Abstract

Disruption of brain insulin signaling may explain the higher Alzheimer’s disease (AD) risk among type 2 diabetic (T2D) patients. There is evidence from in vitro and human postmortem studies that combination of insulin with hypoglycemic medications is neuroprotective and associated with less amyloid aggregation. We examined the effect of 8-months intranasal administration of insulin, exenatide (a GLP-1 agonist), combination therapy (insulin+exenatide) or saline, in wild-type (WT) and an AD-like mouse model (Tg2576). Mice were assessed for learning, gene expression of key mediators and effectors of the insulin receptor signaling pathway (IRSP-IRS1, AKT1, CTNNB1, INSR, IRS2, GSK3B, IGF1R, AKT3), and brain Amyloid Beta (Aβ) levels. In Tg2576 mice, combination therapy reduced expression of IRSP genes which was accompanied by better learning. Cortical Aβ levels were decreased by 15–30% in all groups compared to saline but this difference did not reach statistical significance. WT mice groups, with or without treatment, did not differ in any comparison. Disentangling the mechanisms underlying the potential beneficial effects of combination therapy on the IR pathway and AD-like behavior is warranted.

Keywords: insulin, exenatide, Alzheimer’s disease, T2D

Introduction:

The insulin receptor (IR) and its substrates are widely expressed in the CNS, and particularly abundant in brain regions supporting cognition. IRs are found primarily in synapses, where insulin signaling contributes to synaptogenesis and synaptic remodeling and play a role in normal memory processes (Kleinridders, Ferris et al. 2014, Salameh, Bullock et al. 2015). Insulin, a hormone that helps regulate blood sugar, binds to the IR which phosphorylates IR substrate on a tyrosine residue, leading to activation of the canonical signaling cascade (Stanley, Macauley et al. 2016).

Current data demonstrate that insulin signaling in the brain is vital for the brain activity. Insulin signaling exerts pleiotropic effects in neurons, contributes to the control of vital brain processes including synaptic plasticity (Artola, Kamal et al. 2002, Chiu, Chen et al. 2008), neuroprotection, neurodegeneration, survival, growth, and energy metabolism (Plum, Schubert et al. 2005, van der Heide, Ramakers et al. 2006). Abolishing neuronal insulin signaling in neuron-specific insulin receptor knockout mice leads to major alterations in Akt and GSK3 phosphorylation and, presumably, activity, and hyperphosphorylation of the Tau protein at sites associated with neurodegenerative disease (Schubert, Gautam et al. 2004). Modifications in brain insulin metabolism are thought to be a pathophysiological factor underlying AD (Salameh, Bullock et al. 2015) As accumulating evidence implicates a close relationship between the brain insulin receptor signaling pathway (IRSP) and the major neurobiological abnormalities of AD—Aβ and hyperphosphorylated and conformationally abnormal tau; both pathologies have been show to lower IR responses to insulin and to cause rapid and substantial loss of neuronal surface IRs(Zhao, De Felice et al. 2008). IR desensitization increases the release of Aβ from the intracellular to the extracellular compartment (Solano, Sironi et al. 2000), which may be one mechanism for its neurotoxicity. Disruption of brain insulin signaling is one of the explanations for the consistently higher risk of AD and dementia in type 2 diabetic elderly (Morris and Burns 2012, De Felice and Ferreira 2014).

In AD patients, monotherapy with insulin (Craft, Asthana et al. 2003) or with other hypoglycemic medications (Risner, Saunders et al. 2006, Ryan, Freed et al. 2006) has shown improvement in memory performance and slowing AD symptom progression. A postmortem study, has shown that elderly subjects with T2D treated with both insulin and other hypoglycemic medications (henceforth, combination therapy) have dramatically less neuritic plaques (NPs) than otherwise similar non-T2D subjects (Beeri, Schmeidler et al. 2008). No significant NFT differences were found. Consistent with these findings, in an in vitro study insulin and metformin display opposing effects on A-beta generation, but in combined use, metformin enhances insulin’s effect in reducing Abeta levels (Chen, Zhou et al. 2009). Similarly, the protection provided by insulin against down regulation of the insulin receptor by Aβ oligomers has been shown to be significantly potentiated by the additional presence of rosiglitazone, a thiazolidinedione diabetes medication. These findings suggest that diabetes medications combination therapy may exert protection against neurodegenerative processes.

The present study examined the effect of nasal administration of diabetes medications on an AD-like mice model (Tg2576) and WT mice, on gene expression of key mediators and effectors of the IRSP. At 4 month of age mice were randomly divided into the 4 groups of treatment: insulin, glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) agonist (exenatide) (Hölscher 2011), combination therapy (i.e. insulin+ exenatide) and saline as a control. When mice reached 12 months of age, they were assessed for learning and memory. Then brains were extracted and assessed for neuropathological changes: amyloid pathology and expression of genes from the insulin receptor signaling pathway (IRS-1, AKT-1, CTNNB1, INSR, IRS-2, GSK3B, IGF1R, AKT-3).

Our results showed that combination of insulin with exenatide significantly down regulated the expression of the IRSP genes (except for IRS-2) in comparison to saline treatment in Tg mice. Results also showed that the saline Tg mice had poorer learning in the Morris Water Maze (MWM) than all the medications groups with significant differences between saline and exenatide (p=0.011) and approaching significance for the combination therapy group (p=0.12). Understanding the interaction between medications for diabetes and AD neuropathology may have significant clinical implications for strategies against cognitive compromise in aging.

Material and Methods

Animals-

We used C57BL/6J wild type (WT) and Tg2576 male mice. Male Tg2576 mice, which express human APP with the “Swedish” mutation, were purchased from Taconic (catalog #001349) at the age of 2 months and self-bred with C57BL/6J females in our lab (on C57BL/6J background). Animals were housed one per cage in a temperature-controlled room with a 12-h light-dark cycle and provided with food and water ad libitum. Mice were anesthetized with the general inhalation anesthetic 1-chloro-2,2,2-trifluoroethyldifluoromethyl ether (isoflurane; Baxter Healthcare Corp., Deerfield, IL). Mice were sacrificed by isoflurane inhalation followed by cervical dislocation. All procedures were approved by the institutional animal care and use committee of the Sheba Medical Center.

Intranasal administration of drugs -

Nasal administration has been shown to be an effective wayto deliver insulin to the brain without affecting peripheral blood sugar levels (Salameh, Bullock et al. 2015, Craft, Claxton et al. 2017, Kamei, Tanaka et al. 2017). At 4 month of age, mice were randomly divided into 4 groups of treatment. Intranasal treatments were given using a pipettor, in total volume of 5μl from stock solution for all treatments. The treatment was given 6 days a week for 8 months (from age 4 month – 12 month).

Reagents and solutions-

Insulin solutions-

NovoRapid insulin vials were purchased from Novo Nordisk at a concentration of 100 IU/ml. Mice were treated daily treatment of 0.43×10−3 IU+ 5μg bovine serum albumin (BSA). For the insulin tolerance test (ITT) assay, 0.075 IU/ml PBS was used.

Exenatide solution -

GLP-1 is a naturally occurring peptide. We used the GLP-1 agonist, Exenatide, which crosses the blood brain barrier (Daniele, Iozzo et al. 2015). Although structurally similar to the native glucagon-like peptide, this synthetic form has a much longer duration of action (Bond 2006). Exenatide Cat #hor-246 was purchased from PROSPEC and was diluted in DDW to a concentration of 1 mg/ml. Mice were treated daily with 0.075 μg exenatide+5μg BSA.

Combination therapy solution-

Daily treatment of 0.43 X10−3 IU+0.075μg exenatide +5μg BSA per mouse was used.

Insulin and glucose tolerance tests-

To examine whether the intranasal treatments had peripheral effects in addition to their effects on the brain, we performed ITT and glucose tolerance test (GTT). ITT was performed at 4 and 12 months of age. After two hours of fasting, each mouse was weighted and 0.75X10−3 IU per gram insulin was injected intraperitoneally (i.p). Tail blood glucose was measured at 15, 30 and 60 minutes after the insulin injection using a glucometer (freestyle freedom lite, Abbott Medisense). GTT was performed at the ages of 4 and 12 months. After 4 hours of fasting, mice were weighted and 10 μl per gram of 20% glucose solution (w/v) was injected intraperitoneally (i.p). Blood glucose was measured at 15, 30, 60 and 120 minutes after glucose injection. The mice were not anesthetized before performing both of the procedures.

Blood insulin-

Blood insulin in mice sera was measured by ELISA kit according to manufacturer protocol (Merck Millipore, Rat/Mouse insulin ELISA kit Cat.no. EZRMI-13K).

Morris water maze -

Morris water maze test procedure has already been described in detail elsewhere (Lubitz, Ricny et al. 2016). Briefly, mice were tested in a 140-cm circular pool filled with water at 25– 27°C and made opaque by the addition of non-toxic white acrylic paint. A platform was hidden 1.5 cm below the water level. The mice were first placed into the water facing the wall of the pool and allowed to swim until it located and climbed onto the submerged platform. Each mouse received four trials per day for 6 consecutive days of the learning phase. On the 7th day, in the probe trial, the platform was removed from the pool and mice were allowed to search for the platform for 60s. All trials were monitored by a camera above the pool. The time spent searching for the platform and the target quadrant frequency were recorded with the HVS image 2100 Plus Track video tracking system (Buckingham, UK).

Amyloid Beta-

Insoluble amyloid beta 1–42 in mice hippocampus was quantified by an ELISA kit according to manufacturer protocol (Wako, Aβ42 ELISA kit Cat. no. 298–62401).

Gene Expression-

Pellet containing the cortex was homogenized with Homogenization Solution and Proteinase k at 65°C for 30min (Quantigene Plex 2.0 Custom Reagent System, Affymetrix, Fremont, CA), samples then run on a Luminex bead-based custom multiplex array plate according to manufacturer’s instructions. Median fluorescence intensity (MFI) was generated for each target and normalized to two housekeeping genes and standards curve of each gene.

Statistical analysis-

Results are expressed as means + SEM. Differences between mean values were determined using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). Tukey posthoc tests were applied to examine specific group differences. A P-value of 0.05 was considered significant. All significance tests were two-sided. SPSS version 24.0 (IBM corporation, NY, USA) was used for data analyses.

Results

IRSP gene expression:

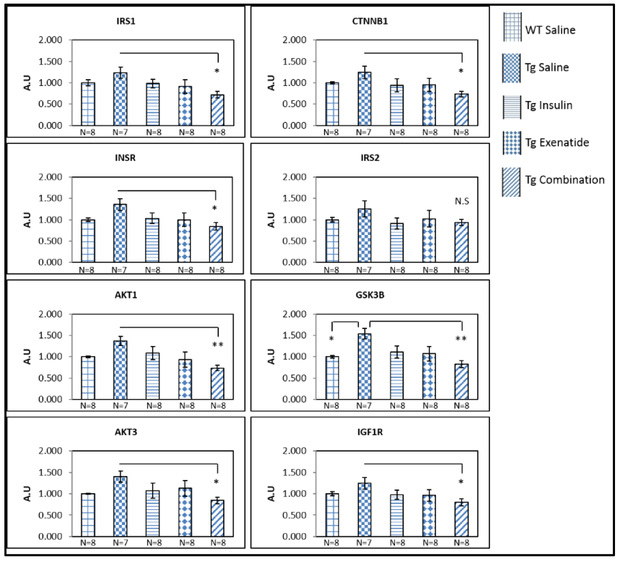

There was an overall pattern of higher mRNA expression in the Tg2576 saline group compared to the WT saline group for all IRSP genes. This difference reached significance only for GSK3B (p=0.03). Intranasal administration of diabetes medications was associated with lower gene expression; the combination of insulin with exenatide was statistically significantly lower than the Tg2576 saline group in all but the IRS2 gene (p-values ranging from p=0.002 in the GSK3B gene to 0.048 in the AKT3 gene, Figure 1). Figure S1 (online resource) depicts no differences between any of the WT groups.

Figure 1:

Significantly lower mRNA expression of the IRSP genes (except IRS2), in the hippocampus of Tg2576 mice after combination therapy treatment compared to the Tg2576 saline group. One way ANOVA test showed significant difference (≤0.05), between groups, for AKT1, IRS1 and GSK3B. CTNNB1, INSR, AKT3 and IGF1R approached significance (0.05–0.09) between groups and IRS2 was not significate between groups (p=0.48). Results were expressed as means ± SEM relative to WT saline. Statistical analysis by one way ANOVA, and posthoc Tukey tests; *P< 0.05, ** P<0.01.

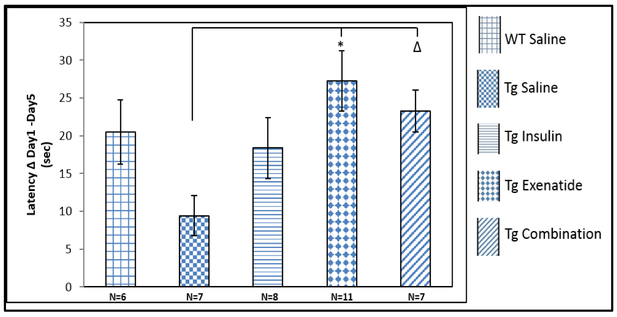

Learning-

Compared to the Tg2576 saline group, statistically significant improvement in spatial learning was found in the MWM task, after treatments with exenatide (p=0.011) The combination therapy group also improved compared to the saline group but this result did not reach significance (p=0.12; Figure 2). Figure S2 (online resource) depicts no differences in spatial learning between any of the WT groups.

Figure 2:

The latency to the platform (sec) of the first day – the latency to the platform (sec) of the last day of the task, represents the learning curve of the mice. a. All treatments showed better learning in Tg2576 mice compared to the Tg2576 saline group with significance for exenatide. Results were expressed as means ± SEM, Statistical analysis by 1-way ANOVA, posthoc Tukey test; * P=0.011, Δ P= 0.12.

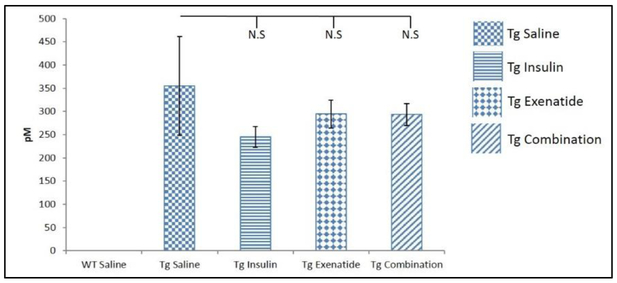

Amyloid beta:

Although a nominal decrease of 15–30% of Aβ42 was detected, none of the Tg2576 medications groups differed from the Tg2576 saline group (Figure 3). The WT groups did not have Aβ42.

Figure 3:

Aβ42 levels of mice brain hippocampus were not significantly different between the treatment groups of Tg2576 mice. Results were expressed as means ± SEM. N=5 WT saline N=6 Tg saline and Tg insulin, N=7 Tg combination, N=9 Tg exenatide.

Discussion

There is a growing body of literature implicating insulin and insulin signaling in AD (Bedse, Di Domenico et al. 2015, Diehl, Mullins et al. 2017, Pardeshi, Bolshette et al. 2017). Insulin and other drugs that modulate insulin levels and the IRSP have been suggested as potential pharmaceutical treatment for AD (Ribaric 2016, Guo, Chen et al. 2017). The present study tested the effect of intranasal treatment of insulin and exenatide, a functional analog of Glucagon-Like Peptide-1 (GLP-1), separately or in combination, on IRSP gene expression, learning abilities, and hippocampal Aβ levels. Consistent with our postmortem study, our findings show that in AD-like mice, combination therapy of insulin with exenatide, “normalize” expression of genes pertaining to the insulin receptor cascade compared to AD-like mice receiving saline. This is accompanied by better learning in the MWM, shown in the exenatide group and nominally in the combination therapy group.

Overall, Tg2576 mice on saline had higher expression of the IRSP genes, reaching significance for GSK3B. This is in contrast to some reports which found that the basal expression of some key components of the IRSP is reduced in brains of AD patients, and in agreement with other reports which found normal expression of these genes or trends for higher expression in AD brains (Moloney, Griffin et al. 2010, Bosco, Fava et al. 2011, Liu, Liu et al. 2011, Talbot, Wang et al. 2012, Bedse, Di Domenico et al. 2015, Stanley, Macauley et al. 2016). However, comparisons of our results with human subjects results have to be done with caution as most studies in humans have examined protein expression and the Tg2576 mice resemble more closely early onset rather than sporadic AD and recapitulates primarily Aβ aggregation rather than the full pathological spectrum of AD. Importantly, and supporting our results, our group has very recently published results from a study on postmortem human brain tissue showing that T2D medication “normalize” gene expression altered by AD (Katsel, Roussos et al. 2018).

Although the Tg2576 treatment groups had mildly reduced Aβ levels by 15% to 30% relative to the Tg2576-saline group, these differences were not statistically significant (Fig 3). Previous work from our group found significantly fewer neuritic plaques in brains of elderly subjects with type 2 diabetes treated with both insulin and other hypoglycemic medications relative to non-diabetic and untreated AD groups. In addition, in vitro studies have shown that addition of metformin to insulin synergistically enhances Aβ degradation (Chen, Zhou et al. 2009), and addition of rosiglitazone to insulin reverses the downregulation of the insulin receptor by Aβ oligomers (De Felice, Vieira et al. 2009).

Of note, the treatment groups did not differ from the saline group on the insulin nor the glucose tolerance tests (online resource Fig S3, S4) and on insulin levels in serum (online resource Fig S5), suggesting that the results were not affected by peripheral effects of hyperglycemia or hyperinsulinemia, both of which have been consistently shown to be associated with dementia and AD (Bosco, Fava et al. 2011, Arrieta-Cruz and Gutierrez-Juarez 2016). In addition, the differences in behavior and gene expression among the medication groups of the Tg2576 mice were not related to weight changes (online resource Fig S6), as we did not find significant effect for medication (P=0.8) nor for the interaction of medication with genotype (p=0.7).

WT mice in the different medication groups did not differ in IRSP gene expression (online resource Fig S1) nor in learning measured by the MWM (online resource Fig S2). This may indicate the relevanceof the IRSP to brain and cognitive functioning in the context of predisposition to AD but not in normal aging. Aging studies of the IRSP typically followed animals over 24 months (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4468388/table/T1/) so it is possible that the lack of gene expression alterations in this study were due to the relatively young age of the WT animals who were sacrificed at 12 months. It is possible that the overabundance of insulin and sensitizing agents cannot improve performance in the “naturally” optimized IRSP of these adult WT mice.

Among the strengths of this study was intranasal administration of medications facilitating interpretations focused on central nervous system and removing confounding influences introduced by systemic effects. In addition, intranasal medication treatment allowed long term treatment, resembling more closely treatment patterns in humans (Craft, Claxton et al. 2017). Direct and targeted delivery of insulin to the limbic system by intranasal treatment, where the highest densities of brain insulin receptors are found (Havrankova, Roth et al. 1978) may also explain the discrepancy between the beneficial effect of the treatments on the hippocampus (MWM, gene expression) and the non-significant effect of amyloid beta levels, which was measured in the cortex.

The study was limited by the relatively small number of mice in each medication group with IRSP gene expression, measurement of Aβ levels and behavioral measures. Correlations between these factors may clarify whether the gene expression alterations found in the combination therapy group may have affected AD-related pathology and behavior. The study was also limited by the need to investigate mechanisms underlying the potential beneficial effect of combination therapy on gene expression of the insulin receptor cascade and memory, including examining the expression of T2D medications on specific cell types, especially endothelial cells, as these medications have well-established beneficial effects on peripheral vascular disease (Paul, Klein et al. 2015).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments:

This research was conducted was supported by NIH grants R01 AG034087, R01 AG051545 for Dr. Beeri, VA Merit grant 1I01BX002267 for Dr. Haroutunian, as well as the Leroy Schecter Foundation and the Bader Philanthropies for Dr. Beeri.

Footnotes

Verification: all authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Arrieta-Cruz I and Gutierrez-Juarez R (2016). “The Role of Insulin Resistance and Glucose Metabolism Dysregulation in the Development of Alzheimer s Disease.” Rev Invest Clin 68(2): 53–58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Artola A, Kamal A, Ramakers GM, Gardoni F, Di Luca M, Biessels GJ, Cattabeni F and Gispen WH (2002). “Synaptic plasticity in the diabetic brain: advanced aging?” Prog Brain Res 138: 305–314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bedse G, Di Domenico F, Serviddio G and Cassano T (2015). “Aberrant insulin signaling in Alzheimer’s disease: current knowledge.” Frontiers in Neuroscience 9(204.) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beeri MS, Schmeidler J, Silverman JM, Gandy S, Wysocki M, Hannigan CM, Purohit DP, Lesser G, Grossman HT and Haroutunian V (2008). “Insulin in combination with other diabetes medication is associated with less Alzheimer neuropathology.” Neurology 71(10): 750–757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bond A (2006). “Exenatide (Byetta) as a Novel Treatment Option for Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus.” Baylor University Medical Center Proceedings 19(3): 281–284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bosco D,.Fava A, Plastino M, Montalcini T and Pujia A (2011). “Possible implications of insulin resistance and glucose metabolism in Alzheimer’s disease pathogenesis.” J Cell Mol Med 15(9): 1807–1821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bosco D, Fava A, Plastino M, Montalcini T and Pujia A”.)2011(Possible implications of insulin resistance and glucose metabolism in Alzheimer’s disease pathogenesis.” Journal of Cellular and Molecular Medicine 15(9): 1807–1821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y, Zhou K, Wang R, Liu Y, Kwak Y-D, Ma T, Thompson RC, Zhao Y, Smith L, Gasparini L, Luo Z, Xu H and Liao F-F (2009). “Antidiabetic drug metformin (GlucophageR) increases biogenesis of Alzheimer’s amyloid peptides via up-regulating BACE1 transcription.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 106(10): 3907–3912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiu SL, Chen CM and Cline HT (2008). “Insulin receptor signaling regulates synapse number, dendritic plasticity, and circuit function in vivo.” Neuron 58(5): 708–719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craft S, Asthana S, Cook DG, Baker LD, Cherrier M, Purganan K, Wait C, Petrova A, Latendresse S, Watson GS, Newcomer JW, Schellenberg GD and Krohn AJ (2003). “Insulin dose-response effects on memory and plasma amyloid precursor protein in Alzheimer’s disease: interactions with apolipoprotein E genotype.” Psychoneuroendocrinology 28(6): 809–822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craft S, Claxton A, Baker LD, Hanson AJ, Cholerton B, Trittschuh EH, Dahl D, Caulder E, Neth B, Montine TJ, Jung Y, Maldjian J, Whitlow C and Friedman S (2017). “Effects of Regular and Long-Acting Insulin on Cognition and Alzheimer’s Disease Biomarkers: A Pilot Clinical Trial.” J Alzheimers Dis 57(4): 1325–133.4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daniele G, Iozzo P, Molina-Carrion M, Lancaster J, Ciociaro D, Cersosimo E, Tripathy D, Triplitt C, Fox P, Musi N, DeFronzo R and Gastaldelli A (2015). “Exenatide Regulates Cerebral Glucose Metabolism in Brain Areas Associated With Glucose Homeostasis and Reward System.” Diabetes 64(10): 3406–3412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Felice FG and Ferreira ST (2014). “Inflammation, defective insulin signaling, and mitochondrial dysfunction as common molecular denominators connecting type 2 diabetes to Alzheimer disease.” Diabetes 63(7): 2262–2272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Felice FG, Vieira MNN, Bomfim TR, Decker H, Velasco PT, Lambert MP, Viola KL, Zhao W-Q, Ferreira ST and Klein WL (2009). “Protection of synapses against Alzheimer’s-linked toxins: Insulin signaling prevents the pathogenic binding of Aβ oligomers.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 106(6): 1971–1976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diehl T, Mullins R and Kapogiannis D (2017). “Insulin resistance in Alzheimer’s disease.” Transl Res 183: 26–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo Z, Chen Y, Mao YF, Zheng T, Jiang Y, Yan Y, Yin X and Zhang B (2017). “Long-term treatment with intranasal insulin ameliorates cognitive impairment, tau hyperphosphorylation, and microglial activation in a streptozotocin-induced Alzheimer’s rat model.” Sci Rep 7: 45971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Havrankova J, Roth J and Brownstein M (1978). “Insulin receptors are widely distributed in the central nervous system of the rat.” Nature 272: 827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hölscher C (2011). “Diabetes as a risk factor for Alzheimer’s disease: insulin signalling impairment in the brain as an alternative model of Alzheimer’s disease.” Biochemical Society Transactions 39(4): 891–897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamei N, Tanaka M, Choi H, Okada N, Ikeda T, Itokazu R and Takeda-Morishita M (2017. “.(Effect of an Enhanced Nose-to-Brain Delivery of Insulin on Mild and Progressive Memory Loss in the Senescence-Accelerated Mouse.” 14(3): 916–927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katsel P, Roussos P, Beeri MS, Gama-Sosa MA, Gandy S, Khan S and Haroutunian V (2018). “Parahippocampal gyrus expression of endothelial and insulin receptor signaling pathway genes is modulated by Alzheimer’s disease and normalized by treatment with anti-diabetic agents.” PLOS ONE 13(11): e0206547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleinridders A, Ferris HA, Cai W and Kahn CR (2014). “Insulin Action in Brain Regulates Systemic Metabolism and Brain Function.” Diabetes 63(7): 2232–2243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y, Liu F, Grundke-Iqbal I, Iqbal K and Gong C-X (2011). “Deficient brain insulin signalling pathway in Alzheimer’s disease and diabetes.” The Journal of pathology 225(1): 54–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lubitz I, Ricny J, Atrakchi-Baranes D, Shemesh C, Kravitz E, Liraz-Zaltsman S, Maksin-Matveev A, Cooper I, Leibowitz A, Uribarri J, Schmeidler J, Cai W, Kristofikova Z, Ripova D, LeRoith D and Schnaider-Beeri M (2016). “High dietary advanced glycation end products are associated with poorer spatial learning and accelerated Abeta deposition in an Alzheimer mouse model.” Aging Cell 15(2): 309–316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moloney AM, Griffin RJ, Timmons S, O’Connor R, Ravid R and O’Neill C (2010). “Defects in IGF-1 receptor, insulin receptor and IRS-1/2 in Alzheimer’s disease indicate possible resistance to IGF-1 and insulin signalling.” Neurobiol Aging 31(2): 224–243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris JK and Burns JM (2012. ”.)Insulin: an emerging treatment for Alzheimer’s disease dementia?” Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep 12(5): 520–527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pardeshi R, Bolshette N, Gadhave K, Ahire A, Ahmed S, Cassano T, Gupta VB and Lahkar M (2017). “Insulin signaling: An opportunistic target to minify the risk of Alzheimer’s disease.” Psychoneuroendocrinology 83: 159–171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paul SK, Klein K, Maggs D and Best JH (2015). “The association of the treatment with glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonist exenatide or insulin with cardiovascular outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes: a retrospective observational study.” Cardiovascular Diabetology 14(1): 10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plum L, Schubert M and Bruning JC (2005). “The role of insulin receptor signaling in the brain.” Trends Endocrinol Metab.59–65 :(2)16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ribaric S (2016). “The Rationale for Insulin Therapy in Alzheimer’s Disease.” Molecules 21(6.( [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Risner ME, Saunders AM, Altman JF, Ormandy GC, Craft S, Foley IM, Zvartau-Hind ME, Hosford DA and Roses AD (2006). “Efficacy of rosiglitazone in a genetically defined population with mild-to-moderate Alzheimer’s disease.” Pharmacogenomics J 6(4): 246–254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan CM, Freed MI, Rood JA, Cobitz AR, Waterhouse BR and Strachan MW (2006). “Improving metabolic control leads to better working memory in adults with type 2 diabetes.” Diabetes Care 29(2): 345–351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salameh TS, Bullock KM, Hujoel IA, Niehoff ML, Wolden-Hanson T, Kim J, Morley JE, Farr SA and Banks WA (2015). “Central Nervous System Delivery of Intranasal Insulin: Mechanisms of Uptake and Effects on Cognition.” J Alzheimers Dis 47(3): 715–728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schubert M, Gautam D, Surjo D, Ueki K, Baudler S, Schubert D, Kondo T, Alber J, Galldiks N, Kustermann E, Arndt S, Jacobs AH, Krone W, Kahn CR and Bruning JC (2004). “Role for neuronal insulin resistance in neurodegenerative diseases.” Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 101(9): 3100–3105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solano DC, Sironi M, Bonfini C, Solerte SB, Govoni S and Racchi M (2000). “Insulin regulates soluble amyloid precursor protein release via phosphatidyl inositol 3 kinase-dependent pathway.” Faseb j 14(7): 1015–1022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanley M, Macauley SL and Holtzman DM (2016). “Changes in insulin and insulin signaling in Alzheimer’s disease: cause or consequence?” The Journal of Experimental Medicine 213(8): 1375–1385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talbot K, Wang H-Y, Kazi H, Han L-Y, Bakshi KP, Stucky A, Fuino RL, Kawaguchi KR, Samoyedny AJ, Wilson RS, Arvanitakis Z, Schneider JA, Wolf BA, Bennett DA, Trojanowski JQ and Arnold SE (2012). “Demonstrated brain insulin resistance in Alzheimer’s disease patients is associated with IGF-1 resistance, IRS-1 dysregulation, and cognitive decline.” The Journal of Clinical Investigation 122(4): 1316–1338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Heide LP, Ramakers GM and Smidt MP (2006). “Insulin signaling in the central nervous system: learning to survive.” Prog Neurobiol 79(4): 205–221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao WQ, De Felice FG, Fernandez S, Chen H, Lambert MP, Quon MJ, Krafft GA and Klein WL (2008). “Amyloid beta oligomers induce impairment of neuronal insulin receptors.” Faseb j 22(1): 246–260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.