Abstract

This secondary analysis of a randomized clinical trial examines the association of antipsychotic overuse letters with changes in the prescription of quetiapine by physician peers.

Physicians learn about new medical evidence from their peers.1,2 Interventions that can stem overuse in some physicians could therefore spur systemwide change through peer networks as physicians discuss new practice styles and learn from each other. One source of overuse is antipsychotic prescribing: these drugs are widely prescribed to people with dementia even though guidelines discourage this practice.3 A randomized clinical trial of antipsychotic overuse letters that were sent by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) to high prescribers of quetiapine reduced prescribing by targeted physicians by 16% over 2 years (NCT02467933).4 This study examines whether these letters led to changes in prescribing by peers of the original physicians, which would suggest that overuse interventions can have broader effects.

Methods

During April 2015 to August 2015, 5055 high-volume primary care physician (PCP) prescribers (“study PCPs”) of quetiapine were randomized to receive a series of 3 letters mailed from CMS about their prescribing patterns (treatment) or a pair of letters about a separate Medicare regulation (control). The treatment letters compared the PCP’s quetiapine prescribing with other PCPs and stated that they were under review by CMS.

We analyzed effects on peers who prescribed quetiapine in 2014 and worked with the original study PCPs. Peers were identified as other practitioners in study PCPs’ group practices or other practitioners who treated 11 or more patients in common with any study PCP (with each patient treated by both practitioners within 30 days). Peers linked to at least 1 study PCP in the original treatment group were considered treated while the remainder were controls. The institutional review boards of Columbia University and the National Bureau of Economic Research approved this study and waived informed consent given the retrospective nature of the analyses.

The prespecified primary outcome was quetiapine months supplied during 2015 and 2016, which was analyzed using multivariable linear regression with randomization-based inference to account for the interdependency of outcomes within peer networks. We adjusted for peers’ number of ties to original study PCPs because this determined the probability of being treated through peer networks.5 After adjustment, given the randomization of the original intervention, whether a peer worked with a treated or control PCP was random.

Results

There were 7563 peer practitioners who shared a group practice with original study PCPs (8989 who shared patients). Of these, 5582 group practice peers (73.8%) were PCPs and 632 (8.4%) had psychiatric specialization (5942 [66.1%] and 668 [7.4%], respectively, for shared patient peers). The average group practice peer was linked to 1.4 original study PCPs and 0.7 treated original study PCPs (1.3 and 0.7 PCPs, respectively, for shared patient peers).

Although the intervention was associated with a decrease in prescribing by the original study PCPs (33.6 fewer months supplied; 95% CI, 27.0-40.2; P < .001; 12.9% relative decrease), we failed to detect a significant association between the intervention and prescribing by peer practitioners (Figures 1 and 2). For group practice peers, adjusted quetiapine prescribing was 2.2 months lower (95% CI, 5.5 lower to 1.1 higher; P = .20) or 2.2% for treated vs control. For shared patient peers, prescribing was 1.3 months lower (95% CI, 5.6 lower to 3.0 higher; P = .55) or 1.0%. We failed to detect associations with all other prespecified antipsychotic prescribing outcomes for peer practitioners, including the prescription of all antipsychotics.

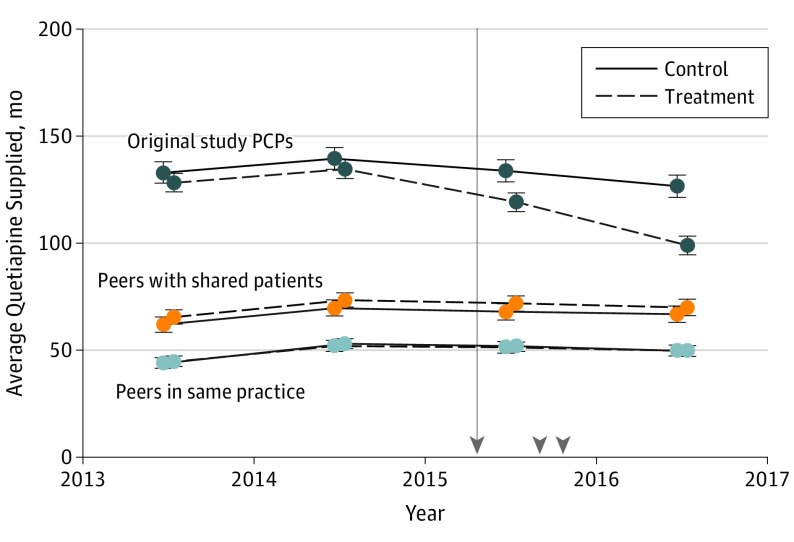

Figure 1. Annual Average Quetiapine Prescribing by Original Study Primary Care Physicians (PCPs) and Peers in Treatment and Control Groups.

Each point represents the average months of quetiapine supplied in each year per prescriber. Because peers linked to more original study PCPs are more likely to be considered treated, the averages for treatment and control groups are inverse probability of treatment weighted using the number of original study PCPs with whom peers were associated. Error bars indicate 95% confidence intervals. See the estimates in Figure 2 for error bars that account for interdependency across peers. The vertical line denotes the intervention start date and arrowheads denote when treatment letters were sent to prescribers.

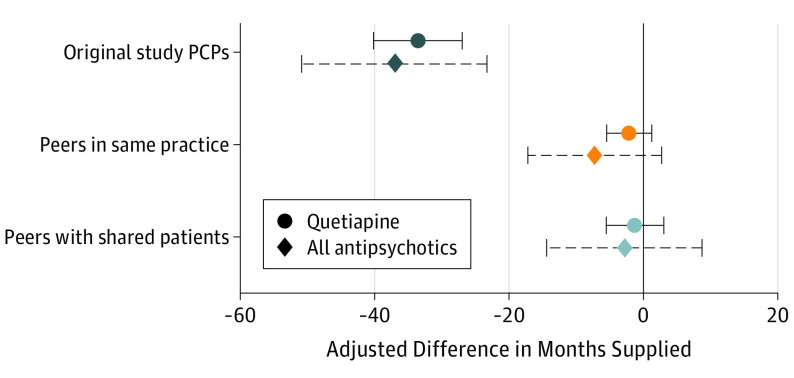

Figure 2. Association of Intervention With Antipsychotic Prescribing by Original Study Primary Care Physicians (PCPs) and Peers During 2015 and 2016.

Points show the difference in average months of antipsychotics supplied between treatment and control PCPs in the original study and between treatment and control peers of original study PCPs during 2015 and 2016. Each point reports an adjusted difference (the difference between treatment and control means after adjusting for control variables). All estimates were adjusted for months of antipsychotics supplied in 2014 to raise statistical power. Because peers who were linked to more original study PCPs were more likely to be considered treated, peer estimates were adjusted for the number of original study PCPs with whom peers were associated (indicators for each value are included in the regression model). Error bars are 95% confidence intervals and use randomization inference to account for the correlation across peers due to the network structure of treatment.

Discussion

A series of letters targeting high quetiapine prescribers strongly encouraged recipients to reduce quetiapine prescribing. However, by multiple measures, we did not detect a significant change in prescribing among physicians working with letter recipients. This raises the question of whether other interventions that tend to deliver smaller effects on targeted practitioners, such as simple “nudge” messages, can spill over to other practitioners through peer networks.

The limitations of this study include that peers were measured imperfectly in administrative data and that associations could have been meaningful but too small to be detected. These results may not be generalizable to other interventions that could be more socially acceptable to share. Given the limited association of these overuse letters with prescribing by peers and the potential for alert fatigue, practitioners hoping to use similar messages to influence overuse should choose wisely as they consider which quality metrics to target.

References

- 1.Donohue JM, Guclu H, Gellad WF, et al. . Influence of peer networks on physician adoption of new drugs. PLoS One. 2018;13(10):e0204826. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0204826 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Agha L, Molitor D. The local influence of pioneer investigators on technology adoption: evidence from new cancer drugs. Rev Econ Stat. 2018;100(1):29-44. doi: 10.1162/REST_a_00670 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.By the American Geriatrics Society 2015 Beers Criteria Update Expert Panel American Geriatrics Society 2015 updated Beers criteria for potentially inappropriate medication use in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2015;63(11):2227-2246. doi: 10.1111/jgs.13702 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sacarny A, Barnett ML, Le J, Tetkoski F, Yokum D, Agrawal S. Effect of peer comparison letters for high-volume primary care prescribers of quetiapine in older and disabled adults: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry. 2018;75(10):1003-1011. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2018.1867 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sacarny A, Olenski AR, Barnett ML Spillovers within and between physicians: evidence from a randomized overprescribing letter in Medicare. https://www.socialscienceregistry.org/trials/3209. Accessed December 28, 2018.