Background:

Atopic eczema (also known as atopic dermatitis, or simply eczema) was traditionally considered to remit in most children by adolescence. However, increasing genetic and epidemiologic evidence suggests that it is an episodic, inflammatory disorder that can occur throughout life (1). Atopic eczema affects between 10% and 25% of children in industrialized countries, but relatively little is known about physician-diagnosed adult disease (2).

Objective:

To estimate the age-specific prevalence of active atopic eczema across the lifespan in a large primary care population.

Methods and Findings:

We analyzed data between 1994 and 2013 from The Health Improvement Network. This U.K. cohort is known to be accurate; complete; and representative of the population in the United Kingdom, where primary care physicians manage 97% of cases of atopic eczema (3).

We identified patients with atopic eczema on the basis of a previously validated algorithm shown to have good positive predictive value for both children and adults in this cohort (90% and 82%, respectively) (4). Because atopic eczema is an episodic disorder that may remit for years, we then calculated the prevalence of active disease requiring a physician visit or prescription during each year of follow-up. We also examined the number and types of prescriptions given to patients and rates of asthma and rhinitis/seasonal allergies by age.

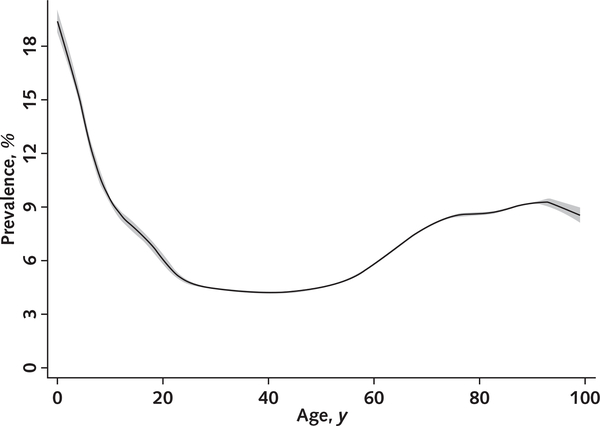

Among 8 604 333 persons aged 0 to 99 years, the cumulative lifetime prevalence of atopic eczema was 9.9% and rates of active disease were highest among children and older adults (Table and Figure). Patients received a median of 6 prescriptions for atopic eczema per year (interquartile range, 2 to 13 prescriptions), including topical steroids and systemic treatments, and the number of annual prescriptions was similar across ages. Rates of comorbid atopic disease were highest among adults aged 18 to 74 years.

Table.

Characteristics of Patients With AE, by Age Group

| Variable | Age Group |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0–17 Years (n = 751 655)* | 18–74 Years (n = 809 293)* | 75–99 Years (n = 175 909)* | Total (n = 640 572)* | |

| Mean prevalence ofactive AE during a given year, % | 12.3 | 5.1 | 8.7 | 6.9 |

| Sensitivity analysis 1: Active disease defined only by prescriptions | 8.8 | 3.8 | 7.9 | 5.2 |

| Sensitivity analysis 2: Excluding persons with any record of potentially overlapping diagnoses | 11.3 | 3.8 | 7.1 | 5.7 |

| Median prescriptions during a given year (IQR), n | ||||

| AnyAE-related therapy† | 6(3–14) | 5 (2–12) | 7 (3–14) | 6 (2–13) |

| Topical steroids or calcineurin inhibitors | 2 (1–4) | 2(1–5) | 2(1–6) | 2(1–5) |

| Patients with AE with ≥1 AE-related systemic treatment code during a given year, % | 0.1 | 1.7 | 1.5 | 1.1 |

| Patients with comorbid atopic disease during the study, % | ||||

| ≥1 diagnosis code for asthma | 9.8 | 14.2 | 5.3 | 13.4 |

| ≥1 diagnosis code for allergies/rhinitis | 13.8 | 25.1 | 7.8 | 21.7 |

AE = atopic eczema; IQR = interquartile range.

Numbers indicate the mean denominator for annual prevalence estimates across the age group.

lncludes topical skin preparations, topical steroids, topical calcineurin inhibitors, topical anti-infective treatments, and AE-related systemic treatments (including methotrexate, azathioprine, mycophenolate, cyclosporine, biologic agents, or phototherapy).

Figure. Annual prevalence of active AE, by age.

Local polynomial smoothed plot with shading indicating the 95% CIs generated from cross-sectional calculations of the prevalence of active AE at each age using Stata 15 (StataCorp). Active disease was defined by a visit or prescription code during each year of follow-up among patients who previously met the definition of AE (characterized by ≥1 of the following diagnosis codes: M111.00 [atopic dermatitis/eczema], M1120.0 [infantile eczema], M113.00 [flexural eczema], M114.00 [allergic/intrinsic eczema], and M12z100 [eczema not otherwise specified]) and were assigned ≥2 treatment codes for any AE-related therapy on separate dates (4). AE = atopic eczema.

We performed sensitivity analyses to assess for ascertainment and misclassification bias. Because adults may not visit providers as frequently as children and older persons, we tested the effect of basing the definition of active disease only on prescriptions rather than on prescriptions and medical codes from clinic visits. We also examined the effect of excluding persons diagnosed with conditions that may either overlap with or be misdiagnosed as atopic eczema (for example, contact dermatitis, psoriasis, scabies, ichthyosis, erythroderma, photodermatitis, and seborrheic dermatitis) (4) and found results similar to those from our primary analysis (Table).

Discussion:

We have shown that rates of active atopic eczema (as defined by diagnosis and treatment codes applied by physicians) increase with age among adults in primary care, addressing a gap in evidence about the epidemiology of this condition after childhood. The cohort is representative of the U.K. population; however, the true population prevalence of disease activity may be higher than our estimates, because medical records do not capture over-the-counter treatments and providers may not record mild disease. For example, a population-based study of U.S. adults aged 18 to 65 years found a higher 1-year prevalence of self-reported dermatitis overall (10.2%), with the highest rates among persons aged 62 to 85 years (11.4%) (5).

The presentation and terminology surrounding eczema are heterogeneous, and additional research is needed to understand whether disease pathogenesis is the same across ages. We cannot exclude misclassification bias, which may be higher among adults; however, sensitivity analyses show a similar U-shaped prevalence curve after persons with possible overlapping diagnoses were excluded.

Atopic eczema is known to substantially affect emotional and physical aspects of health-related quality of life but is often undertreated. This circumstance may change as more therapies become available: The U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved 2 new medications for this condition in 2016 and 2017, and more than a dozen additional agents are under development and clinical testing. As new targeted therapies become available, primary care providers will probably play a larger role in managing adults with atopic eczema. Attention should be paid to clinical testing in older adults, who may require special considerations for pharmacology, polypharmacy, and multimorbidity.

Acknowledgments

Financial Support: By grants from the Dermatology Foundation and the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (Dr. Abuabara); grants KL2TR001870 (Drs. Abuabara and McCulloch) and K76AG054631, R21CA212201, and DP2CA225433 (Dr. Linos) from the National Institutes of Health; and a Wellcome Senior Clinical Fellowship in Science (205039/Z/16/Z; Dr. Langan).

Footnotes

Disclosures: Disclosures can be viewed at www.acponline.org/authors/icmje/ConflictOfInterestForms.do?msNum=M18-2246.

Reproducible Research Statement: Study protocol: Not available. Statistical code: Available from Dr. Abuabara (katrina.abuabara@ucsf.edu). Data set: Available for purchase at www.iqvia.com/locations/uk-and-ireland/thin.

Contributor Information

Katrina Abuabara, University of California, San Francisco San Francisco, California.

Alexa Magyari, University of California, San Francisco San Francisco, California.

Charles E. McCulloch, University of California, San Francisco San Francisco, California.

Eleni Linos, University of California, San Francisco San Francisco, California.

David J. Margolis, Perelman School of Medicine, University of Pennsylvania Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

Sinéad M. Langan, London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine London, United Kingdom.

References

- 1.Brunner PM, Silverberg JI, Guttman-Yassky E, Paller AS, Kabashima K, Amagai M, et al. ; Councilors of the International Eczema Council. Increasing comorbidities suggest that atopic dermatitis is a systemic disorder. J Invest Dermatol. 2017;137:18–25. doi: 10.1016/j.jid.2016.08.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Odhiambo JA, Williams HC, Clayton TO, Robertson CF, Asher MI; ISAAC Phase Three Study Group. Global variations in prevalence of eczema symptoms in children from ISAAC Phase Three. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2009;124: 1251–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2009.10.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blak BT, Thompson M, Dattani H, Bourke A. Generalisability of The Health Improvement Network (THIN) database: demographics, chronic disease prevalence and mortality rates. Inform Prim Care. 2011;19:251–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Abuabara K, Magyari AM, Hoffstad O, Jabbar-Lopez ZK, Smeeth L, Williams HC, et al. Development and validation of an algorithm to accurately identify atopic eczema patients in primary care electronic health records from the UK. J Invest Dermatol. 2017;137:1655–62. doi: 10.1016/j.jid.2017.03.029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Silverberg JI, Hanifin JM. Adult eczema prevalence and associations with asthma and other health and demographic factors: a US population-based study. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2013;132:1132–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2013.08.031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]