we noted correction of the trafficking defect associated with multiple variants, we observed a differential effect on their functional correction. From the small cohort of variants tested, we identified three clusters of responses to HDACi: cluster A—Class II variants exhibiting a modest functional correction, cluster B—Class II variants exceeding WT activity and cluster C—correction of the representative Class III variant (Fig. 10).

Figure 10.

Structural modeling of CFTR2 variants. (A to C) Cryo-EM model of CFTR2 variants using PyMOL software (Materials and Methods). Red shows impact of the mutant residue on other residues. Rotomers are predicted to minimize impact against other residues. (A) Cluster A: G85E, S492F, G551D, R560T, L1077P, M1101K and N1303K. (B) Cluster B: P67L and E92K variants. (C) Cluster C: G551D variant.

Cluster A variants include G85E, S492F, F508Del, R560T, L1077P, M1101K and N1303K (Fig. 10A), which exhibit a modest correction in response to HDACi. The G85E variant, which is localized in TMD1 (Fig. 10A), represents the least responsive variant tested. The substitution of glycine for glutamic acid at this position drastically impacts CFTR structure both locally, given the interaction of G85 with M82, and globally, given the interaction of G85 with H199. These data are in agreement with the observations that G85E is a severe Class II variant disrupting the ER targeting, integration and topology of the TMD1 (107,108), which cannot be overcome with low temperature nor with well-established correctors such as C4, C18 and Vx809 (103). While the impact of Vx809 alone is always modest, we observed a synergistic correction of the variants in response to HDACi + Vx809, an effect that is most pronounced with LBH-589. These data suggest that HDACis are able to make adjustments to the plasticity of the cellular environment, presumably influenced by either genomic or proteomic epigenetic changes (74), which allow for a global correction of misfolding events contributing to the Class II phenotype. Because the severity of the defect seen with specific variants generates an impediment to HDACi correction, we suggest that these variants may lie outside the SCV tolerance set-point for functional structure correction as predicted by VSP (2).

The most responsive variant is the cluster B P67L variant, which is localized in the N-terminal region of the CFTR polypeptide near the TMD1 (Fig. 10B). An in silico analysis of the impact of substituting the proline at position 67 with a leucine (Fig. 10B) suggests that the mutation would impact the structure of CFTR due to a predicted clash of L67 with both E60 and L61, thereby limiting flexibility that may be essential in generating the functional fold. The P67L variant was initially classified as a Class IV gating variant (109), consistent with the fact that it exhibited a significant trafficking at steady state. However, recent evidence has shown that the P67L mutation is in fact a Class II variant exhibiting weak trafficking, yet is highly responsive to Vx809 (110). Our data now reveal that P67L CFTR potently synergizes with LBH-589 and FK-228 to restore activity to a level to that seen with the WT. Considering that the P67L variant is characterized by an elevated C/T ratio, we would predict that LBH-589 and FK-228 alone or in combination with Vx809 could provide significant benefit to 10 other variants that achieve a C/T ratio of at least 30% including R74W,R75Q, I336K, S341P, R347P, S549R, D579G, D614G, S945L and R1070W (4). The second most responsive variant to HDACi is the cluster B E92K variant that shows a modest trafficking defect, localizes to the first membrane helix of the of the TMD1 (Fig. 10B). Molecular dynamic analysis of the impact of substituting the glutamic acid at position 92 with a lysine (Fig. 10B) suggests that the mutation would not severely impact the structure of CFTR (15), likely accounting for its high responsiveness to HDACi and Vx809. We also observed that HDACi treatment was sufficient to restore activity to the Class C variant G551D CFTR (Fig. 10C) found at the cell surface to WT levels, suggesting that the epigenetic changes generated by LBH-589 and FK-228 are able to restore key interactions of the G551D polypeptide with the gating machinery controlling channel conductance. Overall, the HDACi-mediated response of cluster B and C variants (Fig. 10B) compared to cluster A (Fig. 10A) suggests that cluster B/C mutations present a less severe disruption of the CFTR 3D structure, making them more sensitive to epigenetic changes that are incurred in response to alterations in the cellular acetylation status mediated through HDACis.

In general, we now appreciate that HDACi alter the acetylation equilibrium of both histones and non-histone proteins, an effect highlighted by the dynamic acetylome, which included proteostasis components (1,25–31) regulating the central HSR (32) and UPR (33,34), programs responsible for recovery from protein-folding stress such as the MSR caused by CFTR misfolded variants (24,35–41). By globally adjusting the expression and activation state of multiple cellular components, HDACi are modulating multiple independent pathways that additively or synergistically create a more permissive folding environment. Indeed, a number of approaches have now demonstrated the plasticity of the cellular environment in human disease. For example, LBH-589 has been reported to rescue sickle cell disease (105), and its clinical benefits are under investigation. While the toxicity of these compounds is well documented, largely from the perspective of killing cancer cells, their role in modulating development, aging and responses to stress highlights the importance of HDAC to differentially program the cell for improved function. Moreover, they have been shown to be well tolerated by patients over many years even at doses that exceed those at which we see striking functional correction of multiple CF-causing variants. We suggest HDACi represent an untapped resource to modulate the overall plasticity of the cellular environment through SCV principles (2), a new way of thinking about sequence-to-function-to-structure relationships that could provide significant clinical insights for a broad spectrum of CF and other misfolding challenges, now recognized to be an important consequence of sequence variation and diversity in the human population (2,111).

Materials and Methods

Cell culture and treatment

Null (−/−) CFBE, CFBE-F508del expressing F508del CFTR or WT CFTR (CFBE-WT) were cultured as previously described (74). CFBE, 2CFBE-F508del and CFBE-WT, were stably transfected with pcDNA3.1 containing YFP-H148Q (kindly provided by Dr L. Galietta, Telethon University for Genetics and Medicine, Puzzuoli, IT) using Lipofectamine 3000 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. CFBE-YFP, CFBE-F508del-YFP and CFBE-WT-YFP were selected with 0.75 mg/ml G418 and then sorted using Fluorescence-Activated Cell Sorter (FACS). The stable cell lines could be passed at least 15 times without a decrease in YFP-H148Q fluorescence. CFBE-YFP, CFBE-F508del-YFP and CFBE-WT-YFP were cultured in the same media as the YFP non-expressing cells with addition of 0.75 mg/ml G418. Cells were treated at the indicated concentration of belinostat (Toronto Research Chemicals, Inc., Canada), panobinostat (LC Laboratories, Woburn, MA) and romidepsin (Toronto Research Chemicals, Inc., Canada) in complete growth media and incubated at 37°C, 5% CO2 for 24 h. 3 μM of Vx809 was used where indicated.

LDH cytotoxicity assay

Following the treatment of CFBE-F508del with 10 pm to 10 μM PXD-101, LBH-589 or FK-228, cytotoxicity of the three compounds were monitored following the manufacturer instructions of the LDH cytotoxicity assay kit (Pierce, Appleton, WI).

Adenoviral transduction

CFTR2 variants coding sequence were Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) amplified using forward (TCATGGTACCATGCAGAGGTCGCCT) and reverse (GCTGCTCGAGCTAAGCGTAATCTGGAACATCGTATGGGTAAAGCCTTGTATCTTG) primers introducing a Human influenza hemagglutinin (HA)-tag at the end of the sequence and pBl-CMV2-CFTR plasmids DNA (kindly provided by P. Thomas, University of Texas Southwestern) as template. The PCR fragments were digested with KpnI and XhoI and cloned into pENTR1A shuttle vector. pENTR1A-CFTR plasmids were sequenced and recombined into pAD-CMV-V5-DEST using LR-clonase II (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). pAD-CMV-CFTR plasmid were then sent to ViraQuest for adenovirus production (42,100). 80% confluent CFBE-F508del were transduced for 5 h in opti-Minimum Essential Medium (opti-MEM) in the presence of 10 μg/ml of polybrene (EMD Millipore Corp., Burlington, MA) with adenovirus carrying CFTR at a multiplicity of infection of 200. Then cells were washed with Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS) and fed with regular medium for 24 h prior to treatment. Kinetics of CFTR mRNA and protein level for WT and F508del were performed to optimize the efficiency of CFTR expression. To ensure a similar mRNA level of the different CFTR2 variant after adenovirus transduction, qRT-PCR was performed with no significant differences detected.

qRT-PCR

quantitative Reverse Transcription PCR (qRT-PCR) was performed using the iScript One-Step RT-PCR kit with SYBR green (BioRad, Hercules, CA). RNA was standardized by quantification of beta-glucuronidase (GUS) mRNA, and all values were expressed relative to GUS. Forward (GTGGCTGCTTCTTTGGTTGT) and reverse (CGAACTGCTGCTGGTGATAA) primers were used as indicated.

Immunoblotting

CFBE-F508del cells lysates were prepared in 50 mm Tris–HCl, 150 mm NaCl, 1% Triton X-100, and 20 μg of total protein were separated on a 7% SDS-PAGE. Proteins were transferred to nitrocellulose and probed with 3G11 antibody for CFTR detection and rat secondary antibody and detected by chemiluminescence. The same procedure was followed for primary F508del/F508del hBE cells lysate with modifications. Benzonaze was added to the lysate buffer at a final concentration of 0.025 units/μl, and 40 μg instead of 20 μg of total protein were used for SDS-PAGE. HDAC7, HDAC1, HSF1, HSF1 phosphorylated, Eif3a, Eif2a and Eif2a phosphorylated were detected with Ab12174 (Abcam, United Kingdom), Ab7028 (Abcam, United Kingdom), Ab52757 (Abcam, United Kingdom), Ab76076 (Abcam, United Kingdom), Ab86149 (Abcam, United Kingdom), 9722S (Cell Signaling, Danvers, MA) and 44-728G (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) antibodies, respectively, probed with their specific secondary antibodies and detected by chemiluminescence.

siRNA-mediated silencing of HDACs and HSF1

Primary F508del/F508del hBE cells were plated in 12-well dishes and grown to 60–70% confluence. Silencing HDAC1, HDAC7 or HSF1 was performed using 50 nm of validated siRNA for the indicated HDACs and HSF1 (Ambion, Foster City, CA) and RNAi-max (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) as per manufacturer’s directions. Cells were cultured for 5 h in the serum-free opti-MEM containing transfection complexes and subsequently washed and cultured for an addition of 48 h in the presence of growth medium. Then, a second silencing was performed, adding the transfection complexes in opti-MEM on top of growth medium. Cells were incubated overnight and subsequently washed and cultured for an addition of 24 h in the presence of growth medium prior to processing for immunoblot analysis.

YFP quenching assay

CFBE-F508del-YFP were treated with indicated drug. Following treatment, cells were stimulated with a final concentration of 10 μm Fsk and 50 μm Gen for 15 min prior to addition of PBS + NaI (replacement of NaCl with 137 mm NaI). Fluorescence was monitored every second for a total of 30 s (3 s prior to addition of NaI and 27 s after addition of NaI) using a Synergy H1 hybrid reader (BioTek, Winooski, VT). As a negative control, identical experiments were performed with CFBE-YFP cells not expressing F508del CFTR.

Using chamber conductance assay cell culture

Primary F508del/F508del hBE cells were cultured on permeable supports as described previously (42). Short-circuit currents (Isc) were measured as previously described (42).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank P. Thomas (UT Southwestern Medical School) for providing vectors-encoding CFTR2 mutants and Dr L. Galietta (Telethon Institute of Genetics and Medicine, IT) for providing the vector-encoding YFP-H148Q.

Conflict of Interest statement. None declared.

Funding

National Institutes of Health (HL095524 to W.E.B, DK051870 to W.E.B.); Cystic Fibrosis Foundation (CFFT Fellowship to F.A.).

References

- 1. Amaral M.D. and Balch W.E. (2015) Hallmarks of therapeutic management of the cystic fibrosis functional landscape. J. Cyst. Fibros., 14, 687–699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Wang C. and Balch W.E. (2018) Bridging genomics to phenomics at atomic resolution through variation spatial profiling. Cell Rep., 24, 2013–2028e2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Hoffmann N., Lee B., Hentzer M., Rasmussen T.B., Song Z., Johansen H.K., Givskov M. and Høiby N. (2007) Azithromycin blocks quorum sensing and alginate polymer formation and increases the sensitivity to serum and stationary-growth-phase killing of Pseudomonas aeruginosa and attenuates chronic P. aeruginosa lung infection in Cftr−/− mice. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother., 51, 3677–3687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Cutting G.R. (2015) Cystic fibrosis genetics: from molecular understanding to clinical application. Nat. Rev. Genet., 16, 45–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Qu B.-H., Strickland E.H. and Thomas P.J. (1997) Localization and suppression of a kinetic defect in cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator folding. J. Biol. Chem., 272, 15739–15744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Sosnay P.R., Siklosi K.R., Van Goor F., Kaniecki K., Yu H., Sharma N., Ramalho A.S., Amaral M.D., Dorfman R. and Zielenski J. (2013) Defining the disease liability of variants in the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator gene. Nat. Genet., 45, 1160–1167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ahner A., Nakatsukasa K., Zhang H., Frizzell R.A. and Brodsky J.L. (2007) Small heat-shock proteins select deltaF508-CFTR for endoplasmic reticulum-associated degradation. Mol. Biol. Cell, 18, 806–814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Brodsky J.L. and Wojcikiewicz R.J. (2009) Substrate-specific mediators of ER associated degradation (ERAD). Curr. Opin. Cell Biol., 21, 516–521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Gong X., Ahner A., Roldan A., Lukacs G.L., Thibodeau P.H. and Frizzell R.A. (2016) Non-native conformers of cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator NBD1 are recognized by Hsp27 and conjugated to SUMO-2 for degradation. J. Biol. Chem, 291, 2004–2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Saxena A., Banasavadi-Siddegowda Y.K., Fan Y., Bhattacharya S., Roy G., Giovannucci D.R., Frizzell R.A. and Wang X. (2012) Human heat shock protein 105/110kDa (Hsp105/110) regulates biogenesis and quality control of misfolded cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator at multiple levels. J. Biol. Chem., 287, 19158–19170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Sun F., Zhang R., Gong X., Geng X., Drain P.F. and Frizzell R.A. (2006) Derlin-1 promotes the efficient degradation of the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) and CFTR folding mutants. J. Biol. Chem., 281, 36856–36863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Turnbull E.L., Rosser M.F. and Cyr D.M. (2007) The role of the UPS in cystic fibrosis. BMC Biochem ., 8(Suppl. 1), S11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Vembar S.S. and Brodsky J.L. (2008) One step at a time: endoplasmic reticulum-associated degradation. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell. Biol., 9, 944–957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Veit G., Avramescu R.G., Chiang A.N., Houck S.A., Cai Z., Peters K.W., Hong J.S., Pollard H.B., Guggino W.B. and Balch W.E. (2016) From CFTR biology toward combinatorial pharmacotherapy: expanded classification of cystic fibrosis mutations. Mol. Biol. Cell, 27, 424–433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Ren H.Y., Grove D.E., De La Rosa O., Houck S.A., Sopha P., Van Goor F., Hoffman B.J. and Cyr D.M. (2013) VX-809 corrects folding defects in cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator protein through action on membrane-spanning domain 1. Mol. Biol. Cell, 24, 3016–3024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Van Goor F., Hadida S., Grootenhuis P.D., Burton B., Stack J.H., Straley K.S., Decker C.J., Miller M., McCartney J., Olson E.R. et al. (2011) Correction of the F508del-CFTR protein processing defect in vitro by the investigational drug VX-809. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A., 108, 18843–18848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Van Goor F., Hadida S., Grootenhuis P.D., Burton B., Cao D., Neuberger T., Turnbull A., Singh A., Joubran J., Hazlewood A. et al. (2009) Rescue of CF airway epithelial cell function in vitro by a CFTR potentiator, VX-770. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A., 106, 18825–18830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Van Goor F., Yu H., Burton B. and Hoffman B.J. (2014) Effect of ivacaftor on CFTR forms with missense mutations associated with defects in protein processing or function. J. Cyst. Fibros., 13, 29–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Veit G., Avramescu R.G., Perdomo D., Phuan P.W., Bagdany M., Apaja P.M., Borot F., Szollosi D., Wu Y.S., Finkbeiner W.E. et al. (2014) Some gating potentiators, including VX-770, diminish DeltaF508-CFTR functional expression. Sci. Transl. Med., 6, 246ra297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Butler K.V. and Kozikowski A.P. (2008) Chemical origins of isoform selectivity in histone deacetylase inhibitors. Curr. Pharm. Des., 14, 505–528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Hahnen E., Hauke J., Trankle C., Eyupoglu I.Y., Wirth B. and Blumcke I. (2008) Histone deacetylase inhibitors: possible implications for neurodegenerative disorders. Expert Opin. Investig. Drugs, 17, 169–184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Marks P.A. and Breslow R. (2007) Dimethyl sulfoxide to vorinostat: development of this histone deacetylase inhibitor as an anticancer drug. Nat. Biotechnol., 25, 84–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Yoshida M., Kudo N., Kosono S. and Ito A. (2017) Chemical and structural biology of protein lysine deacetylases. Proc. Jpn. Acad. Ser. B Phys. Biol. Sci., 93, 297–321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kronfol M.M., Dozmorov M.G., Huang R., Slattum P.W. and McClay J.L. (2017) The role of epigenomics in personalized medicine. Expert Rev. Precis. Med. Drug Dev., 2, 33–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Balchin D., Hayer-Hartl M. and Hartl F.U. (2016) In vivo aspects of protein folding and quality control. Science, 353, aac4354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Powers E.T. and Balch W.E. (2013) Diversity in the origins of proteostasis networks—a driver for protein function in evolution. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol., 14, 237–248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Balch W.E., Morimoto R.I., Dillin A. and Kelly J.W. (2008) Adapting proteostasis for disease intervention. Science., 319, 916–919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Sala A.J., Bott L.C. and Morimoto R.I. (2017) Shaping proteostasis at the cellular, tissue, and organismal level. J. Cell Biol, 216, 1231–1241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Labbadia J. and Morimoto R.I. (2015) The biology of proteostasis in aging and disease. Annu. Rev. Biochem., 84, 435–464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Klaips C.L., Jayaraj G.G. and Hartl F.U. (2018) Pathways of cellular proteostasis in aging and disease. J. Cell Biol., 217, 51–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Hartl F.U. (2017) Protein misfolding diseases. Annu. Rev. Biochem., 86, 21–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Li J., Labbadia J. and Morimoto R.I. (2017) Rethinking HSF1 in stress, development, and organismal health. Trends Cell Biol., 27, 895–905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Frakes A.E. and Dillin A. (2017) The UPR(ER): sensor and coordinator of organismal homeostasis. Mol. Cell, 66, 761–771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Cao S.S. and Kaufman R.J. (2013) Targeting endoplasmic reticulum stress in metabolic disease. Expert Opin. Ther. Targets, 17, 437–448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Booth L.N. and Brunet A. (2016) The aging epigenome. Mol. Cell, 62, 728–744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Skipper M., Eccleston A., Gray N., Heemels T., Le Bot N., Marte B. and Weiss U. (2015) Presenting the epigenome roadmap. Nature, 518, 313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Dekker J., Belmont A.S., Guttman M., Leshyk V.O., Lis J.T., Lomvardas S., Mirny L.A., O’Shea C.C., Park P.J., Ren B. et al. (2017) The 4D nucleome project. Nature, 549, 219–226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Chen H., Chen J., Muir L.A., Ronquist S., Meixner W., Ljungman M., Ried T., Smale S. and Rajapakse I. (2015) Functional organization of the human 4D Nucleome. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A., 112, 8002–8007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Margueron R., Trojer P. and Reinberg D. (2005) The key to development: interpreting the histone code? Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev., 15, 163–176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Gates L.A., Foulds C.E. and O’Malley B.W. (2017) Histone marks in the ‘driver’s seat’: functional roles in steering the transcription cycle. Trends Biochem. Sci., 42, 977–989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Buschbeck M. and Hake S.B. (2017) Variants of core histones and their roles in cell fate decisions, development and cancer. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol., 18, 299–314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Roth D.M., Hutt D.M., Tong J., Bouchecareilh M., Wang N., Seeley T., Dekkers J.F., Beekman J.M., Garza D., Drew L. et al. (2014) Modulation of the maladaptive stress response to manage diseases of protein folding. PLoS Biol., 12, e1001998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Pipalia N.H., Subramanian K., Mao S., Ralph H., Hutt D.M., Scott S.M., Balch W.E. and Maxfield F.R. (2017) Histone deacetylase inhibitors correct the cholesterol storage defect in most Niemann–Pick C1 mutant cells. J. Lipid Res., 58, 695–708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Maceyka M., Milstien S. and Spiegel S. (2013) The potential of histone deacetylase inhibitors in Niemann–Pick type C disease. FEBS J, 280, 6367–6372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Helquist P., Maxfield F.R., Wiech N.L. and Wiest O. (2013) Treatment of Niemann–Pick type C disease by histone deacetylase inhibitors. Neurotherapeutics, 10, 688–697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Pipalia N.H., Cosner C.C., Huang A., Chatterjee A., Bourbon P., Farley N., Helquist P., Wiest O. and Maxfield F.R. (2011) Histone deacetylase inhibitor treatment dramatically reduces cholesterol accumulation in Niemann–Pick type C1 mutant human fibroblasts. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A., 108, 5620–5625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Wang C., Bouchecareilh M. and Balch W.E. (2017) Measuring the effect of histone deacetylase inhibitors (HDACi) on the secretion and activity of alpha-1 antitrypsin. Methods Mol. Biol., 1639, 185–193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Bouchecareilh M., Hutt D.M., Szajner P., Flotte T.R. and Balch W.E. (2012) Histone deacetylase inhibitor (HDACi) suberoylanilide hydroxamic acid (SAHA)-mediated correction of alpha1-antitrypsin deficiency. J. Biol. Chem., 287, 38265–38278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Bouchecareilh M. and Balch W.E. (2012) Proteostasis, an emerging therapeutic paradigm for managing inflammatory airway stress disease. Curr. Mol. Med., 12, 815–826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Steffan J.S., Bodai L., Pallos J., Poelman M., McCampbell A., Apostol B.L., Kazantsev A., Schmidt E., Zhu Y.Z., Greenwald M. et al. (2001) Histone deacetylase inhibitors arrest polyglutamine-dependent neurodegeneration in Drosophila. Nature, 413, 739–743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. McCampbell A., Taye A.A., Whitty L., Penney E., Steffan J.S. and Fischbeck K.H. (2001) Histone deacetylase inhibitors reduce polyglutamine toxicity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A., 98, 15179–15184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Hockly E., Richon V.M., Woodman B., Smith D.L., Zhou X., Rosa E., Sathasivam K., Ghazi-Noori S., Mahal A., Lowden P.A. et al. (2003) Suberoylanilide hydroxamic acid, a histone deacetylase inhibitor, ameliorates motor deficits in a mouse model of Huntington’s disease. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A., 100, 2041–2046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Ferrante R.J., Kubilus J.K., Lee J., Ryu H., Beesen A., Zucker B., Smith K., Kowall N.W., Ratan R.R., Luthi-Carter R. et al. (2003) Histone deacetylase inhibition by sodium butyrate chemotherapy ameliorates the neurodegenerative phenotype in Huntington’s disease mice. J. Neurosci., 23, 9418–9427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Gardian G., Browne S.E., Choi D.K., Klivenyi P., Gregorio J., Kubilus J.K., Ryu H., Langley B., Ratan R.R., Ferrante R.J. et al. (2005) Neuroprotective effects of phenylbutyrate in the N171-82Q transgenic mouse model of Huntington’s disease. J. Biol. Chem., 280, 556–563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Igarashi S., Morita H., Bennett K.M., Tanaka Y., Engelender S., Peters M.F., Cooper J.K., Wood J.D., Sawa A. and Ross C.A. (2003) Inducible PC12 cell model of Huntington’s disease shows toxicity and decreased histone acetylation. Neuroreport, 14, 565–568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Sadri-Vakili G., Bouzou B., Benn C.L., Kim M.O., Chawla P., Overland R.P., Glajch K.E., Xia E., Qiu Z., Hersch S.M. et al. (2007) Histones associated with downregulated genes are hypo-acetylated in Huntington’s disease models. Hum. Mol. Genet., 16, 1293–1306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Sirinupong N. and Yang Z. (2015) Epigenetics in cystic fibrosis: epigenetic targeting of a genetic disease. Curr. Drug Targets, 16, 976–987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Parra M. (2015) Class IIa HDACs—new insights into their functions in physiology and pathology. FEBS J., 282, 1736–1744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Chun P. (2018) Therapeutic effects of histone deacetylase inhibitors on kidney disease. Arch. Pharm. Res., 41, 162–183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Han Y. and He X. (2016) Integrating epigenomics into the understanding of biomedical insight. Bioinform. Biol. Insights, 10, 267–289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Dubey H., Gulati K. and Ray A. (2018) Recent studies on cellular and molecular mechanisms in Alzheimer’s disease: focus on epigenetic factors and histone deacetylase. Rev. Neurosci., in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Moran-Salvador E. and Mann J. (2017) Epigenetics and liver fibrosis. Cell Mol. Gastroenterol. Hepatol., 4, 125–134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Zeybel M., Luli S., Sabater L., Hardy T., Oakley F., Leslie J., Page A., Moran Salvador E., Sharkey V., Tsukamoto H. et al. (2017) A proof-of-concept for epigenetic therapy of tissue fibrosis: inhibition of liver fibrosis progression by 3-Deazaneplanocin A. Mol. Ther., 25, 218–231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Pasyukova E.G. and Vaiserman A.M. (2017) HDAC inhibitors: a new promising drug class in anti-aging research. Mech. Ageing Dev., 166, 6–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Yang S.S., Zhang R., Wang G. and Zhang Y.F. (2017) The development prospection of HDAC inhibitors as a potential therapeutic direction in Alzheimer’s disease. Transl. Neurodegener, 6, 19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Khan S., Kumar S. and Jena G. (2016) Valproic acid reduces insulin-resistance, fat deposition and FOXO1-mediated gluconeogenesis in type-2 diabetic rat. Biochimie, 125, 42–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Didonna A. and Opal P. (2015) The promise and perils of HDAC inhibitors in neurodegeneration. Ann. Clin. Transl. Neurol., 2, 79–101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Halili M.A., Andrews M.R., Sweet M.J. and Fairlie D.P. (2009) Histone deacetylase inhibitors in inflammatory disease. Curr. Top. Med. Chem., 9, 309–319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Royce S.G. and Karagiannis T.C. (2014) Histone deacetylases and their inhibitors: new implications for asthma and chronic respiratory conditions. Curr. Opin. Allergy Clin. Immunol., 14, 44–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Wiseman R.L., Powers E.T., Buxbaum J.N., Kelly J.W. and Balch W.E. (2007) An adaptable standard for protein export from the endoplasmic reticulum. Cell, 131, 809–821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Subramanian K., Rauniyar N., Lavallee-Adam M., Yates J.R. 3rd and Balch W.E. (2017) Quantitative analysis of the proteome response to the histone deacetylase inhibitor (HDACi) vorinostat in Niemann–Pick Type C1 disease. Mol. Cell Proteomics, 16, 1938–1957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Pankow S., Bamberger C., Calzolari D., Martinez-Bartolome S., Lavallee-Adam M., Balch W.E. and Yates J.R. 3rd (2015) F508 CFTR interactome remodelling promotes rescue of cystic fibrosis. Nature, 528, 510–516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Hutt D.M., Olsen C.A., Vickers C.J., Herman D., Chalfant M., Montero A., Leman L.J., Burkle R., Maryanoff B.E., Balch W.E. et al. (2011) Potential agents for treating cystic fibrosis: cyclic tetrapeptides that restore trafficking and activity of DeltaF508-CFTR. ACS Med. Chem. Lett, 2, 703–707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Hutt D.M., Herman D., Rodrigues A.P., Noel S., Pilewski J.M., Matteson J., Hoch B., Kellner W., Kelly J.W., Schmidt A. et al. (2010) Reduced histone deacetylase 7 activity restores function to misfolded CFTR in cystic fibrosis. Nat. Chem. Biol., 6, 25–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Zwergel C., Stazi G., Valente S. and Mai A. (2016) Histone deacetylase inhibitors: updated studies in various epigenetic-related diseases. J. Clin. Epigenet., 2, 7–22. [Google Scholar]

- 76. Haberland M., Montgomery R.L. and Olson E.N. (2009) The many roles of histone deacetylases in development and physiology: implications for disease and therapy. Nat. Rev. Genet., 10, 32–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Garnock-Jones K.P. (2015) Panobinostat: first global approval. Drugs, 75, 695–704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. VanderMolen K.M., McCulloch W., Pearce C.J. and Oberlies N.H. (2011) Romidepsin (Istodax, NSC 630176, FR901228, FK228, depsipeptide): a natural product recently approved for cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. J. Antibiot., 64, 525–531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. West A.C. and Johnstone R.W. (2014) New and emerging HDAC inhibitors for cancer treatment. J. Clin. Invest., 124, 30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Bodas M., Mazur S., Min T. and Vij N. (2018) Inhibition of histone-deacetylase activity rescues inflammatory cystic fibrosis lung disease by modulating innate and adaptive immune responses. Respir. Res., 19, 2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Luciani A., Villella V.R., Esposito S., Brunetti-Pierri N., Medina D., Settembre C., Gavina M., Pulze L., Giardino I. and Pettoello-Mantovani M. (2010) Defective CFTR induces aggresome formation and lung inflammation in cystic fibrosis through ROS-mediated autophagy inhibition. Nat. Cell Biol., 12, 863–875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Bergougnoux A., Petit A., Knabe L., Bribes E., Chiron R., De Sario A., Claustres M., Molinari N., Vachier I. and Taulan-Cadars M. (2017) The HDAC inhibitor SAHA does not rescue CFTR membrane expression in Cystic Fibrosis. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol., 88, 124–132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Denning G.M., Anderson M.P., Amara J.F., Marshall J., Smith A.E. and Welsh M.J. (1992) Processing of mutant cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator is temperature-sensitive. Nature, 358, 761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Marks P.A., Richon V.M. and Rifkind R.A. (2000) Histone deacetylase inhibitors: inducers of differentiation or apoptosis of transformed cells. J. Natl. Cancer Inst., 92, 1210–1216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Crisanti M.C., Wallace A.F., Kapoor V., Vandermeers F., Dowling M.L., Pereira L.P., Coleman K., Campling B.G., Fridlender Z.G., Kao G.D. et al. (2009) The HDAC inhibitor panobinostat (LBH589) inhibits mesothelioma and lung cancer cells in vitro and in vivo with particular efficacy for small cell lung cancer. Mol. Cancer Ther., 8, 2221–2231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Murata M., Towatari M., Kosugi H., Tanimoto M., Ueda R., Saito H. and Naoe T. (2000) Apoptotic cytotoxic effects of a histone deacetylase inhibitor, FK228, on malignant lymphoid cells. Jpn. J. Cancer Res., 91, 1154–1160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Okabe S., Tauchi T., Nakajima A., Sashida G., Gotoh A., Broxmeyer H.E., Ohyashiki J.H. and Ohyashiki K. (2007) Depsipeptide (FK228) preferentially induces apoptosis in BCR/ABL-expressing cell lines and cells from patients with chronic myelogenous leukemia in blast crisis. Stem Cells Dev., 16, 503–514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]