Abstract

Rupture of a pseudoaneurysm (PA) has been reported as a rare but serious adverse event associated with endoscopic biliary stenting. We herein report 2 cases of severe biliary bleeding from a PA that developed 10-14 days after placement of a self-expandable metallic stent (SEMS) for biliary malignancy. The first patient was successfully embolized with endovascular coiling. However, the second patient had wide-spreading cholangiocarcinoma and, despite being treated once by full coiling, developed a second rupture of PA two months after starting systemic chemotherapy. Clinicians should be aware of the possibility of PA and carefully follow stented patients after endovascular treatment.

Keywords: biliary stenting, pseudoaneurysm, rupture, treatment, TAE

Introduction

Endoscopic biliary stenting (EBS) is a standard treatment for malignant biliary obstruction. However, EBS placement is associated with several adverse events, including pancreatitis, liver abscess, and migration of the stent. Although the incidence is very rare, rupture of a pseudoaneurysm (PA) has been also reported as a potentially life-threatening complication after EBS and requires prompt endoscopic and/or endovascular treatment (1, 2).

We herein report two cases of severe biliary bleeding from a PA that developed after the endoscopic placement of a biliary self-expandable metallic stent (SEMS).

Case Reports

Case 1

A 72-year-old woman who had been undergoing chemotherapy for the past year and had since chosen best supportive care was admitted to our hospital for the treatment of a biliary obstruction due to the metastasis of her gastric cancer.

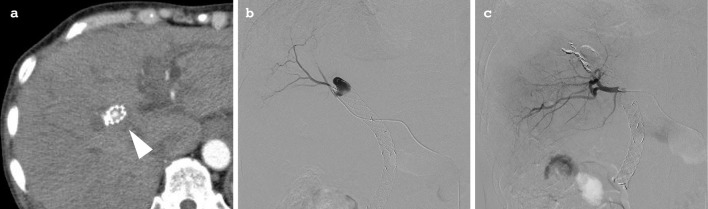

Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) demonstrated multiple stenoses within the hilar and common bile duct (Fig. 1a), and 2 SEMSs (a 10 mm×8 cm, uncovered Niti-S™ Large Cell D-type and a 10 mm×6 cm fully covered Supremo, both from TaeWoong Medical, Gimpo, South Korea) were placed (Fig. 1b) after a forceps biopsy of the lower bile duct. The histology of the biopsy sample confirmed moderately to poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma, compatible with the metastasis of gastric cancer. Fourteen days later, the patient developed a fever, jaundice, and anemia for five days. Contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) revealed a PA at the upper edge of the biliary stent, 16×11 mm in size (Fig. 2a). Angiography was urgently performed, and a PA identified at the branch of the right hepatic artery was embolized with multiple coils (Fig. 2b and c).

Figure 1.

Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) views of case 1. ERCP demonstrating multiple stenoses within the hilar and common bile duct (arrowhead) (a). The diameter of bile duct was 10 mm. Two self-expandable metallic stents (SEMS) were placed in series from the intrahepatic bile duct to the duodenum (b).

Figure 2.

Computed tomography (CT) and angiography of case 1. CT showing a pseudoaneurysm (PA) (arrowhead) within the biliary stent (a). A selective right hepatic artery angiogram demonstrating the PA before (b) and after (c) coil embolization.

The patient subsequently demonstrated no evidence of hemobilia or cholangitis, and her bleeding was controlled. However, she died of gastric cancer progression two months after the coil embolization.

Case 2

A 70-year-old man with a widely spreading biliary stricture underwent ERCP (Fig. 3a), a biliary forceps biopsy, and naso-biliary drainage placement. Tissue obtained by the biopsy revealed invasive tubular adenocarcinoma that led to the clinical diagnosis of cholangiocarcinoma. Subsequent gadoxetate-sodium-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) revealed multiple metastases, indicating a need for metallic stent placement but not surgical resection. ERCP was performed. After biliary balloon dilation (Hurricain™ RX Catheter, 8 mm; Boston Scientific, Marlborough, USA), 2 SEMSs (both uncovered Niti-S™ Large Cell D-type stents, 10 mm×8 cm and 10 mm×6 cm) were placed in a partial stent-in-stent formation in the left and right hepatic ducts to the lower common bile duct (Fig. 3b).

Figure 3.

ERCP images of case 2. ERCP demonstrating a long stretch of stenosis in the common bile duct (a). The diameter of the bile duct was 8 mm. Two SEMSs were placed in a partial stent-in-stent formation from the left and right hepatic ducts to the lower common bile duct.

One week after the biliary stenting, the patient developed a fever that lasted a few days along with epigastric pain and melena. Esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) revealed no evidence of bleeding, including from the major papilla.

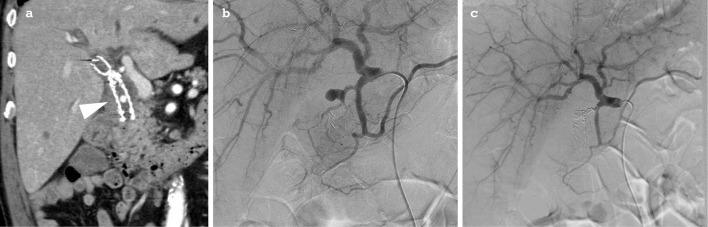

Two days after EGD, the patient developed hematemesis, and enhanced CT was performed to search for abnormal vascular lesions. CT revealed a PA arising from the posterior superior branch of pancreatoduodenal artery (Fig. 4a) and protruding into the stent. This PA had not been detected by the previous session of enhanced MRI. Emergency angiography was performed, and the aneurysm was fully embolized with multiple coils until the blood inflow was arrested (Fig. 4b and c).

Figur 4.

CT and angiography of case 2. CT showing a PA arising from the posterior superior branch of the pancreatoduodenal artery, recognized as being within the SEMS (arrowhead) (a). Angiography demonstrating an aneurysm of the posterior superior branch of the pancreatoduodenal artery (b) and the cessation of inflow after coil embolization (c).

The patient showed no further signs of gastrointestinal bleeding, and systemic chemotherapy was initiated with gemcitabine (1,000 mg/m2/week, day 1, 8, 15 in 4 weeks). However, two months later, the patient died from hematemesis, probably due to the recurrence of biliary PA.

Discussion

Endoscopic biliary stenting is widely applied for the treatment of malignant biliary strictures, and a SEMS is often used in unresectable cases. Biliary stenting is associated with several complications, including pancreatitis, cholangitis, cholecystitis, perforation, and hemorrhaging, which develop in 7-24% of stent cases (2-5). PA is a rarely reported complication after biliary stenting; however, rupture of a PA may be a life-threatening event.

Although the actual incidence is not known with accuracy, a PubMed keywords survey during 2003 and 2018 using “pseudoaneurysm” and “biliary stent,” revealed 18 cases with ruptured PA in association with biliary stenting (Table). The cause of PA is not clear. These PAs arise from various levels of arteries (i.e. right or left hepatic artery, gastroduodenal artery, and pancreatoduodenal artery) depending on their lesions. Interestingly, PA has developed even in cases with benign strictures and plastic stent placements (6-19), and the duration from the biliary stenting reportedly ranges from five days to two years (6, 11). In malignant cases, the causal arteries are often involved in the tumors; therefore, their running direction and fragility are altered. Even a superficial forceps biopsy can cause pulsative arterial bleeding (20). In addition to the mucosal necrosis due to cancer invasion, luminal compression by the stents and the effects of chemotherapies before and after the stenting are considered risk factors for PA rupture. The PA was located at the severely narrowed hepatic hilar portion, which corresponded to the central part of the SEMS, thus suggesting the presence of high compression on the arterial wall due to the expansion of the metallic stent. In addition, some reported cases (including the two present cases) have had cholangitis before PA rupture (Table), suggesting that cholangitis may also be a cause of the development of PA.

Table.

Reported Cases of Pseudoaneurysm Ruptured after the Billiary Stenting (literature Review).

| Case no. | Ref. no. | Age | Gender | Disease | Treatment for cancer | Stent kinds | diameter | Stenosis Part | Prior Colangitis | Pseudoaneurysm | Rupture of pseudoaneurysm | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Location | Size (mm) |

Symptoms | Duration* | Treatment | Re- bleeding |

Death | |||||||||||

| 1 | 6 | 47 | F | lymphoma | CRT | SEMS+ PS | unknown | CBD | presence | RHA | ND | melena | 2 years | TAE, surgery | none | no | |

| 2 | 7 | 62 | F | hilar cholangiocarcinoma | CRT | PS | 10Fr | HH | presence | LHA | 20 | fever, jaundice | 1 month | TAE | none | no | |

| 3 | 8 | 68 | F | hilar cholangiocarcinoma | ND | PS | 8.5Fr | HH | presence | RHA | ND | melena, jaundice | 20 days | TAE | none | no | |

| 4 | 9 | 70 | M | extrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma | CT | SEMS | 10mm | CBD | presence | RHA | 9×6 | abdminal pain, jaundice | 9 months | TAE | none | no | |

| 5 | 10 | 48 | M | pancreatic cancer | CRT → CT | SEMS | 10mm | CBD | absence | RHA | ND | melena, jaudice | 8 months | TAE | none | no | |

| 6 | 11 | 72 | M | pancreatic cancer | CRT | SEMS | 10mm | CBD | presence | RHA | ND | hemetamesis, melena | 5 days | none | yes | yes | |

| 7 | 82 | F | pancreatic cancer | none | SEMS | 10mm | CBD | absence | PAPDA | ND | hemetamesis | 20 days | TAE | none | no | ||

| 8 | 80 | M | gallbladder carcinoma | CT | SEMS | 10mm | CBD | absence | RHA | ND | hemetamesis, melena | 6 months | TAE | none | no | ||

| 9 | 12 | 51 | M | pancreatic cancer | ND | SEMS | unknown | CBD | ND | GDA | ND | melena | 76 days | TAE | none | no | |

| 10 | 65 | M | gallbladder carcinoma | ND | SEMS | unknown | CBD | ND | GDA | ND | melena | 15 days | TAE | none | no | ||

| 11 | 72 | M | hilar cholangiocarcinoma | ND | SEMS | unknown | HH | ND | RHA | ND | hemetamesis | 152 days | TAE, surgery | none | no | ||

| 12 | 13 | 60s | M | pancreatic cancer | CRT → CT | SEMS | 10mm | CBD | absence | RHA | 8 | jaundice, shock | 6 months | TAE | none | no | |

| 13 | 14 | 78 | M | pancreatic cancer | CRT | SEMS | unknown | CBD | ND | GDA | ND | melena, shock | 4 months | TAE | none | no | |

| 14 | 15 | 75 | M | pancreatic cancer | ND | SEMS | 10 mm | CBD | absence | GDA | 8 | melena, abdominal pain | 1 month | TAE | none | no | |

| 15 | 16 | 47 | M | post-surgical bile leaks | NA | PS | 11.5Fr and 7Fr | NA | absence | RHA | ND | melena | ND | TAE | none | no | |

| 16 | 17 | 78 | F | biliary stone | NA | PS | unknown | NA | presence | RHA | 13×10 | hemetameis | 1 year | TAE | yes | no | |

| 17 | 18 | 56 | M | obstructive jaundice after hepatitis | NA | PS | unknown | CBD | absence | LHA | 11.6×9.7 | hemetamesis | 13 days | TAE | none | no | |

| 18 | 19 | 78 | F | benign biliary stenosis | NA | PS | unknown | B3 | presence | LHA | 3 | jaudice, fever | 14 days | TAE | none | no | |

| 19 | Current cases | 72 | F | obstructive jaundice by metastasis | CT | SEMS | 10 mm | HH, CBD | presence | RHA | 16×11 | jaundice, fever | 14 days | TAE | none | no | |

| 20 | 70 | M | extrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma | CT | SEMS | 10 mm | CBD | presence | PSPDA | 8×7 | epigastric pain, melena | 10 days | TAE | yes | yes | ||

CBD: comon hepatic duct, CRT: chemoradiotherapy, CT: chemotherapy, ND: not described, NA: not applicable, SEMS: self-expandable metallic stents, PS: plastic stent , RHA: right hepatic artely, LHA: left hepatic artely, PSPDA: posterior superior pancreaticoduodenal artery, GDA: gastroduodenal artery, TAE: transarterial embolization

*Duration: duration from stenting to bleeding

The treatment of a ruptured biliary PA is usually conservative and can include blood transfusion, transarterial embolization (TAE), and surgery. To date, no consensus has been reached concerning the priority of TAE and surgical treatments. However, when taking the physical invasiveness and the physical condition of patients with an advanced stage of cancer into consideration, TAE is viewed as the first therapeutic choice for most cases. In fact, most reported cases have been treated with intravascular therapy and have shown good outcomes (Table). Among the 19 reported TAE-treated cases, including the present ones, only 2 cases (case 16 and case 20 in Table) showed recurrences. Yasuda et al. (17) reported a 78-year-old case (case 16) accompanied by an arterial-biliary fistula that developed re-rupture of the PA after the initial session of TAE. In that case, chemotherapy had not been performed, but a biliary stent had been placement for a year without the removal of common bile duct (CBD) stones. The authors speculated that the accompanying cholangitis and CBD stones were associated with the PA formation. In our case, the administration of two courses of systemic chemotherapy with gemcitabine may have affected the fragility and neovascularity of the biliary wall. The accumulation of more cases is needed for the further assessment of the risk factors for recurrence. At present, continuing follow-up with enhanced CT is recommend after stent placement for malignant biliary obstruction.

In cases of postsurgical biliary PA, SEMS placement is reported to be an effective treatment (21, 22). Cases of post-stenting PA all develop biliary bleeding, so a covered SEMS might be a useful tool for achieving pressure hemostasis and may be a viable treatment choice. However, as mentioned, the pressure from a self-expanding stent may conversely induce the subsequent development of a PA. Therefore, the utility of SEMS treatment requires further validation.

The current study reported two cases of a ruptured PA following metallic stent placement for the treatment of a malignant biliary stricture. Thus far, no effective preventative strategy for PA formation has been described. However, post-stenting imaging screening can reduce the incidence of PA rupture by prophylactic TAE. Rupture of a biliary PA can be a life-threatening event; however, TAE appears to be an effective hemostatic treatment.

The authors state that they have no Conflict of Interest (COI).

References

- 1.Kullman E, Frozanpor F, Soderlund C, et al. Covered versus uncovered self-expandable nitinol stents in the palliative treatment of malignant distal biliary obstruction: results from a randomized, multicenter study. Gastrointest Endosc 72: 915-923, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Christensen M, Matzen P, Schulze S, Rosenberg J. Complications of ERCP: a prospective study. Gastrointest Endosc 60: 721-731, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rossi P, Bezzi M, Salvatori FM, Maccioni F, Porcaro ML. Recurrent benign biliary strictures: management with self-expanding metallic stents. Radiology 175: 661-665, 1990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tesdal I, Jaschke W, Duber C, Werhand J, Klose K. Biliary stenting: self-expandable and balloon-expandable stent. Early and late results. In: Stents-State of the Art and Future Developments. Liermann D, Ed. Polyscience Publications Inc., Canada, 1995: 190-195. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Matsubayashi H, Fukutomi A, Kanemoto H, et al. Risk of pancreatitis after endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography and endoscopic biliary drainage. HPB (Oxford) 11: 222-228, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rai R, Rose J, Manas D. Potentially fatal heamobilia due to inappropriate use of an expanding biliary stent. World J Gastroenterol 9: 2377-2378, 2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Park JY, Ryu H, Bang S, et al. Hepatic artery pseudoaneurysm associated with plastic biliary stent. Yonsei Medical Journal 48: 546-548, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Inoue H, Tano S, Takayama R, et al. Right hepatic artery psudoaneurysm: rare complication of plastic biliary stent insertion. Endoscopy 43: E396, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Watanabe M, Shiozawa K, Mimura T, et al. Hepatic artery pseudoaneurysm after endoscopic biliary stenting for bile duct cancer. World J Radiol 28: 115-120, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Morishita N, Nishida T, Hayashi Y, et al. Hemobilia into a metalic biliary stent due to pseudoaneurysm: a case report. Nihon Shokakibyo Gakkai Zasshi 43: 571-574, 2013(in Japanease, Abstract in English). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nedu Y, Nakaji S, Fujii H, et al. Pseudoaneurysm caused by a self-expandable metal stent: a report of three cases. Endoscopy 46: 248-251, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hyun D, Park KB, Hwang JC, et al. Delayed, life-threatening hemorrhage after self-expandable metallic biliary stent placement: clinical manifestations and endovascular treatment. Acta Radiologica 53: 939-943, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Asayama N, Sasaki T, Serikawa M, et al. Hepatic artery pseudoaneurysm after endoscopic biliary stenting for pancreatic cancer. Nihon Shokakibyo Gakkai Zasshi 111: 931-939, 2014(in japanease, Abstract in English). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Raja A, Papadopoulou A, Gillmore R. Pseudoaneurysm development after stenting for malignant biliary obstruction. Dig Liver Dis 47: 726, 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Inchingolo R, Nestola M, Posa A, et al. Intrastent pseudoaneurysm following endoscopic biliary stent insertion. J Vasc Interv Radiol 28: 1321-1323, 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chun JM, Ha HT, Choi YY, et al. Intrahepatic artery pseudoaneurysm-induced hemobilia caused by a plastic biliary stent after ABO-incompatible living-donor liver transplantation: a case report. Transplant Proc 48: 3178-3180, 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yasuda M, Sato H, Koyama Y, et al. Late-onset severe biliary bleeding after endoscopic pigtail plastic stent insertion. World J Gastroenterol 28: 735-739, 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ding Z, Tang XL, Lin R, et al. ERCP-related complication is not the only cause of GI bleeding in post-liver transpantation patients. Medicine 96: e7716, 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yamauchi K, Uchida D, Kato H, et al. Recurrent bleeding from a hepatic artery pseudoaneurysm after biliary stent placement. Intern Med 57: 49-52, 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shinjo K, Matsubayashi H, Matsui T, et al. Biliary hemostasis using an endoscopic plastic stent placement for uncontrolled hemobilia caused by transpapillary forceps biopsy (with video). Clin J Gastroenterol 9: 86-88, 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Herzog T, Suelberg D, Belyaev O, Uhl W, Seemann M, Seelig MH. Treatment of acute delayed visceral hemorrhage after pancreatic surgery from hepatic arteries with covered stents. J Gastrointest Surg 15: 496-502, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ichihara T, Sato T, Miyazawa H, et al. Stent placement is effective on both postoperative hepatic arterial pseudoaneurysm and subsequent portal vein stricture: a case report. World J Gastroenterol 13: 970-972, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]