Key Points

Question

Does a home-based exercise program reduce falls among community-dwelling older adults who present to a fall prevention clinic after a fall?

Findings

In this randomized clinical trial that included 344 older adults receiving geriatrician-led care at a fall prevention clinic, a home-based strength and balance retraining exercise program significantly reduced subsequent falls compared with usual care only (1.4 vs 2.1 falls per person-year).

Meaning

These findings support the use of this home-based exercise program for secondary fall prevention but require replication in other clinical settings.

Abstract

Importance

Whether exercise reduces subsequent falls in high-risk older adults who have already experienced a fall is unknown.

Objective

To assess the effect of a home-based exercise program as a fall prevention strategy in older adults who were referred to a fall prevention clinic after an index fall.

Design, Setting, and Participants

A 12-month, single-blind, randomized clinical trial conducted from April 22, 2009, to June 5, 2018, among adults aged at least 70 years who had a fall within the past 12 months and were recruited from a fall prevention clinic.

Interventions

Participants were randomized to receive usual care plus a home-based strength and balance retraining exercise program delivered by a physical therapist (intervention group; n = 173) or usual care, consisting of fall prevention care provided by a geriatrician (usual care group; n = 172). Both were provided for 12 months.

Main Outcomes and Measures

The primary outcome was self-reported number of falls over 12 months. Adverse event data were collected in the exercise group only and consisted of falls, injuries, or muscle soreness related to the exercise intervention.

Results

Among 345 randomized patients (mean age, 81.6 [SD, 6.1] years; 67% women), 296 (86%) completed the trial. During a mean follow-up of 338 (SD, 81) days, a total of 236 falls occurred among 172 participants in the exercise group vs 366 falls among 172 participants in the usual care group. Estimated incidence rates of falls per person-year were 1.4 (95% CI, 0.1-2.0) vs 2.1 (95% CI, 0.1-3.2), respectively. The absolute difference in fall incidence was 0.74 (95% CI, 0.04-1.78; P = .006) falls per person-year and the incident rate ratio was 0.64 (95% CI, 0.46-0.90; P = .009). No adverse events related to the intervention were reported.

Conclusions and Relevance

Among older adults receiving care at a fall prevention clinic after a fall, a home-based strength and balance retraining exercise program significantly reduced the rate of subsequent falls compared with usual care provided by a geriatrician. These findings support the use of this home-based exercise program for secondary fall prevention but require replication in other clinical settings.

Trial Registration

ClinicalTrials.gov Identifiers: NCT01029171; NCT00323596

This randomized trial compares the effect of geriatrician-delivered fall prevention care with vs without a physical therapist–delivered home-based strength and balance retraining exercise program on number of subsequent falls in older adults who were referred to a fall prevention clinic after a previous fall.

Introduction

Falls in older adults are the third leading cause of chronic disability. Strength and balance exercises can reduce falls.1 A home-based strength and balance training program reduced falls in community-dwelling people who were at least 75 years old.2,3,4

The most effective method to prevent additional falls among older people who have previously fallen is not established. Three prior trials showed no effect of exercise on fall prevention in older people with a history of falls, despite having adequate statistical power.5,6,7 These trials informed the 2018 US Preventive Services Task Force determination that exercise was associated with a “nonsignificant reduction in falls.”8 Whether the Otago Exercise Program, which consists of balance, strength, and walking exercises, reduces falling in community-dwelling older adults who fell in the last year is not established.

This 12-month, single-blind, randomized clinical trial was designed to assess whether a home-based exercise program would prevent future falls in older men and women who sought outpatient medical care after a prior fall.

Methods

Study Design and Setting

This study was a parallel-group, single-blind, randomized clinical trial conducted in the Greater Vancouver area of British Columbia, Canada. The study protocol has been published9 and is available in Supplement 1. Ethical approval was obtained from the University of British Columbia Clinical Research Ethics Board and the Vancouver Coastal Health Research Institute. All participants provided written informed consent.

Recruitment

Participants were recruited from the Falls Prevention Clinic (http://www.fallsclinic.ca), a university hospital clinic. Recruitment and enrollment occurred over 8 years, from April 22, 2009, to May 12, 2017, because of limited funding and low rates of referral to the clinic until 2011.

There were 2 trial registrations for this trial. The first was created for a proof-of-concept study.10 On completion of that study, the original registration was modified for the current trial. The second trial registration was created when the research team received advice to close the first trial registration, consistent with recommendations of 1 registration per trial. The second registration occurred after 19 participants were randomized.

Older adults who experienced a fall were referred to the Falls Prevention Clinic by family physicians. Patients received a fall risk assessment, a comprehensive medical assessment, and treatment by a geriatrician. Care was based on the American Geriatrics Society Fall Prevention Guidelines11 and is hereafter referred to as usual care. Care included medication adjustment, lifestyle recommendations (eg, physical activity, smoking cessation, reducing alcohol intake), and referral to other health care professionals (eg, occupational therapy, ophthalmologists).12

Inclusion Criteria

Eligible participants were community-dwelling adults aged at least 70 years receiving care at the Falls Prevention Clinic after a nonsyncopal fall in the previous 12 months. Additional inclusion criteria were English speaking, high risk of future falls (based on a Physiological Profile Assessment [Prince of Wales Medical Research Institute, Sydney, Australia]13 score of at least 1.0 SD above age-normative value, a Timed Up and Go Test14 result >15 seconds, or history of ≥2 nonsyncopal falls in the previous 12 months), Mini-Mental State Examination score higher than 24,15 and life expectancy greater than 12 months.

Exclusion Criteria

Exclusion criteria were neurodegenerative disease, dementia, history of stroke or carotid sinus sensitivity (ie, syncopal falls), and inability to walk 3 m.

Randomization and Blinding

To ensure concealment of the treatment allocation, randomization sequences were generated and held by a central internet randomization service (https://www.randomize.net). Permuted blocks of varying size (eg, 2, 4, 6) were used. Participants were randomly assigned in a 1:1 ratio to receive either the home-based Otago Exercise Program plus usual care or usual care only. Randomization was stratified by sex because fall rates differ between men and women.16 Randomization was planned to be stratified by participants’ geriatrician. However, this randomization protocol was not followed because 1 geriatrician (L.D.) cared for 70% of the study participants (the remaining 30% were seen by 5 geriatricians).

Interventions

The Otago Exercise Program is an individualized home-based balance and strength retraining program delivered by a physical therapist.3 It includes 5 strengthening exercises: knee extensor (4 levels of difficulty), knee flexor (4 levels), hip abductor (4 levels), ankle plantar flexors (2 levels), and ankle dorsiflexors (2 levels). It also includes 11 balance retraining exercises: knee bends (4 levels of difficulty), backward walking (2 levels), walking and turning around (2 levels), sideways walking (2 levels), tandem stands (2 levels), tandem walking (2 levels), 1-leg stand (3 levels), heel walking (2 levels), toe walking (2 levels), heel-toe walking backward (1 level), and sit to stand (4 levels). The physical therapy aim was to progress participants to a greater level of difficulty over time.

A licensed physical therapist visited participants at home and prescribed exercises from a manual. At the first visit, participants received the intervention manual, including photographs and descriptions of each exercise and cuff weights for strength training exercises. The physical therapist returned biweekly for 3 additional visits to adjust the intervention. Visits in the first 2 months took 1 hour. The physical therapist’s fifth (final) visit occurred 6 months after baseline. Participants were asked to perform exercises 3 times per week and walk 30 minutes at least twice per week.

Participants were evaluated and treated by geriatricians at baseline and 6 and 12 months after randomization. To ensure geriatricians remained blinded, participants were reminded not to disclose their group assignment during follow-up visits.

Measures

Outcomes were assessed by blinded assessors at baseline and at 6- and 12-month follow-up. Exercise program adherence and physical activity level (Physical Activity Scale for the Elderly; score range, 0-793; higher scores indicate better performance)17 were assessed monthly by an unblinded research assistant.

The Functional Comorbidity Index18 measured the number of comorbid conditions (score range, 0-18; 0 indicates no comorbid illness). The 15-item Geriatric Depression Scale19,20 assessed mood (range, 0-15; scores ≤5 indicate normal mood). The Lawton and Brody21 Instrumental Activities of Daily Living Scale assessed independent living skills (range, 0-8; higher scores indicate better skills). Global cognitive function was measured with the Mini-Mental State Examination (range, 0-30; higher scores indicate better performance)15 and the Montreal Cognitive Assessment22 (range, 0-30 points for each measure; higher scores indicate better performance). Mini-Mental State Examination scores of at least 24 and Montreal Cognitive Assessment scores of at least 26 indicate normal cognition.

Outcomes

The primary outcome was the number of self-reported falls over 12 months (ie, rate of falls). Falls were documented by participants on calendars that were returned monthly. Falls were defined as “unintentionally coming to the ground or some lower level and other than as a consequence of sustaining a violent blow, loss of consciousness, sudden onset of paralysis as in stroke or an epileptic seizure.”23

An unblinded research assistant contacted participants if they did not return their monthly calendar or if falls were recorded on their monthly calendar. For reported falls, an unblinded research assistant characterized the fall using a questionnaire. Falls were adjudicated against the study definition by a blinded investigator (J.C.D.).

Secondary outcomes were changes in fall risk, general balance, and mobility. Fall risk, expressed as z score, was assessed by the Physiological Profile Assessment13 (observed score range, −2 to 4; 0 to 1 indicates mild risk, >1 to 2 indicates moderate risk, >2 to 3 indicates high risk, and >3 indicates marked risk). A minimum clinically important difference (MCID) for the Physiological Profile Assessment is not established. Additional secondary measures were the Short Physical Performance Battery24 (range, 0-12; higher scores indicate better performance; MCID = 1.0; scores ≤9 predict subsequent disability)24 and the Timed Up and Go Test14 (in seconds; lower scores indicate better performance; MCID = 3.4 after surgery for lumbar degenerative disk disease25; MCID = 0.8-1.4 for older adults with hip osteoarthritis26; scores ≥13.5 seconds indicate high fall risk).14

Executive functions and processing speed were measured with the Trail Making Tests Parts A and B (in seconds; lower scores indicate better performance),15 verbal digit span forward and backward test (range, 0-14 for each test; higher scores indicate better performance),15 Stroop Color-Word Test (in seconds; lower scores indicate better performance),15 and Digit Symbol Substitution Test (range, 0-84; higher scores indicate better performance).15 No MCID values have been reported for these cognitive measures.

Fall-related fractures were recorded at the interview performed after each fall.

Adverse Events

During each home visit, therapists recorded any falls or injuries that occurred because of the intervention. Participants receiving the intervention were asked during monthly telephone calls if they experienced falls, injuries, new muscle soreness, or pain as a result of the intervention exercises. Participants in the usual care group were not queried about adverse events.

Statistical Analysis

The number of falls over 12 months was modeled using an overdispersed Poisson model (ie, a negative binomial regression model).27 Assuming a mean fall rate in the usual care group of 1.0 per year, a mean follow-up of 0.9 years, and an overdispersion parameter (φ) of 1.6, 163 participants per group were required for 80% power to detect a 35% relative reduction in fall rate; ie, 1.0 vs 0.65 falls per year.28 The estimate of the overdispersion parameter (φ = 1.6) is derived from data from Shumway-Cook et al.29 Mean length of follow-up was estimated from a previous proof-of-concept study.10 To accommodate a complete loss to follow-up rate of 5% (ie, no fall diaries returned), a total sample of 344 participants (ie, 172 per group) was required.

Adherence was assessed via monthly calendars. Adherence to the balance and strength components of the exercise program were measured separately from walking. Adherence was calculated as (sessions completed/total sessions expected) × 100. Total sessions for balance and strength retraining were calculated as 3 sessions per week × 52 weeks. Total sessions for walking were calculated as 2 sessions per week × 52 weeks. For 13 participants who provided no data, adherence of 0% was assumed.

Primary analyses were conducted using the R statistical package, version 3.5.1 (http://www.r-project.org). All analyses followed the intention-to-treat principle: all participants were analyzed according to their randomized group assignment, regardless of whether they discontinued the intervention.

The primary analysis evaluated between-group differences in the number of falls over 12 months using a negative binomial regression model, an extension to the Poisson model that accommodates overdispersion.30 Treatment group and sex (the stratification factor) were included as covariates. Robust heteroskedasticity-consistent standard errors were calculated using the R “sandwich” package (version 2.5). Incident rate ratios (IRRs) and 95% confidence intervals were calculated by exponentiating the coefficients estimated in the model. Statistical significance was defined as a 2-sided P < .05. Estimated incidence rates in each group and absolute differences in rates were estimated using bootstrapped G computation (5000 resamples with replacement).31

Missing fall data were handled in 2 ways. First, only observed data were used, with differential exposure accounted for by using exposure time (calculated in days) as an offset in the negative binomial regression analysis. For 11 participants without any fall data after randomization because of dropout, it was assumed that 0 falls occurred during their exposure periods. Second, missing fall data were imputed with multiple imputation, using chained equations with the R “MICE” package (version 3.3.0).32 Estimates were pooled across 40 imputed data sets (see eAppendix in Supplement 2).33

Secondary and other analyses did not adjust for multiple outcomes34 and therefore should be considered exploratory. Point and 95% confidence interval estimates for the effect of the intervention (as determined by the group × time effect) on each secondary outcome were determined separately using linear mixed models.35 Missing data were handled via restricted maximum likelihood estimation, which is fully efficient if the missing data are missing at random.36 Secondarily, the linear mixed model was run using data from multiple imputation analyses. Each linear mixed model contained fixed effects of time, group, sex, group × time, and sex × time and random intercept and time effects. The time variable used for fixed and random effects was coded as 0 (baseline), 0.5 (6 months), and 1 (12 months). Profile likelihood-based 95% confidence intervals around the fixed effects were estimated.

Post hoc analyses were conducted to determine the number of falls per person-year, the number of persons with 1 or more falls, and the number of fall-related fractures per person-year. The number of falls per person-year was calculated as the sum of all falls divided by the cumulative exposure time (in years) across participants. The number of persons with 1 or more falls was summed. The number of fall-related fractures per person-year was calculated as the sum of all fall-related fractures across participants divided by the cumulative exposure time (in years) across participants. Between-group differences in rate of fracture were modeled using negative binomial regression.

Post hoc analyses of time to first and second falls were conducted using Cox proportional hazards models with robust standard errors and included treatment group and sex as covariates using the R “survival” package (version 2.43-3). Kaplan-Meier plots of survival probability (ie, not experiencing a fall) over time are presented. The proportional hazards assumption was tested. Results showed χ21 = 1.11 and P = .29 for time to first fall and χ21 = 0.35 and P = .55 for time to second fall; therefore, it was concluded that this assumption was met.

Results

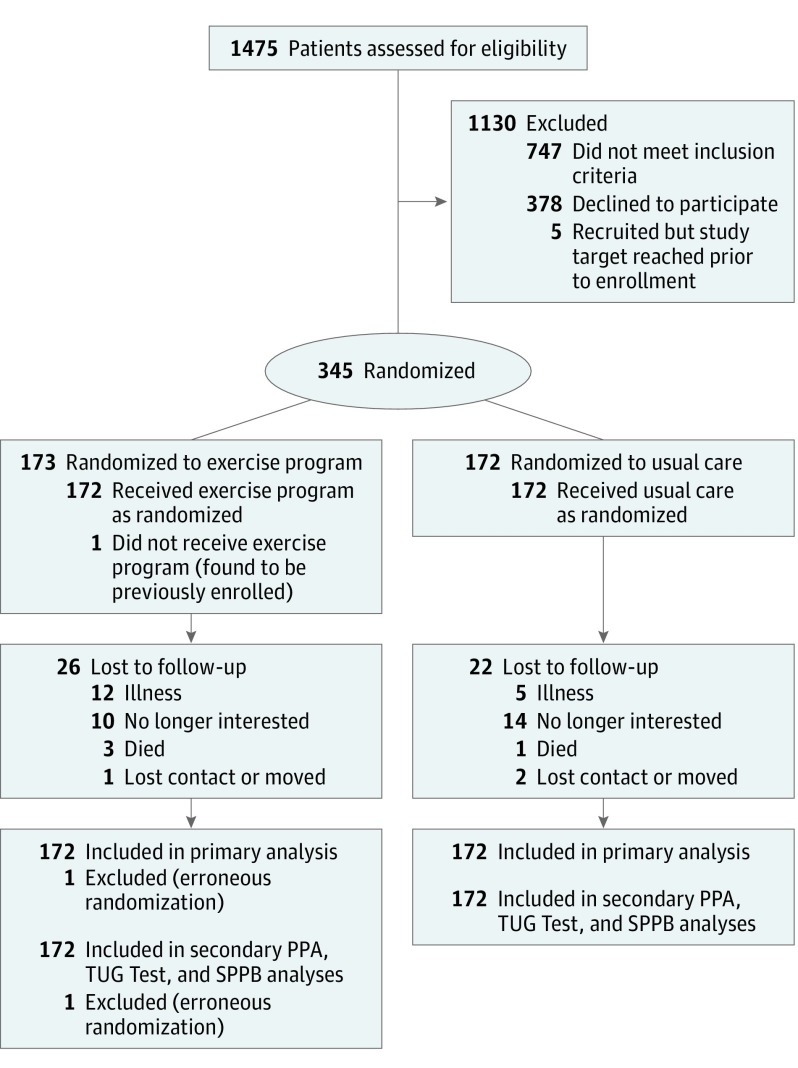

Figure 1 presents participant recruitment, participation, and retention. Participants were a mean age of 81.6 (SD, 6.1) years and 67% were women (Table 1). Mean follow-up time was 334 (SD, 86) days for the exercise group and 343 (SD, 75) days for usual care (see Table 2). Physical Activity Scale for the Elderly scores did not significantly differ between groups throughout the trial (P = .37).

Figure 1. Participant Flow in a Trial of a Home-Based Exercise Program vs Usual Care for Secondary Fall Prevention.

PPA indicates Physiological Profile Assessment; TUG, Timed Up and Go; SPPB, Short Physical Performance Battery.

Table 1. Sample Characteristics by Treatment Group.

| Characteristics | Exercise Group (n = 172) | Usual Care Group (n = 172) |

|---|---|---|

| Age, mean (SD), y | 81.2 (6.1) | 81.9 (6.0) |

| Sex, No. (%) | ||

| Male | 62 (36) | 53 (31) |

| Female | 110 (64) | 119 (69) |

| Height, mean (SD), cm | 162.3 (10.8) | 162.2 (9.5) |

| Weight, mean (SD), kg | 72.1 (17.9) | 71.4 (15.0) |

| Education, No. (%) | ||

| Less than grade 9 | 7 (4) | 2 (1) |

| Grade 9-13 without certificate or diploma | 14 (8) | 20 (12) |

| High school certificate or diploma | 28 (16) | 32 (19) |

| Some university without certificate | 16 (9) | 14 (8) |

| Trades or professional certificate/diploma | 27 (16) | 21 (12) |

| University certificate/diploma | 9 (5) | 9 (5) |

| University degree | 71 (41) | 74 (43) |

| Living status, No. (%) | ||

| Assisted living | 16 (9) | 11 (6) |

| Home alone | 68 (40) | 81 (47) |

| Home with others | 88 (51) | 80 (47) |

| Falls in 12 mo prior to study, No. (%) | ||

| 1 | 43 (25) | 60 (35) |

| 2 | 56 (33) | 39 (23) |

| 3 | 30 (17) | 24 (14) |

| ≥4 | 43 (25) | 49 (28) |

| Mean (SD) No. of falls | 2.8 (2.3) | 3.0 (4.3) |

| Injurious falls in 12 mo prior to study, No. (%)a | ||

| None | 51 (30) | 47 (27) |

| Soft tissue injury | 90 (52) | 93 (54) |

| Fracture | 31 (18) | 32 (19) |

| Use of walker, brace, or cane, No. (%) | 46 (27) | 37 (22) |

| Geriatric Depression Scale score, mean (SD)b | 2.8 (2.4) | 3.0 (2.6) |

| Body mass index, mean (SD)c | 26.9 (5.4) | 27.1 (4.9) |

| Functional Comorbidity Index, mean (SD)d | 4.1 (2.2) | 4.0 (2.0) |

| Instrumental Activities of Daily Living score, mean (SD)e | 7.2 (1.2) | 7.4 (1.1) |

| Gait speed, mean (SD), m/s | 0.9 (0.2) | 0.8 (0.2) |

| Mini-Mental State Examination score, mean (SD)f | 27.7 (1.7) | 27.9 (1.6) |

| Montreal Cognitive Assessment score, mean (SD)g | 22.9 (3.4) | 23.4 (3.3) |

One per participant, whereby if more than 1 injurious fall was reported, the worst injurious fall outcome was counted.

Geriatric Depression Scale scores range from 0 (best) to 15 (worst); scores of 0 to 5 indicate no depression.

Calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared.

The Functional Comorbidity Index ranges from 0 (best; no comorbid illness) to 18 (worst; highest number of comorbid illnesses). Higher scores are associated with lower physical function.

Lawton Instrumental Activities of Daily Living scores range from 0 (worst; dependent) to 8 (best; independent). A score of 7 indicates a person who is largely independent but cannot manage finances or perform housekeeping tasks.

Mini-Mental State Examination scores range from 0 (worst) to 30 (best); scores of 24 to 30 are considered unimpaired.

Montreal Cognitive Assessment scores range from 0 (worst) to 30 (best); scores of 26 to 30 are considered unimpaired.

Table 2. Primary and Post Hoc Outcomes by Treatment Group.

| Outcomes | Exercise Group (n = 172) | Usual Care Group (n = 172) |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Outcomea | ||

| Total exposure, d | ||

| Mean (SD) | 334 (86) | 343 (75) |

| Median (interquartile range) | 365 (365-365) | 365 (365-365) |

| No. of falls observed | 236 | 366 |

| Post Hoc Outcomes | ||

| Falls per person-year, mean (SD) | 1.4 (1.9) | 2.1 (3.8) |

| No. of falls, No. (%) of participants | ||

| 0 | 67 (39) | 68 (40) |

| 1 | 45 (26) | 37 (22) |

| 2 | 35 (20) | 28 (16) |

| 3 | 11 (6) | 14 (8) |

| ≥4 | 14 (8) | 25 (15) |

| No. (%) of participants with ≥1 fall | 105 (61) | 104 (60) |

| No. of fall-related fractures observed, No. | 15 | 12 |

| Fractures per person-year, mean (SD) | 0.09 (0.32) | 0.08 (0.32) |

The absolute difference in fall incidence was 0.74 (95% CI, 0.04-1.78; P=.006) falls per person-year and the incident rate ratio was 0.64 (95% CI, 0.46-0.90; P=.009).

Mean adherence to the balance and strength retraining component was 63%. Mean adherence to the walking component was 127% (due to exceeding the twice-weekly threshold). No adherence data were obtained from 13 participants who dropped out within 2 months after randomization.

Primary Outcome

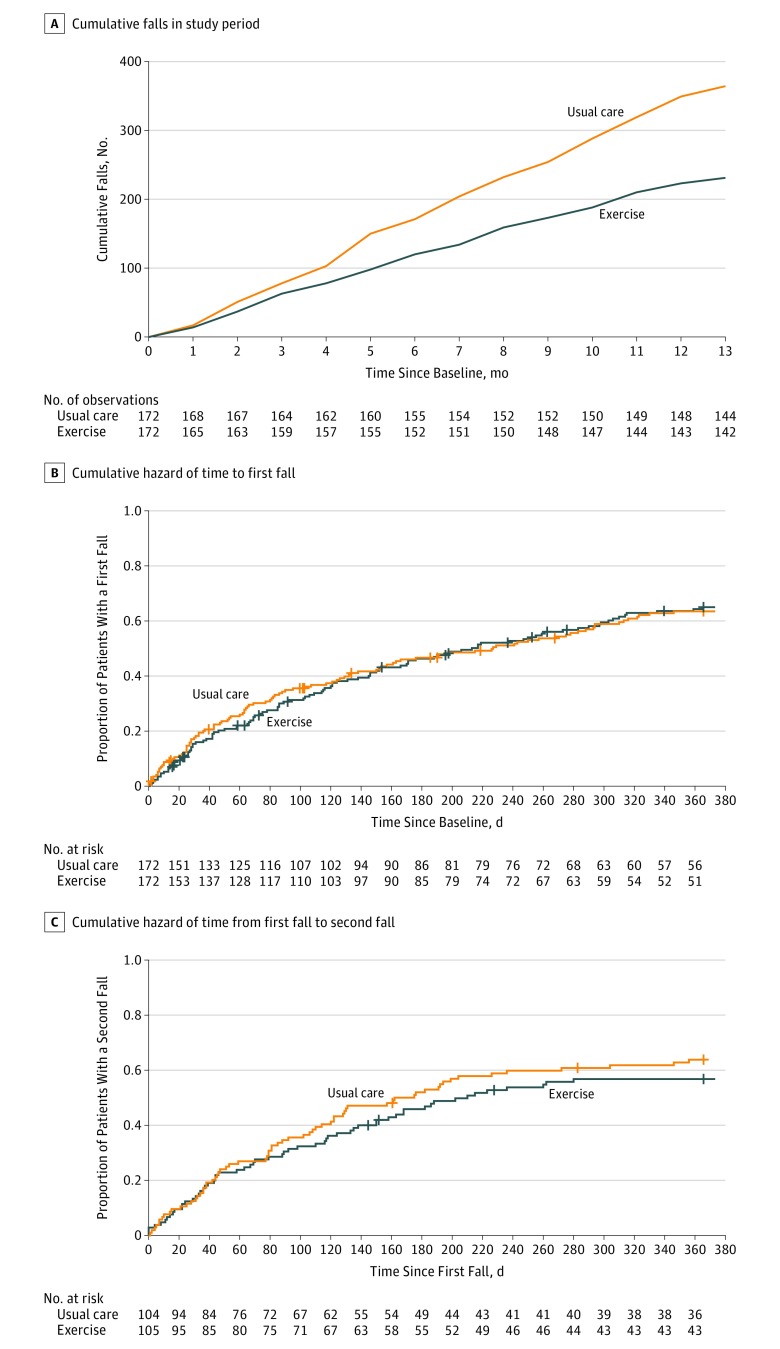

During a mean follow-up of 338 (SD, 81) days, 236 falls occurred among 172 participants in the exercise group vs 366 falls among 172 participants in usual care (Figure 2A). Fall rates were lower in the exercise group compared with usual care (IRR, 0.64; 95% CI, 0.46-0.90; P = .009). The estimated fall rate incidence was 1.4 (95% CI, 0.1-2.0) per person-year in the exercise group and 2.1 (95% CI, 0.1-3.2) per person-year in the usual care group (absolute incidence rate difference between groups of 0.74 [95% CI, 0.04-1.78; P = .006] falls per person-year). Analysis of multiply imputed data sets indicated a similar magnitude of reduction in falls rate for participants randomized to exercise (IRR, 0.66; 95% CI, 0.48-0.91; P = .01).

Figure 2. Accumulation of Falls and Cumulative Hazards of First and Second Falls by Treatment Group.

A, Numbers below x-axis indicate participants who provided fall data. Overall, 10.5% of fall calendars (471/4472) were not returned. A total of 11 participants (3% of total randomized sample; 7 randomized to exercise and 4 randomized to usual care) did not provide any data related to falls after randomization. These participants dropped out within the first 2 months of the study. The estimated incidence rate of falls per person-year was 1.4 (95% CI, 0.1-2.0) in the exercise group and 2.1 (95% CI, 0.1-3.2) in the usual care group. The median total exposure was 365 (interquartile range [IQR], 365-365) days for both exercise and usual care. B, The median observation period from baseline to first fall was 173.5 (IQR, 58-365) days for the exercise group and 180.5 (IQR, 47.75-365) days for the usual care group. C, The median observation period after the first fall was 188 (IQR, 67-365) days for the exercise group and 161.5 (IQR, 52.5-365) days for the usual care group. In panels B and C, vertical lines on the curves indicate censored events.

Overall, 10.5% of fall calendars (471/4472) were not returned. Eleven participants (3% of total randomized sample; 7 randomized to exercise and 4 randomized to usual care) did not provide any data related to falls after randomization (Figure 2A).

Secondary Outcomes

There were no statistically significant differences in secondary outcomes between the 2 groups (Table 3 and eTable 1 in Supplement 2).

Table 3. Within- and Between-Group Differences in Secondary Outcomes From Baseline to 12 Months.

| Outcomes | Exercise Group | Usual Care Group | Exercise Minus Usual Care | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | 12 mo | Estimated Difference (95% CI)a | Baseline | 12 mo | Estimated Difference (95% CI)a | Estimated Difference (95% CI)a | P Value | |

| Physiological Profile Assessment z score, mean (SD)b | 1.92 (1.06) | 2.03 (1.05) | 0.14 (−0.05 to 0.32) | 1.93 (1.12) | 1.93 (1.13) | 0.07 (−0.20 to 0.29) | 0.07 (−0.19 to 0.33) | .59 |

| No. of participants | 172 | 129 | 172 | 133 | ||||

| Timed Up and Go Test score, mean (SD), sc | 16.3 (7.0) | 16.1 (6.0) | 0.2 (−1.1 to 1.4) | 16.9 (6.4) | 16.6 (8.5) | 0.03 (−1.3 to 1.3) | 0.1 (−1.6 to 1.9) | .89 |

| No. of participants | 172 | 127 | 171 | 131 | ||||

| Short Physical Performance Battery score, mean (SD)d | 7.9 (2.2) | 7.9 (2.2) | −0.2 (−0.5 to 0.2) | 7.8 (2.3) | 7.8 (2.4) | −0.2 (−0.5 to 0.1) | 0.05 (−0.4 to 0.5) | .84 |

| No. of participants | 172 | 128 | 172 | 132 | ||||

Estimated differences were calculated using linear mixed models, which provide estimates for missing data.

Physiological Profile Assessment z scores of 0 to 1 indicate mild risk, 1 to 2 indicate moderate risk, 2 to 3 indicate high risk, and 3 or above indicate marked risk. A negative difference in scores between the 2 groups indicates that improvements were greater in the exercise group.

The Timed Up and Go Test is measured in seconds; longer completion times are associated with impaired mobility and fall risk; completion times of 13.5 seconds or longer indicate high fall risk. A negative difference in scores between the 2 groups indicates that improvements were greater in the exercise group.

Short Physical Performance Battery scores range from 0 (worst) to 12 (best); scores of 9 or lower predict subsequent disability. A positive difference in scores between the 2 groups indicates that improvements were greater in the exercise group.

Post Hoc Analyses

Two hundred nine participants fell at least once (105 in the exercise group and 104 in the usual care group). Fifteen fall-related fractures occurred in the exercise group vs 12 in the usual care group (IRR, 1.93; 95% CI, 0.76-4.97; P = .17) (Table 2).

Digit Symbol Substitution Test scores increased in the exercise group by a mean of 1.1 points (95% CI, 0.02-2.1 points; P = .047) relative to the usual care group in nonimputed data analyses (eTable 2 in Supplement 2). Analysis of multiply imputed data showed no effect of the intervention on the Digit Symbol Substitution Test (P = .34) (eTable 2). The exercise intervention had no effect on the 3 other measures of executive function.

There was no significant difference between the groups in time to first fall (hazard ratio, 0.95; 95% CI, 0.72-1.25; P = .72) (Figure 2B) or time to second fall (hazard ratio, 0.82; 95% CI, 0.58-1.17; P = .27) (Figure 2C).

Adverse Events

No adverse events related to the intervention were reported. During a home visit, a participant required assistance to get up after bending down but did not have a fall.

Discussion

A home-based exercise program reduced subsequent falls in community-dwelling older adults who sought medical attention after a fall. The rate of reduction was similar to results of a meta-analysis of 4 randomized trials of these home-based exercises in community-dwelling older adults selected on age alone (ie, primary fall prevention).28 This trial provides new evidence by demonstrating benefits of a home-based exercise program in secondary fall prevention.

There were no significant differences between the 2 study groups in time to first fall, time to second fall, or number of participants who fell 1 or more times. The home-based exercise program may have been effective because it reduced the number of falls among individuals who fell repeatedly. In addition, the difference in fall rates between the 2 groups increased over time (Figure 2A).

There were no significant differences in secondary outcomes, consistent with a previous proof-of-concept randomized trial in the same high-risk population.10 The aforementioned meta-analysis of 4 trials reported no significant group differences in balance or lower extremity strength.28 A randomized clinical trial of tai chi that reduced falls among older adults also found no group differences in balance or gait speed.37 Thus, it is possible to observe a significant reduction in falls without significant improvements in physical performance.

Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, results of this study may not be generalizable to those who did not meet eligibility criteria. Second, this was a single-center study and may not represent other nonurban centers. Third, a single geriatrician provided care for 70% of the patients and may not be representative of all geriatricians. Fourth, specialized fall prevention clinics are not common in most communities. Fifth, while fall adjudication was completed by a blinded investigator, monthly collection of fall data was done by an unblinded research assistant. Sixth, recording of adverse events was limited to falls, muscle soreness, and injuries in the intervention group. Seventh, there were multiple secondary outcome measures, and no adjustment for multiple comparisons was made.9

Conclusions

Among older adults receiving care at a fall prevention clinic after a fall, a home-based strength and balance retraining exercise program significantly reduced the rate of subsequent falls compared with usual care provided by a geriatrician. These findings support the use of this home-based exercise program for secondary fall prevention but require replication in other clinical settings.

Trial Protocol

eAppendix. Supplemental Methods for Multiple Imputation

eTable 1. Imputed Data Results for Secondary and Exploratory Outcomes

eTable 2. Within- and Between-Condition Differences in Exploratory Outcomes of Cognitive Function From Baseline to Month 12

Data Sharing Statement

References

- 1.Gillespie LD, Robertson MC, Gillespie WJ, et al. Interventions for preventing falls in older people living in the community. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;(2):CD007146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Campbell AJ, Robertson MC, Gardner MM, Norton RN, Buchner DM. Falls prevention over 2 years: a randomized controlled trial in women 80 years and older. Age Ageing. 1999;28(6):513-518. doi: 10.1093/ageing/28.6.513 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Campbell AJ, Robertson MC, Gardner MM, Norton RN, Tilyard MW, Buchner DM. Randomised controlled trial of a general practice programme of home based exercise to prevent falls in elderly women. BMJ. 1997;315(7115):1065-1069. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7115.1065 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Robertson MC, Devlin N, Gardner MM, Campbell AJ. Effectiveness and economic evaluation of a nurse delivered home exercise programme to prevent falls, 1: randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2001;322(7288):697-701. doi: 10.1136/bmj.322.7288.697 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Luukinen H, Lehtola S, Jokelainen J, Väänänen-Sainio R, Lotvonen S, Koistinen P. Pragmatic exercise-oriented prevention of falls among the elderly: a population-based, randomized, controlled trial. Prev Med. 2007;44(3):265-271. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2006.09.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Logghe IH, Zeeuwe PE, Verhagen AP, et al. Lack of effect of tai chi chuan in preventing falls in elderly people living at home: a randomized clinical trial. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2009;57(1):70-75. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2008.02064.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Uusi-Rasi K, Patil R, Karinkanta S, et al. Exercise and vitamin D in fall prevention among older women: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(5):703-711. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.0225 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Guirguis-Blake JM, Michael YL, Perdue LA, Coppola EL, Beil TL. Interventions to prevent falls in older adults: updated evidence report and systematic review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. JAMA. 2018;319(16):1705-1716. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.21962 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liu-Ambrose T, Davis JC, Hsu CL, et al. Action Seniors!: secondary falls prevention in community-dwelling senior fallers: study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials. 2015;16:144. doi: 10.1186/s13063-015-0648-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liu-Ambrose T, Donaldson MG, Ahamed Y, et al. Otago home-based strength and balance retraining improves executive functioning in older fallers: a randomized controlled trial. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008;56(10):1821-1830. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2008.01931.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.American Geriatrics Society, British Geriatrics Society, and American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons Panel on Falls Prevention Guideline for the prevention of falls in older persons. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2001;49(5):664-672. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2001.49115.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Davis JC, Dian L, Parmar N, et al. Geriatrician-led evidence-based falls prevention clinic: a prospective 12-month feasibility and acceptability cohort study among older adults. BMJ Open. 2018;8(12):e020576. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-020576 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.A physiological profile approach for falls prevention In: Lord S, Sherrington C, Menz H. Falls in Older People: Risk Factors and Strategies for Prevention. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press; 2001:221-238. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shumway-Cook A, Brauer S, Woollacott M. Predicting the probability for falls in community-dwelling older adults using the Timed Up & Go Test. Phys Ther. 2000;80(9):896-903. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Spreen O, Strauss E. A Compendium of Neurological Tests. 2nd ed New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Duckham RL, Procter-Gray E, Hannan MT, Leveille SG, Lipsitz LA, Li W. Sex differences in circumstances and consequences of outdoor and indoor falls in older adults in the MOBILIZE Boston cohort study. BMC Geriatr. 2013;13:133. doi: 10.1186/1471-2318-13-133 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Washburn RA, Smith KW, Jette AM, Janney CA. The Physical Activity Scale for the Elderly (PASE): development and evaluation. J Clin Epidemiol. 1993;46(2):153-162. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(93)90053-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Groll DL, To T, Bombardier C, Wright JG. The development of a comorbidity index with physical function as the outcome. J Clin Epidemiol. 2005;58(6):595-602. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2004.10.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yesavage JA, Brink TL, Rose TL, et al. Development and validation of a geriatric depression screening scale: a preliminary report. J Psychiatr Res. 1982-1983;17(1):37-49. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(82)90033-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.van Marwijk HW, Wallace P, de Bock GH, Hermans J, Kaptein AA, Mulder JD. Evaluation of the feasibility, reliability and diagnostic value of shortened versions of the geriatric depression scale. Br J Gen Pract. 1995;45(393):195-199. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lawton MP, Brody EM. Assessment of older people: self-maintaining and instrumental activities of daily living. Gerontologist. 1969;9(3):179-186. doi: 10.1093/geront/9.3_Part_1.179 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nasreddine ZS, Phillips NA, Bédirian V, et al. The Montreal Cognitive Assessment, MoCA: a brief screening tool for mild cognitive impairment. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53(4):695-699. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53221.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kellogg International Work Group The prevention of falls in later life: a report of the Kellogg International Work Group on the prevention of falls by the elderly. Dan Med Bull. 1987;34(suppl 4):1-24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Guralnik JM, Ferrucci L, Simonsick EM, Salive ME, Wallace RB. Lower-extremity function in persons over the age of 70 years as a predictor of subsequent disability. N Engl J Med. 1995;332(9):556-561. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199503023320902 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gautschi OP, Stienen MN, Corniola MV, et al. Assessment of the minimum clinically important difference in the Timed Up and Go Test after surgery for lumbar degenerative disc disease. Neurosurgery. 2017;80(3):380-385. doi: 10.1227/NEU.0000000000001320 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wright AA, Cook CE, Baxter GD, Dockerty JD, Abbott JH. A comparison of 3 methodological approaches to defining major clinically important improvement of 4 performance measures in patients with hip osteoarthritis. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2011;41(5):319-327. doi: 10.2519/jospt.2011.3515 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Signorini D. Sample size for Poisson regression. Biometrika. 1991;78:446-450. doi: 10.1093/biomet/78.2.446 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Robertson MC, Campbell AJ, Gardner MM, Devlin N. Preventing injuries in older people by preventing falls: a meta-analysis of individual-level data. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2002;50(5):905-911. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2002.50218.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shumway-Cook A, Silver IF, LeMier M, York S, Cummings P, Koepsell TD. Effectiveness of a community-based multifactorial intervention on falls and fall risk factors in community-living older adults: a randomized, controlled trial. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2007;62(12):1420-1427. doi: 10.1093/gerona/62.12.1420 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Clayton D. Some approaches to the analysis of recurrent event data. Stat Methods Med Res. 1994;3(3):244-262. doi: 10.1177/096228029400300304 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Austin PC, Urbach DR. Using G-computation to estimate the effect of regionalization of surgical services on the absolute reduction in the occurrence of adverse patient outcomes. Med Care. 2013;51(9):797-805. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e31829a4fb4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.van Buuren S, Groothuis-Oudshoorn K. MICE: multivariate imputation by chained equations in R. J Stat Softw. 2011;45(3):1-67. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Graham JW, Olchowski AE, Gilreath TD. How many imputations are really needed? some practical clarifications of multiple imputation theory. Prev Sci. 2007;8(3):206-213. doi: 10.1007/s11121-007-0070-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rothman KJ. No adjustments are needed for multiple comparisons. Epidemiology. 1990;1(1):43-46. doi: 10.1097/00001648-199001000-00010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fitzmaurice GM, Laird NM, Ware JH. Applied Longitudinal Data Analysis. New York, NY: Wiley; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cnaan A, Laird NM, Slasor P. Using the general linear mixed model to analyse unbalanced repeated measures and longitudinal data. Stat Med. 1997;16(20):2349-2380. doi: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hwang H-F, Chen S-J, Lee-Hsieh J, Chien D-K, Chen C-Y, Lin M-R. Effects of home-based tai chi and lower extremity training and self-practice on falls and functional outcomes in older fallers from the emergency department—a randomized controlled trial. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2016;64(3):518-525. doi: 10.1111/jgs.13952 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Trial Protocol

eAppendix. Supplemental Methods for Multiple Imputation

eTable 1. Imputed Data Results for Secondary and Exploratory Outcomes

eTable 2. Within- and Between-Condition Differences in Exploratory Outcomes of Cognitive Function From Baseline to Month 12

Data Sharing Statement