Abstract

Introduction

The purpose of this study was to explore male and female adolescents’ perceptions of and differences in Event History Calendar (EHC) sexual risk assessment in a clinical setting.

Method

This study is a secondary analysis exploring male and female qualitative data from a mixed methods study of adolescent and provider communication. Participants included 30 sexually active 15-19 year old male (N=11) and female (N=19) patients at a school-linked clinic. The adolescents completed a pre-clinic visit EHC and then discussed it with a nurse practitioner (NP) during their visit. The adolescents shared their perceptions of the EHCs in a post-clinic visit interview.

Results

Constant comparative analyses revealed gender differences in: 1) adolescents’ perceptions of how EHCs helped report, reflect on, and discuss sexual risk histories; 2) how adolescents self-administered EHCs; and 3) the histories they reported.

Discussion

The EHC was well received by both males and females resulting in more complete sexual risk history disclosure. Self-administration of the EHC is recommended for all adolescents, but further sexual risk assessment by NPs using EHCs is needed.

Introduction

Recommendations for adolescent health care include sexual risk assessment and preventive health education (American Academy of Pediatrics, 2008; American Medical Association, 1997; National Prevention Council, 2011). However, recent research shows that often when adolescents see primary care providers, few are asked specifically about their risk behaviors, including risky sexual behaviors that can lead to sexually transmitted infections (STIs) and pregnancy (Adams, Husting, Zahnd, & Ozer, 2009). While teen pregnancy rates are the lowest in decades, they are still nine times higher in the United States than in other developed countries (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], 2011b). Additionally, the rates for high risk sexual behaviors and STIs/HIV are on the rise. The 2009 CDC Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance Survey of U.S. high school students showed that 46% engaged in intercourse, 34% had intercourse during the past 3 months, and 14% had intercourse with 4 or more people (CDC, 2010b). Rates of chlamydia and gonorrhea continue to increase among the 15-19 year old population (CDC, 2011a). Healthy People 2020 objectives emphasize the need to increase reproductive health care and reduce sexual risk behaviors, pregnancy, and STIs among adolescents and young adults. (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services [USDHHS], 2012).

Although adolescent males and females are at high risk for consequences of sexual risk behaviors, the majority of research on adolescent sexual behavior and development has focused on females because of pregnancy and early motherhood concerns (Ott, 2010). According to Marcell, Wibbelsman, Seigel and the Committee on Adolescence (2011), “male adolescents’ sexual and reproductive health needs often go unmet in the primary care setting” (p. 1658) because of a variety of barriers including “fear; stigma; shame; denial; lack of social support; lack of confidential services; lack of health insurance options especially as they get older; and not knowing where to go for care” (p. 1664). When males are given sexual risk information, it is usually about condom use and pregnancy prevention (Rosenberger, Bell, McBride, Fortenberry, & Ott, 2010; Sutton, Bron, Wilson, & Klein, 2002).

Healthy People 2020 objectives recognize health care provider assessment and communication as essential to reducing adolescent sexual risk behaviors and improving health outcomes (USDHHS, 2010). Approaches to assist providers in obtaining this sensitive information from adolescents and promoting positive communication are needed in clinical settings. An Event History Calendar (EHC) was developed to improve adolescent report and awareness of their sexual risk histories and facilitate adolescent-provider communication (Marytn, 2009; Martyn, Reifsnider & Murray, 2006). The majority of research on the EHC has been conducted with adolescent females (Martyn, Reifsnider & Murray, 2006). The purpose of this study was to explore male and female adolescents’ perceptions of and gender differences in their use of EHCs in a clinical setting.

Event History Calendar

The self-administered EHC is an innovative research-based approach to assess adolescent sexual risk behaviors and facilitate adolescent-provider communication. The EHC was developed to improve recall, report and discussion of sexual risk behavior patterns over time in the context of the adolescent’s life events, relationships and other risk behaviors (Martyn, 2009; Martyn & Belli, 2002). Martyn and colleagues developed the EHC for clinical use based upon previous life history calendar research with female adolescents (Martyn & Martin, 2003; Martyn, Reifsnider & Murray, 2006). To complete the EHC with adolescents, open-ended questions, autobiographical memory cues, and retrieval cycles are used to obtain a comprehensive view of patterns of behavior, events and interrelationships over time (Martyn, 2009). In previous research, adolescents and providers endorsed the EHC as feasible, valuable for communication in primary health care visits, and as a tool to assess various adolescent life issues (Martyn, Darling-Fisher, Pardee, Ronis, Felicetti & Saftner, 2011; Martyn & Martin, 2003; Martyn et al., 2006; Saftner, Martyn, & Lori, 2011).

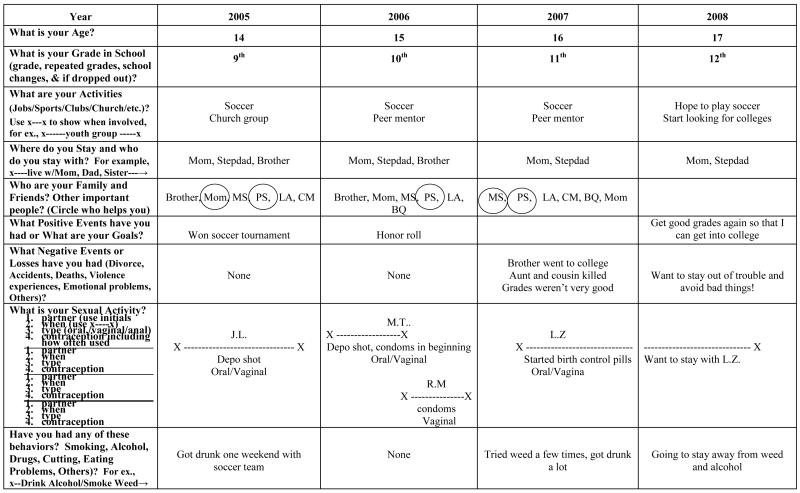

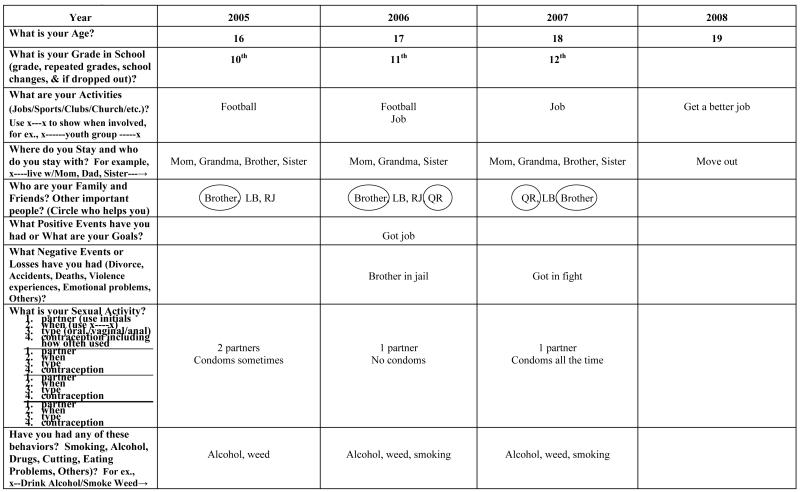

The EHC is a grid with four vertical time columns labeled with four sequential years going across the top of the page. Down the left side of the page are nine horizontal history categories that ask about 1) life context including age, grade level, friends and family members involved in the adolescent’s life, activities, and positive (e.g., awards) and negative (e.g., losses, violence) events, 2) sexual risk behaviors and 3) other risk behaviors (e.g., drugs, alcohol, and cigarettes use; physical fighting). Starting with life context history, such as grade level and activities, the EHC encourages recall and report of more sensitive behaviors and events, such as sexual and other risk behaviors like substance use, fighting, cutting and eating disorders. The first three columns on the EHC are for history information from the current year and the past two years. The fourth column asks the adolescent to record their future goals for each category. The EHC provides the adolescent with an opportunity to record and view their behavior and life events over a three year period and consider the interrelationships between behaviors and events See sample female and male EHCs in Figures 1 & 2 respectively.

Figure 1.

Female EHC Example

Figure 1.

Male EHC Example

Theoretical Framework

The EHC was designed based on Cox’s (1982; 2003) Interaction Model of Client Health Behavior (IMCHB) and theories of cognitive development (Piaget, 1972) and reflection (Baxter Magolda, 1992; Tishman, Perkins & Jay, 1995). The IMCHB is a clinical practice model that contends that client’s health behavior is determined by the fit between their unique characteristics (e.g., adolescent development and needs) and the nurse-client interaction (e.g., adolescent-provider risk behavior communication). According to Piaget (1972), adolescents’ cognitive development moves from concrete to formal operational stage around age 12 years and continues to develop into adulthood. Abstract thinking and problem solving begin to occur during adolescence. Adolescent gender differences in cognition have been noted, including stronger verbal and analytical abilities among females and stronger visuospatial abilities among males (Gesell et al., 1940; Halperin, 2004; Maccoby & Jacklin, 1974). Baxter Magolda’s Epistemological Reflection Model (1992) purports that reflection develops during adolescence and adulthood, and is enhanced through interaction with adults and activities that actively involve them. Furthermore, reflective experiences are thought to enhance adolescents’ ability to think responsibly and strategically (Tishman, Perkins & Jay, 1995).

Until recently, the EHC has focused on adolescent female sexual risk behavior assessment. Exploring the use of the EHC for sexual risk assessment and communication with both adolescent males and females in a clinical setting is an important step in improving clinic-based adolescent sexual risk prevention.

Methods

This study is a secondary analysis of qualitative data (EHCs and interviews) from a sample of Black and White adolescent male and female participants in a mixed methods study on a clinical EHC intervention. The mixed methods study demonstrated that an EHC intervention (described below) resulted in significant improvement in communication and avoidance of unprotected sexual activity at 1 month post-intervention (Martyn et al., 2011). The Institutional Review Board at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan, and Oakwood Hospital and Medical Center, Dearborn, Michigan granted approval for the research protocol, and confidentiality was maintained throughout the research.

Adolescents in this study self-referred from flyers posted in their school-based health care center, or were referred by staff members. A trained research assistant (RA) screened adolescents for eligibility, explained the study and obtained informed consents. Adolescent males and females completed questionnaires, including demographic information (See Table 1) and sexual risk behavior items (e.g., CDC Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance, CDC, 2009) (see Table 2). They were then given a paper EHC, an erasable pen, and instructions to self-administer the EHC before their visit with a Nurse Practitioner (NP) who was trained on the EHC and study procedures. The NP then used the completed EHC to elicit further information about the adolescent’s health care history and current risk behaviors, including additional sexual and other risk behavior history, and made notes on the EHC to clarify or supplement the history. The adolescents spent an average of 10-15 minutes self-administering the EHC and the NP’s estimated that an average of 5 minutes was spent in reviewing the EHC with the adolescents. After the clinic visit with the NP, the adolescents were asked about perceptions of the EHC in an informal, semi-structured interview conducted by the RA. Interviews lasted approximately 15 to 20 minutes. The interviews focused on adolescents’ perceptions of use of the EHC for sexual risk assessment and communication with NPs. See Martyn et al., 2011 for report of quantity and quality of communication with NPs using EHCs in the mixed methods study. All interviews were audiotaped and transcribed verbatim within 48-72 hours. Upon completion of their visit, each adolescent was given a $25 gift certificate for their time.

Table 1.

Demographic Information

| Variables | Females (N=19) | Males (N=11) |

|---|---|---|

| Age | ||

| Mean age (years) | 17.32 | 17.27 |

| Range | 15-19 | 16-19 |

| Race | ||

| White | 13 (68.4%) | 6 (54.5%) |

| Black | 6 (31.6%) | 5 (45.5%) |

| Employment* | ||

| Student | 17 (89.5%) | 9 (81.8%) |

| Part-time work | 4 | 3 |

| Full-time work | 0 | 1 |

| Unemployed | 2 | 1 |

| 15 (78.9%) | 9 (81.8%) | |

| Living situation** | ||

| 4 | 1 | |

| 2 | 0 | |

| Lived with parents | 0 | 1 |

| Lived with other family |

10 (52.6%) | 7 (63.6%) |

| Lived with partner | 9 (47.4%) | 4 (36.4%) |

| Lived with friends | ||

| Subsidized lunch | 7 (36.8%) | 4 (36.4%) |

| Yes | 8 (42.1%) | 4 (36.4%) |

| No | 1 (5.3%) | 2 (18.2%) |

| Health insurance | 3 (15.8%) | 1 (9.0%) |

| Medicaid | ||

| Private | ||

| None | ||

| Unknown |

Denotes categories that females and males marked more than one response

Denotes categories that females marked more than one response

Table 2.

Sexual Behavior

| Variables | Girls (N=19) | Boys (N=11) |

|---|---|---|

| Sexual Intercourse | ||

| Oral sex | 10 (52.6 %) | 8 (72.7%) |

| Vaginal sex | 19 (100%) | 11 (100%) |

| Anal sex | 2 (10.5%) | 0 (0%) |

| Age at First Sexual | ||

| Intercourse (oral, anal, vaginal) |

||

| 12 years old | 0 (0%) | 2 (18.2%) |

| 13 years old | 3 (15.8%) | 2 (18.2%) |

| 14 years old | 6 (31.6%) | 4 (36.4%) |

| 15 years old | 4 (21.1%) | 1 (9.0%) |

| 16 years old | 4 (21.1%) | 2 (18.2%) |

| >17 years old | 2 (10.5%) | 0 (0%) |

| Lifetime partners | ||

| 1-2 partners | 7 (36.8%) | 4 (36.4%) |

| 3-5 partners | 7 (36.8%) | 4 (36.4%) |

| 6-10 partners | 3 (15.8%) | 3 (27.2%) |

| >10 partners | 2 (10.5%) | 0 (0%) |

| Condom use at last | ||

| sex | ||

| Yes | 10 (52.6%) | 7 (63.6%) |

| No | 9 (47.4%) | 3 (36.4%) |

Sample

The sample consisted of 30 adolescents: 11 males (37%) and 19 females (63%). Nineteen of the adolescents were White (N=13, 68.4% of females; N=6, 54.5% males), 11 were Black (N=6, 31.6% of females; N=5, 45.5% males), and the average age for females was 17.32 years and males 17.27 years (range 15-19 years). All were sexually active (reported sexual intercourse in the last 3 months), with males reporting younger age of first sex (<14 years old for 72.8% of males v. 47.4% of females) and slightly higher rate of condom use at last sex (63.6% of males and 52.6% of females); and males and females reporting similar number of lifetime partners (1-5 partners reported by 72.8% of males and 73.6% of females) (see Table 2). Both males and females reported other risk behaviors with similar rates of smoking cigarettes (63.6% and 52.6% respectively), marijuana (54.5 and 52.6%), alcohol use (72.9% and 68.4%) and fighting (18.2% and 21.2%) (see Table 3). The majority of males and females were high school students (n=26) and eligible for subsidized lunch programs (n=17). Most had private health insurance (n=12) or Medicaid (n=11), and the remainder reported no health insurance (n=3) or unknown (n=4). All but one participant lived with at least one family member (n=29) (See Table 1). The majority of adolescent patients come to the school-based health clinic for acute illness, preventative health care (such as annual physical exams), and STI testing and treatment. The adolescents who utilize the clinic for health care live in the immediate residential area or attended the school affiliated with the clinic.

Table 3.

Non-Sexual Risk Behaviors

| Variables | Females (N=19) | Males (N=11) |

|---|---|---|

| Cigarette use | 10 (52.6%) | 7 (63.6%) |

| Alcohol use | 13 (68.4%) | 8 (72.7%) |

| Marijuana use | 10 (52.6%) | 6 (54.5%) |

| Other drug use* | 2 (10.5%) | 0 (0%) |

| Fighting | 4 (21.2%) | 2 (18.2%) |

| Cutting | 3 (15.8%) | 1 (9.1%) |

| Eating disorders | 1 (5.3%) | 0 (0%) |

Included cocaine, crack, and inhalants.

Data Analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to summarize frequencies of adolescent demographics, sexual risk behaviors, other risk behaviors, negative events, and goals (Tables 1-5). Qualitative data analysis was guided by the question, “How do males and females differ in their perceptions about and completion of the EHC?” The constant comparative method of analysis was used to identify various themes within each group as well as to compare the females’ and males’ data (Glaser, 1978, 1992). The females’ and males’ qualitative data (EHCs completed by adolescents and NPs, and adolescent interview transcripts) were reviewed separately. First, each group’s EHC data were analyzed individually and then by group for trends in context (e.g., living situation changes, family support, peer groups, school/activities, positive and negative events) and sexual and other risk behaviors (Cresswell, 2003). Then the interview data were analyzed for perceptions about EHC histories and use of EHCs for reporting and discussing sexual risk histories. Memos were recorded about trends identified, how the adolescents felt about completing their EHC, and their use of the EHC in the clinic visit. Next, trends and themes across male and female groups were compared. All 30 EHCs were reviewed side by side, along with the transcripts. Separately, two of the co-authors made notes of similarities and differences among the themes identified for the males and the females. Then they recorded memos of similarities and differences between the two groups (Creswell, 2003). Memos were then compared and themes extracted from the data. Colleague validation confirmed the themes about male and female adolescents’ perceptions of EHCs, how they completed EHCs, and what history they reported on the EHCs.

Table 5.

Goals

| Variables | Females (N=19) | Males (N=11) |

|---|---|---|

| College (4 or 2 year)* | 11 (57.9%) | 6 (54.5%) |

| Finish high school* | 0 (0%) | 2 (18.2%) |

| GED | 1 (5.3%) | 0 (0%) |

| Join Army | 1 (5.3%) | 0 (0%) |

| Auto body work | 1 (5.3%) | 1 (9.1%) |

| Cosmetology* | 3 (15.8%) | 1 (9.1%) |

| Culinary school | 1 (5.3%) | 1 (9.1%) |

| Start a band | 0 (0%) | 1 (9.1%) |

| No goals | 1 (5.3%) | 1 (9.1%) |

Denotes categories where participants reported 2 goals

Results

Gender differences between male and female adolescents in this study were found in: 1) adolescents’ perceptions of how the EHC helped them report, reflect on, and discuss sexual risk histories; 2) how adolescents self-administered the EHC; and 3) the history they reported on the EHCs. For males the EHC was especially useful for conversations with the NP that resulted in reports of sexual risk histories (e.g., number of sexual partners, type of contraceptives used) and recognition of the need to reduce risk behaviors. For females writing their history on the self-administered EHCs helped them report and discuss their risk histories (e.g., sexual activity and contraceptive use, negative sexual experiences, and relationship violence) and recognize why they engaged in risk behaviors.

Adolescent Perceptions of the Event History Calendars

Male and female participants had different perceptions about how the EHCs helped them to report, think about, and discuss their sexual risk histories with NPs. Most males acknowledged they had never talked to anyone about their sexual history and the EHC made it “easy to talk with the NP” because it “… basically puts it all out there and asked what you wanted to find out.” Females emphasized the process of writing their risk histories on the EHC and how that “showed the patterns [of risk behaviors] … and why [they] might have done them.”

Males’ perceptions of EHCs

The males in this study found EHCs especially helpful because the EHC “… made you have to express yourself” and made it easy to use and talk with the NP about their sexual histories because the EHC “… just had the questions set up, like how and when and where.” One male said that using the EHC with the NP “made me think about all the stuff that had happened” and another said “it put it [sexual behavior] in a wider perspective to how much I lack being safe.” Males indicated that viewing their risk behaviors on the EHC with the NP was important. One said, “I felt more comfortable … cause she [the NP] was seeing what I was seeing. It was basically like the events that went past my life during the last four years basically of high school. So … I felt it was a lot easier for me.” Another male described the process of how reviewing the EHC with the NP made it easier for him to report additional history with the NP:

I read all and then looked back in my head. It was like, oh yeah, that happened and that happened and that happened before. So then when she [the NP] asked me, it’s like, oh yeah, I remember because I just thought about it in my head, and it made it easier because I thought about it and I wrote it down.

Another male said it helped to report their risk histories because they could “just talk with them more, one-on-one.”

Males also found the EHC helped them recognize that they needed to change their risk behaviors. A male stated that the most important thing about the EHC was talking about his eight sexual partners with the NP which he said, “helped me realize to cut down …” Another male said:

I think past sexual experience with partners, realizing, OK I should … I may have took some risks here … maybe I shouldn’t have took risks there, and you know, maybe I should be more careful in the future …

And a male said, “… if you record what you do, you can look back and then change how you do things.” That made sense.”

Females’ perceptions of EHCs

Females thought writing their history on the EHC helped them to think about their history, potential risks and why they engaged in risk behaviors. One female noted that because the EHC was “… written down on paper, you really can focus on it [your risk behaviors].” Another said writing on the EHC was important because, “It all clicked, and it was like, I noticed that I really did put myself in danger. I mean, it’s not like, a lot of kids don’t realize it, but they really do.” Females also described that the EHC made them more aware of their risk behaviors, such as “how many partners you’ve had. It shows that you’ve had many partners.” Females recognized that the EHC helped them report and discuss their sexual histories with the NP. One said, “It was something that I was trying to forget, but it wasn’t a good idea to forget and it’s a good thing that we did talk about it.”

Females also remarked that the EHC helped them reflect on their past sexual history as well as their patterns of behavior. One female described how she used the EHC to reflect on negative influences in her life:

I think it was helpful because you can look back at your history, if you had a history as far as what you were thinking at the moment, it shows influences. So if you have more bad influences, it kind of shows what you were probably doing during that time, whether you were smoking, drinking, or had more sexual partners, or something like that. Cause sometimes when you have a lot on your plate, you turn to negativity. You get involved in peer pressure more… . but I liked the calendar because I got to kind of reflect on certain things and stuff. So when I was filling out stuff when I was younger, I had more things going on, which led me to more negative influences.

How Adolescents Completed the Event History Calendars

Compared to female participants, male participants in this study recorded less history details when they self-administered the EHCs. However, when males reviewed and discussed their EHCs with the NPs, they provided comprehensive detailed sexual risk histories. Both males and females reported additional history during discussion of their EHCs with NPs (e.g., number of sexual partners).

How males completed EHCs

Males reported few history details (e.g., contraceptives used, other risk behaviors, negative events) when they self-administered the EHC, but added details when they reviewed their EHCs with the NP and were asked more questions. One of the male participants noted that the EHCs would be “better to talk with the NP as you fill it [the EHC] out.”

Most male participants completed each category on the self-administered EHC, but wrote less than females on their EHCs, often using short abbreviations. For example, one male used abbreviations to show that he had one sexual partner but no contraceptive information. However, when reviewing/discussing his EHC with the NP, he reported he actually had eight lifetime sexual partners, and reported condom use. Another male recorded “can’t remember” in sections on negative events in his life, but reported negative events when reviewing those sections on the EHC with the NP. With the NP’s assistance, males appreciated how viewing/talking about their EHC with the NP facilitated discussion of their sexual history.

One male noted the most important thing about the EHC was discussing his “… sexual partners and all that” with the NP. Additional data, especially related to the number of sexual partners, was recorded on the EHCs of males during the clinic visits with the NPs. For example, two males who had recorded 2 partners when they self-administered the EHC, disclosed that they each had 8 partners but they reviewed their EHCs with the NP. In addition, some of the males reported that they did not understand the EHC vocabulary (e.g., contraception) and had difficulty understanding the instructions (e.g., using abbreviations or symbols such as x----x to show duration of partner relationships).

How females completed EHCs

Females wrote more information on the self-administered EHC about sexual activity, contraception, other risk behaviors, friends, positive and negative events, and future goals using complete words or sentences (instead of abbreviations). Females provided more details about sexual activity, contraceptive use and the sexual partners they listed on the EHC (e.g., how long they stayed with the partner) and their non-sexual risk behaviors and negative events (e.g., got in a fight with mom). For example, one female wrote on her EHC that she had sexual intercourse (oral and vaginal) and used contraceptives (condoms and birth control pills) with six sexual partners for varying lengths of time. She also wrote that she had two overdoses; a drunk driving accident; regular substance use including marijuana, cocaine, alcohol, and cigarettes; eating disorders, and cutting on her EHC.

Females also provided more details about sexual partners when talking with the NP. Five females disclosed additional sexual partner history when they reviewed their EHCs with the NP reporting 3-17 more sexual partners than initially listed on their EHCs. The adolescents commented that discussing their sexual history EHCs with the NPs encouraged them to fully report their sexual risk behaviors.

What Adolescents Reported on the Event History Calendars

When using the self-administered EHC data and the data elicited during the review and discussion with the NPs, both the males and females reported similar types of sexual and other risk behaviors (See Tables 2 & 3). However, gender differences were found in reports of types of negative events and goals (See Tables 4 & 5). Both males and females reported negative events such as a death in the family, a friend in jail, or being kicked out of school or the house. However, females reported sexual or relationship related negative events, including rape, domestic violence, STIs, pregnancy, but males did not. With respect to activities, more males than females (72% v. 47%) reported participating in sports. This is consistent with statistics for adolescents in this age group (Howard & Gillis, 2007).

Table 4.

Negative Events

| Variables | Females (N=19) | Males (N=11) |

|---|---|---|

| Family death | 8 (42.1%) | 3 (27.3%) |

| Family in jail | 0 (0%) | 1 (9.1%) |

| Friend in jail | 1 (5.3%) | 1 (9.1%) |

| Kicked out of school | 1 (5.3%) | 1 (9.1%) |

| Kicked out of house | 3 (16%) | 2 (18%) |

| Abandoned by family | 0 (0%) | 1 (9.1%) |

| Domestic violence | 2 (10.5%) | 0 (0%) |

| Rape | 1 (5.3%) | 0 (0%) |

| Sexually transmitted infection |

2 (10.5%) | 0 (0%) |

| Pregnancy | 3 (15.8%) | 0 (0%) |

Goals, both academic and nonacademic, were reported by males and females (See Table 5). While about half of them reported academic goals (e.g., college, cosmetology school), there was variation in what they reported. Females were more likely than males to write in goals when they self-administered the EHC. Some wrote specific action-oriented goals on the EHC. For example, a female participant who planned to be a cosmetologist had the plan to go to cosmetology school and another whose goal was to attend college was planning to graduate from high school. And others females identified discussed more specific action-oriented goals when they spoke with the NP. Only one female wrote she was “not sure” what her goals were, but when talking with the NP, said her goals were to go to college and get a job. The females commented that the EHC helped them put their life into context and focus on their goals. For example, one participant said, “I liked the calendar … I haven’t really sat down and rethought back in my past. But it really made me sit down and think about like, who was I with, what was I doing, and what are my goals.”

Most of the males did not write goals on the self-administered EHC. However, they reported specific action-oriented goals when they reviewed and discussed their EHC with the NPs. For example, one male wrote in on his EHC that his goal was to play football for a state university, although he had already graduated from high school, was working at a rent-a-car center, was smoking marijuana on a regular basis and not playing sports. He also said on the EHC that he would quit smoking when he started playing football again, yet had no definitive plans to start football. After discussing his goals with the NP, more specific goals were reported. He told the NP he wanted to go to community college and transfer to a state university, and play football, and that he would quit smoking. However, some males did not identify goals even when asked by the NP. For example, a male who had a significant history of poor academic performance (e.g., poor grades, school changes because of negative behavior), and substance abuse, did not identify any future goals on the EHC or during visit with the NP.

Both males and females thought that the future goals column was one of the most important parts of the EHC and the discussion they had with the NP. A female adolescent commented, “I’m really focused on going to school for nursing, and I believe that was the most important to me, because I really want to achieve those goals.” And a male adolescent said the most important thing about the EHC was “my future goals: my physical activities, my sexual activities, alcohol and drugs.”

Discussion

The EHC was useful for sexual risk behavior assessment for both adolescent males and females in this study. Consistent with prior research with adolescent females (Martyn, 2009; Martyn et al., 2006; Martyn & Martin, 2003) and with reflection concepts (Baxter Magolda, 1992; Tishman et al., 1995), both males and females thought the EHC helped them report, be aware of, and discuss their sexual risk histories with NPs. Males were more likely to report their sexual risk histories (e.g., number of sexual partners, type of contraceptives used) and recognize that they needed to reduce risk behaviors when they viewed and discussed their EHCs with the NP during the clinic visit. Females were more likely to write sexual history details on the self-administered EHC and thought this helped them report and discuss their risk histories (e.g., sexual activity and contraceptive use, negative sexual experiences, and relationship violence); and recognize why they engaged in risk behaviors. Both males and females thought discussing their goals with the NPs was a valuable part of the EHC.

The gender differences in this study are consistent with cognitive and communication theories and research. The ability of the females in this study to self-administer the EHC more completely is consistent with stronger verbal abilities (e.g., language fluency, vocabulary, spelling and writing) (Gesell et al., 1940; Halperin, 2004), and as Halperin noted, “compared to men, women have more rapid access to phonological, semantic, and episodic information in long term memory …” (p. 135). This is relevant to the recall and report involved in self-administration of the EHC in the waiting room prior to a clinic visit. Gender differences in self-disclosure indicate females are more willing to speak about themselves than males (DeVito, 2008) and may explain the type of disclosure involved in EHC self-administration. Cognitive theories and evidence indicate that males have stronger visuospatial abilities. This was consistent with tendencies of males in this study to be more reflective about their risk behaviors once they viewed their EHCs with the NPs (Maccoby & Jacklin, 1974; Halperin, 2004). Opportunities to facilitate adolescents’ reflective abilities should “cultivate cognitive resourcefulness … promote responsible and independent thinking … [and] foster strategic thinking and planfulness” (Tishman, Perkins & Jay et al., 1995, p. 68). Helping adolescents to think in these ways could improve risk behavior reduction efforts.

Recommendations for clinical use of EHCs for sexual risk behavior assessment with adolescents include self-administration and adolescent-provider discussions of the adolescents EHCs with a focus on risk behaviors, life context and future goals. Self-administration of the EHC should be considered as a way to initiate conversations about risk behaviors and increase awareness of risk behavior and need to change. Specifically for male adolescents, considerations for use could include having the provider complete the EHC with them or plan to view their self-administered EHCs with a focus on filling in details about sexual risk behaviors, events, and goals. As noted by male participants the EHCs would be “better to talk with the NP as you fill it [the EHC] out” and “talk to them more, one-on-one.” Recommendations for revisions of the EHC include omitting abbreviations, using a line or an arrow for duration of behaviors/events instead of x----x, and providing definitions (e.g., contraception).

The limitations of this study should be considered when reviewing the results. The sample size was small, participants self-identified as Black or White, were 15-19 years old and from a school-based clinic setting. A larger scale study with a more diverse population in a variety of clinical settings is recommended. In addition, one brief interview was conducted with each adolescent, although they were conducted immediately following the clinic visit for the best opportunity to recall perceptions about EHC use.

Consistently national groups recommend adolescents receive routine sexual risk assessment (AAP, 2003; AMA, 1997). Specifically, the National Prevention Council (NPC) (2011) recommended providers:

Include sexual health risk assessments as a part of routine care, help patients identify ways to reduce risk for unintended pregnancy, HIV and other STIs, and provide recommended testing and treatment for HIV and other STIs to patients and their partners when appropriate (p. 46).

The NPC also recommended individuals “discuss sexual health concerns with their health care provider” (p. 47). However, for this to occur for adolescents and providers working with them, innovative methods of sexual risk assessment and communication, such as the Event History Calendar, are needed.

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge the following grant support by the National Institutes of Health and National Institute of Nursing Research, The Michigan Center for Health Intervention, P30 NR009000.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Kristy K. Martyn, Health Promotion and Risk Reduction Programs at The University of Michigan, School of Nursing, North Ingalls, Ann Arbor, MI, USA..

Melissa A. Saftner, The College of St. Scholastica, School of Nursing, Duluth, MN, USA..

Cynthia S. Darling-Fisher, Health Promotion and Risk Reduction Programs at The University of Michigan, School of Nursing, North Ingalls, Ann Arbor, MI, USA..

Melanie C. Schell, The University of Michigan, School of Nursing, North Ingalls, Ann Arbor, MI, USA..

References

- Adams SH, Husting S, Zahnd E, Ozer EM. Adolescent services: Rates and disparities in preventive health topics covered during routine medical care in a California sample. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2009;44(6):536–545. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2008.08.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Academy of Pediatrics, Committee on Adolescence. Committee on Adolescence Achieving quality health services for adolescents. Pediatrics. 2008;121(6):1263–1270. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-0694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Medical Association . Guidelines for adolescent preventive services (GAPS): Recommendations monograph. Author; Chicago: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Baxter Magolda MB. Knowing and reasoning in students: Gender-related patterns in students’ intellectual development. Jossey-Bass; San Francisco: 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Center for Disease Control and Prevention STDs in adolescents and young adults. 2011a Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/std/stats10/adol.htm.

- Center for Disease Control and Prevention Teen birth rate declined again in 2009. 2011b Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/Features/dsTeenPregnancy/

- Center for Disease Control and Prevention YRBSS: 2009 Questionnaires and item rationale. 2009 2009. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/HealthyYouth/yrbs/questionnaire_rationale.htm.

- Center for Disease Control and Prevention Youth risk behavior surveillance - United States, 2009. MMWR. 2010;59(SS-5):1–142. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Creswell JW. Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches. 2nd ed Sage; Thousand Oaks, CA: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- DeVito JA. Essentials of human communication. 6th Pearson; Boston: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Gesell A, et al. The first five years of life. Harper & Row; New York: 1940. [Google Scholar]

- Glaser BG. Advances in the methodology of grounded theory: Theoretical sensitivity. The Sociology Press; Mill Valley, CA: 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Glaser B. Basics of Grounded Theory Analysis: Emergence vs. Forcing. The Sociology Press; Mill Valley, CA: 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Halperin DF. A cognitive-process taxonomy for sex differences in cognitive abilities. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2004;13(4):135–139. [Google Scholar]

- Howard B, Gillis J. Participation in high school sports increases again. National Federation of State High School Associations (NFSHSA); Indianapolis: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Irwin CE, Adams SH, Park J, Newacheck PW. Preventive Care for Adolescents: Few Get Visits and Fewer Get Services. Pediatrics. 2009;123(4):e565–e572. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-2601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maccoby EE, Jacklin CN. Identification and observational learning from films. Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology. 1974;55:76–87. doi: 10.1037/h0043015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcell AV, Wibbelsman C, Seigel WM, the Committee on Adolescence Male adolescent sexual and reproductive health care. Pediatrics. 128(6):1658–1676. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-2384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martyn KK. Adolescent health research and clinical assessment using self-administered event history calendars. In: Belli R, Stafford F, Alwin D, editors. Calendar and time diary methods in life course research. Sage; Thousand Oaks, CA: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Martyn KK, Belli RF. Retrospective data collection using event history calendars. Nursing Research. 2002;51:270–274. doi: 10.1097/00006199-200207000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martyn KK, Darling-Fisher C, Pardee M, Ronis DL, Felicetti IL, Saftner MA. Improving sexual risk communication with adolescents using an event history calendars. Journal of School Nursing. 2011 doi: 10.1177/1059840511426577. Access: http://jsn.sagepub.com/.doi:10.1177/1059840511426577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marytn KK, Martin R. Adolescent sexual risk assessment. Journal of Midwifery and Women’s Health. 2003;8:213–219. doi: 10.1016/s1526-9523(03)00064-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martyn KK, Reifsnider E, Murray Improving adolescent sexual risk assessment with event history calendars: A feasibility study. Journal of Pediatric Health Care. 2006;20:19–26. doi: 10.1016/j.pedhc.2005.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Prevention Council . National Prevention Strategy. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Office of the Surgeon General; Washington, DC: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Ott MA. Examining the development and sexual behavior of adolescent males. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2010;46:S3–S11. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2010.01.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piaget J. Intellectual evolution from adolescence to adulthood. Human Development. 1972;15:1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberger JG, Bell DL, McBride KR, Fortenberry JD, Ott MA. Condoms and developmental contexts in younger adolescent males. Sexually Transmitted Infections. 2010;86(5):400–403. doi: 10.1136/sti.2009.040766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saftner MA, Martyn KK, Lori JR. Sexually active adolescent women: Assessing family and peer relationships using event history calendars. Journal of School Nursing. 2011;27(3):225–236. doi: 10.1177/1059840510397549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutton MJ, Brown JD, Wilson KM, Lein JD. Shaking the tree of knowledge: Where adolescents learn about sexuality and contraception. In: Brown JD, Steele JR, Walsh-Childer K, editors. Sexual teens, sexual media: Investigating media’s influence on adolescent sexuality. Erlbaum; Mahwah, NJ: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Tishman S, Perkins D, Jay E. The thinking classroom: Learning and teaching in a culture of thinking. Allyn and Bacon; Boston, MA: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Healthy People 2020: Adolescent health objectives. 2012 Retrieved from http://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/topicsobjectives2020/objectiveslist.aspx?topicId=2.