Abstract

Dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO) is widely used as a solvent and cryopreservative in laboratories and considered to have many beneficial health effects in humans. Oxylipins are a class of biologically active metabolites of polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs) that have been linked to a number of diseases. In this study, we investigated the effect of DMSO on oxylipin levels in mouse liver. Liver tissue from male mice (C57Bl6/N) that were either untreated or injected with 1% DMSO at 18 weeks of age was analyzed for oxylipin levels using ultrahigh performance liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry (UPLC-MS/MS). A decrease in oxylipin diols from linoleic acid (LA, C18:2n6), alpha-linolenic acid (ALA, C18:3n3) and docosahexeanoic acid (DHA, C22:6n3) was observed 2 h after injection with DMSO. In contrast, DMSO had no effect on the epoxide precursors or other oxylipins including those derived from arachidonic acid (C20:4n6) or eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA, C20:5n3). It also did not significantly affect the diol:epoxide ratio, suggesting a pathway distinct from, and potentially complementary to, soluble epoxide hydrolase inhibitors (sEHI). Since oxylipins have been associated with a wide array of pathological conditions, from arthritis pain to obesity, our results suggest one potential mechanism underlying the apparent beneficial health effects of DMSO. They also indicate that caution should be used in the interpretation of results using DMSO as a vehicle in animal experiments.

Keywords: DMSO, antioxidant, inflammation, pain, arthritis, obesity, oxylipins, diols

Introduction

Dimethyl sulfoxide [DMSO, (CH3)2SO] is a polar aprotic compound with a high affinity for water (Brayton, 1986). It is commonly used as a solvent in biological experiments because it has low toxicity, can solubilize both polar and non-polar substances and can readily penetrate hydrophobic barriers such as the plasma membrane. These properties make it an ideal vehicle for both in vivo and in vitro experiments, especially for pharmacologic compounds that act on an intracellular level (Brayton, 1986).

Dimethyl sulfoxide has been reported to have therapeutic effects on a number of ailments including bacterial infections (Guo et al., 2016), dermatologic conditions (Lishner et al., 1985), chronic prostatitis (Shirley et al., 1978), gastrointestinal disorders (Salim, 1991, 1992a,b), pulmonary fibrosis and amyloidosis (Pepin and Langner, 1985; Iwasaki et al., 1994) arthritis (Elisia et al., 2016) and pain (Kingery, 1997; Kelava et al., 2011; Kumar et al., 2011; Rawls et al., 2017). Hepatoprotective effects of DMSO under various conditions of liver injury or hepatotoxicity have also been well documented (Siegers, 1978; Park et al., 1988; Achudume, 1991; Lind et al., 2000; Sahin et al., 2004). Although the physiological and pharmacological mechanisms underlying the beneficial health effects of DMSO are not fully known, they have been proposed to include its ability to increase blood flow to organs, decrease recruitment and activation of inflammatory cells and act as an antioxidant and free radical scavenger (Brayton, 1986; Beilke et al., 1987; Massion et al., 1996).

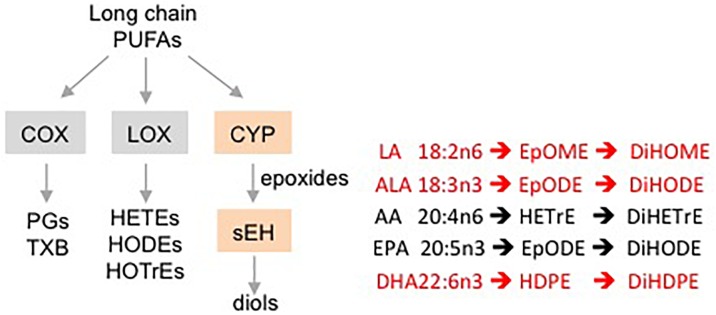

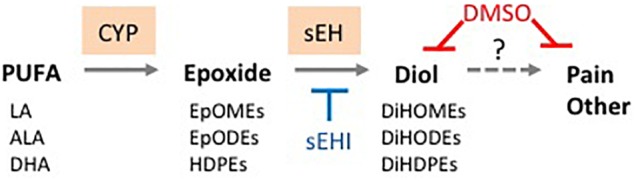

Oxylipins are biologically active, oxidized metabolites of long chain polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs) that are generated by three different pathways – COX, LOX and CYP/sEH (Yang et al., 2009) (Figure 1). The third pathway consists of a two-step reaction involving the action of cytochrome P450s (CYPs) and soluble epoxide hydrolase (sEH) enzymes. This pathway first produces oxylipin epoxides and then diols from linoleic acid (LA, C18:2 n-6), alpha-linolenic acid (ALA, C18:3 n-3), arachidonic acid (AA, C20:4 n-6), eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA, C20:5 n-3) and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA, C22:6 n-3) (Moghaddam et al., 1997; Zeldin, 2001; Levick et al., 2007). Increased accumulation of oxylipin diols has been correlated with the pathogenesis of a number of pathological conditions including obesity, diabetes, depression, pain and cardiovascular disease (Gouveia-Figueira et al., 2015; Caligiuri et al., 2017; Deol et al., 2017; Hennebelle et al., 2017). Compounds that inhibit the formation of these lipid mediators, such as inhibitors of sEH (sEHI), have been shown to have therapeutic potential (Imig and Hammock, 2009; Morisseau et al., 2010; Wagner et al., 2017).

FIGURE 1.

Schematic showing different pathways for metabolizing PUFAs to oxylipins. Examples of oxylipins generated by each of the three pathways metabolizing long chain PUFAs. Shaded boxes, enzymes. Pathways affected (orange, red text) or not affected (gray, black text) by DMSO in this study.

Dimethyl sulfoxide has been shown to attenuate the accumulation of lipids in the liver as well as free fatty acid-induced cellular lipotoxicity (Song et al., 2012). However, to our knowledge, the effect of DMSO on the hepatic levels of oxygenated fatty acid metabolites such as oxylipins has not been studied. Here, we investigate the effect of a single intraperitoneal injection of DMSO on the levels of approximately 60 oxylipin species in mouse liver. Our results show that DMSO lowers the levels of certain oxylipins, all of which are diols generated by the metabolism of omega-3 and omega-6 fatty acids LA, ALA and DHA.

Materials and Methods

Animals

Care and treatment of animals were in accordance with guidelines from and approved by the University of California, Riverside Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (AUP #20140014). All mice had ad libitum access to regular vivarium chow (Purina Test Diet 5001, Newco Distributors, Rancho Cucamonga, CA) and water. At the end of the study, mice were sacrificed by CO2 inhalation followed by cervical dislocation, in accordance with stated NIH guidelines. C57BL/6N mice (Charles River Laboratories) were bred in-house and maintained on a 12h:12h light-dark cycle in a specific pathogen-free vivarium (SPF) with wood-chip bedding [PJ Murphy sani-chips 2.2 CF # 91100 (MFG 3-002)] and a cotton pad as an environmental stimulant. Pups were weaned at 3 weeks of age with three to four animals housed per cage.

DMSO Treatment

Male mice (∼18 weeks old, n = 5 per group) were injected intraperitoneally with 200 μl of 1% DMSO (Sigma-Aldrich, catalog # D5879) and sacrificed 2 h later. About 200 mg of freshly excised liver tissue was rinsed in cold phosphate buffered saline (PBS), blotted with a Kimwipe and snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen for subsequent metabolomic analysis. Samples were also collected from a control group of age-matched mice that were not injected.

Oxylipin Analysis

Non-esterified oxylipins were extracted by solid phase extraction from liver tissue homogenates (200 mg) and analyzed by ultrahigh performance liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry (UPLC-MS/MS) (Agilent 1200SL-AB Sciex 4000 QTrap) as described previously (Matyash et al., 2008; Yang et al., 2009; Deol et al., 2017). Analyst software v.1.4.2 was used to quantify peaks according to corresponding standard curves with their corresponding internal standards. Hepatic oxylipin concentrations are presented as pmol/gm tissue.

Statistical Analysis

Data are presented as mean ± standard error of mean (SEM). Statistical significance is defined as P ≤ 0.05 using Student’s t-test.

Results

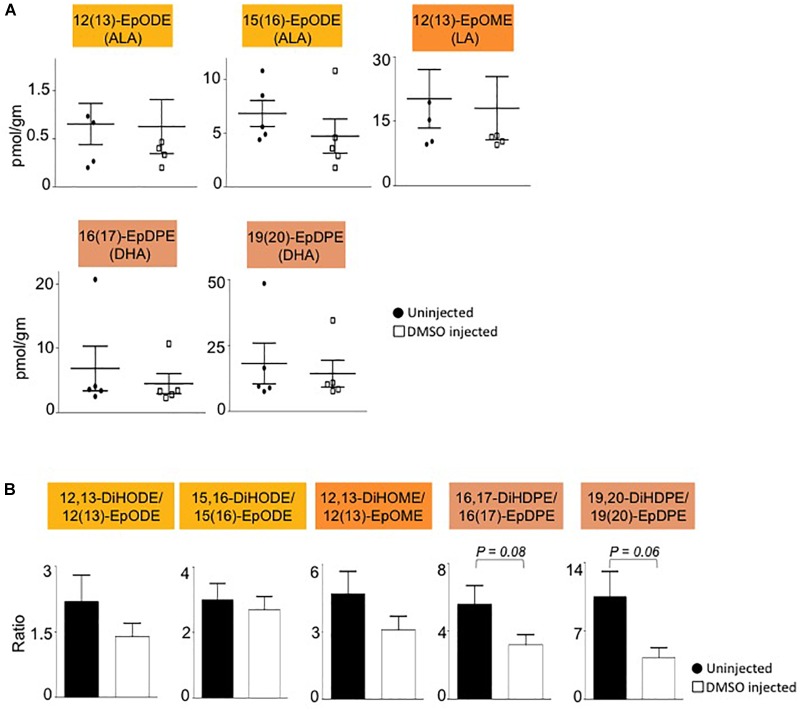

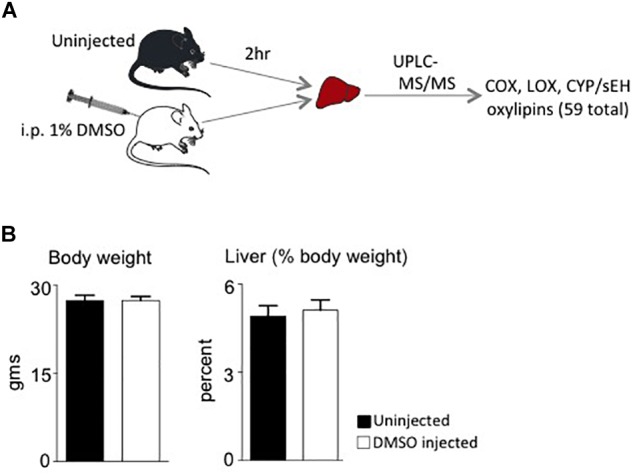

Male mice (∼18 weeks old) were injected with 1% DMSO and sacrificed 2 h later. Livers were removed and analyzed for oxylipins in the COX, LOX and CYP/sEH pathways (Figure 1, 2A). The 2-h time point was chosen to examine the short-term effects of DMSO and avoid potentially confounding factors that might be introduced by effects on gene expression. Not unexpectedly, the body weight and liver-to-body weight ratio at harvest did not differ between the control and injected groups (Figure 2B). Of the 59 oxylipin species analyzed, the DMSO-injected mice showed significantly altered levels of five species, all diols and all of which were decreased: 12,13-DiHODE, 15,16-DiHODE, 12,13-DiHOME, 16,17-DiHDPE and 19,20-DiHDPE (Figure 3). In addition, levels of two diols – 14,15-DiHETrE and 13,14-DiHDPE – were also lower in the DMSO group, although the decrease did not reach statistical significance (Supplementary Table 1).

FIGURE 2.

Study design and phenotypic data. (A) Workflow for the study showing the two cohorts of mice used and analyses performed. i.p., intraperitoneal. (B) Average body weights and liver weight as percent of body weight of male C57/BL6N mice at time of sacrifice (N = 5 per group).

FIGURE 3.

Liver oxylipin diol levels are decreased by DMSO. Absolute levels of diols that are significantly decreased in liver of mice injected with 1% DMSO (□) compared to uninjected controls (●). The fatty acid from which the oxylipin was derived is shown in parentheses. N = 5 mice per group. Data are presented as ±SEM. ∗Significantly different from uninjected control, P ≤ 0.05.

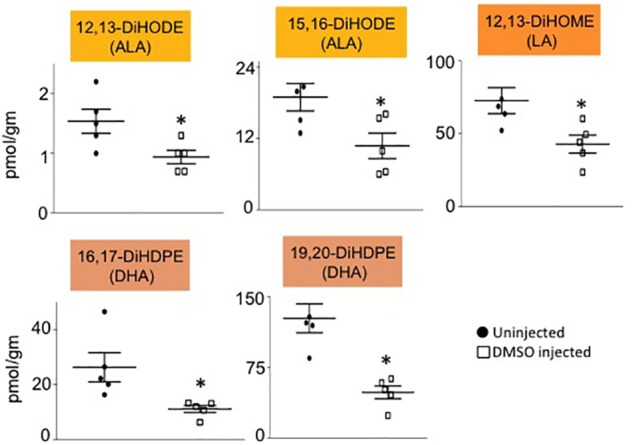

Interestingly, all of the oxylipins decreased by DMSO were in the CYP/sEH pathway and generated by hydrolysis of epoxides of LA, ALA and DHA. In contrast, levels of the epoxide precursors of these diols were not impacted by the DMSO treatment (Figure 4A). Diol:epoxide ratios, which are a reflection of sEH activity, were also not significantly different between DMSO and control, although the ratio for the DHA metabolites (DiHDPE:EpDPE) was trending toward significance (Figure 4B).

FIGURE 4.

Liver epoxide levels and diol:epoxide ratios are not affected by DMSO. (A) Absolute levels of parent epoxides of diols (shown in Figure 3) in liver of mice injected with 1% DMSO (□) compared to uninjected controls (●). The fatty acid from which the oxylipin was derived is shown in parentheses. (B) Ratio of diol:epoxide as a measure of soluble epoxide hydrolase (sEH) activity. Color coding for parental fatty acid is same as in panel (A) and Figure 3. N = 5 mice per group. Data are presented as ±SEM. Significance is defined as P ≤ 0.05.

Discussion

Dimethyl sulfoxide is widely used to treat numerous ailments although the underlying mechanisms remain obscure. Our results show that a single injection of DMSO can cause an immediate and pronounced decrease in oxylipin diols generated from certain omega-3 and omega-6 PUFAs (LA, ALA and DHA) by the CYP/sEH pathway in mouse liver. It was proposed early on that one potential mechanism responsible for the physiological effects of DMSO was its ability to inhibit or activate various enzymes by reversibly altering their configuration (Rammler and Zaffaroni, 1967). DMSO has subsequently been shown to have a stabilizing effect on the RNA transcript levels of CYP enzymes in rat liver hepatocytes (Su and Waxman, 2004), and varying effects on CYP enzymatic activity depending on concentration, substrate and tissue or cell fraction (Chauret et al., 1998; Hickman et al., 1998; Li et al., 2010). At very high concentrations (28% v/v) DMSO has been shown to interact with the iron center of a bacterial cytochrome P450 enzyme (Kuper et al., 2012). We did not observe an alteration in the level of the precursor epoxides, suggesting that DMSO is not acting on the CYP enzymes in our system. Similarly, the diol:epoxide ratio was not significantly altered, suggesting that sEH activity was not altered. Interestingly, oxylipin epoxide and diol levels of two other PUFAs, AA and EPA, were not affected by DMSO. Combined with the relatively short time period needed to observe these effects (2 h), these results suggest that DMSO acts directly, and selectively, on LA, ALA and DHA oxylipin diols (Figure 5). It remains to be determined whether chronic DMSO treatment would show a similar selective effect.

FIGURE 5.

Proposed basis for therapeutic effects of DMSO. DMSO directly reduces oxylipin diol levels in tissues and thus helps mitigate pain and other symptoms associated with diol accumulation. Solid line, known reaction; dashed line, proposed causal effect. sEHI, soluble epoxide hydrolase inhibitor. See text for details.

Since the decrease in hepatic oxylipin levels in our experiments does not appear to be due to a decrease in enzyme action, this suggests that, at least in the short term, DMSO is either decreasing the stability or somehow preventing the accumulation of these compounds in the liver. DMSO has been reported to have antioxidant and free-radical scavenging properties (Sanmartín-Suárez et al., 2011; Kabeya et al., 2013) Thus, it is possible that DMSO may be acting as a scavenger for these oxidized metabolites, converting them into products that are not present in our oxylipin panel. Indeed, it has been reported that DMSO, when used as a vehicle, enhances the anti-inflammatory effects of rosemary and ginger (Justo et al., 2015). While the authors attributed this increase to better absorption and distribution of the compounds due to DMSO, it is possible that DMSO itself could have acted as an antioxidant, as has been shown previously (Alemón-Medina et al., 2008; Jia et al., 2010). These observations, along with the current results, indicate that caution should be employed when using DMSO as a vehicle to study the pharmacological efficacy of compounds with antioxidant potential. A direct, non-enzymatic effect of DMSO also suggests that it may have a similar effect in other tissues, and hence a broad applicability to numerous pathologies.

There are two other potential explanations for the reduced levels of the oxylipin diols. The first is that DMSO affects the level of the substrates, in this case LA, ALA and DHA. However, these fatty acids are essential (or in the case of DHA, conditionally essential), meaning that they must be derived from the diet. Consequently, the body has robust mechanisms to maintain their levels (Tove and Smith, 1960; Lin and Conner, 1990; Lin et al., 1993; Calder, 2016) making it unlikely that within 2 h of injecting DMSO there would be a large decrease in the steady state levels of these essential fatty acids. Furthermore, if the levels of the parental fatty acids were decreased, one would also expect to see decreased levels of the epoxides, which is not the case. The second possibility is that the diol levels decreased not because of the DMSO but because of the stress involved with the injection. However, we did not observe such effects in mock-injected mice in previous studies (Yang et al., 2009, 2013) and it is not likely that only certain oxylipins would be so significantly changed in a general stress response.

Oxylipin diols generated from omega-6 and omega-3 fatty acids have been associated with a number of pathologies including obesity, diabetes, and inflammatory and cardiovascular diseases (Kalupahana et al., 2011; Grapov et al., 2012; Tourdot et al., 2014; Deol et al., 2017). Thus, it is not surprising that limiting the production of diols with sEH inhibitors is emerging as an important therapeutic approach in disease management (Liu et al., 2012; Bettaieb et al., 2013; Wagner et al., 2017). Decreasing oxylipin diol levels by DMSO could be used as a treatment complementary to sEHI: while inhibition of sEH would help prevent the formation of new diols, DMSO would eliminate pre-existing diols that may have accumulated prior to sEHI treatment (Figure 5). For example, DMSO has been shown to mitigate inflammation in arthritis (Elisia et al., 2016), a disease associated with elevated levels of oxylipins (He et al., 2015; de Visser et al., 2018; Valdes et al., 2018). In one of these studies, however, a decrease in LA-derived diols was suggested to be causal for arthritis (He et al., 2015), indicating that additional investigation is needed (Figure 5).

Another example where DMSO could play a unique therapeutic role is in reducing extreme obesity. We have shown previously that all five of the oxylipin diols decreased by DMSO in this study – 12,13-DiHODE, 15,16-DiHODE, 12,13-DiHOME, 16,17-DiHDPE and 19,20-DiHDPE – correlate positively with soybean oil-induced obesity in mice (Deol et al., 2017). Soybean oil is by far the most commonly used cooking oil in the United States and is used ubiquitously in processed foods and restaurants (Blasbalg et al., 2011; Ash, 2012). While avoiding excess soybean oil in the diet is obviously preferable to taking any sort of medication, it is intriguing to speculate that in cases of intractable obesity, a compound such as DMSO that decreases elevated levels of diols might have a therapeutic effect. For such a treatment to work, however, the DMSO would need to have more than a transient effect on diol levels. Preliminary data from our lab suggest that this might be the case for at least one of the diols (not shown).

In summary, the results reported here provide new insights into the potential health effects of DMSO, and heightens our awareness of potential complications when using it as a solvent for therapeutic compounds.

Ethics Statement

Care and treatment of animals were in accordance with guidelines from and approved by the University of California, Riverside Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (AUP #20140014). All mice had ad libitum access to regular vivarium chow (Purina Test Diet 5001, Newco Distributors, Rancho Cucamonga, CA) and water. At the end of the study, mice were sacrificed by CO2 inhalation followed by cervical dislocation, in accordance with stated NIH guidelines.

Author Contributions

PD and FS conceived and designed the experiments. FS and BH supervised the study. PD and JY performed the experiments. PD, CM, BH, and FS analyzed and interpreted the results. PD and FS wrote the manuscript with input from the other authors.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Funding. This work was supported by Crohn’s and Colitis Foundation of America Career Development Award (#454808) to PD; NIH R01DK053892 and USDA National Institute of Food and Agriculture (Hatch project CA-R-NEU-5680) to FS; NIEHS R01 ES002710 to BH; NIEHS P42 ES004699 to BH and a WCMC Pilot Project from NIH U24 DK097154 to FS and BH.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fphar.2019.00580/full#supplementary-material

References

- Achudume A. C. (1991). Effects of dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) on carbon (CCL4)-induced hepatotoxicity in mice. Clin. Chim. Acta 200 57–58. 10.1016/0009-8981(91)90335-a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alemón-Medina R., Muñoz-Sánchez J. L., Ruiz-Azuara L., Gracia-Mora I. (2008). Casiopeína IIgly induced cytotoxicity to HeLa cells depletes the levels of reduced glutathione and is prevented by dimethyl sulfoxide. Toxicol. In Vitro 22 710–715. 10.1016/j.tiv.2007.11.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ash M. (2012). Soybeans & Oil Crops. USDA Economic Research Service-Related Data and Statistics. Available at: http://www.ers.usda.gov/topics/crops/soybeans-oil-crops.aspx#.UkIjCBZLz-Y (accessed November 1 2016). [Google Scholar]

- Beilke M. A., Collins-Lech C., Sohnle P. G. (1987). Effects of dimethyl sulfoxide on the oxidative function of human neutrophils. J. Lab. Clin. Med. 110 91–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bettaieb A., Nagata N., AbouBechara D., Chahed S., Morisseau C., Hammock B. D., et al. (2013). Soluble epoxide hydrolase deficiency or inhibition attenuates diet-induced endoplasmic reticulum stress in liver and adipose tissue. J. Biol. Chem. 288 14189–14199. 10.1074/jbc.M113.458414 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blasbalg T. L., Hibbeln J. R., Ramsden C. E., Majchrzak S. F., Rawlings R. R. (2011). Changes in consumption of omega-3 and omega-6 fatty acids in the United States during the 20th century. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 93 950–962. 10.3945/ajcn.110.006643 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brayton C. F. (1986). Dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO): a review. Cornell Vet. 76 61–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calder P. C. (2016). Docosahexaenoic acid. Ann. Nutr. Metab. 69(Suppl. 1) 7–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caligiuri S. P. B., Parikh M., Stamenkovic A., Pierce G. N., Aukema H. M. (2017). Dietary modulation of oxylipins in cardiovascular disease and aging. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 313 H903–H918. 10.1152/ajpheart.00201.2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chauret N., Gauthier A., Nicoll-Griffith D. A. (1998). Effect of common organic solvents on in vitrocytochrome P450-mediated metabolic activities in human liver microsomes. Drug Metab. Dispos. 26 1–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Visser H. M., Mastbergen S. C., Ravipati S., Welsing P. M. J., Pinto F. C., Lafeber F. P. J. G., et al. (2018). Local and systemic inflammatory lipid a profiling in a rat model of osteoarthritis with metabolic dysregulation. PLoS One 13:e0196308. 10.1371/journal.pone.0196308 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deol P., Fahrmann J., Yang J., Evans J. R., Rizo A., Grapov D., et al. (2017). Omega-6 and omega-3 oxylipins are implicated in soybean oil-induced obesity in mice. Sci. Rep. 7:12488. 10.1038/s41598-017-12624-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elisia I., Nakamura H., Lam V., Hofs E., Cederberg R., Cait J., et al. (2016). DMSO represses inflammatory cytokine production from human blood cells and reduces autoimmune arthritis. PLoS One 11:e0152538. 10.1371/journal.pone.0152538 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gouveia-Figueira S., Nording M. L., Gaida J. E., Forsgren S., Alfredson H., Fowler C. J. (2015). Serum levels of oxylipins in achilles tendinopathy: an exploratory study. PLoS One 10:e0123114. 10.1371/journal.pone.0123114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grapov D., Adams S. H., Pedersen T. L., Garvey W. T., Newman J. W. (2012). Type 2 diabetes associated changes in the plasma non-esterified fatty acids, oxylipins and endocannabinoids. PLoS One 7:e48852. 10.1371/journal.pone.0048852 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo Q., Wu Q., Bai D., Liu Y., Chen L., Jin S., et al. (2016). Potential use of dimethyl sulfoxide in treatment of infections caused by Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 60 7159–7169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He M., van Wijk E., Berger R., Wang M., Strassburg K., Schoeman J. C., et al. (2015). Collagen induced arthritis in DBA/1J mice associates with oxylipin changes in plasma. Mediat. Inflamm. 2015:543541. 10.1155/2015/543541 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hennebelle M., Otoki Y., Yang J., Hammock B. D., Levitt A. J., Taha A. Y., et al. (2017). Altered soluble epoxide hydrolase-derived oxylipins in patients with seasonal major depression: an exploratory study. Psychiatry Res. 252 94–101. 10.1016/j.psychres.2017.02.056 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hickman D., Wang J. P., Wang Y., Unadkat J. D. (1998). Evaluation of the selectivity of In vitro probes and suitability of organic solvents for the measurement of human cytochrome P450 monooxygenase activities. Drug Metab. Dispos. 26 207–215. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imig J. D., Hammock B. D. (2009). Soluble epoxide hydrolase as a therapeutic target for cardiovascular diseases. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 8 794–805. 10.1038/nrd2875 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwasaki T., Hamano T., Aizawa K., Kobayashi K., Kakishita E. (1994). A case of pulmonary amyloidosis associated with multiple myeloma successfully treated with dimethyl sulfoxide. Acta Haematol. 91 91–94. 10.1159/000204262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jia Z., Zhu H., Li Y., Misra H. P. (2010). Potent inhibition of peroxynitrite-induced DNA strand breakage and hydroxyl radical formation by dimethyl sulfoxide at very low concentrations. Exp. Biol. Med. 235 614–622. 10.1258/ebm.2010.009368 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Justo O. R., Simioni P. U., Gabriel D. L., Tamashiro W. M., Rosa, Pde T. V, Moraes ÂM. (2015). Evaluation of in vitro anti-inflammatory effects of crude ginger and rosemary extracts obtained through supercritical CO2 extraction on macrophage and tumor cell line: the influence of vehicle type. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 15:390. 10.1186/s12906-015-0896-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kabeya L. M., Andrade M. F., Piatesi F., Azzolini A. E. C. S., Polizello A. C. M., Lucisano-Valim Y. M. (2013). 3,3′,5,5′-Tetramethylbenzidine in hypochlorous acid and taurine chloramine scavenging assays: interference of dimethyl sulfoxide and other vehicles. Anal. Biochem. 437 130–132. 10.1016/j.ab.2013.02.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalupahana N. S., Claycombe K. J., Moustaid-Moussa N. (2011). (n-3) Fatty acids alleviate adipose tissue inflammation and insulin resistance: mechanistic insights. Adv. Nutr. 2 304–316. 10.3945/an.111.000505 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelava T., Ćavar I., Čulo F. (2011). Biological actions of drug solvents. Period. Biol. 113 311–320. [Google Scholar]

- Kingery W. S. (1997). A critical review of controlled clinical trials for peripheral neuropathic pain and complex regional pain syndromes. Pain 73 123–139. 10.1016/s0304-3959(97)00049-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar S., Kumar S., Ganesamoni R., Mandal A. K., Prasad S., Singh S. K. (2011). Dimethyl sulfoxide with lignocaine versus eutectic mixture of local anesthetics: prospective randomized study to compare the efficacy of cutaneous anesthesia in shock wave lithotripsy. Urol. Res. 39 181–183. 10.1007/s00240-010-0324-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuper J., Tee K. L., Wilmanns M., Roccatano D., Schwaneberg U., Wong T. S. (2012). The role of active-site Phe87 in modulating the organic co-solvent tolerance of cytochrome P450 BM3 monooxygenase. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. F Struct. Biol. Cryst. Commun. 68 1013–1017. 10.1107/S1744309112031570 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levick S. P., Loch D. C., Taylor S. M., Janicki J. S. (2007). Arachidonic acid metabolism as a potential mediator of cardiac fibrosis associated with inflammation. J. Immunol. 178 641–646. 10.4049/jimmunol.178.2.641 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li D., Han Y., Meng X., Sun X., Yu Q., Li Y., et al. (2010). Effect of regular organic solvents on cytochrome P450-mediated metabolic activities in rat liver microsomes. Drug Metab. Dispos. 38 1922–1925. 10.1124/dmd.110.033894 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin D. S., Conner W. E. (1990). Are the n-3 fatty acids from dietary fish oil deposited in the triglyceride stores of adipose tissue? Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 51 535–539. 10.1093/ajcn/51.4.535 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin D. S., Connor W. E., Spenler C. W. (1993). Are dietary saturated, monounsaturated, and polyunsaturated fatty acids deposited to the same extent in adipose tissue of rabbits? Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 58 174–179. 10.1093/ajcn/58.2.174 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lind R. C., Begay C. K., Gandolfi A. J. (2000). Hepatoprotection by dimethyl sulfoxide: III. Role of inhibition of the bioactivation and covalent binding of chloroform. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 166 145–150. 10.1006/taap.2000.8949 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lishner M., Lang R., Kedar I., Ravid M. (1985). Treatment of diabetic perforating ulcers (Mal Perforant) with local dimethylsulfoxide. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 33 41–43. 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1985.tb02858.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y., Dang H., Li D., Pang W., Hammock B. D., Zhu Y. (2012). Inhibition of soluble epoxide hydrolase attenuates high-fat-diet–induced hepatic steatosis by reduced systemic inflammatory status in mice. PLoS One 7:e39165. 10.1371/journal.pone.0039165 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massion P. P., Lindén A., Inoue H., Mathy M., Grattan K. M., Nadel J. A. (1996). Dimethyl sulfoxide decreases interleukin-8-mediated neutrophil recruitment in the airways. Am. J. Physiol. 271 L838–L843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matyash V., Liebisch G., Kurzchalia T. V., Shevchenko A., Schwudke D. (2008). Lipid extraction by methyl-tert-butyl ether for high-throughput lipidomics. J. Lipid Res. 49 1137–1146. 10.1194/jlr.D700041-JLR200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moghaddam M. F., Grant D. F., Cheek J. M., Greene J. F., Williamson K. C., Hammock B. D. (1997). Bioactivation of leukotoxins to their toxic diols by epoxide hydrolase. Nat. Med. 3 562–566. 10.1038/nm0597-562 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morisseau C., Inceoglu B., Schmelzer K., Tsai H.-J., Jinks S. L., Hegedus C. M., et al. (2010). Naturally occurring monoepoxides of eicosapentaenoic acid and docosahexaenoic acid are bioactive antihyperalgesic lipids. J. Lipid Res. 51 3481–3490. 10.1194/jlr.M006007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park Y., Smith R. D., Combs A. B., Kehrer J. P. (1988). Prevention of acetaminophen-induced hepatotoxicity by dimethyl sulfoxide. Toxicology 52 165–175. 10.1016/0300-483x(88)90202-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pepin J. M., Langner R. O. (1985). Effects of dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) on bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis. Biochem. Pharmacol. 34 2386–2389. 10.1016/0006-2952(85)90799-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rammler D. H., Zaffaroni A. (1967). Biological implications of dmso based on a review of its chemical properties. Ann N. Y. Acad. Sci. 141 13–23. 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1967.tb34861.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rawls W. F., Cox L., Rovner E. S. (2017). Dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) as intravesical therapy for interstitial cystitis/bladder pain syndrome: a review. Neurourol. Urodyn. 36 1677–1684. 10.1002/nau.23204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sahin M., Avsar F. M., Ozel H., Topaloglu S., Yilmaz B., Pasaoglu H., et al. (2004). The effects of dimethyl sulfoxide on liver damage caused by ischemia-reperfusion. Transplant. Proc. 36 2590–2592. 10.1016/j.transproceed.2004.09.057 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salim A. S. (1991). Protection against stress-induced acute gastric mucosal injury by free radical scavengers. Intensive Care Med. 17 455–460. 10.1007/bf01690766 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salim A. S. (1992a). Oxygen-derived free-radical scavengers prolong survival in colonic cancer. Chemotherapy 38 127–134. 10.1159/000238952 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salim A. S. (1992b). Role of oxygen-derived free radical scavengers in the management of recurrent attacks of ulcerative colitis: a new approach. J. Lab. Clin. Med. 119 710–717. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanmartín-Suárez C., Soto-Otero R., Sánchez-Sellero I., Méndez-Álvarez E. (2011). Antioxidant properties of dimethyl sulfoxide and its viability as a solvent in the evaluation of neuroprotective antioxidants. J. Pharmacol. Toxicol. Methods 63 209–215. 10.1016/j.vascn.2010.10.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shirley S. W., Stewart B. H., Mirelman S. (1978). Dimethyl sulfoxide in treatment of inflammatory genitourinary disorders. Urology 11 215–220. 10.1016/0090-4295(78)90118-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegers C.-P. (1978). Antidotal effects of dimethyl sulphoxide against paracetamol-, bromobenzene-, and thioacetamide-induced hepatotoxicity. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 30 375–377. 10.1111/j.2042-7158.1978.tb13260.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song Y. M., Song S.-O., Jung Y.-K., Kang E.-S., Cha B. S., Lee H. C., et al. (2012). Dimethyl sulfoxide reduces hepatocellular lipid accumulation through autophagy induction. Autophagy 8 1085–1097. 10.4161/auto.20260 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su T., Waxman D. J. (2004). Impact of dimethyl sulfoxide on expression of nuclear receptors and drug-inducible cytochromes P450 in primary rat hepatocytes. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 424 226–234. 10.1016/j.abb.2004.02.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tourdot B. E., Ahmed I., Holinstat M. (2014). The emerging role of oxylipins in thrombosis and diabetes. Front. Pharmacol. 4:176. 10.3389/fphar.2013.00176 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tove S. B., Smith F. H. (1960). Changes in the fatty acid composition of the depot fat of mice induced by feeding oleate and linoleate. J. Nutr. 71 264–272. 10.1093/jn/71.3.264 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valdes A. M., Ravipati S., Pousinis P., Menni C., Mangino M., Abhishek A., et al. (2018). Omega-6 oxylipins generated by soluble epoxide hydrolase are associated with knee osteoarthritis. J. Lipid Res. 59 1763–1770. 10.1194/jlr.P085118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner K. M., McReynolds C. B., Schmidt W. K., Hammock B. D. (2017). Soluble epoxide hydrolase as a therapeutic target for pain, inflammatory and neurodegenerative diseases. Pharmacol. Ther. 180 62–76. 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2017.06.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang J., Schmelzer K., Georgi K., Hammock B. D. (2009). Quantitative profiling method for oxylipin metabolome by liquid chromatography electrospray ionization tandem mass spectrometry. Anal. Chem. 81 8085–8093. 10.1021/ac901282n [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang J., Solaimani P., Dong H., Hammock B., Hankinson O. (2013). Treatment of mice with 2,3,7,8-Tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin markedly increases the levels of a number of cytochrome P450 metabolites of omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids in the liver and lung. J. Toxicol. Sci. 38 833–836. 10.2131/jts.38.833 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeldin D. C. (2001). Epoxygenase pathways of arachidonic acid metabolism. J. Biol. Chem. 276 36059–36062. 10.1074/jbc.r100030200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.