Abstract

Background

Pharmacotherapies for smoking cessation increase the likelihood of achieving abstinence in a quit attempt. It is plausible that providing support, or, if support is offered, offering more intensive support or support including particular components may increase abstinence further.

Objectives

To evaluate the effect of adding or increasing the intensity of behavioural support for people using smoking cessation medications, and to assess whether there are different effects depending on the type of pharmacotherapy, or the amount of support in each condition. We also looked at studies which directly compare behavioural interventions matched for contact time, where pharmacotherapy is provided to both groups (e.g. tests of different components or approaches to behavioural support as an adjunct to pharmacotherapy).

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Tobacco Addiction Group Specialised Register, clinicaltrials.gov, and the ICTRP in June 2018 for records with any mention of pharmacotherapy, including any type of nicotine replacement therapy (NRT), bupropion, nortriptyline or varenicline, that evaluated the addition of personal support or compared two or more intensities of behavioural support.

Selection criteria

Randomised or quasi‐randomised controlled trials in which all participants received pharmacotherapy for smoking cessation and conditions differed by the amount or type of behavioural support. The intervention condition had to involve person‐to‐person contact (defined as face‐to‐face or telephone). The control condition could receive less intensive personal contact, a different type of personal contact, written information, or no behavioural support at all. We excluded trials recruiting only pregnant women and trials which did not set out to assess smoking cessation at six months or longer.

Data collection and analysis

For this update, screening and data extraction followed standard Cochrane methods. The main outcome measure was abstinence from smoking after at least six months of follow‐up. We used the most rigorous definition of abstinence for each trial, and biochemically‐validated rates, if available. We calculated the risk ratio (RR) and 95% confidence interval (CI) for each study. Where appropriate, we performed meta‐analysis using a random‐effects model.

Main results

Eighty‐three studies, 36 of which were new to this update, met the inclusion criteria, representing 29,536 participants. Overall, we judged 16 studies to be at low risk of bias and 21 studies to be at high risk of bias. All other studies were judged to be at unclear risk of bias. Results were not sensitive to the exclusion of studies at high risk of bias. We pooled all studies comparing more versus less support in the main analysis. Findings demonstrated a benefit of behavioural support in addition to pharmacotherapy. When all studies of additional behavioural therapy were pooled, there was evidence of a statistically significant benefit from additional support (RR 1.15, 95% CI 1.08 to 1.22, I² = 8%, 65 studies, n = 23,331) for abstinence at longest follow‐up, and this effect was not different when we compared subgroups by type of pharmacotherapy or intensity of contact. This effect was similar in the subgroup of eight studies in which the control group received no behavioural support (RR 1.20, 95% CI 1.02 to 1.43, I² = 20%, n = 4,018). Seventeen studies compared interventions matched for contact time but that differed in terms of the behavioural components or approaches employed. Of the 15 comparisons, all had small numbers of participants and events. Only one detected a statistically significant effect, favouring a health education approach (which the authors described as standard counselling containing information and advice) over motivational interviewing approach (RR 0.56, 95% CI 0.33 to 0.94, n = 378).

Authors' conclusions

There is high‐certainty evidence that providing behavioural support in person or via telephone for people using pharmacotherapy to stop smoking increases quit rates. Increasing the amount of behavioural support is likely to increase the chance of success by about 10% to 20%, based on a pooled estimate from 65 trials. Subgroup analysis suggests that the incremental benefit from more support is similar over a range of levels of baseline support. More research is needed to assess the effectiveness of specific components that comprise behavioural support.

Plain language summary

Does more support increase success amongst people using medications to quit smoking?

Background

Medications (including all types of nicotine replacement therapy, bupropion and varenicline) have been shown to help people quit smoking, and people who want help to quit will often be offered medication (pharmacotherapy). Behavioural support also helps people to quit. Behavioural support may include brief advice or more intensive counselling, and may be provided face‐to‐face on a one‐to‐one basis or in groups, or by telephone, including 'quitlines'. It has been unclear how much additional benefit is gained from adding support, or providing more intensive support for people who are using medication to help them quit.

Study characteristics

We looked for studies that included smokers and provided or offered medication to everyone. People in the studies were then randomly split into groups which received different amounts or kinds of behavioural support. To assess whether the support given helped people to quit, the studies had to count the number of people not smoking after six months or more. We did not look at studies that only included pregnant women.

Key results

We searched for studies in June 2018. We included 83 studies, with almost 30,000 people. Most studies included people who wanted to quit smoking, but a small number of studies offered support to people who were not trying to quit. Combining results from 65 trials suggested that increasing the amount of behavioural support for people using a stop‐smoking medication increases the chances of quitting smoking. About 17% of people in the groups receiving less or no support quit smoking, compared to about 20% in the groups receiving more support. Providing some support via personal contact, face‐to‐face or telephone, is helpful. Few studies compared different types of support. More research is needed to find out if some types of behavioural support help more people using medication to quit smoking.

Quality of the evidence

We judged the overall quality of evidence to be high, meaning further research is very unlikely to change our results. This review has been updated twice and both times the findings remained very similar, even though many new studies were added.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings for the main comparison. Behavioural interventions as adjuncts to pharmacotherapy for smoking cessation.

| Behavioural interventions as adjuncts to pharmacotherapy for smoking cessation | ||||||

| Patient or population: People using smoking cessation pharmacotherapy Settings: Healthcare and community settings Intervention: Behavioural interventions as adjuncts to pharmacotherapy | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed successful quitters without intervention | Estimated quitters with intervention | |||||

|

Pharmacotherapy (with variable level of behavioural support) |

Additional behavioural support (in addition to pharmacotherapy) |

|||||

| Smoking cessation at longest follow‐up Follow‐up: 6 ‐ 24 months | Study population1 | RR 1.15 (1.08 to 1.22) | 23,331 (65 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ high2,3 | Effect very stable over time: updates of this analysis (15 new studies added 2015; 18 new studies added 2019) have had minimal impact on the effect estimate. Little evidence of differences in effect based on amount of support or type of pharmacotherapy provided. | |

| 171 per 1000 | 197 per 1000 (185 to 209) | |||||

| The estimated rate of quitting with behavioural intervention (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed quit rate in the control group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio; | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1Based on the control group crude average

2Sensitivity analysis removing studies at high risk of bias yielded results consistent with those from the overall analysis. A funnel plot was inconclusive but suggested there may have been slightly more small studies with large effect sizes than with small effect sizes. However, asymmetry was not clear and we did not downgrade on this basis; given the large number of included studies and the degree of homogeneity between them, it is unlikely that smaller unpublished studies showing no effect, if they existed, would significantly alter our results.

Background

Description of the condition

Giving up smoking is the most effective way for people who smoke to reduce their risk of premature death and disability. People who smoke need to quit as soon as possible using evidence‐based aids to increase their chances of success. These aids include behavioural support and pharmacotherapies.

Description of the intervention

Behavioural support interventions range from written materials containing advice on quitting to multisession group therapy programmes or repeated individual counselling in person or by telephone. Providing standard self‐help materials alone seems to have a small effect on success, but there is good evidence of a benefit of individually tailored self‐help materials or more intensive advice or counselling (Lancaster 2017; Livingstone‐Banks 2019). There is also good evidence that nicotine replacement therapy products (NRT), varenicline, and bupropion all increase the long‐term success of quit attempts (Cahill 2016; Hartmann‐Boyce 2018; Hughes 2014).

How the intervention might work

Clinical practice guidelines recommend that healthcare providers offer people who are prepared to make a quit attempt both pharmacotherapy and behavioural support. The two types of treatment are believed to have complementary modes of action, and to independently improve the chances of maintaining long‐term abstinence (Cofta‐Woerpel 2007; Hughes 1995). Although guidelines recommend intensive support to improve abstinence rates, it is also recognised that many people will not attend multiple sessions. NRT products are available over the counter without a prescription in many countries, and people who purchase them may not access any specific behavioural support. People who obtain prescriptions for pharmacotherapies may receive some support, but this may be focused on explaining the proper use of the drug and not on counselling. It therefore may be that offering additional behavioural support increases quit rates above those seen in people given pharmacotherapy alone.

Why it is important to do this review

Other Cochrane Tobacco Addiction reviews have evaluated the evidence on behavioural and pharmaceutical interventions individually (Cahill 2016; Hartmann‐Boyce 2018; Hughes 2014; Lancaster 2017; Livingstone‐Banks 2019; Matkin 2019; Stead 2017). These reviews restrict inclusion to trials where interventions are unconfounded. Trials of pharmacotherapies must provide the same amount of behavioural support (materials, advice, counselling contacts) to all participants, whether they receive active treatment, or a placebo or no medication. Likewise, when behavioural interventions are evaluated there should be no systematic difference in the offer of medications between the active and control arms of the trial. Only reviews that evaluate interventions by specific providers (e.g. nurses, Rice 2017), or in specific settings (e.g. hospitals, Rigotti 2012), may include trials of interventions that combine behavioural therapies and various medications (e.g. NRT, bupropion, varenicline).

This review is one of two that systematically identify trials of interventions that combine effective pharmacotherapies (NRT, varenicline, bupropion, nortriptyline) with behavioural support (tailored materials, brief advice, in‐person or telephone counselling). This review evaluates trials that compare different levels of behavioural intervention for people receiving any pharmacotherapy for smoking cessation, to provide an estimate of the effectiveness of intensifying behavioural support as an adjunct to pharmacotherapy, and, as such, overlaps with some separate reviews evaluating intervention types included here (e.g. Matkin 2019), which include studies of relevant behavioural therapies both on their own and as adjuncts to pharmacotherapy. The companion review (Stead 2016) includes trials in which an intervention combining pharmacotherapy and behavioural support is compared to standard care or a brief behavioural intervention without pharmacotherapy.

Objectives

To evaluate the effect of adding or increasing the intensity of behavioural support for people using smoking cessation medications, and to assess whether there are different effects depending on the type of pharmacotherapy, or the amount of support in each condition. We also look at studies which directly compare behavioural interventions matched for contact time, and where pharmacotherapy is provided to both groups (e.g. tests of different components or approaches to behavioural support as an adjunct to pharmacotherapy).

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Randomised or quasi‐randomised controlled trials.

Types of participants

We included trials that recruited people who smoke, recruited in any setting. We excluded trials that only recruited pregnant women; this population is considered in Coleman 2015. Trial participants did not need to be selected according to their interest in quitting, or their suitability for pharmacotherapy. However, since pharmacotherapy was offered or provided, participants were expected to be relatively motivated and prepared to use medication as part of their quit attempt.

Types of interventions

We included trials of smoking cessation interventions where all participants had access to a smoking cessation pharmacotherapy (including NRT, varenicline, bupropion and nortriptyline, or a combination or choice of these) and in which one or more intervention conditions received more intensive behavioural support than the control condition. Control group participants could be offered any level of support from minimal (e.g. written information provided as part of the medication prescription) to multisession counselling. The intervention could use different or additional types of therapy content (e.g. cognitive behaviour therapy, motivational interviewing). The additional support had to involve person‐to‐person contact which could be face‐to‐face or by telephone. In this update, we also included trials testing specific behavioural components that used a control matched for contract frequency and duration.

Types of outcome measures

Following the standard methodology of the Cochrane Tobacco Addiction Group, the primary outcome was smoking cessation at the longest follow‐up using the strictest definition of abstinence, i.e. preferring sustained over point prevalence abstinence and using biochemically‐validated rates, where available. In addition we noted any other abstinence outcomes reported, and conducted sensitivity analyses if the choice of outcome in a study might have altered the results of a meta‐analysis. We excluded studies which did not set out to assess smoking cessation at six months or longer.

Search methods for identification of studies

We identified trials from the Cochrane Tobacco Addiction Group's Specialised Register (the Register), and the clinical trials registries: clinicaltrials.gov, and the ICTRP. The Register is generated from regular searches of the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), MEDLINE, Embase, and PsycINFO, for trials of smoking cessation or prevention interventions. We ran our most recent searches in June 2018. At the time of the search, the Register included the results of searches of the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled trials (CENTRAL), issue 1, 2018; MEDLINE (via OVID) to update 20180531; EMBASE (via OVID) to week 201824; PsycINFO (via OVID) to update 201800528. See the Cochrane Tobacco Addiction Group website for full search strategies and list of other resources searched.

We searched the Register for records with any mention of pharmacotherapy, including any type of NRT, bupropion, nortriptyline or varenicline in title, abstract or indexing terms (see Appendix 1 for the final search strategy). We checked titles and abstracts to identify trials of interventions for smoking cessation that combined pharmacotherapy with behavioural support. We also considered for inclusion trials with a factorial design that varied both pharmacotherapy and behavioural conditions. For the first version of this review, we also tested an additional MEDLINE search using the smoking‐related terms and design limits used in the standard Register search and the MeSH terms ‘combined modality therapy’ or (Drug Therapy and (exp Behavior therapy or exp Counseling)). This search retrieved a subset of records already screened for inclusion in the Register, and was used to assess whether it might retrieve studies where there was no mention of a specific cessation pharmacotherapy in the title, abstract or indexing. We did not find any additional studies from this approach, and so did not use it for subsequent updates.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

For this version of the review, two reviewers (BH, HW, JHB) independently screened all studies for inclusion, with disagreements resolved by discussion or referral to a third reviewer.

Data extraction and management

For this version of the review, two reviewers (BH, HW, JHB, CM, JLB) independently extracted data and assessed risk of bias for each included study, with disagreements resolved by discussion or referral to a third reviewer. We extracted the following information:

Country and setting of trial

Study design

Method of recruitment, including any selection by motivation to quit

Characteristics of participants including gender, age, smoking rate

Characteristics of intervention deliverer

Common components: type, dose and duration of pharmacotherapy

Intervention components: type and duration of behavioural support

Control group components: type and duration of behavioural support

Outcomes: primary outcome length of follow‐up and definition of abstinence, other follow‐up and abstinence definitions, use of biochemical validation, adverse events

Sources of funding & potential conflicts of interest

Information used to assess risk of bias (see below)

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

We evaluated studies on the basis of the randomisation procedure, allocation concealment, incomplete outcome data assessment and any other bias using the standard Cochrane methods (Cochrane Handbook 2011). We also judged studies on the basis of detection bias, according to standard methods of the Cochrane Tobacco Addiction Group. For trials of behavioural interventions (such as those included here), it is not relevant to assess performance bias as blinding of participants and personnel is not feasible due to the nature of the intervention. In these trials, we assessed detection bias based on the outcome measure; e.g. if the outcome was objective (biochemically‐validated) or if contact was matched between arms, or both, we judged the studies as having low risk of bias, but if the outcome was self‐reported and the intervention arm received more support than the control arm, we judged differential misreport to be possible and rated these studies as having high risk of bias.

Measures of treatment effect

We expressed trial effects as a risk ratio (RR) (calculated as: quitters in treatment group/total randomised to treatment group)/(quitters in control group/total randomised to control group), alongside 95% confidence intervals (CIs). A risk ratio greater than 1 indicates a better outcome in the intervention group than in the control condition.

Unit of analysis issues

We included both individually and cluster‐randomised trials. In extracting data from cluster‐randomised trials, we considered whether study authors had made allowance for clustering in the data analysis reported, and planned to use data adjusted for clustering effects, where available.

Dealing with missing data

We reported numbers lost to follow‐up by group in the 'Risk of bias' table. Following standard Cochrane Tobacco Addiction Group methods, we assumed people lost to follow‐up to be smoking and included them in the denominators for calculating the risk ratio. We have reported any exceptions to this assumption in the 'Risk of bias' table. We noted separately any deaths during follow‐up and excluded them from denominators.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We assessed statistical heterogeneity using the I² statistic (Higgins 2003). As guided by Higgins 2003, we considered a value greater than 50% as evidence of substantial heterogeneity.

Assessment of reporting biases

We used funnel plots to assess small‐study effects and investigate the possibility of publication bias.

Data synthesis

For groups of trials where we judged meta‐analysis appropriate, we pooled RRs using a Mantel‐Haenszel random‐effects model, and reported a pooled estimate with a 95% CI.

If trials had more than one intervention condition, we compared the most intensive combination of behavioural support and pharmacotherapy to the control in the main analysis.

We categorised the intensity of behavioural support in both intervention and control conditions based on two of the categories used in the US Guidelines (Fiore 2008): ‘Total amount of contact time’ (Categories: 0, 1 to 30*, 31 to 90, 91 to 300, > 300 minutes (*guideline categories '1 to 3' and '4 ‐ 30' combined for this review)) and ‘Number of person‐to‐person sessions’ (Categories: 0*, 1 to 3*, 4 to 8, > 8 (*guideline categories '0 to 1', and '2 to 3' combined for this review)). Additionally we used the number and duration of contacts as continuous predictors in meta‐regression, described below.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We used the difference in average intensity of support (number or duration of contacts) between intervention and control conditions as the main potential feature to explain any heterogeneity. In an exploratory analysis new to this version of the review, we planned to use a non‐linear meta‐regression model in R version 3.5.2 (R program) to explore the effect of difference in number and duration of contacts on intervention effect, anticipating that differences in the intensity of support would have the largest impact when the amount of contact in the control group was smallest. However, graphs of intervention effect against these factors did not provide evidence of this non‐linear trend, and so instead results were presented graphically and summarised using a standard meta‐regression model with each of the factors as a linear predictor. Studies where the intensity of support could not be determined for one or more treatment groups were excluded from the meta‐regression.

Sensitivity analysis

We considered whether the main results were sensitive to the exclusion of studies at high risk of bias in any domain. We also considered whether the definition and duration of follow‐up or the inclusion of intermediate‐intensity arms in trials with more than two relevant arms had any impact on treatment effect.

Summary of findings table

Following standard Cochrane methodology, we created a 'Summary of findings' table for our primary outcome using the five GRADE considerations (study limitations, consistency of effect, imprecision, indirectness and publication bias) to assess the certainty of the body of evidence for each outcome, and to draw conclusions about the certainty of evidence within the text of the review.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

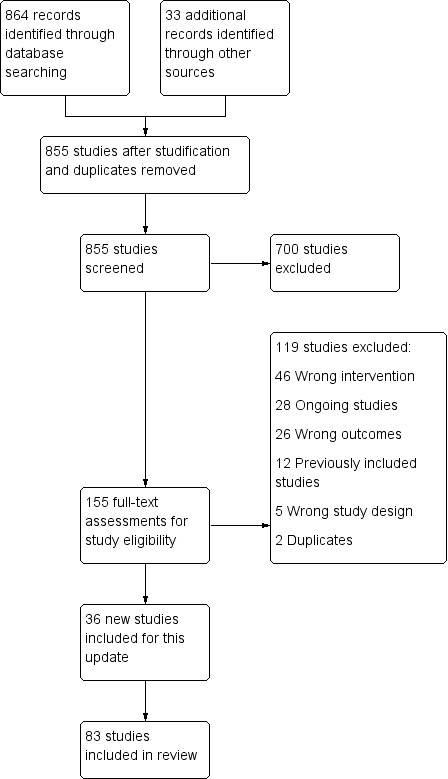

Our combined searches for all versions of this review retrieved approximately 3837 records. We excluded most of them as not relevant based on title and abstract. Of the records that did relate to trials of interventions for smoking cessation, most were not relevant because they were placebo‐controlled trials of pharmacotherapies, in which the behavioural support was the same for intervention and control conditions. We identified 83 studies for inclusion and listed 63 as excluded. We identified 36 ongoing studies. Further studies of combined pharmacotherapy and behavioural support that did not offer pharmacotherapy to the control group are included in Stead 2016. Some studies had multiple study arms and contributed to both Stead 2016 and to this review. The flow of studies is reported in Figure 1.

1.

Study flow diagram for 2019 update

Included studies

We identified 83 studies as relevant for inclusion, of which 36 were new for the 2019 update. 29,536 participants are now included in relevant arms of these studies. Details of each study are given in the Characteristics of included studies table, and a summary of intervention and control group characteristics in Table 2.

1. Summary of control and intervention characteristics.

| Intervention | Control | ||||||

| Study ID | Pharmacotherapy |

Modality (included face‐to‐face/ telephone only) |

Number of contacts | Total duration (minutes) | Number of contacts | Total duration (minutes) | Comments |

| Ahluwalia 2006 | NRT | Face‐to‐face | 6 | 120 | 6 | 120 | |

| Aimer 2017 | NRT | Face‐to‐face | 4 | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | |

| Alterman 2001 | NRT | Face‐to‐face | 16 | 4290 | 1 | 30 | Multiple arms ‐ highest vs lowest intensity |

| Aveyard 2007 | NRT | Face‐to‐face | 7 | 140 | 4 | 80 | |

| Bailey 2013 | NRT | Face‐to‐face | 19 | 950 | 10 | 500 | |

| Baker 2015 | NRT | Face‐to‐face | 17 | 1050 | 17 | 290 | |

| Bastian 2012 | NRT | Telephone | 5 | 100 | 5 | 100 | |

| Begh 2015 | NRT | Face‐to‐face | 7 | 112 | 7 | 112 | |

| Berndt 2014 | NRT | Face‐to‐face | 7 | 285 | 7 | 105 | |

| Bloom 2017 | NRT | Face‐to‐face | 20 | 400 | 20 | 880 | Exercise sessions/time excluded |

| Bock 2014 | NRT | Face‐to‐face | 3 | Unclear | 1 | Unclear | |

| Boyle 2007 | Choice | Face‐to‐face | 9 | Unclear | 0 | 0 | |

| Bricker 2014 | NRT | Telephone | 5 | 90 | 5 | 90 | |

| Brody 2017 | NRT & Bupropion | Face‐to‐face | 22 | 970 | 12 | 720 | |

| Brown 2013 | NRT | Face‐to‐face | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | |

| Busch 2017 | NRT | Face‐to‐face | 6 | 220 | 6 | 87.5 | |

| Bushnell 1997 | NRT | Face‐to‐face | 8 | 480 | 4 | 240 | |

| Calabro 2012 | NRT | Face‐to‐face | 2 | 120 | 1 | 5 | Intervention also had "access to 5 web‐based booster sessions" |

| Cook 2016 | NRT | Face‐to‐face | 11 | 130 | 0 | 0 | Multifactorial ‐ highest vs lowest intensity |

| Cropsey 2015 | NRT | Face‐to‐face | 4 | 100 | 1 | Unclear | |

| Ellerbeck 2009 | Choice | Face‐to‐face | 6 | Unclear | 0 | 0 | Multiple arms ‐ highest vs lowest intensity |

| Ferguson 2012 | NRT | Telephone | 6 | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | |

| Fiore 2004 | NRT | Face‐to‐face | 5 | Unclear | 0 | 0 | Multiple arms ‐ highest vs lowest intensity |

| Gariti 2009 | Choice | Face‐to‐face | 10 | 125 | 4 | 30 | |

| Gifford 2011 | Bupropion | Face‐to‐face | 20 | Unclear | 1 | 60 | |

| Ginsberg 1992 | NRT | Face‐to‐face | 5 | Unclear | 2 | Unclear | |

| Hall 1985 | NRT | Face‐to‐face | 14 | 1050 | 4 | Unclear | |

| Hall 1987 | NRT | Face‐to‐face | 14 | 1050 | 5 | 300 | |

| Hall 1994 | NRT | Face‐to‐face | 10 | 1200 | 5 | 450 | |

| Hall 1998 | Nortriptyline | Face‐to‐face | 10 | 1200 | 5 | 450 | |

| Hall 2002 | Bupropion/Nortriptyline | Face‐to‐face | 5 | 450 | 4 | 30 | |

| Hall 2009 | NRT & Bupropion | Face‐to‐face | 11 | 330 | 5 | Unclear | Multifactorial study design |

| Hasan 2014 | NRT | Face‐to‐face | 7 | 195 | 6 | 105 | |

| Hollis 2007 | NRT | Telephone | 4 | 100 | 1 | 15 | Multiple arms ‐ highest vs lowest intensity |

| Huber 2003 | NRT | Face‐to‐face | 5 | 450 | 5 | 225 | |

| Humfleet 2013 | NRT | Face‐to‐face | 6 | 300 | 1 | 'Brief' | Multiple arms ‐ highest vs lowest intensity |

| Jorenby 1995 | NRT | Face‐to‐face | 8 | 480 | 0 | 0 | Multiple arms ‐ highest vs lowest intensity |

| Kahler 2015 | NRT | Face‐to‐face | 6 | 210 | 6 | 210 | |

| Killen 2008 | NRT & Bupropion | Face‐to‐face | 10 | 300 | 10 | 200 | |

| Kim 2015 | NRT | Face‐to‐face | 8 | 320 | 8 | 80 | |

| LaChance 2015 | NRT | Face‐to‐face | 7 | 420 | 7 | 420 | |

| Lando 1997 | NRT | Face‐to‐face | 4 | 48 | 0 | 0 | Multiple arms ‐ highest vs lowest intensity |

| Lifrak 1997 | NRT | Face‐to‐face | 20 | 736.5 | 4 | 82.5 | |

| Lloyd‐Richardson 2009 | NRT | Face‐to‐face | 5 | Unclear | 2 | Unclear | |

| MacLeod 2003 | NRT | Telephone | 5 | 60 | 0 | 0 | |

| Macpherson 2010a | NRT | Face‐to‐face | 8 | 480 | 8 | 480 | |

| Matthews 2018 | NRT | Face‐to‐face | 6 | 540 | 6 | 540 | |

| McCarthy 2008 | Bupropion | Face‐to‐face | 13 | Unclear | 13 | Unclear | Control received 80 minutes less contact than intervention |

| NCT00879177 | NRT & Varenicline | Face‐to‐face | 9 | Unclear | 5 | Unclear | |

| Ockene 1991 | NRT | Face‐to‐face | 5 | 45 | 2 | 15 | |

| O'Cleirigh 2018 | NRT | Face‐to‐face | 10 | 600 | 5 | 100 | |

| Okuyemi 2013 | NRT | Face‐to‐face | 6 | 105 | 1 | 12.5 | |

| Otero 2006 | NRT | Face‐to‐face | 4 | 240 | 1 | 20 | Multiple arms ‐ highest vs lowest intensity |

| Patten 2017 | NRT | Face‐to‐face | 36 | 1080 | 36 | 1080 | Intervention group: "exercise counselling delivered while the participant was engaged in exercise" ‐ have left this time in as also counselling |

| Prapavessis 2016 | NRT | Face‐to‐face | 64 | 1985 | 59 | 1860 | Multiple arms ‐ highest vs lowest intensity |

| Reid 1999 | NRT | Face‐to‐face | 6 | Unclear | 3 | 45 | |

| Rohsenow 2014 | NRT | Face‐to‐face | 3 | 65 | 3 | 35 | |

| Rovina 2009 | Bupropion | Face‐to‐face | 9 | 540 | 1 | 15 | Multiple arms ‐ highest vs lowest intensity |

| Schlam 2016 | NRT | Face‐to‐face | 12 | 320 | 4 | 200 | Multifactorial study design |

| Schmitz 2007a | Bupropion | Face‐to‐face | 7 | 420 | 7 | 420 | |

| Simon 2003 | NRT | Face‐to‐face | 6 | 195 | 1 | 10 | |

| Smith 2001 | NRT | Face‐to‐face | 6 | 90 | 0 | 0 | Multiple arms ‐ highest vs lowest intensity |

| Smith 2013a | NRT | Telephone | 4 | 67 | 4 | 60 | Exact duration of contact not recorded, but averages given, intervention: 67.0 (± 25.8), control: 60.1 (± 23.9) |

| Smith 2014 | Varenicline | Face‐to‐face | 5 | Unclear | 5 | Unclear | Comparing culturally‐tailored with standard counselling ‐ duration of sessions not stated |

| Solomon 2000 | NRT | Telephone | See note | See note | 0 | 0 | Control = "access to quitline"; intervention = "up to 12 calls" ‐ averaged 7 calls at 9 minutes each |

| Solomon 2005 | NRT | Telephone | 8.2 | 80 | 0 | 0 | Intervention numbers based on average number/duration of calls |

| Stanton 2015 | NRT | Face‐to‐face | 7 | Unclear | 3 | Unclear | |

| Stein 2006 | NRT | Face‐to‐face | 3 | 65 | 2 | 5 | Control offered "up to 2 visits", intervention only offered 3rd visit if ready to quit |

| Strong 2009 | Bupropion | Face‐to‐face | 12 | 1440 | 12 | 1440 | |

| Swan 2003 | Bupropion | Telephone | 4 | Unclear | 1 | 7.5 | Multiple arms ‐ highest vs lowest intensity |

| Swan 2010 | Varenicline | Telephone | 5 | 67 | 0 | 0 | |

| Tonnesen 2006 | NRT | Face‐to‐face | 12 | 270 | 10 | 150 | |

| Van Rossem 2017 | Varenicline | Face‐to‐face | 10 | 120 | 1 | 20 | Duration of sessions not stipulated, but maximum amounts recorded in paper. Intervention: 120, control: 20 |

| Vander Weg 2016 | Choice | Telephone | 6 | 150 | 0 | 0 | Intervention sessions listed as 20 to 30 minutes ‐ control was referral to a quitline, but there were no mandated sessions, so contact listed as 0 |

| Vidrine 2016 (CBT) | NRT | Face‐to‐face | 8 | 960 | 4 | 40 | Vidrine study intervention 2 (control split) |

| Vidrine 2016 (MBAT) | NRT | Face‐to‐face | 8 | 960 | 4 | 40 | Vidrine study intervention 1 (control split) |

| Wagner 2016 | NRT | Face‐to‐face | 12 | Unclear | 12 | Unclear | Sessions' duration not reported |

| Warner 2016 | NRT | Face‐to‐face | 1 | 5 | 1 | 5 | |

| Webb Hooper 2017 | NRT | Face‐to‐face | 9 | 945 | 9 | 945 | Exact duration not listed, but approximate range given |

| Wewers 2017 | NRT | Face‐to‐face | 7 | 210 | 6 | 180 | Compared 2 interventions, less intensive counted as control |

| Wiggers 2006 | NRT | Face‐to‐face | 3 | Unclear | 1 | Unclear | |

| Williams 2010 | NRT | Face‐to‐face | 24 | 1080 | 9 | 180 | |

| Wu 2009 | NRT | Face‐to‐face | 4 | 240 | 4 | 240 | |

| Yalcin 2014 | Choice | Face‐to‐face | 14 | 730 | 9 | 150 | |

Study setting, participant recruitment and motivation

Twenty‐nine studies were conducted in a healthcare setting (excluding smoking cessation clinics); this included ten studies in primary care (Aveyard 2007; Bock 2014; Cook 2016; Ellerbeck 2009; Fiore 2004; Ockene 1991; Schlam 2016; Smith 2014; Stanton 2015; Van Rossem 2017; Wagner 2016), one in a chest clinic (Tonnesen 2006), one in a cardiovascular disease outpatient clinic (Wiggers 2006), one in a rheumatology clinic (Aimer 2017), one in an immunology clinic (Stanton 2015), three in HIV clinics (Lloyd‐Richardson 2009; Humfleet 2013; O'Cleirigh 2018), one in a lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender health centre (Matthews 2018), one in mental health clinics (Williams 2010), one in a mental health research centre (Baker 2015), three in substance abuse clinics (Lifrak 1997; Rohsenow 2014; Stein 2006), two in a Veterans Administration hospital (Brody 2017; Simon 2003), and three in cardiac wards (Berndt 2014; Busch 2017; Hasan 2014) or any ward (Warner 2016).

Since the intervention included the provision of pharmacotherapy, many of the studies recruiting in a healthcare setting recruited volunteers who were interested in making a quit attempt, but motivation to quit was not always an explicit eligibility criterion. Wiggers 2006 used a motivational interviewing approach and participants did not all make quit attempts. Ockene 1991 offered nicotine replacement therapy (NRT) and participants were not initially selected by motivation, and Ellerbeck 2009 included a small proportion of people in the 'precontemplation stage' of the transtheoretical model.

A further four studies recruited members of health maintenance organisations (HMOs) (Boyle 2007; Lando 1997; Swan 2003; Swan 2010). Boyle 2007 proactively recruited HMO members who had filled a prescription for smoking cessation medication, while the others sought volunteers by advertising to HMO members. Universities or research facilities were the study sites for five studies (Baker 2015;Bloom 2017; Prapavessis 2016; Schmitz 2007a; Webb Hooper 2017).

Forty studies recruited community volunteers interested in quitting, including three which recruited people who were attending cessation clinics (Alterman 2001; Rovina 2009; Yalcin 2014). The study setting was not explicitly stated in four studies (LaChance 2015; Macpherson 2010a; Strong 2009; Vidrine 2016).

One study recruited adolescents (Bailey 2013); all other studies were conducted in adults.

Characteristics of intervention and control conditions

Pharmacotherapy

NRT was offered in the majority of studies, with 41 providing nicotine patch only. While most of these provided a supply of NRT for between eight and 12 weeks, three studies offered only a two‐week supply (Bricker 2014; MacLeod 2003; Warner 2016). Eight studies used nicotine gum only (Ahluwalia 2006; Ginsberg 1992; Hall 1985; Hall 1987; Hall 1994; Huber 2003; Ockene 1991; Wewers 2017), one used sublingual tablets (Tonnesen 2006), and three did not specify the type (Aimer 2017; Bushnell 1997; Wagner 2016). Five studies offered patch and/or gum (Bricker 2014; Cook 2016; Humfleet 2013; Schlam 2016; Smith 2013a). Seven studies provided bupropion alone (Cropsey 2015; Gifford 2011;McCarthy 2008; Rovina 2009; Schmitz 2007a; Strong 2009; Swan 2003), one provided nortriptyline alone (Hall 1998) and four provided varenicline alone (NCT00879177; Smith 2014; Swan 2010; Van Rossem 2017). Three studies offered a choice of pharmacotherapy; NRT or bupropion (Boyle 2007; Ellerbeck 2009), or NRT, bupropion, or varenicline (Yalcin 2014). Gariti 2009 randomised participants to NRT or bupropion using a double‐dummy design. Hall 2002 randomised participants to either bupropion or nortriptyline (placebo arms not used in this review). Three studies provided combination therapy of both NRT and bupropion (Hall 2009; Killen 2008; Vander Weg 2016).

Behavioural support

The intensity of the behavioural support, in both the number of sessions and their duration, was very varied for both intervention and control conditions.

In seven trials, there was no counselling contact for the controls: in six, participants received pharmacotherapy by mail (Boyle 2007; Ellerbeck 2009; MacLeod 2003; Solomon 2000; Solomon 2005; Vander Weg 2016), and in Fiore 2004 there was no counselling or advice for the control group although there was face‐to‐face contact with study staff. In 30 studies, the control arms had between one and three contacts (which could be face‐to‐face or by telephone) and most of these had a total contact duration of between four and 30 minutes, although three had between 31 and 90 minutes contact scheduled (Gifford 2011; Lando 1997; Reid 1999). In 34 studies, the control group was scheduled to receive between four and eight contacts, with all except eight (Aveyard 2007; Bricker 2014; Cook 2016; Gariti 2009; Kim 2015; Smith 2013a; Vidrine 2016; Wu 2009) involving a total contact duration of over 90 minutes. Twelve studies offered over eight contacts for the controls (Bailey 2013; Baker 2015; Begh 2015; Bloom 2017; Brody 2017; McCarthy 2008; Patten 2017; Prapavessis 2016; Strong 2009; Webb Hooper 2017; Williams 2010; Yalcin 2014).

Typically, the intervention involved only a little more contact than the control, so that the most intensive interventions were compared with more intensive control conditions. In five trials, the intervention consisted of between one and three sessions, with a total duration of 31 to 90 minutes in most of them (Calabro 2012; Rohsenow 2014; Stein 2006; Wiggers 2006), although Calabro 2012 also provided access to a tailored internet programme. Warner 2016 offered a brief (under 5 minutes) quitline facilitation intervention. Forty‐five studies tested interventions of between four and eight sessions, about half of which were in the 91 to 300 minute‐duration category. The remaining 32 studies offered more than eight sessions, typically providing over 300 minutes of counselling in total. The number of contacts planned was not always delivered, but generally using the average number delivered would not have changed the coding category. In a few cases where the number of contacts was either not specified or open‐ended, we coded the average number delivered and noted this in the Characteristics of included studies table.

In Analysis 1.2, we grouped trials by the number of intervention and control contacts. In 12 trials, the intervention and control condition fell into the same coding category for number of contacts (one to three contacts: Calabro 2012; Rohsenow 2014; Stein 2006; Wiggers 2006; four to eight contacts: Aveyard 2007; Bushnell 1997; Huber 2003; Tonnesen 2006; Wu 2009; more than eight contacts: McCarthy 2008; Williams 2010; Yalcin 2014). A summary of the number of sessions and duration for intervention and control conditions for each trial is provided in Table 2.

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Effect of increasing behavioural support. Abstinence at longest follow‐up, Outcome 2 Subgroups by contrast in number of contacts between intervention & control.

Length of follow‐up and definitions of abstinence

The majority of the included studies followed participants for a duration of six to 12 months from the target quit date, or entry into the study. Exceptions were Hall 2009 and Ellerbeck 2009 which each had a two‐year follow‐up, and Baker 2015 with a three‐year follow‐up. The design of the Ellerbeck study, in which participants were repeatedly offered support to quit, means that participants who had quit at the end of follow‐up would not necessarily have been quit for as long as two years. Thirty‐five studies only followed participants for six months.

The majority of studies reported abstinence as a prevalence measure, rather than requiring reported sustained abstinence, or abstinence at multiple follow‐up points. Fifteen studies did not attempt any biochemical verification of self‐reported abstinence; this is discussed further in Risk of bias in included studies.

Excluded studies

We listed 63 studies as excluded, along with reasons for their exclusion, in the Characteristics of excluded studies table. The majority were excluded because they provided less than six months follow‐up. Studies in which the intervention group received both pharmacotherapy and behavioural support and the control group received neither (or just brief behavioural support) were eligible for the companion review and are included or excluded there (Stead 2016).

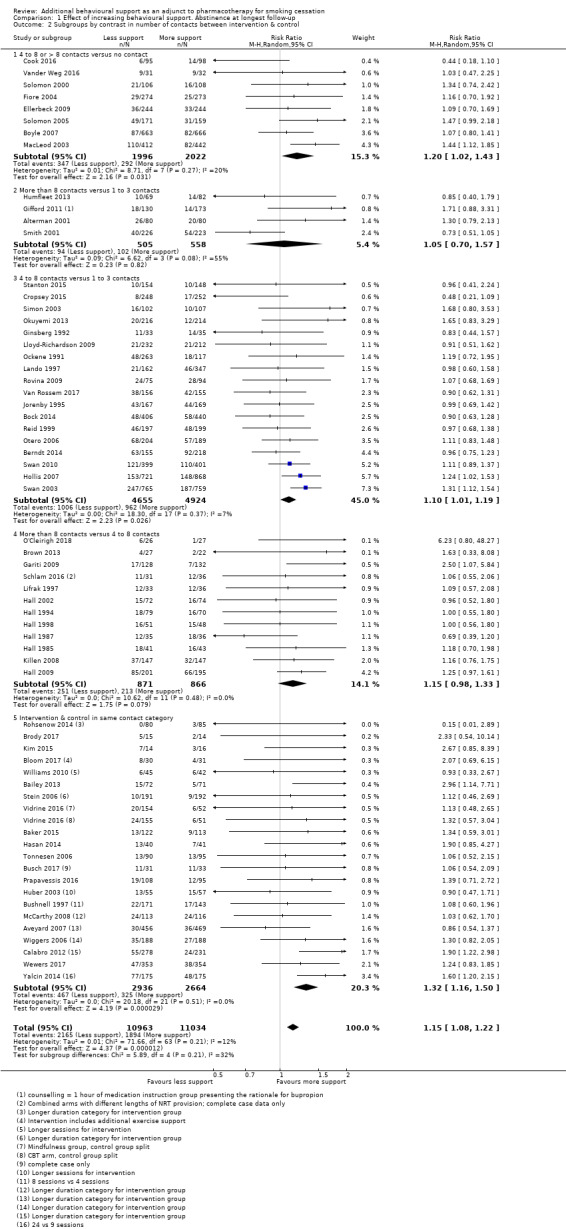

Risk of bias in included studies

Overall, we judged 16 studies to be at low risk of bias (low risk of bias across all domains) and 21 studies to be at high risk of bias (high risk of bias in at least one domain). All other studies were judged to be at unclear risk of bias. A summary of 'risk of bias' judgements can be found in Figure 2.

2.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Allocation

We judged 24 studies to be at low risk of selection bias, based on the reported method of random sequence generation and allocation concealment. We judged three studies to be at high risk of selection bias, due to the method of sequence generation (Yalcin 2014), or allocation concealment (Berndt 2014; Brown 2013; Yalcin 2014). The remaining studies did not given enough detail on one or both of these aspects so we rated the risk of bias as unclear.

Blinding (detection bias)

Following standard Cochrane Tobacco Addiction Group guidance, we did not formally assign a risk of performance bias for each trial as, due to the nature of the intervention, people providing the behavioural support could not be blinded.

We judged detection bias on the basis of biochemical validation of abstinence and, where biochemical validation was not provided, on the basis of differential levels of contact. Twelve studies were judged to be at high risk of detection bias as outcomes were via self‐report only and the intervention and control arms received different levels of support, making differential misreport possible (Aimer 2017; Berndt 2014; Boyle 2007; Cook 2016; Hollis 2007; MacLeod 2003; Ockene 1991; Otero 2006; Solomon 2005; Swan 2003; Swan 2010; Vander Weg 2016). The remainder of studies were judged to be at low risk for this domain.

Incomplete outcome data

Loss to follow‐up is often relatively high in smoking cessation trials. If trials lost fewer than 20% of participants at longest follow‐up, we judged the risk of bias to be low in this domain. In most of the included trials, the proportion lost to follow‐up was more than 20% but losses were balanced across groups and less than 40%; for these, we also classified the risk of bias as low. We rated eight studies as having unclear risk of bias, either because attrition was not reported or because overall losses to follow‐up of greater than 20% were reported and a breakdown by treatment arm was not provided (Bushnell 1997; Hall 1994; NCT00879177; Otero 2006; Schlam 2016; Smith 2001; Strong 2009; Tonnesen 2006). We judged seven studies to be at high risk of bias due to high (> 50%) attrition overall or differential rates of attrition between arms (> 20% difference between arms), as per Cochrane Tobacco Addiction Group guidance (Bock 2014; Calabro 2012; Gifford 2011; Macpherson 2010a; O'Cleirigh 2018; Smith 2014; Wagner 2016).

Other potential sources of bias

We found no studies to be at risk of other potential sources of bias.

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1

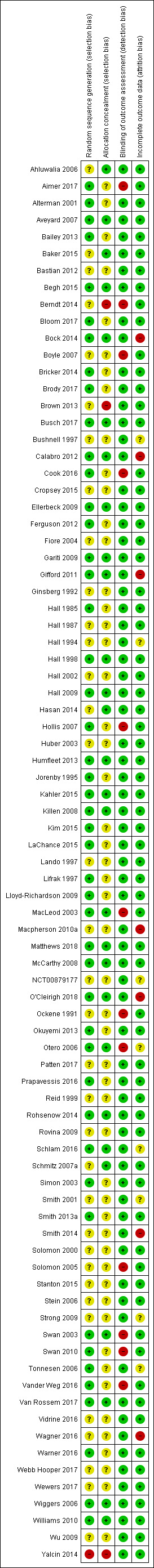

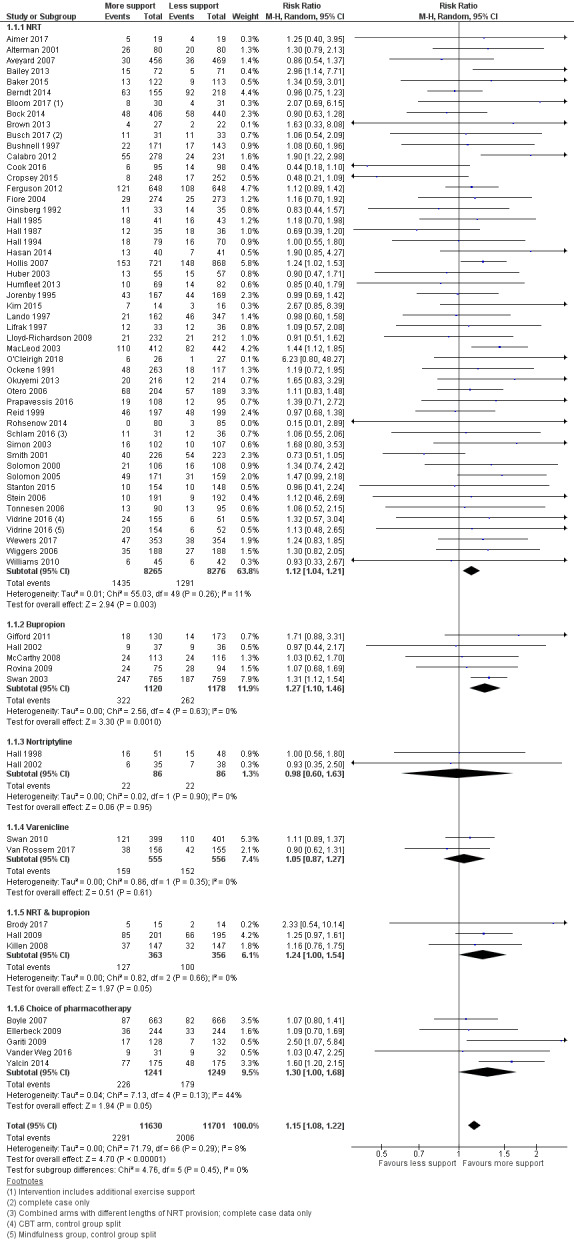

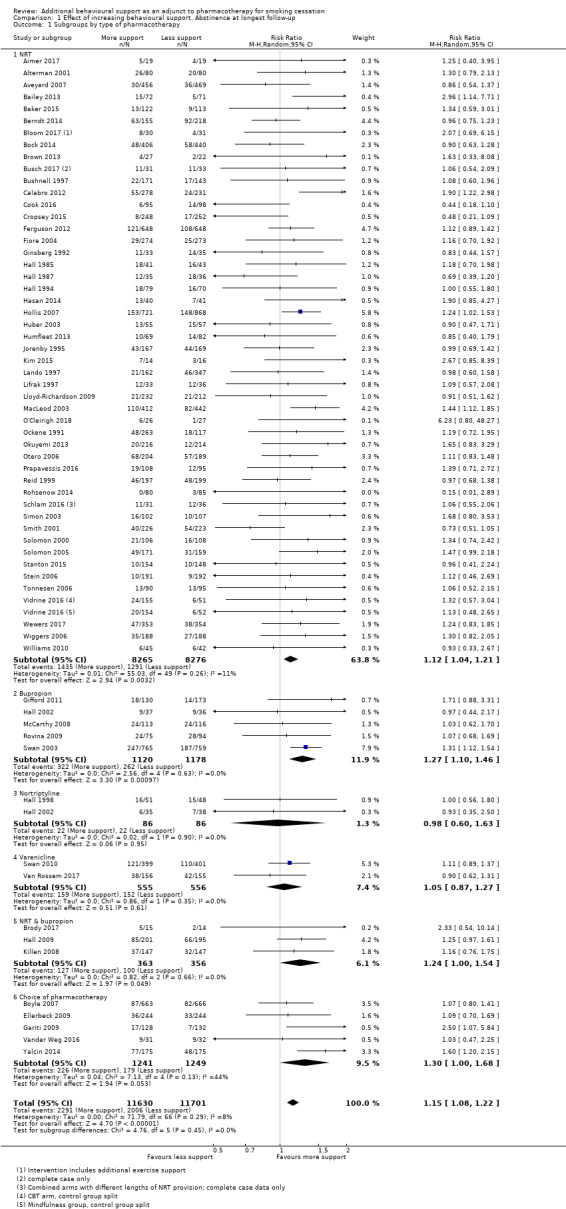

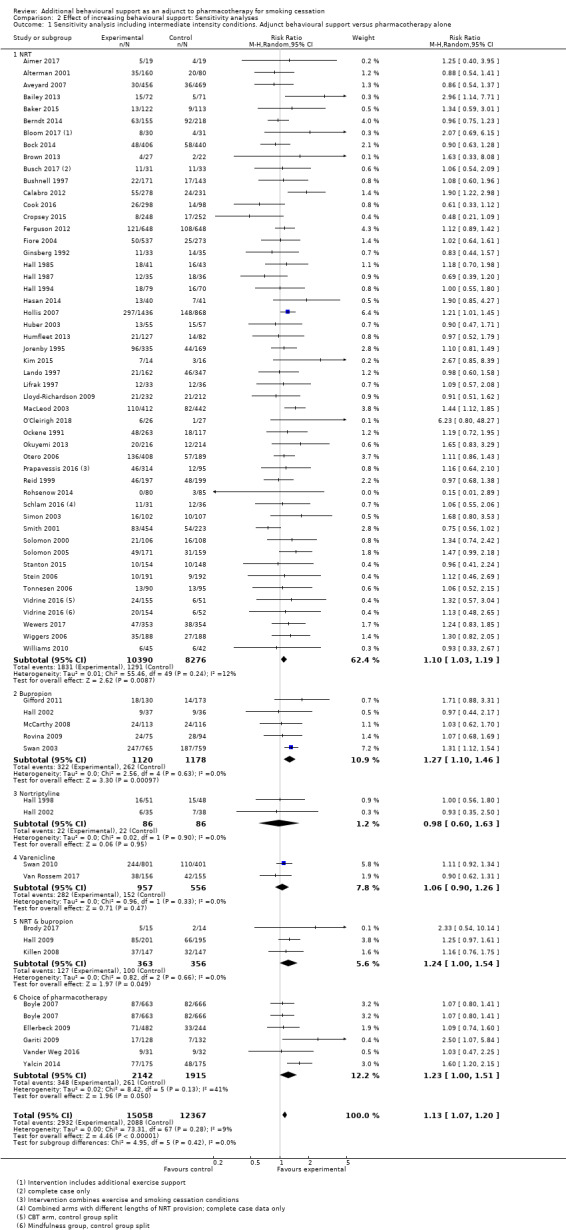

Intensive versus less intensive or no support

When comparing more intensive versus less intensive behavioural support or to no support, we pooled 65 studies contributing data to this comparison, including a total of over 23,331 participants (note: in subgroups by intervention intensity, a slightly smaller number of studies was included as, in some cases, intensity of intervention or control group contact was not clear). There was little evidence of statistical heterogeneity (I² = 8%). Hall 2002 contributed separate data to two subgroups in the primary meta‐analysis. Seventeen of the studies had point estimates below 1, that is, with higher quit rates in the less intensive condition, but all these had wide confidence intervals (CIs) which crossed the line of no effect. Seven studies detected benefits of the intervention with confidence intervals that excluded 1. The estimated risk ratio (RR) was 1.15, with 95% CI 1.08 to 1.22. This suggests that increasing the intensity of behavioural support for people making a cessation attempt with the aid of pharmacotherapy increases the proportion who are quit at six to 12 months (Figure 3; Analysis 1.1; Table 1).

3.

Effect of increasing behavioural support. Abstinence at longest follow‐up.

Subgroups by type of pharmacotherapy

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Effect of increasing behavioural support. Abstinence at longest follow‐up, Outcome 1 Subgroups by type of pharmacotherapy.

Difference in pharmacotherapy

The effect size was similar across subgroups (test for subgroup differences, P = 0.45, I² = 0%). Though in some subgroups the confidence interval included no effect, this was likely to reflect the smaller number of studies and lower precision rather than a true difference in effect.

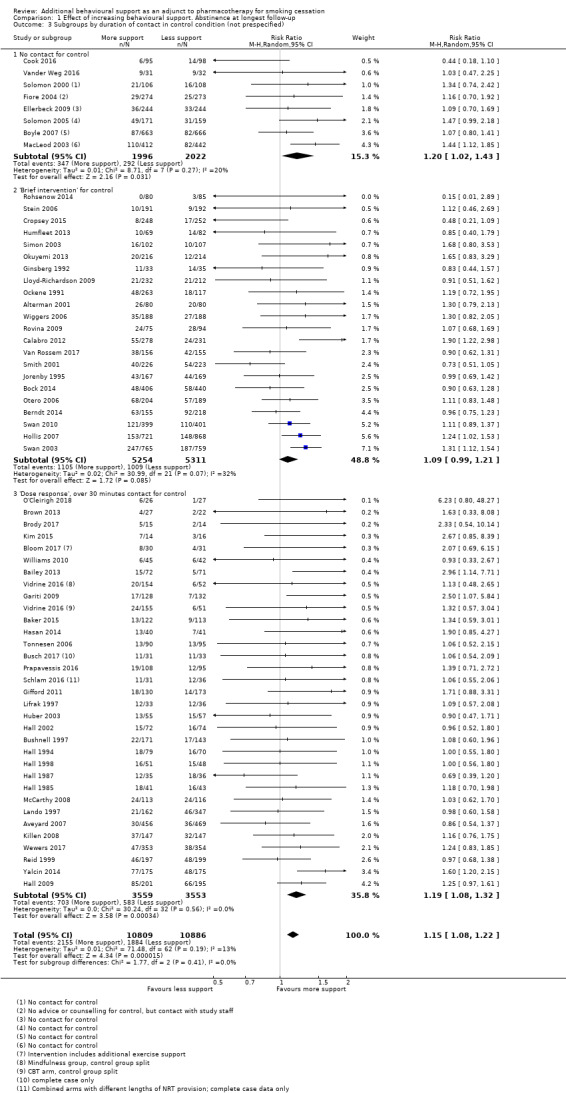

Subgroups by difference in intensity

Analysis 1.2 categorised trials based on the relative difference in the number of contacts between groups, with the subgroups with the largest contrast in intensities listed first and studies where the intensity of intervention and control fell into the same category shown last. There was little evidence of subgroup differences (P = 0.21, I² = 32%) nor was there evidence of any dose‐response. We did not repeat this approach for duration of intervention categories, as inspection suggested that the number of studies falling into different categories was small and that further subgroup analysis could be misleading.

At the suggestion of a peer reviewer, we conducted two additional subgroup analyses. In Analysis 1.3, we categorised by the level of control group contact to investigate whether there might be a difference between trials where the control could be categorised as a brief intervention (up to 30 minutes) and trials which might be characterised as testing a dose‐response for behavioural support, which we defined as being where the controls received more than 30 minutes of behavioural support. The eight trials where controls had no advice or contact formed a third subgroup. Twenty‐two trials and just over half the participants were in the 'brief intervention' subgroup, and 32 trials and a third of participants were in the 'dose‐response' category. Again, there was no significant difference between the subgroups (P = 0.41, I² = 0%).

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Effect of increasing behavioural support. Abstinence at longest follow‐up, Outcome 3 Subgroups by duration of contact in control condition (not prespecified).

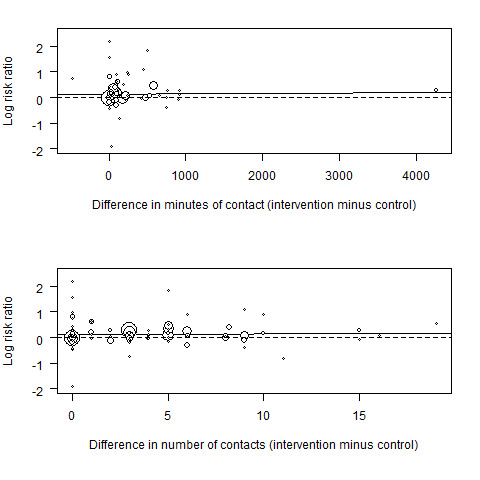

In this version of the review, we also conducted an exploratory meta‐regression to explore associations between effect sizes and number and duration of contacts. A comparison of the intervention effect (log risk ratio) by the difference between the treatment groups in the duration and number of contacts is shown in Figure 4. There was no clear effect of either increasing duration of contact (RR 1.00 per 100 minutes additional contact time, 95% CI 0.99 to 1.01) or increasing number of contacts (RR 1.00 per additional contact, 95% CI 0.99 to 1.02).

4.

Meta‐regression results (the fitted meta‐regression trend is shown as the solid line)

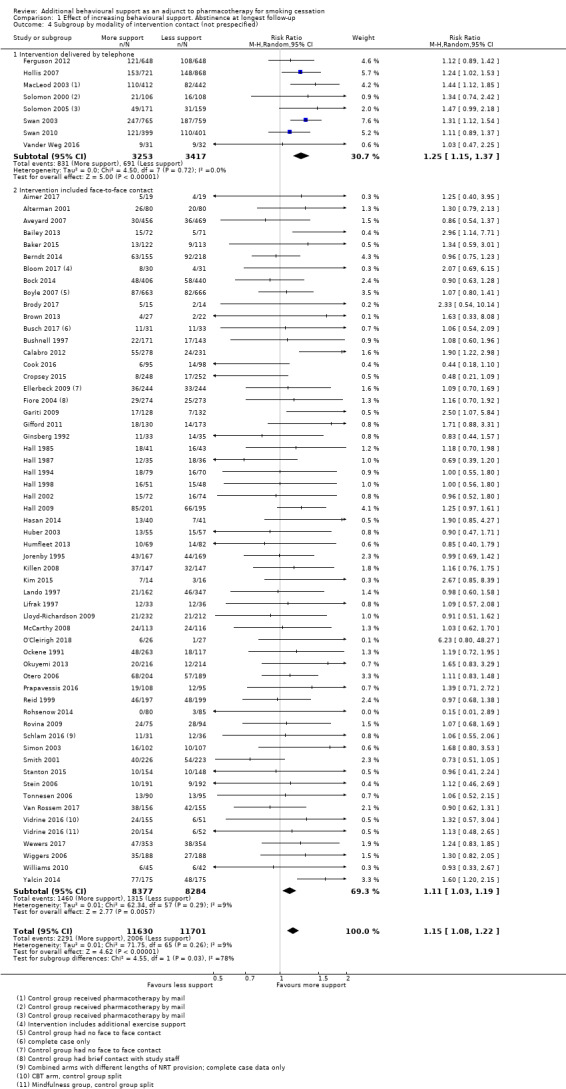

Differences in modality of intervention contact

In the second non‐prespecified analysis, we categorised studies according to whether there was some face‐to‐face contact as part of the intervention, or whether all support was given by telephone (Analysis 1.4). Here, the test for subgroup differences was significant (P = 0.03, I² = 78%), with telephone counselling showing greater relative benefit than face‐to‐face support. In the subgroup of eight studies using telephone counselling (which had some overlap with studies where there was no personal contact for the control), the point estimate was 1.25 (95% CI 1.15 to 1.37, I² = 0%, 6670 participants) in favour of additional behavioural support. In the remaining 57 studies where all intervention and most control conditions had face‐to‐face support, there was also evidence of benefit of additional behavioural support in this update, although the estimate was slightly smaller (RR 1.11, 95% CI 1.03 to 1.19, I² = 9%; 16,661 participants).

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Effect of increasing behavioural support. Abstinence at longest follow‐up, Outcome 4 Subgroup by modality of intervention contact (not prespecified).

Inclusion of medium‐intensity intervention from studies with multiple intervention conditions

Eight studies (Alterman 2001; Ellerbeck 2009; Fiore 2004; Hollis 2007; Humfleet 2013; Jorenby 1995; Prapavessis 2016; Smith 2001; Swan 2010) included an intervention condition intermediate in intensity between the highest intensity and the control. We have not included these arms in the primary analysis in case they reduced the contrast between intervention and control. In a sensitivity analysis, we added in these arms. This had almost no impact on the estimated effect (RR 1.13, 95% CI 1.07 to 1.20, I² = 8%; 65 studies, n = 27,425; Analysis 2.1), tending to support the finding that there was not a clear dose‐response relationship with the amount of support.

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Effect of increasing behavioural support: Sensitivity analyses, Outcome 1 Sensitivity analysis including intermediate intensity conditions. Adjunct behavioural support versus pharmacotherapy alone.

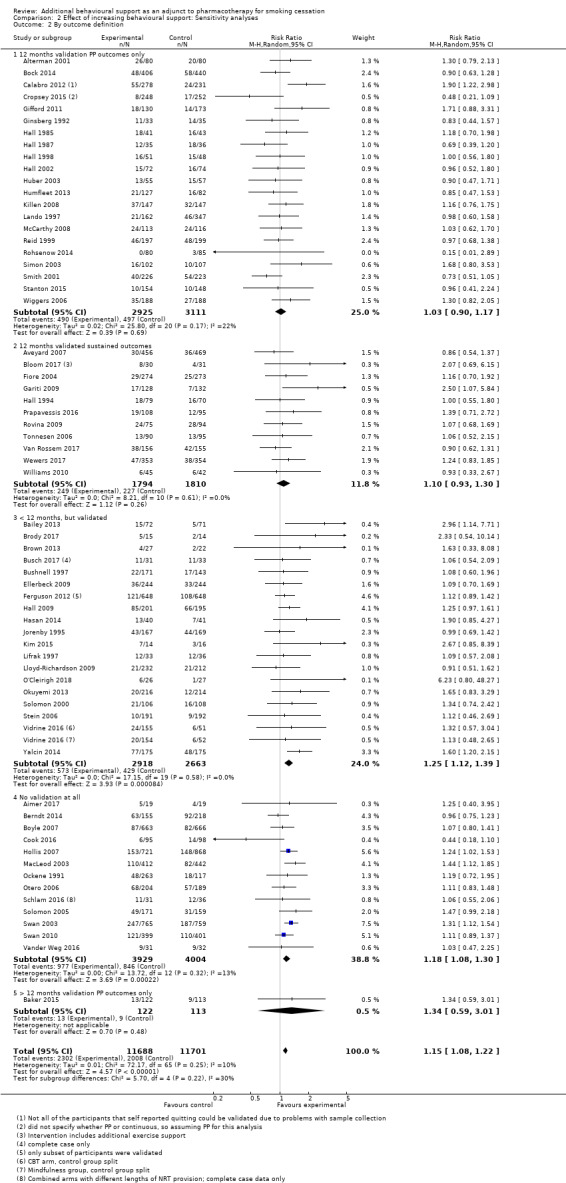

Definition of abstinence

We considered whether the way in which abstinence was defined was related to the effect size, and also to absolute quit rates. Here again, there were no significant subgroup differences (P = 0.22, I² = 30%, Analysis 2.2). Some studies that reported sustained outcomes also reported point prevalence rates, but substituting the less stringent definition did not change the overall findings. However, studies with point prevalence outcomes had, on average, higher quit rates in both intervention and control arms. A study comparing outcomes based on different abstinence definitions reported within studies found that, for pharmacotherapy studies, point prevalence and sustained abstinence outcomes were strongly related, with sustained abstinence averaging around 74% of point prevalence rates (Hughes 2010).

2.2. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Effect of increasing behavioural support: Sensitivity analyses, Outcome 2 By outcome definition.

Unit of analysis issues

Two included studies were cluster‐randomised trials (Berndt 2014; Lando 1997). One of these (Berndt 2014) performed an analysis adjusting for clustering effects and found them to be not significantly different from zero, and so we used the original data values. The other (Lando 1997) also allowed for clustering but did not report adjusted results, and so the magnitude of clustering effects was unknown. As the number of included studies in the review was large, this was not likely to have any noticeable effect on our overall conclusions.

Risk of bias

In a sensitivity analysis, removing studies judged to be at high risk of bias in at least one domain, the effect observed was consistent with that of the main analysis (RR 1.09, 95% CI 1.01 to 1.17, I² = 0%; 47 studies, n = 13355).

Studies not included in meta‐analysis

Two studies comparing more versus less intensive support were not included in the meta‐analysis due to a lack of usable data. NCT00879177 is a completed study that was not yet published at the time of searching, and while numerical data were not available, the author indicated that results were broadly comparable between groups. Wagner 2016 compared individual counselling with group counselling, and although follow‐up was conducted at later time points, the only data available at time of searching was for 12‐week quit rates, where there was no evidence of difference in quit rates (RR 0.96, 95% CI 0.51 to 1.81; n = 400).

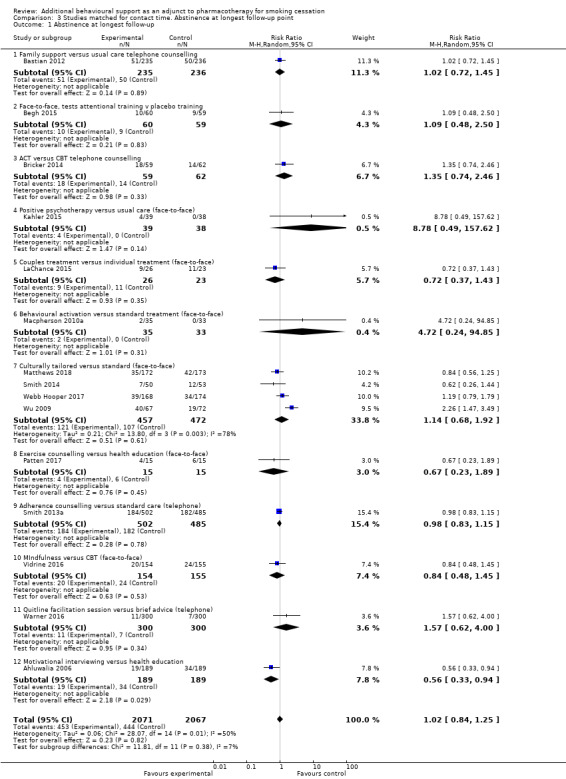

Studies matched for contact time

Seventeen studies compared interventions matched for contact time. Fifteen of these provided usable data, which is available in Analysis 3.1. Of the 12 comparisons, all had small numbers of participants and events. Only one, comparing motivational interviewing to health education (which the authors described as standard counselling containing information and advice), detected a statistically significant effect, in this case in favour of health education (RR 0.56, 95% CI 0.33 to 0.94, n = 378). Only one comparison included more than one study; this group of studies compared culturally‐tailored support with non‐tailored support. Four studies (n = 929) contributed to this comparison (RR 1.14, 95% CI 0.68 to 1.92). Statistical heterogeneity was substantial (I² = 78%) and was driven by one small study (Wu 2009; n = 139) in Chinese smokers which found a significant benefit in favour of the culturally‐tailored intervention (RR 2.26, 95% CI 1.47 to 3.49). For comparisons in which only one study contributed, see Analysis 3.1 for data and effect estimates.

3.1. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Studies matched for contact time. Abstinence at longest follow‐up point, Outcome 1 Abstinence at longest follow‐up.

A further two studies compared interventions matched for contact time but had insufficient data to be recorded in Analysis 3.1:

Schmitz 2007a compared cognitive behavioural therapy to standard therapy but quit rates in the control group could not be accessed.

Strong 2009 also compared cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) to standard therapy (ST) but we could not access quit rates beyond 12 weeks. At 12 weeks, there was "no significant difference in the risk of lapse or relapse across CBT and ST psychosocial treatments" (abstinence data not reported).

Discussion

Summary of main results

A meta‐analysis pooling 65 studies with a total of over 23,000 participants found high‐certainty evidence that providing more intensive behavioural support for people making a cessation attempt with the aid of pharmacotherapy will typically increase the success rates by about 10% to 20% (Table 1). This held true when comparing more versus less support and when comparing behavioural support to no behavioural support. This effect estimate has remained stable over time: with the addition of nine trials in 2015, the number of participants increased by 20% and yet the risk ratio remained almost the same, changing from 1.16 to 1.17; and with the addition of a further 18 trials in 2019, the number of participants increased by a further 25% and the risk ratio was 1.15. This increases confidence that there is a benefit. There continues to be little evidence of statistical heterogeneity overall, despite the variability in the amount and nature of the behavioural support tested. Direct comparisons indicate a benefit of providing more support regardless of the baseline level of support provided. Sensitivity analyses suggest that this estimate is quite robust. Although the relative effect is generally smaller than when testing behavioural support in the absence of pharmacotherapy, it is important to put the effect in the context of control conditions that were offering effective pharmacotherapy and, typically, some behavioural support, i.e. a level of support consistent with guideline best practice. Quit rates in the control groups reflected this, with a median quit rate across trials of around 17%, meaning the estimated relative increase translates into an absolute increase of around two to three percentage points. Given the importance of smoking cessation for future health outcomes, this is a clinically relevant difference (West 2007).

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

The studies identified for this review have largely been conducted in the USA or Europe. It is possible that we have failed to find relevant studies conducted in other places. Participants were typically moderate to heavy smokers and were interested in quitting. Most studies recruited participants who had already tried to quit a number of times. Most of the evidence came from studies testing additional face‐to‐face support. The eight trials which tested the addition of telephone counselling found a stronger effect in favour of additional contact, but we are unable to determine if this was based on true differences in effects or other differences between the studies.

A potential limitation of the review is that the between‐trial analysis focussed on the amount of behavioural support rather than the specific components, or the quality of delivery. However, in this update, we included studies directly comparing interventions matched for contact time (e.g. testing different behavioural approaches or types of support). Only one of the 15 comparisons detected a significant effect, but most comparisons only included one study, and all comparisons had small numbers of participants. The question of specific components of behavioural support and associations with effectiveness is being investigated further in a separate Cochrane review (Hartmann‐Boyce 2018a).

Certainty of the evidence

We judged the evidence regarding additional behavioural support to be of high certainty, meaning further research is judged very unlikely to change our confidence in the effect. This judgement is supported by the consistency of the effect estimate over time, and this is likely to be the last update of this review. However, despite high certainty in results, some areas relating to the five GRADE considerations (risk of bias, imprecision, indirectness, inconsistency, and publication bias) warrant discussion, namely risk of bias, inconsistency, and publication bias.

Risk of bias

While we judged most of the trials to be at low or unclear risk of bias, we rated 21 studies as having high risk of bias. Reassuringly, sensitivity analysis excluding studies at high risk of bias did not change the overall effect. The quality of the trials was typical of smoking cessation research in general. We did not formally evaluate whether there was a risk of performance bias due to a lack of blinding of providers or participants. Blinding of providers would not have been possible, and it was difficult to determine whether participants knew how their treatment compared to the other options offered. All participants were getting an active pharmacotherapy and would have been aware of this (apart from a small proportion in placebo‐controlled factorial studies). Expectancy effects for the behavioural components would probably have been small, and we do not think the small effect of the interventions could be attributed entirely to higher expectancies in intervention conditions.

Inconsistency

There were potentially important differences between trials in the relative difference in the support given to the intervention and control groups. Despite the lack of statistical heterogeneity, we undertook a number of subgroup analyses, including some that were not prespecified. In response to a concern that we were combining tests of behavioural support versus no support with tests of a dose‐response to intensity of support, we divided trials into those where the control did not involve personal contact; where the control group provided a brief intervention, operationalised as under 30 minutes contact; and those where the control condition was more intensive (Analysis 1.3). There was no evidence of a difference in the relative effect between these three subgroups. In this update, we also conducted an exploratory meta‐regression, in which results continue to suggest that the dose‐response curve is shallow for behavioural support. We drew similar conclusions in a companion review to this, which compared combined pharmacotherapy and behavioural support to minimal support; indirect comparisons between trials using more and less intensive behavioural interventions also failed to detect large differences (Stead 2016). The present review also detected a clearer benefit of more support in studies where all contact was delivered by telephone, but this too was not prespecified and may reflect the larger size of trials done in quitline settings, or possibly that most of these studies did not use biochemical validation of abstinence.

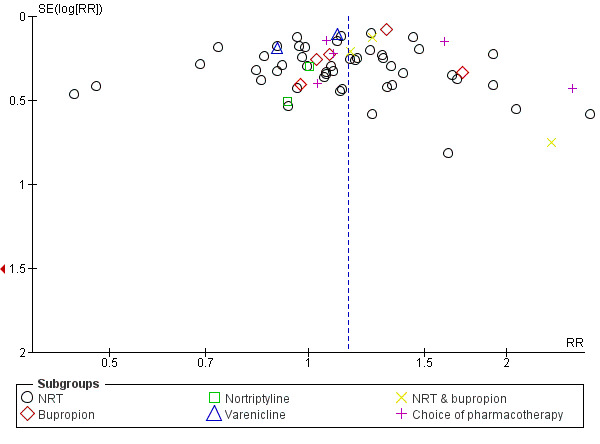

Publication bias

A funnel plot was inconclusive, suggesting there may have been slightly more small studies with large effect sizes than with small effect sizes (Figure 5). However, asymmetry was not clear and when we investigated further by conducting sensitivity analyses excluding outliers this did not substantially alter the effect. Given the large number of included studies and the degree of homogeneity between them, it is unlikely that smaller unpublished studies showing no effect, if they existed, would significantly alter our results.

5.

Funnel plot of comparison: 1 Effect of increasing behavioural support. Abstinence at longest follow‐up, outcome: 1.1 Subgroups by type of pharmacotherapy.

Potential biases in the review process

We used the Cochrane Tobacco Addiction Group's Specialised Register and searched trial registries to identify studies. The Register includes reports of trials identified from the major bibliographic databases. There is no straightforward term for the type of intervention we were interested in but we screened any trial report that mentioned a pharmacotherapy. It is possible that the Register does not include all relevant trial reports or that we failed to identify some. Our methods for data extraction and analysis are those used for other Cochrane reviews. The practice of imputing missing data as smoking has been traditionally used for primary and secondary research in smoking cessation and has the advantage that absolute cessation rates are not inflated by ignoring loss to follow‐up. Bias in the relative effect will only be introduced if misclassification differs for people who are lost from the intervention condition compared to the control. If proportionately more of those who are lost in the control group are assumed to be smokers but have in fact quit, then the treatment effect would be overestimated.

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

The major source of systematic data about the dose‐response to behavioural support is the US Public Heath Service Clinical Practice Guideline, last updated in 2008 (Fiore 2008). This includes meta‐analyses (last updated in 2000) for different levels of support and contact time. The analyses included trials of different levels of support versus control. These showed trends towards increasing effects in trials that had more sessions and more contact time, compared to minimal conditions. For example, estimated effects compared to minimal contact differed between trials with four to 30 minutes of contact time (OR 1.9, 95% CI 1.5 to 2.3) and trials with 91 to 300 minutes (OR 3.2, 95% CI 2.3 to 4.6) (Fiore 2008 Table 6.9) and between two to three treatment sessions (OR 1.4, 95% CI 1.1 to 1.7) and over eight sessions (OR 2.3, 95% CI 2.1 to 3.0) compared to 0 to 1 sessions (Fiore 2008 Table 6.10). These analyses were not limited to direct (within trial) comparisons of treatment intensity. They also did not distinguish between studies with and without pharmacotherapy, and the majority of studies in our analysis were published after 2000 so would not have been included. Our review is likely to give a more precise estimate of the effect of additional support alongside pharmacotherapy, based on the analysis of trials directly comparing different levels of support.

There is observational evidence that access to more behavioural support is associated with greater success in quitting. For example, a study of English Stop Smoking Services, in which there was a high use of pharmacotherapy, found a positive association between the number of scheduled sessions and short‐term quit rates (West 2010). A study of NRT users calling the California quitline found that people who received multiple sessions of counselling had higher quit rates after one year (Zhu 2000).

Increasingly, studies which test the effects of behavioural support provide pharmacotherapy to both arms. That means that many of the studies included here are covered (as subsets only) in other reviews of behavioural interventions. These include telephone counselling and face‐to‐face counselling, both in person and in groups (Lancaster 2017; Matkin 2019; Stead 2017). Our results from the subgroup of trials in which additional support was delivered via telephone are remarkably consistent with those from the Cochrane review of telephone counselling (Matkin 2019). Matkin 2019 also included studies without pharmacotherapy and thus had substantially more studies than our eight, but the point estimate was the same as ours in studies that recruited smokers who did not call a helpline (RR 1.25, 95% CI 1.15 to 1.35; 65 trials; 41,233 participants, I² = 52%). In the Cochrane review of individual behavioural counselling (Lancaster 2017), effects were again consistent with our findings: there was moderate‐quality evidence (downgraded due to imprecision) of a modest benefit of counselling when all participants received pharmacotherapy (RR 1.24, 95% CI 1.01 to 1.51; 6 studies, 2662 participants; I2 = 0%). The effect was stronger in studies in which participants did not receive pharmacotherapy. Similarly, in the Cochrane review of group behaviour therapy programmes (Stead 2017), the effect was stronger in studies in which participants did not receive pharmacotherapy; only five trials included pharmacotherapy, with a point estimate indicating a modest benefit but with wide confidence intervals incorporating no effect (RR 1.11, 95% CI 0.93 to 1.33, I2 = 0%; n = 1523).

Finally, one explanation for the relatively small impact of providing more behavioural support is that it is not provided at the time when it could be most effective. Relapse after initial success is the norm for quit attempts, and by the time people are getting additional calls they may already have relapsed. Various study authors commented on this (e.g. Reid 1999; Smith 2001). Although these studies are not typically characterised as being about 'relapse prevention', there is a small overlap between this review and the Cochrane review of relapse prevention interventions (Livingstone‐Banks 2019a), which concluded that there was no evidence of a benefit of additional behavioural support to prevent relapse. On the other hand, in some cases, an initial benefit of the intervention disappeared once treatment ended, and authors suggested that further extended support might have made a difference (e.g. Killen 2008; Solomon 2000), although replication of one of these studies with more extended support (Solomon 2005) still showed the same pattern of late relapse. Another possible explanation is that uptake of extended treatment may be poor, so the actual number of contacts received may not vary substantially by group. Few studies reported uptake measures.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

Providing behavioural support for smokers using established medication in an attempt to stop smoking will increase the proportion of successful attempts. This is true when comparing more versus less support and when comparing behavioural support to no behavioural support.

Implications for research.

Identifying the optimal amount of behavioural support to use alongside pharmacotherapy remains a challenge. Studies need to be appropriately powered for small treatment effects, and test interventions that are acceptable and accessible to smokers, and affordable to deliver. More studies are needed outside of the USA and Europe. Further research is needed to test associations between effectiveness and different behavioural components of interventions (which will be covered by a separate review moving forward).

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 13 March 2019 | New search has been performed | Updated with 36 new included studies. Searches run June 2018. |

| 13 March 2019 | New citation required but conclusions have not changed | New studies and analyses added; now includes contact‐matched studies and meta‐regression. Conclusions not changed. |

History

Protocol first published: Issue 2, 2012 Review first published: Issue 12, 2012

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 10 August 2015 | New citation required but conclusions have not changed | New author PK added for update |

| 10 August 2015 | New search has been performed | Searches updated, 9 new included studies |

| 21 February 2013 | Amended | Correction to 2 forest plot labels |

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Clare Miles for her assistance with data extraction. Thanks to A. Eden Evins for providing additional information on an excluded study for the previous version of this review. Thanks to Dr Karen Cropsey, Dr Stephen Smith, Dr Jessica Cook, Dr Erika Bloom, Dr Arthur Brody, Professor Harry Prapavessis, and Professor William White for providing clarifications or further information on their papers for this review update.

Lindsay Stead and Tim Lancaster conceived of and were authors of the first and second versions of this review. Pria Koilpillai was an author of the second version. Their input is greatly appreciated.

This project was supported by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR), via Cochrane Infrastructure and Cochrane Programme Grant funding to the Cochrane Tobacco Addiction Group. The views and opinions expressed therein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Systematic Reviews Programme, NIHR, NHS or the Department of Health and Social Care. JHB is also part‐funded by the NIHR Oxford Biomedical Research Centre (BRC).

Appendices

Appendix 1. Register Search

Search used in the Cochrane Register of Studies.

NRT:TI,AB,KW

(nicotine NEAR (replacement OR patch* OR transdermal OR gum OR lozenge* OR sublingual OR inhaler* OR inhalator* OR oral OR nasal OR spray)):TI,AB,KW

(bupropion OR zyban OR wellbutrin):TI,AB,KW,MH,EMT

(varenicline OR champix OR chantix):TI,AB,KW,MH,EMT

combined modality therapy:MH,KW

((behavio?r therapy) AND (drug therapy)):KW,MH,EMT,TI,AB

((counsel*) AND (*drug therapy)):KW,MH,EMT,TI,AB

#1 OR #2 OR #3 OR #4 OR #5

#6 OR #7 OR #8

#9 AND INREGISTER

Data and analyses

Comparison 1. Effect of increasing behavioural support. Abstinence at longest follow‐up.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Subgroups by type of pharmacotherapy | 65 | 23331 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.15 [1.08, 1.22] |

| 1.1 NRT | 49 | 16541 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.12 [1.04, 1.21] |

| 1.2 Bupropion | 5 | 2298 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.27 [1.10, 1.46] |

| 1.3 Nortriptyline | 2 | 172 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.98 [0.60, 1.63] |

| 1.4 Varenicline | 2 | 1111 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.05 [0.87, 1.27] |

| 1.5 NRT & bupropion | 3 | 719 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.24 [1.00, 1.54] |

| 1.6 Choice of pharmacotherapy | 5 | 2490 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.30 [1.00, 1.68] |

| 2 Subgroups by contrast in number of contacts between intervention & control | 63 | 21997 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.15 [1.08, 1.22] |

| 2.1 4 to 8 or > 8 contacts versus no contact | 8 | 4018 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.20 [1.02, 1.43] |

| 2.2 More than 8 contacts versus 1 to 3 contacts | 4 | 1063 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.05 [0.70, 1.57] |

| 2.3 4 to 8 contacts versus 1 to 3 contacts | 18 | 9579 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.10 [1.01, 1.19] |

| 2.4 More than 8 contacts versus 4 to 8 contacts | 12 | 1737 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.15 [0.98, 1.33] |

| 2.5 Intervention & control in same contact category | 21 | 5600 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.32 [1.16, 1.50] |

| 3 Subgroups by duration of contact in control condition (not prespecified) | 62 | 21695 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.15 [1.08, 1.22] |

| 3.1 No contact for control | 8 | 4018 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.20 [1.02, 1.43] |

| 3.2 'Brief intervention' for control | 22 | 10565 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.09 [0.99, 1.21] |

| 3.3 'Dose response', over 30 minutes contact for control | 32 | 7112 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.19 [1.08, 1.32] |

| 4 Subgroup by modality of intervention contact (not prespecified) | 65 | 23331 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.15 [1.08, 1.22] |

| 4.1 Intervention delivered by telephone | 8 | 6670 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.25 [1.15, 1.37] |

| 4.2 Intervention included face‐to‐face contact | 57 | 16661 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.11 [1.03, 1.19] |

Comparison 2. Effect of increasing behavioural support: Sensitivity analyses.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Sensitivity analysis including intermediate intensity conditions. Adjunct behavioural support versus pharmacotherapy alone | 65 | 27425 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.13 [1.07, 1.20] |

| 1.1 NRT | 49 | 18666 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.10 [1.03, 1.19] |

| 1.2 Bupropion | 5 | 2298 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.27 [1.10, 1.46] |

| 1.3 Nortriptyline | 2 | 172 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.98 [0.60, 1.63] |

| 1.4 Varenicline | 2 | 1513 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.06 [0.90, 1.26] |

| 1.5 NRT & bupropion | 3 | 719 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.24 [1.00, 1.54] |

| 1.6 Choice of pharmacotherapy | 5 | 4057 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.23 [1.00, 1.51] |

| 2 By outcome definition | 65 | 23389 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.15 [1.08, 1.22] |

| 2.1 12 months validation PP outcomes only | 21 | 6036 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.03 [0.90, 1.17] |

| 2.2 12 months validated sustained outcomes | 11 | 3604 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.10 [0.93, 1.30] |

| 2.3 < 12 months, but validated | 19 | 5581 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.25 [1.12, 1.39] |

| 2.4 No validation at all | 13 | 7933 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.18 [1.08, 1.30] |

| 2.5 > 12 months validation PP outcomes only | 1 | 235 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.34 [0.59, 3.01] |

Comparison 3. Studies matched for contact time. Abstinence at longest follow‐up point.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Abstinence at longest follow‐up | 15 | 4138 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.02 [0.84, 1.25] |

| 1.1 Family support versus usual care telephone counselling | 1 | 471 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.02 [0.72, 1.45] |

| 1.2 Face‐to‐face, tests attentional training v placebo training | 1 | 119 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.09 [0.48, 2.50] |

| 1.3 ACT versus CBT telephone counselling | 1 | 121 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.35 [0.74, 2.46] |

| 1.4 Positive psychotherapy versus usual care (face‐to‐face) | 1 | 77 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 8.78 [0.49, 157.62] |

| 1.5 Couples treatment versus individual treatment (face‐to‐face) | 1 | 49 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.72 [0.37, 1.43] |

| 1.6 Behavioural activation versus standard treatment (face‐to‐face) | 1 | 68 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 4.72 [0.24, 94.85] |

| 1.7 Culturally tailored versus standard (face‐to‐face) | 4 | 929 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.14 [0.68, 1.92] |

| 1.8 Exercise counselling versus health education (face‐to‐face) | 1 | 30 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.67 [0.23, 1.89] |

| 1.9 Adherence counselling versus standard care (telephone) | 1 | 987 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.98 [0.83, 1.15] |

| 1.10 MIndfulness versus CBT (face‐to‐face) | 1 | 309 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.84 [0.48, 1.45] |

| 1.11 Quitline facilitation session versus brief advice (telephone) | 1 | 600 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.57 [0.62, 4.00] |

| 1.12 Motivational interviewing versus health education | 1 | 378 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.56 [0.33, 0.94] |

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

Ahluwalia 2006.