Key Points

Question

In patients with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction, what is the effect of neladenoson bialanate, a partial adenosine A1 receptor agonist, on exercise capacity?

Findings

In this phase 2b randomized clinical trial that included 305 patients randomized to receive neladenoson (5 mg, 10 mg, 20 mg, 30 mg, or 40 mg) or placebo, there was no significant dose-response relationship detected for neladenoson with regard to the change in the 6-minute walk test distance from baseline to 20 weeks.

Meaning

In light of these findings, novel approaches will be needed if further development of neladenoson for the treatment of patients with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction is pursued.

Abstract

Importance

Heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF) lacks effective treatments. Based on preclinical studies, neladenoson bialanate, a first-in-class partial adenosine A1 receptor agonist, has the potential to improve several heart failure–related cardiac and noncardiac abnormalities but has not been evaluated to treat HFpEF.

Objectives

To determine whether neladenoson improves exercise capacity, physical activity, cardiac biomarkers, and quality of life in patients with HFpEF and to find the optimal dose.

Design, Setting, and Participants

Phase 2b randomized clinical trial conducted at 76 centers in the United States, Europe, and Japan. Patients (N = 305) with New York Heart Association class II or III HFpEF with elevated natriuretic peptide levels were enrolled between May 10, 2017, and December 7, 2017 (date of final follow-up: June 20, 2018).

Interventions

Participants were randomized (1:2:2:2:2:3) to neladenoson (n = 27 [5 mg], n = 50 [10 mg], n = 51 [20 mg], n = 50 [30 mg], and n = 51 [40 mg]) or matching placebo (n = 76) for 20 weeks of treatment.

Main Outcomes and Measures

The primary end point was change in 6-minute walk test distance from baseline to 20 weeks (minimal clinically important difference, 40 m). Key safety measures included bradyarrhythmias and adverse events. To evaluate the effects of varying doses of neladenoson, a multiple comparison procedure with 5 modeling techniques (linear, Emax, 2 variations of sigmoidal Emax, and quadratic) was used to evaluate diverse dose-response profiles.

Results

Among 305 patients who were randomized (mean age, 74 years; 160 [53%] women; mean 6-minute walk test distance, 321.5 m), 261 (86%) completed the trial and were included in the primary analysis. After 20 weeks of treatment, the mean absolute changes from baseline in 6-minute walk test distance were 0.2 m (95% CI, −12.1 to 12.4 m) for the placebo group; 19.4 m (95% CI, −10.8 to 49.7 m) for the 5 mg of neladenoson group; 29.4 m (95% CI, 3.0 to 55.8 m) for 10 mg of neladenoson group; 13.8 m (95% CI, −2.3 to 29.8 m) for 20 mg of neladenoson group; 16.3 m (95% CI, −1.1 to 33.6 m) for 30 mg of neladenoson group; and 13.0 m (95% CI, −5.9 to 31.9 m) for 40 mg of neladenoson group. Because none of the neladenoson groups achieved the clinically relevant 40-m increase in 6-minute walk test distance from baseline, an optimal dose of neladenoson was not identified. There was no significant dose-response relationship for the change in 6-minute walk test distance among the 5 different dose-response models (P = .05 for Emax; P = .18 for quadratic; P = .21 for sigmoidal Emax 1; P = .39 for linear; and P = .52 for sigmoidal Emax 2). Serious adverse events were similar among the neladenoson groups (61/229 [26.6%]) and the placebo group (21/76 [27.6%]).

Conclusions and Relevance

Among patients with HFpEF, there was no significant dose-response relationship detected for neladenoson with regard to the change in exercise capacity from baseline to 20 weeks. In light of these findings, novel approaches will be needed if further development of neladenoson for the treatment of patients with HFpEF is pursued.

Trial Registration

ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT03098979

This dose-ranging phase 2b randomized trial compares the effects of neladenoson, a partial adenosine A1 receptor agonist, vs placebo on exercise capacity in patients with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF).

Introduction

Heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF) is common, is increasing in prevalence, is associated with high morbidity and mortality, and lacks effective therapies.1,2 Although HFpEF involves abnormalities in left ventricular diastolic function, leading to increased left atrial and pulmonary venous pressures, there are multiple additional cardiovascular and noncardiovascular pathophysiological abnormalities that occur.2 There is likely widespread microvascular dysfunction that involves all cardiac chambers3,4,5 and other organs such as the lungs, kidneys, and skeletal muscles, indicating that HFpEF is a systemic disorder.5 In addition, left ventricular systolic function is often abnormal, global left ventricular EF (LVEF) is preserved, and left ventricular longitudinal fiber systolic function (reflecting the health of the subendocardium) is frequently impaired.6 Patients with HFpEF commonly have markedly reduced reserve capacity,7,8,9 whereby cardiac, vascular, and skeletal muscle dysfunction become apparent during exertion.

Given the systemic nature of the HFpEF syndrome, an ideal therapy would target several underlying pathophysiological effects related to multiorgan reserve dysfunction. Neladenoson bialanate is a partial adenosine A1 receptor agonist that has been shown in preclinical models to improve mitochondrial function, enhance sarco/endoplasmic reticulum 2a activity, optimize energy substrate utilization, reverse ventricular remodeling, and provide anti-ischemic cardioprotective effects without the adverse effects of full A1 receptor agonists or A1 receptor antagonists.10,11,12,13,14 Prior pilot studies in patients with heart failure and reduced EF found that neladenoson was well tolerated and not associated with significant bradyarrhythmias or fluid retention.15

The preclinical data suggested a potential role for neladenoson in the treatment of HFpEF, particularly for improving exercise intolerance given the potential beneficial effects of the drug on the heart and skeletal muscles. This trial tested the effect of multiple doses of neladenoson on exercise capacity, physical activity, quality of life, and cardiac biomarkers with the objective of finding the optimal dose to treat patients with HFpEF.

Methods

Study Oversight

The study protocol was approved by the institutional review board or ethics committee at each of the 76 enrolling sites, and all enrolled patients provided written informed consent. A data and safety monitoring committee oversaw the trial and reviewed the trial data for patient safety at regular intervals.

Study Design and Participants

The rationale and design of the Partial AdeNosine A1 Receptor Agonist in Patients With Chronic Heart Failure and Preserved Ejection Fraction (PANACHE) trial have been described.16 The trial protocol appears in Supplement 1. This was a phase 2b, randomized, parallel-group, dose-finding, double-blind, multicenter clinical trial. The primary objectives were to (1) determine the optimal dose of neladenoson; and (2) evaluate the effect of neladenoson on multiple domains in patients with HFpEF, including exercise tolerance, quality of life, physical activity, cardiac structure and function, and biomarkers. Patients were recruited at 76 centers in the United States, Europe, and Japan (eTable 1 in Supplement 2 lists all the participating sites and principal investigators). A graphical display of the trial design appears in eFigure 1 in Supplement 2.

A full list of the inclusion and exclusion criteria appear in eTable 2 in Supplement 2. Key inclusion criteria included age of 45 years or older; New York Heart Association functional class II, III, or IV HFpEF; and LVEF of 45% or greater. In addition, other key criteria during the 6 months prior to treatment run-in were (1) treatment with a diuretic; (2) elevated natriuretic peptide levels; and (3) left atrial enlargement, left ventricular hypertrophy, or elevated left ventricular filling pressure. Elevated natriuretic peptide levels were defined as 1 of the following: B-type natriuretic peptide (BNP) level of 75 pg/mL or greater or N-terminal proBNP (NT-proBNP) level of 300 pg/mL or greater (in patients with sinus rhythm) or BNP level of 200 pg/mL or greater or NT-proBNP level of 900 pg/mL or greater (in patients with atrial fibrillation).

Due to requirements from health authorities such as the US Food and Drug Administration, data on race and ethnicity were collected for all participants. Race and ethnicity determinations were made by the participants based on fixed categories. The determinations were reported to the site principal investigator and were documented in the case report forms.

Randomization and Blinding

Eligible patients who entered the run-in period were randomized if they met all the inclusion criteria (eTable 2 in Supplement 2), completed the run-in period, and had a 6-minute walk test distance of between 100 m and 550 m at visit 2 (measured at the baseline visit after the treatment run-in). Immediately following qualification, eligible patients were enrolled between May 10, 2017, and December 7, 2017, and then randomized in a 1:2:2:2:2:3 manner to 1 of 5 neladenoson dose groups (5 mg, 10 mg, 20 mg, 30 mg, or 40 mg once daily) or matching placebo, respectively (Figure 1). The date of final follow-up was June 20, 2018. Patient randomization was performed via the Interactive Web Response System. Patients and study staff were blinded to treatment assignment. Randomization was performed by applying block randomization with a fixed block size of 12, allocation ratio of 1:2:2:2:2:3, and stratification by presence of atrial fibrillation on the baseline electrocardiogram. Further details on blinding of dose and matching placebo appear in the eMethods in Supplement 2.

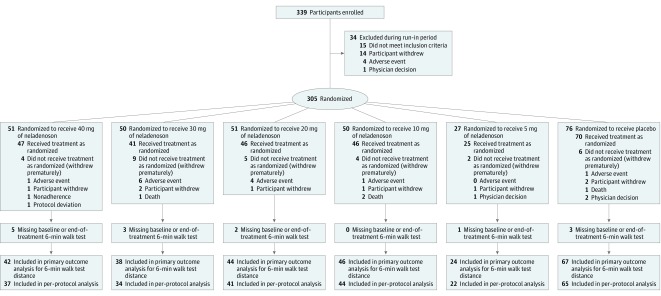

Figure 1. Study Participant Disposition Flowchart.

Information about the number of patients approached was not collected. No study drug was administered during the run-in period, which was only used for familiarization testing for the 6-minute walk test and for collecting data on the continuous electrocardiographic monitoring patch. According to the trial protocol, certain exclusion criteria could be evaluated during the run-in period (eg, 6-minute walk test distance, blood pressure, heart rate); patients who met these exclusion criteria were excluded during the run-in period. Participants were randomized (1:2:2:2:2:3) to neladenoson (5 mg, 10 mg, 20 mg, 30 mg, and 40 mg) or matching placebo for 20 weeks of treatment. All participants enrolled in the study received at least 1 dose of their assigned treatment.

Study Procedures

Key study procedures for this trial included the following assessments: measurement of biomarkers (eg, NT-proBNP level, troponin T level, markers of kidney function); administration of quality-of-life questionnaires (EuroQol 5 dimensions for health status and the Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire [KCCQ]17,18,19); administration of the 6-minute walk test; and comprehensive electrocardiographic and echocardiographic testing, including speckle-tracking strain analysis for global longitudinal strain (with measurement by an independent, blinded core laboratory). The 6-minute walk test was administered at screening and again at the baseline randomization visit to account for any test familiarization effects.20 The 6-minute walk test distance from the baseline randomization visit was used for the end point analysis.

Additional measures included continuous cardiac rhythm monitoring and physical activity (quantified via accelerometry), which were measured with an AVIVO patch (Medtronic) worn over the precordium for 7 consecutive days during treatment run-in, the first week of treatment, week 8, and the last week of treatment. Daily activity intensity was defined as the percentage of active periods that contributed to the total duration of activity during the period of monitoring. The percentage of activity intensity indicates the proportion of time the patient was active during the total duration of monitoring. The accelerometer uses an algorithm developed for this particular device to determine when the activity level of the patient is above a typical sedentary level.

Efficacy End Points and Adverse Events

The primary efficacy end point was the absolute change from baseline in 6-minute walk test distance after 20 weeks of treatment. Secondary efficacy end points included change from baseline to 20 weeks for each of the following: (1) activity intensity, (2) NT-proBNP level, (3) high-sensitivity troponin T level, and (4) the KCCQ overall summary score. For the primary end point of 6-minute walk test distance, the minimal clinically important difference is an increase of 40 m.21 For the KCCQ overall summary score, the potential range is 0 to 100, with 0 being the worst score and 100 being the best score (higher scores reflect better health status and quality of life), and the minimal clinically important difference is a 5-point increase.17 Additional exploratory efficacy variables included change from baseline to 20 weeks for each of the following echocardiography parameters: left ventricular global longitudinal strain, E/e′ ratio (a marker of left ventricular filling pressures), and left atrial volume; and the following clinical outcomes: cardiovascular mortality, heart failure hospitalization and urgent outpatient or emergency department visits for heart failure exacerbation, all-cause mortality, nonfatal myocardial infarction, and nonfatal stroke.

In addition to adverse and serious adverse events, additional safety end points included symptomatic bradyarrhythmias and any atrioventricular block greater than 1°; new electrocardiographic abnormalities; clinically significant arrhythmias on continuous electrocardiographic monitoring analysis; and worsening of kidney function. Treatment-emergent adverse events were defined as events that occurred after the first dose of the study drug up to 6 weeks after the last dose. All clinical end points were adjudicated centrally by a blinded, independent clinical events committee.

Statistical Analysis

Based on the assumption of a maximum effect for an absolute increase in 6-minute walk test distance of 40 m for a particular dose of neladenoson bialanate, an absolute increase of 0 m with placebo, and an SD of 80 m, an overall sample size of 216 randomized patients (using a 1:2:2:2:2:3 randomization ratio corresponding to the 5 neladenoson doses and placebo) was required to ensure a minimum power of 80% to detect the presence of a dose response. The power calculations were based on simulations in which all 5 candidate dose-response models (detailed below) were used for dose-response modeling.

To allow for a dropout rate of up to 25%, the final sample size was 288 patients. The assumptions for the power calculation (threshold of a 40-m increase as the minimal clinically important improvement in 6-minute walk test distance, with an SD of 80 m) were based on (1) a meta-regression of prior randomized clinical trials in patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension21 (due to the lack of such data in patients with HFpEF), and (2) clinical consensus among members of the trial’s steering committee.

To evaluate the primary and secondary end points, we combined the multiple comparison procedure (MCP) with modeling techniques (MCP-Mod approach) that evaluates dose-response relationships using a variety of candidate dose-response models (linear, Emax, 2 variations of sigmoidal Emax, and quadratic)22,23 (eMethods and eFigure 2 in Supplement 2). Because of the potential for type I error due to multiple comparisons, the findings for the analyses of the secondary end points should be interpreted as exploratory. In addition to the main analyses, we conducted subgroup analyses stratified by each of the following: LVEF (cut point of 55%), median NT-proBNP level, and concomitant β-blocker use. Within each subgroup, we reran the MCP-Mod analyses to evaluate whether a dose-response relationship existed.

For the main efficacy analyses presented herein, we evaluated all randomized patients who had the end point of interest at baseline and 20 weeks. We also performed a per-protocol analysis as defined in the statistical analysis plan (Supplement 1). Study participants who did not undergo the 6-minute walk test at baseline or at the end of treatment, who took concomitant medications that were not permitted during the trial, who did not meet inclusion criteria, or who were nonadherent with the study medication (defined as <80% or >120% adherence) were excluded from the per-protocol analysis. We did not perform a priori imputation for our primary analysis, and therefore excluded those with missing data for the outcome of interest.

In the prespecified sensitivity analyses, we performed multiple imputation of missing data for the primary outcome (6-minute walk test distance). For the adverse events analyses, we included all study participants who underwent randomization. In the post hoc adverse events analyses, we also performed imputation using the last observation carried forward method for the following safety outcomes: heart rate, potassium level, and kidney function.

As a prespecified secondary analysis, pairwise comparisons were performed for the neladenoson dose groups vs the placebo group without controlling for the family-wise error rate, by calculating the 90% CI for the difference in the primary efficacy end point (change in 6-minute walk test distance from baseline to 20 weeks) between each dose of neladenoson and placebo. The details regarding the analysis for treatment adherence and pharmacokinetics appear in the eMethods section in Supplement 2.

All statistical tests were performed at a significance level of .05. Significance testing was 1-sided. All analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc).

Results

Study Patients

A total of 339 patients with HFpEF (EF >45%) were enrolled into the trial and entered the run-in period (Figure 1). Of these, 34 did not complete the run-in period, with the remaining (n = 305) randomized in a 1:2:2:2:2:3 manner to the neladenoson groups (5, 10, 20, 30, or 40 mg) or placebo, respectively. Among the 305 patients who were randomized (mean age, 73.6 years [SD, 8.6 years]; 160 [53%] women; mean 6-minute walk test distance, 321.5 m), 261 (86%) completed the trial and were included in the primary analysis. Baseline demographic, clinical, laboratory, and echocardiographic characteristics were similar among the treatment groups (Table 1).

Table 1. Baseline Characteristics.

| Neladenoson Bialanate | Placebo (n = 76) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 40 mg (n = 51) | 30 mg (n = 50) | 20 mg (n = 51) | 10 mg (n = 50) | 5 mg (n = 27) | ||

| Demographics | ||||||

| Age, mean (SD), y | 73 (10) | 73 (10) | 74 (8) | 72 (11) | 74 (10) | 74 (9) |

| Sex, No. (%) | ||||||

| Men | 22 (43) | 28 (56) | 30 (59) | 24 (48) | 11 (41) | 40 (53) |

| Women | 29 (57) | 32 (64) | 21 (41) | 26 (52) | 16 (59) | 36 (47) |

| Race/ethnicity, No. (%) | ||||||

| White | 45 (88.2) | 45 (90.0) | 45 (88.2) | 44 (88.0) | 24 (88.9) | 64 (84.2) |

| Asian | 5 (9.8) | 5 (10.0) | 5 (9.8) | 6 (12.0) | 3 (11.1) | 9 (11.8) |

| Black | 1 (2.0) | 0 | 1 (2.0) | 0 | 0 | 3 (3.9) |

| Medical History, No. (%) | ||||||

| Hypertension | 42 (82.4) | 46 (92.0) | 45 (88.2) | 45 (90.0) | 25 (92.6) | 66 (86.8) |

| Obesity | 21 (41.2) | 23 (46.0) | 27 (52.9) | 18 (36.0) | 9 (33.3) | 34 (44.7) |

| Diabetes | 21 (41.2) | 22 (44.0) | 20 (39.2) | 23 (46.0) | 7 (25.9) | 36 (47.4) |

| Atrial fibrillation | 21 (41.2) | 20 (40.0) | 19 (37.3) | 18 (36.0) | 10 (37.0) | 28 (36.8) |

| Chronic kidney disease | 11 (21.6) | 10 (20.0) | 16 (31.4) | 16 (32.0) | 12 (44.4) | 17 (22.4) |

| Coronary artery disease | 8 (15.7) | 7 (14.0) | 7 (13.7) | 6 (12.0) | 6 (22.2) | 11 (14.5) |

| Smoker | ||||||

| Former | 20 (39.2) | 19 (38.0) | 19 (37.3) | 9 (18.0) | 10 (37.0) | 27 (35.5) |

| Current | 3 (5.9) | 4 (8.0) | 3 (5.9) | 7 (14.0) | 3 (11.1) | 5 (6.6) |

| Physical Examination | ||||||

| Blood pressure, mean (SD), mm Hg | ||||||

| Systolic | 132.6 (14.4) | 133.9 (13.0) | 131.5 (14.2) | 131.6 (15.3) | 133.4 (14.4) | 132.8 (15.2) |

| Diastolic | 72.7 (10.7) | 72.4 (10.6) | 73.6 (10.1) | 72.5 (10.4) | 72.3 (10.8) | 72.7 (11.8) |

| Heart rate, mean (SD), beats/min | 69.8 (11.6) | 70.4 (11.8) | 70.5 (11.5) | 71.5 (11.8) | 68.7 (11.4) | 68.1 (11.5) |

| Body mass index, mean (SD)a | 29.0 (5.8) | 29.7 (5.4) | 30.5 (5.2) | 28.7 (5.3) | 27.9 (5.8) | 29.4 (5.4) |

| Heart Failure–Related Characteristics | ||||||

| Inclusion criteria for heart failure diagnosis, No. (%) | ||||||

| Structural heart disease criteriab | 45 (88.2) | 36 (72.0) | 45 (88.2) | 44 (88.0) | 21 (77.8) | 64 (84.2) |

| Hemodynamic criteriab | 1 (2.0) | 2 (4.0) | 0 | 0 | 2 (7.4) | 3 (3.9) |

| Combination of structural heart disease and hemodynamic criteria | 5 (9.8) | 12 (24.0) | 6 (11.8) | 6 (12.0) | 4 (14.8) | 9 (11.8) |

| Left ventricular ejection fraction, mean (SD), % | 52 (13) | 59 (9) | 57 (10) | 54 (12) | 57 (10) | 57 (9) |

| Left atrial volume, mean (SD), mL | 74.9 (30.0) | 67.5 (22.0) | 80.7 (27.0) | 70.9 (26.1) | 64.9 (19.3) | 71.2 (25.2) |

| New York Heart Association classification, No. (%)c | ||||||

| II | 39 (76.5) | 31 (62.0) | 41 (80.4) | 37 (74.0) | 23 (85.2) | 61 (80.3) |

| III | 12 (23.5) | 19 (38.0) | 10 (19.6) | 13 (26.0) | 4 (14.8) | 15 (19.7) |

| KCCQ overall summary score, mean (SD)d | 62.5 (18.8) | 67.5 (18.3) | 64.6 (19.8) | 66.1 (21.2) | 64.4 (23.5) | 69.6 (17.6) |

| EQ-5D health status, mean (SD)d | 65.7 (17.2) | 64.6 (18.5) | 68.4 (17.0) | 63.0 (16.4) | 67.6 (15.8) | 66.4 (16.9) |

| 6-min walk test distance, mean (SD), m | 347 (95) | 321 (93) | 325 (105) | 296 (110) | 312 (108) | 323 (97) |

| Weekly activity intensity, mean (SD), % | 2.54 (0.75) | 2.61 (0.90) | 2.53 (0.86) | 2.86 (1.00) | 2.67 (0.75) | 2.74 (0.95) |

| Laboratory Values | ||||||

| NT-proBNP level, median (IQR), pg/mL | 860 (320-2013) | 800 (285-1721) | 850 (469-1849) | 1000 (385-1427) | 948 (389-1751) | 882 (527-1260) |

| High-sensitivity troponin T level, mean (SD), pg/mL | 21.1 (20.6) | 18.9 (17.1) | 19.2 (14.3) | 23.9 (21.2) | 30.8 (22.3) | 19.4 (14.6) |

| Estimated GFR, mean (SD), mL/min/1.73 m2 | 54.8 (20.3) | 57.4 (19.3) | 54.2 (17.3) | 57.4 (20.8) | 52.8 (23.0) | 52.3 (20.6) |

| Medications, No. (%) | ||||||

| Loop diuretics | 43 (84.3) | 41 (82.0) | 47 (92.2) | 40 (80.0) | 22 (81.5) | 64 (84.2) |

| Mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists | 26 (51.0) | 19 (38.0) | 26 (51.0) | 17 (34.0) | 13 (48.1) | 28 (36.8) |

| Thiazide diuretics | 10 (19.6) | 13 (26.0) | 19 (37.3) | 15 (30.0) | 7 (25.9) | 20 (26.3) |

| Statins | 30 (58.8) | 32 (64.0) | 30 (58.8) | 28 (56.0) | 14 (51.9) | 45 (59.2) |

| β-Blockers | 42 (82.4) | 35 (70.0) | 45 (88.2) | 38 (76.0) | 16 (59.3) | 57 (75.0) |

| Angiotensin receptor blockers | 15 (29.4) | 25 (50.0) | 15 (29.4) | 18 (36.0) | 8 (29.6) | 27 (35.5) |

| ACE inhibitors | 16 (31.4) | 14 (28.0) | 20 (39.2) | 14 (28.0) | 9 (33.3) | 30 (39.5) |

| Calcium channel blockers | 13 (25.5) | 20 (40.0) | 18 (35.3) | 18 (36.0) | 10 (37.0) | 26 (34.2) |

| Antiplatelet agents | 12 (23.5) | 23 (46.0) | 17 (33.3) | 15 (30.0) | 10 (37.0) | 26 (34.2) |

| Anticoagulants | 39 (76.5) | 31 (62.0) | 37 (72.5) | 29 (58.0) | 15 (55.6) | 52 (68.4) |

| Digitalis glycosides | 5 (9.8) | 7 (14.0) | 5 (9.8) | 3 (6.0) | 2 (7.4) | 9 (11.8) |

Abbreviations: ACE, angiotensin-converting enzyme; EQ-5D, EuroQol 5 dimensions; GFR, glomerular filtration rate; IQR, interquartile range; KCCQ, Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire; NT-proBNP, N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide.

Calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared.

Structural heart disease criteria included left atrial enlargement or left ventricular hypertrophy. Hemodynamic criteria included elevated filling pressures at rest or with exercise.

Score ranges from I to IV (best to worst); the majority of patients had mild limitations.

Score ranges from 0 to 100 (worst to best); most patients were in the moderate symptomatic range.

Comorbidities were common among the study participants. Of the 305 randomized participants (all of whom were required to be taking a diuretic at baseline), 82% were taking loop diuretics and 38% were taking mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists. All study participants had objective evidence of HFpEF (Table 1). At baseline, LVEF was preserved (mean, 56% [SD, 11%]), left atrial volume index was enlarged (mean, 39 mL/m2 [SD, 15 mL/m2]), left ventricular global longitudinal strain was abnormal (mean, −15.1% [SD, 3.8%]), and NT-proBNP level was elevated (median, 882 pg/mL; mean, 1334 pg/mL [SD, 1708 pg/mL]). At the time of enrollment into the study, the majority of the participants (76%) had New York Heart Association class II HFpEF, whereas the remaining patients (24%) had New York Heart Association class III HFpEF. Exercise capacity was severely impaired (baseline mean 6-minute walk test distance, 322 m [SD, 101 m]).

Primary End Point

Of the 305 participants who were randomized, all received at least 1 dose of the study drug, and 261 (86%) completed the trial with evaluable 6-minute walk test distance at baseline and week 20 and were therefore included in the primary analysis. After 20 weeks of treatment, the mean absolute change from baseline in 6-minute walk test distance was 0.2 m (95% CI, −12.1 to 12.4 m) for the placebo group; 19.4 m (95% CI, −10.8 to 49.7 m) for the 5 mg of neladenoson group; 29.4 m (95% CI, 3.0 to 55.8 m) for the 10 mg of neladenoson group; 13.8 m (95% CI, −2.3 to 29.8 m) for the 20 mg of neladenoson group; 16.3 m (95% CI, −1.1 to 33.6 m) for the 30 mg of neladenoson group; and 13.0 m (95% CI, −5.9 to 31.9 m) for the 40 mg of neladenoson group (Table 2). Because none of the neladenoson groups achieved the protocol-defined clinically relevant target of a 40-m increase in 6-minute walk test distance from baseline, an optimal dose of neladenoson was not identified.

Table 2. Dose-Response Results for Primary and Secondary End Points.

| Neladenoson Bialanate | Placebo | MCP-Mod Model Typesa |

P Valueb | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 40 mg | 30 mg | 20 mg | 10 mg | 5 mg | ||||

| Primary End Point | ||||||||

| No. of patients | 42 | 38 | 44 | 46 | 24 | 67 | ||

| 6-min walk distance, mean change from baseline to 20 wk (95% CI), mc | 13.0 (−5.9 to 31.9) | 16.3 (−1.1 to 33.6) | 13.8 (−2.3 to 29.8) | 29.4 (3.0 to 55.8) | 19.4 (−10.8 to 49.7) | 0.2 (−12.1 to 12.4) | Linear | .39 |

| Sigmoidal Emax1 | .21 | |||||||

| Sigmoidal Emax2 | .52 | |||||||

| Emax | .05 | |||||||

| Quadratic | .18 | |||||||

| Secondary End Points | ||||||||

| No. of patients | 38 | 34 | 38 | 36 | 22 | 55 | ||

| Physical activity intensity, mean change from baseline to 20 wk (95% CI), %c,d | −0.1 (−0.3 to 0.9) | −0.2 (−0.4 to 0.1) | −0.1 (−0.3 to 0.1) | −0.1 (−0.3 to 0.1) | −0.2 (−0.5 to 0) | −0.1 (−0.3 to 0) | Linear | .51 |

| Sigmoidal Emax1 | .46 | |||||||

| Sigmoidal Emax2 | .53 | |||||||

| Emax | .57 | |||||||

| Quadratic | .52 | |||||||

| No. of patients | 46 | 40 | 45 | 45 | 25 | 70 | ||

| KCCQ overall summary score, mean change from baseline to 20 wk (95% CI)c,e | 4.9 (0.8 to 9.1) | −1.6 (−6.4 to 3.2) | 3.7 (−0.2 to 7.7) | 0.4 (−5.2 to 6.1) | 4.9 (−2.8 to 12.6) | 0.9 (−2.3 to 5.0) | Linear | .40 |

| Sigmoidal Emax1 | .53 | |||||||

| Sigmoidal Emax2 | .47 | |||||||

| Emax | .40 | |||||||

| Quadratic | .52 | |||||||

| No. of patients | 44 | 39 | 42 | 44 | 23 | 63 | ||

| NT-proBNP level, mean change from baseline to 20 wk (95% CI), pg/mLf | 210 (−130 to 550) | 161 (−2 to 325) | 182 (−70 to 434) | 96 (−111 to 304) | −20 (−426 to 387) | 24 (−118 to 167) | Linear | >.99 |

| Sigmoidal Emax1 | >.99 | |||||||

| Sigmoidal Emax2 | >.99 | |||||||

| Emax | >.99 | |||||||

| Quadratic | >.99 | |||||||

| No. of patients | 45 | 40 | 42 | 44 | 25 | 61 | ||

| High-sensitivity troponin T level, mean change from baseline to 20 wk (95% CI), pg/mLf | 3.3 (0.6 to 6.1) | 4.4 (1.9 to 6.8) | 4.2 (1.7 to 6.7) | 2.1 (0 to 4.3) | 2.4 (−2.5 to 7.2) | 1.7 (0 to 3.5) | Linear | .99 |

| Sigmoidal Emax1 | .99 | |||||||

| Sigmoidal Emax2 | >.99 | |||||||

| Emax | .96 | |||||||

| Quadratic | >.99 | |||||||

Abbreviations: KCCQ, Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire; MCP-Mod, multiple comparison procedure with modeling techniques; NT-proBNP, N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide.

The MCP-Mod approach was applied to calculate the adjusted P values of the contrast tests for each candidate dose-response model. Model shapes appear in eFigure 2 in Supplement 2.

Tested the hypothesis that a dose-response signal corresponding to the specified MCP-Mod types had been detected.

An increase (positive value) denotes improvement and a decrease (negative value) denotes worsening.

See Methods section for calculation and meaning of physical activity intensity.

Ranges from 0 to 100; lower scores indicate lower quality of life. A 5-point increase is considered a clinically meaningful improvement.

An increase (positive value) denotes worsening and a decrease (negative value) denotes improvement.

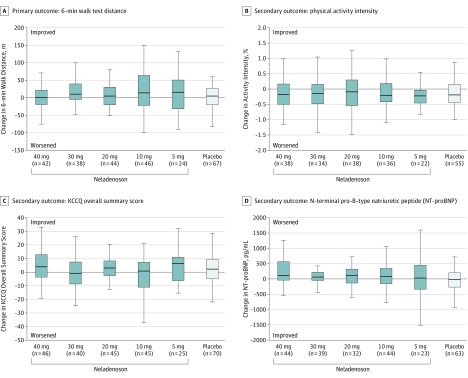

There was no significant dose-response relationship for the change in 6-minute walk test distance among the 5 different dose-response models (P = .05 for Emax; P = .18 for quadratic; P = .21 for sigmoidal Emax 1; P = .39 for linear; and P = .52 for sigmoidal Emax 2). Compared with placebo, none of the neladenoson groups differed for the primary end point of change in 6-minute walk test distance from baseline to 20 weeks of treatment (Figure 2 and eFigure 3 in Supplement 2). There were no significant differences in change in 6-minute walk test distance from baseline to 20 weeks found in the pairwise comparisons of each of the individual neladenoson treatment groups vs placebo (eTable 3 in Supplement 2). Further analyses (eFigure 4 in Supplement 2) showed the lack of change with neladenoson for 6-minute walk test distance was consistent across all subgroups tested. Multiple imputation analyses yielded similar results (eTable 4 in Supplement 2). The per-protocol analyses also yielded similar results (eFigures 5-6 and eTable 5 in Supplement 2).

Figure 2. Changes in Primary and Secondary Efficacy End Points From Baseline to 20 Weeks.

Box-and-whisker plots display median (middle line in the box), 25th percentile (lower end of box), 75th percentile (upper end of box) and 1.5 × the interquartile range (whiskers). KCCQ indicates Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire.

Secondary End Points

There was no evidence of a dose-response relationship for any of the secondary efficacy end points. Specifically, the baseline to week 20 change in KCCQ overall summary score, activity level intensity, NT-proBNP level, and high-sensitivity troponin T level did not differ significantly among treatment groups (Figure 2, Table 2, and eFigure 3 in Supplement 2). The per-protocol analyses yielded similar results (eFigures 5-6 and eTable 5 in Supplement 2).

Exploratory End Points

There was no evidence of a dose-response relationship for the 20-week changes in left ventricular global longitudinal strain, E/e′ ratio, or left atrial volume (eTable 6 in Supplement 2).

Adverse Events

The incidence of adverse events was similar for the neladenoson and placebo groups. Within the neladenoson groups, the incidence of adverse events did not indicate dose dependency (Table 3). Estimated glomerular filtration rate declined from baseline to 20 weeks with increasing doses of neladenoson (eFigure 7 in Supplement 2). In post hoc analyses of potassium level, there was a dose-dependent increase of up to 0.3 mmol/L at the highest neladenoson dose (P < .001 for all candidate model shapes), which was especially evident in the subgroup of patients taking angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blockers (eFigure 8 in Supplement 2). Heart rate decreased in the 2 highest neladenoson dose groups. A post hoc dose-response test for the absolute change in heart rate from baseline to week 20 was statistically significant for several models (eFigure 9 in Supplement 2).

Table 3. Adverse Eventsa.

| Neladenoson Bialanate | Placebo (n = 76) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 40 mg (n = 51) | 30 mg (n = 50) | 20 mg (n = 51) | 10 mg (n = 50) | 5 mg (n = 27) | All Doses (n = 229) | ||

| Any adverse event | 40 (78.4) | 34 (68.0) | 38 (74.5) | 31 (62.0) | 21 (77.8) | 164 (71.6) | 52 (68.4) |

| Related to study drug | 1 (2.0) | 11 (22.0) | 6 (11.8) | 6 (12.0) | 1 (3.7) | 25 (10.9) | 4 (5.3) |

| Related to procedure | 4 (7.8) | 3 (6.0) | 0 | 1 (2.0) | 0 | 8 (3.5) | 3 (3.9) |

| Any serious adverse event | 16 (31.4) | 14 (28.0) | 11 (21.6) | 11 (22.0) | 9 (33.3) | 61 (26.6) | 21 (27.6) |

| Related to study drug | 0 | 3 (6.0) | 1 (2.0) | 1 (2.0) | 0 | 5 (2.2) | 1 (1.3) |

| Related to procedure | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Symptomatic bradycardia | 0 | 1 (1.3) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (1.3) |

| Death | 1 (2.0) | 1 (2.0) | 1 (2.0) | 2 (4.0) | 0 | 5 (2.2) | 1 (1.3) |

| Study discontinuation | |||||||

| Due to adverse event | 1 (2.0) | 6 (12.0) | 4 (7.8) | 1 (2.0) | 0 | 12 (5.2) | 1 (1.3) |

| Due to serious adverse event | 0 | 3 (6.0) | 3 (5.9) | 0 | 0 | 6 (2.6) | 0 |

| Serious adverse event occurring in >2 patients | |||||||

| Heart failure hospitalization | 7 (13.7) | 2 (4.0) | 4 (7.8) | 3 (6.0) | 2 (7.4) | 18 (7.9) | 2 (2.6) |

| Pneumonia | 1 (2.0) | 1 (2.0) | 0 | 0 | 1 (3.7) | 3 (1.3) | 2 (2.6) |

| Acute kidney injury | 1 (2.0) | 1 (2.0) | 2 (3.9) | 0 | 0 | 4 (1.7) | 1 (1.3) |

| Atrial fibrillation | 2 (3.9) | 0 | 1 (2.0) | 0 | 0 | 3 (1.3) | 1 (1.3) |

| Acute myocardial infarction | 0 | 1 (2.0) | 1 (2.0) | 0 | 0 | 2 (0.9) | 1 (1.3) |

| Ventricular tachycardia | 1 (2.0) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.4) | 2 (2.6) |

| Adverse events occurring in ≥3% patients | |||||||

| Worsening heart failure | 9 (17.7) | 3 (6.0) | 10 (19.6) | 6 (12.0) | 4 (14.8) | 32 (14.0) | 7 (9.2) |

| Dyspnea | 3 (5.9) | 3 (6.0) | 5 (9.8) | 3 (6.0) | 2 (7.4) | 16 (7.0) | 3 (4.0) |

| Atrial fibrillation | 6 (11.8) | 1 (2.0) | 2 (3.9) | 3 (6.0) | 0 | 12 (5.2) | 6 (7.9) |

| Nasopharyngitis | 4 (7.8) | 2 (4.0) | 3 (5.9) | 3 (6.0) | 1 (3.7) | 13 (5.7) | 5 (6.6) |

| Ventricular tachycardia | 2 (3.9) | 0 | 4 (7.8) | 1 (2.0) | 0 | 7 (3.1) | 5 (6.6) |

| Constipation | 1 (2.0) | 5 (10.0) | 1 (2.0) | 2 (4.0) | 0 | 9 (3.9) | 3 (4.0) |

| Hyperkalemia | 3 (5.9) | 3 (6.0) | 1 (2.0) | 0 | 2 (7.4) | 9 (3.9) | 3 (4.0) |

| Kidney impairment | 5 (9.8) | 2 (4.0) | 1 (2.0) | 1 (2.0) | 1 (3.7) | 10 (4.4) | 1 (1.3) |

| Arthralgia | 1 (2.0) | 2 (4.0) | 4 (7.8) | 0 | 1 (3.7) | 8 (3.5) | 2 (2.6) |

Data are expressed as No. (%).

Treatment Adherence and Pharmacokinetics

Of the 305 enrolled patients, 98% had a treatment adherence of greater than 80% (range, 96%-100% across study groups; there were no significant differences among groups). Plasma concentration of neladenoson was measured throughout the trial and revealed a stepwise, proportional increase with ascending doses of neladenoson in the active treatment groups, indicating dose-linear pharmacokinetics (eFigure 10 in Supplement 2).

Discussion

There was no significant improvement in 6-minute walk test distance (the primary outcome) in the dose-response analysis of the neladenoson groups in this randomized clinical trial. Results from the per-protocol analyses were similar to the full analysis, and there were also no predefined subgroups that appeared to benefit from neladenoson. Furthermore, there were no significant improvements in any of the secondary end points (KCCQ overall score, physical activity level, or cardiac biomarkers) or in the exploratory end points (eg, markers of cardiac structure and function known to be abnormal in the setting of HFpEF). This trial also showed that neladenoson appeared to be well tolerated during the 20-week treatment period with no major adverse events; however, there was a dose-dependent reduction in heart rate and kidney function, and an increase in potassium level among patients taking neladenoson.

For patients with HFpEF, no treatments have been shown to convincingly reduce morbidity, mortality, or both.5,24,25,26 Several neurohormonal blockers (angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, angiotensin receptor blockers, and mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists) have been studied, but in contrast to patients with heart failure with reduced EF, the results in patients with HFpEF were largely null. The experience to date from these large randomized clinical trials suggests that knowledge of the pathophysiological effects of HFpEF may be incomplete and highlights the need for novel treatment targets.5

In addition, a key limitation of prior large-scale phase 3 trials of neurohormonal therapies for HFpEF was the absence of a preceding phase 2 clinical trial that could have provided important insights prior to the conduct of a pivotal trial. The current trial was an adequately powered phase 2 trial that was able to determine (using multiple domains of exercise capacity, quality of life, cardiac structure and function, and cardiac biomarkers) the development of neladenoson should not be continued for the treatment of patients with HFpEF. A large phase 3 trial should not be conducted and efforts should be directed toward alternative experimental therapeutics.

When interpreting the null results of any HFpEF trial, it is important to consider a variety of potentially contributing factors. These include determining whether (1) the patients enrolled truly had the HFpEF syndrome; (2) at least 1 of the doses of the investigated study drug was pharmacologically active; (3) the participants were adherent to the study medication; (4) the correct end points were chosen; (5) the study was adequately powered to evaluate the primary end point; and (6) the correct statistical analytic technique was performed. This trial met each of the aforementioned factors, thus increasing confidence in its results. The study participants had ample evidence of the HFpEF syndrome (Table 1) and had characteristics similar to patients enrolled in prior HFpEF studies.27 The dose-dependent effects on heart rate and kidney function, consistent with the known effects of adenosine agonism, show that the drug was pharmacologically active at the highest doses tested. Adherence data and plasma concentration data were consistent with the study participants taking the study drug and adequate absorption of the study drug. The 6-minute walk test distance was used as the primary end point to power the study, but several efficacy variables were included in secondary and exploratory analyses to ensure a multidomain approach to evaluate neladenoson broadly in patients with HFpEF to avoid the pitfalls of prior trials, such as a prior randomized clinical trial of a soluble guanylate stimulator (vericiguat) for HFpEF.28 Research on vericiguat showed improvements in physical activity level defined by the KCCQ, but lacked objective exercise capacity (eg, 6-minute walk test distance) or physical activity (accelerometry) end points that would have confirmed or refuted efficacy. The current study also was adequately powered; in fact, the sample size was larger than planned across dose groups. Furthermore, multiple doses of neladenoson were evaluated, the MCP-Mod statistical analytic technique was used to retain power across the multiple dose groups, and multiple different potential dose-response relationships were examined.

The rationale for the development of a partial adenosine A1 receptor agonist such as neladenoson to treat patients with HFpEF was based on the potential beneficial cardiac and systemic effects observed in preclinical studies (without the disadvantages of full adenosine agonism or antagonism), while preserving the cardioprotective effects of adenosine as described above.10 Despite the breadth of these preclinical studies, it is important to note they were conducted in experimental models of heart failure with reduced EF, not HFpEF. Given the differences between these 2 heart failure syndromes, adequate preclinical data in HFpEF animal models may have helped to better determine and predict the effects of neladenoson in humans with HFpEF.

In addition, the 2 pilot clinical studies of neladenoson in patients with heart failure were both conducted in patients with heart failure with reduced EF not HFpEF.15 The low prevalence of coronary artery disease among the study participants may also have factored into the null results of the trial given the purported anti-ischemic effects of neladenoson, which may be greatest in those with significant coronary disease. The high prevalence of β-blocker use in this trial may also have blunted any antiadrenergic effects of neladenoson. Furthermore, partial agonist interventions in general may prove challenging given the possibility of baseline activation of the system that is being targeted, which would limit the effectiveness of the intervention.

As observed in this study, despite the partial agonism of neladenoson, there were still observable declines in kidney function and heart rate (both known potential adverse effects of adenosine agonism) with increasing doses of the study drug, which underscores the delicate balance between adenosine agonism and antagonism in the setting of heart failure.

Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, the lack of preclinical data in HFpEF animal models was a significant limitation. Additional studies, either in large animal models more consistent with HFpEF than heart failure with reduced EF, or in smaller, more directly mechanistic studies in humans with HFpEF (including examination of direct effects on myocardial or skeletal muscle tissue), would have been appropriate to support the hypotheses tested in this trial.

Second, due to the lack of mechanistic studies on neladenoson in humans with HFpEF, it is also unclear whether the lack of any effect on the primary and secondary end points was because of lack of improvement in mitochondrial respiration with the drug (as hypothesized), or because improvements in mitochondrial respiration cannot improve exercise capacity and quality of life in the setting of HFpEF.

Third, although a multidomain approach to evaluating the efficacy of neladenoson was used, maximal exercise testing such as cardiopulmonary exercise testing (ie, peak oxygen consumption), which could have provided additional information on potential efficacy, was not performed in this trial. However, it may have been difficult to obtain cardiopulmonary exercise testing in a large multicenter trial such as this; and the consistency of null findings across all primary and secondary end points makes it unlikely to have found different results with peak oxygen consumption as the primary end point.

Fourth, the relatively short duration of the trial may have been a limitation; however, pharmacological effects in a preclinical dog model of heart failure with reduced EF were observed within 12 weeks. Nevertheless, whether improvement in 6-minute walk test distance or quality of life in HFpEF may be observed beyond the 20-week neladenoson treatment duration is unknown.

Conclusions

Among patients with HFpEF, there was no significant dose-response relationship detected for neladenoson with regard to the change in exercise capacity from baseline to 20 weeks. In light of these findings, novel approaches will be needed if further development of neladenoson for the treatment of patients with HFpEF is pursued.

Trial protocol

eMethods

eTable 1. Participating Sites and Principal Investigators

eTable 2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria for PANACHE

eTable 3. Secondary Analysis: Pairwise Comparison of Change in 6-Minute Walk Distance From Baseline to 20 Weeks Between Neladenoson Doses vs. Placebo

eTable 4. Changes in Primary Endpoint (6-Minute Walk Distance) from Baseline to 20 Weeks: Neladenoson vs. Placebo Groups (Full Analysis Set with Multiple Imputation)

eTable 5. Dose-Response Results for Primary and Secondary Endpoints: Per-protocol Set

eTable 6. Change in Echocardiographic Outcomes from Baseline to 20 Weeks: Neladenoson vs. Placebo Groups (Full Analysis Set)

eFigure 1. Study Design Overview of the PANACHE Trial

eFigure 2. Dose-Response Curves Showing Various Model Types Tested Using the MCP-Mod Approach

eFigure 3. Changes in Primary and Secondary Efficacy Endpoints From Baseline to 20 Weeks, Neladenoson vs. Placebo Treatment Groups: Parallel Line Plots (Full Analysis Set)

eFigure 4. Subgroup Analyses for the Primary End Point (6-Minute Walk Test Distance): Full Analysis Set

eFigure 5. Changes in Primary and Secondary Efficacy Endpoints From Baseline to 20 Weeks, Neladenoson vs. Placebo Treatment Groups: Box Plots (Per-Protocol Set)

eFigure 6. Changes in Primary and Secondary Efficacy Endpoints From Baseline to 20 Weeks, Neladenoson vs. Placebo Treatment Groups: Parallel Line Plots (Per-Protocol Set)

eFigure 7. Relationship between Neladenoson Bialanate Dose Groups and Estimated Glomerular Filtration Rate

eFigure 8. Relationship between Neladenoson Bialanate Dose Groups and Potassium

eFigure 9. Relationship between Neladenoson Bialanate Dose Groups and Heart Rate

eFigure 10. Plasma Concentration of Neladenoson Bialanate by Treatment Group

Data sharing statement

References

- 1.Oktay AA, Rich JD, Shah SJ. The emerging epidemic of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Curr Heart Fail Rep. 2013;10(4):401-410. doi: 10.1007/s11897-013-0155-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Redfield MM. Heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(19):1868-1877. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp1511175 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lam CS, Brutsaert DL. Endothelial dysfunction: a pathophysiologic factor in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;60(18):1787-1789. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2012.08.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Paulus WJ, Tschöpe C. A novel paradigm for heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: comorbidities drive myocardial dysfunction and remodeling through coronary microvascular endothelial inflammation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;62(4):263-271. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.02.092 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shah SJ, Kitzman DW, Borlaug BA, et al. Phenotype-specific treatment of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: a multiorgan roadmap. Circulation. 2016;134(1):73-90. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.116.021884 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Marwick TH, Shah SJ, Thomas JD. Myocardial strain in the assessment of patients with heart failure: a review. JAMA Cardiol. 2019;4(3):287-294. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2019.0052 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Borlaug BA. The pathophysiology of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2014;11(9):507-515. doi: 10.1038/nrcardio.2014.83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Borlaug BA, Olson TP, Lam CS, et al. Global cardiovascular reserve dysfunction in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;56(11):845-854. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.03.077 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pandey A, Khera R, Park B, et al. Relative impairments in hemodynamic exercise reserve parameters in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: a study-level pooled analysis. JACC Heart Fail. 2018;6(2):117-126. doi: 10.1016/j.jchf.2017.10.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dinh W, Albrecht-Küpper B, Gheorghiade M, Voors AA, van der Laan M, Sabbah HN. Partial adenosine A1 agonist in heart failure. Handb Exp Pharmacol. 2017;243:177-203. doi: 10.1007/164_2016_83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Greene SJ, Sabbah HN, Butler J, et al. Partial adenosine A1 receptor agonism: a potential new therapeutic strategy for heart failure. Heart Fail Rev. 2016;21(1):95-102. doi: 10.1007/s10741-015-9522-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Massie BM, O’Connor CM, Metra M, et al. ; PROTECT Investigators and Committees . Rolofylline, an adenosine A1-receptor antagonist, in acute heart failure. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(15):1419-1428. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0912613 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Albrecht-Küpper BE, Leineweber K, Nell PG. Partial adenosine A1 receptor agonists for cardiovascular therapies. Purinergic Signal. 2012;8(suppl 1):91-99. doi: 10.1007/s11302-011-9274-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Puhl SL, Kazakov A, Müller A, et al. Adenosine A1 receptor activation attenuates cardiac hypertrophy and fibrosis in response to α1 -adrenoceptor stimulation in vivo. Br J Pharmacol. 2016;173(1):88-102. doi: 10.1111/bph.13339 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Voors AA, Düngen HD, Senni M, et al. Safety and tolerability of neladenoson bialanate, a novel oral partial adenosine A1 receptor agonist, in patients with chronic heart failure. J Clin Pharmacol. 2017;57(4):440-451. doi: 10.1002/jcph.828 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Voors AA, Shah SJ, Bax JJ, et al. Rationale and design of the phase 2b clinical trials to study the effects of the partial adenosine A1-receptor agonist neladenoson bialanate in patients with chronic heart failure with reduced (PANTHEON) and preserved (PANACHE) ejection fraction. Eur J Heart Fail. 2018;20(11):1601-1610. doi: 10.1002/ejhf.1295 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pokharel Y, Khariton Y, Tang Y, et al. Association of serial Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire assessments with death and hospitalization in patients with heart failure with preserved and reduced ejection fraction: a secondary analysis of 2 randomized clinical trials. JAMA Cardiol. 2017;2(12):1315-1321. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2017.3983 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Filippatos G, Maggioni AP, Lam CSP, et al. Patient-reported outcomes in the SOluble guanylate Cyclase stimulatoR in heArT failurE patientS with PRESERVED ejection fraction (SOCRATES-PRESERVED) study. Eur J Heart Fail. 2017;19(6):782-791. doi: 10.1002/ejhf.800 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Joseph SM, Novak E, Arnold SV, et al. Comparable performance of the Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire in patients with heart failure with preserved and reduced ejection fraction. Circ Heart Fail. 2013;6(6):1139-1146. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.113.000359 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Maldonado-Martín S, Brubaker PH, Eggebeen J, Stewart KP, Kitzman DW. Association between 6-minute walk test distance and objective variables of functional capacity after exercise training in elderly heart failure patients with preserved ejection fraction: a randomized exercise trial. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2017;98(3):600-603. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2016.08.481 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gabler NB, French B, Strom BL, et al. Validation of 6-minute walk distance as a surrogate end point in pulmonary arterial hypertension trials. Circulation. 2012;126(3):349-356. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.112.105890 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Franchetti Y, Anderson SJ, Sampson AR. An adaptive two-stage dose-response design method for establishing proof of concept. J Biopharm Stat. 2013;23(5):1124-1154. doi: 10.1080/10543406.2013.813519 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pinheiro J, Bornkamp B, Glimm E, Bretz F. Model-based dose finding under model uncertainty using general parametric models. Stat Med. 2014;33(10):1646-1661. doi: 10.1002/sim.6052 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ponikowski P, Voors AA, Anker SD, et al. ; ESC Scientific Document Group . 2016 ESC guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure: the task force for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) developed with the special contribution of the Heart Failure Association (HFA) of the ESC. Eur Heart J. 2016;37(27):2129-2200. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehw128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yancy CW, Jessup M, Bozkurt B, et al. ; Writing Committee Members; American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines . 2013 ACCF/AHA guideline for the management of heart failure: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association task force on practice guidelines. Circulation. 2013;128(16):e240-e327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yancy CW, Jessup M, Bozkurt B, et al. 2017 ACC/AHA/HFSA focused update of the 2013 ACCF/AHA guideline for the management of heart failure: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association task force on clinical practice guidelines and the Heart Failure Society of America. Circulation. 2017;136(6):e137-e161. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000509 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shah SJ, Heitner JF, Sweitzer NK, et al. Baseline characteristics of patients in the treatment of preserved cardiac function heart failure with an aldosterone antagonist trial. Circ Heart Fail. 2013;6(2):184-192. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.112.972794 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pieske B, Maggioni AP, Lam CSP, et al. Vericiguat in patients with worsening chronic heart failure and preserved ejection fraction: results of the SOluble guanylate Cyclase stimulatoR in heArT failurE patientS with PRESERVED EF (SOCRATES-PRESERVED) study. Eur Heart J. 2017;38(15):1119-1127. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehw593 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Trial protocol

eMethods

eTable 1. Participating Sites and Principal Investigators

eTable 2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria for PANACHE

eTable 3. Secondary Analysis: Pairwise Comparison of Change in 6-Minute Walk Distance From Baseline to 20 Weeks Between Neladenoson Doses vs. Placebo

eTable 4. Changes in Primary Endpoint (6-Minute Walk Distance) from Baseline to 20 Weeks: Neladenoson vs. Placebo Groups (Full Analysis Set with Multiple Imputation)

eTable 5. Dose-Response Results for Primary and Secondary Endpoints: Per-protocol Set

eTable 6. Change in Echocardiographic Outcomes from Baseline to 20 Weeks: Neladenoson vs. Placebo Groups (Full Analysis Set)

eFigure 1. Study Design Overview of the PANACHE Trial

eFigure 2. Dose-Response Curves Showing Various Model Types Tested Using the MCP-Mod Approach

eFigure 3. Changes in Primary and Secondary Efficacy Endpoints From Baseline to 20 Weeks, Neladenoson vs. Placebo Treatment Groups: Parallel Line Plots (Full Analysis Set)

eFigure 4. Subgroup Analyses for the Primary End Point (6-Minute Walk Test Distance): Full Analysis Set

eFigure 5. Changes in Primary and Secondary Efficacy Endpoints From Baseline to 20 Weeks, Neladenoson vs. Placebo Treatment Groups: Box Plots (Per-Protocol Set)

eFigure 6. Changes in Primary and Secondary Efficacy Endpoints From Baseline to 20 Weeks, Neladenoson vs. Placebo Treatment Groups: Parallel Line Plots (Per-Protocol Set)

eFigure 7. Relationship between Neladenoson Bialanate Dose Groups and Estimated Glomerular Filtration Rate

eFigure 8. Relationship between Neladenoson Bialanate Dose Groups and Potassium

eFigure 9. Relationship between Neladenoson Bialanate Dose Groups and Heart Rate

eFigure 10. Plasma Concentration of Neladenoson Bialanate by Treatment Group

Data sharing statement