Abstract

Subjective cognitive complaints increase with age. Although subjective cognitive difficulties have been linked to cognitive impairment and psychological distress, some studies have failed to establish a link between subjective cognitive complaints and present or future cognitive impairment. The present study examined the interactive, longitudinal effects of age, psychological distress, and objective cognitive performance on subjective cognitive function. Older adults (N=147, Mage = 74.17) were assessed biannually for up to six years. Subjective cognitive function, psychological distress, and neuropsychological testing were obtained at each assessment. In multilevel models with single predictors, age, poorer average task-switching and poorer memory predicted worse subjective cognitive functioning. Both average levels and within-person deviations in distress predicted worse subjective cognitive function. There were two significant interactions: one between average distress and chronological age, and the other between average memory and within-person distress. Task switching performance and distress had an additive effect on subjective cognitive function. Both individual differences (i.e., between-person differences) and fluctuations over time (i.e., within-person changes) contributed to worse subjective cognitive function. Psychological distress may help explain the relationship between objective cognitive performance and subjective cognitive function and should be assessed when patient concerns about cognitive functioning arise.

Keywords: subjective cognitive functioning, age, psychological distress, memory, task-switching efficiency

Medical professionals often rely on patients’ subjective health function to initiate the diagnostic process, and for good reason: overall self-reported health can predict health outcomes, including mortality, above and beyond other risk factors (e.g., Haring et al., 2011; Idler & Benyamini, 1997; Lyyra et al., 2006). In contrast, evidence supporting the predictive utility of subjective cognitive function is mixed. On the one hand, results from both cross-sectional and longitudinal studies suggest that subjective cognitive difficulties are associated with and can predict future cognitive impairment, dementia, and neurodegenerative diagnoses (Mitchell, 2008; Waldorff et al., 2012; for reviews see Jonker et al., 2000; Reid & Maclullich, 2006; Burmester et al., 2016). Meta-analytic evidence suggests that individuals with subjective memory difficulties but no initial objective impairment are twice as likely to develop dementia compared with individuals without such complaints (Mitchell et al., 2014).

Others report weak, marginal, or no relationship between subjective function and objectively measured age-related cognitive decline (Schmidt et al., 2001; Rabbitt & Abson, 1991; Best et al., 1992; Hanninen et al., 1994; Silva et al., 2014). Meta-analytic evidence suggests that while subjective cognitive difficulties predict future dementia, the vast majority of people with subjective cognitive difficulties do not develop significant pathology (Mendonca et al., 2016). Additionally, memory complaints may not reliably reflect actual deficits in memory performance (Schmidt et al., 2001), nor predict future dementia (Silva et al., 2014). In fact, actual memory change did not predict subjective memory change in a recent longitudinal study (Hertzog et al., 2018).

Subjective cognitive function declines with age (Jonker et al., 2000) and are likely influenced by multiple processes (Riedel-Heller et al., 2000). Aging is associated with normative cognitive declines that likely impact subjective function. Memory decline is one of the most common complaints associated with aging. Episodic memory (e.g., recalling word lists) naturally declines with time (Ronnlund et al., 2005). Executive functioning is a complex cognitive domain critical in mental flexibility, organizing, and problem solving (Lezak et al., 2012) and also declines with age. The ability to selectively attend to stimuli, switch tasks, and inhibit normal patterns of responding becomes more difficult in later life (Harada et al., 2013).

Psychological distress may help explain the mixed findings for the relation between objective cognitive performance and subjective cognitive function. In a recent review, depression emerged as one of the strongest factors associated with subjective memory complaints (Brigola et al., 2015). Depressive symptoms, such as negative self-efficacy and self-worth, may influence older adults’ perceptions of their memory (Tournier & Postal, 2011) and predict objective cognitive performance (Rabbitt & Abson, 1991). Despite evidence linking psychological distress and objective cognitive performance to subjective cognitive function, we are unaware of any studies that tested the interactive effects of distress and objective cognitive performance.

Two competing conceptual models linking psychological distress and physical functioning exist, but have never been applied to the relationship between distress and cognitive performance. The amplification model posits that distress leads to negative and internally focused attention, causing misrepresentation of subtle symptoms as serious threats (Costa & McCrae, 1987; Watson & Pennebaker, 1989). In other words, psychological distress magnifies the presence of physical symptoms (e.g., psychological distress may lead a patient to interpret foot pain as a broken bone rather than a muscle strain). Alternatively, the zero-sum model suggests that as symptoms become more severe, indicating clear problems, distress may affect subjective health less (Martin et al., 2003; Suls & Howren, 2012). In this model, the symptoms are so obvious that distress does not impact subjective interpretation (e.g., people with compound fracture see their fractured bone, clearly indicating the problem, and their emotional state does not influence this appraisal).

These competing hypotheses have been tested in the context of self-rated health in older adults (Segerstrom, 2014). Higher trait negative affect associated with worse self-rated health mainly among old-old people. However, changes in negative affect over time influenced self-rated health mainly among young-old people (Segerstrom, 2014). Therefore, between-person differences in affect supported the amplification model (trait negative affect amplifying age-related changes in health) whereas within-person changes in affect supported the zero-sum model (state negative affect overwhelmed by age-related changes in health). The different pattern of results highlights the need to utilize a multilevel, multivariable design that distinguishes between- and within-person effects of negative affect on self-rated health in older adults. This framework has not been applied to subjective cognitive function.

The purpose of this study is to apply these conceptual models to understand the relationships among subjective cognitive function, objective cognitive performance, and psychological distress in older adults. Both models imply interactions between objective cognitive function and psychological distress predicting subjective cognitive health. The amplification model suggests that the effect of poorer objective cognitive performance on subjective reports will be amplified by psychological distress, resulting in a negatively signed interaction term (i.e., as psychological distress increases, any negative relationship between poorer objective cognitive performance and subjective cognitive function becomes stronger). The zero-sum model suggests that objective cognitive performance will override psychological distress’s influence on subjective reports, resulting in a positively signed interaction term (i.e., as objective cognitive performance declines, any negative relationship between psychological distress and subjective cognitive function becomes weaker). The present study used multilevel modeling to examine how chronological age, objective cognitive functioning assessed via neuropsychological testing, and psychological distress relate to subjective cognitive functioning between and within people. Insofar as subjective cognitive function operates similarly to self-rated health, we expected to find between person changes in distress to support the amplification model, but within-person changes in distress to support the zero-sum model.

Methods

Participants

Participants were 147 healthy, older adults. All participants were English speakers, married, over the age of 60, and living in central Kentucky. Participants were excluded from the parent study, which included measurement of immunological aging, if they met any of the following criteria: smoked tobacco, had an autoimmune disease (e.g., rheumatoid arthritis, Crohn’s disease, Type I diabetes) or immunosuppressive disorder (e.g., HIV), had cancer within the past 5 years, had a chronic, severe infection (e.g., hepatitis), or had chemotherapy or radiation treatment in the past 5 years. They were also excluded if they were taking the following medications: opioids, systemic steroids, cytotoxic drugs, TNF blockers, medications for cognitive impairment, or if they were taking more than two of the following medications: alpha or beta blockers, ACE inhibitors, hormone replacement, thyroid supplements, or antidepressants/anxiolytics/hypnotics. These restrictions were meant to ensure a relatively healthy sample at study entry.

Procedures

Participants were recruited from a volunteer research subject pool maintained by the Sanders-Brown Center on Aging at the University of Kentucky. Approval for the study was obtained from the University of Kentucky Institutional Review Board (IRB). Informed consent was obtained from all study participants. Participants completed biannual visits with a research assistant over 6 years (i.e., up to 13 visits). During these visits, participants were administered a series of neurocognitive tasks that assessed objective cognitive function (i.e., verbal memory, executive function), as well as psychological questionnaires that assessed subjective cognitive function and psychological distress. All participants received a $20 gift card at each visit.

Measures

Demographics.

Demographic information was collected at the first interview. Date of birth and interview date were used to calculate exact chronological age at each visit. The sample was primarily Caucasian (96.5% white; 3.5% African American) and well-educated (M = 15.9 years of education; SD: 2.53; range = 7-22 years).

Objective Cognitive Performance.

Verbal memory and executive functioning decline with age (Harada, Natelson Love, & Triebel, 2013). Therefore, neuropsychological tests of these two domains were included in the battery to assess objective cognitive functioning.

Verbal memory.

Participants were administered the Rey Auditory Verbal Learning Test (RAVLT) at every other visit (i.e., once a year) to reduce practice effects. The RAVLT is a well-validated, list-learning measure of verbal memory and is one of the most commonly used memory assessment tools in applied settings (Rabin, Barr, & Burton, 2005). The RAVLT was selected for the present study as it is often considered a “purer” measure of verbal memory (Golden, Espe-Pfeifer, & Wachsler-Felder, 2000). Because the word list cannot be categorized in any meaningful way (as with other list-learning tasks), the examinee is unable to rely on executive compensatory strategies. The measure consists of a 15-item word list that is presented five times, always in the same order, with a subsequent test of recall following each trial. The measure also includes a test of short-delay recall, long-delay recall, and recognition. The RAVLT total score (Trials 1-5) and long-delayed recall scores have high test-retest reliability and are sensitive to brain dysfunction in a variety of neurological conditions (Strauss, Sherman, & Spreen, 2006). Thus, for the present study, the raw scores for long-delay recall and total recall (Trials 1-5) were equally weighted and combined to create the RAVLT total score. We reverse-coded RAVLT total scores by subtracting the total score from 30 (the highest possible score); higher scores indicate more memory impairment (i.e., poorer memory). Raw scores (instead of normed scores) were used because we were interested in the effects of age as a moderator on the associations between objective cognitive performance and subjective cognitive function (at study entry: M = 11.73; SD = 5.06; range = 2.4 – 22.8). In addition, in longitudinal studies, normed scores are artificially discontinuous when participants transition between age categories.

Task switching efficiency.

Participants were administered the Trail Making Test (TMT) at every visit, every 6 months to assess task switching efficiency. The TMT is one of the most well validated and widely utilized assessments of scanning and visuo-motor tracking, divided attention, and cognitive flexibility (Lezak, Howeison, Bigler, & Tranel, 2012). The TMT has two parts, Part A (at study entry: M = 45.21 seconds; SD = 21.79 seconds), which requires participants to connect the numbers 1-25 in ascending order on a page, and Part B (at study entry: M = 110.84 seconds; SD = 21.79 seconds), which requires participants to connect numbers and letters in alternating order (e.g., 1-A-2-B-3-C) on a page. TMT Part A assesses an individual’s motor speed, visuo-motor tracking, and attention abilities, whereas Part B incorporates components of executive functioning (divided attention and task switching). The TMT is extremely popular among clinicians and researchers due to its high sensitivity to the presence of cognitive impairment. The TMT effectively predicts instrumental activities of daily living (iADLs) among the elderly (Cahn-Weiner et al., 2002) and is used as a measure of executive function in older adults (Bell-McGinty et al., 2002). For the current study, the TMT was operationalized as seconds to complete B minus seconds to complete A, to isolate the executive control component required to complete Part B (e.g., Misdraji & Gass, 2010; Lezak, 1995; Corrigan & Hinkeldey, 1987). Thus, higher scores reflect poorer task switching efficiency (Drane et al., 2002). Part B – Part A scores were log10 transformed to correct positive skew.

Subjective Cognitive Function.

The six-item Medical Outcomes Study Cognitive Function Scale (MOS COG; Hays, Sherbourne, & Mazel, 1995) assessed day-to-day cognitive difficulties in various aspects of cognitive functioning including reasoning, attention, concentration, and memory. Higher scores reflect better self-reported cognitive functioning (fewer difficulties). At study entry, participants reported having cognitive difficulties, on average, “a little of the time” (1= all the time; 6 = none of the time; M = 5.15; SD = .62; range = 2.33 – 6).

Because the present study was concerned with both individual differences and change over time, the reliability of these two sets of items was calculated both between and within people (Cranford et al., 2006). The MOS COG showed excellent between-person reliability (.99; Cranford et al., 2006, Equation 4) and adequate within-person reliability (.78; Cranford et al., 2006, Equation 5).

Psychological Distress.

Participants were administered the Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS; Yesavage et al., 1983) and Perceived Stress Scale (PSS; Cohen et al., 1983) at each visit. Each measure taps into two domains of distress, including the affective domain (“Do you often feel downhearted and blue” from the GDS, and “How often have you been upset because of something that happened unexpectedly” from the PSS) and the cognitive domain (“Do you have trouble concentrating” from the GDS and “How often have you been able to control irritations in your life” from the PSS). We computed a composite measure of psychological distress yielding a total score per person, per wave (Segerstrom et al., 2012). Higher scores indicate higher psychological distress (at study entry: M = 6.9; SD = 5.46; range = .25 – 27.75). These scales showed excellent between-person reliability (.96-.99; Cranford et al., 2006, Equation 4) and adequate within-person reliability (.58-.73; Cranford et al., 2006, Equation 5). These reliability coefficients are consistent with other measures of affect (Cranford et al., 2006).

Data Analysis

Data were analyzed using multilevel models, with people at the higher level and waves at the lower level in SAS PROC MIXED with maximum likelihood estimation (Singer, 2002). Multilevel models were used to account for the repeated measurements within person, and to also account for missing data without the need for either list-wise deletion or data imputation (Singer & Willet, 2003). To separate influences of task-switching efficiency, memory, and distress on subjective cognitive function at Level 1 (within-person changes) and Level 2 (between-person differences), each variable was person-centered (Enders & Tofighi, 2007). Thus, the average score for each person across all of his or her visits captured Level 2 or between-person variance (i.e., “average”), and each visit’s deviation from that average score captured Level 1 or within-person variance (i.e., “deviations”). When entered together, these predictors are orthogonal and quantify the effect at each level (between-person differences and within-person changes).

Null models with no predictors were used to estimate the intraclass correlations and intercepts (i.e., sample means) for model variables. Subsequent models added age and average and deviations in task switching efficiency (TMT), memory (RAVLT), and distress as univariate predictors. All models controlled for gender, as well as the number of TMT and RAVLT administrations to account for practice effects. Age was centered on the youngest age in the study (60 years) to estimate the intercept at this age and slopes from this age onward. To address the moderation hypotheses, average and deviations in distress were tested as moderators of average and deviations in task switching and memory in predicting cognitive function. Significant interactions were probed using the 10th percentile for low levels of the continuous variables and the 90th percentile for the high levels of the variables, following methods outlined by Aiken and West (1991). Results are reported as gamma weights with their standard errors and associated t tests. Gamma weights are similar to unstandardized beta weights in regression. Variance of the intercept (i.e., between-person variable not accounted for by predictors) and residual (i.e., within-person variance not accounted for by predictors) are also reported for each model.

Sensitivity analyses were conducted to address potentially overlapping items between the MOS-COG and GDS items in the composite measure of psychological distress. Analyses were re-run with a modified psychological distress score that excluded four items from the GDS pertaining to subjective cognitive functioning (“Is your mind as clear as it used to be”; “Do you have trouble concentrating”; “Is it easy for you to make decisions”; “Do you feel that you have more problems with memory than most”). This modification resulted in minimal changes in reliability (excellent between-person reliability (.99; Cranford et al., 2006, Equation 4) and adequate within-person reliability (.79; Cranford et al., 2006, Equation 5). The pattern of findings remained unchanged, with the exception of one new significant interaction, discussed in the subsequent section.

Results

Means and Zero Order Relationships

Table 1 presents descriptive statistics, intraclass correlation coefficients (ICC), and bivariate correlations for all study variables. Of note, the majority of variability (ICC = 61%) in subjective cognitive functioning was stable across the study period and could be attributed to between-person differences in the sample. Between people, subjective cognitive functioning was significantly negatively correlated with memory, executive functioning, and distress.

Table 1:

Descriptive Statistics and Bivariate Correlations among Variables at Study Entry and Descriptive Statistics.

| Intercept | ICC | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables with between-and within-person variance | ||||||

| 1. Task switching difficulties | 2.11 | .703 | - | .45* | .09* | −.26* |

| 2. Poorer memory | 48.93 | .737 | .12 | - | −.07* | −.08* |

| 3. Distress | 7.27 | .760 | .08 | .07 | - | −.65* |

| 4. Subjective Cognitive Functioning | 5.05 | .605 | −.05 | .00 | −.37 | - |

| M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |

| Variables with between-person variance only | ||||||

| Age At Study Entry | 74.17 | 5.63 | .25* | .34* | .00 | −.09* |

| Female Sex (1=female) | 58.2% | - | −.13* | −.48* | .19* | −.09* |

Note: Task switching and memory are coded such that higher scores indicate more impairment. Between-person correlations are shown above the diagonal, and within-person correlations are shown below the diagonal. ICC = intraclass correlation coefficient. No statistical significance indication for within-person correlation is provided, because doing so may be biased when the data are not independent observations. Correlations are shown only for the purposes of illustrating effect sizes.

p < .05.

Univariate Models

Univariate models were conducted to examine the main effects of age, task switching, memory, and distress on subjective cognitive functioning (see Table 2). Older age at baseline and aging (i.e., passage of time, in years) were both associated with poorer subjective cognitive functioning (γ = −.016, SE=.007, t(147) = −2.31, p = .022 for age; γ = −.019, SE=0.004, t(1092) = −5.05, p <.0001 for aging). The magnitudes of the associations were similar, suggesting no selection bias at baseline. Additionally, there was a significant random effect of aging, suggesting that aging affected some people’s subjective cognitive functioning more than others.

Table 2.

Univariate Models Predicting Subjective Cognitive Functioning.

| Predictor | Model Parameter | Estimate (SE) | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Null Model (no predictor) | Random Effects | ||

| Intercept | 0.27 (0.04) | - | |

| Residuals | 0.15 (0.007) | - | |

| Age | Fixed Effects | ||

| Intercept | 5.30(0.11) | <.0001 | |

| Sex (vs. female) | 0.16 (0.09) | .07 | |

| Deviations in Age | −0.02 (0.004) | <.0001 | |

| Average Age | −0.02 (0.007) | .0225 | |

| Random Effects | |||

| Intercept | 0.26 (0.04) | - | |

| Slope for Average Age | 0.0004 (0.0002) | - | |

| Residuals | 0.15 (0.007) | - | |

| Intercept/Slope Covariance | −0.003 (0.002) | - | |

| Task Switching | Fixed Effects | ||

| Intercept | 5.09 (0.06) | <.0001 | |

| Sex (vs. female) | 0.14 (0.08) | .10 | |

| Administrations | −0.02 (.003) | <.0001 | |

| Deviations in EF | −0.10 (0.08) | .19 | |

| Average EF | −1.15 (0.28) | <.0001 | |

| Random Effects | |||

| Intercept | 0.23 (0.03) | - | |

| Residuals | 0.15 (0.007) | - | |

| Intercept/Slope Covariance | −0.002 (0.002) | - | |

| Memory | Fixed Effects | ||

| Intercept | 5.00 (0.06) | <.0001 | |

| Sex (vs. female) | 0.26 (0.10) | .01 | |

| Administrations | −0.04 (.01) | <.0001 | |

| Deviations in Memory | 0.001 (0.007) | .81 | |

| Average Memory | −0.03 (0.009) | .01 | |

| Random Effects | |||

| Intercept | 0.24 (0.04) | - | |

| Residuals | 0.15 (0.01) | - | |

| Intercept/Slope Covariance | −0.002 (0.003) | - | |

| Distress | Fixed Effects | ||

| Intercept | 5.52 (0.07) | <.0001 | |

| Sex (vs. female) | −0.02 (0.07) | .80 | |

| Deviations in Distress | −0.06 (0.004) | <.0001 | |

| Average Distress | −0.07 (0.007) | <.0001 | |

| Random Effects | |||

| Intercept | 0.18 (0.03) | - | |

| Slope for Deviations in Distress | 0.0004 (0.0002) | - | |

| Residuals | 0.130 (0.006) | - | |

| Intercept/Slope Covariance | −0.005 (0.002) | - | |

NOTE: Models of task switching and memory are based on a different sample size due to missing data, and as such, variance components of those models cannot be directly compared to the variance components of the other models.

Poorer average task switching efficiency and memory performance were each associated with poorer subjective cognitive functioning (γ = −1.092, SE=.282, t(145) = −3.86, p<.0001 for task switching; γ = −.025, SE=.009, t(147) = −2.63, p=.010 for memory). However, deviations in task switching and in memory were not associated with changes in subjective cognitive functioning. In addition, there were no significant random effects of deviations in task switching or memory (p > .05).

Finally, there were significant effects of average levels of and within-person deviations in distress predicting worse subjective cognitive functioning (γ = −.068, SE=.007, t(147) = −9.10, p<.0001 for average; γ = −.057, SE=.004, t(1092) =−12.85, p<.0001 for deviations). These results suggest that higher distress on average, and at visits when people reported higher distress than their own average, were both associated with poorer subjective cognitive functioning. There was also a significant random effect of within-person deviations, suggesting that deviations in distress had stronger effects on subjective cognitive functioning for some people than others.

Distress as a Moderator

With regard to age, an interaction between average distress and aging (i.e., within-person effect of time) on subjective cognitive function did not reach statistical significance in the primary analysis (γ = −.0016, SE=.0009, p = .0617) but was statistically significant in the sensitivity analysis excluding cognitive items from the GDS (γ = −.0023, p = .03; see Figure 1). People with higher average distress showed accelerated decline over time in their subjective cognitive function (simple slope: γ = −.024, SE = .005, t = −4.58, p<.0001), as compared to those with lower average distress (simple slope: γ = −.009, SE = .005, t=−2.05, p=.040). There were no other significant interactions between average levels of or deviations in distress and age on subjective cognitive function (all ps>.05). With regard to task switching and memory, neither average levels of nor deviations in distress moderated the effect of executive function or memory on subjective cognitive function (all ps>.05).

Figure 1.

Simple slopes decomposition of the interaction between average distress and effect of aging (i.e., time, in years) on subjective cognitive function, from sensitivity analysis. Low distress is centered around 2.48 (10th percentile) and high distress is centered around 11.54 (90th percentile).

Sensitivity Analysis

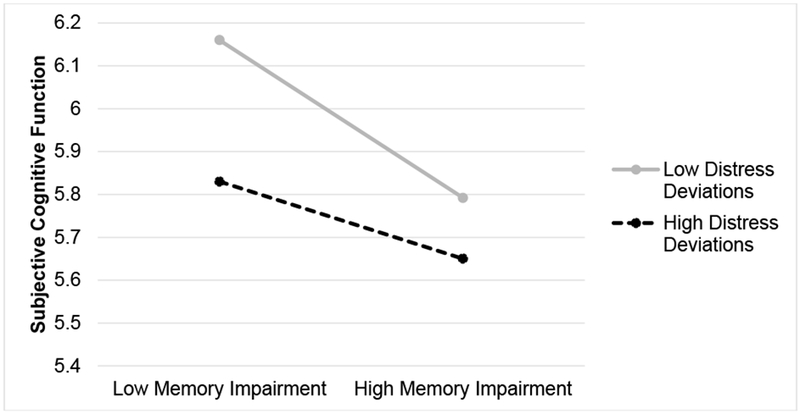

There was a significant interaction between average memory and deviations in distress on subjective cognitive function (γ = .003, SE=.001, t(483)=2.20, p=.028; see Figure 2). People with low average memory impairment had higher subjective cognitive function (fewer difficulties) at times when they had low within-person distress (γ = −.026, SE=.009, t(144)=−2.92, p=.004). In contrast, regardless of average level of memory impairment (low or high), people had lower subjective cognitive function (more cognitive difficulties) at times when they had high within-person distress (simple slope: γ = −.013, SE=.009, t(144)=−1.46, p=.15).

Figure 2.

Simple slopes decomposition of the interaction between within-person deviations in distress and memory impairment on subjective cognitive function, from sensitivity analysis.

Discussion

The present study examined the longitudinal effects of aging, psychological distress, and objective cognitive performance (via neuropsychological testing) on self-reported cognitive function, using two conceptual models (amplification and zero-sum models). The amplification model suggests that objective problems will be amplified by subjective experiences (Diehl & Wahl, 2010; Watson & Pennebaker, 1989), whereas the zero-sum model posits that objective problems will override subjective experiences (Suls & Howren, 2012). These models were tested to shed some light on inconsistent findings in the literature. Some studies have linked subjective cognitive difficulties to cognitive impairment and future cognitive decline (Jonker et al., 2000; Reid & Maclullich, 2006, Waldorff et al., 2012) but others have found the relationship to be weak (Best et al., 1992; Hanninen et al., 1994; Rabbitt & Abson, 1991; Schmidt et al., 2001). The present study examined between-person individual differences and within-person change over time to help elucidate these relationships.

Aging was associated with declines in subjective cognitive function, and these declines with age tended to be stronger for older adults who experienced higher average levels of distress (Figure 1). In other words, aging effects on subjective cognitive function were amplified by higher levels of distress. This finding supports the amplification hypothesis and replicates previously reported findings in the context of self-rated physical health: as age increased, individual differences in negative affect had a greater influence on self-rated health (Segerstrom, 2014).

When cognitive items were excluded from the distress measure, there was further support for the amplification model. Subjective cognitive function and memory impairment were more congruent when older adults reported lower-than-average distress compared with their own average. When they had higher-than-average distress, they rated subjective cognitive functioning lower (i.e., they reported more frequent cognitive lapses) irrespective of memory impairment. These findings offer additional support that distress may amplify or distort subjective cognitive function.

Taken together, we found some support for the amplification model and no support for the zero-sum model. It should be noted that cognitive impairment was not present due to the healthy nature of the sample. One possibility is that evidence of the zero-sum model would emerge in the presence of a larger range of cognitive problems.

Individual differences (i.e., between-person differences) and fluctuations over time (i.e., within-person changes) in distress and task switching efficiency influenced subjective cognitive function. Older adults reported worse subjective cognitive function both when they had higher trait distress than others and at times when they experienced higher-than-average distress. The impact of between-person differences and within-person changes in distress on subjective cognitive function may help explain the strong relationship between depression and subjective cognitive difficulties (Fischer et al., 2010; Balash et al., 2013; Buckley et al., 2013; Hurt et al., 2011). Poorer performance on neuropsychological tests was associated with worse subjective cognitive function—but only at the between-person level. This relationship was not found within-person, that is, cognitive function did not decline when individuals performed worse than their average on neuropsychological tests. The impact of between-person differences but not within-person changes in neuropsychological performance may help explain the smaller relationship between objective and subjective measures of cognitive functioning than between self-rated health and mortality risk (DeSalvo et al., 2006).

From a practical standpoint, subjective cognitive difficulties are common among older adults and have a detrimental impact on quality of life (Mol et al., 2007). The results of this study highlight the need for health professionals to assess neuropsychological performance and psychological distress when patients report declines in subjective cognitive function—with the awareness that psychological distress may exacerbate cognitive difficulties associated with age-related cognitive declines. In order to monitor changes in distress, health professionals may benefit from taking repeated measures of emotional well-being. In this way, clinicians can be privy to fluctuations in emotional health that may be contributing to change in subjective cognitive function over time.

The present study contained a fairly homogenous, well-educated, and healthy sample of older adults. Future studies should address these relationships in more diverse samples. Similarly, the current study used single measures to evaluate memory and task switching efficiency; future research should attempt to replicate these findings with a more comprehensive test battery including other well-validated measures of these cognitive domains as well as cognitive screeners (Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) or Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE)). The composite measure of psychological distress was used to capture both affective and cognitive forms of distress. Additional measures of psychological distress may be used in future studies (e.g., Kessler Psychological Distress Scale; Kessler & Mroczek, 1994).

The present study applied two conceptual models (amplification and zero-sum) to examine the longitudinal effects of aging, psychological distress, and objective cognitive performance (via neuropsychological testing) on self-reported cognitive function. Support was found for the amplification, but not zero-sum, model. For example, subjective cognitive function declines with age were stronger for older adults experiencing higher distress. The study also emphasized the importance of studying between- and within- person changes in distress and cognitive abilities. Distress, but not objective cognitive performance, significantly predicted subjective cognitive function at the between and within-person levels of analysis—further demonstrating the important relationship between psychological distress and subjective cognitive function.

To fully understand patient reports of cognitive problems, clinicians should collect both objective measures of cognitive function and inventories of emotional well-being. This information will assist in diagnosing and selecting appropriate interventions. Some individuals may require memory training (e.g., Mol et al., 2007; Jean et al., 2010; Mowszowski et al., 2010), psychological interventions, medication, or a combination.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by grants from the National Institute of Aging (F31-AG048697 to PJG; K99-AG056635 to RGR; R01-AG026307 and K02-AG033629 to SCS) and National Institute of Mental Health (T32-MH093315 to PJG).

References

- Aiken LS, & West SG (1991). Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Balash Y, Mordechovich M, Shabtai H, Giladi N, Gurevich T, & Korczyn AD (2013). Subjective memory complaints in elders: depression, anxiety, or cognitive decline? Acta Neurologica Scandinavica, 127, 344–350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell‐McGinty S, Podell K, Franzen M, Baird AD, & Williams MJ (2002). Standard measures of executive function in predicting instrumental activities of daily living in older adults. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 17(9), 828–834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Best DL, Hamlett KW, & Davis SW (1992). Memory complaint and memory performance in the elderly: the effects of memory skills training and expectancy change. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 6, 405–416. [Google Scholar]

- Brigola AG, Manzini CSS, Oliveira GBS, Ottaviani AC, Sako MP, & Vale FAC (2015). Subjective memory complaints associated with depression and cognitive impairment in the elderly: A systematic review. Dementia and Neuropsychologia, 9(1), 51–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckley R, Saling MM, Ames D, Rowe CC, Lautenschlager NT Macaulay SL, et al. (2013). Factors affective subjective memory complaints in the AIBL aging study: biomarkers, memory, affect and age. International Psychogeriatrics, 25, 1307–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burmester B, Leathem J, & Merrick P (2016). Subjective cognitive complaints and objective cognitive function in aging: a systematic review and meta-analysis of recent cross-sectional findings. Neuropsychology Review, 26, 376–393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S, Kamarck T, & Mermelstein R (1983). A global measure of perceived stress. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 24, 385–396. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corrigan JD & Hinkeldey NS (1987). Relationship between parts A and B of the Trail Making Test. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 43, 106–109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa PT Jr., & McCrae RR (1987). Neuroticism, somatic complaints, and disease: Is the bark worse than the bite? Journal of Personality, 55, 299–316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cranford JA, Shrout PE, Iida M, Rafaeli E, Yip T, & Bolger N (2006). A procedure for evaluating sensitivity to within-person change: Can mood measures in diary studies detect change reliably? Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 32, 917–929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeSalvo KB, Bloser N, Reynolds K, He J, & Muntner P (2006). Mortality prediction with a single general self-rated health question. A meta-analysis. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 21, 267–275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diehl MK, & Wahl HW (2010). Awareness of age-related change: Examination of a (mostly) unexplored concept. The Journals of Gerontology. Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 65, 340–350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drane DL, Yuspeh RL, Huthwaite JS, & Klingler LK (2002). Demographic characteristics and normative observations for derived-trail making test indices. Cognitive and Behavioral Neurology, 15(1), 39–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer CE, Jiang D, Schweizer TA (2010). Determining the association of medical co-morbidity with subjective and objective cognitive performance in an inner city memory disorders clinic: a retrospective chart review. BMC Geriatrics, 10, 1–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golden CJ, Espe-Pfeifer P, & Wachsler-Felder J (2000). Neuropsychological interpretation of objective psychological tests. Springer Science & Business Media. [Google Scholar]

- Hanninen T, Reinikainen KJ, Helkala EL, Koivisto K, Mykkanen L, Laakso M, Pyorala K, & Riekkinen PJ (1994). Subjective memory complaints and personality traits in normal elderly subjects. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 42, 1–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harada CN, Love MCN, & Triebel KL (2013). Normal cognitive aging. Clinics in geriatric medicine, 29(4), 737–752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haring R, Feng Y, Moock J, Volzke H, Dorr M, Nauck M, Wallaschofski H, & Kohlmann T (2011). BMC Medical Research Methodology, 11, 103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hertzog C, Hulur G, Gerstorf D, & Pearman AM (2018). Is subjective memory change in old age based on accurate monitoring of age-related memory change? Evidence from two longitudinal studies. Psychology and Aging, 33, 273–287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurt CS, Burns A, & Barrowclough C (2011). Perceptions of memory problems are more important in predicting distress in older adults with subjective memory complaints than coping strategies. International Psychogeriatrics, 23(8), 1334–1343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Idler EL, & Benyamini Y (1997). Self-rated health and mortality: A review of twenty-seven community studies. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 38, 21–37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jean L, Bergeron ME, Thivierge S, & Simard M (2010). Cognitive intervention programs for individuals with mild cognitive impairment: Systematic review of the literature. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 18, 281–296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jonker C, Geerlings MI, Schmand B (2000). Are memory complaints predictive for demential? A review of clinical and population-based studies. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 15(11), 983–991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler R, & Mroczek D (1994). Final versions of our non-specific psychological distress scale. Memo dated March, 10, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Lezak M, Howieson D, & Loring D (2012). Neuropsychological assessment. 5th edition Oxford University Press; Oxford, New York. [Google Scholar]

- Lezak MD (1995). Neuropsychological Assessment, 3rd edition New York: Oxford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lyyra TM, Heikkinen E, Lyyra AL, & Jylha M (2006). Self-rated health and mortality: Could clinical and performance-based measures of health and functioning explain the association? Archives of Gerontology and Geriatrics, 42, 277–288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin R, Rothrock N, Leventhal. H, & Leventhal e. (2003). Common-sense models of illness: Implictions for symptom perception and health-related behaviors In Suls J & Wallston KA (Eds.), Social psychological foundations of health and illness (pp. 199–225). Malden, MA: Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell AJ (2008). The clinical significant of subjective memory complaints in the diagnosis of mild cognitive impairment and dementia: a meta-analysis. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 11, 1191–1202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell AJ, Beaumont H, Ferguson D, Yadegarfar M, & Stubbs B (2014). Risk of dementia and mild cognitive impairment in older people with subjective memory complaints: meta-analysis. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 130, 439–451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mol M, Carpay M, Ramakers I, Rozendaal N, Verhey F, & Jolles J (2007). The effect of perceived forgetfulness on quality of life in older adults; a qualitative review. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 5, 393–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mowszowski L, Batchelor J, & Naismith SL (2010). Early intervention for cognitive decline: can cognitive training be used as a selective prevention technique? International Psychogeriatrics, 22, 537–548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rabbitt P, & Abson V (1991). Do older people know how good they are? British Journal of Psychology, 82, 137–151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reid LM & Maclullich AM (2006). Subjective memory complaints and cognitive impairment in older people. Dementia and Geriatric Cognitive Disorder, 22, 471–485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rönnlund M, Nyberg L, Bäckman L, & Nilsson LG (2005). Stability, growth, and decline in adult life span development of declarative memory: cross-sectional and longitudinal data from a population-based study. Psychology and aging, 20(1), 3–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt IW, Berg I,J, & Deelman BG (2001). Relations between subjective evaluations of memory and objective memory performance. Perceptual and Motor Skills, 93, 761–776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segerstrom SC, Hardy JK, Evans DR, & Greenberg RN (2012). Vulnerability, distress, and immune response to vaccination in older adults. Brain, behavior, and immunity, 26(5), 747–753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segerstrom SC (2014). Affect and self-rated health: A dynamic approach with older adults. Health Psychology, 33(7), 720–728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silva D, Guerreiro M, Faria C, Jaroco J, Schmand BA, de Mendonca A (2014). Significance of subjective memory complaints in the clinical setting. Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry and Neurology, 27(4), 259–265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singer JD (2002). Fitting individual growth models using SAS PROC MIXED In Moskowitz DS & Hershberger SL (Eds.), Modeling intraindividual variability with repeated measures data: Methods and applications (pp.135–170). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum. [Google Scholar]

- Singer JD, & Willett JB (2003). Applied longitudinal data analysis: Modeling change and event occurrence. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Strauss E, Sherman EMS, & Spreen O (2006). A Compendium of Neuropsychological Tests: Administration, Norms, and Commentary. Oxford University Press: Oxford. [Google Scholar]

- Suls J, & Howren MB (2012). Understanding the physical-symptom experience: The distinctive contributions of anxiety and depression. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 21, 129–134. [Google Scholar]

- Tournier I & Postal V (2011). Effects of depressive symptoms and routinization on metamemory during adulthood. Archives of Gerontology and Geriatrics, 52, 46–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waldorff FB, Siersma V, Vogel A, & Wademar G (2012). Subjective memory complaints in general practice predicts future dementia: a 4-year follow-up study. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 27, 1180–1188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson D, & Pennebaker JW (1989). Health complaints, stress, and distress: Exploring the central role of negative affectivity. Psychological Review, 96, 234–254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yesavage JA, Brink TL, Rose TL, Lum O, Huang V, Adey M, Leirer VO (1983). Development and validation of a geriatric depression screening scale: A preliminary report. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 17, 37–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]